Abstract

Research targeting disparities in breast cancer detection has mainly utilized theories that do not account for social context and culture. Most mammography promotion studies have used a conceptual framework centered in the cognitive constructs of intention (commonly regarded as the most important determinant of screening behavior), self-efficacy, perceived benefit, perceived susceptibility, and/or subjective norms. The meaning and applicability of these constructs in diverse communities are unknown. The purpose of this study is to inductively explore the social context of Filipina and Latina women (the sociocultural forces that shape people’s day-to-day experiences and that directly and indirectly affect health and behavior) to better understand mammography screening behavior. One powerful aspect of social context that emerged from the findings was relational culture, the processes of interdependence and interconnectedness among individuals and groups and the prioritization of these connections above virtually all else. The authors examine the appropriateness of subjective norms and intentions in the context of relational culture and identify inconsistencies that suggest varied meanings from those intended by behavioral theorists.

Keywords: relational culture, mammography, intention, subjective norms, social context

Extensive behavioral research has sought to reduce disparities in breast cancer stage at detection on the assumption that use of life-saving routine mammograms can be increased in any population if determinants of screening behaviors are understood and if this understanding is the basis for mammography promotion interventions (Crosby, Kegler, & DiClemente, 2002). Such studies have often utilized behavioral, communication, or social psychology theories to identify mediating influences on mammography behavior, theories that explicitly solely focus on individual cognition. Interventions are expected to be effective if the mediating variables strongly relate to the behavior of interest as predicted by theory and if strategies exist to manipulate mediators to achieve the desired outcome (Baranowski, Cullen, Nicklas, Thompson, & Baranowski, 2003). Although a large literature has recorded numerous tests of and challenges to dominant theories in social psychology and behavioral science, surprisingly little research has explored the applicability of major theories, their constructs, and their methods for populations experiencing health disparities, typically communities of color or those of low socioeconomic status. Furthermore, despite admonitions for greater consideration of culture in the body of theory designed to guide health promotion practice among vulnerable populations (Ashing-Giwa, 1999; Pasick, 1997; Vega, 1992), basic research on health behavior and culture has not been conducted.

BACKGROUND

In almost all cancer screening promotion studies, the conceptual framework (if specified) includes some combination of the constructs of intention, self-efficacy, perceived benefit, perceived susceptibility, and/or subjective norms, with intention commonly regarded as the most important determinant of screening behavior (Gochman, 1997). The theories that contain these constructs are the health belief model (Becker, 1974), theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991), trans-theoretical model (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997), and health action process approach (Schwarzer, 1992). A common thread throughout these models is an assumption that human action is guided by

beliefs about likely outcomes of the behavior and the evaluations of these outcomes (behavioral beliefs), beliefs about the normative expectations of others and motivation to comply with these expectations (normative beliefs), and beliefs about the presence of factors that may facilitate or impede performance of the behavior and the perceived power of these factors (control beliefs). (Ajzen, 2005, p. 135)

Together, these beliefs are said to lead to the formation of a behavioral intention or motivation to engage in a particular behavior. For example, according to the TPB, one of the dominant health behavior models (Ogden, 2003), a woman will more likely express the intention to be screened if she holds favorable views about an action (e.g., mammography), perceives her significant others to view mammography positively, and perceives herself to have control over obtaining a mammogram. In most of the theories, in the absence of actual barriers (e.g., lack of insurance) or perceived barriers, having such an intention in itself means that the behavior will almost certainly be carried out, thus treating intention as a more powerful predictor of behavior than attitudes, the positive or negative perceptions one holds about the behavior (Ajzen, 1991). In fact, intention is regarded as so predictive of screening that many studies have used this construct as the main outcome when actual screening cannot be measured, including studies targeting women from diverse ethnic backgrounds (e.g., Ham, 2005; Levy-Storms & Wallace, 2003; Valdez, Banerjee, Ackerson, & Fernandez, 2002).

A notable feature of the above theories is an exclusive focus on accessible beliefs, that is, beliefs that individuals are consciously aware of and can report on in answering survey questions. This is as opposed to the core beliefs described in social psychology (i.e., deep-seated automatic thoughts or cognitions) that are held at the level of unconsciousness (Hobbis & Sutton, 2005). It also differs from social science conceptions whereby people respond both directly and indirectly to situations using culturally derived meanings as a basis for their actions or practices, with some meanings arising from sources outside of individual awareness (Bourdieu, 1990; Giddens, 1984). Fishbein and Ajzen (2005) dismissed such concerns by indicating that these distal or “background factors” (including social status, level of education, and presumably culture) influence intention and behavior only indirectly. These authors asserted that because these influences occur via normative, control, and behavioral beliefs (proximal factors), measurement and intervention restricted to this realm are sufficient and appropriate for understanding and improving behavior.

The normative beliefs component (subjective norms) has been the subject of more debate than the other four constructs under investigation in this study because of overall weak performance in predicting intention (e.g., its theorized function in the TPB) compared with attitudes and control beliefs. In general, there is agreement that the normative component is important but that measurement has been faulty (Armitage & Conner, 2001). One major aspect of this faulty measurement has been the decision to focus many research studies on a limited set of social roles or people who are presumed to be significant others—such as mothers, husbands, and sisters. Yet others may be strong influences on women’s behavior as demonstrated, for example, by Washington, Burke, Joseph, Guerra, and Pasick (2009) in this volume and by a study of mammography use among rural women by Steele and Porche (2005). The latter, like many others, noted that women can be strongly influenced to obtain mammograms by individuals outside the circle of family and friends such as lay helpers (e.g., Earp, 2002) or breast cancer survivors (Erwin, Spatz, Stotts, & Hollenberg, 1999). Yet the standard subjective norms measures fail to capture the influence of these apparently powerful referents. For example, in our own study of mammography among women from five ethnic groups, Stewart, Rakowski, and Pasick (2009) found cross-sectional associations between recent screening and belief in annual mammography by some referent groups (best friend and the category “most people important to you”) that reached statistical significance for some but not all ethnic groups. Also, recent screening was associated with trying to comply with a belief in annual mammography again for some referent groups (respondent’s sister, doctor, people important to respondent) for the sample overall and for one’s sister and doctor, and only among Latinas for most people important to them.

