Introduction

Wnt ligands comprise a family of lipid-modified signaling proteins critical for normal embryonic development (Haegel et al., 1995; Logan and Nusse, 2004; Klaus and Birchmeier, 2008). Wnts, their receptors, and components of the intracellular signaling pathway are ancient and conserved throughout the animal kingdom (Cadigan and Nusse, 1997; Steele, 2002). Wnt ligands bind to their receptors, Frizzled and lipoprotein receptor-related proteins (LRP), to initiate an intracellular signaling cascade to the nucleus that is transduced by β-catenin (Nelson and Nusse, 2004). After β-catenin binds to the TCF/Lef family of cofactors, downstream target genes are transcribed to direct the various functions of Wnt signaling in development (Nelson and Nusse, 2004). In addition to their normal role in development, Wnt signaling pathway can become misregulated and lead to cancer and degenerative diseases (Logan and Nusse, 2004; Clevers, 2006).

The roles of Wnt proteins in craniofacial development have been examined in specific regions and cell types of interest using different versions of transgenic lines that express nuclear beta-galactosidase under the control of several TCF/Lef-binding sites (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999; Maretto et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2006; Ohyama et al., 2006; Brugmann et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2007; Zaghetto et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2008) or the Axin2 promoter (Lustig et al., 2002). Traditionally, Wnt signaling reporter expression analysis is presented using single high magnification images of a specific organ at developmental time points of interest. Here, we show the Wnt signaling reporter expression pattern in representative serial sections of the entire mouse head between embryonic days (E) 8.5–16.5. We have used a recently developed Wnt signaling reporter line that has multimerized TCF/Lef-binding sites under the control of the hsp68 minimal promoter to characterize Wnt signaling activity (Liu et al., 2003). Our results provide a comprehensive reference atlas of Wnt signaling activity during craniofacial development in the mouse embryo from E8.0–16.5.

Results

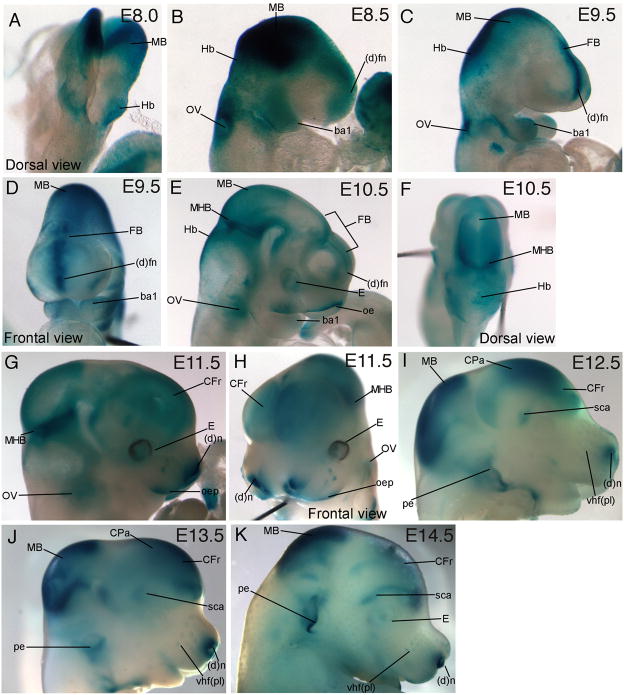

To obtain an overview of the spatial and temporal expression of Wnt signaling reporter activity, we visualized β-galactosidase (β-gal) expression from E8.0–E14.5 in the heads of TCF/Lef-LacZ mouse embryos at the whole mount level. At E8.0, Wnt signaling reporter activity was prominently visible in the midbrain (MB) and hindbrain regions (Hb, Fig. 1A). By E8.5, β-gal expression was also visible in the otic vesicle (OV), the distal frontonasal mass ((d)fn) and the first branchial arch (ba1) (Fig. 1B). By E9.5, β-gal expression was strong in the midbrain (MB), hindbrain, in the midline of the distal frontonasal mass, otic vesicle (Fig. 1C). Expression continued in the forebrain (FB) and branchial arch 1 (Fig. 1C, D). At E10.5, β-gal expression was observed in the frontonasal mass, oral ectoderm (oe), distal branchial arch 1, forebrain, midbrain, mid-hindbrain boundary (MHB), hindbrain, otic vesicle, and the eye (E, Fig. 1E, F). By E11.5, Wnt signaling reporter activity became more restricted and was seen strongly in the mid-hindbrain boundary, distal oral epithelium (oep), and distal nostril ((d)n, Fig. 1G, H). Diffuse β-gal expression was also visible in the frontal cortex (CFr), in the area adjacent to the mid-hindbrain boundary, and in the otic vesicle (Fig. 1G). At E12.5, β-gal expression was expanded in the midbrain and parietal cortex (CPa, Fig. 1E) and diffuse staining was visible in the superciliary (sca) region above the eye, in the snout, and in the pinna of the ear (pe, Fig. 1I). β-gal expression at E13.5 was similar to the expression pattern at E12.5 and was enhanced in the vibrissae hair follicle placodes (vhf (pl), Fig. 1J). At E14.5, reporter activity was strong in similar regions as those found in the E12.5 and E13.5 embryo with prominence in the vibrissae hair follicle placodes and pinna of the ear (Fig. 1K). The expression pattern at the whole mount level shows that Wnt signaling reporter activity was persistent in several regions such as the midbrain-hindbrain boundary, midbrain, forebrain, distal snout, and the developing ear.

Figure 1. Wnt signaling reporter, TCF/Lef-LacZ expression in whole mount embryros.

