Abstract

Collagen-chondroitin sulfate biomaterial scaffolds have been used in a number of tissue engineered products under development or in the clinics. In this paper, we describe a new approach based on centrifugation for obtaining highly concentrated yet porous collagen scaffolds. Water uptake, chondroitin sulfate retention, morphology, mechanical properties and tissue engineering potential of the concentrated scaffolds were investigated. Our results show that the new approach can lead to scaffolds containing four times as much collagen as that in conventional unconcentrated scaffolds. Further, water uptake in the concentrated scaffolds was significantly greater while chondroitin sulfate retention in the concentrated scaffolds was unaffected. The value of mean pore diameter in the concentrated scaffolds was smaller than that in the unconcentrated scaffolds and the walls of the pores in the former comprised of a continuous sheet of collagen. The mechanical properties measured as moduli of elasticity in compression and tension were improved by as much as 30 times in the concentrated scaffolds. In addition, our tissue culture results with human mesenchymal stem cells and foreskin keratinocytes show that the new scaffolds can be used for cartilage and skin tissue engineering applications.

Keywords: Biodegradable biomaterials, porous scaffolds, tensile strength, centrifugation, compressive strength, cartilage tissue engineering, cultured skin equivalents

Introduction

Collagen-based biomaterials have tremendous potential as scaffold materials for tissue engineering 1. Type I collagen is the most abundant protein in the human body and is the primary constituent of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in most tissues. Collagen-based biomaterials have been used in clinical trials in the treatment of defects in skin 2, cartilage 3, urethra 4, meniscus 5, and bone 6. Collagen-based biomaterials used for tissue engineering applications can generally be classified into two different categories: hydrogels and porous scaffolds.

Collagen hydrogels are made as collagen molecules in aqueous solution, and under appropriate conditions, spontaneously assemble/gel to form a semisolid structure. Such gels are widely used to study cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions in a variety of biological processes as cells can be incorporated in the solution prior to gelling 7,8. In addition, with support, these gels are also used in a variety of tissue engineering applications 1,8,9. A downside to the use of gels for tissue engineering is their lack of mechanical stability; collagen gels are difficult to handle in a clinical setting. While techniques such as cross-linking and other chemical modifications, and cell-mediated contraction can be used to make the gels stronger 10-15, gels are still mechanically inferior to dry scaffolds.

The other category of biomaterials is dry porous scaffolds. Several types of synthetic and natural biomaterial scaffolds are used to develop tissue engineered constructs. Among collagen-based copolymers, porous collagen-glycosaminoglycan (CG) scaffolds hold great potential for use in tissue engineered products 16. CG scaffolds are produced by lyophilizing a CG-acetic acid solution, which results in a continuous dry porous CG scaffold suitable for cell seeding. Such lyophilized scaffolds are mechanically superior to collagen gels. They also have several advantageous properties compared to scaffolds made from other materials: CG scaffolds are made from a natural material common to the extracellular matrix of most tissues; they possess haemostatic properties, low antigenicity, and appropriate mechanical characteristics for use in tissue engineering applications. They have also shown an excellent ability to promote cell attachment and proliferation in a wide variety of tissue engineering applications 17-19.

The physical and chemical properties of the bulk scaffold material determine the theoretical upper limit of the mechanical properties of the scaffold. The actual mechanical properties of a useful scaffold product will be lower, and depend largely on the structure of the scaffold, itself the result of a compromise designed to meet biological and mass-transport needs. For collagen-based scaffolds, the modulus of pure collagen has been estimated at between ~3 and 9 GPa 20, which leaves ample room for compromise when designing for most tissues.

Despite the potential of porous CG scaffolds, their physical, chemical, and biological properties must be optimized for the targeted tissue. The pore size and structure of CG matrices greatly affects their cell-adhesion 21,22 and mass-transport characteristics. Pores must be large enough to allow for cell migration into the scaffold, but increasing pore size also decreases the surface area available for cell adhesion. This suggests that pore size and structure can be tuned to maximize cell attachment and growth. In addition, the pore size and volume fraction also affect the mass-transport of nutrients and waste to and from the cell in the scaffold, as well as the transport of signaling molecules between cells. A more densely packed scaffold increases the resistance to mass transfer of nutrients and waste, but a looser scaffold increases the number of cells that can attach. This suggests the existence of an optimal scaffold composition that balances the number of cells that can be attached to the scaffold with the transport of nutrients and waste to and from these cells required for cell viability and growth. Constructs with tunable properties of volume fraction, pore size distribution and mechanical strength, therefore, are needed to satisfy the cell adhesion and mass transport demands placed on them by different tissue engineered systems. Previously, the average pore size in CG scaffolds could be varied by changing the process parameters of lyophilization 22. The final freeze-drying temperature has been shown to control the pore size of the eventual scaffolds to some extent; a lower freeze-drying temperature led to a smaller mean pore size, and a range of pore sizes, from 150 to 95 micrometers, were obtained 22.

Despite these advances, the base concentration of the solution used to obtain CG scaffolds for tissue engineering applications was limited by the solubility of collagen; in all studies, the maximum collagen concentration used was about 0.25 % w/v. This limits the final collagen density that can be obtained in the scaffolds, which subsequently impacts the physicochemical properties of the scaffolds. We have developed a new, simpler method that allows for greater control over collagen concentration in the scaffolds using solution centrifugation. We have found that centrifugation and subsequent removal of supernatant of the CG solution before lyophilization resulted in scaffolds that have a range of collagen concentration, mechanical properties and water uptake characteristics. We further show evidence for the potential use of these scaffolds in cartilage and skin tissue-engineering applications.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Type I bovine collagen and chondroitin 6-sulfate (from shark cartilage) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Cell culture base media included Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium with either 4.5 g/l – DMEM-HG or 1.5 g/l glucose – DMEM-LG, and keratinocyte serum-free medium (K-SFM). These, as well as trypsin, L-glutamine, antibiotic/antimycotic (105 units/ml penicillin G sodium, 10 mg/ml streptomycin sulfate, and 25 μg/ml amphotericin B in 0.85% saline), non-essential amino acids, and sodium pyruvate were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) or Mediatech (Herndon, VA). Transforming growth factor beta -1 (TFG-β1) was obtained from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ); recombinant human fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) was generously provided by the Biological Resources Branch of the National Cancer Institute. ITS+ Premix™ was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA), and ascorbate-2-phosphate was procured from Wako (Richmond, VA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Invitrogen, after screening as described by Lennon et al.23. Bovine calf serum was from Hyclone (Logan, UT). Collagenase was from Worthington Chemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ). Percoll, Hoechst 33258 dye, dexamethasone, papain and Tyrode's salt solution were from the Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). DNA standards were from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ), while chondroitin sulfate C standards were from Seikagaku America (East Falmouth, MA). All cell culture plasticware was from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Antibodies to collagen type I were from Sigma, anti-collagen type II was from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma bank (University of Iowa), while anti-collagen type X was a gift from Dr. Gary J. Gibson. Mouse pre-immune IgG was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Derived media for culturing composite skin substitutes were keratinocyte seeding medium (KSM), keratinocyte priming medium (KPM) and air-liquid interface medium (ALIM). The composition of KSM is: (3:1) DMEM/Ham's F12 medium, 1% FBS, penicillin(100-IU/ml)-streptomycin(100 μg/ml), 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid (Sigma), 10-10M cholera toxin, 0.2 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 5 μg/ml insulin, antibiotic cocktail: 100 μg/ml gentamycin (Sigma), 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin B (Invitrogen), and 100 IU/ml-100 μg/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). The composition of KPM is: 24 μM bovine serum albumin (Sigma), 1 mM L-serine (Sigma), 10 μM L-carnitine (Sigma), and fatty acid cocktail: oleic acid (25 μM, Sigma), linoleic acid (15 μM, Sigma), arachidonic acid (7 μM, Sigma) and palmitic acid (25 μM, Sigma) in KSM. The composition of ALIM is: 1 ng/ml of epidermal growth factor (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA) in KPM. Software packages used for data acquisition and analysis include ImageJ (NIH, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), ImagePro (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD), Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), and Origin (OriginLab, Northampton, MA).

