Abstract

Recent studies have determined a seemingly consistent feature of able-bodied level ground walking termed the roll-over shape, which is the effective rocker (cam) shape that the lower limb system conforms to between heel contact and contralateral heel contact during walking (first half of the gait cycle). The roll-over shape has been found to be largely unaffected by changes in walking speed, load carriage, and shoe heel height. However, it is unclear from previous studies whether persons are controlling their lower limb systems to maintain a consistent roll-over shape or whether this finding is a byproduct of their attempt to keep ankle kinematic patterns similar during the first half of the gait cycle. We measured the ankle-foot roll-over shapes and ankle kinematics of eleven able-bodied subjects while walking on rocker shoes of different radii. We hypothesized that the ankle flexion patterns during single support would change to maintain a similar roll-over shape. We also hypothesized that with decreasing rocker shoe radii, the difference in ankle flexion between the end and beginning of single support would decrease. Our results supported these hypotheses. Ankle kinematics were changed significantly during walking with the different rocker shoe radii (p < 0.001), while ankle-foot roll-over shape radii (p = 0.146) and fore-aft position (p = 0.132) were not significantly affected. The results of this study have direct implications for designers of ankle-foot prostheses, orthoses, walking casts/boots, and rocker shoes. The results may also be relevant to researchers studying control of human movements.

Keywords: roll-over shape, ankle kinematics, rockers, rehabilitation

Introduction

Many researchers have modeled the physiologic ankle-foot system in attempts to better understand its functions during able-bodied gait, aiming to improve therapies for persons with disabilities that affect the system and to improve designs of ankle-foot prostheses and orthoses. Perry (1992) described the ankle-foot system as three rockers that aid in forward progression during walking. Other models used one continuous rocker to describe walking characteristics (Morawski and Wojcieszak, 1978; Gard and Childress, 2001; Gard et al., 2004). McGeer (1990) added more realistic features to this model, including swing phase knee flexion and a trunk segment, and created both computer and physical models that could passively walk down gentle slopes. McGeer estimated that the “equivalent radius” for human walking would be about 0.3 of leg length.

Knox (1996) concluded that the effective rocker shapes of prosthetic feet are important to their function for walking. He developed a method to measure these effective shapes and compared the shapes for prosthetic and physiologic ankle-foot systems during walking. The effective rocker that the ankle-foot system conforms to from heel contact to contralateral heel contact of walking was later termed the ankle-foot roll-over shape (Hansen et al., 2004). The roll-over shape may be a useful and simple tool for design and evaluation of lower limb prostheses because it has been shown to be nearly circular and relatively unaltered by changes in walking speed (Hansen et al., 2004), added weight to the torso (Hansen and Childress, 2005), and shoe heel height (Hansen and Childress, 2004) during able-bodied walking.

Although roll-over shapes have been found to be consistent for different level walking conditions, it is possible that their consistency is a byproduct of some other control strategy for walking. For example, humans may utilize position control of the ankle in walking to maintain a similar kinematic pattern during the step cycle (the same time period used to measure the roll-over shape). If so, the roll-over shape may also remain unchanged as a byproduct of unchanged ankle kinematics. This study used a series of rocker shoes to examine the relationship between ankle kinematics and roll-over shape. The purpose of the study was to determine whether ankle kinematics and/or roll-over shape would change when using different shoe rocker radii. We hypothesized that roll-over shapes would remain unchanged with different rocker shoe radii and that for decreasing rocker shoe radii, the change in ankle flexion during single limb stance phase would decrease. The results of this study may be useful to designers of lower limb prostheses, orthoses, walking casts/boots, and rocker shoes. Additionally, the results of this study may provide insight for persons studying control of human movements.

Methods

Subject Recruitment

We recruited eleven able-bodied subjects (6 male, 5 female) between the ages of 24 and 35 years. Their demographic information is reported here as mean ± standard deviation: age = 28.2 ± 3.5 years, height = 175.7 ± 10.0 cm, body mass = 71.2 ± 14.2 kg, and shoe size = 8.2 ± 2.3 (US men).

After the subjects gave written consent, approved by Northwestern University’s Institutional Review Board, we conducted ankle range of motion and strength tests. For ankle range of motion (non-weight bearing), the subjects needed to demonstrate maximum ankle dorsiflexion between 8 and 16 degrees and maximum plantarflexion between 48 and 60 degrees (Boone and Azen, 1979). They also needed to maintain endpoint range against resistance in both directions to demonstrate normal ankle strength. Those who did not qualify based on range of motion and strength criteria and those who had a history or fear of ankle injuries were excluded from participation in the study.

