Abstract

B-cell type chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has long been considered a disease of resting lymphocytes. However cell surface and intracellular phenotypes suggest that most CLL cells are activated cells, although only a small subset progresses beyond the G1 stage of the cell cycle. In addition, traditional teaching says that CLL cells divide rarely, and therefore the buildup of leukemic cells is due to an inherent defect in cell death. However, in vivo labeling of CLL cells indicates a much more active rate of cell birth than originally estimated, suggesting that CLL is a dynamic disease.

Here we review the observations that have led to these altered views of the activation state and proliferative capacities of CLL cells and also provide our interpretation of these observations in light of their potential impact on patients.

Keywords: B lymphocyte, Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Cell proliferation, Kinetics, Antigen receptor, Antigen

I. INTRODUCTION

Historically, CLL cells were considered to be resting lymphocytes. However in recent years, several studies have identified cell surface and intracellular phenotypes suggesting instead that most CLL clones comprise activated cells, the vast majority of which have not progressed beyond the G1 stage of the cell cycle. Furthermore, the classical view of CLL is of a clone with minimal proliferative capacity in vivo, but without the capacity to die. However, in vivo labeling of CLL cells has indicated a much more active rate of cell birth than originally estimated.

Cellular activation and proliferation can be identified in multiple ways. For example, prior activation can leave indelible imprints in daughter cells, whereas recent and ongoing events can manifest as expression of molecules that change in a continuing manner. Similarly, cellular proliferation can be analyzed by either direct or indirect means on ex vivo samples or in vivo in patients or healthy subjects.

In this short review, we will highlight the ex vivo and in vivo observations that have led to the current view that CLL cells are activated and that more cells than originally anticipated can go through the entire cell cycle and proliferate. We will also provide our interpretation of these observations in light of their potential impact on patients.

I. CLL cells display transient/ongoing changes consistent with cellular activation

A. Surface membrane phenotype

Although microscopically CLL cells appear as small resting cells, detailed phenotypic analyses reveal that they express a plethora of surface molecules associated with B lymphocyte activation. In particular, two molecules - CD38 and ZAP-70, expressed by activated T and B cells1,2 and a subset of CLL cells3–5 - have received special attention because of their ability to predict clinical outcome in CLL patients4–8. Both molecules have been studied extensively, and their accessory role in B-cell receptor (BCR)-mediated signal transduction in CLL has been demonstrated9,10.

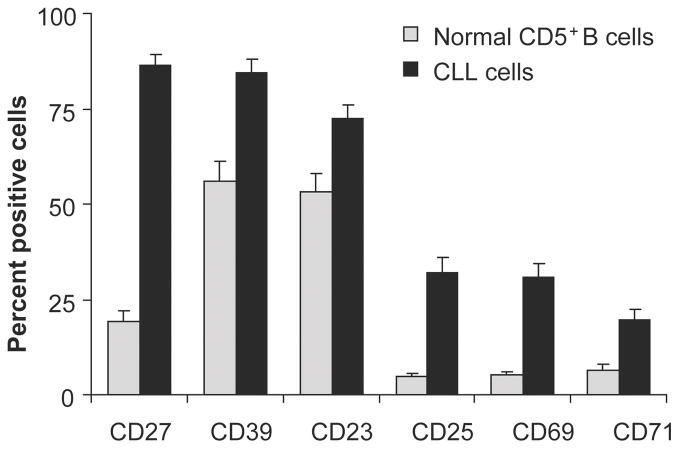

In addition, circulating CLL cells display other activation- and maturation- associated markers such as CD23, CD25, CD27, CD69, CD71 and elevated density of HLA-DR3,11–14 (Figure 1). When the expression of some of these molecules was analyzed in CD38+ and CD38− fractions of individual CLL clones, significantly more cells in the CD38+ fraction of the clone expressed these markers as compared to their CD38− counterparts15. These studies suggested that CD38 expression labeled an activated subset within CLL clones15; this concept was subsequently formally proven by in vivo studies labeling cycling clonal members16,17.

Figure 1. CLL clones contain more cells displaying an activated phenotype than CD5+ B cells from healthy subjects.

After gating on CD19+CD5+ cells, expression of various surface markers indicative of cellular activation were determined. Only those markers that were expressed significantly more on CLL cells are displayed.

From R.N. Damle et al. “B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells express a surface membrane phenotype of activated, antigen-experienced B lymphocytes”. Blood. 2002; 99: 4087–4093.

Expression of an activated phenotype is not limited to circulating CLL cells. Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated the presence of proliferating CLL cells within specific micro-environmental structures, known as pseudofollicles or proliferation centers, found in lymph nodes (LN) and bone marrow (BM)18,19. The immunophenotype of cells within such structures also resembles that of activated B lymphocytes; however, it differs somewhat from circulating CLL cells by even greater densities of expression of CD23 and CD38 in addition to presentation of proliferation-associated markers, such as CD71 and Ki-6718–20. These findings suggest that solid lymphoid tissues are a preferred site for CLL cell proliferation.

CLL cells receive signals that enable them to survive and proliferate as do normal B cells; these signals come from interactions with neighboring cells or soluble factors in their microenvironment. In an attempt to understand cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions several investigators have studied ligand-receptor pairs expressed by CLL cells and their neighboring clonal members. CD40 is present on all B cell surfaces (both tumor and normal), whereas its ligand (CD40L), usually undetectable on resting normal B lymphocytes, can be expressed on cells from many CLL cases21. CD27 and its ligand, CD70 can also be co-expressed by cells from several CLL cases22. The observation that several receptors and their ligands (i.e., CD40/CD40L, CD30/CD30L, and CD27/CD70) can be expressed on the same cell suggests these molecules play a role in initiating and maintaining the neoplastic process by mediating B-T and B-B interactions23.

