Abstract

GsMTx4, a peptide inhibitor for mechanosensitive ion channels (MSCs), promoted neurite outgrowth from PC12 cells in the presence of NGF in a dose-dependent manner between 5 and 100 μM peptide. Enhanced neurite growth required >12 h of peptide exposure in cells grown with NGF. Adsorption of GsMTx4 to serum proteins in the media lowered the free peptide concentration of 100 μM to a free concentration of 5 μM, a concentration shown to completely inhibit MSCs in the patch clamp assay. Outside-out patches from PC12 cells grown in NGF had mechanically activated cation channels that were reversibly inhibited by GsMTx4. These results are similar to those observed by Gomez and co-workers [4] in Xenopus spinal cord. The inhibition of mechanosensitive channels by GsMTx4 may be a useful approach to accelerate regeneration of neurons in neurodegenerative diseases and spinal cord injury.

Keywords: Neurite outgrowth, Mechanical channels, GsMTx4, Peptide inhibitor, NGF, PC12

Neurite outgrowth from endogenous or transplanted cells is important for restoring function after injury or from neurodegenerative diseases. There are many factors that initiate neurite extension, but neurotrophic protein factors such as NGF, BDNF, and GDNF are critical components for survival and regeneration [5,8,13]. However, these factors alone are insufficient for adequate recovery, suggesting that addition of other compounds known to accelerate neurite extension could improve therapy. Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s, and spinal cord injury would benefit from an approach that both stimulates and accelerates neural regeneration.

Recent work by Gomez and co-workers [4] showed that inhibition of MSCs by GsMTx4 [1] stimulates neurite outgrowth in Xenopus spinal cord and has obvious implications for the regeneration of mammalian neurons. They showed that local calcium levels control neurite growth, and that calcium influx through MSCs is an important modulator.

GsMTx4 was originally isolated from the venom of the tarantula Grammostola spatulata (now genus Rosea) and is the only known specific pharmacological agent for mechanosensitive ion channels [6,11]. Structurally, the peptide is a member of the inhibitory cysteine knot (ICK) peptide superfamily [7] with 34 amino acids and three disulfide bonds in a compact structure with a net charge of +5 [6]. The peptide inhibits MSCs by acting as a gating modifier that decreases their sensitivity to membrane tension. Remarkably, the mechanism of action is not a lock and key since the D-enantiomer is equally active [12]. GsMTx4 binds to the outer monolayer of the membrane and when it is within a Debye length of the channel pore, pre-stresses the channel to favour the closed state. GsMTx4 binds to phospholipids [9,10] and since it has a charge of +5, it binds better to anionic than cationic or zwitterionic lipids, with its internal tryptophan reaching ~ 0.8 nm from the midline.

Following the observations of Gomez’s lab [4], we examined how GsMTx4 would affect neurite outgrowth in mammalian neurons using the rat pheochromocytoma cell line PC12 as a model. When the cells were grown with nerve growth factor (NGF), GsMTx4 potentiated neurite outgrowth. GsMTx4 did not have this effect without NGF illustrating a multifactorial pathway for neurite growth and raising the potential for a novel clinical intervention.

PC12 cells, purchased from ATCC, were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2/95% air incubator in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10 mM Hepes buffer (MediaTech, Herndon, VA) at 37 °C. Cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at 4 × 104 cells per well and allowed to adhere overnight before treatment. For electrophysiology experiments, cells were plated on 25 mm glass cover slips coated with poly-L-lysine and were used after 24 h.

NGF (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was reconstituted with phosphate buffered saline containing 1–2% bovine serum albumin at 100 μg/ml. In all experiments, NGF stock was added to final concentration of 50 ng/ml as indicated. GsMTx4 was prepared as described [6] and reconstituted at 50–100 μM in culture media. In pilot experiments, cells were treated with either 5 μM GsMTx4, 50 ng/ml NGF, or left untreated and compared qualitatively at 1, 6, 24 and 48 h for neurite initiation. Negative results from this pilot prompted us to investigate a synergistic effect between NGF and GsMTx4.