Shoe Modification

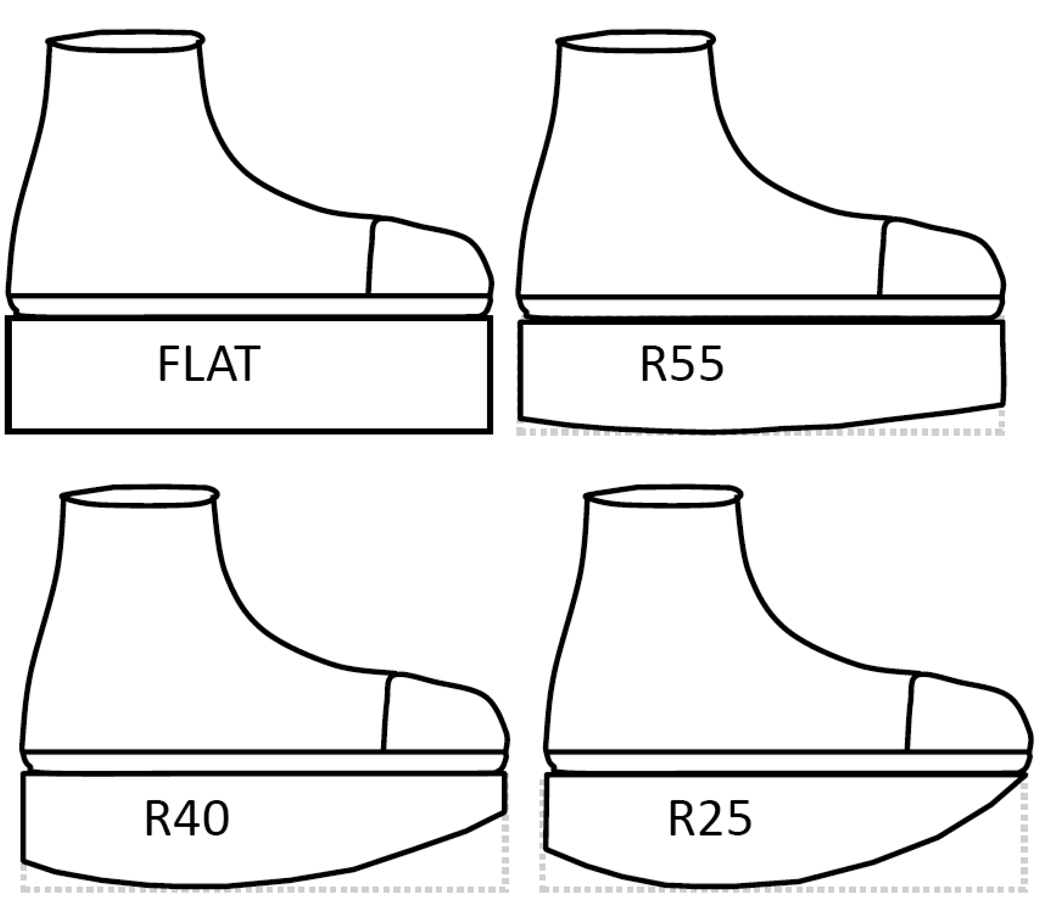

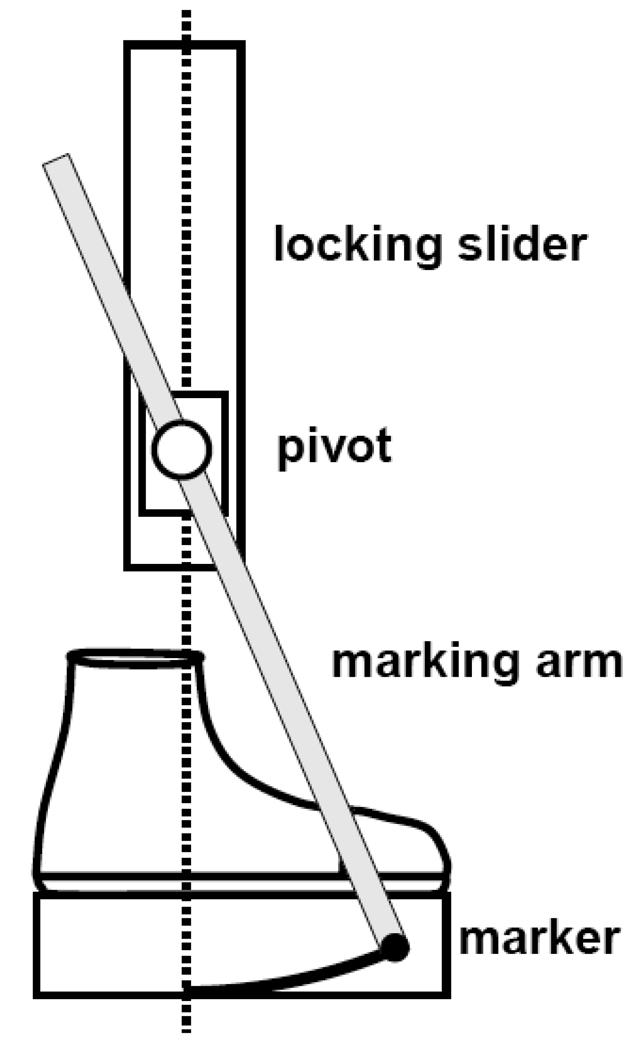

High-top canvas sneakers (Converse All-Star®) were modified into rocker shoes of four radii: 25% leg length (LL), 40% LL, 55% LL, and infinite (flat, elevated sole) (Figure 1). These are coded as R25, R40, R55, and FLAT, respectively. To create the rockers, we first glued three one-inch thick layers of crepe material (35–40 shore durometer) to the bottom of the sneakers. The crepe was then cut to match the outline of the shoe soles, with an additional centimeter around the edges of the shoe to create a wider base and reduce the risk of accidental ankle injuries. At the end of this step, the FLAT shoes were completed. To draw arcs on the lateral sides of the three remaining types of shoes, in order to cut out the rocker shapes, we used an adjustable jig (Figure 2). After cutting off the excess material and sanding, the rocker shoes were ready for use. We prepared sets of rocker shoes for a variety of shoe sizes, using anthropometric data (Dreyfuss, 1960) to estimate the leg lengths of persons who would use each pair of shoes, and these leg lengths to determine the rocker radii. When subjects were recruited for the study, we selected the shoes that most closely fit their feet for use in the study.