Studies to test the theorized associations among the above constructs have rarely included ethnically diverse samples, calling into question the extent to which the theories and their constructs can be relied on to alter behaviors associated with health disparities. The findings among studies that have explored construct or theory appropriateness in communities of color or those who are underserved often have not supported the empirical adequacy of the models for behaviors such as Pap smear testing (Jennings-Dozier, 1999) and exercise (Trost et al., 1999). In our multiethnic cohort study of mammography mentioned above, Stewart et al. (2009) found an association between intention at baseline and recent mammography 2 years later that was significant only among White women (odds ratio = 5.0, 95% confidence interval = 2.4, 10), with a statistically significant race/ethnicity interaction (p = .02). Thus, intention strongly predicted future screening, but only for White women and not for the African Americans, Chinese, Filipinas, or Latinas in this sample. Because this is the only longitudinal cancer screening study we are aware of that involves multiple race/ethnic groups and languages, this finding is important in light of the assumption that intention is an outcome that is treated as nearly equivalent to the practice of screening itself. Yet it may not have the predictive value that has been observed in mainstream populations, suggesting the possibility of ethnic differences in the meaning or relevance of the construct or the validity of the item.

Our analysis of subjective norms found screening to be more strongly associated with normative beliefs than with motivation to comply. Women who reported that their best friend, sister, mother, husband, doctor, or important people (i.e., all the referents measured) believed in annual mammography had about twice the odds of getting regular mammograms than those without such influences. For motivation to comply, associations were found only for some of the referent others. Screening was associated with trying to act on the beliefs of one’s sister or doctor but not of one’s best friend, mother, or husband. Associations with screening did not differ by race/ethnicity for subjective norms regarding some of the specific people (e.g., mother, husband). However, there was a differential effect of subjective norms regarding “most people important to you” by race/ethnicity, which may be because of the classification of different types of people as important.

BEHAVIORAL CONSTRUCTS AND CULTURE FOR CANCER SCREENING (THE 3Cs STUDY)

In the course of prior screening promotion research in diverse communities by several members of this research team (e.g., Hiatt et al., 1996), we observed that the constructs most commonly used to predict or promote mammography screening, including (a) intention, (b) self-efficacy, (c) perceived benefit, (d) perceived susceptibility, and (e) subjective norms, yielded mixed findings from survey analyses and that they provided little guidance in the design of measures and messages. To better understand the value of the dominant theories across cultures, we developed a study to assess the cultural appropriateness of these five behavioral theory constructs. The study, titled 3Cs (Grant R01 CA81816, R. Pasick, principal investigator), involved a multidisciplinary team in a mixed methods exploration of behavioral theory and cancer screening to address two questions: First, is the meaning of constructs among ethnically diverse women consistent with that intended by the theories? And second, are there important influences on the screening behavior of these women that are not accounted for in the theories?

This line of questioning requires examination of the constructs within rather than abstracted from the social context in which health behavior occurs. Social context, the conceptual framework for this study, is defined as the sociocultural forces that shape people’s day-to-day experiences and that directly and indirectly affect health and behavior (Burke, Joseph, et al., 2009; Pasick & Burke, 2008). Social context includes multiple dimensions of social and cultural phenomena in daily life: historical, political, and legal structures and processes (e.g., colonialism and migration), organizations and institutions (e.g., schools and clinics), and individual and personal trajectories (e.g., family, community). We understand culture as the patterned process of people making sense of their world and the conscious and unconscious assumptions, expectations, knowledge, and practices they call on to do so. The term patterned indicates that culture is neither random nor monolithic. Instead, there are consistencies within culture that are at the same time flexible and situationally responsive: People bring culture into being as they go about creating their world—making the structures, institutions, rituals, and beliefs that reflect and (re)produce individual and collective sense-making activities. Culture is the outcome of a group of people and their diverse, often overlapping, sometimes contradictory, creative attempts to make sense of their world and live in it (Kagawa-Singer, 1997). (For a more detailed discussion of social context and culture, see Burke, Joseph, et al. 2009).

On this basis, we inductively explored the meaning of the five behavioral theory constructs in two ethnic groups, Filipina and Latina women, using semistructured, open-ended interviews with expert and lay respondents. This approach triangulated multiple perspectives to illuminate processes and practices in daily life that would not be evident from only one point of view. It is important to note that this study does not attempt to characterize or to compare Filipinas and Latinas. Rather, it explores sociocultural context in two immigrant populations whose experiences exemplify a range of differences from the U.S. European American middle-class mainstream. The similarities of these populations, in terms of social context (e.g., colonialism, immigration, discrimination, therapeutic engagement), are our focus in analyzing the appropriateness of the behavioral constructs examined in the 3Cs study. We chose these two groups because (a) they have low rates of breast cancer screening (Jacobs, Karavolos, Rathouz, Ferris, & Powell, 2005; Kagawa-Singer et al., 2007), (b) they were included in our quantitative study already under way and we had the most prior data collection and intervention experience with them, (c) they are well represented in the San Francisco Bay area, which is 4.8% Filipino and 19.4% Latino (Bay Area Census, 2000), and (d) both were represented by members of our team, allowing for the important insider–outsider research perspectives (Kagawa-Singer, 2000).

