Abstract

Background

Inadequate follow-up of abnormal fecal occult blood test (FOBT) results occurs in several types of practice settings. Our institution implemented multifaceted quality improvement (QI) activities in 2004–2005 to improve follow-up of FOBT positive results. Activities addressed pre-colonoscopy referral processes and system-level factors such as electronic communication and provider education and feedback. We evaluated their effects on timeliness and appropriateness of positive FOBT follow-up and identified factors that affect colonoscopy performance.

Methods

Retrospective electronic medical record (EMR) review was used to determine outcomes pre- and post-QI activities in a multi-specialty ambulatory clinic of a tertiary care Veterans Affairs facility and its affiliated satellite clinics. From 1869 FOBT positive cases, 800 were randomly selected from time periods before and after QI activities. Two reviewers used a pretested standardized data collection form to determine whether colonoscopy was appropriate or indicated based on pre-determined criteria and if so, the timeliness of colonoscopy referral and performance pre- and post-QI activities.

Results

In cases where a colonoscopy was indicated, the proportion of patients who received a timely colonoscopy referral and performance were significantly higher post implementation (60.5% vs. 31.7%, p<0.0001 and 11.4% vs. 3.4%, p =0.0005 respectively). A significant decrease also resulted in median times to referral and performance (6 vs. 19 days p<0.0001 and 96.5 vs. 190 days p<0.0001 respectively) and in the proportion of positive FOBT test results that had received no follow-up by the time of chart review (24.3%vs. 35.9%; p=0.0045). Significant predictors of absence of the performance of an indicated colonoscopy included performance of a non-colonoscopy procedure such as barium enema or flexible sigmoidoscopy (OR=16.9; 95% CI 1.9–145.1), patient non-adherence (OR=33.9; 95% CI 17.3–66.6), not providing an appropriate provisional diagnosis on the consultation (OR= 17.9; 95% CI 11.3–28.1) and gastroenterology service not rescheduling colonoscopies after an initial cancellation (OR= 11.0; 95% CI 5.1–23.7)

Conclusions

Multifaceted QI activities improved rates of timely colonoscopy referral and performance in an EMR system. However, colonoscopy was not indicated in over one third of patients with positive FOBTs, raising concerns about current screening practices and the appropriate denominator used for performance measurement standards related to colon cancer screening.

INTRODUCTION

Many studies that address follow-up of abnormal cancer screening examinations reveal that fewer than 75% of patients receive diagnostic care subsequent to the initial screening.1–5 Because colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States, benefits of population-based screening programs may be considerably compromised by inadequate follow-up of abnormal screens.6–9 For instance, high-sensitivity fecal occult blood test (FOBT) using the Hemoccult SENSA method is the dominant mode of screening for CRC in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA),10 but more than 40% of veterans with a positive FOBT may not be receiving timely follow-up with colonoscopies.11 Inadequate follow-up of abnormal FOBT has been also documented in other types of practice settings.1,2,6,12–15

Inadequate FOBT follow-up may be related to patient-level, provider-level, or system-level factors.1,2,16–18 In some health care systems including the VA, significant barriers to adequate follow-up may exist, including limited endoscopic capacity (endoscopists, support staff rooms and equipment) and limited resources for obtaining timely follow-up diagnostic procedures.16 Delays may also arise from problems in having patients complete the scheduled colonoscopy procedure (post-colonoscopy referral delays).1,19 However, an important and largely preventable determinant of system-level delay is a problem in communication of the abnormal FOBT test result from the laboratory to providers who ordered them.20,20–22 This may be due to lack of transmission of the test result or from inaction on the results by ordering providers (pre-colonoscopy referral delays).2,14,18,23

Given the multifactorial origin of preventable delays, the primary care and gastroenterology sections in our VA implemented quality improvement (QI) activities in 2004–2005 to improve follow-up care for FOBT positive results. These activities addressed many pre-colonoscopy referral processes and targeted system-level factors such as communication24 and provider education and feedback. They were specifically chosen because of their feasibility and relative ease of implementation. Some of the QI activities were promoted by a VA Colorectal Cancer Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (CRC-QUERI) with a mission to “promote the implementation of CRC-related research discoveries and evidence-based care” among veterans. This initiative--the Colorectal Cancer Care Collaborative (C4)--emphasizes the need to reduce the time from positive screening test to diagnostic test and was fostered by partnerships between the CRC-QUERI, VA Office of Quality and Performance, and VA Advanced Clinic Access (ACA).

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the effects of implementation of these QI activities on the timeliness and appropriateness of follow-up for positive FOBT results with a colonoscopy and to identify factors that affect colonoscopy performance.

METHODS

Setting

We studied outcomes pre- and post-QI activities at the multi-specialty ambulatory clinic of the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas and its affiliated satellite clinics. More than half of the CRC screening eligible patient population relies on annual FOBT using the Hemoccult SENSA method as the dominant mode of screening. The study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the MEDVAMC Research and Development Committee.

