Abstract

The enrichment of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI(4)P) at the trans-Golgi-network (TGN) is instrumental for proper protein and lipid sorting, yet how the restricted distribution of PI(4)P is achieved remains unknown. Here we show that lipid phosphatase SAC1 is crucial for the spatial regulation of Golgi PI(4)P. Ultrastructural analysis revealed that SAC1 is predominantly located at cisternal Golgi membranes but is absent from the TGN, thus confining PI(4)P to the TGN. RNAi-mediated knockdown of SAC1 caused changes in Golgi morphology and mislocalization of Golgi enzymes. Enzymes involved in glycan processing such as mannosidase II (Man-II) and N-acetylglucosamine transferase I (GnT-I) redistributed to aberrant intracellular structures and to the cell surface in SAC1 knockdown cells. SAC1 depletion also induced a unique pattern of Golgi-specific defects in N- and O-linked glycosylation. These results indicate that SAC1 organizes PI(4)P distribution between the Golgi complex and the TGN, which is instrumental for resident enzyme partitioning and Golgi morphology.

Keywords: Golgi apparatus, phosphoinositides, SAC1, glycosylation, secretory pathway

INTRODUCTION

Phosphoinositides are essential for organizing the dynamic stability of the Golgi. PI(4)P appears to be the key player because this phosphoinositide directs both lipid and protein traffic at this organelle (1-7). It is therefore crucial that PI(4)P is not uniformly distributed across the Golgi complex but forms functionally distinct pools that function in concentrating specific lipids and cargo proteins at certain regions. Several PI 4-kinases associate with the Golgi and their enzymatic activities are important for Golgi trafficking (8,1,9). However, how Golgi PI(4)P levels are spatially regulated within the Golgi complex is unknown.

SAC1 is the major lipid 4-phosphatase at the ER and Golgi (10,11). Deletion of SAC1 induces pleiotropic phenotypes in yeast and mammals and causes early embryonic lethality in mice (12,13,11). Both mammalian and yeast SAC1 homologs shuttle between the ER and Golgi dependent on growth conditions (14,15). Depletion of mammalian SAC1 causes Golgi morphology defects (11), yet the basis for this phenotype is not well understood. Here we show that a resident pool of SAC1 is essential for maintaining a polarized distribution of PI(4)P at the Golgi in proliferating cells. The restriction of PI(4)P to the TGN is instrumental for proper steady-state localization of Golgi glycosylation enzymes, correct glycan processing and for Golgi integrity.

RESULTS

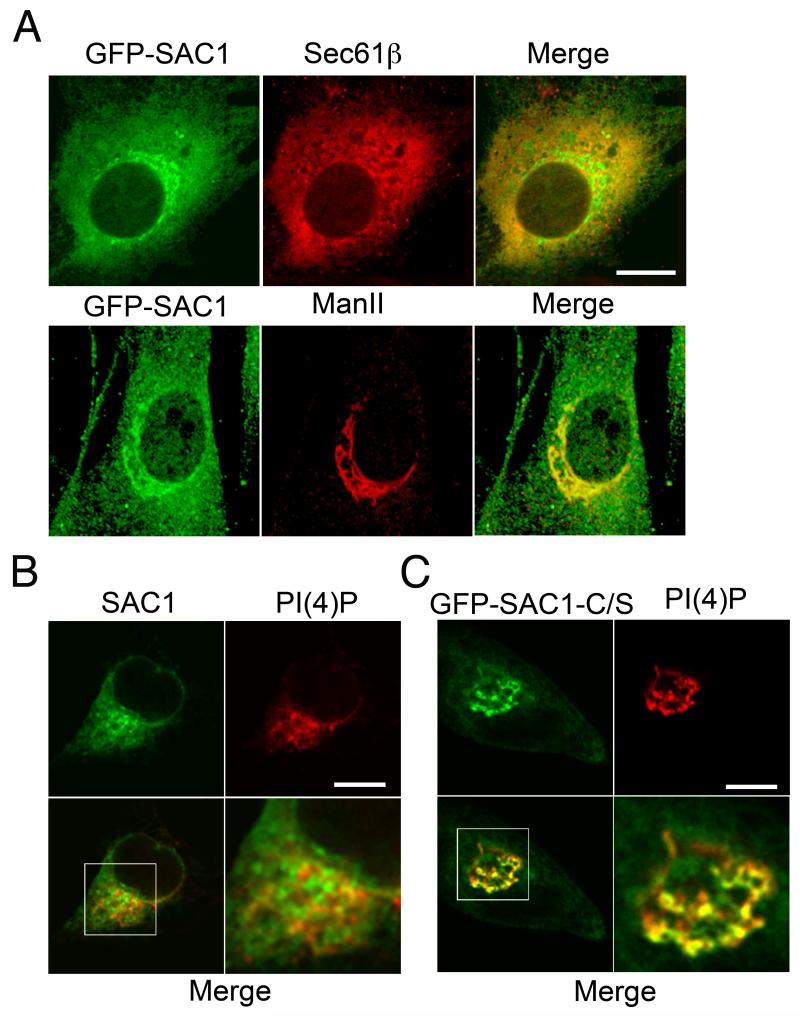

The majority of SAC1 translocates from the Golgi to the ER when quiescent cells are stimulated by growth factors (15). However, a certain proportion of SAC1 remained localized at the Golgi during cell proliferation and colocalized with mannosidase II (Man-II) (Fig 1A). This result was surprising, because PI(4)P is the major substrate of SAC1 and is highly enriched at the Golgi during growth (15). We therefore directly compared the Golgi distribution of these molecules. We found that SAC1 was strongly enriched in Golgi regions that were not stained with a PI(4)P antiserum (Fig 1B). The spatial segregation of PI(4)P and SAC1 was dependent on SAC1 phosphatase activity because the phosphatase-dead SAC1-C/S mutant colocalized with PI(4)P-positive Golgi regions (Fig 1C).

Figure 1. Localization of SAC1 in proliferating cells.

(A) NIH3T3 cells expressing GFP-SAC1 (green) were costained with antibodies against Sec61β (red) or Man-II (red) and examined by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. (B,C) NIH3T3 were stained with antibodies against SAC1 (green) (B), or transfected with a construct for expressing GFP-SAC1-C/S (green) (C), costained with antibodies against PI(4)P (red) and examined by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. The boxed area is enlarged in the adjacent panel. Scale bars, 15 μm.

