Abstract

Associative learning induces plasticity in the representation of sensory information in sensory cortices. Such high-order associative representational plasticity (HARP) in the primary auditory cortex (A1) is a likely substrate of auditory memory: it is specific, rapidly acquired, long-lasting and consolidates. Because HARP is likely to support the detailed content of memory, it is important to identify the necessary behavioral factors that dictate its induction. Learning strategy is a critical factor for the induction of plasticity (Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010b). Specifically, use of a strategy that relies on tone onsets induces HARP in A1 in the form of signal-specific decreased threshold and bandwidth. The present study tested the hypothesis that the form and degree of HARP in A1 reflects the amount of use of an “onset strategy”. Adult male rats (n = 7) were trained in a protocol that increased the use of this strategy from ~20% in prior studies to ~80%. They developed signal-specific gains in representational area, transcending plasticity in the form of local changes in threshold and bandwidth. Furthermore, the degree of area gain was proportional to the amount of use of the onset strategy. A second complementary experiment demonstrated that use of a learning strategy that specifically did not rely on tone onsets did not produce gains in representational area; but rather produced area loss. Together, the findings indicate that the amount of strategy use is a dominant factor for the induction of learning-induced cortical plasticity along a continuum of both form and degree.

Keywords: Associative learning, Neurophysiology, Primary auditory cortex, Receptive field, Representation

1. Introduction

That memories are stored in the cerebral cortex is not in dispute. The approaches to identify mnemonic storage in the cortex vary considerably, including techniques as diverse as drawing inferences from brain lesions to functional imaging and electrophysiological recording. Most electrophysiological studies of learning and memory seek correlates, such as the development of physiological plasticity to a particular sensory signal during a learning task. However, as memories have content, i.e., they comprise information about specific events, an alternative approach is needed to determine the extent to which the plasticity constitutes the representation of specific acquired information.

A synthesis of sensory neurophysiology methodology with learning paradigms in hybrid experimental designs has provided such representational information. Instead of determining changes in cortical processing only of signal stimuli, sensory physiological methods provide for the determination of systematic changes in the representation of a stimulus dimension, e.g., by providing receptive fields for a dimension of the sensory signal. This approach is particularly applicable to primary auditory, somatosensory and visual cortical fields because they each contain a topographic representation of one or more stimulus dimensions. It is equally applicable to any cortical field for which the functional and spatial organizations are known. Hence, it is possible to determine if using a particular stimulus value as a signal within the “mapped” dimension produces a specific change in signal processing and representation within that dimension.

This approach has been employed most extensively in studies of acoustic frequency representation in the primary auditory cortex (A1). These experiments first revealed that associative learning actually shifts the tuning of cells in the primary auditory cortex from their original best frequencies (BF) to the frequency of a signal tone (Bakin & Weinberger, 1990). Such associative tuning shifts can produce an increase in the area of representation of the signal-frequency within the tonotopic map of A1 (Hui et al., 2009; Recanzone, Schreiner, & Merzenich, 1993; Rutkowski & Weinberger, 2005). Receptive field and larger-scale map learning-induced plasticities in the cerebral cortex are referred to collectively as “high-order (cortical) associative representational plasticity” (HARP).

The search for cortical storage underlying memory is further advanced by a comprehensive determination of the attributes of HARP. Thus, most studies of neural correlates demonstrate that they are of associative origin, i.e., reflect the contingency between the conditioned signal stimulus (CS) and a reward or punishment (e.g., Byrne & Berry, 1989; Morrell, 1961; Thompson, Patterson, & Teyler, 1972). However, if the candidate plasticity is part of the substrate of an associative memory, then it should have all of the major attributes of behavioral associative memory. In this regard, the study of acoustic frequency in A1 is currently the only stimulus dimension that has been adequately so characterized. Studies of frequency receptive fields (RFs) (“tuning curves”) have shown that they exhibit all of the major characteristics of associative memory. Signal-specific tuning shifts not only are associative, but also can develop rapidly (within five trials), consolidate (become stronger over hours and days) and exhibit long-term retention (tracked to two months). Additionally, frequency-tuning shifts are discriminative, i.e., shifts are toward reinforced frequencies (CS+) but not toward unreinforced tones (CS−). Finally, HARP in the form of tuning shifts is highly specific, often confining increased response to the signal-frequency plus or minus a small fraction of an octave (reviewed in Weinberger, 2007; see also Calford, 2002; Merzenich et al., 1996; Palmer, Nelson, & Lindley, 1998; Rauschecker, 2003; Syka, 2002).

HARP for acoustic frequency develops in all types of learning studied, including one-tone and two-tone discriminative classical and instrumental conditioning (Bakin, South, & Weinberger, 1996; Blake, Strata, Churchland, & Merzenich, 2002; Edeline & Weinberger, 1992, 1993) and with both aversive (e.g., Bakin & Weinberger, 1990) and appetitive conditioning (e.g., Recanzone et al., 1993) including rewarding self-stimulation (Hui et al., 2009; Kisley & Gerstein, 2001). Moreover, HARP for frequency develops in all taxa studied to date: guinea pig [Cavia porcellus] (Bakin & Weinberger, 1990), echolocating big brown bat [Eptesicus fuscus] (Gao & Suga, 1998, 2000), cat [Felis catus] (Diamond & Weinberger, 1986), rat [Rattus rattus](Hui et al., 2009; Kisley & Gerstein, 2001), Mongolian gerbil [Meriones unguiculatus](Scheich & Zuschratter, 1995) and owl monkey [Aotus trivirgatus boliviensis] (Recanzone et al., 1993). HARP is not limited to non-human animals. The same paradigm of classical conditioning (tone paired with a mildly noxious stimulus) produces concordant CS-specific associative changes in the primary auditory cortex of humans (Molchan, Sunderland, McIntosh, Herscovitch, & Schreurs, 1994; Morris, Friston, & Dolan, 1998; Schreurs et al., 1997).

HARP has been reported for acoustic dimensions other than sound frequency, including stimulus level (Polley, Heiser, Blake, Schreiner, & Merzenich, 2004), rate of tone pulses (Bao, Chang, Woods, & Merzenich, 2004), envelope of frequency modulated (FM) tones (Beitel, Schreiner, Cheung, Wang, & Merzenich, 2003), direction of FM sweeps (Brechmann & Scheich, 2005), tone sequences (Kilgard & Merzenich, 2002), and auditory localization cues (Kacelnik, Nodal, Parsons, & King, 2006) (for review see Keuroghlian and Knudsen (2007) and Weinberger (2010, chap. 18)). We continue to focus on acoustic frequency because it is by far the best-characterized dimension in sensory associative learning.

However, learning itself is not sufficient to induce specific plasticity. Rather, we discovered that the type of learning strategy employed to solve a task appears to be critical for the formation of HARP in A1 (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008). Learning strategy refers to the complex, multi-dimensional behavioral algorithms that animals employ to solve problems. Specific learning strategies are defined here with terms used as convenient descriptors to highlight the acoustic components of each learning strategy. Thus, they necessarily leave out non-auditory elements like the use of a visual error-cue signal. As memories are probably distributed in the cerebral cortex, it is likely that plasticity for critical components of a learning strategy develop in distributed cortical areas. Here, we focus on how the auditory components of learning strategies dictate HARP in the primary auditory cortex.

In prior studies, groups of rats were trained to bar-press to obtain water rewards contingent on the presence of a signal tone and inhibit bar-presses during silent inter-trial-intervals to avoid error-signaled time-out periods. Although this task appears to be simple, it can be solved in various ways. We identified two learning strategies that animals employed. Subjects could depend on tone onset to initiate bar-pressing and continue until receiving an error signal, while ignoring tone offset. We refer to this strategy as “tone-onset-to-error” or TOTE. Alternatively, subjects could begin responding at tone onset but use the tone offset as a cue to stop bar-pressing, and thus not receive error signals, a “tone-duration” (T-Dur) strategy. The two learning strategies could be distinguished only by analysis of the pattern of bar-presses around and during the presentation of the tone during training trials. Animals using TOTE continue to bar-press immediately after tone offsets while animals using T-Dur do not continue bar-pressing. We found that use of the TOTE learning strategy predicted the development of HARP in the form of signal-specific decreases in threshold and bandwidth. Moreover, the use of the TOTE-strategy was a better predictor of HARP than either the level of correct performance or the degree of motivation. In contrast, use of the T-Dur strategy, regardless of performance or motivation level, never resulted in detectable HARP (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008; Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010a, 2010b). These findings support the view that a learning strategy which emphasizes tone onsets, while largely ignoring tone offsets, can be a critical factor in the formation of learning-induced plasticity in the primary auditory cortex.

