Summary

The cadherin family of cell adhesion molecules mediates adhesive interactions that are required for the formation and maintenance of tissues. Previously, we demonstrated that N-cadherin, which is required for numerous morphogenetic processes, is expressed in the pancreatic epithelium at E9.5, but later becomes restricted to endocrine aggregates in mice. To study the role of N-cadherin during pancreas formation and function we generated a tissue specific knockout of N-cadherin in the early pancreatic epithelium by inter-crossing N-cadherin-floxed mice with Pdx1Cre mice. Analysis of pancreas-specific ablation of N-cadherin demonstrates that N-cadherin is dispensable for pancreatic development, but required for β-cell granule turnover. The number of insulin secretory granules is significantly reduced in N-cadherin-deficient β-cells, and as a consequence insulin secretion is decreased.

Keywords: Pancreas, β-cells, cell adhesion, N-cadherin, Pdx1, islet biogenesis, morphogenesis, differentiation, insulin secretion

Introduction

During mouse development pancreatic progenitors evaginate from the foregut endoderm to establish the dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds at E8.5. These buds later fuse into one organ. The pancreatic epithelium proliferates and develops into a functional ductal network that invades the surrounding mesenchyme. Concomitantly, multipotent progenitors within the pancreatic ductal epithelium differentiate into exocrine and endocrine cell lineages. The acinar lineage produces digestive enzymes that are transported along the duct system to the intestine, whereas the endocrine lineage forms hormone-producing cells. The latter aggregate into islet of Langerhans, a process that is dependent on cellular adhesion (Dahl et al., 1996).

The cadherin family of cell adhesion molecules mediates adhesive interactions that are required for the formation and maintenance of tissues. Cadherins are categorized into several subfamilies according to their molecular structure and function. The most studied members comprise the type 1 classical cadherins, including E-, N-, R-, and P-cadherin.

N-cadherin (Ncad) was first identified as a cell adhesion molecule expressed in neural tissue, but was later found to be expressed in various non-neural tissues, such as the cardiac muscle (Volk and Geiger, 1984), testis (Andersson et al., 1994), kidney (Nouwen et al., 1993), and liver (Nuruki et al., 1998). N-cadherin controls a variety of cellular processes, such as cell sorting, cell migration, and cell reaggregation, during development. N-cadherin-deficient mice die of a malformed outflow tract resulting in cardiac failure at E9.5 (Radice et al., 1997). In endothelial cells N-cadherin regulates proliferation and motility by controlling VE-cadherin expression at the cell membrane (Luo and Radice, 2005). Furthermore, in the cerebral cortex N-cadherin is important for normal architecture of the neuroepithelial or radial glial cells and ablation of N-cadherin randomizes the internal structure of the cortex (Kadowaki et al., 2007).

Previously, we demonstrated that N-cadherin is expressed in the pancreatic epithelium at E9.5, but later becomes restricted to endocrine aggregates in mice (Esni et al., 2001). Furthermore, in the absence of N-cadherin the dorsal pancreatic bud fails to form (Edsbagge et al., 2005). However, this phenotype was rescued by expressing N-cadherin or E-cadherin in the heart (Edsbagge et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2001), demonstrating that the failure to form the dorsal pancreas is secondarily caused by cardiac failure. Thus, the early lethality of N-cadherin-deficient embryos excludes a complete analysis of N-cadherin function in pancreas development.

Here, we show (by more thorough expression analysis) that N-cadherin is expressed uniformly in the pancreatic epithelium until E13.5, but later becomes restricted to endocrine progenitors, mature endocrine cells, neurons, and blood vessels. To study the role of N-cadherin during pancreas formation and function we generated a tissue specific knockout of N-cadherin in the early pancreatic epithelium by inter-crossing N-cadherin-floxed mice with Pdx1Cre mice. Analysis of pancreas-specific ablation of N-cadherin demonstrates that N-cadherin is important for β-cell granule turnover, leading to deficient insulin secretion.

