Abstract

Clostridium difficile toxins A and B are members of an important class of virulence factors known as large clostridial toxins (LCTs). Toxin action involves four major steps: receptor-mediated endocytosis, translocation of a catalytic glucosyltransferase domain across the membrane, release of the enzymatic moiety by autoproteolytic processing, and a glucosyltransferase-dependent inactivation of Rho family proteins. We have imaged toxin A (TcdA) and toxin B (TcdB) holotoxins by negative stain electron microscopy to show that these molecules are similar in structure. We then determined a 3D structure for TcdA and mapped the organization of its functional domains. The molecule has a “pincher-like” head corresponding to the delivery domain and two tails, long and short, corresponding to the receptor-binding and glucosyltransferase domains, respectively. A second structure, obtained at the acidic pH of an endosome, reveals a significant structural change in the delivery and glucosyltransferase domains, and thus provides a framework for understanding the molecular mechanism of LCT cellular intoxication.

Keywords: bacterial toxin, electron microscopy, pore formation

Clostridium difficile is the primary causative agent of hospital-acquired diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis (1, 2). Virulence is associated with the activity of two large exotoxins, TcdA and TcdB (308 and 270 kDa, respectively) (1–3). The proteins are homologous glucosyltransferases that inactivate small GTPases of the Rho/Rac family. The resulting disruption in signaling causes a loss of cell–cell junctions, dysregulation of the actin cytoskeleton, and apoptosis (4, 5).

The action of TcdA and TcdB on mammalian target cells depends on a multistep mechanism of receptor-mediated endocytosis, membrane translocation, autoproteolytic processing, and monoglucosylation. Many of these functional activities have been ascribed to discrete regions within the primary sequence, suggesting that the toxins will adopt multimodular 3D structures (Fig. 1A). The toxins first bind the surface of the target cell through a highly repetitive C-terminal domain (6, 7) and are internalized by endocytosis (8, 9). The low pH of the endosome is proposed to induce structural changes that lead to pore formation and translocation of the N terminus across the membrane (9–11). The central regions of these toxins have been dubbed “delivery” domains on the basis of the presence of a hydrophobic sequence that could adopt a transmembrane structure during pore formation (12). The N-terminal glucosyltransferase domains are translocated and released into the host cell cytosol, where they can target small GTPases such as RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 (13, 14). Release is triggered by an autoproteolytic processing event in which eukaryotic inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6) binds the domain adjacent to the monoglucosyltransferase domain and activates an intramolecular cleavage reaction (15, 16).

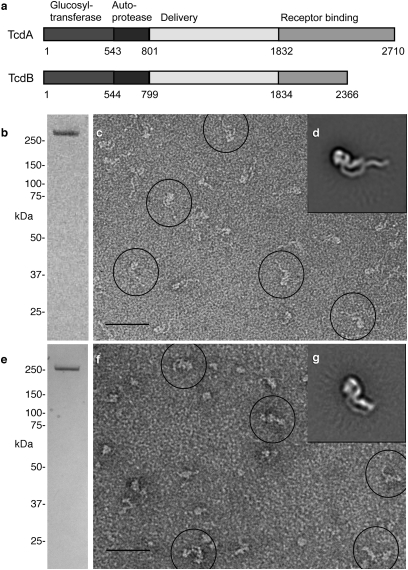

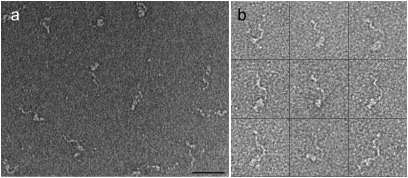

Fig. 1.

Purification and characterization of TcdA and TcdB. (A) The proposed domain organization for TcdA and TcdB. The numbers are for amino acids that mark domain boundaries. (B) SDS/PAGE of purified TcdA, visualized by Coomassie staining. (C) Typical electron micrograph showing TcdA particles in negative stain. A few of the particles are circled in black. (Scale bar, 500 Å.) (D) Representative class average of TcdA particles (4,956) selected from images of untilted specimens in negative stain. Side length of panel is 57.3 nm. (E) SDS/PAGE of TcdB, visualized by Coomassie staining. (F) Electron micrograph of TcdB in negative stain, with a few particles circled in black. (Scale bar, 500 Å.) (G) Class average of 915 TcdB particles in negative stain. Side length of panel is 51.1 nm.

TcdA and TcdB belong to a family of large clostridial toxins (LCTs) that also includes the hemorrhagic and lethal toxins of C. sordellii and the α-toxin from C. novyi. LCTs are important virulence factors, but with the exception of an analysis of TcdB by small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) (17), the holotoxin structures of these molecules have not been characterized. We have imaged TcdA and TcdB using EM and show that they share many similar structural features. We have determined a 3D structure of the TcdA holotoxin at neutral pH by negative stain EM and experimentally mapped three of the four functional domains to discrete regions within the density. These data allow us to evaluate structural models of the TcdA receptor-binding domain (6, 18), the TcdA autoprotease domain (19), and the TcdB glucosyltransferase domain (20) within the architecture of the holotoxin. In addition to the analysis at neutral pH, we present images of TcdA after autoprocessing and after exposure to acidic pH. A 3D structure at low pH suggests that the conformational changes required for translocation of the glucosyltransferase domain into the host cytosol will be significant. Because members of the LCT family are similar in many aspects of sequence and function, these structures of TcdA at neutral and acidic pH provide a framework for understanding the molecular mechanism of cellular intoxication for all members of the LCT family.

