Abstract

Although youth with internalizing symptoms experience friendship difficulties, surprisingly little is known about their problematic interpersonal behaviors. The current observational study identifies a new construct, conversational self-focus, defined as the tendency to direct the focus of conversations to the self and away from others. Results indicated that youth with internalizing symptoms were especially likely to engage in self-focus when discussing problems with friends and that doing so was related to their friends perceiving the relationship as lower in quality, particularly helping. Content analyses further indicated that self-focused youth talked about themselves in ways that were distracting from their friends’ problems and that they changed the subject abruptly. Last, conversational self-focus was not redundant with related constructs of rumination and self-disclosure. This research highlights the importance of intervention efforts aimed at teaching self-focused youth ways to cope with distress that are more effective and will not damage their friendships.

Friends are important to youth, especially at adolescence when they become central sources of support (e.g., Buhrmester & Prager, 1995; Sullivan, 1953). Youth with internalizing symptoms can benefit from close friendships, but they may exhibit aversive behaviors that undermine relationships. Although it is commonly thought that youth with internalizing symptoms have maladaptive interpersonal interactions, surprisingly little is known about their particular interpersonal behaviors. This study examines a previously understudied behavior expected to be related to internalizing symptoms, conversational self-focus.

Conversational self-focus is defined as the tendency of one person to redirect conversations toward the self and away from others. As a result, self-focused youth may dominate interactions. For the current research, this style is hypothesized to be more common among youth with internalizing symptoms and to be associated with relationship problems. This study examines conversational self-focus in a community sample of adolescent friends and is designed to a) test relations of self-focus with internalizing symptoms and friendship outcomes, b) identify specific behaviors self-focused youth use to redirect conversations, and c) demonstrate construct validity. The use of a multi-method design involving behavior observation, self-report of internalizing symptoms, and friend-report of friendship quality provided a rigorous test of hypotheses. The test also is conservative as laboratory-based observational studies catch only small slices of behavior.

Internalizing Symptoms and Friendships

A notable minority of youth experience internalizing symptoms (e.g., Bell-Dolan, Last, & Strauss, 1990; Nolen-Hoeksema, Girgus, & Seligman, 1986), which predict difficulties such as lower self-esteem, academic problems, and substance use (e.g., Hammen & Rudolph, 2003; Lewinsohn, Solomon, Seeley, & Zeiss, 2000; Reinherz, Frost, & Pakiz, 1991; Strauss, Frame, & Forehand, 1987). One area of interest has been associations with peer relations (see Gotlib & Hammen, 1992; Rudolph & Asher, 2000). Depressive (e.g., Cole, 1990; Kiesner, 2002; Panak & Garber, 1992) and anxiety (e.g., Rudolph, Hammen, & Burge, 1994) symptoms predict rejection by the overall peer group.

Youth with internalizing symptoms may fare better in dyadic friendships. Studies of youth in community samples suggest that depressive symptoms may not be related to how many friends youth have (Brendgen, Vitaro, Turgeon, & Poulin, 2002; Demir & Urberg, 2004), and no identified studies indicated anxiety symptoms were linked with having fewer friends. These findings are important given that youth with internalizing symptoms could reap benefits of having friends, including affection, intimacy, and helping (Weiss, 1974).

Unfortunately, however, friendship quality may be affected by youths’ emotional problems. Evidence is mixed with some studies indicating concurrent relations between depressive symptoms and decreased positive friendship quality (Brendgen et al., 2002; Demir & Urberg, 2003, for boys only) and others finding no effects (Hussong, 2000; LaGreca & Harrison, 2005; Prinstein, 2007). Fewer studies address anxiety, but one study suggests that anxiety symptoms may be related to poorer friendship quality (Fordham & Stevenson-Hinde, 1999). While it is somewhat surprising that these effects are not more consistent, the mixed results may be related to the studies’ focus on concurrent relations, as the damaging impact of internalizing symptoms may become stronger with time. For example, friendships of youth with depressive symptoms are found to be especially unstable over time (Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon, & Aikins, 2005).

Aversive Interpersonal Behaviors: Considering the New Construct of Conversational Self-Focus

Interpersonal theories of depression (e.g., Coyne, 1976a; Gotlib & Hammen, 1992; Joiner, Coyne, & Blalock, 1999) provide a framework for understanding why internalizing symptoms may damage relationships. In an effort to feel close to others, depressed individuals may behave in aggravating ways that result in rejection. Ironically, rejection can lead to increased depressive symptoms and trap individuals in an ongoing cycle of depression, maladaptive behaviors, and rejection. Despite the call to identify mechanisms at work in this cycle (e.g., Coyne 1991; Joiner, Alfano, & Metalsky, 1992), few behaviors have been identified.

Two depression-related behaviors that have been studied are excessive reassurance-seeking (ERS) and negative feedback-seeking (NFS). ERS is the tendency to request assurances from others that one is cared for (e.g., Joiner et al., 1992; Joiner & Metalsky, 2001; Joiner & Schmidt, 1998) and is related to depressive symptoms in adults (e.g., Joiner et al., 1992) and adolescents (Prinstein et al., 2005). NFS is the tendency to solicit criticism from close others (Joiner, 1995; Pettit & Joiner, 2001) and is related to depressive symptoms in clinical (Joiner, Katz, & Lew, 1997), community (Cassidy, Ziv, Mehta, & Feeney, 2003), and adolescent (Borelli & Prinstein, 2006) samples.

These studies provide important groundwork indicating that individuals with depressive symptoms engage in behaviors that may damage relationships. However, depressive symptoms almost certainly are related to a broader range of problematic behaviors. Moreover, although youth with anxiety symptoms tend to withdraw in peer groups (Rubin & Burgess, 2001), less is known their behavior in specific friendships. The current study addresses these gaps by examining relations of depressive and anxiety symptoms with conversational self-focus.

As noted, conversational self-focus is defined as redirecting conversations toward the self and away from others. Self-focus is considered a variant of normative self-disclosure, commonly defined as the reciprocal process of revealing personal information to others who, in turn, divulge similarly personal information (e.g., Derlega, Metts, Petronio, & Margulis, 1993; Miller & Kenny, 1986). Self-focus departs from the give-and-take of normative self-disclosure as it involves a focus on one conversation partner to the exclusion of the other. Although the literature acknowledges the possibility of similar, non-reciprocal disclosure styles (e.g., Coyne, 1976b; Cozby, 1973; Vangelisti, Knapp, & Daly, 1990), this construct has not been studied empirically.

Notably, individuals may self-focus in positive, negative, or neutral contexts. For example, one could self-focus about personal successes, worries and concerns, or even mundane information. In the current study, self-focus was assessed in the context of adolescents’ conversations about problems with friends because self-focus in this context may be especially inappropriate and aversive. That is, when youth talk about problems, they likely expect friends’ attention and support, which self-focused youth may be unwilling or unable to give. Instead, these youth may turn the focus to themselves and dominate conversations. We further propose two specific ways that self-focused youth may redirect conversations. First, self-focused youth may respond to friends’ problems by talking about their own experiences that are only tangentially related to the friends’ problem. Moreover, they even may explicitly change the subject to a different topic that they want to discuss.

