Abstract

The current study examined whether negative interactions with parents and peers would mediate the longitudinal association between perceived social competence and depressive symptoms and whether a negative cognitive style would moderate the longitudinal association between negative interactions with parents and increases in depressive symptoms. Youth (N=350; 6th-10th graders) completed self-report measures of perceived social competence, negative interactions with parents and peers, negative cognitive style, and depressive symptoms at three time points. Results indicated that the relationship between perceived social competence and depressive symptoms was partially mediated by negative interactions with parents but not peers. Further, baseline negative cognitive style interacted with greater negative parent interactions to predict later depressive symptoms.

Perceived Social Competence, Negative Social Interactions and Negative Cognitive Style Predict Depressive Symptoms during Adolescence

Depression is one of the most common psychiatric disorders during adolescence (Abela & Hankin, 2008; Costello, Egger, & Angold, 2005; Williamson, Forbes, Dahl, & Ryan, 2005). The point prevalence rate of major depressive disorder during adolescence is approximately 5% (Lewinsohn, Rohde, Klein, & Seeley, 1999; Shaffer et al., 1996) and rises sharply during mid-to-late adolescence (Hankin et al., 1998), with adolescent lifetime prevalence rates ranging between 15% to 20%. Additionally, rates of recurrence during adolescence are similar to rates found in adult populations: approximately 40% within 2 years (Birmaher et al., 2004) and 70% within 5 years (Birmaher et al., 1996). The high prevalence and recurrence rates are of particular concern as adolescent depression has been associated with poor outcomes, such as negative life events (e.g., Adrian & Hammen, 1993; Davila, Hammen, Burge, Paley, et al., 1995), poor interpersonal functioning (Hammen and Brennan, 2002; Rudolph, Hammen, Burge, Lindberg, Herzberg, Daley, 2000), substance abuse (Whitmore et al., 1997), co-morbidity with other psychiatric disorders (Angold, Costello & Erkanli, 1999), and suicide (Nock & Kazdin, 2002).

Both cognitive theories of depression (e.g., Hopelessness Theory of Depression; HT, Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989) and interpersonal approaches to depression (e.g., Coyne, 1976; Joiner, & Coyne, 1999) have been used to explain the development and maintenance of depression. Interpersonal approaches focus on examining how relationship dynamics affect mood, whereas cognitive theories focus on how interpretations of events affect mood. However, integrating both interpersonal and cognitive perspectives offers a more powerful and contextual approach for understanding the effect of negative interpretations of interpersonal events on mood. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to examine interpersonal and cognitive vulnerability factors in the prediction of depressive symptoms. Specifically, we examined the impact of perceived social competence, negative interpersonal interactions with parents and peers, and negative cognitive style as predictors of depressive symptoms during adolescence.

Social Competence, Psychological Adjustment, and Interaction Quality

Perceived social competence, defined as perceptions of one's own ability to engage in effective social interactions (Anderson & Messick, 1974), is associated with resilience (Childs, Schneider, & Dula, 2001) and positive adjustment (Chen, Liu, Rubin, Cen, Gao, & Li, 2002; Lengua, 2003; Peters, 1988), whereas low levels of perceived social competence are associated with current (Hammen, Shih & Brennan, 2004; Harter & Whitesell, 1996; Rudolph & Clark, 2001) and later (Cole et al., 1996) depressive symptoms, as well as suicidal ideation (Sourander, Helstela, Haavisto, & Bergroth, 2001). In fact, perceived social competence is negatively associated with mental health disorders in general (McGee & Stanton, 1992), as well as risk for multiple mental health disorders (McGee et al., 1990).

In addition, perceived social competence is related to both quantitative and qualitative aspects of interactions with others. Evidence suggests that perceived social competence is associated with the size of one's social network (Bierman & McCauley, 1987), as well as negative interactions and conflict (Grisset & Norvell, 1992). This ability to interact skillfully with others to achieve one's goals or needs, and the ability to communicate clearly, allows individuals to experience positive interactions and resolve conflicts effectively. Further, not only is perceived social competence related to the quality of interactions with others, but it is also related to the ability to create and maintain social support (Ciarrochi et al., 2003; Fenzel, 2000), which ostensibly provides more opportunities for a greater number of social interactions. Thus, perceived social competence is negatively associated with poor adjustment and psychological symptoms, as well as associated with both quality (positive and negative) and quantity of interactions. Because perceptions of social competence are associated with psychological adjustment and have been shown to predict later depression (e.g., Cole, Martin, Powers, & Truglio, 1996), the current study examined perceptions of social competence rather than ‘objective’ social competence (e.g., other informants). In this light, perceived social competence has been conceptualized as both an interpersonal risk factor and a cognitive risk factor for depression, as evidence suggests that child reports of social competence reflect both skill-deficit and cognitive distortion models of depression (Rudolph and Clark, 2001).

Stress: Negative Interactions in Parent and Peer Relationships

Prior research indicates that chronic stressors predict depression more strongly than discrete stressors (Avison & Turner, 1988; Billings & Moos, 1984; Hammen, 2005; McGonagle & Kessler, 1990; Monroe, Slavich, Torres, & Gotlib, 2007). This suggests that examining chronic stressors may offer a better understanding of the development and course of depression. While negative interactions have been shown to be associated generally with depressed mood (Rudolph, Flynn, & Abaied, 2008), on-going negative interactions within specific relationships may potentially be better predictors of depressive symptoms, as chronic negative interactions in important and significant relationships are presumably the most distressful interactions.

For many adolescents, parents continue to play a significant role in their lives (Steinberg, 2001). Relationships with parents often involve a power differential and reliance not present to the same degree in peer relationships (Hunter & Youniss, 1982). In addition, the length, frequency and intensity of the relationship with parents also generally differ from relationships with peers. Given the importance of parent-youth relationships, as well as the developmental changes that occur from childhood to adolescence, we examined the relative importance of adolescent relationships with parents versus peers (Steinberg et al., 2006) in predicting depressive symptoms.

Few studies have compared the relative predictive power of negative peer versus parent interactions as prospective predictors of later depressive symptoms. Allen et al. (2006) examined dysfunctional interaction patterns with mothers versus with a close friend and found that each contributed unique explanatory power in the prediction of prospective increases in depressive symptoms in 13-year-olds (though dysfunctional interactions with mothers predicted somewhat more variance than dysfunctional interactions with a close friend). Although Allen and colleagues examined qualities and patterns of relatedness (i.e., degree of autonomy and hostility in relationship with mother; degree of dependent, hostile and withdrawn behavior in relationship with close friend), and not conflict per se, their findings suggest that negative interaction patterns with both mothers and a close friend predict later depressive symptoms. Moreover, Stice, Ragan, and Randall (2004) examined parent versus peer perceived support in relation to depression in adolescents, and found that perceived lack of parent support predicted later depression, whereas initial depression predicted later decreases in perceived peer support. However, Allen and colleagues and Stice and colleagues examined dysfunctional interaction patterns and lack of support, respectively, but not the presence of conflict; the current study examined the presence of conflict with parents and peers in the prediction of depressive symptoms.

