Abstract

The Aβ42 peptide rapidly aggregates to form oligomers, protofibils and fibrils en route to the deposition of amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer's disease. We show that low temperature and low salt can stabilize disc-shaped oligomers (pentamers) that are significantly more toxic to murine cortical neurons than protofibrils and fibrils. We find that these neurotoxic oligomers do not have the β-sheet structure characteristic of fibrils. Rather, the oligomers are composed of loosely aggregated strands whose C-terminus is protected from solvent exchange and which have a turn conformation placing Phe19 in contact with Leu34. On the basis of NMR spectroscopy, we show that the structural conversion of Aβ42 oligomers to fibrils involves the association of these loosely aggregated strands into β-sheets whose individual β-strands polymerize in a parallel, in-register orientation and are staggered at an inter-monomer contact between Gln15 and Gly37.

A major pathological hallmark of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the formation of neuritic plaques within the gray matter of AD patients 1. These plaques are composed primarily of filamentous aggregates (fibrils) of the 39–42 amino acid long amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide formed from the proteolytic cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein by β- and γ-secretases 2–5. The major species of Aβ production are the Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides, with Aβ42 being predominant in neuritic plaques of AD patients and exhibiting a higher in vitro propensity to aggregate and form amyloid fibrils 4,6–8. Familial AD mutations result in an increase in the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio in cell culture and mouse models 9,10, and elevated plasma levels of Aβ42 appear to be correlated with AD 11. Given the pathological significance of the Aβ42 peptide, determining the molecular structure of its fibrils and pre-fibrillar oligomers is crucial for elucidating the aggregation pathway involved in plaque formation and for the development of therapeutic and diagnostic agents.

Much is known about the molecular structure of Aβ fibrils. As with other amyloid fibrils, Aβ fibrils have a cross-β structure where the individual β-strands are oriented perpendicular to the fibril axis 12 (see Supplementary Results 1). In Aβ42, the N-terminus is thought to be unstructured 13,14 and there are two largely hydrophobic β-strand segments within the fibrils that have a parallel and in-register orientation 15–17. Figure 1 presents a schematic of the Aβ42 sequence and summarizes current models for how the two β-strand regions may fold into a β-strand-turn-β-strand (β-turn-β) conformation. A specific packing arrangement of the β-strands has been proposed on the basis of mutational studies in which Phe19 on the N-terminal β-strand packs against Gly38 on the C-terminal β-strand 14. NMR studies have suggested that the C-terminal β-strand bends at Gly37/38 to allow Ala42 to contact the side-chain of Met35 18. The C-terminal amino acids are largely protected from solvent exchange 13,14, although EPR measurements indicate that the last 2–3 amino acids may be disordered 17.

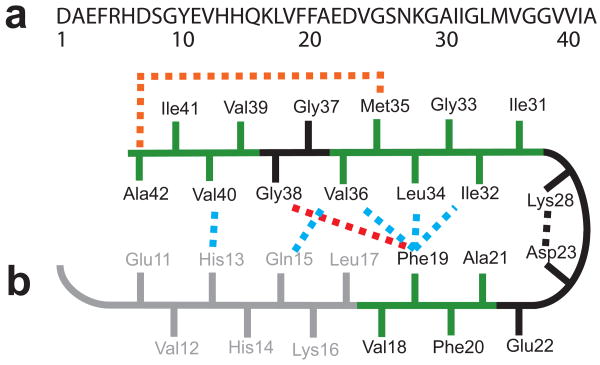

Figure 1.

Sequence and structure of the monomer unit in Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils. (a) Sequence of Aβ42 that is derived from human APP. (b) Structural constraints in Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils. NMR measurements of Aβ40 fibrils have shown that residues 1–10 are unstructured and residues 11–40 adopt a β-turn-β fold 19,20. Side-chain packing is observed between Phe19 and Ile32/Leu34/Val36, between Gln15 and Val36, and between His13 and Val40 (blue dashed lines). In Aβ42 fibrils, residues 1–17 may be unstructured (in gray) with residues 18–42 forming a β-turn-β fold 14. Molecular contacts have been reported within the monomer unit of Aβ42 fibrils between Phe19 and Gly38 (red dashed line) 14 and between Met35 and Ala42 (orange dashed line) 18. In both Aβ40 and Aβ42, the turn conformation is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions (green residues) and by a salt bridge between Asp23 and Lys28 (black dashed line).

Models of Aβ42 fibrils can be compared with those of Aβ40 developed by Tycko and coworkers on the basis of solid-state NMR and scanning-tunneling EM measurements 19. In Aβ40 fibrils, residues 1–10 are found to be unstructured, and residues 11–40 form a staggered β-turn-β unit stabilized by a salt-bridge between Asp23 and Lys28 19, but with a different set of intra-strand contacts than proposed for Aβ42 14 (see Fig. 1b). In the Aβ40 model, Phe19 is in contact with Leu34, Gln15 is in contact with Val36, and His13 is in contact with Val40 19,20. The cross-section of Aβ40 fibrils has recently been shown to consist of either two or three β-turn-β units depending on the morphology of the fibril 20. Fibrils with a striated ribbon morphology have two-fold symmetry with inter-molecular contacts between Met35 and Gly33 and between Ile31 and Gly37. In contrast, fibrils with a twisted morphology have three-fold symmetry with inter-molecular contacts between Ile31 and Val39. In both fibril structures, the β-turn-β units pack in a parallel and in-register fashion with roughly the same conformation.

Considerably less is known about the molecular structure of Aβ oligomers, which have been shown to cause neuronal dysfunction 21–23, disrupt long-term potentiation 24, and impair memory in mouse models of AD 25. A growing body of literature has implicated the pre-fibrillar oligomers, and not the fibrillar form, as the primary pathological species of AD 26,27. Of particular pathological significance is the Aβ42 peptide. Low-level expression of Aβ42, versus overexpression of Aβ40, has been shown to correlate with extensive amyloid pathology in transgenic mouse models 28. Aβ42, unlike Aβ40, can form stable trimeric/tetrameric complexes 29 and globulomer structures (dodecamers) 30 in the presence of sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS), and pentamers and hexamers in solution 31,32. Our own investigation of Aβ42 oligomers using single-touch atomic force microscopy (AFM) has shown that within hours of incubation at 25 °C, Aβ42 monomers form a wide range of soluble oligomeric species (diameters of 5–25 nm) and protofibrils (lengths of over 40 nm) 33.