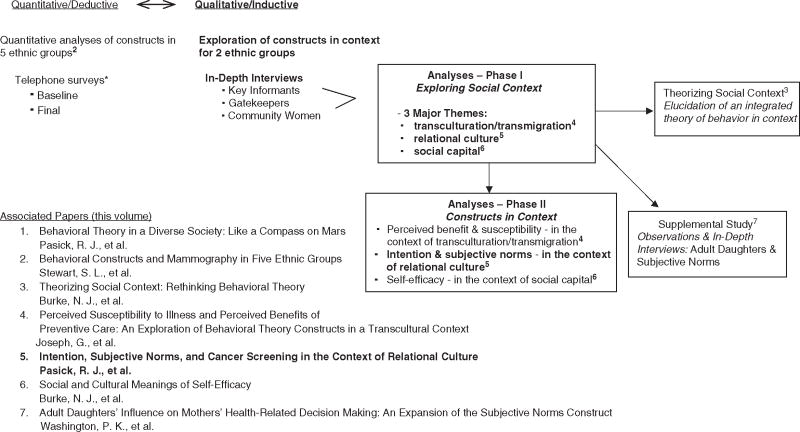

The 3Cs inductive component identified three powerful facets of social context that affect mammography choices in the lives of the U.S. Filipina and Latina women we studied: social capital, the benefits that accrue from participation in social networks and groups (Burke, Bird, Guerra, & Pasick, 2009); transculturation and transmigration, cultural change processes and migration in which relationships are sustained across national boundaries, respectively (Joseph, Burke, Tuason, Barker, & Pasick, 2009); and relational culture, the processes of interdependence and interconnectedness among individuals and groups and the prioritization of these connections above virtually all else. Although these domains are inextricably interconnected in complex ways and have implications for all five constructs in question, for reporting purposes we identified the most significant context–construct linkages and conducted analyses to explore perceived susceptibility and benefits in the context of transculturation (Joseph et al., 2009) and meanings of perceived self-efficacy in the context of social capital (Burke, Bird, et al., 2009). Analyses of intention and subjective norms vis-à-vis relational culture are the subject of this report in which we first discuss key aspects of the concept of relational culture from the literature. This is followed by a brief summary of the 3Cs study methods that led to our understanding of relational culture and that provided the foundation for analyses of behavioral constructs in relation to social context. Finally, we present findings from analyses that examined the meanings of the constructs of intention and subjective norms in the context of relational culture. The overall 3Cs study design with the various study components and evolution of this report is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Behavioral Constructs and Culture in Cancer Screening (3Cs) study design and associated reports.

*Access and Early Detection for the Underserved, Pathfinders (1998 to 2003), a mammography and Pap screening intervention trial under way when 3Cs began.

RELATIONAL CULTURE

The particular importance of the family among some ethnic groups and the centrality of the church for others are among the most common representations of culture found in the behavioral research literature. Such phenomena may be operationalized in scales to measure social support or social networks as factors that predispose one to a healthy behavior, as appropriate communication channels, or the portrayal of images intended to resonate with a particular target audience. These representations can be characterized in accordance with Resnicow, Ahluwalia, and Braithwaite (1999) as a “surface structure” approach to cultural sensitivity in public health, in contrast to “deep structure,” addressing the influence of sociocultural, historical, and environmental influences.

One long-recognized “deep structure” that distinguishes societal formations has, in various theoretical forms, underpinned and permeated the social and psychological sciences for more than 100 years (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002). Durkheim (1897/1997), for example, described this deep structure as distinct forms of relational constellations, and as varying degrees of solidarity (i.e., the kind of relationships that can exist between members and their social institutions). However, concepts such as these became encapsulated and truncated—losing their experiential and institutional contexts—in many psychological theories as the concepts of individualism and collectivism (Triandis, 1995). These concepts are claimed to explain many facets of behavior. In so-called “collectivist cultures,” people view themselves as members of a group as much as a singular self; such connections are much looser for “individualistic cultures” where an emphasis is placed on independence rather than interdependence. According to social scientist Geert Hofstede, one of the most influential voices on this topic, “The individualism versus collectivism distinction has become the main challenge to the universal applicability of Western psychological theories” (Triandis, 1995, back cover). Despite varying schools of thought on their nature, these important concepts have made only limited appearances in the literature on health behavior (e.g., Kreuter, 2003; Pasick, D’Onofrio, & Otero-Sabogal, 1996).

Although some theorists and many research studies treat individualism–collectivism as a measurable and bounded continuum, our concept of social context leads us to a more dynamic formulation. The difference has been described thus:

The direct assessment approach assumes that cultural frame is a form of declarative knowledge (e.g., attitudes, values, and beliefs) that respondents can report on rather than some set of more subtle and implicit practices and social structures that respondents cannot report on because these practices are deeply woven into everyday life and are a normal part of living. (Oyserman et al., 2002, p. 7)

Thus, we question the universality of Western psychological theories by using the concept of “relational culture” rather than the individualism–collectivism dyad. Note that relational culture is not unique or specific to particular ethnic groups but, rather, to some degree is common to all groups. Every group has occasions on which it is proper for members to behave in an independent or interdependent fashion. Differences can be found, however, in the valence, the emphasis, that various groups place on interdependence, family and personal relationships as sources of knowledge, security, comfort, and reassurance. It is the priority people assign to the known, the familiar, the recognizable; priority over the impersonal, the untried, the strange, and the new—things or people with whom one has no previous or existing connection. For us, relational culture connotes that “understanding comes not merely from the individual’s own observation and knowledge construction but through human interactions … [that] meanings [are not located] ‘within the individual,’ … but ‘in between’ the self and the other” (Bandlamudi, 1994, p. 462). Thus, meanings are constructed through a dynamic social intercourse, a connection, a process rather a static objectified measurable construct. This conception forms the lens through which we scrutinize the meanings of behavior theory constructs.

METHOD

The 3Cs study methods consisted of open-ended interviews first with Latino and Filipino academics as key informants (KIs; n = 11), then with Latino and Filipino health and social service providers and activists as community gatekeepers (GKs; n = 13), followed by Filipina and Mexican American community women (CW; n = 29). All respondents were either primary immigrants or first-generation U.S. born. KIs were a mix of men and women, whereas GKs were all women. In general, these three groups represent a range of education levels (KIs being the most highly educated with either PhDs or MDs and community women having the least education) and varying degrees of comfort in and knowledge of the dominant U.S. culture (again, KIs having the most, GKs representing an intermediate level, and community women having the least).

Each set of interviews addressed similar domains, informed the next set of interviews, and provided insights into the meanings of intention and subjective norms for Latinas and Filipinas contemplating accessing health care in general and mammography screening in particular. For each group of respondents, interviews were continued until we reached data saturation—that is, until no new themes emerged in the narratives or during initial data analysis (Glaser & Strauss, 1974). Informed consent was obtained from all respondents, and study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco.

Analyses examined the degree of compatibility of the intention and subjective norms constructs and their underlying assumptions within the context of relational culture. On one hand, where constructs are largely consistent with the overarching domain, the constructs may be seen as appropriate for Filipina and Latina women such as those we interviewed. Seeming incompatibility, on the other hand, could take the form of contradiction with some of the central tenets of the construct or possibly represent new dimensions not addressed by these constructs or the theories from which they come. A detailed account of methods, including questions asked of each respondent group, is reported by Pasick et al. (2009).