We hypothesize a continuum on which the degree of tone onset use (or disuse) dictates the amount of HARP in A1: the greater the use of an onset strategy, the greater the magnitude of HARP. Individual subjects may adopt a learning strategy to varying degrees. Thus, the extent to which HARP develops may depend upon the extent to which a tone-onset strategy is employed. We have suggested that frequency-specific local threshold and bandwidth reductions that were previously shown to be dependent on the use of the TOTE learning strategy may be an initial form of HARP in A1 (Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010b). The next levels of HARP might be local, and ultimately global tuning shifts that underlie specific gains in representational area within the tonotopic map. Thus, if the use of tone onsets in the TOTE-strategy is critical for the induction of HARP, and the amount of TOTE use dictates the degree of HARP, then a greater use of TOTE should produce signal-specific plasticity that surpasses local changes in threshold and bandwidth, to induce gains in representational area. In contrast, without the use of tone onset, the signal would not gain representational area.

Two experiments were used to test the hypothesis that HARP in A1 is dictated by the use of tone onsets. The main goal of the first experiment was to increase animals' use of tone onsets by increasing their use of the TOTE-strategy. To be specific:

Experiment 1 – If subjects increase their use of the TOTE strategy to solve the problem of obtaining rewards to tones, then they will develop an enhanced form of plasticity, namely signal-specific increases in area of representation within the primary auditory cortex.

The second experiment complements the first in that the goal was to decrease the use of tone onsets. Insofar as previous findings indicated a lack of HARP in A1 when animals use a learning strategy based on beginning to bar-press at tone onset and stopping at tone offset (T-Dur) (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008), we investigated the effect of a learning strategy that relies only on tone offset (R-Off, as explained later), specifically:

Experiment 2 – If subjects rely on the use of tone offset, and not tone onset, to solve the problem of obtaining rewards to tones, then they will not develop signal-specific representational enhancements within the primary auditory cortex, but might instead develop some representational decreases.

2. Experiment 1: Increasing use of the TOTE-strategy

To increase use of the TOTE-strategy, we increased the probability that animals would ignore tone offset, i.e., continue to bar-press after tone offset. This was achieved with the addition of a “Free Period” (≤7 s) that started at tone offset. Correct bar-presses during the tone generated a Free Period on that trial, during which the first bar-press was rewarded. Thus, animals were more likely to ignore tone offset, bar-press to obtain the Free Period reward, and continue bar-pressing until receiving an error signal.

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Post-tone Free Period (PostFP) subjects

The subjects were 7 male Sprague–Dawley rats (300–325 g, Charles River Laboratories; Wilmington, MA), housed in individual cages in a temperature controlled (22 °C) vivarium and maintained on a 12/12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 am PDT) with ad libitum access to food and water before the onset of training. They were handled daily and retained in the vivarium for a minimum of one week prior to any treatments. All procedures were performed in accordance with the University of California Irvine Animal Research Committee and the NIH Animal Welfare guidelines.

Subjects were placed on water restriction to maintain their weight at ~85% compared to unrestricted litter controls. Home-cage water supplements were given when necessary to maintain weight but water was not available for 12 h preceding a training session in order to maintain motivation. All rats had ad libitum access to food throughout the training period. In addition, cortical mapping data were available from a group of naïve rats of the same age and size (n = 9), as previously reported (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008).

2.1.2. Behavioral training apparatus

The training apparatus has been described previously (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008). Training was conducted in an instrumental conditioning chamber (H10-11R, Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, PA) contained within a sound-attenuating enclosure (H10-24A, Coulbourn). The chamber contained a bar (2 cm above floor, 2 cm from right wall, protruding 1.75 cm), a water cup attached to a lever (H14-05R, Coulbourn) that could deliver 0.1 ml of water to an opening 9 cm to the left of the bar (H21-03R, Coulbourn), a speaker (H12-01R, Coulbourn) 13 cm above this opening, and an overhead house light (H11-01R, Coulbourn). The speaker was calibrated for three locations at animal head height in the mid-line front (nearest the water dipper), center and rear of the training chamber.

2.1.3. Behavioral training for an increased use of the TOTE learning strategy

Prior studies have shown that animals making moderate use of the “TOTE” strategy to learn to bar-press to tones develop signal-specific HARP in tuning threshold and bandwidth decreases (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008). Experiment 1 tested the hypothesis that HARP would develop in the form of signal-specific gains in area of the primary auditory cortex (A1), provided that animals increase the probability of using tone onsets, and thus the TOTE-strategy, across trials, i.e., rely more on the use of tone onset as the cue to start bar-pressing and continue to bar-press after tone offset until receiving an error signal.

First, rats (“post-tone free-period” group, PostFP) were shaped to bar-press for water reward during five daily 45 min sessions on a free operant schedule (1:1). The water cup was available for 5 s. Tones were not presented during shaping. Next, they were trained on a protocol that promoted a learning strategy dependent upon the tone onset cue (see below). During training, rewards were given on each trial for bar-presses made during the presence of a 10 s pure tone stimulus (tone signal = 5.0 kHz, 70 dB SPL) and during a silent “Free Period” that immediately followed the tone offset and lasted up to 7 s. A maximum of two rewards could be delivered for bar-presses during the 10 s signal tone and a maximum of one reward could be obtained during a Free Period (Fig. 1, Case 1). Only the first bar-press during the Free Period was rewarded; all subsequent bar-presses were unrewarded and produced an error signal, which consisted of a flashing house light (200 ms on/off) throughout the duration of a time-out period, i.e., lengthening of time to the next trial. The time-out period was brief (3 s) for the first 4 days, to enable learning, and increased to 7 s for the remainder of training. Bar-presses during a time-out period initiated another time-out period until bar-presses were withheld for the duration of at least one complete time-out period. BPs made during the remaining duration of inter-trial intervals (ITI) were signaled as errors and penalized with time-outs with a 50/50 probability (ITI first 4 days = 4–12 s, thereafter = 5–25 s, random schedule). The proportion of bar-presses during the inter-trial interval that were actually penalized with time-outs during the course of training was 75.9 ± 5.5% due to occasions of repeated errors (loops of time-outs) as illustrated in Fig. 1, Case #5.

Fig. 1. PostFP training protocol and the TOTE pattern of behavior.

The Free Period occurs immediately after the presentation of the tone in the PostFP protocol. Animals using the TOTE-strategy will begin bar-pressing to the onset of the tone persist immediately after the tone during the Free Period, and continue to bar-press during the inter-trial interval immediately following the last reward until the flashing light error signal cues them to cease. Case 1 exemplifies the TOTE pattern of behavior. However, several patterns of behavior were possible with PostFP training that could result in three, two, one, or no rewards. Case 1 shows a pattern of bar-pressing that results in 3 rewards. Case 2 shows a pattern that also results in 3 rewards, however note the longer latency to bar-press during the Free Period: bar-press (e) in Case 2 occurs at the same time relative to the tone as bar-press (d) in Case 1, however this bar-press is either rewarded, or signaled as an error, respectively. Recall that only the first bar-press within the 7 s Free Period window is rewarded and the next bar-press is always signaled as an error. Case 3 shows a situation where only 2 rewards are delivered because only one bar-press was made during the tone. Again, note the different outcomes for bar-press (g) and bar-presses (e) and (d). Case 4 shows a pattern of response that results in the delivery of only one reward. No responses were made during the Free Period. Note that bar-press (g) is signaled as an error as the first bar-press during the inter-trial interval after the last rewarded bar-press the animal received. Case 5 demonstrates that PostFP subjects are required to bar-press at least once during the tone in order to receive an opportunity for reward during the Free Period. Contrast bar-press (c) with bar-press (b) in Case 3 and (a) in Case 1; all responses occur at the same time relative to the tone, but only the latter two bar-presses are rewarded. Case 5 also demonstrates a situation in which bar-presses continue during the error-signal time-out period. Each bar-press within the time-out duration initiates a new time-out period until bar-presses are withheld for at least one complete time-out duration. Asterisks across Cases 1–5 show that the delivery of errors during ITIs are randomly scheduled for 50% of inter-trial interval bar-presses. Only the first bar-press during an inter-trial interval after the last reward period is signaled as an error 100% of the time.

Training with tones was conducted 5 days/week and continued until asymptotic level of performance, defined as four consecutive days during which the performance coefficient of variation (CV = standard deviation/mean) was ≤0.10 (see performance calculation below).

The use of a TOTE learning strategy is evident when animals begin bar-pressing to the tone onset and continue bar-presses after tone offset until the delivery of an error signal. This could be manifest by two rewarded bar-presses during the signal tone and one rewarded bar-press during the free period after tone offset. However, other behavioral patterns are possible. Fig. 1 presents exemplar scenarios. Cases 1 and 2 yield three rewards. Cases 3, 4 and 5 yield two, one or no rewards, respectively. Use of the TOTE-strategy on a trial is evident when a subject bar-presses to receive at least one reward during the signal tone, one reward during the post-tone Free Period, and continues bar-pressing until receiving an error signal during the inter-trial-interval. Cases 1, 2 and 3 satisfy this criterion.

2.1.4. Recording and analysis of behavior: performance and use of TOTE-strategy

All stimuli and responses were recorded using Graphic State II (Coulbourn) software and subsequently analyzed using custom Matlab R2009a software. Measures of behavior are provided in Section 2.2.

