Abstract

Disclosure is a critical aspect of the experience of people who live with concealable stigmatized identities. This article presents the Disclosure Processes Model (DPM)— a framework that examines when and why interpersonal disclosure may be beneficial. The DPM suggests that antecedent goals representing approach and avoidance motivational systems moderate the effect of disclosure on numerous individual, dyadic, and social contextual outcomes and that these effects are mediated by three distinct processes: (1) alleviation of inhibition, (2) social support, and (3) changes in social information. Ultimately, the DPM provides a framework that advances disclosure theory and identifies strategies that can assist disclosers in maximizing the likelihood that disclosure will benefit well-being.

Keywords: disclosure, concealable stigmatized identities, psychological inhibition, approach, avoidance, goals, social support

Self-disclosure, or the sharing of personal information with others through verbal communication, is an integral part of social interaction. Disclosure can provide an opportunity to express thoughts and feelings, develop a sense of self, and build intimacy within personal relationships (Derlega, Metts, Petronio, & Margulis, 1993; Jourard, 1971). Disclosure is also thought to be a critical component in building client-practitioner relationships and in enabling therapeutic progress (for a review, see Kelly, 2002). Thus, given these far-ranging positive outcomes and purposes of disclosure, it might at first appear that disclosure is advantageous for people's well-being.

However, when people who bear a concealable stigmatized identity (Pachankis, 2007; Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009; Quinn, 2006)—personal information that is socially devalued but is not readily apparent to others, such as mental illness, experiences of abuse or assault, or an HIV-positive diagnosis—disclose this information to others, they risk experiencing negative outcomes or even becoming the targets of prejudice. In these cases, decisions to disclose concealable stigmatized identities are much more complex because they may yield unfavorable outcomes such as social rejection and discrimination. For example, people who “come out of the closet” about their sexual orientation continue to be victims of hate crimes, verbal harassment, and employment or housing discrimination (Herek, 2009). Thus, disclosing a concealable stigmatized identity may be a highly complex process because it can yield the potential for both benefit and harm.

When will disclosure yield benefit rather than harm? Consider, for a moment, two individuals who are making the difficult decision about whether to disclose their concealable stigmatized identity. One is a young man named Jason who feels guilty and ashamed about keeping his HIV-positive status concealed from his father, but worries that his father will react negatively. Jason decides to tell his father because he doesn't want to have to live with the burden of keeping this secret and tries to avoid being disowned by him. Another is a middle-aged woman living with HIV named Susan whose romantic relationship has recently become more serious. She decides to tell her partner about her HIV infection because she wants to protect his health and share this important part of herself in order to strengthen their relationship. In which of these situations is disclosure more likely to be beneficial?

Existing research and theorizing provides some answer to this question, predominantly emphasizing the reaction of the confidant. A growing literature suggests that the reaction of the confidant is one of the most important factors predicting whether disclosure will be beneficial or not. In a longitudinal examination of disclosure of abortion, women who disclosed but felt that their confidant was not fully supportive did not show benefits of disclosure in the form of lower psychological distress (Major et al., 1990). Experimental manipulations have also revealed similar findings, indicating that participants do not experience the benefits of disclosure when confidant reactions are neutral or negative (Lepore, Ragan, & Jones, 2000; Rodriguez & Kelly, 2006). This evidence suggests that Jason and Susan may be equally likely to benefit from disclosure when their confidants respond in positive or supportive ways.

Are the outcomes of disclosure completely contingent on how the confidant reacts, or are there attributes of the disclosers—the goals they possesses for disclosure, how they communicate about the identity, and how they cope with the confidant response—that can affect this process and determine when disclosure will be beneficial? Put differently, might the goals, communication skills, and coping abilities of Jason and Susan affect the outcomes of their disclosure events as well?

To date, very little research has considered these possibilities. We suggest that there are two reasons why research is lacking in this domain, limiting empirical understanding of when disclosure may be beneficial. First, research examining disclosure dynamics among people living with concealable stigmatized identities has largely focused on examining two separate processes: (1) how people make decisions to disclose, and (2) how people are affected by their disclosure decisions. Frequently, empirical and theoretical examinations of disclosure focus solely on antecedent factors that may affect the decision-making process, such as goals, anticipated negative confidant responses, and the type of confidant relationship, without attending to the outcomes of these decisions (e.g., Derlega, Winstead, Greene, Serovich, & Elwood, 2004; Goodman-Brown, Edelstein, Goodman, Jones, & Gordon, 2003; Omarzu, 2000; Schneider, 1986; Tröster, 1998). Similarly, other empirical and theoretical examinations focus solely on the outcomes of disclosure without attending to the antecedent factors that led these individuals to disclose (e.g., Rodriguez & Kelly, 2006; Smart & Wegner, 1999). Thus, beyond a few notable exceptions (Clair, Beatty, & Maclean, 2005; Garcia & Crocker, 2008; Major & Gramzow, 1999), the disclosure literature has largely examined these two processes separately, making it unclear how the full disclosure process unfolds.

Second, because antecedents and outcomes have infrequently been examined together, there has been relatively little theorizing regarding how the factors that lead people to disclose may impact these outcomes. In recent years, several researchers have proposed process models of disclosure that represent aspects of the full disclosure process—how people make decisions to disclose, choose confidants, communicate about their identities, and are affected by disclosure (Clair et al., 2005; Greene, Derlega, & Mathews, 2006; Ragins, 2008). However, none of these models speculate as to how what occurs in the decision-making part of the process may affect the rest of the disclosure process—how people communicate about their identity and how the event ultimately affects their outcomes. Thus, there has been a gap between extant theoretical and empirical conceptualizations of disclosure and its practical functioning in real world settings. In practice, disclosure is a complex behavioral process that involves sustained self-regulatory efforts—exerting self-control in order to make disclosure decisions, communicate effectively, and cope with the outcomes of disclosure—and empirical analysis has largely failed to understand the interrelations among the component parts of the disclosure process.

In addition to understanding when disclosure will be beneficial for people, it is also necessary to understand why disclosure affects well-being. Functionally, disclosure can affect a wide variety of outcomes, including individual psychological (e.g., Major et al., 1990; Major & Gramzow, 1999; Ullman & Filipas, 2001; Zea, Reisen, Poppen, Bianchi, & Echeverry, 2005), behavioral (e.g., Broman-Fulks et al., 2007; Farina, 1971; Quinn, Kahng, & Crocker, 2004; Simoni & Pantalone, 2005), and health (e.g., Greenberg & Stone, 1992; Ullrich, Lutgendorf, & Stapleton, 2003) well-being, dyadic outcomes such as intimacy and trust (e.g., Laurenceau, Barrett, & Rovine, 2005), and social contextual outcomes such as cultural stigma (Corrigan, 2005). Considered together, disclosure is a powerful behavior that can shape nearly every domain of people's lives.

However, to date, researchers have paid limited attention to the potential mediating mechanisms, or reasons why, disclosure can affect such a wide array of outcomes. Among those who have, researchers have predominantly relied on an alleviation of inhibition mechanism—the idea that disclosure can be beneficial because it allows people to express pent up emotions and thoughts. This process, borrowed from the literature on written disclosure (e.g., Lepore, 1997; Pennebaker, 1995), suggests that individuals benefit from disclosure to the extent that they can cognitively or affectively process previously inhibited information. While this process has been demonstrated to apply in the context of verbal disclosure, it cannot explain the full range of effects caused by interpersonal forms of disclosure. Thus, further theorizing is needed to fully elucidate the mediating mechanisms whereby verbal disclosure can affect well-being.

