Abstract

This chapter presents an overview of the development, capabilities, and utilization of geographic information systems (GIS). There are nearly an unlimited number of applications that are relevant to GIS because virtually all human interactions, natural and man-made features, resources, and populations have a geographic component. Everything happens somewhere and the location often has a role that affects what occurs. This role is often called spatial dependence or spatial autocorrelation, which exists when a phenomenon is not randomly geographically distributed. GIS has a number of key capabilities that are needed to conduct a spatial analysis to assess this spatial dependence. This chapter presents these capabilities (e.g., georeferencing, adjacency/distance measures, overlays) and provides a case study to illustrate how GIS can be used for both research and planning. Although GIS has developed into a relatively mature application for basic functions, development is needed to more seamlessly integrate spatial statistics and models.

The issue of location, especially the geography of human activities, interactions between humanity and nature, and the distribution and location of natural resources and features, is one of the most basic elements of scientific inquiry. Conceptualizations and physical maps of geographic space have existed since the beginning of time because all human activity takes place in a geographic context. Representing objects in space, basically where things are located, is a critical aspect of the natural, social, and applied sciences. Throughout history there have been many methods of characterizing geographic space, especially maps created by artists, mariners, and others eventually leading to the development of the field of cartography. It is no surprise that the digital age has launched a major effort to utilize geographic data, but not just as maps. A geographic information system (GIS) facilitates the collection, analysis, and reporting of spatial data and related phenomena. The capabilities of GIS are much more than just mapping, although map production is one of the most utilized features. GIS applications are relevant in a tremendous number of areas ranging from basic geographic inventories to simulation models.

This chapter presents a general overview of geographic information system topics. The purpose is to provide the reader with a basic understanding of a GIS, the types of data that are needed, the basic functionality of these systems, the role of spatial analysis, and an example in the form of a case study. The chapter is designed to provide advanced students and experts outside of the field of GIS sufficient information to begin to utilize GIS and spatial analytic concepts, but it is not designed to be the sole basis for becoming a GIS expert. There is a tremendous level of sophistication related to the digital cartographic databases and manipulation of those databases underlying the display and use of GIS that is more appropriately a part of geographic information science (i.e., basic research issues associated with geographic data including technical as well as theoretical aspects such as the impact on society [1]) rather than being relevant to this chapter. The utilization of GIS for conducting spatial analysis is the guiding theme for the chapter.

Keywords: geography, geographic analysis, spatial analysis, clustering, maps

Geographic Information Systems: Background and Basics

A comprehensive history of the development of geographic information systems is not currently available and is recognized as a difficult task because GIS developed along a number of parallel paths [2]; however, some major milestones are clearly recognizable. The development of computer-based geographic information systems (GIS) began in the 1960s with the work of Roger Tomlinson in Canada [3]. Tomlinson’s Canada Geographic Information System (CGIS) was a mainframe-based system that was primarily designed to inventory land use and related natural resources such as soils and timber [4]. The early years of GIS were highlighted by this type of system that required substantial financial resources, depended upon the programming skills of the developers, required the development of digital base maps from scratch, and had relatively limited statistical analytical capabilities. The resources of large corporations or major government agencies were required to support the development of the early GIS, which, because of this fact, were developed for specific rather than general applications.

GIS utilization began to expand during the 1970s, primarily still using mainframe-based approaches. Although begun during the 1960s, the Harvard Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis was one of the main academic groups focusing on developing mapping software for broader distribution during the 1970s [5]. This software, SYMAP, was originally developed for mainframe systems and provided access to thematic mapping, which provided rough map output on line printers. Started in the 1960s, but best known for its release with the 1980 US Census [6], GBF/DIME (Geographic Base File/Dual Independent Map Encoding) files provided the basic geographic information for mapping. These GBF/DIME files were matched to Census geography and provided a node and vector between nodes (i.e. arcs) representation that defined areas (i.e., blocks) with address ranges for each block face. This data representation was a major step forward for GIS use in demographic analysis, as compared to the natural resource orientation of the CGIS.

Commercial GIS applications began to appear in the 1970s; most notable of these applications is the initial release of ARC/INFO by Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) in 1981 [7]. This era highlights the development of GIS as a more general geographic data and analysis tool as compared to a specialized dedicated application. ARC/INFO was designed to operate on minicomputers [8], which were small multiuser computer systems in comparison to main frames, and predated the single-user personal computer. The development of GIS followed the trend toward personal computers in the 1990s with the release of GIS software that operated on Windows NT workstations and eventually on PCs. The release of the US Census TIGER (Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Reference) files, which were updated from the original GBF/DIME system, and the US Geological Survey’s digital line graph as the digital base map [9] highlighted the watershed change associated with a major decrease in cost and increase in access to essential computing and geographic tools.

These developments led to an explosion in the utilization of GIS in a broad array of applications [10, 11, 12]. Business demographics, map routes and directions, health analyses, crime and other demographic and risk factor assessments were now readily accessible because of low-cost personal computing, readily available digital base maps, and links to major descriptive data sources such as the Census and any data that have a geographic reference such as an address. TIGER, with its national set of address ranges, combined with a GIS and a data set with address information could easily facilitate geographic analysis.

More recently in the 2000s [13], distributed GIS applications for relatively simple procedures such as route-finding and mapping specific locations have been implemented, primarily on the internet. Although these applications have brought a simplified form of GIS to a huge audience of users, the more sophisticated spatial and statistical analytical aspects of GIS are still being developed [14], as is the field of geographic information science which studies aspects of further developing GIS capabilities as well as studying the impact of GIS utilization [15, 16]. It is the utilization of GIS as tool for conducting spatial analysis that is the primary focus of this chapter.

Concepts Relevant to GIS

GIS Defined

The definition of GIS has changed over time in response to the broad applications it is now used for and in response to the definition as viewed through the lens of the end user. The development of GIS paralleled other technological developments such as computer information systems, software, and analytical algorithms. This led to a moving target of definitions over time. Here are some examples GIS definitions:

Burrough 1986 [17] “Set of tools for collecting, storing, retrieving at will, transforming and displaying spatial data from the real world for a particular set of purposes. ”

ESRI 1990 [18] “…an organized collection of computer hardware, software, geographic data, and personnel designed to efficiently capture, store, update, manipulate, analyze, and display all forms of geographically referenced information. ”

Clarke 1997 [19] “…automated systems for the capture, storage and retrieval of spatial data.”

Goodchild 1997 [20] “…a system for input, storage, manipulation, and output of geographic information; a class of software; a practical instance of a GIS combines software with hardware, data, a user, etc., to solve a problem, support a decision, help to plan…”

Longley et al. 2005 [15] “Everyone has their own favorite definition of a GIS, and there are many to choose from.” These include GIS as: “a container of maps in digital form…a computerized tool for solving geographical problems…a spatial decision support system…a mechanized inventory of geographically distributed features and facilities…a tool for revealing what is otherwise invisible in geographic information…a tool for performing operations on geographic data that are too tedious or expensive or inaccurate if performed by hand…”

ESRI 2008 [7] “…integrates hardware, software, and data for capturing, managing, analyzing, and displaying all forms of geographically referenced information.”

It is apparent from these definitions that there has been a transition from viewing GIS as a computerized system for a specific application to a more general set of hardware and software tools that are used to facilitate the utilization of geographic information to analyze and model data, and to solve problems. The key concept in the definition of GIS for this chapter is the focus on it as a tool for conducting spatial analysis.

Critical Aspects of Geographic Data

Geography is crucial because almost every activity, feature, or decision has a geographic component. Geographic data have some connection to spatial aspects of the earth, including all of the spheres associated with earth, e.g., biosphere, lithosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere. This definition of geographic data includes the information necessary to create, store and utilize digital representations of the earth as well as the characteristics associated with specific locations and areas. These kinds of data are often called ‘geospatial’. There are a number of critical aspects of geographic data that differentiates this type of information from other types of data. All geographic data is multidimensional. Location requires some form of a spatial reference such as an x, y coordinate, or latitude, longitude component, plus some associated definition or attribute (e.g., location of a crime, elevation of a point, the number of a node in sequence that defines a part of the digital base map). Geographic data, especially the digital base maps, is extremely voluminous. For example, the number of street segments in a single US county of about a million people (Erie County, NY) is about 60,000. The database that is used by the GIS to create and be able to utilize this base map is much larger because multiple pieces of data are required for each street segment (e.g., location of starting and ending nodes, address ranges on each side of the street). The size of the entire street network is in the range of a gigabyte. The number of parcels in Erie County, New York is over 360,000, including all types of property. These examples provide an idea of how much data needs to be manipulated by a GIS to perform mapping and spatial analysis. Attribute data (e.g., locations of events, land use, Census data) are linked to the geographic base map, allowing for spatial analysis to be performed.

