Abstract

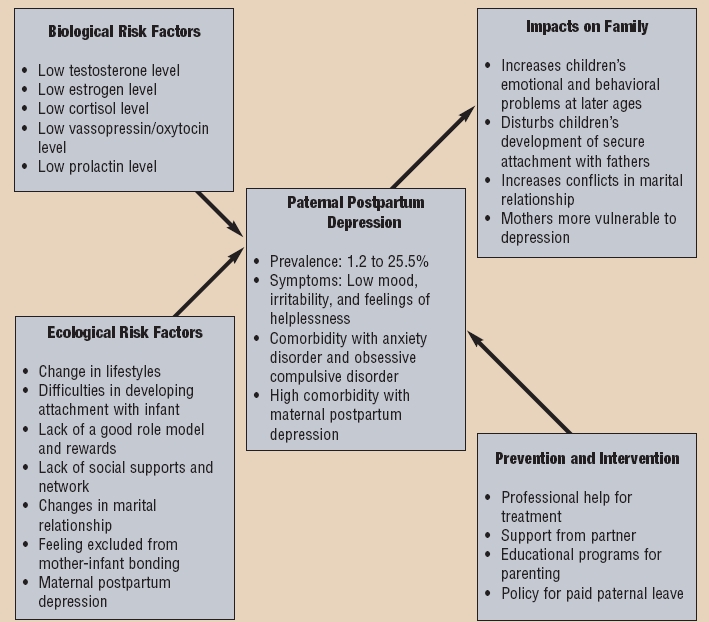

The postpartum period is associated with many adjustments to fathers that pose risks for depression. Estimates of the prevalence of paternal postpartum depression (PPD) in the first two months postpartum vary in the postpartum period from 4 to 25 percent. Paternal PPD has high comorbidity with maternal PPD and might also be associated with other postpartum psychiatric disorders. Studies so far have only used diagnostic criteria for maternal PPD to investigate paternal PPD, so there is an urgent need to study the validity of these scales for men and develop accurate diagnostic tools for paternal PPD. Paternal PPD has negative impacts on family, including increasing emotional and behavioral problems among their children (either directly or through the mother) and increasing conflicts in the marital relationship. Changes in hormones, including testosterone, estrogen, cortisol, vasopressin, and prolactin, during the postpartum period in fathers may be biological risk factors in paternal PPD. Fathers who have ecological risk factors, such as excessive stress from becoming a parent, lack of social supports for parenting, and feeling excluded from mother-infant bonding, may be more likely to develop paternal PPD. Support from their partner, educational programs, policy for paid paternal leave, as well as consideration of psychiatric care may help fathers cope with stressful experiences during the postpartum period.

Keywords: fathers/psychology, father-child relations, male, depressive disorders/complications, child development, postpartum depression

Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD) typically has been perceived as a problem limited to women with newborn babies and has not included men. Indeed, research accumulated over the past 50 years has focused on the biological and environmental features associated with maternal PPD and the increasingly clear deleterious impact on child development.1,2 However, fathers also experience significant changes in life after childbirth, many of which are similar to the experiences mothers. Fathers must also adjust to an array of new and demanding roles and tasks during the early postpartum period. This critically depends on the level and quality of cooperation between the mother and father. Clearly, the postnatal experience poses many challenges to men's as well as women's lives and mental health,3,4 and the timing and details of paternal PPD are just recently beginning to be recognized and studied.5–7 Studies suggest that paternal PPD has significant prevalence and impact on a father's positive support for both mother and baby during the first postpartum year. Recent media attention on the father's mental health during the postnatal year has also increased public awareness of this issue.8,9

Given the growing body of literature on paternal PPD, we have set out to review current understandings and discuss future research directions. This will help us to improve clinical insight, not only for improving fathers' mental health, but also for helping the family, including their partners and infants, have a better quality of life. The paper will review diagnostic criteria and characteristics of the paternal PPD and its impact on infants' and partners' lives. The paper will also posit biological and ecological risk factors for the paternal PPD and make suggestions for prevention and intervention. Last, the paper will discuss questions for further research. Please see Figure 1 for an overview of paternal PPD, including risk factors and outcomes.

Figure 1.

Model of paternal postpartum depression

Characteristics

Diagnosis. Remarkably, there is not yet one single official set of diagnostic criteria for paternal postpartum depression. Thus, paternal PPD has been defined in various ways. In research thus far, paternal PPD had been assessed by using measures developed for maternal PPD. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), maternal PPD is defined as a major depressive episode with onset occurring within four weeks of delivery.10 Depressive episodes include depressed or sad mood, marked loss of interest in virtually all activities, significant weight loss or gain, insomnia or hypersomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, diminished ability to think or concentrate, and recurrent thoughts of death.10 A diagnosis of a DSM-IV major depressive episode requires that five of these symptoms be present during a two-week period, and that at least one of the symptoms is either depressed or sad mood or a markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all or almost all activities.10 However, these diagnostic criteria have been defined only for maternal postpartum depression. The validation of similar criteria for paternal PPD as a diagnosis tool will be crucial as considering differences in risk factors for fathers and mothers. For example, there are findings suggesting that PPD develops more slowly and gradually over the more protracted course of a full year postpartum among men.11 Thus, this diagnostic criterion—onset of episodes within one month postpartum—may not be appropriate for diagnosing paternal postpartum depression.

