Abstract

Purpose

While many effective treatments exist for osteoporosis, most people do not adhere to such treatments long-term. No proven interventions exist to improve osteoporosis medication adherence. We report here on the design and initial enrollment in an innovative randomized controlled trial aimed at improving adherence to osteoporosis treatments.

Methods

The trial represents a collaboration between academic researchers and a state-run pharmacy benefits program for low-income older adults. Beneficiaries beginning treatment with a medication for osteoporosis are targeted for recruitment. We randomize consenting individuals to receive 12-months of mailed education (control arm) or an intervention consisting of one-on-one telephone-based counseling and the mailed education. Motivational Interviewing forms the basis for the counseling program which is delivered by seven trained and supervised health counselors over ten telephone calls. The counseling sessions include scripted dialogue, open-ended questions about medication adherence and its barriers, as well as structured questions. The primary endpoint of the trial is medication adherence measured over the 12-month intervention period. Secondary endpoints include fractures, nursing home admissions, health care resource utilization, and mortality.

Results

During the first 7 months of recruitment, we have screened 3,638 potentially eligible subjects. After an initial mailing, 1,115 (30.6%) opted out of telephone recruitment and 1,019 (28.0%) could not be successfully contacted. Of the remaining, 879 (24.2%) consented to participate and were randomized. Women comprise over 90% of all groups, mean ages range from 77–80 years old, and the majority in all groups was white. The distribution of osteoporosis medications was comparable across groups and the median number of different prescription drugs used in the prior year was 8–10.

Conclusions

We have developed a novel intervention for improving osteoporosis medication adherence. The intervention is currently being tested in a large scale randomized controlled trial. If successful, the intervention may represent a useful model for improving adherence to other chronic treatments.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, Medication Adherence, Randomized Controlled Trial, Education

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis affects 50% of women 65 and older and 30% of men.1 Fractures cause substantial pain and disability with 30% of persons unable to live at home after a hip fracture.2 Spine and hip fractures are not only associated with morbidity but mortality – 35% of people die within a year of a hip fracture and 8% die within a year of a spine fracture.3 In 2008, osteoporosis will cost Americans approximately $18 billion in direct medical expenditures.4

Many fractures related to osteoporosis can be prevented through primary and secondary prevention. A variety of drugs have been proven to reduce the risk of second fractures, and several of these medicines also reduce first fractures among people with reduced bone mineral density.5 However, medication non-adherence likely impedes realizing the full benefit of osteoporosis treatment. The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research considers adherence as a synonym for compliance, defined as the proportion of days with medication available; a second aspect of long-term medication use is persistence (length of time using medication).6 We will use the term adherence throughout this manuscript to refer to the proportion of days with medication available, and as a general term referring to both aspects of long-term medication use. Multiple large observational studies from countries with different health systems find low rates of long-term adherence.7 One year after initiation of a medication for osteoporosis approximately 50% of people continue to use any osteoporosis medication.8 Non-compliance appears to be associated with a significant increase in the risk of fracture, such that people who take 50% of their dosages have a 40% increase in their risk of fractures compared with those who take over 90%.9

People report a wide variety of reasons for non-compliance with osteoporosis medication, including real or perceived medication side effects, treatment costs, depression, forgetfulness, and a lack of understanding regarding the chronic nature of osteoporosis.10, 11 These reasons duplicate factors associated with non-adherence to other similarly asymptomatic conditions, such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia. A variety of interventions have been attempted to improve adherence with osteoporosis medications.12–16 These interventions typically include a patient-directed counseling approach, with or without feedback to the patient about the level of bone turnover markers, and educational material. In several of these trials, the counseling has been conducted by nurses specializing in osteoporosis. However, there has been a relative lack of attention to behavioral models underlying the counseling programs, the specific training of the counselors, or to the frequency of the counseling.