Results

Visualization of TcdA and TcdB by Negative Stain EM.

TcdA was purified from C. difficile culture supernatant (Fig. 1B) and shown to be active in a cell-rounding assay (Fig. S1B). Toxin was adsorbed to carbon-coated glow-discharged grids and stained with uranyl formate. Negative stain EM revealed homogeneous particles with a nonsymmetric shape and an elongated “tail” (Fig. 1C). Image pairs of grids containing negatively stained TcdA were recorded at tilt angles of 60° and 0°. A total of 7,396 particles were selected, and images of the untilted specimens were classified into 12 class averages. These class averages revealed that although essentially all TcdA particles adsorbed to the carbon grid in the same orientation, there was some variation in the ability to resolve the elongated “tail” (Fig. S2A). From the 12 classes we selected one that represented a well-resolved TcdA particle, one that represented a TcdA particle with poorly resolved “tail”, and one poorly resolved image (Fig. S2A, marked with a “*”) and used them as references for another cycle of multireference alignment (Fig. S2B). The largest of the three resulting classes (4,956 particles; Fig. 1D and Fig. S2B, marked with a “*”) showed a TcdA particle with many clear structural features (Fig. 1D). The TcdB holotoxin was also purified (Fig. 1E) and shown to be active in a cell-rounding assay (Fig. S1C). Although negative stain EM revealed a more heterogeneous field of particles than seen with TcdA (compare Fig. 1 C and F), the classification of 2,133 particles into 10 class averages revealed a number of classes that had similar structural features as observed in the TcdA alignment (Fig. S2D, classes 1 and 5). To improve the alignment we selected four classes as references for a round of multireference alignment (Fig. S2D, marked with a “*”). The largest of the four resulting classes (915 particles; Fig. 1G and Fig. S2E) showed a TcdB molecule with a well-resolved globular “head” domain connected to two extended tails, structural features that are very similar to that of TcdA (Fig. 1D). Although TcdA and TcdB are clearly structurally similar, the TcdA sample was more homogenous and a better candidate for structural characterization. For this reason further 3D analysis was done using TcdA.

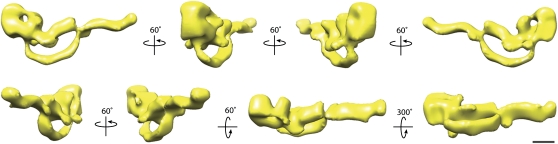

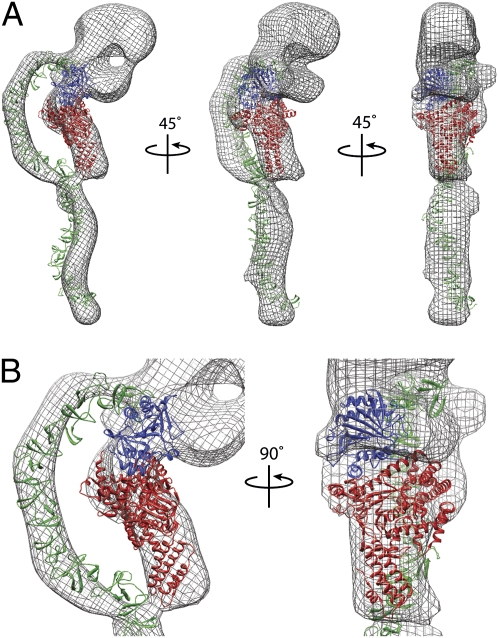

A 3D reconstruction of TcdA was generated using the random conical tilt approach (21) and is presented in Fig. 2 and Movie S1. The Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve calculated from our final density map suggests a resolution of ≈25 Å on the basis of the FSC = 0.5 criterion (22) (Fig. S2C). The face view of the 3D density map shows structural features very similar to those seen in the projection average (compare upper left panel in Fig. 2 with Fig. 1D), suggesting that the 3D reconstruction was successful. The 3D density map of TcdA adopts an elongated, asymmetric structure that is ≈310 Å × ≈150 Å × 90 Å in dimension. The structure contains three prominent features: a “head” domain, a long kinked “tail,” and a short inner “tail”. The head, ≈90 Å × 90 Å × 60 Å in size, seems to contain two globular “pincher-like” domains that are connected by a small density at the top of the head, thus creating a small channel that is ≈20 Å wide and 90 Å deep. Emanating from the head domain are two tails. A long kinked tail extends from the bottom of the larger of the two “pincher” domains and stretches ≈270 Å in an undulating curve. A second tail domain connects from the smaller of the two “pincher” domains, extending ≈100 Å before making contact with the longer kinked tail domain.

