Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) represents the leading cause of mortality worldwide. Lifestyle modifications, along with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) reduction, remain the highest priorities in CVD risk management. Among lipid-lowering agents, statins are most effective in LDL-C reduction and have demonstrated incremental benefits in CVD risk reduction. However, in light of the residual CVD risk, even after LDL-C targets are achieved, there is an unmet clinical need for additional measures. Fibrates are well known for their beneficial effects in triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and LDL-C subspecies modulation. Fenofibrate is the most commonly used fibric acid derivative, exerts beneficial effects in several lipid and nonlipid parameters, and is considered the most suitable fibrate to combine with a statin. However, in clinical practice this combination raises concerns about safety. ABT-335 (fenofibric acid, Trilipix®) is the newest formulation designed to overcome the drawbacks of older fibrates, particularly in terms of pharmacokinetic properties. It has been extensively evaluated both as monotherapy and in combination with atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin in a large number of patients with mixed dyslipidemia for up to 2 years and appears to be a safe and effective option in the management of dyslipidemia.

Keywords: atherogenic dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease prevention, lipid-lowering treatment, fenofibric acid, statins

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) constitutes the leading cause of death in developed countries. Current treatment guidelines focus on lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) as the primary strategy for reducing CVD risk (Table 1).1–5 Hydroxymethyl-glutamyl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (HMG-CoA) or statins have demonstrated a significant CVD risk reduction in a large number of landmark trials.6 There is growing evidence that both diabetic and nondiabetic patients are still at risk for CVD events even if they are receiving optimal statin treatment (termed as “residual CVD risk”). In the Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy – Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (PROVE IT-TIMI) 22 study, 4162 patients with acute coronary syndromes were treated with either pravastatin 40 mg or atorvastatin 80 mg. A substantial number of patients (10%) died from CVD events within 30 months, despite having LDL-C levels below 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L).7 Similar were the findings in the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study, where the level of residual CVD risk remained high in patients treated with atorvastatin 10 mg/dL or 80 mg/dL.8,9 This residual CVD risk seems to depend at least partly on increased levels of triglycerides (TG) and decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). Recent data indicate that up to 50% of patients treated with a statin who have achieved LDL-C target levels have low HDL-C levels.10,11 In addition, based on current data, increased TG is nowadays considered to be a significant CVD risk factor.12

Table 1.

Treatment targets for total cholesterol, LDL-C, and non-HDL-C, and cutoff values for triglycerides and HDL-C in the NCEP and ESC guidelines

|

Total cholesterol |

LDL-C |

non-HDL-Ca |

Triglyceridesb |

HDL-Cb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/dL | mmol/L | mg/dL | mmol/L | mg/dL | mmol/L | mg/dL | mmol/L | mg/dL | mmol/L | |

| NCEP guidelines1,4 | ||||||||||

| General population | 150 | 1.7 | 40 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 0 or 1 RF | 160 | 4.1 | 190 | 4.9 | ||||||

| More than 2 RF or CAD event risk <20% | 130 | 3.4 | 160 | 4.1 | ||||||

| CAD or risk equivalent1 | 100 | 2.6 | 130 | 3.4 | ||||||

| Optional in very high risk | 70 | 1.8 | 100 | 2.6 | ||||||

| ESC guidelines5 | ||||||||||

| General population | 190 | 4.9 | 115 | 3.0 | 150 | 1.7 | 40 (M) | 1.0 (M) | ||

| 45 (w) | 1.2 (w) | |||||||||

| CAD, CVD or DM | 175 | 4.5 | 100 | 2.6 | ||||||

| Optional | 155 | 4.0 | 80 | 2.1 | ||||||

Notes:

In the fasting state, non-HDL-C is calculated by subtracting HDL-C from total cholesterol and serves as a secondary target of therapy in patients with elevated triglycerides (>200 mg/dL, 2.26 mmol/L);

No specific treatment goals are defined for HDL-C and fasting TG, but these concentrations serve as markers of increased CVD risk;

Defined as other clinical forms of atherosclerotic disease, diabetes mellitus, or a 10-year risk for CAD greater than 20%.

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; M, men; NCEP, National Cholesterol Education Program; RF, risk factor; W, women.

The National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) recognized both low HDL-C (<40 mg/dL [1.03 mmol/L] for men, <50 mg/dL [1.29 mmol/L] for women) and elevated TG levels (≥150 mg/dL [1.69 mmol/L]) as markers of increased CVD risk, independently of LDL-C levels.1 Mixed dyslipidemia, which is characterized by elevated TG (≥50 mg/dL [1.69 mmol/L]) and low HDL-C levels (<40 mg/dL [1.03 mmol/L] for men, <50 mg/dL [1.29 mmol/L] for women) with or without increased LDL-C, apolipoprotein (apo) B or non-HDL-C levels is typical in patients with type 2 diabetes and/or the metabolic syndrome.1,2,13 Mixed dyslipidemia is also characterized by an altered LDL subfraction profile with a preponderance of small dense LDL-C particles.14 Small dense LDL-C particles are considered to be highly atherogenic.2,15 Statins reduce LDL-C levels effectively, but they manifest limited effects on TG and HDL-C levels, as well as on LDL-C particle size modification, especially in patients with mixed dyslipidemia. There is accumulating evidence suggesting that treatment of patients with increased CVD risk, the metabolic syndrome, or diabetes should be oriented not only against decreasing LDL-C, but also raising HDL-C levels.16,17 It becomes apparent that agents effective against these components of atherogenic dyslipidemia have an intriguing role to play in CVD risk reduction.18,19 However, there is no overwhelming evidence that treating these targets will alter major CVD outcomes. Furthermore, specific treatment goals for non-LDL parameters are not currently defined.

Forty years since the introduction of the first fibrate in clinical practice, the exact role of these pharmacologic compounds remains ill-defined.20 Fenofibrate is one of the most commonly prescribed lipid-lowering agents in the world. Trilipix® (fenofibric acid, ABT-335), is the newest formulation of a fibric acid derivative approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).21

Both statins and fibrates have favorable effects on several lipid and nonlipid parameters.22,23 Combining a statin with a fibrate may have a global beneficial effect because these two groups of pharmacologic agents differ in a substantial number of lipid and nonlipid parameters, and may in fact act in a complementary fashion.23,24 Updated guidelines from the NCEP ATP III recognize the potential beneficial effects of fibrates used in combination with a statin in patients with mixed dyslipidemia and coronary heart disease (CHD) or CHD risk equivalents.25

Aspects of pharmacology

Fenofibrate chemically is a 2-[4[(4-chlorobenzoyl)phenoxy]-2-methyl-propanoic acid, 1-methylethyl ester. Hydrolysis of the ester bond converts fenofibrate to its active form, namely fenofibric acid.26 Fenofibrate is a lipophilic compound, and its absolute bioavailability is hard to estimate because it is highly insoluble in water. It is highly protein bound (99%), primarily to albumin.26,27 Under normal conditions no unmodified fenofibrate is found in plasma.28 Plasma levels peak in six to eight hours, while steady-state plasma levels are reached within 5 days. Its absorption is increased with meals, and the half-life is 16 hours.26,27,29

Fenofibric acid is inactivated by UDP-glucuronyltranferase into fenofibric acid glucuronide,30 and is mainly excreted in urine (60%) as fenofibric acid and fenofibric acid glucuronide (ester glucuronidation takes place in hepatic and renal tissues).26 As a result, fenofibric acid may accumulate in severe kidney disease (creatinine clearance, [CrCl] < 30 mL/min),28,31 and is not eliminated by hemodialysis.31

Since the initial introduction of a fenofibrate in clinical practice, several other formulations have been developed in order to optimize its pharmacologic properties. The major drawbacks of the original fenofibrate formulation were its low availability and the necessitation of taking it with meals, especially fat meals. The new formulation is Trilipix (also known as fenofibric acid delayed-release or choline fenofibrate) which is the choline salt of fenofibrate. Trilipix does not require enzymatic cleavage to become active. It rapidly dissociates to the active form of free fenofibric acid within the gastrointestinal tract and does not undergo first-pass hepatic metabolism.21

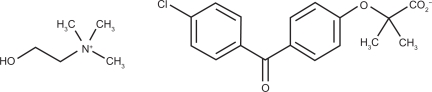

Trilipix is manufactured as delayed-release 45 mg and 135 mg capsules. The chemical name for choline fenofibrate is ethanaminium, 2-hydroxy-N,N,N-trimethyl, 2-{4-(4-chlorobenzoyl)phenoxy] -2-methylpropanoate (1:1)32 (see Figure 1). It is freely soluble in water. Trilipix delayed-release capsules can be taken without regard to meals. Of great importance, fenofibric acid is well absorbed throughout the gastrointestinal tract, and has statistically greater bioavailability than prior fenofibrate formulations, as has been demonstrated in healthy human volunteers.33

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of ABT-335. The chemical name for choline fenofibrate is ethanaminium, 2-hydroxy-N,N,Ntrimethyl, 2-{4-(4-chlorobenzoyl)phenoxy]-2-methylpropanoate. The empirical formula is C22H28ClNO5 and the molecular weight is 421.91.