To establish a baseline, we treated cells with 10 or 50 μM GsMTx4 or NGF alone. Synergistic effects were evaluated by comparison of PC12 cells treated with NGF alone, or a combination of NGF and GsMTx4 in the range of 5 nM to 100 μM.

Since the lowest effective concentration of GsMTx4 likely fell between 5 and 50 μM, we compared cells treated with 10 μM GsMTx4 and NGF to cells treated with NGF alone. To determine the exposure time required for GsMTx4 to enhance neurite growth, cells were treated with NGF alone or in combination with 10 μM GsMTx4; the peptide was removed by replacing peptide media with media containing NGF alone at 1, 6, or 12 h. To assess the maximal effect, cells were treated with peptide and NGF for the full 48 h. The drug samples were double blinded to avoid bias in the analysis.

Forty-eight hours after treatment, cells were viewed with an inverted phase contrast microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) and photographed (Spot, version 4.6, Diagnostic Imaging, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI). Three images were taken from randomly selected areas in each of at least four wells for each treatment and we only took images where there were more than 10 cells in a field. A minimum of 250 cells were evaluated in each experiment. To quantify neurite initiation, the percentage of neurite bearing cells was calculated for each image as the ratio of neurite bearing cells to the total number of cells. A cell was considered neurite bearing if it had at least one process longer than the diameter of the cell from which it arose. To quantify neurite extension, the longest neurite on each neurite bearing cell was measured using Image J (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland) from which we calculated mean values.

GraphPad Prism 5.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used to perform the statistical analysis and create graphs. Results were compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests.

To measure the amount of free GsMTx4 in serum containing media, GsMTx4 was added to 250 μL media with or without serum to create a total concentration of 50 μM. The solution was allowed to incubate for 10 min, transferred to micro concentrators (Millipore, Bellirica, MA, 10,000 MW cutoff), and centrifuged at 5000 rpm. Samples from both the concentrate and the filtrate were analyzed by reverse phase HPLC according to previously published protocols [6].

We used an Axopatch 200B (Axon Instruments, Farmingdale, NY) patch clamp amplifier to measure channel currents. Data were collected digitally (National Instruments, Austin) using QUBIO software (www.qub.buffalo.edu). Currents were sampled at 10 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz through a four-pole Bessel filter. All potentials are defined with respect to the extracellular surface.

Electrodes were pulled on a HEKA pipette puller (PIP5), painted with Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning Corp, Midland), and fire polished. Electrodes were filled with saline (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 EGTA and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. Electrode resistances ranged from 3 to 8 MΩ. Bath saline contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2 and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. Pressure pulses were generated with a high-speed pressure clamp (ALA Scientific, Farmingdale, NY). GsMTx4 was perfused over the patch, at the indicated concentration, using an ALA Scientific perfusion system. Offline data analysis was done with QUB software (www.qub.buffalo.edu). Data were averaged for a minimum of 5 pressure pulses.