Geographic data can be stored and analyzed in a GIS in a number of ways. The two most relevant approaches to storing geographic information are as vector or raster representations. Raster data often are images represented by the number of pixels in a row-and-column format that compose the image. The number of pixels (or cells) can be quite large, especially for a high-resolution image. Each point within a raster data set has an implied location based on its relationship to a single known location on the raster image, which can be determined by the GIS. Vector data representation is based on the exact location of geographic elements, such as points, lines, and areas. Data storage is usually more efficient for vector data because the geographic features can be represented by points (nodes) that are connected by lines (arcs) to form the features, whereas usually all of the raster cells need to be stored. Commercial GIS can typically handle both vector and raster data, including switching between formats when necessary. For example, a GIS can be used to identify point features such as buildings, and lines features such as streets, from a remotely-sensed raster data image and then save this information in vector format.

Geographic data also exists at a number of scales. Scale is the relationship between the actual size of an object and its representation in an abstract form, such as a digital base map. Map scale is often presented as either a scale bar on a hardcopy or computer image, or through the representative fraction, which shows the ratio of the abstract to the real world. For example a representative fraction of 1:50,000 means that one unit on the map is equivalent to 50,000 units in the actual world. Scale defines the level of resolution; small scale (e.g., 1:1000) shows fine-grained, high resolution detail as compared to large scale (e.g., 1:1,000,000), which provides a more generalized representation. Scale is relevant because different processes may occur at different scales. For example, it would not be relevant to conduct an analysis of local neighborhoods or of micro-erosion processes using a digital base map at a scale of 1:1,000,000. Scale and geodetic accuracy are closely related. Some types of applications do not require high-level accuracy. Social and health applications may only need to place the locations of attributes (e.g., crime, disease outbreak) in the correct block or address, whereas the location of features such as water lines and underground electrical lines may need to be mapped with a much higher level of accuracy. Great care is necessary for conducting geographic analyses using data sources at more than one scale, to avoid such issues as the modifiable areal unit problem [21], which is an extension of the ecological fallacy concept.

A spherical, three-dimensional coordinate system is needed to locate places on the earth’s surface; this network of latitude, longitude, and geodesic height is commonly called the Geographic Coordinate System. Mathematical transformations of this spherical, three-dimensional coordinate space, called a map projection, are required in order to accurately produce maps of earth on a plane, such as a hard copy map or a computerized image. Projected coordinates are two dimensional. There are four primary properties that are correct in a spherical representation of the earth that must be considered when projecting onto a flat surface: area, shape, distance, and direction. Map projections can maintain some but not all of these properties and in turn different projections have been developed in order to achieve accuracy in specific properties for the purpose of representation and analysis, e.g. an Albers projection accurately represents areas, but distorts shapes. Most commercial GIS packages will automatically display latitude and longitude-based coordinates as planar x and y coordinates. For small areas, the effect of the projection is small or negligible and may not impact the visual representation of the map within a GIS. However, even at the county-level, there may be distortions in the appearance of polygons in terms of size and shape. Additionally, if precise measurements or analyses are to be conducted, a projected coordinate system that maintains a high level of locational accuracy should be used. The Universal Transverse Mercator coordinate system, for example, is a commonly used grid-based system of projections comprised of a series of sixty zones with minimal local distortion.

The various sources and high level of complexity of geographic data, especially the data required for creating the underlying digital maps utilized in a GIS, create a major need for organizational standards. In the US, the National Geospatial Program [22] coordinates several programs for the creation and implementation of data standards including the Federal Geographic Data Committee, the National Map, and geodata.gov. This topic also highlights the challenges of conducting geographic analysis using GIS in areas of the world that are less developed and lacking in digital map resources. However, the utilization of global positioning system information can be a major assistance in creating data that are amenable to GIS applications.

Spatial Dependence

GIS, like any tool, can be a boon or a bane depending on the relevance of the application. The main underlying principle for geographic/spatial analysis is that geography has some relationship or influence on the circumstances being studied. If there is no relevance, then GIS and spatial analysis is an inappropriate tool for that situation.

However, geographic relevance, while not universal, is quite ubiquitous. The first law of geography, also known as Tobler’s Law, states, “Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things. ” [23]. This “law” is essentially a statement of the concept of spatial dependence, which is also called spatial autocorrelation. Spatial dependence is the statistical recognition that some entity or process is spatially distributed in a non-random manner. If there is no spatial dependence, then spatial analysis is not relevant. The explosive growth in GIS utilization since the early 1990s is a strong endorsement of the fact that much of what exists or occurs on the earth is not randomly distributed.

Spatial statistics [24] are based on exploiting and understanding these spatial dependencies, including networks, spatial regression, spatial clustering, and simple statistics used to identify autocorrelation. The Moran’s coefficient (also called Moran’s I) is similar to the simple correlation coefficient in that it has a range from negative to positive (although Moran’s is not bounded at an absolute value of one) indicating the strength of the spatial autocorrelation [25]. High positive values of Moran’s coefficient indicate positive spatial autocorrelation, indicating that there is a clustering of an attribute. High negative spatial autocorrelation indicates that there is a pattern in the spatial distribution, not a simple clustering. Low absolute values indicate a lack of spatial dependence. GIS facilitates the utilization of spatial statistics and modeling because it automates procedures necessary for the calculation of spatial statistics.

Spatial dependence can also be explored in number of additional approaches. Visualization techniques capitalize on the ability of GIS to display spatial information in a various ways, including animations, three-dimensional representations, and with changes over time [26, 27]. The utilization of GIS and spatial clustering approaches are integral aspects of data mining and knowledge discovery in databases [28, 29]. The development of conditioned choropleth maps, which permits the dynamic visual examination of a dependent variable and two potential predictor variables, highlights the intersection between GIS, statistics, and visualization in an application to generate well-informed, relevant hypotheses [30]. The role of GIS is critical to hypotheses in two ways: as a system that is able to test hypotheses (e.g., where does a specific phenomenon exhibit clustering?) and as a system to generate hypotheses, especially through the insights gained using visualization.

Key Functions of Geographic Information Systems

The focus of this section is on the functionality of GIS that is essential to using GIS for spatial analysis. An understanding of these capabilities provides the background needed to initiate the use of GIS for a specific application.