Several successful adherence trials in other medical areas have based interventions on Motivational Interviewing. Motivational Interviewing was developed by Miller and Rollnick and is built upon Prochaska’s transtheoretical model of behavior change.17, 18 The transtheoretical model of behavioral change posits that individuals move through a series of stages in the process of changing behavior and direct interventions based on individual’s readiness for change. Using this framework, motivational interviewing incorporates an active listening model of counseling, emphasizing relationship building with patients in order to facilitate patients’ evaluation of their health risks and treatment options to develop strategies for managing their health condition. Motivational Interviewing has been widely used in substance abuse programs.19, 20 More recently, it has been incorporated into several successful medication adherence interventions targeting anti-retroviral therapy for HIV as well as treatment for hypertension.21, 22

We undertook the Osteoporosis Telephonic Intervention to Improve Medication Adherence (OPTIMA) Trial to test whether a Motivational Interviewing counseling model would enhance adherence with medications for osteoporosis. Several novel aspects of the trial motivate this description of the study design, including the use of Motivational Interviewing, the collaboration with a public prescription benefit program for subject recruitment, and the use of routinely collected utilization data as trial endpoints.

METHODS

Study Design

The OPTIMA Trial is a 12-month randomized blinded controlled trial. The investigators assessing and analyzing the outcomes are blinded to the treatment assignment. The subjects in both arms, intervention and control, receive mailed educational materials. Subjects in the intervention arm also receive telephone counseling using a Motivational Interviewing approach. Because subjects in both arms receive enhanced care and do not know whether they are in the group receiving the more intensive regimen, subjects and investigators are blinded to treatment assignment. In this respect, the trial is double-blind. Randomization of subjects occurs centrally using a random number generator and is stratified by gender, allowing recruitment of similar numbers of men and women in both treatment arms.

Study Population and Recruitment Procedure

All subjects are Medicare enrollees and participate in Pennsylvania’s Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for the Elderly (PACE), managed by the Pennsylvania Department of Aging. Persons who meet the annual income criteria and who are 65 years or older, receive prescription medications after paying a modest co-payment ($6–15 per drug per month). On a monthly basis, PACE identifies potentially eligible subjects who filled a new prescription to treat osteoporosis, including alendronate, calcitonin, ibandronate, raloxifene, risedronate, teriparatide, and zoledronic acid. A new prescription is defined as the cardholder’s first claim for an osteoporosis medication within the past 12 months. In addition, eligible subjects must be enrolled in PACE for at least 12 months, reside in a non-institutional setting, and not have a designated power of attorney.

Potentially eligible subjects receive an invitation letter giving them the opportunity to opt-out of any further contact by returning a letter or calling a toll-free telephone number. If no opt-out is received within two weeks, we attempt telephone contact for recruitment on at least three separate occasions at different times of the day. Potentially eligible subjects successfully reached by telephone are explained the goals of the study and asked to participate. Some potentially eligible subjects cannot be successfully contacted by telephone after three attempts or cannot communicate by telephone (severe hard of hearing or non-English speakers). After consent is received by telephone, subjects are assigned into treatment arm “A” or “B” (intervention or control) based on a randomization schedule generated by a random number program. Only the study coordinator is aware of intervention and control assignment. All study investigators and biostatisticians remain blind to treatment assignment.