Results

N-cadherin expression during pancreas development

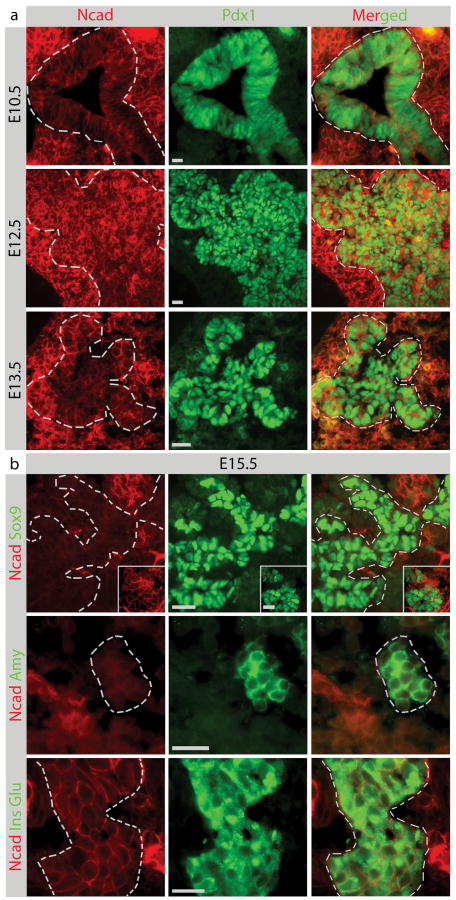

At E10.5-13.5, N-cadherin is expressed throughout the Pdx1+ pancreatic epithelium (Fig.1a). However, at E14.5 N-cadherin is expressed at low levels in Sox9+ cells, acinar cells and mature endocrine cells (Fig.S1). At E15.5, N-cadherin is also detected within a subpopulation of Sox9+ ductal cells, but never in Ngn3+ cells (Fig. 1b,S2). Whereas Isl1+ endocrine progenitors (hormone negative) exhibits a mosaic expression of N-cadherin, all hormone-producing cells express N-cadherin (Fig 1b, S2). N-cadherin is also expressed in endothelial cells and neurons (Fig. S2), but not in acinar cells (Fig. 1b). At E18.5, only endocrine cells, endothelial cells, and neurons express N-cadherin (Fig. S3). At this stage no N-cadherin was detected in ductal and acinar cells (Fig. S3). In the adult pancreas, N-cadherin is expressed in all endocrine cell types, endothelial cells, and neurons (Fig. S4, S5). Similar to at E18.5 no N-cadherin staining was observed in ducts and acinar cells (Fig. S4).

Figure 1. N-cadherin expression in embryonic pancreas.

N-cadherin is coexpressed with Pdx1 in the pancreatic epithelium E10.5-13.5 (a). At E15.5, N-cadherin is expressed in a subset of Sox9+ ductal cells, hormone producing cells (insulin+ and glucagon + cells), but not in amylase+ cells (b). The inset in N-cadherin Sox9 staining is from a different picture. Staining in green (middle) is indicated with a dotted line in red (left). E; embryonic day. Bars 20 μm, inset 10 μm.