Internalizing Symptoms and Conversational Self-Focus

In the current study, conversational self-focus is expected to be especially common among youth with elevated internalizing symptoms. Individuals with depressive (e.g., Hamilton & Deemer, 1999; Pyszczynski & Greenberg, 1986) and anxiety (e.g., Cheek & Briggs, 1990; Kowalski & Leary, 1990) symptoms exhibit increased self-focused attention (e.g., rumination), which may be reflected behaviorally, especially during problem talk with friends. That is, youth with internalizing symptoms may utilize talking with friends to voice their concerns and have difficulty disengaging from problems due to the persistent, consuming nature of their rumination. Additionally, this ruminative bias may impair their ability to respond to social cues appropriately (e.g., a friend wanting to talk). This hypothesis fits with research suggesting that individuals with depressive symptoms are especially likely to make self-referent comments (Jacobsen & Anderson, 1982; Mehl, 2006). It also is consistent with past research indicating that youth with internalizing symptoms engage in co-rumination, defined as extensively discussing and revisiting problems, speculating about problems, and focusing on negative affect (e.g., Rose, 2002). However, whereas co-rumination is thought to be a reciprocal dyadic process, self-focus is explicitly one-sided.

Conversational Self-Focus and Friendship Outcomes

Additionally, youths’ observed self-focus during problem talk is expected to be related to lower friend-reported positive friendship quality. Although friends can provide support as youth face the challenges of adolescence (e.g., Papini, Farmer, Clark, Micka, & Barnett, 1990), youth with self-focused friends are unlikely to reap the benefits of normative self-disclosure (e.g., help with problems) if the focus is repeatedly drawn away from them. Instead, they may feel unsupported and that they cannot rely on self-focused youth for help or support. Thus, friends of self-focused youth may report that their friendships are of lower positive quality, especially in regards to perceiving the friendship as helpful.

Conversational Self-Focus and Associated Constructs: Rumination and Self-Disclosure

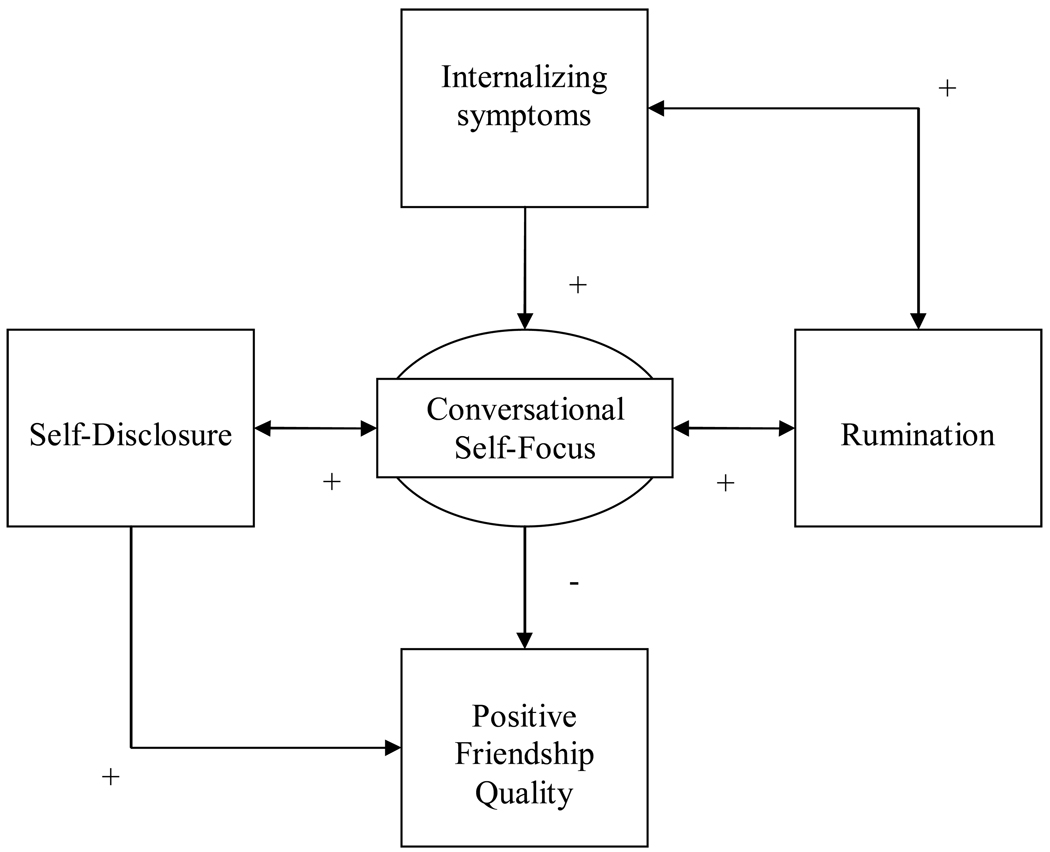

Importantly, conversational self-focus is not redundant with related cognitive and social-behavioral constructs (see Figure 1 for a representation of expected relations). In regards to cognitive constructs, conversational self-focus is proposed to be related, yet not identical, to cognitive self-focus, also referred to as self-focused attention (SFA). SFA is a concentration on self-relevant information (Mor & Winquist, 2002) and can play an important role in adaptive self-regulation, motivation, and goal-directed behavior (Carver & Schier, 1998). However, SFA also can be related to negative affect (e.g., Duval & Wicklund, 1972) and more serious problems such as internalizing symptoms (e.g., Ingram, 1990a). One aspect of SFA, rumination (i.e., focus on own negative affect), is consistently linked with internalizing symptoms (Ingram, 1990b; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). As conversational self-focus is hypothesized to be a behavioral manifestation of the self-focused (i.e., ruminative) cognitive state, a positive relation of conversational self-focus with rumination is expected. Rumination also is expected to be related to internalizing symptoms but not necessarily to friendship quality, as rumination is not behavioral.

Figure 1.

Pictoral representation of nomological network surrounding conversational self-focus.

Additionally, conversational self-focus is proposed to be related to, yet not redundant with, normative self-disclosure. Because self-focus is proposed to be a variant of self-disclosure, a significant association is expected. However, the relation is not expected to be especially strong as friends may engage in reciprocal disclosure with neither friend self-focusing. Differential relations of self-focus and self-disclosure with internalizing symptoms and friendship outcomes also are expected. Unlike self-focus, normative self-disclosure is not expected to be related to elevated internalizing symptoms. Moreover, youth who engage in normative self-disclosure are expected to have friends who report the friendship is high in positive quality, as self-disclosure is a core component of adolescent friendships (e.g., Berndt, 2002; Parker & Asher, 1993).

Method

Participants

Participants were 60 tenth-grade youth (M age = 15) in 30 same-sex friendship dyads (15 male and 15 female dyads). Rosters of all tenth graders were obtained from a Midwestern public school district, and 146 students were randomly selected for recruitment. Youth were asked to identify a best or close friend with whom they would like to participate. Of the families who were mailed recruitment materials, 42 agreed to participate, 78 declined, and 18 families were unable to be reached via telephone. Reasons for declining primarily included difficulty in scheduling and the modest incentive ($10 gift certificate to a local mall). Of the 42 youth who agreed to participate, 34 completed the study with a friend. The other 8 youth who agreed did not attend their appointments. Of the 34 youth who participated, two were friends and formed one dyad; accordingly, the total number of dyads was 33. Due to technical problems with the videotapes, data for 3 dyads could not be used. The final sample of 60 youth in 30 dyads was 85% Caucasian, 12% African American, and 3% Asian American. Youth also reported whether the friend with whom they visited the lab was a “best friend”, “close friend”, “just a friend”, or “not a friend.” All youth reported participating with a best (71%) or close friend (29%).

Procedure

Parental consent and youth assent for each participant was obtained before lab sessions began. Lab sessions lasted about 90 minutes. Prior to the observation, each friend completed self-report measures in separate rooms. One measure asked youth to list three problems they had. Youth were asked to choose one they were willing to discuss with their friend and then were reunited for the observation in a room with a table, two chairs, and a video camera. The camera fed into an adjacent room where the interaction was recorded and monitored.