To summarize, individuals with low levels of perceived social competence have poor social skills or other interpersonal deficits. These interpersonal deficits are hypothesized to lead to increased levels of negative interactions and conflict with both peers and parents. Such ongoing negative interactions in the context of important and long-standing relationships (i.e., parent-adolescent relationship), conceptualized in the current study as chronic stressors, likely lead to depressive symptoms. Thus, we hypothesized that negative social interactions would mediate the association between (low) perceived social competence and depressive symptoms. Specifically, we posited that chronic negative interactions with parents would predict depressive symptoms more powerfully than chronic negative interactions with peers, given the relative importance of parent-youth relationships during adolescence, as the few prior studies in this area suggest that chronic stress or lack of support from parents appears to predict depressive symptoms relatively more strongly than does chronic peer interactions.

Cognitive Theories of Depression

Although there is a fairly well-established association between negative interactions and depression (e.g., La Greca & Harrison, 2005; Zlotnick et al., 2000), depressive symptoms may be more easily triggered by chronic stress when a pre-existing vulnerability, such as a negative cognitive style, is present. Most cognitive theories of depression are vulnerability-stress models that posit that an individual's cognitive interpretations of negative environmental contexts, such as chronic stress with parents, affect mood and behaviors. One major cognitive theory of depression, the Hopelessness Theory of Depression (HT; Abramson et al., 1989), defines a depressogenic cognitive style as the tendency to attribute a negative event to stable and global causes, to infer that the negative event will likely lead to other negative consequences, and to view the negative event as an indication of (lowered) self-worth. Abramson and colleagues hypothesized that these negative inferences about the self moderate the association between stress and prospective increases in depressive symptoms. HT posits that the interaction of stress and negative cognitive style predicts an elevated likelihood of depressed mood, particularly among those individuals who exhibit high levels of cognitive vulnerability (i.e., depressogenic cognitive style) to depression. Research has consistently shown that a depressogenic cognitive style, especially in the context of stressful events, can predict later depression among adolescents (e.g., Abela, 2001; Cole et al., 2008; Hankin, 2008b; Hankin & Abramson, 2001; see reviews by Abela & Hankin, 2008; Lakdawalla, Hankin, & Mermelstein, 2007) and adults (Abramson et al., 2002; Haeffel et al. (2008).

The Current Study

In the current study, we tested two main hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that negative interpersonal interactions, especially those with parents relative to peers, would partially mediate the association between perceived social competence and prospective increases in depressive symptoms. Second, we hypothesized that a negative cognitive style would moderate the longitudinal association between greater negative interactions with parents and future increases in depressive symptoms. Specifically, applying HT as a cognitive vulnerability-stress model within a moderated-mediation framework (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007), we hypothesized that youth with perceptions of low social competence would be more likely to experience negative interactions, especially with parents, and that those adolescents with a more negative cognitive style who experience more negative interactions with parents (i.e., a cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction) would be the most likely to exhibit prospective increases in depressive symptoms over time.

Negative cognitions were hypothesized to be triggered by stress, and many adolescents experience a significant amount of stress around family and peers. Evaluating both cognitive and interpersonal risk factors in adolescents is likely to provide increased explanatory power in predicting prospective increases in depressive symptoms. Testing an integrated model of cognitive and interpersonal vulnerabilities allows for an examination of potential synergistic effects of multiple vulnerabilities beyond the isolated effects of examining vulnerability to depression from one perspective alone.

To test these hypotheses, we used a 3-wave prospective design and analyzed measures of perceived social competence at baseline, negative cognitive style at baseline, changes in negative interactions with parents and peers from Time 1 to Time 2, and changes in depressive symptoms from baseline to Time 3, among early and middle adolescents. Assessing these constructs at different time points across time enabled a stronger test of mediation hypotheses (Cole & Maxwell, 2003).

Methods

Participants

Participants were adolescents recruited from five Chicago area schools (N = 350; 54.6% girls). A total of 467 students in the 6th-10th grades were eligible and were invited to participate. A total of 390 adolescents provided active parental consent and were willing to participate; 356 completed the baseline questionnaire, and the remaining 34 were absent from school and were unable to reschedule. Thus, the recruitment rate was 83.5%. We examined data from 350 adolescents who provided complete data at baseline (90% participation). The age range was 11-17 years (M = 14.5; SD = 1.4). Approximately 53% participants identified themselves as White, 21% as African-American, 13% as Latino, 7% as bi-racial or multi-racial, and 6% as Asian or Pacific Islander. Rates of participation in the study decreased slightly at subsequent assessments: Time 2 (N = 303; 86%) and Time 3 (N = 308; 88%). Youth who participated at Time 1 but were not present at other time points did not differ significantly on any of the measures from those youth who remained at all time points.

Procedures

Research assistants and graduate students visited classrooms in the schools and briefly described the study to students, and letters describing the study to parents were sent home with the students. Specifically, students and parents were told that this study was about adolescent mood and experiences and would require completion of questionnaires. Written consent was required from both students and their parents. Permission to conduct this investigation was provided by the school districts and their institutional review boards, school principals, individual classroom teachers, and the university institutional review board.

Participants completed self-report measures of perceived social competence, negative interactions, negative cognitive style, and depressive symptoms at three time points, with approximately five weeks between each time point. The spacing for the follow-up intervals was chosen based on past research (e.g., Hankin, Abramson, & Siler, 2001) that found cognitive vulnerability predicted prospective depressive symptoms using a 5-week follow-up. In addition, we wanted to follow symptoms over a relatively short time-frame for accurate recall of symptoms (see Costello, Erkanli, & Angold, 2006, for evidence that shorter time-frames provide more accurate, less biased findings). Participants were compensated up to a possible total of $40 for their participation at all waves. Different measures were given at each of the time points, as described next. The current study examines data from the three time points (T1, T2, and T3).

Measures

Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985)

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI), a self-report measure that assesses depressive symptoms in children and adolescents using 27 items. Each item is rated on a scale from 0-2, with the total score ranging from 0-54. Higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. Internal consistency in this sample was α = .90 at Time 1. The CDI has been shown to have good reliability (internal consistency and test-retest) and there is evidence to support its validity in assessing depression in adolescents (Craighead, Curry, & Ilardi, 1995; Klein, Dougherty, & Olino, 2005; Kovacs, 1985; Smucker, Craighead, Craighead, & Green, 1986). The CDI was administered at T1, T2, and T3.

Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire (ACSQ; Hankin & Abramson, 2002)

The ACSQ is a modification of the Cognitive Style Questionnaire (CSQ; Haeffel et al., 2008). The ACSQ measures the inferences about cause, consequence, and self, as featured in HT. The ACSQ presents negative hypothetical events in achievement and interpersonal domains and asks the subject to make causal inferences (internal-external, stable-unstable, and global-specific). Additionally, the ACSQ assesses inferred consequences and inferred characteristics about the self. Each item dimension is rated from 1-7. Reported scores are means of all items. Internal consistency in this sample was α = .95 at Time 1. The ACSQ has demonstrated excellent internal consistency and good test-retest reliability and there is evidence to support its validity as a measure of cognitive vulnerability to depression for use with adolescents (Hankin, 2008a, b). The ACSQ was administered at T1.

Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC; Harter, 1985) (Social competence subscale only)

The Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC), a multi-dimensional measure of children's perceived competencies, was used to assess perceptions of social competence. The SPPC utilizes a structured alternative format in which the child is asked to choose between two choices (e.g., “Some kids find it hard to make friends BUT Other kids find it's pretty easy to make friends.”) and then is asked to decide whether that descriptor is “really true” or “sort of true” for him or her. Reported scores are means of all items. Internal consistency in this sample was α = .82. The SPPC has been shown to have good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and there is evidence to support its validity (concurrent and convergent) as measure of perceived social competence (e.g., Harter, 1999; Muris, Meesters, & Fijen, 2003; Winters, Myers, & Proud, 2002). The SPPC was administered at T1 and T2.

Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI; Furman & Buhrmester, 1985)

The NRI assesses the quality of family and peer relationships. The NRI asks the participant to report on both positive and negative interactions with family members and peers. The child is asked to answer a question (e.g., “How much do you and this person get upset with or mad at each other?”) by rating the frequency of conflict (i.e., “Little or none; Somewhat; Very much; Extremely much; The most) for each family member (mother, father, sibling) and peer (boy/girlfriend, same-sex friend, opposite sex friend). Reports on mother and father were collapsed to form the Parent grouping, and reports on boy/girlfriend, same-sex friend, and opposite-sex friend were collapsed to form the Peer grouping. This measure is comprised of 12 items, with each item rated on a 5-point scale. Reported scores are means of all items. Factor analyses indicate that there are two broad factors that can be categorized as social support and negative interactions (Adler & Furman, 1988). Only the negative interaction items were examined in the current study. At Time 2, internal consistency was α = .88 for parents and α = .86 for peers. The NRI was administered at T1, T2, and T3.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive analyses (means, standard deviations and correlations) of the main variables (SPPC T1, ACSQ T1, NRI T2, CDI T1 and CDI T3) are presented in Table 1.1 All variables were moderately correlated with each other in the expected directions. Depressive symptoms were positively correlated with lower levels of perceived social competence, higher levels of negative interactions, and higher levels of negative cognitive style. Perceived social competence was negatively correlated with negative interactions and negative cognitive style. Negative interactions was positively correlated with negative cognitive style.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations of Main Variables

| CDI T1 | CDI T3 | SPPC T1 | NRI Total T2 | NRI Parent | NRI Peer T2 | ACSQ T1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDI T1 | 1.00 | ||||||

| CDI T3 | .673** | 1.000 | |||||

| SPPC T1 | -.387** | -.285** | 1.000 | ||||

| NRI Total T2 | .415** | .405** | -.109* | 1.000 | |||

| NRI Parent | .441** | .472** | -.125* | .901** | 1.000 | ||

| NRI Peer T2 | .262** | .202** | -.057 | .834** | .514** | 1.000 | |

| ACSQ T1 | .430** | .405** | -.257** | .337** | .342** | .233** | 1.000 |

| Mean | 12.80 | 12.26 | 2.761 | 1.950 | 2.177 | 1.703 | 3.370 |

| SD | 8.64 | 9.27 | .574 | .405 | .658 | .344 | 1.193 |

Note. CDI = Child Depression Inventory. SPPC = Self-Perception Profile for Children. NRI = Network of Relationships Inventory. ACSQ = Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire.

p<.05.

p<.01.