CG solution

The base collagen-chondroitin sulfate (CG) solutions were made by using a method adopted from Yannas, et al.16. In short, 0.55 g of Type I bovine collagen was added to 200 ml of 0.5 M acetic acid solution (2.75 mg/ml). The solution was then blended in an ice-bath cooled vessel using an overhead homogenizer (IKA Works, Wilmington, NC) at a speed of 13,500 rpm. After 20 minutes of blending, 0.055 g of chondroitin 6-sulfate, dissolved in 10 ml of 0.5 M acetic acid solution, was added drop-wise to the collagen solution. The solution was homogenized for an additional 20 minutes at 13,500 rpm. The final concentrations of collagen and chondroitin sulfate in the CG solutions were about 2.6 and 0.26 g/liter respectively.

Concentrated CG solution and scaffolds

A batch of 840 ml of CG solution were prepared using normal techniques. 40 ml CG solution was aliquoted for centrifugation. Each aliquot was centrifuged for a period ranging from 0 to 60 min at 38720 × g (r.c.f.) with an automatic superspeed refrigerated centrifuge (RC-5C, Sorvall Instruments, DuPont, Wilmington, DE). After centrifugation, a percentage of the solution was removed from the top of each aliquot. The remaining solution and the collagen pellet were mixed thoroughly, frozen and lyophilized following the procedure. All CG scaffolds fabricated in this study underwent a dehydrothermal process after freeze-drying to strengthen the collagen network. CG scaffolds were dehydrated for 48 hours at 120 w°C under vacuum (40 mTorr).

Water uptake

Water-uptake experiments were performed by obtaining 10 mm diameter disks of scaffolds using a biopsy punch, weighing the dried scaffolds, and then weighing the hydrated scaffolds after they were hydrated thoroughly after four days (n=6).

Chondroitin Sulfate content

Scaffolds obtained from various concentrated solutions were used to quantify retained chondroitin sulfate (CS). After the water-uptake experiment, the same 12 mm diameter disks of hydrated scaffolds were placed in 2.0 ml Eppendorf tubes and dried using a Speed-vac (Savant, Thermo-Fisher, Waltham, MA). The CS amount in the scaffolds was quantified by a GAG assay performed as described previously, with some modifications 24-26. Briefly, scaffolds were digested with 1.0 ml of papain buffer (25 μg/ml papain; 2 mM cysteine; 50 mM NaH2PO4; 2 mM EDTA; pH 6.5)27 at 65 °C. After the digestion was complete, the scaffold extracts were transferred to a 5 ml tube and an additional 1.0 ml of papain buffer was added for dilution. A 0.45 μm pore-size nitrocellulose membrane was pre-wetted with dH2O and placed into a dot-blot apparatus. A 250 μl aliquot of 0.02% Safranin O in 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.8) was pipetted into each well, followed by 25 μl aliquots of the papain-digested extracts or standards (shark-cartilage chondroitin sulfate C) 24. After vacuuming, the wells were rinsed with dH2O, and the filter was removed from the apparatus. Individual dots were cut out, transferred to microcentrifuge tubes and eluted in 10% cetylpyridinium chloride at 37 °C. The absorbance of the eluates was read at 530 nm in a microplate reader.

Imaging and Image Analysis

The microstructures of the lyophilized vacuum dried scaffolds in the cross-section were observed under scanning electron microscopy (XL30, Philip, Eindhoven, Netherlands). Some samples were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde overnight at room temperature, embedded in ethylene glycol-methacrylate (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA), and sectioned. The mean pore size of the scaffolds was determined by analyzing SEM images. Three SEM images of each scaffold (n=6) were selected and at least fifteen apparent pores were measured with image analysis software from each image. The mean pore size of each pore was calculated by averaging the major and minor axes lengths. 28-30.

Mechanical Strength Testing

Tensile tests

The tensile properties of dry CG scaffolds were assessed via tensile testing (n=7 for each condition). CG scaffolds were cut into dogbone-shaped specimens with a gauge length of 22 mm and width of 5 mm. They were then tested to failure using an Instron model 5565 (Canton, MA) at a strain rate of 1.4 mm/min. The elasticity modulus (ab) was determined by fitting the experimental data of stress (σ) and strain (ε) with the following model 31 consisting of two parameters a and b:

| (1.1) |

Compression tests

Disc-shaped CG scaffolds were obtained by using a 10-mm biopsy punch (Acuderm, Inc., Ft. Lauderdale, FL). The thickness and mass of the samples were measured. The compressive modulus of each disc was determined in a Rheometrics Solids Analyzer II compression device (Piscataway, NJ). Each disc was compressed for 3 seconds at a strain rate of 5% s-1. Compression tests were performed on six samples per condition, so that an average compressive modulus could be ascertained. A stress-strain curve was then recorded by a computer data acquisition system, and transferred to Excel® to determine an average compressive modulus of elasticity (ϕ) based on the equation: σCompression = ϕ 32.

CG scaffolds for cultured skin substitutes

Kerationocytes were isolated from discarded neonatal human foreskins by the method of dispase digestion followed by trypsin treatment as described in Papini, et al. 33. The procedure was approved by the University Hospitals of Cleveland Institutional Review Board. The cells were subsequently cultured in KSFM. The medium was changed every three days, and the cells were passaged when they reached 90% confluence. To prepare skin constructs, we used passage 2-3 cells. Skin substitutes were prepared using CG scaffolds as described by Medalie, et al. 34,35. Briefly, keratinocytes were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells/cm2 onto 2-cm2 CG scaffolds using KSM, and the scaffolds cultured in submerged mode in KSM for 2 days, then in KPM for 1 day. The epidermal portion of the constructs was then exposed to air and they were cultured in ALIM for 7 days, with medium replaced every 2 days.

For histology, cultured skin substitutes were rinsed with PBS, and fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin and paraffin-embedded. Adjacent seven μm-thick sections were either stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or were stained for human involucrin by indirect immunofluorescence. H&E-stained sections were mounted in permount. For immunofluorescence, antigen unmasking was done by digesting the sections with trypsin for 5 minutes after rehydration. The primary antibody (ab68, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was applied for 1 hour at room temperature at 1:200 dilution. Primary antibody was omitted on some sections as a negative control. After rinsing, a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat-anti mouse secondary (Zymed, Carlsbad, CA) was used at 1:50 for 45 minutes. Stained sections were mounted in 5% n-propyl gallate in glycerol, and documented immediately. Sections were photographed with a SPOT-RT digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) at 10× using a Leica fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

CG scaffolds for MSC-based chondrogenesis

Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were obtained from 4 healthy adult volunteer donors, using a procedure approved by the University Hospitals of Cleveland Institutional Review Board; informed consent was obtained from all donors. The cells were prepared using a Percoll centrifugation step as described by Haynesworth et al. 36 and us elsewhere 26. The cells were plated in serum-supplemented medium 37 at 1.8 × 105 nucleated cells/cm2. After four days, non-adherent cells were removed by replacing the medium, which was now supplemented with 10 ng/ml FGF-2, as we have previously shown that expansion in the presence of FGF-2 improves subsequent chondrogenesis 38. The medium was replaced every third day for two weeks, after which the cells were subcultured using trypsin 39 and replated at 5 × 103 cells/cm2. Chondrogenic medium was composed of DMEM-HG supplemented with 1% ITS+ Premix™, 100 μM ascorbate-2-phosphate, 10-7 M dexamethasone, and 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 40. Additional supplements such as L-glutamine, antibiotic antimycotic, non-essential amino acids, and sodium pyruvate were also added at 1%.