Quality Improvement Initiatives

During calendar years 2004–2005, our institution launched a multifaceted QI effort to improve FOBT follow-up. First, pdf copies of CRC screening guidelines that were recently released at the time25 were disseminated to all primary care providers (PCPs) through electronic mail (e-mail) and a memorandum with summary of the guidelines were sent to the PCPs through their supervisor. Second, the gastroenterology (GI) service took measures to reduce colonoscopy backlog. The GI service assigned a dedicated allied health provider to process electronic consultations on a near-full time basis. It also made efforts to decrease the number of consultations received (especially unnecessary consultations) through two educational strategies: lectures to PCPs including residents rotating through the clinic and development and e-mail dissemination of an FOBT follow-up algorithm. Both these activities were geared to reduce backlog and waiting time for gastroenterology consults. For instance, activities emphasized the use of annual home based FOBT as the main tool for screening for low- or average-risk patients in lieu of screening colonoscopy, provided information on appropriateness of screening techniques and flagging urgent consultations. Third, our institution put into place several standard operating procedures regarding an electronic FOBT test result notification system. The VA uses an advanced electronic medical record (EMR)-based notification system (the View Alert system) that immediately alerts clinicians about clinically significant events such as critically abnormal test results. Our institution implemented a policy through which every positive FOBT test result was categorized as “critical” and hence was sent as a mandatory alert notification to the ordering provider and at times a back-up provider (such as the faculty supervisor of a resident trainee). All providers (approximately 50 PCPs) received alerts on their patient’s positive FOBT results and were expected to read them to initiate follow-up. Hence, this policy ensured mandatory notification, to providers and reduced potential breakdowns in communication between the laboratory and clinicians. Fourth, to augment the electronic communication through the EMR, an additional notification strategy was pursued. The preventive medicine coordinator, who is responsible for tracking VA performance measures, used a laboratory software program to identify all FOBT-positive tests and notified the patient’s primary care provider through a paper notification in their mail box (this occurred in each case in addition to the EMR alert). All PCPs whose patients had positive FOBT were sent the notice. Fifth, the coordinator regularly tracked the FOBT-positive cases for follow-up actions such as response by the PCP and colonoscopy performance. For instance, if no documentation of follow-up action by the provider (such as colonoscopy consultation, documentation of patient refusal of test etc.) was noted more than two weeks after the test, a second notice was sent to the PCP. Similarly, after a colonoscopy was requested, the coordinator tracked if an appointment was given. If not, paper copies of the consultation were sent on a monthly basis to one of the gastroenterologist for action. The coordinator then tracked patients to their colonoscopy appointments by maintaining a list of all the FOBT positive patients in a Microsoft Excel database. If patients cancelled or failed to show up for their appointments or for some reason the procedure was cancelled, providers were again informed through written notices. In addition to his usual job responsibilities of performance measurement reporting, the coordinator was able to dedicate approximately 4 hours a week to these tasks.

Data Collection

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We identified all FOBT-positive tests through a standardized laboratory extraction tool software program used by the VA system in a 12-month period pre- and post-QI implementation. From 1117 cases of positive FOBTs in the pre implementation phase from January 1, 2003 to December 31, 2003 we used computer generated randomization scheme to select 401 cases for review (a case was defined as one or more positive FOBT). Similarly, for the post implementation phase we randomly selected 399 cases to review out of 752 total cases from March 1, 2006 to February 28, 2007. The 800 positive FOBT cases were then randomly assigned to one of two chart reviewers, both of whom were staff primary care physicians (HK, GB). We supervised and trained the reviewers during pilot testing to ensure comprehensive and standardized data collection. Chart reviews for this study were conducted between September 2007 and November 2007.

Chart review

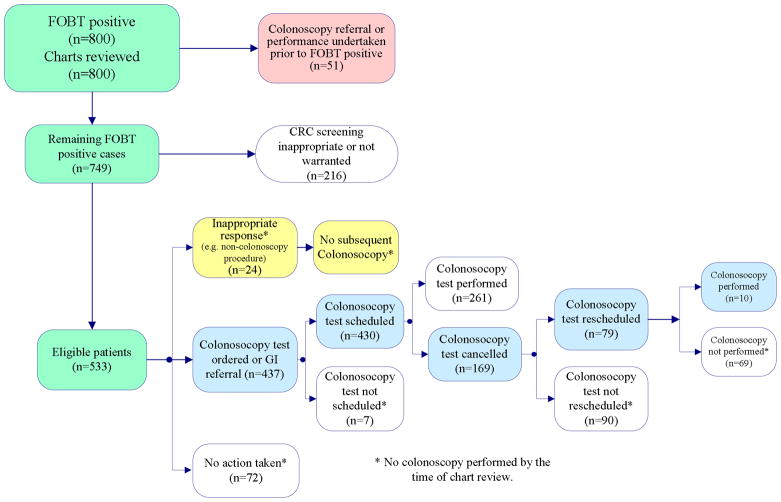

The data collection form was designed to capture several scenarios following a positive FOBT test result (see Figure 1) and was reviewed by multiple clinicians and pilot tested with the chart reviewers. Initially, charts were reviewed for evidence of colonoscopy referral or performance that may have taken prior to the positive FOBT; these were excluded. For the remaining cases, reviewers further examined the medical records for: 1) an evidence of follow-up actions by PCP and 2) performance of a colonoscopy at some time following the FOBT up to the date the chart was reviewed. For determining follow-up actions, reviewers documented four possible scenarios: 1) a colonoscopy referral was not indicated (e.g., documentation of patient refusal, documentation of colonoscopy being performed elsewhere, patient request for colonoscopy to be performed by a private physician), 2) follow-up actions were determined to be inappropriate (ordering non-colonoscopy procedures such as barium enema or flexible sigmoidoscopy, repeating FOBT), 3) follow-up actions were appropriate (ordering of colonoscopy or gastroenterology consult), or 4) no follow-up actions were documented. Reviewers recorded whether the inappropriate actions such as non-colonoscopy tests resulted in an ultimate colonoscopy or not. For cases where colonoscopy was ordered (either directly or through a referral to gastroenterology service), reviewers determined whether it was successfully scheduled and if scheduled whether it was performed. If not performed, they determined if the appointment was canceled by the gastroenterology service or by the patient (including a patient “no-show”) and if colonoscopy was rescheduled and performed after these situations. Times to PCP follow-up actions and colonoscopy performance were recorded. Although guidelines current at the time of our study did not explicitly state which patients should not undergo CRC screening with a colonoscopy,25–27 we used predefined criteria (Table 3) based on available literature25,27–30 to determine the appropriateness of screening colonoscopy. When providers missed the opportunity to take follow-up action on a positive FOBT, we determined the types of providers involved, and the types of visits involved (scheduled primary care follow-up visits versus unscheduled drop-in visits).

