Abstract

In various types of stem cells, including embryonic stem (ES) cells and hematopoietic stem cells, telomerase functions to ensure long-term self-renewal capacity via maintenance of telomere reserve. Expression of the catalytic component of telomerase, telomerase reverse transcriptase (Tert), which is essential for telomerase activity, is limiting in many types of cells and therefore plays an important role in establishing telomerase activity levels. However, the mechanisms regulating expression of Tert in cells, including stem cells, are presently poorly understood. In the present study, we sought to identify genes involved in the regulation of Tert expression in stem cells by performing a screen in murine ES (mES) cells using a shRNA expression library targeting murine transcriptional regulators. Of 18 candidate transcriptional regulators of Tert expression identified in this screen, only one candidate, hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha (Hif1α), did not have a significant effect on mES cell morphology, survival, or growth rate. Direct shRNA-mediated knockdown of Hif1α expression confirmed that suppression of Hif1α levels was accompanied by a reduction in both Tert mRNA and telomerase activity levels. Furthermore, gradual telomere attrition was observed during extensive proliferation of Hif1α-targeted mES cells. Switching Hif1α-targeted mES cells to a hypoxic environment largely restored Hif1α levels, as well as Tert expression, telomerase activity levels, and telomere length. Together, these findings suggest a direct effect of Hif1α on telomerase regulation in mES cells, and imply that Hif1α may have a physiologically relevant role in maintenance of functional levels of telomerase in stem cells.

Keywords: telomere, embryo

A hallmark feature of stem cells is the capacity for long-term proliferation. Unlike mature somatic cells, such as fibroblasts (1), both human (2) and murine (3) embryonic stem (ES) cells are immortal in vitro. It is also well established that small numbers of hematopoietic stem cells can be serially transplanted four to six times in mice, accompanied by full reconstitution of the hematopoietic system by the donor stem cells at each successive generation of transplant (4, 5). This characteristic of stem cells likely plays a role in sustaining growth during embryonic and postpartum development, and ensuring sufficient replicative capacity of stem cells to replace damaged or dead cells throughout adult life, particularly in highly proliferative organs and tissues. One factor that is crucial for the maintenance of long-term replicative capacity of stem cells is the enzymatic complex telomerase.

Telomerase is a specialized reverse transcriptase that functions to complete replication of telomeric DNA in proliferating cells. Telomeres are genetic elements located at the ends of chromosomes and are composed of a tract of telomeric DNA repeats, (TTAGGG)n in mammals, and several telomere-binding proteins that facilitate the folding of the telomere into a protective cap (6). In cells with low levels or no detectable telomerase activity, telomere reserve gradually diminishes as cells proliferate (7, 8), ultimately triggering cell senescence once the size of one or more telomeres drops below a length that is critical for functional capping at the ends of chromosomes (9). Ectopic expression of the catalytic component of telomerase, telomerase reverse transcriptase (Tert) (10), has been shown in a number of different types of human somatic cells to be sufficient to reactivate telomerase and prevent senescence induced by the attrition of telomeres (11). Furthermore, though the expression of the telomerase RNA component—which, like Tert, is also essential for telomerase activity—is widespread in at least some human tissues, Tert expression is much more restricted, and only detectable in highly proliferative cells (12). This indicates that the primary, but not the only, mechanism of regulating telomerase levels in cells is via regulation of expression of Tert.

Several independent studies have shown that, in stem cells, telomerase has the important role of ensuring sufficient replicative capacity and preventing premature exhaustion of the stem cell pool during aging and in response to stressors that induce accelerated stem cell turnover (13–16). Though a number of candidate transcriptional regulators of Tert expression have been identified in human cells in vitro (17, 18), the factors that regulate telomerase levels in stem cells, including the expression level Tert, are still poorly understood. Therefore, in the study reported here, we have performed an RNAi screen to identify transacting factors required to maintain Tert expression in murine embryonic stem cells (mES).

Results

RNAi-Mediated Screen for Candidate Transcriptional Regulators of Tert Expression in ES Cells.

To identify transcriptional regulators of Tert expression in ES cells, we developed a murine ES cell line that stably expresses GFP under control of the murine Tert gene promoter (Tertp-eGFP). The Tertp-eGFP expression construct was created by PCR amplifying a 2.0-Kb fragment of the Tert gene promoter from mES cell genomic DNA and subcloning it into a promoterless eGFP expression construct (pGFP-1; see Fig. S1 and Experimental Proceduresfor further details). Following verification of GFP expression in mES cells transiently transfected with Tertp-eGFP, we derived a mES cell line that stably expressed GFP under control of the Tert promoter using electroporation followed by neomycin resistance selection (Fig. 1A).