Pharmacokinetics

Fenofibric acid is the circulating pharmacologically active moiety in plasma after oral administration of Trilipix. Fenofibric acid is also the circulating pharmacologically active moiety in plasma after oral administration of fenofibrate, the ester of fenofibric acid. Plasma concentrations of fenofibric acid after one 135 mg delayed-release capsule are equivalent to those after one 200 mg capsule of micronized fenofibrate administered under fed conditions.

Absorption

Fenofibric acid is well absorbed throughout the gastrointestinal tract. The absolute bioavailability of fenofibric acid is approximately 81%. The absolute bioavailability in the stomach, proximal small bowel, distal small bowel, and colon has been shown to be approximately 81%, 88%, 84%, and 78%, respectively, for fenofibric acid and 69%, 73%, 66%, and 22%, respectively, for fenofibrate (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.033 for fenofibric acid versus fenofibrate in the colon and distal small bowel, respectively).33 Fenofibric acid exposure in plasma, as measured by time to peak concentration in plasma and area under the concentration curve (AUC), is not significantly different when a single 135 mg dose of Trilipix is administered under fasting or nonfasting conditions.34

Distribution

Upon multiple dosing of Trilipix, fenofibric acid levels reach steady state within 8 days.34 Plasma concentrations of fenofibric acid at steady state are approximately slightly more than double those following a single dose.

Metabolism

Fenofibric acid is primarily conjugated with glucuronic acid and then excreted in urine. A small amount of fenofibric acid is reduced at the carbonyl moiety to a benzhydrol metabolite which is, in turn, conjugated with glucuronic acid and excreted in urine.34 In vivo metabolism data after fenofibrate administration indicate that fenofibric acid does not undergo oxidative metabolism, eg, by cytochrome (CYP) P450, to a significant extent.

Elimination

After absorption, Trilipix is primarily excreted in the urine in the form of fenofibric acid and fenofibric acid glucuronide. Fenofibric acid is eliminated with a half-life of approximately 20 hours,34 allowing once-daily administration of Trilipix.

Use in specific populations

In five elderly volunteers aged 77–87 years, the oral clearance of fenofibric acid following a single oral dose of fenofibrate was 1.2 L/hour, which compares with 1.1 L/hour in young adults. This indicates that an equivalent dose of fenofibric acid tablets can be used in elderly subjects with normal renal function, without increasing accumulation of the drug or metabolites. Trilipix has not been investigated in well-controlled trials in pediatric patients. No pharmacokinetic difference between males and females has been observed for Trilipix. The influence of race on the pharmacokinetics of Trilipix has not been studied.

The pharmacokinetics of fenofibric acid were examined in patients with mild, moderate, and severe renal impairment. Patients with severe renal impairment (CrCl < 30 mL/min showed a 2.7-fold increase in exposure to fenofibric acid and increased accumulation of fenofibric acid during chronic dosing compared with healthy subjects.30 Patients with mild-to-moderate renal impairment (CrCl 30–80 mL/min) had similar exposure but an increase in the half-life for fenofibric acid compared with that in healthy subjects. Based on these findings, the use of Trilipix should be avoided in patients who have severe renal impairment, and dose reduction is required in patients having mild to moderate renal impairment. No pharmacokinetic studies have been conducted in patients with hepatic impairment.

Drug–drug interactions

In vitro studies using human liver microsomes indicate that fenofibric acid is not an inhibitor of CYP P450 isoforms CYP3A4, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, or CYP1A2. It is a weak inhibitor of CYP2C8, CYP2C19, and CYP2A6, and a mild-to-moderate inhibitor of CYP2C9 at therapeutic concentrations.34,35 Accordingly, fenofibric acid may have the potential to cause various pharmacokinetic drug interactions.

Since they are highly protein-bound, all fibric acid derivatives may increase the anticoagulant effect of coumarin derivatives. Serial monitoring of the International Normalized Ratio should be performed. Caution should be exercised when drugs that are highly protein-bound are given concomitantly with fenofibrate.36

Interaction with cyclosporine has been reported to increase the risk of nephrotoxicity, myositis, and rhabdomyolysis, partly due to the fact that both are metabolized through CYP 3A4.37 Careful consideration should be given when fenofibric acid is administered with other potential nephrotoxic drugs and, if necessary, lower doses of fenofibric acid may be used.21

Bile acid sequestrants may decrease the absorption of fenofibrate and therefore the bioavailability of fenofibric acid. It is recommended that fenofibrate be taken at least one hour before or 4–6 hours after bile acid resins.21

Concerning the pharmacokinetic interactions between fenofibric acid and statins, no clinically significant pharmacokinetic drug interaction between fenofibrate simvastatin, pravastatin, atorvastatin, and rosuvastatin has been observed in humans.38–41 Not all fibrates share the same pharmacokinetic properties. In vitro studies have demonstrated that gemfibrozil interacts with the same family of glucuronidation enzymes involved in statin metabolism.35 As a result of inhibiting statin glucuronidation, gemfibrozil coadministration with statins generally produces increases in the statin AUC. Gemfibrozil is also an inducer of CYP3A4, but acts as both an inducer and an inhibitor of CYP2C8.35 In contrast, fenofibrate is metabolized by different glucuronidation enzymes and as a result, does not lead to pharmacokinetic interactions with statins in a clinically relevant way.35

Mode of action

Effects on lipids

Fenofibric acid derivatives exert their primary effects on lipid metabolism via the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPAR-α) by the active fenofibric acid. Several target genes modulating lipid metabolism are encoded through the activation of these receptors.42,43 Fenofibrate affects the metabolism of TG and HDL-C through several pathways.

Fenofibrate is able to reduce plasma TG levels by inhibiting their synthesis and stimulating their clearance. Primarily, fenofibrate induces fatty acid β-oxidation and, in this way, the availability of fatty acids for very LDL-C (VLDL-C) synthesis and secretion is reduced.44,45 Furthermore, it augments the activity of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity, which hydrolyzes TG on several lipoproteins.46

Apo C proteins are crucial for TG metabolism. Apo C III delays catabolism of TG-rich lipoproteins by inhibiting their binding to the endothelial surface and subsequent lipolysis by LPL. Fenofibrate decreases both apo C II and apo C III expression in the liver via PPAR-α activation.47–50 Apo C III reductions have also been shown to be the only significant and independent predictor of fenofibrate-induced TG alterations in obese patients with the metabolic syndrome.51

Apart from TG reduction, fenofibrate is well known for its favorable actions on HDL-C levels. The fundamental action of fenofibrate is the promotion of apo A I and II synthesis in the liver, which represent the main HDL-C apoproteins.52 Fenofibrate modifies HDL and the reverse cholesterol transport pathway through several mechanisms. Specifically, fenofibrate is able to increase pre-β1-HDL-C levels in patients with the metabolic syndrome,53 reduce total plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein activity,54,55 induce the activity of adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter (ABCA1,56,57 member 1 of the human transporter subfamily ABCA), also known as the cholesterol efflux regulatory protein (CERP), and induce hepatic lipase activity.46

Some recent clinical reports have suggested that HDL-C levels may be paradoxically decreased after fenofibrate treatment.58,59 This appears to occur mainly in patients with combined fibrate plus statin therapy and possibly in those with low baseline HDL-C. A survey of 581 patients treated with the combination for 1 year or longer indicated that paradoxical HDL-C reductions are a relatively uncommon phenomenon.59 Approximately 15% of patients showed modest reduction in HDL-C levels. These reductions in HDL-C occurred mainly in individuals with significant HDL-C elevations (ie, >50 mg/dL, 1.3 mmol/L) and almost never in patients with low HDL-C. There was no impact of a previous diagnosis of diabetes or hypertension on the HDL-C changes.59