The inability to isolate homogeneous Aβ42 oligomers has presented a challenge for high-resolution structural approaches. Recently, Yu et al. 34 reported solution NMR measurements of Aβ42 globulomers solubilized with SDS. They found that globulomers are composed of dimer units having both intermolecular and intramolecular β-sheet contacts. The drawback of these studies, however, is that the use of detergent is thought to produce an off-pathway conformation that does not lead to fibril formation 35. In the case of the Aβ40, Ishii and co-workers 36 were able to isolate relatively homogeneous Aβ40 oligomers by filtration. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that spherical aggregates with diameters ranging from 15–35 nm could be stabilized under low salt conditions at 4 °C for up to 55 h. Unlike the Aβ42 oligomers in SDS, these spherical aggregates are shown to be intermediates in Aβ40 fibrillization since they slowly convert to protofibrils and fibrils and contain fibril-like β-sheet structure.

Here, we take advantage of low temperature and low salt conditions to stabilize homogeneous oligomers of pure Aβ42 obtained by chemical synthesis. These oligomers have not undergone a conversion to β-sheet structure, although the hydrophobic stretches within the peptide sequence (Fig. 1, green) pack together in a strand-turn-strand conformation and are not solvent accessible. When the temperature is increased, these stable Aβ42 oligomers readily form protofibrils and fibrils, and we show that this conversion is associated with a reduction in neurotoxicity. Using a combination of TEM, single-touch AFM, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and NMR spectroscopy, we are able to define key molecular contacts in both the oligomeric and fibrillar conformations of Aβ42 and consequently characterize the structural changes involved in aggregation and toxicity.

Results

Aβ42 oligomers are disc-shaped pentamers and decamers

TEM and AFM are complementary methods for imaging Aβ42 oligomers. TEM images of Aβ42 oligomers prepared at low temperature and under low salt conditions reveal a nearly homogeneous distribution of round particles with average widths of ∼10–15 nm (Fig. 2a). Single-touch AFM confirm that the oligomers have widths of 10–15 nm under hydrated conditions, but show they are disc-shaped with heights of ∼2–4 nm (Supplementary Results 2). The height measurements by AFM are accurate to ± 0.1 nm 33 and reveal that there are at least two populations of oligomers. The predominant population of oligomers has heights of ∼1.5–2.5 nm, while a smaller population has heights of 3–4 nm. Our previous AFM studies of Aβ42 at 25 °C and physiological salt concentration revealed that the oligomers with heights of 3–4 nm can be reduced to heights of 2–3 nm in the presence of designed inhibitors that bind to the hydrophobic C-terminus of Aβ42 and inhibit neurotoxicity 33. Importantly, when the height was reduced by inhibitor binding, the oligomer width did not change, suggesting that the ∼4 nm high particles are dimers of disc-shaped, ∼2 nm high oligomers.

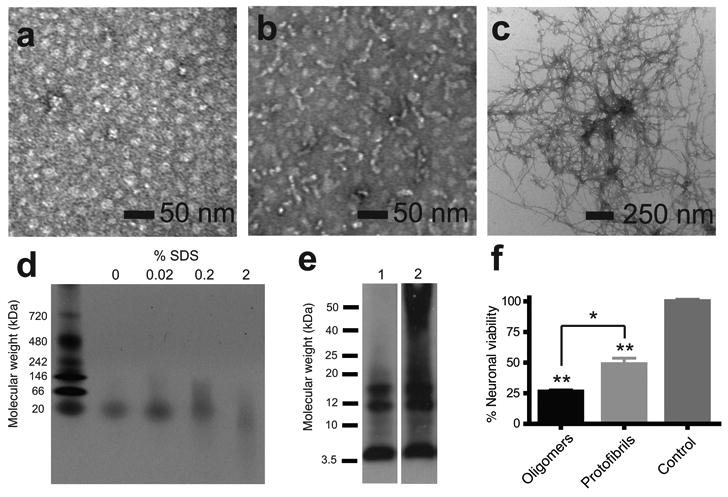

Figure 2.

Characterization of Aβ42 oligomers, protofibrils and fibrils. (a) TEM of Aβ42 oligomers incubated at 4 °C for 6 h. (b) TEM of Aβ42 protofibrils incubated at 37 °C for 6 h; (c) TEM of Aβ42 fibrils incubated at 37 °C for 12 days. (d) Native gel electrophoresis showing that oligomers contain a single band at ∼20 kDa and that increasing the SDS content can disrupt the oligomeric conformation. (e) Sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of Aβ42 oligomers incubated at 4 °C for 6 h (lane 1) and protofibrils incubated at 37 °C for 6 h (lane 2). Aβ42 was detected using the monoclonal 6E10 anti-Aβ antibody. (f) Cell viability assay of primary cultures of murine cortical neurons treated with Aβ42 oligomers incubated at 4 °C for 6 h or protofibrils incubated at 37 °C for 6 h (n=5). Results represent the mean ± sem, * p < 0.02, ** p <0.001.

The stable oligomers formed at low temperature are on a productive pathway for the formation of amyloid fibrils. Narrow, elongated protofibrils are formed when these Aβ42 oligomers are incubated for 6 h at 37 °C (Fig. 2b). Dense networks of mature fibrils are formed from the protofibrils after 12 days of incubation at 37 °C (Fig. 2c).

The stability of the Aβ42 oligomers was tested by thioflavin T binding (Supplementary Results 2). Aβ42 oligomers at low temperature and low salt exhibit negligible binding to thioflavin T with no evidence by AFM of protofibril formation or further aggregation over extended periods of time (up to 100 h). When the temperature is increased to 37 °C, newly formed protofibrils and fibrils exhibit appreciable thioflavin T binding.

The composition of the Aβ42 oligomers was characterized by size exclusion chromatography (SEC), as well as by native and SDS gel electrophoresis. SEC revealed that oligomer samples contain a single size distribution of 24 ± 3 kDa (Supplementary Results 3), which is closer to the molecular weight of a pentamer (22.5 kDa) than to a hexamer (27.0 kDa). On native gels, a single band is observed with a molecular weight of ∼20 kDa (Fig. 2d). These results indicate that the 2-nm high oligomers are predominantly pentamers. Photochemical crosslinking and mass spectrometry have previously found stable pentamers and hexamers in solution 31,32. On SDS gels (Fig. 2e), we show that the oligomers (lane 1) can be broken down into monomers (4.5 kDa), trimers (13.5 kDa) and tetramers (18.0 kDa). The protofibril sample (lane 2) displayed an additional smear of aggregates with molecular weights of >25 kDa. Incubation of the oligomeric samples with SDS prior to electrophoresis on native gels confirmed that SDS can disrupt oligomers into smaller apparent sizes.