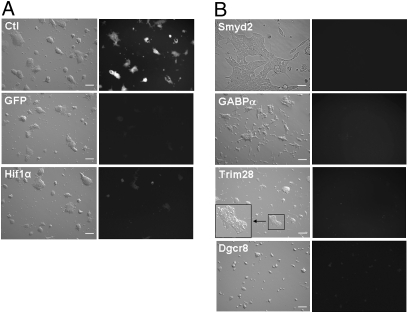

Fig. 1.

Tert knockdown phenotypes in Tert-eGFP reporter mES cells. (A Top) Tert-eGFP mES cells transfected with a nontargeting (scrambled) control shRNA vector show high levels of GFP expression. (Middle) mES cells transfected with a shRNA vector targeting GFP show efficient knockdown of GFP expression, as predicted. (Bottom) mES cells targeted for Hif1α knockdown show reduced GFP expression and have similar morphology to the control mES cells. (B) Adverse phenotypes associated with reduced GFP expression. Sample of stably transfected mES cells with an enlarged, flattened morphology (Smyd2 KD), elongated spindular morphology (GABPα KD), increase in cell death (Trim28 KD), and reduced growth rate (Dgcr8 KD) are shown. The inset in the panel for Trim28 KD reveals the increased number of dead cells in an ES cell colony. (Scale bar: 200 μm.)

For this screen, we used a shRNA expression library that targets 1,360 different murine transcriptional regulators. This library uses a modified MSCV retroviral vector (pSHAG-MAGIC, pSM2) for vector DNA delivery, and expresses the shRNA in the context of the endogenous microRNA Mir30 to ensure efficient processing of the targeting shRNA (Fig. S1). This shRNA expression system has been shown to efficiently knock down the targeted mRNAs both in vitro and in vivo (19, 20). To specifically identify transcriptional regulators affecting Tert expression, we used the packaged library to transform the Tertp-GFP mES cell line at low multiplicity of infection. Following puromycin selection of stable transformants, we identified and isolated mES colonies expressing low levels of GFP, purified genomic DNA, and PCR amplified and sequenced the shRNA cassette to identify the targeted gene (Fig. S1).

In initial experiments using shRNA expression vectors targeting GFP or expressing a nontargeting, scrambled shRNA (control), we verified the utility of these vectors to specifically knock down expression of the target gene in ES cells (Fig. 1A). After several rounds of transforming mES cells with different, nonoverlapping, pools of the shRNA library, we identified a total of 18 candidate transcriptional regulators of Tert expression (Table S1). For most of these candidates, targeted knockdown also had additional overt effects on the mES cells, including altered morphology and/or an increase in cell death (Fig. 1B and Table S1), with exception of the transcriptional regulators DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 (Dgcr8) Dgcr8 and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (Hif1α).

Knockdown of Hif1α in mES Cells Has Minimal Effects on mES Cell Phenotype.

Because the level of telomerase activity has been shown to frequently correlate with mitotic activity (21, 22), we monitored the growth rate of mES cells during targeted knockdown of Dgcr8 and Hif1α. Following 5 d of continuous growth in vitro, knockdown of Dgcr8 had a dramatic inhibitory effect on growth rate (≥2-fold), whereas only a slight reduction in growth rate was observed in mES cells targeted for Hif1α knockdown (Fig. S2 and Table S1). These findings suggest that Hif1α may potentially have a direct role in the transcriptional regulation of Tert expression in mES cells, whereas targeted knockdown of Dgcr8 likely effects Tert expression indirectly, at least in part via effects on proliferation rate.

To assess the effect of targeted knockdown of Hif1α expression on mES cells at the molecular level, we compared the level of expression of established markers for pluripotency, specifically Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, and RexA1, between Hif1α-targeted mES cells and control mES cells (expressing a nonspecific shRNA) using real time RT-PCR. With the exception of RexA1, we observed no significant difference in expression for these genes between Hif1α-targeted mES cells and control mES cells (Fig. S2B). Together with the observation that Hif1α was the only transcriptional regulator identified multiple times in the screen for transcriptional regulators of Tert expression (Table S1), these findings indicate Hif1α is the most promising lead candidate from our screen for a potential transcriptional regulator of Tert expression in mES cells. Therefore, we sought to more closely examine the effect of targeted knockdown of Hif1α on telomerase function in mES cells.

Directed Knockdown of Hif1α Causes Attenuation in Both Tert Expression and Telomerase Activity.