DISCLOSURE PROCESSES MODEL

In light of these existing limitations, the goal of the current article is to outline a process model that addresses these two primary questions: when and why is disclosure beneficial? The disclosure literature is immense in both its scope and diversity of approach. Previous researchers have offered reviews regarding the disclosure decision-making process (Greene et al., 2006; Omarzu, 2000), the role of self-disclosure in the development of intimacy and close relationships (Reis & Shaver, 1988; Reis & Patrick, 1996), consequences of revealing personal secrets (Kelly & McKillop, 1996) and written disclosure (Pennebaker, 1997; Smyth, 1998), and the ways in which disclosure is implicated in management of concealable stigmatized identities in workplace domains (Clair et al., 2005; Ragins, 2008). In the current paper, we review evidence examining the disclosure decision-making and outcome processes among people living with a wide range of concealable stigmatized identities.

To do so, we draw on the available disclosure literature which spans a number of specific concealable stigmatized identities, including abortion (Major et al., 1990; Major & Gramzow, 1999), childhood sexual abuse (Lamb & Edgar-Smith, 1994; Ullman, 1996), epilepsy (Tröster, 1998), HIV/AIDS (e.g., Derlega et al., 2004; Zea, Reisen, Poppen, Bianchi, & Echeverry, 2007), mental illness (Corrigan, 2005; Garcia & Crocker, 2008), sexual assault (Ahrens, Campbell, Ternier-Thames, Wasco, & Sefl, 2007; Ahrens, 2006; Ullman, 1996), and sexual orientation (e.g., Day & Schoenrade, 1997; Ragins, Singh, & Cornwell, 2007; Strachan, Bennett, Russo, & Roy-Byrne, 2007). We acknowledge at the outset that these varying types of identities differ tremendously in their cause, course, and implications for people's well-being. However, the DPM focuses on how these individual types of identities share commonalities in the processes that underlie disclosure decisions and outcomes. In some portions of this review, we also address the gaps in the extant literature by drawing on research examining general disclosure processes (e.g., Altman & Taylor, 1973; Reis & Shaver, 1988). We do so in order to provide a thorough analysis of the entire disclosure process. Importantly, we focus on identifying how these diverse literatures each contribute to and can be integrated within the broad conceptual framework outlined by the DPM.

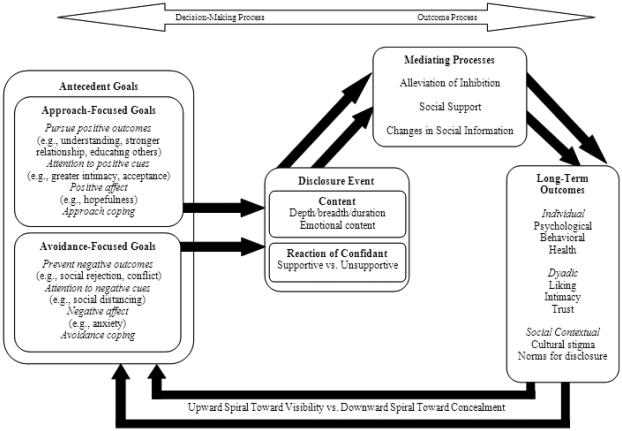

Ultimately, the Disclosure Processes Model advances current disclosure theorizing in three important ways. First, the DPM posits that disclosure must be conceptualized and studied as a single process that necessarily involves decision-making and outcome processes. The DPM (see Figure 1) highlights the impact of five main components to this process—antecedent goals, the disclosure event itself, mediating processes, outcomes, and a feedback loop. While prior frameworks have included some combination of these components, none have elucidated the mediating mechanisms involved in disclosure. For example, Omarzu (2000) focuses solely on the decision-making process, suggesting that disclosers' subjective perceptions of the utility vs. risk of a given disclosure situation determines how they communicate about the information—the depth, breadth, and duration of the communication. Unlike Omarzu (2000), Ragins (2008), Clair et al. (2005), and Greene et al. (2006) provide frameworks to account for both the decision-making and outcome processes, but they provide no theorizing about the interrelations among the successive parts of the disclosure process or why disclosure may yield beneficial outcomes. Overall, while these prior accounts offer important organizational frameworks that aid in understanding the factors involved in the disclosure process, none offer causal predictions about how these factors are interrelated.

Figure 1.

Second, the DPM posits that approach vs. avoidance motivations underlie disclosure behavior and articulates how these motivations can shape each successive stage of the disclosure process. The DPM suggests that a consideration of approach vs. avoidance goals provides a parsimonious framework to consider when disclosure will be beneficial. Specifically, we draw on insights from the long line of literature examining motivations, goal-pursuit, and self-regulation (e.g., Carver, 2006; Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996; Gable, Reis, & Elliot, 2000) to examine how disclosure goals can shape self-regulatory efforts during the full disclosure process and identify conditions under which disclosure is likely to be beneficial.

Third, the DPM posits that the relationship between disclosure and a wide range of outcomes is a multiply mediated process. Specifically, disclosure can affect individual, dyadic, and social contextual outcomes through three types of mediating processes (see Table 1): (1) alleviation of inhibition, (2) social support, and (3) changes in social information. As research in the domain of written disclosure first suggested, disclosure is a powerful way to alleviate the negative psychological and physiological effects of suppression (e.g., Cole, Kemeny, Taylor, & Visscher, 1996; Pennebaker, Hughes, & O'Heeron, 1987). However, when individuals choose to take this information from the protected confines of their personal writings to their social contexts, disclosure shifts from an individual to a social process. While the alleviation of inhibition mechanism may explain the effects of written disclosure, we argue that it is not sufficient to account for the full range of effects of interpersonal disclosure.

Table 1.

Mediating processes of disclosure

| Disclosure Mediating Process | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alleviation of inhibition | Social support | Changes in social information | |

| Type of process | Individual | Social | Social |

| Description of process | Disclosure allows people to express personally relevant, previously suppressed information. |

Disclosure allows people to garner social support or social rejection. |

Disclosure adds new information about a concealable stigmatized identity to the shared information between individuals and the broader social context and can, therefore, impact subsequent social interactions. |

| Long-term outcomes potentially affected |

Individual: Psychological Well-being (e.g., distress, intrusive thoughts) and Health Well-being (e.g., general functioning, illness progression) | Individual: Psychological Well-being (e.g., distress, job satisfaction), Behavior (e.g., task performance), Health Well-being (e.g., illness progression) | Individual: Behavior (e.g., behaviors that may “out” the discloser) |

| Dyadic: Liking, Intimacy, Trust | Dyadic: Behavior (e.g., sexual risk) | ||

| Social contextual: Cultural stigma, Norms for disclosure | |||

| Effect of approach disclosure goals |

None. | Individuals with greater approach goals may be able to garner more positive confidant responses, be more likely to attend to positive cues in the event, and be able to find benefits of disclosure even in the face of negative confidant responses. |

None. |

| Effect of avoidance disclosure goals |

Individuals with greater avoidance goals may benefit more. |

Individuals with greater avoidance goals may be less adept at garnering positive confidant responses, be more likely to attend to negative cues in the event, and may focus on the potential to be rejected after the event. |

None. |

The DPM indicates that when individuals disclose information about their concealable stigmatized identities to other people, disclosure affects people's lives through two additional mechanisms. The first is social support, the notion that interpersonal disclosure renders individuals vulnerable to social evaluation that can either result in greater social support or greater stigmatization. The second is changes in social information, the notion that interpersonal disclosure fundamentally changes the nature of social interactions among disclosers, their confidants, and their broader social contexts. While the social support mechanism is contingent on the confidant's evaluative reaction, the changes in social information mechanism is not. That is, whether confidants accept or reject disclosers because of their identity, information about the identity is now out “in the open” and can shape perceptions and behavior in both the immediate and broader social context.

