Abstract

Gastroblastoma is a rare gastric epitheliomesenchymal biphasic tumour composed of spindle and epithelial cells, reported by Miettinen et al in a series of three cases in 2009. All those cases arose in stomachs of young adults. Neither the epithelial nor the mesenchymal component displayed sufficient atypia to diagnose a carcinosarcoma or other malignancy. On immunohistochemistry, the epithelial component expressed cytokeratin, and the mesenchymal component was positive for vimentin and CD10. Miettinen et al designated these neoplasms as gastroblastomas based on their similarities with other childhood blastomas such as pleuropulmonary blastoma and nephroblastoma. This report describes a probable fourth case of this unique type of neoplasm. The present case arose in the gastric antrum of a 9-year-old boy. While similarities were evident with the other cases, there were some differences. The epithelial component was more predominant and showed more mature morphology. Immunohistochemically, the epithelial component showed immunolabelling for c-KIT and CD56. The mesenchymal component was only focally positive for CD10. Ultrastructually, desmosomes and microvilli were found supporting a truly epithelial lesion.

Keywords: Gastric, neoplasms, paediatric pathology

Introduction

Gastroblastoma is a recently identified novel stomach epitheliomesenchymal biphasic tumour composed of uniform spindle and epithelial cells, reported by Miettinen et al in a series of three cases.1 Herein, we report a probable fourth case arising in the distal antrum of the stomach in a 9-year-old boy. While similarities were evident with the other cases, some morphological and imunohistochemical differences were found. Additionally, we assessed KIT mutations and examined the ultrastructural features.

Materials and methods

Section staining and immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with H&E, periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), and periodic acid–Schiff diastase (D-PAS). Immunohistochemistry was performed on sections (5 mm thick) sections prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue using the Dako Envision system (Dako, Carpinteria, California, USA) as described by the manufacturer. Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry are listed in table 1. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was used for all antibodies in appropriate buffers.

Table 1.

Used antibodies and their results

| Antibody | Clone | Source* | Result | |

| Epithelial cell | Spindle cell | |||

| Pancytokeratin | AE1/AE3 | Biogenex | + | − |

| Vimentin | V2 | Zymed | − | + |

| CD56 | 1B6 | Novocastra | + | Weak + |

| c-KIT | Polyclonal | Dako | + | − |

| LMWCK | 35βH11 | Dako | + | − |

| HMWCK | 34βE12 | Dako | − | − |

| EMA | E29 | Dako | + | − |

| Synaptophysin, | SP11 | LabVision | − | − |

| Chromogranin | SP12 | LabVision | − | − |

| NSE | 5ES | Novocastra | − | − |

| SMA | 1A4 | Dako | − | − |

| Desmin | D33 | Dako | − | − |

| CD10 | 56C6 | Novocastra | − | Weak focal + |

| CD34 | QBEnd-10 | Dako | − | − |

| p63 | 4A4 | Dako | − | − |

| CEA | ll-7 | Dako | − | − |

| Calretinin | 5A5 | Novocastra | − | − |

| Inhibin | R1 | Oxford Bio Innovate | − | − |

+, Positive; −, negative.

Biogenex, San Ramon, California, USA; LabVision, Fremont, California, USA; Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; Oxford Bio Innovate, Bicester, UK; Zymed, San Francisco, California, USA.

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; EMA, epithelial membrane antigen; HMWCK, high molecular weight cytokeratin; LMWCK, low molecular weight cytokeratin; NSE, neuron-specific enolase; SMA, smooth muscle antigen.

Electron microscopy

Material taken from fresh tumour was prepared for electron microscopic examination. Briefly, it was pre-fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (4°C, phosphate buffer, pH 7.2) and was post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer. The material was dehydrated with a series of graded ethyl alcohols, and embedded in epoxy resin. Thick sections (1 μm) were stained with 1% toluidine blue for light microscopy. Thin sections (50–60 nm) were prepared using a Reichert-Jung SuperNova ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and were double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Thin sections were examined with a JEM-1200EX II transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

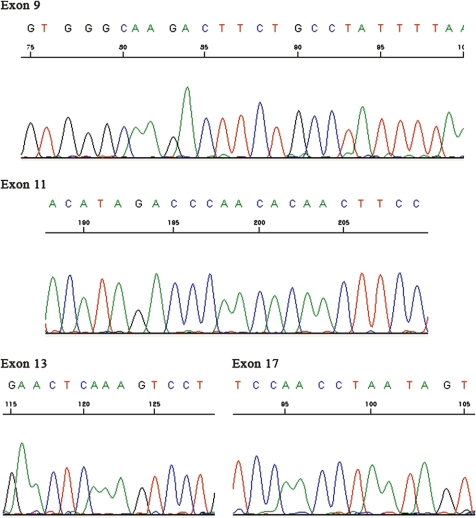

Mutational analysis

Mutational analysis of the c-KIT gene was performed as previously described.2 Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded tumour tissue. PCR assays amplified fragments containing the entire c-KIT sequence of exons 9, 11, 13 and 17. PCR products were sequenced directly using the Big Dye Terminator kit (PE Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) and analysed on an ABI Prism 310 capillary automated sequencer (PE Biosystems).