β-gal expression (blue) in embryonic heads during development from E8.5–14.5. Expression was visible in the following structures: forebrain (FB), midbrain (MB), hindbrain (Hb), distal frontonasal mass ((d)fn), otic vesicle (OV), branchial arch (ba), Frontal cortex (CFr), parietal cortex (CPa), mid-hindbrain boundary (MHB), oral epithelium (oe), superciliary arch (sca), distal tips of nostril ((d)n), vibrissae hair follicle placode (vhf (pl)), pinna of the ear (pe), and Eye (E)

To further improve the spatial resolution of Wnt signaling reporter activity during craniofacial development, we examined β-gal expression in serial cryosections of the embryo between E8.25 and E16.5. Transgene negative littermate controls did not have β-gal expression in any of the craniofacial tissues (data not shown).

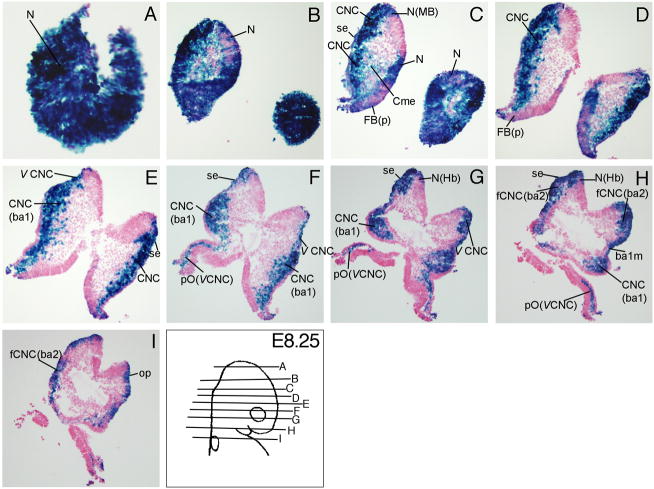

At E8.25, Wnt signaling reporter activity was detectable in the neuroepithelium (N) of prospective forebrain (FB), midbrain (MB), and hindbrain (Hb) regions (Fig. 2A-C, G, H), the cephalic mesenchyme (Cme, Fig. 2C), surface ectoderm (se) above the neural folds, branchial arch 2 (ba2, Fig 2C, H, I), the otic placode (op, Fig. 2I), and in the branchial arch 1 membrane (ba1m) which will become the future tympanic membrane (Fig. 2H). TCF/Lef-LacZ expression was extensive in the migrating cranial neural crest cells. Wnt signaling reporter activity was detected in the cranial neural crest cells (CNC) in the neural folds (Fig. 2C-E), in the branchial arch 1(CNC(ba1), Fig. 2E-H), in the facial neural crest of branchial arch 2 (fCNC (ba2), Fig. 2H, I), in the trigeminal (V) cranial crest (V CNC, Fig. 2E-G), and in the perioptic neural crest derived from the trigeminal cranial neural crest (pO (CNC), Fig. 2F-H).

Figure 2. TCF/Lef-LacZ expression in transverse sections of an E8.5 mouse embryo.

β-gal expression (blue) was prominent in the pre- and post-migratory cranial neural crest cells and the neural folds. For additional labeled structures with β-gal expression, refer to the glossary.

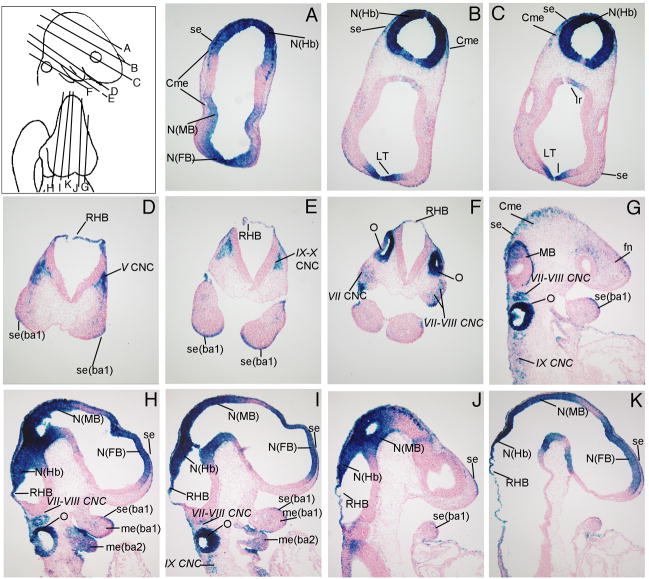

At E9.5, β-gal expression continues to be visible in the differentiating neuroepithelium (N) of the forebrain (FB), midbrain (MB), and hindbrain (Hb, Fig. 3A-C, H-K). Wnt signaling reporter activity was detected in cranial neural crest cells (CNC) migrating into the various ganglia in the head such as the trigeminal placode (V CNC, Figs. 3D), facial nerve (VII CNC, Fig. 3F, G-I), acoustic spiral ganglion (VIII CNC, Fig 3F-I), and glassopharyngeal (IX CNC) and vagal complexes (X CNC) (Fig. 3E, G, I). Wnt signaling reporter activity was detected in the infundibular recess (Ir, Fig. 3C), the lamina terminalis (LT, Fig. 3B, C), the cephalic mesenchyme (Cme) overlying the midbrain and hindbrain (Fig. 3A-C), the roof of the hindbrain (RHB, Fig. 3D-F, H-K), the distal surface ectoderm (se) and mesenchyme (me) of the first and second branchial arches (ba, Fig. 3D, E, G-J), and in the developing otocyst (O, Figs. 3F, G, H, I).

Figure 3. TCF/Lef-LacZ expression in transverse and sagittal sections of an E9.5 mouse embryo.

β-gal expression was apparent in the differentiating neuroepithelium and the otocyst. For additional labeled structures with β-gal expression, refer to the glossary.