Fig. 2.

Random conical tilt reconstruction of TcdA in negative stain. 3D reconstruction of TcdA filtered to 25 Å. The structure is rotated about the vertical axis in 60° steps or about the horizontal axis by 60° or 300° steps (in reference to the top left structure), as indicated by arrows. TcdA has an elongated shape with three distinct domains: a head domain, a long kinked tail, and a shorter straight tail. (Scale bar, 5 nm.)

Identification of TcdA Domains.

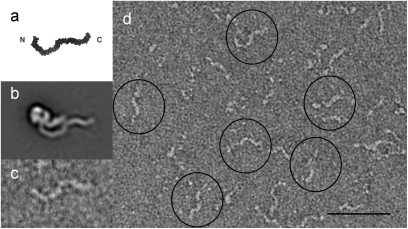

To gain insight into how the functional domains of TcdA are organized in the 3D structure, we performed direct domain visualization and domain subtraction experiments. The C-terminal domain of TcdA is composed of 39 sequence repeats and is responsible for binding cell surface carbohydrates (18). Crystal structures of two fragments from the C terminus of TcdA revealed a β-solenoid fold, suggesting that the entire TcdA C-terminal binding domain would adopt an elongated serpentine structure (6, 18) (Fig. 3A). Several features of this predicted model are seen in the long tail observed by EM (Fig. 3 A and B). To confirm that the long tail is indeed the binding domain, we expressed the TcdA binding domain (amino acids 1832–2710) in Escherichia coli, purified it, and subjected it to negative stain EM (Fig. 3 C and D). The kinks, corresponding to the seven long repeats, and the approximate lengths of the straight sections observed by EM are consistent with the model derived by crystallography (18) (Fig. 3 A–C). Thus, the long kinked tail domain found in our structure represents the C-terminal binding domain of TcdA.

Fig. 3.

Characterization and localization of the TcdA C-terminal binding domain. (A) Predicted model of the TcdA binding domain (18). (B) Average of 4,956 TcdA particles (from Fig. 1D). (C) Image of a single negative stained particle of the TcdA binding domain. (D) Typical electron micrograph area of the recombinantly expressed C-terminal domain of TcdA (1832–2710). A few of the particles are circled in black. (Scale bar, 500 Å.)

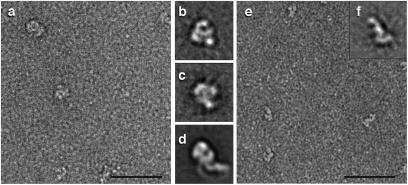

To identify the location of the central TcdA delivery domain, we imaged a recombinantly expressed protein corresponding to residues 799–1859. The images suggest that the protein is capable of binding the grid in a variety of orientations (Fig. 4A), but classification of 1,523 particles into five class averages resulted in two classes of 139 and 314 particles (Fig. 4 B and C) that recapitulate the size, shape, and pincher-like features of the holotoxin head domain (Fig. 4D). An alternative approach, wherein we labeled the toxin with a monoclonal antibody specific for the delivery domain, is presented as part of the supplemental data for this article (Fig. S3). The proposed function of this domain is to change structure in response to the low pH of the endosome and form a pore. To test whether such a structural change would be visible by EM, we applied the protein to a grid and then washed the grid with a buffer at a pH of 4.5 before staining with uranyl formate (Fig. 4E). The most populated class average from this analysis (405 particles out of 1,002 segregated into the image shown in Fig. 4F) suggests that this domain is capable of changing into an extended conformation at low pH.

Fig. 4.

Visualization of the TcdA delivery domain by negative stain EM. (A) Typical electron micrograph showing particles of the TcdA delivery domain. The particles have a globular shape resembling the “head” of TcdA. (Scale bar, 500 Å.) (B and C) Two class averages of the TcdA delivery domain. Classes contain 139 and 314 particles, respectively. Side length of panel is 27.2 nm. (D) Class average of the head of TcdA. Side length of panel is 27.2 nm. (E) TcdA delivery domain was applied to an EM grid, washed with sodium citrate at pH 4.5, and visualized by negative stain EM. (Scale bar, 500 Å.) (F) Class average (405 particles) of the TcdA delivery domain after exposure to a low-pH buffer. Side length of panel is 27.2 nm.

With the long tail identified as the receptor-binding domain, and the head identified as the delivery domain, we hypothesized that the small tail most likely represents the N-terminal glucosyltransferase domain. To test this, we induced autoproteolytic removal of the TcdA glucosyltransferase domain by incubating holotoxin with InsP6 and DTT (Fig. S4). The glucosyltransferase domain was removed by gel-filtration chromatography, and the larger fragment was analyzed by negative stain EM (Fig. 5A). Upon examining the images of cleaved TcdA (Fig. 5 A and B), it is clear that whereas the long tail and globular domains are still visible, the shorter tail is missing. Thus, the shorter tail domain seen in the 3D TcdA structure is the glucosyltransferase domain.