The scaffolds were stored at 4 °C until just prior to use. They were then cut to size using a 7-mm diameter punch and transferred to 100% EtOH in a 24-well plate. The ethanol was then aspirated, and the sponges were dried in a vacuum chamber at room temperature. 107 cells were suspended in a volume of chondrogenic medium such that the total volume equaled the water uptake capacity of the scaffold (Figure 3), and the cells were vacuum-seeded onto the scaffolds as described previously 41. After 60 minutes the constructs were flipped over and incubated for an additional hour, and then they were placed into custom bioreactors perfused with chondrogenic medium 42. The bioreactor chamber consisted of a rigid metal/plastic composite frame with gas-permeable windows sealed with silicone rubber gaskets to provide gas exchange. The chamber is suitable for constructs up to 20×20 mm. The wetted parts were replaceable; the frames are fitted with media ports. Medium was pumped through the chamber at 250 μl/h using a syringe pump; waste medium was not recycled. The system is housed in an incubator at 37°C with 7.5% CO2.

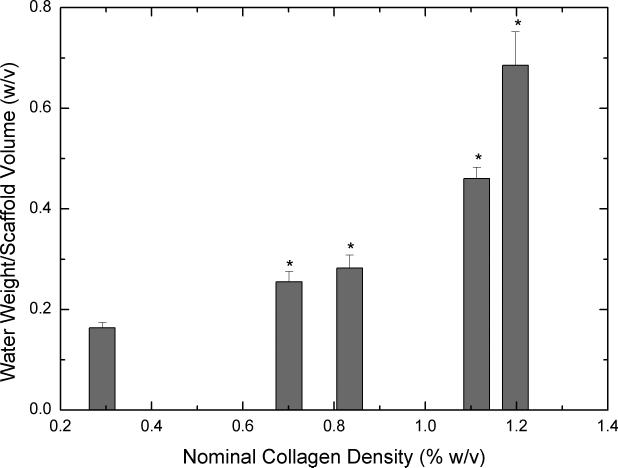

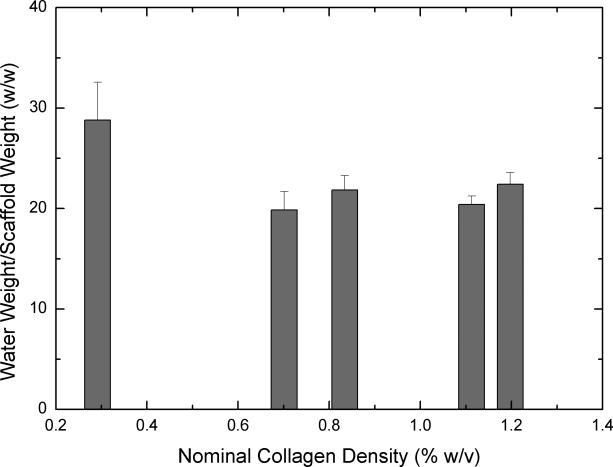

Figure 3.

Equilibrium water uptake by scaffolds (n=6 each) obtained from concentrated collagen-CS solutions after four days of hydration. 3A shows mass of water uptake per total volume of the scaffold. 3B shows mass of water uptake per overall weight of the scaffold. Error bars represent SEM. * represents statistical significance relative to scaffold obtained from base solution.

Some constructs were retrieved from the bioreactors on day 1 to verify seeding; the remaining constructs were cultured for 21 days to verify chondrogenesis. Half of each construct was fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded and sectioned. Adjacent sections were either stained with Toluidine Blue-O to evaluate proteoglycan content, 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to evaluate cell distribution, or by an indirect immunofluorescence assay using a antibodies against collagen types II and X 26. FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was used as a secondary antibody, mouse pre-immune IgG and no-primary were used as negative controls. The slides were then wet-mounted using 5% N-propyl gallate in glycerol. Sections were photographed as described above with a SPOT-RT digital camera at 10× using a Leica fluorescence microscope, and a montage of the entire construct was made from individual images 43.

Statistical Analysis

For all quantitative results, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison procedures were performed to compare data groups. A p value less than 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

General Scaffold Characterization

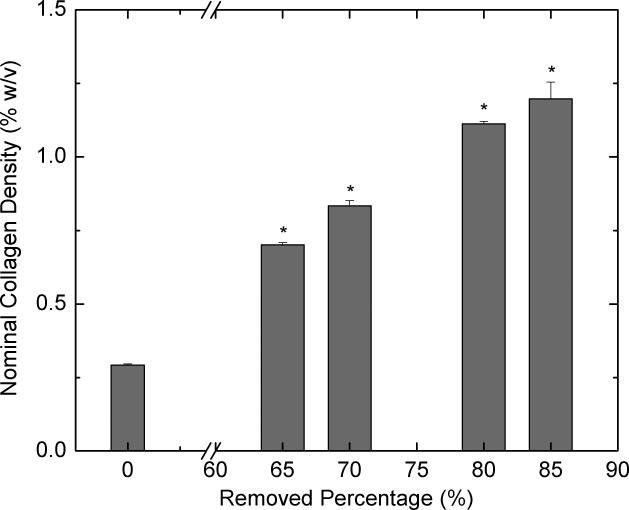

Figure 1 shows the effect of centrifugation on the collagen concentration. By removing different amounts of supernatants, collagen solutions of different concentrations were obtained. The average collagen-CS concentration of scaffolds (dry mass of scaffold/volume of scaffold, %w/v) was plotted as a function of the percentage of the total solution removed as supernatant. We can obtain scaffolds that have dry collagen-CS content ranging from 2 (65% removal) to 5 (85% removal) times that of the scaffolds from unconcentrated solution. Unconcentrated scaffolds had a nominal collagen density of 0.26 % w/v. Clearly, increasing the amount of supernatant removed increased the concentration of the collagen-CS in the scaffolds (p<0.05). Removing supernatant amounts >85% of total solution was difficult as this led to the removal of the collagen precipitate. Further, the centrifugation time had very little effect on the concentrated scaffolds (data not shown); a centrifugation time of 20 minutes was sufficient to achieve the final concentration.

Figure 1.

Effect of centrifugation on nominal density of lyophilized scaffolds. Collagen-CS solution (40 ml) is centrifuged for 20 minutes at 37,000×g (r.c.f) and various amounts of supernatants (0, 65, 70, 80 and 85%) were removed and the pellet is reconstituted in the remaining solution. The reconstituted solution is frozen and lyophilized to obtain a dry scaffold. The bulk density of the scaffolds (n=7 ea.) is shown as a function of the percent solution removed. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). * represents statistical significance relative to base solution (0% removed).

