Abstract

Intention, self-efficacy, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, and subjective norms are key constructs of health behavior theories; their predictive validity for cancer screening has not been ascertained in multiethnic populations. Participants were 1,463 African American, Chinese, Filipina, Latina, and White women aged 40 to 74 interviewed by telephone in their preferred languages. The relationship between base-line constructs and mammography 2 years later was assessed using multivariable logistic regression. Intention predicted mammography overall and among Whites (odds ratio [OR] = 5.0, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.4, 10), with racial/ethnic differences in association (p = .020). Self-efficacy predicted mammography overall and among Whites (OR = 3.5, 95% CI = 1.1, 11), with no racial/ethnic interaction. Perceived benefits and subjective norms were associated with screening overall and in some racial/ethnic groups. These results generally support cross-cultural applicability of four of the five constructs to screening with mixed predictive value of measures across racial/ethnic groups. Additional in-depth inquiry is required to refine assessment of constructs.

Keywords: perceived benefits, perceived susceptibility, self-efficacy, intention, subjective norms, cross-cultural measurement

Intention, self-efficacy, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, and subjective norms are key components of several well-known models of health behavior. Since the early 1970s, many theories have been proposed to help explain health-related behaviors. The health belief model (HBM; Janz, Champion, & Strecher, 2002), social cognitive theory (SCT; Bandura, 2004), theory of reasoned action/planned behavior (TRA/PB; Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2002), transtheoretical model (TTM; Prochaska, Redding, & Evers, 2002), precaution adoption process model (Weinstein & Sandman, 2002), and protection motivation theory (Rogers, 1983) are among the most prominent. Each has its core constructs, typically conceptualized as potential barriers or facilitators for a desired health behavior. These constructs are used both to predict screening and as the focus for interventions.

Although the five above-listed behavioral constructs have been widely used in health research, their applicability to cancer screening in multiethnic, multilingual populations has been less well studied. It is important that the construct of intention is regarded as an immediate determinant of volitional behavior (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2002) such that changes in intention are often used as the main outcome in intervention trials when screening cannot be measured (Wang et al., 2008). Intention is also key to the differentiation of stages in the very widely used TTM (Prochaska et al., 2002). Yet the predictive validity of this construct with regard to mammographic screening has not been tested for comparability across racial/ethnic groups. In other words, does stated intention mean the same thing to women of different cultures and who speak different languages? In addition, it is unclear whether the single-item indicators developed for mainstream Anglo populations and typically used in multipurpose health surveys effectively operationalize the constructs in ethnically diverse populations.

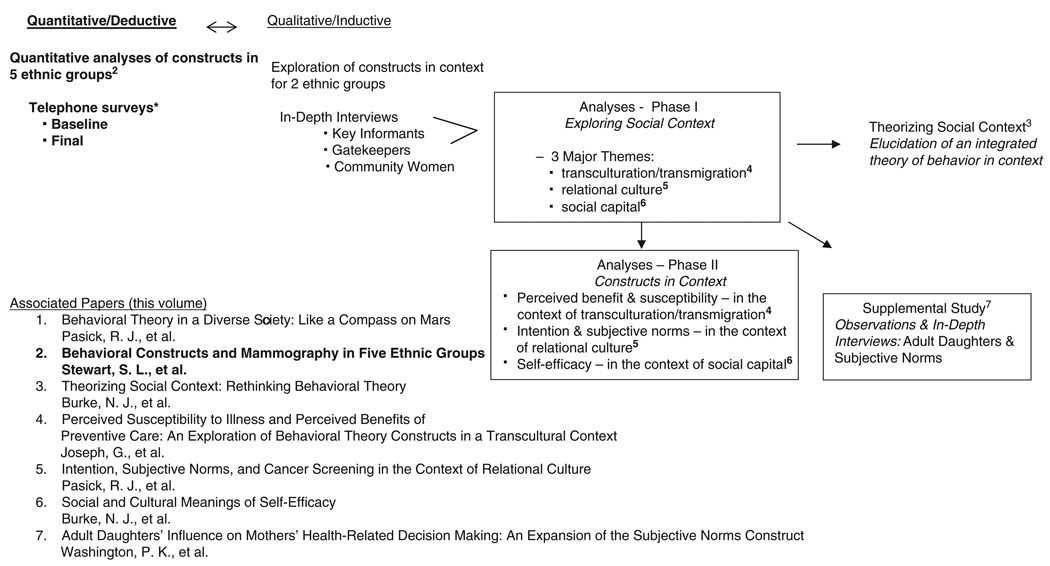

As part of a mixed methods study to examine the cultural appropriateness of the five stated constructs in relation to mammography use, this article begins to assess the effectiveness of the constructs and the value and meaning of common construct measures by reporting analyses from a multiethnic, multilingual survey. The study, Behavioral Constructs and Culture in Cancer Screening (3Cs), was designed to assess the cultural appropriateness of these constructs related to mammography screening by combining deductive quantitative analyses of data from five ethnic groups with an intensive inductive qualitative exploration of the constructs (see Figure 1; the inductive findings are reported elsewhere in this volume; for overall study outcomes, see Pasick, Burke, et al., 2009) among Filipina and Latina women. This approach is intended to provide a multifaceted understanding of the cross-cultural applicability of the constructs and, if indicated, to inform their subsequent adaptation. Although quantitative analyses can demonstrate patterns of association, they cannot discern the effects of measurement characteristics from those of underlying theoretical assumptions. However, the combination of quantitative deductive and qualitative inductive analyses allows for a rich and full exploration of the cross-cultural meaning and comparability of theoretic constructs.

Figure 1.

Behavioral Constructs and Culture in Cancer Screening (3Cs) study design and associated reports.

*Access and Early Detection for the Underserved, Pathfinders (1998 to 2003), a mammography and Pap screening intervention trial under way when 3Cs began.

This article reports the predictive validity of five constructs representing key content in several behavioral theories that have been applied to the use of breast cancer screening: (a) intention to obtain a mammogram, (b) perceived self-efficacy to obtain a mammogram, (c) perceived benefits of mammography, and (d) perceived susceptibility to breast cancer. The cross-sectional association between subjective norms (measured only in the final survey) and mammography is also reported.

Intention to perform a behavior (perceived likelihood of performing the behavior) is a central construct of TRA/PB, SCT, TTM, and the precaution adoption process model. For TRA/PB, intention is the immediate determinant of behavior such that when an appropriate measure of intention is obtained it will provide the strongest prediction of behavior. According to these theories, intention is a function of attitudes toward the behavior and subjective norms (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2002). Efficacy beliefs may affect performance both directly and by influencing intentions (Bandura, 1997). For TTM, intention is integral to the change from precontemplation to action, and in the precaution adoption process model, intention is part of the decision to act.

Self-efficacy refers to beliefs in one’s capabilities to execute the courses of action required to produce a particular outcome (Bandura, 1997). This is a key construct in SCT, the theory of planned behavior, and protection motivation theory and is also in TTM. Most measures of self-efficacy for health behaviors are a single item or short scale using items of the form, “I am certain that I can do xx, even if yy (barrier)” (Schwarzer & Luszczynska, 2007). Despite some variation in measurement, there is substantial evidence demonstrating its predictive value and general agreement on the use of the concept (Ajzen, 2001).