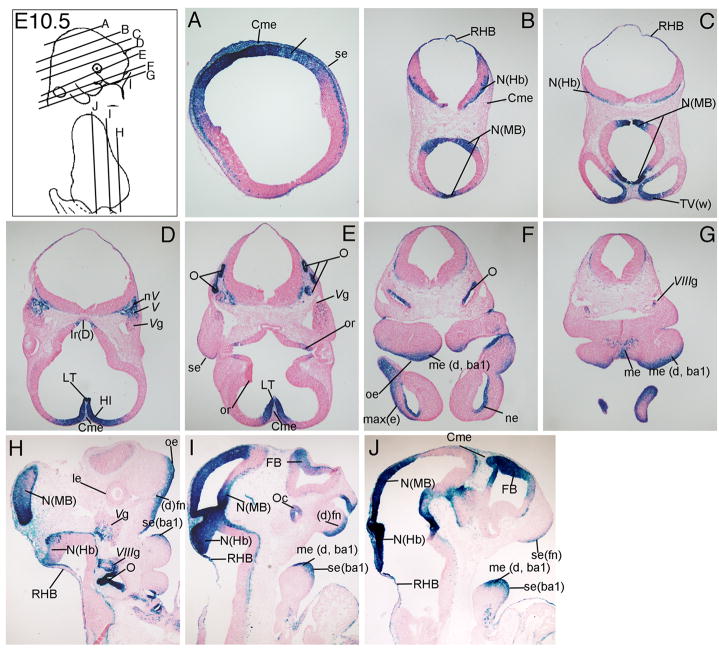

At E10.5, Wnt signaling reporter expression became restricted to portions of the neuroepithelium (N) of the forebrain (Fb), midbrain (MB), and hindbrain (Hb, Fig. 4A-C, H-J) and the developing otocyst (O, Fig. 4F, H). Wnt signaling reporter activity was detectable in the ventricular zone of the hippocampus (HI, Fig. 4D), trigeminal nerves (nV) and ganglion (Vg, Fig. 4D, H), the acoustic ganglion (VIIIg, Fig. 4G, H), nasal epithelium (ne, Fig. 4F), optic recess (or, Fig. 4E), optic cup (oc, Fig. 4I), and distal frontonasal mass ((d)fn, Fig. 4I). β-gal expression continued to be visible in the roof of the hindbrain (RHB, Fig. 4B, C), lamina terminalis (LT, Fig. 4D, E), the cephalic mesenchyme (Cme) overlying the developing brain (Fig. 4D, E, J), oral ectoderm (oe, Fig. 4F, H, ectoderm (max(e), Fig. 4F) and the distal mesencyme of the developing maxilla from the first branchial arch (me (d, ba1), Fig. 4F, G, I, J).

Figure 4. TCF/Lef-LacZ expression in transverse and sagittal sections of an E10.5 mouse embryo.

Wnt signaling activity was most notable in the neuroepithelium (N) of the mid-hindbrain region (MHB), distal (d) oral ectoderm (oe) and mesenchyme (me). For additional labeled structures with β-gal expression, refer to the glossary.

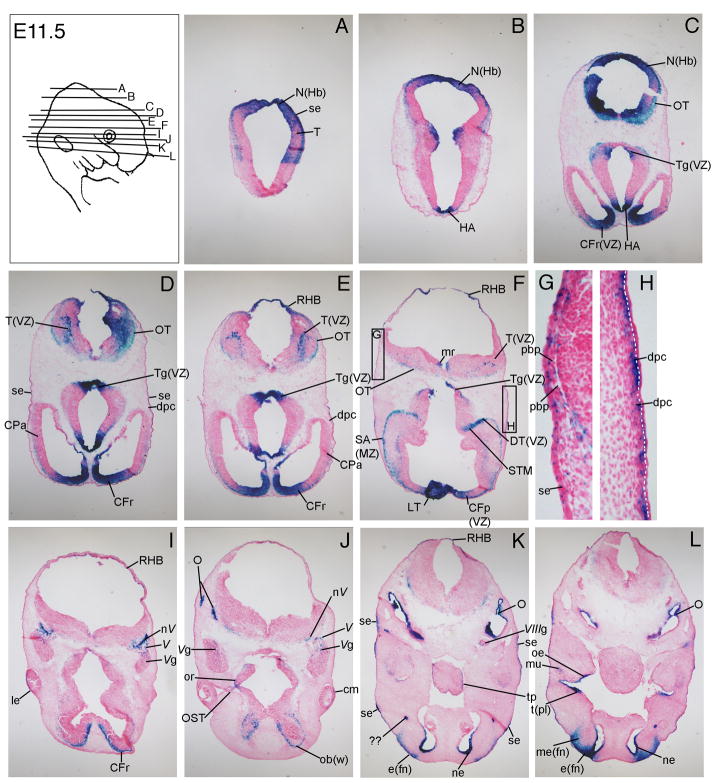

At E11.5, Wnt signaling reporter activity was visible in defined regions of the differentiating brain. In the forebrain region, the anterior frontal cortex (CFr and CFp, Fig. 5C-I), the septal area (SA), the ventricular zone of the dorsal thalamus (DT (VZ)) and the stria medullaris (STM) of the cortex (Fig. 5F) expressed β-gal. The tegmentum (Tg, Fig. 5C-F) and the habenula (HA) in the midbrain (Fig. 5B, C) and the dorsal neuroepithelium of the hindbrain (N (Hb), Fig. 5A-C), tectum (T, Fig. 5A, D-F), optic tract (OT, Fig. 5C-F), and medulla raphae (mr, Fig. 5F) of the hindbrain had Wnt signaling reporter expression. Consistent with published studies of other Wnt signaling reporters at E11.5, we also observed β-gal expression in the emerging ectodermal-derived structures such as the lens epithelium (le) of the eye (Fig. 5I), ciliary margin (cm) of the eye (Fig. 5J), the entire oral ectoderm (oe) and tooth placode (t(pl), Fig. 5L) and the tongue papillae (tp, Fig. 5K). Higher magnification views of TCF/Lef-LacZ expression and other reporter lines in developing eyes, tongue papillae, and teeth placodes at E11.5 were shown in recently published reports (Liu et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2008). Wnt signaling reporter activity was also visible in the wall of the olfactory bulb (ob (w), Fig. 5J), muscle cells (mu) in the jaw (Fig. 5L), optic stalk (OST, Fig. 5J), subectodermal dermal progenitor cells (dpc) in the superciliary arch above the eye (Fig. 5D, E, H) and the parietal bone progenitors (pbp, Fig. 5E, G). The progenitor cells in the superciliary arch have been recently fate-mapped in the mouse embryo and can contribute to the skull bones and the craniofacial dermis in the skin (Fig. 5F, H) (Yoshida et al., 2008). β-gal expression continues in the optic recess (or) (Fig 5J), trigeminal ganglion and nerve (V, Vg, Fig 5I, J), acoustic ganglion (VIIIg, Fig. 5K), nasal epithelium (ne, Fig. 5K, L), mesenchyme of the frontonasal mass (me(fn), Fig. 5L), various regions in the craniofacial surface ectoderm (se, Fig. 5D, G, K) and otocyst (O, Fig. 5J-L).

