Abstract

The multiple and diverse perspectives, skills, and experiences inherent in community–academic partnerships make them uniquely positioned to educate policy makers and advocate for health equity. Effective communication tools are critical to successfully engage in the policy-making process. Yet few resources emphasize the development and use of practical tools for translating community-based participatory research (CBPR) findings into action. The purpose of this article is to describe a CBPR process for developing and using a one-page summary, or “one-pager,” of research findings and their policy implications. This article draws on the experience of the Healthy Environments Partnership (HEP), a community–academic partnership in Detroit, Michigan. In addition to describing these processes, this article includes a template for a one-pager and an example of a one-pager that was written for and presented to federal policy makers.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, policy, one-pager, communication, practical tool, translation

A key principle of CBPR is its commitment to the translation of research findings into action.1 Although action can take many forms, as Themba and Minkler2, p. 349 have noted, “to influence the lives of large numbers of people, action aimed at changing policy is often critical.” The multiple and diverse perspectives, skills, and experiences inherent in community-academic partnerships make them uniquely positioned to educate policy makers and advocate for health-promoting public policies and health equity.3,4 For example, academic partners can contribute by applying their quantitative and qualitative skills to evaluate proposed legislation or to assess the cost and effectiveness of policies and programs. Community partners, as constituents to a local representative, can influence the policy-making process significantly by, for example, sharing stories about the practical implications of a proposed policy. Together, researchers and community members can develop persuasive advocacy arguments that are based on scientific evidence, local conditions, and the experiences and insights of constituents.

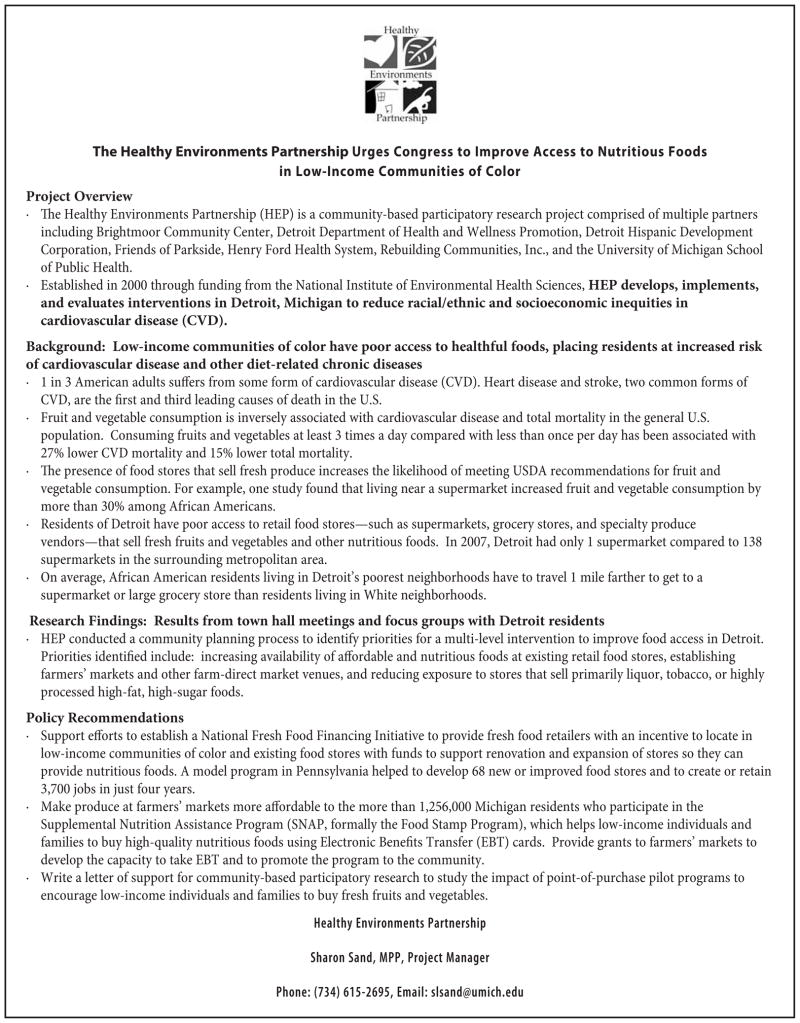

Although existing examples of policymaking within the context of CBPR offer insights into various stages of policy development,2–7 few emphasize the development and use of practical tools to communicate research findings to policy makers. Accordingly, this article has two main aims. First, this article describes a CBPR process for writing a one-page summary, or “one-pager,” of research findings and their policy implications. A one-pager is commonly used as a communication tool in policy advocacy.8–11 In contrast with a policy brief, which is typically longer (two to eight pages), one-pagers include only the most pertinent information and can be an effective way to succinctly summarize major points and guide discussions with policy makers. Second, this article describes a CBPR process for using a one-pager to educate policy makers and advocate for specific requests. To be most useful, this article includes a template for a sample one-pager with key headings and questions to guide community–academic partnerships12,13 in writing a one-pager (Figure 1). One-pagers can be used in multiple settings and the content and format should be tailored to the audience. An example of a one-pager that was written for and presented to federal policy makers also is included (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Components of a One-Pager

Figure 2.