Volumetric analysis (Supplementary Results 1 and 2), in combination with the results from SEC, indicates that the oligomers observed by single-touch AFM with heights of ∼2 nm are composed of pentamers, and possibly hexamers. We propose that the oligomers with heights of 3–4 nm correspond to dimers of the 2 nm high particles. The absence of decamers (or dodecamers) in the SEC and native gel measurements argues that the 2 nm high particles only weakly dimerize under low temperature and low salt conditions.

Aβ42 oligomers are more toxic than protofibrils or fibrils

One of the challenges in determining the toxic state of Aβ42 is that one typically has a heterogeneous mixture of oligomers and protofibrils 33. The ability to stabilize Aβ42 as predominantly pentamers allows us to compare their toxicity with that of higher-order oligomers and fibrils.

The toxicity of the Aβ42 oligomers, protofibrils and fibrils was measured using primary cultures of murine cortical neurons. The stable oligomers were found to be significantly more toxic than protofibrils (Fig. 2f). The striking aspect of this result is that the oligomers are added to neuronal cell cultures at 25 °C and allowed to incubate for 48 h before testing cell viability. This observation implies that the oligomers rapidly interact with neuronal cell membranes. The toxicity of the Aβ42 peptide was further reduced as mature fibrils formed (see Supplementary Results 4). Taken together, these observations suggest there are structural features of the oligomers that confer toxicity which are not found in the protofibrils and fibrils. In the sections below, we characterize the structural differences between the low temperature/low salt oligomers and mature fibrils of Aβ42.

Secondary structure of Aβ42 oligomers and fibrils

The secondary structure of the Aβ42 oligomer and fibril samples can be determined and compared using FTIR spectroscopy. The amide I vibrational frequency, which is sensitive to backbone conformation, is observed at 1645 cm-1 in FTIR spectra of the stable oligomers prepared under low temperature and low salt conditions (Supplementary Results 5). The position of the amide I vibration is consistent with disordered secondary structure or with aggregated strands having a less defined preference for the ϕ and ψ torsion angles characteristic of β-sheet secondary structure. When the sample is warmed to 37 °C, the amide I band immediately narrows and shifts to 1630 cm-1, a frequency characteristic of β-sheet structure. Measurements on samples incubated for less than 1 h at 37 °C are nearly identical to those of mature fibrils, indicating that the conversion to protofibrils rapidly induces a conversion to β-sheet 33.

The lack of defined β-sheet secondary structure in Aβ42 oligomers implies that the amide backbone is more accessible to solvent exchange than in protofibrils or fibrils. Solution NMR measurements of hydrogen-deuterium exchange of the amide NH protons were undertaken to investigate solvent accessibility. Amide exchange rates have previously been reported for Aβ42 fibrils showing the N-terminus is relatively accessible up to Leu17, but that the C-terminus is protected from exchange 13,14. The amide hydrogen-deuterium exchange rates for Aβ42 oligomers and fibrils are distinctly different (Supplementary Results 6). For the oligomers, the observed amide exchange rates suggest a solvent accessible N-terminus up to Gly9 and solvent accessible turns at His13-Gln15, Gly25-Gly29, and Gly37-Gly38.

The structure and composition of the Aβ42 oligomers are markedly different from the neurotoxic oligomers of Aβ40 characterized by Chimon et al. 36 despite the very similar conditions used (5–10 mM NaCl and 4 °C). According to their measurements, oligomers of Aβ40 are spherical aggregates of 200–400 monomers with diameters of 15–35 nm. Their NMR analysis showed that these large oligomers contain parallel β-sheets. In contrast to Aβ42, the Aβ40 oligomers slowly form protofibrils and fibrils after ∼55 h. The difference in structure and the higher propensity of the Aβ40 oligomers to convert to protofibrils and fibrils at low temperature may reflect the lower toxicity levels generally exhibited by Aβ40 relative to Aβ42.

Parallel, in-register β-sheets in fibrils but not oligomers

The previous observation by Chimon et al. 36 that both the Aβ40 oligomers and fibrils have parallel and in-register β-sheet structures highlights an important difference with Aβ42. In the previous study, solid-state NMR measurements revealed close inter-peptide contacts in both the Aβ40 oligomers and fibrils, whereas the FTIR results above suggest that the fibrils of Aβ42, but not the oligomers, form β-sheet secondary structure.

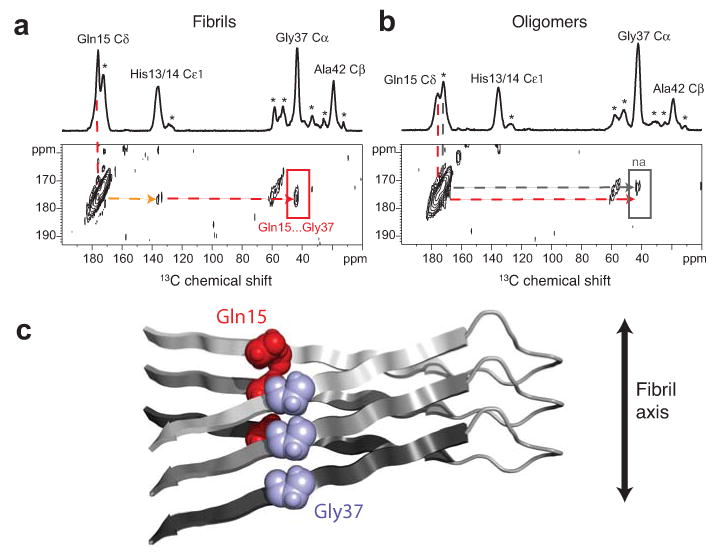

We undertook solid-state magic angle spinning NMR measurements similar to those of Chimon et al. 36 to test whether the Aβ42 peptides in the oligomer and fibril conformations are composed of β-strands that have polymerized in a parallel and in-register orientation. Inter-strand 13C…13C dipolar couplings were measured at Ala21 on the N-terminal strand and Gly33 and Gly37 on the C-terminal strand of Aβ42.

Figure 3 presents two-dimensional dipolar assisted rotational resonance (DARR) NMR measurements of inter-strand 13C dipolar couplings between Ala21 and Gly37. Fibril and oligomer samples were prepared by mixing the Aβ42-AG1 and Aβ42-AG2 peptides (see Table 1) in equimolar amounts. If the β-strands in Aβ42 fibrils have a parallel, in-register orientation as shown in Figure 3a, we expect to observe off-diagonal cross-peaks between the Ala21 13CO and Ala21 13Cα resonances and between the Gly37 13CO and Gly37 13Cα resonances on adjacent peptides.