In effect, the DPM suggests that disclosure affects outcomes via mediated-moderation (Edwards & Lambert, 2007; Muller, Judd, & Yzerbyt, 2005). Approach vs. avoidance goals for disclosure moderate the effect of disclosure on outcomes. That is, goals determine the magnitude of the effect of disclosure on well-being. This moderated effect is mediated through three potential processes: (1) alleviation of inhibition, (2) social support, and (3) changes in social information. These mediating processes operate simultaneously, and they explain why the moderated outcomes of disclosure occur. In contrast, the mediating process that enables disclosure to affect outcomes does not differ depending on whether disclosers adopt approach or avoidance goals (i.e., moderated mediation; Edwards & Lambert, 2007; Muller et al., 2005). All mediating processes can affect disclosure outcomes regardless of whether disclosers adopt approach vs. avoidance goals.

Defining Disclosure

Disclosure is a term whose meaning has varied considerably in prior work. Jourard (1971) offers one of the earliest definitions of self-disclosure as the “act of making yourself manifest, showing yourself so others can perceive you” (pp. 19). This definition encompasses all of the verbal or nonverbal ways in which people can express self-relevant aspects of themselves to others, a concept that relationship researchers have often referred to as “self-expression” (for a review, see Reis & Patrick, 1996). Like Derlega and colleagues (1993), however, we use the term “disclosure” to refer only to verbal, interpersonal expressions of self-relevant information, or as they write, “what individuals verbally reveal about themselves to others (including thoughts, feelings, and experiences)” (pp.1). In the current review, our analysis focuses on one important type of self-relevant information that can be verbally expressed—possession of a concealable stigmatized identity. Thus, we use the term “disclosure” within the DPM framework to refer to situations in which a discloser verbally reveals information to a confidant about the discloser's concealable stigmatized identity, information that was not previously known by the confidant.

Components of the DPM

The DPM (Figure 1) posits that disclosure must be conceptualized and studied as a single dynamic process that necessarily involves both antecedents and outcomes and is composed of a decision-making process and an outcome process. Like many theorists (Dindia, 1998; Reis & Shaver, 1988), the DPM views disclosure as an ongoing process. People who live with a concealable stigmatized identity repeatedly deal with issues of disclosure (and nondisclosure) over the course of a lifetime. Thus, the processes depicted in the DPM represent the workings of just one episode that is situated within many in this ongoing disclosure process.

Antecedent Goals

The model specifies that disclosure begins with a decision-making process in which disclosure goals affect the likelihood of disclosure in a given situation. Disclosure has long been theorized to be a goal-directed behavior in which individuals may have a wide range of goals such as self-expression and enhancing intimacy in important personal relationships (Derlega & Grzelak, 1979; Omarzu, 2000). While these previous accounts provide a description of the types of goals that may guide disclosure decisions, they do not attend to the possibility that these goals may also affect what happens “downstream” in the disclosure process—how the disclosure events unfold and how disclosure ultimately affects important outcomes.

Here, we outline evidence suggesting that an approach vs. avoidance goal framework provides important new insights into the full disclosure process—how people make decisions to disclose, communicate, are affected by disclosure, and repeat this process. Specifically, by positing that two separate motivational systems underlie the overall disclosure process, we suggest that understanding the disclosure goals, or reasons, that lead people to disclose is a critical part of understanding when disclosure will be beneficial.

Disclosure Event

Once people make the decision to disclose, they then describe information about the concealable stigmatized identity to their chosen confidant. For many people, this disclosure event will be a one-time situation wherein disclosers talk about their concealable stigmatized identity with the confidant and clearly convey that they possess the identity. For others, however, the disclosure event may unfold over a longer period of time. That is, some people may choose to “test the waters” with their confidant by first introducing the topic in a roundabout way and then come back to the topic later after determining whether the confidant is likely to react positively or negatively (Greene, Derlega, Yep, & Petronio, 2003; Limandri, 1989; Serovich, Oliver, Smith, & Mason, 2005). Regardless of which approach is used, we define a disclosure event as the verbal communication that occurs between a discloser and a confidant regarding the discloser's possession of a concealable stigmatized identity. The culmination of this event occurs when both individuals have reached a consensus about this information—the discloser knows that the confidant is now fully aware of the existence of this previously concealed identity, and the confidant understands that the discloser possesses the identity and has reacted in a supportive or unsupportive manner.

The DPM focuses on attributes of the communication that are shared during the disclosure event, including depth, breadth, duration, and emotional content, and the reaction of the confidant. We also consider how disclosure goals shape both the content of the disclosure event and the reaction of the confidant.

Mediating Processes and Outcomes

How does this disclosure event then impact outcomes? The DPM specifies that disclosure can yield a number of different types of consequences, including those that occur at an individual, dyadic, and social contextual level (see Figure 1). Importantly, however, the DPM specifies that there are multiple potential mediating processes that allow disclosure to affect these outcomes: (1) alleviation of inhibition, (2) social support, and (3) changes in social information. By specifying that there are multiple, simultaneous potential mediating processes, the DPM provides a conceptual framework that may help clarify the conditions under which disclosure will yield beneficial outcomes, and which types of outcomes will be relevant in a given disclosure situation.

Feedback Loop

Finally, in support of our position that disclosure is a dynamic process, the DPM suggests that the disclosure process does not necessarily end with the outcomes of specific disclosure events. Instead, the DPM specifies that the outcomes of a single disclosure event can affect subsequent disclosure processes through a feedback loop (Clair et al., 2005; Greene et al., 2006). Because disclosure is part of an on-going process (Dindia, 1998; Reis & Shaver, 1988), single disclosure events are components of a larger, ongoing process of “stigma management”—coping with the psychological and social consequences of their identity (Goffman, 1963). With each successive disclosure, are people becoming more openly engaged in their social contexts without fear of rejection, or are they becoming more concealed, more secretive, and more concerned that they will be victims of prejudice and discrimination? Disclosure plays a critical role in affecting which of these two different trajectories people adopt in the process of stigma management.

ANTECEDENT GOALS

Disclosure goals have played a critical role in previous theories of disclosure. Derlega and Grzelak (1979) first noted that disclosure is a functional behavior—it allows disclosers to pursue a variety of personal goals, including self-expression, self-clarification, social validation, relationship development, and social control. According to this perspective, people will disclose only when they believe that disclosure is an effective or necessary tool to obtain the goal of interest (Derlega & Grzelak, 1979; Quattrone & Jones, 1978). In an elaboration of this general perspective, Omarzu (2000) suggested that activation of specific disclosure goals is the first step in the disclosure decision-making process. Once goals are activated, individuals must then consider whether disclosure is an appropriate strategy for attaining the goal, select an appropriate confidant, and evaluate the potential costs vs. benefits of disclosure. Subsequent theoretical accounts have also highlighted the role of disclosure goals—among other types of antecedent factors, such as anticipated negative reactions from the confidant and social contextual cues, in the decision-making process (Clair et al., 2005; Greene et al., 2006).