2.1.5. Recording and analysis of behavior: frequency generalization

Frequency general gradients were constructed from responses obtained in a single session 24 h after the last day of training. Frequency generalization sessions began with ten signal-frequency rewarded trials to ensure that animals remained motivated to bar-press. Generalization trials were initiated without a break in the session. Due to the potential that responses during the transition between rewarded and unrewarded trials were influenced by arousal, the first block of generalization trials was removed from the analysis of the generalization. Six frequencies were tested: the signal tone of 5.0 kHz and non-signal frequencies of 2.8, 7.5, 12.9, 15.8 and 21.7 kHz, all at 70 dB SPL. They were presented in a pseudo-random order to yield 25 trials for each frequency (150 trials total). Tone durations were 10 s, 70 dB SPL as during prior training, but no rewards were given. Because rewards were not administered during the generalization session, Free Periods were absent as were error signals for bar-presses during silence. All stimuli and responses were recorded using Graphic State II (Coulbourn) software and subsequently analyzed using custom Matlab R2009a software. The calculation for frequency generalization gradients is provided in Section 2.2.

2.1.6. Neurophysiological mapping of A1

Complete mapping of A1 was performed after training and testing in a terminal session to obtain a comprehensive analysis of potential cortical plasticity in the functional properties and organization of A1. An additional group of untrained naïve animals (n = 9) was mapped as a comparison group to determine the effects of training on A1 responses and organization. Detailed mapping methods were the same as those standard in the field (e.g., Sally & Kelly, 1988) and reported in previous publications (e.g., Berlau & Weinberger, 2008; Hui et al., 2009; Rutkowski, Miasnikov, & Weinberger, 2003; Rutkowski & Weinberger, 2005). Rats were anesthetized (sodium pentobarbital, 50 mg/kg, i.p.) with supplemental doses (15 mg/kg, i.p.) administered as needed to maintain suppression of reflexes. Bronchial secretions were minimized by treatment with atropine sulfate (0.4 mg/kg, i.m.) and core body temperature maintained at 37 °C via a feedback heating blanket and rectal probe. Each animal was placed in a stereotaxic frame inside a double-walled sound attenuated room (Industrial Acoustics Co., Bronx, NY) and the skull fixed to a support via spacers embedded in a pedestal previously made using dental cement, leaving the ear canals unobstructed. A craniotomy was performed and the cisterna magna drained of cerebrospinal fluid. After reflection of the dura, warmed saline was applied to the cortical surface intermittently throughout the mapping procedure to prevent desiccation. Calibrated photographs of the cortical surface were taken with a digital camera to record the position of each microelectrode penetration. These images were later super-imposed to create a plot map of relative penetration locations across the cortical surface.

Acoustic stimuli were delivered to the contralateral ear in an open-field with the speaker placed 2–3 cm from the ear canal. The stimuli consisted of broadband noise (bandwidth = 1–50 kHz, 0–80 dB SPL in 10 dB increments, 20 repetitions) and pure tone bursts (50 ms, cosine-squared gate with rise/fall time [10–90%] of 7 ms, 0.5–54.0 kHz in quarter-octave steps, 0–80 dB SPL in 10 dB increments). Stimuli were presented once every 700 ms with noise- or frequency-level combinations pseudo-randomized by Tucker-Davis Technologies (TDT, Alachua, FL) System 3 software. Frequency response areas (FRA) were obtained at each cortical locus using 10 repetitions of the frequency/level-stimulus set (252 stimuli in total).

Extracellular recordings of multiunit clusters were made with a linear array of 4 parylene-coated microelectrodes (1–4 MΩ, FHC, Bowdoin, ME) that were lowered to layers III–IV, perpendicular to the surface of the cortex (400–600 μm deep) via a stepping microdrive (Inchworm, model 8200, EXFO Burleigh Instruments, Victor, NY). Neural activity was amplified (1000×), band-pass filtered (0.3–3.0 kHz, TDT RA16 Medusa Base Station) and monitored on a computer screen and loudspeaker system (model AM8, Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA). Only discharges having ≥2:1 ratio were included in analyses. Responses to noise bursts were recorded before tone stimuli were presented. Responses to noise were later compared with responses to tones at each site as evidence for the borders of A1. A1 was physiologically defined as having a caudal–rostral, low–high frequency tonotopic organization with thresholds for pure tones being lower than for noise (Sally & Kelly, 1988). Complete mapping of A1 generally required 60–80 penetrations over a period of 8–12 h.

2.1.7. Neurophysiological analyses

Frequency response areas (FRAs) were constructed offline for evoked spike-timing data using custom Matlab R2009a software. Tone-evoked discharges during a selected response-onset time window (6–40 ms time window after tone onset) were defined for each stimulus presentation as a spike rate that was greater than the spontaneous rate during the 50 ms immediately preceding the presentation of a tone.

FRAs were constructed for all recording sites. The FRAs yielded characteristic frequency (CF) (i.e., the frequency at threshold). The CF of a responsive site was defined as the stimulus frequency having the lowest threshold (CF threshold) for an evoked response (i.e., highest sensitivity). We used CFs to calculate the cortical area of representation for half-octave CF bands. Areas were determined by constructing CF distribution maps in Voronoi tessellations to represent the areal distribution of CF bands (≤1.5, 1.6–2.0, 2.1–3.0, 3.1–4.0, 4.1–6.0 (tone signal-band), 6.1–8.0, 8.1–12.0, 12.1–16.0, 16.1–24.0 and 24.1–32.0 kHz). The percentage of the total area of A1 that each band occupied was calculated for each animal before determining a group average for each CF band.

2.1.8. Statistics

All behavioral and neuronal response parameters were analyzed using ANOVA (α = 0.05) with post hoc Fisher's PLSD, or repeated measures ANOVA (α = 0.05) for analyses across training sessions with post hoc Holm–Sidak tests. Where appropriate for group comparisons of A1 responses or bar-pressing behavior, t-tests (α = 0.05) were performed as indicated. Tests for directional changes (i.e., gains of CF area in A1) were one-tailed t-tests. The Bonferroni procedure was used when necessary to correct for multiple comparisons (e.g., across CF bands), as in the past (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008; Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010b; Rutkowski & Weinberger, 2005). Analyses were executed using Matlab R2009a statistical packages.

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Behavior: the TOTE-strategy

The importance of tone onset use for the development of HARP would be demonstrated if signal-specific gains in cortical area were present after subjects made greater use of the TOTE-strategy than in previous experiments in which plasticity was confined to increased tuning sensitivity and selectivity (decreases in threshold and bandwidth, respectively) (i.e., Berlau & Weinberger, 2008; Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010a, 2010b).

To determine if the subjects learned to solve the problem of obtaining rewards during tones, we determined their performance level:

where # tone BPs = the total number of bar-presses made during the tone, and # error BPs = the total number of bar-presses made during an ITI. Responses made during Free Periods were excluded from this calculation.

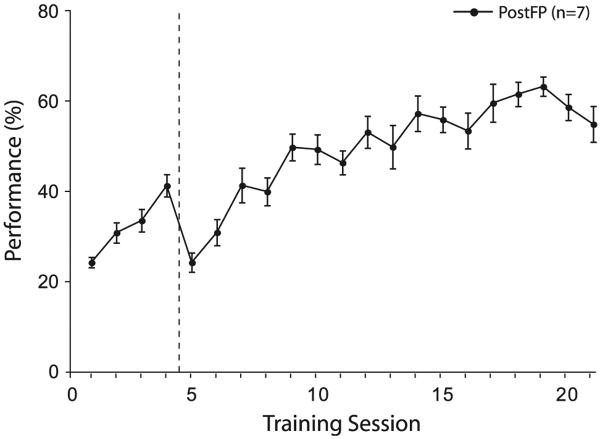

The group successfully acquired the task of bar-pressing during the signal tone for water reward (F(20,146) = 20.9; p < 0.0001) and reached asymptote after 25.9 sessions (±7.3 s.e.). The level of asymptotic performance was 57.7% (±1.8 s.e.) (Fig. 2). Performance was modest due to the persistence of bar-presses during silent inter-trial interval periods. Bar-presses during silence were prevalent in PostFP subjects because the protocol made periods between tones ambiguous: bar-presses could be inconsequential, result in error signals (i.e., because only half of inter-trial interval bar-presses were signaled as errors) or result in reward (i.e., during rewarded Free Periods). Although asymptotic performance was modest, the main goal of the PostFP protocol was not to maximize performance, but to encourage use of the TOTE learning strategy.

Fig. 2. PostFP group performance.

Performance ([# tone BPs/(# tone BPs + # error BPs)] × 100%) increases across sessions until reaching an asymptote of 57.7% (±1.8 s.e.) over the last four training sessions. Dashed line indicates shift in protocol from short inter-trial interval durations (first four days = 4–12 s, random schedule), to long inter-trial interval durations (5–25 s, random schedule).

