Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this article is to present the rationale, study design, and methods of an ongoing randomized controlled trial assessing the efficacy of an energy psychology intervention, Tapas Acupressure Technique® (TAT®), to prevent weight regain following successful weight loss.

Design

This is a randomized controlled trial.

Settings/location

The study is being conducted at a large group-model health maintenance organization (HMO).

Subjects

The study subjects are adult members of an HMO.

Interventions

TAT is being compared to a self-directed social support comparison intervention.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure is weight-loss maintenance at 6 and 12 months postrandomization.

Conclusions

This randomized controlled trial will test the efficacy of an energy psychology intervention, TAT, by comparing it with a self-directed social support group intervention. This is, to our knowledge, the largest randomized controlled study to date of an energy psychology intervention. Positive findings would support the use of TAT as a tool to prevent weight regain following successful weight loss.

Introduction

Over 65% of all adults in the United States are overweight (with a body–mass index [BMI] of at least 25, but less than 30) or obese (with a BMI of 30 or greater).1,2 The harmful effects of overweight and obesity are well documented and include increased overall mortality3–5 and increased risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease.6–8 Weight loss has been shown to reduce the impact of cardiovascular disease risk factors on overall health and mortality,9,10 with benefits persisting as long as the weight loss is maintained.9,11–15

Behavioral and dietary interventions have been shown to be effective in inducing initial weight loss,16 and successful elements of weight-loss interventions have been identified, including an extensive series of weekly intervention contacts, regular physical activity, and accountability by self-monitoring diet and exercise.17–19 Nevertheless, weight regain is a problem following virtually all dietary and behavioral weight-loss interventions,20–23 and only a few clinical trials have systematically tested the efficacy of long-term weight-loss maintenance interventions.24 In the recently completed Weight Loss Maintenance Trial,25 monthly personal contacts emerged as a strong predictor of improved weight loss maintenance. Although these results are promising, more work is needed to optimize weight-loss maintenance strategies, including the evaluation of alternative strategies for weight control.

Potential Role of Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) approaches for obesity and weight control are popular and appealing.26–28 A variety of CAM modalities, such as acupuncture, acupressure, meditation, stress reduction, and guided imagery have been used as primary or ancillary approaches to weight management,26,29,30 and hold potential appeal for helping individuals maintain or increase weight loss following successful weight-loss interventions. However, few studies have demonstrated efficacy for these techniques.30–33 Studies suggest that some types of CAM interventions, such as energy healing and mind–body techniques, hold potential appeal for helping patients maintain weight loss, or continue a weight-loss trajectory, after successfully completing an initial weight-loss intervention.30 Training in energy healing techniques could provide individuals with a convenient and practical tool for managing stress, controlling food cravings, and maintaining healthy lifestyle habits that could continue to be applied well beyond the conclusion of the initial weight-loss intervention. In order for the effectiveness of such interventions to be assessed in clinical trials, mind–body and energy healing protocols must adhere to strict methodological guidelines such as reproducibility, standardization of techniques, practitioner training, and treatment regimen, including length and frequency of treatment.34 This article details the rationale and methodology used in an ongoing randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of an energy healing intervention for weight-loss maintenance.

Background on Energy Psychology Interventions

Within the field of energy healing, energy psychology describes a family of interventions that involve tapping or holding specific acupoints, combined with specific mental imagery, in order to treat a wide range of medical and psychological conditions. Popular energy psychology techniques include Thought Field Therapy,®35 Emotional Freedom Technique®36 (www.emofree.com/default-blt.aspx), and Tapas Acupressure Technique® (TAT®)37,38 (www.tatlife.com). Although the efficacy of energy psychology techniques has not yet been adequately tested in randomized trials, these techniques are attractive for several reasons. First, numerous case reports and anecdotal healings suggest dramatic results across a range of medical conditions.39 Second, these techniques are popular and widely available. Third, because energy psychology approaches generally include sequential tapping or sustained light pressure on a set of acupressure points, they can refer to Chinese medicine as an explanatory model.