Figure 5. TCF/Lef-LacZ expression in transverse sections of an E11.5 mouse embryo.

Wnt signaling activity was visible in the ciliary margin (cm) of the developing eye, optic recess (or), and teeth placodes (t (pl)). It was also apparent at low levels in the dermal progenitor cells (dpc) and parietal bone progenitors (pdb) below the surface ectoderm (se). For additional labeled structures with β-gal expression, refer to the glossary.

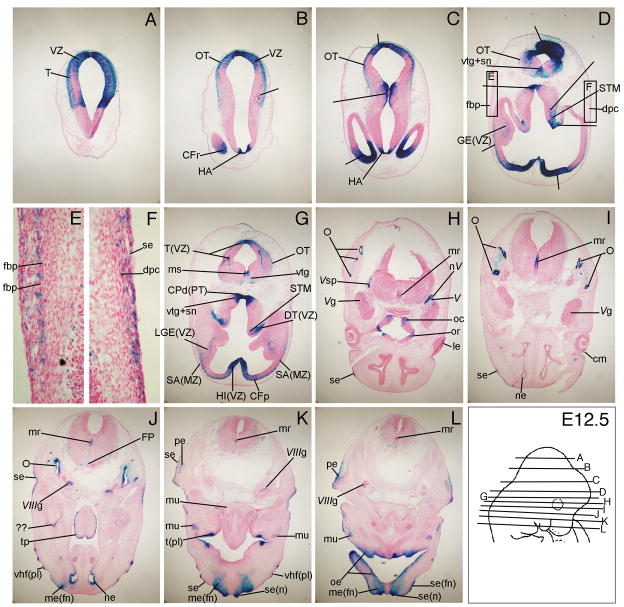

By E12.5, β-gal expression was prominent in new regions such as the cerebral peduncle (CPd(PT), Fig. 6G), ventral tegmental nucleus (vtg) and substantia nigra (sn, Fig. 6D, G), pinna of the ear (pe, Fig. 6K, L), vibrissae hair follicle placodes in the snout (vhf (pl), Fig. 6J, K), and the optic chiasma (oc, Fig. 6H). At E12.5, Wnt signaling reporter activity was also detected in all the same regions of the developing brain as described above at E11.5 (Fig. 6A-J). β-gal expression continued in the differentiating otocysts (O, Fig. 6H-J), tooth placodes (tpl, Fig. 6K), taste bud placodes in the tongue papillae (tp, Fig. 6J), ciliary margin (cm) and the lens epithelium (le) in the eye (Fig. 6H, I), subectodermal mesenchyme dermal progenitor cells (dpc) in the superciliary arch (Fig. 6F), and the mesenchyme and surface ectoderm of the frontonasal mass (me(fn), se(fn), Fig. 6K, L). Higher magnification views of TCF/Lef-LacZ expression at E12.5 in the developing eye, tongue papillae, and teeth placodes were shown in previously published reports (Liu et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2008). β-gal expression was clearly visible in the frontal bone progenitors (fbp) as they coalesced further below the surface ectoderm (Fig. 6D, E).

Figure 6. TCF/Lef-LacZ expression in transverse sections of an E12.5 mouse embryo.

β-gal expression was apparent in vibrissae follicle placodes (vhf (pl)), surface ectoderm (se) and mesenchyme (me) of the nostril (n) and frontonasal mass (fn), frontal bone primodria, and the subectodermal mesenchyme cells of the superciliary arch. For additional labeled structures withβ-gal expression, refer to the glossary.

