Abstract

Acne vulgaris is one of the most common conditions for which all patients, including those with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI), seek dermatological care. The multifactorial pathogenesis of acne appears to be the same in ethnic patients as in Caucasians. However, there is controversy over whether certain skin biology characteristics, such as sebum production, differ in ethnic patients. Clinically, acne lesions can appear the same as those seen in Caucasians; however, histologically, all types of acne lesions in African Americans can be associated with intense inflammation including comedones, which can also have some degree of inflammation. It is the sequelae of the disease that are the distinguishing characteristics of acne in skin of color, namely postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and keloidal or hypertrophic scarring. Although the medical and surgical treatment options are the same, it is these features that should be kept in mind when designing a treatment regimen for acne in skin of color.

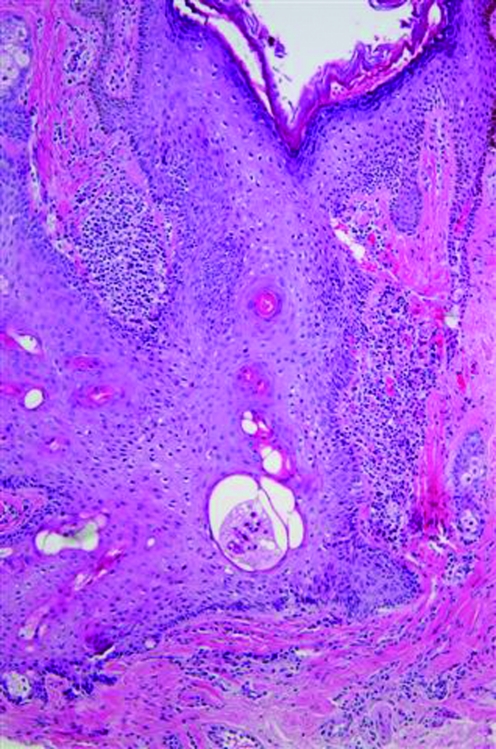

Acne vulgaris is one of the most common conditions for which patients seek dermatological care and is estimated to affect between 40 and 50 million individuals in the United States.1 Skin of color patients (typically Fitzpatrick skin types [FST] IV–VI) (Figures 1a–1c) are no exception, with numerous epidemiological studies of skin diseases in ethnic patients ranking acne vulgaris among the leading reasons for seeking treatment. In a 2007 study,2 the diagnosis codes of visits from patients of different racial/ethnic backgrounds seen at a hospital-based dermatology practice in New York City were compared to those of Caucasian patients seen during the same study period. Although subsequent visits from the same patient were included in the results, acne was the most common reason for visits for both African American (28.4%) and Caucasian (21%) patients. Multiple other epidemiological studies dating back to 1908 have consistently found acne to be one of the most common dermatoses among black patients.3–7 The same holds true for Latino patients, as a study of 3,000 Latino patients seen in a private practice setting and hospital-based clinic showed acne to be one of the three most common diagnoses in this patient population.8 A study of 74,589 Asian patients conducted in Singapore showed similar results as well.9 Acne vulgaris was the second most common diagnosis behind dermatitis among a patient population primarily comprising patients of Chinese descent (77.2%); however, 9.9 percent were of Indian descent. Acne is also included among common dermatological diseases found in Native Americans as well as Arab Americans.10,11 However, as the Singapore study shows, acne vulgaris is not a disease that is only common in ethnic populations in the United States. Its high prevalence among dermatological conditions has also been well documented in studies of various international ethnic communities, such as black populations in London, adolescents in Hong Kong or Peru, and the Bantu population in South Africa.12–15 It is important that all dermatologists be knowledgeable of the special considerations in treating dark-skinned patients with acne and also recognize the role cultural issues play in healthcare. This article reviews the pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and treatment of acne vulgaris in ethnic skin.

Figures 1a–1c.

Acne vulgaris in Fitzpatrick skin types IV (a), V (b), and VI (c). Note the postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, particularly in the higher skin phototypes.

Pathogenesis

The development of acne is a multifactorial process involving both endogenous and exogenous factors. Acne begins with the retention of desquamated keratinocytes within the pilosebaceous unit leading to follicular plugging (microcomedo), and as the keratinocytes and sebum continue to accumulate, the microcomedo wall eventually ruptures, leading to inflammation.16 Propionibacterium acnes, an anaerobic/microaerophilic, Gram-positive rod, resides within the sebaceous follicle and also incites an inflammatory response by acting on toll-like receptor-2, which may stimulate the secretion of cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 by follicular keratinocytes and IL-8 and -12 in macrophages.16,17 Other contributing factors include hormonal influences from estrogen and androgens, such as dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), which has been shown to increase sebum production in prepubescent children leading to acne.16,18 Genetic factors may also play a role in the development of acne.19,20 He et al21 published a study in 2006 showing a possible association between the CYP17-34T/C polymorphism and the development of severe acne in Chinese patients. However, further studies are needed to evaluate the exact roles played by hormones, particularly estrogen, and genetics in the development of acne.

Currently, it is believed that acne in skin of color develops largely by the same pathogenesis that occurs in Caucasian patients. However, there is controversy over whether differences exist in certain biological characteristics of skin (such as sebum production and bacterial colonization) among various racial/ethnic groups. Several studies have been published evaluating racial/ethnic differences in sebaceous gland size and activity compared to Caucasians.22,23 However, results have been contradictory. The most recent study in 2004 by Grimes et al24 evaluated 18 African American and 19 Caucasian patients for differences in certain skin surface properties, such as sebum level, pH, moisture content, and barrier function. Using a Sebumeter® SM810 (Courage-Khazaka, Köln, Germany), the authors found no significant differences in sebum production between African-American and Caucasian patients. Another study by Warrier et al25 examined facial skin microflora in 30 African-American and 30 Caucasian women. The authors found a higher density of P. acnes in African-American patients compared to Caucasian patients; however, the results were not statistically significant.

Clinical Manifestations

The active acne lesions in ethnic patients can clinically appear similar to those seen in Caucasian patients. Dark-skinned patients can develop inflammatory papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts, and it is these inflammatory lesions that promote the development of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), scarring, and keloids. Inflammatory papules in lighter-skinned patients typically have an associated erythema; however, in darker skin phototypes, these lesions can also develop an overlying hyperpigmentation, mimicking PIH, but the distinction is made upon palpation. Nodulocystic acne (Figure 2) is thought to be less common in African Americans than Caucasians based on a study published in 1970 by Wilkins et al26 of 4,654 incarcerated men. Rates of nodulocystic acne were significantly lower in African-American subjects. However, Hispanics and Asians are thought to have similar prevalence rates of nodulocystic acne as Caucasians, although supporting evidence is lacking.27,28 A study of acne in skin of color by Taylor et al27 showed cystic lesions to be present in 18 percent of African-American (n=239), 25.5 percent of Hispanic (n=55), and 10.5 percent of Asian (n=19) patients. However, larger studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Figure 2.

