Abstract

Using methyl(trifluoromethyl)dioxirane (TFDO), the oxidation of some tripeptide esters protected at the N-terminus with carbamate or amide groups could be achieved efficiently under mild conditions with no loss of configuration at the chiral centers. Expanding on preliminary investigations, it is found that, while peptides protected with amide groups (PG = Ac-, Tfa-, Piv-) undergo exclusive hydroxylation at the side chain, their analogues bearing a carbamate group (PG = Cbz-, Moc-, Boc-, TcBoc-) give competitive and/or concurrent hydroxylation at the terminal N-H moiety. Valuable nitro derivatives are also formed as a result of oxidative deprotection of the carbamate group with excess dioxirane. A rationale is proposed to explain the dependence of the selectivity upon the nature of the protecting group.

Introduction

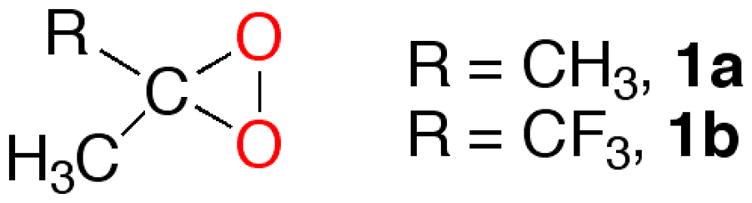

Over the past two decades, the dimethyldioxirane (DDO) (1a)1 and its trifluoro analog 1b (TFDO)2 (Scheme 1) have fruitfully been employed to accomplish the selective oxyfunctionalization of natural targets such as steroids, vitamine D3 derivatives, and terpenes.3 Among the many useful dioxirane oxidations, a transformation that counts among the highlights is the oxygenation of simple, “unactivated” C—H bonds; high tertiary vs. secondary selectivities (Rst from 15 to over 250) can be routinely achieved.2,3a,4

SCHEME 1.

Common Dioxiranes in the Isolated Form

Some N-protected derivatives of α-amino esters5 and peptides6 have also been examined; in this case also, it was shown that dioxiranes offer advantages over classical oxidation methods, affording the selective oxyfunctionalization of tethered alkyl side chains. High regioselectivity for O-insertion into the γ-CH bond of leucine (Leu) residues with respect to the weaker α-CH bonds was observed with no appreciable loss of configuration at the chiral centers.5,6

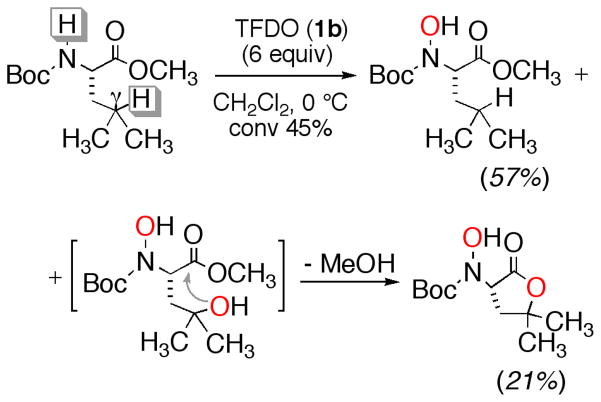

Interestingly, we reported that using the powerful TFDO (1b) in the oxidation of Boc protected amino esters Boc-L-Val-OCH3 and Boc-L-Leu-OCH3 — concurrent with the oxyfunctionalization at the side chain — the hydroxylation of the protected NH moiety takes place; removal of the Boc protecting group with TFA affords the corresponding N-hydroxyamino methyl esters in high yield. An example is shown in Scheme 2.5 Using the less powerful DDO (1a) instead of 1b, these oxidations are rather sluggish, requiring long reaction times to afford just the hydroxylation at the side chain in low yield.6b

SCHEME 2.