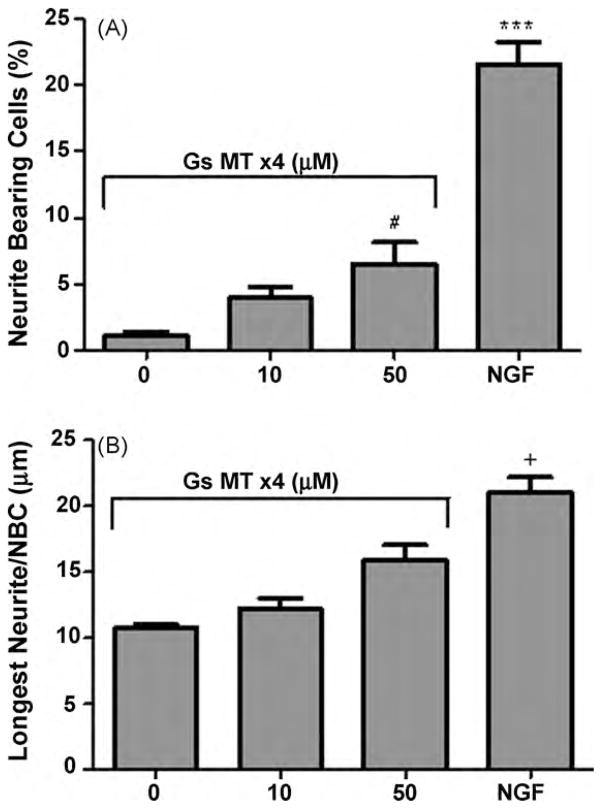

To establish a baseline response, we first compared untreated cells with cells incubated with either GsMTx4 (10 or 50 μM) or NGF (50 ng/ml). Fig. 1 summarizes those results. As expected, NGF increased neurite initiation significantly. The percentage of neurite bearing cells increased from ~ 1% to ~ 20% and length of the longest neurite per NBC increased from approximately 10 μm to 20 μm. Cells treated with GsMTx4 had a less dramatic, but significant response of neurite initiation at 50 μM. However, we observed little difference in neurite length.

Fig. 1.

The effect of GsMTx4 on PC12 cells at the indicated concentrations is compared with NGF 50 ng/ml after 48 h. Panel A shows the percentage of neurite bearing cells (NBC) and Panel B shows the mean value of the longest neurite of those cells. GsMTx4 alone is significantly less effective than NGF in both processes; #p < 0.05 vs 0 μM GsMTx4; +p < 0.05 vs 10 μM GsMTx4; ***p < 0.001 vs all other treatments.

We next measured the effect of NGF stimulated cells with increasing concentrations of GsMTx4 (Fig. 2). For concentrations of peptide below 5 μM there was no observable effect, but higher concentrations produced a significant response. At the highest concentration of GsMTx4 (100 μM) we used, the percentage of neurite bearing cells doubled. Representative images of cells in the presence and absence of GsMTx4 are shown in Fig. 3. There are more neurites with NGF and 50 μM GsMTx4 (Fig. 3C) when compared to either NGF alone (Fig. 3A) or 5 μM GsMTx4 with NGF (Fig. 3B). While a GsMTx4 concentration of 10 μM was sufficient to increase the percentage of neurite bearing cells significantly (Fig. 4A), no corresponding increase in neurite length was seen (Fig 4B). At the highest doses of peptide (100 μM), we observed a significant increase in neurite length (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Dose–response behavior of GsMTx4 with NGF (50 ng/ml) on the percentage of neurite bearing cells. Cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of peptide for 48 h before analysis. ##p < 0.01 vs 5 μM; ***p < 0.001 vs 5 μM and below.

Fig. 3.

Images of PC12 cells after a 48 h treatment. Cells were plated at 4 × 104 in a 24-well plate and treated with either (A) 50 ng/ml NGF alone, (B) NGF and 5 μM GsMTx4 or (C) NGF and 50 μM GsMTx4. Cells treated with NGF alone show typical neurite outgrowth. The combination of NGF and GsMTx4 produced more neurites than NGF alone, and 50 μM was more effective that 5 μM.

Fig. 4.

Panel A shows that GsMTx4 (10 μM) worked synergistically with NGF (50 ng/ml) to produce a statistically significant increase of neurite bearing cells over NGF alone; **p < 0.01 vs GsMTx4; ***p < 0.001 vs GsMTx4 and NGF. Panel B demonstrates that no change in mean length of the longest neurites was observed; *p < 0.05 vs GsMTx4; **p < 0.01 vs GsMTx4.

We determined that the peptide binds to serum proteins that results in a free concentration well below the concentration of added peptide and explains the need for a high concentration of peptide for neurite growth. We measured the partition coefficient using a membrane filtration assay with a molecular weight cutoff of 10,000 Da to separate free GsMTx4. (Note: for precision, the concentrations used for this assay were approximately 20-fold greater than that used in the patch clamp for inhibition of mechanical channels in saline [11].) Fig. 5 shows that saline media retains more in the concentrate (70%) and less in the supernatant (30%), a small effect on the distribution of peptide. With the addition of 10% serum, (v/v) the free concentration of peptide was reduced by approximately 20-fold. Thus, in culture media, a mean concentration of 100 μM GsMTx4 has a free concentration of ~5 μM, well over the Kd of ~500 nM for MSCs.

Fig. 5.