Perceived benefit of a behavior and the difficulties of carrying out the behavior are basic constructs of HBM (benefits and barriers), TTM (pros and cons), SCT, and TRA/PB. Champion (1999) developed a five-item scale to measure the perceived benefits of mammography, establishing its validity and reliability in an HMO and general medical population. Skinner, Champion, Gonin, and Hanna (1997) demonstrated that perceived benefits and barriers successfully differentiated among women at different stages of mammography compliance.

Perceived susceptibility, which refers to an individual’s belief about the likelihood of developing a particular health problem, is a major construct of HBM, the precaution adoption process model, and protection motivation theory. Perceived susceptibility has been variously measured as absolute (e.g., a numerical probability estimate), conditional (given future behavior), or relative to other people (Gerrard & Houlihan, 2007). Champion (1999) developed a three-item scale measuring perceived susceptibility to breast cancer and demonstrated its reliability and validity in members of an HMO and general medicine clinic. A recent meta-analysis (Katapodi, Lee, Facione, & Dodd, 2004) found an overall positive association between perceived susceptibility and screening mammography.

Subjective norms are a TRA/PB behavioral construct that is the product of two components: perceived normative beliefs and motivation to comply. Normative beliefs refer to important others’ expectations for the individual’s performance of a specific behavior, and motivation to comply refers to the individual’s willingness to adhere to these expectations (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2002). Subjective norms, along with attitudes, are posited in TRA/PB as direct influences on intentions to perform a behavior.

METHOD

The data for the study were collected in the baseline and final surveys of a randomized, controlled trial to promote breast and cervical cancer screening (Access and Early Detection for the Underserved, Pathfinders) that was conducted in Alameda County, California, from 1997 to 2003 (Somkin et al., 2004). The primary theoretical framework for the intervention was TTM (Rakowski, Fulton, & Feldman, 1993). To reach potential participants, we used a modified random-digit dialing (RDD) technique (Waksberg, 1978) with telephone prefixes that were associated with low-income zip codes or a relatively high proportion of Filipino residents. The RDD sample was supplemented with listed surname samples to reach additional Chinese and Filipino households.

Eligible participants were female residents of the county aged 40 to 74 who self-identified as African American, Chinese, Filipina, Latina, or non-Hispanic White; were able to be interviewed in English, Cantonese, Tagalog, or Spanish; and had no personal history of cancer. Participants agreed to be randomized, to be contacted every 6 months for the next 3 years, and to allow participating health clinics to validate type of health insurance and receipt of screening. Sampling was stratified by race/ethnicity and age. Verbal consent was obtained for eligible women who agreed to participate, and an interview was scheduled for approximately 2 weeks later. Participants were interviewed by telephone in their preferred language by professional bilingual, bicultural female interviewers a maximum of three times: at baseline, in a brief second wave survey (Mdn = 10 months later), and in a final survey on completion of the intervention (Mdn = 26 months after baseline). Respondents were compensated $10 for the first two interviews and $20 for the third interview.

Following the baseline survey, participants were randomized 1:1 to the study arms. Intervention group members received tailored printed health guides following the base-line and second wave surveys and tailored telephone counseling between the second wave and final surveys. Control group members received greeting cards after the base-line and second wave surveys and a tailored health guide following the final survey. The committees on human research of the collaborating institutions approved the research protocol.

Response Rate

A total of 46,206 telephone numbers were called, of which 32,521 (70%) were household numbers. We attempted to screen all households for eligibility. A total of 17,257 (53%) households were not screened because a respondent could not be found (76%), they did not complete the screener (14%), or they refused (10%). Among the 15,264 (47%) households screened, 2,963 (19%) contained an eligible respondent. Reasons for ineligibility included not being a member of a study racial/ethnic group (20%), not speaking any of the study languages (10%), not having a woman aged 40 to 74 in the household (66%), having a history of cancer (2%), and residing or planning to move out of the area (1%). Among eligible respondents, 1,840 (62%) consented to participate in the study. Of those who agreed to participate, 1,463 (80%) were recontacted, enrolled in the study, and interviewed, with 1,175 (80%) completing the final survey. The overall response rate was 49% (1,463 of 2,963 eligible respondents); racial/ethnic-specific response rates were African American (52%), Chinese (39%), Filipina (36%), Latina (52%), and White (68%). Characteristics of the study participants are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of Demographic Characteristics and Screening Status by Race/Ethnicity

| African American |

Chinese | Filipina | Latina | White | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline n | 497 | 199 | 167 | 300 | 300 | 1,463 |

| Age in years (M, SD) |

52.1, 9.0 | 52.3, 9.2 | 54.8, 9.4 | 50.7, 8.5 | 52.6, 8.4 | 52.3, 8.9 |

| Education in years (M, SD) |

13.6, 2.4 | 10.6, 4.4 | 14.2, 3.1 | 8.7, 4.5 | 16.5, 2.9 | 12.9, 4.3 |

| Married (%) | 32 | 85 | 73 | 66 | 54 | 56 |

| Income level (%) | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 43 | 41 | 15 | 42 | 17 | 34 |

| $20,000 to $50,000 |

35 | 34 | 27 | 35 | 31 | 33 |

| ≥$50,000 | 21 | 14 | 51 | 9 | 51 | 27 |

| Missing | 2 | 12 | 7 | 14 | 1 | 6 |

| ≤10 years in United States (%) |

<1 | 32 | 20 | 23 | 1 | 12 |

| Non-English interview (%) |

0 | 86 | 34 | 73 | 0 | 31 |

| Insurance status (%) | ||||||

| Private | 61 | 52 | 83 | 48 | 87 | 65 |

| Public | 25 | 24 | 11 | 16 | 6 | 17 |

| None | 14 | 24 | 6 | 36 | 7 | 17 |

| Regular doctor (%) | 81 | 83 | 85 | 65 | 86 | 79 |

| Baseline mammography status (%)a | ||||||

| Never | 12 | 22 | 11 | 14 | 9 | 13 |

| Not recent | 29 | 27 | 31 | 29 | 27 | 29 |

| Recent, not regular | 8 | 12 | 16 | 18 | 9 | 12 |

| Regular | 51 | 39 | 43 | 39 | 55 | 47 |

| Final n | 407 | 154 | 121 | 235 | 258 | 1,175 |

| Final mammography status (%)a | ||||||

| Never | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Not recent | 23 | 12 | 23 | 30 | 20 | 22 |

| Recent, not regular | 9 | 25 | 7 | 13 | 8 | 11 |

| Regular | 62 | 58 | 67 | 53 | 67 | 61 |

NOTE: Age, 1 missing; education, 14 missing. All variables differ across race/ethnicity at p < .001 except years in United States (p = .021). Language of interview and years in United States tested among Chinese, Filipina, and Latina only.