Oxidation of Boc-L-Leu-OMe with TFDO (1b)

Subsequent extension of these studies to the TFDO oxidation of Boc-protected di- and tripeptide esters bearing alkyl side chains showed that hydroxylation of the terminal N—H can be achieved efficiently, with no appreciable loss of configuration at the chiral centers.6a We also found that, while N-Boc peptides undergo oxyfunctionalization at the terminal N—H preferentially, the corresponding N-acetyl (Ac) peptides experience exclusive hydroxylation at the side-chain (CH3)2C—H.5,6a The chemoselectivity observed appeared puzzling, so that we decided to expand our investigations aiming to shed light into this peculiar effect of the protecting group (PG).

Results and Discussion

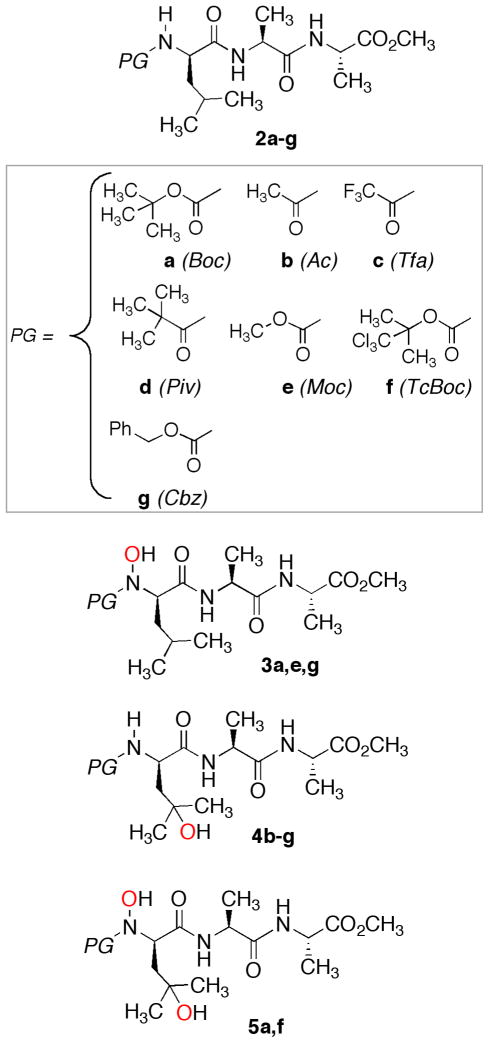

We began upon examining the oxidation of the model tripeptide methyl ester D-Leu-L-Ala-LAla-OCH3 (2) (Chart 1) in order to gain insight into the effect of changing the PG from Boc-(2a) and Ac- (2b) to Tfa (trifluoroacetyl)- (2c) and Piv (pivaloyl)- (2d) on product distribution. The results are shown in Table 1; the reactions were carried out under the mild conditions reported therein.

CHART 1.

TABLE 1.

Oxidation of Boc-, Ac-, Tfa-, Piv- derivatives 2a–d with TFDO (1b)a

| Entry | Substrate | PG | Ox/Subb | Product | Yield (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2a | Boc | 2.4 |

3a 5a |

47 28 |

| 2 | 2b | Ac | 4 | 4b | 62 |

| 3 | 2c | Tfa | 5 | 4c | 66 |

| 4 | 2d | Piv | 4 | 4d | 68 |

All reactions were routinely run in acetone at 0 °C, reaction time 4–6 h, substrate conv. 80–97% (based on the amount of recovered starting material).

Molar ratio of dioxirane oxidant to substrate.

Isolated yield, based on the amount of starting material reacted.

The oxidation procedure merely involved the addition of an aliquot of standard dioxirane solution (0.5–1.0 M)2 to an acetone solution of the tripeptide on a 75–100 mg scale

Reaction mixtures were separated by preparative TLC (silica gel, eluent Et2O/hexane/acetone) and products identified by 1H and 13C NMR, as well as by HRMS. For instance, significant were the mass spectra of monohydroxylation products 3 and 4; with respect to the parent ion peak (M) of starting materials 2a–g, these showed a mass increase of m/z +16 consistent with the incorporation of a single oxygen atom, whereas the bis hydroxylation derivatives 5 displayed a mass increase at m/z +32.