Tapas Acupressure Technique (TAT): Underlying Theory

Chinese medicine theorizes that the free flow of energy, or qi, through the body–mind system is essential for balance and health.40,41 If qi is blocked, overall health and balance suffer. The flow of qi occurs through a series of systemic energy pathways called meridians; one such meridian, known as panguang, or bladder meridian, functions to lift qi from the abdomen and pelvis.40 The TAT pose uses two powerful points along the bladder meridian: BL1 “bright eyes,” located at the inner canthus of the eyes, and BL10 “heavenly pillar,” located at the occiput. Palpation of these points serves to mobilize qi through the bladder meridian toward higher levels of consciousness, bringing conscious awareness and reflection to hunger and other instincts, and allowing individuals to visualize and shift their actions and points of view.41 The TAT pose further facilitates this process by palpation of a third point found between, and slightly above, the eyebrows. This area is called yin tang (the “third eye” in the Indian tradition), which is thought to calm the mind.

TAT: Practice

We selected TAT as an energy psychology approach to weight-loss maintenance because, unlike many other energy psychology interventions, TAT involves a single, simple acupoints protocol that is easy to learn, and is prescribed for all conditions. The simplicity of the technique was felt to be crucial toward developing an intervention to be standardized for a randomized controlled trial.

The TAT pose involves a light touch using the tips of the thumb and fourth finger of one hand to the area 1/8 inch above the inner corner of each eye, with the middle finger of the same hand positioned on the forehead directly above the nose and about ½ inch above eyebrow level. The other hand is placed on the back of the head, with the palm cradling the occiput and the thumb pointing down as it rests above the hairline (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

The Tapas Acupressure Technique® pose.

Individuals are instructed to concentrate their attention on each of a series of statements while maintaining the TAT pose. The series begins with a statement focusing on the target problem, followed by statements focused on healing, identifying a desired alternative to the problem, shifting toward resolution and, finally, acceptance and integration of the healing. Participants in our study are taught to follow the original TAT protocol, which consists of nine steps, as well as a simplified version involving fewer steps in order to facilitate its application. Participants are instructed to practice TAT daily. The complete protocol takes approximately 20–30 minutes, while the shortened version can be completed in 2–5 minutes and can be used throughout the day as needed. The specific instructions and script given to participants are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Steps of TAT®—Tapas Acupressure Technique®

| Intention |

| This healing is on behalf of me, all parts of me and all points of view I have ever held, my family, my ancestors, everyone involved, and everyone who would like to benefit from this healing. |

| The problem—step 1a |

| Use the statement below that works best for your situation. |

| A. Everything that led up to this ___________________________ (list one or all of the things that are bothering you) happened. |

| B. State the negative thought. |

| C. The most significant trauma that led up to this ___________________ (list problem) happened. |

| D. Everything that contributed to my resonating, identifying, and connecting with this happened. |

| The opposite of the problem—step 2a |

| Use the statement below that matches the one you used in step 1. |

| A. That happened, it's over, I'm okay and I can relax now. |

| B. It's not true that ______ (use your Step 1 negative thought here, or whatever words you choose that mean the opposite of step 1 for you). |

| C. It's over, I'm okay, and I can relax now. |

| D. That happened, it's over, and I no longer resonate, identify, or connect with it. |

| The places—step 3 |

| All the places in my mind, body, and life where this has been stored are healing now. You do not need to know what all the places are; just make the intention that they're healing now. |

| and/or |

| Thank you, God (whatever name you use), that all the places in my mind, body, and life where this has been stored are healing now. |

| The origins—step 4 |

| All the origins of this are healing now. You do not need to know what all the origins are; just make the intention that they're healing now. |

| and/or |

| Thank you, God, that all the origins of this are healing now. |

| Forgiveness—step 5 |

| • I forgive anyone who hurt me related to this and wish them love, happiness, and peace. |

| • I apologize to anyone I might have hurt related to this and wish them love, happiness, and peace. |

| • I forgive everyone I blamed for this, including myself and God. |

| It's not necessary to remember each person or hurt; just make the intention of forgiveness with your heart. |

| The Parts—step 6 |

| All the parts of me that got something from this are healing now. You do not need to know what all the parts are; just make the intention that they're healing now. |

| and/or |

| Thank you, God, that all the parts of me that got something from this are healing now. |

