The phloem of higher plants transports the products of photosynthesis and other nutrients over long distances from leaves to sink tissues, such as fruits, tubers, and roots, where they are used in growth or storage. The primary conducting cells of the phloem are the enucleate sieve elements, which are intimately connected to their neighboring companion cells. The sieve elements are joined at their ends by perforated cell walls called sieve plates to form sieve tubes, through which solutes flow as a river of nutrient solution. Many recent studies have focused on the fascinating discovery that the phloem functions not only to transport low-molecular–weight solutes but also macromolecules, including proteins and RNAs. The conducting phloem has been likened to the plant’s “superhighway” (1), delivering a broad range of defense and developmental signals to distant parts of the plant, including the flowering signal “florigen” and the signal for tuberization in potatoes (2, 3). These concepts form the foundation of a unique and exciting field in developmental biology.

As a tissue, the phloem is difficult to study because it is under extremely high pressure as a result of the elevated concentrations of solutes it carries. Severing the phloem results in massive disruption of sieve element contents and surging of the displaced materials onto the sieve plate. As a result, the sieve plate pores plug, making it difficult to sample the phloem and analyze the molecules it conducts. This has challenged researchers to look for unique sampling methods that do not disturb the delicate sieve elements. One way of doing this is to use phloem-feeding insects, such as aphids, that “tap” the contents of the conducting phloem. By severing the aphid stylet with a laser (laser “stylectomy”), it is possible to collect and analyze nanoliter samples of sap derived directly from the conducting sieve tubes. However, not all aphid/plant combinations yield sap, and the collection method is both difficult and time-consuming. A second approach is to use plant species in which the phloem “bleeds,” that is, releases sieve element contents after the phloem has been severed. The Cucurbitaceae (cucurbits) contains several members, including pumpkin, melon, and cucumber, that exude copious amounts of phloem sap after cutting the stem. The ease with which phloem sap can be collected from these species has made them a popular choice in studies of phloem transport and in determining the composition of the conducting sieve elements. A common assumption made in these studies is that phloem sap represents the contents of the vascular (conducting) phloem and, therefore, that the molecules identified in sap are representative of those in long-distance transit.