The actual site of oxidation could be established by NMR spectroscopy. In particular, significant was the absence of a NH resonance in the 1H NMR spectra of products 3 and 5; in the proton spectra of 4 and 5, the two methyl resonance doublets present for substrates 2 were replaced by two lower-field singlets, as a result of O-insertion into the (CH3)2C-H bond. With respect to the starting material, in the {1H}13C NMR spectra of 3 and 5 quite telling was a lower-field shift of the resonance pertaining to carbon adjacent to the PG-N(OH)- group, and the appearance of a resonance at ca. 70.5 ppm (C-OH) for products 4 and 5.

Results in Table 1 show that just the carbamate Boc- protecting group allows hydroxylation at the terminal NH, yielding mainly 3a (PG = Boc). The latter is accompanied by the consecutive overoxidation product 5a, in lower yield. Instead, the other PGs examined yield side-chain oxidation products only (4b–d), in spite of the varying electronic and steric effects. This change in selectivity prompted us to examine the TFDO oxidation of a few substrates presenting a carbamate PG other than Boc, i.e. 2e–g as well as 77 and 98 (Chart 2). The results are collected in Table 2. Similar to Boc-protected 2a (Table 1), it is seen that oxidation of its TcBoc (2,2,2-trichloro-tert-butyloxycarbonyl) counterpart (entry 2, Table 2) gives rise to N—H hydroxylation product 5f besides side-chain O-insertion (4f) under the given conditions. For sake of simplicity, among the several results in our hands, we have chosen to report in Table 1 and Table 2 just those oxidant/substrate ratios that produce the best isolated yields of the given products, with sizeable substrate conversion during a reasonable reaction time.

CHART 2.

TABLE 2.

Oxidation of Substrates having the Terminal NH Functionality Protected with Carbamate Groups with TFDO (1b)a

| Entry | Substrate | Ox/Subb | PG | Products | Yield (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2e | 2.4 | Moc |

3ed 4e 6 |

28e 26 13 |

| 2 | 2f | 5 | TcBoc |

4f 5ff |

57 21e |

| 3 | 2g | 5 | Cbz |

3gd 4g 6g |

15e 44 24 |

| 4 | 7 | 6 | Cbz | 8g | 60 |

| 5 | 9 | 5 | Cbz |

10g 11 |

20 40 |

All reactions were routinely run in acetone at 0 °C, reaction time 2–4 h, substrate conv. 65–80 % (based on the amount of recovered starting material)

Molar ratio of dioxirane oxidant to substrate.

Isolated yield, based on the amount of starting material reacted.

Obtained in mixture with the unreacted starting material.

As estimated by integration of the 1H NMR signals relative to the leucine α–CH’s of the compounds in the mixture.

Obtained in mixture with 4f.

The formation of the nitro derivatives 6, 8, and 10 is accompanied by the production of benzoic acid in equimolar amount.

The oxidation of Moc (methyloxycarbonyl) derivative 2e and Cbz derivative 2g also displays terminal N-H hydroxylation along with O-insertion at the side-chain (CH3)2C-H (3e,g and 4e,g), but now the valuable nitro derivative 6 is also formed (entry 1 and 3).

Furthermore, the terminal nitro compound 8 largely prevails as the major product in the oxidation of α-CH3 branched peptide derivative 7 (entry 4).9 Similarly, for the oxidation of Cbz-protected α-amino ester 9 (entry 5) we observed that formation of 1110 (the 4-butanolide derived from preliminary side-chain hydroxylation; cf. Scheme 2)5,6 is accompanied by the production of nitro derivative 1011 in some 20% yield.

