Abstract

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after sexual exposure to HIV is recommended by state and national agencies. A cross-sectional survey of 117 Los Angeles County sites found 17 sites offering PEP (14.5%); Ten sites offer PEP to patients who are uninsured (8.5%). General availability of PEP should be a public health priority.

Keywords: HIV Prevention, post-exposure prophylaxis, antiretroviral agents, service delivery

BACKGROUND

Los Angeles County (LAC), spanning 4000 square miles and home to 9.95 million people, represents 3.5% of the US population and 27% of the population of California. Los Angeles disproportionately contributes 40% of California’s incident HIV-1 infections. Men who have sex with men (MSM) represent 53% of new HIV infections nationally,1 and 72% of incident HIV infections in LAC.2

In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) endorsed a protocol for the administration of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after high-risk suspected sexual exposure to HIV.3 The California State Office of AIDS has endorsed such a protocol since 2004.4 PEP, the administration of a course of antiretroviral therapy after a suspected HIV exposure has been criticized for its high costs.5 However, PEP is highly cost effective with appropriate use, and cost-saving for highest-risk exposures.6 In San Francisco, PEP after sexual exposure to HIV-1 was demonstrated to be safe and feasible, administering PEP to 858 subjects in two studies, over 15 and 18-month enrollment periods. 7–9

In Los Angeles, finding providers and sites willing to accept referrals of patients seeking PEP services is difficult, particularly for patients without private insurance. We therefore sought to assess the prevalence of service availability in LAC, with a goal of quantifying the current deficit of programmatic service provision.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional survey of PEP knowledge and service availability in point-of-care healthcare venues in LAC, as defined by zip code boundaries. The UCLA IRB was consulted and determined that this study did not require IRB approval.

Study Population

The study sample was a random sample of point-of-healthcare venues, identified from internet search engine queries (Google (www.google.com), searching on keywords of the location type “primary care,” “urgent care,” “Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD)” etc.) for each location type within LAC, identified by zip code. Over 400 such sites were identified via search engine, and every 2nd facility was selected for listing, with a goal of surveying 200. Facilities were coded as belonging to one of the following 7 institution types: Primary Care, HIV/Infectious Disease (ID) subspecialty care, STD clinics, community-based organizations (CBO’s) offering HIV prevention services, university health clinics, urgent care clinics, and hospital emergency departments (EDs). An initial call-list of 213 sites was randomly generated from the master internet search results; 117 were willing to participate in the telephone survey.