Figure 1.

Illustrations of high top canvas shoes with different radii rockers glued to the bottom surfaces. See text for explanations of R25, R40, R55, and FLAT.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the adjustable jig for marking the arcs on the soles of the shoes.

We chose to place the fore-aft positions of the center of the rockers at 40% of the foot length, referenced to the heel, based on the findings of Saha et al. (2007). In particular, Saha et al found that persons stand with their center of pressure at a location approximately 40% of the foot length from the end of the heels, regardless of trunk posture. The shoes were also used for a standing and swaying study (results not reported here) and this alignment of the arc was believed to provide a relatively neutral ankle alignment during quiet standing.

Gait Study

The experiments were conducted at the Veterans Affairs Chicago Motion Analysis Research Laboratory, which is equipped with six force platforms embedded in a 9.1 meter walkway that recorded data at 960 Hz (Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc., Watertown, MA, USA) and an eight-camera motion analysis system that recorded data at 120 Hz (Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa, CA, USA). The force and motion data were later synchronized at 120 Hz. Ground reaction forces (GRF) and their centers of pressure (COP) were measured by the force plates. A modified Helen Hayes marker set (Kadaba et al., 1990) was used to monitor anatomical landmarks of the body, which were captured and recorded by the motion analysis system. Of particular interest for this study were virtual markers at the ankle and knee centers and a marker on the lateral malleolus (ankle marker). The ankle center was determined as the midpoint between markers on the lateral and medial malleoli during a static standing trial. Although the medial malleolus marker was removed for walking trials, the ankle center could be recreated based on its relationship to three other markers on the shank, which was established during the static trial. The knee center was also found as the midpoint between medial and lateral epicondyle markers, determined from the static trial. After removal of the medial epicondyle marker for walking trials, the knee center could still be determined based on a relationship of this virtual marker to a local thigh coordinate system, also established from data collected during the static trial.

For each of the four pairs of shoes, the subjects were asked to walk at a freely-selected speed (normal), a speed that is 30% slower (slow), and one that is 30% faster (fast). The normal speed was established at the beginning of the study for each subject while wearing unmodified sneakers (no crepe soles) and was used to calculate the other target speeds. The order of the shoes in which the subjects walked was randomized, while the order of the walking speeds for each shoe was always normal, slow, then fast. The subjects were allowed a short time to become accustomed to each pair of the shoes prior to data acquisition. For each shoe and speed combination, we looked for four “clean” hits for each foot on the force plates. A “clean” hit was defined as a foot strike where the entire foot was within the boundaries of a force platform during stance phase, and no part of the other foot landed within these boundaries before or after that step. For each trial, the subjects were timed using a stopwatch to ensure that their speeds were within ±5% of the target normal, slow, or fast speeds.

Data Analysis

The data collected were first processed with EVaRealTime 5.0.3 and Orthotrak 6.5.2 (Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa, CA, USA), yielding ankle kinematics and marker coordinates. EVaRealTime 5.0.3 was used to interpolate missing data points (momentarily hidden markers), catch instances when markers on opposite sides of the body were mistakenly reversed, filter the data, and correct human errors (such as logging a “clean” hit on the incorrect side of the body).. Orthotrak 6.5.2 was used to determine marker positions (ankle, ankle center, and knee center as described earlier) as well as joint kinematics at the ankle, knee, hip, and pelvis. The difference in ankle flexion during single support was found as the ankle flexion at opposite heel contact subtracted by that at opposite toe off..

The ankle-foot roll-over shape was determined by transforming the center of pressure of the ground reaction force under the shoe from a laboratory-based to a shank-based coordinate system. The shank-based coordinate system was set up using a vector from the ankle center to the knee center as the Z-axis. The X-axis of the shank-based coordinate system was found as the vector perpendicular to the plane of the three markers (ankle, ankle center, and knee center) and pointing forward (Fatone and Hansen, 2007). The foot-shoe roll-over shape was also calculated by transforming COP data from a laboratory- to a foot-based coordinate system. The Z-axis of the foot-based coordinate system was found by taking a cross product of vectors defining the ankle joint axis (found using the ankle marker and ankle center) and the long axis of the foot (found using the heel and forefoot markers) in an order that resulted in an upward pointing vector. The X-axis of the foot-based coordinate system was in the direction pointing from the heel marker to the forefoot marker. Both roll-over shapes were fitted to circular arcs to compare how they changed with respect to the different shoes and walking speeds. A non-linear fitting routine (steepest descent least squares approach) was used to find the radius and fore-aft position of the best fitting lower arc of a circle, using a second order Taylor series expansion of the arc equation to provide the starting parameters (see Hansen et al., 2004).

SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform 3×4 two-way repeated measures ANOVA tests to see if there were significant differences in ankle flexion difference in single stance, ankle-foot roll-over shape radius and fore-aft shift, and foot-shoe roll-over shape radius and fore-aft shift between the three walking speeds and four rocker shoe radii. We used Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity to check the assumption of sphericity and used the Greenhouse-Geisser correction factor if it was violated (Field, 2000). Additionally, pairwise comparisons were performed for statistically significant factors (p < 0.05) and the Bonferroni adjustment was used for these post hoc tests (significance level readjusted to 0.05 by the software).