For the transformations above, it seems safe to assume that the terminal nitro functionality would result from oxidative deprotection of the carbamate group. It might be envisaged that — preceded or followed by hydroxylation at the terminal N—H — this takes place along with dioxirane oxidation at the “activated” benzylic C—H bond (a process which is well documented),12 release of PhCO2H and facile decarboxylation of the resulting, labile carbamic acid intermediate HO2C-N(OH)-.

In agreement with this view, we observe that the conversion of 9 into nitro derivative 10, as well as that of substrate 2g into 6, are both accompanied by the production of benzoic acid in equimolar amounts.

Clearly, a key step here consists of the final oxidative conversion of the freed hydroxyamino moiety into a nitro group. This step could mimic in part the sequence envisaged for the dioxirane oxidation of amines with excess dioxirane, i.e. RNH2 → RNH-OH → RN=O → RNO2.13 Hence in the controlled reaction of amino sugars with stoichiometric DDO (1a) at −40 °C, the oxidation of the -NH2 moieties could be tuned to stop at the hydroxylamine stage.14 The oxidation of secondary amines to hydroxylamines is readily achieved with a single dioxirane equivalent.13c It is known that amides resist oxidation by dioxiranes, although the corresponding amines are readily oxidized. Actually, this transformation is often employed to protect amines.3b

In view of the above findings, a few words are in order concerning the still unsettled mechanistic dilemma concerning how the N-hydroxylations actually take place.3 We consider it is unlikely that, at odds with what established for the oxygenation of unactivated C—H bonds,3 this could occur by direct dioxirane O-insertion into the N—H moiety. Rather, it might result from previous electrophilic oxidation at the lone pair on nitrogen, followed by the rapid conversion of the N-oxide intermediate into a hydroxylamino derivative, i.e. R(H)(H)N: → R(H)(H)N+—O− → R(H)N—OH.

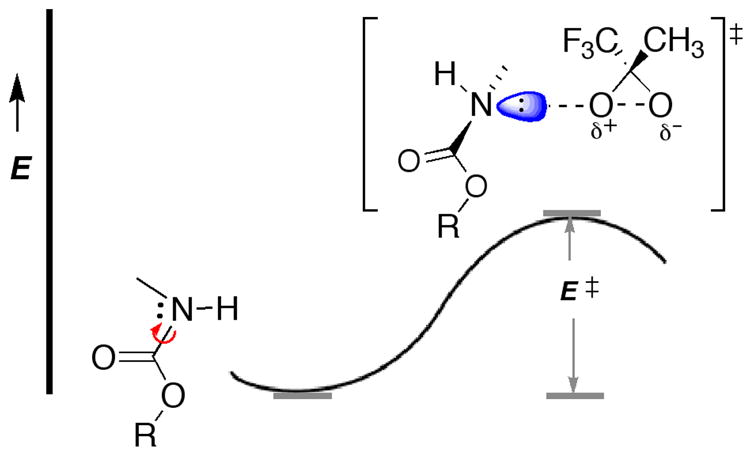

If this is the case, for the transformation at hand it remains unclear why only carbamate protected peptide esters display N-H hydroxylation, while those presenting the amide PG do not. An answer might be found considering first that, with respect to the amine moiety in the amide group the availability of the nitrogen lone pair for dioxirane electrophilic attack is widely diminished because of delocalization into the carbonyl over the π system. Thus, in an amide group–NH-C(:O)-, for an approximately planar three-atom framework the rotational barrier to twist the C—N linkage is increased by more than 10 kcal/mol as compared to ordinary amines.15a

Second, one might recall that several investigations15 have shown that the barrier to rotation about partial C—N double bonds in amides and carbamates (urethanes) varies markedly. Actually, in a carbamate group -O-C(:O)-NH-, two resonances (nN→π*C-O and nO→π*C-O) compete to each other for the delocalization onto the same π*C-O orbital, thus lowering the activation energy to rotation about partial C—N double bonds (Figure 1) by ca. 2–4 kcal mol−1 with respect to comparable amides (E≠ = 12.4 to 14.3 kcal mol−1).15 Thus, as sketched in Figure 1, dioxirane attack should be facilitated.