In addition, in the context of T cell cross-talk, CD4+ CLL cells have been identified in the pseudofollicle/proliferation centers of CLL cells20 and their physical contact with CLL cells suggests an important role in te activation and survival of CLL cells24. Nevertheless, the T-cell compartment in CLL may not be normal. For example, oligoclonality of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations is substantially more frequent in CLL patients than in age-matched controls25. Moreover, CLL cells serve poorly as antigen presenting cells26, and T cells in CLL respond poorly to inductive stimuli27,28. In addition, the levels of T-regulatory cells in CLL, in particular in proliferation centers, can be increased29. Thus, T cells in CLL may be unable to start, maintain, and complete an immune response to the malignant B cells and other antigens and may be directly involved in sustaining the tumor. Recently, defective actin polymerization was identified in T cells from patients with CLL, which in turn results in both CD4+ and CD8+ cells exhibiting defective immunological synapse formation with antigen presenting cells including B cells30. The extent that this defect affects the ability to activate CLL cells but prevent complete progression through of the cell cycle has not been evaluated.

B. Signaling pathway-specific biochemical intermediates

The expression and modification of key molecules involved in signaling pathways are also indicators of cellular activation. In CLL, transient changes in molecules temporarily modified (e.g., phosphorylated) by signals originating from the BCR have been examined the most. A proportion of CLL clones that were unresponsive to surface membrane Ig cross-linking were found to constitutively express (a) phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 in the absence of AKT activation, (b) phosphorylated MEK1/2, and (c) increased transactivation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NF-AT). Although exhibiting features of activated B cells, such a molecular profile recapitulates the signaling pattern of anergic murine B cells31, consistent with the inability of these cells to respond to BCR engagement in vitro. Therefore, constitutive activation of mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling pathway along with NF-AT transactivation in the absence of AKT activation in CLL cells could be the molecular signature of anergic human B lymphocytes.

Similarly, constitutively activated phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI-3K) has been detected in CLL cells and has been suggested as a means whereby the leukemic cells avoid apoptosis32. Finally, constitutively phosphorylated STAT-1 and STAT3 were observed in all CLL samples analyzed, whereas such phosphorylation was only found sporadically in other hematologic malignancies suggesting that CLL cells are not merely transformed but are likely also dividing33. The presence of cdk4 and cyclin E in the blood cells of the majority of CLL cases studied, as well as cdk1 and cdk2 in some cases, indicates that the CLL cells are not quiescent, but are blocked in an early stage of the G1 cell cycle phase, and/or that the expression of these proteins is dysregulated34.

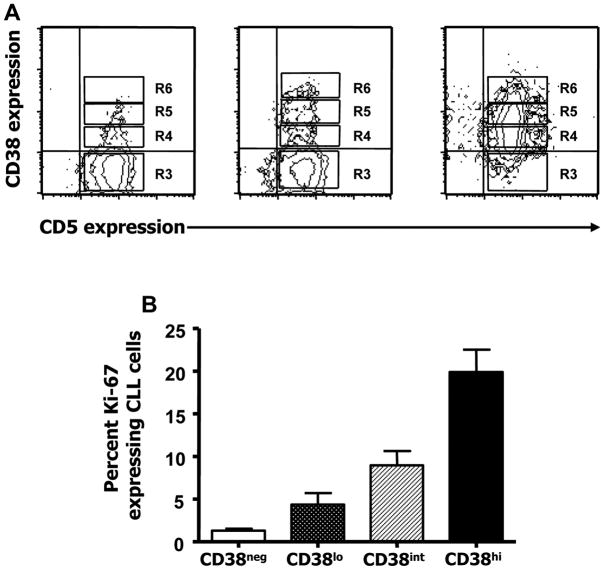

Ki-67 protein is found within the nucleus and nucleolus of cells during the late G1 phase and throughout the S, G2, and M phases of the cell cycle35–37. The percentage of cells expressing Ki-67, protein within members of individual CLL clones increases as the density of expression of CD38 increases15 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Within CLL clones, the numbers of Ki-67+ cells increases with the density of CD38 expression.

A. After gating on CD19+CD5+ cells, CD38+ cells were divided into 3 fractions (R4, R5, and R6) corresponding to CD38low, CD38int, and CD38high expression. B. Average percentages of Ki-67+ cells in the three CD38-density defined subsets.

From R.N. Damle et al. “B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells express a surface membrane phenotype of activated, antigen-experienced B lymphocytes”. Blood. 2002; 99: 4087–4093.

C. Telomere lengths

Reduction in the length of the chromosome-capping structures, telomeres, accompanies cell division. In addition, this shortening in telomere length is counteracted by activation of telomerase, the enzyme that restores the eroded terminal nucleic acids. Therefore, this dynamic process is another marker for cell activation and proliferation in vivo.

In this regard, mature B cells stimulated through their antigen receptor upregulate expression and function of this immortality conferring enzyme, telomerase38. In general, CLL cells exhibit elevated telomerase activity39, especially in cases with poor clinical outcome40.

Despite this elevation in telomerase, when the telomere lengths of CLL cells were compared with those of age-matched normal CD5+ B lymphocytes, the lengths in most CLL clones were clearly shorter, indicating a more extensive proliferative history. Furthermore, when CLL cases were divided into subgroups based on IGHV mutations, unmutated CLL clones exhibited significantly shorter mean telomere lengths than mutated CLL clones, suggesting that the leukemic cells from clinically aggressive, unmutated CLL cases have cycled more often. This cycling could be cell autonomous or the response to signaling through various cell surface receptors. In support of the latter possibility, unmutated CLL cases have been shown to be more responsive to BCR stimulation than mutated CLL clones41–43, suggesting that they may encounter antigen intermittently in vivo.