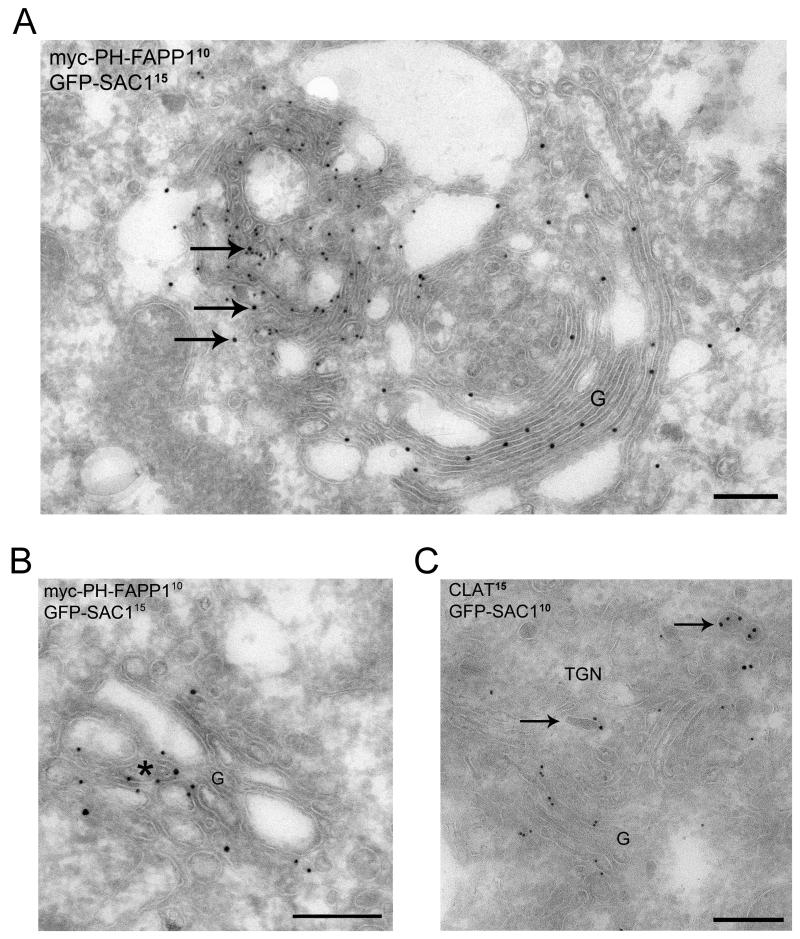

Our results suggested that SAC1 may play a role as spatial regulator of Golgi PI(4)P during cell growth. To further define localization of SAC1 and PI(4)P within the Golgi, we used immunoelectronmicroscopy. To visualize PI(4)P pools we used the probe FAPP1-PH-myc that binds specifically to PI(4)P but not to other phosphoinositides (16, 17). FAPP1-PH-myc, represented by 10 nm gold particles, was largely confined to a membranous network positioned on one side of the Golgi likely representing the TGN, consistent with a previous report (16). In contrast, GFP-SAC1, decorated with 15 nm gold particles, was distributed across cisternal Golgi regions (Fig 2A). We also found rare instances where GFP-SAC1 and FAPP1-PH-myc colocalized at continuous membranes segments indicating that there may be limited coexistence of SAC1 and its lipid substrate within the same membrane (Arrows in Fig 2A and asterisk in Fig 2B). Colocalization with clathrin, which was used as a TGN marker, confirmed that GFP-SAC1 is distributed throughout the Golgi complex, but is virtually absent from TGN membranes (Fig 2C).

Figure 2. SAC1 localizes to the Golgi complex but is absent from TGN membranes.

(A) Hela cells expressing GFP-SAC1 and the PI(4)P probe myc-PH-FAPP1 were double labeled for the myc-epitope (10 nm gold particles) and GFP (15 nm gold particles). The GFP-SAC1 in myc-PH-FAPP1-positive regions is marked with arrows. (B) Limited overlap of myc-PH-FAPP1 (10 nm protein A-gold) and GFP-SAC1 (15 nm protein A-gold) at a continuous membrane segment, indicated by an asterisk. (C) Hela cells expressing GFP-SAC1 were double-labeled for clathrin (15 nm gold particles) and GFP (10 nm gold particles). Labeling patterns were studied in moderately expressing HeLa cells. GFP-SAC1 label was readily detected throughout the Golgi complex, but virtually absent from the TGN membranes. The position of the TGN relative to the Golgi complex is marked by the presence of clathrin (arrows). G = Golgi complex, Scale bars, 200 nm