Never = never had a mammogram; not recent = most recent mammogram more than 15 months before interview; recent, not regular = most recent mammogram within 15 months of interview, no mammogram within 2 years of most recent; regular = most recent mammogram within 15 months of interview and a prior mammogram within 2 years of the most recent.

Measurement

Forty-minute structured questionnaires were developed for the baseline and final surveys. Many of the measures were obtained from questionnaires used in our prior cancer screening studies with comparable populations (Hiatt et al., 2001). Additional items were newly developed using focus groups and in-depth interviews or adapted from other studies and refined by our multiethnic team of researchers for comprehension and for linguistic, cultural, and content validity. Items were initially developed in English using terms known by the multilingual research team to be readily translated into Spanish, Cantonese, and Tagalog. Questions were back translated, decentered, and pretested in English and the other three languages (Pasick, Sabogal, et al., 1996).

Behavioral Constructs

Four of the five constructs were measured at both the baseline and the final surveys. These items were used in our previous studies of cancer screening in multiethnic populations (Hiatt et al., 2001). Subjective norms were not measured at baseline because they were not part of the Pathfinders intervention; they were added to the final survey for the 3Cs study. It should be noted that through pilot testing and previous studies, we determined that scaled response options could not be used in a multilingual sample with diverse socioeconomic status, particularly with questions administered by phone. Thus, only two response choices were offered at a time as described below.

Intention (“Do you plan to have a mammogram in the next 12 months?”), a single-item measure with response options yes or no, was based on a similar question used to determine mammography stage of adoption (Rakowski et al., 1993).

Self-efficacy (“Do you think that you could get a mammogram every year?”) was also a single-item measure with response options yes or no, similar to one of two items in a self-efficacy measure associated with mammography intention (Allen, Sorensen, Stoddard, Colditz, & Peterson, 1998). It is important that the common wording for this measure is, “Do you feel confident that you could get a mammogram every year?” However, confident does not translate from English to the other three languages.

Perceived susceptibility (“Compared to other women your age, do you think your chances of getting breast cancer are likely, or not at all likely?”) was a single-item measure. When the respondent chose one of those alternatives, she was then asked, “Is that very (un)likely or a little (un)likely?” This item was based on a measure of relative risk associated with mammography intention (Lerman et al., 1991).

Perceived benefits included five items based on mammography pros from a decisional balance scale associated with mammography stage (Rakowski et al., 1993) and similar to the perceived benefits items of Champion (1999). Early detection (“In your opinion, if breast cancer is detected at an early stage, what is a person’s chance of surviving?”) had response options excellent, good, not very good, or none (categorized as excellent/good vs. not very good/none for item-specific analysis). Four items—control over health (“Having a mammogram every year will give you a feeling of control over your health”), good for family (“It will be good for your family if you have a mammogram”), peace of mind (“Yearly mammograms give you peace of mind”), and lower mortality (“Having a mammogram every one to two years decreases a woman’s chance of dying from breast cancer”)—had response options agree or disagree. After selecting one of these alternatives, women were asked, “Is that strongly (dis)agree or somewhat (dis)agree?” A perceived benefits summary score was computed by assigning the values 0 to 3 to the four ordinal response categories for each item and summing the responses for the five items; “don’t know” responses were assigned the midpoint value.

For item-specific analysis of all of the above constructs, “don’t know” responses were included in the negative category (no, very/a little unlikely, not very good/none, strongly/somewhat disagree).

Subjective norms were measured using six pairs of items of the form, “Do you think [referent person] believes that you should have a mammogram every year?” with response options definitely does not believe it, probably does not believe it, she/he is neutral, probably does believe it, or definitely does believe it, and “How often do you try to do what [referent person] believes that you should do?” with response options never, seldom, about half the time, usually, or always. These items are similar to those of a subjective norms scale associated with both mammography participation and intention (Montaño & Taplin, 1991). Consistent with the definition of subjective norms as a product of normative beliefs and motivation to comply, the two items in each pair were combined and recoded into three categories for referent-specific analysis: (a) referent person definitely or probably believes and respondent usually or always tries to do what referent person believes (i.e., motivation to comply with a positive normative belief), (b) referent person definitely or probably believes and respondent does not usually or always try to do what referent person believes (i.e., positive normative belief without motivation to comply), and (c) referent person does not definitely or probably believe (i.e., no positive normative belief). “Not applicable” and “don’t know” responses regarding the referent person’s belief were included in the third category. The six referent persons were “your best friend,” “your sister,” “your mother,” “your husband,” “your doctor,” and “most people who are important to you.” A subjective norms summary score was computed by assigning the values 0 to 4 to the five ordinal response categories for each item, multiplying the responses for each pair of items, and summing the six products; “not applicable” and “don’t know” responses were assigned the mid-point value. For this construct, we used standard response items to assess how well they worked in this sample.

Self-reported mammography screening was measured at each survey wave. Based on published guidelines (Smith et al., 2003) and alternative mammography stages that do not include intention (Rakowski et al., 1993), mammography screening status was categorized for all ages as follows: (a) never had a mammogram; (b) not recent—most recent mammogram more than 15 months (i.e., 12 months plus a 3-month grace period) before interview; (c) recent, not regular—most recent mammogram within 15 months of interview, no mammogram within 2 years of most recent; and (d) regular—most recent mammogram within 15 months of interview and a prior mammogram within 2 years of the most recent one. These categories were combined to form a binary dependent variable, recent mammography (“regular” or “recent, not regular” vs. “not recent” or “never”), for logistic regression analysis.

Sociodemographic variables included age (in years), education (in years), race/ethnicity (African American, Chinese, Filipina, Latina or White), language of interview (English or non-English), number of years in the United States (≤10 or >10), annual household income (<$20,000, $20,000 to $50,000, ≥$50,000, or unknown), and marital status (married or living with a partner vs. divorced, widowed, or single). Variables indicating access to medical care included health insurance (private, public, or none) and having a regular doctor.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses of baseline data included all 1,463 participants; analyses of final data included the 1,175 participants who also completed the final survey. The distributions of sociodemographic factors, baseline and final mammography screening status, and behavioral construct measures were compared across racial/ethnic groups using chi-square tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance for numeric variables (see Table 1). Longitudinal models of receipt of a recent mammogram at the time of the final survey (the dependent variable), as a function of each of the four constructs measured at baseline and race/ethnicity (the independent variables), were analyzed using multi-variable logistic regression controlling for baseline screening status, study arm, time between the baseline and final survey, and other potentially confounding factors, that is, age, non-English language of interview, years in the United States, education, marital status, household income, health insurance, and having a regular doctor. Separate models were constructed for each of the five perceived benefits, the perceived benefits summary score, perceived susceptibility, self-efficacy, and intention (see Table 2). Subjective norms constructs were measured only in the final survey. Multivariable logistic regression was also used to assess the cross-sectional relationship between receipt of a recent mammogram and each subjective norms measure and race/ethnicity, controlling for the covariates listed above. Separate models were constructed for each subjective norms referent (best friend, sister, mother, husband, doctor, most people who are important to you); an analogous model using the subjective norms summary score was also constructed (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Longitudinal Association Between Recent Mammography at Final Survey and Behavioral Constructs at Baseline by Race/Ethnicity

| Construct | Race/ Ethnicity |

Total n | % Yes | % Screened if Yesa |

% Screened if No, DKa |

ORb | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy; could get a mammogram every year (R2 = .22) |