D. Methylation

Epigenetic alterations, including gain or loss of DNA methylation which are hallmarks of most malignancies, are reversible changes that are aggressively being investigated as potential therapeutic targets in CLL. Since transient changes in DNA methylation can impact expression of cancer-related genes including apoptosis regulators and tumor suppressors, the level of cytosine methylation was analyzed in a cohort of 81 CLL patients. Multivariate analysis revealed a significant correlation of DNA methylation level with IGHV mutation status suggesting that methylation level might be a valuable factor in determining the prognostic outcome of CLL44. Other groups have reported that progression of CLL is correlated with the DNA methylation index45,46.

Research agenda

▪ A comparison of CLL cases based on various types of transient/ongoing changes indicative of cellular activation may reveal key differences in gene and protein expression related to the clonal proliferative capacities in different patients.

II. CLL cells display permanent changes consistent with cellular activation

The existence of somatic mutations in genes encoding the Ig V regions of an antibody molecule (the B cell’s receptor for antigen) indicates previous cellular activation, presumably through antigen encounter47. Such mutations in DNA are permanent and therefore serve as indelible signs of cellular activation.

The first suggestion that some CLL clones might express mutated IGHV was provided by a review of the available DNA sequences in the literature48; although the sample size was small, these findings were provocative. Subsequently a large prospective study documented that ~50% of CLL cases expressed mutated IGHV49. Of note, the presence of somatic mutations was not uniform among cases, but tracked with individual IGHV genes. For example, CLL clones using the IGHV1-69 gene exhibited very few, if any mutations, whereas those using IGHV3-07, IGHV3-23 and IGHV4-34 genes exhibited a much higher number of mutations49. This study also highlighted the biased use of specific IGHV among CLL B cells and documented that CLL cases could be segregated into two groups based on the presence or (relative) absence of IGHV mutations.

This and subsequent studies50,51 demonstrated that cellular activation had occurred in at least the subgroup of cases with mutated IGHV genes. However further analyses of CLL cells, analyzing surface membrane phenotype3 and gene expression52,53 documented that even the CLL cases with unmutated IGHV likely had undergone multiple cell divisions, consistent with CLL cells as being an activated subset of B lymphocytes.

III. Despite their activated surface membrane and intracellular phenotypes, most CLL cells do not complete the cell cycle

Cell proliferation is a highly regulated process that depends on the precise duplication of DNA in each cell cycle. Passage through the cell cycle is controlled by the cyclins and their catalytic subunits, the cyclin dependent kinases (CDK)54. For example, cyclin D1, D2, and D3 are responsible for the initiation of G1. The relative abundance of the cyclins varies throughout the cell cycle in response to growth signals, while CDK levels remain relatively constant.

Although CLL cells display features of activated cells, the majority do not undergo cellular proliferation. The presence of cdk4 and cyclin E in the blood cells of the majority of CLL cases studied, as well as cdk1 and cdk2 in some cases, indicate that the CLL cells are not quiescent, but are blocked in an early stage of the G1 cell cycle phase, and/or that the expression of these proteins is pathologically dysregulated55.

CLL cells characteristically exhibit elevated levels of cyclins D1 and D3. In fact, cyclin D mRNA levels correlate significantly with patient survival, with patients having high levels of cyclin D1 and to a lesser extent cyclin D3 mRNA, having long lymphocyte doubling times and longer survival56. In contrast, increased Ki-67 positivity was found in the CD38+ fraction of CLL clones 15 and correlated with the fractions of CLL clones containing 2H-DNA from patients who had drunk deuterated water17.

IV. CLL cells exhibit significant turnover in vivo

The preceding sections document that CLL cells resemble activated human B lymphocytes, although it is not known how much of this “activation” is receptor-mediated vs. receptor-independent. Based on the marked restrictions in IGHV gene use and association57,58, it is presumed that at least some of this cellular activation is BCR-mediated. Also based on in vitro studies using ligands that signal through other receptors, it is believed that some of this activation could be mediated through CD4059 and Toll-like receptors60. However, one must not lose sight of the fact that only a small fraction of CLL cells progress through the entire cell cycle so as to result in the creation of daughter cells.

CLL cell proliferation appears to occur primarily within solid lymphoid tissues, LNs more than BM or spleen. Its kinetics have been difficult to study because little happens in blood, a readily available source of cells, while much happens in solid tissues, a relatively unavailable source of cells since sampling is not usually clinically necessary.

Quantification of CLL cell birth rates halted in the early 1980s, primarily because ethics precluded the use of radioactive agents as labeling compounds. The absence of a way to safely and accurately quantify cell proliferation and the scarce availability of solid tissues where proliferation likely occurs prevented measurement and understanding of Kb (cell birth rate) while exaggerating the role of Kd (cell death rate).

Given a value of the ratio of cell birth to cell death rates, a mass of cells will expand if this ratio, Kb/Kd, is >1. For decades CLL has been labeled an accumulative disorder of apoptosis-resistant cells. According to this view, Kb/Kd is >1 only because Kd is negligible. Indeed, high levels of anti-apoptotic molecules have been detected in CLL cells; however, the same cells die very quickly by apoptosis when cultured ex-vivo suggesting more complex scenarios. Moreover, even if a minimal Kd is an important mechanism for tumor expansion in vivo, the Kb/Kd ratio is less meaningful without a precise measurement of Kb. Recently, the utilization of deuterium (2H) to label newly synthesized DNA61,62 provided an extremely precise and safe way to measure cell kinetics in vivo.

A. Lymphocyte proliferation in CLL

Pivotal studies on CLL kinetics were initiated in the 1960s, first ex vivo63 and then in vivo64–66. However, the initial studies were undertaken before the realization that there were three types of lymphocytes (T, B, and NK cells), indistinguishable on a blood smear. This complexity has become even more daunting with the recognition of multiple subsets within each of these lymphocyte categories and caution should be exercised in making parallels between results obtained over the past four decades. Moreover, because these initial studies involved infusion of radioactive compounds and in some instances employed cumbersome techniques such as extracorporeal irradiation of blood, only a few patients were studied. Considering the heterogeneity in cellular and molecular events that characterize CLL57,58, require that these observations be confirmed in a larger cohort of patients.