Pdx1Cre-mediated conditional ablation of N-cadherin

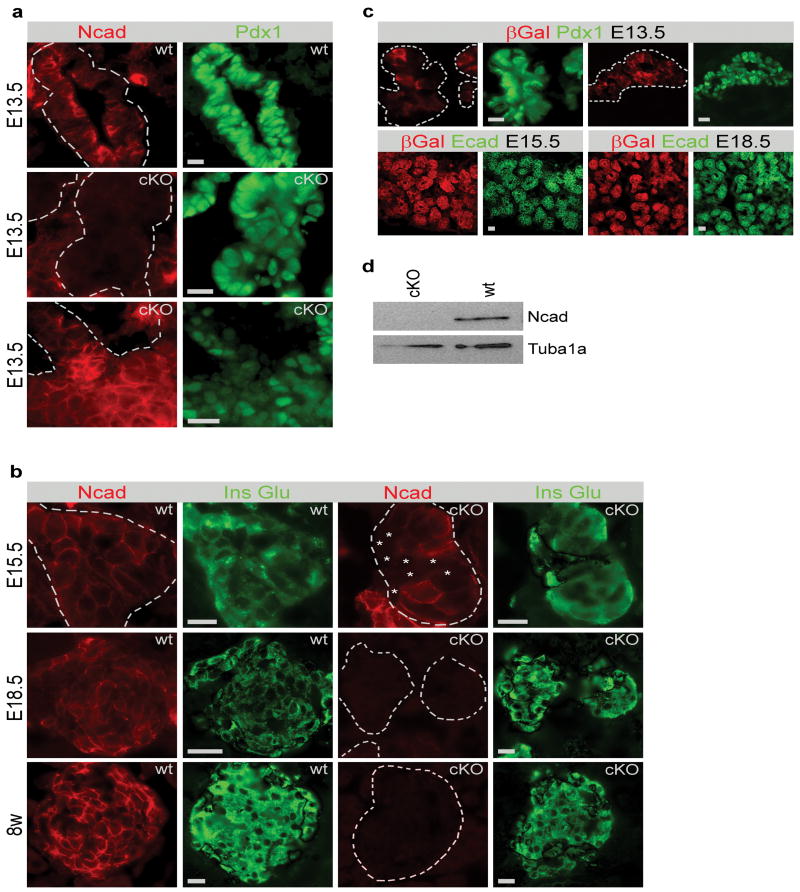

To study the function of N-cadherin during pancreas development N-cadherin was conditionally deleted in Pdx1+ cells (cKO). To ensure that N-cadherin targeting resulted in N-cadherin ablation, N-cadherin expression was examined by immunofluorescence with N-cadherin antibody, and immunoblotting. The efficacy of Pdx1Cre-mediated recombination was tested by intercrossing Pdx1Cre and R26RLacZ mice (Fig. 2c). At E13.5, the efficacy of N-cadherin ablation varied from <5% to almost complete ablation of N-cadherin (Fig. 2a,b,c), indicating variable targeting efficiency of N-cadherin. At E15.5 the expression varied between litter mates, but N-cadherin expression was consistently maintained in more than 50% of Pdx1+ cells. Analysis of sections from Pdx1Cre/R26RLacZ mice by β-Galactosidase (βGal) activity measurements and immunostainings with β-Galactosidase antibody confirmed mosaic recombination at E13.5, but complete recombination at E15.5 (Fig. 2c). The inconsistent recombination of the N-cadherin and R26RLacZ loci suggests a longer half life of the N-cadherin protein or less efficient recombination in the N-cadherin locus compared to the ROSA26 locus. From E18.5 and onwards, N-cadherin was no longer detectable in the pancreas of cKO individuals, indicating efficient (>90 %) recombination at this point (Fig. 2b,c,d). Immunoblotting analysis of adult cKO islets confirmed effective ablation of N-cadherin (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2. N-cadherin expression in the conditional N-cadherin knockout mouse.

N-cadherin is expressed throughout the wt epithelium at E13.5. The recombination efficiency varies from 5% to 95% in cKO embryos (a). At E15.5, approximately 50% of the cells express N-cadherin, while the recombination is complete at E18.5 and in adults (b). Cells with asterisk indicate N-cadherin-ablated cells. R26RLacZ were bred with Pdx1Cre to detect recombination efficiency. Analysis of R26RLacZ/Pdx1Cre mice showed that the recombination efficiency varied at E13.5, while all cells expressed βGal from E15.5 (c). Western blot analysis shows a complete deletion of N-cadherin in adult islets (d). Staining in green (right) is indicated with a dotted line in red (left). Tuba1a; α-Tubulin. Bars 20 μm.

Pancreatic morphogenesis and endocrine specification is unaffected in N-cadherin-deficient mice