In research on maternal PPD, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)12 has been widely used. It was first developed for assessing maternal postpartum depression, and it also has been most widely used in paternal PPD studies.6 It consists of 10 self-report items, eight addressing depressive symptoms (e.g., sadness, self-blame) and two inquiring about anxiety symptoms (e.g., feeling worried or anxious and feeling scared or panicky). Responses are scored 0, 1, 2, or 3 according to increased severity of the symptom. The period 6 to 12 weeks after childbirth is often used to assess postnatal depression, but many studies used the EPDS for later postpartum mood evaluation extend up to 12 months postpartum. Cut-off scores for depression vary from 9 to 13 points out of a maximum of 30. The EPDS has been well validated for woman in the US and non-English speaking populations in other countries12,13 and it has been validated for men as well.14 Other self-report measures that PPD studies rely on are Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),15,16 General Health Questionnaire (GHQ),17 and the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D).18

Some early studies used an unstructured or structured interview, such as the Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS)19 and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-II-R (SCID).20 The studies using the structured or unstructured interview often had small sample sizes drawn from limited populations. Although the findings thus far may not yet be applied to the general population, the qualitative interviews plus quantitative self-report measures do support the idea that paternal PPD may be a real and serious diagnostic entity.11

Many of the recent paternal PPD studies have relied on self-report measures of depressive symptoms, often using cut-off scores to establish a diagnosis of depression for women. The cut-off scores for men still need to be validated for different measures. There has been only one study examining the validation of the EPDS for men. The findings from the study suggest that the cut-off score to best identify fathers who were depressed and/or anxious is 5 to 6, which was two points lower than the cut-off score for mothers.14 Because lower cutoff scores are often used to diagnose minor PPD for women,21 there may have been underestimations of the significance of paternal PPD. Indeed, men may be considered to be less expressive about their feelings than women, thus, fathers are like to score lower in self-report questionnaires, such as the EPDS, than mothers even though they might experience a same levels of depression.14 Thus, the development of measures and validation of cut-off scores for paternal PPD are important for more sensitive and accurate diagnosis and efficient treatments and interventions.

Prevalence. Estimates of fathers' depression during the first postpartum year among US community-based samples vary from four percent (at 8 weeks, EPDS≥12)6 to 25.5 percent (at 4 weeks, CES-D≥16).22 Considering most of the studies have a relatively small number of samples, the Ramchandani and his colleagues' finding6 is important because of its large sample size (12,884 fathers).23 Internationally, the rate of paternal PPD ranges from 1.2 percent (at 6 weeks, EPDS≥13, in Ireland)24 to 11.9 % (at 6–12 weeks, BDI≥10, in Brazil).25 The wide range of estimates of paternal PPD may be related to the use of different measures, different cut-off scores, different timing of assessment between studies, as well as social, cultural, and economic differences. The characteristics of different samples might be also associated with different rates of depression. For instance, first-time fathers report higher levels of anxiety during the early postpartum period.26,27

Course. Paternal PPD tends to develop more gradually than maternal PPD. Longitudinal studies suggest that the rate of depression during the prenatal period decreases shortly after childbirth, but increases over the course of the first year. For instance, 4.8 percent of first-time fathers met criteria for depression during pregnancy and 4.8 percent of fathers were depressed at three months postpartum, but 23.8 percent of fathers were depressed at 12 months postnatal.28 A percentage (5.3%) of first-time fathers were screened positively for depression prenatally, and the rate decreased to 2.8 percent at six weeks postnatally, but increased again to 4.7 percent at 12 months postnatally.11 However, there are findings suggesting that the rate of paternal PPD is fairly consistent throughout the postpartum period. Deater-Deckard and his colleagues28 found that 3.5 percent of men during pregnancy and 3.3 percent at eight weeks were depressed. In another study, 4.5 percent of first-time fathers were depressed and the rate was steady at four percent throughout three, six, and 12 months postpartum.33

Correlates with maternal postpartum depression. Most of the data on paternal PPD come from studies originally designed for investigating maternal PPD. In all of these studies, depression in one partner was significantly correlated with depression in the other.22,29,31,32 In community samples, 32.6 to 47 percent of couples included at least one parent who experienced elevated depressive symptoms during the first two months postpartum.22,33 Moreover, it has been shown that nearly 60 percent of couples had at least one partner who was depressed either late in pregnancy or after the birth of their child.33

Maternal depression has consistently been found to be the most important risk factor for depression in fathers, both prenatally and postnatally.29,31,34,37–40 The incidence rate of paternal depression among men whose partners are having postpartum depression ranges from 24 to 50 percent.3,6 Further, Matthey and his colleagues11 found that fathers whose partners also has postpartum depression have a 2.5 times higher risk to be depressed themselves at six weeks postnatal compared to fathers whose partners don't have depression.