To verify whether Hif1α knockdown can directly repress Tert expression, we transformed Tertp-GFP mES cells with one of two different nonoverlapping Hif1α-targeting shRNA expression vectors, and assessed Hif1α and Tert mRNA levels by real-time RT-PCR. Following stable transformation with both of the Hif1α-targeting vectors, we observed a significant reduction in both the relative levels of Hif1α and Tert mRNA as compared with mES cells transformed with the control (scrambled) shRNA vector (Fig. 2A). This reduction in both Hif1α and Tert expression was also observed following transient (72 h posttransduction) knockdown, and also in a second mES cell line established from 129/J mice (Fig. S3). These findings confirm that Hif1α KD in mES cells attenuates Tert expression, and are consistent with a direct transacting role of Hif1α in regulating Tert expression, as indicated by the knockdown effect observed at 72 h posttransduction.

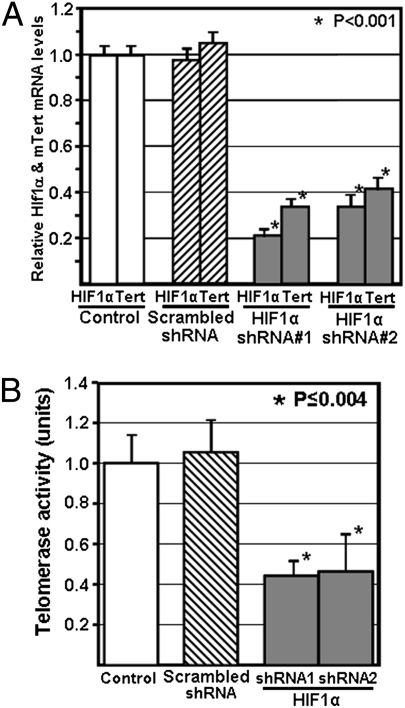

Fig. 2.

Targeted knockdown of Hif1α in mES cells causes a reduction in endogenous Tert mRNA expression and telomerase activity levels. (A) Tertp-eGFP mES cells were stably trasnformed with either a nontargeting control shRNA vector or one of two different shRNA vectors targeting Hif1α. Tert mRNA and Hif1α mRNA levels were assessed using real-time RT-PCR, and are shown relative to GAPDH. “Control” refers to measurements for Tertp-eGFP mES cells. (B) Telomerase activity levels were assessed using the TRAP assay in the same stably transfected Tertp-eGFP mES cells used for analysis of Tert mRNA levels shown in A. Tert mRNA levels and telomerase activity levels in mES cells stably transfected with the nontargeting shRNA vector were arbitrarily assigned a value of 1. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in mRNA levels or telomerase activity levels relative to control mES cells.

To assess whether this reduction in Tert mRNA was sufficient to affect telomerase, we also assessed telomerase activity using the TRAP assay for both Hif1α-targeting vectors. Following puromycin selection of stable transformants, we observed a significant reduction in telomerase activity levels (∼55% loss) for Tertp-GFP mES cells subjected to Hif1α knockdown, as compared with control mES cells (Fig. 2B). Targeted knockdown of Hif1α in the unmodified SCRC-1002 mES cell line, as well as a 129/J mES cell line, also resulted in significantly reduced levels of telomerase activity (Fig. S3). These findings suggest that telomerase function may be compromised in mES cells with reduced expression of Hif1α.

Hif1α Maintains Homeostatic Levels of Tert in mES Cells by Direct Transactivation.