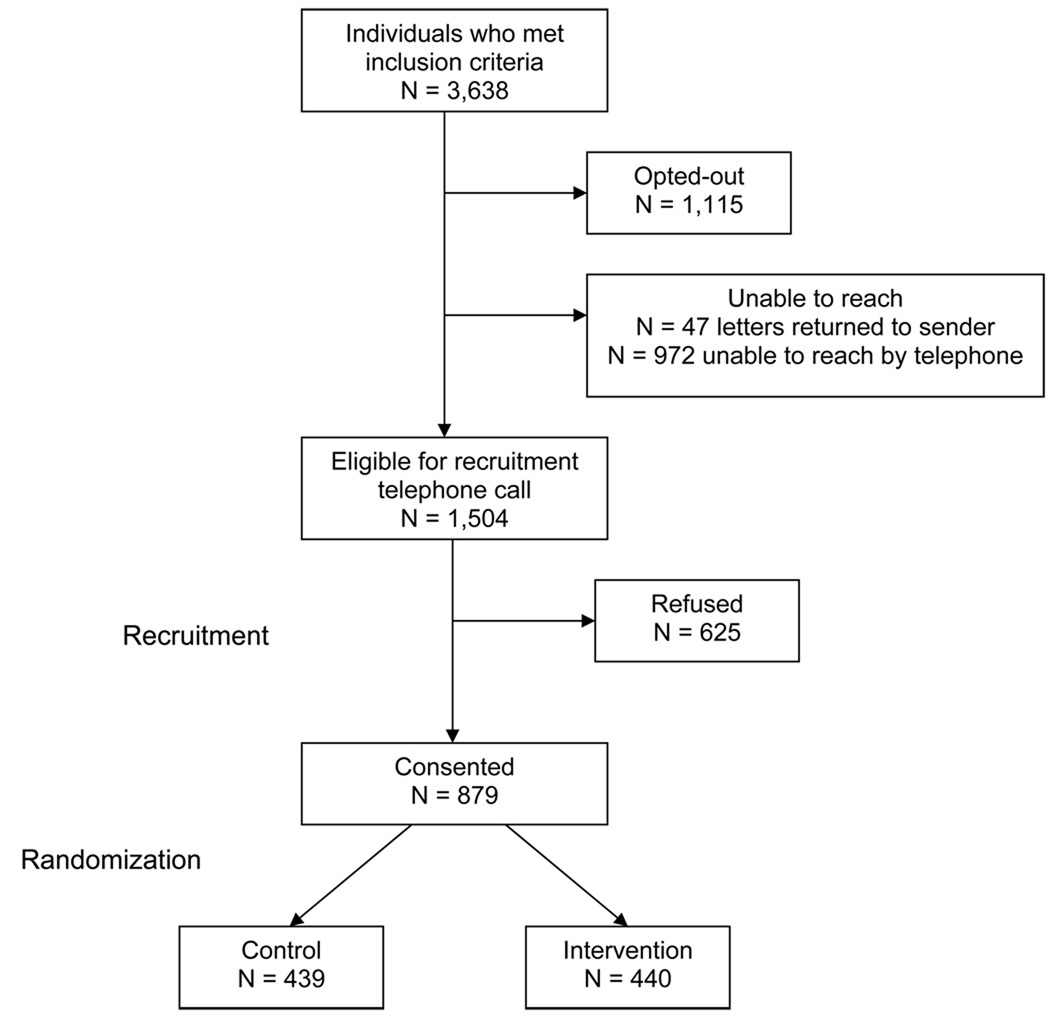

Potentially eligible subjects sort into four categories: opt-out by letter or telephone call; unable to reach by mail or telephone; refuse participation; and consent to participate in the trial. We illustrate assembly of our study population (see Figure 1) and compare basic demographic and pharmacy data from these four categories for the initial seven months of recruitment (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cohort Assembly

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of All Potentially Eligible Subjects During the First Seven Months of the OPTIMA Trial

| Opt-Out N = 1115 |

Unable to reach* N = 1019 |

Refuse N = 625 |

Consent N = 879 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 79.6 (6.6) | 79.4 (7.1) | 80.0 (6.7) | 77.1 (6.4) |

| Female gender, n (%) | 1039 (93.2%) | 935 (91.8%) | 591 (94.6%) | 821 (93.4%) |

| Race | ||||

| White, n (%) | 1051 (94.3%) | 854 (83.8%) | 564 (90.2%) | 781 (88.9%) |

| Black, n (%) | 21 (1.9%) | 89 (8.7%) | 38 (6.1%) | 57 (6.5%) |

| Other, n (%) | 7 (0.6%) | 27 (2.7%) | 5 (0.8%) | 10 (1.1%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 36 (3.2%) | 49 (4.8%) | 18 (2.9%) | 31 (3.5%) |