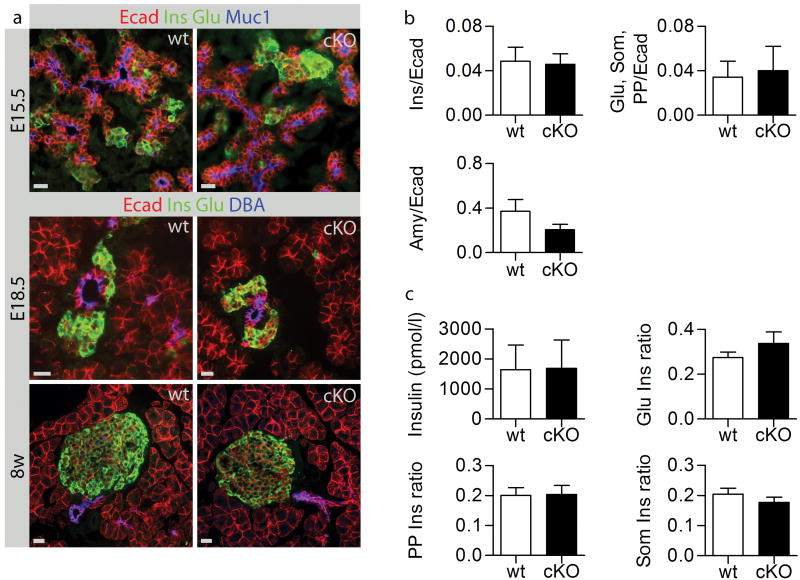

To determine if N-cadherin is required for cell lineage specification, expression of specific markers for acinar (amylase; Amy), ductal (mucin1;Muc1 or DBA), and endocrine cells (insulin;Ins, glucagon;Glu, somatostatin;Som, and PP) were analyzed. At all stages investigated (E13.5, E15.5, E18.5, post natal day four, and adult) development of exocrine and endocrine tissues was unaffected in mutant animals (Fig. 3a,b,c and data not shown). To investigate if N-cadherin is important for initiation and/or maintenance of islet cell polarity, the distribution of characteristic epithelial junctional, apical, and lateral markers, including ZO-1, F-actin, and E-cadherin (Ecad) was analyzed. However, the normal allocation of these cell polarity markers indicates that islet cell contacts and polarity was unaffected (Fig. S6 and data not shown). To understand if microtubule dynamics are altered in the N-cadherin-deficient islets, α- and β-tubulin were analyzed (Fig. S6). However, their expression and subcellular distribution were indistinguishable between wt and cKO islets.To investigate the role of N-cadherin in endocrine cell specification and islet formation we measured the insulin area versus the E-cadherin area at E15.5. However, this analysis revealed no difference between the control and cKO groups, suggesting that N-cadherin is not required for β-cell specification (Fig. 3b). To study if other hormone-producing cells were affected, the ratio of glucagon+, PP+, and somatostatin+ cells versus insulin+ cells, respectively, were estimated in adult mice. As ratios were not altered in cKO islets, N-cadherin appears to be dispensable for endocrine development (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. N-cadherin is dispensable for pancreas morphology.

No morphology changes between wt and cKO were observed (a). Sections throughout E15.5 pancreases were stained with Ins and Ecad, or Glu, Som, PP and Ecad, or Amy and Ecad. The areas of the different markers were measured and compared to the Ecad area. No differences were observed (b). Insulin was measured in adults by ELISA and no differences were observed. We also counted Glu+ cells versus Ins+ cells, PP+ cells versus Ins+ cells, and Som+ cells versus Ins+ cells. The ratios between different hormones were normal (c). Bars 20 μm.

N-cadherin controls insulin granule turnover

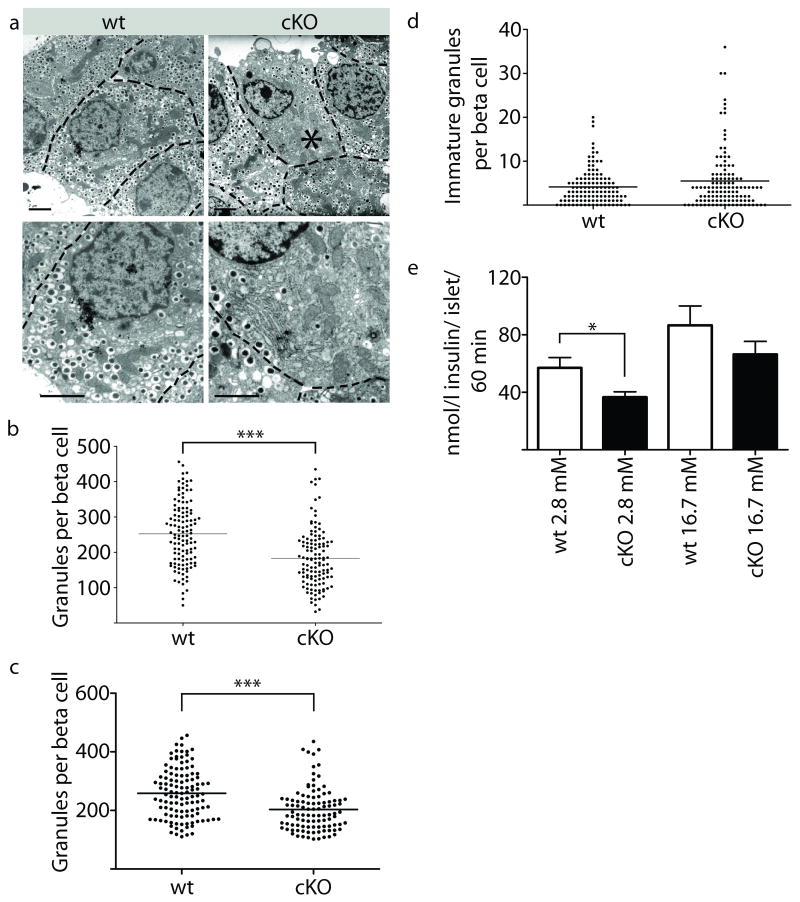

Control and cKO animals were fasted over night to examine whether N-cadherin ablation compromised islet function. Analysis of blood glucose levels revealed no difference between control and cKO animals (Mean ± SEM blood glucose levels wt=4.313 ± 0.1865 mMol/l, cKO=4.000 ± 0.1793 mMol/l. n=8, p-value 0.2471). Nevertheless, transmission electron microscopy studies of adult islets showed a significant overall reduction (27%) of insulin secreting granules in mutant islets (Fig. 4a,b). The average amount of insulin granules per β-cell was 252 and 183 in wt and cKO β-cells, respectively. In addition, 16% of cKO β-cells contained very few insulin granules (less than 100 insulin granules/cell) which is a 67% reduction. This was only observed in 3% of the wt β-cells. Even if the fraction of β-cells with very few insulin granules was not included in the data, the difference between wt (259) and cKO (203) was statistical significant (P<0.0001) (Fig. 4c). In contrast to the observation that N-cadherin-deficiency results in fewer mature granules, there is no significant difference in the number of immature granules (Fig. 4d), suggesting that the decrease in mature granules is not due to a change in biogenesis of granules.