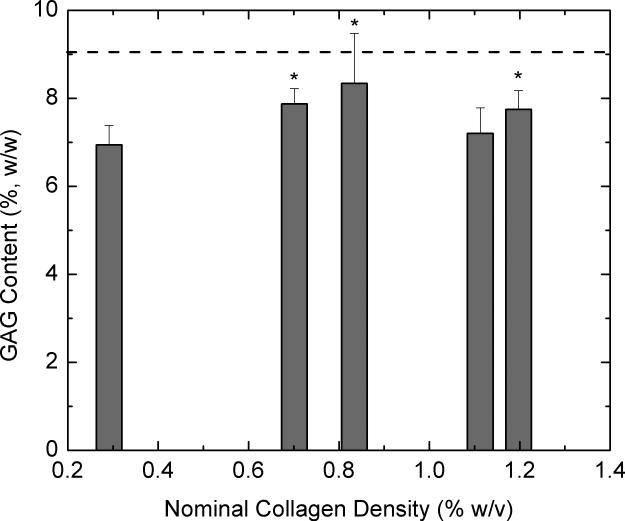

To understand the effect of concentration on the retention of CS, we performed GAG assays on scaffolds obtained by these different procedures. CS was retained in the concentrated scaffolds at levels similar or greater than the levels in the unconcentrated scaffolds (Figure 2). The dashed line in Figure 2 indicates the level of CS added to the solution before homogenization.

Figure 2.

GAG content (%, GAG weight/total scaffold weight) of the scaffolds (n=6 each) obtained from concentrated collagen-CS solutions as a function of nominal scaffold density. Dashed line represents the amount of GAG added to the solution. Error bars represent SEM. * represents statistical significance relative to scaffold obtained from base solution.

Water uptake is an important indicator used to determine the suitability of a biomaterial for tissue engineering. Further, for a CG scaffold, water uptake is dependent not only on the amount of collagen in the scaffold but also the pore characteristics of the scaffold. Figure 3 shows water uptake of scaffolds obtained from concentrated collagen-CS solution when hydrated for four days. On a per volume basis (3A), all concentrated scaffolds have significantly increased water uptake when compared to unconcentrated scaffolds. On a per dry scaffold weight (3B), however, although water uptake of scaffolds from concentrated solutions seemed to decrease the results were not statistically significant when compared to water uptake of scaffolds from unconcentrated solution.

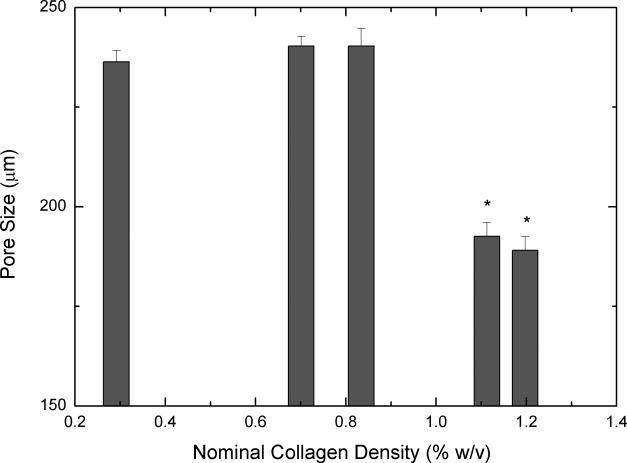

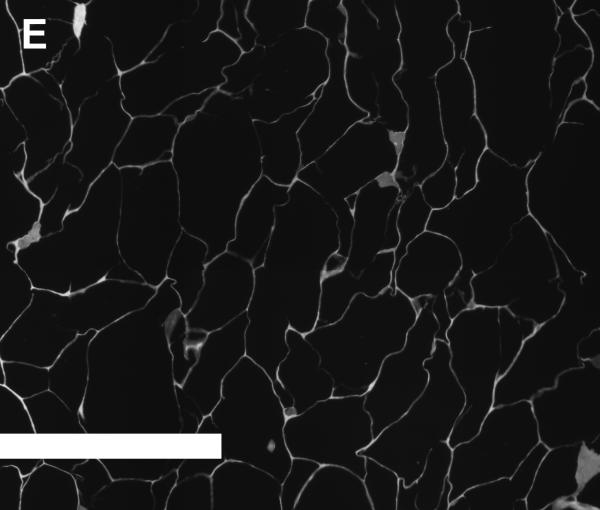

Pore Structure

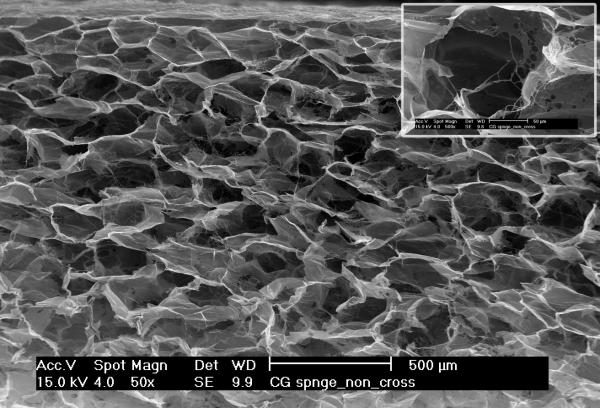

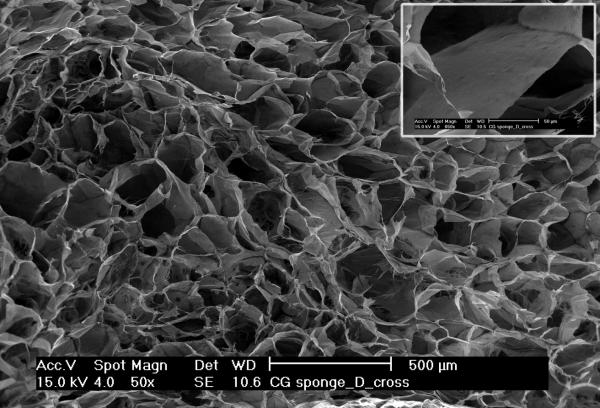

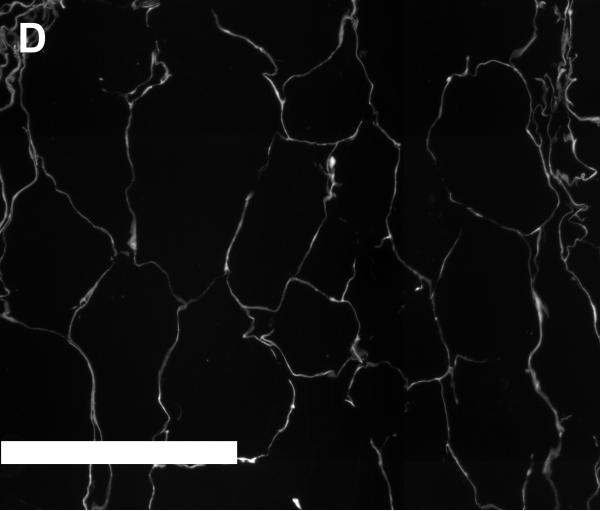

Figures 4A and 4B show SEM images of scaffolds that were obtained from unconcentrated (0.3% w/v, 4A) and concentrated (1.2% w/v, 4B) collagen-CS solutions. The unconcentrated scaffold pores appear circular and slightly larger. Further, the walls of the pores were made up of porous fibers of collagen (insert in 4A). On the other hand, the pores of concentrated scaffolds while circular were slightly smaller. More importantly, the walls of the pores were made of continuous sheet of collagen fibers (insert in 4B). To better illustrate the difference in pore structures, we obtained plastic embedded scaffolds and sectioned them (3 micrometer intervals). Figures 4D and 4E show typical pore structures of such sections obtained from unconcentrated (0.3% w/v, 4D) and concentrated (1.2% w/v, 4E) collagen-CS solutions. The pores appear larger in unconcentrated samples whereas they appear smaller and more in number in the concentrated samples. Image analysis of all the various scaffolds (Figure 4C) show that the pore mean diameter decreased by as much as 20% as the collagen concentration increased (p<0.05). Overall porosity (ε), estimated from the equation: where m is the nominal density of collagen scaffold and ρ is the density of anhydrous collagen (1.3 g/ml) for both concentrated and unconcentrated scaffolds were, however, very high and ranged from 0.98 (concentrated) to 0.995 (unconcentrated).