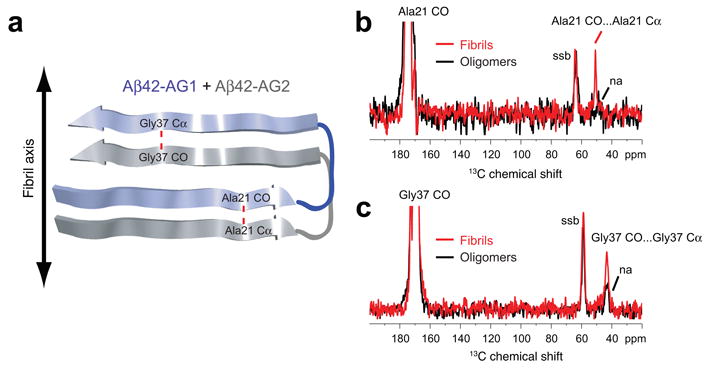

Figure 3.

Parallel and in-register orientation of β-strands in Aβ42 fibrils. (a) Labeling scheme to test for parallel and in-register orientations of the N- and C-terminal β-strands in Aβ42 fibrils and oligomers using an equimolar mixture of Aβ42-AG1 and Aβ42-AG2 peptides. The red dashed line corresponds to the 4.7 Å distance expected between adjacent Ala21 residues and adjacent Gly37 residues along the fibril axis. (b) Rows through the Ala21 13CO diagonal resonance in DARR NMR spectra of Aβ42 fibrils (red trace) and oligomers (black trace). A distinct Ala21 13CO… Ala21 13Cα cross-peak is observed in the fibril conformation, but not the oligomer conformation. (c) Rows through the Gly37 13CO diagonal resonance in DARR NMR spectra of Aβ42 fibrils (red trace) and oligomers (black trace). A distinct Gly37 13CO… Gly37 13Cα cross-peak is observed in the fibril conformation, but not in the oligomer conformation. Smaller natural abundance (na) cross-peaks are observed in the oligomer samples. Spinning side bands (ssb) due to magic angle spinning are indicated. The data indicate that Aβ42 fibrils have β-strands in a parallel and in-register orientation, but oligomers do not.

Table 1.

Isotope-labeled Aβ42 peptides.

| Aβ42-HQA | 13Cε1-His13, 13Cε1-His14, 13Cδ-Gln15, 13Cβ-Ala42 |

| Aβ42-FLG | ring-13C6-Phe19, U-13C6,15N-Leu34, 13Cα-Gly38 |

| Aβ42-M35 | 13Cε-Met35 |

| Aβ42-G33 | 13Cα-Gly33 |

| Aβ42-G37 | 13Cα-Gly37 |

| Aβ42-GMG | 13CO-Gly33, 13Cε-Met35, 13Cα-Gly37 |

| Aβ42-I31 | U-13C6,15N-Ile31 |

| Aβ42-V39 | U-13C5,15N-Val39 |

| Aβ42-AG1 | 13CO-Ala21, 13Cα-Gly37 |

| Aβ42-AG2 | 13Cα-Ala21, 13CO-Gly37 |

Figure 3b presents rows from the NMR spectra through the 13CO diagonal resonance of Ala21 in fibrils (red trace) and in oligomers (black trace). A distinct cross-peak is observed between the Ala21-13CO and Ala21-13Cα resonances in the fibril sample. In contrast, in the oligomer sample, only a small natural abundance cross-peak is observed. Natural abundance cross-peaks arise between labeled 13CO sites and their own directly bonded Cα carbons that are 13C-labeled at natural abundance levels (1.1%). The expected natural abundance cross-peak provides an internal control for calibrating the strength of the dipolar coupling between fully 13C labeled sites.

Figure 3c presents rows from the DARR NMR spectra through the 13CO diagonal resonance of Gly37 in fibrils (red trace) and in oligomers (black trace). As with Ala21, distinct cross-peaks are observed between the Gly37-13CO and Gly37-13Cα resonances in the fibril sample, whereas only small natural abundance cross-peaks are observed in the oligomer sample. A similar result was obtained when we tested for a parallel and in-register orientation at Gly33 in Aβ42 fibrils and oligomers (Supplementary Results 7).

Together these results show that fibrils have N- and C-terminal β-strands with parallel and in-register orientations. The large cross-peaks observed for fibrils at Ala21, Gly33 and Gly37 correspond to inter-strand distances of less than 6 Å, the distance range for the DARR NMR experiment. In contrast, the neurotoxic oligomers do not exhibit close contacts at these three positions, indicating they do not form parallel and in-register β-sheets.

Phe19-Leu34 packing in Aβ42 oligomers and fibrils

The data described above show that the stable Aβ42 oligomers have a different overall conformation and are less ordered than either Aβ40 oligomers or Aβ42 fibrils. Nevertheless, our previous AFM images and solution NMR results (Supplementary Results 6) argue the Aβ42 oligomers are compact and that portions of the hydrophobic C-terminus are largely solvent inaccessible. These observations suggest that the hydrophobic C-terminus in the Aβ42 oligomer may form a U-shaped hairpin structure as it does in Aβ42 fibrils.

To address how the hydrophobic C-terminus packs in Aβ42 oligomers and fibrils, we measured specific intra-peptide distances. We targeted the hydrophobic contacts of Phe19, which is predicted by Lührs et al. 14 to pack against Gly38 in Aβ42 fibrils 14. A Phe19-Gly38 interaction contrasts with the Phe19-Leu34 interaction observed in Aβ40 fibrils 19. DARR NMR experiments were designed to measure 13C…13C dipolar couplings within a single Aβ42 peptide containing ring-13C6-Phe19, U-13C6-Leu34, and 13Cα-Gly38.

In Aβ42 fibrils (Fig. 4a), intense cross-peaks (red boxes) are observed between the major Phe19 resonance (Cδ1, Cδ2, Cε1, Cε2, Cζ) and the Leu34 resonance (Cγ, Cδ1, and Cδ2). In contrast, no cross-peaks are observed between the Phe19 and Gly38 resonances (blue boxes). These data indicate that the side-chain packing of Aβ42 fibrils within the β-turn-β motif closely resembles that in Aβ40 fibrils where Phe19 packs against Leu34 (Fig. 1). The data are not consistent with the previously proposed Aβ42 model 14.

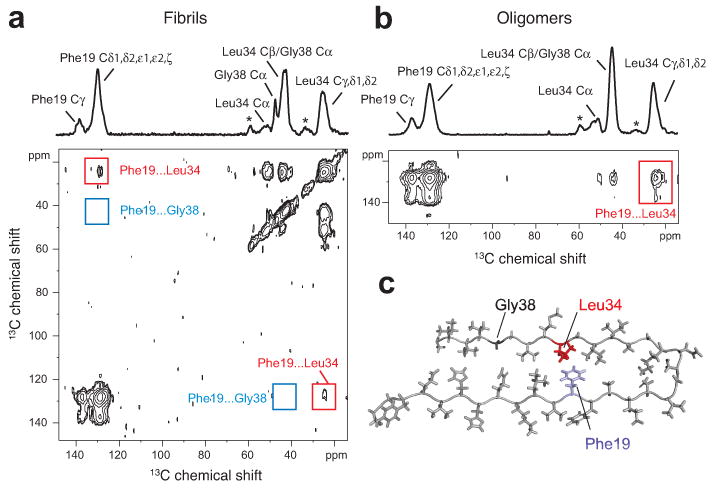

Figure 4.