Fitzpatrick skin type V patient with nodulocystic acne. Note the postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

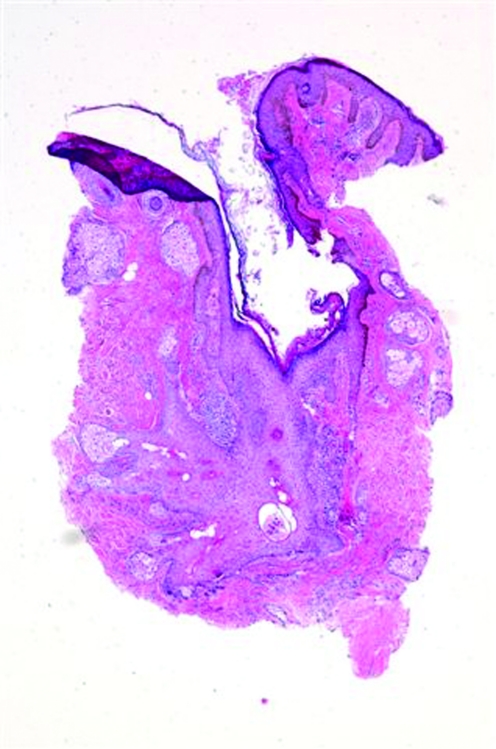

skin of color patients can also develop open and closed comedones or noninflammatory lesions (Figure 3). However, an interesting study by Halder et al29 of 30 African-American female patients with acne showed marked inflammation in all types of lesions. The histology from biopsy specimens showed some degree of inflammation even around simple comedones that showed no evidence of inflammation on clinical exam. In addition, there was also extensive inflammation surrounding papules and pustules, inflamed tissue far away from the lesion, foreign body granulomas with giant cells, and epidermal melanin granules and melanophages extending into the reticular dermis in areas of hyperpigmentation, which was not consistent to what was seen clinically. The authors postulated that this heightened inflammatory response may be a major reason African Americans with even mild-to-moderate acne still develop hyperpigmented macules. Of note, biopsies were taken by the authors of this article of two recalcitrant open comedones without clinical evidence of inflammation in an African-American patient. Histological exam showed dilated, distorted, keratin-filled follicles consistent with comedones and patchy chronic inflammation similar to the above findings (Figures 4a and 4b). Therefore, larger studies are needed to determine the prevalence and etiological factors of inflammatory comedonal acne not only in African Americans, but also in other ethnic groups and Caucasians, if present.27

Figure 3.

Comedonal acne. Note the presence of both open and closed comedones.

Figures 4a and 4b.

Histological examination of an open comedo. Note the dilated, distorted, keratin-filled follicle and the presence of patchy chronic inflammation. There was no evidence of inflammation on clinical exam.

Skin and hair care products can also be important etiological factors in the process of comedogenesis in ethnic patients. In 1970, Plewig et al30 described pomade acne as an eruption of mostly closed comedones over the forehead and temples of African-American subjects secondary to long-term daily use of oils and emollients for moisturizing the hair and scalp (Figure 5). Biopsies were also obtained and the histological picture was very similar to acne vulgaris, which showed follicular plugging; a few comedones were also noted to have inflammatory changes. These thick emollients typically contain a mixture of petrolatum, lanolin, and oils (mineral, vegetable, or animal).31–33 However, with the introduction of chemical relaxing, hair with very tight curl patterns is now more manageable; therefore, thick pomades are less commonly used today.34 The current trend is the use of light liquid moisturizing agents, particularly those containing silicone derivatives, due to their ability to provide shine and moisture without the greasiness.34 Acne cosmetica was initially coined by Kligman et al35 in 1972 to describe the formation of comedones from the use of cosmetic products containing certain ingredients. This concept is particularly relevant to the skin of color patient, as oftentimes many darker-skinned patients will use opaque and oil-containing make-up to camouflage not only the acne, but more importantly, the PIH. However, recommending cosmetics may be difficult, as one study by Draelos et al36 showed that cosmetic products containing comedogenic ingredients are not necessarily comedogenic. Patient evaluations of products can be helpful, but many times the only way to know whether an individual patient will not have a problem with a cosmetic is for the patient to use the product.37

Figure 5.

Patient with pomade acne eruption of closed comedones over the forehead and temple regions

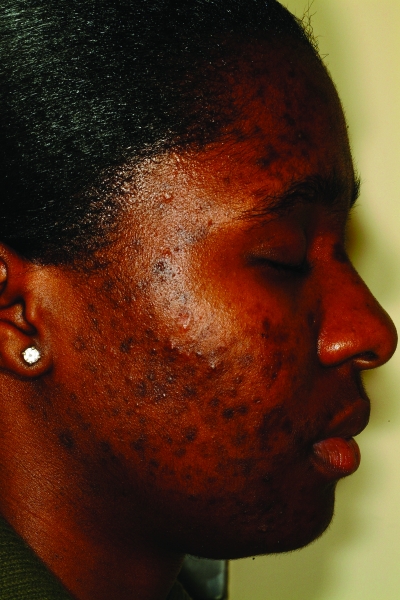

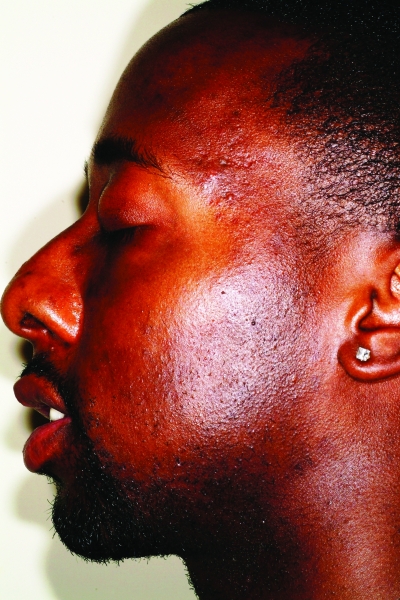

In skin of color patients, the most disturbing feature of acne is not the active lesion itself but the resulting PIH.27,38–40 This is very important to keep in mind when creating a treatment plan for these patients. PIH manifests as hyperpigmented macules, and it appears that the higher the skin phototype, the more intense the pigmentation, although studies are needed to confirm this finding (Figures 6a and 6b). PIH can persist for months to years after the initial lesion has cleared.39 The same epidemiological studies in skin of color mentioned above also found pigmentary disorders other than vitiligo to be very common presenting complaints.2,7,8 In fact, Taylor et al27 found acne hyperpigmented macules present in 65.3 percent of African-American, 52.7 percent of Hispanic, and 47.4 percent of Asian patients with acne. Keloid formation (Figure 7) and hypertrophic scarring are other sequelae of acne more commonly seen in the skin of color populations. Another complication of acne is persistent erythema once the acne lesion has resolved (Figure 8). This sequela is typically more noticeable in ethnic patients with lighter skin (FST IV and V) than dark-skinned (FST VI) patients, as the increased pigmentation can mask the erythema.

Figures 6a and 6b.

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type V (a) and VI (b). Note the greater intensity of pigmentation with darker skin

Figures 7a and 7b.

Keloid formation on the chest (a) and along the mandible (b) from acne vulgaris

Figure 8.

Multiple areas of persistent erythema on the cheek after acne

Treatment

The first step in the management of acne vulgaris in skin of color patients is to take a thorough medical history of the patient's skin and hair care products and practices (Table 1). One of the objectives of the history is to evaluate the patient's potential for skin irritation. For example, the skin-care practices listed in an epidemiological study in Arab Americans included the use of olive oil to moisturize the skin, hair oils and pomades, a mixture of pure honey and sugar to exfoliate, natural lemon juice or a milk and cucumber blend to wash the face, or a mixture of herbs or Dead Sea clay to make facial masks.11 Also, in the United States, the demand for bleaching creams has facilitated a rise in the use of illegally obtained, high-concentration hydroquinone products or high-potency corticosteroids that are available over the counter in ethnic stores in major metropolitan cities.41 Many dermatologists may not be aware of these cultural practices; therefore, it is important to learn about how ethnic patients care for their skin and hair as it may impact the planned treatment strategy.

Table 1.