Comorbidity. Although there are few studies existing on this topic, the high comorbidity of postpartum depression with other psychiatric disorders has been found among men. The most common psychiatric disorders co-occurring with depression during postpartum period are anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Studies investigating fathers' experience during the transition to parenthood found that around 10 percent of fathers reported a significant elevation of anxiety levels.7,36,38 In a study by Matthey and colleagues7 with 356 fathers, the chance to have a depression was increased by 30 to 100 percent for men when they have anxiety problems. As for mothers, it has been suggested that fathers experience preoccupations akin to those of obsessive compulsive disorder39 during an initial critical period of ‘engrossment’ with the infant in which all other concerns and realities assume a lesser role in day to day life.40 This may include the usual thoughts and activities that contribute to mental health. In a prospective longitudinal study of 82 parents, the course of early preoccupations has been shown to peak around the time of delivery.41 Although fathers and mothers displayed a similar time course, the degree of preoccupation was significantly less for fathers. For example, at two weeks after delivery, mothers of normal infants, on average, reported spending nearly 14 hours per day focused exclusively on the infant, while father reported spending approximately half that amount of time. The mental content of these preoccupations includes thoughts of reciprocity and unity with the infant, as well as thoughts about the perfection of the infant. Further, 73 percent of mothers and 66 percent of fathers reported having the thought that their baby was ‘perfect’ at three months of age.41 These idealizing thoughts may be especially important in the establishment of psychological resiliency and the perception of self-efficacy during this time of stress and reorganized priorities. As such, their absence may be an indication of problematic early bonding. These parental preoccupations also include anxious, intrusive thoughts about the infant. In the few studies done so far, it was found that 95 percent of mothers and 80 percent of fathers experienced recurrent thoughts about the possibility of something bad happening to their babies at eight months of gestation. In the weeks following delivery, this percentage declined only slightly to 80 and 73 percent for mothers and fathers, respectively, and at three months these figures were unchanged.41,42 After delivery and on returning home, most frequently cited concerns related to feeding the baby, the baby's crying, adequacy as a new parent, and baby's wellbeing.41 Such thoughts are more commonly reported among parents of very sick preterm infants, infants with serious congenital disorders or malformations, or infants with serious birth complications.41 Parents also endorse fantasies or worries that they may in some way inadvertently harm their infant, for example, by dropping the baby in a time of exhaustion or frustration or even ignoring or injuring the baby.

Perhaps these intrusive thoughts of injuring the child can beset some at-risk new fathers and lead to postpartum obsessive compulsive disorder and/or depression. Indeed, depression and anxiety during the postpartum year can also be correlated with OCD. Typical symptoms of postpartum OCD include intrusive thoughts (such as harming their infant) and/or compulsive behaviors (such as checking babies).43 In the literature on maternal postpartum depression, 41 percent of mothers with major depression reported unwanted intrusive thoughts of harming their infant, compared to only seven percent of nondepressed mothers.44 Although Abramowitz and his colleagues45 did not find a significant association between severity of intrusions and depressive symptoms among fathers, it might be that such disturbing thoughts are not easily disclosed and need to be asked directly. In the same study, around 45 percent of men reported worries about whether their babies would be suffocated, around 25 percent of men reported worries about doing intentional harm to babies, and around three percent of the men reported worries about losing their babies. Fathers also often report a range of somatic symptoms and psychological problems related to the postpartum period, such as more fatigue, irritability, nervousness, and restlessness36,46 that likely influence the risk for depression.

These findings suggest that having one psychiatric disorder makes fathers more vulnerable to the other psychiatric disorders. Moreover, the presence of multiple comorbid psychiatric disorders might have cumulative or multiplicative detrimental effects on men's coping skills during the postpartum period. Questions, such as whether certain risk factors are particularly common across different psychiatric disorders and whether the severity of depressed symptoms are associated with the presence of other disorders, are waiting to be answered. Future studies are required to understand the full range of normal and abnormal adjustments to becoming a father coupled with possible comorbidities of other psychological problems that will clarify appropriate interventions for our understanding of fathers who suffer from paternal PPD—especially as it appears increasingly clear that paternal PPD has many detrimental effects on the family.

Impact on Family

The transition to become a new parent is a stressful experience for both men and women. Gjerdingen and Carter26 found that fathers and mothers both reported decreasing marital satisfaction due to the lack of supports and unstable mental states during the first six months after a child was born. The father's anxiety and depression may even translate into violent behaviors toward his partner. Among mothers in the postpartum period, an alarming one-fourth reported violence from their partners with 69 percent being the first occurrence.47 Given the importance of the partner's psychological support as a protective factor for postpartum depression,3 the low supports from fathers who experience PPD may cause a mother to become more vulnerable to stress and psychopathology.48

The poor mental health of the partner of a father with PPD might also affect an infant's development. In fact, the high comorbidity rate between maternal and paternal PPD (from 24 to 50%) suggests a high chance for an infant to be in a situation where both parents are depressed. An infant's development is more severely disrupted when both parents are depressed than when only one parent is depressed.5 The protective role of paternal care may become more important when a mother is depressed. One study shows that responsive care provided by the father can actually buffer an infant from being negatively influenced by the maternal PPD during development.49