To determine the degree of TOTE-strategy use, we calculated a “Learning Strategy Index” (LSI) for each session as follows:

As noted in Section 2.1, a TOTE pattern of behavior consists of at least one bar-press during the tone signal, one during the Free Period and a bar-press immediately after the end of the Free Period to initiate an error signal (i.e., pattern of response shown in Fig. 1, Cases 1, 2 and 3).

There was a systematic increase in the LSITOTE across training sessions (F(16,118) = 6.78; p < 0.0001) until reaching an asymptote on day 5 of 79.8% (±4.0 s.e.), (Holm–Sidak post hoc: days >5 are not significantly different, p > 0.05). Therefore, the PostFP group employed the TOTE-strategy increasingly and to a high level across sessions (Fig. 3; Fig. S1A).

Fig. 3. TOTE behavior in the PostFP group.

The PostFP learning strategy index (LSITOTE) increases with training. The proportion of trials with TOTE patterns of response increases until session 5 when the group is at an asymptote of 79.8% (±4.0 s.e.).

Frequency generalization gradients obtained during a single extinction session 24 h after the last day of training indicated the level of frequency-specificity of learning. Bar-presses for each of the six test frequencies (Section 2.1) were calculated as the proportion of all responses made during the generalization session. Group responses were different across frequency (F(5,41) = 3.65, p < 0.01), with the peak of the gradient near the signal-frequency (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. PostFP group's frequency generalization gradient.

The PostFP group learned about specific frequency. Subjects showed a peak in response at (5.0 kHz) or near (7.5 kHz) the signal-frequency.

2.2.2. Acoustic representation in A1: CF distribution across cortical area

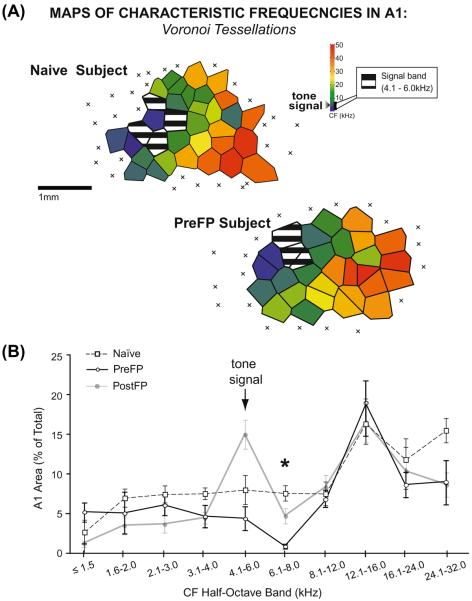

The second aim of Experiment 1 was to determine whether the PostFP group would develop a specific gain in representational area if it adopted a greater use of the TOTE-strategy than in previous studies. We compared the distribution of characteristic frequencies across cortical area in A1 in this group to a group of naïve rats (n = 9). Half-octave CF band analyses of cortical area within A1 revealed a representational gain in area (Fig. 5). The gain was specific to the signal tone frequency (t-test, 4.1–6.0 kHz CF band: t(14) = 3.82, p < 0.001; other bands were not significant; Table 1). The gain in area roughly doubled the representational area in A1 for the signal tone compared to that of naïves, from 7.67% (±1.62) to 15.13% (±1.85) relative area in A1. Therefore, the PostFP group developed HARP in the form of a gain in representational area in A1 that was highly specific to the signal tone frequency.

Fig. 5. Representation of frequency across A1 in the PostFP group.

(A) Example map of characteristic frequency (CF) from a PostFP subject shows an increase in signal-area relative to a naïve subject. Striped polygons show the area of representation of the signal-frequency within a half-octave band. (B) The amount of area for the signal-frequency was determined relative to the size of A1 (y-axis, % of total). CF distributions in half-octave bands reveal a significant area gain in the signal-frequency band in the PostFP group compared to the naïve group only for the signal-frequency (asterisk). The gain roughly doubled the area of representation for the signal-frequency from 7.67% (±1.62 s.e.) in naïves to 15.13% (±1.85 s.e.) in PostFP subjects.

Table 1.

The specificity of HARP in A1 area gain in the PostFP group. Statistical tests for gains in A1 area relative to the naïve group are shown for each half-octave CF band.

| CF half-octave band |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1.5 | 1.6–2.0 | 2.1–3.0 | 3.1–4.0 | 4.1–6.0 (signal tone) | 6.1–8.0 | 8.1–12.0 | 12.1–16.0 | 16.1–24.0 | 24.1–32.0 | |

| PostFP % area (mean ± s.e.m.) | 1.28 (±1.53) | 3.54 (±1.14) | 3.71 (±1.09) | 4.52 (±0.74) | 15.13 (±1.85) | 4.76 (±0.97) | 8.43 (±1.51) | 16.68 (±2.59) | 10.44 (±2.67) | 8.73 (±1.55) |

| Naïve % area (mean ± s.e.m.) | 2.31 (±1.14) | 6.65 (±1.24) | 7.11 (±1.08) | 7.20 (±0.41) | 7.67 (±1.62) | 7.24 (±1.30) | 7.19 (±1.46) | 16.08 (±2.78) | 11.52 (±1.70) | 15.23 (±2.67) |

| Difference in % area (PostFP–Naïve) | −1.02 | −3.10 | −3.40 | −2.68 | +7.47* | −2.49 | +1.24 | +0.60 | −1.09 | −6.50 |

| t-Value: t(14) | 0.25 | −0.84 | −1.49 | −1.57 | 3.82 | −1.45 | 0.59 | 0.15 | −0.36 | −1.30 |

p < 0.001; all other tests are non-significant (p > 0.05).

2.2.3. Increased use of TOTE use predicts enhanced HARP in A1

Specific cortical plasticity in associative learning can be manifest in a variety of forms from signal-specific changes in tuning bandwidth and threshold without A1 area reorganization to signal-specific gains in area. Furthermore, forms of plasticity can vary in degree as in the amount of increase in representational area. In previous experiments, groups of animals using the TOTE learning strategy developed HARP in the form of a signal-frequency-specific decrease in absolute threshold and bandwidth (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008; Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010b). The hypothesized dependence of HARP in A1 on tone onset use predicts an increase in the representational are of the signal-frequency if the PostFP group made greater use of the TOTE-strategy than the previous groups.

A direct comparison of the amount that prior groups and the PostFP group used the TOTE-strategy is presented in Fig. 6. Groups of animals from prior studies (“B&W 2008” and “B&W 2010” in Fig. 6) used the TOTE-strategy ~15–20% of the time at asymptote, i.e., showed a TOTE pattern of behavior about one out of every five trials once the task was learned. These groups developed increases in tuning sensitivity and selectivity without any changes in representational area. In contrast, the PostFP animals showed a fourfold increase in the use of the TOTE-strategy, i.e., ~80% of trials. This group's greatly increased use of the TOTE-strategy occurred with a qualitative change in plasticity, i.e.,an area gain for the signal-frequency, rather than a decrease of threshold and bandwidth (increased sensitivity and selectivity, respectively). Thus, enhanced HARP in A1 was found with greater use of the TOTE-strategy, supporting the hypothesis that the degree of tone onset use dictates HARP in A1.

Fig. 6. Specific plasticity in A1 is enhanced with greater use of the TOTE-strategy.

Prior groups learning with the TOTE-strategy [“B&W 2008” (Berlau and Weinberger, 2008) and “B&W 2010” (Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010b)] developed HARP in the form of increases in tuning sensitivity and selectivity for the signal-frequency. Greater use of the TOTE-strategy in PostFP subjects induced a transition to a higher form of HARP in gains in area for the signal-frequency. LSITOTE is significantly different in all three groups (B&W 2008 vs. B&W 2010, t(12) = 4.01, p < 0.01; PostFP vs. B&W 2008, t(13) = 31.31, p < 0.0001; PostFP vs. B&W 2010, t(11) = 19.23, p < 0.0001; marked by asterisks) and predicts the degree of HARP in A1. The first form of HARP induces decreases in both threshold and bandwidth (BW) that are specific to the conditioned tone (CS). Such CS-specific tuning changes occur without any change in the cortical area of frequency representation (Berlau and Weinberger, 2008; Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010b). B&W 2008 animals developed a ~9.0 dB SPL decrease in threshold at CF, and a ~0.7 octave decrease in BW20 while B&W 2010 animals showed a ~8.5 dB SPL decrease in threshold and ~0.5 octave decrease in BW10, but no change in BW20. Modest use of the TOTE-strategy could induce HARP without area gain as an initial or primitive form of plasticity since the number of cells involved are limited (i.e., responses change only for those cells tuned to the signal-frequency). The second form of HARP induced by increased use of the TOTE-strategy is enhanced from the first. Because shifts in tuning of neighboring cells could underlie the gain in area of representation of the signal-frequency, this form of HARP involves more cells, i.e., those tuned both above and below the signal-frequency. Thus, changes in cortical representational area can be considered as an enhanced or higher level form of HARP.