Results

Clinical findings

A 9-year-old boy presented to Pusan National University Yang-san Hospital with a 3-month history of abdominal pain and a tender palpable periumbilical mass. CT revealed a solid and cystic 8.0 cm gastric antral mass that compressed the adjacent duodenum, gallbladder and pancreas (figure 1). An explorative laparotomy was performed. At operation, the mass arose from the gastric antrum and protruded towards the liver. A resection of the tumour and a segmental resection of gastric antrum and pylorus were performed separately.

Figure 1.

CT showing a solid and cystic mass arising in the gastric antrum.

Pathological findings

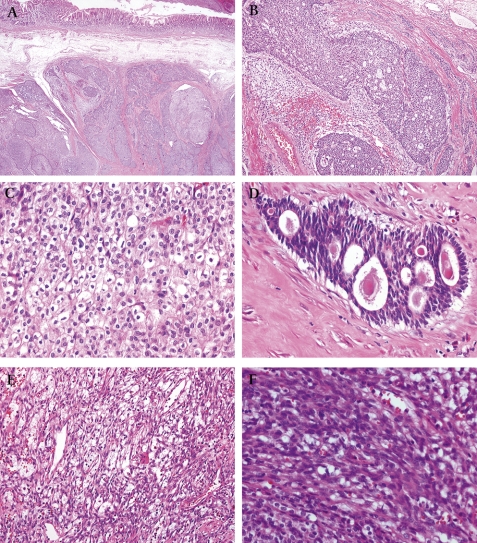

Grossly, the mass was solid and cystic measuring 9.0×6.5 cm. The cut surface showed a grey flesh-like appearance with a haemorrhagic cystic portion (figure 2). Grossly, the resected antrum showed a solid submucosal tumour. The mucosa was intact. On microscopic examination, the tumour was centred in the muscularis propria of the gastric antrum (figure 3A). The tumour was biphasic in composition, with epithelial and mesenchymal cells evident. The epithelial component, which comprised the majority of the tumour, was arranged mainly in the sheets, nests, cords and tubules (figure 3B). An invasive growth pattern of this component was evident at scanning magnification. The epithelial cells forming the sheets and nests had round uniform nuclei, slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm, and inconspicuous nucleoli. In some cells, the nucleus was condensed and the cytoplasm was clear with a distinct cell border, resembling glycogenated squamous cells (figure 3C). These cells, however, were negative using PAS and D-PAS stains. The epithelial cells frequently formed glands or rosette-like structures containing luminal eosinophilic secretory material (figure 3D). The nuclei in these glandular structures were dark and elongated. The mesenchymal-type cells, which were arranged in short fascicles or in a reticular pattern in loose stroma (figure 3E), occupied a smaller portion compared with the epithelial component. The cells had bland oval to short spindle-shaped nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli and scant cytoplasm (figure 3F). Mitoses were absent in both components. The tumours displayed rare calcifications.

Figure 2.

The cut surface of tumour was variegated with a grey flesh-like solid portion and a haemorrhagic cystic portion.

Figure 3.

Microscopic findings of tumour. (A) Scanning view shows the tumour centred in muscularis propria and extending towards the submucosa (×20). (B) Epithelial components were arranged in sheets, cords and tubules (×100). (C) Epithelial cells displayed clear cytoplasm and distinct cell borders. Nuclei were round to convoluted or condensed (×400). (D) Tubular or rosette-like differentiation was apparent. In some lumina, eosinophilc material was present (×400). (E) Mesenchymal cells were arranged in a reticular or short fascicular pattern (×100). (F) Mesenchymal cells were spindle to ovoid shaped, without obvious atypia (×400).