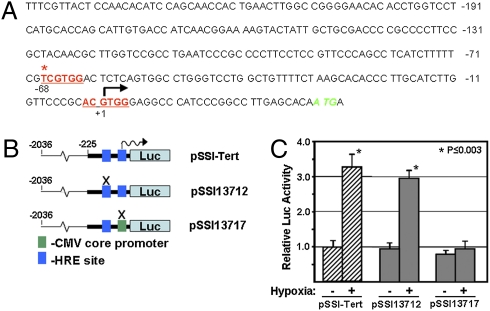

Upon exposure of cells to a hypoxic environment, Hif1α regulates the expression of downstream genes by associating with cis-acting sequences in the promoter region termed hypoxic response elements (HRE) (23). Analysis of the core promoter region of the murine Tert gene (+1 to −225) (24) revealed two potential HRE sites at positions −68 and +1 (Fig. 3A). To assess whether Hif1α directly regulates Tert expression in mES cells, we developed a Tert promoter-luciferase (pSSI-Tert) reporter construct and systematically mutated these HRE (Fig. 3B). Because the +1 HRE site coincides with the putative transcriptional start site for the murine Tert transcript, we replaced it with a minimal CMV promoter to prevent potential ablation of transcription initiation (Fig. 3B). These luciferase (Luc) reporter constructs were then introduced into mES cells, and Luc activity levels were analyzed. Under normoxic culture conditions, both the wild-type pSSI-Tert construct and all mutant constructs produced detectable levels of Luc activity (Fig. 3C). However, exposure of the mES cells to hypoxic culture conditions following transfection with these vectors showed a lack of hypoxic induction of Luc activity for the +1 HRE mutant construct (Fig. 3C). These observations suggest that the +1 HRE site in the murine Tert promoter is essential for the Hif1α-dependent regulation of Tert expression in mES cells, in agreement with previous studies that have reported a direct role for Hif1α in regulating Tert expression in human cell lines (25–27) and fish tissue (28). Because Luc activity levels were similar for both wild-type pSSI-Tert construct and −68 HRE mutant construct under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions, the sequence at −61 to −68 of the Tert promoter is likely not a functional HRE. This is not unexpected given the slight variation in this sequence (TCGTG(G/X) from the canonical HRE consensus sequence (X/Y)CGTG(G/X) (23, 29).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of the mechanism of Hif1α-mediated regulation of Tert mRNA expression in mES cells. (A) Identification of two candidate HRE sites in the proximal (−225 to +1) murine Tert promoter. The HRE site at +1 conforms to the canonical HRE sequence (X/Y)CGTG(G/X), and the site at −65 diverges from this sequence at one nucleotide as indicated (asterisk). (B) Schematic showing the different Tert promoter-luciferase reporter constructs harboring wild-type or mutant HRE sites within the murine Tert proximal promoter. The same 2.0-Kb Tert promoter fragment used to develop the Tert-eGFP reporter ES cells was also used to create each of the Tert-Luc reporter constructs. The candidate HRE sites were mutated by site-directed mutagenesis. (C) Quantitative analysis of luciferase activity levels in mES cells transfected with the Tert-Luc reporter constructs show in B, grown under normoxic or hypoxic (1% oxygen) culture conditions. Error bars represent SD (n ≥ 3), and P value represents comparison of Luc activity in cells grown under hypoxic conditions relative to normoxic conditions, for the particular Tert-Luc reporter construct indicated by an asterisk (Student's t test).

Exposure of Hif1α-Targeted mES Cells to a Hypoxic Environment Is Sufficient to Restore Hif1α and Telomerase Levels.

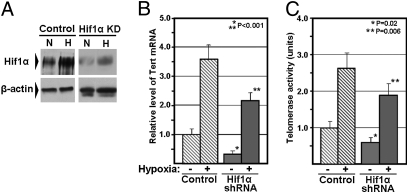

The primary mechanism for up-regulation of Hif1α levels in cells in response to hypoxia occurs at the posttranslational level by a mechanism involving stabilization of Hif1α, mediated via posttranslational modification of specific prolyl residues in the oxygen-dependent degradation domain (30). Therefore, to further demonstrate a direct, functional role of Hif1α in regulating Tert expression and telomerase activity in mES cells, we transiently exposed both control mES cells and Hif1α-targeted mES cells to a hypoxic culture environment (1% atmospheric oxygen) and analyzed the effect on Tert expression and telomerase activity. Western analysis confirmed that Hif1α levels were inducible in response to hypoxia in both control and Hif1α-targeted mES cells (Fig. 4A). Quantitative analysis of Tert mRNA and telomerase activity levels showed a significant increase in both the level of Tert expression and telomerase activity for control and Hif1α-targeted mES cells following exposure to hypoxia (Fig. 4 B and C). Thus Hif1α is able to transactivate Tert in response to hypoxia in mES cells, and also reverse the telomerase-related effects of Hif1α knockdown, consistent with a physiologically relevant role of Hif1α in the regulation of telomerase activity levels in these cells.

Fig. 4.

Exposure of Hif1α-targeted mES cells to a hypoxic environment induces Hif1α levels and telomerase levels. (A) Western blot analysis of Hif1α levels in Hif1α-targeted mES cells and control mES cells cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. (Lower) Beta-actin levels are shown as a loading control. (B) Real time RT-PCR analysis of Tert mRNA levels in the mES cells described in A. (C) Telomerase activity levels for the mES cells described in A. For B and C, levels of Tert mRNA and telomerase activity for control samples under normoxic conditions were arbitrarily assigned a value of 1.0. A single asterisk indicates a significant difference in Tert mRNA or telomerase activity for Hif1α-targeted mES cells relative to control mES cells under normoxic conditions, and a double asterisk indicates a significant difference in Tert mRNA or telomerase activity for Hif1α-targeted mES cells grown in hypoxic conditions to the same cells grown in normoxic conditions. Error bars represent SD (n ≥ 4).

Interestingly, hypoxic treatment of Hif1α-targeted mES cells induced up-regulation of both Tert mRNA and telomerase activity even beyond that observed in control mES cells maintained in normoxic conditions, despite apparently higher levels of Hif1α in the latter. This indicates that the hypoxic environment may have other protelomerase effects, via novel mechanisms of Tert and telomerase activation, in addition to Hif1α-mediated transcriptional activation of Tert. Though additional experiments are required to determine the exact mechanism of these other protelomerase effects, they may involve hypoxia-induced up-regulation of the RNA component of telomerase (31), alternative splicing of Tert mRNA to allow synthesis of a more active Tert variant (31), or additional transcriptional activation of Tert via Hif2α (32).