In contrast to a large body of literature on maternal care and child development, the relationship between quality of paternal care and child development alone has been less well documented. However, an increasing number of recent studies suggest that fathers exhibit capabilities to interact with their infants almost as well as mothers.50–52 The quality of the paternal care is clearly important for a child's cognitive, emotional, and social development during the first years and likely beyond.6,53

For each infant, the first year is a critical period of forming basic biological and behavioral regulatory patterns through interactions with primary caregivers.54 An infant's heightened levels of the stress hormone cortisol resulting from unresponsive or chaotic parenting, can hamper normal brain growth and self-regulatory ability in the early life.55 Also, a chronic elevation of basal cortisol levels affects an infant's physiological growth and immune system.56 For example, negative interactions between a depressed parent and infant might interrupt the maturation of the infant's orbitofrontal cortex, which plays an important role in cognitive and emotional regulation throughout life.57

The first year is also an important time for an infant and parents to establish a secure attachment. Depressed parents tend to exhibit negative emotions and helplessness, which can influence their interactions with the infant. For instance, depressed mothers exhibit more irritability, apathy, and hostility to their infants.58 Remarkably, parenting styles of depressed fathers have not yet been studied in great detail. Some findings suggest the link between irresponsive and unaffectionate parenting of both mothers and fathers make infants and the development of insecure attachments.59 An insecure attachment between a depressed mother and her child can cause the child to develop emotional and behavioral problems as well as increase the risk of psychopathology.58 Similarly, one might expect that a father who experienced PPD might fail to build a secure attachment with his infant child, which in turn may have similar negative effects on the infant's development. The effects of the paternal PPD on an infant seem to interact with maternal mood and may indeed be long-term. A recent study found that children with fathers experiencing postpartum depression tend to exhibit greater behavioral problems, such as conduct problems or hyperactivity.6 Such negative impacts of paternal PPD on behavioral regulation were found to be stronger among boys than girls.6 In another study, paternal depression during the first year postpartum was shown to aggravate the negative impact of maternal depression on children's development only when a father interacts with an infant for medium to high amount of time.60 Finally, in an attempt to address the long-term outcomes, one recent study showed that paternal major depression was associated with lower psychosocial functioning, elevated suicidal ideation and attempt rates in sons in young adulthood, and depression in daughters.61

Further, paternal PPD is a risk factor for child maltreatment and infanticide. According to the literature on maternal PPD literature, one of the greatest risk factors for a child to be a victim of maltreatment and infanticide is mother's depression.62 Thus, it is conceivable that a depressed father in an unstable mental state may expose his infant child to a greater risk of such unfortunate events.

Biological Risk Factors

There is very little research on biological factors for paternal PPD despite a large body of literature on maternal PPD and how it is associated with the levels of hormones, such as estrogen, oxytocin, or prolactin, to understand a biological mechanism of mood dysregulation during the postpartum period.2 Based on the existing knowledge of maternal PPD, we conjecture that PPD experienced by a father might be caused by hormonal changes occurring during his partner's pregnancy and postnatal period. We will propose several biological factors for the onset and development of the paternal PPD.

First, paternal PPD might be related to changes in his testosterone level, which decreases over time during his partner's pregnancy and postpartum period.63,64 Testosterone levels started to decrease at least a few months before the childbirth and maintain low levels for several months after the childbirth among most of fathers.65 Several researchers suggest that such decrease leads to lower aggression, better concentration in parenting, and stronger attachment with the infant.65,66 Fathers who have lower testosterone levels expressed more sympathy and need to respond when they heard infants' cry.61 Interestingly, recent studies on older men show a significant correlation between low testosterone levels and depression.67 Men aged 45 to 60 who are clinically depressed also exhibit lower testosterone levels than normal men.68

Further studies are needed to show whether such correlations can be extrapolated to all fathers during the postpartum period and if they might be part of an excessive adjustment. If proven, testosterone levels might contribute to a biological explanation of paternal PPD and even point toward a means of testing and prevention.

Second, paternal PPD might be related to lower levels of estrogen. Among men, the estrogen level begins to increase during the last month of his partner's pregnancy until the early postpartum period.69 Given findings on the relation between increased levels of estrogen and maternal behaviors,70 the increase in estrogen in a father might enhance more active parenting behaviors after the birth of his child. Fleming and colleagues63 also found that the more involved the father is in parenting, the higher the level his estrogen is compared to other fathers. In rats, increased numbers of estrogen receptors in brain areas important for parental behaviors, including the medial preoptic area, are associated with parental experience with pups.71 Perhaps then dysregulation of paternal estrogen may disturb paternal behaviors and constitute another important risk factor for any depressed mood in fathers.

Third, paternal PPD might be related to lower levels of cortisol, a hormone that regulates the physiological responses to stressful events.72 High cortisol levels are generally associated with high stress levels. However, for a mother, during the early postpartum period, high cortisol levels are associated with increased sensitivity toward her infant73 and with less depressed mood.74 Thus, the lower levels of cortisol among certain fathers might be related to difficulties in father-infant bonding and associated depressed mood.