Figure 1.

IMPROVING THE FOLLOW-UP OF POSITIVE FECAL OCCULT BLOOD TEST RESULTS IN VETERANS

Table 3.

Criteria defining inappropriateness for CRC screening and associated colonoscopy related outcomes in 130 patients pre and post QI activities

| Inappropriate for CRC Screening (Categories) | Timely Colonoscopy | Non-Timely Colonoscopy | No Colonoscopy (lost to follow-up) at Chart Review | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Total | N | Total | N | Total | ||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||||

| 1. Terminal illness (e.g., cancer of the esophagus, liver or pancreas; enrolled in hospice; and/or life expectancy < 6 months; diagnosis of colorectal cancer or total colectomy) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| 2. Additional co-morbidities which are (a) are life-limiting, with anticipated life expectancy < 3 years; and/or (b) render patient unable to tolerate diagnostic colonoscopy or treatment if cancer is diagnosed.) * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 13 | 9 | 22 |

| 3. Not due for screening or colonoscopy based on previous confirmed colonoscopy result.) ** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 26 | 33 |

| 4. Age < 50 years old and at average risk for colon cancer | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| 5. Other reason patient was not appropriate for screening *** | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 15 | 10 | 25 |

| Total | 0 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 56 | 58 | 114 | ||

Potential exclusionary comorbidities included: advanced COPD with FEV1 <30%, NYHA class III or IV heart failure (symptoms of shortness of breath with daily activities or at rest); inoperable CAD; active malignancy being palliated or, if treatment with curative intent, less than 1 year in remission.

Potential exclusionary reasons included: documented report of a negative colonoscopy within past 10 years, polyps removed in previous colonoscopy but not currently due for surveillance.

Potential exclusionary reasons included documentation of a previous colonoscopy within past 10 years for which no formal report could be confirmed in the EMR

Outcome measures

Because definitions of appropriate follow-up vary greatly for cancer screening tests such as FOBT,1,6 we used recommendations from a 2007 VA Directive to determine pre- and post-implementation outcomes. 31 This policy on CRC screening and follow-up timelines for VA facilities defines timely referral for a colonoscopy to be within 14 days from an FOBT-positive report and timely colonoscopy performance as within 60 days from FOBT-positive report when a colonoscopy was indicated. The following outcome measures were calculated on eligible patients (Figure 1) i.e. for whom a colonoscopy was indicated:

Proportion of patients with a positive FOBT who received a timely (within 14 days) referral for colonoscopy;

Median time between a positive FOBT result and subsequent referral for colonoscopy;

Proportion of patients with a positive FOBT who received a timely (within 60 days) colonoscopy performance;

dian time between a positive FOBT result and subsequent performance of colonoscopy; and

Proportion of patients with positive FOBT who had not received a colonoscopy performance at the time of chart review.

Factors affecting colonoscopy performance

In addition to the factors known to affect colonoscopy performance such as patient non-adherence, we evaluated several factors that may lead to the non-performance of colonoscopy after positive FOBT. These included performance of a non-colonoscopy procedure such as barium enema or flexible sigmoidoscopy, cancellation of colonoscopy procedure by gastroenterology, not flagging consultation requests as urgent, PCPs not re-requesting consultations after an initial cancellation by gastroenterology, and when gastroenterology service did not reschedule consultations after an initial cancellation.

Data Analysis

The reviewers entered the variables into a Microsoft Access database, and study personnel checked 10% of cases to validate data entry. We used SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, version 9.1) to conduct all statistical analyses. Cases who met inclusion criteria were divided into two groups: pre and post implementation of QI activities and baseline characteristics between the two were compared. We then compared provider responses to the FOBT notifications (i.e., appropriate, inappropriate, no response) and the associated median duration between FOBT notification and response in the two groups. For patients who met final criteria for eligibility for colonoscopy (see Figure 1), we calculated and compared our five outcome measures (see above) in the pre- and post-implementation groups. To evaluate factors influencing the non-performance of colonoscopy, we first used univariate analysis using chi-square and t tests. Independent variables tested included performance of a non-colonoscopy procedure, patient non-adherence with colonoscopy appointment, cancellation of colonoscopy procedure appointment by gastroenterology, not flagging consultation requests as urgent, PCPs not re-requesting consultations after cancellation by gastroenterology, and when lack of rescheduling after an initial cancellation. Multivariable logistic regression model were used in which the outcome variable was whether or not a patient had a colonoscopy performed, and predictors included variables with p<.1 in the univariate analyses. The model was fit using maximum likelihood estimation, and odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