In addition, fibrates have been shown to decrease cholesterol synthesis by inhibiting hydroxymethylglutamyl-coenzyme A reductase and to increase cholesterol excretion in the bile pool.55,60,61 Fenofibrate is able to reduce apo B levels, primarily as a result of reduced synthesis and secretion of TG, and not by directly influencing apo B production.45

Effects on nonlipid parameters

Fenofibrate has beneficial effects on several nonlipid parameters which are independent of its action on lipoproteins.62 As widely known, fibrates reduce fibrinogen levels. Fenofibric acid has been shown to inhibit plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and tissue factor expression on endothelial cells and macrophages.63 Fenofibrate also modulates platelet aggregation and endothelial dysfunction, via an incompletely elucidated molecular mechanism.64,65

Significant reductions in serum high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels have been observed with fenofibrate treatment.63,66 Fenofibrate effectively decreases serum interleu-kin-6 levels, as well as plasma platelet-activating factor acetylohydrolase, which represents a novel inflammatory marker.66,67

Of importance, fenofibrate can significantly decrease serum uric acid levels by increasing renal urate expression, and considerable reductions in serum alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyltransferase activity are commonly observed during therapy with fenofibrate.63,68 The latter effects may have an application in patients with liver diseases, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Recent reports have stressed the role of fenofibrate in glucose and carbohydrate metabolism. However, this issue remains controversial, with some studies demonstrating beneficial effects on insulin secretion51,66 and others showing no effect.69

Studies evaluating the efficacy of fenofibrate

Fenofibrate as monotherapy

Fenofibrate is indicated for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia, combined dyslipidemia, remnant hyperlipidemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and mixed hyperlipidemia (Frederickson types IIa, IIb, III, IV, and V, respectively).

Fenofibrate as monotherapy decreases serum TG levels by 20%–50% and increases HDL-C levels by 10%–50%.48,70,71 The rise in HDL-C levels depends on baseline HDL-C concentrations, with the greatest elevations observed when baseline HDL-C is <39 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L).72 It also decreases LDL-C levels by 5%–20%.73 LDL-C response is directly related to baseline LDL-C levels and inversely related to baseline TG levels.73 In clinical practice, TG reduction is greater in hypertriglyceridemia phenotypes (up to 50%) and lower in Type IIa hypercholesterolemia (<30%). Fenofibrate also exerts beneficial effects on several apolipoprotein levels. Apo A I and apo A II levels are significantly increased, while apo C III and apo B levels are reduced.48

Fenofibrate has been shown to modify favorably both LDL and HDL subclass distributions. Treatment with fenofibrate shifts the ratio of LDL-C particle subspecies from small, dense, atherogenic LDL particles (LDL 4 and LDL 5) to large, buoyant ones (LDL 3).54 These larger, less dense LDL particles show higher affinity for the LDL receptor, while an association between small dense LDL and increased CVD risk has long been established. In addition, fenofibrate is able to alter HDL particle size.54 The HDL-C rise is accompanied with a shift of HDL from large to small particles.48,53,54,74–76 The antiatherogenic, antioxidative, and antiapoptotic properties of HDL have been attributed mainly to its small subfractions.77,78 Furthermore, plasma levels of small HDL subclasses has been shown to be a strong predictor of protection against atherosclerosis.79,80

Several large clinical and angiographic trials have evaluated the efficacy of fibrates as monotherapy in halting the progression of atherosclerotic disease (Table 2).81–85 The Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) study was a 5-year, randomized, placebo-controlled trial testing the safety and efficacy of fenofibrate 200 mg in 9795 type 2 diabetic patients.86 The primary endpoint was CHD death or nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI). Fenofibrate failed to alter the primary endpoint significantly. However, fenofibrate reduced the composite of CVD death, MI, stroke, and coronary or carotid revascularization by 11% (P = 0.035). Interestingly, in this study, fenofibrate significantly reduced the need for retinal laser therapy (by 30%, P < 0.001), the rate of nontraumatic amputation (by 38%, P = 0.011), and the progression of albuminuria (P < 0.002). Of note, only 21% of the patients enrolled had mixed dyslipidemia (TG ≥ 200 mg/dL [2.25 mmol/L] and HDL-C < 40 mg/dL [1.03 mmol/L] for men and <50 mg/dL [1.29 mmol/L] for women). Fenofibrate decreased TG and LDL-C moderately (by 29% and 12%, respectively) and increased HDL-C by 5% at 4 months.86 Using the NCEP ATP III definition of metabolic syndrome, more than 80% of FIELD participants qualified as having the condition.87 Each feature of metabolic syndrome, excluding increased waist circumference, was associated with an increase in the absolute 5-year risk for CVD events by at least 3%. Marked dyslipidemia (defined as elevated triglycerides ≥2.3 mmol/L and low HDL-C) was associated with the highest risk of CVD events (17.8%). The largest effect of fenofibrate on CVD risk reduction was observed in subjects with marked dyslipidemia, in whom a 27% relative risk reduction (95% confidence interval [CI] 9%–42%, P = 0.005; number needed to treat = 23) was observed.87

Table 2.

Major clinical and angiographic trials with fibrates

| Study | Patients | Duration | Fibrate | Comparator | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helsinki heart study81 | 4081 male patients (40–55 years) with primary dyslipidemia and non-HDL-C levels > 200 mg/dL (5.17 mmol/L) | 5 years | Gemfibrozil 1200 mg daily | Placebo | 34% decrease in fatal and nonfatal MI (95% CI 8.2–52.6, P < 0.02) |

| Bezafibrate coronary atherosclerosis intervention study83 | 92 post-MI patients < 45 years | 5 years | Bezafibrate 200 mg (3 times daily) | Placebo | Less disease progression in focal lesions as assessed coronary angiograms in segments with <50% diameter stenosis at baseline |

| LOPID coronary angiography trial82 | 395 post-coronary bypass men ≤ 70 years with HDL-C < 42.46 mg/dL (1.1 mmol/L) and LDL-C ≤ 170 mg/dL (4.5 mmol/L) | 32 months | Gemfibrozil 1200 mg daily | Placebo | Decrease in rate of change in native coronary segments and minimum luminal diameter, and new lesions (2% for gemfibrozil vs 14% for placebo, P < 0.001) |

| Bezafibrate infarction prevention study85 | 3090 patients (45–74 years) with CHD | 6.2 years | Bezafibrate 400 mg daily | Placebo | Decrease by 9% in fatal and nonfatal MI and sudden death (nonsignificant vs placebo) |

| Veterans affairs high-density lipoprotein cholesterol intervention study84 | 2531 patients (<74 years) with CHD and HDL-C < 39 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) | 5.1 years | Gemfibrozil 1200 mg daily | Placebo | Decrease by 24% in composite of CHD death, nonfatal MI, stroke; by 24% in CVD events; by 25% in stroke, and by 22% in CHD death |

| Diabetes atherosclerosis intervention study88 | 418 patients aged 40–65 years with DM and TC/HDL-C <4 or LDL-C < 170 mg/dL (4.5 mmol/L) or LDL-C 135–170 mg/dL (3.5–4.5 mmol/L) and TG ≤ 495 mg/dL (5.2 mmol/L) | 3 years | Fenofibrate 200 mg daily | Placebo | 40% decrease in minimum lumen diameter (P = 0.029 vs placebo); 42% decrease in progression in percentage diameter stenosis (P = 0.02 vs placebo) |

| Fenofibrate intervention and event lowering in diabetes (FIELD) study86 | 9795 patients with type 2 diabetes, 50–75 years, (2131 patients with documented CVD) | 5 years | Fenofibrate 200 mg daily | Placebo | 24% decrease in nonfatal MI (P = 0.01 vs placebo); 11% decrease in total CVD (P = 0.04 vs placebo) |

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

In the earlier Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study (DAIS) study, 418 type 2 diabetic patients were enrolled (baseline lipid profile: LDL-C 132 mg/dL [3.4 mmol/L]; TG 221 mg/dL [2.49 mmol/L]; and HDL-C 40 mg/dL [1.03 mmol/L]). DAIS was a 3-year, randomized, placebo-controlled angiographic trial.88 Fenofibrate slowed the angiographic progression of coronary atherosclerosis, along with considerable improvement in the lipid profile (LDL-C reduction by 6%, TG reduction by 28%, and HDL-C increase by 7%). Fenofibrate decreased the progression of focal coronary atheroma by 40% versus placebo. Additionally, fenofibrate decreased the incidence of microalbuminuria by 54%.