The observation segment involved a warm-up task (planning a party) and a problem talk task of interest for this study. Youth were asked to discuss the problem they generated during the survey assessment and were told they would have about 20 minutes to talk about the problems. They were told to talk about each person’s problem, that it did not matter whose problem was discussed first, and that they could talk about anything they wanted to about the problem. They also were told that if they finished talking about problems, they could play with a puzzle that was on the table. After 16 minutes, the experimenter stopped the interaction.

Measures

Depression symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed with 26 of the 27 items of the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992). As in some past studies (e.g., Crick & Grotpeter, 1995; Prinstein, 2007), the suicidality item was dropped. The item was dropped due to concerns raised by parents in past research conducted in the same community from which the current sample was drawn regarding the item’s sensitivity. Items were rated 0, 1, or 2 to reflect the degree to which each statement was true. Participants were given a mean score for the 26 items (α = .83).

Anxiety symptoms

Anxiety symptoms were assessed with the 28-item Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale-Revised (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1978). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “Not at all true” to 5 “Really true.” Youth received a mean score for the 28 items (α = .91).

Friendship quality

Youth responded to an 18-item revised version of the Friendship Quality Questionnaire (Rose, 2002; revision of Parker & Asher, 1993). The original FQQ assesses five positive friendship quality subscales and one conflict subscale with 3 to 9 items each. In the revised version, each of the subscales included 3 items. Of interest to the current study were the 15 items of the positive subscales assessing companionship and recreation, conflict resolution, help and guidance, intimacy, and validation and caring. Each questionnaire was customized with the friend’s name inserted into every item. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “Not at all true” to 4 “Really true.” Given the focus of this study on friends’ perceptions, only friends’ reports of friendship quality were used.

Research using the Friendship Quality Questionnaire suggests that it is appropriate to utilize subscale scores separately in analyses (e.g., Parker & Asher, 1993) or to create a composite score for positive friendship quality (e.g., Rose & Asher, 2004; Rudolph, Ladd, & Dinella, 2007). The current study used both approaches in order to maximize reliability (i.e., composite score utilized more items) and address specific hypotheses (e.g., self-focus would be most strongly related to help and guidance). Cronbach’s alpha for the composite score was high (α =.89). Acceptable reliabilities were found for the help and guidance (α = .75), intimacy (α = .78), and validation and caring subscales (α = .80). However, the reliabilities were lower for companionship and recreation (α = .55) and conflict resolution (α = .65). Therefore, results involving these two subscales should be interpreted cautiously. Correlations among the positive subscales were positive and significant (r’s from .32 to .69, p’s < .05; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations among Self-Focus, Internalizing Symptoms, Positive Friendship Quality, Rumination, and Self-Disclosure

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | a | b | c | d | e | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Global self-focus | -- | .43*** | .34** | −.18 | −.10 | −.19 | −.24† | −.05 | −.15 | .29* | −.16 |

| 2. Self-focus proportion | -- | -- | .29* | −.20 | −.09 | −.16 | −.26* | −.12 | −.17 | .38** | −.02 |

| 3. Internalizing symptoms | -- | -- | -- | −.10 | −.09 | −.14 | −.16 | .02 | .00 | .61**** | −.00 |

| 4. Positive FQ (composite) | -- | -- | -- | -- | .66**** | .78**** | .84**** | .83**** | .86**** | .02 | .42*** |

| a. Companionship and recreation |

-- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .32* | .56**** | .34** | .47*** | .08 | .10 |

| b. Conflict resolution | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .67**** | .54**** | .62**** | .03 | .29* |

| c. Help and guidance | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .61**** | .57**** | −.13 | .33** |

| d. Intimacy | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .69**** | .08 | .54**** |

| e. Validation and caring | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.01 | .35** |

| 5. Rumination | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .05 |

| 6. Self-disclosure | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Notes. p=.06

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

p < .0001.

Rumination

A revised version (Rose, 2002) of the Responses to Depression Questionnaire (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) assessed the degree to which youth dwelled on negative affect. Wording for 15 of the 21 original items were revised for use with youth. The instructions read, “What do you usually do when you feel down, sad, or depressed?” and participants rated each item on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “Almost never” to 4 “Almost always.” Scores were the mean of the 21 ratings (α = .92).

Self-disclosure

Youth responded to three items assessing the extent to which they self-disclose within a specific friendship (Rose, 2002; items adapted from Parker & Asher, 1993). The items were: “We talk to each other about the things that make us sad,” “When one of us is mad about something that happened to us, we can always talk to each other about it,” and “We are always telling each other about our problems.” Scores were the mean of the items (α = .89).

Conversational Self-Focus Coding

Before coding observations, interactions were transcribed verbatim by undergraduate research assistants. Transcribers incorporated established transcription symbols (e.g., West & Zimmerman, 1985) to add further detail (e.g. verbal inflection, interruptions). Transcripts were double-checked for accuracy by a second transcriber. All transcribers and coders were blind to youths’ survey data.

Coding self-focus involved three major steps

The first two yielded overall self-focus scores. As noted previously, conversational self-focus is conceptualized as involving turning conversations toward the self and dominating conversations. Therefore, the construct was operationalized with two indicators. The first was a global score assigned to each youth based on the entire conversation and reflecting the degree to which the youth turned conversations to focus on themselves. The second was a proportion score reflecting the degree to which a youth focused on his/her problems relative to the degree to which the other friend focused on his/her problems (i.e., degree of domination during conversation). The two indicators were expected to be significantly and moderately related given that they tap different aspects of the same construct. The third step involved coding the content of self-focused youths’ speech.

For each of the three self-focus codes, a general procedure was used for training and establishing reliability of coders. First, the primary investigator of the project (who served as a coder) and one other coder discussed the conceptual and logistic aspects of each code and reviewed several transcripts together. Next, the two coders coded several dyads individually and met to discuss any disagreements. Then, the two coders individually coded 20% of the interactions to ensure good reliability. The remaining 80% of the interactions then were coded, including the re-coding of interactions used during training.

Global score

Each friend was rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 “Not at All/Very Little” to 5 “All the Time/Very Much” reflecting the degree to which the youth redirected conversations to focus on the self. Youth receiving a rating of 1 generally refrained from making self-statements in response to friends’ problem statements. Youth receiving a 3 displayed a moderate degree of conversational self-focus. For example, they might talk about themselves in the context of the friend’s problem (e.g., offer examples of when they were in similar situation). Youth receiving a rating of 5 repeatedly turned the conversation to focus on themselves in response to their friend’s problem statements (e.g., “Let’s talk about my problem now”). The global coding approach allowed coders to simultaneously take into account a variety of factors, including flow of conversation and friends’ responses. Inter-rater reliability was good (κ = .71).

Proportion score

Youth also were assigned self-focus proportion scores. The transcripts first were divided into thought units, logical divisions of speech that rely on contextual and syntactic clues such as pauses, changes in idea or thought, or another person’s speech (Leaper, Tennenbaum, & Shaffer, 1999; Strough & Berg, 2000). Reliability was good for identifying thought units (92% agreement). Next, coders decided whether each thought unit was problem-relevant (i.e., focusing on youth’s own or the friend’s problems) or problem-irrelevant (κ = .92). Last, all problem-relevant statements in which a youth spoke about his or her own problems (e.g., “I don’t know what to do about my grade”) were identified (κ = .90). Problem-relevant thought units in which youth spoke about their own problems were referred to as own-problem-statements.