RESULTS

First, we report exemplary quotes from all categories of respondents that describe the dimensions of relational culture. Next, within this context, responses with implications for intention and subjective norms are presented against the backdrop of relational culture.

Relational Culture

References to relational culture themes permeated discussions on wide-ranging topics across all categories of respondents, clearly identifying this concept as a fundamental social context domain. Not a new discovery especially but not exclusively in the social sciences, the complex concept of relational culture presents new perspectives on health decisions and behavior. These are most likely applicable to many other ethnic groups of color who experience cancer disparities. It is important that the range of relational connections, some quite nuanced, reveal a pervasiveness and multidimensionality that seem incompatible with customary approaches to health behavior in research and practice. The following are three major themes of relational culture that emerged from our data: (a) interdependence (subthemes include concept of self or connectedness, prioritization of others, accompaniment), (b) familiarity, caring, trust, and harmony, and (c) sense of obligation.

Interdependence

KIs described worlds where interpersonal connections were paramount but in dynamic rather than static, delineable representations:

If you call it “relation–ships,” it essentializes what I would say, it’s relational because it’s a process, not [an] essence…. It’s about how one maneuvers life as a process, not how one feels fatalistic or not fatalistic, or happy or not happy. (KI7)

The many such insights of our respondents cast commonly stereotyped phenomena in a more meaningful light, as in the following quote explaining a widely recognized practice among many immigrant Latinas, that of going about daily business in the company of family members and/or friends rather than alone:

It’s relational that you’re not an individual that lives in your head but you’re an individual that lives in processes with other human beings. And so it’s very distressing to me when people write about it as like you’re just this underdeveloped person who needs other people or else you don’t know who you are. (KI7)

Concept of Self, Prioritization of Others, and Accompaniment

Our respondents described the processes of self relating to others in relational culture. For example, Filipinos have many terms that express fundamental interconnectedness, including pakiki-pagkapwa-tao (regard for the other person’s humanity), where kapwa is shared identity, the sense that I and the other are one (de Guia, 2005):

That kapwa, you know it’s very very deep … kapwa means other, literally, and loob is your inner self. So it emphasizes the relationship between myself and the others. (KI4)

In other words, two people connected in some fashion compose the minimum functional unit. This conception of self is a strong thread woven throughout daily life. These characterizations reflect a construal of “self” as a fraction that can be whole only in combination with others (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). As these authors note, when one’s perception of self reflects embeddedness in a larger context, “other objects or events will be perceived in similar ways” (Markus & Kitayama, 1991, p. 246).

The self is related to everything outside of it … nature and the creator and other human beings and other living things. So, it’s the interconnectedness of life. (KI4)

These and other similar assertions reveal concepts of self that are not fully autonomous, independent, or separate entities but are integral to significant others.

So, you teach your kids to be aware of what your role is in the community and how your behavior affects your family … which is a big difference from kids who grew up here and who don’t have that sense, you know? And, it’s very … more individual … it’s like, “Well, who cares what I do? It’s only affecting me.” But, “No, what you do affects the family … and the community sees you as the family.” (GK4)

Our exploration of interdependence and concept of self demonstrates how the multiple perspectives of our study respondents (i.e., from KIs, GKs, and women) combine to form a coherent picture. Although KIs were able to speak of “relational process” and GKs described individuals in relation to their community, this context would not have been clear from descriptions by lay women alone:

When I go with someone else, I feel better because alone it’s like I look stupid…. So when I go by myself, I am … I just want to go back. I just want to leave the place. (CW3)

She cannot explain why people go together (husband and wife always go to doctor as couple):

I don’t know. I think so they know what’s going on. I don’t know. To know everything. (GK5)

The following further describes this relational process of accompaniment.

I think that there’s usually more accompaniment. I think that certain medical procedures—and that goes across the board for people for all sorts of different reasons—people just don’t want to go. Like a pap smear—nobody wants to get a pap smear. So those are the kinds of appointments that I think people tend to go to alone or just flat out not go…. In general when health issues come up, it’s the whole thing of accompaniment. I mean, my mom lives in Arizona and if she has a significant doctor’s appointment she expects me to get on a plane and fly out there and go with her. (GK10)

This GK went on to explain that her mother lives with her father and sister, yet her accompaniment is required for important medical appointments, not just because she is a valued family member but also because she is a key resource to her family and community, able to provide access to medical knowledge, explain procedures, and ask crucial questions. In other words, in these situations she represents social capital that can be deployed for everyone’s good (for further details on this concept, see Burke, Bird, et al., 2009). For those who do not prioritize others in this way, the process of accompaniment may be poorly understood. As one GK explained,

Going together in groups is not an idiosyncratic behavior—it’s a manifestation of a “way of being” that is relational. (GK5)

Familiarity, Caring, Trust, and Harmony

People from all ethnic and cultural groups tend to feel more comfortable among and often seek out the company of their “folk.” The need to be in a group with other people like themselves is called pakikisama by Filipinos and estar en familia by Latinos. The immigrant experience makes this even more compelling:

There’s that Filipino philosophy which is pakikisama … that you like to be in a community … and that’s who we are as Filipinos … that community is really important to us … and a sense of belonging. … You want to find a group of people that you can celebrate with … that you can mourn with … that you can, you know, basically feel an attachment with. … You know you can have a sameness, so it’s not so foreign being here. (GK4)

Why do immigrants congregate as a group? … That’s a culture, which is a [barkada]…. Barkada is a peer grouping…. When you have a problem with a Filipino, the first statement is it’s not [only] your problem, you’re not alone…. [In a research] paper in Germany, when they checked the immigrants on the choices of where to be located, their first choice is not the salary [they could get] or the hospital that they want to work on. They check if they can form a barkada…. It’s unique. (GK12)

Familiarity in relational culture takes many forms and plays a variety of important roles.