Geographic Data Elements

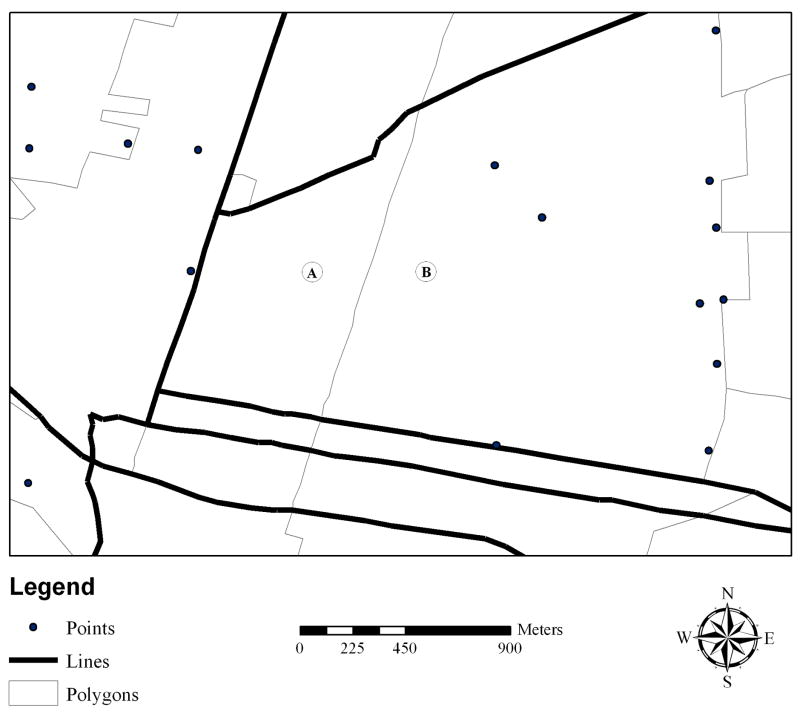

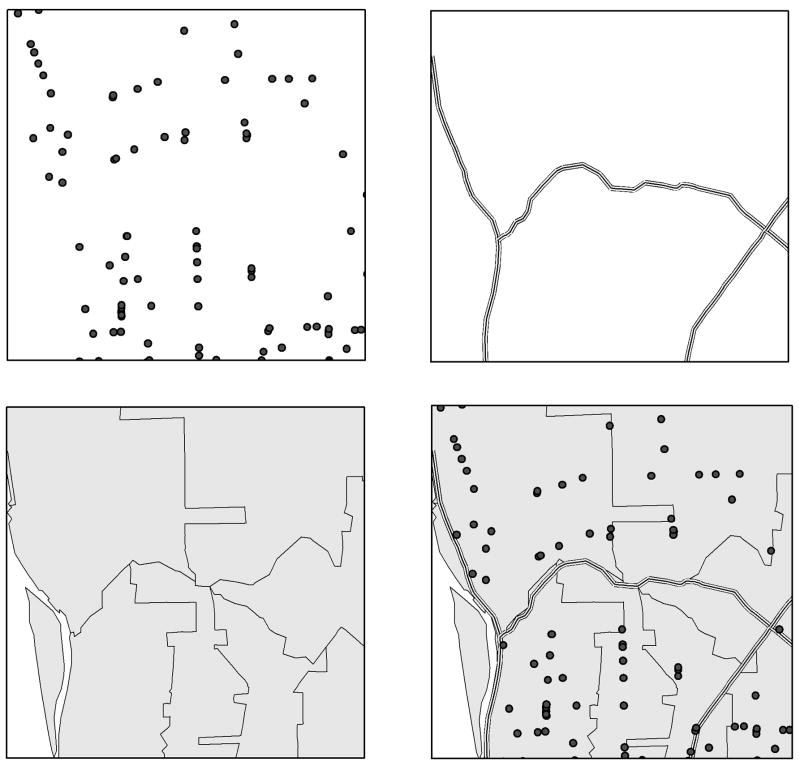

Although GIS can utilize both raster and vector information, raster data is not truly geographic because it is just a simple array of values. Geographic data elements are those entities that one would readily recognize in the real world or on a map. The three elements of spatial objects are points, lines, and polygons (areas). GIS uses coordinates to represent these three geographic objects. Combinations of these three objects are able to represent any geographic entity or the attributes of a geographic entity.

Figure 1 shows examples of the three types of geographic data elements. The points show the location of a specific attribute, which in this example could be buildings. Points are located using x, y coordinates and are considered to have zero dimension. Many objects or events relevant for GIS would be represented as points, such as crime locations, mail boxes, wells, individual trees and so on. However, recognize that scale and resolution often have a role on how an entity will be characterized. For example, a GIS analysis at the scale of North America is likely to display individual cities and towns as points, but they would not be conceptualized in this manner for an analysis of crime within a single city, where the crime locations would be represented as points.

Figure 1.

The lines on figure 1 represent roads. The thickness of the line is based on the type of road. Note that lines and arcs are synonymous in GIS terminology. Lines have a single dimension and are represented by the GIS as points connected by arcs. The lines in figure 1 define areas. The areas are polygons of any shape. Polygons are represented in the GIS by a closed set of lines that define a specific area. These polygons are seen as the areas in figure 1 marked by the letters A and B. Polygons can be ‘piled’ on top of one another to create three-dimensional representations, such as contour lines showing elevation.

A crucial aspect of GIS is that it retains the topological relationships between the geographic data elements. Topology, the mathematics of spatial relationships of connecting adjacent features, is critical for modeling, routing, network analysis, and spatial statistics. The main aspects of topology in GIS is the retention of information that lines have direction (conceptualize a street with addresses, or a stream that flows in a certain direction) and a starting and end point (also known as ‘from’ and ‘to’ nodes). Along these lines, topology includes the information as to which areas/polygons are on the left versus the right side. GIS also retains whether points can fall on a line or within a specific area. A system that does not retain topology is not truly a GIS, but is a collection of various lines and point that are unrelated, which is sometimes called “spaghetti” data. Thus, in figure 1, the GIS recognizes that area A is to the left of the north-running line (road) and that area B is to the right of that line (road).

Georeferencing

Georeferencing, also called geocoding, is the ability to specify the location of geographic data. This section on georeferencing focuses on how to create a georeference for attributes. The creation of the digital base map is a part of computer cartography that provides the tools needed for conducting spatial analysis using GIS, including the development of digital base maps and associated databases used for geocoding.

Georeferencing applies to any method that is able to link some entity to its location in a GIS. This can apply to point, line, or area data. Census tracts, towns, zip-code areas, and counties are examples of areas that can be georeferenced. The process for these types of entities is usually relatively simple because either place names or specific codes can be matched in a database that links the characteristics of these places to locations on a digital base map in a GIS.

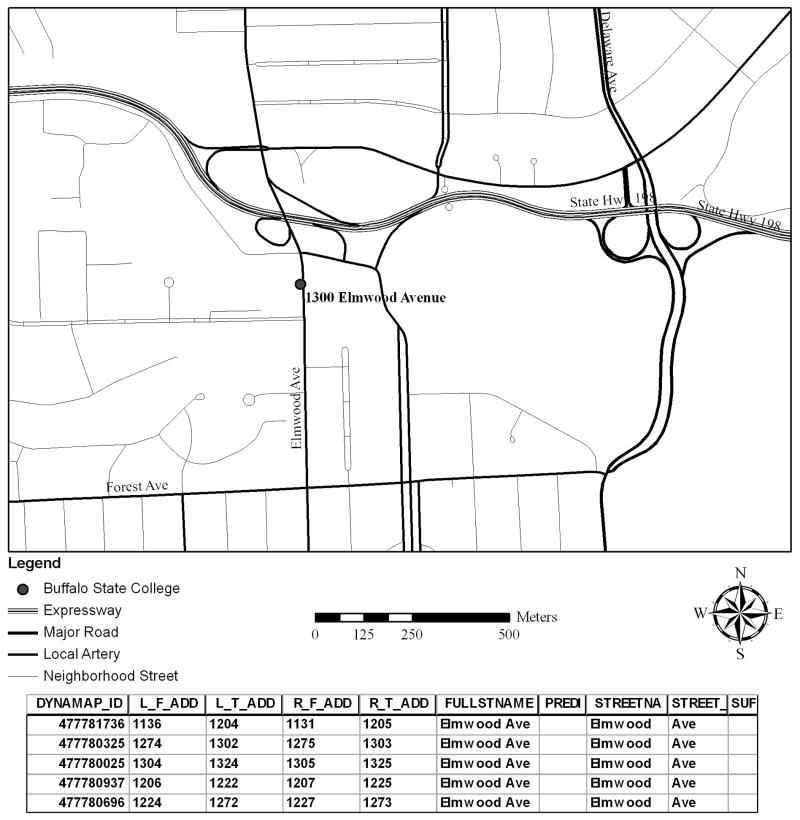

The georeferencing process for full address information is more complex, but is readily accomplished for most areas where the base map includes address and street-level information, such as the TIGER files from the US Census. Figure 2 provides an example for georeferencing the address for Buffalo State College. The college is represented as a point showing the address of 1300 Elmwood Avenue. The georeferenced database in figure 2 shows the topology used to link the address to the digital base map. Notice that there is a left and right side of the street address ranges. In this form of georeferencing, the address of the College is matched to the correct portion of the underlying digital base map (that linkage is managed by the GIS, in this case through the Dynamap_ID link). This process can be accomplished automatically for large databases, making GIS-based spatial analysis readily applicable to any attribute database that has an address. The digital base map addresses could also be in the form of a parcel database that includes each specific address along a block, rather than the range of addresses.

Figure 2.

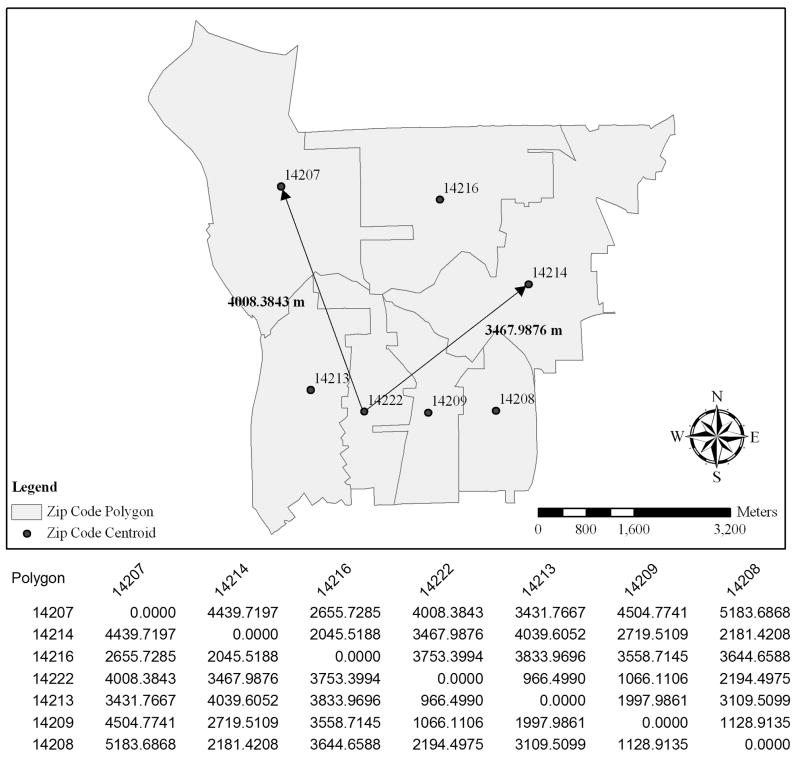

Adjacency and Distance

One main capability of a GIS is to measure distances between objects and to identify whether objects are adjacent to one another. The use of coordinate systems in GIS makes distance measures relatively simple to accomplish, taking into account the sophistication of scale and projection issues. Figure 3 shows the distance measurement capabilities of GIS. This example shows the distances between a number of points. Distance has many obvious uses, but the most relevant and not as obvious one is for spatial analysis and statistics. The bottom section of figure 3 shows a database output of the distances between the points labeled by zip code. This information is a non-map format output of GIS that is a critical input for point pattern analysis and related statistics [31].