2.2.4. Degree of TOTE use predicts amount of representational area in A1

The tone onset hypothesis for HARP in A1 also implies that greater use of the TOTE-strategy would lead to larger signal-specific area within the PostFP group. We evaluated the degree to which subjects used the TOTE-strategy by computing a stringent TOTE-Learning Index (TLI) from the pattern of responses during the ten rewarded test trials that began the stimulus generalization session. Test trials did not include Free Periods, so animals using the TOTE-strategy should continue to bar-press only once after tone offset and stop upon receiving an error signal. The index was calculated by determining the number of trials on which subjects bar-pressed during the tone and stopped after a single post-tone bar-press resulted in an error signal. A 5 s window beginning at tone offset was used in this assessment of TOTE-strategy because the group's latency to bar-press after tone offset had been <5 s throughout training (i.e., shorter than the duration of the Free Period; Fig. S1A). TLI values ranged from 0.0 to 0.9 on a scale from 0.0 to 1.0. It was computed as follows (the number of test trials for each subject was always 10):

The area of signal representation (±0.25 octaves) proved to be significantly positively correlated with the degree of TOTE use (r = 0.84, p < 0.01; Fig. 7). Thus, more tone onset use, indexed by increased use of the TOTE-strategy, was accompanied by a larger area of representation.

Fig. 7. The degree to which PostFP subjects use the TOTE-strategy correlates with the amount of area gain in A1.

A PostFP subject that uses a TOTE-strategy will have a pattern of response that begins with bar-presses after tone onset and continue until an error signal is received, without reference to the tone's offset. The degree of TOTE-strategy use was assessed by analyzing the behavior during 10 test trials without Free Periods to determine a TOTE-Learning Index (TLI). The TOTE-strategy could be assessed by the presence of a single bar-press within a 5 s post-tone interval that was not followed by subsequent responses. This pattern of behavior would reveal that animals used the error signal, and not the tone offset, to stop responding for rewards. A TLI value of 1.0 indicates the tone's offset was ignored and the error cue initiated by a single bar-press was used to withhold further responses. A value of 0.0 indicates that the tone's offset was used to withhold responding because bar-presses after the tone were absent. Thus, greater TLI values indicate greater use of the TOTE-strategy (x-axis). Greater use of the TOTE-strategy predicts larger gains of signal representation in A1 (r = 0.84, p < 0.01) (y-axis, relative area in A1 within a quarter-octave of the signal in individual PostFP subjects). Solid and dashed lines show the naïve group's average amount of relative area in A1 at the signal-frequency band (7.67 ± 1.62%).

2.3. Discussion

2.3.1. Increasing use of learning strategy enhances HARP

PostFP subjects employed the TOTE-strategy to a significantly greater degree than previous groups (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008; Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010b) as predicted. Most importantly, the increase in use of this “tone onset” strategy was accompanied by a frank increase in signal-specific representational area, rather than merely decreases in threshold and bandwidth. The area gain was highly specific to the half-octave centered on the signal-frequency. Additionally, greater use of the TOTE-strategy within the group resulted in larger gains of representational area for the signal-frequency. Therefore, these findings support the hypothesis that the amount of “onset use” dictates the form and degree of HARP, as revealed by the specific gains in representational area.

That the degree of a tone onset-based learning strategy (TOTE) is positively correlated with the amount of area gain in A1 extends the findings of Rutkowski and Weinberger (2005). They trained rats using three phases involving progressive decreases in duration of the tone signal over several weeks of training from 30 s to 10 s. Although learning strategy was not assessed, because this study predated discovery of the effects of this factor (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008), their protocol may have encouraged use of the TOTE-strategy. An efficient way for each subject to have ensured continued high levels of performance across different phases of training would be to adopt a consistent, effective learning strategy. The most common stimulus cue throughout training was tone onset, as tone durations (and therefore the expected time of offsets) changed across phases. Thus, greater use of a TOTE-strategy (“bar-press from tone onset until receiving an error signal”) would have been most effective and would produce better learning and higher levels of performance in their task. In accordance with this, Rutkowski and Weinberger found that better learning (and thus potentially greater use of TOTE) produced greater signal-specific gains in A1 area.

A comparison of TOTE-strategy use across studies shows that animals that developed area gains (i.e., PostFP subjects) rely more strongly on TOTE than groups that developed decreases in threshold and bandwidth. These findings suggest that the distinct forms of HARP are different degrees of a single process.

The initial stage of HARP induced by moderate TOTE use takes the form of decreases in threshold, bandwidth, or both. To date, we have observed these changes only concurrently and they develop in the absence of any actual change in the area of frequency representation (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008; Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010b). There may be varying degrees of HARP in the form of the magnitude and specificity of threshold and bandwidth changes even within modest levels of TOTE use because there was a significant difference in the use of TOTE between groups from prior studies (see Fig. 6). The apparent difference in TOTE use between the prior groups that were trained in the same protocol could be due to minor differences in duration of training, time of year or other individual influences that might affect the selection of learning strategy. In any event, such initial changes increase signal-specific sensitivity and selectivity, which should favor neural responses to the signal-frequency.

2.3.2. Progression of forms of HARP

HARP may take different forms along the relevant stimulus dimension. In addition to signal-specific increases in sensitivity and selectivity for tonal conditioned stimuli, other studies have reported HARP in the form of specific receptive field shifts in tuning directed to the frequency of the tonal conditioned stimulus (Bakin & Weinberger, 1990; Blake et al., 2002; Edeline & Weinberger, 1993; Galván & Weinberger, 2002; Gao & Suga, 2000; Kisley & Gerstein, 2001; Weinberger, Javid, & Lepan, 1993; see also Fritz, Elhilali, & Shamma, 2005; Fritz, Shamma, Elhilali, & Klein, 2003). Such tuning shifts observed across the entire tonotopic map of A1 would yield an increase in the representational area of the training frequency because tonotopic maps are a result of the distribution of tuning across the cortex. Indeed, prior studies of complete maps have found signal-specific gain in frequency representation (Hui et al., 2009; Recanzone et al., 1993; Rutkowski & Weinberger, 2005). Shifts in tuning and changes in area need not be limited to frequency. For example, area gains have been observed when the relevant stimulus dimension is sound level (Polley, Steinberg, & Merzenich, 2006). Moreover, representational plasticity could develop in non-contiguous cortical maps, e.g., “patches” of neurons with differing aural interactions (Schreiner, 1995). Thus, various forms of plasticity (e.g., bandwidth and threshold decreases, tuning shifts, and area gain) may be related in a progression through different stages of a single general process within any stimulus dimension depending on the degree to which HARP-inducing learning strategies are used to solve a behavioral problem.

In the present context of A1, the stage of HARP beyond threshold and bandwidth decreases that occurs with the increasing use of TOTE might be a shift of frequency tuning that is largely local. For example, cells originally tuned near the signal-frequency may shift to the signal stimulus, while cells originally tuned farther away might shift toward the signal-frequency later. In fact, this pattern has been found. In a study of long-term neural consolidation in A1, shifts from nearby frequencies had developed within an hour of the end of training whereas cells tuned to more distant frequencies shifted over a period of 3 days (Galván & Weinberger, 2002).

The next stage that is induced when an animal's use of TOTE is further increased appears to an increased area of representation of the signal-frequency. Within-group analysis of PostFP subjects shows that there are varying degrees of area gain, and that they are dependent on the use of TOTE. However, insofar as this is a correlation, the reverse is possible, i.e., that animals with greater potential for A1 areal reorganization are more likely to adopt a strong TOTE-strategy. This possibility requires investigation. Nonetheless, the current findings, combined with prior results (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008; Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010a, 2010b), support the schema of progression through stages of different forms of HARP in A1 that are directed by the degree to which a learning strategy that depends on tone onset is employed.

2.3.3. Duration of HARP

While receptive field frequency-tuning shifts in A1 have been shown to last at least 8 weeks (Weinberger et al., 1993), the present study is agnostic with respect to the long-term duration and stability of map reorganization. There may be a temporal dynamic of learning-related gains in representational area over time or with over-training. For example, increased representation (BOLD activity in V1 using fMRI) correlated with improvement in visual texture discrimination, yet later returned to normal values while improved behavior was maintained (Yotsumoto, Watanabe, & Sasaki, 2008). Future studies should address the temporal dynamics of HARP and its long-term relationship to behavioral performance.

2.3.4. The importance of tone onsets for the induction of HARP in A1

Previously, we hypothesized that the probability of forming plasticity in A1 using the TOTE-strategy is linked to the dominant ability of onset transients to elicit responses in A1 cells (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008). Specifically, we suggested that plasticity develops in cells that preferentially respond to acoustic cues that match the cues guiding their learning strategy. In short, A1 cells could develop specific plasticity during learning because their proclivity to respond to acoustic onset transients corresponds to the dominant use of the signal onset cue, i.e., use of the TOTE learning strategy.