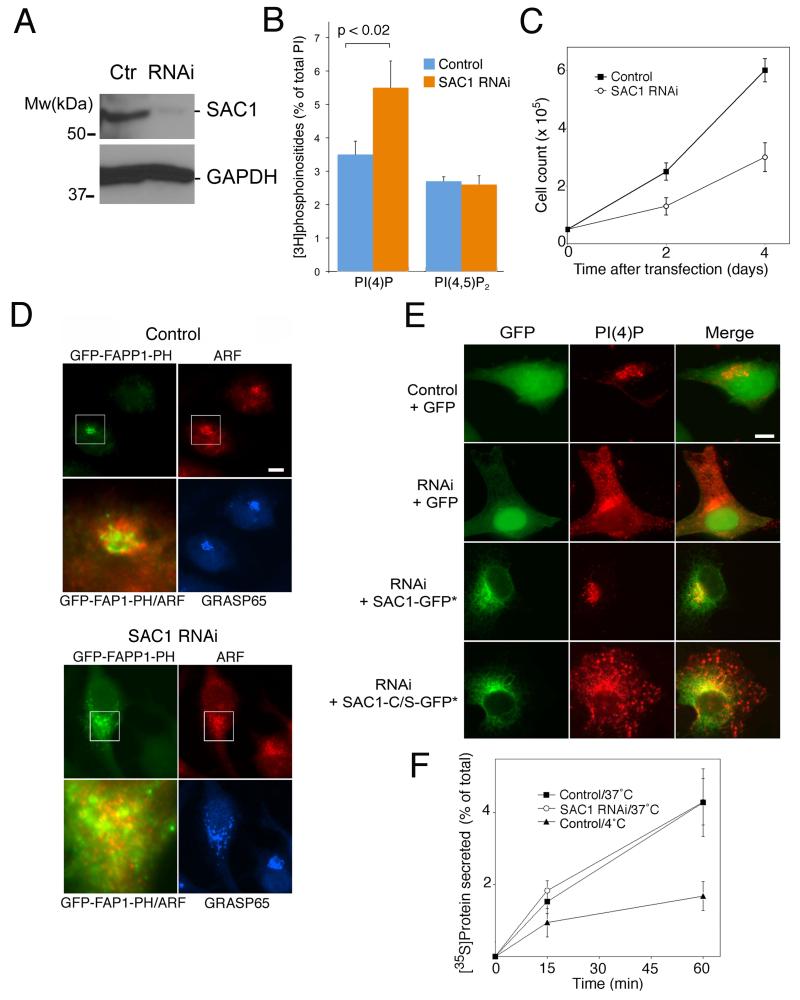

To test whether the spatial distribution of PI(4)P is important for Golgi function, we knocked down SAC1 expression by RNA interference (RNAi) (Fig 3A). Depletion of SAC1 caused a moderate increase in total cellular PI(4)P (Fig 3B) and a robust reduction of cell growth rates (Fig 3C), indicating that PI(4)P homeostasis is important for efficient cell proliferation. To determine whether SAC1 depletion impacts intracellular PI(4)P pools we examined the distribution of this phosphoinositide using a GFP-tagged version of the FAPP1 PH-domain. This domain also binds to activated ARF1 (16), which may influence binding to membranes. In addition, overexpression of FAPP1-PH induces accumulation of ARF1 at the Golgi (16), which may alter Golgi traffic. We therefore, analyzed cells that show only moderate expression levels of GFP-PH-FAPP1. Under these conditions, there was only limited overlap between the PH-FAPP1 probe and ARF1 at the Golgi in control cells (Fig. 3D). When SAC1 was depleted using RNAi, the Golgi became enlarged and fragmented and the GFP-FAPP1-PH was now also present in punctate and peripheral structures (Fig. 3D). GFP-FAPP1-PH remained largely segregated from ARF1-positive structures that were also partially dispersed (Fig. 3D). This result indicates that the GFP-PH-FAPP1 probe recognizes PI(4)P pools that contain little or no ARF1. To further analyze the mislocalization of PI(4)P, we employed a specific antiserum that recognizes the PI(4)P headgroup. Fluorescence microscopy using the PI(4)P antiserum confirmed that SAC1 knockdown was accompanied by mislocalization of PI(4)P to punctate structures and peripheral membranes (Fig 3E). This defect was a direct consequence of SAC1 phosphatase deficiency, because transfection with a RNAi-resistant wild-type SAC1 construct rescued the mislocalization phenotype (Fig 3E). In contrast, a RNAi-resistant SAC1-C/S phosphatase-dead mutant failed to suppress the mislocalization of PI(4)P (Fig. 3E). These findings confirmed that SAC1 enzymatic activity is essential for confining PI(4)P to the appropriate regions within the Golgi. The mislocalization of PI(4)P in SAC1 knockdown cells did not cause alterations in the secretion of [S35]-labeled proteins (Fig. 3F). Similar observations were reported for trafficking of VSV-G in SAC1-depleted cells (11). SAC1-dependent restriction of PI(4)P pools to distinct Golgi regions is therefore not critical for the overall rates of anterograde protein traffic.

Figure 3. SAC1 depletion causes changes in PI(4)P distribution.

(A, B) Hela cells were transfected with siRNAs directed against SAC1 or control RNAs. 72 h after transfection, cells were harvested and analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against SAC1 (A), or labeled with [3H]myo-inositol for 48 h and analyzed for phosphoinositide contents (B). The depicted data are means +/− SD, n=4 (SAC1 knockdown efficiencies in the RNAi samples > 90%). (C) Hela cells were transfected with siRNAs directed against SAC1 or control RNAs. Equal numbers of cells were seeded on plates and cell proliferation was examined at the times indicated. The depicted data are means +/− SD from triplicates derived in three independent sets of experiments. (D) Hela cells were transfected with siRNAs directed against SAC1 or control RNAs. Cells were cotransfected with a vector for expressing GFP-PH-FAPP1 (green). 72 h after transfection cells were stained with antibodies against ARF (red) and GRASP65 (blue) and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. The boxed areas are enlarged in the adjacent panels. Scale bars, 10 μm. (E) Hela cells were transfected with siRNAs directed against SAC1 or control RNAs. Where indicated, cells were either cotransfected with a vector for expressing GFP (green) or constructs for expressing siRNA-resistant versions of GFP-SAC1 (green) or GFP-SAC1-C/S (green). 72 h after transfection cells were stained with antibodies against PI(4)P (red) and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Transfected cells were identified by GFP fluorescence. Scale bars, 10 μm. (F) Hela cells were transfected with siRNAs directed against SAC1 or control RNAs. 72 h after transfection, cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]Met/Cys, incubated at 18°C for 3 h and then shifted to 37°C. At the indicated times, proteins in the culture supernatants and the cell lysates were precipitated, collected on filters and quantified by scintillation counting. As an additional control, the secretion assay was performed at 4°C. The depicted data are means +/− SD from triplicates derived in three independent sets of experiments.

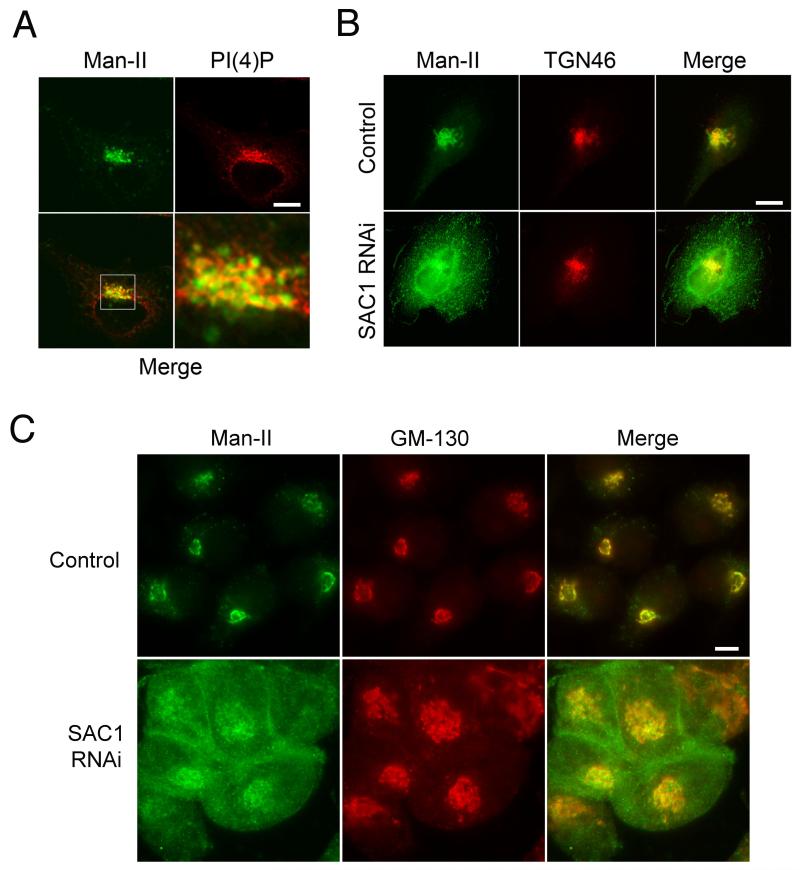

We next examined Golgi morphology and enzyme localization in response to SAC1 RNAi. The medial Golgi glycosidase Man-II colocalized only partially with PI(4)P-positive regions (Fig 4A), consistent with a confined localization of PI(4)P at the TGN. Knockdown of SAC1 expression abolished the Golgi-restricted localization pattern of Man-II (Fig. 4B) and triggered mislocalization to intracellular and peripheral membranes (Fig. 4B). It was reported recently that SAC1 knockdown caused also overall Golgi fragmentation (11). However, when we analyzed the Golgi phenotypes in more detail, we noted that fragmentation occurs only in approximately 50% of SAC1 knockdown cells (Supplementary Fig. S1). A significant proportion of SAC1 knockdown cells displayed mislocalized Man-II and an enlarged Golgi but no apparent disruption (Supplementary Fig. S1). We speculated that deregulation of Golgi PI(4)P may primarily impact proper traffic and distribution of resident enzymes, which may in turn lead to a overall loss of Golgi structural integrity. To investigate this possibility, we compared the localization of Man-II with the distribution of the Golgi matrix protein GM-130 in SAC1-depleted cells. The peripheral mislocalization of Man-II was significantly more severe than the phenotype displayed by GM-130, which remained localized at enlarged Golgi structures (Fig. 4C). The mislocalization of Man-II that was induced by SAC1 depletion could be rescued by expressing RNAi-resistant wild-type GFP-SAC1 but not by RNAi-resistant phosphatase-dead GFP-SAC1-C/S (Supplementary Fig. S1 and S2). We therefore reasoned that restricting PI(4)P to the TGN may be an important mechanism to prevent Golgi enzymes from undergoing anterograde Golgi passage.

Figure 4. Mislocalization of Man-II in SAC1 knockdown cells.