Fig. 5.

Localization of the TcdA N-terminal glucosyltransferase domain by autoproteolysis. Cleavage of TcdA was induced by the addition of InsP6 and DTT. The large fragment containing residues 543–2710 was isolated, applied to a grid, stained with uranyl formate, and visualized by EM. (A) Representative image of cleaved TcdA particles in negative stain. (Scale bar, 500 Å.) (B) Gallery of TcdA cleaved particles. Although the head and long kinked tail domain are visible, the short tail region is missing. The side length of each panel is 57.3 nm.

A model of the binding domain of TcdA was placed into the 3D EM map (Fig. 6). The N terminus of the domain connects to the back of the head near the larger of the pincher domains, whereas the C terminus extends away from the rest of the toxin. As is common for negative stained specimens, the binding domain was somewhat flattened in the EM map compared with the model. The distortion was fairly minor, however, and most of the model clearly and unambiguously fit into the EM map. The crystal structure of the glucosyltransferase domain of TcdB was placed into the small tail in the EM map with the N terminus distal from the head domain (Fig. 6). The domain is 90 Å long, consistent with the ≈100 Å length of the short tail, and is ≈25 Å wide at the extreme N terminus. The C-terminal side of the domain is considerable larger with a diameter of ≈65 Å. The small tail in the EM map has a narrow distal end and a larger, wider region near the head that is consistent with the shape of the TcdB glucosyltransferase domain. We did not determine the location of the autoprotease domain experimentally. However, there are only four amino acids between the glucosyltransferase and autoprotease domains that are not present in either crystal structure. The crystal structure of the autoprotease domain was, therefore, positioned between the small tail and the small pincher domain and oriented so that the C-terminal residue of the glucosyltransferase structure (Leu542) could be connected with the N-terminal residue of the autoprotease structure (Gly547) using a short linker.

Fig. 6.

Placement of the functional domains of TcdA within EM map. (A and B) 3D reconstruction of TcdA filtered to 25 Å, shown as mesh surface. Structures of the TcdB glucosyltransferase domain (red), the TcdA autoprotease domain (blue), and a model of the TcdA binding domain (green) were manually docked into the density. B shows two views of the toxin enlarged to show the placement of the glucosyltransferase and protease domains.

pH-Dependent Conformational Changes of TcdA.

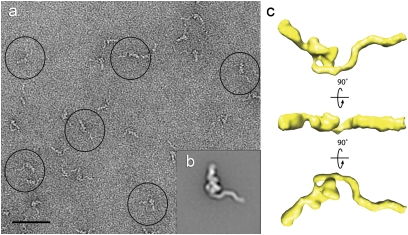

To understand the structural basis for pore formation within the endosome, we analyzed TcdA particles at low pH. TcdA was applied to a carbon-coated, glow-discharged grid, washed with a pH 4.5 buffer, and then stained with uranyl formate. This resulted in a clear conformational change in the toxin, as shown in Fig. 7A (compare with Fig. 1C). To examine the structural homogeneity of TcdA in a low-pH state, ≈4,000 particles were selected from images of untilted specimens and classified into 10 groups. This analysis revealed a number of classes with structurally homogenous particles suitable for further structural analysis (Fig. S5A). Significantly, although the binding domain in these classes looks similar to TcdA at neutral pH, the head domain clearly has undergone a major conformational rearrangement (compare Fig. 7A with Fig. 1D). To more carefully address the structural changes in TcdA structure at endosomal pH, additional images of TcdA in a low-pH state were collected at 60° and 0°. A total of 8,319 particle pairs were selected, and images from the untilted specimens were grouped into four classes by reference-based alignment using references chosen from the original alignment of ≈4,000 particles (Fig. S5A, marked by *). Two of the resulting classes looked very similar, differing only in the orientation of the receptor-binding domain relative to the head domain (Fig. S5B, marked by *). One of these classes was used to generate a 3D reconstruction with a resolution of ≈30 Å (Fig. 7C, Movie S2, and Fig. S5C).

Fig. 7.

pH-induced conformational changes of TcdA. TcdA was adsorbed to a carbon-coated glow-discharged grid, washed with 50 mM sodium citrate at pH 4.5, and stained with 0.7% uranyl formate. (A) Typical electron micrograph of TcdA at low pH. A few of the particles are circled in black. (Scale bar, 500 Å.) (B) Representative class average of negatively stained TcdA particles (1,327) at low pH. Side length of panel is 57.3 nm. (C) 3D reconstruction of TcdA in a low-pH state, shown filtered to 30 Å.

