Abstract

Background

Failure of antiretroviral therapy may result from the selection of pre-existing, drug-resistant HIV-1 variants, but the frequency and type of such variants have not been defined.

Objective

We used single genome sequencing (SGS) to characterize the frequency of polymorphism at drug resistance sites in protease (PR) and reverse transcriptase (RT) in plasma samples from antiretroviral naive individuals.

Methods

A total of 2229 pro-pol sequences in 79 plasma samples from 30 patients were analyzed by SGS. A mean of 28 single genome sequences was obtained from each sample. The frequency of mutations at all PR and RT sites was compared to those associated with drug resistance.

Results

We detected polymorphism at one or more drug resistance sites in 27 of 30 (90%) patients. Polymorphism at positions 179 and 215 of RT was most common, both occurring in 23% of patients. Most (68%) of other drug resistance sites were polymorphic with an average of 3.2% of genomes per sample containing at least one variant from wild type. Seven drug resistance sites were polymorphic in more than 1% of genomes: PR position 33; RT positions 69, 98, 118, 179, 210, and 215. Although frequencies of synonymous polymorphism were similar at resistance and nonresistance sites, nonsynonymous polymorphism were significantly less common at drug resistance sites, implying stronger purifying selection at these positions.

Conclusions

HIV-1 variants that are polymorphic at drug resistance sites pre-exist frequently as minor species in antiretroviral naive individuals. Standard genotype techniques have grossly underestimated their frequency.

Keywords: drug resistance polymorphisms, drug resistance, minority drug-resistant variants, pro-pol diversity, single genome sequencing (SGS), treatment-naive patients

Introduction

The emergence of resistance to antiretroviral drugs is a major obstacle to their long-term efficacy. Minor populations of drug-resistant variants present before therapy have been hypothesized to be an important cause of treatment failure [1,2]. To date, the frequency and type of such mutants have not been well defined in vivo. Theoretical considerations predict that the frequency of variants in a large replicating virus population will be determined by a number of factors, including their mutation rate and selection coefficient, and the size of the replicating population [3]. Comparison of the frequencies of nonsynonymous changes at drug resistance sites should therefore provide insight into the relative selective forces acting on the corresponding positions in protease (PR) and reverse transcriptase (RT). In the present study, we used single-genome sequencing (SGS) to assess the frequency, diversity and linkage of mutations at drug resistance sites in antiretroviral naive, HIV-1-infected individuals, compared to the frequency of mutations at nondrug resistance sites [4].

Materials and methods

Plasma samples were obtained from 30 patients attending the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Critical Care Medical Department of National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, Maryland, or enrolled in the AIEDRP study sponsored by NIAID and obtained from Joe Margolick at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland. The study was approved by the institutional review board of NIAID, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, and all individuals provided written informed consent. Additional patient samples with evidence of transmitted drug resistance (a major drug resistance mutation in the majority of genomes) were eliminated from the study.

Viral RNA from plasma containing 5000–10 000 copies of HIV-1 RNA was extracted and used for cDNA synthesis as previously described [4,5]. To obtain PCR products for SGS, the cDNA was diluted until approximately 30% of the PCR reactions yielded DNA product. cDNA was added to the PCR mix containing 2 mmol/l MgCl2, 0.04 units Invitrogen Platinum Taq HiFi and 200 nmol/1 primers: 1849+ (5′-GATGACAGCATGTCAGGGAG-3′), and 3500− (5′-CTATTAAGTATTTTGATGGGTCATAA-3′). Each PCR product was subsequently used as template for nested PCR with primers 1870+ (5′-GAGTTTTGGCTGAGGCAATGAG-3′) and 3410− (5′-CAGTTAGTGGTATTACTTCTGTTAGTGCTT-3′) producing a 1.5 kb amplicon containing the p6 region of gag, pro and the first 950 nt of pol. Positive PCR reactions were sequenced. The quality sequences from each plasma sample were aligned and compared to the HIV-1 subtype B consensus sequence using Clustal W software [6,7]. To perform standard ‘population’ genotype analyses, cDNA was generated as described above but was not diluted before PCR amplification and sequencing.

All sequences were analyzed for polymorphism at sites associated with drug resistance using the HIVseq Program available through the Stanford University HIV Drug Resistance Database (class I–IV definitions). Polymorphism was defined as any change from the subtype B consensus sequence (http://hivdb.stanford.edu). Frequency estimates were normalized to account for variations in the number of sequences obtained per plasma sample. We obtained a mean of 28 genomes per patient sample. Analyses of synonymous versus nonsynonymous mutations were performed using a software program written by Gary Smythers, PhD of Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC), Frederick, Maryland (details available upon request). Measurements of genetic diversity were calculated with a software program based on the average pairwise distance model. The duration of infection was determined in 20 of 31 patients by the onset of symptoms and a nonreactive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or negative western blot with detectable HIV-1 RNA. Longitudinal samples were available for up to 5 years from recently infected patients. The minimum duration of infection was used for chronically infected patients and was determined by the date of diagnosis and the patient exposure history.