Knockdown of Hif1α Levels in mES Cells Is Accompanied by Attrition of Telomeres.

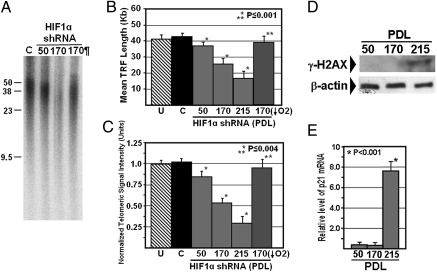

The primary physiological role of telomerase is to maintain or lengthen telomeres, thereby preventing premature senescence of cells that constitute the tissues and organ systems that experience a high rate of cell turnover during development and throughout organismal life. To assess whether the reduced telomerase levels observed in Hif1α-targeted mES cells compromises telomere length maintenance, we measured telomere length by Southern analysis of terminal restriction fragment (TRF) length and slot-blot analysis of total telomeric DNA at early passage [∼50 population doubling level (PDL)] and after extensive culture (∼170 PDL). In contrast to mES cells stably transfected with the nontargeting shRNA vector, we observed gradual attrition of telomere length with increasing passage of Hif1α-targeted mES cells (Fig. 5 A–C). No difference in telomere length was observed between mES cells expressing the nontargeting shRNA and untreated mES cells (Fig. 5 B and C).

Fig. 5.

Targeted knockdown of Hif1α in mES cells causes gradual loss of telomeric DNA and is reversible upon exposure to hypoxic growth conditions. (A) Sample Southern blot showing TRF lengths for control mES cells after 170 population doublings (“C”), and Hif1α-targeted mES cells after 50 and 170 population doublings. Also shown are TRF lengths for Hif1α-targeted ES cells at 170 PDL following culture for 72 h under hypoxic conditions (¶). (B) Quantitative analysis of mean TRF length during long-term culture of Hif1α-targeted mES cells under normoxic conditions. Mean TRF length measurement previously obtained for the untreated Tertp-eGFP mES cells is also shown (“U”). (C) Slot-blot analysis of total telomeric signal intensity during long-term culture of Hif1α-targeted mES cells. For each sample, telomeric signal intensity values are normalized to the c-fos signal intensity. In B and C, the average telomere length measurements for the Hif1α-targeted ES cells (170 PDL) exposed to hypoxic culture conditions are represented by the blue bars. Single asterisk indicates a significant difference from control mES cells, and double asterisk indicates a significant difference from Hif1α-targeted mES cells at 170 PDL cultured under normoxic conditions. Error bars represent SD (n ≥ 3). (D) Western blot analysis of γ-H2AX levels during long-term culture of Hif1α-targeted mES cells. (Lower) Beta-actin levels are shown as a loading control. (E) Real time RT-PCR analysis of p21 mRNA levels during long-term culture of Hif1α-targeted mES cells. The values are shown relative to GAPDH. Asterisk indicates a significant difference in p21 mRNA levels at PDL 215 relative to the average value at earlier passages. Error bars represent SD (n = 3).

Continued long-term culture of Hif1α-targeted mES cells eventually resulted in a marked drop in proliferation rate after ∼215 PDL (Fig. S4), with further shortening of telomeres (Fig. 5 B and C) indicative of telomere-induced senescence. This drop in proliferation rate was not observed during long-term culture of control mES cells (Fig. S4). To more rigorously assess whether cell senescence was occurring, we measured the levels of two established markers of cell senescence, the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 and phosphorylated H2AX (γ-H2AX) (33). Both p21 and γ-H2AX were readily detectible in Hif1α-targeted mES cells after ∼215 PDL, but either absent or present at only negligible levels at 170 PDL or 50 PDL (Fig. 5 D and E), supporting the contribution of telomere-induced senescence to the reduced proliferative rate observed in late passage (∼215 PDL) Hif1α-targeted mES cells.

To assess whether hypoxic activation of Hif1α is sufficient to restore telomere length in Hif1α-targeted mES cells, we cultured Hif1α-targeted mES cells at PDL 170 in a hypoxic environment for 72 h, and assessed telomere length. We observed a marked increase in telomere length in these cells, back to a length that was similar to that observed in the control mES cells (Fig. 5 A–C). These findings are consistent with the hypoxia-induced up-regulation of Tert expression and telomerase activity observed in Hif1α-targeted mES cells (Fig. 4) and argue against any significant role of Hif1α-independent events in the reduced telomerase and telomere length phenotype. Together, these findings show that Hif1α is required for the uncompromised physiological function of telomerase in mES cells.