The 3D structure of TcdA at low pH shows a molecule that has undergone a major conformational change from the structure observed at neutral pH. Although the conformation of the binding domain has not changed, the low pH form is more elongated due to an extension in the opposite direction from the binding domain. This extended “appendage” is ≈100 Å long and ≈40 Å × ≈40 Å wide at the distal end. The proximal end where the appendage connects to the rest of the toxin is narrower (≈20 Å × 20 Å). The orientation of this extended appendage is relatively flexible, as seen in both the class averages and 3D reconstructions (Fig. S5B).

The low-pH structure of TcdA has a volume that corresponds to a molecular mass of ≈240 kDa and is thus considerably smaller than the structure of native TcdA, whose volume corresponds to a molecular mass of ≈320 kDa. Because the low- and neutral-pH forms of the toxin look identical by SDS/PAGE (Fig. S6A), this difference may be due to greater flexibility and/or partial unfolding at low pH. When comparing the neutral- and low-pH structures, it seems that much of this volume difference can be attributed to the glucosyltransferase domain. To investigate whether the TcdA glucosyltransferase domain unfolds at low pH, we purified this domain and tested its solubility in a range of pH conditions. At pH <5 the glucosyltransferase domain precipitates (Fig. S6B), consistent with the behavior of an unfolded protein.

Discussion

The homology between TcdA and TcdB (68% similar, 47% identical) and the similar modes of entry suggest that these toxins will adopt similar 3D structures. Although in our studies TcdB was more structurally heterogeneous than TcdA, both toxins clearly have a bilobed, globular “head” domain that directly connects to two extended tails. Because of the similarities between TcdA and TcdB at both a structural and primary sequence level, we propose that, as with TcdA, the TcdB globular head domain represents the delivery domain, whereas the short tail contains the glucosyltransferase domain and the serpentine tail corresponds to the receptor-binding domain. Because TcdA was considerably more homogeneous in structure, we focused our domain mapping and 3D structural studies on this protein.

The structures of TcdA holotoxin provide a framework for considering the molecular events required for LCT cellular intoxication. The first event is molecular recognition of a receptor on the surface of host cells. Studies suggest that the receptors for TcdA likely differ from those used by TcdB, although both toxins can bind specifically to carbohydrate structures containing an N-acetyl-lactosamine core (8, 23, 24). The TcdA and TcdB binding domains consist of two types of repetitive peptide sequences: 19–22-aa short repeats and 31-aa long repeats (7). In TcdA, 32 short repeats are interspersed by 7 long repeats (18). Crystal structures of binding domain C-terminal fragments have revealed that the short repeats form β-solenoid subunits that pack together in extended rods (6, 17, 18). Long repeats also form β-solenoids but are packed differently, yielding kinks in the rods. Each long repeat together with an adjacent short repeat forms a binding site for the saccharide receptors (6). A model of the entire TcdA binding domain generated from crystallographic data and the protein sequence suggests an extended kinked structure that agrees well with our EM observations (Fig. 3) (18). Although a narrow, elongated structure might be expected to adopt multiple conformations, our EM images indicate that the domain is fairly rigid. This rigidity is consistent with the highly conserved packing interactions and regular rotational relationships observed between the long and short repeats in three different crystal structures of TcdA fragments. This is also reflected by the homogeneity of the particles and the fact that the domain structure does not change with pH. The structure demonstrates that the binding domain extends away from the delivery domain, such that multiple binding sites are accessible, consistent with a model of multivalent binding.

The principle difference in the 2D images of TcdA and TcdB is that the TcdB density corresponding to the receptor-binding domain tail is considerably shorter, consistent with it being 40% shorter in its sequence. The structure of this domain is predicted to have four structural modules (each consisting of three to five short repeats and one long repeat) as compared with seven in TcdA (18). Truncating the TcdA structural model after four modules results in a structure similar in length and shape to what we observe by EM. The density for the TcdB receptor-binding domain was more difficult to observe in our class averages (Fig. S2 D and E). We interpret this to mean that the TcdB receptor-binding domain is able to adopt multiple orientations with respect to the rest of the molecule. This heterogeneity is the likely explanation for why the molecular envelope for TcdB obtained by SAXS differs from what we observe (17) because ab initio envelope calculations from scattering data can be problematic in flexible systems in which domain orientations differ between conformers (25, 26).

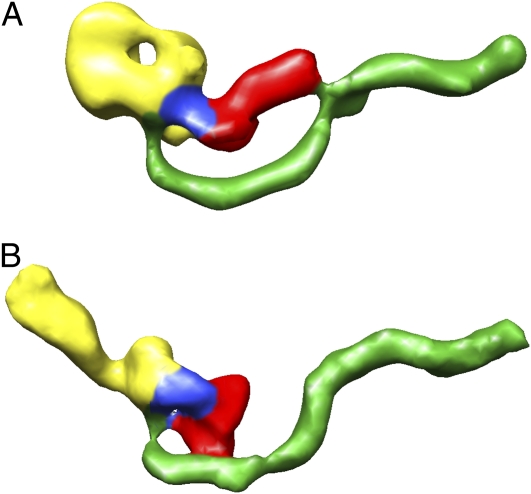

TcdA and TcdB have been proposed to undergo pH-dependent conformational changes to form a pore through which the glucosyltransferase domain is translocated (10). We have directly visualized pH-inducible changes in TcdA and the TcdA delivery domain by exposing them to low pH on EM grids. We see significant changes in the pincher-like head of the delivery domain that results in its extension away from the binding domain (Fig. 4 E and F and Fig. 8). This might be accomplished through a decoupling of the two lobes of the head, effectively opening the pincher.