The conversational self-focus proportion score then was computed for each youth. This score was the number of statements the youth made about his or her own problems (own-problem-statements) divided by the total number of statements both friends together made about their own problems (i.e., the denominator was the number of statements the youth made about his/her own problems plus the number of statements the friend made about his/her own problems). Proportion scores could range from 0 to 1. One dyad was dropped from analyses involving the proportion score as neither youth made any own-problem-statements. Note too that because each youth’s score was relative to the score of their friend (e.g., if Friend 1’s proportion score is .30, then Friend 2’s score is .70), the mean score for each dyad was .50 by design.

Responses to friends’ own-problem-statements

A last stage of coding was undertaken to examine how self-focused youth responded to their friends’ own-problem-statements. For these analyses, a subset of highly self-focused youth and a subset of average self-focused youth were selected for comparison. In order to select the high self-focus group, a composite self-focus score first was created by computing the mean of youths’ standardized global self-focus score and proportion self-focus score. Youth whose composite score was greater than one standard deviation above the mean were selected (n = 9)1. However, one of the highly self-focused youth had a friend who made only three own-problem-statements, offering the self-focused youth few opportunities to respond. Therefore, this youth was dropped from analyses, resulting in a high self-focus group of 8 youth (5 boys, 3 girls). A comparison group of 8 youth classified as average in self-focus also was chosen (4 boys, 4 girls). These youth had scores closest to the mean on the composite self-focus score (i.e., scores were within +/− .15 SD).

The first step in this phase of coding was to identify each time the friend of a youth in one of the subsamples produced a turn that included an own-problem-statement. Note that a turn began each time a youth began to speak and ended either when the other youth in the dyad spoke or when there was silence. A turn could include only one thought unit or many thought units. After identifying these turns, all of the thought units in the very next turn produced by the youth in the subsample were coded. In other words, we coded how the youth in the high and average self-focus groups responded to their friends’ own-problem-statements.

Specifically, each thought unit in a turn following the friends’ turn with the own-problem-statement (OPS) was coded as either: a) Distracting Own Experience, b) Changing Subject, c) Non-Distracting Own Experience, or d) Other. This coding system was based in part on previous systems used to code friends’ responses to one another (e.g., Leaper et al., 1999). Distracting Own Experience (D) thought units were those in which youth steered focus away from the friend to discuss a problem of their own. In the following example, the friend talks about a boy she likes who already has a girlfriend, and, in the next turn, the youth interrupts to switch the focus to her ex-boyfriend.

Friend: {It’s not fair}OPS…{he and his girlfriend are perfect for each other…}OPS

Youth: {You could have my ex-boyfriend.}D {No one wants him now}D …{like people I don’t even know, like (say), “Dude, I used to like him…}D

Changing Subject (CS) thought units involved a response on a completely different topic than the problem the friend was trying to discuss. In the following example2, the friend is discussing how he was disciplined in science class, and the youth changes the subject to discuss a peer he does not like.

Friend: {He got mad and sent me out}OPS {and then—}OPS

Youth: {I hate Tony.}CS

In contrast, Non-Distracting Own Experience (ND) thought units were those in which youth offered an example of when they experienced a similar problem but did not steer the focus away from the friend. In the following example, the friend is speaking about frustrations with her mother, and the youth offers her experience with her own mother.

Friend: {My mom says, “Blah, blah, blah, blah.”}OPS

Youth: {My mom uses those exact words too!}ND

Reliability was good for each code (Distracting Own Experience, κ = .77; Changing Subject, κ = .90; Non-Distracting Own Experience, κ = .73). Proportion scores for each of the three codes were computed by taking the number of turns in which the youth produced a thought unit representing a particular code (e.g., Changing Subject) divided by the total number of turns following a turn in which the friend produced at least one own-problem-statement (i.e., divided by the number of opportunities the youth had to respond to the friend’s own-problem-statements).

Results

Given that youth were nested within dyads, hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) was used. Thus, all parameter estimates are from two-level (i.e., individual and dyad) random coefficient models and were estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation technique in Proc Mixed in SAS.

Descriptive Statistics

Means and standard deviations for all variables are presented in Table 1. Global conversational self-focus scores indicated low to moderate levels on average. As mentioned previously, means for the conversational self-focus proportion score were .50 by design. The association between the global and proportion scores was positive and moderate indicating that, as expected, the indices were related but distinct. This correlation and correlations among all variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Study Variables for Whole Sample and Separately by Gender

| Whole Sample | Boys | Girls | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M (SD) | Range | N | M (SD) | Range | N | M (SD) | Range | t value | |

| Global self-focus | 60 | 1.92 (1.00) | 1.00–4.00 | 30 | 1.90 (.92) | 1.00–4.00 | 30 | 1.93 (1.08) | 1.00–4.00 | .13 |

| Self-focus proportion | 60 | .50 (.21) | .06–.94 | 30 | .50 (.24) | .06–.94 | 30 | .50 (.18) | .08–.92 | .00 |

| Depression | 60 | .29 (.21) | .04–.96 | 30 | .27 (.19) | .04–.81 | 30 | .31 (.22) | .04–.96 | .60 |

| Anxiety | 60 | 1.96 (.54) | 1.00–3.54 | 30 | 1.84 (.40) | 1.00–2.71 | 30 | 2.09 (.64) | 1.32–3.54 | 1.90† |

| Positive FQ (composite) |

60 | 3.04 (.61) | 1.67–4.00 | 30 | 2.80 (.60) | 1.67–3.93 | 30 | 3.29 (.52) | 2.07–4.00 | 3.04** |

| Companionship and recreation |

60 | 3.03 (.69) | 1.67–4.00 | 30 | 3.02 (.66) | 1.67–4.00 | 30 | 3.04 (.72) | 1.67–4.00 | .10 |

| Conflict resolution | 60 | 3.32 (.69) | 1.67–4.00 | 30 | 3.02 (.66) | 1.67–4.00 | 30 | 3.44 (.66) | 1.67–4.00 | 2.52* |

| Help and guidance | 60 | 3.09 (.70) | 1.67–4.00 | 30 | 2.96 (.71) | 1.67–4.00 | 30 | 3.23 (.67) | 1.67–4.00 | 1.51 |

| Intimacy | 60 | 2.80 (.90) | .67–4.00 | 30 | 2.26 (.87) | .67–4.00 | 30 | 3.34 (.53) | 2.33–4.00 | 5.46**** |

| Validation and caring | 60 | 3.05 (.84) | 1.33–4.00 | 30 | 2.73 (.88) | 1.33–4.00 | 30 | 3.37 (.68) | 1.67–4.00 | 2.74* |

| Rumination | 60 | 1.93 (.55) | 1.08–3.39 | 30 | 1.87 (.51) | 1.10–2.76 | 30 | 2.02 (.57) | 1.29–3.38 | 1.25 |

| Self-disclosure | 60 | 3.90 (.55) | 1.67–5.00 | 30 | 3.23 (.91) | 1.67–5.00 | 30 | 4.57 (.46) | 3.33–5.00 | 5.92**** |

Notes. p = .07

p < .05

p < .01

p < .0001.

t values are from multilevel analyses in which gender was used to predict each variable.

Descriptive statistics for internalizing symptoms were of particular interest due to the study’s focus on youth with elevated symptoms. Youth reported low to moderate levels on average. However, individual scores ranged from mild to more severe with a subset of youth experiencing symptoms that were likely clinically significant. In particular, 16% of youth reported above-average levels of depressive symptoms and 10% of youth reported above-average levels of anxiety symptoms as defined by the developers of the measures (Kovacs, 1992; Reynolds & Richmond, 1978).