Important questions to ask during the medical history

| QUESTIONS SPECIFIC FOR ACNE IN SKIN OF COLOR | EVALUATES FOR |

|---|---|

| What is your skin type? Normal, dry, oily, combination? Any seasonal change? | Irritation potential |

| Do you use any brushes, scrubs, or sponges (e.g., loofah sponge) to wash your face? | Irritation potential |

| Do you use any ethnic skin products? Over-the-counter bleaching creams? Benzoyl peroxide products? | Irritation potential |

| Have you previously used any prescription acne medications? Did you have any success or reactions (i.e., irritant contact dermatitis) with the medication? | Irritation potential |

| Do you wear sunscreen daily? | Risk for worsening PIH |

| What types of hair care products do you use? Oils, emollients? | Pomade acne |

| What types of cosmetics do you use? Make-up removers? | Acne cosmetica |

| Any personal or family history of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency? | Topical dapsone |

| What other medications are you currently taking? Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole? Antimalarials? | Topical dapsone |

| Do you have a history of keloidal or hypertrophic scarring? | Risk for acne surgery, chemical peeling, or laser therapy |

PIH = Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

Another aspect to be mindful of when designing a treatment regimen for skin of color patients is the importance of addressing PIH. The early initiation of PIH treatment will help hasten its resolution and prevent further darkening. However, a delicate balance exists, as cutaneous irritation from the treatment itself can cause or exacerbate PIH in these patients.39 An irritant contact dermatitis in skin of color patients can be signaled by the presence of erythema (Figure 9a), hyperpigmentation (Figure 9b), or hypopigmentation (Figure 9c). However, there are a multitude of depigmenting agents for the treatment of PIH including those with dual efficacy, which treat acne as well. It is also imperative to emphasize the importance of photoprotection in the treatment and prevention of PIH. In fact, a study analyzed data from the 1992 National Health Interview Survey of 1,583 African Americans regarding sun-protection behaviors and found only nine percent of respondents were very likely to use sunscreen versus 81 percent who were unlikely to use it.42 Therefore, patient education is a key component to successful treatment.

Figures 9a, 9b, 9c.

Erythema (a), hyperpigmentation (b), hypopigmentation (c) resulting from an irritant contact dermatitis in skin of color patients. Figures 9b and 9c are reprinted with permission from Dermatologic Therapy. 2004;17(2):184–195.© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Medical therapy. Topical agents. Retinoids. In general, topical retinoids are typically first-line therapy for mild-to-moderate acne in skin of color.38,39 (Figures 10a and 10b). Retinoids are a class of drugs that are structural and functional vitamin A analogues. These agents exert a comedolytic effect and possess anti-inflammatory and anti-keratinization properties.43 Of particular significance to skin of color patients is the ability of retinoids to treat both acne and PIH. By increasing epidermal turnover, these agents facilitate melanin dispersion and removal.44 The most common agents used are tretinoin, a first-generation retinoid, and adapalene and tazarotene, both third-generation synthetic retinoids (Table 2). The concern with using retinoids in skin of color is due to its potential to induce an irritant contact dermatitis, which could lead to PIH. However, retinoids can still be used not only safely but effectively in this patient population by starting at lower concentrations and titrating up based on treatment response and choosing more tolerable formulations (i.e., creams over gels). Tretinoin can also be formulated in a microsponge delivery system, which allows for the controlled release of tretinoin, thereby, causing less irritation.38,45 Table 3 summarizes the clinical studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of topical retinoids in skin of color patients.

Figures 10a and 10b.

Skin of color patient with acne and PIH before (a) and after (b) 7 months of therapy with tazarotene 0.1% applied in the mornings and a fixed combination lightening agent (fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%, hydroquinone 4%, and tretinoin 0.05% cream) applied in the evenings

Table 2.

Available retinoids marketed in the United States

| RETINOID | AVAILABLE FORMULATIONS | MANUFACTURER |

|---|---|---|

| Tretinoin | ||

| Generic | 0.025%, 0.05%, 0.1% cream 0.01%, 0.025% gel |

Rouses Point Pharmaceuticals (Cranford, NJ) |

| Atralin | 0.05% aqueous gel | Coria Laboratories (Fort Worth, TX) |

| Retin-A Micro | 0.04%, 0.1% (microsphere gel or microsphere gel pump) | OrthoNeutrogena (Los Angeles, CA) |

| Tretin-X | 0.025%, 0.05%, 0.1% cream 0.01%, 0.025% gel |

Triax Pharmaceuticals (Cranford, NJ) |

| Adapalene (Differin) | 0.1% cream 0.1%, 0.3% gel |

Galderma Laboratories (Forth Worth, TX) |

| Tazarotene (Tazorac) | 0.05%, 0.1% cream 0.05%, 0.1% gel |

Allergan (Irvine, CA) |

Table 3.

Clinical studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of topical retinoids for acne in skin of color

| AGENT(S) | AUTHOR | SKIN-OF-COLOR PATIENTS (FST) | STUDY DESIGN | EFFICACY | SAFETY | PIH EFFICACY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adapalene 0.1% vs. tretinoin 0.025% | Goh et al107 | N=73, 19 Chinese (III–IV), 20 Indian (V–VI), 20 Malay (IV–V), 14 Caucasian (I–III) |

Randomized, investigator-blinded, split-face and forearm tolerability study | NS | Irritation potential of adapalene 0.1% was significantly lower than tretinoin 0.025% in all tolerability assessments for face and forearm. Order or tolerance: Chinese (most susceptible to irritation) > Indians > Malays > Caucasians (least susceptible) |

NS |

| Adapalene 0.1% vs. tretinoin 0.025% | Tu et al108 | N=150, all Chinese (I–IV) | 8-week, randomized, double-blind, comparison study | Equivalent efficacy: >69% reduction in total, inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts. >70% in both groups had complete clearance or marked improvement. | Local irritation (erythema, scaling, burning, pruritus, dryness) were mild but more common with tretinoin (45.7%) than adapalene (32.4%). | NS |

| Adapalene 0.1% | Jacyk et al109 | N=65, 64 African, 1 Indian | 12-week, open-label study | Significant reductions in mean inflammatory, noninflammatory, and total lesion counts from baseline to endpoint (P<0.01). | <5% reported moderate-to-severe skin irritation. | Yes |

| Adapalene 0.1% vs. vehicle gel | Kawashima et al110 | N=193, all Japanese | 12-week, randomized, investigator-blinded, vehicle-controlled study | Median percent reduction of total lesion counts at endpoint was significantly greater with adapalene (63.2%) compared to vehicle (36.9%) (P<0.0001). Significant reductions in total (P<0.0001), inflammatory (P=0.01), and noninflammatory (P<0.001) lesions with adapalene over vehicle at endpoint. | 32.2% experienced AEs related to study drug, 56% in adapalene-treated group, 8.1% in vehicle-treated group. Most common AE: dryness. All dermatological AEs were transient and mild to moderate. |

NS |

| Tazarotene 0.05% | Grimes PE111 | N=14, 10 African American, 4 Hispanic, (all V–VI) | 8-week, pilot study | Significant reductions in mean inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts from baseline to endpoint. | No significant changes in mean pigmentary intensity in patients' skin and no irritation. Not likely to cause irritation-induced hyperpigmentation. | Yes* |

| Tazarotene 0.1% | Saple et al112 | N=126, all Asian Indian | 14-week, open-label study | Significant reductions in mean inflammatory, noninflammatory, and total lesion counts from baseline to endpoint. Complete to moderate clearing in 93.6%. | AEs in 11.9%; Pruritus most common (4.8%). | NS |

FST= Fitzpatrick skin type

AEs= Adverse events

NS= Not stated

Following study showed tazarotene to be effective for acne-induced PIH in darker skin. Grimes PE, Callender VD. Tazarotene cream for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and acne vulgaris in darker skin: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study. Cutis. 2006;77:45–50.