Empirical work has also highlighted the role of goals in disclosure. Derlega and colleagues (Derlega, Winstead, & Folk-Barron, 2000; Derlega & Winstead, 2001; Derlega, Winstead, Greene, Serovich, & Elwood, 2002; Derlega et al., 2004) have demonstrated that people living with HIV/AIDS report a number of different types of goals both for and against disclosure. For example, people living with HIV/AIDS often report wanting to disclose because they want to strengthen the relationship with the confidant or because they feel a moral duty to educate or inform the confidant in order to protect their health. However, these individuals also possess goals against disclosure, including the desire to keep information about the diagnosis private, avoid social rejection, and protect the confidant from feeling distressed or concerned about the diagnosis. Other work examining sexual orientation has also highlighted the strategic use of disclosure in order to obtain symbolic and tangible assistance (Cain, 1991) or to educate people about their identity (e.g., Goldberg, 2007).

Together then, these examples suggest that goals—the reasons why individuals disclose their concealable stigmatized identity to others—are important considerations in the study of disclosure. However, this previous work offers a largely descriptive account of the types of goals that individuals may possess in disclosure contexts. Some additional work has suggested that disclosure goals can affect the likelihood of disclosure (Derlega et al., 2002), but it does not specify how or why goals affect the broader disclosure process. While a number of people have suggested that these goals are a critical part of the disclosure process, no previous work has tested the possibility that goals affect the manner in which individuals communicate about their identities (as Omarzu, 2000 suggested), or the eventual outcomes of the disclosure event.

While disclosure researchers have largely omitted examination of these issues, researchers who study motivation and self-regulation have accumulated a substantial amount of evidence indicating that goals fundamentally shape behavior and its outcomes. Their research indicates that behavior is regulated by two separate motivational systems that represent approach and avoidance dimensions—motivation that is focused either on pursuing a rewarding or desired end-state, or on avoiding a punishing or undesired end-state (for reviews, see Elliot, 1999; Gable & Berkman, 2008; Higgins, 1998). Individuals who possess approach goals are focused on the possibility of positive outcomes, and their self-regulatory efforts are aimed at moving them towards possible rewards or positive states. These individuals' self-regulatory efforts orient them to reduce the discrepancy between themselves and their goal (i.e., discrepancy reducing feedback loops; Carver & Scheier, 1998; Carver, 2006). In contrast, individuals who possess avoidance goals are focused on the possibility of negative outcomes, and their self-regulatory efforts are aimed at moving them away from possible punishments or negative states. These individuals' self-regulatory efforts orient them to enlarge the discrepancy between themselves and their goal (i.e., discrepancy enlarging feedback loops; Carver & Scheier, 1998; Carver, 2006).

Importantly, these self-regulatory efforts are characterized by distinct psychological profiles. Individuals who pursue approach goals are more likely to attend to the presence of positive stimuli (Derryberry & Reed, 1994) and interpret neutral or ambiguous stimuli in a positive light (Strachman & Gable, 2006), utilize approach-focused coping strategies (Gable, Reis, & Elliot, 2003), and experience greater daily positive affect (Gable et al., 2000). In contrast, individuals who pursue avoidance goals are more likely to attend to the presence of negative stimuli (Derryberry & Reed, 1994) and interpret neutral or ambiguous stimuli in a negative light (Strachman & Gable, 2006), utilize avoidance-focused coping strategies (Gable et al., 2003), and experience greater daily negative affect (Gable et al., 2000). Thus, approach vs. avoidance goals fundamentally shape the way individuals perceive and react to their environments.

Mounting evidence indicates that avoidance goal pursuit can lead to a host of suboptimal outcomes. For example, in the achievement motivation domain, Elliot and colleagues (e.g., Church, Elliot, & Gable, 2001; Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996; Elliot & Church, 1997) have demonstrated that students who pursue avoidance goals (e.g., trying to avoid doing poorly on an exam) exhibit less task absorption and more test anxiety, tend to adopt ineffective approaches to studying, and have lower actual performance (i.e., grades) compared to students who pursue approach goals (e.g., trying to do well on an exam). In therapeutic settings, clients' pursuit of avoidance- (vs. approach) oriented goals has been shown to be related to smaller increases in subjective well-being at the end of therapy (Elliot & Church, 2002). More generally, avoidance goals can also compromise physical health; one study finds that undergraduate students who held greater avoidance goals were more likely to experience an increase in physical illness symptoms at a 3-month follow-up (Elliot & Sheldon, 1998).

Goals and social outcomes

This evidence suggests that approach vs. avoidance goals can affect outcomes in individual-based, non-social domains such as achievement and physical health. However, can these goals also lead to deleterious outcomes in dyadic or social contexts? Put differently, do goals shape outcomes even if those outcomes are also influenced by other people and their respective goals? Several lines of research suggest that goals do, indeed, affect outcomes in these contexts. In a series of studies, Gable and colleagues (Elliot, Gable, & Mapes, 2006; Gable, 2006) have demonstrated that individuals with approach (also called appetitive) goals for their social relationships fare better than individuals with avoidance (also called aversive) goals. That is, individuals who view their relationships in terms of their potential for positive outcomes such as greater intimacy and stronger social bonds experience better social outcomes than individuals who view their relationships in terms of their potential for negative outcomes such as conflict and social rejection. For example, in a longitudinal study of social motives among college students, approach motivations predicted less loneliness, greater satisfaction with social bonds, and more positive attitudes toward social bonds at a 6-week follow-up, whereas avoidance motivations predicted greater loneliness, less satisfaction with social bonds, and less positive attitudes toward social bonds (Gable, 2006). The benefits of approach social goals have also been demonstrated in the context of dating relationships, where approach goals can serve to buffer against decreases in sexual desire over time, even in the face of negative relationship events that may otherwise serve to lower sexual desire (Impett, Strachman, Finkel, & Gable, 2008).

Similarly, a complementary line of research suggests that positive relationship goals can affect people's ability to garner social support from their relationship partners. In this research, Crocker and colleagues (Crocker & Canevello, 2008) demonstrate that to the extent that individuals possess compassionate relationship goals—goals that focus on supporting others and being a positive influence in the relationship—they also report increased perceived closeness, trust, and social support over time. However, to the extent that individuals possess self-image relationships goals—goals that focus on protecting desired self-images even at the expense of others' well-being—they also report increased conflict and loneliness over time. Importantly, their research suggests that these goals shape the supportive behavior being given and received within the relationship, not simply perceptions of support. In a dyadic study of college roommates, to the extent individuals possessed compassionate, but not self-image, goals, they were more likely to give social support to their roommates, and they were more likely to receive social support from their roommates in return 3 weeks later (Crocker & Canevello, 2008). Thus, this evidence suggests that an individual's goals can affect both their own behavior and that of their relationship partner.

Further, several studies suggest that this general pattern of findings may also extend to the context of disclosure. In a daily diary study of people concealing a history of depression or sexual orientation, researchers found that those with compassionate (or eco-system) disclosure goals demonstrated greater rates of disclosure and greater psychological benefits (i.e., less depression, anxiety) compared to people who disclosed with self-image goals (Garcia & Crocker, 2008). Similarly, in a sample of people with a variety of concealable stigmatized identities, individuals who reported compassionate (or eco-system) goals for their first disclosure also reported more positive reactions from the confidant which, in turn, was related to greater current psychological well-being (Chaudoir & Quinn, in press). Further, among individuals concealing a history of childhood sexual abuse, disclosers were most likely to report receiving positive reactions from confidants when they were motivated to disclose in order gain social support or intimacy with the confidant (Lamb & Edgar-Smith, 1994).