Figure 4.

SEM Images (4A & 4B) of scaffolds (4A: scaffold from base collagen-CS solution with a collagen nominal density of 0.3 % w/v, 4B: scaffold from concentrated solution with a nominal density of 1.2 % w/v). Figure 4C shows pore size vs. nominal collagen density of scaffolds. Images of plastic embedded 3-micrometer sections of scaffolds formed from base collagen-CS solution with a collagen nominal density of 0.3 % w/v (4D), and from concentrated solution with a nominal density of 1.2 % w/v (4E). Scale Bar is 250 μm.

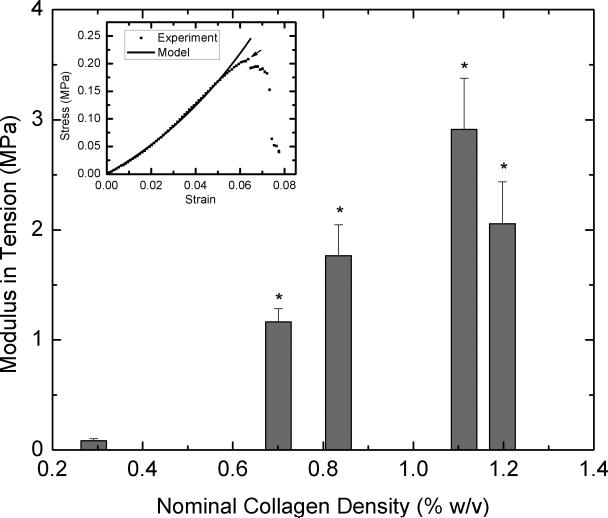

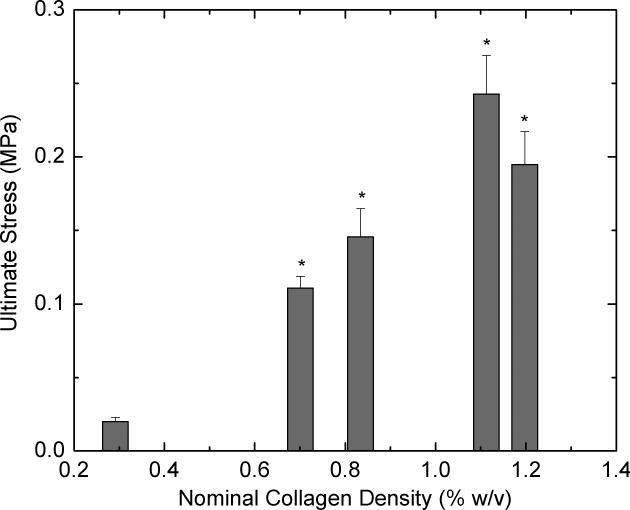

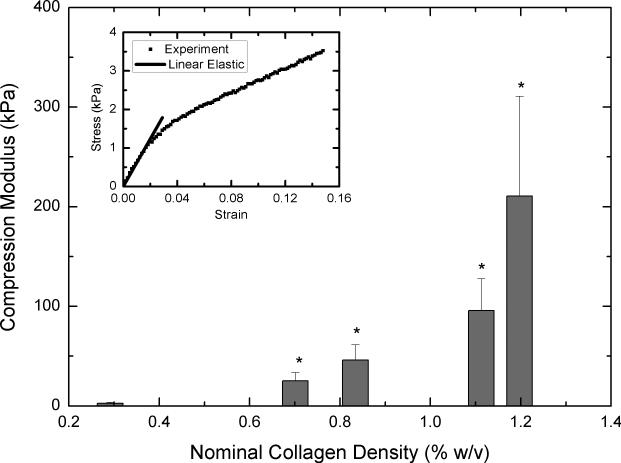

Mechanical Properties

To determine whether concentrating collagen-CS solution leads to scaffolds with improved mechanical properties, we performed tensile and compressive loading tests on dry scaffolds that were not chemically fixed. Tensile loading was carried out on samples until they fail. Figure 5A shows modulus of elasticity values for various scaffolds obtained from concentrated collagen-CS solutions. All concentrated scaffolds were significantly stronger and had modulus of elasticity values as much as 33 times greater when compared with unconcentrated scaffolds (nominal collagen density: 0.3 % w/v). The improvements were disproportional to the collagen density values; tripling the collagen density increased the modulus of elasticity by 30-fold. The modulus of elasticity in tension decreased by about 30% when the nominal collagen increased from 1.1 to 1.2 % w/v. Figure 5B shows ultimate stress values of the scaffolds at failure. Again, the concentrated scaffolds performed better, and had ultimate stress values as much as 12 times greater than those of unconcentrated scaffolds. The increases were disproportionately larger than the increases in collagen content of the scaffolds. The ultimate stress also decreased by about 20% when the nominal collagen increased from 1.1 to 1.2 % w/v. Further, to understand whether these results also indicate the scaffolds ability to resist compression, we subjected the samples to compression. Figure 6 shows compressive modulus of elasticity as a function of nominal collagen density. The results are similar to those under tension; the concentrated scaffolds had elastic moduli that are as much as 56 times greater than that of unconcentrated scaffolds. The increases in the modulus of elasticity values were achieved with relatively smaller increase (3-4 fold) in collagen density.

Figure 5.

Tensile strength of the scaffolds. Lyophilized scaffolds (n=7 each) obtained from concentrated collagen-CS solution were cut to dog-bone shapes and subject to tension in a universal testing machine. 5A shows tensile modulus of elasticity of the scaffolds and 5B shows the ultimate stress as a function of nominal collagen density. Error bars represent SEM. * represents statistical significance relative to scaffold obtained from base solution.

Figure 6.

Compressive strength of the scaffolds. Lyophilized scaffolds (n=6 each) obtained from concentrated collagen-CS solution were cut to dog-bone shapes and subject to compression. Figure shows compressive modulus of elasticity as a function of nominal collagen density. Error bars represent SEM. * represents statistical significance relative to scaffold obtained from base solution.

Tissue Engineering Potential

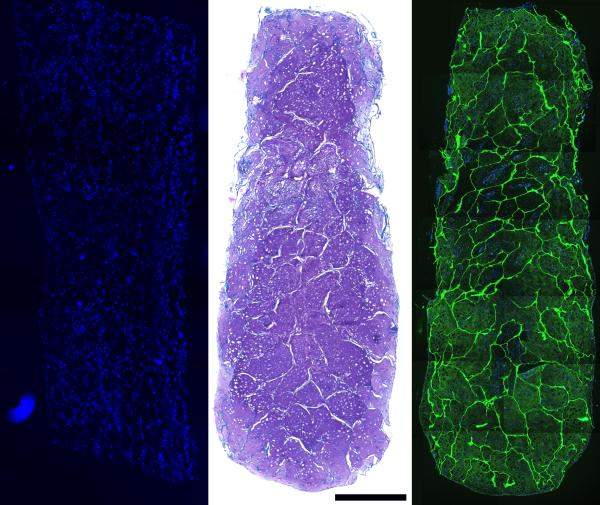

To evaluate the potential for tissue engineering applications, we used the concentrated scaffolds (nominal collagen density: 0.8 % w/v) to culture cartilage constructs and skin tissue constructs in vitro. We chose to use the 0.8 % w/v scaffold, as based on its properties such as water uptake, and moduli of elasticity, it was average and represented the concentrated scaffolds. Cross-sections of the cartilage constructs harvested immediately after seeding show cells in the scaffold voids throughout the entire thickness of the scaffold, suggesting good interconnectivity of the scaffold pores (Figure 7, Left). After 3 weeks of culture, the void spaces had been filled with cell-derived ECM which was positive for proteoglycans by Toluidine Blue O staining (Figure 7, Center), and immunoreactive for collagen type II by immunohistochemistry (Figure 7, Right). No type I and only trace type X immunoreactivity were detected (Not shown). At 3 weeks, scaffold fibers remained evident in the neo-ECM.