Now the other thing is that one-shot deals work less effectively than continuing kind of relationships, and it is a relational culture. So … a lot of people are trying … to go and invest in Mexico and they have a lot of interventions in teaching businessmen what they can expect in terms of how you get contracts in Mexico. And the thought that you’re going to go to lunch in an hour and a half [and form a bond, it’s] just not going to happen … because it is really about relations and talking and getting to know people, and you to know the family … the more relational you make your intervention, and more consistent, the more likely you are to have an effect. (KI7)

The benefits or manifestations of relational culture can be key to health communication in clinic and community settings. Respondents expressed several ways in which familiarity, caring, and trust are not only valued but also essential for credibility, salience, and thus effective communication. For example, asked about whether a promotora (outreach worker) really made a difference by accompanying women to a medical appointment, a GK responded,

Oh yes. I think once you develop a familiar face and understand where they’re coming from and what help you can give them, I think the caring piece is a very important factor. (GK8)

Informants explained that in relational culture authority comes not from rank or scientific quality of information but from close and caring relationships:

But uh, a familiere. And so if you’re trying to talk about cancer screening and that kind of thing to the community, what I would do if I were doing it would be to find someone I know in the community who then in turn has those connections…. Because a direct approach from a stranger, even if in a position of authority, might be met with courtesy, and again we’re accepting this information, but most likely they will not internalize it and be convinced that this is what they need to do. (KI4)

And really … you cannot convince the traditional Filipino that “research has shown.” No, no, no…. Do, do you know uh, whatever her name is? You know she said that it is great. “Oh really?” Okay, so that, it’s that, it’s a person that they’re relating with rather than … the research…. She is not believed because of her authority, but she is believed because there was a caring relationship between the two of them and therefore whatever she says, she must say this because she cares about me, you know. So that, that, so that interpersonal. (KI1)

In relational culture, the quality of the relationship establishes the credibility of the information. In other words, the messenger can be far more important than the message. A GK explained how she conveys caring to convince her patients:

This is important for me, you know, in bringing you back … and then, I show them, you know, “This is really important…. I want you to do…. I would be really sad, you know, if anything happens to you, and you know … because you didn’t take this medicine and I didn’t explain it to you well.” … And then they feel a little bit responsible. (GK5)

The fundamental nature of relationships is also reflected in the concept of harmony, exemplified in the Latino term simpatia, which emphasizes maintenance of a pleasant demeanor in verbal communication and deemphasizes negativity in avoidance of conflict (Comas-Diaz, 1989, p. 38).

If you were to ask Filipinos and I suppose Asians here, what is it that would make you happiest? “If we lived in harmony with each other.” Not that I win over you … that we live in harmony with each other … the opposite of utang na loob [harmony] … is the Spanish word ingrato. And the worst thing that can be said to you is that you, you know, ingrato…. So, that really is something. So some of these traditional values operate still among the Filipinos, no matter how educated perhaps they are. (KI1)

For both Latinos and Filipinos, maintenance of harmony in relationships is paramount. Thus, relations with others may be prioritized over expression of one’s true feelings. Only a glimpse of the importance of this theme and all of its manifestations, this collection of quotes reveals some of the “deep structure” of the fabric of relational cultures.

Subjective Norms

Subjective norms in relational cultures differ from those in health behavior theories, where the specific focus of subjective norms is one’s perceptions of others in terms of pressure to comply (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Respondents in this study spoke of relationships not being the source of pressure but essential to the decision process:

I think, well, for the immigrant adult, uh, whether you’re educated or less educated the culture in itself generally speaking is already a collective culture, a communal culture…. So um I would say decisions are always arrived at in consultation with that network. Um, if only to affirm that your only dependent thinking is, you know, in sync with … [her] … network at least. So we always need that kind of affirmation. Just to make sure that we are in tune with everybody else, you know. (KI4)

This idea of “network consultation” was echoed by another KI:

KI: More than likely before she does that herself, she will have consulted her friends … she will have, you know, the support…. If you wanted to do a [birth control] project … you would have to get people of the same age talking to each other.

Int: So she would not read something in a magazine and go off and do it?

KI: Oh no, no. No. (KI1)

Another facet of the association between relational culture and adopting a new behavior such as mammography has to do with maintenance of harmonious relationships, in this case with a promotora with whom a woman had said she would go get a mammogram:

GK: I think there are a lot of people who are going to do it, [who] feel their word is honorable. Maybe they don’t feel like going, but the thought of the word, that relationship…. Because they said they were going, because they had that connection and that they said they were going to go.

Int: The connection with the promotora?

GK: Yes.

Int: So they wouldn’t want to disappoint her.

GK: Yes. It’s an honor thing. (GK8)

These statements also reflect the strong sense of obligation that was mentioned by many respondents. Referring once again to the concept of familiarity, this GK stated that influential others need not be family, friends, or even those from the same ethnic background but must be empathetic and understanding individuals:

GK: It depends on their relationship with you…. If you’ve developed a relationship with them, and they trust you, they will comply. They’re more likely to comply.

Int: Do you have to be a Pilipino nurse?

GK: No … not at all…. Um, you have to be able to communicate to them in a way that they understand the … I don’t mean linguistically.

Intention

Our data present a contextualized perspective of likely influences on intention, revealing (a) differences in the meaning of stated intention, (b) dimensions of sociocultural context that appear incompatible or inconsistent with the assumptions underlying the intention construct, and (c) important influences not accounted for in the determinants or assumptions associated with intention.

Differences in the Meaning of Stated Intention

According to the theories that include this construct as noted earlier, when one states the intention to perform a behavior, the likelihood of doing so is high. Such straightforward meaning is a fundamental form of “low-context” understanding, where one says what is meant, regardless of the contextual influences (Gao & Ting-Toomey, 2007). Low-context communication is associated with societies that prioritize independence. Alternatively, in indirect or “high-context” communication, more meaning may be found in what is not said but is implied and understood based on the situation.

I think also just the communication style within the United States is very direct. Somebody asks you a question—say for example: “Do you want a glass of water?” or “Do you want a cookie?”—in Latin America you go, “No, I couldn’t possibly impose on you.” You have to say no three times before you can yes. In the United States it’s much more direct. “You want a cookie? Okay. You don’t? Bye.” And that’s kind of the end of the conversation. For many of our clients, it’s a process. (GK10)

Thus, among members of the same group, “yes” is understood as “maybe yes, maybe no.”