| Whatever's left—step 7 |

| Whatever's left about this is healing now. |

| and/or |

| Thank you, God, that whatever's left about this is healing now. |

| Now think back to the original problem. Is there any emotional charge left for you? If so, do steps 1 & 2 on that, do step 7 again, and move on. If something still persists, do a full TAT on that piece later. |

| Choosing—step 8a |

| I choose _________________________ (whatever positive outcomes you want related to this). |

| Integration—step 9a |

| • This healing and information are completely integrated now, with my grateful thanks. |

| and/or |

| Thank you, God, that this healing and information are completely integrated now. |

| While putting your attention on the integration statement: |

| • Hold the pose |

| • Switch hands (move whichever hand was in front to the back and vice versa) |

| • Cup both ears (put your little finger at the top of your ear where your ear meets your head, your thumb at the bottom of your ear where your ear meets your head, and cup the rest of your fingers behind your ears, touching both the ears and your head) |

| Quick Reminders: |

| • If you are doing TAT for the first time, begin by holding the pose for about a minute with your attention on each of the following statements: |

| TAT is too easy to work or be of any value. |

| TAT is easy and could work and be of great value. |

| I deserve to live and I accept love, help, and healing. |

| • Do each step for a few seconds up to 1 minute – whatever feels right to you. |

| • Drink at least 6–8 glasses of water on days that you do TAT. |

| • Use the wording for each step that is right for you while maintaining the meaning of the step. |

| • Limit your time with your hands in the pose to 20 minutes per day. |

| • You can rest your arms at any point—even during a step. |

| • Either hand can be in front; eyes can be open or closed. |

| • If at any point while doing TAT you find your emotions becoming stronger and the center of your focus, which rarely happens, stay in the pose and gently bring your attention back to the step you are working on. |

| • It is not necessary, nor is it recommended, to relive or re-experience past incidents in order for them to be healed. |

A 4-step version includes steps 1, 2, 8, and 9.

© 2008 TATLife.® Used with permission.

Previous Research on TAT

While the evidence base supporting the efficacy of TAT is largely anecdotal,39 a recently published pilot study suggests that TAT warrants further study as a weight loss maintenance tool.42 In this feasibility study, 92 participants who had successfully lost at least 3.5 kg in a conventional 12-week weight-loss program were randomly assigned to TAT instruction, qigong (a type of Chinese movement meditation) instruction, or a self-directed support group. At 24 weeks postrandomization, the TAT group maintained 1.2 kg more weight loss than the self-directed support group (p = 0.089), and 2.8 kg more weight loss than the qigong group (p = <0.001). Based upon these promising preliminary data, we are now conducting an adequately powered randomized controlled trial of TAT for weight-loss maintenance to determine the efficacy of TAT as a weight-loss maintenance tool.

Methods

Overall study design

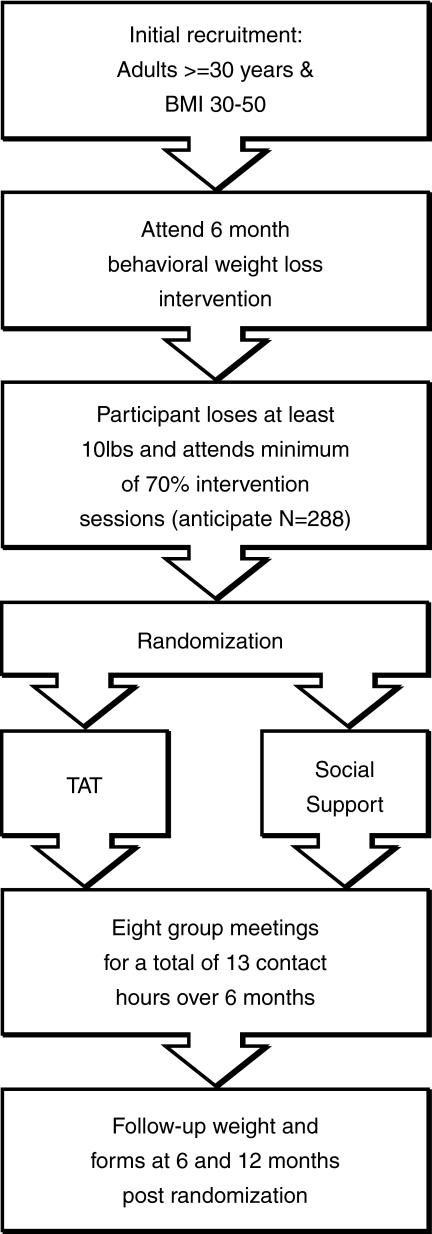

The study uses a two-arm randomized design (Fig. 2). Participants are obese adult members of an HMO who participate in an initial weight-loss phase.