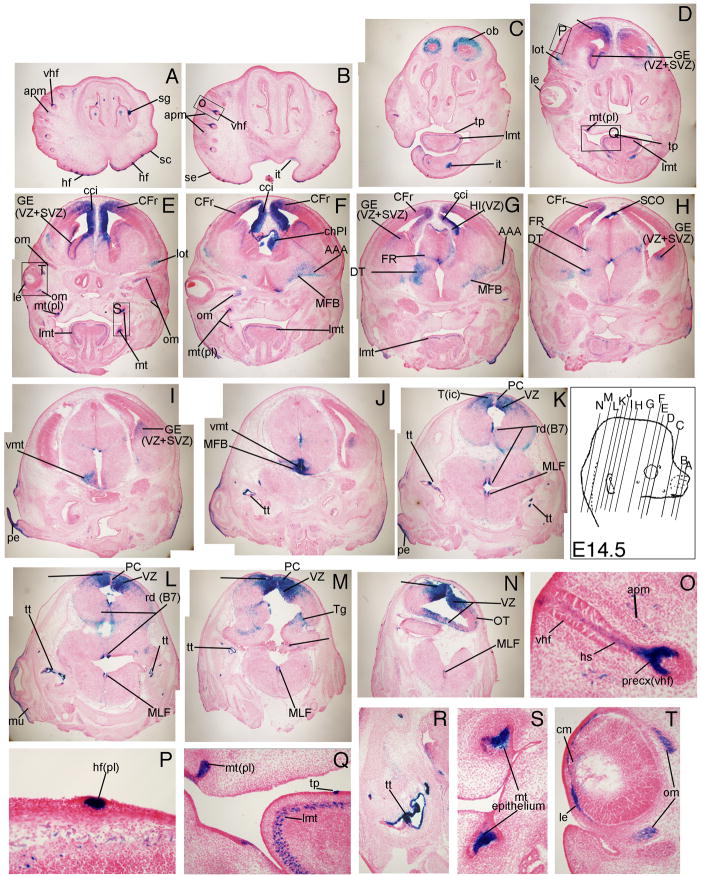

At E14.5, the differentiating brain and numerous ectodermal placode-derived structures had robust TCF/Lef-LacZ expression. In coronal sections of the developing brain, β-gal expression was seen in several regions of the cortex. The frontal cortex (CFr, Fig. 7D-H), the ventricular zone (VZ) and subventricular zone (SVZ) of the ganglionic eminence (GE, Fig. 7D, E, G-I), the anterior amygdala (AAA, Fig. 7F, G), and the choroid plexus (ChPl, Fig. 7F) demonstrated Wnt signaling reporter activity. In the midbrain region, the dorsal thalamus (DT, Fig. 7G, H), ventral medial thalamic nucleus (vmt, Fig 7I, J), and medial forebrain bundle (MFB, Fig. 7J) had β-gal expression. In the hindbrain, the tectum (T, Fig. 7K-N), posterior commissure (PC, Fig. 7K-M), the tegmentum (Tg, Figure 7M), choroid plexus (ChPl, Fig. 7M), medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF, Fig. 7K-N), nucleus raphae dorsalis (rd, Fig. 7K, L), and the optic tract (OT, Fig. 7N) had TCF/Lef-LacZ expression.

Figure 7. TCF/Lef-LacZ expression in coronal sections of an E14.5 mouse embryo.

Wnt signaling activity was visible in the hair follicle placodes (hf(pl) of craniofacial skin, longitudinal muscle of the tongue (lmt), tongue papillae (tp), olfactory bulb (ob), frontal cortex (CFr) and cingulated cortex (cci), ganglionic eminence (GE), choroid plexus (ChPl), anterior amygdaloid area (AAA), tectum in the hindbrain (T). For additional labeled structures with β-gal expression, refer to the glossary.

Also at 14.5, β-gal expression was visible in the serous glands of the nose and the outer wall of the olfactory bulb (ob, Fig. 7C). The emerging ectodermal thickening of hair follicle placodes in the craniofacial skin showed Wnt signaling reporter activity, unlike the underlying dermal condensates (Fig. 7A, B, D, F, N). The TCF/Lef-LacZ reporter expression pattern in the emerging hair follicle placodes was similar to published results using the TOPgal reporter (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999). In the vibrissae hair follicles (vhf), expression was also seen in the precortex (precx), hairshaft (hs), and the hair follicle-associated arrector pili muscle (apm, Fig 7O). The emerging molar teeth placodes (mt(pl)) expressed β-gal robustly only in the epithelium and not in the underlying mesenchyme (Fig. 7E, F, Q, S). β-gal expression was visible in the ectoderm of the tongue papillae (tp) and the longitudinal muscle of the tongue (lmt, Fig. 7C-G, Q). In the eyes, the lens epithelium (le), the ciliary margin (cm) and the extrinsic ocular muscles (om) had Wnt signaling reporter activity (Fig. 7E, T).

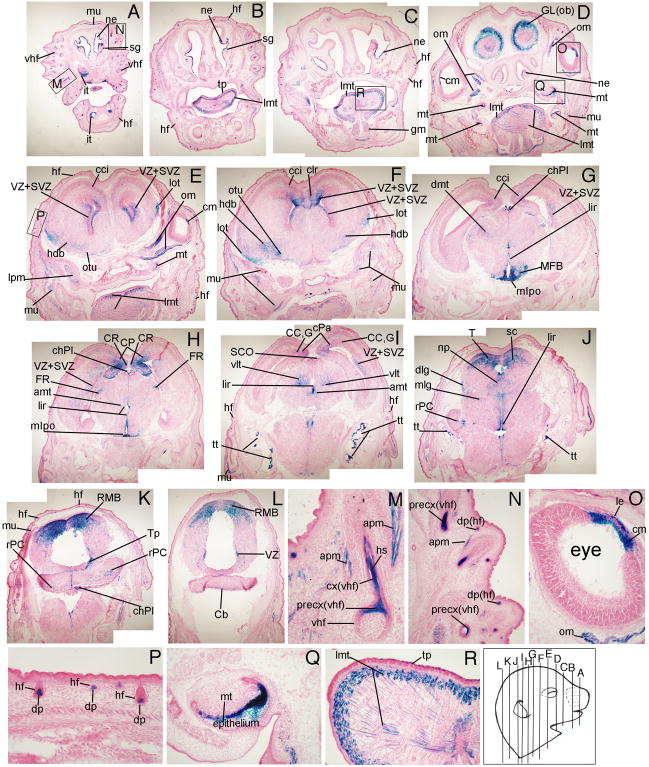

At E16.5, β-gal expression continued to be visible in all the structures identified at E14.5, as well as in additional regions of the frontal cortex region. Wnt signaling reporter activity was seen in the cingulate cortex (cci, Fig. 8E-G), claustrum (clr, Fig. 8F), corpus collosum (CC, Fig. 8I), and the cortical plate (CP, Fig. 8H). The broca area (hdb, Fig. 8E, F), glomerular layer of the olfactory bulb, the olfactory tubercle (otu, Fig. 8E, F), and the lateral olfactory tract (lot, Fig. 8E, F) expressed β-gal. In the midbrain region, the medial preoptic nucleus (mlpo, Fig. 8G, H), lining of the infundibular recess (lir, Fig. 8G-J), subcommissural organ (SCO, Fig. 8I), and roof of the midbrain (RMB, Fig. 8K, L) had TCF/Lef-LacZ expression. In the hindbrain, the lateral geniculate body in the medial (mlg) and dorsal (dlg) areas (Fig. 8J), developing cerebellum (rPC, Cb, Fig. 8J-L), and tegmentum of the pons (Tp) expressed β-gal (Fig. 8K).