Results

A total of 2229 sequences was obtained and analyzed from 79 plasma samples from 30 patients. Twenty-nine of the patients were male. The median [interquartile range (IQR)] age was 35 (29–38), CD4 cell count was 415 cells/μl (298–548), HIV-1 RNA was 46 490 copies/ml (16 230–204 170), and duration of infection was 183 days (71–592). First, we calculated the frequency of polymorphism at drug resistance sites and nonresistance sites. In PR, the frequency of nonsynonymous polymorphism at drug resistance sites was 32-fold lower than at nonresistance sites. In RT, the frequency of nonsynonymous polymorphism at drug resistance sites was two-fold lower than at nonresistance sites. The differences in the frequency of polymorphism between resistance and nonresistance sites were statistically significant (P =6 × 10−25 in PR; P =0.01 in RT). Highly polymorphic nonresistance sites (≥25% frequency) were codons 12, 35, 36, 37, 41, 62, 63, 77 and 93 in PR and codons 35, 83, 122, 123, 135, 200, and 211 in RT.

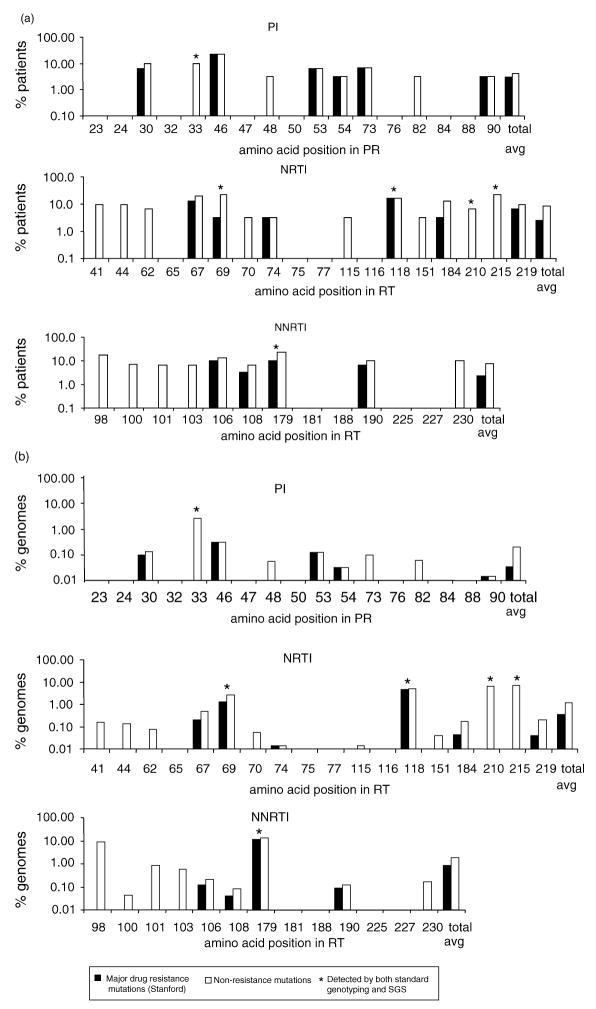

To characterize HIV-1 polymorphism at sites associated with drug resistance, we plotted the frequency of nonsynonymous changes at each drug resistance site by drug class (Fig. 1). Polymorphism at drug resistance sites was more prevalent in RT (23 polymorphic of 31 total sites) than in PR (nine of 17). However, most of the variant positions in PR contained changes known to confer drug resistance (six of nine). In RT, fewer of the substitutions were known to confer drug resistance (10 of 23). Overall, sequences in 45% of patients were polymorphic at one or more sites associated with PI resistance, 68% at one or more sites associated with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) resistance, and 66% at one or more sites associated with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) resistance. Positions 179 and 215 in RT were most frequently polymorphic, both occurring in 23% of patients (Fig. 1a). In total, 90% of the anti-retroviral naive patients studied had at least one non-synonymous change from wild-type at a drug resistance site, and 56% had at least one change known to confer drug resistance.

Fig. 1. Frequency of nonsynonymous polymorphism at drug resistance sites by drug class.