RESULTS

To evaluate the effectiveness of QI activities to improve the follow up of FOBT results with colonoscopy, we reviewed records of 401 and 399 FOBT positive patients respectively, each from a 12-month period pre- and post- implementation (total n=800). There was no significant age difference in the pre- and post- implementation groups (mean 64.8 and 63.3 years, respectively, p = .26). Race and gender distribution as well as the proportions of patients for whom colonoscopy was found not appropriate using predetermined criteria (specified in Table 3), were not significantly different in the two cohorts (see Table 1). Because colonoscopy referral or performance had taken place in 51 patients prior to the date of the positive FOBT, these patients were excluded from further analysis on follow-up actions.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all patients (n = 800) with a positive FOBT result before and after implementation of QI activities

| N | Total | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-QI (1/1/03-12-31-03) n=401 (%) | Post-QI (3/1/06-2/28/07) n=399 (%) | |||

| Race | ||||

| Black | 99 (24.7%) | 120 (30%) | 219 | 0.27 |

| Hispanic | 2 (.5%) | 3 (.7%) | 5 | |

| Other | 5 (1.2%) | 7 (1.7%) | 12 | |

| White non Hispanic | 288 (71.8%) | 260 (65.2%) | 548 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 12 (3%) | 9 (2.2%) | 21 | 0.52 |

| Male | 387 (96.5%) | 387 (97%) | 774 | |

| Appropriate for CRC screening | ||||

| No | 69 (17.2%) | 66 (16.5%) | 135 | 0.80 |

| Yes | 332 (82.8%) | 333 (83.5%) | 665 | |

| Colonoscopy referral or performance completed prior to FOBT positive report | 22 (5.5%) | 29 (7.3%) | 51 | 0.30 |

Table 2 shows follow-up actions and median times to follow-up action on the remaining 749 FOBT notifications. In 112 (15%) cases a follow-up action i.e. colonoscopy referral was not needed either because of patient refusal for further work-up, patient request to obtain it through a non-VA physician, patient report of the test having been performed elsewhere or documented evidence of one or more predefined exclusion criteria mentioned in Table 3. Cases that needed follow-up actions were further divided into appropriate, inappropriate and no follow-up documented. Appropriate follow-up response was documented in 485 (76.1%) of these cases. Median times to appropriate follow-up was significantly shorter post- implementation (6 vs. 18 days, p<0.0001). Inappropriate responses such as ordering a barium enema and repeating the FOBT occurred in 5.8% of cases, whereas no evidence of follow-up actions was documented in 115 (18%) cases.

Table 2.

Provider responses to 749 positive FOBT notifications and associated median times from notification to response (if any) pre and post implementation

| Response following a positive FOBT | N (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Pre-QI (n=379) | duration in days* Post-QI (n=370) | ||

| Appropriate response | 216(57.5) | 269(73.1) | <.0001 |

| 18 | 6 | <.0001 | |

| Inappropriate response | 31(8.2) | 6(1.6) | <.0001 |

| 54 | 15 | 0.06 | |

| •Barium Enema ordered | 9 (2.4) | 4(1.1) | |

| •Flexible Sigmoidoscopy ordered | 0 (0.0) | 1(0.3) | |

| •Provider attributed positive FOBT to other non-colonic causes | 12(28.6) | 0(0.0) | |

| •Provider repeated FOBT | 8(19.1) | 1(5.3) | |

| •Provider documented that patient was not a candidate for work-up (did not meet exclusion criteria listed in Table 3) | 2(4.8) | 0(0.0) | |

| Response not needed | 66(17.5) | 46(12.5) | 0.0559 |

| 92 | 6.5 | 0.0004 | |

| •Documentation by PCP of patient refusal | 19 (5.0) | 14(3.8) | |

| •Documentation by PCP of patient having had test at other location | 27(7.1) | 21(5.7) | |

| •Documentation of an exclusion criterion | 3 (7.1) | 0(0.0) | |

| •Documentation of patient preference to have private physician perform the test | 11(26.2) | 9(47.4) | |

| •Documentation of a previous colonoscopy performed elsewhere (within past 10 years) | 6(14.3) | 2(10.5) | |

| No documented response | 66 (17.4%) | 49 (13.2%) | 0.11 |

represented by shaded rows

Post- implementation, fewer positive FOBTs that were eligible for colonoscopy were followed by patient care visits that missed an opportunity to act on the abnormal finding [post (n=40; 7.5%) vs. pre (n=88; 16.5%) p <0.0001]. These visits included scheduled visits with the PCP and any visit, scheduled or not, in which the FOBT results should have been viewed for complete assessment. As expected, most missed opportunities occurred in the primary care setting and involved staff physicians (64%), followed by physician assistants (26%), nurse practitioners (6%), and trainees (5%). The type of visit most commonly associated with missed opportunities were routine primary care follow-up visits (86%), followed by “drop-in” unscheduled patient visits (9%) and visits to other medical subspecialists (3%). There was no significant difference in these characteristics pre and post implementation.

Of 749 patients, we found 130 patients where colonoscopic screening for CRC was found to be not appropriate, given current guidelines and literature. In Table 3, we describe their characteristics and outcomes. Just over 12% (16/130) had already undergone a colonoscopy for the positive FOBT when we reviewed their records.

For calculation of our outcome measures, we only used patients that were eligible for colonoscopy, i.e. we excluded those where screening was either not appropriate or where colonoscopy was determined as not needed. This led to exclusion of 216 patients in total (some patients met both exclusion criteria; also see Figure 1). Hence, 533 patients met eligibility criteria for calculation of our outcome measures. The proportions of patients who received a timely colonoscopy referral and performance were significantly higher post implementation (60.5% vs. 31.7%, p<0.0001 and 11.4% vs. 3.4%, p =0.0005 respectively). A significant decrease also resulted in median times to referral and performance post-implementation (6 vs. 19 days p<0.0001 and 96.5 vs. 190 days p<0.0001 respectively) and in the proportion of positive FOBT results with no follow-up by the time of chart review (24.3%vs. 35.9%; p=0.0045). Hence, all five outcome variables showed favorable significant change post- implementation of the QI activities (Table 4).

Table 4.