Free concentration of GsMTx4 in saline media or media containing 10% serum. The solutions were passed through a membrane with 10,000 Da cutoff and the filtrate and concentrate were analyzed by reverse phase HPLC. For each pair, the dark bar refers to concentrate and the light bar is the filtrate.

To determine the incubation time required for the peptide to enhance NGF stimulated growth, cells were incubated with GsMTx4 at 10 μM, and NGF. At the indicated times, the solution was replaced by media containing only NGF (Fig. 6). Each dish was analyzed after 48 h. We observed a slight increase in neurite bearing cells with 12 h exposures, which was not significant. By 48 h the difference was significant, indicating that 24 (+12) hours of exposure to GsMTx4 is required to cause sustained neurite outgrowth.

Fig. 6.

Time required for GsMTx4 to increase neurite growth. GsMTx4 (10 μM) was incubated in the presence of NGF (50 ng/ml) for the indicated times. The peptide was washed out by replacing the peptide media with media containing NGF alone. At 48 h cells were assessed for neurite initiation (A) and length of the longest neurite/NBC (B). #p < 0.05 vs 1 h; +p < 0.05 vs 6 h; ***p < 0.001 vs NGF.

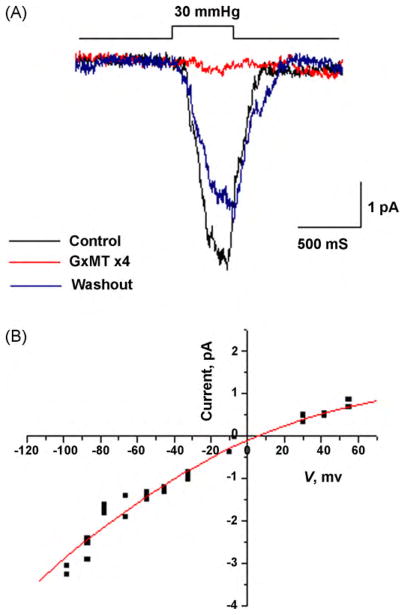

Patch clamp experiments showed the presence of stretch-activated currents in PC12 cells after NGF treatment and that they were inhibited by GsMTx4 (Fig. 7A). In a saline bath, 1.5 μM GsMTx4 inhibited more than 95% of the current and washout with bath solution returned the patch to near full activity. The I/V relationship for these currents reversed near 0 mV (Fig. 7B). Selectivity was determined on inside-out patches using sodium chloride in the pipette with perfusion of sodium HEPES on the intracellular side. Reversal of current was consistent with a non-selective cation channel and not a chloride channel.

Fig. 7.

GsMTx4 peptide (1.5 μM) inhibits stretch-activated currents from PC12 cells treated with NGF (100 ng/ml) for 48 h (A). Outside-out patches (−60 mv) were stimulated with the indicated pressure pulse and produced the currents shown in black (A). Perfusion with GsMTx4 (red trace), was reversible with washout (blue trace). Results are an average of 5–10 pulses for each condition tested. The IV curve shown in (B) was derived from the amplitude response from single channel with pressure pulses. Reversal of current was near 0 mV expected for non-selective cation channels. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

In frogs, neurite outgrowth is potentiated by inhibiting stretch-activated channels with GsMTx4 [3]. When Xenopus spinal cords were treated with GsMTx4 [4], neuronal outgrowth was observed in the absence of any other stimulating factors such as NGF. The effect was traced to the inhibition of calcium influx through non-selective cation channels in the growth cone. The current work extends those results to a mammalian neuronal model. However, while GsMTx4 could potentiate neurite extension in the presence of NGF, it only had a small and unsustainable effect when used alone and compared to NGF or Angiopoietin-1 [2].

Cells treated with 50 ng/ml NGF with 10 μM or greater of GsMTx4 for 48 h produced a synergistic effect so that 100 μM GsMTx4 doubled neurite initiation (Fig. 2). The high concentration of GsMTx4 required to achieve maximal response was well above that required for inhibition of MSCs, although other substances tested for neurite extension effect have been used at these concentrations [15]. However, as we showed in Fig. 6, the free drug concentration in media was only about 5% of the total. Adjusted for serum binding, the Kd for neurite extension was comparable to the Kd observed using saline in patch clamp experiments.