Figure 4. N-cadherin is important for β-cell granule turnover and secretion.

The amounts of mature granules were significantly lower in the cKO compared to wt (P<0.0001) (a,b). In addition, 16% of all mutant β-cells show a dramatic reduction in granule numbers (asterisk) (a). Even if the fraction of β-cells with very few insulin granules was not included in the data, the difference between wt and cKO was statistical significant (P<0.0001) (c). There is no significant difference in the number of immature granules (d). Significant value is indicated as ***p <0.001 and determined by Student's t-test (n=3). Stimulation with low glucose (2.8mM) results in a significant decrease compared to wt (p-value 0.0253). Similar observation was seen at high glucose (16.7mM), however this was not statistical significant (p-value 0.2217) (e). Significant value is indicated as *p <0.05 and determined by Student's t-test (n=7). Error bars represent standard error from the mean (±SEM). Bars 2 μm.

N-cadherin regulates insulin secretion

Insulin secretion was studied in islets from control and cKO mutants in response to low and high concentration of glucose. In response to low glucose levels (2.8mM) insulin secretion was significantly reduced (45%) in cKO (p-value 0.0253). Insulin secretion was also reduced (23%) at high levels of glucose (16.7 mM), however, the change was not significant (p-value 0.2217) (Fig. 4d). Moreover, the effect of Forskolin, Carabachole, and Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) showed no significant difference (data not shown). Thus, the reduced number of insulin granules in cKO results in reduced basal insulin secretion.

Discussion

N-cadherin is required for heart development (Radice et al., 1997), pericyte recruitment (Tillet et al., 2005), endothelial cell proliferation and motility (Luo and Radice, 2005), and for maintaining the normal architecture of neuroepithelial and radial glial cells (Kadowaki et al., 2007). Previously, the collective role of type 1 classical cadherins during pancreatic islet formation was examined by expressing a dominant negative E-cadherin in β-cells. This transgene displaced both E-cadherin and N-cadherin and as a consequence β-cell aggregation and islet formation were disrupted (Dahl et al., 1996). Due to early lethality of N-cadherin deficient-mice the functional role of N-cadherin has only been investigated during the initial stage of pancreas development (Esni et al., 1999).

To study the function of N-cadherin during pancreas development a conditional approach was taken. By ablating N-cadherin specifically during pancreas development we demonstrate that N-cadherin is not essential for pancreas organogenesis. However, the late onset and high variability (5-90 % between E13.5 and E15.5) of recombination, suggest that a potential role of N-cadherin during pancreas development prior to E15.5 cannot be entirely ruled out until more efficient early onset ablation of N-cadherin can be accomplished. Notably, the very same Pdx1Cre line efficiently recombines two independent loci (data not shown), strongly suggesting that the low recombination efficiency is locus dependent. Nevertheless, the participation of N-cadherin-deficient cells in morphogenesis and cell specification suggests that N-cadherin is either not required for these processes or other cadherins, such as E-cadherin and R-cadherin, compensate or exhibit overlapping function with N-cadherin. The latter tentative explanation is based on previous studies demonstrating that during heart development E-cadherin is able to functionally substitute for N-cadherin (Luo et al., 2001). In addition, N-cadherin can substitute for the lack of E-cadherin during ES cell aggregation (Larue et al., 1996). Finally, limb development occurs in N-cadherin-deficient animals due to compensation from another cadherin, most likely cadherin 11 (Luo and Radice, 2005). Regarding the status of other classic cadherins during pancreas development, R-cadherin is normally expressed at low levels intracellularly in beta cells and E-cadherin in pancreatic epithelial cells. Moreover, R-cadherin is dispensable for pancreas development and function (Semb et al., unpublished data). Based on mRNA and immunofluorescene stainings no difference in the level of E-cadherin mRNA and protein and R-cadherin mRNA was observed (data not shown).