Figure 8. TCF/Lef-LacZ expression in coronal sections of an E16.5 mouse embryo.

Wnt signaling activity was visible in the nasal epithelium (ne), incisor teeth (it) and molar teeth (mt) epithelium, lens epithelium (le) and ciliary margin of the retina (cm), precortex (precx) and hair shaft (hs) of vibrissae hair follicle (vhf), and dermal papillae (dp) of hair follicles in craniofacial skin. For additional labeled structures with β-gal expression, refer to the glossary.

In addition to the extrinsic ocular muscle of the eye (om, Fig. 8D, E, O) and longitudinal muscle of the tongue (lmt, Fig. 8B-E, R), Wnt signaling reporter activity at E16.5 was also seen in other muscles such as the genioglossus muscle behind the tongue (gm, Fig. 8C), the lateral pterygoid muscle (lpm, Fig. 8E), and the muscle under the skin (mu, Fig. 8I, K). At E16.5, β-gal expression was also seen in the medulla and the cortex of the vibrissae hair follicle shaft (cx(vhf), Fig. 8M) and was more defined in the arrector pili muscle (apm, Fig. 8M). Wnt signaling reporter activity was now detectable in the dermal papillae (dp) of the hair follicles (hf) in craniofacial skin (Fig. 8N, P) and in the nasal epithelium (ne, Fig. 8A-D). Wnt signaling reporter activity was seen more extensively in the tongue papillae (tp) and muscle (lmt, Fig. 8R), the ciliary margin (cm) of the developing eye (Fig. 8O), tympanic tubes (tt, Fig 8I, J), and the epithelium of molar teeth primordia (mt, Fig. 8Q).

Summary

Our characterization of TCF/Lef-LacZ expression represented the cumulative activity of canonical Wnt ligands and receptors. The whole-mount expression in the TCF/Lef-LacZ embryos was consistent with previously published work using the TOPgal and BATgal reporter lines for early embryos (E8.0–12.5) (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999; Maretto et al., 2003; Brugmann et al., 2007). The TCF/Lef-LacZ reporter expression pattern represents a combination of both the TOPgal and BATgal reporter lines. For instance, at E9.5 and E10.5, the TCF/Lef-LacZ reporter had prominent expression in the neuroepithelium of the forebrain, which is similar to the BATgal but not the TOPgal reporter mouse. However, at E10.5 in the distal branchial arch 1, TCF/Lef-LacZ expression is less prominent than BATgal, but similar to expression levels of the TOPgal reporter line (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999; Maretto et al., 2003; Brugmann et al., 2007). In sections, our results with TCF/Lef-LacZ reporter mouse were also consistent with TOPgal and BATgal expression in tooth development (Liu et al., 2008), taste bud development (Liu et al., 2007), eye development (Smith et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2006), early hair follicle placode formation in craniofacial skin and the differentiating vibrissae hair follicle development (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999). In our TCF/Lef-LacZ reporter expression results in sections at E14.5 and E16.5, we observed expanded expression in the developing tooth epithelium and in the cortex of the vibrissae hair follicle hair shaft compared to TOPgal reporter (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999; Liu et al., 2008). Using the same TCF/Lef-LacZ reporter line, we failed to find expression in the neuroblast layer of the retina at E14.5 and E16.5 that was reported in a later study by Liu et al., but not shown in an earlier study by the same group of authors (Liu et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2006).

Parr et al. reported overlapping and redundant expression of several Wnt ligands during the initiation of the central nervous system (CNS) from E8.0–9.5 (Parr et al., 1993). Recently, Fischer et al. characterized the mRNA expression of Frizzled receptors in the developing heads of E9.5–12.5 mouse embryos (Parr et al., 1993; Fischer et al., 2007). In this study, we show the combined activity of all the canonical Wnt ligands and receptors in the TCF/Lef-LacZ reporter expression in the developing areas of the early forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain in transverse and sagittal sections (Figs. 3–6). We have conducted detailed characterization of TCF/Lef-LacZ reporter expression in later stages of CNS development and in other structures such as the teeth, eye, tongue, and hair follicles at E14.5 and E16.5 (Figs. 7 and 8).

Several themes have emerged by systematically analyzing Wnt signaling reporter activity from E8.0–E16.5 at the whole mount level and in serial sections using a TCF/Lef-LacZ transgene reporter mouse. First, Wnt signaling activity can be detected early and persists during differentiation through late stages in development of the cortex, midbrain, inner ear, and teeth. In contrast, Wnt signaling activity was transient in other cells such as the subectodermal dermal progenitors (E11.5–12.5) and cranial bone progenitors (E11.5–13.5), suggesting an instructive role. In muscle associated with various organs, Wnt signaling reporter activity was visible only at late stages in embryonic development as the cells coalesce and form fibers (E14.5–16.5). Wnt signaling reporter activity in the brain appeared to be dynamic and became defined as tissues and different cell types emerged in the developing embryo (E14.5–16.5). The β-gal expression pattern in the TCF/Lef-LacZ mice demonstrates that Wnt signaling reporter activity was sustained in most craniofacial structures suggesting multiple or sequential roles in the development of tissues and organs.

