Functionalized pyridine and 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives have long been known as important biologically active compounds.1,2 While the 1,4-dihydropyridines have been extensively used as calcium channel modulators,1b their oxidized counterparts target a wide variety of biological receptors.2 Due to the prevalence of pyridines in pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and natural products, their synthesis remains an area of intense current interest to the chemical community.3 Many of the methods for preparing substituted pyridines rely on the Hantzsch reaction4 between amines and carbonyl compounds, necessarily restricting functionality at the 3 and 5 positions to carboxyl groups. Other common methods include multicomponent condensation reactions,3d cycloadditions3b,g,i,k and the electrocyclization of azatrienes.3a,c,f We herein report a conceptually distinct approach to the synthesis of highly substituted pyridines from isoxazoles. This approach is based upon a rhodium carbenoid-induced ring expansion of isoxazoles, followed by rearrangement to a dihydropyridine and oxidation to the corresponding pyridine.

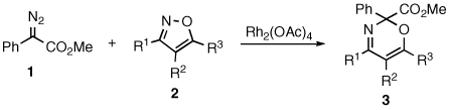

We recently reported that isoxazoles are capable of undergoing efficient ring expansion reactions with the donor/acceptor-substituted rhodium carbenoid derived from methyl phenyldiazoacetate 1 (eq 1).5 The isoxazole ring expansion likely proceeds through an ylide intermediate.6

|

(1) |

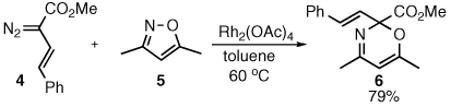

We reasoned that if the same reaction were conducted with a vinyldiazomethane, the resulting product might then be capable of undergoing a rearrangement to form a 3,4-dihydropyridine. To test this hypothesis, the ring expansion product 6 of 3,5-dimethylisoxazole (5) with (E)styrylvinyldiazoaceate 4 was prepared in 79% yield via the Rh2(OAc)4 catalyzed reaction (eq 2). When 6 was heated in toluene it underwent rearrangement, but the isolated product was 1,4-dihydropyridine 7, not the expected 3,4-dihydropyridine 8 (eq 3).

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

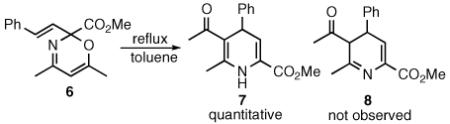

This isomeric product was likely formed by a facile tautomerization of the putative rearrangement product 8. The transformation likely proceeds through one of two distinct mechanistic pathways outlined below (eq 4). Upon heating, the N–O insertion product 9 could undergo a Claisen rearrangement to directly give 3,4-dihydropyridine 10. Alternatively, 9 could undergo an electrocyclic ring opening to azatriene 11, followed by a 6 electrocyclization to give 10. Tautomerization of 10 then leads to the isolated 1,4-dihydropyridine product 12.

|

(4) |

Having demonstrated that the N–O insertion product of an isoxazole with a vinyl carbenoid could successfully rearrange to a 1,4-dihydropyridine, the next step was to develop a onepot synthesis of the corresponding pyridine. The reaction conditions were carefully chosen according to the following criteria: 1) reversible coordination of the isoxazole nitrogen lone pair to the Rh(II) catalyst necessitates conducting the diazo addition at elevated temperatures to ensure decomposition to the carbenoid, 2) vinyldiazo compounds are prone to undergo a 6π electrocyclization reaction to form pyrazoles at elevated temperatures,7 and 3) the solvent must have a high boiling point to efficiently promote the subsequent rearrangement and must not react with the carbenoid. As such, the optimal conditions for most of the examples shown require a 30 min syringe pump addition of the diazo compound to the solution of catalyst and isoxazole at 60 °C in toluene. The solution is then heated at reflux for 4 h before being cooled to ambient temperature for the DDQ oxidation.