FIG. 2.

Study design. BMI, body–mass index; TAT, Tapas Acupressure Technique.®

At the end of the 6-month weight-loss program, participants who have lost at least 10 pounds and attended at least 70% of the weekly group sessions are eligible for randomization into one of two arms of the weight-loss maintenance phase of the trial. The experimental intervention arm consists of instruction and application of TAT, while the control intervention arm consists of self-directed social support-group meetings. Both the intervention and control groups have identical group meeting schedules over 6 months, for a total of eight group meetings and a total of 13 contact hours. The main outcome measure is change in weight from randomization to 12 months post-randomization.

Eligibility

Participants are Kaiser Permanente Northwest members age 30 or greater with a BMI of 30–50 inclusive, weighing less than 400 pounds, and living within the metropolitan Portland, OR/Vancouver, WA area. Participants must be willing to attend all intervention sessions, and be able to participate in all aspects of the interventions. Participants must also be willing to accept random assignment to a maintenance intervention, and to provide informed consent.

Medical exclusions include recent (within the previous 2 years) cardiovascular event, cancer treatment, or inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. Diabetic patients injecting insulin, those taking weight-loss medications, those who have undergone bariatric surgery, and those who have had liposuction over the previous year are excluded. Additional exclusions include prior acupuncture or acupressure for weight management, planning to leave the metropolitan area prior to the end of the program, body weight loss of more than 20 pounds over the prior 6 months, pregnant or breast feeding, participation in another clinical trial, and household members of study staff or another study participant.

Recruitment

We recruit participants from Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) membership and staff. Two outreach strategies are implemented. First, we identify potentially eligible participants electronically from KPNW administrative databases, and mail them a postcard inviting their participation. Second, we use a variety of media to publicize the study broadly among KPNW members and employees. These approaches include e-mails to broad distribution lists of employees, postings in employee newsletters, articles in member-directed health and wellness publications, and announcements on the member-directed Web site. We also have given presentations about the project at numerous clinical department meetings, and have provided KPNW clinics with brochures for distribution to patients. The emphasis in all recruitment materials is on weight management, as opposed to CAM.

Individuals interested in the study contact recruiters either by voicemail, e-mail, or through a secure Web site. Those who are interested and potentially eligible are scheduled for a group information session to learn more about the study. At the information session, the principal investigator provides a general overview of the study and answers questions. Those interested in considering enrollment sign up for an individual study visit to determine final eligibility and proceed with enrollment.

Initial weight-loss treatment

The initial weight-loss treatment consists of a standard 6-month, behavioral weight-loss program. During this phase, participants attend weekly groups meetings lasting 90 minutes each. Participants are instructed to reduce calories consumed by eating a healthy low-fat diet, rich in fruits and vegetables. Additionally, participants are encouraged to keep daily records of all foods and beverages consumed and exercise at moderate intensity most days, working up to 180 minutes per week. Details of the initial weight-loss intervention have been described elsewhere.25,43–45

Randomization

Participants are randomized to the two maintenance interventions in equal numbers, using simple, blocked randomization. We balance entry into the two treatment arms using permuted blocks, with the block-size masked from all except the statistician and programmer. The planned primary analysis includes statistical adjustments for gender, age, race, initial weight, and weight loss during the weight-loss phase. This method is simple to implement with limited staff and study resources. The clinic staff has a sequence of sealed envelopes, each with a concealed randomization code inside. After completion of eligibility, the staff member opens the envelope and tells the participant which arm s/he has been assigned to. The code is a self-adhesive label that can be put on the randomization log, which is used to assure that codes are handed out in the correct order.