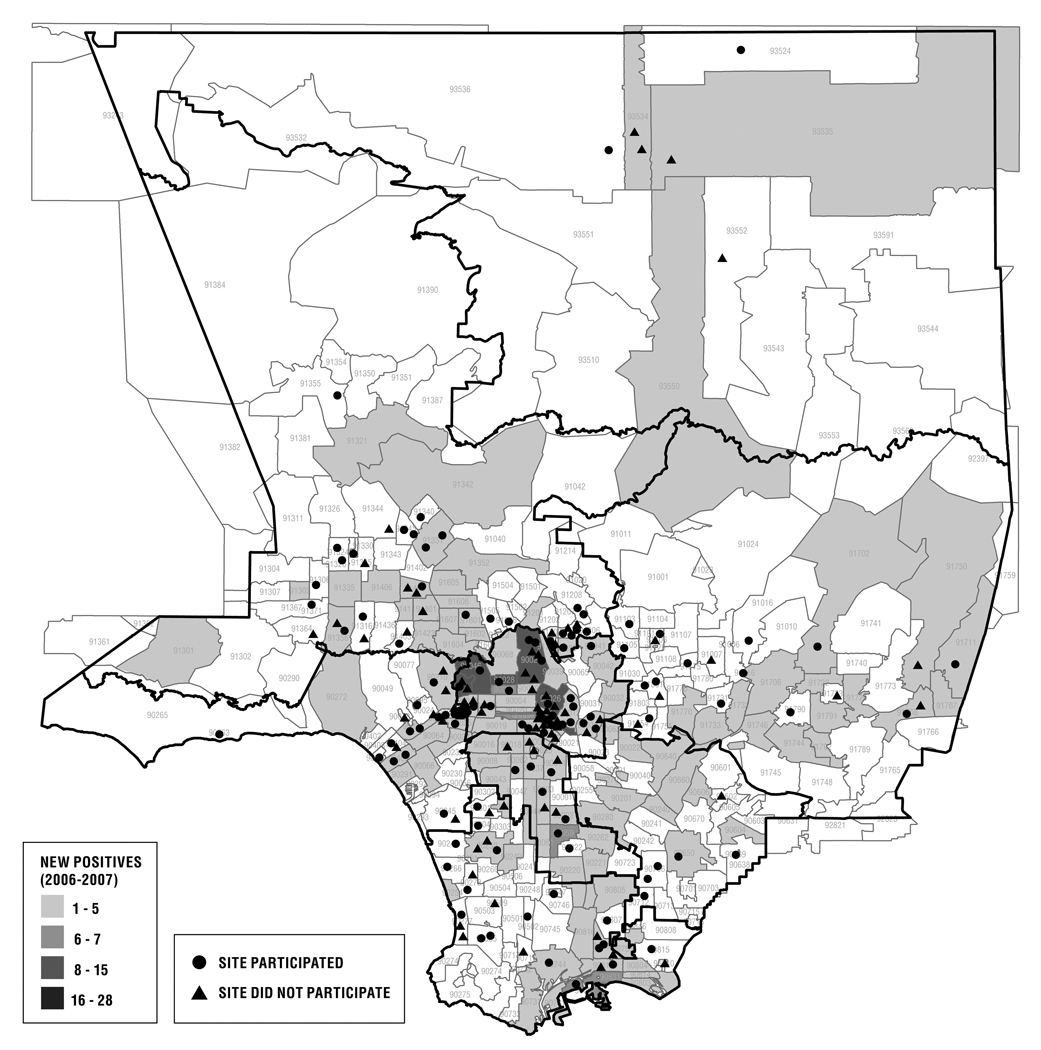

Across service provision areas of LAC, prevalent infections are uniformly MSM-predominant;10 although questions related to MSM-focused service-delivery were not part of this study, Figure 1 details the locations of participating and non-participating sites relative to incident 2006-7 HIV infections in LAC, demonstrating broad distribution of service-provision sites across affected areas.

Figure 1.

Sites selected for telephone assessment of PEP service provision in Los Angeles County

Study Procedures

At each participating site, the initial individual answering the telephone was surveyed in order to best simulate the experience of a patient seeking services.

Statistical Analysis

Predictors of PEP availability at healthcare venues were assessed using multiple logistic regression modeling with location type, neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES) and distance from a major academic medical center as predictors. Neighborhood SES, assessed as median household income of the zip code in which the healthcare venue resides, was evaluated as a covariate. SES data was abstracted from the 2000 Decennial Census of Population and Housing Public Database using Beta Data Ferrett Version 1.3.3. Distance to one of 5 major academic hospital centers (UCLA Medical Center, County-USC Medical Center, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, and Olive View Medical Center) was calculated as the minimum value of the automobile driving directions to any of the 5 locales using Google Maps (http://maps.google.com). All statistical analyses were done using SAS Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

One hundred seventeen sites participated in the telephone assessment. Venues participating in the survey were not different in distribution from those not participating (p=0.16, chi-squared test). Seventeen of the 117 sites offer PEP services (14.5% [95% CI 8.1-20.9]). Ten of those 17 sites (58.8%) are able or willing to provide such services to uninsured/Medicaid patients, representing 8.5% of healthcare venues [95% CI 3.5-13.6] (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Predictors of PEP availability | Availability of PEP Services* |

OR Venue Type vs. all other (95% CI) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95%CI) |

Avail of PEP Services to Uninsured† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venue Type | |||||

| Primary Care (n=33) | 1 (3.0%) | 0.13 [0.02-1.05] |

0.05 [0.01-0.45] |

0.05 [0.01-0.50] |

0 |

| Urgent Care (n=15) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.89 [0.18-4.36] |

0.24 [0.04-1.41] |

0.27 [0.04-1.64] |

0 |

| CBO (n=10) | 2 (20%) | 1.53 [0.30-7.93] |

0.39 [0.06-2.42] |

0.38 [0.06-2.58] |

0 |

| STD (n=17) | 1 (5.9%) | 0.33 [0.04-2.65] |

0.10 [0.01-0.92] |

0.10 [0.01-0.99] |

1 (5.9%) |

| ER (n=18) [Ref] | 7 (38.9%) |

5.67 [1.79-17.90] |

1 | 1 | 7 (38.9%) |

| HIV (n=10) | 3 (30%) | 2.85 [0.66-12.31] |

0.67 [0.13-3.51] |

0.70 [0.13-3.84] |

2 (20%) |

| University (n=14) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.42 [0.05-3.43] |