Study-related outcome variables pre- and post-implementation of QI activities in 533 FOBT positive patients for whom colonoscopy was indicated

| N | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-QI | Post-QI | ||

| Patients with a positive FOBT who received a colonoscopy referral within 14 days of test result | 83/262 (31.7%) | 164/271 (60.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Median time between a positive FOBT result and referral for colonoscopy (days) | 19 | 6 | <0.0001 |

| Patients with a positive FOBT who received a colonoscopy within 60 days of test result | 9/262 (3.44%) | 31/271 (11.44%) | 0.0005 |

| Median time between a positive FOBT result and performance of colonoscopy (days) | 190 | 96.5 | <0.0001 |

| Proportion of patients with positive FOBT without colonoscopy performance (determined at the time of chart review)* | 94/262 (35.9%) | 66/271 (24.3%) | 0.0045 |

11 patients in pre-QI and 4 patients in post-QI were found to have subsequently died either before or after colonoscopy referral but before its performance

In Table 5 we show results of several univariate analyses for factors potentially associated with colonoscopy performance (regardless of timely or not) in eligible patients. Significant factors associated with the lack of colonoscopy were performance of a non-colonoscopy procedure such as barium enema or flexible sigmoidoscopy, patient non-adherence to a colonoscopy appointment, colonoscopy request marked as routine i.e., not “urgent, not providing an appropriate provisional diagnosis on the consultation, gastroenterology service not rescheduling the colonoscopy procedure after an initial cancellation and PCPs not re-requesting colonoscopy after a procedure was cancelled by the gastroenterologist. In multivariable logistic regression model (data not shown in Table), we found that performance of a non-colonoscopy procedure such as barium enema or flexible sigmoidoscopy (OR=16.9; 95% CI 1.9–145.1), patient non-adherence (OR=33.9; 95% CI 17.3–66.6), not providing an appropriate provisional diagnosis on the consultation (OR= 17.9; 95% CI 11.3–28.1) and gastroenterology service not rescheduling colonoscopies (OR= 11.0; 95% CI 5.1–23.7) were significant predictors for lack of colonoscopy at chart review.

Table 5.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with colonoscopy performance in 533 FOBT positive patients for whom colonoscopy was indicated

| Factor | Colonoscopy Performed | No Colonoscopy performed | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total n=271 | Total n=262 | ||

| Performance of a non-colonoscopy procedure (Barium enema or flexible sigmoidoscopy) | 0 (0%) | 12 (4.6%) | 0.01 |

| Patient non-adherence to colonoscopy | 45 (16.6%) | 127 (48.5%) | <.0001 |

| Cancellation of a colonoscopy appointment by the Gastroenterology service | 9 (3.3%) | 16 (6.1%) | 0.66 |

| Colonoscopy request marked as routine i.e. not “urgent” | 218 (80.4%) | 134 (51.1%) | 0.0005 |

| Appropriate provisional diagnosis not provided on the consultation | 45 (16.6%) | 14 (5.3%) | <.0001 |

| PCP did not re-request colonoscopy after an initial cancellation | 1 (0.3%) | 54 (20.6%) | 0.6 |

| Gastroenterology service did not reschedule colonoscopy after initial cancellation | 13 (4.8%) | 71 (27.1%) | <.0001 |

Among 271 patients who had a colonoscopy performed on chart review, we found 16 to have cancer, giving an overall yield of 5.9% for colon cancer in our study population.

DISCUSSION

We studied the effect of several QI activities to improve the follow-up of positive FOBT results with a timely colonoscopy. Activities included improving the response of primary care providers to abnormal FOBTs and tracking positive tests till colonoscopy performance,. While the timeliness of colonoscopy referral and performance was not optimal according to recent VA policy recommendations, we found a significant increase in the proportion of patients who received a timely colonoscopy referral and a timely colonoscopy performance after implementation of these activities. The QI activities were also accompanied by a significant decrease in the median times for colonoscopy referral and performance and a significant decrease in the proportion of FOBT test results that were never followed-up. Prominent factors associated with a lack of performance of an indicated colonoscopy included patient non-adherence to scheduled colonoscopy appointments, and failure to re-request and reschedule cancelled colonoscopy procedures. Because colonoscopy was not indicated in approximately one third of patients with positive FOBT (267/800), our study raises concerns about current screening practices and the appropriate denominator used for performance measurement standards related to CRC screening.32 Our study also has implications beyond the VA to many other health care systems that rely mostly on FOBT testing, rather than screening colonoscopies, due to limited colonoscopy capacity.

Previous studies of activities to increase follow-up of abnormal cancer screens have mostly focused on patient-level factors and tests such as Papanicolaou smears.6,33–36 Relatively few studies have addressed systems-based practice and focused on providers, especially for FOBT follow-up.1,6,37 For instance, a study by Myers et al. provided physicians with reminders for abnormal FOBTs, accompanied by feedback on follow-up completion, educational visits, a tailored letter and a follow-up reminder call.37 A study by Manfredi 33 used procedures such as standardized communication from the exit nurse, a form that patients returned after compliance, and written and telephone reminders to improve compliance with referrals for several abnormal screening tests including FOBT. However, none of these studies were conducted in systems with integrated electronic medical records (EMRs), which potentially overcome test result notification barriers and facilitate tracking procedures.

While we did not measure the impact of the individual components of the QI activities, we believe that provider notification (both through alerts and mailbox) followed by monitoring performed by the preventive medicine coordinator likely provided the greatest benefit in improving the FOBT follow-up. Despite the use of an integrated EMR and tracking patients until colonoscopy completion, the timely referral and performance rates for eligible patients improved to only about 60% and 11% respectively. This inability to ensure subsequent follow-up in many cases is consistent with results of previous interventions that have used tracking procedures.12 Further performance improvement may result from activities not addressed by our initiatives, such as increasing capacity for colonoscopy procedures, improving care coordination processes that contribute to post-colonoscopy referral delays and patient education. Overall timeliness of follow-up of positive FOBT tests remained far less than those recommended by recent VA policy recommendations (median duration of 96.5 days to colonoscopy performance post implementation). These recommendations were released in early 2007, at the end of our study period, so their true impact on performance remains to be seen. Such QI activities highlight and accentuate the issue of limited endoscopic capacity, which is likely to worsen with further improvement in timely handling of positive FOBT results and clearing pending gastroenterology consults. Hence, these QI activities may paradoxically increase delays due to more referrals for colonoscopy and higher demand for this service. Despite these limitations, our activities resulted in improvement in provider to response to abnormal test results; moreover, these initiatives are feasible and relatively easy to implement within systems that use integrated EMRs.