Fig. 8.

Model of the conformational changes induced at low pH. 3D reconstruction of TcdA in a (A) neutral-pH and (B) low-pH state. The proposed locations of the functional domains are colored as follows: red, glucosyltransferase; blue, autoprotease; yellow, delivery; and green, binding.

The two-lobed pincher-like structure of the head reveals that the TcdA delivery domain has a complex structure and might contain two subdomains. BLAST analysis of the complete TcdA delivery domain (residues 801–1831) reveals that there are two regions with distinct homology profiles: residues ≈801–1400 (D1) and 1401–1831 (D2) (Fig. S7) (27). TcdA D1 is more highly conserved among LCTs (55% identity with TcdB) than D2 (33% identity with TcdB) and contains the putative membrane-spanning residues, suggesting that D1 is the region that rearranges to form the elongated appendage of the low-pH form. In D2, most of the BLAST homologs are distant and uncharacterized, but the region is thought to enhance the binding of TcdA to cells (8) and contains an Asp-Ser-Gly motif, which may be involved in toxin delivery into the cytosol (16). Further study is needed to dissect the respective roles of these delivery domains in the context of the membrane.

Release of the glucosyltransferase domain into the cell is mediated by the adjacent cysteine protease domain (15). The location of the autoprotease domain within the map of TcdA was not experimentally determined, but the structure is anticipated to be located so that the C terminus of the glucosyltransferase domain can be cleaved in the active site of the protease (19). The TcdA autoprotease domain is known to undergo significant rearrangement upon exposure to InsP6 (19). Analysis of cleaved TcdA in negative stain reveals that the particles are much more heterogenous than those of native TcdA and impeded our efforts to obtain class averages. The heterogeneity of cleaved TcdA likely results from the removal of the glucosyltransferase domain, because this domain makes contact with the binding domain in the structure determined at neutral pH. It is tempting to speculate that this contact may help “lock” the TcdA head in a nonpore forming state, a model that is further supported by our data showing that the glucosyltransferase domain loses structural stability at low pH.

In our structures of TcdA, we observed a smaller volume at low pH than in the neutral-pH structure. We attribute this loss of volume to partial unfolding of the glucosyltransferase domain. The enzymatic components of anthrax toxin, botulinum neurotoxin, and diphtheria toxin have also been shown to unfold at low pH (28–30). In these toxins, which also form pores at endosomal pH, unfolding is thought to be necessary for translocation of the enzymatic domains through narrow membrane pores. Despite this mechanistic similarity, anthrax toxin, botulinum neurotoxin, and diphtheria toxin have been noted for their diversity in structure (31). The unique structural features observed in this study, namely a bilobed delivery domain tethered to enzymatic cargo and a serpentine receptor-binding domain, suggest that TcdA and TcdB represent yet another structural theme for bacterial protein toxins. Further work is needed to understand the commonalities and differences between the TcdA and TcdB structures and how these structures guide the complex functions of these molecules.

Methods

Cloning.

DNA corresponding to the TcdA receptor-binding domain (amino acids 1832–2710), TcdA delivery domain (amino acids 799–1859), and TcdB holotoxin was amplified from C. difficile strain 10643 genomic DNA. The TcdA domains were cloned into a modified pET27 vector such that the resulting proteins contain an N-terminal His10 tag separated from the protein by a 3C protease cleavage site. After 3C cleavage, only nonnative residues GPGS remain. DNA corresponding to the TcdB holotoxin was cloned into a pHis1622 (MoBiTec, BMEG20) vector using the restriction sites BsrGI and KpnI.

Protein Expression and Purification.

Native TcdA was obtained from the supernatant of C. difficile strain 10643 grown in dialysis sac culture, as described previously (1). TcdA was purified from the supernatant by multiple rounds of anion-exchange chromatography, followed by gel-filtration chromatography in 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0. The identity of TcdA was verified by mass spectrometry. TcdB was expressed in Bacillus megaterium as described previously (32) except cells were harvested ≈4 h after induction. All recombinant single domains were expressed from E. coli as reported previously for the autoprotease domain (19), except BL21(DE3)-CodonPlus cells (Stratagene) were used. Accordingly, 35 mg chloramphenicol was added for every liter of media. At the final step in purification, proteins were exchanged into 50 mM NaCl and 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, by gel filtration chromatography.

Autoproteolysis of TcdA.

Purified TcdA (100 μg) in 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, was mixed with 100 mM InsP6 and 100 mM DTT and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Some of the protein precipitated during this process. Protein that remained soluble was run on a S200 gel-filtration column in 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0.