Finally, virtually all CLL kinetic data reported to date have been derived from cells circulating in the blood. How much cell turnover happens in the periphery compared to in solid lymphoid tissues, and how and how quickly do the compartments equilibrate, is not easy to estimate but must be taken into account. There is general agreement, however, that solid lymphoid tissues are the preferential sites of CLL cell division; hence, we need to recognize that data recorded in blood are echoes of events that occurred elsewhere.

Nevertheless, using 3H-thymidine to label newly synthesized DNA in vivo, production of 0.24% to 0.35% of new CLL cells per day was calculated by Theml et al.65 and of 0.10% to 0.40% by Dormer et al.66. These numbers are similar to those calculated more recently using deuterium (2H), taken in the form of “heavy water”16 or deuterated glucose67,68, i.e., ranging from 0.08% to 1.76% of the clone per day.

Although it appears that CLL cells may proliferate at rates lower than B cells from healthy subjects64–68, the absolute daily production of lymphocytes is quite high. Based on the birth rates reported by Messmer et al., the absolute number of new CLL cells produced daily is of the order 1×109 to 1×1012. In addition, 3H-thymidine uptake studies suggest that CLL patients can produce the number of new lymphocytes in 4 days that a healthy individual would make in one year65.

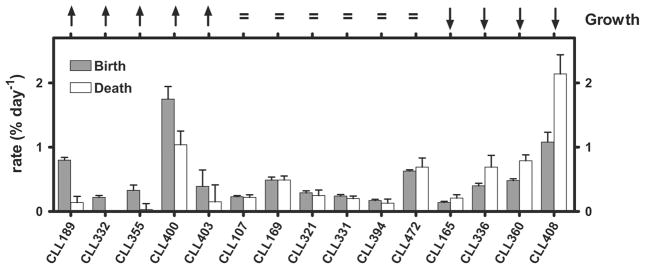

Furthermore, in each of the studies using 2H-labeling death rates for CLL cells were calculated and suggested that they could approximate that of the birth rates in the same patients. These data explain why the slope of CLL cell increase over time in some patients is minimal, and they contrast with a long held belief that CLL is a disease of accumulation and its aggressiveness and invasiveness were due to anti-apoptotic mechanisms. Of note, others had previously suggested that the latter might not be the case69–71. Collectively, the values calculated in these three studies indicate that an entire CLL clone could turnover in ~57 to 1,250 days, confirming that CLL is a dynamic disease comprised of birthing and dying cells (Figure 3). Because the study by Messmer et al. suggested that patients with the higher daily birth rates had more active disease16, cell cycling and not longevity may be a key to clonal evolution and disease worsening16,17.

Figure 3. Birth and death rates in CLL patients are reciprocally related.

Growth rate trends are indicated across the top. Birth rates (gray bars) and death rates (white bars) are reciprocally related, based on growth rates (top of figure).

From B.T. Messmer et al. “In vivo measurements document the dynamic cellular kinetics of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells”. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 755–764.

B. Where does proliferation occur?

Proliferation in LNs exceeds that in the blood for CLL cells65,66 as well as for normal B cells72. Proliferative spots containing clusters of 3H-thymidine labeled cells were described in autoradiographs of CLL LNs66, and LNs exhibited a higher number of 3H-thymidine labeled cells compared to blood65. Moreover, a higher percentage of Ki-67+ CLL cells have been found in LN as compared to peripheral blood73.

As mentioned in IA, LNs contain structures called pseudo-follicles or proliferation centers. These are found in CLL and in some autoimmune diseases. In CLL, the areas mainly consist of CLL cells of different sizes, T cells, and follicular dendritic cells74. Such areas indicating proliferative activity have also been observed in BM in early stages of their disease (Rai stage 0-I-II), albeit less often than in LNs; with disease progression, a more dispersed “packed” appearance is found in BM75. This suggests that CLL cells find the BM to be an optimal site for rapid expansion initially, whereas cell division continues in LNs once the disease has spread more massively. Whether BM continuously represents a site of proliferation or eventually becomes simply a location that offers strong survival cues for previously born cells is under debate. Kinetics studies in which BM was sampled in parallel with other compartments suggest that CLL cells proliferate elsewhere65,68. This is consistent with recent studies indicating that although the percent of newly produced cells measured by 2H incorporation was higher in BM compared to PB, similar levels of Ki-67+ cells were observed at both sites, suggesting that 2H-labeled cells proliferated elsewhere and took residence inside the BM subsequently68.

C. Life span of CLL cells

The evaluation of the lymphocyte life span is challenging because the disappearance of labeled cells from the blood may not only be due to their death but to other factors. For example, labeled cells may migrate to an extra-vascular space or members of the clone could change phenotype over time17. Nevertheless these types of studies can provide significant insights.

For example, the studies utilizing 2H-incorporation into DNA found labeled cells in the blood from 300 to more than 500 days after discontinuation of 2H2O intake16,68; similarly, 3H-labeling identified 3H-marked cells up to 1 year after infusion65. The latter studies65 led to the observation of short lived, large lymphocytes that disappear almost completely within 3 weeks and long lived, small lymphocytes (90% of labeled cells) still detectable one year later. Considering that cell death of activated and proliferating T and B cells maintains steady-state cell numbers over time76,77, the reported data may underestimate the survival of non-dividing CLL cells, which is the majority of the clone.

Disappearance rates of labeled cells have been calculated and fall within the range of 0.0% to 5.9%/day16,66–68. A 0.0% disappearance rate means no loss of newly divided cells over the period of observation. It appears to be a feature of some CLL patients in several kinetics studies, although never observed in B cells of healthy subjects. In CLL, cell disappearance has been correlated with clinical behavior64,66, and to expression of CXCR4 levels17. Overall, it appears that newly divided CLL B cells disappear from the blood more slowly than healthy B cells67,68. How much this relates to a defect in trafficking and how much to an intrinsic survival feature of CLL cells is presently not known.