Results

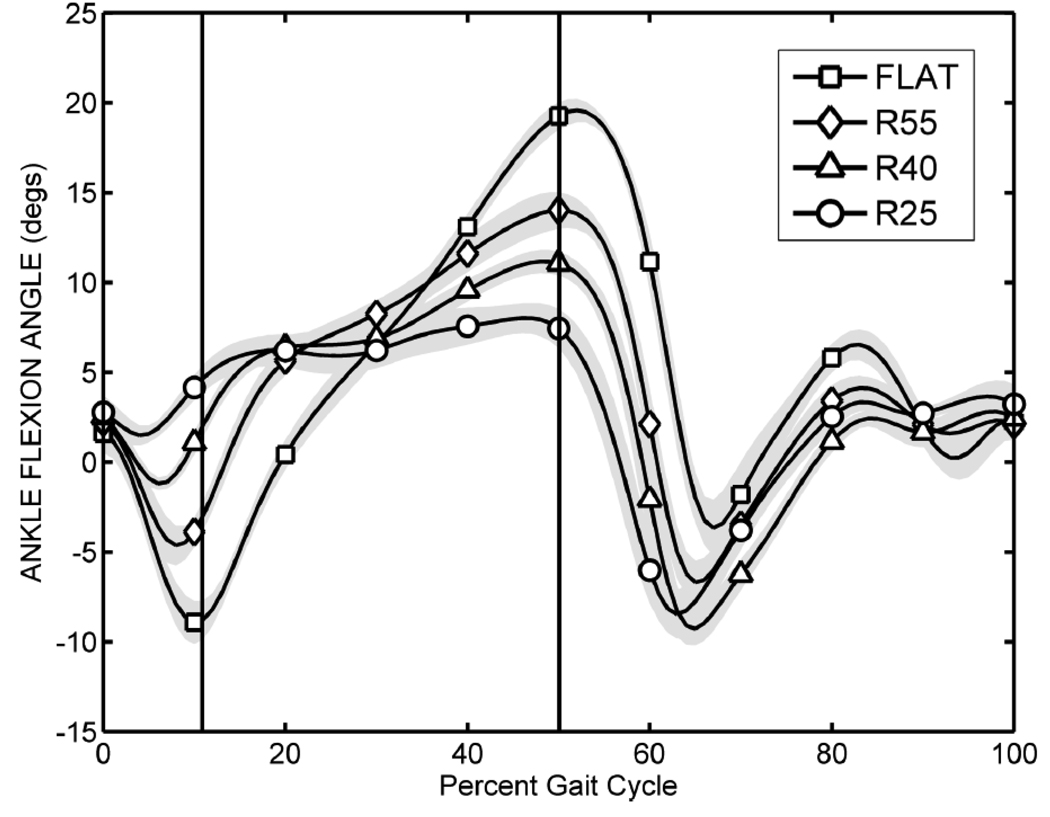

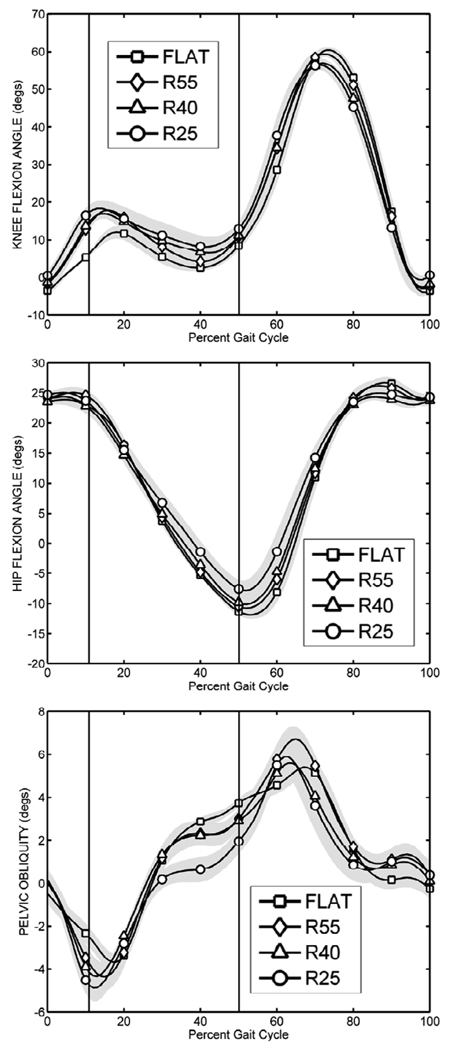

Ankle kinematics changed significantly when persons walked with different rocker shoe radii (Figure 3). The plots shown in Figure 3 are data collected from one subject at freely-selected speed, but are representative of the entire subject pool. The ankle difference during single support phase was found to be significantly affected by the rocker shoes (p < 0.001), and by walking speed (p = 0.013). Additionally, post-hoc pairwise comparisons indicated significant changes in ankle flexion differences during single support phase between all of the rocker shoe radii (p < 0.004 for all comparisons). Pairwise comparisons of the speed conditions indicated a significant difference in the ankle flexion difference measurement between slow and normal speeds (p = 0.021), but not between other speed comparisons (p ≥ 0.142 for other comparisons). For all walking speeds, the ankle flexion difference decreased with decreasing rocker shoe radii (Table 1). Other joint kinematics including knee flexion, hip flexion, and pelvic obliquity were affected less substantially by changing shoe rocker radii and were not analyzed using statistical analysis (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Ankle flexion over the entire gait cycle of a representative subject’s right foot at freely-selected speed. During single support (~ 12.5% - 50.2% gait cycle), the difference in ankle flexion changed significantly (p < 0.001) between rocker shoe conditions.