Specimen Preparation and EM.

Uranyl formate (0.7% wt/vol) was used for conventional negative staining as previously described (33). The low-pH TcdA delivery domain and TcdA holotoxin grids were prepared as above, except the grid was washed with 50 mM sodium citrate, pH 4.5, instead of water.

Images of TcdA holotoxin at neutral and low pH were recorded using a Tecnai T12 electron microscope (FEI) equipped with a LaB6 filament and operated at an acceleration voltage of 120 kV. Images were taken under low-dose conditions at a magnification of ×67,000 using a defocus value of −1.5 μm. Images were recorded on DITABIS digital imaging plates. The plates were scanned on a DITABIS micrometer scanner, converted to mixed raster content (mrc) format, and binned by a factor of 2, yielding final images with 4.48 Å/pixel. Images of cleaved TcdA were collected under similar conditions except images were recorded using a 2,048 × 2,048-pixel Gatan CCD camera. Cleaved TcdA images were also converted to mrc format and binned by a factor of 2, resulting in final images with 3.0 Å/pixel.

Images of TcdB and the TcdA delivery domain were collected on a Tecnai F20 electron microscope equipped with a field emission electron source and operated at an acceleration voltage of 120 kV under low-dose conditions at a magnification of ×100,000 and a defocus value of −1.5 μm. Images were collected using a Gatan 4K × 4K CCD camera. CCD images were converted to mrc format and binned by a factor of 4, resulting in final images with 4.26  /pixel.

/pixel.

Particle images of cleaved TcdA, TcdA delivery domain, and TcdB were selected with Boxer (34) and windowed with 192-pixel (3.0 Å/pixel), 64-pixel (4.26 Å/pixel), and 120-pixel (4.26 Å/pixel) side lengths, respectively. Image analysis was carried out with SPIDER and the associated display program WEB (35).

Random Conical Tilt Reconstruction of Negatively Stained TcdA.

Micrograph tilt pairs of TcdA at neutral and low pH were recorded at 60° and 0°. Particle pairs (7,396 at neutral pH and 8,319 pairs at low pH) were selected interactively from both the images of the untilted and 60° tilted sample using WEB and windowed into 128 × 128-pixel images (4.48 Å/pixel). The untilted images were rotationally and translationally aligned and subjected to 10 cycles of multireference alignment and K-means classification. Particles of neutral-pH TcdA were grouped into 12 classes (Fig. S2A). From the class averages, three representative projections were chosen and used as references for another cycle of multireference alignment (Fig. S2A, marked with a “*”). TcdA particles at low pH were aligned to four references chosen from a previous alignment of ≈4,000 images of TcdA at a low pH (Fig. S5A, marked with a “*”).