Figure 3.

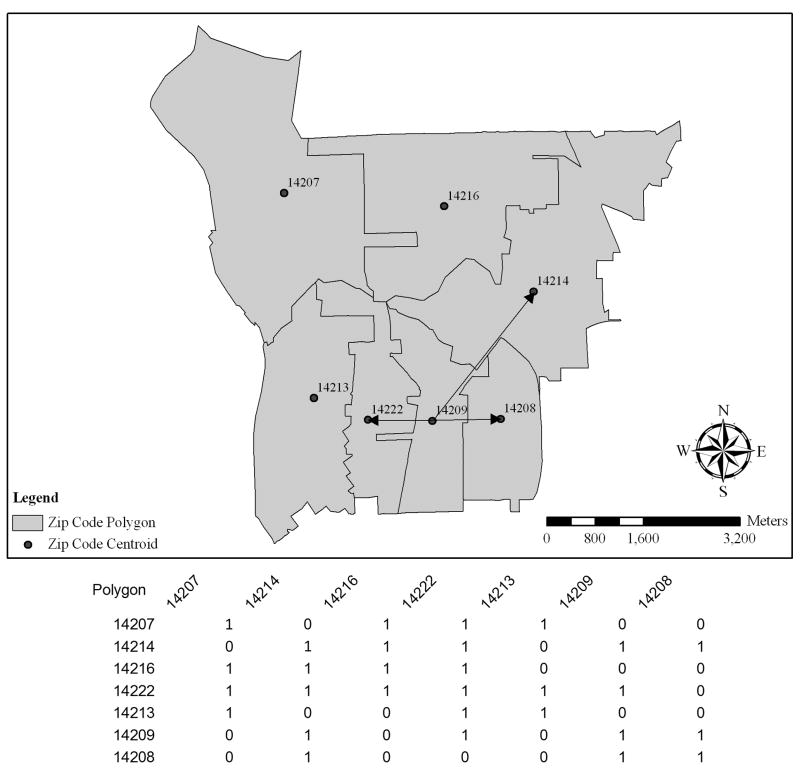

Figure 4 shows the same locations, but is now focused on adjacency, i.e., whether one area/polygon is adjacent to another. Using GIS, adjacency can be measured in number of ways, including a binary yes (1) or no (0), or by the length of the shared boundary. The figure 4 example provides a contiguity matrix of binary adjacency for zip code area 14209. This adjacency matrix would be needed for many types of spatial statistics. Also note that some geographic models assess lagged relationships (i.e., GIS can recognize the first level neighbor/adjacency, second level adjacency, i.e., a neighbor to the neighbor, and so on).

Figure 4.

Overlays and Queries

Essential to the use of GIS is the ability to overlay multiple layers of information and access these various layers simultaneously. Figure 5 shows an example of the overlay function. Points, such as crime locations, lines, such as major roadways, and polygons, such as police districts, are combined into a single digital map by the GIS. GIS can also count the number of crimes in each district in the final overlay. The counting of events or places within a specific geographic area is often needed to facilitate multi-level hierarchical models [32].

Figure 5.

The overlay function facilitates spatial analysis by the ready creation of combinations of information, by creating new forms of information by allocating points to areas for a new area-based metric (e.g., crimes per police district in figure 5), and by allowing the simultaneous querying of the multiple layers used in an overlay. For example, if one wanted to find a location that was within a specific police district, within a specific distance of a main road, and also a specific distance from a the nearest crime, a query could be written to locate the places that meet those requirements.

Spatial Buffers

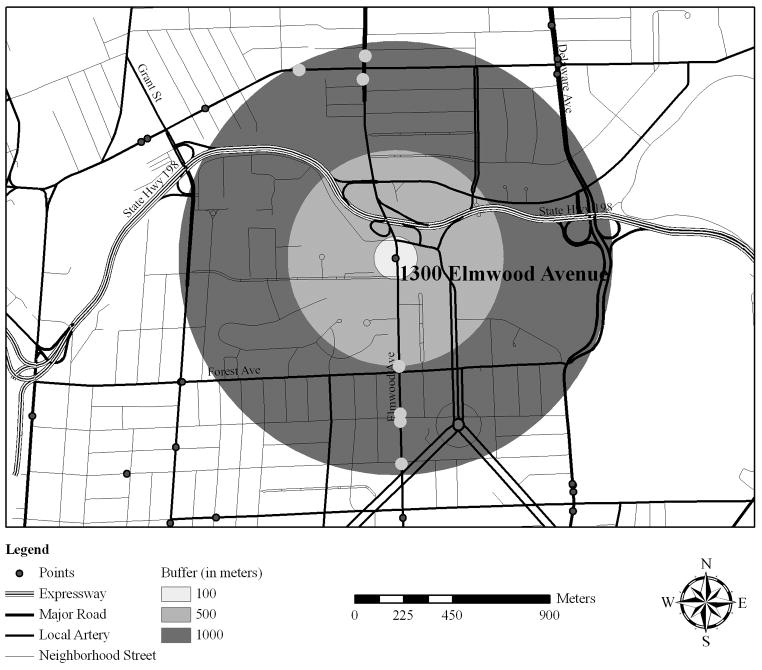

A spatial buffer identifies a specified area around a specific geographic feature. Buffers are useful for identifying neighborhood-related factors for decision-making (e.g., how many of a business’ customers are within a specified distance of a main road). Buffers combine the distance measurement capability of GIS by applying it to various features. Figure 6 shows a radial buffer with the Buffalo State College address as the centroid. GIS buffers would enable counts of students or housing or whatever other layers of data that could be available. The use for policy and planning for this function is obvious, but hard to duplicate without a GIS.

Figure 6.

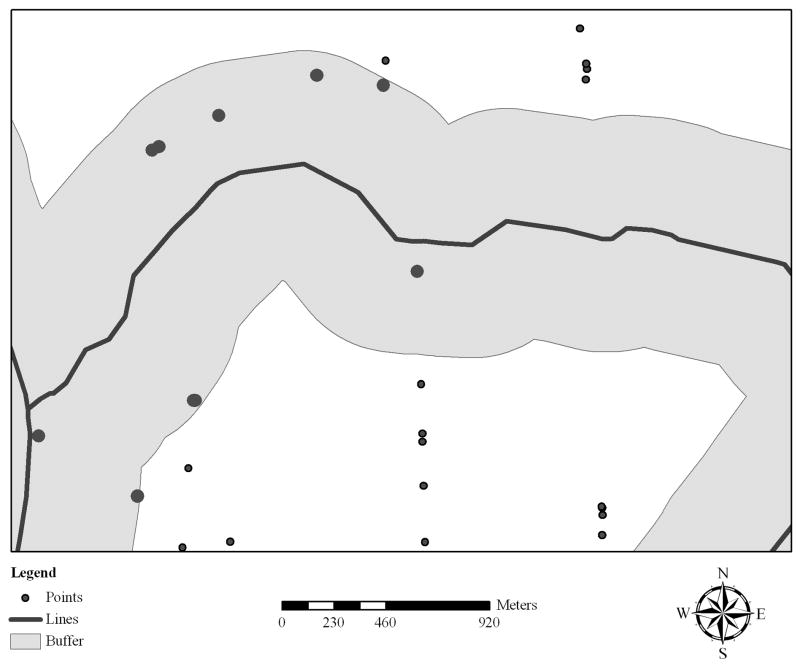

Figure 7 shows a buffer around a line feature, in this case a road that has public transportation. This figure illustrates how a buffer can follow the shape of a more complex feature. The buffer could be used to identify patients or workers that have ready access to public transportation. One can easily imagine how spatial buffers can be combined with multiple overlays and complex queries to facilitate geographic decisions and to create measures that could be used in a variety of statistical or modeling applications.

Figure 7.