Figure 7.

Left: DAPI stained section of MSC-seeded scaffold, harvested on day 1 show cell distribution after vacuum seeding. Center: Toludine Blue-O staining, after 3 weeks in bioreactor culture under chondrogenic conditions. Right: type II collagen immunoreactivity in a construct with DAPI overlay after 3 weeks of bioreactor culture. Scale bar is 1000 μm.

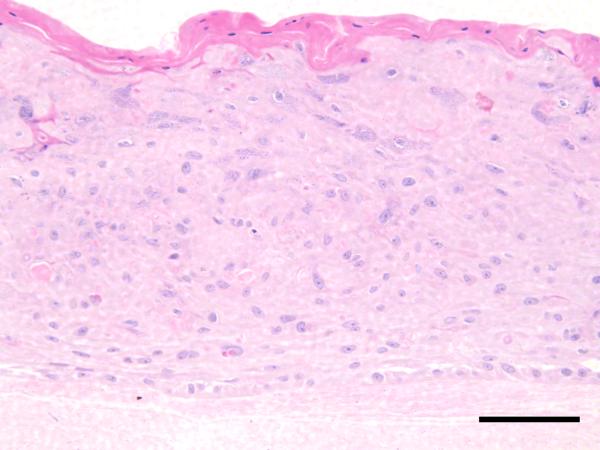

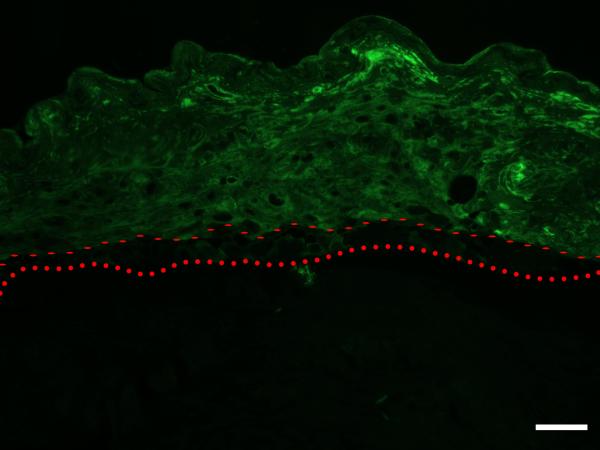

H & E stained cross sections of the cultured skin substitutes show that, although somewhat immature, clear basal and corneal layers were formed, along with a partially organized granular layer (Figure 8, Top). Immunostaining results show that involucrin immunoreactivity is appropriately localized 44, with the protein being down-regulated in the basal keratinocyte layer (Figure 8, Bottom).

Figure 8.

Top: H & E stained section of skin-construct tissue-engineered using human foreskin keratinocytes seeded onto a scaffold of nominal density 0.8 % w/v, and cultured for 7 days. Although somewhat immature, clear basal and corneal layers are present, and a partially organized granular layer can be recognized. Scale Bar is 100 μm. Bottom: Involucrin immunoreactivity is appropriately localized, with the protein being down-regulated in the basal keratinocyte layer. Dotted line – upper edge of collagen-CS scaffold. Dashed line – upper edge of basal layer. Scale Bar is 100 μm.

Discussion

In this work, we developed a technique to obtain porous collagen-glycosaminoglycan scaffolds of varying collagen concentrations for tissue engineering application. We showed that these scaffolds have concentration-dependent water-uptake rates, mechanical properties and pore geometry. We further showed that these scaffolds are biocompatible for cartilage and skin tissue engineering.

Researchers typically use the base CG solution (collagen 0.26 % w/v) for tissue engineering applications. The base concentration is limited by the solubility of collagen; which further limits the final collagen density that can be obtained in the scaffolds. This leads to a porous scaffold that is mechanically difficult to handle, and often collapses when exposed to water unless the scaffold is cross-linked either chemically or by other means such as dehydrothermal process. By centrifuging at relatively high centrifugal force, we can obtain a collagen concentration as high as 5 times greater than the commonly-used CG scaffolds 16. Further, by diluting this highly concentrated collagen, we can obtain a range of concentrations corresponding to scaffolds of varying properties. The process of centrifugation is rapid (5-20 minutes) as the collagen solution sediments rapidly due to the relatively large centrifugal force applied. To our knowledge, our technique of centrifugation of collagen solution to obtain scaffolds of tunable properties, while simple, is also new. Varying the freezing rate during the lyophilization process has been shown to result in collagen scaffolds of tunable properties such as the pore size.21 This technique, based on the physics of the lyophilization process, however, is technically more difficult to implement, and it is not clear whether the resulting benefits extend to better control over the mechanical properties of the scaffolds.

Morphometric analysis of scaffolds imaged through electron microscopy (SEM) show that scaffolds obtained from concentrated CG solutions have more but smaller pores compared to scaffolds obtained from unconcentrated CG solution. Although increased amount of collagen in the scaffolds obtained from concentrated solutions can lead to smaller overall void volume, this does not directly indicate smaller pores. The smaller pores indicate that the initial CG solution is highly homogeneous. Despite the change in pore size, the estimated overall porosity, however, remains high >98% possibly because of complimentary change in the number of pores. This suggests that we can use the scaffolds obtained from concentrated CG solutions for tissue engineering applications requiring high cell-scaffold interactions as well as cell-cell interactions. Further, since the porosity of these scaffolds is similar to the scaffolds obtained from unconcentrated CG solution, the amount of cells seeded in the former scaffolds will not be affected. The latter scaffolds, however, have inferior mechanical properties, collapse during seeding, and are difficult to handle. Our results also suggest a range of pore sizes that can be obtained from our method. Researchers traditionally use freezing temperature and other lyophilization parameters to control the pore size of such scaffolds 22. Our technique presents a much simpler alternative, which not only can control the pore size but also can increase the mechanical properties of scaffolds.

An important property of CG scaffolds is that CS plays a critical role in stabilizing scaffold structure by inducing efficient ‘stress transfer’ in collagen fibrils 45. In addition, CS affects important biological properties such as cell adhesion and proliferation, and in general, cell signaling 16. Therefore, CS retention in the concentrated scaffolds is an important parameter. Our results demonstrate that the concentrated scaffolds retain the same ratio of GAG to collagen (1:10 by mass) thus suggesting that the new process does not diminish the beneficial effect of GAG on the general scaffold stability and function. Water retention by scaffolds is an important property that has implications in cell seeding and mass transport. Our results indicate that the scaffolds made from concentrated CG solution take up more water per volume of the scaffold than those made from base CG solution. In general, water absorbed by porous scaffolds is characterized as: substrate-bound water and free water. The amount of bound water is on the order of 0.35 g/g of collagen 46. Since the amount of water uptake in our scaffolds is substantially greater (30-150 g/g) than this value, most of the water in the scaffolds is free. Our results show that the water uptake per overall scaffold weight basis does not change with collagen density, and since most of the water in the scaffolds is free, the results suggest that the greater water uptake in concentrated scaffolds is not as a result of increased amount of collagen but due to the pore size and the maintenance of three-dimensional structure, two important factors that determine the amount of free water in porous scaffolds.