(A) HeLa cells were stained with antibodies against Man-II (green), costained with antibodies against PI(4)P (red) and examined by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. The boxed area is enlarged in the adjacent panel. (B) Hela cells were transfected with siRNAs against SAC1 or control RNAs. 72 h after transfection, cells were stained with antibodies against Man-II (green), costained with antibodies against TGN46 (red) and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. (C) Hela cells were transfected with siRNAs directed against SAC1 or control RNAs containing three point mutations. 72 h after transfection, cells were costained with antibodies against Man-II (green) and GM130 (red) and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm.

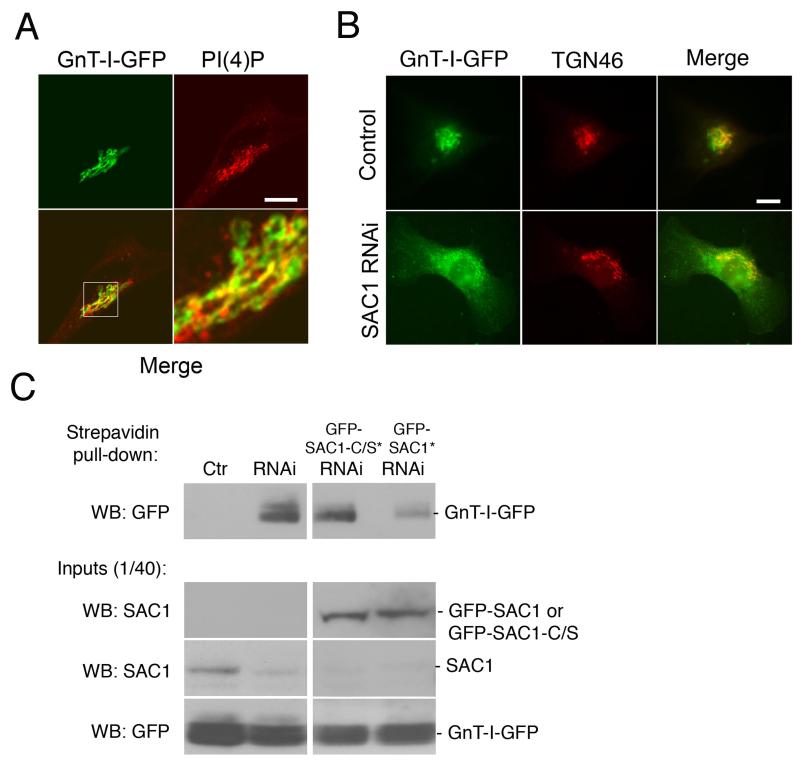

To further test this idea, we examined a GFP-tagged version of N-acetylglucosamine transferase-I (GnT-I-GFP), which is localized at the medial Golgi under normal growth conditions (18). Like Man-II, GnT-I-GFP showed only partial overlap with PI(4)P-enriched Golgi structures in control cells (Fig 5A) and mislocalized to punctate and peripheral structures in SAC1 RNAi cells (Fig 5B). To confirm that depletion of SAC1 triggers anterograde escape of GnT-I-GFP from the Golgi to the cell periphery, we performed cell surface biotinylation experiments. No surface biotinylated GnT-I-GFP could be detected in control cells (Fig. 5C). In contrast, a substantial amount of biotinylated GnT-I-GFP was recovered from SAC1 knockdown cells (Fig 5C). Expression of a RNAi-resistant construct for expressing wild-type GFP-SAC1 strongly reduced the amount of biotinylated GnT-I-GFP in SAC1 RNAi cells, whereas a RNAi-resistant phosphatase-dead GFP-SAC1-C/S was unable to rescue surface biotinylation of GnT-I-GFP (Fig 5C).

Figure 5. SAC1 knockdown triggers mislocalization of medial Golgi marker GnT-I-GFP.

(A) HeLa cells were transfected with a plasmid for expressing GnT-I-GFP (green), costained with antibodies against PI(4)P (red) and examined by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. The boxed area is enlarged in the adjacent panel. Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) Hela cells were cotransfected with a plasmid for expressing GnT-I-GFP (green) and siRNAs against SAC1 or control RNAs. 72 h after transfection, cells were costained with antibodies against TGN46 (red) and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm. (C) Biotinylation of cell surface proteins. Hela cells were transfected with plasmids for expressing GnT-I-GFP and siRNAs against SAC1 or control RNAs. Where indicated cells were cotransfected with plasmids for expressing siRNA-resistant versions of GFP-SAC1 (green) or GFP-SAC1-C/S (green). 72 h after transfection, cell surface proteins were biotinylated, isolated from detergent extracts by streptavidin agarose and separated by SDS-PAGE. Biotinylated GnT-I-GFP was identified by immunoblotting using specific polyclonal antibodies against GFP.

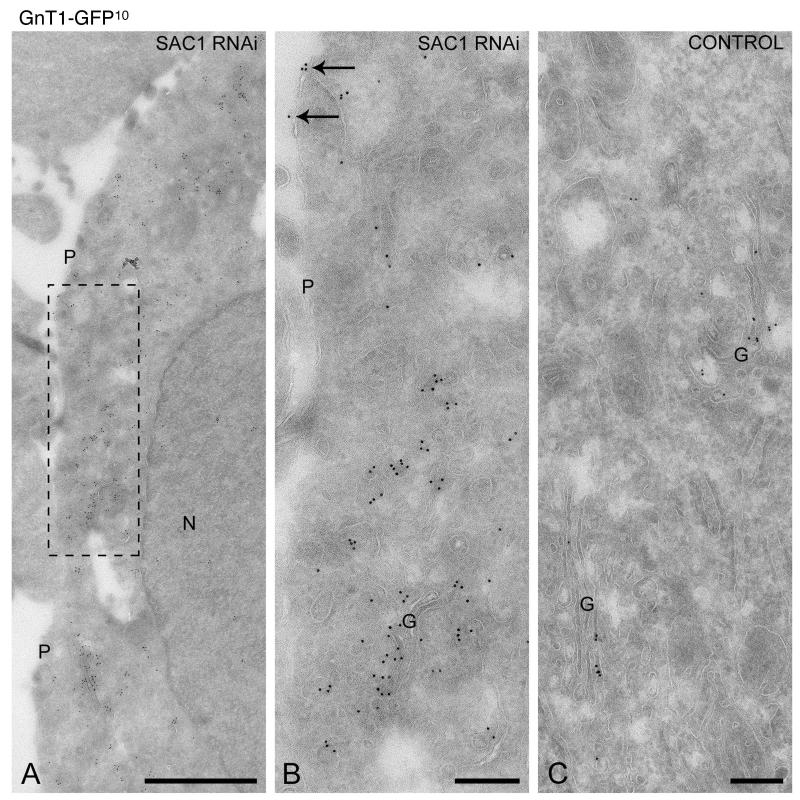

To examine the Golgi phenotype and GnT-1-GFP mislocalization in SAC1 RNAi cells in more detail, we performed immunoelectronmicroscopy on ultrathin cryosections. Depletion of SAC1 caused fragmentation of Golgi structures and redistribution of GnT-I-GFP to small vesicles that were dispersed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig 6A, B). A portion of GnT-I-GFP was also localized at the plasma membrane in SAC1 RNAi cells (Fig 6A and 6B, arrows), thus confirming the biotinylation analysis. In control cells, GnT-I-GFP remained confined to the Golgi complex (Fig 6C).