Turn structure in Aβ42 fibrils and neurotoxic oligomers. (a) Above, one-dimensional 13C-NMR spectrum showing chemical shift assignments for Phe19, Leu34 and Gly38 in Aβ42 fibrils formed from Aβ42-FLG peptides. Natural abundance (na) cross-peaks are marked with an asterisk. Below, region of the two-dimensional DARR NMR spectrum showing specific 13C…13C molecular contacts between Phe19 and Leu34 (red box) and no contact between Phe19 and Gly38 (blue box) in Aβ42 fibrils. (b) Above, one dimensional 13C-spectrum showing chemical shift assignments for Phe19, Leu34, and Gly38 in Aβ42 oligomers formed from Aβ42-FLG peptides. Below, two-dimensional DARR NMR spectrum showing a specific 13C…13C contact between Phe19 and Leu34 in Aβ42 oligomers. Due to the chemical shift overlap between the Cα of Gly38 and the Cβ of Leu34 in the oligomers, we cannot rule out Phe19-Gly38 contacts in a minor population of Aβ42 peptides. (c) Molecular model of the turn conformation in Aβ42 highlighting the Phe19-Leu34 contact (see also Supplementary Results 1).

In parallel experiments on the Aβ42 oligomers (Fig. 4b), intense cross-peaks are observed between the major Phe19 resonance and the side-chain resonances of Leu34. The contacts between Phe19 and Leu34 indicate that Aβ42 fibrils and oligomers have a similar turn conformation in this region of the peptide (Fig. 4c). The intensity of the cross-peaks argues that the oligomers are homogeneous with respect to this specific structural feature, and that there is not a dynamic equilibrium between extended and folded structures. Dilution experiments of the Aβ42-FLG peptide used for these experiments with unlabeled Aβ42 show that the cross-peaks arise from intra-molecular contacts (data not shown).

The observation of a Phe19-Leu34 contact in both Aβ42 oligomers and fibrils is consistent with the hydrophobic collapse of residues within two of the most hydrophobic stretches of the Aβ peptide (Leu17-Ala21 and Ile31-Val36). The turn structure may be nucleated and stabilized by a favorable electrostatic interaction between Asp23 and Lys28 37, 38.

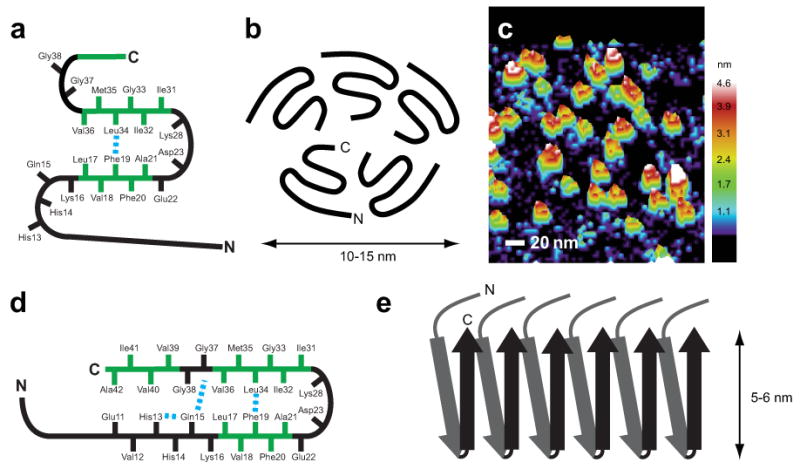

β-strand staggering occurs in Aβ42 fibrils

The β-strands within the β-turn-β motif have previously been shown by solid-state NMR to have a staggered conformation in Aβ40 fibrils 19. To test for a staggered conformation in Aβ42 fibrils and oligomers, samples were prepared using an equimolar mixture of two different Aβ42 peptides to measure inter-peptide 13C…13C dipolar couplings. For these experiments, one peptide was labeled with 13Cδ-Gln15 (Aβ42-HQA, Table 1) and a second peptide was labeled with 13Cα-Gly37 (Aβ42-G37).

For Aβ42 fibrils, the DARR NMR spectrum (Fig. 5a) exhibits a cross-peak between Gln15 and Gly37, consistent with close packing of the Gln15 side chain and the backbone Cα carbon of Gly37. The observed contact between 13C-labeled sites on adjacent peptides indicates that the β-strands are staggered. In a non-staggered geometry, the predicted distance between the labeled sites is > 6–7 Å, which is outside of the detection limit of the DARR NMR experiment. In parallel experiments on Aβ42 oligomers (Fig. 5b), no cross-peaks were observed between Gln15 and Gly37, consistent with their lack of β-sheet secondary structure.

Figure 5.

β-strands are staggered in Aβ42 fibrils. (a) Above, one dimensional 13C-spectrum showing chemical shift assignments for His13/14, Gln15, Gly37 and Ala42 in Aβ42 fibrils formed from an equimolar mixture of Aβ42-HQA:Aβ42-G37 peptides. Natural abundance 13C assignments are marked with an asterisk. Below, region of the two dimensional DARR NMR spectrum showing specific 13C…13C inter-molecular contacts between Gln15 and Gly37 (red arrow), intra-molecular contacts between Gln15 and His13/14 (orange arrow), and no contact between Gln15 and Ala42, indicating a staggered, domain-swapped architecture. (b) Model of staggering between the N- and C-terminal β-strands at the Gln15-Gly37 contact in Aβ42 fibrils. (c) Above, one dimensional 13C-spectrum showing chemical shift assignments for His13/14, Gln15, Gly37 and Ala42 in Aβ42 oligomers formed from an equimolar mixture of Aβ42-HQA:Aβ42-G37 peptides. Below, two dimensional DARR NMR spectrum showing no molecular contacts between Gln15 and His13/14, Gly37, or Ala42 (red arrow), indicating the absence of a staggered, domain swapped architecture in Aβ42 oligomers. Only a small natural abundance (na) cross-peak is observed (gray arrow).