Fibrate and statin combination therapy

It is well accepted that statins are the primary and more efficient method of reducing LDL-C levels even at low doses.89 However, statins manifest minimal effects in raising HDL-C levels (5%–15%) and in decreasing TG levels (7%–30%).19 Fenofibrate has small or minimal effects on LDL-C levels, which depends on baseline TG levels.89 These data imply that a combination of a statin and a fibrate may have additional benefits, especially in patients with mixed dyslipidemia.

Combining fenofibrate with a statin appeared to be safe and effective in several short-term studies (Table 3).76,90–94 The combination of fenofibrate with a statin, along with better improvements in lipid profile, has been shown to induce a marked increase in the ratio of large to small LDL subspecies compared with statin monotherapy.75,95

Table 3.

Trials evaluating combination therapy of fenofibrate with a statin

| Study | Patients | N | Duration | Comparator | Combination arm | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grundy et al76 | Mixed dyslipidemia | 619 | 12 weeks | Simvastatin 20 mg | Fenofibrate 160 mg + simvastatin 20 mg | Fenofibrate + simvastatin vs simvastatin:

|

| Vega et al95 | Mixed dyslipidemia + Metabolic syndrome | 20 | 3 months | a) Simvastatin 10 mg + placebo b) Placebo + placebo |

Fenofibrate 200 mg + simvastatin 10 mg | Fenofibrate + simvastatin vs simvastatin + placebo:

|

| Kiortisis et al92 | Mixed lipid disorders | 12 | 18 weeks | 6 weeks on fenofibrate 200 mg/day, then 6 weeks on atorvastatin 40 mg/day, then combination treatment with atorvastatin 40 mg + fenofibrate 200 mg | Atorvastatin 40 mg + fenofibrate 200 mg | Fenofibrate + atorvastatin vs atorvastatin vs fenofibrate:

|

| Ellen and McPherson90 | Mixed dyslipidemia + CHD | 80 | 2 years | a) Addition of Fenofibrate 200 or 300 mg to pravastatin 20 mg (N =63) b) Addition of Fenofibrate 200 or 300 mg to simvastatin 10 (N = 17) |

Combination vs baseline:

|

|

| Athyros et al91 | Type 2 diabetic patients + mixed dyslipidemia | 120 | 24 weeks | a) Atorvastatin 20 mg b) Fenofibrate 200 mg |

Fenofibrate 200 mg + atorvastatin 20 mg | Fenofibrate + atorvastatin vs atorvastatin:

|

| Derosa et al94 | Type 2 diabetic patients with mixed dyslipidemia and CHD | 48 | 12 months | Fluvastatin 80 mg + placebo | Fenofibrate 200 mg + fluvastatin 80 mg | Fenofibrate + fluvastatin vs fluvastatin + placebo

|

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL-c, high density cholesterol; LDL-c, low density cholesterol; T-c, total cholesterol, TG, triglycerides; apo, apolipoprotein.

Long-term, placebo-controlled trials with the combination of a fibrate and a statin with hard CVD outcomes are lacking. In the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) Lipid study, researchers evaluated whether adding fenofibrate to statin therapy prevents adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes.96 A total of 5518 diabetic patients (mean age, 62 years; 31% women; glycosylated hemoglobin ≥ 7.5%; LDL-C 60–180 mg/dL [1.55–4.65 mmol/L]; HDL-C < 55 mg/dL [1.42 mmol/L] for women and blacks and <50 mg/dL [1.29 mmol/L] for all other groups) were enrolled. All participants received simvastatin 20–40 mg/day and also were assigned to daily fenofibrate 160 mg or placebo. Mean follow-up was 4.7 years. Participants were also randomized to either intensive or standard glycemic control and to either intensive or standard blood pressure control. Glycemic control in the ACCORD study was stopped early in February 2008 because of higher mortality in the intensive glycemic control group. All patients were then transferred to a standard glycemic control regimen.

In both groups, mean LDL-C levels dropped from 100.0 mg/dL (2.59 mmol/L) to about 80.0 mg/dL (2.07 mmol/L). Mean HDL-C levels increased from 38.0 mg/dL (0.98 mmol/L) to 41.2 mg/dL (1.07 mmol/L) in the fenofibrate group and to 40.5 mg/dL (1.05 mmol/L) in the placebo group. Median TG levels decreased from about 189 mg/dL (2.13 mmol/L) to 147 mg/dL (1.66 mmol/L) in the fenofibrate group and to 170 mg/dL (1.92 mmol/L) in the placebo group.96 The primary endpoint, adverse (major fatal or nonfatal) cardiovascular events, occurred with similar frequency in the two groups (2.2% versus 2.4% per year; hazard ratio 0.92; P = 0.32).96 Among the secondary endpoints, there was also no statistically significant difference between the two treatments. No subgroup analysis was strongly positive. Only gender showed evidence of an interaction according to study group. The primary outcome for men was 11.2% in the fenofibrate group versus 13.3% in the placebo group, whereas the rate for women was 9.1% in the fenofibrate group versus 6.6% in the placebo group (P = 0.01 for interaction). A possible benefit was also suggested for patients who had a TG level in the highest third (≥204 mg/dL [≥2.30 mmol/L]) and an HDL-C in the lowest third (≤34 mg/dL [≤0.88 mmol/L]). The primary outcome rate was 12.4% in the fenofibrate group versus 17.3% in the placebo group, whereas such rates were 10.1% in both study groups for all other patients (P = 0.057 for interaction). Although patients receiving fenofibrate had higher rates of treatment discontinuation due to an increase in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), a lower incidence of both microalbuminuria (38.2% versus 41.6, P = 0.01) and macroalbuminuria (10.5% versus 12.3%, P = 0.03) was noted in the fenofibrate group compared with the placebo group.96

Trilipix (ABT-335, fenofibric acid) clinical studies

The efficacy and safety of Trilipix has been evaluated in a large well-designed Phase III clinical program in approximately 2400 patients. Inclusion criteria consisted of elevated TG (≥ 150 mg/dL or 1.69 mmol/L), decreased HDL-C levels (<40 mg/dL or 1.03 mmol/L for men and <50 mg/dL or 1.29 mmol/L for women), and elevated LDL-C levels (≥130 mg/dL or 3.36 mmol/L). Trilipix 135 mg was compared as monotherapy and as combination therapy with three different statins (atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin). Primary efficacy endpoints were mean percentage changes in HDL-C and TG (comparing each combination with statin montherapy) and LDL-C levels (comparing each combination with Trilipix monotherapy).97 All three studies consistently demonstrated that all Trilipix and statin dose groups resulted in greater increases in HDL-C and decreases in TG than the prespecified corresponding dose monotherapy. All three trials incorporated a 6-week dietary run-in period (during which patients underwent washout of any lipid-lowering medication), a 12-week treatment period, and a 30-day follow-up period. In addition, at study end, patients could be enrolled in a 12-month open-label extension study in order to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of combination therapy.

In the first trial to be completed, 657 patients with mixed dyslipidemia were enrolled. Patients were randomized to Trilipix 135 mg or simvastatin 20, 40, or 80 mg, or to the combination of Trilipix 135 mg plus simvastatin 20 or 40 mg once daily for 12 weeks.98 The trial met its primary efficacy endpoints. The combination of Trilipix with simvastatin 20 mg or 40 mg was more potent in reducing TG and increasing HDL-C levels than monotherapy with simvastatin 20 or 40 mg, and more potent in decreasing LDL-C levels compared with Trilipix monotherapy. Specifically, the combination of Trilipix with simvastatin 20 mg raised HDL-C levels by 17.8%, while simvastatin 20 mg raised HDL-C by 7.2% (P < 0.001). The combination of Trilipix with simvastatin 20 mg resulted in a reduction in TG levels by 37.4%, while monotherapy with simvastatin 20 mg lowered TG levels by 14.2% (P < 0.001). Trilipix with simvastatin reduced LDL-C levels by 24% while monotherapy with Trilipix reduced LDL-C levels by 4% (P < 0.001). The combination of Trilipix with simvastatin 40 mg resulted in improvement of all lipid parameters. Specifically, the combination raised HDL-C levels by 18.9% compared with 8.5% with simvastatin 40 mg monotherapy (P < 0.001), reduced TG levels by 42.7% versus 22.4% with simvastatin 40 mg (P < 0.001), and reduced LDL-C levels by 25.3% (versus 4% with Trilipix monotherapy, P < 0.001).98