Figure 6. SAC1 depletion causes dispersion of GnT-I-GFP.

Hela cells expressing GnT-I-GFP were transduced with siRNAs against SAC1 (A,B) or control RNAs (C) after which ultrathin cryosections were prepared that were immunogold-labeled for GFP to localize GnT-I-GFP (10 nm gold particles). (A,B) The boxed area in A is enlarged in B. SAC1 depletion caused a redistribution of GnT-I-GFP to numerous small-sized vesicles that were dispersed throughout the cytoplasm. In addition, some labeling was found at the plasma membrane (arrows in B). (C) In control cells GnT-I-GFP shows a restricted localization to the Golgi complex. G = Golgi complex, N = nucleus, P = plasma membrane Bars (A), 1 m; (B,C), 200 nm

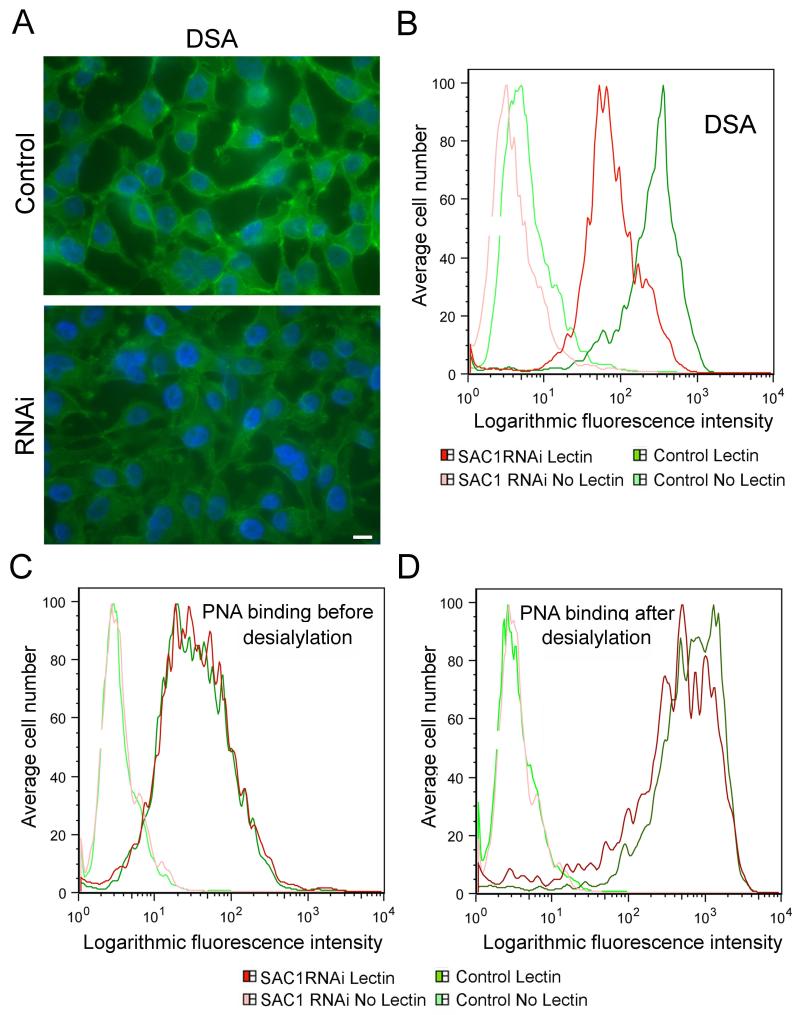

Mislocalization of Golgi enzymes may alter protein glycosylation patterns. We therefore used lectin binding and metabolic labeling to examine the effects of SAC1 knockdown on glycan processing. Metabolically labeled N-glycans in SAC1 knockdown and control cells appeared identical based on ion-exchange and Concanavalin A affinity chromatography (data not shown). To examine glycosylation patterns more specifically, we quantitated surface binding of a set of lectins with diagnostic binding specificities (Supplementary Fig S3A). This data showed normal amounts of sialylation and N-glycan branching in SAC1 knockdown cells and revealed normal complex, hybrid and high mannose structures. Surface binding of ConA, which primarily binds to the outer trimannosyl regions of high mannose was unchanged in SAC1 knockdown cells (Supplementary Fig S3A) indicating that the significant mislocalization of Man-II did not produce a specific glycan processing defect. However, SAC1 knockdown cells had significantly decreased surface binding of Datura stramonium lectin (DSA) (Fig 7A, B). Surface binding of peanut agglutinin (PNA) also decreased but only after sialidase digestion (Fig 7C, D). Binding of each lectin was decreased 1.5 to 3-fold in SAC1 knockdown cells compared to controls. This result indicates that SAC1 depletion selectively altered specific aspects of N- and O-glycosylation. Changes were limited to decreased addition of poly-N-acetyllactosamine repeats (Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3) on complex, multi-antennery N-glycans (probed by DSA, Fig 7A, B) and reduced levels of Galβ1-3GalNAcα-O-Ser/Thr (probed by PNA, Fig 7C, D). There was no difference in PNA staining without prior sialidase digestion (Compare Fig 7C and D), which indicates that the simple Core 1 glycan was fully sialylated. Poly-N-acetyllactosamine repeats are synthesized through alternate addition of GlcNAc and galactose by β-1,3 N-acetyl glucosaminyl transferase and β-1,4 galactosyl transferase, respectively. Addition of lactosamine repeats depends on the residence time of glycans in Golgi (19,20) and the interaction between glycan processing enzymes with their substrates may be altered in SAC1 knockdown cells.

Figure 7. SAC1 knockdown cells display altered N-linked glycan processing.

(A) Control and SAC1 knockdown cells were fixed and incubated with biotinylated DSA, stained with FITC-Avidin and examined for cell surface staining. Scale bar, 15 μm. (B-D). FACS analysis of cell surface binding of lectins. Cells were incubated with or without the biotinylated lectins followed by incubation with FITC conjugated avidin. Green profiles indicate control cells, (light green, without lectin; dark green, with lectin). Red profiles indicate SAC1 knockdown cells, (light red, without lectin; dark red, with lectin). Depicted are the results for DSA-binding (B) and PNA-binding before (C) or after desialylation. Lectin specificities: DSA, linear, unbranched poly-N-acetyl-lactosamine [Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3]n repeats; PNA, Core 1 O-glycan,Galβ1-3GalNAcα.