Youth generally reported high levels of positive friendship quality, similar to past studies (e.g., Mounts, 2004; Rose, Carlson, & Waller, 2007). Like past research, youth also reported moderate levels of rumination and moderate to high levels of self-disclosure (e.g., Rose, 2002).

In order to test gender differences, a two-level random coefficient model in which gender was the predictor was tested for each variable. Means and standard deviations by gender are presented in Table 1. The model for the global self-focus score found boys and girls to be similar. Gender differences in the proportion score could not be tested because the mean score for each dyad was .50 by design. Although girls reported slightly higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms than boys, the gender effect for depressive symptoms was not significant and was marginal for anxiety symptoms. In terms of friendship quality, a gender difference in favor of girls was observed for the composite positive friendship quality score. Gender differences favoring girls also were observed for the subscales of conflict resolution, intimate exchange, and validation and caring. Girls and boys did not differ in terms of companionship and recreation or help and guidance. In terms of rumination, girls and boys did not differ; however, girls reported significantly higher levels of self-disclosure.

Internalizing Symptoms and Positive Friendship Quality

Analyses in this subsection tested the relations between internalizing symptoms and positive friendship quality. Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine if depressive and anxiety symptoms should be examined separately or whether a composite internalizing symptoms score could be created. The same pattern of results emerged for associations of depressive and anxiety symptoms with other study variables. Additionally, as in past research (e.g., Brady & Kendall, 1992), depressive and anxiety symptoms were highly correlated (r = .78, p < .0001). Therefore, a composite score was created for each youth (mean of standardized depressive and anxiety symptoms scores).

First, a two-level random coefficient model was tested in which the composite positive friendship quality score was the dependent variable and the internalizing symptoms composite was the predictor. Parallel models were tested for each positive friendship quality subscale. Although the direction of the relation indicated that internalizing symptoms were related to lower friend-reported positive friendship quality using the composite score, the effect was not significant (standardized parameter estimate = −.14, t value = 1.08). Likewise, although the effects for the positive friendship quality subscales generally were in the expected direction, the effects did not reach significance (mean standardized parameter estimate = −.11, ranged from −.21 to .04, t values ranged from .34 to 1.57).

Internalizing Symptoms and Conversational Self-Focus

Analyses next examined relations of internalizing symptoms with observed conversational self-focus. A two-level random coefficient model was tested for the global self-focus score and a separate two-level random coefficient model was tested for the self-focus proportion score. In each model, the internalizing composite was the predictor and self-focus was the dependent variable. Parameter estimates and t values are presented in Table 3. As hypothesized, internalizing symptoms significantly predicted greater global and proportion scores.

Table 3.

Summary of Multilevel Modeling Analyses Predicting Conversational Self-Focus from Internalizing Symptoms

| Global self-focus | Self-focus proportion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | t | PE | t | |

| Internalizing symptoms (whole sample) | .36 | 2.79** | .30 | 2.29* |

| Boys | .53 | 3.13** | ||

| Girls | .14 | .73 | ||

Notes. p < .05

p < .01.

PE = standardized parameter estimate.

Analyses also tested whether these relations were moderated by gender. A model was tested in which global scores were predicted from internalizing symptoms, gender, and the interaction. The model was tested again for proportion scores. The interaction between gender and internalizing symptoms in predicting the self-focus proportion score was significant, t(27) = 2.26, p < .05. Analyses conducted separately by gender suggested the relation between internalizing symptoms and the proportion score was significant for boys. For girls, the effect was in the predicted direction but did not reach significance (see Table 3).

Conversational Self-Focus and Positive Friendship Quality

Analyses then tested the hypothesis that conversational self-focus would be related to friends perceiving the friendship as lower in positive quality. First, a two-level random coefficient model was tested in which the composite positive friendship quality score was the dependent variable and the global self-focus score was the predictor. The analysis was repeated using the proportion self-focus score. The parameter estimates and t values from these analyses are presented in Table 4. The self-focus proportion score significantly predicted lower friend-reported positive friendship quality. The effect for the global self-focus score was in the predicted direction but did not reach significance. The analyses then were performed again for each of the positive friendship quality subscales (see Table 4). The self-focus proportion score significantly predicted lower friend-reported help and guidance. The global self-focus score also was marginally related to lower friend-reported help and guidance. Neither the global nor proportion score was significantly related to companionship and recreation, conflict resolution, intimacy, or validation and caring.

Table 4.

Summary of Multilevel Modeling Analyses Predicting Positive Friendship Quality from Conversational Self-Focus

| Positive Friendship Quality (composite) |

Positive Friendship Quality Subscales | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Companionship/ Recreation |

Conflict Resolution |

Help/ Guidance |

Intimacy | Validation/ Caring |

||||||||

| PE | t | PE | t | PE | t | PE | t | PE | t | PE | t | |

| Global self-focus | −.14 | 1.17 | −.04 | .40 | −.19 | 1.46 | −.24 | 1.92† | .03 | .28 | −.13 | 1.14 |

| Self-focus proportion | −.20 | 2.03* | −.09 | .98 | −.16 | 1.25 | −.25 | 2.22* | −.11 | 1.32 | −.17 | 1.78 |

Notes. p = .06

p < .05.

PE = standardized parameter estimate.

Gender differences in the relations of both self-focus indices with the composite positive friendship quality score as well as specific aspects of friend-reported positive friendship quality also were examined by testing additional models that included interactions with gender. Of all the gender interactions tested, none were significant.

Self-Focused Youths’ Responses to Friends’ Statements About Their Own Problems

Analyses then tested whether highly self-focused youth differed from average youth in their responses to friends’ own-problem-statements. Because the sample sizes of subgroups were small and the distributions were not normal, non-parametric tests were conducted to examine group differences in the Distracting Own Experience, Changing Subject, and Non-Distracting Own Experience proportion scores. In particular, the Mann Whitney U Test was conducted to compare the high and average self-focus groups. Table 7 presents the subsample means for each score and Mann Whitney U tests. Although non-parametric tests were most appropriate, for comparison purposes, t tests were conducted. The same pattern of significant effects emerged (t values not presented).

Table 7.

Self-Focused and Average Youths’ Responses to Friends’ Talk About Their Own Problems

| High Self-Focus | Average Self-Focus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | Mann Whitney U |

Effect size |

|

| Distracting own experience | .10 (.08) | .00–.20 | .02 (.05) | .00–.13 | 14.00* | .32 |

| Changing subject | .08 (.07) | .00–.20 | .01 (.03) | .00–.04 | 10.00* | .32 |

| Non-distracting own experience | .21 (.23) | .00–.56 | .13 (.10) | .02–.33 | 31.00 | .20 |

| Distracting own experience + | ||||||

| Changing subject | .18 (.15) | .00–.40 | .04 (.06) | .00–.19 | 11.00* | .44 |

| Distracting own experience + | ||||||

| Changing subject + | ||||||

| Non-distracting | ||||||

| own experience | .39 (.18) | .17–.67 | .17 (.12) | .02–.50 | 11.00* | .56 |

Note. p < .05.

In terms of the Distracting Own Experience response, average youth almost never engaged in this behavior (they produced these thought units in response to only 2% of the turns in which their friend produced an own-problem-statement). In contrast, this response was in the repertoire of highly self-focused youth. Highly self-focused youth responded with a Distracting Own Experience thought unit in response to 10% of the turns in which their friend produced an own-problem-statement. This difference was significant. Similarly, the Changing Subject response was nearly absent in average self-focused youth (proportion score was 1%). However, self-focused youth abruptly changed the subject in response to 8% of their friend’s turns that included an own-problem-statement. Again, this difference was significant. Interestingly, the groups did not differ in terms of the Non-Distracting Own Experience proportion score (21% for the high self-focus group and 13% for the average group).