Antimicrobials. Generally, topical antimicrobials are used in combination therapy for milder cases of acne in skin of color.38 Erythromycin, a macrolide, and clindamycin, a lincosamide, both inhibit bacterial protein synthesis and possess anti-inflammatory properties.38,46 However, these agents are typically used concurrently with benzoyl peroxide (BPO), an oxidizer of bacterial proteins, to reduce the development of bacterial re-sistance,47 and clinical studies have shown increased efficacy with combination therapy.48–50 Ko et al51 conducted a 12-week, randomized, open-label, com-parative study of clindamycin/ benzoyl peroxide (C/BPO) versus adapalene in 69 Korean patients with mild-to-moderate acne. Although both treatments were effective in reducing acne lesion counts and severity score, C/BPO produced a significantly greater reduction in inflammatory lesions than adapalene. Patients tolerated both medications equally well and had minimal side effects. BPO is also widely used as monotherapy and available in lower concentrations over the counter in a variety of formulations, such as creams, washes, foams, pads, and facial masks. However, BPO can be very drying to skin of color and can also cause an irritant contact dermatitis; therefore, it is best to start with lower concentrations and cream or lotion formulations in skin of color patients.39 Sodium sulfacetamide 10%, in the class of sulfonamides, is another topical agent that is typically formulated with sulfur (1–5%) in a cleanser, lotion, cleansing cloths, and topical suspension to treat acne.46

Other topical agents. Azelaic acid (AA), a dicarboxylic acid, is produced from the organism responsible for Pityriasis versicolor and is useful in the treatment of acne. Formulated in a 20% cream, AA is often used concomitantly with other topical agents, such as BPO, antibiotics, or retinoids, for greater efficacy.52 AA may be especially suited for skin of color patients given its low irritation potential and its ability as a dicarboxylic acid to inhibit tyrosinase, an enzyme necessary for the production of melanin, thereby treating the acne as well as the PIH.39,53

Salicylic acid (SA) is a beta-hydroxy acid that is available over-the-counter in concentrations up to 2% in a wide variety of formulations. Its efficacy in acne stems from its lipophilic nature, which allows it to penetrate into comedones and its mild anti-inflammatory properties.16,54 However, more clinical studies are needed evaluating the safety and efficacy of these agents in skin of color.

Dapsone, a sulfone, possesses both antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, and is used today to treat a wide range of dermatoses.55 Its efficacy in the treatment of acne was first noticed when patients with leprosy, who also had acne, were treated with systemic sulfones and experienced an improvement in their acne.56 Oral dapsone has not been widely used for acne due to systemic toxicities, but studies have shown that topical 5% dapsone gel is both safe and effective for acne.57,58 Of specific concern for skin of color patients with oral dapsone was the development of hemolytic anemia in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. This enzyme deficiency is particularly common in patients of African, South Asian, Middle Eastern, and Mediterranean descent, and is estimated to affect about 1 in 10 African-American males in the United States.59,60 A pharmacokinetic study has shown that the total systemic exposure to dapsone and its metabolites were approximately 100-fold less for topical dapsone than for oral dapsone even in the presence of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX), which increases systemic absorption of dapsone,61 and plasma dapsone levels reached a steady state and did not increase with prolonged treatment. In fact, when co-administered with (TMP/SMX), the topical dapsone dose is approximately 1% of that from the 100mg oral dose.62 Piette et al63 conducted a hematological safety study of topical dapsone in 64 ethnic patients with G6PD deficiency and acne. There was a 0.32g/dL drop in hemoglobin concentration from baseline to two weeks of topical dapsone treatment; however, this finding was not accompanied by abnormalities in other laboratory indicators of hemolysis (i.e., bilirubin, haptoglobin, reticulocyte count) or clinical signs and symptoms of hemolytic anemia. Therefore, the authors concluded that the risk of hemolytic anemia with topical 5% dapsone gel is very small for patients with G6PD deficiency and can be used safely in all patients.63 Also of note is the fact that topical dapsone followed by benzoyl peroxide has been reported to cause a temporary yellow or orange discoloration of the skin or facial hair.62

Combination therapy. The multifactorial etiologies of acne (i.e., hyperkeratinization, increased sebum, P. acnes, and inflammation) as well as the prevention of bacterial resistance all facilitate the need for new developments in combination acne therapy. Combining agents that target the different etiological factors of acne can help increase efficacy and response time.64 There have been multiple clinical studies showing the efficacy of using two or three different anti-acne agents, such as BPO, a topical antibiotic, and a topical retinoid; however, the majority of patients included in these studies were Caucasian.65–67 Individual agents can be applied at different times of the day in an effort to reduce the risk of irritation, which is particularly important for skin of color patients.64

Topical antibiotics, such as clindamycin and erythromycin, have been formulated with BPO to help reduce the risk of antibiotic-resistant P. acnes. Recently, however, more fixed-combination agents are available that combine topical antimicrobials with retinoids, such as adapalene 0.1%/BPO 2.5% and clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/tretinoin 0.025% (Table 4). These agents offer greater convenience by providing comedolytic, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties in a single formulation. Clinical studies with the newer fixed-combination agents in skin of color are currently underway. Even other classes of topical anti-acne agents are now being investigated for their utility in combination acne therapy. A recent clinical study evaluated the safety and efficacy of dapsone in combination with adapalene or BPO and found both combinations to be safe and well tolerated in a study population comprising 40-percent ethnic patients.68

Table 4.

Commonly used fixed-combination agents

| AVAILABLE FORMULATIONS | TRADE NAME (MANUFACTURER) |

|---|---|

| Clindamycin phosphate 1.2% + benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel | Acanya (Coria Laboratories, Fort Worth, Texas) |

| Clindamycin 1% + benzoyl peroxide 5% gel | Benzaclin (Dermik Laboratories, Bridgewater, New Jersey) Duac (Stiefel Laboratories, Coral Gables, Florida) |

| Clindamycin phosphate 1.2% + tretinoin 0.025% gel | Ziana (Medicis, Scottsdale, Arizona) |

| Adapalene 0.1% + benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel | Epiduo (Galderma Laboratories, Fort Worth, Texas) |

| Erythromycin 3% + benzoyl peroxide 5% gel | Benzamycin (Dermik Laboratories, Bridgewater, New Jersey) |

Oral agents. Retinoids. Isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) is an oral retinoid that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat severe nodulocystic acne and is the treatment of choice for this type of acne in skin of color.43,69 Although its exact mechanism of action is unknown, isotretinoin is known to affect many of the etiological factors of acne by decreasing sebum production, comedogenesis, and P. acnes colonization.43 Kelly et al69 conducted a study to determine the efficacy of isotretinoin in African-American patients with recalcitrant nodulocystic acne. The authors reported specific treatment effects with isotretinoin that occurred in blacks, such as an early onset flare in areas of the face that were void of lesions prior to treatment, particularly the temporal and submandibular areas, improvement in PIH, and an ashen or grayish facial hue due to the drying and desquamative effects of the drug.69 Therefore, it is important for successful treatment to educate the patient regarding the clinical course with isotretinoin and encourage them to continue with the treatment regimen despite early acne flares. The above study by Kelly et al also noted a dramatic improvement in self esteem and social interactions in those patients who experience a resolution of their acne.69 In addition to African Americans, other clinical studies have also demonstrated the safety and efficacy of isotretinoin in Middle Eastern,70,71 Asian,72 and Asian-Indian73 patient populations. Although isotretinoin can be highly effective in treating severe acne, it is also associated with numerous mucocutaneous and serious systemic toxicities (e.g., teratogenicity, dyslipidemia, pancreatitis, and hepatotoxicity); therefore, careful patient selection and monitoring is important.43

Antimicrobials. In skin of color patients, as with Caucasian patients, oral antibiotics are typically reserved for patients with moderate-to-severe inflammatory acne, most of whom have likely failed prior treatment with topical agents alone.16,39,64 The most common classes of oral antibiotics used in acne include macrolides (i.e., erythromycin) and tetracyclines (i.e., tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline), which both work by inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis, and sulfonamides (i.e., TMP/SMX), which inhibit bacterial DNA synthesis.46 Not only do these agents inhibit the growth of P. acnes but tetracyclines and erythromycin are also effective in acne due to their intrinsic anti-inflammatory properties.46,64 As with topical antibiotics, oral agents can also be used in combination with topical retinoids. Clinical studies have shown some success with the combinations of doxycycline plus adapalene74 and minocycline plus tazarotene75; however, more studies are needed, particularly in skin of color patients. In designing a treatment regimen, it is important to weigh the benefits of clinical efficacy versus the risks of bacterial resistance and the side effects profile of the antibiotic.