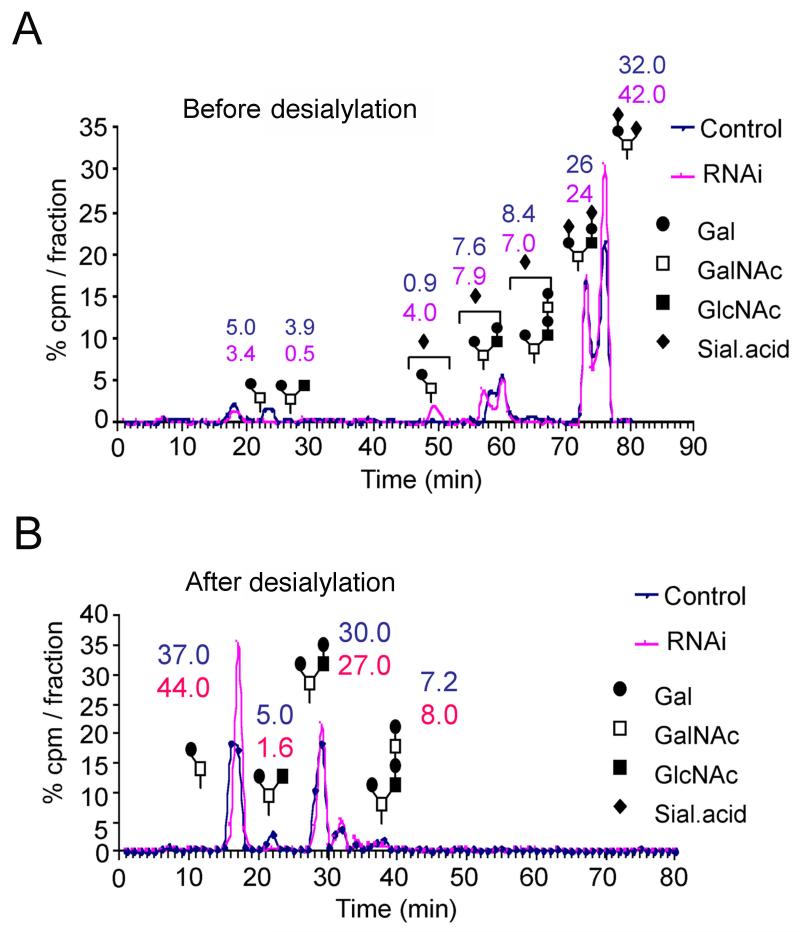

To investigate the effects of SAC1 knockdown on O-glycan synthesis, cells were labeled with [6-3H]galactose in the presence of GalNAc-α-phenyl (GAP), an artificial acceptor that monitors biosynthetic glycosylation capacity (21). SAC1 knockdown cells synthesized approximately 15-30% less labeled GAP than control cells (Supplemental Fig. 3B), consistent with decreased PNA binding. HPLC analysis of labeled GAP products showed that SAC1 knockdown cells had an increased proportion of Core 1 glycans, especially di-sialo, Core 1 glycan, Siaα2,3Galβ1-3[Siaα2-6]GalNAcα-O (Fig. 8A). Desialylation confirmed this alteration (Fig. 8B). Because addition of α2,6 sialic acid to Core 1 glycans blocks Core 2 GlcNAc transferase, these results suggested that SAC1 knockdown allows α2,6 sialyltransferase to more effectively compete against Core 2 transferase. These reactions are mutually exclusive and occur in the medial Golgi.

Figure 8. SAC1 knockdown cells show changes in O-linked glycans.

(A, B) Control and SAC1 knockdown cells were labeled with 3H-galactose in the presence of GAP. 3H-GAP products were then purified from the medium and analyzed using HPLC before (A) or after desialylation (B). The numbers indicate the percentage of total labeled glycans.

DISCUSSION

We have recently reported that the lipid phosphatase SAC1 is required for rapid downregulation of Golgi PI(4)P and secretion during starvation and quiescence (15). The present study shows that SAC1 is also required for spatial regulation of Golgi PI(4)P during proliferation. The SAC1-dependent mechanism that controls spatial distribution of PI(4)P appears to be instrumental for proper steady state positioning of Golgi glycosylation enzymes. Recent evidence indicates that Golgi function requires the organization of functionally distinct domains enriched in certain proteins and lipids (3,22). Our results suggest that spatial regulation of PI(4)P is a key element in the mechanism underlying the organization of the Golgi. It is established that the cellular distribution of different phosphoinositide species is strongly compartmentalized, yet the mechanism by which this is achieved remains unclear (23). Our data now shows that SAC1 is essential for controlling the distribution of PI(4)P between Golgi compartments. PI(4)P, in synergy with the small GTPase ARF, may define TGN regions, active in lipid sorting and secretory cargo packaging and trafficking (3,16). SAC1 is a crucial component in this mechanism because its enzymatic activity is directly linked to establishing this TGN-restricted localization of PI(4)P.

Depletion of SAC1 caused significant morphological changes of the Golgi. Proper distribution of PI(4)P at the Golgi may therefore be required for the structural integrity of this organelle. However, SAC1 might have multiple functions required for Golgi structure and function. A significant proportion of SAC1 resides at the ER in proliferating cells (15) and it remains a possibility that the ER-localized pool of SAC1 plays a specific role in Golgi organization. The recent finding that a SAC1 mutant defective in COP-I-mediated retrieval to the ER cannot rescue the Golgi defects in SAC1 knockdown cells gives some weight to this idea (11).

Golgi function exhibited surprising resilience toward disturbances in PI(4)P distributions. Neither overall trafficking rates nor general N-glycan processing and branching were significantly affected by a SAC1 knockdown-induced mislocalization of PI(4)P pools. The fact that the significant mislocalization of Man-II did not produce increased levels of high-mannose structures indicates that the precise localization of Man-II at the Golgi may not be critical for proper glycan processing. It is also possible that residual levels of Man-II at the Golgi complex are sufficient for proper mannose trimming. In contrast, the fidelity of several other glycosylation reactions was specifically impaired. This was particularly evident when competing mutually exclusive glycosylation reactions, such as addition of Core 2 GlcNAc versus incorporation of α-2,6 sialic acid, were examined.

How could changes in Golgi PI(4)P distribution lead to mislocalization of glycosylation enzymes? A fine balance between anterograde and retrograde transport appears to be essential for the spatial and temporal regulation of glycosyl transferases (24,25). It is therefore possible that SAC1 knockdown and mislocalization of PI(4)P causes enhanced recruitment of Golgi enzymes into PI(4)P-dependent anterograde trafficking structures, which are normally restricted to the TGN. The exclusion of PI(4)P from Golgi cisternae may therefore be instrumental for preventing anterograde passage of Golgi enzymes to the cell periphery. Alternatively, COP-I mediated retrograde transport of Golgi enzymes may be impaired in SAC1-depleted cells, which could also lead to the observed peripheral accumulation. The residence time of glycosyl transferases with their substrates is a known factor influencing glycosylation (19,20). Alterations in Golgi enzyme trafficking may therefore weaken their ability to interact productively with protein substrates, which may be the basis for the observed glycosylation phenotype. Recent data showed that proper trafficking of Golgi enzymes is of significant relevance for human health. In several human congenital disorders of glycosylation, mutations in COG subunits or in a vacuolar H+-ATPase impair normal retrograde trafficking of Golgi glycosylation enzymes and cause severe disorders characterized by alterations in glycosylation patterns (26-28). A disturbance of the spatial distribution of PI(4)P gradients within the Golgi is therefore likely to cause human pathology.

METHODS

Antibodies and reagents

All chemical reagents were of analytical grade or higher and purchase from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA), Fischer Scientific (Hampton, NH, USA) and VWR (West Chester, PA, USA) unless otherwise specified. Polyclonal antibody to human SAC1 (#69) was raised in rabbit using peptide CNGKDFVDAPRLVQKEKID, (hSAC1, amino acids 569-587) conjugated to KLH. Antibodies from commercial sources are as follow: mouse monoclonal anti-PI(4)P (Echelon, Salt Lake City, UT, USA), sheep anti-TGN46 (Serotec, Raleigh, NC, USA), rabbit anti-Mannosidase II (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA), rabbit anti-Mannosidase II (University of Georgia, Complex Carbohydrate Research Center and Department of Molecular Biology, USA), mouse anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, GAPDH (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), goat anti-GFP (Rockland, USA), rabbit anti-biotin (Rockland, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-ARF1 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA). The anti-p24 serum was provided by F. Wieland (BZH, University of Heidelberg, Germany), anti-Sec61β antibodies are a gift from B. Dobberstein (ZMBH, University of Heidelberg, Germany). Secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson Immunoresearch Labs, Inc. and Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Biotinylated lectins and FITC conjugated avidin were purchased from EY laboratories Inc. (San Mateo, CA, USA). Protein A conjugated to 10 or 15 nm gold particles was manufactured by the Cell Microscopy Centre, Department of Cell Biology, University Medical Centre Utrecht, NL.