Concomitant with islet formation the efficiency of recombination was high (>90 % of endocrine cells). As N-cadherin-deficient endocrine cells aggregate into islets with normal morphology, we conclude that N-cadherin is not required for islet morphogenesis. However, ultrastructural analysis of adult islets revealed a reduction in the number of mature insulin secretory granules in N-cadherin-deficient β-cells. A reduction in the number of mature insulin granules could either be explained by deficient granule biogenesis or perturbed insulin secretion. The fact that the number of immature granules was unaffected suggests that N-cadherin is not required for granule biogenesis. However, consistent with the reduced number of mature granules, N-cadherin-deficient islets displayed deficient basal (low glucose) (and a trend towards lowered glucose-stimulated (high glucose)) insulin secretion. We speculate that the secretion phenotypes may be explained by fewer granules docked to the membrane and/or fewer granules accessible within the readily releasable pool. A similar phenotype is observed in N-CAM-deficient mice where the reduction in α- and β-cell granules is due to abnormal F-actin distribution (Olofsson et al., 2009). In β-cells, the cortical actin network normally functions as a barrier preventing passive diffusion of insulin granules to the plasma membrane (Orci et al., 1972; Wilson et al., 2001). In N-CAM-deficient β-cells, glucose is unable to remodel the actin network and as a consequence secretory granules moves more rapidly to the plasma membrane (Olofsson et al., 2009). Since N-cadherin also binds to F-actin the reduction of insulin secreting granules could be caused by the same mechanisms as in N-CAM knockout mice. However no change in the subcellular distribution of F-actin was identified in N-cadherin-deficient β-cells, suggesting that N-cadherin's role in formation and/or maintenance of secretory granules in β-cells is mediated by a yet to be identified mechanism.

The R6/2 transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease exhibits reduced β-cell mass, insulin content of the islets, and secretion of insulin (Bjorkqvist et al., 2005). The reduction in insulin secretion is due to perturbed microtubule-based transport. Wild type Huntingtin binds microtubules with low affinity and allows vesicular trafficking, whereas a mutant form of Huntingtin binds microtubules with a high affinity and slows down the vesicular trafficking (Smith et al., 2009). N-cadherin regulates microtubule dynamics by stabilizing the microtubule minus-ends that are normally anchored in the centrosome. When centrosomes are removed the minus-ends depolymerises and reduced levels of microtubule polymers are formed (Chausovsky et al., 2000). The fact that α- and β-tubulin expression/distribution was unaffected in N-cadherin-deficient islets suggests that N-cadherin-mediated microtubule dynamics is not a causal factor in insulin granule turnover. In conclusion, our observations strongly suggest that N-cadherin is dispensable for pancreas morphogenesis and cell fate specification, but that N-cadherin is required for insulin secretory granules turnover and insulin secretion. Thus, future studies will have to resolve how N-cadherin is linked to granule turnover.

Methods

Animals

To generate conditional N-cadherin knockout (cKO) mice, we bred mice carrying a conditional N-cadherin floxed (N-cad flox) allele (Kostetskii et al., 2005), Pdx1Cre transgene (Gu et al., 2002), and N-cadherin gene-trapped (N-cad LacZ) allele (Luo et al., 2005). The N-cadherin flox allele has loxP sites flanking exon 1 of the N-cadherin gene, while in the N-cadherin gene-trapped allele, the LacZ reporter gene is inserted into the first intron (between exons 1 and 2) of the N-cadherin gene. No protein is detected in homozygous animals indicating that the N-cad lacZ allele represents a null allele (Luo et al., 2005). Control and cKO were obtained from the same litter. Heterozygous and wild type animals were used as controls, since heterozygous animals were indistinguishable from the wild type. To determine the efficiency of the Pdx1Cre, animals were crossed with R26RLacZ mice (Soriano, 1999). Genotyping was performed by standard PCR-methods. The day of vaginal plug discovery was considered embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). All animal work was approved by a local ethics committee for animal research.

Blood glucose level measurements

For fasting blood glucose level measurements, adult animals were fasted overnight. Blood was obtained from the tail vein and glucose levels were measured using a One touch ultra glucometer (LifeScan, Johnson & Johnson).