As with other systemic therapies, oral antibiotics can cause a wide range of side effects from gastrointestinal upset with erythromycin or tetracycline to the uncommon Stevens-Johnson syndrome with TMP/SMX or a lupus-like syndrome with minocycline.46,76 Doxycycline can cause a photosensitivity reaction; however, in the author's opinion, this reaction is uncommon in dark-skinned patients. Tetracyclines, particularly minocycline, have been shown to cause rare but serious hypersensitivity reactions, including urticaria, hepatitis, and pneumonitis, which may occur more frequently77 and have a prolonged course78 in black patients although further studies are needed. Muller et al79 conducted a study on the susceptibility of ethnic groups to Drug Hypersensitivity Syndrome (DHS) in a mostly Afro-Caribbean study population. The annual incidence rate was approximately 1 in 100,000, and of the 28 cases included in the study, 14 percent of cases were likely caused by minocycline. Although no definite conclusions could be drawn regarding increased susceptibility in ethnic patients, DHS was the most frequent type of severe drug reaction in this population. Minocycline-induced DHS has also been reported in a Japanese patient.80 Other adverse effects with minocycline include a blue/black-grey discoloration of the skin, which has been reported in a Hispanic patient,81 oral mucosa, sclera, teeth, and nails82,83 as well as the thyroid, heart valves, and bones.84–86 Again, in the author's opinion, this complication does not appear to be common in skin of color.

Other medical therapies. In treating all patients with acne, hormonal factors should not be overlooked, particularly in women with hirsutism. The increased sebum production stimulated by androgens can be addressed with anti-androgen agents, such as spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, and oral contraceptives.17 Other agents for the medical treatment of acne that are currently in different stages of development include retinoic acid metabolism blocking agents, ectopeptidase inhibitors, 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors, and antisense oligonucleotides.17

Surgical therapy. Chemical peels. Chemical peeling, like retinoids, in skin of color patients is another therapeutic option that can address both acne and PIH simultaneously. Patients with FST IV to VI typically undergo superficial or medium-depth chemical peels. Their response to chemical peeling may vary and thus the selection of the peeling agent must be done with caution. There have been a number of clinical studies that show the efficacy of certain superficial chemical peels specifically in skin of color patients (Table 5). Glycolic acid (GA) is a naturally occurring alpha-hydroxy acid that works by inducing epidermolysis, dispersing basal layer melanin, and increasing dermal collagen synthesis.87,88 GA peels utilize concentrations ranging from 20 to 70 percent and require neutralization to terminate the peel. Salicylic acid (SA) causes keratolysis by disrupting intercellular lipid linkages between epithelioid cells.87,89 Superficial SA peels are usually performed with strengths ranging from 20 to 30 percent without the need for neutralization. Jessner's solution is a combination of 14g resorcinol, 14g salicylic acid, and 14g lactic acid in 95% ethanol, which causes keratolysis by decreasing corneocyte cohesion.90 It was formulated as a combination peel to decrease the concentration of any one agent used in the solution, thereby decreasing the risk for side effects while also producing a synergistic effect.87,90

Table 5.

Clinical studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of chemical peels for acne in skin of color

| AGENT | AUTHOR | SKIN-OF-COLOR PATIENTS (FST) | STUDY DESIGN | EFFICACY | SAFETY | PIH EFFICACY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA 35% vs. 20% SA-10% MA | Garg et al113 | N=44, all Asian Indian (IV-VI) | Two groups: Six peels at two-week intervals | Both agents were effective but SA-MA peel had greater efficacy for active acne lesions (P<0.001) and hyperpigmentation (P<0.001) | 17.3% had burning or stinging sensation. Desquamation more common with GA. Dryness more common with SA-MA | Yes |

| GA 70% vs. Jessner's | Kim et al114 | N=26, all Korean (III-IV) | Split-face: Three peels at two-week intervals | Both sides showed improvement in acne grade score; however, no statistically significant difference between the peels | Acute eczema (GA), exfoliation, which was noted to persist longer after the Jessner's peel (p<0.01) | NS |

| GA 35%, 50% | Wang et al115 | N=40, all Taiwanese (IV) | Two groups: Four peels at three-week intervals | All patients used a 15% GA home product for one week prior to peeling. Significant reduction in the number of comedones, papules, and pustules. Improvement in skin texture and appearance and smaller pore size. | 5.6% of patients developed side effects including PIH (3), mild local herpes simplex infection (3), and mild skin irritation (3) Some had acne flare after first treatment |

Yes |

| SA 30% | Dainichi et al116 | N=42, all Japanese | 42 survey respondents after SA peel | Majority of patients noted a clinical improvement in acne, satisfaction with the treatment, and a spontaneous improvement in skin texture and color | Side effects were minimal | NS |

| SA 30% | Hashimoto et al117 | N=16, all Japanese | Five peels at two-week intervals | There was a 75% reduction (p=0.001) in the comedone count from baseline to the endpoint of the study and improvement in the comedogenic acne severity grade in all patients | Mild burning and erythema were noted in three patients during the procedure | NS |

| SA 30% | Lee et al118 | N=35, all Korean (III-IV) | Five peels at two-week intervals | There was a significant reduction in both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions. The mean acne grade reduction from Baseline to Week 12 was 1.29 (p<0.01).Based on pre-peel and multiple post-peel measures, skin barrier function was found to be uncompromised by repeated peels. | Most common side effect was dryness but erythema, exfoliation, burning sensation, and crusting were also noted | NS |

| SA 20–30% | Grimes et al54 | N=25, African American and Hispanic (all V-VI) Acne (9), PIH (5) |

Five peels at two-week intervals | There was a rapid resolution of papules, pustules, and comedones in acne patients. Moderate to significant improvement occurred in 89% of acne and 100% of PIH patients | Side effects were mild including crusting, dryness, transient hypo- and hyperpigmentation | Yes |

GA= Glycolic acid

SA= Salicylic acid

MA= Mandelic acid

NS= Not stated

PIH= Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

Before the chemical peel procedure, a detailed history including dermatological conditions, current oral and topical medications used, past reactions to other cosmetic procedures, a history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, keloids, hypertrophic scarring or PIH, and a skin examination should be obtained. It is not uncommon for darker phototypes to develop transient PIH after chemical peeling.39 However, this sequela can be anticipated and pre-treated with hydroquinone to minimize its intensity, and patients can be given a post-treatment course as well. Other preventive measures include starting at lower peel concentrations and titrating up based on response, performing peels at less frequent intervals (2–4 weeks), stopping retinoid therapy 5 to 7 days prior to the peel procedure, and educating the patient about the importance of sun protection.39