Cell Culture and RNA interference

Cells were grown in DMEM (Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. 24 h before transfection, the cells were seeded either on culture plates or on coverslips. Cells were transfected with 0.2 μM siRNA directed against SAC1 (5′-GGCGUGUUCCGAAGCAAUU-3′) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Control siRNAs were generated by changing three nucleotides in the siRNA sequence (5′-AGCGUGGUCCGAAGCCAUU-3′). To express RNAi-resistant SAC1 proteins, five silent mutations were introduced into the coding region of recombinant SAC1 that is targeted by siRNAs. Transfected cells were assayed 72 h post-transfection.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Immunofluoresce was performed as described in (15). In brief, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, incubated with 0.1 M glycine and permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X-100. Cells were incubated with corresponding primary and secondary antibodies diluted in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). For PI(4)P staining, cells were fixed in 2% formaldehyde/PBS for 10 min and then permeabilized using 10 μg/ml digitonin in 100 mM glycine, after 3-5 washes with PBS. Cells were then incubated with 1% BSA/PBS for 1 h followed by an overnight incubation with PI(4)P antibodies diluted in 1% BSA, PBS at 4°C. Cells were examined using a Nikon Eclipse E800-microscope equipped with a CoolSNAP HQ-Camera from Photometrics (Tuscan, AZ, USA). Confocal micrographs were taken by a Olympus BX51-Microscope using a Olympus PlanApo 60 x Oil immersion objective. Images were analyzed using Metamorph Image software (for fluorescence micrographs) and Image J (Confocal micrographs).

Electron microscopy

HeLa cells were grown in 100 mm dishes to 75-90% confluency prior to transfections. Transfections with constructs for expressing FAPP1-PH-myc and GFP-SAC1 were performed using Lipofectamine/Plus reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The transfected HeLa cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. After washing with 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, the fixed cells were stored in 1% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 at 4°C. Ultrathin cryosectioning and immunogold labeling were performed as previously described (29).

Lipid analysis

Cells were labeled with 10 μCi/ml [3H]-myo-inositol (Perkin-Elmer) in inositol-free media (ICN) for 48 h. After washing with ice-cold PBS, 1 ml of ice-cold 0.5 M perchloric acid was added to cells and the cells were scrapped into an eppendorf tube and washed once with ice-cold 0.5 M perchloric acid. Lipids were solubilized in 750 μl of methanol:chloroform:HCl (80:40:1, v/v/v). After incubation at room temperature for 30 min, 250 μl of chloroform and 450 μl of 0.1 M HCl was added followed by centrifugation for 1 min to separate the phases. The organic lower phase was removed and the aqueous upper phase was neutralized with 50 μl of NH4OH and reextracted twice as described above. The pooled organic phases were washed with 5 volumes of 2 M KCl and dried in a speedvac.

The dried lipid pellet was deacylated using methlyamine reagent as described previously (30). HPLC analysis of glycerophosphoinositols was carried out on a Jasco HPLC system equipped with an LB 508 Radioflow detector (Berthold, Bad Wildbach, Germany). The following gradient for elution of the HPLC column was used: buffer A, water; buffer B, 1M (NH4)4HPO4 (pH3.8). The gradient was run at 0% buffer B for 10 min and increased to 25% buffer B over 60 min and then to 100% buffer B over 20 min. The flow rate was 1ml/min.

Secretion assay

Cells were starved in Met/Cys free media for 30 min and then pulse-labeled with 30 μCi of [35S]-Met/Cys (S35-EXPRESS from Amersham) per well in a 6-well plate for 10 min at 37°C. Incorporation of radioactivity into proteins was stopped by placing the cultures on ice and by 3 washes with ice-cold full DMEM (with Met/Cys + serum). Subsequently the cells were transfered to 18°C for 3 h, washed with 5% BSA/PBS and then shifted to 37°C. To determine the kinetics of secretion, culture supernatants were collected at different times. [35S]-labeled proteins were precipitated by 10% TCA, collected on filters (GF/C filters, Whatman) and quantified by scintillation counting. To determine total incorporation of [35S]-Met/Cys into cellular proteins, the cells were lysed in RIPA buffer for 10 min. Supernatants were collected, TCA treated and processed as above. For controls, cells remained incubated on ice before supernatants were collected and cells were lysed and analyzed.

Cell surface biotinylation

Cells were washed twice with PBS and then incubated with 0.3-0.5 mg/ml EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce) in PBS for 30 min on ice. For quenching, 100 mM glycine in PBS was added for 5 min. Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 1 mM PMSF. Cells were scrapped into Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 10 min. The supernatants were incubated with 50 μl of 50% Streptavidin agarose beads overnight at 4°C. The beads were washed twice with cold PBS and bound proteins were solubilized in Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide).

Glycosylation analysis

For analysis of O-glycosides, cells were grown to approximately 70% confluency in DMEM containing 10% BCS, washed in PBS, and incubated in serum free media containing 2.0 mM glucose with 20 μCi/ml [6-3H]Galactose and 0.25 mM GalNAc-α-phenyl (GAP). Cells were incubated at 37°C overnight and collected for further analysis. 3H-Galactose-labeled GAP products were purified using a C18 cartridge and analyzed by amine adsorption HPLC using a Microsorb-MV (NH2) column, 4.5 × 250 mm (Varian Inc.,CA, USA) using an acetonitrile and ammonium formate, pH 6.0 gradient as described by Kim et al. (21) Desialylation was performed by mild acid hydrolysis in 10 mM HCl for 10 min at 100°C.

To detect surface bound lectins, the cells were grown on glass coverslips and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Biotinylated DSA (2.5 μg/ml) was diluted in PBS and added at room temperature for 1 h. The cells were subsequently washed and incubated with FITC bound avidin for 30 min. The coverslips were mounted on glass slides using Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI and visualized using a fluorescence microscope.