Study participants know their intervention assignments, as do study staff who deliver the maintenance interventions. However, all clinical staff involved in follow-up data collection are blinded to participants' intervention assignment.

Weight-loss maintenance interventions

TAT curriculum

A curriculum guide was developed detailing the content for each TAT weight-loss maintenance session, with an 8-session group format informed by participant feedback from the pilot study.42 Session one of the TAT intervention is a 2-hour group introduction to TAT and includes instruction on the TAT pose, background, and underlying theory. Sessions two and three, conducted 1 and 3 weeks later, respectively, are 90-minutes long and involve additional TAT practice. The following four TAT sessions, each 90-minutes long, are conducted monthly, and the eighth and final TAT session is 2 hours long, to allow for group closure. Total contact time is 13 hours. Table 2 provides details of the curriculum for each of the eight TAT sessions.

Table 2.

Tapas Acupressure Technique® (TAT®) Weight-Loss Maintenance Curriculum

| Session number | Synopsis of class content |

|---|---|

| 1 | The meeting begins with introductions, a review of overall goals, and the establishment of group rules. Participants review their weight-loss and weight-maintenance challenges as a group, and the TAT facilitator provides an overall introduction about TAT: what it is and how it might help them with their weight control. The TAT pose is taught to participants and the steps of the TAT are introduced. The participants then practice their first TAT as a group. The focus of this TAT is an abbreviated 4-step protocol on addressing any resistances to the use of TAT. Participants then spend the rest of the session learning about the 4- and 9-step TAT protocols that they will use at home. Participants are encouraged to drink water at the conclusion of each TAT session. They receive a TAT CD and a booklet focused on weight loss, and are instructed to practice TAT daily between sessions on an issue of their choice related to their weight-loss or maintenance challenges. |

| 2 | The TAT facilitator asks participants' feedback on the use of TAT since the first session, and addresses their questions and concerns. The facilitator also asks about continuing obstacles to weight-loss maintenance. Then TAT is practiced, as a group, related to issues participants bring up. The facilitator teaches participants alternate wording options for each step of the TAT protocol, and highlights the need for an emotional charge or feeling to be connected to the problem statement used by participants in step 1. The facilitator introduces the concept of limiting beliefs, which are beliefs people have learned or created to deal with experiences in their lives. Such self-stories may drive current behavior without our awarereness. An example is the internal limiting belief: “Food makes me feel better when I am upset.” The importance of daily TAT practice is emphasized, with a focus on overcoming roadblocks and limiting beliefs that affect weight-loss maintenance. Participants do a group TAT on everything that might limit them from doing TAT in the next 2 weeks. They are encouraged to practice TAT daily until the next meeting. |

| 3 | The facilitator discusses the importance of thoughts and emotions, as they impact health and behavior. The concept of “cellular memory” is introduced to highlight the interplay between previous experience, emotions, and physiology. The facilitator uses these concepts to show how focusing on the problem and then on its opposite, through TAT, can shift perspective and behavior. Participants break into 2-person teams and lead each other through a TAT focusing on a negative thought related to weight-maintenance issues. |

| 4 | The facilitator teaches the 9-step TAT protocol in more depth. The concepts of “triggers” to eating and self-sabotage statements are introduced and participants are led in a full 9-step TAT using the “TAT That” Weight Loss cards. |

| 5 | The facilitator introduces the concept of “creating the life you want.” A group TAT is done on this theme. The one-step method of TAT is taught. Together, the group lists all the things they could do TAT on, and then discuss the word “fat.” A group TAT is done on reactions to, and past experiences with, this word. |

| 6 | A discussion is led on the theme of clearing “past incidents and traumas.” A group TAT is done focusing on one past incident each person wants to clear up. |

| 7 | The facilitator solicits how people are using TAT and leads a one-step on everyone being able to do successful TATs on these issues. The issue of how to clear allergies with TAT is addressed. The group breaks into smaller groups and does TAT on issues of their choice. The group ends with doing a TAT on the subject of using TAT when they need it. |

| 8 | The group plans for continuing the use of TAT at home and the facilitator solicits and addresses any remaining roadblocks to the use of TAT. Then the group does a TAT on how they will be able to use this tool for continued weight-loss maintenance. Participants are reminded of the basics of TAT and the need to drink water after doing TAT. Group issues and concerns about being without the group after this evening are sought. The final activity is a group TAT on being okay with this group ending and being able to continue TAT on their own for their weight maintenance. |