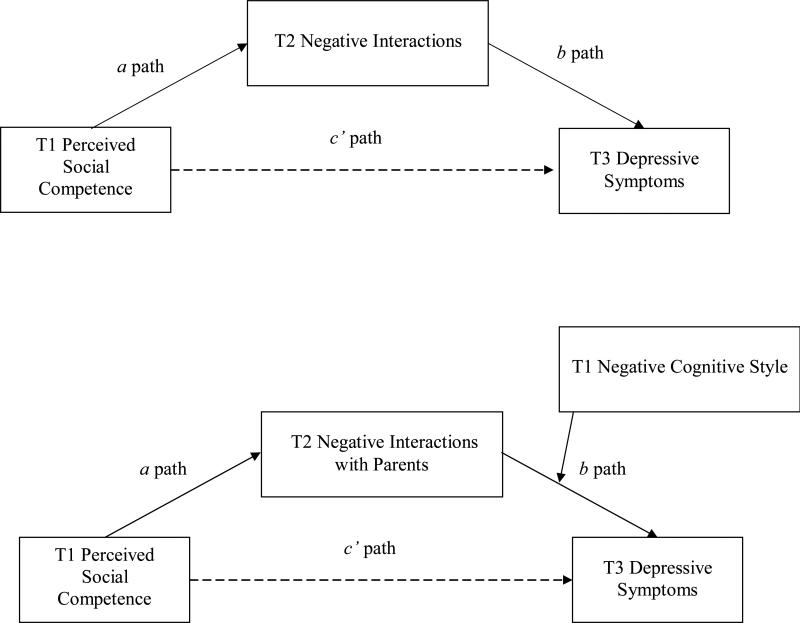

Mediation Analyses

The bootstrap procedure (Shrout & Bolger, 2002) was used to investigate whether negative interactions mediated the relationship between perceived social competence and depressive symptoms. This bootstrap procedure, which mediation methodologists (e.g., MacKinnon et al., 2004; Shrout & Bolger, 2002) recommend over the traditional Baron and Kenny (1986) approach to testing mediation or using the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982), uses a resampling approach to generate an empirical distribution for significance testing of mediation. This bootstrap approach has fewer assumptions with respect to the distribution of the mediated, indirect effect, which tends to be excessively conservative when tested via the Sobel test, and produces more accurate confidence intervals (MacKinnon et al., 2004; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). In addition, methodologists (Cole & Maxwell, 2003) recommend the use of multiple waves of longitudinal data in which the different predictors and outcome variable are assessed at different, non-overlapping time points in order to provide the most powerful and appropriate test of mediation. In the present study, we followed this recommendation and assessed the predictors (perceived social competence and negative interactions) and the dependent variable (depressive symptoms) at different time points so that we could evaluate the proposed mediational hypotheses more accurately and with less bias compared with the usual study design in which predictors and outcome are assessed at the same, concurrent time point (Maxwell & Cole, 2007). Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual mediation model that we tested with the key variables assessed at different time points. Baseline depressive symptoms, as well as prior wave assessments necessary to examine change in the mediator (e.g., T1 NRI to analyze change in negative interactions from T1 to T2) and change in the outcome (i.e., T2 CDI to examine how changes in NRI from T1 to T2 predicted changes in CDI from T2 to T3) were included in all models. We used AMOS 16.0 (Arbuckle, 2006) to conduct mediation analyses within a path analysis framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual figure illustrating the proposed mediation models tested. Top half shows negative interactions as the mediator of the association between perceived social competence and change in depressive symptoms. Bottom half shows the moderated mediation model in which baseline negative cognitive style is hypothesized to moderate the longitudinal relation between negative parent interactions and increases in depressive symptoms. In analyses for both models, initial depressive symptoms (not shown in figure for clarity) were controlled to test prospective prediction of depressive symptoms. See text for full details.

We first examined whether T1 perceived social competence predicted depressive symptoms at T3, after controlling for T1 depressive symptoms. Perceived social competence significantly predicted T3 depressive symptoms (β = -.094, SE= .026, t= -2.3, p = .035). This effect was not moderated by sex (β = .05, t= .56, p = .65) or age (β = -.33, t= -.77, p = .44), so all ensuing analyses used the entire sample to examine our main questions concerning which processes mediate the association between baseline perceived social competence and later changes in depressive symptoms.

We first tested mediation by negative interactions with parents and then by negative interactions with peers (Hypothesis 1). The results for negative interactions with parents mediating the longitudinal association between T1 perceived social competence and T3 depressive symptoms, after controlling for baseline depressive symptoms, is shown in Table 2. We used the bootstrap procedure with 2,000 resamples. This model provided a reasonable fit to the data: χ2 (3) = 32.82, p < .05; CFI = .96, RMSEA = .06. We also examined whether sex or age moderated the mediational models using multi-group analyses in SEM. No evidence was obtained for moderation by sex or age, so results are presented for the whole sample.

Table 2.

Mediation Analyses of Negative Interactions Accounting for the Longitudinal Association between Perceived Social Competence (T1) and Depressive Symptoms (T3) after Controlling for T1 and T2 Depressive Symptoms

| Effect | Standardized Estimate | SE | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Interactions with Parents | ||||

| c path | -.094 | .026 | (-.15,-.04) | .035 |

| a path | -.132 | .076 | (-.33, -.03) | .015 |

| b path | .11 | .018 | (.07, .14) | .001 |

| a × b | -.02 | .009 | (-.04, -.005) | .01 |

| c'path | -.059 | .024 | (-.11, .04) | .16 |

| Negative Interactions with Peers | ||||

| c path | -.094 | .026 | (-.15,-.04) | .035 |

| a path | -.04 | .053 | (-.13, .04) | .39 |

| b path | .01 | .041 | (-.05, .08) | .76 |

| a × b | .00 | .003 | (-.008, .002) | .59 |

| c'path | -.03 | .042 | (-.10, .04) | .47 |

First, the direct effect (c path) of initial perceived social competence to T3 CDI, after controlling for T1 CDI, was significant. Second, the a effect (perceived social competence at T1 predicting negative interactions at T2 after controlling for T1 negative interactions and T1 CDI), as well as the b effect (change in negative interactions from T1 to T2 predicting T3 CDI after controlling for T1 and T2 CDI), were both significant. Third, the 95th percentile bias-corrected confidence interval for the mediated effect ranged between -.04 and -.005. As this confidence interval does not include zero, the mediation effect (a x b) was significant (estimated p = .01). Finally, the direct effect of perceived social competence on later depressive symptoms (c path) was reduced (from β = -.09, p < .05, to β = -.06, ns) after including negative interactions with parents as the mediator (c’ path). Inclusion of negative interactions with parents explained 37% of the association between perceived social competence and change in depressive symptoms. This is most consistent with partial mediation.

The results for the same set of mediation analyses for negative interactions with peers is shown in the bottom half of Table 2. No evidence was obtained to suggest that conflict with peers functioned as a mediator of the association between perceived social competence and later depressive symptoms because neither path a (perceived social competence predicting negative interactions with peers) nor the mediated effect (path a x b) was significant. We also examined whether sex or age moderated the peer model using multi-group analyses in SEM. The constrained models, both for sex and age, did not provide a better fit compared with the unconstrained model, suggesting that neither sex nor age affected the results for the whole sample. Last, given the overlap between negative interactions with peers and parents, we analyzed whether conflict with parents uniquely predicted later depressive symptoms after controlling for negative peer interactions. We ran this analysis with both NRI parent and NRI peer interactions entered in the same regression, and NRI parent was significant (β = .260, t = 5.420, p < .001) but NRI peer was not (β = -.081, t = -1.823, p = .069). Thus, this is consistent with our prior results.2