| Osteoporosis medication, n (%) | ||||

| Bisphosphonate, daily | 7 (0.6%) | 10 (1.0%) | 5 (0.8%) | 6 (0.7%) |

| Bisphosphonate, weekly | 729 (65.4%) | 659 (64.7%) | 403 (64.5%) | 587 (66.8%) |

| Bisphosphonate, monthly | 225 (20.2%) | 175 (17.2%) | 119 (19.0%) | 161 (18.3%) |

| Bisphosphonate, IV | 5 (0.5%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Calcitonin | 96 (8.6%) | 130 (12.8%) | 52 (8.3%) | 59 (6.7%) |

| Raloxifene | 44 (4.0%) | 32 (3.1%) | 34 (5.4%) | 47 (5.4%) |

| Teriparatide | 9 (0.8%) | 12 (1.2%) | 12 (1.9%) | 18 (2.1%) |

| Number of prescription drugs, median (IQR) |

Q1 = 5 Median = 8 Q3 = 12 |

Q1 = 6 Median = 10 Q3 = 14 |

Q1 = 5 Median = 9 Q3 = 13 |

Q1 = 5 Median = 9 Q3 = 14 |

Unable to reach included: 575 subjects with only a voice mail, busy signal, telephone hang-up, or no answer to the recruitment telephone call; 190 with disconnected telephone number; 154 only able to reach a friend or family of the potentially eligible subject; 47 subjects with returned recruitment letter because of change of address; 21 non-English speaking; 19 with invalid telephone numbers; and 13 deceased.

During the first 7 months of recruitment, we have screened 3,638 potentially eligible subjects. After an initial mailing, 1,115 (30.6%) opted out of telephone recruitment and 1,019 (28.0%) could not be successfully contacted. Of the remaining, 879 (24.2%) consented to participate and were randomized while 625 (17.2%) refused participation. Characteristics of all potentially eligible subjects are described in Table 1. Women comprise over 90% of all groups, mean ages range from 77–80 years old, and the majority in all groups was white. The distribution of osteoporosis medications was comparable across groups and the median number of different prescription drugs used in the prior year was 8–10.

The entire study protocol was reviewed by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt based on the fact that the trial aimed to improve quality for beneficiaries of a federally-funded health care program (Medicare) and was performed in conjunction with a state-run pharmacy program (PACE).

Intervention

Subjects in both the intervention and control arms receive mailed education specially designed for this trial (see Supplementary File). The educational material comprises seven topics: basic information about osteoporosis and fractures; the appropriate use of osteoporosis medications; how to talk with your doctor about medications; fall prevention through home safety; sufficient calcium and vitamin D through diet and supplements; exercises to improve balance; and bone mineral density testing. These educational materials are written at a sixth-grade reading level, use 14-point font, are limited to less than two pages; and incorporate color graphics to make them attractive. All subjects in the intervention and control arms receive materials on one topic at a time every four to eight weeks. The schedule of topics mailed to the intervention arm is timed to coincide with the educational topics discussed by the counselors (see below).

In addition to this mailed material, subjects randomized to the intervention arm also receive one-on-one counseling by telephone. Four of the seven counselors are certified health educators and the others are health professionals with experience in patient counseling. The counselors have received 6–8 hours of education about osteoporosis and then periodic updates of new information. They are supported by a clinician (DHS) and are instructed to refrain from giving medical advice. They are instructed to answer informational questions about osteoporosis and medications. However, they are instructed to refer questions about treatment decisions back to the subject’s prescribing physician. In addition, they participated in workshops on Motivational Interviewing. The initial Motivational Interviewing workshop was a half-day interactive session with an experienced trainer. Counselors also participate in biweekly conference calls with the investigative team to discuss issues related to the use of Motivational Interviewing and questions arising from the subjects. In addition, Motivational Interviewing supervision is provided to the counselors every six months through the review of audiotaped subject telephone calls in a one-on-one discussion with a supervisor experienced in Motivational Interviewing.