Fourth, paternal PPD might be related to low vasopressin levels, which increase after the birth of the child in a way analogous to the oxytocin level of the mother.75 Based on research in prairie voles, vasopressin appears to play an important role in enhancing the development of parent-infant bonding for fathers.76 A recent primate study reported on marmoset fathers, which are noted for their extensive involvement in parenting, particularly early postpartum period with behaviors such as carrying, protecting, and feeding their offspring.77 These paternal behaviors during the first month of the infant's life are associated with a rapid increase of vasopressin receptors in the prefrontal cortex of the brain. This particular brain area is important for planning and organizing appropriate parental behavior.78 Perhaps then, human fathers with low levels of vasopressin may have difficulties with parenting behaviors and so again be more vulnerable to depression.

Fifth, paternal PPD might be related to changes in prolactin levels. Prolactin is important for the onset and maintenance of parental behaviors.64 Prolactin levels in men rise during pregnancy and continue to rise during the first postnatal year.64 High prolactin levels are related to greater responses to infant stimuli among new fathers.64 Thus, a lower prolactin level could cause a father to experience difficulties in adapting to parenthood and thus exhibit more negative moods.

Ecological Risk Factors

An ecological model can provide a perspective to understand how different levels of environment, such as family, community, work, society and culture, interact and influence an individual's development.79 New demands and responsibilities during the postpartum period often cause major changes in a father's life. Thus, it is important to understand how stress factors in a father's environment affect the development of depression during the postpartum period.

Fathers often experience more difficulties in developing emotional bonds with their children than mothers, who tend to develop an attachment almost immediately after a child is born. The father-infant bond appears to develop more gradually over the first two months postpartum.80 Before then, fathers have more difficulties than mothers with emotional bonding with their infants.81 The relative slow development of attachment might be related to the father's feeling of helplessness and depression for the first few postpartum months.

One of the factors that may make parenting difficult for many fathers is the absence of a good role model. In recent years, we see a dramatic increase in society's expectation for fathers to have greater involvement in parenting, yet many fathers report that they did not learn appropriate parenting skills from their own fathers or other male seniors.82 Competence in parenting among fathers is significantly associated with the father's sense of mastery in his role and family functioning.83 The lack of understanding of what is expected of a father might cause anxiety, especially the first-time fathers, and lead to a greater risk of paternal PPD.30

Lack of rewards in parenting might also contribute to the development of paternal PPD. Fathers report positive feedbacks, such as smiles from their infants, as the most significant reward in parenting.80 However, a father's lack of experience in parenting and fewer hours with an infant may tend to make interactions more distressing for the infant. Fathers also report being isolated from mother-infant bonding and feeling jealous about their partners' dominance in spending intimate time with babies, especially through breastfeeding.3 Interestingly, fathers may report feelings of jealousy toward their babies because the babies occupy a great amount of their partner's attention.84

Furthermore, the stress from the relationship with their partners might influence fathers' moods during the postpartum period. Because of sudden life changes, marital relationships often are threatened during the early postnatal period time.80 Fathers report increased dissatisfaction with their relationships with their partners, including lack of intimacy85 and the partner's loss of interest in sexual relationship.30 Some studies found that the quality of relationship not only with their partners but also with their in-laws, especially mothers-in-law, can influence fathers' involvement in parenting.50

In marital relationships, fathers' parenting stress during the postpartum period can be further complicated by the differences in and perceptions of distinct gender roles of fathers and mothers. The emphasis on the man's role as the breadwinner may be increased due to the increased financial burdens after the birth of the child, and, in turn, may prevent fathers from being more involved in parenting. A greater feeling of failure in performance in both work and sex as a part of the emphasized male gender role is significantly related to psychological distress among fathers.86

Prevention and Intervention

For fathers, different types of support may ease the transition process to fatherhood during the postpartum period. The most effective supports likely come from their partners because paternal PPD is closely related to partners' mental health and their relationship with the fathers. More encouragement from a mother and active discussion in each couple as they await and prepare for their baby may help the father's involvement in parenting and ease the stress as a new father. Mothers sharing parenting roles with fathers may also lower fathers' feelings of isolation from the relationship between mother-infant, as well as difficult feelings, such as jealousy toward the infant. Furthermore, support and acknowledgement from other family members about the father's role and understanding the difficulties the fathers may encounter may have a positive effect on fathers.

Educational programs in the community help fathers understand their expected roles. Findings suggest that a program for PPD mothers and their partners is more effective then a program with PPD mothers alone.87 For the same reason, a program for both PPD fathers and mothers could be more effective to alleviate paternal PPD. In addition, because anxiety and depressed mood might start during the partner's pregnancy, earlier intervention for both parents would be more effective before the symptoms become serious.

Support from society, such as paid paternity leave, would help fathers adapt to changes during the postpartum period. The US has no policy for paid paternity or maternity leave.88 Globally, there are 45 countries with policies for paid paternity leave or parental leave (leave used as maternity or paternity leave), and 27 countries guarantee paid paternity leave. In the case of Finland, 68 percent of fathers use a three-week leave with part pay.89 Policy for paternity leave in Sweden has experienced changes to encourage fathers to exercise their right to paternal leave.78 “Father's quota” allocates 30 days among 450 days of parental leave for paternal leave. This means if fathers do not use 30 days for paternal leave, the days of parental leave will be lost. In addition to ‘Father’s quota,' fathers in Sweden have 10 days of paternity leave and allowance to take care of their families at home. This parental leave can be used any time until a child becomes 18 months old. There is accumulating evidence that there are benefits to child outcomes of positive paternity leave. For example, Feldman and colleagues90 showed that longer paternal leave is associated with a more positive attitude toward parenting. On the other hand, the shorter paternal leave is associated with low quality of child care and less adaptation at work among fathers.