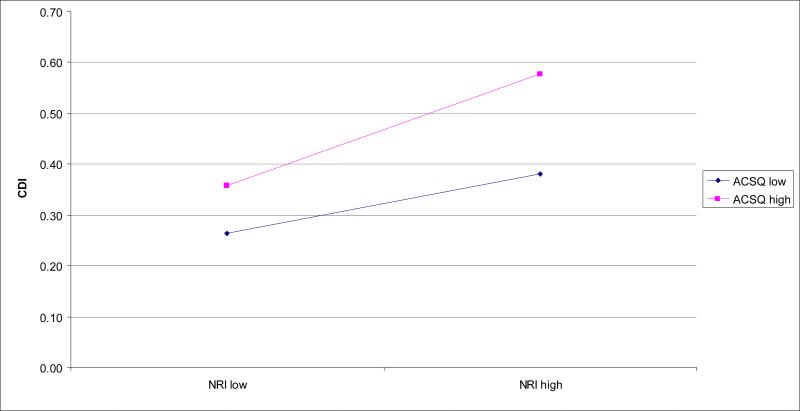

Finally, testing the moderated mediation model (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007), we hypothesized that baseline negative cognitive style would moderate the longitudinal association between more negative interactions with parents from T1 to T2 and prospective elevations in depressive symptoms, such that those youth with higher levels of negative cognitive style and higher levels of negative interactions with parents would report the highest level of depressive symptoms. This moderated mediation model provided a reasonable fit to the data: χ2 (4) = 14.05, p < .05; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .05. Using the bootstrap procedure with 2,000 resamples, analyses revealed that the a effect (T1 perceived social competence predicting changes in negative interactions with parents from T1 to T2 after including all additional necessary control variables) was significant (β = -.13, SE = .07, 95% CI -.33 to -.03, p = .015). Likewise, the b effect (the interaction of T1 negative cognitive style × T2 negative interactions with parents predicting T3 CDI, after controlling T1 and T2 CDI and T1 NRI) was significant (β = .20, SE = .06, 95% CI .50 to .03, t= 4.77, p < .001). The inclusion of negative cognitive style × negative interactions with parents as a mediator (a x b) was significant, as the 95% confidence interval did not contain zero (β = -.06, SE = .02, 95% CI -.11 to -.03, estimated p value = .001). Finally, after including negative cognitive style × negative interactions with parents in the model, the direct effect of perceived social competence on later depressive symptoms was reduced (c path of β = -.09, p < .05, to the c’ path of β = -.02, ns), and negative cognitive style × negative interactions with parents explained 75% of the association between perceived social competence and change in depressive symptoms. This is most consistent with partial mediation. Finally, we examined whether sex or age moderated this mediated-moderation model using multi-group analyses in SEM. The constrained models, both for sex and age, did not provide a better fit compared with the unconstrained model, suggesting that neither sex nor age affected the main mediated moderation results for the whole sample.

The results of the negative parent interactions × negative cognitive style interaction were graphed according to recommendations (Cohen et al., 2003) of inserting values (+1 S.D./-1 S.D.) above and below the means for the ACSQ (negative cognitive style) and NRI (negative parent interactions). As shown in Figure 2, for adolescents who reported low levels of negative parent interactions, high levels of negative cognitive style did not appear to have an effect on depressive symptoms. However, for adolescents who reported high levels of negative parent interactions, high levels of negative cognitive style predicted the highest levels of depressive symptoms.

Figure 2.

Negative Interactions with Parents × Negative Cognitive Style Interaction Predicting Depressive Symptoms

Note. CDI = Child Depression Inventory. NRI = Network of Relationships Inventory. ACSQ = Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire.

Additional Analyses

We also analyzed potential alternative mediational pathways among the main variables because it is conceivable that other temporal orderings and possible reverse causal directions among the variables across time could be supported. We examined whether perceived social competence, instead of negative interactions, might mediate some of these relationships. First, we examined whether perceived social competence mediated the NRI parent → depressive symptoms association, because a history of negative social interactions could contribute to lower perceived social competence due to missed opportunities to learn adaptive social skills, which in turn, would predict later depressive symptoms. After controlling for initial levels of depressive symptoms, the T1 NRI parent → T3 CDI path was significant (β = .608, t = 13.609, p < .001). The T1 NRI parent → T2 SPPC path was also significant (β = -.216, t = -4.134, p < .001). However, after controlling for initial levels of depressive symptoms and including T1 NRI parent, the T2 SPPC → T3 CDI path was not significant (β = -.059, t = -1.396, p = .164). We also examined whether perceived social competence mediated the negative cognitive style → depressive symptoms association, because negative cognitions may lead to negative appraisals of social competence, which in turn may predict later depressive symptoms. After controlling for initial levels of depressive symptoms, the T1 ACSQ → T3 CDI path was significant (β = .142, t = 3.283, p < .001). The T1 ACSQ → T2 SPPC path was also significant (β = -.231, t = -4.425, p < .001). However, after controlling for initial levels of depressive symptoms and including T1 ACSQ, the T2 SPPC → T3 CDI path was not significant (β = -.053, t = -1.267, p = .206).

To investigate possible reverse causal directions among the main variables, we also examined the possible influence that initial depressive symptoms may have on perceived social competence and negative interactions. First, we examined whether negative interactions with parents mediated the depressive symptoms → perceived social competence association, as elevated levels of initial depressive symptoms could predict more negative interactions with parents, consistent with a stress-generation process, which in turn could then predict lower levels of perceived social competence. Both the T1 CDI → T3 SPPC T1 path (β = -.396, t = -8.051, p < .001) and the T1 CDI → T2 NRI parent path (β = .441, t = 9.156, < .001) were significant. However, after entering T1 CDI, the T2 NRI parent → T3 SPPC path was not significant (β = .049, t = .885, p = .377). Next, we examined whether perceived social competence mediated the depressive symptoms → NRI parent association, as initial levels of depressive symptoms could predict perceptions of poor social skills, which in turn could predict negative interactions. Both the T1 CDI → T3 NRI path (β = .449, t = 9.373, < .001) and the T1 CDI → T2 SPPC path (β = -.361, t = -7.228, < .001) were significant; however, after entering T1 CDI, the T2 SPPC → T3 NRI parent path was not significant (β = .031, t = .595, p = .552).

Finally, we tested other theoretically plausible moderator effects. Because perceived social competence is sometimes considered to be a vulnerability factor to depression that can function in a vulnerability-stress framework to predict depressive symptoms (e.g., Cole et al., 1996), we tested whether the interaction of T1 perceived social competence × T2 negative interactions with parents would predict T3 depressive symptoms. After controlling for initial levels of depressive symptoms and main effects, the T1 perceived social competence × T2 NRI parent interaction did not predict T3 CDI (β = -.303, t = -1.675, p = .095). We also tested a conceptually similar, expanded vulnerability-stress model to investigate whether the 3-way interaction of T1 negative cognitive style × T1 perceived social competence × T2 negative interactions with parents would predict T3 depressive symptoms. After controlling for initial levels of depressive symptoms and entering in all necessary main effects and 2-way interactions, this 3-way interaction did not significantly predict T3 depressive symptoms (β = -.802, t = -1.036, p = .301).

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to examine the temporally specific processes among perceived social competence, negative social interactions, and negative cognitive style in predicting depressive symptoms in adolescents within an integrative cognitive-interpersonal framework. Results showed that negative interactions with parents, but not peers, partially mediated the relationship between perceived social competence and depressive symptoms. In addition, and consistent with our hypothesis, findings revealed that adolescents with a more negative cognitive style were the most likely to exhibit increases in depressive symptoms when they experienced negative interactions with parents, and this cognitive vulnerability-parent stress interaction mediated the longitudinal association between baseline perceived social competence and later depressive symptoms. In sum, results from this study provided support for an integrated cognitive and interpersonal framework in understanding prospective prediction of depressive symptoms during adolescence.

In support of our first hypothesis, negative interactions with parents partially mediated the association between baseline perceived social competence and prospective changes in depressive symptoms. In other words, adolescents who rated themselves lower on perceptions of social competence tended to experience more negative interactions with parents, which in turn, predicted elevated levels of depressive symptoms. It is notable that these (partial) mediation effects were found even after accounting for initial levels of depressive symptoms, which accounted for a large portion of the variance. Thus, it appears that an adolescent's perceptions of his or her own social competence not only have a direct effect on depressive symptoms, but that these perceptions affect depressive symptoms via conflict with parents.