Reclassification

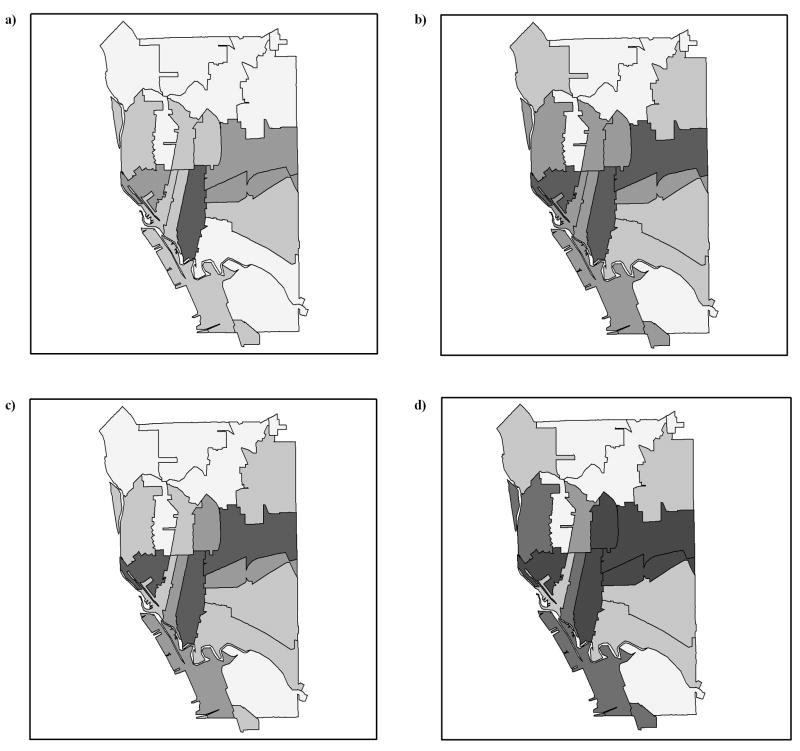

GIS provides the capability of reclassifying data in an automated manner. The reclassification function can be based on a simple re-categorization of the attribute’s distribution, or the reclassification could also be based on adjacency information. The example in figure 8 is based on reclassifying one specific attribute (poverty rate) in four different ways. Map a in the figure shows an equal interval distribution. Equal interval classes are based on creating categories of the attribute that are defined by an equivalent range (e.g., with a range of attribute values of one to twenty, equal intervals are: one-to-five, six-to-ten, eleven-to-15, and sixteen-to-twenty). Note that an equal interval classification does not usually result in an equal proportion of the distribution in each category, as can been seen in figure 8a. Figure 8b shows a classification based on using natural breaks, which utilizes the distributional characteristics of the attribute data to create categories that reflect the majority of the areas as middle ranges and the extremes of the distribution as smaller number of areas. Figures 8c and 8d are based on quantile classifications, which allocate the areas into categories that consist of an equal proportion of the areas in each category. Figure 8c uses a quartile approach; this creates four categories which can readily be interpreted as two categories consisting of the areas below the median and two areas above the median. Figure 8d shows a quintile classification approach. Reclassification can be especially useful as a visualization technique; notice in figure 8 how certain areas are recognizable as having a high poverty rate regardless of the classification scheme.

Figure 8.

Geodatabase

Geodatabase is the term used to describe the database that contains the information relevant to a specific spatial analysis or application [33]. A geodatabase is scalable data architecture that allows the storage of all aspects of the geographic application in a relational database format. This approach allows for greater portability and sharing of specific projects or applications while facilitating complex queries. A geodatabase integrates the GIS application software (e.g., digital base maps, georeferencing etc.) with the data storage of attribute layers, sharing a RDBMS.

GIS Spatial Analysis Case Study: Risk Factors and Drug Use Clusters

The following case study is an extensive collaboration between the Erie County Department of Mental Health, New York State Office of Alcohol and Substance Abuse Services, local alcohol and drug treatment and prevention service providers in Erie County, NY, and the Center for Health and Social Research at Buffalo State College. This collaborative project constitutes a data-driven decision-making approach using small area risk factors, where spatial forms of data are used to assess phenomena across space and to make informed decisions about the most appropriate individual and system-wide responses. These small area risk factors are used to take advantage of available sources of information to improve the planning, provision, and impact of services at the local and county level. This study illustrates many of the main capabilities of GIS; in this case, GIS was used to facilitate a geographic-based needs assessment, a spatial cluster analysis, and to show that the high-risk areas also overlap with the spatial clusters of individual drug users.

Using Social Indicators

It is impossible or impractical to measure specific outcomes in an entire population. However, information is available on factors associated with the phenomenon, such as economic deprivation, crime, and community disorganization in the case of substance use. Rather than trying to measure all of the specific behavioral outcomes that are of interest, such as early drinking and adolescent drug use, social indicators provide a more economical and efficient way to assess the well-being of different populations and sub-populations of interest. The use of indicators is an indirect method of needs assessment for services as it shows the relative need against the other locations in the vicinity and can help to estimate the actual need for service in some situations [34].

While risk factors and social indicators are particularly convenient sources of information for researchers and policy makers since they often can be created based on publically available data, they are also effective in providing organizations (local and regional governments and service providers) with information about local problems on which to focus such as poverty, alcohol availability, and crime in addition to the specific behavioral outcome of interest. This information can be used to tailor services to specific characteristics of the population so as to enhance the effectiveness of interventions. The indicators provided in the examples here are drawn from the Erie County Risk Indicator Database (RIDB) and are based on the risk and protective factor model of substance abuse, delinquency, and other problem behaviors developed by Hawkins and Catalano [34]. Quartiles are used to quantify the level of risk, which is a way of assessing need for services, because these analyses are focused on comparing the risk of small areas relative to one another, as well as for their interpretability (i.e., above median versus below median need) since the results will be used by policy-makers for decision-making purposes.