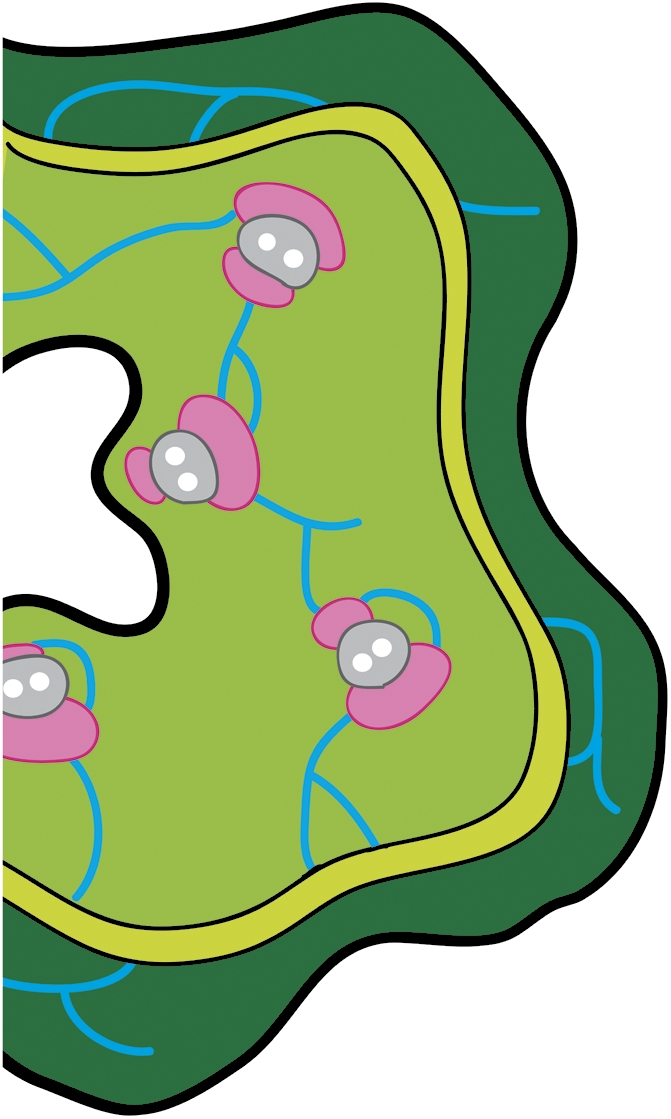

In PNAS, Zhang et al. (4) show that the exuding phloem sap of cucurbits is derived from the so-called “extrafascicular” phloem and not the vascular (fascicular) conducting phloem of the vascular bundles. The fact that the cucurbits have two types of phloem was recognized, anatomically, over two centuries ago (5, 6). The fascicular phloem is restricted to either side of the xylem in the main vascular bundles, whereas the extrafascicular phloem forms an anastomosing network that interconnects the vascular bundles laterally in the stem and petiole (Fig. 1). Now, using video microscopy and phloem-labeling techniques, Zhang et al. (4) show that the fascicular phloem quickly becomes blocked when the stem is cut. In contrast, the extrafascicular phloem bleeds profusely for many minutes, indicating that it does not have the “normal” sealing systems found in other types of phloem. Their data point to the fact that most studies of the metabolite, protein, and RNA composition of the cucurbit phloem probably relate to the contents of the relatively minor extrafascicular sieve elements and not the main conducting phloem elements of the stem. Their results also explain a long-standing conundrum, namely, why the sugar content of cucurbit sap is about 30-fold less than the requirements of photosynthate delivery. When they looked in detail at the fascicular phloem using tissue dissection and microsampling techniques, they found that the fascicular sieve elements do indeed contain up to 1 M sugars, which is sufficient for fruit growth, whereas the extrafascicular phloem contains only low (millimolar) levels of sugars. Significantly, they also show that the protein composition of the divergent phloem systems differs markedly.

Fig. 1.

Transverse section of a C. maxima stem (redrawn from ref. 7). The fascicular phloem (pink) occurs on either side of the xylem (gray) in the main vascular bundles of the stem. The extrafascicular phloem (blue) forms an anastomosing network in the pith (pale green) and also in the cortex (dark green). A detailed description of cucurbit anatomy is provided by Crafts (6).

Why does the extrafascicular phloem not seal immediately to prevent release of sieve element contents? In most plants, wound sealing of the sieve plate pores is achieved by deposition of callose (a wound carbohydrate present around the sieve plate pores) as well as by the surge of cell contents, mostly filamentous phloem proteins (P-proteins), into the pores (7). Clues as to why extrafascicular sieve elements do not block came from ultrastructural studies in the 1960s (reviewed in ref. 8) showing that the sieve plates of the extrafascicular sieve elements are characterized by a relative lack of callose. Kempers et al. (8) subsequently made use of this property to deliver macromolecules into the cut extrafascicular phloem of Cucurbita maxima. They found that simply by dipping the cut end of the stem into fluorescent dextrans, macromolecules were taken up and transported along the extrafascicular sieve elements. In the study by Zhang et al. (4), P-proteins were found in the extrafascicular phloem; however, surprisingly, the fascicular phloem had very low levels of P-proteins, and yet this phloem blocks almost instantaneously on wounding. They speculate that some of the other major proteins identified in the fascicular phloem may perform the wound-sealing functions of the fascicular phloem.

What then is the function of the enigmatic extrafascicular phloem? It does not appear to be involved in loading sugars into the phloem of source leaves because it is absent from the minor veins of leaves, the main sites of phloem loading. Zhang et al. (4) speculate that it may be involved in plant defense against pathogens. They found the extrafascicular phloem sap to contain abundant amino acids and a wide range of unidentified secondary metabolites. Because the extrafascicular phloem is common near the epidermis and throughout the stem, it may provide strategic rings of defense against pathogens. In this case, having a phloem system that bleeds profusely to release defense compounds may inhibit pathogens and protect the sugar-rich fascicular phloem from insect and fungal attack.

A final question is whether the cucurbits are unique in evolving two functionally different transport systems. As pointed out by Zhang et al. (4), this runs contrary to the widely held belief that the phloem of higher plants represents a unified conduit for the translocation of metabolites. It remains to be shown whether the extreme division of labor shown by the cucurbit phloem systems will prove to manifest itself more subtly in the phloem of other higher plants. However, the recent release of the complete cucumber genome sequence (9) will provide a platform for further interesting studies on the unusual phloem of the Cucurbitaceae. Although transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome data on cucurbit exudate are undoubtedly important in the study of the extrafascicular phloem and its functions, for analysis of sap involved in long-distant transit from source to sink tissues, it may be wise to use other systems in which exudate appears to come directly from the moving translocation stream (10).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jessica Fitzgibbon for drawing Fig. 1.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 13532.

References

- 1.Jorgensen RA, Atkinson RG, Forster RLS, Lucas WJ. An RNA-based information superhighway in plants. Science. 1998;279:1486–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinant S, Lemoine R. The phloem pathway: New issues and old debates. C R Biol. 2010;333:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kragler F. RNA in the phloem: A crisis or a return on investment? Plant Sci. 2010;178:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang B, Tolstikov V, Turnbull C, Hicks LM, Fiehn O. Divergent metabolome and proteome suggest functional independence of dual phloem transport systems in cucurbits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13532–13537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910558107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer A. Das Siebröhrensystem von Cucurbita. Botanica Acta. 1883;1:276–279. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crafts AS. Phloem anatomy, exudation and transport of organic nutrients in cucurbits. Plant Physiol. 1932;7:i4–i225. doi: 10.1104/pp.7.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oparka KJ, Santa Cruz S. The great escape: Phloem transport and unloading of macromolecules. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 2000;51:323–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kempers R, Prior DAM, van Bel AJE, Oparka KJ. Plasmodesmata between sieve element and companion cell of extrafascicular stem phloem of Cucurbita maxima permit passage of 3 kDa fluorescent-probes. Plant J. 1993;4:567–575. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang S, et al. The genome of the cucumber, Cucumis sativus L. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1275–1281. doi: 10.1038/ng.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turgeon R, Wolf S. Phloem transport: Cellular pathways and molecular trafficking. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:207–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]