Research agenda

▪ An analysis of the time that CLL cells spend in the blood and the time that is necessary for cells to re-appear in the blood after their exit would be very helpful, especially if this took into account the intraclonal heterogeneity of most CLL clones

D. Complexity of intra-clonal kinetics complexity

As mentioned, CLL clones circulating in the blood were previously viewed to be a homogeneous mass of small, resting lymphocytes. Although true for the majority of cells in a clone, careful review of blood smears often reveals a small fraction of larger cells. Theml et al. observed that large and small lymphocytes collected from the blood have dramatically different kinetics and are represented at different levels in solid tissues65. Although only two patients were studied, higher birth rates were observed for large lymphocytes (5.5% in one patient and 7.5% in the other), with correspondingly lower values (0.25% and 0.35%) calculated for small lymphocytes in the same subjects. A faster appearance rate was matched by a faster disappearance rate, so that labeled large lymphocytes tended to disappear from blood by 60 days after 3H-thymidine discontinuation, whereas labeled small lymphocyte where still detectable at day 222.

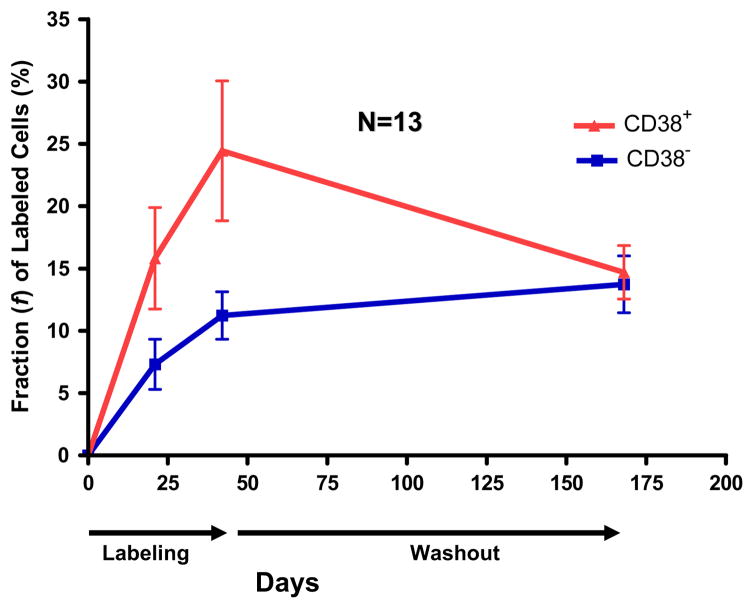

The use of monoclonal antibodies and flow cytometry to define cell phenotypes now provides a very efficient tool to dissect intra-clonal kinetic heterogeneity. Calissano et al.17 found that each patient’s clone is comprised of two fractions, defined by the surface membrane expression of CD38, and that these two fractions differ in birth rates in vivo (Figure 4). On average, CD38+ cells incorporated 2.5 times more 2H than CD38− counterparts of the same clone. CD38+Ki67+ cells incorporated even more 2H, reaching levels 2 – 30 times higher than those recorded previously. This is line with an in vitro study indicating that the fraction CD38+ of a CLL clone is enriched in Ki-67+ cells15. Dissection of such intraclonal kinetic heterogeneity may help to precisely identify highly proliferating cells and to discriminate how dividing and resting cells differ at the molecular level.

Figure 4. Intraclonal kinetic heterogeneity: within each clone the CD38+ fraction is enriched in proliferating cells.

After sorting CD19+CD5+CD3− cells, based on CD38 expression 2H incorporated into DNA was measured by gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. Figure illustrates the average of data from CD38+ and CD38- fractions from 12 CLL patients. Notice that the CD38+ fraction contains significantly more 2H-labeled DNA during the labeling period, and this equilibrates during washout.

Adapted from C. Calissano et al. “In vivo intraclonal and interclonal kinetic heterogeneity in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia”. Blood 2009; 114: 4832–4942.

CXCR4 and CD5 densities on the CLL cell surface provide another way to isolate cells that have recently proliferated17. The portion of the circulating clone which recently left a solid tissue after dividing is CXCRdimCD5bright, while the portion about to traffic back is CXCR4brightCD5dim. Expression of high levels of CXCR4 presumably permits cells to detect and follow a CXCL13/SDF-1 chemokine gradient17.

Furthermore, within each clone, the CXCR4dimCD5bright fraction proliferates on average 10 times faster than its CXCR4brightCD5dim counterpart, as indicated by in vivo incorporation of 2H in sorted cells (Calissano et al., manuscript in preparation). These two fractions also differ dramatically in terms of their phenotype and gene expression profiles, with CXCR4dimCD5bright cells expressing higher levels of several activation- and trafficking- related molecules, including CD38.

As observed for the generally larger highly proliferating cells that also tend to disappear earlier from PB65, CXCR4dimCD5bright 2H-labeled cells have a larger volume (determined by physical parameters in flow cytometry), and disappear from blood more rapidly than their CXCR4brightCD5dim counterparts. However, as discussed above, how differences in disappearance rates are related to phenotype changes, differential extra-vascular recirculation, or cell death is presently not clear. However, what does emerge is a dynamic life cycle among circulating CLL cells which seems to correspond to different “ID cards” for proliferating vs resting cells. This may eventually permit the development of new therapeutic strategies that specifically target these different clonal fractions.