Lasers and light-based therapies. Lasers and light sources can be an effective adjunct to topical or systemic acne management.91 There have been numerous case reports and a few clinical studies evaluating the use of devices including blue light, diode laser, intense pulsed light (IPL), and photodynamic therapy (PDT) for the treatment of acne in skin of color.92–95 In blue light therapy, fluorescent porphyrins contained within P. acnes are targeted and killed by the blue light.92 Tzung et al92 conducted a study of 31 Taiwanese patients (FST III-IV) and found that blue light irradiation was effective in treating mild-to-moderate acne (P<0.001) but worsened nodulocystic acne. The 1,450nm diode laser heats the sebaceous gland, which may lead to reduced sebum production and thus decrease inflammatory acne lesions.93 A cooling device helps protect the epidermis from thermal injury and also decreases pain during treatment.93 The diode laser has been shown to be effective acne treatment in two clinical studies conducted in Asian patients (FST III-V) with only a few patients experiencing transient PIH or erythema.93,96 IPL may operate by similar mechanisms as the previous devices including photoinactivation of P. acnes and photothermolysis of the sebaceous glands and may also possess anti-inflammatory effects.94 Kawana et al94 conducted a study of 25 Japanese patients (FST III-IV) and found that five sessions of IPL at wavelengths of 400 to 700nm and 870 to 1200nm was effective in treating moderate-to-severe acne with the majority of patients experiencing transient erythema. However, multiple previous studies in Asian patients using different IPL parameters did not show significant improvement in acne, particularly with inflammatory lesions.97–99 Therefore, further large-scale studies are needed.

PDT uses aminolevulinic acid, a photosensitizer, as it selectively induces porphyrin fluorescence of pilosebaceous units, which targets the bacteria.100 PDT has been used successfully in Asian populations,101,102 and there is a case report describing the efficacy of PDT in an African-American patient (FST V).103 Scaling and transient hyperpigmentation were reported with PDT therapy in both populations. Larger clinical studies are still needed, particularly for higher phototypes. Photopneumatic therapy is a new treatment option for acne in which the skin is gently drawn into a handpiece allowing the mechanical removal of sebaceous content by the suction pressure, and broadband light is delivered directly to the treatment site (400–1,200nm) leading to bacterial destruction.104 This device has been shown to be effective for acne and side effects including mild erythema; however, clinical studies are needed to determine the safety and efficacy of this device in skin of color patients. As with most other surgical procedures in skin of color patients, postinflammatory hyper- and hypopigmentation and keloidal or hypertrophic scarring are important sequelae of treatment to always keep in mind. There are a number of strategies that may help reduce the risk of these complications, including obtaining an adequate medical history, performing test spots, and the use of cooling devices.105 In addition, post-operative corticosteroid injections can also be helpful in reducing the risk of these complications if erythema develops at the treatment site.

Other surgical options. The use of intralesional corticosteroid injections into inflammatory cysts or nodules can help alleviate the pain that may develop with these lesions. Triamcinolone acetonide 2.5 to 5mg/cc can be used for the injections and resolution typically occurs within 2 to 5 days.39 Higher concentrations of corticosteroid, 20 to 40mg/cc, can be used if keloids have developed and injections can be repeated every 2 to 4 weeks.39 Open or closed comedones can be manually extracted if resolution does not occur with topical retinoid therapy. Prior to acne surgery, a 6- to 8-week course of retinoid therapy can help reduce the difficulty of extracting, thereby reducing skin trauma as well as the risk of PIH.39 As with retinoids, 1 to 2 salicylic acid peels prior to acne surgery can also help ease the extraction process.

Acne management strategy in skin of color. Table 6 outlines the effective treatment options based on acne severity for skin of color patients. However, there are a few key points to emphasize for darker skin. Medical therapy should be started early in skin of color patients with acne to prevent or help decrease the severity of acne sequelae (i.e., PIH, keloids). For topical therapies with some irritation potential, start at lower concentrations and titrate up based on patient response, and choose more tolerable formulations.39 Given the lower starting doses for skin of color, treatment failures may warrant an increase in dosage or addition of another product rather than a switch to another agent. Keep those agents in mind that effectively treat both acne and PIH in a single formulation. Sun protection measures are important to the prevention and treatment of PIH as well as effective depigmenting agents.39 Combination therapy with oral antibiotics and retinoids should be prescribed to patients with inflammatory lesions, then can be discontinued once the inflammatory lesions resolve.106 If the cessation of oral antibiotics is not possible and a longer course of treatment is needed, patients should use either BPO alone or BPO/antibiotic combinations to reduce the risk of bacterial resistance. Topical retinoids can be used as maintenance therapy once antimicrobials are stopped.106

Table 6.

Effective agents for acne in skin of color

| MILD-TO-MODERATE ACNE |

|---|

| Tretinoin |

| Adapalene |

| Tazarotene |

| Clindamycin phosphate 1.2% + tretinoin 0.025% gel |

| Adapalene 0.1% + benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel |

| Clindamycin |

| Benzoyl peroxide |

| Clindamycin 1% + benzoyl peroxide 5% gel |

| Dapsone |

| Azelaic acid |

| Salicylic acid |

| Oral contraceptives (female patients) |

| Comedo extraction |

| MODERATE-TO-SEVERE ACNE |

|---|

| Tetracycline |

| Doxycycline |

| Minocycline |

| Erythromycin |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole |

| Tretinoin (in combination) |

| Adapalene (in combination) |

| Tazarotene (in combination) |

| Adapalene 0.1% + benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel |

| Clindamycin phosphate 1.2% + tretinoin 0.025% gel |

| Clindamycin 1.2% + benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel |

| Clindamycin 1% + benzoyl peroxide 5% gel |

| Oral contraceptives (female patients) |

| Comedo extraction |

| Chemical peels |

| Lasers and light-based therapies |

| NODULOCYSTIC ACNE |

|---|

| Isotretinoin |

| Oral antibiotic + topical retinoid + topical antimicrobial (agents listed above in moderate-to-severe acne) |

| Oral contraceptives (female patients) |

| Intralesional corticosteroids |

Conclusion

Acne vulgaris is one of the most common cutaneous conditions regardless of race or ethnicity. Although the pathogenesis is the same as Caucasians, there are unique characteristics in the expression of acne in skin of color, such as the presence of inflammation in “noninflammatory” lesions as well as a propensity for hyperpigmentation after the acne resolves. These clinical features and a patient's irritation potential should influence the choice of anti-acne agents used when designing a treatment regimen. There are many agents currently available that are safe and efficacious to use in skin of color including topical retinoids and antibiotics. However, there is a paucity of clinical studies that evaluate not only the safety and efficacy of acne medications in skin of color but also how the disease process manifests itself differently in ethnic skin. Future areas of exploration should examine the use of combination or new therapies in skin of color, the roles of hormones and genetics, and the contribution of possible differences in the skin biology characteristics of darker ethnic groups to the development of acne.