African American |

407 | 93 | 72 | 54 | 1.2 | 0.5, 2.8 |

| Chinese | 154 | 73 | 88 | 71 | 1.9 | 0.8, 4.8 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 88 | 76 | 53 | 2.6 | 0.8, 8.3 | |

| Latina | 235 | 95 | 66 | 64 | 0.9 | 0.2, 3.5 | |

| White | 258 | 94 | 78 | 31 | 3.5 | 1.1, 11 | |

| All | 1,175 | 90 | 74 | 58 | 1.8 | 1.1, 2.8 | |

| Perceived susceptibility; very, a little likely to get breast cancer compared to other women (R2 =.21) |

African American |

407 | 57 | 74 | 67 | 1.5 | 0.9, 2.4 |

| Chinese | 154 | 50 | 79 | 87 | 0.6 | 0.2, 1.5 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 49 | 76 | 71 | 1.4 | 0.6, 3.4 | |

| Latina | 235 | 35 | 70 | 64 | 1.7 | 0.9, 3.3 | |

| White | 258 | 47 | 74 | 76 | 1.0 | 0.5, 1.8 | |

| All | 1,175 | 49 | 74 | 71 | 1.3 | 0.9, 1.7 | |

| Perceived benefit: Early detection; chances of survival good, excellent (R2 =.22) |

African American |

407 | 95 | 72 | 48 | 2.8 | 1.0, 7.5 |

| Chinese | 154 | 73 | 83 | 83 | 0.8 | 0.3, 2.3 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 94 | 75 | 57 | 2.4 | 0.4, 14 | |

| Latina | 235 | 86 | 67 | 58 | 2.1 | 0.9, 4.9 | |

| White | 258 | 97 | 76 | 43 | 3.3 | 0.7, 16 | |

| All | 1,175 | 91 | 73 | 64 | 1.9 | 1.1, 3.1 | |

| Perceived benefit: Control over health; strongly, somewhat agree (R2 =.22) |

African American |

407 | 88 | 72 | 61 | 1.2 | 0.6, 2.3 |

| Chinese | 154 | 95 | 85 | 50 | 5.0 | 1.0, 25 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 88 | 79 | 36 | 7.1 | 2.0, 26 | |

| Latina | 235 | 91 | 67 | 57 | 1.4 | 0.5, 3.9 | |

| White | 258 | 79 | 80 | 55 | 2.1 | 1.0, 4.2 | |

| All | 1,175 | 87 | 75 | 55 | 1.9 | 1.3, 2.9 | |

| Perceived benefit: Good for family; strongly, somewhat agree (R2 =.22) |

African American |

407 | 90 | 73 | 51 | 1.8 | 0.9, 3.9 |

| Chinese | 154 | 97 | 83 | 75 | 1.5 | 0.1, 17 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 96 | 75 | 40 | 4.7 | 0.7, 34 | |

| Latina | 235 | 94 | 66 | 67 | 0.7 | 0.2, 2.4 | |

| White | 258 | 86 | 78 | 51 | 2.2 | 1.0, 5.9 | |

| All | 1,175 | 91 | 74 | 54 | 1.8 | 1.1, 2.8 | |

| Perceived benefit: Peace of mind; strongly, somewhat agree (R2 =.23) |

African American |

407 | 92 | 73 | 42 | 2.3 | 1.0, 5.0 |

| Chinese | 154 | 99 | 83 | 100 | 0.5 | 0.01, 21 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 93 | 75 | 56 | 2.1 | 0.5, 9.5 | |

| Latina | 235 | 94 | 68 | 38 | 2.8 | 0.8, 9.7 | |

| White | 258 | 85 | 80 | 44 | 3.2 | 1.5, 7.1 | |

| All | 1,175 | 92 | 75 | 45 | 2.6 | 1.6, 4.2 | |

| Perceived benefit: Lower mortality; strongly, somewhat agree (R2 =.22) |

African American |

407 | 76 | 74 | 61 | 1.6 | 1.0, 2.8 |

| Chinese | 154 | 94 | 83 | 90 | 0.8 | 0.1, 7.9 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 86 | 77 | 53 | 3.6 | 1.1, 11 | |

| Latina | 235 | 83 | 65 | 73 | 0.6 | 0.2, 1.3 | |

| White | 258 | 91 | 77 | 57 | 1.8 | 0.7, 4.5 | |

| All | 1,175 | 84 | 74 | 64 | 1.4 | 1.0, 2.0 | |

| Perceived benefits summary score per SD (R2 = .23) |

African American |

407 | 1.3 | 1.0, 1.6 | |||

| Chinese | 154 | 1.4 | 0.7, 2.7 | ||||

| Filipina | 121 | 2.2 | 1.3, 3.8 | ||||

| Latina | 235 | 1.1 | 0.8, 1.5 | ||||

| White | 258 | 1.5 | 1.1, 1.9 | ||||

| All | 1,175 | 1.3 | 1.2, 1.5 | ||||

| Intention; plans to get a mammogram in next 12 months (R2 = .23) |

African American |

407 | 86 | 72 | 61 | 1.1 | 0.6, 2.1 |

| Chinese | 154 | 53 | 89 | 77 | 1.8 | 0.7, 4.6 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 83 | 76 | 60 | 1.7 | 0.6, 5.0 | |

| Latina | 235 | 87 | 68 | 53 | 1.0 | 0.4, 2.2 | |

| White | 258 | 81 | 84 | 38 | 5.0 | 2.4, 10 | |

| All | 1,175 | 81 | 76 | 60 | 1.7 | 1.2, 2.5 |

NOTE: DK = don’t know; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; SD = standard deviation. p = .020 for race/ethnicity–intention interaction; p > .05 for all other race/ethnicity interactions. Statistically significant ORs and CIs are shown in boldface.

Recent screening (most recent mammogram within 15 months of interview).

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, age, education, non-English language, years in United States, marital status, income, insurance, regular doctor, study arm, months between surveys, baseline screening. Logistic regression analyses (n = 1,157).

Table 3.