Lack of understanding and lack of a supportive network for new fathers is common.28 Traditionally, fathers have been largely recognized only as support providers for their partners. However, given a recent increase in fathers' involvement in parenting, proper supports from the society that focus on the active roles of fathers would help new fathers ease their stress in the early postpartum period. For instance, encouraging fathers to seek help from health professionals for complete assessments and consideration of psychotherapy or antidepressants might significantly improve their family health.

Suggestions for future research. Paternal postpartum depression has only been studied by a small number of researchers, so it is not surprising that there is a long list of questions yet to be addressed.

Because the existing studies focus heavily on Caucasian, middle-class, married fathers, we have a serious lack of understanding about depression of fathers of different cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. It is important to identify at-risk groups of fathers for paternal PPD, such as fathers with lower incomes, fathers of very young or old age, or ethnic minority background. It is also important to study fathers in non-traditional settings, such as stay-at-home fathers, nonbiological fathers (e.g., stepfathers) or single fathers, in order to understand unique risk factors that may increase the risk for paternal PPD. Furthermore, we need to further investigate risk factors not only in fathers but also in their families, such as physical or mental health status with their partner or infant.

Besides the homogeneous samples in paternal PPD studies, the single time point observation limits our understanding of the long-term effects of postpartum depression. Because the experience of fathers changes in the course of the first postpartum year, we need a prospective study, with multiple sampling points, that allows follow-up of fathers at risk starting from their partners' pregnancies. The study would provide much information about the developmental course of paternal postpartum depression. Longitudinal studies would help us understand the long-term effects of paternal PPD on fathers' lives as well as on their families, including development of their children. Conducting international and cross-cultural studies would determine if there are similarities and differences in paternal PPD in different cultures and countries. It would provide us with a better picture to develop more accurate diagnostic tools and treatment programs for fathers with different backgrounds.

Most of the studies on paternal PPD have been done by using self-report questionnaires. Studies on hormonal and physiological changes during the postpartum period among fathers would provide information on biological factors of depression and biological mechanisms of father-infant attachment. In addition, brain imaging studies of paternal PPD will enrich our understanding of different brain circuits and neurohormonal systems that govern the processes of parenting in health and, in particular, among fathers with PPD.91

Contributor Information

Pilyoung Kim, Ms. Kim is from the Department of Human Development, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

James E. Swain, Dr. Swain is from the Child Study Center, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

References

- 1.Brockington I. Postpartum psychiatric disorders. Lancet. 2004;363(9405):303–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller LJ. Postpartum depression. JAMA. 2002;287(6):762–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.6.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutter M, Caspi A, Fergusson D, et al. Sex differences in developmental reading disability: New findings from 4 epidemiological studies. JAMA. 2004;291(16):2007–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.16.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.St John W, Cameron C, McVeigh C. Meeting the challenge of new fatherhood during the early weeks. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34(2):180–9. doi: 10.1177/0884217505274699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulson JF, Dauber S, Leiferman JA. Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):659–68. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramchandani P, Stein A, Evans J, et al. Paternal depression in the postnatal period and child development: a prospective population study. Lancet. 2005;365(9478):2201–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66778-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matthey S, Barnett B, Howie P, Kavanagh DJ. Diagnosing postpartum depression in mothers and fathers: Whatever happened to anxiety? J Affect Disord. 2003;74(2):139–47. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dads may suffer postpartum depression too. [August 9, 2006]. Wednesday, August 9, 2006 Available at: www.cnn.com/2006/HEALTH/08/07/dads.too.reut/

- 9.Father's blues can blight babies. [July 2, 2005]. June 24, 2005. Available at: news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/4122346.stm.