Similar to our findings, Stice and colleagues (2004) observed that lack of parental, but not peer, support predicted increases in depression among adolescent girls. Moreover, not only does the lack of parental support predict later depressive symptoms, but evidence also suggests that the presence of parental support decreases depressive symptoms in adolescents. Ge and colleagues (2009) showed that parental support buffered the association between adolescent stress exposure and depressive symptoms. Taken together, these findings suggest that, even during adolescence when peer relations play an increasingly significant role, parent relationships remain an important relationship (Steinberg, 2001; Steinberg & Morris, 2001) and have a significant impact on adolescent mood.

An interesting, but not entirely unexpected, finding was that lower levels of perceived social competence did not predict negative interactions with peers. We expected that low levels of perceived social competence would predict negative interactions with peers, albeit less so compared with negative interactions with parents, and that these negative peer interactions, in turn, would affect adolescent mood. The results from this study suggest that perceived social competence affects the frequency of negative interactions with parents, but not peers, at least with the sample age, methods, and design in this study (see also Stice et al., 2004). It may be that adolescents choose friends with whom they are more naturally interpersonally compatible (i.e., relationships that do not require high levels of social competence), whereas parent-child relationships are not chosen and goodness-of-fit issues may be more affected by perceived social competence and an adolescent's beliefs about the degree to which he or she may influence parents or the parent-youth relationship. Further, regarding long-term versus short-term relationships, it is possible that behaviors used to ameliorate conflict (e.g., apologizing, making amends) may be more effective in relatively newer relationships (i.e., friendships), and less effective in those in which long-standing interaction patterns have been established. In navigating longer-term relationships, perhaps higher levels of perceived social competence and finesse are especially important in influencing interactions in the context of established schemas and accumulated past negative experiences. Finally, that parent, but not peer, interactions mediated the perceived social competence and depressive symptoms association may partly be a function of age. It may be that as adolescents begin to navigate more complex social situations (e.g., dating) perceived social competence may affect the frequency of negative interactions with peers. Examining these associations with an older sample of adolescents would be an area for future research. In sum, these results suggest that disentangling the influences of negative interactions with parents from those with peers may uncover a more nuanced understanding of the impact of chronic interpersonal stress on adolescent depressive symptoms.

Overall, these results highlight the importance of the parent-adolescent relationship. However, it should be noted that the relative importance of parent versus peer influence may vary depending upon the specific outcome. That is, it may be that negative interactions with parents are more important in predicting depressive symptoms in adolescence, whereas peer interactions may be more important in predicting other adolescent outcomes, such as externalizing problems. For example, research on delinquent behaviors (e.g., Huey, Henggeler, Brondino, & Pickrel, 2000) suggests that peer influence plays a more influential role on adolescent behavior than parental monitoring. Thus, parent versus peer influence on adolescent behaviors and emotions likely depends on which developmental outcomes are examined.

Regarding our second hypothesis, analyses showed that pessimistic youth who experienced negative interactions with parents were the most likely to exhibit prospective increases in depressive symptoms over time, and this cognitive vulnerability-parent stress interaction predicted later depressive symptoms (more than negative interactions with parents alone). It is notable that the addition of negative cognitive style as a moderator interacted with increases in negative interactions with parents to predict prospective elevations in depressive symptoms above and beyond perceived social competence, which prior research has indicated is a relatively reliable and robust predictor of depression (Cole et al. 1996). As some have suggested that perceived (low) social competence may be a cognitive risk to depression (Cole et al., 1996), our finding that a negative cognitive style interacted with increased levels of negative parental interactions to predict prospective elevations in depressive symptoms above and beyond initial perceived social competence is noteworthy. Although we assessed perceptions of social competence, and not social competence per se, these results are consistent with Rudolph and Clark's (2001) findings that support both skill-deficit and cognitive distortion models of depression in children.

Moreover, additional exploratory analyses revealed that perceived social competence as a potential cognitive vulnerability did not interact with negative interactions with parents to predict later depressive symptoms. This suggests that generic cognitive vulnerability does not necessarily moderate the association between nonspecific interpersonal stress and later depressive symptoms. Rather, it appears important to consider carefully the particular type of cognitive risk, specifically a negative cognitive style in this study, as well as the particular type of interpersonal stress, specifically negative interactions with parents, for how cognitive and interpersonal risk factors and processes can be integrated together to understand and predict depressive symptoms over time.

Although this study did not examine particular processes that might underlie the negative cognitive style × negative interactions with parents interaction predicting later depressive symptoms, there may be something particularly depressogenic about the interactive combination of these specific cognitive and interpersonal factors that contributes to increases in depressive symptoms. Prior research suggests that negative parenting styles (e.g., authoritarian) and behaviors (critical and emotionally abuse statements) can affect the development and emergence of children's cognitive vulnerabilities, especially a negative cognitive style (e.g., Alloy et al., 2006; Hankin et al., 2009). The interaction of a negative cognitive style with negative interactions with parents may be a particularly potent combination because pessimistic youth may interpret negative interactions with their parents in an even more depressogenic manner (i.e., make stable, global attributions about the cause of conflict with parents, make negative inferences about their self, and catastrophize the potential meaning of parental conflict), even when compared with conflict with peers, because such pessimistic youth have developed a negative cognitive style, at least in part, because of repeated negative interactions with their parents. It may be that when pessimistic adolescents experience negative interactions with parents, more negative memories of prior conflicts with parents and experiences with negative parenting (e.g., hostile, critical parental behaviors) are recalled and are more deeply associated with youths’ sense of self, world, and future. As a result, the specific interaction between a negative cognitive style and conflict with parents is particularly likely to engender increases in depressive symptoms. Future research can examine such hypotheses to further understand possible mechanisms underlying this cognitive vulnerability-parent stress interaction predicting later depressive symptoms.

Past research investigating the interaction of cognitive vulnerability with stress has typically examined either general stressors (e.g., Abela, 2001; Cole et al., 2008; Hankin et al., 2001; Hankin, 2008b; Morris, Ciesla, & Garber, 2008) or stressors that can be categorized into general achievement or interpersonal domains (Abela, 2002; Abela & Seligman, 2000; Garber et al., 1995; Hankin et al., 2004). To our knowledge, only two other studies (Hankin, Mermelstein, and Roesch, 2007; Rudolph and Hammen, 1999) have examined parent/family and peer interpersonal stressors separately. Because adolescence is a period of transition when relationships with parents and peers begin to change, future research on different types of stress, degree of in/dependence (of stressors), and conflict in specific relationships will likely provide a better understanding of the effect of stress, as well as the moderating influence of cognitive vulnerability, on adolescent depressive symptoms.