Conversion of aggregated strands into β-sheets

The measurement of specific intra- and inter-peptide contacts by solid-state NMR spectroscopy provides constraints on the structural transition that occurs between Aβ42 oligomers and fibrils. There are least two steps that must occur in this transition. The first step involves inter-strand hydrogen bonding of the hydrophobic segments between Leu17–Ala21 and Ile31–Val36 in a parallel and in-register orientation. This step represents the nucleation of β-sheet secondary structure 39,40. The second step involves staggering of the individual β-strands within the β-sheet. Side-chain packing of the staggered β-strands likely occurs early in the nucleation process and leaves an exposed stretch of hydrophobic residues to which monomeric Aβ42 can add to the growing fibril in a unidirectional fashion 14,41.

The stable oligomers convert to protofibrils and fibrils when the temperature is raised. The temperature-dependent nature of the transition argues that it is entropy driven, suggesting a release of bound water from hydrophobic surfaces during the transition. This release might occur when the pentamers associate to form decamers or dodecamers or when the aggregated strands align to form parallel and in-register β-sheet secondary structure.

Discussion

Structure and composition of the Aβ42 oligomers

Using a combination of single touch AFM, SEC and native gels, we have shown that Aβ42 can form stable disc-shaped pentamers with widths of 10–15 nm and heights of ∼2 nm. Figure 6 presents a molecular model of the Aβ42 pentamer that agrees with the overall dimensions observed by AFM (see Supplementary Results 1 and 2). Each monomer within the pentamer has a diameter of ∼5 nm and a height of 2 nm, consistent with AFM images showing discrete units surrounding a central axis (Fig. 6c). The hydrophobic C-terminus of each monomer is oriented toward the center of the oligomer where it is protected from hydrogen-deuterium exchange. The compact fold of the peptide is facilitated by solvent accessible turns at His13–Gln15, Gly25–Gly29, and Gly37–Gly38, which place Phe19 in contact with Leu34.

Figure 6.

Molecular models of Aβ42 oligomers and fibrils. (a) Schematic of the monomer within the oligomer complex of Aβ42. Solid-state NMR measurements show that Phe19 is in contact with Leu34, while amide exchange measurements suggest there are solvent accessible turns at His13–Gln15, Gly25–Gly29, and Gly37–Gly38. (b) Schematic of the Aβ42 pentamer. The composition of the oligomer is based on SEC and AFM. The orientation of the C-terminus toward the center of the pentamer is based on solvent accessibility. A similar orientation for the hexamer has been proposed by Berstein et al.32. (c) Three-dimensional image of single-touch AFM measurements of Aβ42 oligomers. (d) Schematic of the monomer within Aβ42 fibrils. (e) Schematic showing the parallel and in-register packing and staggering of the individual β-strands within Aβ42 fibrils. A single protofilament is shown. Mature fibrils may be formed by the association of 2–3 protofilaments.

The disc-shaped pentamers may associate to form oligomers with an average height (measured by AFM) of ∼3–4 nm. The formation of decamers (and possibly undecamers and dodecamers) is favored at higher peptide concentrations, higher temperature and physiological salt concentrations 33.

Contrary to Aβ42 globulomers (dodecamers) that are stabilized using lipid or detergents, the oligomers in this study represent an on-pathway intermediate for fibril formation. In the presence of SDS, the pentamers can be broken down into trimers and tetramers. Recent solution NMR studies of Aβ42 in SDS 34 show a different structure from that of the soluble pentamer. Intermolecular hydrogen bonding within the C-terminal β-strand stabilizes Aβ42 dimers. One can speculate that the detergent environment shifts the stabilizing interactions within the strand-turn-strand unit such that the hydrophobic residues in the C-terminus rotate to interact with the hydrophobic dodecyl chains of SDS.

Structure of Aβ42 fibrils

Distance measurements between 13C-sites using solid-state NMR provide constraints on the structure of Aβ42 fibrils. Our data confirm that the C-terminal hydrophobic sequence of Aβ42 folds into a β-turn-β conformation (Fig. 6d), and that Aβ42 fibrils are composed of multiple β-turn-β units that polymerize in a parallel and in-register orientation. DARR NMR measurements specifically show that the side-chain packing registry within the β-turn-β structure involves molecular contacts between Phe19 and Leu34 and between Gln15 and Gly37. Additionally, the Gln15-Gly37 contact is intermolecular in nature and arises from a staggering of the β-strands within the β-turn-β unit (Fig. 6e).

On the basis of pairwise mutational experiments of Asp23 and Lys28, Lührs et al. 14 developed a model of Aβ42 with a similar domain swapping architecture. The side-chain packing registry within the β-turn-β motif of Aβ42 fibrils is similar to that observed in Aβ40 fibrils by Tycko and co-workers 19,20 (Fig. 1). These results indicate that the core β-strand-turn-β-strand unit is similar for fibrils formed from Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides. The data are consistent with previous studies showing that the Aβ40 and Aβ42 homogeneously co-mix in amyloid fibrils, suggesting that Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils have the same structural architecture 17.

Our model differs from the one proposed by Lührs et al. 14 with respect to the specific side-chain packing arrangement within the β-turn-β unit. According to their model, Phe19 packs against Gly38 based on fibril recovery experiments using a pair-wise mutagenesis strategy. They found that the single G38F mutation reduces the fibril-forming capacity of recombinant Aβ42(M35L) peptides, and that the double G38F, F19G mutation recovers fibril-forming capacity, implying that Phe19 packs against Gly38 in wild-type Aβ42 fibrils. In contrast, our data show a 4-residue shift in alignment where Phe19 packs against Leu34 in the fibril conformation. Additionally, the observed Gln15-Gly37 and His13-Gln15 contacts (see Fig. 5 legend) suggest that the N-terminal β-strand starts at least at residue 13, consistent with the solvent exchange studies of Olofsson et al. 13 showing that the first 10, rather than 17, N-terminal residues are unstructured.

In investigating whether the Aβ42 fibrils are composed of multiple β-turn-β units at the fibril cross-section, we had previously reported that Met35 forms an intermolecular contact with Gly37, indicating that the cross-section of Aβ42 fibrils is composed of two β-turn-β units with two-fold symmetry 39. Given the recent literature showing that the packing of the β-turn-β units in Aβ40 fibrils depends on the specific fibril morphology observed by EM 20, we tested other possible contacts along the C-terminal β-strand that would facilitate the packing of multiple β-turn-β units at the fibril cross-section and found no additional contacts (Supplementary Results 1 and 7).

Implications of Aβ42 oligomer structure for toxicity

Stable oligomeric Aβ42 complexes were found to be highly toxic to primary cultures of murine cortical neurons, and the conversion to elongated protofibrils resulted in significantly decreased toxicity. While our samples primarily contain pentamers/hexamers, higher-molecular-weight decamers/dodecamers were also present (Supplementary Results 2), and we have previously shown that these high-molecular-weight oligomers readily form under physiological conditions of temperature and salt 33. Recent evidence suggests that Aβ42 dodecamers derived from APP-overexpressing transgenic mice can impair memory when injected into the brains of young rats 25.