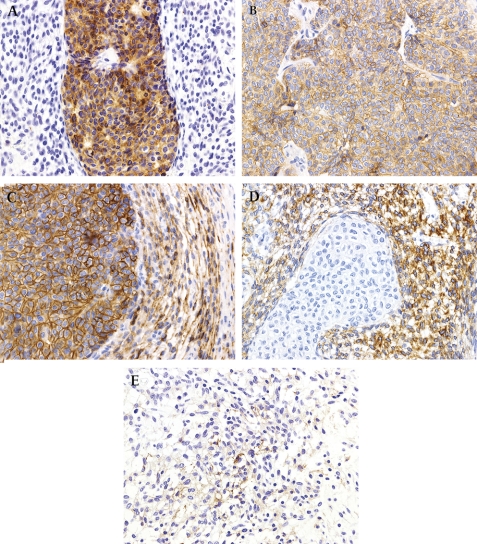

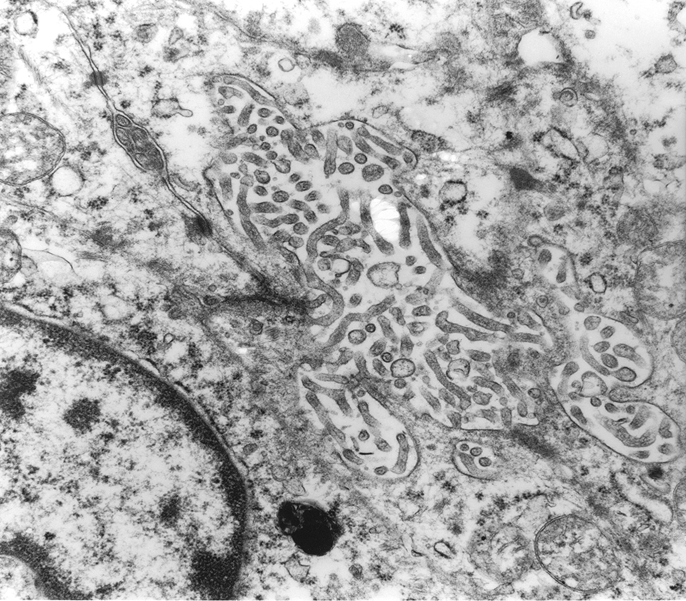

Immunohistochemically, the overtly epithelial component expressed pancytokeratin (figure 4A), low molecular weight cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen, c-KIT (figure 4B), and CD56 (figure 4C). The spindle cell component was positive for vimentin (figure 4D) and focally weakly positive for CD10 (figure 4E) and CD56. Additional details concerning the antibodies used and results obtained are presented in table 1. On electron microscopic examination, tumour cells were observed to be attached by desmosomes, and microvilli were present (figure 5). c-KIT mutational analysis of exons 9, 11, 13 and 17 showed no abnormality (figure 6).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry findings. (A) Pancytokeratin selectively highlighted the epithelial component (×400). (B) Epithelial components were immunoreactive for c-KIT (×400). (C) CD56 was strongly positive in the epithelial component and focally weakly positive in the mesenchymal component (×400). (D) The mesenchymal component was strongly positive for vimentin (×400). (E) CD10 was focally weakly positive in mesenchymal cells (×400).

Figure 5.

Electron microscopy revealed desomosomes and microvilli (×8000).

Figure 6.

Mutation analysis of the c-KIT gene did not detect mutations in exons 9, 11, 13 and 17.

Discussion

To date, three cases of a novel, distinctive, biphasic epitheliomesenchymal tumour designated as gastroblasmoma have been presented.1 In these cases, the mesenchymal component consisted of spindle to ovoid cells without structural differentiation and significant nuclear atypia. The epithelial component occupied a smaller portion than the mesenchymal component. In two of the three cases, the epithelial component consisted of condensed clusters of epithelioid cells that blended with mesenchymal cells. In the remaining case, the epithelial component formed luminal structures with inspissated eosinophilic secretions. Neither the epithelial nor mesenchymal components displayed sufficient atypia to identify the neoplasms as carcinosarcoma or other malignancy. On immunohistochemistry, the epithelial components were positive for keratins and mesenchymal components were positive for vimentin and CD10. The authors designated these neoplasms as gastroblastoma due to the similarities with other childhood blastomas such as pleuropulmonary blastoma and nephroblastoma.1

The present case is very similar clinically and morphologically to the other three reported cases. Clinically, the present case arose in the distal gastric antrum of a child. Morphologically, the mass was centred on the muscularis propria and protruded towards the subserosa. It was composed of biphasic epitheliomesenchymal components. The mesenchymal components were spindle to ovoid cells without a specific pattern, mitotic activity or atypical cytological features. An epithelial component showing glandular differentiation with primitive cells was present.