V. Relevance of the above findings to a patient’s clinical course and treatment

A. Activation state

As mentioned, all CLL clones exhibit features of activated B cells, including those that lack significant numbers of IGHV mutations. However, clones from discrete patients can differ in the types of activation markers expressed as well as the percentage of cells in the clone that express individual markers. For example, the leukemic cells of all CLL patients over-express CD23 and CD253,11–14 and under-express CD22, Fcγreceptor IIb, and CD79b3. However, certain activation markers are more heterogeneous in expression among clonal members than these. For example, CD71 is expressed on more members of CLL clones without IGHV mutations3; conversely, CD38 and CD69 are present on more members of CLL clones without IGHV mutations, and the density of HLA-DR on these cells is also much higher3. The same is true for intracellular expression of ZAP-704,5.

Furthermore, the elevated levels of CD383, ZAP-704,5,78,79, and possibly CD6980 have prognostic relevance in CLL. Therefore, the measurement of the levels of these markers and an understanding of why these particular molecules are over-expressed in the patients with no or few IGHV mutations have relevance for the clinical management of the disease. In addition, these molecules or the activation pathways that they initiate may represent valuable targets and lead to improved therapeutics.

B. Proliferative rate

The studies of Messmer et al.16 suggest that the higher the faster a CLL clone divides the more likely it is that the patient harboring it will have an aggressive clinical course. This finding is consistent with the concept that clonal evolution, which is the basis of most patient’s clinical decompensation, is accelerated in such patients. That clonal evolution occurs and is responsible for clinical progression is supported by findings that certain defined chromosomal abnormalities that exist in CLL are not seen in all members of the clone and often are not detected until the patient has had the disease for many years81,82. Furthermore, these abnormalities occur more frequently when the absolute lymphocyte count increases and clinical deterioration ensues.

Although current therapies for CLL are based on the premise that every cell of a clone is equally dangerous to the patient and therefore effective therapies must eliminate every cell to affect a cure, the available ex vivo phenotypic15 and in vivo labeling17 data suggest that subsets of cells within CLL clones divide more readily than others. It would appear that these cells are the most dangerous members of a leukemic clone because they are the cells that will more likely develop new, permanent DNA abnormalities that could lead to more aggressive clonal variants and clinical deterioration. Therefore, targeting the proliferative compartment might prevent or at least delay significantly the emergence of more dangerous clonal variants by diminishing or eliminating the fraction of the leukemic clone that accumulate new DNA abnormalities during replication. Furthermore, deleting these cells during induction or consolidation therapy might convert CLL into an even more chronic disease and/or lead to an eventual cure.

Finally, if this population could be identified more precisely based on surface marker expression, it might be targeted preferentially, providing a therapeutic approach that might be much less toxic than current chemotherapies or immunochemotherapies that do not target CLL cell-specific targets. Consequently, we suggest that homing in on a series of surface membrane antigens expressed preferentially on proliferating cells with appropriate agents (monoclonal antibodies, peptides, aptamers, etc.) will prevent clonal evolution and disease worsening.

Research agenda

▪ An extended phenotype of the most proliferative cells in a CLL clone might reveal targets or combinations of targets that would permit effective elimination of those cells that proliferate more readily. This could serve as a basis for a novel form of therapy based on selective targeting of such cells.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Rajendra N. Damle, Email: RDamle@NSHS.edu.

Carlo Calissano, Email: Carlo.Calissano@HSR.it.

Nicholas Chiorazzi, Email: NChizzi@NSHS.edu.