In distinguishing which of the intermediates along the aggregation pathway are responsible for toxicity, Frydman-Marom et al. 42 found that dissociation of dodecamers into smaller trimer/tetramer complexes can lead to cognitive recovery in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. These results agree with our single-touch AFM studies on Aβ42 showing that oligomers having heights of 4–5 nm can be reduced to heights of 2–3 nm in the presence of designed peptide inhibitors that bind to the hydrophobic C-terminus of Aβ42 and inhibit neurotoxicity 33. These studies suggest that the pentamer/hexamer oligomers may be the building blocks of the more toxic decamer/dodecamer complexes. Nevertheless, it remains possible that these oligomers change structure or composition upon interaction with cellular components, such as membrane bilayers, in order to induce cell toxicity. In this regard, Selkoe and co-workers have shown that SDS-stable dimers derived from the brains of patients with AD impair synaptic plasticity and memory 43,44.

One of the major puzzles in the AD field has been how the difference of two amino acids between Aβ40 and Aβ42 can so dramatically change the toxicity and aggregation properties of the peptide. The structural studies reported here indicate that the hydrophobic C-terminal amino acids in Aβ42 stabilize the neurotoxic low-order oligomers in non-β-sheet secondary structure. We find that the conversion to protofibrils and fibrils having β-sheet secondary structure reduces toxicity.

Methods

Peptide synthesis

Peptides were synthesized on an ABI 430A solid-phase peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using tBOC-chemistry. Hydrofluoric acid was used for cleavage and deprotection. Peptide purification was achieved by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography using linear water-acetonitrile gradients containing 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid. Peptide purity was estimated at >90–95% based on analytical reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography. The mass of the purified material, as measured using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry, was consistent with the calculated mass for the peptide and isotopic incorporation.

Sample preparation

Fibril and soluble oligomer samples were prepared by first dissolving purified Aβ42 peptides in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol, flash freezing in liquid nitrogen, and then lyophilizing to completely remove the solvent. Lyophilized Aβ42 peptides were dissolved in a small volume of 100 mM NaOH at a concentration of 10 mg Aβ42 per ml NaOH, and then brought up in either low salt buffer (10 mM phosphate buffer, 10 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) for oligomer studies or in physiological salt buffer (10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) for fibril studies. All samples were titrated to pH 7.4 and filtered with 0.2-micron filters prior to incubation. Oligomer samples were kept at 4 °C for up to 6 h and analyzed by EM, AFM, and immunoblot analysis or flash frozen and lyophilized for solid-state NMR studies. Fibril samples were incubated at 37 °C with gentle agitation for 12 days and then analyzed by EM or pelleted, washed and lyophilized for solid-state NMR studies. Previous studies show that lyophilization of Aβ40 does not appreciably perturb the structure of hydrated oligomers and fibrils 19,36. A final concentration of 200 μM Aβ42 peptide was used for all samples.

Transmission electron microscopy

Samples were diluted, deposited onto carbon-coated copper mesh grids and negatively stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate. The excess stain was wicked away, and the sample grids were allowed to air dry. The samples were viewed with an FEI Tecnai 12 BioTwin 85 kV transmission electron microscope, and digital images were taken with an Advanced Microscopy Techniques camera.

Atomic force microscopy

Single touch AFM was carried out using a LifeScan controller developed by LifeAFM (Port Jefferson, NY) interfaced with a Digital Instruments (Santa Barbara, CA) MultiMode microscope fitted with an E scanner (see Supplementary Results 2 for full methods).

Immunoblots and native gels

Samples of Aβ42 oligomers (incubated for 6 h at 4 °C) and protofibrils (incubated for 6 h at 37 °C or 24 h at 37 °C) were mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and loaded onto 18% (w/v) Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), electrophoresed and transferred onto Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) at 100 V for 1.5 h at 4 °C. Membranes were blocked in 5% (v/v) milk/PBS/0.05% (v/v) Tween20 (PBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature (22 ± 2°C). Anti-Aβ mouse monoclonal antibody 6E10 (Senetek, Napa, CA) was added for 1 h at room temperature, and then washed away 3 × 5 min PBS-T. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated mouse sheep anti-mouse IgG (1:5000 Amersham-Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) was added for 1 h at room temperature, and then washed 3 × 5 min with PBS-T. Bands were visualized using the ECL detection method (Amersham-Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). Molecular sizes for immunoblot analysis were determined using a Benchmark pre-stained protein ladder (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Rainbow molecular weight markers (Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburg, PA). For native gels, samples were loaded onto 10–20% (w/v) Tris-tricine native gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) electrophoresed at 4 °C, and visualized with Coomassie Blue stain (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Molecular weights for native gel analysis were approximated using NativeMark molecular weight standards (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Neuronal cell viability assay

Primary cultures of murine cortical neurons were prepared as described in Supplementary Results 4. Neuronal cultures were treated with Aβ42 oligomer or protofibril samples (final concentration 5 μm Aβ) and incubated for 48 h. The cells were then tested for mitochondrial activity using standard MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylythiazol-2-yl)2,5-diphenyltetrazolim bromide, assay kit (CGD-1 kit, M-0283, Sigma-Aldrich). MTT was added at a final concentration of 0.5 mg ml-1, and the cells were incubated for 4 h. To determine the cellular reduction of MTT to MTT formazan, the reaction was terminated by addition of 200 μL of a cell lysis solution, 0.1 N HCl isopropanol solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and the plate was shaken at 25 °C to allow the MTT formazan precipitates to dissolve. The assay was then quantified by measuring the 570 nm absorbance using a SpectraMax spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Statistical analysis

Results from cell-viability assays were analyzed using two-tailed paired T-test for significance.