An important characteristic of TE scaffolds is to provide an adequate mechanical environment until matrix production by the cells takes over. The optimal environment depends on the tissue that is targeted. For example, typical compressive modulus of knee articular cartilage is about 7 MPa 47 and tensile modulus of excised adult human skin is about 50 MPa 48. Therefore, it is important to have scaffolds with tunable mechanical properties. Depending on the type of tissue, performance under either tensile, compression or both can affect the ultimate function of the product in vivo. Although there are scaffolds made from synthetic materials that have tunable mechanical properties (PEGDA, alginate, etc.), but tuning mechanical properties of collagen-based scaffolds is under-investigated. Our results suggest that concentration of CG solution can lead to scaffolds that have wide-ranging mechanical properties. In the case of cartilage tissue engineering application, the concentrated scaffolds have a compressive modulus of elasticity an order of magnitude less than that of the native tissue, which is an improvement compared to other similar scaffolds 32 and a huge improvement over unconcentrated scaffolds. In the case of skin tissue engineering, the concentrated scaffolds have a tensile modulus of elasticity that is an order of magnitude less than that of the native tissue but still better than that of similar scaffolds fabricated by other researchers 32. It should be mentioned that while the increases observed in dry scaffolds will also be reflected in wet scaffolds, in general, wet scaffolds have inferior mechanical strength when compared to dry scaffolds.

The increases observed in compressive and tensile moduli of elasticity in the concentrated CG solution scaffolds are both due to increased collagen and changes in pore geometry and distribution. Increasing the density of collagen in the scaffold is expected to increase the mechanical strength of the scaffold, as the elastic modulus is proportional to the square of the nominal collagen density 32. In our scaffolds, the observed increases in tensile and compressive moduli, however, cannot be explained by the increase collagen density alone. The increases are disproportionally higher: 30-fold and 56-fold increases in tensile and compressive moduli, respectively, for a 4-fold increase in collagen density. It is possible that the base pore structure of the scaffold itself is changed as the collagen density is increased. Smaller pores and pore walls that are comprised of a continuous sheet of collagen in scaffolds made from a concentrated CG solution improve the mechanical properties of the scaffold. A contradiction in our results is that the tensile tests showed that modulus of elasticity and ultimate stress decreased when the nominal collagen density increased from 1.1 to 1.2 % w/v. This is probably due to the accuracy with which we can delineate the collagen density in the highly concentrated scaffolds. Indeed, scaffolds obtained after removing 85% solution as supernatant have a wider range of nominal collagen density as shown in Figure 1, and could lead to the disparity in the results. In designing scaffolds with tunable mechanical properties, a compromise must be struck between providing adequate handling properties and ensuring that we do not stress-shield the cells to the point that external beneficial mechanical stimulation is compromised. In addition, improving mechanical properties by increasing collagen concentration should be balanced with the degradation rate required for the tissue targeted as degradation rate decreases with increases in collagen density of the scaffolds.

From a practical tissue engineering perspective, these scaffolds performed quite well. The scaffolds could be stored, handled, cut to size, and sterilized without difficulty. The excellent seeding characteristics of the scaffolds used in the chondrogenesis experiments suggest that they are suitable for a variety of tissue engineering applications. After 3 weeks of bioreactor culture, the cell and GAG contents and the collagen distributions were indistinguishable from those obtained in small-scale scaffold-free aggregate culture 25, suggesting that the scaffold had no deleterious effect on the chondrogenic differentiation process. Further, the scaffolds can also be used as a dermal analog; a differentiated epidermal structure can be obtained by culturing keratinocytes on top of the scaffolds. The new method improves upon the method that was originally developed by and Yannas, et al. 16 and Burke, et al. 49 to use porous dry substrates of collagen-GAG as dermal equivalents. The scaffolds from the new method can also be used in the development of composite cultured skin equivalents 2.

Conclusions

In summary, we describe a simple and rapid centrifugation method to fabricate collagen-GAG scaffolds with various collagen densities. We show that scaffolds with various collagen concentrations have differing properties. In general, increasing the collagen density increases water uptake per volume of the scaffold, leads to smaller pore sizes, and to an increase in compressive and tensile moduli. We further demonstrate the biocompatibility of the concentrated collagen scaffolds by tissue engineering cartilage and cultured skin equivalents in vitro. The tunable properties, as well as the adjustable collagen density which can lead to different degradations rates in vivo, of these scaffolds make them useful for a variety of biomedical applications in regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgements

The research was funded in part by grants from the Whitaker Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (EB006203, HB) and (AR050208, JFW). We thank Prof. Joseph Mansour for the use of the compression testing apparatus and the Department of Macromolecular Science and Engineering at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH for the use of the Instron machine for tensile testing. The FGF-2 was a generous gift from the Biological Resources Branch of the National Cancer Institute. The anti-collagen type X antibody was a gift from Dr. Gary J. Gibson, Breech Research Laboratory, Bone & Joint Center, Henry Ford Hospital & Medical Centers, Detroit, MI.