Discussion

The relatively high level of telomerase activity in stem cells prevents or delays telomere-induced senescence, thereby ensuring long-term replicative capacity of stem cells, particularly in highly proliferative tissues, throughout organismal life. However, the mechanisms that regulate telomerase levels in stem cells are poorly understood at present. In this study, we performed an RNAi screen designed to identify transactivators of the essential telomerase component Tert in murine ES cells. We identified the hypoxia regulatory factor Hif1α as a candidate Tert transactivator in mES cells, and show that targeted knockdown of Hif1α causes a significant reduction in both Tert mRNA levels and telomerase activity levels. Using mutant murine Tert promoter-luciferase reporter constructs, we show that Hif1α plays a direct role in regulating Tert expression in mES cells. Furthermore, long-term proliferation of Hif1α-targeted mES cells was accompanied by the gradual attrition of telomeres, eventually leading to a slowing of proliferation concomitant with the appearance of senescent cells. These effects on Tert expression, telomerase activity, and telomere length are all efficiently reversed upon exposure of Hif1α-targeted mES cells to hypoxia. Together, these findings show that expression Hif1α is required for the uncompromised physiological function of telomerase in mES cells in vitro, and thus illuminate a potential role for Hif1α during early embryonic development—the up-regulation of Tert expression and telomerase activity to promote the enhancement of telomeric reserve.

The essential role of Hif1α in maintenance of telomerase levels via transactivation of Tert expression in mES cells reported here agrees with the Hif1α-dependent activation of telomerase observed in immortal human cell lines and fish cells upon exposure to a hypoxic environment (25–28). These earlier studies further demonstrate that activation of telomerase upon exposure of cells to a hypoxic environment is accompanied by a Hif1α-dependent transactivation of Tert expression (25–28), as we have also observed in mES cells. However, our findings also reveal a unique functional attribute of Hif1α in mES cells—namely, the requirement for maintenance of high levels of telomerase even under normoxic conditions. This is not entirely unexpected, because low levels of Hif1α protein are present in mES cells under normoxic growth conditions, in contrast to other cells (Fig. 3) (34). We hypothesize that the requirement of Hif1α to maintain high levels of telomerase in cultured mES cells likely reflects an activated state of Hif1α in the inner cell mass at the blastocyst stage, and a crucial role for Hif1α in telomerase activation and increase of telomere reserve in the early embryo. Consistent with this hypothesis are the observations that (i) the early embryo is surrounded by a trophoblastic shell and lacks vascularization, and thus exists in a relatively hypoxic environment; (ii) both cultured ES cells and blastocysts have high levels of telomerase activity relative to preimplantation stage embryos (35, 36); and (iii) cloning experiments involving nuclear transfer of nuclei from adult donor somatic cells have shown that both telomerase activity levels and telomere length increase at the blastocyst stage of development in donor-derived embryos (37, 38). Future experiments in mice involving targeted abrogation of the Hif1α-dependent transactivation of Tert expression in the early embryo will allow the definitive testing of this hypothesis.

Though the other candidate Tert transcriptional regulators we identified in this study (Table S1) had additional deleterious effects on mES cells upon shRNA-mediated knockdown, it remains possible that some of these factors may also play a fundamental role in regulating Tert expression in mES cells, in association with other aspects of the mES cell phenotype. In particular, overexpression of c-Myc has previously been shown to be sufficient to transactivate Tert expression and restore telomerase activity in normal human somatic cells lacking telomerase (17). Thus it is possible that c-Myc, which is an established positive regulator of cell proliferation following mitogenic stimulation of various cell types, may couple ES cell proliferation with Tert expression, in addition to other possible functions in ES cells, such as maintenance of ES morphology.

Presently, the mechanisms that promote stabilization or activity of Hif1α in ES cells are not understood. A number of factors have been identified that play a role in regulating Hif1α in cells under normoxic and hypoxic conditions, including the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor, the dioxygenase FIH, the SUMO-conjugating enzyme Ubc9, the SUMO-specific isopeptidase SENP1, and prolyl hyroxylase domain proteins (PHD) (30, 39), all of which could potentially affect Hif1α in ES cells. One intriguing possibility is that cultured ES cells express elevated levels of SENP1, thereby promoting the stabilization of Hif1α under normoxic conditions.

It is important to reconcile the findings reported here, showing a protelomerase role of Hif1α via transcriptional activation of Tert expression, with those of Koshiji et al. (40), who found that Hif1α reduces Tert expression via direct association and inhibition of c-Myc in the human colon carcinoma cell line HCT116. Though the exact reason for these different findings is unknown, it is possible that the effect of Hif1α, via its interactions with c-Myc or otherwise, on telomerase is cell type specific. It is important to note that the inhibitory effect of Hif1α on telomerase observed in HCT116 cells is unlikely to be a common feature of all human tumor cell lines, because Hif1α has been shown to activate Tert expression and telomerase in several other human tumor cell lines (25–27). Together, these findings may have important implications for the potential treatment of different forms of cancer by targeting Hif1α.