Although a recommendation or referral for colonoscopy was made in about 80% of indicated cases, we found several inappropriate follow-up actions such as repeating the FOBT test and ordering a barium enema or flexible sigmoidoscopy. The frequency of these actions was much lower than that reported by Nadel et al. in 2005, an effect that could be partly explained by guideline diffusion over time.38 Despite provider notification, about 15% of positive FOBT cases lacked a documented follow-up plan at the time of chart review. Moreover, several opportunities to follow up the test result occurred subsequent to the date of the FOBT when providers could have “caught” the abnormality in a readily accessible EMR system. Many of these missed opportunities involved visits during which a comprehensive patient assessment, including a review of test results, was indicated.

Our study findings have implications for current and future policies and guidelines that address the timeliness or appropriateness of CRC screening. First, policy recommendations on timeliness, such as those released by the VA, must adopt benchmarks with explicit numerators and denominators in far more detail than currently done.31 Currently, outcomes for positive FOBT tests in situations when colonoscopy is not indicated are not well accounted for and could result in significant underestimations of timeliness. Such situations could occur because of a procedure performed elsewhere previously, patient refusal, or request for procedure performance elsewhere, and were found in over 10% of positive FOBT cases in our sample. Additionally, guidelines indicate that CRC screening is not required for up to 10 years following a negative colonoscopy but are silent on how to handle positive FOBTs in patients who have had a recent colonoscopy. 25,39 When we recalculated our outcome measures after including the 31 patients with recent negative colonoscopy in the denominator, the rates were slightly lower because none of them had received a timely colonoscopy. Of 216 patients where we found colonoscopy inappropriate or not warranted, only 17 (7.8%) eventually had a colonoscopy at chart review. Hence, our findings are conservative estimates of underutilization of colonoscopy. Anecdotally, we have noticed a low yield for tests with recent negative colonoscopy. Currently in our system, most PCPs do not obtain FOBTs on patients who have had a recent negative colonoscopy. Given that the median time from FOBT result to colonoscopy performance was 96.5 days, our findings also suggest a need for numerators that reflect achievable evidence based practice goals; the 60-day colonoscopy performance recommendation may not be easily achievable currently without increased endoscopic capacity. When we used a 90-day time frame, the proportion of patients with timely performance was slightly better (post-implementation 27.3% versus pre-implementation 10.3%). Using a 120 day window, timely performance increased to 36.5% post-QI versus 16% pre-QI. In a previous study, we found no difference in outcomes (stage/survival) of patients with CRC diagnosed within 30, 60 or 90 days of positive FOBT. 40

Second, during both pre- and post- implementation periods we found a large proportion of FOBTs (~17%) were performed on patients when the test was likely not indicated. This problem has received heightened attention in recent literature,28,30,41 however, recently released guidelines do not adequately address who should not be screened for CRC.39 These FOBTs further strain an already limited endoscopic capacity. While only a small percentage of these patients (12.3%) ultimately underwent a colonoscopy in our study, the findings call for more explicit appropriateness criteria to prevent the diversion of resources to patients who may not necessarily need them. Such defined exclusion parameters could link to electronic FOBT reminders in the medical record to guide providers and their patients to make informed choices. Notably, many of our exclusionary criteria were facility-specific and not currently used in a standardized fashion nationwide to calculate VA performance measures.

Our study has implications not just for the VA but also other health care institutions that use FOBT for screening due to limited colonoscopy capacity. These institutions should consider implementing sophisticated EMR systems for improving follow-up of abnormal screen findings.42 In addition to improving electronic communication related to test results and consultations, further reduction in diagnostic delays43 will also be possible with advent of systems that are able to track colonoscopy completion post-referral. We believe that use of information technology and case managers with dedicated time could facilitate tracking procedures.44 Consistent with previous studies, 16,45 we found that patient adherence to colonoscopy was a significant barrier in getting a full colon evaluation. Previous interventions have focused on improving patient adherence to methods of cancer screening.46–48 However, interventions to improve patient adherence to follow-up procedures related to abnormal cancer screens are also warranted.19,33,37,49–51 Also needed are better systems of arranging follow-up procedures after cancellations, a common scenario in ambulatory care practice. Whether the primary care provider re-requests a procedure or the gastroenterologist reschedules it on their own may depend on institutional practices, but this problem may be improved by better tracking systems20,52–54 using either reminders built into the EMR or navigation programs for patients with suspected cancer.19,55–57

Our study has several strengths. Access and follow-up in the VA system is less affected by financial factors. In addition, the VA EMR allows for a comprehensive review of available data. Many previous studies6,11,18,38,58,59 have used either administrative data or patient self-reports to measure follow-up, but standardized medical chart review overcomes some of the limitations of these methods.60

Our results should be interpreted with several limitations. This was a single institution study and the findings may not be generalizable to the study population of other VA facilities or to non-VA settings. Due to our retrospective chart review design we were not able to determine precisely why providers did not follow-up on the FOBT results data, nor could we comprehensively examine the many other factors that may affect timely colonoscopy performance. Although we were able to able to capture and account for many dual users of both VA and non-VA services through detailed chart review61, we may have missed some instances where information about colonoscopies in non-VA settings was not documented in the EMR. Additionally, due to resource limitations, our QI activities did not involve patient contact.