Practitioner training

A training protocol was developed to standardize the intervention delivery by TAT facilitators. Study facilitators underwent certification as both certified TAT Professionals and TAT Trainers. This training was provided by the certifying agency, TATlife, and included (1) 60 hours of workshop attendance; (2) home study of print and audiovisual curricular materials; (3) documentation of 50 TAT sessions on self, 50 on clients, and 15 on fellow trainees; and (4) final evaluation of two TAT sessions, either live or via video, by a certified TAT trainer. Three (3) TAT facilitators are involved in the delivery of TAT instruction in the project.

Prior to the beginning of group instruction, TAT facilitators were provided with a copy of the program curriculum and met with the lead TAT facilitator to review the study protocol and curriculum, and clarify any questions.

Quality control

The study has implemented several quality-control procedures to assure correct and uniform adherence to the TAT curriculum and protocol. First, a rating tool developed for the study is completed after each session by both the TAT facilitator as well as by investigators or study staff who regularly observe the session. The session rating includes the percentage of time devoted to TAT mechanics, weight-management issues and other topics, and a description of any activities that may have deviated from the curriculum guide. Monthly conference calls involving the project director, investigators, and TAT facilitators, provide an opportunity to share experiences, address logistic concerns, and preserve consistency and adherence to the treatment protocol in the delivery of the TAT curriculum.

Comparison intervention

The control-group intervention consists of a facilitated self-directed social support group matched to the TAT intervention at the levels of meeting format and contact hours. Participants at these sessions share experiences and suggestions related to weight-loss maintenance strategies in a supportive environment. Sessions begin with a “check in” period where participants report on progress and concerns. The group facilitator then encourages discussion of a weight-management-related theme. Topics include roadblocks to weight maintenance, emotional reactions to stress, maintaining balance, and approaches to managing food and exercise. Although the groups are facilitated, the meetings serve as an attention control. The role of the facilitator is to manage meeting logistics and guide the group discussion. No new materials or skill sets are introduced.