Immunofluorescence

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS from four hours to over night at 4°C. Samples for α- and β -Tubulin which were fixed at 37°C for two hours and tissue samples for ZO-1 staining were fixed with 0.2% paraformaldehyde. After washing in PBS, samples were incubated in 30% sucrose in PBS over night at 4°C, embedded in Tissue.Tek® O.C.T.™.(Sakura), and 10 μm or 20 μm thick sections were mounted on poly-L-lysine coated slides, except for N-cadherin Amylase staining in figure S2, which was a paraffin section (Matsuoka et al., 2003). The sections were dried over night, immersed in target retrieval solution (BioGenex), and heated in water bath at 99°C for 11 minutes, for N-cadherin stainings. Sections were blocked with PBS-0.1% Triton X-100 containing 5% non fat dry milk or 5% NDS, 1% BSA for 45 minutes before incubating with primary antibodies over night in blocking solution. A list of primary antibodies is presented in supplementary table one. Slides were incubated with secondary antibodies (Jackson immunoresearch and Molecular probes) diluted in blocking solution for one hour before washing and mounting. Immunostainings were analyzed with a Zeiss axioplan 2 microscope or LSM510 laser scanning microscope.

Isolation of islets

Islets were isolated from female and male cKO and littermate controls. Collagenase P (20U/ml) (Roche) was dissolved in HBSS and injected into the pancreatic duct immediately after killing the animal and opening the abdominal cavity. The caudal portion of the pancreas was then excised and islets were isolated by digestion for 20 min at 37°C. The tissue was dispersed by manual shaking and islets were picked manually.

Immunoblotting

Islets were boiled for five minutes in Sample Buffer (100 mM TRIS, 4% (w/v) SDS, 0.2% (w/v) bromophenol blue, 20% (w/v) glycerol, 200 mM β-mercaptoethanol), centrifuged for five minutes, and samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred from the gel onto nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham). The membrane was blocked for one hour in PBS containing 5% non fat dry milk, followed by incubation with MNCD-2 and α-Tubulin in blocking buffer over night at 4°C. After washing with PBS the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated anti rat and anti mouse secondary antibodies (Sigma) for one hour and proteins were visualized by chemilumininescence (Amersham).

Morphometric analysis

Pancreases from 8 week old animals (n=5) and e15.5 embryos (n=5) were separated with 300 μm and 150 μm, respectively, for morphometric analysis. Totally 20 sections per animals/embryos were used. The endocrine cell ratio was determined by quantifying the number of cells expressing glucagon, somatostatin, PP versus the cells expressing insulin. β cell area, amylase expressing cell area, and glucagon/somatostatin/PP cell area were determined by measuring the percentage of the E-cadherin positive pancreas area that was also insulin positive, amylase positive, or glucagon/somatostatin/PP positive, respectiviely. Sections for transmission electron microscopy were photographed and 40 β-cells per animal (n=3 for each genotype) were used for the analysis. All insulin granules containing a dense core and white hallow was counted. Mean differences were tested for statistical significance by using the Student's t test.

Insulin measurement

Blood samples were collected from vena saphena. Plasma insulin was determined using an ELISA kit (Mercordia) accordingly to the manufacture's instructions.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Islets were prepared as described in ((Kesavan et al., 2009). 50 nm ultra thin sections were cut on a Leica UCT ultra microtome (Leica Microsystems), post-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed in a JEOL JEM 1230 electron microscope.

Insulin secretion in vitro

Islets were isolated and static insulin secretion experiments were performed as described in (Ahren et al., 2007). Assay buffer sample were used for measurement with insulin ELISA (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden). Mean differences were tested for statistical significance by using the Student's t test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kristina Andersson for technical assistance with the Elisa, Rita Wallén for TEM analysis, Lena Eliasson, Jenny Wikman, and Frank Sundler, for analysis of TEM pictures, Marie Magnusson for mouse work, and Isabella Artner, and Jacqueline Ameri for critical comments on the manuscript. The N-cadherin antibody developed by Masatoshi Takeichi and Hiroaki Matsunami was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City, IA 52242. This work was supported by the Stem Cell Center Lund University, Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, Swedish Research Council, and NIH grant: NIH RO1 DK062748.