Together, these findings provide initial evidence to suggest that antecedent disclosure goals—the reasons that lead individuals to disclose their concealable stigmatized identity to others—may play an important role in determining when disclosure may be beneficial. To the extent that people disclose for approach- (or compassionate) focused goals rather than avoidance- (or self-image) focused goals, they may be better able to garner positive social responses from their confidants.

Disclosure Event

We suggest that antecedent goals may play a large role in shaping the complex self-regulatory processes involved in the disclosure event itself and the long-term outcomes of disclosure. Specifically, individuals with approach-focused disclosure goals may be better adept at communicating information about their identity and, in turn, garnering a positive, supportive reaction from their confidants. Further, individuals with approach-focused disclosure goals may be more likely to attend to positive cues within the interaction and conclude that the confidant and the event itself was supportive.

Characteristics of the disclosure event

Previous scholars have identified depth, breadth, and duration as critical aspects of the disclosure event itself (Altman & Taylor, 1973; Cozby, 1973; Omarzu, 2000). Depth refers to the degree to which information shared through disclosure is deemed to be highly private or intimate. While information about a concealable stigmatized identity is likely to be fairly high in intimacy or depth by its very nature, some identities may be more likely to be perceived as an important and private piece of information about the discloser than others. Breadth refers to the sheer amount or different array of topics covered during a disclosure event. In the context of disclosure of a concealable stigmatized identity, disclosers may vary in the extent to which they describe a number of different aspects of the identity. Duration refers to the time that an individual spends talking about information regarding the concealable stigmatized identity. Some people may talk at great length about their identity while others may only briefly talk about this information.

In addition to these dimensions, disclosure events may also vary in how much the discloser expresses emotions (Reis & Shaver, 1988). During disclosure events, disclosers may talk about the emotions associated with various aspects of the identity or may only talk about the factual information about these aspects. For instance, across two different disclosure events, a person may choose to disclose their HIV-positive status by talking about both their daily experiences of living with HIV/AIDS and how they contracted the virus. In one disclosure event, the discloser may simply convey the facts about these topics—“I am taking multiple medications to treat my HIV infection,” “I am in poor health,” and “ I contracted HIV through unprotected sex”—or the discloser may emphasize the emotions associated with these topics—“I am frustrated by all the medications I have to take to treat my HIV infection,” “I fear that I'm going to die young,” and “I really regret not using a condom.” Thus, while disclosers may share information that is of equal depth, breadth, and duration, they may vary in the extent to which they rely on emotions such as anger, sadness, happiness, optimism, or regret to convey this information.

In sum, depth, breadth, duration, and the emotional content are each important dimensions by which disclosure events may vary. Although we have discussed each of these dimensions separately, they do co-occur in these events and are not, therefore, mutually exclusive of one another.

Confidant reaction

There is some evidence to suggest that the content of the disclosure event—it's overall depth, breadth, duration, and emotional content—can impact the reaction of the confidant. For example, meta-analytic evidence suggests that higher depth of self-disclosure leads to stronger liking for the discloser, while breadth alone does not relate strongly to liking (Collins & Miller, 1994). Other theoretical and empirical analyses suggest that the disclosure-liking effect may vary across relationship and situational contexts. That is, disclosing highly intimate information too early in the development of a relationship may not necessarily enhance liking (Altman & Taylor, 1973) and may be perceived as a negative or inappropriate behavior by strangers (for reviews, see Collins & Miller, 1994; Cozby, 1973)

Further, both theoretical and empirical examinations suggest that disclosures are more likely to elicit intimacy when they contain affective content as opposed to merely factual content. That is, Reis and Shaver (1988) suggest that disclosure is a fundamental building block of relational intimacy, but that emotional disclosures are more likely to create intimacy compared to factual disclosures because they are perceived to convey more private and central aspects of the discloser. In an empirical test of this idea, researchers have demonstrated that self-disclosure of emotion is, in fact, a strong predictor of intimacy between social interaction partners, but self-disclosure of facts is not related to intimacy (Laurenceau, Barrett, & Pietromonaco, 1998). While this evidence only examines relationship intimacy as an outcome of disclosure, it does suggest that emotion-based disclosures may be a more effective in communicating personal information and may possibly be viewed in a more positive way by confidants compared to fact-based disclosures.

The expression of emotion within the context of a disclosure event can also serve a number of functions within the interaction that can ultimately impact the likelihood that the confidant will react favorably. At a basic level, emotions serve to express personal needs or goals (Frijda, 1993) and may, therefore, be beneficial to the extent that they help the discloser effectively convey those needs and potentially elicit desired (i.e., helpful, supportive) responses from confidants. While expressing emotions may aid the quality of the overall disclosure event, there is also evidence that actively suppressing emotional content can impede these events. That is, intentional suppression of emotions can derail the quality of social interactions and decrease liking for those who purposefully stifle their emotions (Butler et al., 2003).

Given the transactional nature of the disclosure event, it also possible that positive confidant reactions during the event can, in turn, prompt the discloser to talk more and discuss increasingly intimate information (Taylor, Altman, & Sorrentino, 1969; Taylor & Altman, 1975). As Omarzu (2000) posits in her model of disclosure decision-making, people will disclose information that is greater in depth or intimacy when they perceive that the subjective risk of doing so—the extent to which they anticipate negative reactions from the confidant—is low. Thus, to the extent that disclosers detect that their confidants may be reacting positively to information about their identities, these responses may shape the ways in which disclosers talk about their identities within the disclosure event.

Goals and the disclosure event

Because they are focused on avoiding the possibility of social rejection and conflict, individuals with avoidance-focused goals may simply be less likely to have disclosure events—they may simply choose not to disclose frequently. Fears of rejection and anticipated stigma are some of the most commonly cited reasons for nondisclosure across a wide variety of types of identities (Ahrens, 2006; Black & Shandor, 2002; Chandra, Deepthivarma, Jairam, & Thomas, 2003; Clark, Lindner, Armistead, & Austin, 2003; Duru et al., 2006; Herek, 2009; Herrschaft & Mills, 2002; Simoni et al., 1995). Further, our recent work demonstrates that individuals who report greater activation of avoidance-related motivations are consistently less likely to disclose (Chaudoir, 2009). We conducted a longitudinal survey of over two hundred people living with HIV/AIDS in various parts of the U.S. During both a baseline and 6-month follow-up survey, participants were asked to recall their most recent disclosure experience, evaluate how positive and supportive the event was (i.e., disclosure positivity), and rate the antecedent factors they considered in making their most recent disclosure decision. Results from this study demonstrate that participants who reported greater avoidance-related disclosure goals (e.g., concerns about social rejection) and hyperaccessibility of thoughts about HIV in their most recent disclosure decision were consistently less likely to disclose at both time points.

In addition to having fewer disclosure events, individuals with avoidance-focused disclosure goals may have more difficulty when they do decide to disclose. Disclosing information about a concealable stigmatized identity is not an easy task. Disclosers must find the appropriate time and place to share this sensitive information, and they must come up with the words to be able to effectively communicate this information to their confidants. They must find the delicate balance between revealing enough information so that confidants understand them, but not too much information that the confidant feels uncomfortable (for a review, see Cozby, 1973). As we have reviewed, the ways in which individuals communicate about their identities can play an important role in eliciting positive, supportive reactions from confidants.