References

- 1.Pascual V, Liu YJ, Magalski A, de Bouteiller O, Banchereau J, Capra JD. Analysis of somatic mutation in five B cell subsets of human tonsil. J Exp Med. 1994;180(1):329–339. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nolz JC, Tschumper RC, Pittner BT, Darce JR, Kay NE, Jelinek DF. ZAP-70 is expressed by a subset of normal human B-lymphocytes displaying an activated phenotype. Leukemia. 2005;19(6):1018–1024. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damle RN, Ghiotto F, Valetto A, et al. B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells express a surface membrane phenotype of activated, antigen-experienced B lymphocytes. Blood. 2002;99(11):4087–4093. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.4087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiestner A, Rosenwald A, Barry TS, et al. ZAP-70 expression identifies a chronic lymphocytic leukemia subtype with unmutated immunoglobulin genes, inferior clinical outcome, and distinct gene expression profile. Blood. 2003;101(12):4944–4951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crespo M, Bosch F, Villamor N, et al. ZAP-70 expression as a surrogate for immunoglobulin-variable-region mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(18):1764–1775. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa023143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damle RN, Wasil T, Fais F, et al. Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94(6):1840–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Poeta G, Maurillo L, Venditti A, et al. Clinical significance of CD38 expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2001;98(9):2633–2639. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghia P, Guida G, Stella S, et al. The pattern of CD38 expression defines a distinct subset of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients at risk of disease progression. Blood. 2003;101(4):1262–1269. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deaglio S, Vaisitti T, Billington R, et al. CD38/CD19: a lipid raft-dependent signaling complex in human B cells. Blood. 2007;109(12):5390–5398. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-061812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L, Apgar J, Huynh L, et al. ZAP-70 directly enhances IgM signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2005;105(5):2036–2041. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarfati M. CD23 and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Cells. 1993;19(3):591–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulkkonen J, Vilpo L, Hurme M, Vilpo J. Surface antigen expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clustering analysis, interrelationships and effects of chromosomal abnormalities. Leukemia. 2002;16(2):178–185. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilpo J, Tobin G, Hulkkonen J, et al. Mitogen induced activation, proliferation and surface antigen expression patterns in unmutated and hypermutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Eur J Haematol. 2005;75(1):34–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borst J, Hendriks J, Xiao Y. CD27 and CD70 in T cell and B cell activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17(3):275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damle RN, Temburni S, Calissano C, et al. CD38 expression labels an activated subset within chronic lymphocytic leukemia clones enriched in proliferating B cells. Blood. 2007;110(9):3352–3359. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-083832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Messmer BT, Messmer D, Allen SL, et al. In vivo measurements document the dynamic cellular kinetics of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(3):755–764. doi: 10.1172/JCI23409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calissano C, Damle RN, Hayes G, et al. In vivo intraclonal and interclonal kinetic heterogeneity in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114(23):4832–4842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid C, Isaacson PG. Proliferation centres in B-cell malignant lymphoma, lymphocytic (B-CLL): an immunophenotypic study. Histopathology. 1994;24(5):445–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1994.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soma LA, Craig FE, Swerdlow SH. The proliferation center microenvironment and prognostic markers in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(2):152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granziero L, Ghia P, Circosta P, et al. Survivin is expressed on CD40 stimulation and interfaces proliferation and apoptosis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2001;97(9):2777–2783. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.9.2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schattner EJ, Mascarenhas J, Reyfman I, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells can express CD40 ligand and demonstrate T-cell type costimulatory capacity. Blood. 1998;91(8):2689–2697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranheim EA, Cantwell MJ, Kipps TJ. Expression of CD27 and its ligand, CD70, on chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood. 1995;85(12):3556–3565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trentin L, Zambello R, Sancetta R, et al. B lymphocytes from patients with chronic lymphoproliferative disorders are equipped with different costimulatory molecules. Cancer Res. 1997;57(21):4940–4947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patten PE, Buggins AG, Richards J, et al. CD38 expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia is regulated by the tumor microenvironment. Blood. 2008;111(10):5173–5181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serrano D, Monteiro J, Allen SL, et al. Clonal expansion within the CD4+CD57+ and CD8+CD57+ T cell subsets in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Immunol. 1997;158(3):1482–1489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halper JP, Fu SM, Gottlieb AB, Winchester RJ, Kunkel HG. Poor mixed lymphocyte reaction stimulatory capacity of leukemic B cells of chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients despite the presence of Ia antigens. J Clin Invest. 1979;64(5):1141–1148. doi: 10.1172/JCI109567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiorazzi N, Fu S, Montazeri G, Kunkel H, Rai K, Gee T. T cell helper defect in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Immunol. 1979;122:1087–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scrivener S, Goddard RV, Kaminski ER, Prentice AG. Abnormal T-cell function in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44(3):383–389. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000029993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jak M, Mous R, Remmerswaal EBM, et al. Enhanced formation and survival of CD4<sup>+</sup> CD25<sup>hi</sup> Foxp3<sup>+</sup> T-cells in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2009;50(5):788–801. doi: 10.1080/10428190902803677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramsay AG, Johnson AJ, Lee AM, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia T cells show impaired immunological synapse formation that can be reversed with an immunomodulating drug. J Clin Invest. 2008 doi: 10.1172/JCI35017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muzio M, Apollonio B, Scielzo C, et al. Constitutive activation of distinct BCR-signaling pathways in a subset of CLL patients: a molecular signature of anergy. Blood. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-111344. 2008blood-2007-2009-111344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ringshausen I, Schneller F, Bogner C, et al. Constitutively activated phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI-3K) is involved in the defect of apoptosis in B-CLL: association with protein kinase Cdelta. Blood. 2002;100(10):3741–3748. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frank DA, Mahajan S, Ritz J. B lymphocytes from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia contain signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 1 and STAT3 constitutively phosphorylated on serine residues. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(12):3140–3148. doi: 10.1172/JCI119869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolowiec D, Ciszak L, Kosmaczewska A, et al. Cell cycle regulatory proteins and apoptosis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2001;86(12):1296–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schrader C, Janssen D, Klapper W, et al. Minichromosome maintenance protein 6, a proliferation marker superior to Ki-67 and independent predictor of survival in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2005;93(8):939–945. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Endl E, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: fascinating forms and an unknown function. Exp Cell Res. 2000;257(2):231–237. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown DC, Gatter KC. Ki67 protein: the immaculate deception? Histopathology. 2002;40(1):2–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weng NP, Granger L, Hodes RJ. Telomere lengthening and telomerase activation during human B cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(20):10827–10832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trentin L, Ballon G, Ometto L, et al. Telomerase activity in chronic lymphoproliferative disorders of B-cell lineage. Br J Haematol. 1999;106(3):662–668. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Damle RN, Batliwalla FM, Ghiotto F, et al. Telomere length and telomerase activity delineate distinctive replicative features of the B-CLL subgroups defined by immunoglobulin V gene mutations. Blood. 2004;103(2):375–382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lanham S, Hamblin T, Oscier D, Ibbotson R, Stevenson F, Packham G. Differential signaling via surface IgM is associated with VH gene mutational status and CD38 expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2003;101(3):1087–1093. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cutrona G, Colombo M, Matis S, et al. Clonal heterogeneity in CLL cells: response to surface IgM crosslinking is more efficient in CD38, ZAP-70 positive cells. Haematologica. 2007 doi: 10.3324/haematol.11646. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Efremov DG, Gobessi S, Longo PG. Signaling pathways activated by antigen-receptor engagement in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B-cells. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;7(2):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyko F, Stach D, Brenner A, et al. Quantitative analysis of DNA methylation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Electrophoresis. 2004;25(10–11):1530–1535. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu MK, Bergonia H, Szabo A, Phillips JD. Progressive disease in chronic lymphocytic leukemia is correlated with the DNA methylation index. Leukemia Research. 2007;31(6):773. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanduri M, Cahill N, Goransson H, et al. Differential genome-wide array-based methylation profiles in prognostic subsets of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 115(2):296–305. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klein U, Goossens T, Fischer M, et al. Somatic hypermutation in normal and transformed human B cells. Immunol Rev. 1998;162:261–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schroeder HW, Jr, Dighiero G. The pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: analysis of the antibody repertoire. Immunol Today. 1994;15(6):288–294. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fais F, Ghiotto F, Hashimoto S, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells express restricted sets of mutated and unmutated antigen receptors. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(8):1515–1525. doi: 10.1172/JCI3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamblin TJ, Davis Z, Gardiner A, Oscier DG, Stevenson FK. Unmutated Ig VH genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94(6):1848–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krober A, Seiler T, Benner A, et al. V(H) mutation status, CD38 expression level, genomic aberrations, and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100(4):1410–1416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenwald A, Alizadeh AA, Widhopf G, et al. Relation of gene expression phenotype to immunoglobulin mutation genotype in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Exp Med. 2001;194(11):1639–1647. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.11.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klein U, Tu Y, Stolovitzky GA, et al. Gene expression profiling of B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia reveals a homogeneous phenotype related to memory B cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194(11):1625–1638. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.11.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ekholm SV, Reed SI. Regulation of G(1) cyclin-dependent kinases in the mammalian cell cycle. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12(6):676–684. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolowiec D, Deviller P, Simonin D, et al. Cdk1 is a marker of proliferation in human lymphoid cells. Int J Cancer. 1995;61(3):381–388. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paul JT, Henson ES, Mai S, et al. Cyclin D expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46(9):1275–1285. doi: 10.1080/10428190500158797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chiorazzi N, Rai KR, Ferrarini M. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(8):804–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chiorazzi N, Ferrarini M. B Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Lessons learned from studies of the B cell antigen receptor. Ann Rev Immunol. 2003;21:841–894. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ranheim EA, Kipps TJ. Activated T cells induce expression of B7/BB1 on normal or leukemic B cells through a CD40-dependent signal. J Exp Med. 1993;177(4):925–935. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Longo PG, Laurenti L, Gobessi S, et al. The Akt signaling pathway determines the different proliferative capacity of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B-cells from patients with progressive and stable disease. Leukemia. 2007;21(1):110–120. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Neese RA, Siler SQ, Cesar D, et al. Advances in the stable isotope-mass spectrometric measurement of DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. Anal Biochem. 2001;298(2):189–195. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hellerstein MK, Neese RA. Mass isotopomer distribution analysis: a technique for measuring biosynthesis and turnover of polymers. Am J Physiol. 1992;263(5 Pt 1):E988–1001. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.263.5.E988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rubini JR, Bond VP, Keller S, Fliedner TM, Cronkite EP. DNA synthesis in circulating blood leukocytes labeled in vitro with H3-thymidine. J Lab Clin Med. 1961;58:751–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zimmerman TS, Godwin HA, Perry S. Studies of leukocyte kinetics in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1968;31(3):277–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Theml H, Trepel G, Schick P, et al. Kinetics of lymphocytes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: studies using continuous 3H-thymidine infusion in two patients. Blood. 1973:42623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dormer P, Theml H, Lau B. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a proliferative or accumulative disorder? Leuk Res. 1983;7(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(83)90052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Defoiche J, Debacq C, Asquith B, et al. Reduction of B cell turnover in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Gent R, Kater AP, Otto SA, et al. In vivo dynamics of stable chronic lymphocytic leukemia inversely correlate with somatic hypermutation levels and suggest no major leukemic turnover in bone marrow. Cancer Res. 2008;68(24):10137–10144. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simonsson B, Nilsson K. 3H-thymidine uptake in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells. Scand J Haematol. 1980;24(2):169–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1980.tb02363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Montserrat E, Sanchez-Bisono J, Vinolas N, Rozman C. Lymphocyte doubling time in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: analysis of its prognostic significance. Br J Haematol. 1986;62(3):567–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1986.tb02969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Molica S, Alberti A. Prognostic value of the lymphocyte doubling time in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 1987;60(11):2712–2716. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19871201)60:11<2712::aid-cncr2820601122>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Winkelstein A, Craddock CG. Comparative response of normal human thymus and lymph node cells to phytohemagglutinin in culture. Blood. 1967;29(4 Suppl):594–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smit LA, Hallaert DY, Spijker R, et al. Differential Noxa/Mcl-1 balance in peripheral versus lymph node chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells correlates with survival capacity. Blood. 2007;109(4):1660–1668. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Caligaris-Cappio F. Role of the microenvironment in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2003;123(3):380–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chilosi M, Pizzolo G, Caligaris-Cappio F, et al. Immunohistochemical demonstration of follicular dendritic cells in bone marrow involvement of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 1985;56(2):328–332. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850715)56:2<328::aid-cncr2820560221>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Renno T, Attinger A, Locatelli S, Bakker T, Vacheron S, MacDonald HR. Cutting edge: apoptosis of superantigen-activated T cells occurs preferentially after a discrete number of cell divisions in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;162(11):6312–6315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mongini PKA, Inman JK, Han H, Kalled SL, Fattah RJ, McCormick S. Innate immunity and human B cell clonal expansion: effects on the recirculating B2 subpopulation. J Immunol. 2005;175(9):6143–6154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rassenti LZ, Jain S, Keating MJ, et al. Relative value of ZAP-70, CD38, and immunoglobulin mutation status in predicting aggressive disease in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;112(5):1923–1930. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rassenti LZ, Hunynh L, Toy TL, et al. ZAP-70 compared with immunoglobulin heavy-chain genemutation status as a predictor of disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(9):893–901. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.D’Arena G, Musto P, Nunziata G, Cascavilla N, Savino L, Pistolese G. CD69 expression in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a new prognostic marker ? Haematologica. 2001;86(9):995–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shanafelt TD, Witzig TE, Fink SR, et al. Prospective evaluation of clonal evolution during long-term follow-up of patients with untreated early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(28):4634–4641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shanafelt TD, Jelinek D, Tschumper R, et al. Cytogenetic abnormalities can change during the course of the disease process in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(19):3218–3219. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1077. author reply 3219–3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]