Regarding the secondary endpoints of the trial, both combinations (Trilipix with simvastatin 20 mg or 40 mg resulted in greater improvements in non-HDL-C levels and VLDL-C levels compared with simvastatin and Trilipix monotherapies. Trilipix with simvastatin 20 mg resulted in greater reductions in apo B protein levels compared with simvastatin 20 mg (P < 0.012).98

Trilipix was compared with atorvastatin in 613 patients with mixed dyslipidemia.99 Patients were randomly assigned to monotherapy with Trilipix 135 mg or atorvastatin 20, 40, or 80 mg, or the combination of Trilipix with atorvastatin 20 or with 40 mg and treated for 12 weeks. Trilipix in combination with atorvastatin 20 mg resulted in a 45.6% reduction in TG levels versus 16.5% with atorvastatin 20 mg (P < 0.001). Regarding HDL-C levels, the combination increased HDL-C by 14%, while atorvastatin 20 mg increased HDL-C by 6.3% (P = 0.005). The combination also provided greater decreases in mean percentage LDL-C (33.7%) compared with Trilipix monotherapy (3.4%, P < 0.001). The results for the combination of Trilipix with atorvastatin 40 mg were similar, decreasing TG by 42.1% versus 23.2% with atorvastatin 40 mg monotherapy, while HDL-C increased by 12.6% versus 5.3% with atorvastatin 40 mg (P < 0.001 for TG and P = 0.01 for HDL-C). Trilipix with atorvastatin 40 mg decreased LDL-C levels by 35.4% (P < 0.001 versus Trilipix monotherapy). Trilipix with atorvastatin 20 mg also resulted in higher decreases in non-HDL-C levels compared with both monotherapies (P < 0.001 versus Trilipix and P = 0.026 compared with atorvastatin 20 mg). Apo B levels were significantly improved with combination therapy of Trilipix and atorvastatin 20 mg compared with atorvastatin monotherapy (P = 0.046). Trilipix combined with atorvastatin 40 mg also resulted in greater improvements in non-HDL-C levels compared with Trilipix (P < 0.001), and higher decreases in VLDL-C compared with atorvastatin 40 mg (P < 0.001). Total cholesterol and high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels did not differ among groups.99

The third randomized trial included in the Trilipix evaluation clinical program evaluated the efficacy and safety of Trilipix alone and in combination with rosuvastatin in a large number of patients with mixed dyslipidemia (n = 1445).100 Patients were randomized to receive Trilipix 135 mg, Trilipix plus rosuvastatin 10 or 20 mg, or rosuvastatin 10, 20, or 40 mg once daily for 12 weeks. Trilipix plus rosuvastatin 10 mg increased HDL-C by 20.3% versus 8.5% with rosuvastatin 10 mg alone (P < 0.001) and decreased TG by 47.1% versus 24.4% (P < 0.001). The mean percentage reduction in LDL-C with the combination of Trilipix and rosuvastatin 10 mg was 37.2%, compared with 6.5% with Trilipix monotherapy.

With the combination of Trilipix and rosuvastatin 20 mg, HDL-C decreased by 19% (mean percentage decrease) and by 10.3% with rosuvastatin 20 mg monotherapy. TG levels were reduced by 42.9% with the combination and by 25.6% with rosuvastatin alone (P < 0.001). Trilipix plus rosuvastatin 20 mg decreased LDL-C by 38.8% compared with Trilipix alone, which decreased LDL-C by 6.5% (P < 0.001).

Concerning the secondary efficacy endpoints, both combinations significantly improved non-HDL-C compared with Trilipix monotherapy. Trilipix plus rosuvastatin 10 mg resulted in greater improvements in VLDL-C, apo B, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein than rosuvastatin 10 mg. Trilipix plus rosuvastatin 20 mg significantly improved VLDL-C levels and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels compared with rosuvastatin 20 mg.100

The long-term safety and efficacy of Trilipix combined with simvastatin, atorvastin, or rosuvastatin was examined in a Phase III, open-label, 2-year extension study in patients who had completed one of the three abovementioned double-blind studies and the subsequent open-label, 1-year extension study. Of 310 patients enrolled, 287 completed the 2-year study.101 The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage of subjects reporting adverse events during combination therapy in the preceding double-blind studies or in the open-label 1-year study or 2-year study. No deaths or treatment-related serious adverse events were reported. No case of rhabdomyolysis occurred. The rate of discontinuation was 2.9% overall. This study also demonstrated that the improvements in HDL-C (+17.4%), TG (−46.4%), and LDL-C (−40.4%) were sustained.101

Additionally, a pooled subgroup analysis of the above-mentioned, randomized, double-blind trials in 586 patients with mixed dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes was performed. It was demonstrated that fenofibric acid and statin combination therapy in patients with mixed dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes was well tolerated, and resulted in more comprehensive improvement in the lipid and apolipoprotein profile than either monotherapy.102

Safety and tolerability

Several trials show that fenofibrate is safe and well tolerated.73,86 The most frequent adverse events are gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea and diarrhea) and musculoskeletal symptoms (myalgia and moderate elevation of creatine kinase). Other uncommon adverse effects are skin reactions and headache, fatigue, vertigo, sleep disorders, and loss of libido.70,73

Fenofibrate may increase creatinine and urea levels by 12% and 8%, respectively, while some have reported increases up to 40% and 36%, respectively.103 In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week trial, fenofibrate treatment was shown to decrease GFR by less than 20% in subjects with normal renal function compared with placebo.104 Renal function usually returns to baseline levels after drug discontinuation.103,105 However, permanent increases in transplant recipients have been observed.103 It has been suggested that fibrates may impair the generation of vasodilatory prostaglandins via PPAR-α activation, which can downregulate the expression of the inducible COX-2 enzyme.106 In the FIELD substudy, changes in markers of renal function in 170 type 2 diabetic patients were addressed. It was confirmed than fenofibrate increased creatinine levels and concomitantly decreased GFR.107 However, no cases of renal failure have been described with fenofibrate monotherapy in the FIELD study. These changes complicate the clinical surveillance and jeopardize compliance with fenofibrate treatment.

Indeed, in the ACCORD Lipid study, mean serum creatinine levels increased from 0.93 to 1.10 mg/dL (82 to 97 μmol/L) in the fenofibrate group within the first year and remained relatively stable thereafter.96 The study drug was discontinued by 66 patients (2.4%) in the fenofibrate group and 30 (1.1%) in the placebo group because of a decrease in the estimated GFR. At the last clinic visit, 440 patients (15.9%) in the fenofibrate group and 194 (7.0%) in the placebo group were receiving a reduced dose of either fibrate or placebo because of a decreased estimated GFR.96

The clinical relevance of the creatinine and GFR changes needs to be assessed in a long-term outcome study of renal function. Measurement of baseline creatinine values is advocated. Routine monitoring of creatinine is not necessary. If a patient has a clinically important increase in creatinine, other potential causes of creatinine increase should be excluded, and consideration should be given to discontinuing fibrate therapy or reducing the dose.21

It is well known that fibrates (apart from gemfibrozil) can induce considerable increases in homocysteine levels.108 Homocysteine levels have been speculated to increase CVD risk, however the clinical impact remains obscure.109,110 It has been suggested that the rise in homocysteine levels is directly related to the effects of fibrates on serum creatinine and on GFR, and mediated by PPAR-α activation. The rise in homocysteine levels has been implicated in the relative ineffectiveness of fenofibrate in the FIELD study.86 It has been suggested than increased homocysteine levels may reduce apo A I expression and may account for the small increases in HDL-c observed in the FIELD study.111

Fenofibrate is absolutely contraindicated in patients with severe renal or hepatic dysfunction, pre-existing gallbladder disease, or unexplained liver function abnormalities.