We have something like … I’ll say, “Are you going to the meeting tomorrow?” “Yes, I’ll come … I’ll come.” … You know … sometimes they don’t come! It’s very important that you know that … you have to learn to see if they really mean it or not…. It’s because they don’t want to disappoint the person, but it’s more disappointing if you don’t come, right? But that’s just the way we are…. You have to tell them, “It’s important that you come … if not, you just tell me.” … It’s okay for you to tell me that you can’t come,” you have to tell them that … that’s how I deal with it. (GK2)

One reason that “yes” may be stated when “no” is meant is that indicating one’s intention to comply is regarded as desirable, polite, and respectful. Maintenance of harmony in relationships in this way is all important and is manifest by not saying no.

But they don’t want to see the nutritionist, but it’s really impolite to say, “No, I don’t want to see your nutritionist.” So they’ll just say, “Yes, I’ll go see the nutritionist” or “Yes, I’ll go to the doctor and I’ll do this.” And then they never do it…. They say yes because they don’t want to be impolite. Saying no is impolite. (GK10)

Dimensions of Sociocultural Context That Appear Incompatible or Inconsistent With the Assumptions Underlying the Intention Construct

Relational culture can positively affect screening even in the absence of perceived susceptibility to breast cancer (a determinant of intention):

Int: But are you going back for the mammogram next year?

Woman: I’ll see if I will need one…. They say it is really needed, but I told them I don’t feel any pain. I thought when you feel something … that’s it. Then you have to have a mammogram. That’s what I was told. The doctor checked me but they didn’t see anything. They still give me an appointment for a mammogram, so I’ll go. (CW15)

This is true also in the absence of beliefs about the benefits of screening (another determinant of intention):

If you don’t have that relationship with them, they’re less likely to do it…. I think they do it mostly for us … because we’re recommending that they get this mammogram … they themselves don’t understand why they need to … so they trust you…. So they’re getting the message that, “This is important for your health … so, come in and get this done.” (GK4)

In fact, screening can take place where intention is absent and where perceptions of susceptibility and benefit are not meaningful. The following may reflect more structural than cultural aspects of social context but with important implications for the intention construct nonetheless:

Like I want to change my birth control—okay. You need to have a pap smear. And that’s why I would have gone in. But to go just because: oh my god, I think I could get cancer? No, I wouldn’t have. And here you’d think—I don’t know. It’s just the whole denial thing. If you really sat and thought about it: “Oh, I have to make an appointment because I could have cancer” then you start thinking—I don’t think about it. But if I’m going in because I need to change birth control and they’re doing it anyway then that’s okay…. If I just thought it was a regular thing when you hit 40 that you have to go in and that a mammogram was part of it I would go. But would I go just from seeing breast cancer awareness and get tested at this age? I wouldn’t. (GK11)

Similarly, intention may be fluid as a result of system barriers:

Okay, how can we get them access to mammograms right here and now, while, you know, they’re convinced instead of waiting 5 months to get that mammogram appointment … ’cuz it takes so long, and by then, they change their mind … they don’t want to do it anymore. So, it’s hard. (GK4)

Influences Not Accounted for in the Determinants of Intention

Many women have grown accustomed to the inability to do all they intend; they cope by accepting that some important things must be put off.

We don’t get screened because of decidia; decidia means we put it off—we’re negligent. (KI4)

Int: Do you go for preventative exams?

SP: No, almost never.

Int: Are there any you have gotten done? …

SP: … When they told me about this, I thought, “Well it would be a good idea to get it done.” Because I have never got it done [laughing]. But I think that we are just too desidioso. I think that most us are desidioso.

Int: What does desidioso mean?

SP: … It means that we never make the decision: “We have to do this.” We leave it for later … for later, you know? We are indecisive, right? I say it like that. I don’t know how you say it. (CW12)

You know what, I really don’t know. Because we can say that it’s cultural, like I said. I mean, don’t go to the doctor unless something is hurt. But, it’s not necessarily true. ’Cuz there are some women that even with problems, do not make the phone call to go. I really don’t understand why we delay and delay and delay doing some kind of things. ’Cuz it’s not all the times, but, for medical appointment, it’s like, “I’ll do that tomorrow … I’m going to call tomorrow.” And, a lot of the women, when I talk, like the Latino women when I say, “You know what, you need to make that appointment or something,” they say, “Well, I haven’t done it because” … what is that … decidia … that word … decidia … a lot of the Mexican women use that word … which is laziness…. “I haven’t done it because I haven’t had time” … or they just say plain for decidia…. “Which is because I’ve been lazy” … that’s what they say. (GK1)

This concept was also identified in open-ended questions as the most cited reason Mexican and Dominican women in New York do not get mammograms. Garbers, Jessop, Foti, Uribelarrea, and Chiasson (2003) described it as descuido, with a slightly different interpretation from those presented by our informants, as not taking care of one’s self. This is similar to a report from a Filipino GK, who noted,

Among overall priorities, health in some sense is not important “Oh, that’s not important. I have so many things to do.” [It’s] hard to understand that individual health is important. (GK4)

Among the many things that come with women’s roles is caring for others, especially their children. Our participants spoke in a great many ways of how their responsibility to care for their children and other family members meant their own personal health came last. This form of self-sacrifice is highly valued and one in which women take great pride.

My mom was very good about taking care of her kids, but when it came to her, she didn’t. My mother suffered a heart attack and didn’t tell anybody and that’s what took her. And she had a heart attack, she kept it to herself, and her health started deteriorating … it wasn’t until she went to the cardiologist that they determined that she had had a heart attack, and basically her heart was completely damaged. It was enlarged, and she suffered for a good 2, 3 years…. If she would have said, I’m sick I need to go to emergency. If she had gotten help right away, she would still be with us. That’s what I don’t understand. She took care of all her kids, she was so good about taking care of her kids and making sure they got proper health care, and then when it came to her it was like, what happened? (CW2)

Being desidioso or descuido is not an entirely negative or irresponsible stance. Rather, a certain degree of indecision gives these women flexibility in responding to the more immediate pressures of everyday life. Given that the day-to-day reality of their lives is a constant struggle with poverty, difficult access to health services, and discrimination, desidioso provides psychic as well as literal breathing space, enabling, if necessary, a response to any unexpected change in circumstance, be that job loss, eviction, occupational injury, marital stress, or deportation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we broadly explored the lives of Filipina and Latina women in the United States through the eyes of expert KIs, community GKs, and the women themselves. Rather than directly studying the practice of mammography and querying women about why they do or do not get screened, we sought to develop an understanding of the important processes that affect all aspects of their lives, including their health behavior. From there, we drew inferences about the meaning of two behavioral constructs and whether or not the constructs and their assumptions appear consistent with our observations.