Conclusions

Multifaceted QI activities that focused on improving provider response to positive FOBT and reducing gastroenterology backlog improved the rates of timely colonoscopy referral and performance in an EMR system. Performance rates could be further improved by dedicated systems of care coordination and tracking to colonoscopy completion and possibly by improved colonoscopy capacity, requiring additional resource investment. Future patient-, provider-, and systems-based interventions are needed to improve timeliness of colonoscopy performance and patient adherence to diagnostic procedures.

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS.

1) What is current knowledge?

Fecal occult blood test (FOBT) is commonly used for colorectal cancer screening in several health care settings

Inadequate follow-up of FOBT results with a colonoscopy is common

Patient-level, provider-level, or system-level factors may be responsible

Relatively few studies address strategies to improve follow-up of abnormal cancer screens such as abnormal FOBTs

2) What is new here?

We report findings before and after quality improvement initiatives to improve follow up for abnormal FOBTs

For various reasons, a follow-up colonoscopy was not indicated in many cases of abnormal FOBTs

Multifaceted quality improvement activities improved rates of timely colonoscopy referral and performance

Our study raises some concerns about current performance measurement and screening practices

Acknowledgments

Funding Source

The study was supported by an NIH K23 career development award (K23CA125585) to Dr. Singh, and in part by the Houston VA HSR&D Center of Excellence (HFP90-020) and the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center. These sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Drs. Singh and Walder had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reference List