After treatment with NGF, PC12 cells have MSCs that respond to the GsMTx4 in a reversible manner at concentrations used for inhibiting mechanical channels in other cell lines [11]. How do mechanical channels participate in neurite growth extension? Wei et al. [14] observed that during cell migration (neurite extension), calcium transients at the leading edge were increased by mechanical stimulation. When a cell encountered a barrier, the migrating cell would retract and pull back on adhesive attachment sites, increasing membrane tension, opening MSCs and increasing Ca2+ influx. Calcium appears to stabilize the filopodium setting the stage for the cell to pair with a pre-synaptic partner. Inhibition of these channels by GsMTx4 would decrease the mechanically induced Ca2+ influx preventing filopodia stabilization and allowing continued migration and neurite extension.

We have demonstrated that GsMTx4 at a free concentration greater than 0.5 μM works synergistically with NGF to increase neurite initiation for PC12 cells. Stimulation of neurite growth by GsMTx4 in concert with other growth factors may prove a useful approach for neural regeneration in spinal cord injury and neurodegenerative diseases.

References

- 1.Bowman CL, Gottlieb PA, Suchyna TM, Murphy YK, Sachs F. Mechanosensitive ion channels and the peptide inhibitor GsMTx-4: history, properties, mechanisms and pharmacology. Toxicon. 2007;49:249–270. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, Fu W, Tung CE, Ward NL. Angiopoietin-1 induces neurite outgrowth of PC12 cells in a Tie2-independent, beta1-integrin-dependent manner. Neurosci Res. 2009;64:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottlieb PA, Suchyna TM, Ostrow LW, Sachs F. Mechanosensitive ion channels as drug targets. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2004;3:287–295. doi: 10.2174/1568007043337283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacques-Fricke BT, Seow Y, Gottlieb PA, Sachs F, Gomez TM. Ca2+ influx through mechanosensitive channels inhibits neurite outgrowth in opposition to other influx pathways and release from intracellular stores. J Neurosci. 2006;26 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0675-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu P, Jones LL, Tuszynski MH. Axon regeneration through scars and into sites of chronic spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2007;203:8–21. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostrow KL, Mammoser A, Suchyna T, Sachs F, Oswald R, Kubo S, Chino N, Gottlieb PA. cDNA sequence and in vitro folding of GsMTx4, a specific peptide inhibitor of mechanosensitive channels. Toxicon. 2003;42:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(03)00141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oswald RE, Suchyna TM, McFeeters R, Gottlieb P, Sachs F. Solution structure of peptide toxins that block mechanosensitive ion channels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34443–34450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson AL, Nutt JG. Treatment of Parkinson’s disease with trophic factors. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:270–280. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Posokhov YO, Gottlieb PA, Ladokhin AS. Quenching-enhanced fluorescence titration protocol for accurate determination of free energy of membrane binding. Anal Biochem. 2007;362:290–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Posokhov YO, Gottlieb PA, Morales MJ, Sachs F, Ladokhin AS. Is lipid bilayer binding a common property of inhibitor cysteine knot ion channel blockers? Biophys J. 2007;93:L20–22. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.112375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suchyna TM, Johnson JH, Hamer K, Leykam JF, Gage DA, Clemo HF, Baumgarten CM, Sachs F. Identification of a peptide toxin from Grammostola spatulata spider venom that blocks cation-selective stretch-activated channels. J Gen Physiol. 2000;115:583–598. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.5.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suchyna TM, Tape SE, Koeppe RE, 2nd, Andersen OS, Sachs F, Gottlieb PA. Bilayer-dependent inhibition of mechanosensitive channels by neuroactive peptide enantiomers. Nature. 2004;430:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature02743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuszynski MH. Nerve growth factor gene therapy in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21:179–189. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318068d6d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei C, Wang X, Chen M, Ouyang K, Song LS, Cheng H. Calcium flickers steer cell migration. Nature. 2009;457:901–905. doi: 10.1038/nature07577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang YJ, Lee HJ, Choi DH, Huang HS, Lim SC, Lee MK. Effect of scoparone on neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Neurosci Lett. 2008;440:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]