References

- 1.White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:S34–S37. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70442-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:38–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox H. Observations on skin diseases in the Negro. J Cutan Dis. 1908;26:67–79. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazen HH. Personal observations upon skin diseases in the American Negro. J Cutan Dis. 1914;32:705–712. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hazen HH. Syphilis and skin disease in the American Negro: personal observations. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1935;31:316–323. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy JA. Managment of dermatoses peculiar to Negroes. Arch Dermatol. 1965;91:126–129. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1965.01600080034004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halder RM, Grimes PE, McLaurin CI, et al. Incidence of common dermatoses in a predominately black dermatologic practice. Cutis. 1983;32:388–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez MR. Cutaneous diseases in Latinos. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:689–697. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chua-Ty G, Goh CL, Koh SL. Pattern of skin diseases at the National Skin Centre (Singapore) from 1989–1990. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:555–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1992.tb02717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman L. Dermatological observations on the Navaho reservation. AMA Arch Derm. 1958;77:581–588. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1958.01560050091015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Essawi D, Musial JL, Hammand A, et al. A survery of skin disease and skin-related issues in Arab Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:933–938. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Child FJ, Fuller LC, Higgins EM, et al. A study of the spectrum of skin disease occurring in a black population in south-east London. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:512–517. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeung CK, Teo LH, Xiang LH, et al. A community-based epidemiological study of acne vulgaris in Hong Kong adolescents. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:104–107. doi: 10.1080/00015550252948121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freyre EA, Rebaza RM, Sami DA, et al. The prevalence of facial acne in Peruvian Adolescents and its relation to their ethnicity. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:480–484. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park RG. The age distribution of common skin disorders in the Bantu of Pretoria, Transvaal. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:758–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1968.tb11941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaenglein AL, Thiboutot DM. Acne vulgaris. In: Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, olognia JL, editors. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier Mosby; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurokawa I, Danby FW, Ju Q, et al. New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:821–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cappel M, Mauger D, Thiboutot D. Correlation between serum levels of insulin-like growth factor-1, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and dihydrotestosterone and acne lesion counts in adult women. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:333–338. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu SX, Wang HL, Fan X, et al. The familial rish of acne vulgaris in Chinese Hans—a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:602–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goulden V, McGeown CH, Cunliffe WJ. The familial risk of adult acne: a comparison between first-degree relatives of affected and unaffected individuals. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:297–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He L, Yang Z, Yu H, et al. The relationship between CYP17-34T/C polymorphism and acne in Chinese subjects revealed by sequencing. Dermatology. 2006;212:338–342. doi: 10.1159/000092284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kligman AM, Shelley WB. An investigation of the biology of the sebaceous gland. J Invest Dermatol. 1958;30:99–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pochi PE, Strauss JS. Sebaceous gland activity in black skin. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:349–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimes P, Edison BL, Green BA, et al. Evaluation of inherent differences between African American and white skin surface properties using subjective and objective measures. Cutis. 2004;73:392–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warrier AG, Kligman AM, Harper RA, et al. A comparison of black and white skin using noninvasive methods. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1996;47:229–240. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkins JW, Jr, Voorhees JJ. Prevalence of nodulocystic acne in white and negro males. Arch Dermatol. 1970;102:631–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden F, Rahman Z, et al. Acne vulgaris in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 Suppl):S98–S106. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee CS, Lim HW. Cutaneous diseases in Asians. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:669–677. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halder RM, Holmes YC, Bridgeman-Shah S, Kligman AM. A clinicohistopathologic study of acne vulgaris in black females (abstract) J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:888. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plewig G, Fulton JE, Kligman AM. Pomade acne. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:580–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Draelos ZD. Black individuals require special products for hair care. Cosmet Dermatol. 1993;6:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goode ST. Hair pomades. Cosmet Toil. 1979;94:71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilborn WS. Disorders in hair growth in African Americans. In: Olsen EA, editor. Disorders of Hair Growth. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.; 1994. pp. 389–407. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMichael AJ. Ethnic hair update: past and present. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:S127–S133. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kligman AM, Mills OH. Acne cosmetica. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:893–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Draelos ZD, DiNardo JC. A re-evaluation of the comedogenicity concept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Draelos ZD. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. Cosmetics in Dermatology. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halder RM, Brooks HL, Callender VD. Acne in ethnic skin. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:609–615. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Callender VD. Acne in ethnic skin: special considerations for therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:184–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quarles FN, Johnson BA, Badreshia S, et al. Acne vulgaris in richly pigmented patients. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:122–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halder RM, Nandekar MA, Neal KW. Pigmentary disorders in pigmented skins. In: Halder RM, editor. Dermatology and Dermatological Therapy of Pigmented Skins. Boca Raton: CRC/Taylor & Francis; 2006. pp. 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall HI, Rogers JD. Sun protection behaviors among African Americans. Ethn Dis. 1999;9:126–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuenzli S, Saurat JH. Retinoids. In: Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, Bolognia JL, editors. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier Mosby; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orthonne JP, Passermon T. Melanin pigmentary disorders: treatment update. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:209–226. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Embil K, Nacht S. The Microsponge Delivery System (MDS): a topical delivery system with reduced irritancy incorporating multiple triggering mechanisms for the release of actives. J Microencapsul. 1996;13:575–588. doi: 10.3109/02652049609026042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lesher J, McConnell Woody C. Antimicrobial drugs. In: Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, Bolognia JL, editors. Dermatology. 2nd. ed. Elsevier Mosby; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Del Rosso JQ, Leyden JJ, Thiboutot D, et al. Antibiotic use in acne vulgaris and rosacea: clinical considerations and resistance issues of significance to dermatologists. Cutis. 2008;82(Suppl 2[ii]):5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: combined results of two double-blind investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:590–595. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT, Bojar R, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of a clindamycin phophate/benzoyl peroxide gel formulation and a matching clindamycin gel with respect to microbiologic activity and clinical efficacy in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1117–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dhawan SS. Comparison of 2 clindamycin 1%-benzoyl peroxide 5% topical gels used once daily in the management of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2009;83:265–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ko HC, Song M, Seo SH, et al. Prospective, open-label, comparative study of clindamycin 1%/benzoyl peroxide 5% gel with adapalene 0.1% gel in Asian acne patients: efficacy and tolerability. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:245–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Webster G. Combination azelaic acid therapy for acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2 Pt 3):S47–S50. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.108318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halder RM, Richards GM. Topical agents used in the management of hyperpigmentation. Skin Therapy Lett. 2004;9:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grimes PE. The safety and efficacy of salicylic acid peels in darker racial-ethnic groups. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:18–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu YI, Stiller MJ. Dapsone and sulfones in dermatology: overview and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:420–434. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barranco VP. Dapsone-other indications. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:513–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1982.tb01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Draelos ZD, Carter E, Maloney JM, et al. Two randomized studies demonstrate the efficacy and safety of dapsone gel, 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:439.e1–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lucky AW, Maloney JM, Roberts J, et al. Dapsone gel 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris: safety and efficacy of long-term (1 year) treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:981–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Genetics Home Reference. [February 10, 2010]. U.S. National Library of Medicine, January 31, 2010. http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition=glucose6phosphatedehydrogenasedeficiency#inheritance.

- 60.Beutler E. G6PD deficiency. Blood. 1994;84:3613–3636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thiboutot DM, Willmer J, Sharata H, et al. Pharmacokinetics of dapsone gel, 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2007;46:697–712. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200746080-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aczone (dapsone) Gel 5% [Package Insert] Mar, 2009. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc.