The larger of the resulting classes for both the neutral pH and low pH TcdA particles (4,956 and 2,503 particles, respectively) (Figs. S2B and S6B, marked with a “*”) were used to calculate an initial 3D reconstruction by back-projection using the in-plane rotation angles determined by rotational alignment and the preselected tilt angle of 60° implemented in the processing package SPIDER (35). The density map was improved by back-projection and angular refinement in SPIDER. Ten percent of the particles selected from the images of the untilted specimens in either the neutral- or low-pH class were included in the data set (500 and 250 particle images, respectively), and angular refinement was repeated. The FSC curve corresponds to normalized cross-correlation coefficients of Fourier shells from even and odd particles within the dataset. Using an FSC = 0.5 criteria (Figs. S2C and S6C), neutral- and low-pH structures were filtered to 25-Å and 30-Å resolutions, respectively. The 3D structure of the neutral-pH TcdA structure was also filtered using the IMAGIC-V software package (36) using the THREED-SMOOTH command to diminish “salt and pepper” noise from the map by removing single voxels that were unconnected to the main volume of the 3D density. The contouring threshold was chosen so that the volume of each TcdA structure was continuous. The estimated molecular weight of each structure was then calculated in IMAGIC-V (36) using this value and a protein density of 0.8 Da/Å3. The surface rendering of the structure was performed with the program Chimera (37).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Walz for helpful advice and discussion. This project was funded by the training program in Cellular and Molecular Microbiology (R.N.P.), an Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (D.B.L.), and Vanderbilt University Development Funds (M.D.O.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1002199107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lyerly DM, Krivan HC, Wilkins TD. Clostridium difficile: Its disease and toxins. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1988;1:1–18. doi: 10.1128/cmr.1.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voth DE, Ballard JD. Clostridium difficile toxins: Mechanism of action and role in disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:247–263. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.247-263.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyras D, et al. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2009;458:1176–1179. doi: 10.1038/nature07822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nottrott S, Schoentaube J, Genth H, Just I, Gerhard R. Clostridium difficile toxin A-induced apoptosis is p53-independent but depends on glucosylation of Rho GTPases. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1443–1453. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qa’Dan M, et al. Clostridium difficile toxin B activates dual caspase-dependent and caspase-independent apoptosis in intoxicated cells. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4:425–434. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greco A, et al. Carbohydrate recognition by Clostridium difficile toxin A. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:460–461. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Eichel-Streiber C, Sauerborn M. Clostridium difficile toxin A carries a C-terminal repetitive structure homologous to the carbohydrate binding region of streptococcal glycosyltransferases. Gene. 1990;96:107–113. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90348-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frisch C, Gerhard R, Aktories K, Hofmann F, Just I. The complete receptor-binding domain of Clostridium difficile toxin A is required for endocytosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:706–711. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02919-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Florin I, Thelestam M. Lysosomal involvement in cellular intoxication with Clostridium difficile toxin B. Microb Pathog. 1986;1:373–385. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(86)90069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qa'Dan M, Spyres LM, Ballard JD. pH-induced conformational changes in Clostridium difficile toxin B. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2470–2474. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2470-2474.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barth H, et al. Low pH-induced formation of ion channels by Clostridium difficile toxin B in target cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10670–10676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jank T, Aktories K. Structure and mode of action of clostridial glucosylating toxins: The ABCD model. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Just I, et al. The enterotoxin from Clostridium difficile (ToxA) monoglucosylates the Rho proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13932–13936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Just I, et al. Glucosylation of Rho proteins by Clostridium difficile toxin B. Nature. 1995;375:500–503. doi: 10.1038/375500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egerer M, Giesemann T, Jank T, Satchell KJ, Aktories K. Auto-catalytic cleavage of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B depends on cysteine protease activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25314–25321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reineke J, et al. Autocatalytic cleavage of Clostridium difficile toxin B. Nature. 2007;446:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature05622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albesa-Jové D, et al. Four distinct structural domains in Clostridium difficile toxin B visualized using SAXS. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:1260–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho JG, Greco A, Rupnik M, Ng KK. Crystal structure of receptor-binding C-terminal repeats from Clostridium difficile toxin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18373–18378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506391102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pruitt RN, et al. Structure-function analysis of inositol hexakisphosphate-induced autoprocessing in Clostridium difficile toxin A. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21934–21940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinert DJ, Jank T, Aktories K, Schulz GE. Structural basis for the function of Clostridium difficile toxin B. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radermacher M, Wagenknecht T, Verschoor A, Frank J. Three-dimensional reconstruction from a single-exposure, random conical tilt series applied to the 50S ribosomal subunit of Escherichia coli. J Microsc. 1987;146:113–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1987.tb01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Böttcher B, Wynne SA, Crowther RA. Determination of the fold of the core protein of hepatitis B virus by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 1997;386:88–91. doi: 10.1038/386088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krivan HC, Clark GF, Smith DF, Wilkins TD. Cell surface binding site for Clostridium difficile enterotoxin: Evidence for a glycoconjugate containing the sequence Gal alpha 1-3Gal beta 1-4GlcNAc. Infect Immun. 1986;53:573–581. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.573-581.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dingle T, et al. Functional properties of the carboxy-terminal host cell-binding domains of the two toxins, TcdA and TcdB, expressed by Clostridium difficile. Glycobiology. 2008;18:698–706. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Putnam CD, Hammel M, Hura GL, Tainer JA. X-ray solution scattering (SAXS) combined with crystallography and computation: Defining accurate macromolecular structures, conformations and assemblies in solution. Q Rev Biophys. 2007;40:191–285. doi: 10.1017/S0033583507004635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pretto DI, et al. Structural dynamics and single-stranded DNA binding activity of the three N-terminal domains of the large subunit of replication protein A from small angle X-ray scattering. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2880–2889. doi: 10.1021/bi9019934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao JM, London E. Conformation and model membrane interactions of diphtheria toxin fragment A. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15369–15377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koriazova LK, Montal M. Translocation of botulinum neurotoxin light chain protease through the heavy chain channel. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:13–18. doi: 10.1038/nsb879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wesche J, Elliott JL, Falnes PO, Olsnes S, Collier RJ. Characterization of membrane translocation by anthrax protective antigen. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15737–15746. doi: 10.1021/bi981436i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lacy DB, Stevens RC. Unraveling the structures and modes of action of bacterial toxins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:778–784. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang G, et al. Expression of recombinant Clostridium difficile toxin A and B in Bacillus megaterium. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:192. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohi M, Li Y, Cheng Y, Walz T. Negative staining and image classification—powerful tools in modern electron microscopy. Biol Proced Online. 2004;6:23–34. doi: 10.1251/bpo70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludtke SJ, Baldwin PR, Chiu W. EMAN: Semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J Struct Biol. 1999;128:82–97. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank J, et al. SPIDER and WEB: Processing and visualization of images in 3D electron microscopy and related fields. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:190–199. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Heel M, Harauz G, Orlova EV, Schmidt R, Schatz M. A new generation of the IMAGIC image processing system. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:17–24. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.