FIGURE 1.

Energy Barrier to a TS Featuring a Quasi Pyramidal Nitrogen Lone-pair Receiving Dioxirane Electrophilic Attack

Consistent with this view is our finding that, when an effective electron-withdrawing group (R) is present in the carbamate PG, the diminished electron density on oxygen hinders the competition with the nitrogen for conjugation to the carbonyl, so that the rotational barrier to the transition state increases;15 as a result, the process of N-oxidation becomes less favorable. This seems to be the case for the TcBoc- substrate 2f. In this instance, the presence of the electron-withdrawing group (R = Cl3C-(CH3)2C-) significantly reduces the amount of the N-hydroxylation product 5f with respect to that of side-chain oxidation 4f (entry 2, Table 2).

It is apparent that further careful work is in order to put our intriguing mechanistic hypothesis to test. In any case, in view of the limited electron density at nitrogen of the -O–C(:O)-NH- moieties, it is perhaps not surprising that a potent oxidant such as TFDO should be needed for N-hydroxylation.

Conclusions

Be the mechanistic details as they may, results herein suggest that the powerful dioxirane TFDO (1b) should be the oxidant of choice for the synthesis of unnatural peptides or amino acids presenting selective oxidative modifications at the protected N-H element and/or at the side-chain C-H moiety, as those of the D-Leu N-terminal residue in the substrates examined. This finding is valuable if one recalls that the products usually are ammonia (or ammonium salts) and nitrogen-free residues when amino acids or peptides are directly oxidized using common oxidants.11 Then, our method should bring a major flexibility in the design of novel bioactive peptide analogues. In particular, the efficient production of N—OH derivatives 3a, 3e, 3g, and 5 is notable because the synthesis of N-hydroxypeptides represents a challenging goal; in fact, these are key intermediates in metabolic pathways and can be found in human and animal tumors.16

In addition, the TFDO oxidations that yield the terminal nitro derivatives 6, 8, and 10 represent no small feat. Indeed, the family of such nitro compounds stand for the starting point for several useful synthetic applications.17 It is also remarkable that, presumably because of a nonradical oxidation mechanism, the reactions reported herein occur with complete retention of configuration. This stereochemical outcome is observed with all products reported, with the obvious exception of 6 and 10, in which case the chirality at the proximal α-CH was not retained due to the considerable acidity of the hydrogen adjacent to the nitro group.11

Experimental Section

Starting materials

Boc-tripeptide 2a was obtained following coupling procedures in solution and then used for the synthesis of substrates 2b–g upon deprotection (TFA or dry HCl/MeOH)18 and re-protection of the free terminal amino group as appropriate. Tripeptide 7 was synthesized according to a reported method;7 Cbz-Leu-OCH3 (9) was obtained starting with the corresponding commercial acid upon reaction with CH3I.19 These substrates presented purity > 95% (HPLC and/or 1H NMR).