Example One-Pager

This article is based on the development and dissemination of one-pagers on behalf of HEP and the Kellogg Health Scholars Program (KHSP). Established in 2000, HEP is an on-going community–academic partnership that develops, implements, and evaluates multilevel interventions in southwest, eastside, and northwest Detroit, Michigan, to reduce racial/ethnic and socioeconomic inequities in cardiovascular disease.12,13 The partnership is an affiliated project of the Detroit Community–Academic Urban Research Center (Detroit URC) and was initiated to address priorities identified by community and academic partners of the Detroit URC.12 The partnership’s research efforts are guided by a Steering Committee that meets monthly and is composed of representatives (many of whom also are members of the Detroit URC board) from community-based organizations, health service providers, academic institutions, and a community member-at-large (see Acknowledgments for a list of partner organizations). All HEP studies have been granted approval by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board for Protection of Human Subjects.

Upon its inception, HEP adopted a set of CBPR principles that emphasize shared decision making, involving all partners in all phases of research, enhancing the capacity of and co-learning among all partners, conducting research that is beneficial to the community, and disseminating findings in a way that is understandable and useful.1,14 Shortly thereafter, the partnership adapted dissemination guidelines.15 These guidelines emphasize the involvement of all partners in the partnership’s dissemination-related activities and include, for example, criteria for selecting co-presenters and procedures for engaging the Steering Committee in developing abstracts and presentations. The processes for writing and using one-pagers that is described here (and the process for writing this manuscript) were consistent with the dissemination guidelines. For the full text of these guidelines, see: www.HEPDetroit.org

The KHSP is a multisite, 2-year, postdoctoral program with a community track that offers training in CBPR.16 The program provides postdoctoral scholars (herein referred to as “scholars”) with opportunities to translate and disseminate study findings to inform the policy-making process. To support this goal, scholars work with the University of Michigan School of Public Health director of government relations who serves as a consultant to KHSP and who has extensive experience in advocating for public health-related issues at the national, state, and local levels. The consultant conducts training on policy engagement13 for scholars and their academic and community partners and provides advice on how to develop communication tools that are appropriate for policy audiences. The consultant also identifies and arranges meetings for scholars with key federal policy makers, including elected officials and their staff. These meetings take place concurrent with the KHSP Annual Meeting in Washington, DC, which is attended by program administrators, academic and community KHSP mentors, and past, current, and incoming scholars.

A CBPR PROCESS FOR WRITING A ONE-PAGER

The process of writing the one-pagers began when a scholar expressed interest in working with the Steering Committee to develop research-based, simple language, one-pagers based on nearly a decade of research conducted by HEP. The scholar explained that she would be able to take advantage of the policy advocacy support provided by KHSP, with the aim that the one-pagers would be used to educate policy makers about HEP research findings and their policy implications at the federal level.

The Steering Committee—already committed to translating the partnership’s research findings into action—was interested in developing the one-pagers as part of their broader dissemination efforts, which included community newsletters, peer-reviewed publications, and presentations at national conferences and local forums. At one of their monthly meetings, the Steering Committee discussed their policy priorities and the research findings they wanted to communicate to policy makers. As part of their discussion, the Steering Committee considered the following questions3,12,13: What are the relevant policies and practices that are negatively impacting our communities? Which of our research findings are relevant to these policies and practices? What is the political context surrounding these issues? Where do we want to focus our time and resources? What, if any, other groups, or potential collaborators, are already working on these issues? Two policy priorities, based on the partnership’s research on contributors to excess cardiovascular disease in Detroit, were discussed: reducing exposure to harmful air pollutants and improving access to nutritious foods. Steering Committee members shared their concerns about and efforts underway to address the health impacts of relevant issues such as the construction of another international bridge crossing in the predominantly Latino community of southwest Detroit and the continued lack of access to nutritious foods in their communities. As a result of this discussion, the partnership chose to develop 2 one-pagers, each focusing on one policy priority.