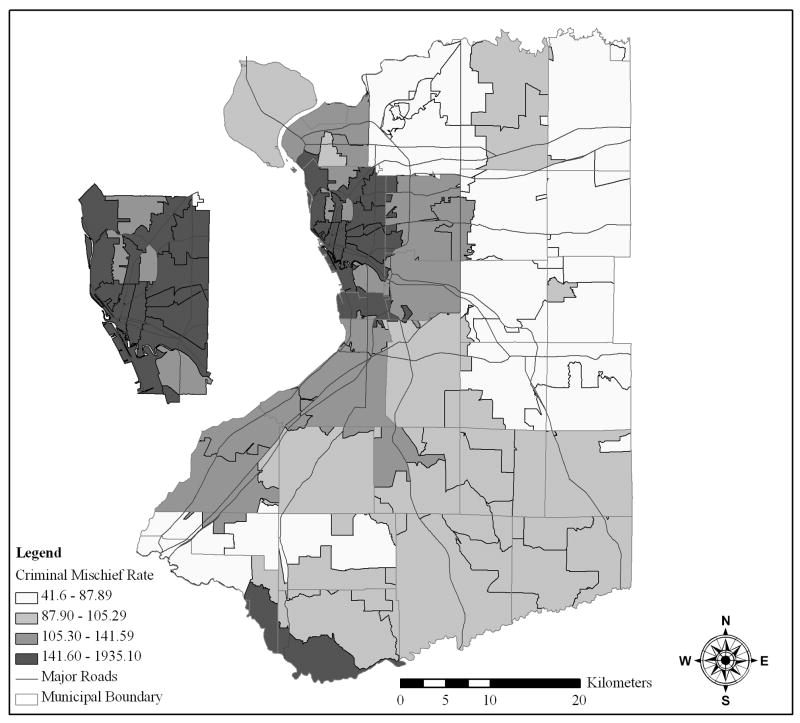

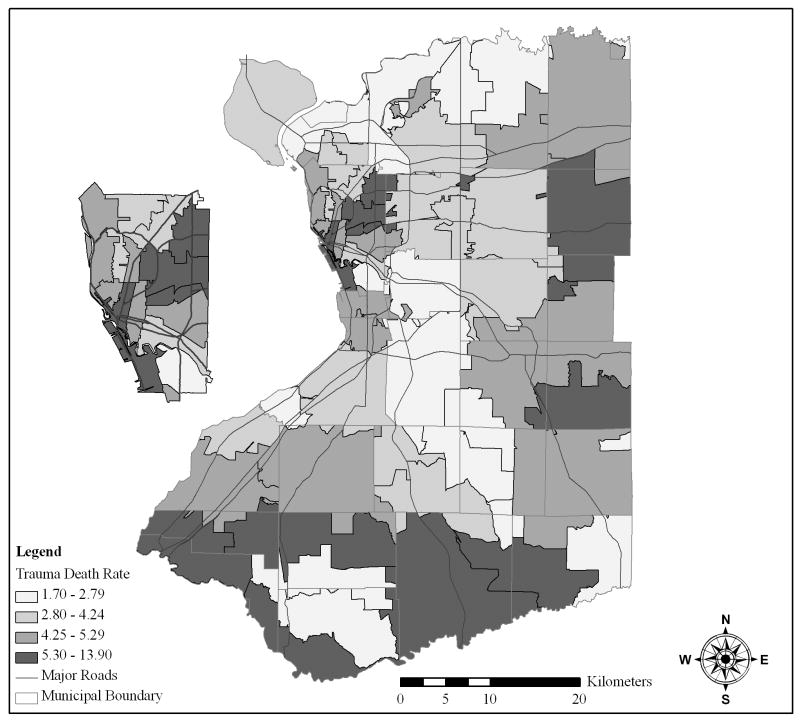

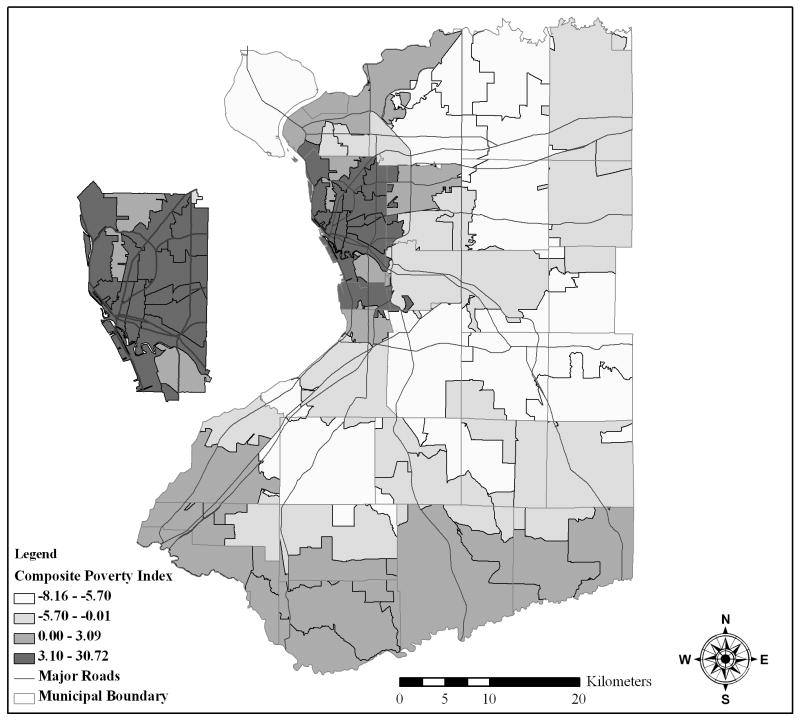

An important component of the development of this database of risk factors was the validation of the indicators. This validation was carried out to address the question: “Do the indicators mean what they’re expected to mean?” The disparate data that comprise these indicators were not collected for this purpose (i.e., needs assessment for drug prevention/treatment-related services) and there are sparse data and publications on this topic. Individual-level, alcohol and drug use and associated health outcome data from the Erie County Health Outcomes (ECHO) survey were used to assess the relationship between these indicators and the outcomes. Many significant associations between the risk indicators and the behaviors of individuals from the same geographic areas were found, supporting the notion that the risk indicators are a valid measure of the need for prevention and treatment services. Examples of the risk indicators are provided by Figures 9, 10 and 11. Figure 9 shows crime rate by zip code area, figure 10 shows the trauma death rate by quartile, and figure 11 shows a composite poverty index by quartile. These maps indicate that the need for alcohol and drug prevention and treatment is not evenly or randomly distributed, as well as that each indicator shows a different aspect of the need for services. Also note that these maps clearly show a number of key aspects such as overlays of major road, municipal boundaries, and the inclusion of a scale bar and a compass rose to help orient the end user. Each map also provides an inset view of the city of Buffalo so that the details of the main urban area can be easily viewed.

Figure 9.

Figure 10.

Figure 11.

Case Study Methods

The individual-level data used in the research are from the Erie County Health Outcomes (ECHO) survey conducted by the Center for Health and Social Research at Buffalo State College, Buffalo, NY beginning in 1996. The general population sample of 3,711 total respondents aged 15-to-45 years old from Erie County was gathered using a random-digit-dial procedure during 1996–2000. The sampling frame consisted of all working telephone blocks in Erie County, New York and reflects the varying population densities throughout the county and is highly representative of the underlying population, which can be seen by comparing key figures such as race (white: 82.1% ECHO, 82.2% 2000 Census) and level of education (Bachelor’s degree or higher: 25.3% ECHO, 24.5% 2000 Census), though there is a slight over-sampling of females in the survey (%female: 56.3% ECHO, 52.2% 2000 Census). These comparisons indicate a minimum of non-response bias in the sample.

Trained interviewers at the Center for Health and Social Research at Buffalo State College conducted the survey. A total of 3,711 interviews were completed based on 5,490 eligible respondents, yielding a response rate of 67.6%. The locations of households of ECHO respondents were geocoded using local street segment data in a GIS. Of the completed interviews, 198 were removed from the dataset because the home addresses given by the respondents was unable to be geocoded. Additionally, for these analyses, lifetime abstainers of alcohol were removed from the dataset in order to better reflect an at-risk population of controls from which our cases were generated. Lifetime abstainers of alcohol are at substantially lower risk for developing illicit drug use problems when compared to individuals who have ever consumed alcohol. A total of 188 respondents who were lifetime alcohol abstainers were removed from the dataset, bringing the sample size to 3,325.

The interview usually lasted between 30- to 90-minutes and gathered extensive data on the individual’s alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use as well as data on household location, neighborhood characteristics, demographics, personality characteristics, alcohol and drug use norms, and peer drug use. Survey respondents were questioned on usage of any illicit drug and in turn on usage of specific types of drugs (cocaine, heroin, marijuana, LSD, etc.). Respondents who had used an illicit drug within the past twelve months were classified as current users of a drug. The marijuana use variable was analyzed directly, whereas all other drug use categories (e.g., cocaine, crack, heroin, etc.) were aggregated to represent users of hard drugs.

Statistically significant spatial clusters can be defined as geographically bounded groups of events where the actual number of events exceeds the expected number when compared to a distribution such as Poisson or Bernoulli. Numerous methods for detecting overall clustering and cluster locations for both point and area data exist, including Anselin’s [35] local indicator of spatial association and Besag and Newell’s [36] method. Kulldorff’s [37] spatial scan statistic method uses a moving window procedure where counts of health events captured in a window are compared to the underlying population while the window systematically covers the area of observation either by centering on an ordered grid, on the case points, or on polygon centroids for area data. This method has been used to examine breast cancer rates at the county level [38], alcohol mortality at the county level [39], and West Nile Virus activity [40]. The moving window expands continuously at each point until it reaches a preset maximum (less than 50% of the population). When the window encounters a new case, elevated risk is tested with the likelihood function on the events within the window compared to those outside, which allows both high and low clusters to be detected. The following equation is the likelihood function I() for the Bernoulli model used in this research:

where n is defined as the total number of cases and controls within a given scanning window, N is the total number of cases and controls in the entire population, c is the number of cases within a given scanning window, and C represents the total number of cases within the entire population. The window size and location that maximizes this likelihood function is the most likely cluster that can reject the null hypothesis of “no clustering”. The detected clusters are then tested against a simulated Monte Carlo distribution of the data set generated under the null hypothesis. This method allows multiple clusters of both high and low use to be simultaneously detected [41]. Secondary clusters have overestimates of their true p-values because they are compared to the most likely clusters from the simulations [42]. This method is especially valuable due to its ease of use (particularly in combination with GIS), applicability to both point and area data, controls for multiple comparisons and population density, and incorporation of covariate and temporal analysis which can aid in its real-world implementation for surveillance of drug-related health problems and service assessments.

Spatial cluster analysis incorporated with the use of GIS mapping capabilities offers a wealth of potential applications in research of illicit drug-related phenomena in both searching for and analyzing identified clusters. The detection of clusters necessitates a more detailed epidemiological examination to determine the validity of its existence, in other words, to evaluate whether the cluster is a “random” occurrence or a manifestation of environmental or social effects. Spatial data of possible correlates or causes can be incorporated with detected clusters in GIS, but issues such as latency in exposure, migration and activity space of individuals within a population, and the differing influences of direct and mediated effects of environmental and social factors obfuscate the understanding of clustering processes and remain stumbling blocks for the development of more sophisticated and powerful theories and methods.

SaTScan v4.0 software developed by Kulldorff [42] was used to calculate the spatial scan statistic. The software requires binary inputs of cases of health events and controls for the Bernoulli model, as well as their associated spatial coordinates; additionally, the Bernoulli model requires multiple data sets, one for each covariate, in order to calculate the spatial scan statistic for case/control covariate analysis. The user can specify the grid of coordinates used by the scanning window, frequently polygon centroids when using area data, as well as the maximum size of the scanning window as a percentage of the study population and the number of simulation iterations for the generated distribution. In this case, the analysis takes an object-oriented approach using the coordinates of the underlying population as centers for the moving circles and uses the default settings of a 50 percent scanning window and 999 iterations. The default scanning window settings is the maximum window size and allows for smaller clusters to be detected as well as the largest possible clusters. A higher number of iterations serves to increase the accuracy of resultant p-values, but also takes more time, whereas fewer simulations yield slightly more uncertain p-values. This method can be computationally challenging in terms of time needed to run the cluster analysis for a personal computer, which was the platform used for these analyses.

Output files from the SaTScan software were then used as inputs in a GIS, linked to the existing ECHO database based on a unique identifier, and mapped with underlying TIGER line files of the Erie County boundary and municipalities as geographic reference. This analysis takes advantage of the overlay capabilities of these programs, allowing the user to layer multiple sources of spatial data on the clustered populations, risk indicators, street network, municipal boundaries, and other pertinent information. Using the spatial output database of clustered and unclustered populations, appropriate statistical analysis such as cross-tabulations, mean comparisons and ANOVA can be utilized to compare clustered and unclustered population groups.