Table 1.

Ankle flexion difference during single limb stance and roll-over shape characteristics for eleven able-bodied subjects walking with four rocker shoes and at three walking speeds (Data are presented as means ± standard deviations)

| Shoe | Speed | Ankle flexion difference (deg) |

Ankle-foot roll-over shape | R2 | Foot-shoe roll-over shape | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radius (% height) |

Fore-aft position (% height) |

Radius (% height) |

Fore-aft position (% height) |

|||||

| R25 | slow | 5.3 ± 2.7 | 16.9 ± 5.2 | 0.9 ± 1.0 | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 23.3 ± 8.1 | 1.1 ± 1.4 | 0.94 ± 0.06 |

| normal | 5.0 ± 3.4 | 15.1 ± 4.0 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 0.91 ± 0.10 | 19.6 ± 3.4 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | |

| fast | 4.6 ± 3.7 | 15.9 ± 5.4 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 0.85 ± 0.17 | 19.2 ± 2.9 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 0.89 ± 0.11 | |

| R40 | slow | 8.4 ± 3.0 | 17.3 ± 2.8 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.97 ± 0.03 | 26.7 ± 7.2 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 0.93 ± 0.08 |

| normal | 9.4 ± 3.4 | 16.9 ± 3.9 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 23.8 ± 4.7 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 0.96 ± 0.04 | |

| fast | 9.2 ± 3.2 | 16.2 ± 4.0 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 0.90 ± 0.17 | 23.4 ± 4.1 | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 0.92 ± 0.08 | |

| R55 | slow | 11.5 ± 3.5 | 17.8 ± 2.0 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.99 ± 0.02 | 32.3 ± 7.9 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 0.97 ± 0.04 |

| normal | 12.9 ± 3.8 | 16.8 ± 2.0 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 27.1 ± 3.4 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 0.98 ± 0.02 | |

| fast | 13.2 ± 4.0 | 16.7 ± 3.2 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 0.95 ± 0.07 | 27.6 ± 2.6 | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 0.94 ± 0.06 | |

| FLAT | slow | 20.4 ± 4.9 | 19.0 ± 2.5 | 0.5 ± 0.6 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 77.3 ± 24.9 | 1.2 ± 1.7 | 0.93 ± 0.07 |

| normal | 23.2 ± 4.3 | 17.8 ± 2.4 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 58.4 ± 18.7 | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | |

| fast | 22.9 ± 4.3 | 17.6 ± 2.9 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 52.0 ± 12.1 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 0.86 ± 0.09 | |

|

p values for main effects |

shoe | p < 0.001a | p = 0.146 | p = 0.132 | p < 0.001d | p = 0.149 | ||

| speed | p = 0.013b | p = 0.348 | p = 0.012c | p < 0.001e | p < 0.001f | |||

p < 0.004 for all comparisons;

slow & normal (p = 0.021), p ≥ 0.142 for other comparisons;

p ≥ 0.07 for all comparisons;

R25 & R40 (p = 0.128), p ≤ 0.019 for other comparisons;

normal & fast (p = 0.585), p ≤ 0.016 for other comparisons;

p ≤ 0.009 for all comparisons

Figure 4.

(top) Knee flexion, (center) hip flexion, and (bottom) pelvic obliquity curves of a representative subject’s right side at freely-selected speed. Movements of the knee, hip, and pelvis seemed less affected by changes in shoe rocker radius when compared with changes in ankle kinematics.