Conclusions

In this article, we have detailed the rationale and methodology of an ongoing randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of an energy healing intervention for weight loss maintenance. We have aimed for implementation of a practical, generalizable, and broadly reproducible program. This is, to our knowledge, the largest randomized controlled study to date of energy psychology, and the only study beyond our own pilot evaluating any energy psychology intervention for weight loss maintenance. Positive findings from this study would support the use of TAT as a weight-loss maintenance tool in a variety of care settings.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by a grant (5R01AT003928) from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ogden CL. Carroll MD. Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franks P. Muennig P. Lubetkin E. Jia H. The burden of disease associated with being African-American in the United States and the contribution of socio-economic status. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:2469–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM. Graubard BI. Williamson DF. Gail MH. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005;293:1861–1867. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams KF. Schatzkin A. Harris TB, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. NEJM. 2006;355:763–778. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olshansky SJ. Passaro DJ. Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. NEJM. 2005;352:1138–1145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr043743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickey RA. Janick JJ. Lifestyle modifications in the prevention and treatment of hypertension. Endocr Pract. 2001;7:392–399. doi: 10.4158/EP.7.5.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann JI. Diet and risk of coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2002;360:783–789. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09901-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubbert PM. Carithers T. Sumner AE, et al. Obesity, physical inactivity, and risk for cardiovascular disease. Am J Med Sci. 2002;324:116–126. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knowler WC. Barrett-Connor E. Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. NEJM. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douketis JD. Macie C. Thabane L. Williamson DF. Systematic review of long-term weight loss studies in obese adults: Clinical significance and applicability to clinical practice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:1153–1167. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens VJ. Obarzanek E. Cook NR, et al. Long-term weight loss and changes in blood pressure: Results of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, Phase II. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction of the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. NEJM. 2002. pp. 393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Wing RR. Hamman RF. Bray GA, et al. Achieving weight and activity goals among diabetes prevention program lifestyle participants. Obes Res. 2004;12:1426–1434. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindstrom J. Ilanne-Parikka P. Peltonen M, et al. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: Follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study [see comment] Lancet. 2006;368:1673–1679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman WH. Hoerger TJ. Brandle M, et al. The cost-effectiveness of lifestyle modification or metformin in preventing type 2 diabetes in adults with impaired glucose tolerance [see comment] Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:323–332. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-5-200503010-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wadden TA. Butryn ML. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32:981–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(03)00072-0. x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffery RW. Drewnowski A. Epstein LH, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: Current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19:5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wing RR. Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:222S–225S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill JO. Thompson H. Wyatt H. Weight maintenance: What's missing? J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:S63–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wadden TA. Butryn ML. Byrne KJ. Efficacy of lifestyle modification for long-term weight control. Obes Res. 2004;12(suppl):151S–162S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeffery RW. Drewnowski A. Epstein LH, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: Current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19:5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wadden TA. Crerand CE. Brock J. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28:151–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2004.09.008. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dansinger ML. Tatsioni A. Wong JB, et al. Meta-analysis: The effect of dietary counseling for weight loss [see comment] Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:41–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turk MW. Yang K. Hravnak M, et al. Randomized clinical trials of weight loss maintenance: A review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;24:58–80. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317471.58048.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svetkey LP. Stevens VJ. Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: The weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharpe PA. Blanck HM. Williams JE, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine for weight control in the United States [see comment] J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:217–222. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.6129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnes PM. Bloom B. Nahin R. CDC National Health Statistics Report #12. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McFarland B. Bigelow D. Zani B, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in Canada and the United States. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1616–1618. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ernst E. Acupuncture/acupressure for weight reduction? A systematic review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1997;109:60–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pittler MH. Ernst E. Complementary therapies for reducing body weight: A systematic review. Int J Obesity. 2005;29:1030–1038. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans M. Straus S. Ripe for study: Complementary and alternative treatments for obesity. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2001;41:35–37. doi: 10.1080/20014091091698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shumaker SA. Schron EB. Ockene JK. McBee WL. The Handbook of Health Behavior Change. 2nd. New York, NY: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ludwig DS. Pereira MA. Kroenke CH, et al. Dietary fiber, weight gain, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in young adults. JAMA. 1999;282:1539–1546. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warber SL. Gordon A. Gillespie BW, et al. Standards for conducting clinical biofield energy healing research. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(3suppl):A54–A64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Callahan RJ. Turbo R. Tapping the Healer Within: Using Thought Field Therapy to Instantly Conquer Your Fears, Anxieties, and Emotional Distress. Chicago: Contemporary Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Center for EFT. www.emofree.com. [Jul 16;2009 ]. www.emofree.com

- 37.Tapas Acupressure Technique. www.tatlife.com. [Jul 16;2009 ]. www.tatlife.com

- 38.Fleming T. You can heal now: the Tapas Acupressure Technique (TAT) Redondo Beach, CA: TAT International; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feinstein D. Energy psychology: a review of the preliminary evidence. Psychother Theory Res Practice Training. 2008;45:199–213. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chu Z. Fundamentals of Chinese Medicine (Translated by Wiseman N, Ellis A) Brookline, MA: Paradigm Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jarrett L. The Clinical Practice of Chinese Medicine. Stockbridge, MA: Spirit Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elder C. Ritenbaugh C. Mist S, et al. Randomized trial of two mind–body interventions for weight-loss maintenance. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:67–78. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.6237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brantley PJ. Appel LJ. Hollis JF, et al. Design considerations and rationale of a multicenter trial to sustain weight loss: The weight loss maintenance trial. Clin Trials. 2008;5:546–556. doi: 10.1177/1740774508096315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Svetkey LP. Harsha DW. Vollmer WM, et al. PREMIER: A clinical trial of comprehensive lifestyle modification for blood pressure control: Rationale, design and baseline characteristics. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:462–471. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Funk KL. Elmer PJ. Stevens VJ, et al. PREMIER: A trial of lifestyle interventions for blood pressure control. Intervention design and rationale. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9:271–280. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]