Results and Discussion

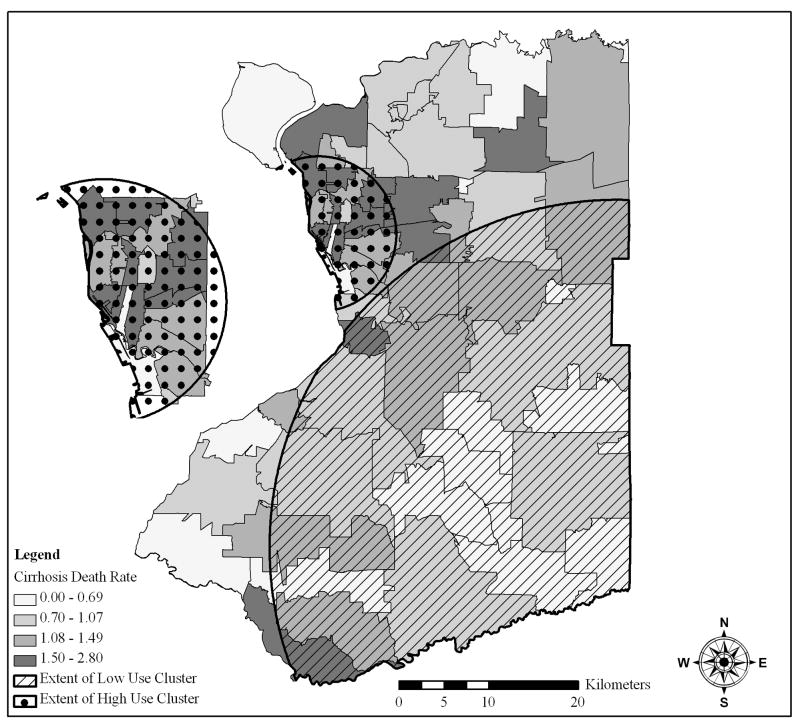

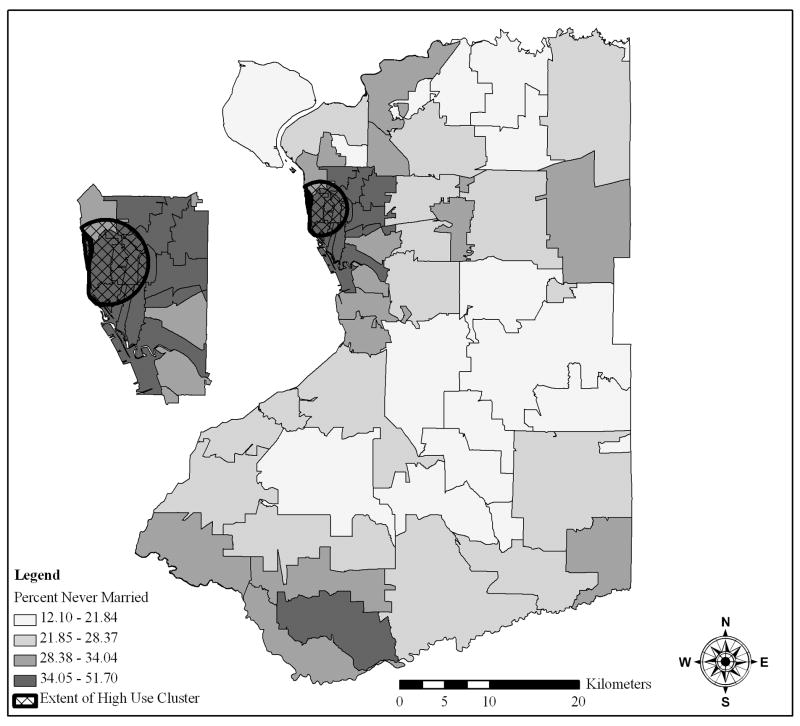

Significant spatial clusters were found for this case study for both marijuana use and for hard drug use. Figures 12 and 13 illustrate the spatial extent of these clusters as well as their spatial relationship to specific risk indicators. The clusters were not the same for the marijuana use (figure 12) and hard drug use group (figure 13), although there was some overlap in high use cluster members. The high use clusters for both drug categorizations are centered in the city of Buffalo, though the hard drug use cluster is smaller and focused in the western and north central part of the city. The marijuana high use cluster extends slightly beyond the city boundary. Additionally, the detected cluster of low use of marijuana extends across the southeastern part of the county, containing an area that is primarily suburban and rural in character; no low hard drug use cluster was detected, suggesting that usage patterns are similar throughout the county outside of the urban high use cluster.

Figure 12.

Figure 13.

The analyses discussed here are primarily focused on examining the relationship between the risk indicators and clusters of substance use by comparing these data sets. These analyses assess: whether there are groups of substance users that are located proximately in space (i.e., clustered); whether the type of drug used makes a difference in where the clusters are found; and how the locations of clusters of different types of drug use relate to the level of risk/need for service in these small areas. Figures 12 and 13 illustrate the visual overlap between high risk areas and drug use clusters. Tables 1 and 2 show the percentage of clustered and unclustered persons who reside in the highest risk quartile of the zip code areas used for the Risk Indicator Database (RIDB). The tables show the proportion of each clustered drug user group that lives within the highest risk quartile for all of the RIDB indicators. Clearly, there is a highly significant difference shown in tables 1 and 2 between the high use drug clusters, the low use drug cluster, and the unclustered persons on whether they reside in a high risk/needs area.

Table 1.

Characteristics for Marijuana Use Clusters: Populations in Areas of High Risk (Zip Codes in Highest Risk Quartile)

| Variable | Unclustered | High Use Cluster | Low Use Cluster | Chi2/F- value | Sig. (*P<0.5, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1316 | 1301 | 708 | ||

| Off Premise Alcohol Outlets | 3.4% | 48.7% | 5.8% | 1364.768 | *** |

| Moved Within County | 4.7% | 70.7% | 7.5% | 1831.294 | *** |

| Population in Rental Units | 5.3% | 71.6% | 0.0% | 2129.910 | *** |

| Composite Poverty Index | 6.6% | 73.2% | 4.4% | 1944.086 | *** |

| Cirrhosis Death Rate | 4.9% | 42.8% | 17.4% | 1000.327 | *** |

| Trauma Death Rate | 1.9% | 28.6% | 2.5% | 1033.625 | *** |

| Never Married | 4.1% | 73.6% | 1.0% | 2208.584 | *** |

| Suicide Rate | 9.0% | 28.2% | 4.1% | 784.529 | *** |

| Low Grade 8 English Performance | 4.3% | 69.3% | 5.4% | 1873.998 | *** |

| Juvenile Violent Crime Arrest Rate | 4.9% | 66.2% | 7.8% | 1845.117 | *** |

| STD Infection Rate (Gonorrhea) | 6.2% | 73.6% | 4.4% | 2288.787 | *** |

| Criminal Mischief Rate | 6.8% | 68.6% | 4.4% | 1975.021 | *** |

| Violent Crime Arrest Rate | 4.6% | 78.9% | 0.0% | 2686.438 | *** |

| Adolescent Pregnancy Rate | 6.6% | 73.2% | 4.4% | 1847.530 | *** |

Table 2.

Characteristics for Hard Drug Use Clusters: Populations in Areas of High Risk (Zip Codes in Highest Risk Quartile)

| Variable | Unclustered | High Use Clusters | Chi2/F- value | Sig. (*P<0.5, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2979 | 346 | ||

| Off Premise Alcohol Outlets | 16.4% | 66.2% | 527.700 | *** |

| Moved Within County | 23.9% | 93.6% | 707.977 | *** |

| Population in Rental Units | 22.0% | 100.0% | 896.601 | *** |

| Composite Poverty Index | 27.3% | 74.6% | 385.681 | *** |

| Cirrhosis Death Rate | 21.2% | 32.4% | 314.966 | *** |

| Trauma Death Rate | 9.9% | 34.7% | 620.058 | *** |

| Never Married | 23.5% | 91.9% | 688.702 | *** |

| Suicide Rate | 7.9% | 80.3% | 1254.261 | *** |

| Low Grade 8 English Performance | 22.8% | 91.9% | 713.454 | *** |

| Juvenile Violent Crime Arrest Rate | 21.7% | 97.1% | 848.950 | *** |

| STD Infection Rate (Gonorrhea) | 24.6% | 97.1% | 746.350 | *** |

| Criminal Mischief Rate | 23.4% | 91.0% | 675.924 | *** |

| Violent Crime Arrest Rate | 25.2% | 97.4% | 735.752 | *** |

| Adolescent Pregnancy Rate | 27.3% | 74.6% | 349.868 | *** |

Comparing these unrelated data sources (i.e., ECHO population sample data, archival risk factors in the RIDB) provides a convincing assessment of the convergent validity between archival indicators of the relative need for services and the actual behaviors of persons who reside in those areas. Tremendously higher proportions of the high use drug clusters live in the highest need areas identified by fourteen different social indicators. Note that the lowest proportion of persons in the high use clusters, although significantly higher than for the unclustered and low use groups, are for indicators likely to be more relevant to alcohol-specific problems such as trauma deaths, suicides, and alcohol availability. While the etiology of this relationship is not elucidated through this process, it nonetheless provides valuable insights, particularly for the targeting and provision of services, as well as for generating relevant hypotheses/research questions (e.g., local area characteristics influences norms regarding drug use). Service agencies and government planners can use this information to develop interventions at the individual and neighborhood levels that aim to address the health-related behaviors, outcomes, and specific risk factors (e.g., crime reduction).