In addition to stem cells in the early embryo, Hif1α may also be critical for telomerase regulation in other tissues during development. In particular, it is well established that Hif1α plays an important role in development of the vascular system (41) in early embryos as well as placental development (42). Regarding the latter observation, it has recently been shown that exposure of human trophoblast cell lines to hypoxic growth conditions causes the direct Hif1α-dependent up-regulation of Tert expression and telomerase activity (26). Furthermore, we have recently shown that telomere length in human placenta samples are unusually long relative to cord blood samples from the same donor (43). These findings suggest that Hif1α may also play an important role, via up-regulation of telomerase, in maintaining telomere reserve and preventing premature senescence in these essential tissues, particularly in the embryo.

Recent evidence indicates that the microenvironment for somatic stem cells, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSC), are relatively hypoxic (44), implying that, in addition to ES cells, activation of telomerase in some types of adult somatic stem cells may also be dependent on Hif1α. Telomere length in hematopoietic cells from octogenarians and older individuals are reduced to an average size comparable to that observed in senescent cells (45). Previous studies have also shown that replicative aging of HSC in vivo is accompanied by telomere attrition in mice (5) and humans (46), which likely accounts, at least in part, for the reduced telomere size observed in mature blood cells from the elderly. Thus it is possible that telomere reserve and replicative capacity of hematopoietic cells may potentially be restored via therapies to transiently activate Hif1α in HSC. However, therapies to inhibit Hif1α in tumors may work not only by restricting tumor growth via inhibition of angiogenesis, but may also inhibit telomerase and thereby limit replicative capacity of tumor cells, including cancer stem cells, that reside in hypoxic niches.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture.

Experiments in this study used either the C57BL/6-derived mES cell line SCRC-1002 (ATCC) or the 129/SvJ mES cell line R1. See SI Experimental Procedures for a description of culture conditions.

Vector Constructs and RNAi Screen.

See SI Experimental Procedures for a full description of the Tertp-eGFP reporter construct, the shRNA expression library used in this study, and the screening protocol.

RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis, and Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis.

RNA was isolated and purified from cells using TRIzol reagent and treated with RNase-free DNase I (QIAGEN). Concentration and purity of the extracted RNA were determined using the A260/A280 value measured on an ND1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies). Real-time RT-PCR analysis of gene expression was performed as described (47).

Immunoblot Assay.

See SI Experimental Procedures for a description of the immunoblotting procedure.

TRAP Assays.

Telomerase activity was quantitatively assessed by the telomere repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assay using the TRAPeze telomerase detection kit (Chemicon) as described (47).

Southern Analysis of Telomere Length.

Telomere length was measured by Southern analysis of terminal restriction fragment (TRF) length using field inversion gel electrophoresis (FIGE) described (5, 45).

Slot-Blot Analysis of Total Telomeric DNA.

Slot-blot analysis of total telomeric DNA was performed as described (48).

Luciferase Reporter Assay.

The dual luciferase reporter assay (Promega) was used to measure luciferase activity. Reporter constructs were introduced into mES cells by transfection using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). All luciferase activity measurements were taken 48 h posttransfection using a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner BioSystems Inc.).

Statistical Analysis.