Cross-Sectional Association Between Recent Mammography Screening and Subjective Norms at Final Survey by Race/Ethnicity

| P Believes, R Tries to Comply |

P Believes, R Does Not Try to Comply |

P Does Not Believe, N/A |

Motivation to Comply |

Normative Beliefs |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referent Person |

Racial/ Ethnic Group |

Total n |

% of Total |

% Screeneda |

% of Total |

% Screeneda |

% of Total |

% Screeneda |

ORb | 95% CI | ORb | 95% CI |

| Best friend (R2 = .23) | African American | 407 | 24 | 80 | 56 | 72 | 19 | 57 | 1.3 | 0.7, 2.5 | 1.9 | 1.0, 3.4 |

| Chinese | 154 | 26 | 83 | 49 | 87 | 25 | 77 | 0.7 | 0.2, 2.1 | 1.6 | 0.6, 4.7 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 61 | 81 | 20 | 67 | 19 | 57 | 2.8 | 0.9, 8.5 | 1.0 | 0.3, 3.6 | |

| Latina | 235 | 35 | 71 | 47 | 66 | 18 | 55 | 1.3 | 0.7, 2.6 | 1.6 | 0.7, 3.5 | |

| White | 258 | 29 | 80 | 52 | 79 | 19 | 54 | 1.0 | 0.5, 2.1 | 2.8 | 1.3, 6.1 | |

| All | 1,175 | 32 | 78 | 49 | 74 | 20 | 59 | 1.3 | 0.9, 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.3, 2.7 | |

| Sister (R2 = .23) | African American | 407 | 25 | 80 | 44 | 67 | 31 | 68 | 1.7 | 0.9, 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.6, 1.7 |

| Chinese | 154 | 31 | 85 | 29 | 93 | 40 | 74 | 0.5 | 0.1, 2.3 | 3.3 | 0.8, 13 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 64 | 81 | 20 | 71 | 16 | 47 | 1.9 | 0.6, 5.7 | 2.4 | 0.6, 9.6 | |

| Latina | 235 | 40 | 73 | 40 | 64 | 19 | 56 | 1.6 | 0.8, 3.2 | 1.5 | 0.7, 3.4 | |

| White | 258 | 13 | 91 | 34 | 76 | 53 | 70 | 3.8 | 1.0, 15 | 1.1 | 0.6, 2.1 | |

| All | 1,175 | 30 | 80 | 37 | 71 | 33 | 67 | 1.8 | 1.2, 2.6 | 1.3 | 0.9, 1.8 | |

| Mother (R2 = .21) | African American | 407 | 51 | 71 | 26 | 73 | 23 | 67 | 0.8 | 0.5, 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.6, 2.3 |

| Chinese | 154 | 33 | 86 | 25 | 87 | 42 | 78 | 1.0 | 0.3, 3.7 | 1.2 | 0.4, 3.8 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 64 | 76 | 13 | 63 | 22 | 74 | 1.6 | 0.5, 5.6 | 0.6 | 0.1, 2.6 | |

| Latina | 235 | 47 | 65 | 17 | 58 | 36 | 72 | 1.0 | 0.4, 2.4 | 0.6 | 0.2, 1.4 | |

| White | 258 | 21 | 82 | 41 | 79 | 37 | 66 | 1.1 | 0.5, 2.7 | 1.6 | 0.8, 3.3 | |

| All | 1,175 | 43 | 73 | 26 | 75 | 31 | 70 | 0.9 | 0.6, 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.7, 1.6 | |

| Husband (R2 = .21) | African American | 407 | 16 | 76 | 22 | 77 | 62 | 67 | 0.8 | 0.3, 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.9, 3.2 |

| Chinese | 154 | 38 | 85 | 31 | 90 | 31 | 74 | 0.6 | 0.2, 2.2 | 2.5 | 0.8, 8.5 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 68 | 74 | 10 | 83 | 22 | 67 | 0.7 | 0.1, 3.7 | 1.4 | 0.2, 9.0 | |

| Latina | 235 | 41 | 68 | 22 | 67 | 37 | 63 | 1.0 | 0.4, 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.5, 2.5 | |

| White | 258 | 29 | 81 | 14 | 78 | 57 | 71 | 1.4 | 0.5, 4.2 | 1.3 | 0.5, 3.5 | |

| All | 1,175 | 32 | 76 | 20 | 78 | 48 | 68 | 0.9 | 0.6, 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.0, 2.4 | |

| Doctor (R2 = .23) | African American | 407 | 74 | 75 | 18 | 64 | 7 | 47 | 1.5 | 0.8, 2.7 | 2.0 | 0.8, 5.2 |

| Chinese | 154 | 62 | 86 | 26 | 75 | 12 | 84 | 1.4 | 0.5, 3.8 | 0.3 | 0.1, 1.5 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 78 | 77 | 9 | 55 | 13 | 69 | 2.4 | 0.6, 9.5 | 0.5 | 0.1, 2.6 | |

| Latina | 235 | 80 | 71 | 13 | 50 | 7 | 38 | 1.9 | 0.8, 4.7 | 1.9 | 0.5, 7.8 | |

| White | 258 | 74 | 81 | 11 | 64 | 16 | 55 | 2.5 | 1.0, 6.4 | 1.1 | 0.4, 3.4 | |

| All | 1,175 | 74 | 77 | 16 | 63 | 10 | 57 | 1.8 | 1.2, 2.6 | 1.2 | 0.7, 2.0 | |

| Most people important to respondent (R2 = .23) |

African American | 407 | 38 | 73 | 51 | 71 | 11 | 61 | 0.9 | 0.6, 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.7, 3.3 |

| Chinese | 154 | 42 | 88 | 35 | 85 | 23 | 71 | 1.0 | 0.3, 3.1 | 1.7 | 0.6, 5.3 | |

| Filipina | 121 | 73 | 75 | 18 | 73 | 9 | 64 | 1.1 | 0.3, 3.3 | 0.9 | 0.2, 4.6 | |

| Latina | 235 | 56 | 73 | 33 | 56 | 11 | 63 | 2.4 | 1.2, 4.6 | 0.6 | 0.2, 1.6 | |

| White | 258 | 43 | 80 | 35 | 83 | 22 | 50 | 0.8 | 0.4, 1.8 | 3.4 | 1.5, 7.9 | |

| All | 1,175 | 47 | 76 | 38 | 73 | 15 | 60 | 1.2 | 0.8, 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.0, 2.4 | |

| Subjective norms summary score per SD (R2 = .23) |

African American | 407 | 1.4 | 1.0, 1.8 | ||||||||

| Chinese | 154 | 1.2 | 0.7, 1.9 | |||||||||

| Filipina | 121 | 1.3 | 0.9, 1.9 | |||||||||

| Latina | 235 | 1.4 | 0.9, 1.9 | |||||||||

| White | 258 | 2.0 | 1.4, 3.1 | |||||||||

| All | 1,175 | 1.4 | 1.2, 1.7 | |||||||||

NOTE: P = referent person; R = respondent; N/A = not applicable; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; SD = standard deviation. Subjective norms distributions for all reference persons differ by race/ethnicity (p < .001); all race/ethnicity–subjective norms interactions p > .05. Statistically significant ORs and CIs are shown in boldface.

Recent screening (most recent mammogram within 15 months of interview).

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, months between surveys, study arm, baseline screening, age, education, non-English language, years in United States, marital status, income, insurance, regular doctor. All logistic regression analyses (n = 1,157).

For both longitudinal and cross-sectional comparisons, two multivariable models were created for each set of independent and dependent variables: one with only main effects for the construct and race/ethnicity and another that included an interaction between race/ethnicity and the construct to test for racial/ethnic differences in the association between the construct and receipt of mammography. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed for main effects and race/ethnicity-specific effects of constructs on mammography. Maximum-rescaled R2 was computed for the interaction models to assess the amount of variation explained. Statistical significance was set at the .05 level, two-sided.