This hypothesis is concordant with prior formulations. For example, natural sounds are often very brief (i.e., transient) and thus some regions of the auditory system are likely to be somewhat specialized to extract information from onset transients (Masterton, 1993; Phillips, Hall, & Boehnke, 2002). The primary auditory cortex appears to be such a specialized region because its cells are particularly responsive to onset transients (Coath & Denham, 2007; Eggermont, 2002; Heil, 2001; Phillips & Heining, 2002), and in fact are more sensitive and respond more robustly to onset transients than are cells in other auditory cortical fields (Heil & Irvine, 1998b; but see Qin, Chimoto, Sakai, Wang, & Sato, 2007 and Section 4.3 for discussion of A1 responses under different recording conditions).

More generally, there is ample evidence for specialization of response to different acoustic stimulus parameters in various auditory cortical fields. In addition to tonotopic organization in A1, orthogonal cortical representations exist for tonicity (i.e., either non- or monotonic) (Phillips, Semple, Calford, & Kitzes, 1994), binaural interactions (Middlebrooks, 1980), best sound intensity (Heil, 1994) and tuning bandwidth (Schreiner & Sutter, 1992). Functional specializations in fields outside of A1 also exist for intensity tuning in posterior auditory fields (Kitzes & Hollrigel, 1996; Phillips & Orman, 1984) or for more complex stimuli like frequency-modulated sweeps (Heil & Irvine, 1998a), including their direction and speed (Razak & Fuzessery, 2008; Schulze, Ohl, Heil, & Scheich, 1997). There is evidence for acoustic feature specialization in humans as well (e.g., for timbre and pitch: Langner, Sams, Heil, & Schulze, 1997; rhythm and melody: Patterson, Uppenkamp, Johnsrude, & Griffiths, 2002; and rhythm: Peretz et al., 1994; but see Vuust, Ostergaard, Pallesen, Bailey, & Roepstorff, 2009).

The organization of the auditory cortex into parameter-specific assemblages lends its utility for supporting HARP in terms of the acoustic features that animals select to underlie the strategies used to solve auditory problems. The selection bias for particular stimulus features and within-feature cues during learning could be influenced by the animal's developmental (e.g., species-specific proclivities) and training (e.g., experience) histories (Brown & Scott, 2006; Dahmen & King, 2007). Furthermore, plasticity may develop for other characteristics of the neural response to tonal stimuli, e.g., in temporal firing pattern as opposed to firing rate. Analyses to identify HARP after learning in the current study were restricted to the representation of frequency in A1 by firing rate, i.e., tuning threshold and bandwidth, and cortical tonotopic area. Thus, we do not assume that the measures reported here are the only correlates of auditory memory; the findings do not preclude the development of plasticity in other A1 response characteristics. However, we hypothesize that learning strategy is a critical factor in the development of any type of learning-related cortical plasticity. The particular characteristics of learning strategies that promote plasticity of one neural response characteristic over another await investigation. Ultimately, given specialization of cells for processing various parameters, we suggest that learning based on a strategy that emphasizes a parameter would promote plasticity in those cells.

3. Experiment 2: The R-Off strategy

To complement the prior experiment on increasing the use of tone onset, Experiment 2 used a protocol that aimed to decrease the use of tone onset. Thus, if subjects actually do not rely on “onset”, then they should not develop signal-specific area gain.

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Pre-tone Free Period (PreFP) subjects

The subjects were 8 male Sprague–Dawley rats (300–325 g; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) and were treated identically to subjects in Experiment 1 prior to tone training.

3.1.2. Behavioral training apparatus

The training apparatus was the same as that used in Experiment 1.

3.1.3. Behavioral training for an R-Off learning strategy

Subjects were shaped as described in Experiment 1. Next, they were trained in a protocol that promoted a learning strategy dependent upon the tone offset cue (see below). During training, rewards were given on each trial for bar-presses made during the presence of a 10 s pure tone stimulus (tone signal = 5.0 kHz, 70 dB SPL) and during a silent Free Period. The Free Periods immediately preceded the onset of the signal tone and occurred with the delivery of a single reward after a bar-press. A maximum of two rewards could be delivered for bar-presses during the 10 s signal tone that immediately followed (Fig. 8A). Training with tone was conducted 5 days/week and continued until asymptotic level of performance.

Fig. 8. PreFP training protocol and the R-Off pattern of behavior.

The Free Period occurs immediately before the presentation of the tone in the PreFP protocol. Animals using the R-Off strategy will begin bar-pressing upon the delivery of a reward, continue throughout the tone and stop at tone offset. PreFP trials had many possible patterns of behavior that result in three, two, one, or no rewards. Case 1 shows one possible response profile for a PreFP subject to obtain 3 rewards. A maximum of 2 rewards are possible during the tone and 1 reward during the free period. The first bar-press during the free period initiates the reward period (a). Only the first bar-press during the inter-trial-interval after the last reward is signaled as an error by a flashing light and time-out, i.e., extension of time until the next trial (e). All remaining bar-presses during the inter-trial-intervals are not signaled as errors. Case 2 also shows a scenario for 3 rewards. In this case, the first bar-press during the free period does not occur until later during the Free Period window (b). A tone immediately follows the free period reward as the trial continues. Notice that the first rewarded bar-press in this case (b) occurs at the time of the second rewarded bar-press in Case 1 (d). This demonstrates how the animal's response determines the time of tone presentation. Notice also that bar-presses (e) and (f) occur at the same latency after the start of the free period in Case 1 and Case 2 respectively, however these are signaled as an error or reward depending on the prior bar-pressing behavior during the trial. Case 3 shows a scenario in which 2 rewards were delivered, one during the tone and the second during the Free Period. Regardless of the latency and total number of bar-presses made during the tone, the first bar-press during the inter-trial interval is always signaled as an error. Case 3 also demonstrates the possibility of an “error loop” that occurs if bar-presses are made during an error-signaled time-out period (as in Case 5 in the PostFP protocol, Fig. 1B). These bar-presses reset the time-out period until bar-presses are withheld for the complete duration of at least one time-out period. Error loops only begin after the first inter-trial-interval bar-press because this is the only instance for which bar-presses result in error-signaled time-outs. Case 4 shows a scenario that only includes one rewarded response during the trial. A bar-press was made during the free period and rewarded to initiate a tone trial, but bar-presses did not occur during the tone. Again, the first bar-press after the tone is always signaled as an error, even without rewarded responses during the tone. Case 5 shows the only scenario in which a trial may occur without any rewards in the PreFP protocol. If bar-presses are absent once the free period begins, the inter-trial time will continue until a bar-press is made. The next bar-press will result in reward and initiate the tone trial. This scenario was extremely rare during training. All PreFP animals learned to obtain rewards by initiating trials. Asterisks indicate the bar-press at the beginning of the inter-trial interval period during which error signals were no longer delivered. Inter-trial interval bar-presses that followed the first bout of bar-pressing after the tone were not signaled as errors to ensure that subjects could initiate subsequent trials.

The PreFP protocol encouraged subjects' use of a learning strategy that depends on tone offsets, and not tone onset.

A strategy governed by ceasing to respond at tone offset naturally is evident when animals stop bar-pressing at tone offset, i.e., do not respond immediately thereafter and thus do not receive an error signal soon after tone offset. This behavior can be accomplished simply by rewarding bar-presses during signal tones and “punishing” bar-presses during silence, by error signals and time-out periods (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008). The Free Period was presented immediately preceding onset of the tone signal and precluded the use of the onset cue. However, here the Free Period was actually initiated by a bar-press during silence after an inter-trial interval and was followed immediately by a 10 s signal tone. Thus, PreFP subjects would be bar-pressing (or drinking water) during tone onset, so reward availability would not be signaled uniquely by tone onset, and hence they should rely on a strategy of bar-pressing from delivery of an initial reward (during silence) until tone offset. This strategy was called “Reward-to-Offset” (R-Off).

While this PreFP protocol promoted the desired learning strategy, it also constituted a particularly difficult problem for the subjects in this group. Essentially, they had to learn to inhibit bar-presses during a period of silence between tones in order to receive a trial and the opportunity to bar-press for reward. Moreover, they could not completely inhibit responding during silence because the presentation of the 10 s tone was contingent upon producing a bar-press during the Free Period that occurred during silence. Indeed, this period was distinguishable by the rat only by its presence after a longer, rather than shorter, period of silence.

Pilot studies revealed that rats would not maintain performance in this difficult task with very long silent inter-trial-intervals. Therefore, the intervals were 4–10 s on a random schedule. The first bar-press after tone offset was always signaled as an error with a time-out, as in Experiment 1. Bar-presses during this time-out period initiated another time-out period until bar-presses were withheld for the duration of at least one complete programmed time-out period. However, the PreFP group was not further penalized with time-outs for bar-presses made during inter-trial-intervals after receiving the initial error signal as pilot studies revealed it would enable better learning. Therefore, a bar-press during the inter-trial interval initiated a Free Period reward only after at least the duration of the scheduled inter-trial-interval. The proportion of bar-presses during the inter-trial interval that were actually penalized with time-outs during the course of training was 70.4 ± 17.5%.