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy

Solid-state NMR measurements were made on either a 360, 600, or 750 MHz Bruker AVANCE spectrometer using 4 mm magic angle spinning probes. Two-dimensional 13C dipolar recoupling measurements were carried out using dipolar-assisted rotational resonance (DARR) with mixing times of 600 ms to maximize homonuclear recoupling between 13C labels, as previously described 45,46. Two dimensional 13C DARR spectra exhibit intense diagonal peaks that corresponds to the one-dimensional 13C spectrum and smaller off-diagonal cross-peaks produced by through-space dipolar interactions between 13C-labeled sites that are less than 6 Å apart. The solid-state NMR samples contained approximately 10–20 mg of peptide. 13C chemical shift values are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Molecular modeling

Molecular models were generated using PyMol (Delano Scientific, San Francisco, CA) and Discovery Studio 2.5 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1-AG027317 to SOS and RO1-NS35781 to WEVN) and the Cure Alzheimer's Fund to WEVN. NMR measurements were supported by NIH-NSF instrumentation grants (S10 RR13889 and DBI-9977553), and carried out in part at the New York Structural Biology Center. Electron microscopy experiments were performed at the Central Microscopy Imaging Center, Stony Brook University. We thank Martine Ziliox for assistance with the NMR spectroscopy and critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: M.A., contributed to all aspects the manuscript; D.A., FTIR measurements and analysis; S.A. and T.S., NMR data acquisition; J.D. and W.E.V.N., cell toxicity studies; J.I.E., T.S. and S.A., peptide synthesis and purification; S.O.S., project leader and writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masters CL, et al. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang J, et al. The precursor of Alzheimer's disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature. 1987;325:733–736. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarrett JT, Berger EP, Lansbury PT. The carboxy terminus of the β-amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation - Implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4693–4697. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thinakaran G, Koo EH. Amyloid precursor protein trafficking, processing, and function. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29615–29619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800019200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roher AE, et al. β-amyloid-(1-42) is a major component of cerebrovascular amyloid deposits - Implications for the pathology of Alzheimer-disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10836–10840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwatsubo T, Saido TC, Mann DM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Full-length amyloid-β (1-42(43)) and amino-terminally modified and truncated amyloid-β 42(43) deposit in diffuse plaques. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:1823–1830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burdick D, et al. Assembly and aggregation properties of synthetic Alzheimer's A4/β amyloid peptide analogs. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:546–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borchelt DR, et al. Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Abeta1-42/1-40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron. 1996;17:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckman CB, et al. A new pathogenic mutation in the APP gene (1716V) increases the relative proportion of Aβ42(43) Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2087–2089. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayeux R, et al. Plasma amyloid beta-peptide 1-42 and incipient Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:412–416. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199909)46:3<412::aid-ana19>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirschner DA, Abraham C, Selkoe DJ. X-ray-diffraction from Intraneuronal paired helical filaments and extraneuronal amyloid fibers in Alzheimer-disease indicates cross-β conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:503–507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olofsson A, Sauer-Eriksson AE, Ohman A. The solvent protection of Alzheimer amyloid-β-(1-42) fibrils as determined by solution NMR spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:477–483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lührs T, et al. 3D structure of Alzheimer's amyloid-β(1-42) fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17342–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balbach JJ, et al. Supramolecular structure in full-length Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils: Evidence for a parallel β-sheet organization from solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance. Biophys J. 2002;83:1205–1216. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Balbach JJ, Tycko R. Supramolecular structural constraints on Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils from electron microscopy and solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15436–15450. doi: 10.1021/bi0204185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torok M, et al. Structural and dynamic features of Alzheimer's Aβ peptide in amyloid fibrils studied by site-directed spin labeling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40810–40815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205659200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masuda Y, et al. Verification of the C-terminal intramolecular β-sheet in Aβ42 aggregates using solid-state NMR: Implications for potent neurotoxicity through the formation of radicals. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:3206–3210. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tycko R. Molecular structure of amyloid fibrils: Insights from solid-state NMR. Q Rev Biophys. 2006;39:1–55. doi: 10.1017/S0033583506004173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paravastua AK, Leapman RD, Yau WM, Tycko R. Molecular structural basis for polymorphism in Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18349–18354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806270105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLean CA, et al. Soluble pool of Aβ amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:860–866. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199912)46:6<860::aid-ana8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lue LF, et al. Soluble amyloid β peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsia AY, et al. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3228–3233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh DM, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lesne S, et al. A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caughey B, Lansbury PT. Protofibrils, pores, fibrils, and neurodegeneration: Separating the responsible protein aggregates from the innocent bystanders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:267–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.010302.081142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glabe CG. Common mechanisms of amyloid oligomer pathogenesis in degenerative disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:570–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGowan E, et al. Aβ42 is essential for parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposition in mice. Neuron. 2005;47:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen YR, Glabe CG. Distinct early folding and aggregation properties of Alzheimer amyloid-β peptides Aβ40 and Aβ42 - Stable trimer or tetramer formation by Aβ42. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24414–24422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barghorn S, et al. Globular amyloid β-peptide1-42 oligomer - a homogenous and stable neuropathological protein in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2005;95:834–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bitan G, Vollers SS, Teplow DB. Elucidation of primary structure elements controlling early amyloid β-protein oligomerization. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34882–34889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernstein SL, et al. Amyloid-β protein oligomerization and the importance of tetramers and dodecamers in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Nature Chemistry. 2009;1:326–331. doi: 10.1038/nchem.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mastrangelo IA, et al. High-resolution atomic force microscopy of soluble Aβ42 oligomers. J Mol Biol. 2006;358:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu L, et al. Structural characterization of a soluble amyloid β-peptide oligomer. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1870–1877. doi: 10.1021/bi802046n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gellermann GP, et al. Aβ-globulomers are formed independently of the fibril pathway. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chimon S, et al. Evidence of fibril-like β-sheet structures in a neurotoxic amyloid intermediate of Alzheimer's β-amyloid. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1157–1164. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sciarretta KL, Gordon DJ, Petkova AT, Tycko R, Meredith SC. Aβ 40-Lactam(D23/K28) models a conformation highly favorable for nucleation of amyloid. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6003–6014. doi: 10.1021/bi0474867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarus B, Straub JE, Thirumalai D. Dynamics of Asp23-Lys28 salt-bridge formation in Aβ10-35 monomers. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16159–16168. doi: 10.1021/ja064872y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato T, et al. Inhibitors of amyloid toxicity based on β-sheet packing of Aβ40 and Aβ42. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5503–5516. doi: 10.1021/bi052485f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisenberg D, et al. The structural biology of protein aggregation diseases: Fundamental questions and some answers. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:568–575. doi: 10.1021/ar0500618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ban T, et al. Direct observation of Aβ amyloid fibril growth and inhibition. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frydman-Marom A, et al. Cognitive-performance recovery of Alzheimer's disease model mice by modulation of early soluble amyloidal assemblies. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:1981–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shankar GM, et al. Amyloid-β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cleary JP, et al. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takegoshi K, Nakamura S, Terao T. 13C-1H dipolar-assisted rotational resonance in magic-angle spinning NMR. Chem Phys Lett. 2001;344:631–637. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crocker E, et al. Dipolar assisted rotational resonance NMR of tryptophan and tyrosine in rhodopsin. J Biomol NMR. 2004;29:11–20. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000019521.79321.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.