RESULTS

An important finding across all constructs, with the exception of perceived susceptibility and, for the most part, subjective norms, is limited variability in responses. As shown in the “% Yes” column of Table 2, except for susceptibility, more than 80% of responses were yes (or agree), and they were often greater than 90%. This response characteristic almost certainly contributed to many of the large CIs found in the multi-variable results.

Intention

The longitudinal association between recent screening at the final survey and base-line intention (R2 = 23; see Table 2) was significant overall and among White women (OR = 5.0, 95% CI = 2.4, 10). The interaction between race/ethnicity and intention was statistically significantly (p = .020).

Self-Efficacy

For self-efficacy, the longitudinal association (R2 = .22) was also significant overall and for White women (OR = 3.5, 95% CI = 1.1, 11), but there was a nonsignificant interaction with race/ethnicity (p > .05).

Perceived Susceptibility

Perceived susceptibility (R2 = .21) did not have a significant association with screening overall or in any racial/ethnic group.

Perceived Benefits

Significant longitudinal associations with recent screening (see Table 2) were found for the perceived benefits of control over health overall and among Filipinas (OR = 7.1, 95% CI = 2.0, 26) and Whites (OR = 2.1, 95% CI = 1.0, 4.2; R2 = .22), for peace of mind overall and among African Americans (OR = 2.3, 95% CI = 1.0, 5.0) and Whites (OR = 3.2, 95% CI = 1.5, 7.1; R2 = .23), and for early detection overall and among African Americans (OR = 2.8, 95% CI = 1.0, 7.5; R2 = .22). The perceived benefits summary score had significant longitudinal associations with recent mammography overall and among African Americans (OR = 1.3, 95% CI = 1.0, 1.6), Filipinas (OR = 2.2, 95% CI =1.3, 3.8), and Whites (OR = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.1, 1.9; R2 = .23). The perceived benefit of good for family had a significant longitudinal association with screening in the total sample but not in any specific racial/ethnic group (R2 = .22). The perceived benefit of lower mortality was significant only among Filipinas (OR = 3.6, 95% CI = 1.1, 11; R2 = .22).

Subjective Norms

Significant cross-sectional associations with recent screening (see Table 3) were found for belief in annual mammography by the respondent’s best friend overall and among African American (OR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.0, 3.4) and White women (OR = 2.8, 95% CI = 1.3, 6.1; R2 = .23) and by most people important to her overall and among White women (OR = 3.4, 95% CI = 1.5, 7.9; R2 = .23). In addition, recent screening was associated with trying to comply with a belief in annual mammography by the respondent’s sister (R2 = .23) and doctor (R2 = .23) overall but in no specific racial/ethnic group and by people important to her only among Latinas (OR = 2.4, 95% CI = 1.2, 4.6; R2 = .23). There were no significant cross-sectional relationships between recent screening and subjective norms regarding the respondent’s mother (R2 = .21) or husband (R2 = .21). The subjective norms summary score had significant cross-sectional associations with recent mammography overall and among African Americans (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.0, 1.8), Latinas (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.0, 1.8), and Whites (OR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.4, 3.1; R2 = .23). There were no statistically significant racial/ethnic interactions in cross-sectional associations between screening and subjective norms measures.

DISCUSSION

Measures of intention, self-efficacy, perceived benefits, and subjective norms were significantly associated with mammography in this multiethnic cohort, overall and to some extent within racial/ethnic groups, and, with the exception of intention, racial/ethnic differences in association were not statistically significant. Therefore, the results here generally support the cross-cultural applicability of four of the five behavioral constructs to cancer screening, although they can raise questions about the validity and utility of standard questions. There is one important aspect of the data to recognize before discussing specific analyses. That is, because of the strong skew toward agreement with most of the behavioral constructs, there was a relatively small percentage (and therefore absolute number) of women who responded “no” or “don’t know.” This characteristic of the data almost certainly contributed to the very wide 95% CIs found within racial/ethnic groups for some constructs and thereby also reduced the likelihood of detecting racial/ethnic interactions with the behavioral constructs.

The longitudinal association between intention and recent mammography 2 years later was significant only among Whites, and the interaction term with race/ethnicity was statistically significant. Given the adjusted ORs in Table 2, it is clear that the interaction denotes the strong association for intention for Whites as the basis for the interaction result. Other studies have also found intention to be prospectively associated with mammography among middle-class U.S. White women (Han et al., 2007). Possible reasons for the lack of association in the other racial/ethnic groups in our study include lack of temporal stability of intentions and complexity translating intentions into actions (Ajzen, 2001) and the fact that our one-item measure was likely inadequate to measure the full spectrum of intention. The inductive study by Pasick, Barker, et al. (2009) found likely variations in the meaning of stated intention, examples of social environmental (social context) influences that directly affected behavior in the absence of intention (i.e., women obtained a mammogram without having formed the intention to do so), and situations where favorable intention conflicted with other influences and screening was not obtained. In addition, except among Whites, a rather large proportion of women reported a recent mammogram at the time of the final survey among those who did not intend to get one at baseline. In addition to the reasons outlined by Pasick et al., this may be because of participation in the study, which was specifically designed to address barriers to screening among African American, Latina, Chinese, and Filipina women.

There was a significant longitudinal association between baseline self-efficacy and recent mammography 2 years later only for White women. The test for racial/ethnic interaction was not significant, but the adjusted OR “point estimates” were clearly not the same across the racial/ethnic groups. As noted above, percentages of “% yes” were high, so that the 95% CIs were wide and overlapped for the racial/ethnic groups, and it was not surprising that a test for interactions did not yield significance. Here too our one-item measure may not have had sufficient specificity to determine which of these women actually felt able or unable to obtain mammograms. As noted by Ajzen (2001), the perceived difficulty of a behavior, which we did not assess, is more important than perceived behavioral control. This latter point appears compatible with Burke et al. (2009), whose inductive analysis suggested that self-efficacy was experienced and perceived differently depending on the social context, particularly with regard to poverty and migration. According to those authors, although self-efficacy theory acknowledges complex contextual influences, operationalization of this construct in mammography studies and interventions fails to adequately account for them, resulting in simplified understandings of how women make decisions about their health behavior and how to motivate them to change their health behaviors.

We did not find a positive longitudinal relationship between perceived susceptibility to breast cancer and mammography, overall or in any racial/ethnic group. Although meta-analyses have found on average a positive association between perceived risk and mammography (e.g., Katapodi et al., 2004), null associations have also been observed among Whites (Bowen, Alfano, McGregor, & Andersen, 2004), Chinese Americans (Wu & Yu, 2003), African Americans (Russell, Perkins, Zollinger, & Champion, 2006), and Latinas (Palmer, Fernandez, Tortolero-Luna, Gonzales, & Mullen, 2005). It is possible that our one-item measure of comparative susceptibility was inadequate to identify women who considered themselves at high risk for breast cancer. However, our measure was significantly associated with reporting a family history of breast cancer (data not shown), and there was considerable variation in response to the item. Each measure of perceived benefits predicted recent mammography among women overall, except for the benefit of lower mortality, which was significant only for Filipinas. In general, women responding yes to the benefit questions had a higher likelihood of a recent mammogram 2 years later. A smaller but still substantial percentage of women who responded no also had recent mammograms in that interval. Racial/ethnic interactions were not statistically significant. In a multiethnic cohort of older women (Glenn, Bastani, & Reuben, 2006), there was no association between getting a mammogram and either belief in the efficacy of early detection or the likelihood of surviving breast cancer after 5 years.