Rats in the PreFP group could exhibit various patterns of behavior. While this protocol encouraged a pattern of one rewarded bar-press during the Free Period preceding onset of the tone, and two rewarded bar-presses during the tone, rats could receive three, two, one or no rewards dependent on their behavior in a given trial. Fig. 8 presents examples. Cases 1 and 2 yield three rewards. Cases 3, 4 and 5 yield two, one or no rewards, respectively. Adherence to a strict R-Off strategy on a trial is evident when a subject bar-presses during the pre-tone Free Period, and the subsequent signal tone, but not soon after tone offset, i.e., receives at least two rewards. Cases 2 and 3 meet this criterion.

3.1.4. Recording and analysis of behavior: performance and use of R-Off strategy

Performance level (P) in the PreFP group was calculated as in Experiment 1, except that the # error BPs = the total number of bar-presses resulting in a time-out period. The total number of bar-presses made during an inter-trial interval were not counted as error bar-presses because the PreFP protocol required subjects to make inter-trial interval bar-presses to initiate a trial. Thus, only bar-presses that were punished were included in the calculation of performance. Additional descriptions for measures of behavior are provided in Section 3.2.

3.1.5. Recording and analysis of behavior: frequency generalization

Frequency generalization gradients were constructed as in Experiment 1. The calculation for values in the PreFP group's generalization gradient is provided in Section 3.2.

3.1.6. Neurophysiological analyses

Complete mapping and analysis of A1 responses to sound was

performed as described in Experiment 1.

3.1.7. Statistics

Analyses were executed as for Experiment 1.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Behavior: the R-Off strategy

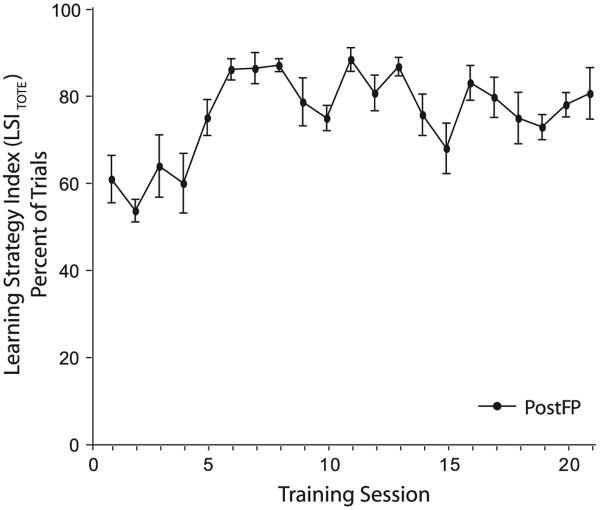

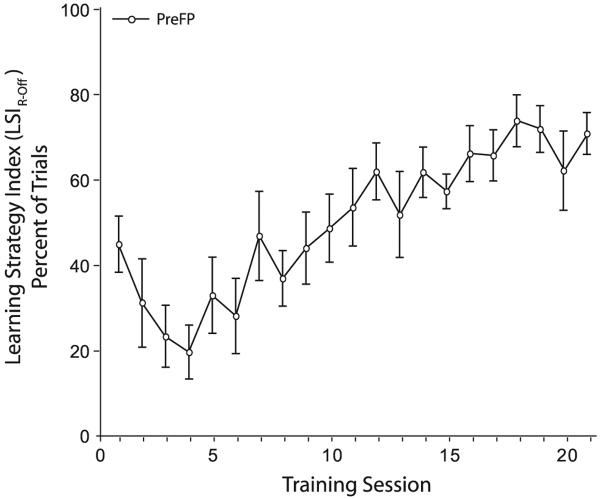

The PreFP group successfully acquired the task of bar-pressing during the signal tone for water reward (F(20,167) = 9.23; p < 0.0001). Subjects reached asymptotic levels of performance at 20.9 (±6.8) sessions. However, given the task difficulty, asymptotic performance attained only 39.5% (±4.2) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. PreFP group performance.

Performance (P = [# tone BPs/(# tone BPs + # error BPs)] 100%) increases across sessions until reaching an asymptote of 39.5% (±4.2 s.e.) over the last four training sessions.

The R-Off learning strategy involves bar-pressing for the first reward during silence with continued bar-presses for subsequent rewards during tone, until the tone offset. The use of tone offset to stop responding would be indicated by the cessation of bar-pressing at the termination of the tone. Increased use of the R-Off learning strategy would be indicated across sessions by a decrease in the number of post-tone-interval (PTI) bar-presses and an increase in PTI bar-press latency (i.e., as animals learn to withhold bar-presses after the tone).

Post-tone responses systematically decreased with training (F(20,167) = 10.94; p < 0.0001; Fig. 10A) and did so with a concurrent increase in the latency to the first bar-press after tone offset (F(20,167) = 11.11; p < 0.0001; Fig. 10B). Therefore, PreFP subjects adopted the use of tone offsets as required for the use of an R-Off strategy.

Fig. 10. Use of tone offsets revealed in the PreFP group's behavior.

(A) Responses during the post-tone-interval (PTI, 5 s) decrease across training sessions in the PreFP group. PTI is shown as the percent change relative to the first day of training. (B) Latency to bar-press after the tone offsets reveals their use to stop bar-pressing. The PreFP group's latency to respond after tone offset significantly increased with training.

But did the PreFP group actually solve the problem of obtaining water rewards using the R-Off strategy pattern of behavior? This response pattern consists of a bar-press during the pre-trial Free Period, at least one bar-press during the tone signal, and an absence of responses immediately after tone offset (i.e., pattern of responses shown in Fig. 8, Cases 2 and 3; Cases 1 is not “R-Off” because there is an error bar-press soon after tone offset). We calculated a LSI for each training session in the PreFP group to quantify the pattern of behavior that indicated use of the R-Off strategy as follows:

There was a systematic increase in LSI across training sessions (F(20,167) = 7.23; p < 0.0001) until the PreFP group reached asymptote on day 9 (60.1 ± 7.1%, Holm–Sidak post hoc: days 9–21 are not significantly different, p > 0.05). Therefore, PreFP subjects increased their use of the R-Off learning strategy with training (Fig. 11; Fig. S1B).

Fig. 11. PreFP learning strategy index (LSIR-Off) increases with training.

The proportion of trials with R-Off patterns of response increases until session 9 when the group is at an asymptote of 60.1% (±7.1 s.e.).

Frequency generalization gradients were constructed as for the PostFP group, except that the criterion for a response in the PreFP group was a trial on which at least two bar-presses occurred during the presentation of a tone. The rationale for this criterion was that PreFP subjects were already engaged in bar-pressing by the time of the presentation of the tone during training. Therefore, while learning, subjects did not hear the frequency of the tone until at least the second bar-press for reward. To better match the conditions of training with those of testing for frequency generalization, we assessed the frequency-specificity of behavior by defining responses as trials on which there occurred a second bar-press.

The PreFP group exhibited a generalization gradient peaked at the signal-frequency of 5.0 kHz, which failed to attain statistical significance (F(5,47) = 1.44, p > 0.05) (Fig. 12). However, there was no significant difference between the PreFP and PostFP group generalization gradients (F(5,89) = 0.78, p > 0.05).

Fig. 12. PreFP group's frequency generalization gradient.

The PreFP group learned about specific frequency. Subjects showed a peak in response at (5.0 kHz) or near (7.5 kHz) the signal-frequency (however the peak did not reach statistical significance) that was not different from the specificity of behavior in the other trained group.

3.2.2. Acoustic representation in A1: CF distribution across cortical area

Half-octave CF band analyses of cortical area within A1 compared to the naïve group showed that the PreFP group did not develop any gain representational area, either for the signal-frequency (t-test, 4.1–6.0 kHz CF band: t(14)=−0.18, p > 0.05), or any other frequency (Table 2). However, there was a significant decrease in area, limited to the half-octave band immediately above the tone signal-frequency (i.e., 6.1–8.0 kHz) from 7.24% (±1.30) in the naïve group to 0.67% (±0.33) of relative area in A1 (t-test, t(14)=−4.48, p < 0.001; all other bands, p > 0.05) (Table 2, Fig. 13).

Table 2.

The absence of signal-specific HARP in A1 area gain, and instead an area loss, in the PreFP group. Statistical tests for differences in A1 area relative to the naïve group are shown for each half-octave CF band.

| CF half-octave band |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1.5 | 1.6–2.0 | 2.1–3.0 | 3.1–4.0 | 4.1–6.0 (signal tone) | 6.1–8.0 | 8.1–12.0 | 12.1–16.0 | 16.1–24.0 | 24.1–32.0 | |

| PreFP % area (mean ± s.e.m.) | 2.49 (±1.90) | 5.58 (±2.42) | 6.55 (±1.05) | 5.67 (±1.58) | 4.94 (±1.43) | 0.67 (±0.33) | 7.00 (±1.10) | 19.29 (±2.83) | 7.88 (±1.62) | 7.68 (±2.42) |

| Naïve % area (mean ± s.e.m.) | 2.31 (±1.14) | 6.65 (±1.24) | 7.11 (±1.08) | 7.20 (±0.41) | 7.67 (±1.62) | 7.24 (±1.30) | 7.19 (±1.46) | 16.08 (±2.78) | 11.52 (±1.70) | 15.23 (±2.67) |

| Difference in % area (PreFP–Naïve) | +0.18 | −1.06 | −0.56 | −1.54 | −2.73 | −6.57* | −0.19 | +3.21 | −3.65 | −7.55 |

| t-Value: t(14) | 1.46 | 0.63 | −0.38 | −1.65 | −0.18 | −4.48 | 0.03 | 0.52 | −1.23 | 1.13 |

p < 0.001; all other tests are non-significant (p > 0.05).