However, the present case exhibited several distinctive features. The epithelial component was dominant over the mesenchymal component, in contrast to being focal. The morphology of the epithelial component was more mature and distinct, in contrast to the blending of the epithelial components with spindle cells to form a condensed cluster. The epithelial component was arranged mainly as broad sheets. The cells were focally squamoid with clear cytoplasm and distinct cell borders, and the nuclei were focally convoluted and condensed accompanied by clear cytoplasm, mimicking glycogenated squamous cells. PAS and D-PAS were negative in those cells. In addition, the demarcation between the epithelial and mesenchymal components was sharply defined. Electron microscopy revealed desmosomes and microvilli, indicative of true epithelial differentiation. Finally, the epithelial component of the present case displayed a strong and diffuse positive immunohistochemical reaction for c-KIT and CD56, while the mesenchymal component was only focally positive for CD10. Because c-KIT and CD56 are expressed in so many human tumours, their expression would seem to be non-specific. No c-KIT mutation was detected in exons 9, 11, 13 and 17.

Despite the aforementioned morphological and immunohistochemical differences, we believe that the present case is another example of gastroblastoma. Blastomas in other organs, including pleuropulmonary blastoma,3 4 hepatoblastoma,5 nephroblastoma6 and neuroblastoma,7 have variable proportions of their components and varying degrees of cellular differentiation. The morphological spectrum of gastroblastomas may be broad, with classification based on epithelial and mesenchymal cell proportions and the degree of differentiation. In the present case, the epithelial component displayed a definite invasive growth pattern, suggesting that gastroblastoma has a low risk of malignant potential, as pointed out by the authors of the original report.1 The differential diagnosis of biphasic tumours in the gastrointestinal tract revolves around sarcomatoid carcinomas (‘carcinosarcomas’), synovial sarcoma and teratoma. Carcinosarcoma would be overtly malignant-appearing and unlikely in a child, and synovial sarcoma would be unlikely to display such prominent epithelial differentiation; indeed Miettinen et al found no evidence of SYT/SSX gene rearrangements in the cases reported as gastroblastoma.1 Teratomas would display more specific differentiation towards non-neoplastic structures. In assessing this case, we also initially considered a peculiar endocrine neoplasm, but we were unable to demonstrate either chromogranin or synaptophysin expression in the epithelial zones.

We suspect that so-called gastroblastoma may be more akin to such unusual neoplasms as spindle epithelial tumour with thymus-like differentiation/SETTLE8 and ‘desmoplastic nested spindle cell tumour of liver’9 10 than to classic ‘blastic’ tumours, in that SETTLE and desmoplastic nested spindle cell tumour of liver are generally indolent neoplasms; the prognosis for the three cases reported as gastroblastoma has been excellent following treatment. Although the follow-up period has been short for the patient presented here, he remains well with no recurrence 9 months after surgery.

Take-home messages.

The present case is probably an example of a newly recognised epitheliomesenchymal tumour (gastroblastoma).

Compared with that in the previously reported three cases, the epithelial component was more mature.

Ultrastructually, desomsomes and microvilli were found, supporting true epithelial differentiation.

This entity seems to be an indolent neoplasm.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Miettinen M, Dow N, Lasota J, et al. A distinctive novel epitheliomesenchymal biphasic tumor of the stomach in young adults (‘gastroblastoma’): a series of 3 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1370–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim KM, Kang DW, Moon WS, et al. PKCtheta expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Mod Pathol 2006;19:1480–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill DA, Jarzembowski JA, Priest JR, et al. Type I pleuropulmonary blastoma: pathology and biology study of 51 cases from the international pleuropulmonary blastoma registry. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:282–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priest JR, McDermott MB, Bhatia S, et al. Pleuropulmonary blastoma: a clinicopathologic study of 50 cases. Cancer 1997;80:147–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correa H. Hepatoblastoma. Pathology Case Reviews 2009;14:21–7 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy W, Grignon D, Perlman E. Kidney tumors in children. AFIP Atlas of tumor pathology: tumors of the kidney, bladder and related urinary structures. Washington DC: American Registry of Pathology, 2004:10–38 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimada H, Ambros IM, Dehner LP, et al. The International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification (the Shimada system). Cancer 1999;86:364–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folpe AL, Lloyd RV, Bacchi CE, et al. Spindle epithelial tumor with thymus-like differentiation: A morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1179–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill DA, Swanson PE, Anderson K, et al. Desmoplastic nested spindle cell tumor of liver: Report of four cases of a proposed new entity. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makhlouf HR, Abdul-Al HM, Wang G, et al. Calcifying nested stromal-epithelial tumors of the liver: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 9 cases with a long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:976–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]