The picture that emerged revealed complex interpersonal connections that can be variously described as nuanced and obvious, consciously evident as beliefs and unconsciously evident as ways of being. Regardless of the form it took in our interviews, the importance of relational culture as a driving force in most facets of behavior was profound. Interpersonal connectedness has been studied in relation to health behavior in many forms, as social networks, social support, social capital, and social influence, to name a few. Our findings thus reaffirm the power and pervasiveness of the broad underlying concept of human connection, which, again, is not a new discovery but instead a “given” in many other fields. The contribution of our study is in conceptualizing these connections as a form of social context with implications for the dominant approach to studying health behavior and for key behavioral theory constructs in particular. Although preliminary in this regard, we expect that our conclusions will carry considerable face validity among researchers and practitioners who have spent time in communities such as those we studied. It is important that our findings underscore the importance to health behavior researchers to look to other disciplines to understand and explain behavior, especially the social sciences (e.g., anthropology and sociology) and humanities (e.g., history and political science), when studying different cultural or socioeconomic groups.

CONCLUSIONS BY CONSTRUCT

At the broadest level, by virtue of the fact that subjective norms acknowledge the importance of relationships for health behavior, this construct can be seen as a step toward integration of social context and behavior. In addition, we clearly saw evidence that urging by, information from, and the feelings of known trusted others are among the most valued and salient behavioral influences. However, many aspects of the operationalization of subjective norms appear inconsistent with our understanding of relational culture. First, one assumption of the construct is the emphasis on definable, expressible beliefs both on the part of a respondent and among her referents (mother, sister, etc.) such that referents would have beliefs about what the respondent should do and she in turn would be aware of those beliefs and able to articulate what they are. Although this could be true for many Filipina and Latina women, we could also expect that these issues may be more implicit rather than overtly discussed. Second, that there would be pressure to comply is also plausible but more likely is a process of consultation in the form of considerable back and forth deliberation on large and small decisions as two or more individuals work toward a joint conclusion. In this way, distinctions between individuals may be blurred as they interact so deeply and consistently that much is shared between them. Thus, the notion of “doing what others think you should do” would be a crude and distorted representation of a process so natural as to be literally unremarkable. In the context of indirect communication, such expressions could likely be considered rude as well.

The construct of intention appears fraught with inconsistencies and limitations in the context of relational culture, and on this basis we conclude that it should not be used as if it is a universal construct. First, it is clear that there can be important variations in meaning when a person states an intention to do something, whether it is to visit a friend or get a mammogram. That people within a common group implicitly understand that yes may also mean no itself calls the construct into question. In addition, we described circumstances where a woman may get a mammogram without having an explicit intention about breast cancer screening, such as when she goes just to please a promotora or how some women may be willing to accept a screening only if it is slipped in with other necessary procedures such as obtaining birth control. On the other hand, a woman may indeed intend to get a mammogram, but she is overwhelmed by other responsibilities or simply does not prioritize her own health over that of others. These findings suggest that there can be differences in the relationship among intention toward screening behavior, missing predictors, and entirely different issues and relationships from what the theories suggest.

Our study is an endeavor to peer from different perspectives into intact daily lives of women in two ethnic groups to obtain the most realistic understanding of influences on health behavior. In this way, we seek to avoid the artificial extraction of specific behaviors from their social context, a process that necessarily produces gaps and even distortions. The best outcome from these findings would be increased interest in the exploration of social context among all underserved communities not only using ethnographic methods but also integrating multiple forms of qualitative and quantitative data in ways that maximize the strengths of each method. The creative use of mixed methods to study health behavior in this way could finally break the longstanding preoccupation with individual cognition that has so constrained the field of cancer disparities intervention research.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Relational culture is a powerful force that can be extraordinarily positive when understood and embraced by researchers and practitioners or terribly harmful to individuals and communities if ignored in our theories and practice. It is likely that this concept figures as more important in the behavior of many people than does the construct of intention. These implications apply to practitioners involved at all levels of cancer screening from outreach and education to clinical care, service delivery, and policy making. Education from a caring member of one’s own community, delivered in a personal manner, is not reproducible or replaceable by any form of technology. A doctor or nurse who takes the time to learn about a patient’s family or identify something the two may have in common increases the likelihood that the patient will return for follow-up care. Services designed to accommodate or encourage accompaniment will be perceived as credible and will be better used. Policies that allow clinicians to see and connect with the same patients over time can foster more effective communication and thus better prospects for maintaining their health.

These are not new ideas. Social scientists and health services and communication researchers have repeatedly demonstrated the value of familiarity and caring in the clinician–patient relationship. More poorly understood, however, is the significance of failure to address this issue. Impersonal, unwelcoming services can represent as impenetrable a barrier to care as language differences among those for whom relational culture is fundamental to their way of life. Although to some people an aloof clinician may be annoying, for others this can be a matter of “I don’t know you, so I can’t hear you.” This means that communication from an uncaring stranger is not even heard, literally, let alone trusted. Such an unwelcoming environment is perceived as outright hostility never to be approached again. These situations can actually mean the difference between life and death when they lead to avoidance of the health care system. Thus, for researchers and practitioners serving immigrant communities, cultivating an understanding of social context, particularly relational culture, could prove more useful than interventions based on current theories.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (Grant RO1CA81816, R. Pasick, principal investigator).

This supplement was supported by an educational grant from the National Cancer Institute, No. HHSN261200900383P.

Contributor Information

Rena J. Pasick, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, San Francisco.

Judith C. Barker, Department of Anthropology, History, and Social Medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

Regina Otero-Sabogal, Institute for Health and Aging, University of California, San Francisco.