During the 12-month trial, counselors are scheduled to make ten calls to subjects in the intervention arm. The first call aims to explain the counseling program, to build rapport with subjects, and to answer client questions. The remaining nine calls occur at set intervals and have specific themes noted in Table 3. Each call entails discussion of medication adherence -- exploring barriers to adherence, offering suggestions for overcoming barriers, and answering specific questions that subjects pose. Suggested scripts for each telephone call are supplied through a web-based counseling tool developed specifically for the trial.

Table 3.

List of Primary, Secondary and Exploratory Outcomes and Planned Analyses

| Description (analysis) | |

|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |

| Osteoporosis medication possession ratio at 12 months | Percentage of total days with osteoporosis medication available (linear regression) |

| Secondary outcomes | |

| Osteoporosis medication possession ratio at 18 and 24 months | See above |

| Osteoporosis medication persistence at 12, 18, and 24 months | Months until first 90 day gap without available osteoporosis medication available (survival analysis) |

| Fractures at 12 months | Fracture rate (Cox proportional hazard regression) |

| Exploratory outcomes | |

| Nursing home admissions at 12 months | Nursing home admission rate (Cox proportional hazard regression); number of days in nursing home (linear regression) |

| Health care resource utilization at 12 months | Cost of direct care (linear regression) |

| Survival at 12 months | Mortality rate (Cox proportional hazard regression) |

For example, the counselor may be prompted to say, “would you mind telling me a bit about how you take your osteoporosis medication?” or “could you please share with me your experiences when taking your osteoporosis medication?” The counselor may also incorporate a simple reflection strategy which includes restating what the subjects reported such as, “when you take your Fosamax (alendronate), you sometimes feel sick to your stomach.” Another strategy used is reflection of meaning. Using this approach the counselor integrates the perspective of the subject into their refection. For example, “your osteoporosis makes you anxious about falling and having a hip fracture.” These comments are made in an open-ended manner allowing the subject to elaborate and problem-solve without instruction from the counselor. In addition, these strategies help maintain a client-focused approach to discussions and illuminate the subject’s underlying beliefs and concerns which may affect adherence.

Endpoints

The primary outcome for this trial is medication adherence at twelve months, the end of the study period (see Table 3). Medication compliance will be measured as the medication possession ratio (MPR), calculated as the percentage of days in which the subject has an osteoporosis medication available for use during the follow-up period. Thus, the denominator will be the number of days of follow-up during the 12 month study period with 365 days being the maximum. Follow-up begins with the first successful telephone call and is censored at the first of any of the following events: loss of PACE eligibility; transfer to a nursing home; or death. For the first 100 days of a nursing home admission, patients’ medications are reimbursed by Medicare, not PACE. Since Medicare drug files are not available in a timely fashion, these data cannot be used for endpoint assessment and thus, follow-up is censored at nursing home admission.

The numerator in the MPR calculation is the number of days with available osteoporosis medication. Available medication is defined as the number of days of the medication dispensed by the subject’s pharmacy. When people fill a prescription, pharmacies submit a claim containing the name and dosage of the medication, the date dispensed, and the number of days supplied. As part of our collaboration with PACE on this intervention, we have access to pharmacy dispensing information for all enrollees. Thus, we are able to calculate the days with available osteoporosis medication from the day supply field. Since zoledronic acid is an annual medication, the MPR will be 100% by definition.