N-tert-butyloxycarbonyl-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (2a): m.p.: 78–80 °C; [α]D = −32.4 (c 0.96, CH3OH); HRMS-ESI (M+H+): calcd for C18H34N3O6+ 388.2448, found 388.2396. N-acetyl-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (2b): m.p.: 188–189 °C; [α]D = −34.8 (c 0.93, CH3OH); HRMS-ESI (M+H+): calcd for C15H28N3O5+ 330.2029, found 330.2023. N-trifluoroacetyl-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (2c): m.p.: 172–173 °C; [α]D = −32.6 (c 1.07, CH3OH); HRMS-ESI (M+H+): calcd for C15H25F3N3O5+ 384.1746, found 384.1846. N-trimethylacetyl-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (2d): m.p.: 110–113 °C; [α]D = −37.7 (c 0.96, CH3OH); HRMS-ESI (M+H+): calcd for C18H34N3O5+ 372.2498, found 372.2531. N-methyloxycarbonyl-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (2e): m.p.: 160–162 °C; [α]D = −18.3 (c 0.7, CH3OH); HRMS-ESI (M+Na): calcd for C15H27N3NaO6+ 368.1798, found 368.1787. N-(2,2,2-trichloro-tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (2f): m.p.: 81–83 °C; [α]D = −23.6 (c 3.4, CH3OH); HRMS-ESI (M+Na+): calcd for C18H30Cl3N3NaO6+ 512.1098, found 512.1095. N-benzyloxycarbonyl-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (2g): m.p.: 157–158 °C; [α]D = −27 (c 1.33, CH3OH); HRMS-FAB (M+Na+): calcd for C21H31N3NaO6+ 444.2111, found 444.2120. N-benzyloxy-carbonyl-α-methyl-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (7):7 m.p.: 101–102 °C; [α]D = −38.1 (c 0.5, CH3OH)]. N-benzyloxycarbonyl-L-leucine methyl ester (9):8 oil; [α]D = −29 (c 1.8, CH3OH) [lit.:8 −28 (c 2.1, CH3OH)]; physical constants and spectral data in agreement with literature.8

The following procedure is representative of the TFDO oxidations of substrates 2a–g, 7, and 9: Oxidation of N-tert-butyloxycarbonyl-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (2a) with 1b. Solutions of 0.8–1.0 M methyl(trifluoromethyl)dioxirane (1b) were made available adopting procedures, equipment, and precautions already reported in detail.2 To a stirred solution of 2a (76.5 mg, 0.197 mmol) in acetone (2 mL) at 0 °C, a standardized cold solution of TFDO (1b) in 1,1,1-trifluoropropanone (TFP) (0.55 M, 0.85 mL, 0.473 mmol) was added in one portion.20 The reaction progress was monitored by TLC (silica gel, Et2O/n-hexane 3:1) and by following the dioxirane decay (iodometry).2 Upon reaction completion (ca. 4 h), the solvent was removed in vacuo and the reaction mixture separated by preparative TLC (silica gel, Et2O/n-hexane 3:1); besides unreacted starting material (2.3 mg, 5.94 μmol, conv. 97%), pure products 3a (36.4 mg, 0.090 mmol) and 5a (22.3 mg, 0.053 mmol) could be isolated respectively in 47% and 28% yield (based on the amount of starting material reacted).

N-tert-butyloxycarbonyl-N-hydroxy-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (3a): m.p. 78–80 °C; [α]D = −24.8 (c 2.5, CH3OH); 1HRMS-FAB (M+Na+): calcd for C18H33N3NaO7+ 426.2216, found 426.2391.

N-tert-butyloxycarbonyl-N, γ-dihydroxy-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (5a): m.p. 52–54 °C; [α]D = −23.1 (c 2.0, CH3OH); HRMS-FAB (M+Na+): calcd for C18H33N3NaO8+ 442.2165, found 442.2156.

N-acetyl-γ-hydroxy-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (4b): m.p. 141–143 °C; [α]D = − 17.6 (c 1.1, CH3OH); HRMS-FAB (M+Na+): calcd for C15H27N3NaO6+ 368.1798, found 368.1792.

N-trifluoroacetyl-γ-hydroxy-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (4c): m.p. 142–143 °C; [α]D = −34.6 (c 1.8, CH3OH); HRMS-FAB (M+Na+): calcd for C15H24F3N3NaO6+ 422.1515, found 422.1525.

N-trimethylacetyl-γ-hydroxy-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (4d): m.p. 152–154 °C; [α]D = −56.3 (c 1.2, CH3OH); HRMS-FAB (M+Na+): calcd for C18H33N3NaO6+ 410.2267, found 410.2260.