The greatest impediment in combining a fibrate with a statin is the potential risk of myopathy. Both fibrates and statins have been reported to cause myopathy and rhabdomyolysis.112–114 However, there are differences in myopathy risk between fibrates. Gemfibrozil in combination with any statin is associated with a 15-fold higher risk of rhabdomyolysis than fenofibrate, because these two classes of drug are metabolized by the same glucuronidation enzymes, as mentioned above.115,116 In the FIELD study, no cases of rhabdomyolysis was described among 944 patients receiving fenofibrate plus a statin.86 In the ACCORD Lipid study, elevations of creatine kinase of more than 10 times the upper limit of the normal range at any time during the trial occurred in 10 patients (0.4%) in the fenofibrate group and 9 (0.3%) in the placebo group (P = 0.83).96 No cases of rhabdomyolysis were reported.96

Based on data from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System fenofibrate may be the fibrate of choice for use in combination with a statin, and fenofibric acid (Trilipix) is the only fibric acid derivative approved for use in combination with a statin. The safety of the newer formulation of fenofibric acid alone and in combination with low and moderate statin therapy was evaluated as part of the Phase III clinical programme. Fenofibric acid proved to be safe both as monotherapy and in combination with statins. In addition, the long-term safety of fenofibric acid combined with statins was tested for up to 2 years in patients with mixed dyslipidemia. No deaths, rhabdomyolysis, or other serious adverse events were reported. However, there are reports in the literature of coadministration of fenofibrate and statins inducing rhabdomyolysis.117–119 Clinicians should be cautious, and other potential factors known to increase the risk of myopathy (eg, hypothyroidism, old age, and renal dysfunction) should be eliminated.119, 120

Treatment guidelines

According to several national guidelines, LDL-C reduction remains the primary target for treatment in both diabetic and nondiabetic for primary and secondary prevention.

In diabetic patients, although elevated LDL-C is not the major lipid abnormality, both the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recognize lowering LDL-C as the primary measure for CVD prevention. In type 2 diabetic patients, the proposed target for LDL-C is <100 mg/dL (2.59 mmol/L), while in 2008 the ADA proposed LDL-C to be <70 mg/dL (1.81 mmol/L) in patients with diabetes and CVD.2

Several national guidelines have addressed the issue of high TG, non-HDL-C and low HDL-C, without reaching definite conclusions. NCEP ATP III proposes that when TG levels exceed 200 mg/dL (>2.25 mmol/L) non-HDL-C (LDL, VLDL-C, and intermediate-density lipoprotein) should be a secondary target of therapy after the LDL-C target has been achieved. Goals for non-HDL-C cholesterol are 30 mg/dL (0.77 mmol/L) higher than goals for LDL-C.

On the basis of Class C evidence, the ADA in 2008 proposed for diabetic patients a TG target < 150 mg/dL (1.69 mmol/L) and HDL-C > 40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L; for men) and above 50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L; for women).121 While the AHA proposes in diabetic patients that, if TG levels are above 200 mg/dL (2.25 mmol/L), non-HDL-C should be below 130 mg/dL (3.36 mmol/L), without specifying a precise HDL-C target.2

Regarding secondary prevention, the AHA guidelines propose that if TG levels are 200–499 mg/dL (2.25–5.6 mmol/L) non-HDL-C should be <130 mg/dL (3.36 mmol/L) and even <100 mg/dL (2.59 mmol/L) if patients are at very increased risk. This could be achieved either by lowering LDL-C levels more intensively or by adding niacin or a fibrate.3

Updated guidelines from the NCEP ATP III recognize the potential of statin–fibrate combination therapy in patients with mixed dyslipidemia and CHD or CHD risk equivalents.25

All things considered, fenofibric acid is a useful adjunct indicated in combination with a statin to reduce TG and increase HDL-C in patients with mixed hyperlipidemia and CHD or CHD risk equivalents who are on optimal statin therapy to achieve the LDL-C goal. As monotherapy, it may be used to reduce TG levels in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia, to reduce total cholesterol, LDL-C, apo B, and TG, and to increase HDL-C in patients with primary hyperlipidemia or mixed hyperlipidemia. Trilipix delayed-release capsules can be taken without regard to meals. For convenience, the daily dose of Trilipix may be taken at the same time as a statin, according to the dosing recommendations for each medication.

Conclusions

The existing burden of CVD will continue to increase as the population ages. Statins constitute the mainstay of treatment, both in primary and secondary CVD prevention. However, many patients remain at risk of CVD despite LDL-C being at the recommended targets. It is now widely understood that, apart from LDL-C, the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis incorporates a number of other risk factors, including atherogenic dyslipidemia (elevated TG and low HDL-C levels) which should also be addressed.

Fenofibrate is a widely used hypolipidemic agent. Evidence demonstrating significant CVD reduction with fenofibrate is not robust. In the FIELD study, fenofibrate failed to reduce the primary endpoint of CHD death or nonfatal MI.86 However, fenofibrate reduced significantly the composite of CVD death, MI, stroke, and coronary or carotid revascularization. In addition, FIELD evaluated the effects of fenofibrate in a specific population (type 2 diabetics with a small percentage manifesting mixed dyslipidemia), and extrapolating these results in different populations is neither feasible nor reasonable. Although the results of FIELD may be relatively disappointing, the possibility of delaying both microvascular and macrovascular complications in diabetic patients is of particular importance. Hitherto, fenofibrate is the sole hypolipidemic treatment manifesting protection against microvascular events in diabetes patients.

The results of the ACCORD Lipid study were widely expected and not surprising, given that two-thirds of participants would not be treated with fibrates under current guidelines.96 While the primary endpoint of the study was not met, in the prespecified subgroup of patients with atherogenic dyslipidemia (elevated TG and low HDL-C) fenofibrate plus simvastatin was associated with a 31% lower rate of fatal and nonfatal CVD events than simvastatin alone. In line with earlier clinical trials, fenofibrate also reduced micro- and macroalbuminuria,96 both of which are markers of diabetic renal disease.

Currently, national guidelines and expert authorities propose a fibrate to be used as an adjunctive measure when LDL-C or non-HDL-C targets have not been achieved with statins. Fenofibrate is the fibrate of choice for combination with a statin. Trilipix is a new fenofibric acid formulation approved for use as monotherapy and the only one to be approved for combination with statins. The efficacy and safety of Trilipix alone and in combination with rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, or simvastatin have been extensively investigated in over 2400 patients with mixed dyslipidemia. Trilipix appears to be effective and safe both as monotherapy and in combination with statins. Trilipix may be taken without regard to meals, and may have greater bioavailability compared with prior formulations. The ability of patients to maintain drug adherence over time, as well as to a healthy lifestyle, is of special importance both for quality of life and for CVD reduction, and this property may be proved to be considerably advantageous.122