This case study illustrated many of the key capabilities of a GIS when used to conduct a spatial analysis. The case study utilized various archival data sources, multiple base maps for such aspects as boundaries, roads and geocoding, created a distance matrix for use in the clustering software, and multiple overlays were used to show the clusters over risk indicator maps. This example showed how GIS used for spatial analysis is relevant for research (e.g., to show that drug use clusters can be identified) and practical applications for needs assessment and system wide planning for services in Erie County.

Conclusion

Geographic information systems (GIS) have developed from relatively limited access, dedicated applications in the 1970s into the current, broadly based computerized systems designed to facilitate spatial analysis. GIS capabilities have grown, while costs have decreased, because of the revolution toward personal computing and the development of crucial supporting software and digital base map resources, such as TIGER. Accompanying these GIS-specific developments has been the development of spatial statistics, which are key to enhancing the modeling and research capabilities of GIS. The ability to utilize GIS for georeferencing, mapping, reclassification, distance and adjacency measures, and other related tasks has made spatial analysis feasible for simple users as well as for complex applications in spatial and network-based modeling.

Despite these major advances, the spatial statistical capability of typical GIS software is relatively limited. For example, the case study showed that the GIS provided the database on distance associations needed for the cluster analysis, but other software was necessary to conduct the actual clustering. The integration of expanded spatial analytical/statistical capabilities, including various visualization and data discovery techniques, is the next major frontier for GIS. The interface between the GIS user and between GIS and the modeling software has improved greatly since its inception; however, there is substantial progress to be made in these areas. Nonetheless, GIS has proven over the past few decades to be an indispensible tool for almost an unlimited number of practical and research applications.

Further Reading

Griffith, D.A. and Paelinck, J.H.P. An equation by any other name is still the same: On spatial econometrics and spatial statistics. Ann Reg Sci. 2007; 41:209–227.

Hill, L.L. Georeferencing. The Geographic Associations of Information. 2006. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Maguire, D.J., Batty, M., and Goodchild, M.F. (eds.) GIS, Spatial Analysis, and Modeling. 2005. ESRI Press, Redlands.

Obermeyer, N.J., and Pinto, J.K. Managing Geographic Information Systems. Second edition. 2007. Guilford Press, New York.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants R01AA016161 and R01AA10305 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

References

- 1.Mark DM. Geographic information science: Defining the field. In: Duckham M, Goodchild MF, Worboys MF, editors. Foundations of Geographic Information Science. Taylor Francis; New York: 2003. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickles J. Arguments, debates and dialogues: The GIS-social theory debate and concerns for alternatives. In: Longley P, Goodchild M, Maguire D, Rhind D, editors. Geographical Information Systems: Principles, Techniques, Management, and Applications. Wiley; New York: 1999. pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- 3.GIS World. Roger Tomlinson: The father of GIS. GIS World; 1996. Apr, Interview; pp. 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlinson R. Geographic information systems – a new frontier. In: Peuquet DJ, Francis D, editors. Introductory Readings in Geographic Information Systems. Marble CRC Press; New York: 1980. pp. 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chrisman NR. Charting the Unknown: How Automated Mapping Became GIS at the Harvard Lab. ESRI Press; Redlands: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. Geographic Base File/Dual Independent Map Encoding (GBF/DIME), 1980 [Computer file]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census [Producer], 1980. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [Distributor], 1985.

- 7.ESRI: History [Internet] Redlands, CA: ESRI.com; 2008. [cited 2008 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.esri.com/company/about/history.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kidder T. The Soul of a New Machine. Back Bay Books; Boston: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marx RW. Cartography and Geographic Information Systems. 1. Vol. 17. 1990. The census bureau’s TIGER system (special issue) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wieczorek WF, Hanson CE. New modeling methods. Alcohol Health Research World. 1997;21(4):331–339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wieczorek WF. Using geographic information systems for small area analysis. In: Wilson RE, Dufour MC, editors. The Epidemiology of Alcohol Problems in Small Area. NIH National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda: 2000. pp. 137–162. (NIH Pub. No. 00–4357) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo CP, Yeung AKW. Concepts and Techniques of Geographic Information Systems. Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tait M. Implementing geoportals: applications of distributed GIS. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems. 2005 Jan;:33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhowmick T, Griffin AL, MacEachren AM, Kluhsman BC, Lengerich EJ. Informing geospatial toolset design: understanding the process of cancer data exploration and analysis. Health & Place. 2008;14(3):576–607. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai G, MacEachren AM, Wang H, Fuhrmann S. Natural conversational interfaces to geospatial databases. Transactions in GIS. 2005;9(2):199–221. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longley PA, Goodchild MF, Maguire DJ, Rhind DW. Geographic Information Systems and Science. John Wiley & Sons LTD; West Sussex, England: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burrough PA. Monographs on Soil and Resources Survey No. 12. Oxford Science Publications; New York: 1986. Principles of Geographic Information Systems for Land Resource Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- 18.ESRI. Understanding GIS: The ARC/INFO Method. ESRI; Redlands: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarke KC. Getting Started with Geographic Information Systems. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodchild Michael F., editor. NCGIA Core curriculum in GIScience [Internet] What is geographic information science? Santa Barbara: 1997. Oct. 7, [cited 2008 Aug 8]; Available from: http://www.ncgia.ucsb.edu/giscc/units/u002/u002.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong DWS. The modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP) In: Janelle DG, Warf B, Hansen K, editors. WorldMinds: Geographical perspectives on 100 problems. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht: 2003. pp. 571–575. [Google Scholar]

- 22.USGS National geospatial program [Internet] Washington, DC: usgs.gov; 2008. [cited 2008 Aug 5]. Available from: http://usgs.gov/ngpo/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tobler WR. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Economic Geography. 1970;46(2):234–240. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cressie NAC. Statistics for Spatial Data. Revised. Wiley; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moran PAP. Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika. 1950;37:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacEachren AM, Gahegan M, Pike W, Brewer I, Cai G, Lengerich E, Hardisty F. Geovisualization for knowledge construction and decision support. IEEE Computer Graphics & Applications. 2004;24(1):13–17. doi: 10.1109/mcg.2004.1255801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffin AM, Hardisty F, Steiner E, Li B. A comparison of animated maps with static small-multiple maps for visually identifying space-time clusters. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2006;96(4):740–753. [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacEachren AM, Wachowicz M, Edsall R, Haug D. Constructing knowledge for multivariate spatiotemporal data: integrating geographic visualization with knowledge discovery in database methods. Int J of Geographical Information Science. 1999;13(4):311–334. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller HJ, Han J, editors. Geographic Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. Taylor & Francis; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carr DB, White D, MacEachren AM. Conditioned choropleth maps and hypothesis generation. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2005;95(1):32–53. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boots B, Getis A. Point Pattern Analysis. Sage Publications; Newbury Park: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchial Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Sage Publications; Newbury Park: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arctur D, Zeiler M. Designing Geodatabases: Case Studies in GIS Data Modeling. ESRI, Inc; Redlands: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anselin L. Local indicators of spatial association-LISA. Geographical Analysis. 1995;27(2):93–115. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Besag J, Newel J. The detection of clusters in rare diseases. J Royal Stat Society, Series A. 1991;154(1):143–155. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kulldorff MA. A spatial scan statistic. Communications in Statistics: Theory and Methods. 1997;26(6):1481–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kulldorff MA, Feuer EJ, Miller BA, Freedman LS. Breast cancer clusters in the northeast United States: A geographic analysis. Am J Epidemilogy. 1997;146(2):161–170. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanson CE, Wieczorek WF. Alcohol mortality: A comparison of spatial clustering methods. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(5):791–802. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mostashari F, Kulldorff M, Hartman JJ, Miller JR, Kulasekera V. Dead bird clusters as an early warning system for West Nile Virus activity. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(6):641–646. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.020794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulldorff M, Nagarwalla N. Spatial disease clusters: Detection and inference. Stat Med. 1995;14(8):799–810. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kulldorff M. Information Management Service Inc. SaTScan v4.0: Software for the Spatial and Space-time Scan Statistics [Internet] 2003 [cited 2008 Aug 7]. Available from: http://www.satscan.org/