- 10.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthey S, Barnett B, Ungerer J, Waters B. Paternal and maternal depressed mood during the transition to parenthood. J Affect Dis. 2000;60(2):75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, et al. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA. 2000;284(5):592–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray D, Cox JL. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1990;8:99–107. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthey S, Barnett B, Kavanagh DJ, Howie P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for men, and comparison of item endorsement with their partners. 2001. J Affect Disord. 2001;64(2-3):175–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minde K, Corter C, Goldberg S, Jeffers D. Maternal preference between premature twins up to age four. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29(3):367–74. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for reserach in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Endicott J, Spitzer RL. A diagnostic interview: The schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:837–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchheim A, Erk S, George C, et al. Measuring attachment representation in an fMRI environment: A pilot study. Psychopathology. 2006;39(3):144–52. doi: 10.1159/000091800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagen EH. The functions of postpartum depression. Evolution and Human Behavior. 1999;20(5):325–59. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soliday E, McCluskey-Fawcett K, O'Brien M. Postpartum affect and depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1999;69(1):30–8. doi: 10.1037/h0080379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox J. Postnatal depression in fathers. Lancet. 2005;366(9490):982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lane A, Keville R, Morris M, et al. Postnatal depression and elation among mothers and their partners: Prevalence and predictors. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:550–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinheiro RT, Magalhaes PV, Horta BL, et al. Is paternal postpartum depression associated with maternal postpartum depression? Population-based study in Brazil. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(3):230–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gjerdingen DK, Center BA. First-time parents' prenatal to postpartum changes in health and the relation of postpartum health to work and partner characteristics. J Am Board Fam Prac. 2003;16(4):304–11. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.4.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinlivan JA, Condon J. Anxiety and depression in fathers in teenage pregnancy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(10):915–20. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Areias ME, Kumar R, Barros H, Figueiredo E. Correlates of postnatal depression in mothers and fathers. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169(1):36–41. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deater-Deckard K, Pickering K, Dunn JF, Golding J. Family structure and depressive symptoms in men preceding and following the birth of a child. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(6):818–23. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Condon JT, Boyce P, Corkindale CJ. The first-time fathers study: A prospective study of the mental health and wellbeing of men during the transition to parenthood. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38(1-2):56–64. doi: 10.1177/000486740403800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballard CG, Davis R, Cullen PC, et al. Prevalence of postnatal psychiatric morbidity in mothers and fathers. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(6):782–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.164.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudley M, Roy K, Kelk N, Bernard D. Psychological correlates of depression in fathers and mothers in the first postnatal year. J Reproduc Infant Psychol. 2001;19(3):187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raskin VD, Richman JA, Gaines C. Patterns of depressive symptoms in expectant and new parents. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:658–60. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.5.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harvey I, McGrath G. Psychiatric morbidity in spouses of women admitted to a mother and baby unit. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:506–10. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovestone S, Kumar R. Postnatal psychiatric illness: The impact on partners. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:210–16. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zelkowitz P, Milet TH. The course of postpartum psychiatric disorders in women and their partners. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189(9):575–82. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zelkowitz P, Milet TH. Postpartum psychiatric disorders: Their relationship to psychological adjustment and marital satisfaction in the spouses. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105(2):281–5. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skari H, Skredon M, Malt UF, et al. Comparative levels of psychological distress, stress symptoms, depression, and anxiety after childbirth: A prospective population-based study of mothers and fathers. Bjog-Int J Obstetr Gynaecol. 2002;109(10):1154–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leckman JF, Feldman R, Swain JE, et al. Primary parental preoccupation: Circuits, genes, and the crucial role of the environment. J Neural Transm. 2004;111:753–71. doi: 10.1007/s00702-003-0067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberg M, Morris N. Engrossment: The newborn's impact upon the father. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1974;44(4):520–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1974.tb00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leckman JF, Mayes LC, Feldman R, et al. Early parental preoccupations and behaviors and their possible relationship to the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scand. 1999;100:1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayes LC, Swain JE, Leckman JF. Parental attachment systems: Neural circuits, genes, and experiential contributions to parental engagement. Clin Neurosci Res. 2005;4:301–13. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abramowitz J, Moore K, Carmin C, et al. Acute onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder in males following childbirth. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(5):429–31. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.42.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jennings KD, Ross S, Popper S, Elmore M. Thoughts of harming infants in depressed and nondepressed mothers. J Affect Dis. 1999;54:21–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abramowitz JS, Schwartz SA, Moore KM. Obsessional thoughts in postpartum females and their partners: Content, severity, and relationship with depression. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2003;10(3):157–64. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clinton JF. Physical and emotional responses of expectant fathers throughout pregnancy and the early postpartum period. Int J Nurs Stud. 1987;24(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(87)90039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hedin LW. Postpartum, also a risk period for domestic violence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;89(1):41–5. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(99)00164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morse CA, Buist A, Durkin S. First-time parenthood: Influences on pre- and postnatal adjustment in fathers and mothers. J Psychosomat Obstetr Gynecol. 2000;21(2):109–20. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hossain Z, Field T, Gonzalez J, et al. Infants of ‘depressed’ mothers interact better with their nondepressed fathers. Infant Ment Health J. 1994;15:348–57. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solantaus T, Salo S. Paternal postnatal depression: Fathers emerge from the wings. Lancet. 2005;365(9478):2158–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feldman R. Infant-mother and infant-father synchrony: The coregulation of positive arousal. Infant Ment Health J. 2003;24(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feldman R, Eidelman AI. Parent-infant synchrony and the social-emotional development of triplets. Dev Psychol. 