The secondary outcomes to be examined are listed in Table 3. Since a key question is the durability of the twelve-month intervention, we will assess the MPR at 18 and 24 months after enrollment. In addition to compliance, we are interested in persistence to therapy, with persistence defined as the time until a prolonged period without treatment. A prolonged period without treatment is defined as at least 90 days without available medication. Persistence will be assessed at 12, 18, and 24 months of follow-up. These definitions are consistent with current recommendations.(Cramer)

The most relevant clinical outcome for this medication adherence trial is fracture. We will assess fracture rates at the hip, wrist, humerus, pelvis, clavicle, tibia, ribs and spine. These will be assessed using health care utilization data from Medicare. However, because Medicare health care claims data require a 12–18 month lag period in their availability, we will also obtain self-report for these fractures at the study conclusion. Self-report of fractures has been found to be valid.23, 24

Secondary outcomes include nursing home admissions at 12 months, overall health care utilization at 12 months, and survival at 12 months. Each of these outcomes may relate to osteoporosis medication adherence and the telephone counseling. Since the relationship of these outcomes with the intervention is less direct, we consider these exploratory. Nursing home admissions will be considered as a dichotomous variable as well as cumulative days in nursing. Nursing home admission information will be extracted from Medicare utilization data. Overall health care resource use will include acute care hospitalizations, nursing home stays, rehabilitation stays, physician and emergency department visits, all medication dispensings, laboratory, and radiology use. Finally, mortality will be assessed from social security files.

Statistical Analyses and Power Considerations

The primary analysis will use an intention to treat (ITT) design. Thus, all subjects will be analyzed according to their randomization group, regardless of whether they participate fully in the intervention. A secondary analysis will include information about a subject’s level of participation in the intervention, represented by the number of telephone counseling sessions in which the subject participated. Because small imbalances in subject characteristics may obscure the effect of the intervention, we will include important baseline variables as covariates in a linear regression model to calculate the primary outcome. The linear regression will include the continuous MPR as the dependent variable with treatment assignment as the variable of interest. The baseline covariates will include age, gender, osteoporosis treatment, frequency of treatment (daily, weekly, monthly), and race.

We have calculated the required sample size for this trial based on the following assumptions. First, we estimate that an absolute improvement of 10% in osteoporosis medication MPR was likely the smallest clinically relevant difference.9 Second, we assumed that the control group would have an MPR of 50%. This is slightly higher than prior analyses suggest, but we anticipate that enrolled subjects may be more motivated than a typical population.7 Based on these assumptions, we will require 1050 subjects in each arm to have at least a 90% power to rule out a two-sided Type I error of 5%. This number of subjects provides less than 80% power to detect a 15% relative reduction in fractures in the intervention arm compared with the control arm (9% of 1050 = 95 versus 10.5% of 1050 = 110).

In addition to the primary outcomes, we are conducting a cost-effectiveness analysis side-by-side with the trial. This analysis aims to examine the economic implications of the intervention and its effect on adherence and fractures. Thus, we are collecting information about the cost of the intervention and the economic implications of different levels of adherence. As well, through a survey of a subset of subjects, we are collecting information about quality of life and the non-medical costs of osteoporosis.

DISCUSSION

Osteoporosis is common and treatable but effective care is greatly hindered by poor medication adherence. While medications with less frequent dosing intervals and intravenous administration may reduce non-adherence, there is a great need to develop more effective strategies for improving medication adherence across many relatively asymptomatic chronic conditions. Medication non-adherence is multifactorial and the determinants vary from person to person. Thus, effective interventions will need to help people overcome their own barriers (real and perceived) to adherence. Motivational Interviewing counseling programs have been found effective for improving adherence with HIV treatments and anti-hypertensive regimens, but have not yet been tested in osteoporosis.

The OPTIMA Trial is testing a twelve-month one-on-one telephonic counseling program for osteoporosis medication adherence against a mailed education program. The design and conduct of the trial are unique in several respects. First, the counseling program is based on a Motivational Interviewing approach, which has been used previously, but never telephonically.21, 22 Prior successful medication adherence interventions based on Motivational Interviewing primarily used face-to-face counseling, which may be more difficult to deploy in large older adult populations. No prior osteoporosis medication adherence interventions have employed Motivational Interviewing in a randomized controlled trial. Second, the eligible subjects are being recruited from a publicly-funded pharmaceutical benefits program for Medicare beneficiaries. This collaboration allows us to consider how such an intervention might work within Medicare at large. Third, the effects of this intervention are being evaluated using routinely collected pharmacy dispensing claims. This allows for more accurate and less resource-intensive adherence calculations than self-reported measures. Finally, since both the control and intervention arms receive enhanced care (mailed education), the subjects are blinded to their treatment assignment. Blinding subjects in adherence trials is uncommon.