Strengths and Limitations

The current study advances the literature in several important ways. We examined the specific interpersonal stress of negative interactions with parents and peers separately, as mediators of the association between perceived social competence and later depressive symptoms. This study contributes to our understanding of the direct and indirect effects of perceived social competence, differential effects of conflictual relationships with parents versus peers, and the interactive impact of negative cognitive style with specific negative social interactions on adolescent depressive symptoms, within an integrative cognitive-interpersonal framework. Second, analyses of separate and subsequent time points in a multi-wave longitudinal design provide a strong test of the hypothesized mediational pathways (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Third, this study utilized a diverse sample from various middle and high schools, representing a range of ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds.

However, there were some limitations to this study. The data analyzed in this study were based on adolescent self-reports only. Self-report data on perceived social competence may be somewhat biased depending on depressive symptom severity. For those adolescents who reported high levels of depressive symptoms, self-perceptions of social competence may be negatively biased, although adolescents who reported more mild levels of depressive symptoms may be providing more “accurate” assessments of social competence (Whitton, Larson & Hauser, 2008). Obtaining reports from multiple informants (i.e., parents, peers, and teachers) in combination with data from information processing and observation tasks would provide a more rigorous and comprehensive assessment of social competence, negative cognitive style, and depressive symptoms.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Results from the current study suggest that examination of specific characteristics of negative interactions is worthwhile. In addition to the implications from the current findings that conflict with parents affects mood more strongly than conflict with peers during early to middle adolescence, consideration of specific factors such as whether a particular negative interaction is a consequence of a chronic or specific situation, to whom or what the adolescent primarily attributes the cause of the negative interaction, whether a lower or higher possibility of resolution is perceived, and whether the negative interaction is initiated by the parent or by the adolescent, may also be useful in understanding the impact of negative interactions on adolescent mood. Thus, further research on the contributory role an adolescent plays in the generation of stressful events, especially negative social interactions (and the adolescent's understanding of his or her contribution to these events), along with the role of negative cognitions, may provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding the development and maintenance of depression in adolescents.

Results from this study suggest potential multiple points of intervention in both cognitive and interpersonal domains. For example, it is likely to be more beneficial for an adolescent to decrease behaviors that may contribute to negative interactions with others as well as decrease negative cognitions regarding stressful events, than taking a single line approach, in decreasing negative mood. Specifically, findings from the current study suggest that perceived social competence affects depressive symptoms both directly and indirectly through negative interactions with parents. Because negative interactions with parents uniquely predicted depressive symptoms, family therapy addressing communication and conflict resolution between family members is likely a more effective intervention for depressed adolescents than individual therapy alone. In Diamond & Josephson's (2005) review of the literature, they found support for the use of family therapy, either by itself or in conjunction with individual therapy, as an effective intervention for depressed adolescents. They suggest that the inclusion of parents in therapy sessions to address family dynamics and to develop a more adaptive family environment may help initiate and maintain therapy gains. In addition, results from this study provide additional support for the utilization of cognitive-behavioral therapy in individual therapy for adolescents focused on modifying negative cognitions (Reinecke & Ginsburg, 2008). Although high levels of stress alone, especially with parents, predict prospective increases in depressive symptoms, adolescents who reported both high levels of stress and high levels of negative cognitive style were at the highest risk for depression. Modifying negative cognitive style, decreasing the likelihood of being involved in stressful or conflictual social interactions, and increasing adaptive coping skills will likely decrease vulnerability to depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by NIMH grants R03-MH 066845 and 5R01 MH077195 to the second author.

Footnotes

The full correlation matrix of all variables at all time points is available by contacting the first author. The correlations presented here represent the main associations of interest for the central hypotheses of the study.

Results from analyses examining overall NRI scores were not significant. Specifically, T1 perceived social competence did not predict T2 total negative interactions (β = -.085, t = -1.586, p = .114). The nonsignificance of the overall scores was most likely due to the nonsignificance of the peer interactions “canceling out” the effects for parent interactions.

Contributor Information

Adabel Lee, University of Michigan, Department of Psychiatry.

Benjamin L. Hankin, University of Denver, Department of Psychology

Robin J. Mermelstein, University of Illinois at Chicago, Department of Psychology