Fig. 13. Representation of frequency across A1 in the PreFP group.

(A) Example map of characteristic frequency (CF) from a PreFP subject shows no change in signal-area relative to a naïve subject. Striped polygons show the area of representation of the signal-frequency within a half-octave band. (B) The amount of area for the signal-frequency was determined relative to the size of A1 (y-axis, % of total). CF distributions in half-octave bands do not reveal area gains in the signal- or any other signal-frequency band compared to the naïve group. Instead, the PreFP group showed a non-specific decrease from 7.24% (±1.30) in naïves to 0.67% (±0.33) in A1 area in the half-octave band immediately above that of the signal-frequency (asterisk). Light gray line shows the gain in area in the PostFP group for comparison between trained groups.

3.3. Discussion

The findings of Experiment 2 also provide support for the hypothesis that HARP in A1 depends on the degree to which tone onsets are used. The PreFP subjects relied on the use of tone offset (R-Off), not tone onset, and did not develop signal-specific area gains. Actually, use of the strategy that did not rely on tone onset resulted in a decrease in area a half-octave above the signal-frequency (6.1–8.0 kHz) (see also Section 4.2).

However, there are two alternative explanations for the absence of signal-specific area gain in the PreFP group: (a) inadequate use of the signal tone during learning or (b) instability of the R-Off strategy prior to electrophysiological recording.

If the lack of area gain reflected weak learning about the contingency between the tone signal and reward in general, then there should be a difference between the PreFP and PostFP groups in the tone's behavioral importance. The 10 test trials prior to stimulus generalization sessions were used to determine whether the PreFP and PostFP groups responded similarly to the signal. Because test trials did not include Free Periods, they provided a unique opportunity for group comparison because the trial parameters and response outcomes were identical between groups. Differences in bar-press patterns during these trials could only be explained by each group's prior history of using either the TOTE or R-Off strategy to obtain rewards. The mean number of bar-presses made during each signal test tone was not different between groups (t(13) = 1.01; p > 0.05). Therefore, the presence of the tone was sufficient to initiate bar-pressing behavior after learning using the TOTE (in the PostFP group) and R-Off (in the PreFP group) strategies (Fig. 14A). Because the responses to tones in identical trials were not significantly different between groups, a difference in the use of tones per se to bar-press for water reward cannot explain the absence of area gain in PreFP subjects.

Fig. 14. Comparison of PreFP group behavior with PostFP during test trials without Free Periods.

(A) The number of responses during tones on ten test trials without Free Periods was not different between groups. Therefore, PreFP subjects made use of the signal tone to the same degree as the PostFP group. (B) The PreFP group responded significantly less during the interval that followed the offset of tones (i.e., post-tone interval, PTI) than the PostFP group. These patterns of behavior could be predicted by the use of the R-Off or TOTE strategies and reflect the PreFP group's stability of R-Off strategy use prior to electrophysiological recording.

The second possibility is that if PreFP subjects failed to maintain the R-Off strategy during testing (i.e., 10 test trials as explained above) and did not use tone offsets to inhibit bar-presses, then responses during the 5 s period immediately after tone offsets (i.e., the post-tone-interval, PTI) should be similar to the PostFP group that used the TOTE-strategy and thus responded after tone offset. However, the PreFP group's response immediately after the tone's offset was twofold lower than the PostFP group (t(13) = 3.70; p < 0.01). This difference indicates that the PreFP group's use of tone offset cues to withhold bar-presses was maintained (Fig. 14B). Therefore, this group's use of the R-Off strategy remained intact immediately prior to neurophysiological recording.

4. General discussion

4.1. Synthesis of findings of Experiments 1 and 2

These experiments asked whether the extent to which HARP develops depends on the degree to which a learning strategy is employed. Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that HARP in A1 depends on the degree to which tone onsets (but not tone offsets) are employed to solve a problem. Experiment 1 revealed that increased use of the TOTE learning strategy that relies on tone onsets produced signal-specific gains in representational area. Experiment 2 showed that the use of a strategy that relies on the use of tone offsets and not tone onsets (the R-Off strategy) did not produce specific gains in area. A direct comparison of the differential distribution of bar-press responses with reference to the tone's onset and offset cues is provided in Figs. S1A and B. Only the adoption and use of the tone onset learning strategy (TOTE) reliably predicted the presence and degree of HARP after learning. In contrast, the use of the tone offset strategy (R-Off) failed to result in HARP that enhanced the representation of the signal-frequency.

Although area gains were absent after learning using the R-Off strategy, it is possible that plasticity had developed in A1 in a more local form than tuning shifts or gains in area, or was induced in a population of neural responses distinct from activity evoked by auditory onsets. To address the first possibility, we determined whether the groups could have developed changes that enhanced sensitivity (i.e., decreased threshold) and specificity (i.e., decreased bandwidth) of tuning in A1 (Berlau & Weinberger, 2008; Bieszczad & Weinberger, 2010b). Tuning sensitivity measured by threshold at CF did not decrease relative to the naïve group in either trained group for any frequency band (see Table S1A). Similarly, neither group differed in the specificity of tuning measured by bandwidth at 20 dB SPL across A1 (see Table S1B). Thus, the PostFP and PreFP groups did not develop enhancements in sensitivity or selectivity that were either concomitant with areal gains in the former, or instead of area gains in the latter group. Therefore, only PostFP animals using the TOTE learning strategy develop HARP in the form of a gain in cortical area for the signal-frequency which occur without evident decreases in threshold and bandwidth.

Thus, the second possibility, that plasticity developed elsewhere in the PreFP subjects using the R-Off strategy, is more likely. For example, while plasticity developed for onset responses in A1 after learning with a strategy that is tone onset-based, the use of another strategy that makes use of tone offset could induce plasticity in cells with responses to the offset of sounds. These changes could have occurred within A1 but been undetected in multiple unit recordings, or in another specialized region of auditory cortex that is particularly sensitive to acoustic offsets. Single unit studies of several auditory cortical fields are needed to resolve this issue (see Section 4.5).

Nevertheless, the findings indicate that learning strategy is critical for the induction of gains in frequency representation in A1. More specifically, the findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the degree of tone onset use or disuse dictates the form of HARP and the degree of representational area for the signal-frequency.

4.2. A continuum of tone onset dependent representational plasticity in A1

A direct comparison of the distributions of tonotopic area between groups in Experiments 1 and 2 (Figs. 3 and 13) shows that the frequency-specific cortical representation of acoustic signals depends on the degree to which tone onsets are important for learning. If tone onsets (but not tone offsets) are critical in an adopted learning strategy, then the representation of the signal-frequency is enhanced. If tone onsets are not critical, then the representation of the signal-frequency is not enhanced. Thus, there may be a continuum of frequency-specific representational plasticity in A1 that is tightly linked to a behavioral continuum of tone-onset strategy use, as explained below.

The findings of Experiment 1 demonstrate that signal representation can be in the form of gains in cortical area that are proportional to the degree to which animals made a strong use of the tone-onset strategy. In prior studies, representational enhancement took the form of signal-specific decreases in threshold and bandwidth, without changes in cortical area, after modest tone onset use. Yet, animals failed to develop any measurable change in signal representation when they made modest use of both onsets and offsets (i.e., a tone-duration or T-Dur strategy). Finally, the findings of Experiment 2 extend and may complete this continuum by demonstrating that A1 representational area is reduced when a strategy relies only on tone offsets and not tone onsets.

Recall that the observed loss in representational area was not at the signal-frequency, but confined to frequencies immediately above (Fig. 13B). This may be related to different frequency tuning of A1 onset and offset responses. Responses to the onsets and offsets of tones in the same cells have recently been shown to arise from distinct inputs. Moreover, onset and offset responses are tuned to frequencies separated by about a half-octave (Scholl, Gao, & Wehr, 2010). This differential representation of frequency in the same cells in A1 permits independent development of representational plasticity along the frequency dimension for both onset or offset responses. Thus, it is possible that the representational reduction seen for the “onset map” of frequencies immediately above the signal, occurred with a signal-specific representational enhancement for an offset response map following the use of an offset learning strategy. The extent to which the strategy-dependent continuum of HARP described here for tone onsets occurs in tandem with HARP for tone offsets remains to be explored.