At least several prior controlled trials of adherence interventions have been conducted for osteoporosis.12–16 Of the counseling-based interventions, several have been successful but others not. One non-randomized trial that used a historical control group was based on Motivational Interviewing.15 While the methodology of this trial was weak because of the use of non-concurrent controls, the results suggested that Motivational Interviewing could produce large benefits. Several of the unsuccessful counseling-based interventions had relatively infrequent contact (2–3 sessions over one year) and the counseling method was not well described. None of the prior controlled trials in osteoporosis have been adequately powered to detect differences in clinical outcomes.

The OPTIMA trial focuses on one chronic disease, osteoporosis. If this intervention is successful, it would be worth considering a similar approach for other chronic conditions (such as hyperlipidemia or diabetes). As well, a similar approach targeting multiple conditions simultaneously would be of interest. Targeting multiple chronic conditions would present challenges with respect to training healthcounselors, creating scripts, and recruiting relevant populations. The OPTIMA trial is designed as a two-arm trial, but we could have had three or four arms – usual care only, mailed education only, and mailed education plus health education. We opted for two arms (versus three or four) to ensure that all consenting subjects received some enhancement in their care and to improve the statistical power in our secondary analyses.

In conclusion, we are conducting a counseling-based intervention to improve adherence with osteoporosis medications. It is based on principles of Motivational Interviewing and aims to deliver ten one-on-one telephonic counseling sessions to Medicare beneficiaries who recently began treatment with an osteoporosis drug. We have partnered with PACE, a large state-run pharmaceutical assistance plan in Pennsylvania, to find eligible subjects and for data collection. The trial follows methodologic recommendations set out in prior systematic reviews of adherence trials.25

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Schedule of Health Counselor Calls During the 12 Months of Follow-up with Intervention Subjects

| Call | Week | Call Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | - Rapport building - General health assessment - OP knowledge assessment |

| 2 | 1 | - Self-reported med adherence assessment - Psychosocial impact of OP assessment |

| 3 | 3 | - Self-reported med adherence assessment - Adherence obstacles assessment |

| 4 | 7 | - Self-reported med adherence assessment - Adherence obstacles assessment - Falls assessment |

| 5 | 11 | - General health assessment - Self-reported med adherence assessment - Adherence obstacles assessment |

| 6 | 17 | - Self-reported med adherence - Adherence obstacles assessment |

| 7 | 23 | - Psychosocial impact of OP assessment - Self-reported med adherence assessment - Adherence obstacles assessment |

| 8 | 31 | - Falls assessment - Self-reported med adherence assessment - Adherence obstacles assessment |

| 9 | 39 | - General health assessment - Self-reported med adherence assessment - Adherence obstacles assessment |

| 10 | 52 | - Self-reported med adherence assessment - Resolution of adherence obstacles assessment - Effectiveness of education topics assessment - Summary of year |

Acknowledgement

Thomas M. Snedden and Theresa V. Brown from the Pennsylvania Department of Aging have provided encouragement at every step. As well, the recruitment of subjects has been facilitated by Care Management International.

Grant support: The OsteoPorosis Telephone Intervention to Improve Medication Adherence is supported by NIH (P60 AR 047782).

Footnotes

Clinical Trials Number: NCT00567294

There are no potential conflicts to report.