All two-group statistical comparisons of means were calculated with Student's t test using Excel spreadsheet. For all tests, statistical significance was established at P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prerna Prasad and Alex Gurary for excellent experimental assistance, and Lea Harrington for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P20 RR16467 and the Tilker Medical Research Foundation (R.A.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.0913834107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1961;25:585–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson JA, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison DE, Astle CM. Loss of stem cell repopulating ability upon transplantation. Effects of donor age, cell number, and transplantation procedure. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1767–1779. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.6.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allsopp RC, Cheshier S, Weissman IL. Telomere shortening accompanies increased cell cycle activity during serial transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193:917–924. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan SR, Blackburn EH. Telomeres and telomerase. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:109–121. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature. 1990;345:458–460. doi: 10.1038/345458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hastie ND, et al. Telomere reduction in human colorectal carcinoma and with ageing. Nature. 1990;346:866–868. doi: 10.1038/346866a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemann MT, Strong MA, Hao LY, Greider CW. The shortest telomere, not average telomere length, is critical for cell viability and chromosome stability. Cell. 2001;107:67–77. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura TM, et al. Telomerase catalytic subunit homologs from fission yeast and human. Science. 1997;277:955–959. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodnar AG, et al. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science. 1998;279:349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolquist KA, et al. Expression of TERT in early premalignant lesions and a subset of cells in normal tissues. Nat Genet. 1998;19:182–186. doi: 10.1038/554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee HW, et al. Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature. 1998;392:569–574. doi: 10.1038/33345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allsopp RC, Morin GB, DePinho R, Harley CB, Weissman IL. Telomerase is required to slow telomere shortening and extend replicative lifespan of HSCs during serial transplantation. Blood. 2003;102:517–520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenwood MJ, Lansdorp PM. Telomeres, telomerase, and hematopoietic stem cell biology. Arch Med Res. 2003;34:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegl-Cachedenier I, Flores I, Klatt P, Blasco MA. Telomerase reverses epidermal hair follicle stem cell defects and loss of long-term survival associated with critically short telomeres. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:277–290. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Xie LY, Allan S, Beach D, Hannon GJ. Myc activates telomerase. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1769–1774. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takakura M, Kyo S, Inoue M, Wright WE, Shay JW. Function of AP-1 in transcription of the telomerase reverse transcriptase gene (TERT) in human and mouse cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8037–8043. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8037-8043.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paddison PJ, et al. A resource for large-scale RNA-interference-based screens in mammals. Nature. 2004;428:427–431. doi: 10.1038/nature02370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carmell MA, Zhang L, Conklin DS, Hannon GJ, Rosenquist TA. Germline transmission of RNAi in mice. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:91–92. doi: 10.1038/nsb896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holt SE, Wright WE, Shay JW. Regulation of telomerase activity in immortal cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2932–2939. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchkovich KJ, Greider CW. Telomerase regulation during entry into the cell cycle in normal human T cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1443–1454. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.9.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Rourke JF, et al. Hypoxia response elements. Oncol Res. 1997;9:327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nozawa K, Maehara K, Isobe K. Mechanism for the reduction of telomerase expression during muscle cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22016–22023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seimiya H, et al. Hypoxia up-regulates telomerase activity via mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in human solid tumor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:365–370. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishi H, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 mediates upregulation of telomerase (hTERT) Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6076–6083. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.6076-6083.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yatabe N, et al. HIF-1-mediated activation of telomerase in cervical cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:3708–3715. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu RM, et al. Hypoxia induces telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) gene expression in non-tumor fish tissues in vivo: The marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) model. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7:27–34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forsythe JA, et al. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4604–4613. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ulrich HD. SUMO teams up with ubiquitin to manage hypoxia. Cell. 2007;131:446–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson CJ, Hoare SF, Ashcroft M, Bilsland AE, Keith WN. Hypoxic regulation of telomerase gene expression by transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Oncogene. 2006;25:61–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lou F, et al. The opposing effect of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha on expression of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:793–800. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.d'Adda di Fagagna F, et al. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature. 2003;426:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nature02118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iyer NV, et al. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes Dev. 1998;12:149–162. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright DL, et al. Characterization of telomerase activity in the human oocyte and preimplantation embryo. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:947–955. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.10.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J, Yang X. Telomerase activity in early bovine embryos derived from parthenogenetic activation and nuclear transfer. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1124–1128. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.3.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaetzlein S, et al. Telomere length is reset during early mammalian embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8034–8038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402400101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu J, Yang X. Telomerase activity in early bovine embryos derived from parthenogenetic activation and nuclear transfer. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:770–774. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.3.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng J, Kang X, Zhang S, Yeh ETH. SUMO-specific protease 1 is essential for stabilization of HIF1alpha during hypoxia. Cell. 2007;131:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koshiji M, et al. HIF-1alpha induces cell cycle arrest by functionally counteracting Myc. EMBO J. 2004;23:1949–1956. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramírez-Bergeron DL, Runge A, Adelman DM, Gohil M, Simon MC. HIF-dependent hematopoietic factors regulate the development of the embryonic vasculature. Dev Cell. 2006;11:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodesch F, Simon P, Donner C, Jauniaux E. Oxygen measurements in endometrial and trophoblastic tissues during early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:283–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allsopp R, Shimoda J, Easa D, Ward K. Long telomeres in the mature human placenta. Placenta. 2007;28:324–327. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parmar K, Mauch P, Vergilio JA, Sackstein R, Down JD. Distribution of hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow according to regional hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5431–5436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701152104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaziri H, et al. Loss of telomeric DNA during aging of normal and trisomy 21 human lymphocytes. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:661–667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaziri H, et al. Evidence for a mitotic clock in human hematopoietic stem cells: Loss of telomeric DNA with age. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9857–9860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coussens M, et al. Regulation and effects of modulation of telomerase reverse transcriptase expression in primordial germ cells during development. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:785–791. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.052167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allsopp RC, Harley CB. Evidence for a critical telomere length in senescent human fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1995;219:130–136. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.