0.12 [0.01-1.14] |

- | 0 |

p=0.01, Fisher exact test

p=0.003, Fisher exact test

Hospital EDs were associated with 5.67-fold increased odds (95% CI 1.79 – 17.90) for finding services compared to all other venue types. In multivariable analysis adjusted for neighborhood SES and distance from a major academic center, a primary care physician’s office (OR 0.05 [95% CI 0.01 – 0.50]) or a sexually transmitted disease clinic (OR 0.10 [95% CI 0.01-0.99]) was significantly less likely to provide PEP than was an ED. Uninsured subjects were also more likely to find access to PEP services in hospital EDs than non-ED locations (p=0.003) [Table 1].

Median income values for the zip-code in which the venue resides were not different between locations offering PEP and those not offering PEP ($39,747 vs. $32,339, p=0.41). However, median income levels were significantly lower in areas containing healthcare venues offering PEP to uninsured subjects compared to areas containing venues providing PEP only to privately-insured subjects ($29,657 vs. $53, 891, p=0.025).

Driving proximity to one of 5 major academic medical centers in metropolitan Los Angeles was not associated with availability of PEP services.

DISCUSSION

In this randomly selected sample of 117 healthcare venues in LAC, 17 (14.5%) were able to offer PEP services. This is consistent with clinical reports of patients being unable to access such services in Los Angeles. Only ten (8.5%) of these reported being able to offer services to subjects who were not privately insured.

The venue type providing the greatest likelihood of finding PEP services was EDs; however, in the current utilization era, EDs are resource-strained11, 12, and in our clinical experience, suboptimal venues for providing PEP services: a time-sensitive and time-intensive service package which requires extraction of sensitive information, triage, and rapid and skilled management of testing and medication administration with coordination of follow-up. In our survey, 38.9% of EDs provide PEP for privately-insured patients; and those EDs that do so also offer them to non-privately insured patients. The County hospital system in California, the primary emergency service system for uninsured and MediCal (California State Medicaid) patients is particularly strained.12 Numerous examples have come to our attention of patients being turned away from EDs after seeking PEP services after being deemed “inappropriate” for ED evaluation; even if evaluated in EDs, most will at best provide a 3 or 4-day “starter” supply of PEP medication, leaving patients to arrange their own follow-up, including finding the remainder of the recommended 28-day course of treatment.

A major limitation of this study is that we did not investigate the details of the precise service package of medications and follow-up services provided at each site endorsing PEP provision. This study is also limited by potential selection bias; it is possible that sites offering PEP services are not referenced in the search engines used to identify sites. Additionally, only the initial phone respondent at each site was surveyed, which may underestimate PEP service availability if the primary respondent were not well informed; however the goal was to simulate a patient’s experience in the seeking of such services. In such cases, service availability is only relevant if those seeking it can access it. We also classified each healthcare venue site solely based on its self-identification via internet search engine. This may have resulted in misclassification of some sites with regard to venue type and obscured or created artificial associations.

Los Angeles represents a challenging geography for implementation of biomedical HIV prevention services given its wide geography. Even though across the county the epidemic is consistently driven by MSM behavior,13 cultural, ethnic, and sociodemographic compartmentalization of the county obligates a locally defined model for service delivery rather than a “one-size-fits-all” program.

Despite state and national guidelines endorsing PEP after high-risk sexual and injection drug-use exposures, uptake and demand for such services has not been widespread, although pilot research programs of such services have been well subscribed in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston.8, 14–16

Amid concerns that PEP availability might increase risk-taking sexual behavior 17, 18 and budgetary constraints, the optimal role for PEP within prevention-services programming has remained unclear. While direct efficacy data for PEP in a non-occupational setting is likely to continue be absent from the literature, analogy to occupational (i.e. needle stick) PEP strategies, the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) literature, and animal models suggest substantial (>80%) protective efficacy if treatment is administered rapidly (< 72 hours) after an exposure and continued for 28 days.19 If an 80% effective vaccine were available, there would be considerable excitement in the prevention community. Sparse uptake of PEP by providers and public health agencies demonstrates suboptimal utilization of currently available prevention technologies in an era where safe and effective vaccines and microbicides are elusive20, 21 and the HIV epidemic is continuing to devastate communities.

CONCLUSIONS

Post-exposure prophylaxis services are available at limited sites in LAC; fewer options are available for non-privately insured patients.