References

- 1.Glowacki J, Mizuno S. Collagen scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biopolymers. 2008;89(5):338–44. doi: 10.1002/bip.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaglstein WH, Falanga V. Tissue engineering and the development of Apligraf, a human skin equivalent. Clin Ther. 1997;19(5):894–905. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherubino P, Grassi FA, Bulgheroni P, Ronga M. Autologous chondrocyte implantation using a bilayer collagen membrane: a preliminary report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2003;11(1):10–5. doi: 10.1177/230949900301100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Kassaby AW, Retik AB, Yoo JJ, Atala A. Urethral stricture repair with an offthe-shelf collagen matrix. J Urol. 2003;169(1):170–3. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64060-8. discussion 173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodkey WG, Steadman JR, Li ST. A clinical study of collagen meniscus implants to restore the injured meniscus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(367 Suppl):S281–92. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199910001-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Springer IN, Nocini PF, Schlegel KA, De Santis D, Park J, Warnke PH, Terheyden H, Zimmermann R, Chiarini L, Gardner K. Two techniques for the preparation of cell-scaffold constructs suitable for sinus augmentation: steps into clinical application. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(9):2649–56. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2649. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenblatt J, Devereux B, Wallace DG. Injectable collagen as a pH-sensitive hydrogel. Biomaterials. 1994;15(12):985–95. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace DG, Rosenblatt J. Collagen gel systems for sustained delivery and tissue engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55(12):1631–49. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huynh T, Abraham G, Murray J, Brockbank K, Hagen PO, Sullivan S. Remodeling of an acellular collagen graft into a physiologically responsive neovessel. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(11):1083–6. doi: 10.1038/15062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen DC, Lai YL, Lee SY, Hung SL, Chen HL. Osteoblastic response to collagen scaffolds varied in freezing temperature and glutaraldehyde crosslinking. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;80(2):399–409. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duan X, Sheardown H. Dendrimer crosslinked collagen as a corneal tissue engineering scaffold: mechanical properties and corneal epithelial cell interactions. Biomaterials. 2006;27(26):4608–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han B, Jaurequi J, Tang BW, Nimni ME. Proanthocyanidin: a natural crosslinking reagent for stabilizing collagen matrices. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;65(1):118–24. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orban JM, Wilson LB, Kofroth JA, El-Kurdi MS, Maul TM, Vorp DA. Crosslinking of collagen gels by transglutaminase. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;68(4):756–62. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito H, Taguchi T, Aoki H, Murabayashi S, Mitamura Y, Tanaka J, Tateishi T. pH-responsive swelling behavior of collagen gels prepared by novel crosslinkers based on naturally derived di- or tricarboxylic acids. Acta Biomater. 2007;3(1):89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Wachem PB, Plantinga JA, Wissink MJ, Beernink R, Poot AA, Engbers GH, Beugeling T, van Aken WG, Feijen J, van Luyn MJ. In vivo biocompatibility of carbodiimide-crosslinked collagen matrices: Effects of crosslink density, heparin immobilization, and bFGF loading. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;55(3):368–78. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20010605)55:3<368::aid-jbm1025>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yannas IV, Burke JF, Gordon PL, Huang C, Rubenstein RH. Design of an artificial skin. II. Control of chemical composition. J Biomed Mater Res. 1980;14(2):107–32. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820140203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buijtenhuijs P, Buttafoco L, Poot AA, Daamen WF, van Kuppevelt TH, Dijkstra PJ, de Vos RA, Sterk LM, Geelkerken BR, Feijen J. Tissue engineering of blood vessels: characterization of smooth-muscle cells for culturing on collagen-and-elastin-based scaffolds. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2004;39(Pt 2):141–9. doi: 10.1042/BA20030105. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuberka M, Heschel I, Glasmacher B, Rau G. Preparation of collagen scaffolds and their applications in tissue engineering. Biomed Tech (Berl) 2002;471(Suppl 1 Pt):485–7. doi: 10.1515/bmte.2002.47.s1a.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma L, Gao C, Mao Z, Zhou J, Shen J, Hu X, Han C. Collagen/chitosan porous scaffolds with improved biostability for skin tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2003;24(26):4833–41. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasaki N, Odajima S. Stress-strain curve and Young's modulus of a collagen molecule as determined by the X-ray diffraction technique. J Biomech. 1996;29(5):655–8. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Brien FJ, Harley BA, Yannas IV, Gibson L. Influence of freezing rate on pore structure in freeze-dried collagen-GAG scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2004;25(6):1077–86. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00630-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien FJ, Harley BA, Yannas IV, Gibson LJ. The effect of pore size on cell adhesion in collagen-GAG scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2005;26(4):433–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lennon DP, Haynesworth SE, Bruder SP, Jaiswal N, Caplan AI. Human and animal mesenchymal progenitor cells from bone marrow: Identification of serum for optimal selection and proliferation. In Vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology. 1996;32(10):602–611. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrino DA, Arias JL, Caplan AI. A spectrophotometric modification of a sensitive densitometric Safranin O assay for glycosaminoglycans. Biochem Int. 1991;24(3):485–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welter JF, Solchaga LA, Penick KJ. Simplification of aggregate culture of human mesenchymal stem cells as a chondrogenic screening assay. Biotechniques. 2007;42(6):732, 734–7. doi: 10.2144/000112451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penick KJ, Solchaga LA, Welter JF. High-throughput aggregate culture system to assess the chondrogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Biotechniques. 2005;39(5):687–91. doi: 10.2144/000112009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ponticiello MS, Schinagl RM, Kadiyala S, Barry FP. Gelatin-based resorbable sponge as a carrier matrix for human mesenchymal stem cells in cartilage regeneration therapy. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;52(2):246–55. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200011)52:2<246::aid-jbm2>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi H, Han C, Mao Z, Ma L, Gao C. Enhanced angiogenesis in porous collagen-chitosan scaffolds loaded with angiogenin. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14(11):1775–85. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma L, Gao C, Mao Z, Zhou J, Shen J. Enhanced biological stability of collagen porous scaffolds by using amino acids as novel cross-linking bridges. Biomaterials. 2004;25(15):2997–3004. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeong WY, Chua CK, Leong KF, Chandrasekaran M, Lee MW. Comparison of drying methods in the fabrication of collagen scaffold via indirect rapid prototyping. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2007;82(1):260–6. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veronda DR, Westmann RA. Mechanical characterization of skin-finite deformations. J Biomech. 1970;3(1):111–24. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(70)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harley BA, Leung JH, Silva EC, Gibson LJ. Mechanical characterization of collagen-glycosaminoglycan scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2007;3(4):463–74. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papini S, Cecchetti D, Campani D, Fitzgerald W, Grivel JC, Chen S, Margolis L, Revoltella RP. Isolation and clonal analysis of human epidermal keratinocyte stem cells in long-term culture. Stem Cells. 2003;21(4):481–94. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-4-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yannas IV, Burke JF. Design of an artificial skin. I. Basic design principles. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 1980;14(1):65–81. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820140108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medalie DA, Eming SA, Tompkins RG, Yarmush ML, Krueger GG, Morgan JR. Evaluation of human skin reconstituted from composite grafts of cultured keratinocytes and human acellular dermis transplanted to athymic mice. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107(1):121–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12298363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haynesworth SE, Goshima J, Goldberg VM, Caplan AI. Characterization of cells with osteogenic potential from human marrow. Bone. 1992;13(1):81–8. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(92)90364-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lennon DP, Haynesworth SE, Young RG, Dennis JE, Caplan AI. A chemically defined medium supports in vitro proliferation and maintains the osteochondral potential of rat marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Cell Res. 1995;219(1):211–22. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solchaga L, Goldberg VM, Mishra R, Caplan A, Welter J. FGF-2 modifies the gene expression profile of bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells. Transactions of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2004;29:777. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solchaga LA, Welter JF, Lennon DP, Caplan AI. Generation of pluripotent stem cells and their differentiation to the chondrocytic phenotype. Methods in Molecular Medicine. 2004;100:53–68. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-810-2:053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnstone B, Hering TM, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM, Yoo JU. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Experimental Cell Research. 1998;238(1):265–272. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solchaga L, Tognana E, Penick K, Baskaran H, Goldberg V, Caplan A, Welter J. A rapid seeding technique for the assembly of large cell/scaffold composite constructs. Tissue Engineering. 2006;12(7):1851–1863. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Welter JF, Solchaga L, Penick K, Baskaran H, Goldberg VM, Caplan AI, Berilla J. A modular bioreactor system for cartilage tissue engineering. Transactions of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2005;30(2):1771. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solchaga L, Penick K, Welter J. A “manual” mosaicking approach to generating large, high-resolution digital images of histological sections. Proceedings of the Royal Microscopical Society. 2004;39(4):313–320. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banks-Schlegel S, Green H. Involucrin synthesis and tissue assembly by keratinocytes in natural and cultured human epithelia. J Cell Biol. 1981;90(3):732–7. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.3.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garg AK, Berg RA, Silver FH, Garg HG. Effect of proteoglycans on type I collagen fibre formation. Biomaterials. 1989;10(6):413–9. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(89)90133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nomura S, Hiltner A, Lando JB, Baer E. Interaction of water with native collagen. Biopolymers. 1977;16(2):231–46. doi: 10.1002/bip.1977.360160202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shepherd DE, Seedhom BB. The ‘instantaneous’ compressive modulus of human articular cartilage in joints of the lower limb. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38(2):124–32. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edwards C, Marks R. Evaluation of biomechanical properties of human skin. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13(4):375–80. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(95)00078-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burke JF, Yannas IV, Quinby WC, Jr., Bondoc CC, Jung WK. Successful use of a physiologically acceptable artificial skin in the treatment of extensive burn injury. Ann Surg. 1981;194(4):413–28. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198110000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]