Literature Cited

- Ahren B, Winzell MS, Wierup N, Sundler F, Burkey B, Hughes TE. DPP-4 inhibition improves glucose tolerance and increases insulin and GLP-1 responses to gastric glucose in association with normalized islet topography in mice with beta-cell-specific overexpression of human islet amyloid polypeptide. Regul Pept. 2007;143:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson AM, Edvardsen K, Skakkebaek NE. Expression and localization of N- and E-cadherin in the human testis and epididymis. Int J Androl. 1994;17:174–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1994.tb01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkqvist M, Fex M, Renstrom E, Wierup N, Petersen A, Gil J, Bacos K, Popovic N, Li JY, Sundler F, Brundin P, Mulder H. The R6/2 transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease develops diabetes due to deficient beta-cell mass and exocytosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:565–574. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chausovsky A, Bershadsky AD, Borisy GG. Cadherin-mediated regulation of microtubule dynamics. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:797–804. doi: 10.1038/35041037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl U, Sjodin A, Semb H. Cadherins regulate aggregation of pancreatic beta-cells in vivo. Development. 1996;122:2895–2902. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edsbagge J, Johansson JK, Esni F, Luo Y, Radice GL, Semb H. Vascular function and sphingosine-1-phosphate regulate development of the dorsal pancreatic mesenchyme. Development. 2005;132:1085–1092. doi: 10.1242/dev.01643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esni F, Johansson BR, Radice GL, Semb H. Dorsal pancreas agenesis in N-cadherin-deficient mice. Dev Biol. 2001;238:202–212. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esni F, Taljedal IB, Perl AK, Cremer H, Christofori G, Semb H. Neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) is required for cell type segregation and normal ultrastructure in pancreatic islets. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:325–337. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu G, Dubauskaite J, Melton DA. Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development. 2002;129:2447–2457. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowaki M, Nakamura S, Machon O, Krauss S, Radice GL, Takeichi M. N-cadherin mediates cortical organization in the mouse brain. Dev Biol. 2007;304:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesavan G, Sand FW, Greiner TU, Johansson JK, Kobberup S, Wu X, Brakebusch C, Semb H. Cdc42-mediated tubulogenesis controls cell specification. Cell. 2009;139:791–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostetskii I, Li J, Xiong Y, Zhou R, Ferrari VA, Patel VV, Molkentin JD, Radice GL. Induced deletion of the N-cadherin gene in the heart leads to dissolution of the intercalated disc structure. Circ Res. 2005;96:346–354. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000156274.72390.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larue L, Antos C, Butz S, Huber O, Delmas V, Dominis M, Kemler R. A role for cadherins in tissue formation. Development. 1996;122:3185–3194. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Ferreira-Cornwell M, Baldwin H, Kostetskii I, Lenox J, Lieberman M, Radice G. Rescuing the N-cadherin knockout by cardiac-specific expression of N- or E-cadherin. Development. 2001;128:459–469. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Kostetskii I, Radice GL. N-cadherin is not essential for limb mesenchymal chondrogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:336–344. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Radice GL. N-cadherin acts upstream of VE-cadherin in controlling vascular morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:29–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka TA, Zhao L, Artner I, Jarrett HW, Friedman D, Means A, Stein R. Members of the large Maf transcription family regulate insulin gene transcription in islet beta cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6049–6062. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.6049-6062.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouwen EJ, Dauwe S, van der Biest I, De Broe ME. Stage- and segment-specific expression of cell-adhesion molecules N-CAM, A-CAM, and L-CAM in the kidney. Kidney Int. 1993;44:147–158. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuruki K, Toyoyama H, Ueno S, Hamanoue M, Tanabe G, Aikou T, Ozawa M. E-cadherin but not N-cadherin expression is correlated with the intracellular distribution of catenins in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncol Rep. 1998;5:1109–1114. doi: 10.3892/or.5.5.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson CS, Hakansson J, Salehi A, Bengtsson M, Galvanovskis J, Partridge C, SorhedeWinzell M, Xian X, Eliasson L, Lundquist I, Semb H, Rorsman P. Impaired insulin exocytosis in neural cell adhesion molecule-/- mice due to defective reorganization of the submembrane F-actin network. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3067–3075. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L, Gabbay KH, Malaisse WJ. Pancreatic beta-cell web: its possible role in insulin secretion. Science. 1972;175:1128–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4026.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radice GL, Rayburn H, Matsunami H, Knudsen KA, Takeichi M, Hynes RO. Developmental defects in mouse embryos lacking N-cadherin. Dev Biol. 1997;181:64–78. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Bacos K, Fedele V, Soulet D, Walz HA, Obermuller S, Lindqvist A, Bjorkqvist M, Klein P, Onnerfjord P, Brundin P, Mulder H, Li JY. Mutant huntingtin interacts with {beta}-tubulin and disrupts vesicular transport and insulin secretion. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3942–3954. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillet E, Vittet D, Feraud O, Moore R, Kemler R, Huber P. N-cadherin deficiency impairs pericyte recruitment, and not endothelial differentiation or sprouting, in embryonic stem cell-derived angiogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2005;310:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR, Ludowyke RI, Biden TJ. A redistribution of actin and myosin IIA accompanies Ca(2+)-dependent insulin secretion. FEBS Lett. 2001;492:101–106. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk T, Geiger B. A 135-kd membrane protein of intercellular adherens junctions. EMBO J. 1984;3:2249–2260. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.