Public and private initiatives are required to integrate biomedical technologies such as PEP into current behavioral risk reduction programming as part of comprehensive prevention services.

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Arun Karlamangla in the data analysis for this study, and Mr. Jun Ohnuki for the creation of Figure 1. We wish to thank all the sites that participated in this study.

Funding Source:

None

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

Raphael Landovitz has received speaking honoraria from an independent CME company which received an unrestricted educational grant from Pfizer.

Kory Combs – None

Judith Currier has received consulting fees from Glaxo SmithKline.

References

- 1.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV Incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.HIV Epidemiology Program HIV/AIDS Surveillance Summary. 2008 (Accessed at http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/wwwfiles/ph/hae/hiv/HIVAIDS%20Semiannual_report_July_2008.pdf, Accessed December 12, 2008)

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV in the United States: Recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2005 January 21; 2005. [PubMed]

- 4.California Task Force on Non-Occupational PEP and the California Department of Health Services Office of AIDS. Offering HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) following non-occupational exposures: Recommendations for health care providers in the state of California. Sacramento, CA: 2004. Jun, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Low-Beer S, Weber AE, Bartholomew K, et al. A reality check: the cost of making post-exposure prophylaxis available to gay and bisexual men at high sexual risk. AIDS. 2000;14:325–326. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200002180-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinkerton SD, Martin JN, Roland ME, Katz MH, Coates TJ, Kahn JO. Cost-effectiveness of postexposure prophylaxis after sexual or injection-drug exposure to human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:46–54. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn JG, Pinkerton SD, Paltiel AD. Postexposure prophylaxis following HIV exposure [letter; comment] Jama. 1999;281:1269–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roland M, Coates T, Robillard H, et al. Demand for a non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis telephone study referral line exceeds resources; 10th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2003 February 10–14; Boston, MA. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roland MNT, Krone M, Frances K, Chesney M, Kahn J, Coates T, Martin J. A randomized trial of standard versus enhanced risk reduction counseling for individuals receiving post-exposure prophylaxis following sexual exposures to HIV; 13th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Denver, CO. 2006. Abstract #902; 2006, Abstract #902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.HIV Epidemiology Program Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Summary July 2008: 1–30. 2008:17. In: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/wwwfiles/ph/hae/hiv/HIVAIDS%20Semiannual_report_July_2008.pdf, ed. Los Angeles County Office of AIDS Programs and Policy.

- 11.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Lasser KE, et al. Waits to see an emergency department physician: U.S. trends and predictors, 1997–2004. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:w84–w95. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.w84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambe S, Washington DL, Fink A, et al. Waiting times in California's emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:35–44. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office of AIDS Programs and Policies Map Reference Book. 2008 (Accessed at http://www.lapublichealth.org/AIDS/reports/OAPP%20Map%20Reference%20Book.pdf, accessed December 12, 2008.)

- 14.Kahn JO, Martin JN, Roland ME, et al. Feasibility of postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) against human immunodeficiency virus infection after sexual or injection drug use exposure: the San Francisco PEP Study. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:707–714. doi: 10.1086/318829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ, Cohen D, et al. Tenofovir DF Plus Lamivudine or Emtricitabine for Nonoccupational Postexposure Prophylaxis (NPEP) in a Boston Community Health Center. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:494–499. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318162afcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shoptaw S, Rotheram-Fuller E, Landovitz R, et al. Non-occupational Post Exposure Prophylaxis as a Biobehavioral HIV Prevention Intervention. AIDS Care. 2008;20:376–381. doi: 10.1080/09540120701660353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin JN, Roland ME, Neilands TB, et al. Use of postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection following sexual exposure does not lead to increases in high-risk behavior. Aids. 2004;18:787–792. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403260-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schechter M, do Lago RF, Mendelsohn AB, Moreira RL, Moulton LH, Harrison LH. Behavioral impact, acceptability, and HIV incidence among homosexual men with access to postexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV. J Acq Immun Defic Syndr. 2004;35:519–525. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wade NA, Zielinski MA, Butsashvili M, et al. Decline in perinatal HIV transmission in New York State (1997–2000) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:1075–1082. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van damme L, Govinden R, Mirembe FM, et al. Lack of Effectiveness of Cellulose Sulfate Gel for the Prevention of Vaginal HIV Transmission. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:463–472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letvin NL. Progress and obstacles in the development of an AIDS vaccine. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:930–939. doi: 10.1038/nri1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]