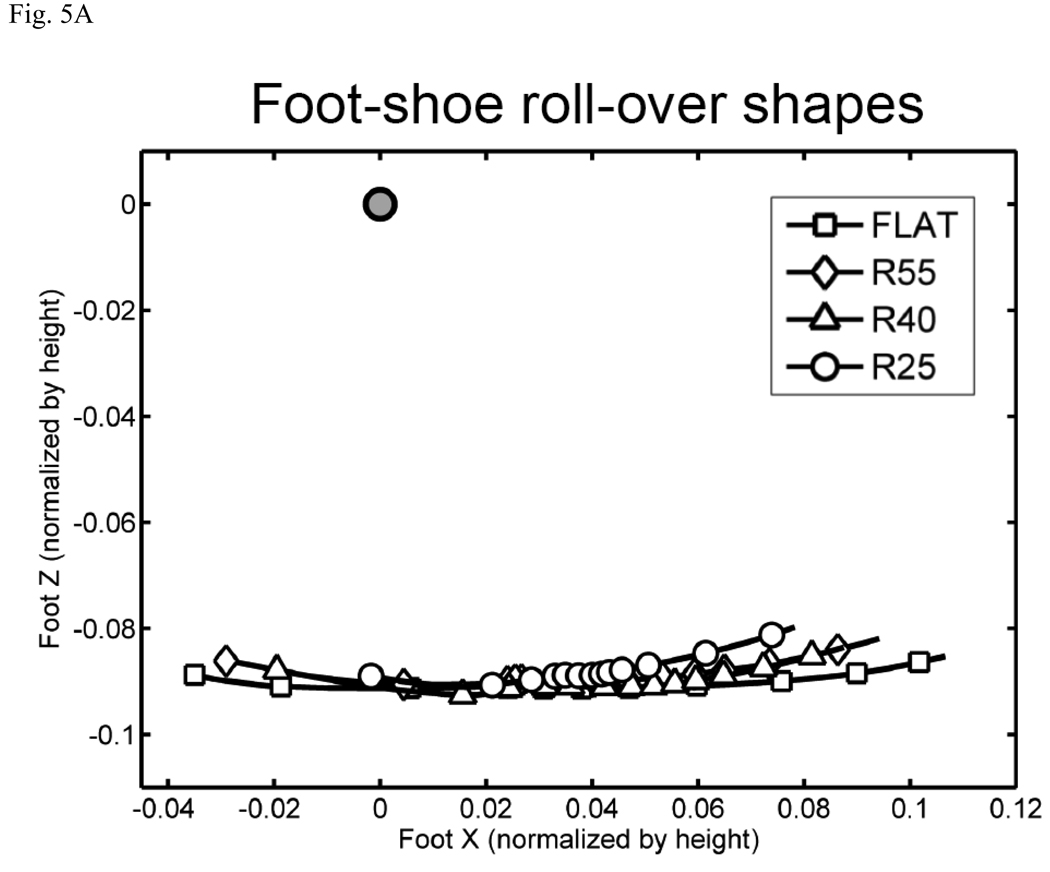

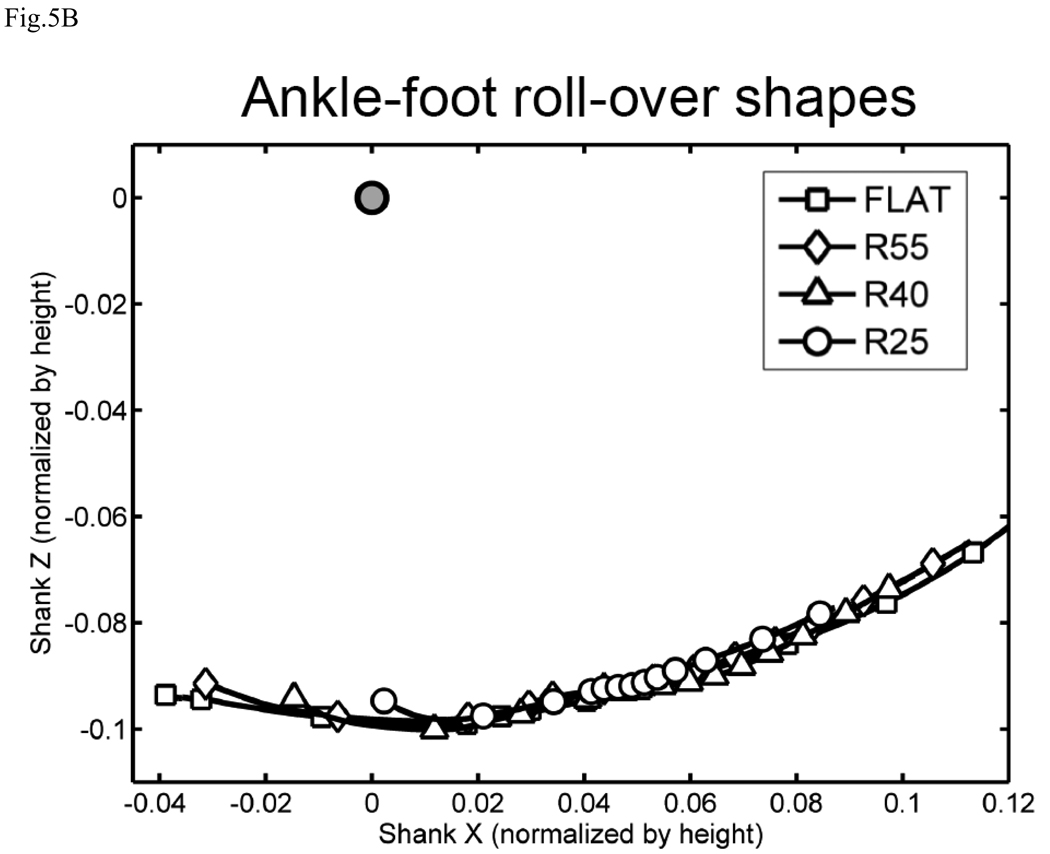

Foot-shoe roll-over shapes were altered by changes in shoe rocker radii, while ankle-foot roll-over shapes appeared fairly consistent for the different rocker shoe conditions (Figure 5). The radii of the foot-shoe roll-over shapes were significantly changed in response to different rocker shoe radii (p < 0.001) and walking speeds (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Pairwise comparisons indicated statistically different radii for all shoe comparisons (p ≤ 0.019) except for the R25 and R40 comparison (p = 0.128). Also, pairwise comparisons of foot-shoe roll-over shape radii for different speed conditions indicated significant differences between all conditions (p ≤ 0.016) except for the normal and fast comparison (p = 0.585). Fore-aft positions of the best-fit circular arcs to the foot-shoe roll-over shapes were not significantly affected by the shoe condition (p = 0.149). However, the fore-aft positions were significantly affected by speed (p < 0.001 for main effect), with significant differences in all pairwise comparisons (p ≤ 0.009 for all comparisons).

Figure 5.

(A) Foot-shoe roll-over shapes (normalized by height) of a representative subject’s right foot at freely-selected speed. The foot-shoe roll-over shapes were significantly changed by the rocker shoe condition (p < 0.001). Foot X and Foot Z are sagittal dimensions of the foot-based coordinate system. (B) Ankle-foot roll-over shapes (normalized by height) for the same subject walking at freely-selected speed. The ankle-foot roll-over shapes were not significantly affected by the shoe or speed conditions. Shank X and Shank Z are sagittal dimensions of the shank-based coordinate system.