Proportion of patients (a) and genomes (b) with polymorphism at protease inhibitor (PI), nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) drug resistance sites as detected by single genome sequencing (SGS). The numbers on the x-axis represent the codon positions in protease (PR) or reverse transcriptase (RT). The white bars represent the frequency of patients (a) or genomes (b) with any nonsynonymous change at the designated codon (number on the x-axis) in PR or RT. The black bars represent the frequency of mutations at the designated codon that are defined to confer drug resistance. Codon positions without bars were invariant. The asterisks indicate mutations that were detected by both standard genotyping and SGS. The rightmost pairs of bars show the average values over all drug resistance sites. The data in (b) were normalized for the number of single sequences obtained per patient sample.

We also determined the percentage of viral genomes polymorphic at drug resistance sites, averaged over all genomes, and plotted them by drug class (Fig. 1b). The cumulative frequency of nonsynonymous polymorphism at drug resistance sites was 0.2% in PR and 1.5% in RT. Of these, 0.03% in PR and 0.61% in RT were mutations known to confer drug resistance. Overall, known drug resistance mutations were detected in 350 of the 2229 genomes. Standard population genotype analyses identified polymorphism in only a small subset (one in PR and five in RT; asterisks in Fig. 1) of the resistance sites found to be polymorphic by SGS.

Linkage of polymorphism at drug resistance sites was found on genomes in eight of 30 patients (data not shown). Of these eight, only two patients showed linkage of known drug-resistance mutations. In the first patient, a G190E mutation was linked to D30N and M46I mutations in protease. In the second patient, M41I in RT was linked on the same genome with T69N and V179E. In both cases linked mutations were found as minority variants in the population.

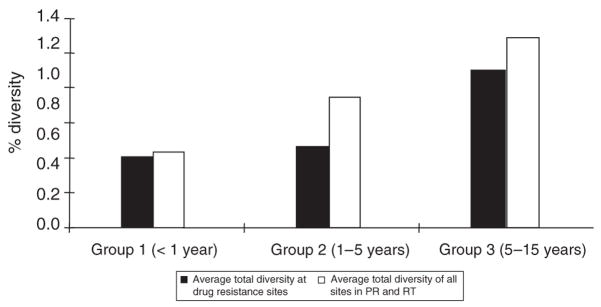

Longitudinal plasma samples, obtained from two to seven time points over a span of up to 7 years, were used to analyze variation in polymorphism in patients over time (Fig. 2). All patient samples were categorized into one of three groups based on the estimated time since infection. The first group consisted of samples collected within 1 year of infection, the second group, samples collected within 1–5 years after infection, and the third group, samples collected 5–15 years after infection. The diversity of each sample was measured for all sites in pro-pol as well as for drug resistance sites only. Both the total diversity and the diversity at drug resistance sites increased with greater time post-infection, maintaining approximately the same ratio (0.79) across all groups. Thus, the frequency of polymorphism at drug resistance sites increased with the time after infection and with the overall viral diversity.

Fig. 2. Diversity versus time of infection.

The time since infection was estimated for all patients as described in Materials and methods. The black bars show average pairwise distance at drug resistance sites in protease (PR) and reverse transcriptase (RT). The white bars show the average pairwise distance of HIV-1 at all sites within the samples.

Discussion

We used SGS to characterize the frequency and types of polymorphism at drug-resistance sites in antiretroviral naive, HIV-1-infected individuals. Our data show that polymorphism at drug resistant sites is common and is grossly underestimated by standard genotyping methods. Because much of the polymorphism detected by SGS was present in only one or a few genomes in a sample, it was below the detection limit of standard population genotyping.

Although polymorphism at drug resistance sites was common, these sites were significantly more conserved than nonresistance sites. The greater conservation of resistance sites probably reflects a stronger selective disadvantage of any mutation and hence, the lower frequency of polymorphism, most likely relating to their location near structurally and functionally constrained regions of PR and RT. This finding supports the results presented in earlier reports of conservation of resistance sites relative to nonresistance sites using bulk sequencing techniques or cloning [8–11].

The extent of polymorphism at drug resistance sites varied by gene and by drug class. The NNRTI resistance associated sites were most frequently polymorphic (1.8% of total genomes), followed by NRTI (1.2%), and by PI (0.2%). The higher frequency of polymorphism at drug resistance sites in RT may be due to lesser constraints on these sites in the enzyme compared to PR. Interestingly, although polymorphism in PR was found to be less frequent than in RT, mutations detected in PR were more often known drug resistance mutations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Polymorphism at drug resistance sites detected by single genome sequencing (SGS) in HIV infection.