For FACS analysis of lectin binding, control and SAC1 knockdown cells were grown to 70% confluency. Single cell suspensions were made in 5 mM EDTA in PBS. Subsequently, all the steps were performed on ice. After blocking with 1% BSA/PBS, the cells were incubated with or without 1 μg biotinylated lectin in 100 μl volume for 1 h. The cells were washed and incubated with 1 μg of FITC conjugated avidin in 100 μl volume for 30 minutes. Finally, the cells were washed and resuspended in PBS containing propidium iodide and analyzed.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the NIH, R01GM084088 to P.M. and R01DK55615 to H.H.F., and by a PhD scholarship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to F.Y.C. We are also indebted to Graham Warren, Scott Emr, Felix Wieland and Bernhard Dobberstein for providing plasmids and antibodies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang YJ, Wang J, Sun HQ, Martinez M, Sun YX, Macia E, Kirchhausen T, Albanesi JP, Roth MG, Yin HL. Phosphatidylinositol 4 phosphate regulates targeting of clathrin adaptor AP-1 complexes to the Golgi. Cell. 2003;114:299–310. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00603-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanada K, Kumagai K, Yasuda S, Miura Y, Kawano M, Fukasawa M, Nishijima M. Molecular machinery for non-vesicular trafficking of ceramide. Nature. 2003;426:803–809. doi: 10.1038/nature02188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Angelo G, Polishchuk E, Di Tullio G, Santoro M, Di Campli A, Godi A, West G, Bielawski J, Chuang CC, van der Spoel AC, Platt FM, Hannun YA, Polishchuk R, Mattjus P, De Matteis MA. Glycosphingolipid synthesis requires FAPP2 transfer of glucosylceramide. Nature. 2007;449:62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature06097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halter D, Neumann S, van Dijk SM, Wolthoorn J, de Maziere AM, Vieira OV, Mattjus P, Klumperman J, van Meer G, Sprong H. Pre- and post-Golgi translocation of glucosylceramide in glycosphingolipid synthesis. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:101–115. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, Sun HQ, Macia E, Kirchhausen T, Watson H, Bonifacino JS, Yin HL. PI4P promotes the recruitment of the GGA adaptor proteins to the trans-Golgi network and regulates their recognition of the ubiquitin sorting signal. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2646–2655. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peretti D, Dahan N, Shimoni E, Hirschberg K, Lev S. Coordinated lipid transfer between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi complex requires the VAP proteins and is essential for Golgi-mediated transport. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3871–3884. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngo M, Ridgway ND. Oxysterol binding protein-related protein 9 (ORP9) is a cholesterol transfer protein that regulates Golgi structure and function. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1388–1399. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godi A, Pertile P, Meyers R, Marra P, Di Tullio G, Iurisci C, Luini A, Corda D, De Matteis MA. ARF mediates recruitment of PtdIns-4-OH kinase-beta and stimulates synthesis of PtdIns(4,5)P2 on the Golgi complex. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:280–287. doi: 10.1038/12993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weixel KM, Blumental-Perry A, Watkins SC, Aridor M, Weisz OA. Distinct Golgi populations of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate regulated by phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10501–10508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohde HM, Cheong FY, Konrad G, Paiha K, Mayinger P, Boehmelt G. The human phosphatidylinositol phosphatase SAC1 interacts with the coatomer I complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52689–52699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Boukhelifa M, Tribble E, Morin-Kensicki E, Uetrecht A, Bear JE, Bankaitis VA. The Sac1 phosphoinositide phosphatase regulates Golgi membrane morphology and mitotic spindle organization in mammals. Mol Biol Cell. 2008 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitters EA, Cleves AE, McGee TP, Skinner HB, Bankaitis VA. Sac1p is an integral membrane protein that influences the cellular requirement for phospholipid transfer protein function and inositol in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:79–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kochendorfer KU, Then AR, Kearns BG, Bankaitis VA, Mayinger P. Sac1p plays a crucial role in microsomal ATP transport, which is distinct from its function in Golgi phospholipid metabolism. EMBO J. 1999;18:1506–1515. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faulhammer F, Konrad G, Brankatschk B, Tahirovic S, Knodler A, Mayinger P. Cell growth-dependent coordination of lipid signaling and glycosylation is mediated by interactions between Sac1p and Dpm1p. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:185–191. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blagoveshchenskaya A, Cheong FY, Rohde HM, Glover G, Knodler A, Nicolson T, Boehmelt G, Mayinger P. Integration of Golgi trafficking and growth factor signaling by the lipid phosphatase Sac1. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:803–812. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godi A, Campli AD, Konstantakopoulos A, Tullio GD, Alessi DR, Kular GS, Daniele T, Marra P, Lucocq JM, Matteis MA. FAPPs control Golgi-to-cell-surface membrane traffic by binding to ARF and PtdIns(4)P. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:393–404. doi: 10.1038/ncb1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knodler A, Mayinger P. Analysis of phosphoinositide-binding proteins using liposomes as an affinity matrix. Biotechniques. 2005;38:858, 860, 862. doi: 10.2144/05386BM02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsson T, Rabouille C, Hui N, Watson R, Warren G. The role of the membrane-spanning domain and stalk region of n-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-I in retention, kin recognition and structural maintenance of the Golgi-apparatus in HeLa cells. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1975–1989. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.7.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang WC, Lee N, Aoki D, Fukuda MN, Fukuda M. The poly-n-acetyllactosamines attached to lysosomal membrane glycoproteins are increased by the prolonged association with the Golgi complex. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23185–23190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nabi IR, Dennis JW. The extent of polylactosamine glycosylation of MDCK Lamp-2 is determined by its Golgi residence time. Glycobiology. 1998;8:947–953. doi: 10.1093/glycob/8.9.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S, Miura Y, Etchison JR, Freeze HH. Intact Golgi synthesize complex branched o-linked chains on glycoside primers: Evidence for the functional continuity of seven glycosyltransferases and three sugar nucleotide transporters. Glycoconj J. 2001;18:623–633. doi: 10.1023/a:1020691619908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klemm RW, Ejsing CS, Surma MA, Kaiser HJ, Gerl MJ, Sampaio JL, de Robillard Q, Ferguson C, Proszynski TJ, Shevchenko A, Simons K. Segregation of sphingolipids and sterols during formation of secretory vesicles at the trans-Golgi network. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:601–612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200901145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varnai P, Balla T. Live cell imaging of phosphoinositide dynamics with fluorescent protein domains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:957–967. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miles S, McManus H, Forsten KE, Storrie B. Evidence that the entire Golgi apparatus cycles in interphase hela cells: Sensitivity of Golgi matrix proteins to an ER exit block. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:543–555. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward TH, Polishchuk RS, Caplan S, Hirschberg K, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Maintenance of Golgi structure and function depends on the integrity of ER export. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:557–570. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu X, Steet RA, Bohorov O, Bakker J, Newell J, Krieger M, Spaapen L, Kornfeld S, Freeze HH. Mutation of the COG complex subunit gene COG7 causes a lethal congenital disorder. Nat Med. 2004;10:518–523. doi: 10.1038/nm1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kranz C, Ng BG, Sun L, Sharma V, Eklund EA, Miura Y, Ungar D, Lupashin V, Winkel RD, Cipollo JF, Costello CE, Loh E, Hong W, Freeze HH. COG8 deficiency causes new congenital disorder of glycosylation type IIh. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:731–741. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kornak U, Reynders E, Dimopoulou A, van Reeuwijk J, Fischer B, Rajab A, Budde B, Nurnberg P, Foulquier F, Lefeber D, Urban Z, Gruenewald S, Annaert W, Brunner HG, van Bokhoven H, Wevers R, Morava E, Matthijs G, Van Maldergem L, Mundlos S. Impaired glycosylation and cutis laxa caused by mutations in the vesicular H+-ATPase subunit ATP6V0A2. Nat Genet. 2008;40:32–34. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slot JW, Geuze HJ. Cryosectioning and immunolabeling. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2480–2491. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serunian LA, Auger KR, Cantley LC. Identification and quantification of polyphosphoinositides produced in response to platelet-derived growth factor stimulation. Methods Enzymol. 1991;198:78–87. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)98010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.