Individuals who adopt approach-focused disclosure goals may simply be better adept at self-regulating during the disclosure event. Approach-focused goals focus on moving the discloser towards a given target or endpoint (e.g., strengthening a relationship, being honest) while avoidance-focused goals focus on moving the discloser away from a given target or endpoint (e.g., avoiding conflict, preventing a relationship break-up). Approach-focused goals are, therefore, more “directive” than avoidance-focused goals—they allow people to identify when they have reduced the discrepancy between their current state and their goal, and they have a clear endpoint (Carver & Scheier, 1998; Carver, 2006). In contrast, because avoidance-focused goals are aimed at increasing the discrepancy between the current state and an “anti-goal” (i.e., a state that individuals want to avoid), they provide no definitive endpoint. In effect, approach-focused disclosure goals may simply provide disclosers with a more effective “roadmap” or self-regulatory strategy for how to achieve the outcomes they want. Consequently, individuals with approach-focused disclosure goals may be more skilled at delicately balancing the depth, duration, breadth, and emotional content of their messages.

Individuals with avoidance-focused goals for disclosure may have some degree of awareness of these inabilities, given that these types of goals are also associated with greater perceived communication difficulties and lower disclosure self-efficacy (Chaudoir, 2009). Their discomfort with interpersonal, verbal disclosure of their identity may lead individuals with avoidance-focused disclosure goals to seek out other venues for disclosure that they believe will minimize the psychological hurt caused by social rejection. For example, these individuals may choose a less direct method of communicating information about their identity such as email. Because people can say things over email that they may not have the “guts” to do in person, disclosers who are focused on avoiding negative social reactions may be more likely to use this communication tool for their disclosures. Unfortunately, disclosures that occur via email do not benefit from the give-and-take that occurs in an interpersonal, verbal interaction—the opportunity for interaction partners to ask questions of one another, clarify confusion, and emotionally connect with each other. As many researchers have shown, email methods of communication increase the opportunity for information to be misconstrued, and elicit unintended (and often, negative) reactions from the confidant (Kruger, Epley, Parker, & Ng, 2005; Walther, Loh, & Granka, 2005). Thus, even though other venues for disclosure may appear to offer greater protection from social rejection, they may inadvertently increase the chances that disclosure will be perceived negatively by confidants.

Further, goals may shape the nature of the language individuals use to convey information about their identity (Douglas & Sutton, 2003). Because individuals with approach goals for disclosure are focused on the possibility for social support and intimacy rather than social rejection and conflict, they may choose to communicate information about their identity by using more positively valenced language or direct (vs. indirect) communication strategies (Overall, Fletcher, Simpson, & Sibley, 2009), and they may use phrases that emphasize the closeness of the relationship (e.g., “we,” “us” vs. “I” or “you”; for a review, see Heyman, 2001). Even if individuals who possess avoidance goals are able to mask their worries and use positively valenced language, they will not likely be successful at controlling their nonverbal cues such as eye contact and posture (DePaulo & Friedman, 1998; Ekman & Friesen, 1974). As evidence from the domain of intergroup relations suggests, even when individuals are able to override their thoughts and feelings to communicate a positive message, confidants are still able to detect their “true” thoughts and feelings via nonverbal cues (Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner, 2002).

Disclosers with approach-focused goals may also be more likely to benefit from disclosure because they are simply more attuned to the presence of supportive confidant reactions than disclosers with avoidance goals. As we described earlier, approach and avoidance goals fundamentally shape the types of stimuli that individuals are likely to perceive in their environments (Derryberry & Reed, 1994; Strachman & Gable, 2006). That is, in ambiguous environments, individuals with approach goals are more likely to attend to positive stimuli while individuals with avoidance goals are more likely to attend to negative stimuli (Strachman & Gable, 2006). Thus, disclosers with approach goals are more likely to be attuned to cues that suggest that the confidant is understanding and supporting them than to be attuned to cues that suggest the confidant is rejecting them. In contrast, disclosers who expect to receive social rejection may be more attuned to these negative, rejecting cues (Kaiser, Vick, & Major, 2006).

In sum, understanding the nature of the goals that lead individuals to disclose their concealable stigmatized identity may be an important first step in understanding when disclosure may be beneficial. While previous theorizing and research has typically emphasized the importance of the confidant response in determining the outcomes of disclosure (Kelly & McKillop, 1996; Lepore et al., 2000; Major & Gramzow, 1999; Rodriguez & Kelly, 2006), our perspective highlights the influence of disclosers' goals on multiple aspects of the disclosure process, including the ability to elicit positive confidant responses. As we discuss later, an emphasis on the goals that disclosers bring to disclosure situations may have practical benefits for researchers and practitioners who prepare individuals living with concealable stigmatized identities to disclose.

DISCLOSURE MEDIATING PROCESSES AND OUTCOMES

Why might disclosure be beneficial? As noted at the outset, disclosure is one of the most important aspects of living with a concealable stigmatized identity because the decision to tell another person about this information can impact nearly every domain of a person's life and well-being. The DPM attends to the individual, dyadic, and social contextual outcomes of disclosure. We suggest that this wide array of outcomes cannot be explained with only one mediating process—the potential for disclosure to alleviate the negative effects of inhibition. That is, our analysis suggests that to fully understand the ways in which disclosure impacts these outcomes, researchers must attend to the possibility that multiple types of mediating processes can enable disclosure to affect people's outcomes.

Individual, Dyadic, and Social Contextual Outcomes

Across the diverse literatures included in this review, researchers have measured a wide variety of types of individual outcomes of disclosure, including psychological, behavioral, and health effects. Researchers have frequently examined the potential psychological impact of disclosure on outcomes such as distress (e.g.,Broman-Fulks et al., 2007; Greenberg & Stone, 1992; Hays, McKusick, Pollack, & Hilliard, 1993; Jonzon & Lindblad, 2005; Kalichman & Nachimson, 1999; Major & Gramzow, 1999; Ruggiero, 2004; Ullrich et al., 2003), social support (e.g.,Kalichman, DiMarco, Austin, Luke, & Difonzo, 2003; Zea et al., 2005), self-esteem (e.g., Afifi & Caughlin, 2006; Ullrich et al., 2003; Zea et al., 2005), intrusive thoughts about the identity (e.g., Major & Gramzow, 1999), and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms (e.g., Broman-Fulks et al., 2007; Ruggiero, 2004; Ullman & Filipas, 2001).

Many researchers, especially those who study disclosure of HIV-positive status, have also examined how disclosure can impact behavioral outcomes such as safer sex practices with sexual partners (for a review, see Simoni & Pantalone, 2005) and adherence to antiretroviral medications (e.g., Stirrat et al., 2006; Waddell & Messeri, 2006). Finally, a number of studies have demonstrated that disclosure of a concealable stigmatized identity can have a beneficial impact on general health well-being (e.g., Greenberg & Stone, 1992; Jonzon & Lindblad, 2005) as well as illness-specific indices of health functioning (e.g., CD4 counts or viral load among people living with HIV/AIDS; Cole, Kemeny, Taylor, Visscher, & Fahey, 1996; Ullrich et al., 2003).