Once these two policy priorities were identified as the foci of the one-pagers, a subcommittee made up of interested members of the Steering Committee (including representatives from community-based organizations and academic institutions), the scholar, and members of the KHSP leadership was formed to jointly draft the one-pagers. The subcommittee then discussed and agreed upon a process for developing the one-pagers that was consistent with HEP dissemination guidelines, and identified the roles of each subcommittee member. The scholar then reviewed relevant data already collected and published by HEP and gathered the subcommittee’s perspectives through e-mail and telephone exchanges and in-person conversations. The diverse experiences that subcommittee members brought to the process enriched the content of the one-pagers. For example, subcommittee members who had been involved in Town Hall meetings convened by HEP in which residents expressed concerns about their lack of access to fresh produce, suggested a policy recommendation aimed at making produce at farmers’ markets more affordable to individuals participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.17 Community partners with previous experience working to expand local markets agreed and added that farmers’ markets needed grants to develop the capacity to take Electronic Benefits Transfer cards (the electronic system that replaced paper food stamp coupons with a magnetic striped card) and that grants were needed to promote the program to the community. The final policy recommendation combined these ideas. The scholar took responsibility for drafting the one-pagers using examples written by past scholars. Multiple drafts of the one-pagers were reviewed by the subcommittee and edits were made until there was agreement on their content, format, and perspective among all members of the subcommittee.

Consistent with HEP dissemination guidelines,15 the draft one-pagers were shared with and feedback was elicited from the Steering Committee at one of its monthly meetings. The Steering Committee requested that greater emphasis be placed on policy priorities and suggested modifications to minimize jargon and to ensure that the documents would be accessible to policy makers. They also suggested that the one-pagers be supplemented with supporting documents (e.g., manuscripts, maps). After the meeting, the subcommittee reconvened to discuss the Steering Committee’s recommendations and to revise the one-pagers. At the request of the Steering Committee, drafts of the revised one-pagers were circulated to the Steering Committee via e-mail for additional feedback. Comments made in response to these drafts were discussed among members of the subcommittee before final edits were made. The final versions of the one-pagers, incorporating input from these multiple iterations, were presented to the Steering Committee at its next monthly meeting.

A CBPR PROCESS FOR USING A ONE-PAGER

The process for using the one-pagers was consistent with HEP dissemination guidelines.15 The guidelines request that, to the extent feasible, there will always be at least one community and one academic partner co-presenting information on behalf of HEP. To prepare for visits with federal policy makers, the consultant shared examples of materials that, in addition to the one-pagers, could be included in a “leave behind” packet. The subcommittee prepared a packet that included the following documents, which supplemented the information provided in the one-pagers: relevant newspaper articles, maps, manuscript abstracts, background and contact information for HEP and KHSP, and business cards.

Five individuals from the subcommittee who were already attending the KHSP Annual Meeting met with individual policy makers on behalf of HEP, in three different meetings arranged by the consultant. The meetings served multiple purposes. In addition to communicating research findings and their policy implications, the meetings were an opportunity for the partnership to build and strengthen relationships with policy makers and to position HEP as an expert on issues related to racial/ethnic and socioeconomic health inequities in Detroit. In each meeting, a community partner and the scholar took the lead in presenting one of the two policy priorities as described on the one-pagers. The other subcommittee members provided support and context for the discussions. is strategy allowed the partnership to take advantage of the diverse experiences within the group and added credibility to their policy recommendations. For example, after the scholar presented the one-pager on improving access to nutritious foods in Detroit, one policy maker asked whether residents’ long-standing concerns about racial tensions with neighborhood food store owners were being addressed. A community partner who was aware of this history shared her knowledge of local efforts to improve relationships between residents and store owners.

Using the one-pagers to guide discussions with policy makers helped to ensure that all major points were covered—while still leaving room for questions—in a short (approximately 20 minutes per meeting) amount of time. The one-pagers and leave behind packets were particularly useful in one instance when a meeting was cut short due to the types of interruptions that are commonplace in meetings with federal policy makers. After the meetings concluded, the subcommittee sent letters, on behalf of HEP, to each of the policy makers to thank them for their time. At the HEP Steering Committee’s next monthly meeting, the subcommittee provided the Steering Committee with an update of the meetings with policy makers.

DISCUSSION

The CBPR process for writing and using one-pagers that is described herein provides an example of how community–academic partnerships can build on their diversity to succinctly communicate their research findings to policy makers. In addition to gaining skills in policy advocacy, the subcommittee’s experience built on the partnership’s capacity to work collaboratively by reinforcing trust and respect among the subcommittee members for their individual contributions. The experience also strengthened the partnership’s capacity to engage in policy work as one component of a broader effort to influence change. Consistent with the CBPR principle that calls for co-learning among all partners,1 the CBPR process described herein fostered reciprocal exchange of skills and knowledge among the subcommittee members; the one-pagers could not have been written or presented to policy makers without the expertise contributed by the community and academic partners who were involved in the subcommittee. As a result, the skills and knowledge shared will remain within the partnership.