Based on the previous set of results, it was of interest to examine group differences if particular codes were combined. First, we formed new proportion scores by collapsing across the two potentially most off-putting responses—Distracting Own Experience and Changing Subject. Self-focused youth responded to 18% of their friends’ own-problem-statements with either a Distracting Own Experience or a Changing Subject response. In contrast, the proportion scores for average youth remained low, at 4%. Finally, we combined all three codes to examine group differences in the proportion of the time youth responded to friends’ problems either by talking about their own problems or changing the subject. Average youths’ proportion scores were 17%, and the scores of self-focused youth were significantly higher at 39%. This means that close to 40% of the time friends had a turn in which they spoke about their own problem, self-focused youth responded with a turn in which they talked about themselves or changed the subject completely.

Additional Construct Validation: Associations with Rumination and Self-Disclosure

Finally, for construct validation purposes, relations among self-focus, rumination, self-disclosure, internalizing symptoms, and friendship quality also were examined. First, two-level random coefficient models were tested in which rumination was a predictor of each of the self-focus scores, internalizing symptoms, and friendship quality (see Table 5 and Table 6). As predicted, rumination predicted greater global and proportion self-focus scores. Also consistent with hypotheses, rumination, like self-focus, was significantly related to internalizing symptoms but not positive friendship quality (composite or subscales).

Table 5.

Summary of Multilevel Modeling Analyses Predicting Conversational Self-Focus from Rumination and Self-Disclosure

| Global self-focus | Self-focus proportion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | t | PE | t | |

| Rumination | .29 | 2.31* | .39 | 3.16** |

| Self-Disclosure | −.16 | 1.29 | −.02 | .17 |

Notes. p < .05

p < .01.

PE = standardized parameter estimate.

Table 6.

Summary of Multilevel Modeling Analyses Predicting Internalizing Symptoms and Positive Friendship Quality from Rumination and Self-Disclosure

| Internalizing Symptoms |

Positive Friendship Quality (composite) |

Positive Friendship Quality Subscales | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Companionship/ Recreation |

Conflict Resolution |

Help/ Guidance |

Intimacy | Validation/ Caring |

||||||||||

| PE | t | PE | t | PE | t | PE | t | PE | t | PE | t | PE | t | |

| Rumination | .64 | 5.91**** | −.09 | .74 | −.02 | .16 | .03 | .24 | −.19 | 1.52 | .01 | .09 | −.08 | .68 |

| Self-disclosure | −.03 | .37 | .41 | 3.49* | .03 | .19 | .29 | 2.34* | .33 | 2.73* | .54 | 5.04**** | .28 | 2.16* |

Notes. p < .05

p < .0001.

PE = standardized parameter estimate.

Next, two-level random coefficient models were tested in which self-disclosure was the predictor of each of the self-focus scores, internalizing symptoms, and friendship quality (see Table 5 and Table 6). Unexpectedly, self-disclosure was not related to either the global self-focus score or the self-focus proportion score. However, as predicted, youths’ self-disclosure did predict increased friend-reported positive friendship quality using the composite score. In terms of the subscales, self-disclosure was significantly related to friends’ reports that the relationship was high in conflict resolution, help and guidance, intimacy, and validation and caring. Self-disclosure was not significantly related to friends’ reports of companionship and recreation. Also as predicted, self-disclosure was unrelated to internalizing symptoms.

Finally, all relations described in this section involving rumination or self-disclosure were tested for moderation by gender. Only the relation between rumination and conflict resolution was significantly moderated by gender, t(28) = .53, p < .05. However, when the relation was examined within each gender, neither relation was significant.

Discussion

Interpersonal theories of depression (e.g., Coyne, 1976a), have highlighted the importance of understanding the ways in which the behaviors of individuals with internalizing symptoms may be aversive and lead to rejection (see Joiner et al., 1999). However, only partial progress has been made in learning about these problematic interpersonal behaviors. Research has been especially limited in regards to adolescents’ friendships. Although recent studies indicate that adolescents with internalizing symptoms tend to exhibit excessive reassurance-seeking and negative feedback-seeking in friendships (Borelli & Prinstein, 2006; Prinstein et al., 2005), little else was known about their behavior. The current research contributes to the literature by identifying conversational self-focus as an interpersonal behavior exhibited in adolescent friendships that is related to internalizing symptoms and to friends’ perceptions that the relationship is lower in quality. The study further provided insight into how self-focused youth redirect conversations to themselves, namely, by responding to friends’ problem talk by discussing their own problems in distracting ways and by changing the subject. Additionally, results indicated that self-focus was not identical to either rumination or self-disclosure.

Conversational Self-Focus, Internalizing Symptoms, and Positive Friendship Quality

Results supported the hypothesis that youth with elevated internalizing symptoms would exhibit conversational self-focus. Few interpersonal behaviors more typical of youth with internalizing symptoms have been identified within adolescent friendships. Thus the findings extend past research by identifying one such behavioral style. It is of note that the association between the self-focus proportion score and internalizing symptoms was moderated by gender and reached significance for boys only. However, the direction of effect for girls was in the expected direction and may not have reached significance due to the small within-gender samples. Larger studies are needed to determine whether this gender moderation effect is replicable.

The results also suggested that self-focused behavior may be damaging to friendships. The self-focus proportion score was related to friends reporting that the relationship was relatively low in overall positive quality. The effect for the global self-focus score was in the same direction but did not reach significance. In regards to the friendship quality subscales, friends of conversationally self-focused youth reported that they received less help from these youth (with a significant effect for the self-focus proportion score and a marginal effect for the global score).

Notably, it is conceptually meaningful that a relation emerged only for helping and not other friendship qualities. That is, it makes sense that friends of self-focused youth may have problems that are rarely discussed and/or actively avoided. If youth perceive themselves as unable to discuss problems with self-focused friends or that their problems do not receive equal attention within the friendship, these youth are likely to perceive the friendship as lower in help and guidance. Moreover, the finding is noteworthy given the methodology employed. Given that only a small sample of youths’ conversational style was observed, it is noteworthy that a significant relation emerged between these observations and friends’ more global reports of helping in friendship.

Although the direction of effect was not assessed in the current study, we have suggested that the friends of self-focused youth may grow frustrated by repeatedly thwarted attempts to interact reciprocally in conversations and, thus, perceive the relationship as lower in quality. However, lower-quality friendships also may contribute to self-focus. Youth in these friendships may not be getting their needs met and feel they must push their friends to meet their needs by dominating conversations about problems. It also may be that youth in low-quality friendships do not value these relationships as much as youth in higher-quality friendships or do not care as much about what their friend thinks of their behavior and so may be more likely to engage in potentially aversive behaviors such as self-focus.

Regardless of whether self-focus precedes friendship problems or vice versa, once self-focus is present in friendships, it is clear why it might be aversive. A content analysis of how self-focused youth respond to friends’ attempts to discuss their own problems provides some insight into how self-focused youth redirect and dominate conversations and illustrates why friends may find the behavior aversive. In particular, compared to average youth, self-focused youth were more likely to respond to friends’ statements about problems by talking about their own problems in ways that were only tangentially related to the friends’ problems and by changing the subject to an entirely different topic. It is reasonable to suspect that these behaviors are perceived by friends as extremely unsupportive and off-putting.