N-methyloxycarbonyl-N-hydroxy-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (3e): [obtained in mixture (ca. 1:2, by 1H NMR) with starting material 2e]; HRMS-ESI (M+Na+): calcd for C15H27N3NaO7+ 384.1747, found 384.1727.

N-methyloxycarbonyl-γ-hydroxy-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (4e): m.p. 153–156 °C; [α]D = −19.1 (c 0.4, CH3OH); HRMS-ESI (M+H+): calcd for C15H28N3O7+ 362.1927, found 362.1910.

N-(2,2,2-trichloro-tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-γ-hydroxy-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (4f): m.p. 67–69 °C; [α]D = −20.3 (c 0.5, CH3OH); HRMS-ESI (M+Na+): calcd for C18H30Cl3N3NaO7+ 528.1047, found 528.1027.

N-(2,2,2-trichloro-tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-N, γ-dihydroxy-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (5f) [obtained in mixture (ca. 1:1, by 1H NMR) with product 4f]; HRMS-ESI (M+Na+): calcd for C18H30Cl3N3NaO8+ 544.0996, found 544.1224.

N-benzyloxycarbonyl-N-hydroxy-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (3g) [obtained in mixture (ca. 1:1, by 1H NMR) with starting material 2g]; HRMS-ESI (M+H+): calcd for C21H32N3O7+ 438.2240, found 438.2337.

N-benzyloxycarbonyl-γ-hydroxy-D-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (4g): m.p. 133–136°C; [α]D = −17.0 (c 0.8, CH3OH); HRMS-FAB (M+Na+): calcd for C21H31N3NaO7+ 460.2060, found 460.2074.

N-(4-methyl-2-nitropentanoyl)-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (6) [obtained as a 1:1 mixture (1H NMR) of 2R- and 2S- diastereoisomers]; HRMS-FAB (M+Na+): calcd for C13H23N3NaO6+ 340.1485, found 340.1470.

N-[(S)-2,4-dimethyl-2-nitropentanoyl]-L-alanyl-L-alanine methyl ester (8): m.p. 78–81 °C; [α]D = −17.6 (c 0.75, CH3OH); HRMS-FAB (M+Na+): calcd for C14H25N3NaO6+ 354.1641, found 354.1648.

Methyl 4-methyl-2-nitropentanoate (10)10 (oil) and (S)-2-(benzyloxycarbonylamino)-4,4-dimethyl-4-butanolide (11)9 [m.p. 91–92 °C [lit.:9 94 °C], [α]D = −4.0 (c 3.0, CHCl3)] gave spectral data in agreement with literature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the Ministry of Education of Italy (MIUR, grant PRIN 2008), to the National Research Council (CNR, Rome, Italy), the NIH (GM-35982), and the NSF (CHE-0718275) for financial support. One of us (C. A.) is grateful to Brown University for generous hospitality during a period spent at the Chemistry Department as Visiting Scientist. Thanks are due to Dr. R. Mello (University of Valencia, Spain) and to Dr. Tun-Li Shen (Brown University) for performing some of the HRMS analyses.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. General experimental details, supplemental 1H and 13C NMR characterization data of oxidation products and of new starting materials, and sample HPLC runs. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Murray RW, Jeyaraman R. J Org Chem. 1985;50:2847. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cassidei L, Fiorentino M, Mello R, Sciacovelli O, Curci R. J Org Chem. 1987;52:699. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mello R, Fiorentino M, Sciacovelli O, Curci R. J Org Chem. 1988;53:3890. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For recent dioxirane reviews, see: Curci R, D’Accolti L, Fusco C. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:1. doi: 10.1021/ar050163y.Bach RD. In: The Chemistry of Peroxides. Patai S, editor. Vol. 2. Wiley; New York: 2006. Chapter 1.Adam W, Zhao C-G, Kavitha J. Org React. Vol. 69. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2007. pp. 1–346.. See also references therein.