Contributor Information

Daniel H. Solomon, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Division of Pharmacoepidemiology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Timothy Gleeson, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Maura Iversen, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Jerome Avorn, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

M. Alan Brookhart, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Joyce Lii, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Elena Losina, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Frank May, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Amanda Patrick, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

William H. Shrank, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Jeffrey N. Katz, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolf RL, Zmuda JM, Stone KL, Cauley JA. Update on the epidemiology of osteoporosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2000 Feb;2(1):74–86. doi: 10.1007/s11926-996-0072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braithwaite RS, Col NF, Wong JB. Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(3):364–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tosteson AN, Melton LJ, 3rd, Dawson-Hughes B, et al. Cost-effective osteoporosis treatment thresholds: the United States perspective. Osteoporos Int. 2008 Apr;19(4):437–447. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0550-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burge R D-HB, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2007;22(3):465–475. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cranney A, Guyatt G, Griffith L, et al. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. IX: Summary of meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocrine Reviews. 2002;23(4):570–578. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-9002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, Benner J, Gwadry-Sridhar F, Nichol M. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health. 2007 Jan–Feb;10(1):3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, Miller RM, Halbert RJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007 Dec;82(12):1493–1501. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon DH, Avorn J, Katz JN, et al. Compliance with osteoporosis medications. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165(20):2414–2419. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.20.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Lyles K, Saag KG, Delzell E. Benefit of adherence with bisphosphonates depends on age and fracture type: results from an analysis of 101,038 new bisphosphonate users. J Bone Miner Res. 2008 Sep;23(9):1435–1441. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McHorney CA, Schousboe JT, Cline RR, Weiss TW. The impact of osteoporosis medication beliefs and side-effect experiences on non-adherence to oral bisphosphonates. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007 Dec;23(12):3137–3152. doi: 10.1185/030079907X242890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM. A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2007 Aug;18(8):1023–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clowes JA, Peel NF, Eastell R. The impact of monitoring on adherence and persistence with antiresorptive treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Mar;89(3):1117–1123. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delmas PD, Vrijens B, Eastell R, et al. Effect of monitoring bone turnover markers on persistence with risedronate treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Apr;92(4):1296–1304. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guilera M, Fuentes M, Grifols M, Ferrer J, Badia X. Does an educational leaflet improve self-reported adherence to therapy in osteoporosis? The OPTIMA study. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(5):664–671. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook PF, Emiliozzi S, McCabe MM. Telephone counseling to improve osteoporosis treatment adherence: an effectiveness study in community practice settings. Am J Med Qual. 2007 Nov–Dec;22(6):445–456. doi: 10.1177/1062860607307990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper A, Drake J, Brankin E. Treatment persistence with once-monthly ibandronate and patient support vs. once-weekly alendronate: results from the PERSIST study. Int J Clin Pract. 2006 Aug;60(8):896–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heather N, Rollnick S, Bell A, Richmond R. Effects of brief counselling among male heavy drinkers identified on general hospital wards. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1996 Mar;15(1):29–38. doi: 10.1080/09595239600185641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav. 1996 Nov–Dec;21(6):835–842. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reid SC, Teesson M, Sannibale C, Matsuda M, Haber PS. The efficacy of compliance therapy in pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. J Stud Alcohol. 2005 Nov;66(6):833–841. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samet JH, Horton NJ, Meli S, et al. A randomized controlled trial to enhance antiretroviral therapy adherence in patients with a history of alcohol problems. Antivir Ther. 2005;10(1):83–93. doi: 10.1177/135965350501000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogedegbe G, Schoenthaler A, Richardson T, et al. An RCT of the effect of motivational interviewing on medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans: rationale and design. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007 Feb;28(2):169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiIorio C, McCarty F, Resnicow K, et al. Using motivational interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications: a randomized controlled study. AIDS Care. 2008 Mar;20(3):273–283. doi: 10.1080/09540120701593489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Browner WS, et al. The accuracy of self-report of fractures in elderly women: evidence from a prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992 Mar 1;135(5):490–499. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ivers RQ, Cumming RG, Mitchell P, Peduto AJ. The accuracy of self-reported fractures in older people. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002 May;55(5):452–457. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00518-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haynes RB, Yao X, Degani A, Kripalani S, Garg A, McDonald HP. Interventions to enhance medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD000011. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.