For instance, consider this description of one highly self-focused youth with elevated internalizing symptoms who was especially likely to respond to friends’ problem talk by changing the subject and by talking about her own problems in distracting ways. She briefly listened to her friend discuss a body image problem but then changed the subject, dominating the first half of the interaction by talking about a problem she had with her boyfriend. At that point, she invited her friend to discuss the friend’s problem once again. However, after the friend spoke only one sentence describing problems she had with her boyfriend, the self-focused youth interrupted by stating “Yeah, me and [my ex-boyfriend] were like that when we first started going out…” and then continued to discuss her own romantic troubles in a way that was distracting from the friend’s discussion. As another example, when a friend of another self-focused youth discussed money troubles, he was interrupted by the self-focused youth’s statement “I’m going to be the same way, like, my parents won’t give me money for gas,” which then led into his talking about his own money problems in a way that did not relate to the friend’s concerns. The self-focused youth continued for several minutes and never revisited the friend’s initial money concerns.

We want to be clear that the implication here is not that any introduction of one’s own experiences when talking to a friend about their problems should be considered self-focused or is expected to be aversive. In fact, other results indicated that self-focused youth and average youth did not differ in their likelihood of responding to friends’ problem talk by offering their own experiences in ways that were directly related to the friends’ problem and did not draw attention away from the friend. Indeed, it is plausible that friends view this type of response as supportive and as a signal that their friend is engaged.

In addition to the idea that friends may respond negatively to self-focused behavior because it feels unsupportive, it also is possible that negative affect displayed by self-focused youth contributes to these youth being viewed negatively. Although this was not something we coded, our sense was that self-focused youth expressed a high degree of negative affect during interactions with friends. Perhaps this is not surprising given that they persistently turned conversations to focus on their own worries and concerns. Exposure to this negativity may be perceived by friends as unenjoyable, unpleasant, and unfulfilling, which may lead them to perceive self-focused youth more negatively.

Finally, the fact that internalizing symptoms were linked with self-focus, which was linked with friends’ reports of lower friendship quality, suggests a relation between internalizing symptoms and friendship quality. However, this relation was not found in the current study. As discussed, past research is mixed regarding the concurrent link between internalizing symptoms and friendship difficulties perhaps because internalizing symptoms take their toll over time. Longitudinal data with the current sample might have revealed greater damaging effects of internalizing symptoms over the following weeks or months. This would fit with the one study of friendship stability indicating that depressed youths’ friendships were especially likely to end during an eleven-month period (Prinstein et al., 2005). As another possibility, given the relatively low participation rate, it may be that the current sample was better-adjusted than the broader community. Thus, perhaps few youth had symptoms severe enough to impact their friendship quality.

Evidence In Support of Construct Validation

In addition to demonstrating links with internalizing symptoms and friendship quality, the study provided initial evidence of construct validation for conversational self-focus. As predicted the construct was related to rumination, a variant of self-focused attention. As expected, rumination was significantly associated with internalizing symptoms. However, rumination was not related to positive friendship quality. This finding is important because it suggests that rumination and conversational self-focus are indeed distinct constructs. That is, rumination alone may not be particularly damaging to friendships; however rumination about the self in behavioral form (i.e., conversational self-focus) appears to be associated with friendship difficulties.

Also as expected, self-disclosure was unrelated to internalizing symptoms, suggesting that it is the variant of normative self-disclosure, conversational self-focus, that is particular to youth with internalizing symptoms. Additionally, as expected, self-disclosure was related to positive friendship quality, whereas self-focus was related to friendship problems. Again, this suggests that deviating from the normative, give-and-take of reciprocal self-disclosure may be damaging to friendships.

Surprisingly, significant associations between self-reported self-disclosure and observed self-focus did not emerge. This null result may have occurred because, as discussed, it is possible for a youth to be very high in self-disclosure but low in self-focus. Nevertheless, future research should examine this relation in larger samples. Also, it is worth noting that, although the relation between self-focus and self-disclosure was not significant, results supported all other hypotheses regarding relations among self-focus, internalizing symptoms, friendship quality, rumination, and self-disclosure (see Figure 1).

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Although the relations proposed between self-focus, internalizing symptoms, and friendship quality are intuitive and fit with theory and past research, finding significant relations in the current research is nevertheless noteworthy as it provided a rigorous test of study hypotheses. First, because self-focus was assessed with observations, internalizing symptoms were assessed with self reports, and friendship quality was assessed with friend reports, the relations could not have been inflated due to shared method variance. Notably, past research examining relations of problematic interpersonal behaviors in adolescent friendships with internalizing symptoms relied on self-reports of both disclosure processes and internalizing symptoms (Borelli & Prinstein, 2006; Prinstein et al., 2005). Also, given the nature of laboratory-based observational studies, only small samples of behavior could be observed. Therefore, it is particularly significant that relations with internalizing symptoms and with friendship quality emerged. Finding significant effects with the relatively modest sample of the current study also suggests that the associations identified may be particularly robust.

However, there also were limitations. As discussed, the direction of the effects identified is unclear because the design was cross-sectional. It will be important to evaluate the direction of effects in longitudinal research before making claims that internalizing symptoms precede self-focus. In the current study, friends of self-focused youth reported some problems in their friendships. A prospective study also could test the prediction that accumulated self-focused behavior (perhaps in addition to other behaviors associated with internalizing symptoms) leads to decreased friendship quality, avoidance, or even rejection by friends over time.

Longitudinal studies also could consider the effects on youth of having self-focused friends. These youth likely are unable to reap the benefits of normative self-disclosure in friendship, which could contribute to greater negative affect or internalizing symptoms over time. Conversational self-focus might be one process that explains depression contagion (i.e., friends of depressed adolescents becoming more depressed over time; Stevens & Prinstein, 2005).

Additionally, it would be useful for future research to replicate the current findings in a larger sample that is more varied in terms of race and ethnicity. Further, a community sample was used, precluding comparisons of community youth with clinical samples. This could be a particular concern for the current study given that the participation rate was low and it is possible that youth who chose to participate were relatively well-adjusted. Future research should investigate the nature and correlates of self-focus for youth with diagnosable levels of disorder. For instance, youth with severe clinical depression may experience such extreme withdrawal, psychomotor retardation, and hopelessness that they do not engage in self-focused disclosure with friends. On the other hand, youth with diagnosable levels of anxiety may experience such extreme agitation and desperation resulting from high levels of rumination and physiological arousal that they continue to engage in self-focus.

Finally, future research should consider additional contexts in which individuals might self-focus. The current study examined one context—problem-focused conversations. As mentioned, though, it is possible to self-focus on positive or even neutral topics as well. Perhaps individuals who self-focus on perceived life successes in a self-aggrandizing manner or who self-focus on mundane details of their lives are similarly aversive to conversation partners but do not experience internalizing distress to the same degree as those who focus on worries and concerns. This would not necessarily mean, though, that individuals who self-focus in other ways are psychologically healthy. For example, self-focus in other contexts (e.g., in regards to perceived successes) may be related to other forms of maladjustment (e.g., narcissistic personality disorder features).

Applied Implications

Despite the need for replication and additional research, the applied value of the current research potentially is noteworthy. Unfortunately, with few exceptions (e.g., Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 1998), interventions with youth rarely consider the peer context and even more rarely address specific dyadic friendships. By identifying aversive behaviors displayed by youth with depressive and anxiety symptoms within the context of friendships, the current research has the potential to inform intervention efforts. In particular, interventions may aim to educate youth about their potential for self-focusing during conversations with friends about problems and offer alternate strategies for coping with distress such as problem-solving or engaging in pleasant, distracting activities.

Acknowledgments

Data collection for this research was supported by a Research Council Grant awarded to Amanda J. Rose from the University of Missouri. During the preparation of this paper, Amanda J. Rose was partially supported by NIMH grant R01 MH 073590.