Despite the fact that disclosure is an inherently dyadic exchange that can have implications for both the discloser and confidant and their relationship with each other, no work known to us has examined dyadic outcomes such as intimacy in the context of concealable stigmatized identities. However, related work examining the impact of general self-disclosure in the context of personal relationships indicates that disclosure can increase various indices of rapport. At a basic level, disclosure is a highly reciprocal process wherein one person's disclosure can engender disclosure from another (Cozby, 1973; Jourard, 1971), and the mutual sharing of information can lead to increased liking within the dyad (Berg & Wright-Buckley, 1988; Collins & Miller, 1994; Miller, 1990). Several studies demonstrate that disclosure can create increased relationship intimacy to the extent that confidants are perceived to be responsive to the information (e.g., Laurenceau et al., 1998; Laurenceau et al., 2005; Manne et al., 2004). Self-disclosure has also been shown to be the critical mediating process in the development of intergroup trust in the context of interracial interactions (Turner, Hewstone, & Voci, 2007). In sum, there is ample evidence to suggest that disclosure can potentially yield interpersonal liking, intimacy, and trust within the context of dyadic personal relationships. As many theorists have noted, these dyadic outcomes are also relevant in the context of disclosure of a concealable stigmatized identity, although no known empirical work has examined these issues directly.

Finally, disclosure can also impact social contextual level outcomes. While an individual disclosure event may be just one of many disclosure-related experiences that occur within the context of an individual's life or an ongoing dyadic relationship, each of these instances is also nested within a specific social and cultural context that can be affected by these individual events. That is, every time individuals disclose their history of mental illness, HIV-positive status, or sexual orientation, their individual disclosure can help to create awareness about their identity, potentially reduce the stigma associated with it, and can help to make disclosure and openness normative in a given community.

In fact, a number of theorists have noted how individual disclosures can either directly or indirectly impact societal level outcomes. As Cain describes in his analysis of disclosure of sexual orientation, people often make what he terms “political disclosures”—disclosures that are aimed at “making homosexuality more visible, thereby challenging the misconceptions that engender ongoing oppression” (pp. 69; Cain, 1991). People with concealable stigmatized identities may also view disclosure as a way to “reclaim” the stigmatized label for use by one's group (e.g., “We're here. We're Queer. Get used to it.”) and reduce the negative connotations associated with it (for a discussion, see Corrigan, 2005). In the context of motivations for disclosure of HIV, many people living with HIV/AIDS report that they disclose because they want to educate others about the virus and dispel common myths about the illness (Derlega et al., 2004; Greene et al., 2003). In fact, in the context of HIV, researchers have demonstrated that a single disclosure—Magic Johnson's public announcement of his HIV infection—single-handedly increased concern about HIV/AIDS and engaged a broader society in a dialogue about the issue in a way that perhaps no other stigma-reduction strategy has since (Kalichman & Hunter, 1992). Thus, whether on a small or large scale, individual disclosure events can serve to impact broader social contextual outcomes.

Mediating Processes

Given these various types of consequences, how is it the case that disclosure can affect such wide-ranging outcomes? To date, the majority of disclosure research has relied solely on one type of mechanism to explain why disclosure can affect people's outcomes. Researchers have almost exclusively focused on the ability of disclosure to alleviate the psychological and physiological stress caused by inhibition (Frattaroli, 2006; Major & Gramzow, 1999; Pennebaker et al., 1987; Smyth, 1998) and have paid relatively little attention to other potential reasons why disclosure impacts people's outcomes (for an exception, see Beals, Peplau, & Gable, 2009). Given that disclosure has been demonstrated to affect such a wide array of outcomes (for reviews, see Clair et al., 2005; Derlega et al., 1993; Kelly & McKillop, 1996; Ragins, 2008), it is unlikely the case that all of these can be attributed to the fact that it can alleviate the psychological and physiological distress caused by inhibition. In effect, we suggest that this one mediating process cannot account for such a wide array of outcomes and that additional mediating processes are needed in order to fully understand how disclosure can impact people's outcomes.

We propose that disclosure can elicit these various types of outcomes through three broad types of mediating processes: alleviation of inhibition, social support, and changes in social information (see Table 1). First, as much research has already demonstrated, disclosure can be a powerful tool to alleviate the individual psychological and physiological stress caused by active concealment (i.e., alleviation of inhibition; Cole et al., 1996; Major & Gramzow, 1999; Pennebaker, 1997; Pennebaker & O'Heeron, 1984). Thus, disclosure can impact psychological and health well-being to the extent that it allows people to express previously suppressed thoughts and feelings. Second, disclosure is a behavior that allows people to garner social support (e.g., Beals et al., 2009; Smith, Rossetto, & Peterson, 2008). Thus, to the extent that individuals are socially supported instead of socially rejected through disclosure, they may derive individual psychological and dyadic relationship benefits from disclosure. Finally, disclosure also introduces new information about an individual that can impact the greater social context and the way that people interact with each other. Thus, disclosure can change the way that people perceive and interact with the discloser and how the discloser perceives and interacts with their disclosure confidants, thereby affecting individual, dyadic, and social contextual outcomes.

Alleviation of Inhibition

The process of passing as a nonstigmatized person or actively hiding a concealable stigmatized identity from others (Alonzo & Reynolds, 1995; Goffman, 1963; Siegel, Lune, & Meyer, 1998) can be psychologically and physiologically taxing. In order to manage their social encounters without revealing information about the concealable stigmatized identity, people often pay more attention to their interaction partners and their social environment (Frable, Blackstone, & Scherbaum, 1990). Further, intentional efforts to suppress information about one's concealable stigmatized identity can actually lead people to become preoccupied with thoughts about their identity (Smart & Wegner, 1999). Thus, efforts to “pass” as a nonstigmatized individual or suppress thoughts about the identity can create an additional cognitive load for people living with a concealable stigmatized identity.

Research suggests that concealing important or emotionally-laden information about oneself can take a toll on both psychological and health functioning (Pennebaker, 1997; Pennebaker, Barger, & Tiebout, 1989). A large body of research supports the idea that repeated written disclosure can improve long-term health well-being (for reviews, see Pennebaker, 1997; Pennebaker, Kiecolt Glaser, & Glaser, 1988; Pennebaker, 1995), and meta-analyses of these studies demonstrate that written emotional expression is related to improved psychological well-being (e.g., less negative affect, fewer cognitive intrusions), self-reported health (e.g., decreased number of health center visits), and improved physiological functioning (e.g., lower blood pressure, lower cholesterol) among both college and clinical samples (Frisina, Borod, & Lepore, 2004; Smyth, 1998). For example, people living with HIV who engaged in emotional writing for 4 days experienced better immune functioning (i.e., higher CD4 cell counts) during a 6-month follow-up period (Petrie, Fontanilla, Thomas, Booth, & Pennebaker, 2004).

The psychological and health benefits of verbal disclosure have also received a degree of empirical support. In some of Pennebaker's earliest work, he demonstrated that there is an inverse relationship between talking about a spouse's death and self-reported health problems (Pennebaker & O'Heeron, 1984). That is, people who talked about their spouse's death with close friends reported fewer illness symptoms (e.g., headaches, ulcers) in the year after the death. In a different study, undergraduate participants who spoke into a tape recorder about a stressful life experience that they had rarely disclosed demonstrated improved immune system functioning for 4 weeks after the intervention (Esterling, Antoni, Fletcher, Margulies, & Schneiderman, 1994). Other research finds that children who disclosed their HIV-status to at least one friend demonstrated larger increases in immune functioning (i.e., CD4 cell counts) at a 1-year follow-up than did children who did not disclose (Sherman, Bonanno, Wiener, & Battles, 2000). Researchers have also found that consistent disclosure of HIV-status or sexual orientation predicted increased CD4 count over time compared to consistent concealment of HIV-status or sexual orientation (Strachan et al., 2007). Other researchers have demonstrated that HIV infection advances more rapidly and is related to greater depression among gay men who conceal their sexual orientation (Cole et al., 1996; Cole et al., 1996; Ullrich et al., 2003). Overall then, research largely supports the idea that actively hiding concealable stigmatized identities such as HIV-positive status can lead to deteriorations in psychological well-being (e.g., intrusive thoughts about the identity, psychological distress) and global and illness-specific health functioning, and that verbal disclosure can have favorable affects. Thus, disclosure can potentially improve these individual-level outcomes.