Methods

Mice and genotyping

TCF/Lef-LacZ reporter mice were obtained from Daniel Dufort (Liu et al., 2003). The Hsp68 minimal promoter precedes multimeric TCF/Lef sites driving the LacZ reporter gene. CD1 male mice carrying one copy of the TCF/Lef-LacZ transgene were mated with wild type females. The day of vaginal plug formation was regarded as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). Mice and embryos were genotyped as previously described (Liu et al., 2003). For each stage, five to seven embryos from two to three litters were analyzed. All mouse experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Case Western Reserve University IACUC committee.

β-galactosidase staining and histology

Embryos were dissected in cold 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4. For whole mount β-gal staining, embryos were fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde fixative solution at 4°C. Embryos between E8.5–10.5 were fixed for 10 minutes, E11.5–12.5 were fixed for 15 minutes, and E13.5–14.5 were fixed for 25 minutes. After extensive washing in X-gal wash buffer (0.1% deoxycholate, 0.2% NP40, 2 mM MgCl and 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4) at room temperature, embryos were transferred into staining solution (1 mg/ml X-gal, 5 mM ferricyanide, 5 mM ferrocyanide in wash buffer) with 25mg/ml of X-gal at 4°C overnight. Embryos were further developed in staining solution at room temperature for an additional 3–5 hours. All steps were performed on a rotating platform providing gentle agitation. Whole mount embryo images were captured using a Leica MZ16F microscope, SPOT camera system, and SPOT software.

For histology, embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. Embryos between E8.5–9.5 were fixed for 10 minutes; 5 minutes were added for each additional day in development. Embryos were washed for 1–2 hours in cold PBS and equilibrated in sucrose gradients at 10% and 25%. Embryos were rinsed in OCT cryoprotective compound (TissueTek) and embedded in OCT in liquid nitrogen chilled methylbutane. Embryos were sectioned at 10–14 microns on a Leica CM3050 cryostat and stored at 80 deg C. Sections were air dried and stained for β-gal as previously described (Rivera-Perez et al., 1999). Bright-field images were captured using the Olympus BX60 microscope and Olympus DP70 digital camera using DC Controller software. All images were processed using Adobe Photoshop and Macromedia Freehand. Schematics of the head and identification of developing craniofacial structures were obtained from the mouse development atlas (Kaufman, 1992; Schambra et al., 1992).

Acknowledgments

We thank Charles Treloar and Diana Zuzindlak for their contributions. We thank the present members of the lab for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Startup funds from Case Western Reserve University (R.A.), National Institutes of Health-(R01-DE18470-2 from NIDCR) (R.A), and Case Western Reserve University/HHMI supported SPUR program (P.M.)

Glossary of Structures: Structures with TCF/Lef-LacZ expression A

A

- AAA

Anterior Amygdaloid Area

- amt

anterior medial thalamic nucleus

- apm

arrector pili muscle

B

- ba

branchial arch

- ba1m

branchial arch 1 membrane (future tympanic membrane)

C

- Cb

Cerebellum

- cci

cingulate cortex

- CFr

Frontal Cortex

- CFp

Frontopolar Cortex

- chPl

choroid Plexus

- clr

claustrum

- cm

ciliary margin of the retina

- Cme

Cephalic mesenchyme

- CNC

Cranial Neural Crest

- CC, G

Corpus Callosum, genu

- CP

Cortical Plate

- CPa

Parietal cortex

- CPd (PT)

Cerebral Peduncle (pyramidal tract)

- CR

Retrospinal cortex

- cx(vhf)

cortex of (vibrissae hair follicle)

D

- d

distal

- (d)me(ba1)

(distal) mesenchyme (branchial arch1).

- dlg

dorsal lateral geniculate body

- dmt

dorsomedial thalamic nucleus

- dp

dermal papilla

- dpc

dermal progenitor cells

- DT

Dorsal Thalamus

E

- E

Eye

- e

ectomesenchyme

F

- FB (p)

Forebrain, (presumptive)

- fCNC(ba2)

facial cranial neural crest tissue (branchial arch2)

- fbp

frontal bone progenitors

- fn

frontonasal mass

- FR

Fasciculus retroflexus (habenulo-peduncular tract)

- FP

Floor plate

G

- GE

Ganglionic Eminence

- GL

Glomerular layer of the olfactory bulb

- gm

genioglossus muscle

H

- HA

habenula

- Hb (w)

Hindbrain (wall)

- hdb

horizontal nucleus of diagonal band of Broca

- HI(VZ)

Hippocampus (ventricular zone)

- hf

hair follicle

- hs

hair shaft

I

- Ir

Infundibular recess

- ic

inferior (posterior) colliculus

- it

incisor tooth primordium

- IZ

Intermediate Zone

L

- le

lens epithelium

- lcb

lateral cerebellar nucleus

- LGE

Lateral Ganglionic Eminence

- lir

lining of the infundibular recess of the 3rd ventricle

- lmt

longitudinal muscle of the tongue

- lpm

lateral pterygoid muscle

- lot

lateral olfactory tract

- LT

Lamina Terminalis

M

- max

maxillary component of (ba1, e)

- MB

Midbrain

- me

mesenchyme

- MFB

medial forebrain bundle

- MHB

Midbrain-Hindbrain boundary

- MLF

Medial longitudinal fasciculus

- mlg

medial lateral geniculate body

- mlpo

medial preoptic nucleus

- mr

medulla raphae

- ms

median sulcus

- mt

molar tooth

- mu

muscle

N

- N

Neuroepithelium

- n(d)

nostril (distal)

- ne

nasal epithelium

- np

nucleus proprius of posterior commissure

O

- O

otocyst

- ob,(w)

olfactory bulb, wall

- oc

optic chiasma

- Oc

optic cup (future nervous layer of the retina)