Nancy J. Burke, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center and Department of Anthropology, History, and Social Medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

Galen Joseph, Department of Anthropology, History, and Social Medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

Claudia Guerra, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, San Francisco.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality and behavior. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: A meta- analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40:471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa K. Health behavior change models and their socio-cultural relevance for breast cancer screening in African American women. Women & Health. 1999;28(4):53–71. doi: 10.1300/J013v28n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandlamudi L. Dialogics of understanding self/culture. Ethos. 1994;22(4):460–493. [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Nicklas T, Thompson D, Baranowski J. Are current health behavioral change models helpful in guiding prevention of weight gain efforts? Obesity Research. 2003;11:23S–43S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay Area Census. San Francisco Bay area. 2000 Retrieved from http://www.bayareacensus.ca.gov/bayarea.htm.

- Becker MH, editor. Health Education Monographs. Vol. 2. 1974. The health belief model and personal health behavior; pp. 324–508. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The logic of practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Burke NJ, Bird JA, Clark MA, Rakowski W, Guerra C, Barker JC, et al. Social and cultural meanings of self-efficacy. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl 1):111S–128S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke NJ, Joseph G, Pasick RJ, Barker JC. Theorizing social context: Rethinking behavioral theory. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl 1):55S–70S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109335338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Diaz L. Culturally relevant issues and treatment implications for Hispanics. In: Koslow DR, Salett E, editors. Crossing cultures in mental health. Washington, DC: Society for International Education Training and Research; 1989. pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RA, Kegler MC, DiClemente RJ. Understanding and applying theory in health promotion practice and research. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- de Guia K. Kapwa: The self in the other. Pasig City, Philippines: Anvil Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. Suicide. New York: Free Press; 1997. Original work published 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Earp JA. Increasing use of mammography among older, rural African American women: Results from a community trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):646–654. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Stotts RC, Hollenberg JA. Increasing mammography practice by African American women. Cancer Practice. 1999;7(2):78–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen IJ. Theory-based behavior change interventions: Comments on Hobbis and Sutton. Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10(1):27–31. doi: 10.1177/1359105305048552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Ting-Toomey S. Communicating effectively with the Chinese. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Garbers S, Jessop DJ, Foti H, Uribelarrea M, Chiasson MA. Barriers to breast cancer screening for low-income Mexican and Dominican women in New York City. Journal of Urban Health. 2003 March;80(1):81–91. doi: 10.1007/PL00022327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. The constitution of society. Cambridge, UK: Polity; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Gochman DS. Handbook of health behavior research I: Personal and social determinants. New York: Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ham OK. The intention of future mammography screening among Korean women. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2005;22(1):1–13. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2201_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt RA, Pasick RJ, Perez-Stable EJ, McPhee S, Engelstad L, Lee M, et al. Pathways to early cancer detection in the multiethnic population of the San Francisco Bay Area. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23(S):S10–S27. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbis IC, Sutton S. Are techniques used in cognitive behaviour therapy applicable to behaviour change interventions based on the theory of planned behaviour? Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10(1):7–18. doi: 10.1177/1359105305048549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs EA, Karavolos K, Rathouz PJ, Ferris TG, Powell LH. Limited English proficiency and breast and cervical cancer screening in a multiethnic population. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(8):1410–1416. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings-Dozier K. Predicting intentions to obtain a Pap smear among African American and Latina women: Testing the theory of planned behavior. Nursing Research. 1999;48(4):198–205. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph G, Burke NJ, Tuason N, Barker JC, Pasick RJ. Perceived susceptibility to illness and perceived benefits of preventive care: An exploration of behavioral theory constructs in a transcultural context. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl 1):71S–90S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa-Singer M. Addressing issues for early detection and screening in ethnic populations. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1997;24(10):1705–1711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa-Singer M. Improving the validity and generalizability of studies with under-served U.S. populations expanding the research paradigm. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10(8):S92–S103. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa-Singer M, Pourat N, Breen N, Coughlin S, Abend McLean T, McNeel TS, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening rates of subgroups of Asian American women in California. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(6):706–730. doi: 10.1177/1077558707304638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: Targeted and tailored approaches. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30:133–146. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Storms L, Wallace SP. Use of mammography screening among older Samoan women in Los Angeles county: A diffusion network approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57(6):987–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00474-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98(2):224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden J. Some problems with social cognition models: A pragmatic and conceptual analysis. Health Psychology. 2003;22:424–428. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Coon HM, Kemmelmeier M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(1):3–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ. Socioeconomic and cultural factors in the development and use of theory. In: Glanz K, Lewis F, Rimer B, editors. Health behavior and health education theory. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 425–440. [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Burke NJ. A critical review of theory in breast cancer screening promotion across cultures. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:351–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.143420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Burke NJ, Barker JC, Joseph G, Bird JA, Otero-Sabogal R, et al. Behavioral theory in a diverse society: Like a compass on Mars. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl 1):11S–35S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, D’Onofrio CN, Otero-Sabogal R. Similarities and differences across cultures: Questions to inform a third generation for health promotion research. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23(S):S142–S161. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: Defined and demystified. Ethnicity & Disease. 1999;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R. Self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors: Theoretical approaches and a new model. In: Schwarzer R, editor. Self-efficacy: Thought control of action. Washington, DC: Hemisphere; 1992. pp. 217–243. [Google Scholar]

- Steele SK, Porche DJ. Testing the theory of planned behavior to predict mammography intention. Nursing Research. 2005;54(5):332–338. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SL, Rakowski W, Pasick RJ. Behavioral constructs and mammography in five ethnic groups. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl 1):36S–54S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. Individualism & collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Trost SG, Pate RR, Dowda M, Ward DS, Felton G, Saunders R. Psychosocial correlates of physical activity in White and African-American girls. Nursing Research. 1999;48(4):198–205. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez A, Banerjee K, Ackerson L, Fernandez M. A multimedia breast cancer education intervention for low-income Latinas. Journal of Community Health. 2002;27(1):33–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1013880210074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA. Theoretical and pragmatic implications of cultural diversity for community research. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;20(3):375–391. [Google Scholar]

- Washington PK, Burke NJ, Joseph G, Guerra C, Pasick RJ. Adult daughters’ influence on mothers’ health-related decision making: An expansion of the subjective norms construct. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36(Suppl 1):129S–144S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]