- 1.Yabroff K, Washington KS, Leader A, Neilson E, Mandelblatt J. Is the Promise of Cancer-Screening Programs Being Compromised? Quality of Follow-Up Care after Abnormal Screening Results. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60:294–331. doi: 10.1177/1077558703254698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baig N, Myers RE, Turner BJ, et al. Physician-reported reasons for limited follow-up of patients with a positive fecal occult blood test screening result. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;98:2078–2081. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin B, Hess K, Johnson C. Screening for colorectal cancer. A comparison of 3 fecal occult blood tests. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:970–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris JB, Stellato TA, Guy BB, Gordon NH, Berger NA. A critical analysis of the largest reported mass fecal occult blood screening program in the United States. Am J Surg. 1991;161:101–105. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(91)90368-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burack RC, Simon MS, Stano M, George J, Coombs J. Follow-up among women with an abnormal mammogram in an HMO: is it complete, timely, and efficient? Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:1102–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastani R, Yabroff KR, Myers RE, Glenn B. Interventions to improve follow-up of abnormal findings in cancer screening. Cancer. 2004;101:1188–1200. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, et al. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1603–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1365–1371. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305133281901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kronborg O, Jorgensen OD, Fenger C, Rasmussen M. Randomized study of biennial screening with a faecal occult blood test: results after nine screening rounds. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:846–851. doi: 10.1080/00365520410003182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Serag HB, Petersen L, Hampel H, Richardson P, Cooper G. The Use of Screening Colonoscopy for Patients Cared for by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2202–2208. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.20.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etzioni D, Yano E, Rubenstein L, et al. Measuring the Quality of Colorectal Cancer Screening: The Importance of Follow-Up. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2006;49:1002–1010. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen ZJ, Kammer D, Bond JH, Ho SB. Evaluating follow-up of positive fecal occult blood test results: lessons learned. J Healthc Qual. 2007;29:16–20. 34. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2007.tb00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lurie JD, Welch HG. Diagnostic Testing Following Fecal Occult Blood Screening in the Elderly. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1641–1646. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.19.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myers RE, Balshem AM, Wolf TA, Ross EA, Millner L. Screening for colorectal neoplasia: physicians’ adherence to complete diagnostic evaluation. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1620–1622. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.11.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klos SE, Drinka P, Goodwin JS. The utilization of fecal occult blood testing in the institutionalized elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:1169–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb03569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher DA, Jeffreys A, Coffman CJ, Fasanella K. Barriers to full colon evaluation for a positive fecal occult blood test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1232–1235. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shields HM, Weiner MS, Henry DR, et al. Factors that influence the decision to do an adequate evaluation of a patient with a positive stool for occult blood. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;96:196–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner B, Myers RE, Hyslop T, et al. Physician and Patient Factors Associated with Ordering a Colon Evaluation After a Positive Fecal Occult Blood Test. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:357–363. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3:19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh H, Arora HS, Vij MS, Rao R, Khan M, Petersen LA. Communication outcomes of critical imaging results in a computerized notification system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14:459–466. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wahls T. Diagnostic errors and abnormal diagnostic tests lost to follow-up: a source of needless waste and delay to treatment. J Ambul Care Manage. 2007;30:338–343. doi: 10.1097/01.JAC.0000290402.89284.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahls TL, Cram PM. The frequency of missed test results and associated treatment delays in a highly computerized health system. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boohaker EA, Ward RE, Uman JE, McCarthy BD. Patient notification and follow-up of abnormal test results. A physician survey. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh H, Thomas EJ, Petersen LA, Studdert DM. Medical Errors Involving Trainees: A Study of Closed Malpractice Claims From 5 Insurers. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2030–2036. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: Clinical guidelines and rationale--Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pignone M, Rich M, Teutsch SM, Berg AO, Lohr KN. Screening for Colorectal Cancer in Adults at Average Risk: A Summary of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:132–141. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davila RE, Rajan E, Baron TH, et al. ASGE guideline: colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:546–557. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sultan S, Conway J, Edelman D, Dudley T, Provenzale D. Colorectal Cancer Screening in Young Patients With Poor Health and Severe Comorbidity. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2209–2214. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.20.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris JK, Froehlich F, Gonvers JJ, Wietlisbach V, Burnand B, Vader JP. The appropriateness of colonoscopy: a multi-center, international, observational study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:150–157. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher DA, Galanko J, Dudley TK, Shaheen NJ. Impact of comorbidity on colorectal cancer screening in the veterans healthcare system. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Veterans Affairs and Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 2007–004 Colorectal Cancer Screening. 2007:1–12. Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walter LC, Davidowitz NP, Heineken PA, Covinsky KE. Pitfalls of Converting Practice Guidelines Into Quality Measures: Lessons Learned From a VA Performance Measure. JAMA. 2004;291:2466–2470. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manfredi C, Lacey L, Warnecke R. Results of an intervention to improve compliance with referrals for evaluation of suspected malignancies at neighborhood public health centers. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:85–87. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holschneider CH, Felix JC, Satmary W, Johnson MT, Sandweiss LM, Montz FJ. A single-visit cervical carcinoma prevention program offered at an inner city church: A pilot project. Cancer. 1999;86:2659–2667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marcus AC, Kaplan CP, Crane LA, et al. Reducing loss-to-follow-up among women with abnormal Pap smears. Results from a randomized trial testing an intensive follow-up protocol and economic incentives. Med Care. 1998;36:397–410. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199803000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller SM, Siejak KK, Schroeder CM, Lerman C, Hernandez E, Helm CW. Enhancing adherence following abnormal Pap smears among low-income minority women: a preventive telephone counseling strategy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:703–708. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.10.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Myers RE, Turner B, Weinberg D, et al. Impact of a physician-oriented intervention on follow-up in colorectal cancer screening. Prev Med. 2004;38:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadel MR, Shapiro JA, Klabunde CN, et al. A National Survey of Primary Care Physicians’ Methods for Screening for Fecal Occult Blood. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:86–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-2-200501180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer and Adenomatous Polyps, 2008: A Joint Guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:130–160. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wattacheril J, Kramer JR, Richardson P, et al. Lagtimes in diagnosis and treatment colorectal cancer: determinants and association with cancer stage and survival [Epub ahead of print] Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gross CP, McAvay GJ, Krumholz HM, Paltiel AD, Bhasin D, Tinetti ME. The Effect of Age and Chronic Illness on Life Expectancy after a Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer: Implications for Screening. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:646–653. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-9-200611070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klabunde CN, Riley GF, Mandelson MT, Frame PS, Brown ML. Health plan policies and programs for colorectal cancer screening: a national profile. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh H, Sethi S, Raber M, Petersen LA. Errors in cancer diagnosis: current understanding and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5009–5018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh H, Naik A, Rao R, Petersen L. Reducing Diagnostic Errors Through Effective Communication: Harnessing the Power of Information Technology. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:489–494. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0393-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kazarian ES, Carreira FS, Toribara NW, Denberg TD. Colonoscopy completion in a large safety net health care system. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:438–442. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coughlin SS, Costanza ME, Fernandez ME, et al. CDC-funded intervention research aimed at promoting colorectal cancer screening in communities. Cancer. 2006;107:1196–1204. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myers RE, Ross EA, Wolf TA, Balshem A, Jepson C, Millner L. Behavioral interventions to increase adherence in colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 1991;29:1039–1050. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Myers RE, Sifri R, Hyslop T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the impact of targeted and tailored interventions on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer. 2007;110:2083–2091. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng YF, Saito T, Takahashi M, Ishibashi T, Kai I. Factors associated with intentions to adhere to colorectal cancer screening follow-up exams. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:272. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Myers RE, Fishbein G, Hyslop T, et al. Measuring complete diagnostic evaluation in colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Detect Prev. 2001;25:174–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stern MA, Fendrick AM, McDonnell WM, Gunaratnam N, Moseley R, Chey WD. A randomized, controlled trial to assess a novel colorectal cancer screening strategy: the conversion strategy--a comparison of sequential sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy with immediate conversion from sigmoidoscopy to colonoscopy in patients with an abnormal screening sigmoidoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2074–2079. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gandhi TK, Sequist TD, Poon EG, et al. Primary care clinician attitudes towards electronic clinical reminders and clinical practice guidelines. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003:848. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murff HJ, Gandhi TK, Karson AK, et al. Primary care physician attitudes concerning follow-up of abnormal test results and ambulatory decision support systems. Int J Med Inform. 2003;71:137–149. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(03)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei EK, Ryan CT, Dietrich AJ, Colditz GA. Improving Colorectal Cancer Screening by Targeting Office Systems in Primary Care Practices: Disseminating Research Results Into Clinical Practice. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:661–666. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Freeman HP. Patient navigation: a community centered approach to reducing cancer mortality. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21:S11–S14. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2101s_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ell K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, Xie B. Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: A randomized clinical trial. Preventive Medicine. 2007;44:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Battaglia TA, Roloff K, Posner MA, Freund KM. Improving follow-up to abnormal breast cancer screening in an urban population. A patient navigation intervention. Cancer. 2007;109:359–367. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yabroff KR, Klabunde CN, Myers R, Brown ML. Physician Recommendations for Follow-Up of Positive Fecal Occult Blood Tests. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62:79–110. doi: 10.1177/1077558704271725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharma VK, Vasudeva R, Howden CW. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance practices by primary care physicians: results of a national survey. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;95:1551–1556. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gordon NP, Hiatt RA, Lampert DI. Concordance of self-reported data and medical record audit for six cancer screening procedures. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:566–570. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.7.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Byrne MM, Kuebeler M, Pietz K, Petersen LA. Effect of using information from only one system for dually eligible health care users. Med Care. 2006;44:768–773. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000218786.44722.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]