On the other hand, the radii of the ankle-foot roll-over shapes were not changed significantly with changes in rocker shoe radii (p = 0.146) or walking speeds (p = 0.348) (Figure 5 and Table 1). The best-fit radius of the ankle-foot roll-over shape for all four shoes and three walking speeds for the eleven subjects was 17.0 ± 3.4% of height or 32.1 ± 6.3% of leg length (using scaling conversions in Dreyfuss (1960)). Lastly, the fore-aft shift of the best-fit circular arcs to the ankle-foot roll-over shapes was not significantly affected by the shoe condition (p = 0.132), but was significantly affected by the walking speed (p = 0.012). However, pairwise comparisons of the fore-aft shift of the best fit arcs to the ankle-foot roll-over shapes between walking speed conditions showed no significant differences (p ≥ 0.07 for all comparisons).

Discussion

As hypothesized, the ankle responded to changes in rocker shoe radius and walking speed to maintain a consistent ankle-foot roll-over shape. Additionally, the response to different shoes seemed to occur primarily at the ankle joint, with less dramatic changes seen in knee flexion, hip flexion, and pelvic obliquity. It is not clear why ankle-foot roll-over shape remains consistent for a variety of level walking conditions. However, results from previous studies suggest that rocker radius could be linked to stability and efficiency in walking. In particular, Wisse and van Frankenhuyzen (2003) showed that increasing the rocker radius of feet on a simple walking machine increased the machine’s ability to withstand perturbations, suggesting a relationship between rocker radius and stability in walking. Additionally, Adamczyk et al. (2006) found that able-bodied persons using rigid rocker radii near 1/3 of leg length had reduced energy consumption compared with the consumption associated with smaller or larger radii, suggesting a relationship between rocker radius and efficiency in walking. This study shows that able-bodied humans will greatly change their ankle coordination strategies for different rocker shoes, leading to consistent ankle-foot roll-over shapes. However, the exact rationale for these results and the coordination schemes leading to consistent roll-over shape are not currently understood. The consistent roll-over shape radius may still be a byproduct of some other movement control scheme and further work is needed to understand this phenomenon. However, the finding that humans tend to have a consistent roll-over shape is useful information for designers of ankle-foot prostheses, orthoses, walking casts/boots, and rocker shoes. In particular, it may be possible to design rocker shoes for a prescribed ankle motion using consistent roll-over shape as a guiding principle.

The foot-shoe roll-over shape radii were changed significantly as a function of the shoe and the walking speed conditions (except between R25 and R40 shoes and between normal and fast speeds). The change in foot-shoe roll-over shape radii between shoe conditions was expected since the shoe rockers were intentionally altered and the adaptation of the foot to these different conditions was expected to be small. The change in foot-shoe roll-over shape radii for different walking speeds was not expected, but can potentially be explained. The radii of the foot-shoe roll-over shapes decreased as the speed went from slow to normal. The loading between slow and normal speeds is known to be different, with slower speeds corresponding to more uniform loading of the leg during stance phase and normal and fast speeds corresponding to a “double bump” pattern of loading. With the fluctuating “double bump” loading, one could expect more deformation of the shoe sole on the heel and toe ends compared with the area in the middle of the foot. Extra compression of the sole on the ends compared to the middle would lead to smaller measured radii, which were found in this study. The measured foot-shoe roll-over shape radii were consistently smaller than the radii marked on the soles of the shoes, perhaps also due to non-uniform deformation of the shoe sole materials during stance phase.

The fore-aft positions of the best fit arcs to the foot-shoe roll-over shapes were not affected by the shoe condition, which was expected since all shoes were marked with the low point of the arc in the same position using the jig in Figure 2. It is unclear why the fore-aft shift of the foot-shoe roll-over shape was significantly changed with different speeds, although the trend suggests more compression of the heel compared with the toe end of the shoe soles as speed increased.

Despite differences in the foot-shoe roll-over shapes for different shoes and walking speeds, the ankle-foot roll-over shape radii were not significantly affected by shoe or speed conditions. The ankle-foot roll-over shape radii found in the study (17.0 % height) are also very similar to the roll-over shape radii presented in earlier studies (Hansen, 2002; Hansen et al, 2004; Hansen and Childress, 2004; Hansen and Childress, 2005). The fore-aft positions of the ankle-foot roll-over shapes were also not significantly affected by the shoe condition. A significant main effect was found suggesting that speed has an influence on the fore-aft position of the ankle-foot roll-over shape. However, pairwise comparisons showed no significant differences between the speed conditions. Hansen et al (2004) found a similar trend in fore-aft shifts of the best-fit circles to knee-ankle-foot roll-over shapes as a function of walking speed, although the changes were considered to be clinically insignificant. The small changes in fore-aft shift seen in this study (maximum mean change of 0.7% height) also seem clinically insignificant. However, with larger sample sizes, one might expect to see small increases in the ankle-foot roll-over shape radius and small increases in the fore-aft shift of the rocker shapes with increasing shoe rocker radius. Similarly, a larger sample size may find small decreases in the radius and small increases in the fore-aft shift with increasing speeds.