The inductive findings of Joseph, Burke, Tuason, Barker, and Pasick (2009) raise doubts about two assumptions inherent to the constructs of perceived susceptibility and perceived benefits: first, that people trust that the health care system will serve them effectively and, second, that people believe in and trust scientific principles and technical biomedical knowledge exclusively, over and above other healing beliefs and practices. In contrast to these assumptions, these authors conclude that beliefs about susceptibility to illness and benefits of preventive care are less significant or even antithetical in the face of worldviews that meld conscious and unconscious domains of social context into meanings of health and illness. Our cross-sectional analysis of subjective norms found screening to be associated with both normative beliefs and motivation to comply. Women who reported that their best friend or important people believed in annual mammography were more likely to have had a recent mammogram than those without such influences. Screening was also associated with trying to act on the beliefs of one’s sister or doctor, but the beliefs of one’s mother and husband were apparently not influential. A study including a multiethnic sample of inner-city women (Montaño, Thompson, Taylor, & Mahloch, 1997) found that past mammography was associated with subjective norms regarding one’s doctor, but not one’s family, friends, people in the news, or others in medicine. In our study, associations with screening did not differ significantly by race/ethnicity for subjective norms. In the 3Cs qualitative interviews, Pasick, Barker, et al. (2009) found support for the underlying assumption of subjective norms of the importance of significant others. However, their data suggested that many aspects of the operationalization of subjective norms are inconsistent with relational culture, “the processes of interdependence and interconnectedness among individuals and groups and the prioritization of these connections above virtually all else” (p. 95S). In particular, the emphasis on definable, expressible beliefs both on the part of a respondent and among her referents is likely to be more implicit rather than overtly discussed; and although pressure to comply is also plausible, it is more likely that a process of consultation leads to a joint conclusion. A novel ethnographic analysis that was part of the 3Cs study, conducted by Washington, Burke, Joseph, Guerra, and Pasick (2009), identified a potentially important but missing referent from the subjective norms construct as used in the United States, adult daughters, whose influence on their mothers emerged as important for mammography decision making, consistent with results from an adaptation of Montaño and Taplin’s (1991) items recently used in Spain (Andreu Vaillo, Galdón Garrido, Durá Ferrandis, Carretero Gómez, & Tuells Hernández, 2004).

Our models explained only a modest proportion of variation in mammography screening behavior, comparable to the adjusted R2 of .27 obtained in a model of mammography compliance as a function of HBM constructs (Aiken, West, Woodward, & Reno, 1994) and the R2 of .26 in a model of mammography participation as a function of TRA measures (Montaño & Taplin, 1991). However, as noted by Sheeran (2002), it is important to consider that correlations with a binary outcome may be low even for large differences in proportions.

The strengths of our study include the measurement of several behavioral constructs used by prominent theoretical models, inclusion of multiple racial/ethnic groups and languages, a large population-based sample, and a longitudinal design. The limitations of our study include low response rates among Chinese and Filipina women, lack of variation in socioeconomic status within racial/ethnic groups, timing of interviews that precluded determining if a woman had a mammogram within 12 months after baseline, possible intervention effects on the relationship between constructs and final screening status, single-item measures for three of the constructs, overlap of subjective norms referent categories, and the use of self-reported screening data. In spite of these limitations, we found significant positive associations between measures of four of our constructs and screening, overall and within racial/ethnic groups. It is possible, however, that there were racial/ethnic differences in associations that we were unable to detect because of lack of power. In particular, the measures of self-efficacy, intention, and perceived benefits all showed a lack of variation in response that produced small race/ethnic-specific cell sizes in some analyses. Therefore, it was possible to obtain a significant association in only one racial/ethnic group without finding significant racial/ethnic differences in association, as occurred with the perceived benefit of lower mortality.

Unfortunately, with these data it is virtually impossible to differentiate between the properties of the item and the properties of the construct itself. For instance, the lack of association between perceived susceptibility and mammography may be because of poor measurement or lack of relevance of this construct in relation to screening in this population. In addition, it is important to note that although measures of association can provide support for or against a hypothesized relationship, they cannot provide a complete explanation of the underlying mechanism. A more in-depth study is required to fully understand these constructs and determine whether better cross-cultural measures can be developed. Such a study would build on the inductive work described elsewhere in this volume and extend to the development of multi-item measures. The new measures would be evaluated through a variety of methods (Harkness, Van de Vijver, & Mohler, 2003), including cognitive interviewing, test–retest reliability assessment, and analytic techniques such as confirmatory factor analysis as well as further qualitative evaluation.

It could be argued that the development of widely applicable cross-cultural measures of these constructs is not only timely but also overdue. In recent years, measures of HBM constructs in relation to mammography have been used worldwide, chiefly through translations and adaptations of the Champion (1999) Health Belief Model Scale. Although these studies provide convincing evidence for the widespread applicability of these constructs, their findings are by no means uniform. Positive associations between perceived benefits and mammography were found among women in Spain (Andreu Vaillo et al., 2004), Turkey (Secginli & Nahcivan, 2006), Korea (Hur, Kim, & Park, 2005), and Israel (Soskolne, Marie, & Manor, 2007). However, other studies found no association with mammography among women in Spain (Lostao, Joiner, Pettit, Chorot, & Sandín, 2001), Turkey (Avci & Kurt, 2008), Korea (Ham, 2006), and Israel (Azaiza & Cohen, 2006). Similar inconsistencies have been found with respect to the associations between mammography and both self-efficacy and, as noted above, perceived risk. Such promising, yet variable, findings call for a deeper understanding of the cultural and social contexts of health beliefs and behaviors as well as the development of measures that incorporate this understanding.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Measures for these constructs are imperfect because they are not specific enough to identify the majority of women who do not get screened and because their meaning, as intended by theory, may not apply comparably across ethnic groups. It is important to keep in mind that many women who report that they are able to get a mammogram, intend to get a mammogram, and recognize the benefits of mammography are nevertheless not getting regular mammograms. These constructs are now being measured in various population groups around the world. Therefore, it is imperative to develop improved measures of perceived benefits, perceived susceptibility, self-efficacy, subjective norms, and intention that are cross-culturally valid, reliable, and capable of discerning those in need of health promotion interventions.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (Grants RO1CA81816 and P01CA55112, R. Pasick, principal investigator).

This supplement was supported by an educational grant from the National Cancer Institute, No. HHSN261200900383P.

Contributor Information

Susan L. Stewart, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, San Francisco.