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buse JB, Ginsberg HN, Bakris GL, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in people with diabetes mellitus: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(1):162–172. doi: 10.2337/dc07-9917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith SC, Jr, Allen J, Blair SN, et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: Endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2006;113(19):2363–2372. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110(2):227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Executive summary. Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;(14 Suppl 2):E1–E40. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000277984.31558.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: Prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(15):1495–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shepherd J, Barter P, Carmena R, et al. Effect of lowering LDL cholesterol substantially below currently recommended levels in patients with coronary heart disease and diabetes: The Treating to New Targets (TNT) study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(6):1220–1226. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deedwania P, Barter P, Carmena R, et al. Reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with coronary heart disease and metabolic syndrome: Analysis of the Treating to New Targets study. Lancet. 2006;368(9539):919–928. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69292-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alsheikh-Ali AA, Lin JL, Abourjaily P, Ahearn D, Kuvin JT, Karas RH. Prevalence of low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with documented coronary heart disease or risk equivalent and controlled low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(10):1499–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh M, Chin SH, Giles PD, Crothers D, Al-Allaf K, Khan JM. Controlling lipids in a high-risk population with documented coronary artery disease for secondary prevention: Are we doing enough. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010 Mar 18; doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328338978e. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarwar N, Danesh J, Eiriksdottir G, et al. Triglycerides and the risk of coronary heart disease: 10,158 incident cases among 262,525 participants in 29 Western prospective studies. Circulation. 2007;115(4):450–458. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.637793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Best JD, O’Neal DN. Diabetic dyslipidaemia: Current treatment recommendations. Drugs. 2000;59(5):1101–1111. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gazi I, Tsimihodimos V, Filippatos T, Bairaktari E, Tselepis AD, Elisaf M. Concentration and relative distribution of low-density lipoprotein subfractions in patients with metabolic syndrome defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program criteria. Metabolism. 2006;55(7):885–891. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamarche B, Lemieux I, Despres JP. The small, dense LDL phenotype and the risk of coronary heart disease: Epidemiology, patho-physiology and therapeutic aspects. Diabetes Metab. 1999;25(3):199–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ascaso JF, Fernandez-Cruz A, Gonzalez Santos P, et al. Significance of high density lipoprotein-cholesterol in cardiovascular risk prevention: Recommendations of the HDL Forum. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2004;4(5):299–314. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200404050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Athyros VG, Mikhailidis DP, Kakafika AI, et al. Identifying and attaining LDL-C goals: Mission accomplished? Next target: New therapeutic options to raise HDL-C levels. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8(3):483–488. doi: 10.2174/138945007780058933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Role of fibrates in reducing coronary risk: A UK Consensus. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(2):241–247. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Backes JM, Gibson CA, Ruisinger JF, Moriarty PM. Fibrates: What have we learned in the past 40 years? Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(3):412–414. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.3.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trilipix [Package insert] North Chicago, IL: Abbott Laboratories; 2009. Available from: http://www.trilipixpro.com/ Accessed on May 26, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bairaktari ET, Tzallas CS, Tsimihodimos VK, Liberopoulos EN, Miltiadous GA, Elisaf MS. Comparison of the efficacy of atorvastatin and micronized fenofibrate in the treatment of mixed hyperlipidemia. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1999;6(2):113–116. doi: 10.1177/204748739900600208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schima SM, Maciejewski SR, Hilleman DE, Williams MA, Mohiuddin SM. Fibrate therapy in the management of dyslipidemias, alone and in combination with statins: Role of delayed-release fenofibric acid. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 11(5):731–738. doi: 10.1517/14656560903575639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Athyros VG, Mikhailidis DP, Papageorgiou AA, et al. Targeting vascular risk in patients with metabolic syndrome but without diabetes. Metabolism. 2005;54(8):1065–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone NJ, Bilek S, Rosenbaum S. Recent National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III update: Adjustments and options. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(4A):E53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caldwell J.The biochemical pharmacology of fenofibrate Cardiology 198976 Suppl 133–41.discussion 41–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adkins JC, Faulds D. Micronised fenofibrate: A review of its pharmacodynamic properties and clinical efficacy in the management of dyslipidaemia. Drugs. 1997;54(4):615–633. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199754040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chapman MJ. Pharmacology of fenofibrate. Am J Med. 1987;83(5B):21–25. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90867-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balfour JA, McTavish D, Heel RC. Fenofibrate. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in dyslipidaemia. Drugs. 1990;40(2):260–290. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199040020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tojcic J, Benoit-Biancamano MO, Court MH, Straka RJ, Caron P, Guillemette C. In vitro glucuronidation of fenofibric acid by human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37(11):2236–2243. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.029058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desager JP, Costermans J, Verberckmoes R, Harvengt C. Effect of hemodialysis on plasma kinetics of fenofibrate in chronic renal failure. Nephron. 1982;31(1):51–54. doi: 10.1159/000182614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rath NP, Haq W, Balendiran GK.Fenofibric acid Acta Crystallogr C 200561(Pt 2):o81–o84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu T, Ansquer JC, Kelly MT, Sleep DJ, Pradhan RS. Comparison of the gastrointestinal absorption and bioavailability of fenofibrate and fenofibric acid in humans. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010 Feb 9; doi: 10.1177/0091270009354995. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu T, Awni WM, Hosmane B, et al. ABT-335, the choline salt of fenofibric acid, does not have a clinically significant pharmacokinetic interaction with rosuvastatin in humans. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49(1):63–71. doi: 10.1177/0091270008325671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prueksaritanont T, Richards KM, Qiu Y, et al. Comparative effects of fibrates on drug metabolizing enzymes in human hepatocytes. Pharm Res. 2005;22(1):71–8. doi: 10.1007/s11095-004-9011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmad S. Gemfibrozil: Interaction with glyburide. South Med J. 1991;84(1):102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller DB, Spence JD. Clinical pharmacokinetics of fibric acid derivatives (fibrates) Clin Pharmacokinet. 1998;34(2):155–162. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199834020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergman AJ, Murphy G, Burke J, et al. Simvastatin does not have a clinically significant pharmacokinetic interaction with fenofibrate in humans. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44(9):1054–1062. doi: 10.1177/0091270004268044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan WJ, Gustavson LE, Achari R, et al. Lack of a clinically significant pharmacokinetic interaction between fenofibrate and pravastatin in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;40(3):316–323. doi: 10.1177/00912700022008874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goosen TC, Bauman JN, Davis JA, et al. Atorvastatin glucuronidation is minimally and nonselectively inhibited by the fibrates gemfibrozil, fenofibrate, and fenofibric acid. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35(8):1315–1324. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.015230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin PD, Dane AL, Schneck DW, Warwick MJ. An open-label, randomized, three-way crossover trial of the effects of coadministration of rosuvastatin and fenofibrate on the pharmacokinetic properties of rosuvastatin and fenofibric acid in healthy male volunteers. Clin Ther. 2003;25(2):459–471. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fruchart JC, Duriez P. Mode of action of fibrates in the regulation of triglyceride and HDL-cholesterol metabolism. Drugs Today (Barc) 2006;42(1):39–64. doi: 10.1358/dot.2006.42.1.963528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fazio S, Linton MF. The role of fibrates in managing hyperlipidemia: Mechanisms of action and clinical efficacy. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2004;6(2):148–157. doi: 10.1007/s11883-004-0104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Minnich A, Tian N, Byan L, Bilder G. A potent PPARalpha agonist stimulates mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation in liver and skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280(2):E270–E279. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.2.E270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hahn SE, Goldberg DM. Modulation of lipoprotein production in Hep G2 cells by fenofibrate and clofibrate. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43(3):625–633. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90586-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Desager JP, Horsmans Y, Vandenplas C, Harvengt C. Pharmacodynamic activity of lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase, and pharmacokinetic parameters measured in normolipidaemic subjects receiving ciprofibrate (100 or 200 mg/day) or micronised fenofibrate (200 mg/day) therapy for 23 days. Atherosclerosis. 1996;(124 Suppl):S65–S73. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05859-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Staels B, Vu-Dac N, Kosykh VA, et al. Fibrates downregulate apolipoprotein C-III expression independent of induction of peroxisomal acyl coenzyme A oxidase. A potential mechanism for the hypolipidemic action of fibrates. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(2):705–712. doi: 10.1172/JCI117717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sasaki J, Yamamoto K, Ageta M. Effects of fenofibrate on high-density lipoprotein particle size in patients with hyperlipidemia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, crossover study. Clin Ther. 2002;24(10):1614–1626. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andersson Y, Majd Z, Lefebvre AM, et al. Developmental and pharmacological regulation of apolipoprotein C-II gene expression. Comparison with apo C-I and apo C-III gene regulation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(1):115–121. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lemieux I, Salomon H, Despres JP. Contribution of apo CIII reduction to the greater effect of 12-week micronized fenofibrate than atorvastatin therapy on triglyceride levels and LDL size in dyslipidemic patients. Ann Med. 2003;35(6):442–448. doi: 10.1080/07853890310011969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Filippatos TD, Kiortsis DN, Liberopoulos EN, Georgoula M, Mikhailidis DP, Elisaf MS. Effect of orlistat, micronised fenofibrate and their combination on metabolic parameters in overweight and obese patients with the metabolic syndrome: The FenOrli study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(12):1997–2006. doi: 10.1185/030079905x75078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berthou L, Saladin R, Yaqoob P, et al. Regulation of rat liver apolipoprotein A-I, apolipoprotein A-II and acyl-coenzyme A oxidase gene expression by fibrates and dietary fatty acids. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232(1):179–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Filippatos TD, Liberopoulos EN, Kostapanos M, et al. The effects of orlistat and fenofibrate, alone or in combination, on high-density lipoprotein subfractions and pre-beta1-HDL levels in obese patients with metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10(6):476–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guerin M, Bruckert E, Dolphin PJ, Turpin G, Chapman MJ. Fenofibrate reduces plasma cholesteryl ester transfer from HDL to VLDL and normalizes the atherogenic, dense LDL profile in combined hyperlipidemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16(6):763–772. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.6.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watts GF, Ji J, Chan DC, et al. Relationships between changes in plasma lipid transfer proteins and apolipoprotein B-100 kinetics during fenofibrate treatment in the metabolic syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;111(3):193–199. doi: 10.1042/CS20060072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arakawa R, Tamehiro N, Nishimaki-Mogami T, Ueda K, Yokoyama S. Fenofibric acid, an active form of fenofibrate, increases apolipoprotein A-I-mediated high-density lipoprotein biogenesis by enhancing transcription of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 gene in a liver X receptor-dependent manner. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(6):1193–1197. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000163844.07815.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chinetti G, Lestavel S, Bocher V, et al. PPAR-alpha and PPAR-gamma activators induce cholesterol removal from human macrophage foam cells through stimulation of the ABCA1 pathway. Nat Med. 2001;7(1):53–58. doi: 10.1038/83348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Magee G, Sharpe PC. Paradoxical decreases in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with fenofibrate: A quite common phenomenon. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62(3):250–253. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.060913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mombelli G, Pazzucconi F, Bondioli A, et al. Paradoxical decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with fenofibrate: A quite rare phenomenon indeed. Cardiovasc Ther. 2010 Mar 10; doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2009.00121.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schneider A, Stange EF, Ditschuneit HH, Ditschuneit H. Fenofibrate treatment inhibits HMG-CoA reductase activity in mononuclear cells from hyperlipoproteinemic patients. Atherosclerosis. 1985;56(3):257–262. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(85)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brown WV. Focus on fenofibrate. Hosp Pract (Off Ed) 1988;(23 Suppl 1):31–40. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1988.11703636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elisaf M. Effects of fibrates on serum metabolic parameters. Curr Med Res Opin. 2002;18(5):269–276. doi: 10.1185/030079902125000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Filippatos T, Milionis HJ. Treatment of hyperlipidaemia with fenofibrate and related fibrates. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17(10):1599–1614. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.10.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee JJ, Jin YR, Yu JY, et al. Antithrombotic and antiplatelet activities of fenofibrate, a lipid-lowering drug. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206(2):375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hamilton SJ, Chew GT, Davis TM, Watts GF. Fenofibrate improves endothelial function in the brachial artery and forearm resistance arterioles of statin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Clin Sci (Lond) 2010;118(10):607–615. doi: 10.1042/CS20090568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koh KK, Han SH, Quon MJ, Yeal Ahn J, Shin EK. Beneficial effects of fenofibrate to improve endothelial dysfunction and raise adiponectin levels in patients with primary hypertriglyceridemia. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(6):1419–1424. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saougos VG, Tambaki AP, Kalogirou M, et al. Differential effect of hypolipidemic drugs on lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(10):2236–2243. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.147280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liamis G, Bairaktari ET, Elisaf MS. Effect of fenofibrate on serum uric acid levels. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34(3):594. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Belfort R, Berria R, Cornell J, Cusi K. Fenofibrate reduces systemic inflammation markers independent of its effects on lipid and glucose metabolism in patients with the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):829–836. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Birjmohun RS, Hutten BA, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES. Efficacy and safety of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol-increasing compounds: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(2):185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Knopp RH, Brown WV, Dujovne CA, et al. Effects of fenofibrate on plasma lipoproteins in hypercholesterolemia and combined hyperlipidemia. Am J Med. 1987;83(5B):50–59. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90871-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kornitzer M, Dramaix M, Vandenbroek MD, Everaert L, Gerlinger C. Efficacy and tolerance of 200 mg micronised fenofibrate administered over a 6-month period in hyperlipidaemic patients: An open Belgian multicenter study. Atherosclerosis. 1994;(110 Suppl):S49–S54. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)05378-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brown WV. Potential use of fenofibrate and other fibric acid derivatives in the clinic. Am J Med. 1987;83(5B):85–89. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90876-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Franceschini G, Calabresi L, Colombo C, Favari E, Bernini F, Sirtori CR. Effects of fenofibrate and simvastatin on HDL-related biomarkers in low-HDL patients. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195(2):385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.May HT, Anderson JL, Pearson RR, et al. Comparison of effects of simvastatin alone versus fenofibrate alone versus simvastatin plus fenofibrate on lipoprotein subparticle profiles in diabetic patients with mixed dyslipidemia (from the Diabetes and Combined Lipid Therapy Regimen study) Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(4):486–489. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.09.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grundy SM, Vega GL, Yuan Z, Battisti WP, Brady WE, Palmisano J. Effectiveness and tolerability of simvastatin plus fenofibrate for combined hyperlipidemia (the SAFARI trial) Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(4):462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kontush A, Chantepie S, Chapman MJ. Small, dense HDL particles exert potent protection of atherogenic LDL against oxidative stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(10):1881–1888. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000091338.93223.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.de Souza JA, Vindis C, Negre-Salvayre A, et al. Small, dense HDL3 particles attenuates apoptosis in endothelial cells: Pivotal role of apolipoprotein A-I. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14(3):608–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ruotolo G, Ericsson CG, Tettamanti C, et al. Treatment effects on serum lipoprotein lipids, apolipoproteins and low density lipoprotein particle size and relationships of lipoprotein variables to progression of coronary artery disease in the Bezafibrate Coronary Atherosclerosis Intervention Trial (BECAIT) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(6):1648–1656. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Otvos JD, Collins D, Freedman DS, et al. Low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein particle subclasses predict coronary events and are favorably changed by gemfibrozil therapy in the Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial. Circulation. 2006;113(12):1556–1563. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.565135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frick MH, Elo O, Haapa K, et al. Helsinki Heart Study: Primary-prevention trial with gemfibrozil in middle-aged men with dyslipidemia. Safety of treatment, changes in risk factors, and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(20):1237–1245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711123172001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Frick MH, Syvanne M, Nieminen MS, et al. Prevention of the angiographic progression of coronary and vein-graft atherosclerosis by gemfibrozil after coronary bypass surgery in men with low levels of HDL cholesterol. Lopid Coronary Angiography Trial (LOCAT) Study Group. Circulation. 1997;96(7):2137–2143. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de Faire U, Ericsson CG, Grip L, Nilsson J, Svane B, Hamsten A. Secondary preventive potential of lipid-lowering drugs. The Bezafibrate Coronary Atherosclerosis Intervention Trial (BECAIT) Eur Heart J. 1996;(17 Suppl F):37–42. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/17.suppl_f.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, et al. Gemfibrozil for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in men with low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Intervention Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(6):410–418. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Secondary prevention by raising HDL cholesterol and reducing triglycerides in patients with coronary artery disease: The Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention (BIP) study. Circulation. 2000;102(1):21–27. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Keech A, Simes RJ, Barter P, et al. Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): Randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9500):1849–1861. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Scott R, O’Brien R, Fulcher G, et al. Effects of fenofibrate treatment on cardiovascular disease risk in 9,795 individuals with type 2 diabetes and various components of the metabolic syndrome: The Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(3):493–498. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Effect of fenofibrate on progression of coronary-artery disease in type 2 diabetes: The Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study, a randomised study. Lancet. 2001;357(9260):905–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bruckert E, De Gennes JL, Malbecq W, Baigts F. Comparison of the efficacy of simvastatin and standard fibrate therapy in the treatment of primary hypercholesterolemia and combined hyperlipidemia. Clin Cardiol. 1995;18(11):621–629. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960181107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ellen RL, McPherson R. Long-term efficacy and safety of fenofibrate and a statin in the treatment of combined hyperlipidemia. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81(4A):B60–B65. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Athyros VG, Papageorgiou AA, Athyrou VV, Demitriadis DS, Kontopoulos AG. Atorvastatin and micronized fenofibrate alone and in combination in type 2 diabetes with combined hyperlipidemia. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(7):1198–1202. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kiortisis DN, Millionis H, Bairaktari E, Elisaf MS. Efficacy of combination of atorvastatin and micronised fenofibrate in the treatment of severe mixed hyperlipidemia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56(9–10):631–635. doi: 10.1007/s002280000213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liamis G, Kakafika A, Bairaktari E, et al. Combined treatment with fibrates and small doses of atorvastatin in patients with mixed hyperlipidemia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2002;18(3):125–128. doi: 10.1185/030079902125000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Derosa G, Cicero AE, Bertone G, Piccinni MN, Ciccarelli L, Roggeri DE. Comparison of fluvastatin + fenofibrate combination therapy and fluvastatin monotherapy in the treatment of combined hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and coronary heart disease: A 12-month, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Clin Ther. 2004;26(10):1599–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vega GL, Ma PT, Cater NB, et al. Effects of adding fenofibrate (200 mg/day) to simvastatin (10 mg/day) in patients with combined hyperlipidemia and metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(8):956–960. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, et al. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1563–1574. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jones PH, Bays HE, Davidson MH, et al. Evaluation of a new formulation of fenofibric acid, ABT-335, co-administered with statins : Study design and rationale of a Phase III clinical programme. Clin Drug Investig. 2008;28(10):625–634. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200828100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]