- 63.Piette WW, Taylor S, Pariser D, et al. Hematologic safety of dapsone gel, 5%, for topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1564–1570. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alexis AF. Clinical considerations on the use of concomitant therapy in the treatment of acne. J Dermatol Treat. 2008;19:199–209. doi: 10.1080/09546630802132635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kircik L. Community-based trial results of combination clindamycin 1%-benzoyl peroxide 5% topical gel plus tretinoin microsphere gel 0.04% or 0.1% or adapalene gel 0.1% in the treament of moderate to severe acne. Cutis. 2007;80(Suppl 1):10–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanghetti E, Abramovits W, Solomon B, et al. Tazarotene versus tazarotene plus clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide in the treament of acne vulgaris: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized parallel-group trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:256–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Del Rosso JQ. Study results of benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% topical gel, adapalene 0.1% gel, and use in combination for acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:616–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fleischer AB, Shalita A, Eichenfield LF, et al. Dapsone gel 5% in combination with adapalene gel 0.1%, benzoyl peroxide gel 4% or moisturizer for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a 12-week, randomized, double-blind study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kelly AP, Sampson DD. Recalcitrant nodulocystic acne in black Americans: treatment with isotretinoin. J Nat Med Assoc. 1987;79:1266–1270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ghaffarpour G, Mazloomi S, Soltani-Arabshahi R, et al. Oral isotretinoin for acne, adjusting treatment according to patient's response. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:878–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Al-Mutairi N, Manchanda Y, Nour-Eldin O, et al. Isotretinoin in acne vulgaris: a prospective analysis of 160 cases from Kuwait. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:369–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ng PP, Goh CL. Treatment outcome of acne vulgaris with oral isotretinoin in 89 patients. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:213–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dhir R, Gehi NP, Agarwal R, et al. Oral isotretinoin is as effective as a combination of oral isotretinoin and topical anti-acne agents in nodulocystic acne. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:187. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.39727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thiboutot DM, Shalita AR, Yamauchi PS, et al. Combination therapy with adapalene gel 0.1% and doxycycline for severe acne vulgaris: A multicenter, investigator-blind, randomized, controlled study. SkinMed. 2005;4:138–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2005.04279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leyden J, Thiboutot DM, Shalita AR, et al. Comparison of tazarotene and minocycline maintenance therapies for acne vulgaris: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group study. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:605–612. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.5.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sturkenboom MC, Meier CR, Jick H, et al. Minocycline and lupus-like syndrome in acne patients. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:493–497. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cleach LL, Bocquet H, Roujeau JC. Reactions and interactions of some commonly used systemic drugs in dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 1998;16:421–429. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maubec E, Wolkenstein P, Loriot MA, et al. Minocycline-induced DRESS: evidence for accumulation of the culprit drug. Dermatology. 2008;216:200–204. doi: 10.1159/000112926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Muller P, Dubreil P, Mahe A, et al. Drug hypersensitivity syndrome in a West-Indian population. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:478–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tsuruta D, Someda Y, Sowa J, et al. Drug hypersensitivity syndrome caused by minocycline. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:131–135. doi: 10.2310/7750.2006.00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Soung J, Cohen J, Phelps R, et al. Case reports: minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation resolved during oral isotretinoin therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:1232–1236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bowen AR, McCalmont TH. The histopathology of subcutaneous minocycline pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:836–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morrow GL, Abbott RL. Minocycline-induced scleral, dental, and dermal pigmentation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:396–397. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hall AH, Bean SM. Minocycline-induced black thyroid. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009 Nov 3; doi: 10.1002/dc.21227. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sant'Ambrogio S, Connelly J, DiMaio D. Minocycline pigmentation of heart valves. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1999;8:329–332. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(99)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hepburn MJ, Dooley DP, Hayda RA. Minocycline-induced black bone disease. Orthopedics. 2005;28:501–502. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20050501-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roberts WE. Chemical peeling in ethnic/dark skin. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:196–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Song JY, Kang HA, Kim MY, et al. Damage and recovery of skin barrier function after glycolic acid chemical peeling and crystal microdermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:390–394. doi: 10.1046/j.1076-0512.2003.30107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Grimes PE. Managment of hyperpigmentation in darker racial ethnic groups. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Grimes PE, Rendon MI, Pellerano J. Superficial chemical peels. In: Grimes PE, editor. Aesthetics and Cosmetic Surgery for Darker Skin Types. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 154–169. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nouri K, Ballard CJ. Laser therapy for acne. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tzung TY, Wu KH, Huang ML. Blue light phototherapy in the treatment of acne. Photodermatol Photoimmunol PhotoMed. 2004;20:266–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2004.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yeung CK, Shek SY, Yu CS, et al. Treatment of inflammatory facial acne with 1,450nm diode laser in type IV to V Asian skin using an optimal combination of laser parameters. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:593–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kawana S, Tachihara R, Kato T, et al. Effect of smooth pulsed light at 400 to 700 and 870 to 1,200 nm for acne vulgaris in Asian skin. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Oh SH, Ryu DJ, Han EC, et al. A comparative study of topical 5-aminolevulinic acid incubation times in photodynamic therapy with intense pulsed light for the treatment of inflammatory acne. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1918–1926. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Noborio R, Nishida E, Morita A. Clinical effect of low-energy double-pass 1450 nm laser treatment for acne in Asians. Photodermatol Photoimmunol PhotoMed. 2009;25:3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2009.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yeung CK, Shek SY, Bjerring P, et al. A comparative study of intense pulsed light alone and in combination with photodynamic therapy for the treatment of facial acne in Asian skin. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39:1–6. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chang SE, Ahn SJ, Rhee DY, et al. Treatment of facial acne papules and pustules in Korean patients using an intense pulsed light device equipped with a 530 to 750nm filter. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:676–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rojanamatin J, Choawawanich P. Treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris with intense pulsed light and short contact of topical 5-aminolevulinic acid: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:991–996. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Charakida A, Seaton ED, Charakida M, et al. Phototherapy in the treatment of acne vulgaris: what is its role? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:211–216. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200405040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Itoh Y, Ninomiya Y, Tajima S, et al. Photodynamic therapy of acne vulgaris with topical ‰-aminolaevulinic acid and incoherent light in Japanese patients. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:575–579. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hong SB, Lee MH. Topical aminolevulinic acid-photodynamic therapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Photodermatol Photoimmunol PhotoMed. 2005;21:322–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2005.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Terrell S, Aires D, Schweiger ES. Treatment of acne vulgaris using blue light photodynamic therapy in an African-American patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:669–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shamban AT, Enokibori M, Narurkar V, et al. Photopneumatic technology for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Battle EF, Jr, Soden CE., Jr The use of lasers in darker skin types. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from a global alliance to improve outcomes in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(1 Suppl):S1–S38. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Goh CK, Tang MB, Briantais P, et al. Adapalene gel 0.1% is better tolerated than tretinoin gel 0.025% among healthy volunteers of various ethnic groups. J Dermatol Treat. 2009;20:282–288. doi: 10.1080/09546630902763164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tu P, Li GQ, Zhu XJ, et al. A comparison of adapalene gel 0.1% vs. tretinoin gel 0.025% in the treatment of acne vulgaris in China. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(Suppl 3):31–36. doi: 10.1046/j.0926-9959.2001.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jacyk AK, Mpofu P. Adapalene gel 0.1% for topical treatment of acne vulgaris in African patients. Cutis. 2001;68:48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kawashima M, Harada S, Loesche C, et al. Adapalene gel 0.1% is effective and safe for Japanese patients with acne vulgaris: a randomized, multicenter, investigator-blinded, controlled study. J Dermatol Sci. 2008;49:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Grimes PE. Using tazarotene to treat acne in patients with skin type V or VI [Poster] J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002 Presented at: the American Academy of Dermatology 60th Annual Meeting; February 22–27, 2002; New Orleans, Lousiana. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Saple DG, Torsekar RG, Pawanarkar V, et al. An open study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of tazarotene gel (0.1%) in acne vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:92–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Garg VK, Sinha S, Sarkar R. Glycolic acid peels versus salicylic-mandelic acid peels in active acne vulgaris and post-acne scarring and hyperpigmentation: a comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kim SW, Moon SE, Kim JA, et al. Glycolic acid versus Jessner's solution: which is better for facial acne patients? Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:270–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang CM, Huang CL, Hu CT, et al. The effect of glycolic acid on the treatment of acne in Asian skin. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1997.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dainichi T, Ueda S, Imayama S, et al. Excellent clinical results with a new preparation for chemical peeling in acne: 30% salicylic acid in polyethylene glycol vehicle. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:891–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hashimoto Y, Suga Y, Mizuno Y, et al. Salicylic acid peels in polyethylene glycol vehicle for the treatment of comedogenic acne in Japanese patients. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:276–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lee HS, Kim IH. Salicylic acid peels for the treatment of acne vulgaris in Asian patients. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1196–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2003.29384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Grimes PE. The safety and efficacy of salicyclic acid peels in darker racial-ethnic groups. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:18–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]