References

- Abela JRZ. The hopelessness theory of depression: A test of the diathesis-stress and causal mediation components in third and seventh grade children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:241–254. doi: 10.1023/a:1010333815728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ. Depressive mood reactions to failure in the achievement domain: A test of the integration of the hopelessness and self-esteem theories of depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:531–552. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. Guilford Press; NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents: A developmental psychopathology approach. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of Child and Adolescent Depression. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Seligman MEP. The hopelessness theory of depression: A test of the diathesis-stress component in the interpersonal and achievement domains. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:361–378. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Alloy LB, Hankin BL, Haeffel GJ, MacCoon D, Gibb BE. Cognitive vulnerability-stress models of depression in a self-regulatory and psychobiological context. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of Depression. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. pp. 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Adler TF, Furman W. A model for children's relationships and relationship dysfunctions. In: Duck S, Hay DF, Hobfoll SE, Ickes W, Montgomery BM, editors. Handbook of personal relationships: Theory, research and interventions. John Wiley & Sons; Oxford, England: 1988. pp. 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Adrian C, Hammen C. Stress exposure and stress generation in children of depressed mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:354–359. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Insabella G, Porter MR, Smith FD, Land D, Phillips N. A social-interactional model of the development of depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:55–65. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Smith JM, Gibb BE, Neeren AM. Role of parenting and maltreatment histories in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders: Mediation by cognitive vulnerability to depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2006;9:23–64. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S, Messick S. Social competency in young children. Developmental Psychology. 1974;10:282–293. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos (Version 7.0) [Computer Program] SPSS; Chicago: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Avison WR, Turner RJ. Stressful life events and depressive symptoms: Disaggregating the effects of acute stressors and chronic strains. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1988;29:253–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman K, McCauley E. Children's descriptions of their peer interactions: Useful information for clinical child assessment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1987;16:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Billings AG, Moos RH. Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with unipolar depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:877–891. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Kaufman J, Dahl RE, Perel J, Nelson B. Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years. Part I. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Williamson DE, Dahl RE, Axelson DA, Kaufman J, Dorn LD, et al. Clinical presentation and course of depression in youth: Does onset in childhood differ from onset in adolescence? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:63–70. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Liu M, Rubin KH, Cen G, Gao X, Li D. Sociability and prosocial orientation as predictors of youth adjustment: A seven-year longitudinal study in a Chinese sample. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2002;26:128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Childs HF, Schneider HG, Dula CS. Adolescent adjustment: Maternal depression and social competence. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2001;9:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi J, Scott G, Deane FP, Heaven PCL. Relations between social and emotional competence and mental health: A construct validation study. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:1947–1963. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ, US: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Ciesla JA, Dallaire DH, Jacquez FM, Pineda AQ, LaGrange B, et al. Emergence of attributional style and its relation to depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:16–31. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Powers B, Truglio R. Modeling causal relations between academic and social competence and depression: A multitrait-multimethod longitudinal study of children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:258–270. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Egger HL, Angold A. The developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders: Phenomenology, prevalence, and comorbidity. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;14:631–648. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1263–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry. 1976;39:28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craighead WE, Curry JF, Ilardi SS. Relationship of Children's Depression Inventory factors to major depression among adolescents. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Hammen C, Burge D, Paley B, Daley SE. Poor interpersonal problem solving as a mechanism of stress generation in depression among adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:592–600. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond G, Josephson A. Family-Based Treatment Research: A 10-Year Update. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:872–887. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000169010.96783.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenzel LM. Prospective study of changes in global self-worth and strain during the transition to middle school. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2000;20:93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Braafladt N, Weiss B. Affect regulation in depressed and nondepressed children and young adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Natsuaki MN, Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D. The longitudinal effects of stressful life events on adolescent depression are buffered by parent–child closeness. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:621–635. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisset NI, Norvell NK. Perceived social support, social skills, and quality of relationships in bulimic women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:293–299. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ, et al. Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression: Development and validation of the cognitive style questionnaire. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:824–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Life events and depression: The plot thickens. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;20:179–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00940835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA. Interpersonal dysfunction in depressed women: impairments independent of depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;72:145–156. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00455-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Shih JH, Brennan PA. Intergenerational transmission of depression: Test of an interpersonal stress model in a community sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:511–522. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Stability of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: A short-term prospective multiwave study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008a;117:324–333. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Cognitive vulnerability-stress model of depression during adolescence: Investigating depressive symptom specificity in a multi-wave prospective study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008b;36:999–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression in adolescence: Reliability, validity and gender differences. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:491–504. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Miller N, Haeffel GJ. Cognitive vulnerability-stress theories of depression: Examining affective specificity in the prediction of depression versus anxiety in three prospective studies. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2004;28:309–345. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Siler M. A prospective test of the hopelessness theory of depression in adolescence. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:607–632. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Mermelstein RJ, Roesch L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development. 2007;78:279–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Oppenheimer C, Jenness J, Barrocas A, Shapero BG, Goldband J. Developmental origins of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: Review of processes contributing to stability and change across time. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:1327–1338. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Children. University of Denver; 1985. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. Guilford Press; New York, NY, US: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S, Whitesell NR. Multiple pathways to self-reported depression and psychological adjustment among adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:761–777. [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Jr., Henggeler SW, Brondino MJ, Pickrel SG. Mechanisms of change in multisystemic therapy: Reducing delinquent behavior through therapist adherence and improved family and peer functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:451–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter FT, Youniss J. Changes in function of three relations during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:806–811. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Coyne JC. The interactional nature of depression: Advances in interpersonal approaches. American Psychological Association; Washington, D. C.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Dougherty LR, Olino TM. Toward guidelines for evidence-based assessment of depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:412–432. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children's Depression Inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakdawalla Z, Hankin BL, Mermelstein RJ. Cognitive theories of depression in children and adolescents: A conceptual and quantitative review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ. Associations among emotionality, self-regulation, adjustment problems, and positive adjustment in middle childhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24:595–618. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder: I. Continuity into young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:56–63. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199901000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz. MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, Feehan M, Williams S, Partridge F, et al. DSM-III disorders in a large sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:611–619. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, Stanton WR. Sources of distress among New Zealand adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 1992;33:999–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonagle KA, Kessler RC. Chronic stress, acute stress, and depressive symptoms. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1990;18:681–706. doi: 10.1007/BF00931237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Slavich GM, Torres LD, Gotlib IH. Severe life events predict specific patterns of change in cognitive biases in major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:863–871. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Ciesla JA, Garber J. A prospective study of the cognitive-stress model of depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:719–734. doi: 10.1037/a0013741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, Fijen P. The Self-Perception Profile for Children: Further evidence for its factor structure, reliability, and validity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:1791–1802. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kazdin AE. Parent-directed physical aggression by clinic-referred youths. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:193–205. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3102_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters RD. Mental health promotion in children and adolescents: An emerging role for psychology. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 1988;20:389–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke MA, Ginsburg GS. Cognitive behavioral treatment of depression during childhood and adolescence. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. Guilford; New York, NY, US: 2008. pp. 179–206. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Clark AG. Conceptions of relationships in children with depressive and aggressive symptoms: Social-cognitive distortion or reality? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:41–56. doi: 10.1023/a:1005299429060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M, Abaied JL. A developmental perspective on interpersonal theories of youth depression. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. Guilford Press; New York, NY, US: 2008. pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C. Age and gender as determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: A transactional perspective. Child Development. 1999;70:660–677. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D, Lindberg N, Herzberg D, Daley SE. Toward an interpersonal life-stress model of depression: The developmental context of stress generation. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:215–234. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400002066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautment P, Moreau D, Kleinman M, Flory M. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:339–348. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smucker MR, Craighead WE, Craighead LW, Green BJ. Normative and reliability data for the Children's Depression Inventory. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1986;14:25–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00917219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology 1982. American Sociological Association; Washington DC: 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sourander A, Helstelä L, Haavisto A, Bergroth L. Suicidal thoughts and attempts among adolescents: A longitudinal 8-year follow-up study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;63:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Dahl D, Keating D, Kupfer DJ, Masten AS, Pine DS. The study of developmental psychopathology in adolescence: Integrating affective neuroscience with the study of context. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental Psychopathology, Vol. 2: Developmental neuroscience (2nd ed.) John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, US: 2006. pp. 710–741. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Ragan J, Randall P. Prospective relations between social support and depression: Differential direction of effects for parent and peer support? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore EA, Mikulich SK, Thompson LL, Riggs PD, Aarons GA, Crowley TJ, et al. Influences on adolescent substance dependence: Conduct disorder, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and gender. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;47:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Larson JJ, Hauser ST. Depressive Symptoms and Bias in Perceived Social Competence Among Young Adults. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2008;64:791–805. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DE, Forbes EE, Dahl RE, Ryan ND. A genetic epidemiologic perspective on comorbidity of depression and anxiety. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;14:707–726. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters NC, Myers K, Proud L. Ten-year review of rating scales. III: Scales assessing suicidality, cognitive style, and self-esteem. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1150–1181. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Kohn R, Keitner G, Della Grotta SA. The relationship between quality of interpersonal relationships and major depressive disorder: Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000;59:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]