While radius and fore-aft position of the best-fit arcs to the ankle-foot roll-over shapes were unaffected by speed and shoe conditions in this study, it is clear that the arc lengths of these roll-over shapes were dramatically shortened as the shoe rocker radius decreased (see Figure 5). However, as the shoe rocker radii decrease, the combination of the shoe rocker and possible ankle rotations in a shank-based coordinate system makes it geometrically impossible for the user to obtain some of the points on the heel and toe ends of the roll-over shapes when using the FLAT shoe condition.

Similar to previous studies, we used a circular arc to describe the roll-over shapes. Table 1 indicates the mean coefficients of determination (R2 values) for the various circular arc fits. All of the mean R2 values were above 0.85, suggesting that the circular model can explain 85% or more of the variation in the vertical component as a function of the horizontal component. The exact fit was not examined in great detail and it is possible that other models may fit the data more appropriately. However, the simplicity of the circular fit and the widespread understanding of circular parameters make this model highly useful for communication of results and potential use in clinical settings.

This study had a number of limitations including a small sample size and potentially non-uniform scaling of shoe rocker radii to leg length and height (shoes were scaled to foot length and related to leg length through anthropometric data). However, the main objective of altering the foot-shoe system and monitoring the ankle’s reaction and corresponding ankle-foot roll-over shape were achieved with the experimental setup.

In conclusion, changes in shoe rocker radius led to significant changes in ankle kinematics in eleven able-bodied subjects. The changes in ankle kinematics corresponded with consistent ankle-foot roll-over shapes, suggesting that the ankle-foot roll-over shape may be a useful and simple constraint for design of ankle-foot devices in rehabilitation. This study suggests that consistent roll-over shapes for level walking found in previous studies were not simply byproducts of consistent ankle kinematics, although the specific reason for consistent ankle-foot roll-over shapes for level walking is still unknown.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the use of the VA Chicago Motion Analysis Research Laboratory. We would like to thank Rebecca Stine for her help with data collection and analysis, Stefania Fatone for her help with ankle strength and range of motion testing, Kathy Waldera for her help with making the rocker shoes, and Sara Koehler and Brian Ruhe for their help with statistics used in this study. This publication was made possible by Grant Number R03-HD050428-01A2 from the NIH. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could influence their work or pose conflicts of interest.

References

- Adamczyk PG, Collins SH, Kuo AD. The advantages of a rolling foot in human walking. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2006;209(Pt 20):3953–3963. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone DC, Azen SP. Normal range of motion of joints in male subjects. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1979;61(5):756–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss H. The measure of man; human factors in design. New York: Whitney Library of Design; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Fatone S, Hansen AH. Effect of ankle-foot orthosis on roll-over shape in adults with hemiplegia. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2007;44(1):11–20. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.08.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AP. Discovering statistics using SPSS for Windows : advanced techniques for the beginner. London ; Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gard SA, Childress DS. What determines the vertical displacement of the body during normal walking? Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics. 2001;13(3):64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gard SA, Miff SC, Kuo AD. Comparison of kinematic and kinetic methods for computing the vertical motion of the body center of mass during walking. Hum Mov Sci. 2004;22(6):597–610. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AH. Thesis (Ph D, Biomedical Engineering) Evanston, IL: Northwestern University; 2002. Roll-over characteristics of human walking with applications for artificial limbs. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AH, Childress DS. Effects of shoe heel height on biologic rollover characteristics during walking. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2004;41(4):547–554. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2003.06.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AH, Childress DS. Effects of adding weight to the torso on roll-over characteristics of walking. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2005;42(3):381–390. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2004.04.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AH, Childress DS, Knox EH. Roll-over shapes of human locomotor systems: effects of walking speed. Clinical Biomechanics. 2004;19(4):407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AH, Meier MR, Sam M, Childress DS, Edwards ML. Alignment of transtibial prostheses based on roll-over shape principles. Prosthetics and Orthotics International. 2003;27(2):89–99. doi: 10.1080/03093640308726664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AH, Meier MR, Sessoms PH, Childress DS. The effects of prosthetic foot roll-over shape arc length on the gait of trans-tibial prosthesis users. Prosthetics and Orthotics International. 2006;30(3):286–299. doi: 10.1080/03093640600816982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadaba MP, Ramakrishnan HK, Wootten ME. Measurement of lower extremity kinematics during level walking. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1990;8(3):383–392. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox EH. Thesis (Ph D , Biomedical Engineering) Evanston, IL: Northwestern University; 1996. The role of prosthetic feet in walking. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber RL. Statistical significance and statistical power in hypothesis testing. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1990;8(2):304–309. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100080221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer T. Passive dynamic walking. The International Journal of Robotics Research. 1990;9:62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Morawski JM, Wojcieszak I. Biomechanics VIA Int Series on Biomechanics. University Park Press; 1978. Miniwalker - a resonant model of human locomotion. [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. Gait analysis : normal and pathological function. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Saha D, Gard S, Fatone S, Ondra S. The effect of trunk-flexed postures on balance and metabolic energy expenditure during standing. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32(15):1605–1611. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318074d515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sam M, Childress DS, Hansen AH, Meier MR, Lambla S, Grahn EC, Rolock JS. The 'shape&roll' prosthetic foot: I. Design and development of appropriate technology for low-income countries. Medicine, Conflict and Survival. 2004;20(4):294–306. doi: 10.1080/1362369042000285937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisse M, van Frankenhuyzen J. Design and Construction of MIKE; a 2D autonomous biped based on passive dynamic walking. In: Kimura H, Tsuchiya K, editors. Adaptive Motion of Animals and Machines. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; 2006. ISBN-10 4-431-24164-7. [Google Scholar]