| Position in PR | PI mutationsa (# genomes)b | Position in RT | NRTI mutationsa (# genomes)b | Position in RT | NNRTI mutationsa (# genomes)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L23 | none | M41 | I(3) | A98 | S(124) |

| L24 | none | E44 | K(3) | L100 | F(1) |

| D30 | N(3) G(1) | A62 | T(2) | K101 | R(12) |

| V32 | none | K65 | none | K103 | R(12) |

| L33 | V(149) | D67 | N(3) G(2) A(1) R(1) | V106 | A(3) L(1) I(1) |

| M46 | I(8) | T69 | N(26) S(27) P(3) | V108 | I(1) L(1) |

| I47 | none | K70 | E(1) | V179 | D(111) E (86) I(36) A(1) |

| G48 | R(1) | L74 | V(1) | Y181 | none |

| I50 | none | V75 | none | Y188 | none |

| F53 | L(2) | F77 | none | G190 | E(2) A(1) R(1) |

| I54 | V(1) | Y115 | H(1) | P225 | none |

| G73 | C(1) R(1) | F116 | none | F227 | none |

| L76 | none | V118 | I(95) F(1) | M230 | R(2) I(1) |

| V82 | I(1) | Q151 | R(1) | ||

| I84 | none | M184 | I(1) L(3) T(1) L(2) | ||

| N88 | none | L210 | F(103) | ||

| L90 | M(1) | T215 | C(159) P(4) S(4) | ||

| K219 | E(2) Q(1) R(2) |

NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor, PR, protease, RT, reverse transcriptase.

Amino acid changes at designated position. Changes to amino acids conferring drug resistance shown in bold.

Number of genomes detected by SGS with designated mutation out of 2229 genomes.

Polymorphism at drug resistance sites increased with time and with the total genetic diversity of the virus population. Patient samples collected >5 years post-infection contained highly diverse virus populations and had more frequent polymorphism at drug resistance sites. This data suggests that the longer patients are infected with HIV, the higher their viral diversity will be, and the greater likelihood they will have virus carrying resistance mutations. The clinical significance of this observation remains to be determined.

In summary, this study reveals that polymorphism at sites associated with drug resistance exists frequently prior to antiretroviral therapy, and that its frequency is underestimated by standard, population genotyping methods. Although pre-existing drug resistance mutations were often detected as minor variants, very few instances of linked drug resistance mutations were found. The absence of such linkage is consistent with the efficacy of combination antiretroviral therapy. The impact of these nonlinked, pre-existing, drug resistance mutations on antiretroviral therapy remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Robert Stephens and Dr Gary Smythers of SAIC, Frederick for aid with sequence analyses, Linda Apuzzo of Johns Hopkins University for aid in obtaining clinical specimens and sample information, Christopher Kearney of NCI-Frederick for aid with data analyses, and Valerie Boltz and Ann Weigand for many helpful conversations. We also express our gratitude to the patients for participating in these studies. This work was supported in part by a grant (AI 41532) to J.B.M. and a NCI contract to J.W.M. (SAIC 20XS190A). This work was done in partial fulfillment of thesis requirements for M.K. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

References

- 1.Palmer S, Boltz V, Maldarelli F, Kearney M, Halvas EK, Rock D, et al. Selection and persistence of nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 in patients starting and stopping nonnucleoside therapy. Aids. 2006;20:701–710. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216370.69066.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coffin JM. HIV population dynamics in vivo: implications for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science. 1995;267:483–489. doi: 10.1126/science.7824947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouzine IM, Coffin JM. Evolution of human immunodeficiency virus under selection and weak recombination. Genetics. 2005;170:7–18. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.029926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer S, Kearney M, Maldarelli F, Halvas EK, Bixby CJ, Bazmi H, et al. Multiple, linked human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance mutations in treatment-experienced patients are missed by standard genotype analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:406–413. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.406-413.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer S, Wiegand AP, Maldarelli F, Bazmi H, Mican JM, Polis M, et al. New real-time reverse transcriptase-initiated PCR assay with single-copy sensitivity for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in plasma. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4531–4536. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4531-4536.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTALW: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple-sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties, and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, Thompson JD. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornelissen M, van den Burg R, Zorgdrager F, Lukashov V, Goudsmit J. pol gene diversity of five human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes: evidence for naturally occurring mutations that contribute to drug resistance, limited recombination patterns, and common ancestry for subtypes B and D. J Virol. 1997;71:6348–6358. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6348-6358.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lech WJ, Wang G, Yang YL, Chee Y, Dorman K, McCrae D, et al. In vivo sequence diversity of the protease of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: presence of protease inhibitor-resistant variants in untreated subjects. J Virol. 1996;70:2038–2043. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.2038-2043.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozal MJ, Shah N, Shen N, Yang R, Fucini R, Merigan TC, et al. Extensive polymorphisms observed in HIV-1 clade B protease gene using high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat Med. 1996;2:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner D, Brenner B, Mosis D, Liang C, Wainberg MA. Substitutions in the reverse transcriptase and protease genes of HIV-1 subtype B in untreated individuals and patients treated with antiretroviral drugs. Med Gen Med. 2005;7:69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]