2004;40(6):1133–47. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pruett KD. Fatherneed. Why Father Care Is as Essential as Mother Care For Your Child. New York, NY: The Free Press; 2000. p. 244. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polan HJ, Hofer MA. Maternally directed orienting behaviors of newborn rats. Dev Psychobiol. 1999;34(4):269–79. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199905)34:2<269::aid-dev3>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Diverse patterns of neuroendocrine activity in maltreated children. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(3):677–93. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Federenko IS, Wadhwa PD. Women's mental health during pregnancy influences fetal and infant developmental and health outcomes. CNS Spectr. 2004;9(3):198–206. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900008993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schore AN. Back to basics: Attachment, affect regulation, and the developing right brain: Linking developmental neuroscience to pediatrics. Pediatr Rev. 2005;26(6):204–17. doi: 10.1542/pir.26-6-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martins C, Gaffan EA. Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant-mother attachment: A meta-analytic investigation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Disciplines. 2000;41(6):737–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. Mother-infant and father-infant attachment among alcoholic families. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14(2):253–78. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mezulis AH, Hyde JS, Clark R. Father involvement moderates the effect of maternal depression during a child's infancy on child behavior problems in kindergarten. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18(4):575–88. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Association of parental depression with psychiatric course from adolescence to young adulthood among formerly depressed individuals. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(3):409–20. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spinelli S, Pennanen L, Dettling AC, et al. Performance of the marmoset monkey on computerized tasks of attention and working memory. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2004;19(2):123–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fleming AS, Corter C, Stallings J, Steiner M. Testosterone and prolactin are associated with emotional responses to infant cries in new fathers. Horm Behav. 2002;42(4):399–413. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Storey AE, Walsh CJ, Quinton RL, Wynne-Edwards KE. Hormonal correlates of paternal responsiveness in new and expectant fathers. Evol Hum Behav. 2000;21(2):79–95. doi: 10.1016/s1090-5138(99)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wynne-Edwards KE. Hormonal changes in mammalian fathers. Horm Behav. 2001;40(2):139–45. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clark MM, Galef BGJ. A testosterone-mediated trade-off between parental and sexual effort in male mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) J Comp Psychol. 1999;113(4):388–95. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.113.4.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seidman SN, Walsh BT. Testosterone and depression in aging men. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;7(1):18–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Burnham TC, Chapman JF, Gray PB, et al. Men in committed, romantic relationships have lower testosterone. Horm Behav. 2003;44(2):119–22. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berg SJ, Wynne-Edwards KE. Salivary hormone concentrations in mothers and fathers becoming parents are not correlated. Horm Behav. 2002;42(4):424–36. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Numan M. A neural circuitry analysis of maternal behavior in the rat. Acta Paediatr. 1994;397(suppl):19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ehret G, Jurgens A, Koch M. Oestrogen receptor occurrence in the male mouse brain: Modulation by paternal experience. Neuroreport. 1993;10(4):1247–50. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199309000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nelson K. Event representations, narrative development, and internal working models. Attach Hum Dev. 1999;1(3):239–52. doi: 10.1080/14616739900134131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fleming AS, O'Day DH, Kraemer GW. Neurobiology of mother-infant interactions: Experience and central nervous system plasticity across development and generations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23(5):673–85. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fleming AS, Anderson V. Affect and nurturance: Mechanisms mediating maternal behavior in two female mammals. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1987;11:121–7. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(87)90049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Young LJ, Frank A. Beach Award. Oxytocin and vasopressin receptors and species-typical social behaviors. Horm Behav. 1999;36:212–21. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Z, Ferris CF, De Vries DJ. Role of septal vasopressin innervation in paternal behavior in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(1):400–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Welberg L. Fatherhood changes the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:833. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kozorovitskiy Y, Hughes M, Lee K, Gould E. Fatherhood affects dendritic spines and vasopressin V1a receptors in the primate prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(9):1094–5. doi: 10.1038/nn1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anderson AM. Factors influencing the father-infant relationship. J Fam Nurs. 1996;2:306–24. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Edhborg M, Matthiesen AS, Lundh W, Widstrom AM. Some early indicators for depressive symptoms and bonding 2 months postpartum: A study of new mothers and fathers. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8:221–31. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barclay L, Lupton D. The experiences of new fatherhood: A socio-cultural analysis. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(4):1013–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ferketich SL, Mercer RT. Predictors of role competence for experienced and inexperienced fathers. Nurs Res. 1995;44(2):89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Goodman JH. Becoming an involved father of an infant. J Obstetr Gynecolog Neonatal Nurs. 2002;34(2):190–200. doi: 10.1177/0884217505274581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Meighan M, Davis MW, Thomas SP, Droppleman PG. Living with postpartum depression: The father's experience. Am J Matern Child Nurs. 1999;24(4):202–8. doi: 10.1097/00005721-199907000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morse CA, Buist A, Durkin S. First-time parenthood: Influences on pre- and postnatal adjustment in fathers and mothers. J Psychosommatr Obstetr Gynaecol. 2001;21(2):109–20. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Morgan M, Matthey S, Barnett B, Richardson C. A group programme for postnatally distressed women and their partners. J Adv Nurs. 1997;26:913–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Heymann J, Earle A, Simmons S, et al. The Work, Family, and Equity Index; Where does the United States Stand Globally? Boston, MA: Harvard School of Public Health; 2004. The Project on Global Working Families; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Solantaus T, Salo S. Paternal postnatal depression: Fathers emerge from the wings. Lancet. 2005;365:2158–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Feldman R, Sussman AL, Zigler E. Parental leave and work adaptation at the transition to parenthood: Individual, marital, and social correlates. J Applied Dev Psychol. 2004;25(4):459–79. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Swain JE, Lorberbaum JP, Kose S, Strathearn L. The brain basis of early parenthood: Psychology, physiology and in-vivo functional neuroimaging studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01731.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]