As part of their ongoing dissemination efforts, the partnership has identified next steps for continuing their policy advocacy work. For example, recognizing the need to inform policy makers at various levels of government, and the limitations of the existing one-pagers for audiences other than federal policy makers, the subcommittee has already started to identify potential policy recommendations that are relevant for state policy makers. In addition, given the space limitations of a one-pager, the partnership has identified dissemination efforts—such as Op-Eds and policy briefs—that will complement the one-pagers and provide space for additional details on the partnership’s research findings and policy recommendations.

SUMMARY

A one-pager is a practical tool that community–academic partnerships can use to communicate their research findings to policy makers as one component of a broader dissemination strategy. This article draws upon the experience of one community–academic partnership, HEP. In this process, HEP benefited from the support of a consultant with expertise in policy advocacy and extensive experience working with federal policy makers. Academic institutions often have an individual on staff who serves as a liaison between the university and different levels of government and who can support community–academic partnerships in the advocacy process. Although such support is not essential to effective policy advocacy, successful engagement with policy makers does rely on relationships and an understanding of the policy-making process. Many partnerships already have knowledge of and facility for policy engagement.4 Those new to the process may wish to build their capacity through consultation with individuals or organizations with expertise in policy advocacy. By using a CBPR process to write and use a one-pager, new and experienced community–academic partnerships can take advantage of their inherent diversity and position themselves to educate policy makers and advocate for health equity.

Acknowledgments

Funded by the National institute of Environmental Health Science (NIEHS) grants R01 ES10936 and R01 ES014234 and the WK Kellogg Foundation.

HEP (www.hepdetroit.org) is affiliated with the Detroit URC (www.sph.umich.edu/urc). The authors thank the HEP Steering Committee for their contributions to the work presented here, including representatives from Brightmoor Community Center, Detroit Department of Health and Wellness Promotion, Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation, Friends of Parkside, Henry Ford Health System, and the University of Michigan School of Public Health and Survey Research Center. We also thank the Kellogg Health Scholars Program for its support, Jenny Poma (Warren Conner Development) and Shannon Zenk (University of Illinois, Chicago) for their contributions to the development of the one-pagers described in this manuscript and the journal editors and four anonymous peer reviewers for their insights and detailed suggestions.

References

- 1.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Themba MK, Minkler M. Influencing policy through community-based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 349–370. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritas C. Speaking truth, creating power: A guide to policy work for community-based participatory research practitioners. [cited 2009 July 16] Available from: http://www.ccph.info.

- 4.Minkler M, Breckwich Vasquez V, Chang C, et al. Promoting healthy public policy through community-based participatory research: Ten case studies. [cited 2009 Aug 27]. Available from: http://www.policylink.org/site/apps/nlnet/content2.aspx?c=lkIXLbMNJrE&b=5136581&ct=6996033.

- 5.van Olphen J, Freudenberg N, Galea S, Palermo A-GS, Ritas C. Advocating policies to promote community reintegration of drug users leaving jail. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 371–389. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee PT, Krause N, Goetchius C. Participatory action research with hotel room cleaners. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 390–404. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breckwich Vasquez V, Lanza D, Hennessey Lavery S, Facent S, Halpin H, et al. Addressing food security through public policy action in a community-based participatory research partnership. Health Promot Practice. 2007;8(4):342–349. doi: 10.1177/1524839906298501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wisconsin PTA. How to write a one-pager. Available from: http://www.wisconsinpta.org/site_uploads/.../advocacyHow2write1pager.doc.

- 9.Robert Graham Center. One-pagers. [cited 2009 Aug 6]. Available from: http://www.graham-center.org/online/graham/home/publications/onepagers.html#y2008.

- 10.Connecticut Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Policy briefing one pager. [cited 2009 Aug 6]. Available from: http://www.ctcadv.org/Portals/0/Uploads/Documents/Policy%20Briefing%20One%20Pager.pdf.

- 11.Food Research Action Center. Outreach activities. [cited 2009 Aug 27]. Available from: http://www.frac.org/pdf/snap_toolkit08_activities_outreach.pdf.

- 12.Flournoy R, Laroi D, Banthia R. Policy Advocacy for CBPR partnerships: Translating research into action. PolicyLink. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin J. Advocacy 101: Translating health disparities community-based participatory research into policy. [cited 2009 Marc 25]. Available from: http://www.kellogghealthscholars.org.

- 14.Becker AB, Israel BA, Allen A. Strategies and techniques for effective group process in CBPR. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healthy Environments Partnership. [cited 2009 Aug 27]. Available from: http://www.sph.umich.edu/hep/

- 16.Kellogg Health Scholars Program. [cited 2009 Aug 19]. Available from: http://www.kellogghealthscholars.org/

- 17.Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Coombe CM, et al. A community-based participatory planning process and multilevel intervention design: Toward eliminating cardiovascular health disparities. Health Promot Pract. doi: 10.1177/1524839909359156. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]