- 4.Mello R, Fiorentino M, Fusco C, Curci R. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:6749. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Detomaso A, Curci R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:755. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Rella MR, Williard PG. J Org Chem. 2007;72:525. doi: 10.1021/jo061910n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Saladino R, Mezzetti M, Mincione E, Torrini I, Paglialunga Paradisi M, Mastropietro G. J Org Chem. 1999;64:8468. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toniolo C, Pantano M, Formaggio F, Crisma M, Bonora GM, Aubry A, Bayeul D, Dautant A, Boesten WHJ, Schoemaker HE, Kamphuis J. Int J Biol Macromol. 1994;16:7. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett AGM, Pilipauskas D. J Org Chem. 1990;55:5170. [Google Scholar]

- 9.It is worth of note that the analogous peptide 2g, lacking a Me group at the C α to the terminal N—H, affords mainly side-chain hydroxylation. The varying selectivity might be due to subtle changes in the preferred conformation adopted by peptide 7 in undergoing dioxirane attack, owing to limited flexibility resulting from branching at the α-carbon. ( Toniolo C, Crisma M, Formaggio F, Peggion C. Biopolymers (Pept Sci) 2001;60:396. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:6<396::AID-BIP10184>3.0.CO;2-7.See references therein)

- 10.Altman J, Moshberg R, Ben-Ishai D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;16:3737. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Rozen S, Bar-Haim A, Mishani E. J Org Chem. 1994;59:1208. [Google Scholar]; (b) Laloo D, Mahanti MK. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans 2. 1990:311. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rawalay SS, Shechter H. J Org Chem. 1967;32:3129. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Murray RW, Jeyaraman R, Mohan L. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:2470. doi: 10.1021/ja00269a069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mello R, Cassidei L, Fiorentino M, Fusco C, Curci R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:3067. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kuck D, Schuster A. Z Naturforsch. 1991;46B:1223. [Google Scholar]; (d) Marples BA, Muxworthy JP, Baggaley KH. Synlett. 1992:646. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray RW, Jeyaraman R, Mohan L. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:2335.Murray RW, Rajadhyaksha SN, Mohan L. J Org Chem. 1989;54:5783.Crandall JK, Reix T. J Org Chem. 1992;57:6759.Synthesis of nitro-substituted cyclopropanes and spiropentanes via oxidation of the corresponding amino derivatives: Volkova YA, Ivanova OA, Budynina EM, Revunov EV, Averina EB. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:2793.

- 14.Wittman MD, Halcomb RL, Danishefsky SS. J Org Chem. 1990;55:1981. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Pontes RM, Basso EA, dos Santos FP. J Org Chem. 2007;72:1901. doi: 10.1021/jo061934u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Modarresi-Alam AR, Najafi P, Rostamizadeh M, Keykha H, Bijanzadeh HR, Kleinpeter E. J Org Chem. 2007;72:2208. doi: 10.1021/jo061301f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yamagami C, Takao N, Takeuchi Y. Aust J Chem. 1986;39:457. See references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Yanagisawa A, Takeshita S, Izumi Y, Yoshida K. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5328. doi: 10.1021/ja910588w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Merino P, Tejero T. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:2995. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301760. See references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Eyer M, Seebach D. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:3601. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ram S, Ehrenkaufer RE. Synthesis. 1986:133. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gogte VN, Natu AA, Pore VS. Synth Commun. 1987;17:1421. [Google Scholar]

- 18.For instance, see: Shendage DM, Froehlich R, Haufe G. Org Lett. 2004;6:3675. doi: 10.1021/ol048771l.

- 19.Garner P, Park JM. Org Synt. 1992;70:18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.As for solvents in alternative to acetone, the choice is limited to solvents which resist oxidation by the powerful dioxirane oxidant. In practice, options are confined to using chlorinated solvents (CH2Cl2, CHCl3, CCl4), as well as MeCN.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.