- oe

oral ectoderm

- oep

oral epithelium

- om

ocular muscles, extrinsic

- op

otic placode

- or

optic recess

- otu

olfactory tubercle

- OST

Optic Stalk

- OT

Optic Tract

- OV

Otic Vesicle

P

- pO(V CNC)

perioptic neural crest tissue of trigeminal (V) neural crest origin

- pbp

parietal bone progenitors

- PC

posterior commissure

- pe

pinna of the ear

- pl

placode

- precx(vhf)

precortex of (vibrissae hair follicle)

R

- rd(B7)

nucleus raphe dorsalis (B7)

- RHB

Roof of Hindbrain

- RMB

Roof of Midbrain

- rPC

rostral extension of Primitive Cerebellum

S

- SA, (MZ)

Septal Area (marginal zone)

- sc

superior (anterior) colliculus

- sca

superciliary arch

- se

surface ectoderm

- sg

serous glands

- sn

substantia nigra

- SCO

Subcommisural organ

- STM

Stria medullaris

- SVZ

Subventricular zone

T

- T

Tectum

- Te

tongue ectoderm

- Tg

tegmentum

- Tp

tegmentum of pons (basal plate)

- tt

tympanic tubes

- tp

Tongue papillae

- t(pl)

teeth (placode)

- TV(w)

Telencephalic vesicle(wall)

V

- vhf

vibrissae hair follicle

- vlt

ventrolateral thalamic nucleus

- vmt

ventromedial thalamic nucleus

- VZ

Ventricular zone

- vtg

ventral tegmental nucleus

Roman Numerals

- V

Trigeminal nerve

- V CNC

Trigeminal cranial neural crest

- Vg

Trigeminal ganglion

- Vsp

spinal tract of Trigeminal nerve

- nV

Trigeminal nucleus

- VII

Facial nerve

- VIIIg

Acoustic (spiral) ganglion

- IX-X CNC

Glossopharyngeal-vagal cranial neural crest complex

References

- Brugmann SA, Goodnough LH, Gregorieff A, Leucht P, ten Berge D, Fuerer C, Clevers H, Nusse R, Helms JA. Wnt signaling mediates regional specification in the vertebrate face. Development. 2007;134:3283–3295. doi: 10.1242/dev.005132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, Nusse R. Wnt signaling: a common theme in animal development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3286–3305. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta R, Fuchs E. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development. 1999;126:4557–4568. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer T, Guimera J, Wurst W, Prakash N. Distinct but redundant expression of the Frizzled Wnt receptor genes at signaling centers of the developing mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2007;147:693–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haegel H, Larue L, Ohsugi M, Fedorov L, Herrenknecht K, Kemler R. Lack of beta-catenin affects mouse development at gastrulation. Development. 1995;121:3529–3537. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MH. The atlas of mouse development. London, England: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Klaus A, Birchmeier W. Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:387–398. doi: 10.1038/nrc2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Chu EY, Watt B, Zhang Y, Gallant NM, Andl T, Yang SH, Lu MM, Piccolo S, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Taketo MM, Morrisey EE, Atit R, Dlugosz AA, Millar SE. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling directs multiple stages of tooth morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;313:210–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Thirumangalathu S, Gallant NM, Yang SH, Stoick-Cooper CL, Reddy ST, Andl T, Taketo MM, Dlugosz AA, Moon RT, Barlow LA, Millar SE. Wnt-beta-catenin signaling initiates taste papilla development. Nat Genet. 2007;39:106–112. doi: 10.1038/ng1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Mohamed O, Dufort D, Wallace VA. Characterization of Wnt signaling components and activation of the Wnt canonical pathway in the murine retina. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:323–334. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Thurig S, Mohamed O, Dufort D, Wallace VA. Mapping canonical Wnt signaling in the developing and adult retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:5088–5097. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig B, Jerchow B, Sachs M, Weiler S, Pietsch T, Karsten U, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Schlag PM, Birchmeier W, Behrens J. Negative feedback loop of Wnt signaling through upregulation of conductin/axin2 in colorectal and liver tumors. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1184–1193. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1184-1193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maretto S, Cordenonsi M, Dupont S, Braghetta P, Broccoli V, Hassan AB, Volpin D, Bressan GM, Piccolo S. Mapping Wnt/beta-catenin signaling during mouse development and in colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3299–3304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434590100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson WJ, Nusse R. Convergence of Wnt, beta-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science. 2004;303:1483–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.1094291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama T, Mohamed OA, Taketo MM, Dufort D, Groves AK. Wnt signals mediate a fate decision between otic placode and epidermis. Development. 2006;133:865–875. doi: 10.1242/dev.02271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr BA, Shea MJ, Vassileva G, McMahon AP. Mouse Wnt genes exhibit discrete domains of expression in the early embryonic CNS and limb buds. Development. 1993;119:247–261. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Perez JA, Wakamiya M, Behringer RR. Goosecoid acts cell autonomously in mesenchyme-derived tissues during craniofacial development. Development. 1999;126:3811–3821. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schambra UB, Lauder JM, Silver J. Atlas of prenatal mouse brain. San Deigo, CA: Academic Press; 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AN, Miller LA, Song N, Taketo MM, Lang RA. The duality of beta-catenin function: a requirement in lens morphogenesis and signaling suppression of lens fate in periocular ectoderm. Dev Biol. 2005;285:477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele RE. Developmental signaling in Hydra: what does it take to build a “simple” animal? Dev Biol. 2002;248:199–219. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Vivatbutsiri P, Morriss-Kay G, Saga Y, Iseki S. Cell lineage in mammalian craniofacial mesenchyme. Mech Dev. 2008;125:797–808. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaghetto AA, Paina S, Mantero S, Platonova N, Peretto P, Bovetti S, Puche A, Piccolo S, Merlo GR. Activation of the Wnt-beta catenin pathway in a cell population on the surface of the forebrain is essential for the establishment of olfactory axon connections. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9757–9768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0763-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]