William Rakowski, Department of Community Health, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

Rena J. Pasick, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, San Francisco.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG, Woodward CK, Reno RR. Health beliefs and compliance with mammography-screening recommendations in asymptomatic women. Health Psychology. 1994;13(2):122–129. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:27–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JD, Sorensen G, Stoddard AM, Colditz G, Peterson K. Intention to have a mammogram in the future among women who have underused mammography in the past. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:474–488. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreu Vaillo Y, Galdón Garrido MJ, Durá Ferrandis E, Carretero Gómez S, Tuells Hernández J. Age, health beliefs, and attendance to a mammography screening program in the community of Valencia. Revista Española de Salud Pública. 2004;78(1):65–82. doi: 10.1590/s1135-57272004000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avci IA, Kurt H. Health beliefs and mammography rates of Turkish women living in rural areas. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2008;40(2):170–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azaiza F, Cohen M. Health beliefs and rates of breast cancer screening among Arab women. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15(5):520–530. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Alfano CM, McGregor BA, Andersen MR. The relationship between perceived risk, affect, and health behaviors. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2004;28:409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke NJ, Bird JA, Clarke MA, Rakowski W, Guerra C, Barker JC, et al. Social and cultural meanings of self-efficacy. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36 Suppl. 1:111S–128S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion VL. Revised susceptibility, benefits, and barriers scale for mammography screening. Research in Nursing Health. 1999;22:341–348. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199908)22:4<341::aid-nur8>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Houlihan A. [Retrieved October 31, 2007];Perceived vulnerability. 2007 from http://dccps.cancer.gov/brp/constructs/perceived_vulnerability/index.html.

- Glenn B, Bastani R, Reuben D. How important are psychosocial predictors of mammography receipt among older women when immediate access is provided via on-site service? American Journal of Health Promotion. 2006;20(4):237–246. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.4.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham OK. Factors affecting mammography behavior and intention among Korean women. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2006;33(1):113–119. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han PK, Kobrin SC, Klein WM, Davis WW, Stefanek M, Taplin SH. Perceived ambiguity about screening mammography recommendations: Association with future mammography uptake and perceptions. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2007;16(3):458–466. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness JA, Van de Vijver FJR, Mohler PP. Cross-cultural survey methods. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt RA, Pasick RJ, Stewart S, Bloom J, Davis P, Gardiner P, et al. Community-based cancer screening for underserved women: Design and baseline findings from the Breast and Cervical Cancer Intervention Study. Preventive Medicine. 2001;33(3):190–203. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur HK, Kim GY, Park SM. Predictors of mammography participation among rural Korean women age 40 and over. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2005;35(8):1443–1450. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2005.35.8.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph G, Burke NJ, Tuason N, Barker JC, Pasick RJ. Perceived susceptibility to illness and perceived benefits of preventive care: An exploration of behavioral theory constructs in a transcultural context. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36 Suppl. 1:71S–90S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katapodi MC, Lee KA, Facione NC, Dodd MJ. Predictors of perceived breast cancer risk and the relation between perceived risk and breast cancer screening: A meta-analytic review. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38:388–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK, Jepson C, Brody D, Boyce A. Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening. Health Psychology. 1991;10(4):259–267. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.4.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lostao L, Joiner TE, Pettit JW, Chorot P, Sandín B. Health beliefs and illness attitudes as predictors of breast cancer screening attendance. European Journal of Public Health. 2001;11(3):274–279. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/11.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaño DE, Kasprzyk D. The theory of reasoned action and theory of planned behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Montaño DE, Taplin SH. A test of an expanded theory of reasoned action to predict mammography participation. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32(6):733–741. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaño DE, Thompson B, Taylor VM, Mahloch J. Understanding mammography intention and utilization among women in an inner city public hospital clinic. Preventive Medicine. 1997;26:817–824. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RC, Fernandez ME, Tortolero-Luna G, Gonzales A, Mullen PD. Correlates of mammography screening among Hispanic women living in lower Rio Grande Valley farmworker communities. Health Education & Behavior. 2005;32:488–503. doi: 10.1177/1090198105276213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Barker JC, Otero-Sabogal R, Burke NJ, Joseph G, Guerra C. Intention, subjective norms, and cancer screening in the context of relational culture. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36 Suppl. 1:91S–110S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Burke NJ, Barker JC, Joseph G, Bird JA, Otero-Sabogal R, et al. Behavioral theory in a diverse society: Like a compass on Mars. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36 Suppl. 1:11S–35S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Sabogal F, Bird JA, D’Onofrio CN, Jenkins CNH, Lee M, et al. Problems and progress in translation of health survey questions: The Pathways experience. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23 Suppl.:S28–S40. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers K. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski W, Fulton JP, Feldman JP. Women’s decision-making about mammography: A replication of the relationship between stages of adoption and decisional balance. Health Psychology. 1993;12(3):209–214. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RW. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In: Cacioppo JT, Petty RE, editors. Social psychophysiology: A sourcebook. New York: Guilford; 1983. pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Russell KM, Perkins SM, Zollinger TW, Champion VL. Sociocultural context of mammography screening use. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2006;33(1):105–112. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Luszczynska A. [Retrieved October 31, 2007];Perceived self-efficacy. 2007 from http://dccps.cancer.gov/brp/constructs/self-efficacy/index.html.

- Secginli S, Nahcivan NO. Factors associated with breast cancer screening behaviours in a sample of Turkish women: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006;43:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P. Intention–behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology. 2002;12:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner CS, Champion VL, Gonin R, Hanna M. Do perceived benefits and barriers vary by mammography stage? Psychology, Health & Medicine. 1997;2(1):65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RA, Saslow D, Sawyer KA, Burke W, Costanza ME, Evans WP, III, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening: Update. CA: Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2003;53:141–169. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.3.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somkin CP, McPhee SJ, Nguyen T, Stewart S, Shema SJ, Nguyen B, et al. The effect of access and satisfaction on regular mammogram and Papanicolaou test screening in a multiethnic population. Medical Care. 2004;42(9):914–926. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000135832.28672.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soskolne V, Marie S, Manor O. Beliefs, recommendations and intentions are important explanatory factors of mammography screening behavior among Muslim Arab women in Israel. Health Education Research. 2007;22(5):665–676. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waksberg J. Sampling methods for random digit dialing. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1978;73:40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wang JH, Liang W, Schwartz MD, Lee MM, Kreling B, Mandelblatt JS. Development and evaluation of a culturally tailored educational video: Changing breast cancer-related behaviors in Chinese women. Health Education & Behavior. 2008;35:806–820. doi: 10.1177/1090198106296768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington PK, Burke NJ, Joseph G, Guerra C, Pasick RJ. Adult daughters’ influence on mothers’ health-related decision making: An expansion of the subjective norms construct. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36 Suppl. 1:129S–144S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein ND, Sandman PM. The precaution adoption process model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wu TY, Yu MY. Reliability and validity of the Mammography Screening Beliefs Questionnaire among Chinese American women. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26(2):131–142. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]