We also thank Wendy Carlson for her assistance with data collection and coding.

Footnotes

Although a composite self-focus score was used to select the high self-focused group, it was most appropriate to use the global self-focus score and the proportion self-focus score separately in the primary analyses (e.g., examining associations with internalizing symptoms and friendship quality) given that these scores were only moderately correlated (r = .43).

Names have been changed.

References

- Bell-Dolan DJ, Last CG, Strauss CC. Symptoms of anxiety disorders in normal children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:759–765. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199009000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Friendship quality and social development. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002;11:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Borelli JL, Prinstein MJ. Reciprocal, longitudinal associations among adolescents’ negative feedback-seeking, depressive symptoms, and peer relations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady EU, Kendall PC. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:244–255. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Turgeon L, Poulin F. Assessing aggressive and depressed children's social relations with classmates and friends: A matter of perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:609–624. doi: 10.1023/a:1020863730902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Prager K. Patterns and functions of self-disclosure during childhood and adolescence. In: Rotenberg KJ, editor. Disclosure processes in children and adolescents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 10–56. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Schier MF. On the self-regulation of behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Ziv Y, Mehta TG, Feeney BC. Feedback seeking in children and adolescents: associations with self-perceptions, attachment representations, and depression. Child Development. 2003;74:612–628. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek JM, Briggs SR. Shyness as a personality trait. In: Crozier WR, editor. Shyness and embarrassment: Perspectives from social psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 315–337. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA. Relation of social and academic competence to depression in childhood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:422–429. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry. 1976a;39:28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976b;85:186–193. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Thinking interactionally about depression: A radical restatement. In: Joiner T, Coyne J, editors. The interactional nature of depression. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1991. pp. 365–392. [Google Scholar]

- Cozby PC. Self-disclosure: A literature review. Psychological Bulletin. 1973;79:73–91. doi: 10.1037/h0033950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M, Urberg KA. Friendship and adjustment among adolescents. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2004;88:68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derlega VJ, Metts S, Petronio S, Margulis ST. Self-disclosure. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, Wicklund R. A theory of objective self-awareness. New York: Academic Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham K, Stevenson-Hinde J. Shyness, friendship quality, and adjustment during middle childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:787–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Hammen C. Psychological aspects of depression: Toward a cognitive-interpersonal integration. London: Wiley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JC, Deemer HN. Excessive reassurance-seeking as self-regulatory perseveration: Implications for explaining the relation between depression and illness behavior. Psychological Inquiry. 1999;10:293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Rudolph KD. Childhood mood disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child psychopathology. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2003. pp. 233–278. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Borduin CM, Rowland MD, Cunningham PB. Multisystemic treatment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Perceived peer context and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10:391–415. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE. Attentional nonspecificity in depressive and generalized anxious affective states. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990a;14:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE. Self-focused attention in clinical disorders: Review and a conceptual model. Psychological Bulletin. 1990b;107:156–176. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Anderson E. Interpersonal skills deficits and depression in college students: A sequential analysis of the timing of self-disclosure. Behavior Therapy. 1982;13:271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE., Jr The price of soliciting and receiving negative feedback: Self-verification theory as a vulnerability to depression theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:364–372. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Alfano MS, Metalsky GI. When depression breeds contempt: Reassurance seeking, self-esteem, and rejection of depressed college students by their roommates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:165–173. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Coyne JC, Blalock J. On the interpersonal nature of depression: Overview and synthesis. In: Joiner TE, Coyne JC, editors. The interactional nature of depression. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Katz J, Lew AS. Self-verification and depression among youth psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:608–618. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Metalsky GI. Excessive reassurance seeking: Delineating a risk factor involved in the development of depressive symptoms. Psychological Science. 2001;12:371–378. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Schmidt NB. Reassurance-seeking predicts depressive but not anxious reactions to acute stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:533–537. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesner J. Depressive symptoms in early adolescence: Their relations with classroom problem behavior and peer status. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12:463–478. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski RM, Leary MR. Strategic self-presentation and the avoidance of aversive events: Antecedents and consequences of self-enhancement and self-depreciation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1990;26:322–336. [Google Scholar]

- LaGreca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaper C, Tenenbaum HR, Shaffer TG. Communication patterns of African American girls and boys from low-income, urban backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1489–1503. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Solomon A, Seeley JR, Zeiss A. Clinical implications of “subthreshold” depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:345–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR. The lay assessment of subclinical depression in daily life. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:340–345. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LC, Kenny DA. Reciprocity of self-disclosure at the individual and dyadic levels: A social relations analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:713–719. [Google Scholar]

- Mor N, Winquist J. Self-focused attention and negative affect: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:638–662. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounts NS. Adolescents’ perceptions of parental management of peer relationships in an ethnically diverse sample. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:446–467. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS, Seligman ME. Learned helplessness in children: A longitudinal study of depression, achievement, and explanatory style. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:435–442. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.2.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and distress following a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:105–121. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panak WF, Garber J. Role of aggression, rejection, and attributions in the prediction of depression in children. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:145–165. [Google Scholar]

- Papini DR, Farmer FF, Clark SM, Micka JC, Barnett JK. Early adolescent age and gender differences in patterns of emotional self-disclosure to parents and friends. Adolescence. 1990;25:959–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit J, Joiner TE., Jr Negative-feedback seeking leads to depressive symptom increases under conditions of stress. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001;23:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ. Moderators of peer contagion: A longitudinal examination of depression socialization between adolescents and their best friends. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:159–170. doi: 10.1080/15374410701274934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Borelli JL, Cheah CSL, Simon VA, Aikins JW. Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:676–688. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczyski T, Greenberg J. Evidence for a depressive self-focusing style. Journal of Research in Personality. 1986;20:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications anddata analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Frost AK, Pakiz B. Changing faces: Correlates of depressive symptoms in late adolescence. Family & Community Health. 1991;14:52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. What I Think and What I Feel: A revised measure of children’s manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:271–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ. Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development. 2002;73:1830–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Asher SR. Children’s strategies and goals in response to help-giving and help-seeking tasks within a friendship. Child Development. 2004;75:749–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Carlson W, Waller EM. Prospective associations of co-rumination with friendship and emotional adjustment: Considering the socioemotional trade-offs of co-rumination. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1019–1031. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB. Social withdrawal and anxiety. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. New York: Oxford; 2001. pp. 407–434. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Asher SR. Adaptation and maladaptation in the peer system: Developmental processes and outcomes. In: Sameroff AJ, Lewis M, Miller SM, editors. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. 2nd ed. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 2000. pp. 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D. Interpersonal functioning and depressive symptoms in childhood: Addressing the issues of specificity and comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:355–371. doi: 10.1007/BF02168079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Ladd G, Dinella L. Gender differences in the interpersonal consequences of early-onset depressive symptoms. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2007;53:461–488. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens EA, Prinstein MJ. Peer contagion of depressogenic attributional styles among adolescents: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:25–37. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-0931-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss CC, Frame CL, Forehand R. Psychosocial impairment associated with anxiety in children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1987;16:235–239. [Google Scholar]

- Strough J, Berg CA. The role of goals in mediating dyad gender differences in high and low involvement conversational exchanges. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:117–125. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HS. The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Vangelisti AL, Knapp ML, Daly JA. Conversational narcissism. Communication Monographs. 1990;57:251–274. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RS. The provisions of social relationships. In: Rubin Z, editor. Doing untoothers. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1974. pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- West C, Zimmerman DH. Gender, language, and discourse. In: van Dijk TA, editor. Handbook of discourse analysis: Vol. 4. London: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 103–124. [Google Scholar]