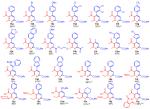

The results of this study are shown in Table 1. The reaction is very efficient for most of the reactions with substituted arylvinyldiazoacetates and 5, with the yields being slightly higher for electron deficient aromatics (15a-15j). The standard reactions were conducted with 2 mol % of catalyst, but in many cases the reactions could be conducted with just 0.5 mol % of catalyst without any loss in yield. A good yield can also be obtained using an arylvinyldiazo ketone (15k) and a diester substituted vinyl diazo compound (15w). The electron rich heteroaromatic vinyldiazoacetates (15m-15q) gave lower yields with the exception of the Boc protected indolylvinyldiazoacetate (15o). A particularly attractive feature of this method is the ready access of 3,5-disubstituted isoxazoles using the copper catalyzed process developed by Fokin and coworkers.8 Thus, the pyridines can be widely varied by use of a two step, three component coupling protocol (eq 5), as illustrated in products 15r-15y. A protected 2-aminopyridine 15z was also synthesized from a protected 3-aminoisoxazole. The structure of pyridine 15b has been unambiguously determined by X-ray crystallography.9

Table 1.

One-Pot Synthesis of Highly Functionalized Pyridines

|

Uniform conditions unless otherwise noted: 2 eq diazo compound, 2 mol% Rh2(OAc)4, 30 min diazo compound addition at 60 °C, then reflux for 4 h, then rt DDQ addition

0.5 mol% Rh2(OAc)4 used

4 eq of diazo compound used

diazo compound added at reflux

3 eq of diazo compound used

refluxed overnight after diazo compound addition

|

(5) |

In summary, an efficient one-pot procedure for the synthesis of highly functionalized pyridines and 1,4-dihydropyridines has been developed. The reaction proceeds via an initial carbenoid induced ring expansion of isoxazoles followed by a rearrangement/tautomerization/oxidation sequence. A wide variety of 3,5-disubstituted isoxazoles and vinyldiazomethanes are compatible with this sequence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The National Institutes of Health is gratefully acknowledged. J.R.M. thanks the National Institutes of Health for a Ruth L. Kirchstein predoctoral fellowship (DA019287). We thank Mateusz Pitak and Milan Gembicky for the X-ray crystallographic analysis.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Full experimental data for the compounds described in this paper; X-ray crystallographic file in CIF format.

References

- 1.(a) Joule JA, Mills K. Heterocyclic Chemistry. 4th ed. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2000. [Google Scholar]; (b) Triggle DJ. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2003;23:293–303. doi: 10.1023/A:1023632419813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For a thorough review of the history, applications and synthesis of pyridine derivatives: Henry GD. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:6043–6061.

- 3.For recent syntheses of highly substituted pyridines, see: Colby DA, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3645–3651. doi: 10.1021/ja7104784. Barluenga J, Fernández-Rodríguez MA, García-García P, Aguilar E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2764–2765. doi: 10.1021/ja7112917. Parthasarathy K, Jeganmohan M, Cheng C-H. Org. Lett. 2008;10:325–328. doi: 10.1021/ol7028367. Dash J, Lechel T, Reissig H-U. Org. Lett. 2007;9:5541–5544. doi: 10.1021/ol702468s. Movassaghi M, Hill MD, Ahmad OK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10096–10097. doi: 10.1021/ja073912a. Trost BM, Gutierrez AC. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1473–1476. doi: 10.1021/ol070163t. Fletcher MD, Hurst TE, Miles TJ, Moody CJ. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:5454–5463. Movassaghi M, Hill MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4592–4593. doi: 10.1021/ja060626a. Tanaka K, Suzuki N, Nishida G. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006:3917–3922. Yamamoto Y, Kinpara K, Ogawa R, Nishiyama H, Itoh K. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:5618–5631. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600176. McCormick MM, Duong HA, Zuo G, Louie J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:5030–5031. doi: 10.1021/ja0508931.

- 4.Sausins A, Duburs G. Heterocycles. 1988;27:269–289. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stout DM, Meyers AI. Chem. Rev. 1982;82:223–243. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manning JR, Davies HML. Tetrahedron. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.03.010. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For other recent examples of rhodium carbenoid reactions involving ylides, see: Liao M, Peng L, Wang J. Org. Lett. 2008;10:693–696. doi: 10.1021/ol703058p. Padwa A. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005;690:5533–5540. Yan M, Jacobsen N, Hu W, Gronenberg LS, Doyle MP, Colyer JT, Bykowski D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2004;43:6713–6716. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461722.

- 7.Davies HML, Clark DM, Smith TK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:5659–5662. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen TV, Wu P, Fokin VV. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:7761–7764. doi: 10.1021/jo050163b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The X-ray crystallographic data have been submitted to the Cambridge Structure Database [Pitak M, Gembicky M, Coppens P. Private Communication. 2008:CCDC 675737.].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.