Effect of antecedent goals on alleviation of inhibition

Considered within the broader DPM framework, when might individuals be most likely to benefit from disclosure's ability to alleviate the negative effects of inhibition? Our analysis predicts that individuals with avoidance-focused motivations may be most likely to benefit from disclosure's ability to alleviate the negative effects of inhibition.

The effectiveness of the written disclosure paradigm is contingent upon the fact that individuals write repeatedly about life events that are highly personal, emotional, and potentially traumatic—a process that allows them to affectively or cognitively process this information— which in turn alleviates the negative effects of inhibition (Pennebaker, 1997). In extending this logic to the domain of interpersonal disclosure, it would appear that a concealable stigmatized identity would have to create some degree of personal distress before the disclosure event in order for disclosure to benefit the discloser, a conclusion that Kelly and McKillop (1996) also draw from their review of verbal disclosure of personal secrets. Put differently, disclosure cannot alleviate the negative consequences of concealment if there are no negative consequences (e.g., distress, intrusive thoughts) to alleviate.

Who are these individuals who are likely to be struggling with the negative consequences of concealment? We suggest that they are individuals who also possess avoidance-focused goals for disclosure. Individuals who possess avoidance-focused goals for a discrete disclosure event may also experience chronic activation of the avoidance motivational system (Carver & White, 1994; Gable & Strachman, 2008). Individuals with chronically activated avoidance systems are likely to be more sensitive to the possibility for social rejection in their daily lives. When thoughts about their identities are made salient, these individuals may be more likely to actively conceal this information from others—they may be less likely to view disclosure as a possible outlet to express their thoughts and feelings. Instead, these individuals are likely to adopt avoidant coping strategies to deal with information about their identity (Gable et al., 2000), including suppressing the information. Given that intentional efforts to suppress this information will result in hyperaccessibility of thoughts related to the identity (Smart & Wegner, 1999), these individuals may be faced with frequent intrusive thoughts and heightened psychological distress.

Thus, according to our theorizing, individuals with avoidance disclosure goals may actually be most likely to benefit from disclosure through the alleviation of inhibition mechanism because they may be most burdened by the effects of concealment. This idea has received some support in the literature. In a 2-year longitudinal study, women with a history of abortion only benefited from emotional interpersonal disclosures if they experienced intrusive thoughts about their abortion (Major & Gramzow, 1999). That is, only women who experienced some degree of difficulty coping with their abortion demonstrated psychological benefits of interpersonal disclosure. Further, there is some evidence to suggest that the health benefits of disclosure only occur when the topic of the written disclosure is particularly emotionally distressing. In a variation of the traditional writing paradigm, researchers asked people who had experienced a trauma to write about that event. Results from this study demonstrate that individuals with high severity traumas reported fewer physical illness symptoms during a 2-month follow-up compared to participants who wrote about low severity traumas (Greenberg & Stone, 1992). Although these researchers did not assess pre-disclosure negative consequences of concealment (e.g., distress, intrusive thoughts), one plausible interpretation of their results is that only high trauma severity participants experience benefits of written disclosure because they were also the most likely to experience distress about the trauma prior to the disclosure event. Together, these studies suggest that interpersonal, verbal disclosure may alleviate the negative effects of concealment only to the extent that people experience distress or difficulty coping with their concealable stigmatized identity prior to disclosure. If people can effectively cope with their identity and do not exhibit other markers of psychological distress (e.g., intrusive thoughts), disclosure may not impact psychological or health outcomes through this mechanism.

Social Support

Disclosure can also have a substantial impact on well-being because it is a necessary prerequisite to obtain social support. While they may be shielded from social rejection, individuals who keep their identities concealed do not have the chance to receive emotional and physical support from their confidants. While the presence of sufficient social support is strongly related to both psychological and physical well-being among individuals in the general population (Sarason, Sarason, & Gurung, 2001; Uchino, 2009) and those living with a wide variety of concealable stigmatized identities (e.g., Beals & Peplau, 2005; Beals et al., 2009; Jonzon & Lindblad, 2004; Smith et al., 2008), its absence may be particularly damaging to those who live with identities that are especially disruptive to their lives. For instance, individuals living with HIV/AIDS may strongly rely on individuals in their social network to take them to medical appointments and care for them as their health deteriorates. Individuals whose identities are based in traumatic life experiences such as sexual assault and childhood abuse may need intense emotional support as they deal with intrusive thoughts about their experiences and work to regain self-esteem and trust in others.

Recent evidence suggests that disclosure can, in fact, be a multiply mediated process wherein disclosure can be beneficial to the extent that it allows individuals to obtain social support and alleviate inhibition. In a daily diary study of gay and lesbian participants, researchers tested the possibility that disclosure affects well-being through three possible mechanisms: social support, emotional processing, and suppression (Beals et al., 2009). In this study, social support was the most consistent mediator between disclosure and well-being in both daily assessments of well-being and at a 2-month follow-up. While social support emerged as the strongest mediator, emotional processing—the degree to which individuals thought about their emotions and their causes—also mediated the effect of disclosure and well-being in the daily diary assessments, but not the 2-month follow-up. The third possible mechanism—suppression of thoughts and feelings related to the identity—did not emerge as a mediator of the relationship between disclosure and well-being. Thus, while the mediating effect of alleviation of inhibition was only partially supported (i.e., emotional processing, but not suppression, mediated the effects), this study provides initial empirical support for our assertion that disclosure may be a multiply mediated process.

A number of other studies also suggest that disclosure's ability to garner social support can yield psychological and health benefits. In the context of disclosure of sexual orientation in the workplace, research demonstrates that the beneficial effect of disclosure on job outcomes (e.g., greater job satisfaction, lower job anxiety) is largely accounted for by the types of reactions these disclosures elicit from coworkers (Griffith & Hebl, 2002). That is, to the extent that disclosure yields positive reactions from confidants, it can improve outcomes in the workplace. Further, several experimental studies have demonstrated that supportive confidant responses can be beneficial for well-being. In one study, researchers exposed participants to stressful stimuli (i.e., visual images of the Holocaust) and then manipulated whether people talked about their thoughts and feelings about the stimuli alone, with a validating confidant, with an invalidating confidant, or did not talk at all (Lepore et al., 2000). Compared to those who talked alone, participants who talked to a validating confidant reported fewer intrusive thoughts, although they did not experience other benefits such as less avoidance of stimuli-related thoughts or less perceived stress when re-exposed to the stimuli a day later. In a different manipulation, researchers asked participants to imagine an accepting confidant, a non-accepting confidant, or no confidant while writing about a personal secret (Rodriguez & Kelly, 2006). Their results indicate that participants who imagined disclosing to an accepting, supportive confidant reported fewer illness symptoms than participants who imagined disclosing to a non-accepting confidant at an 8-week follow-up.

However, when disclosers receive anything less than fully supportive reactions or are socially rejected, disclosure can be detrimental to well-being. Individuals living with a wide array of identities such as HIV/AIDS, history of abortion, sexual assault, and homosexuality all commonly report experiencing prejudice and discrimination as a result of disclosure (e.g., Corrigan & Kleinlein, 2005; Herek & Berrill, 1992). When people receive rejecting or socially unsupportive reactions from disclosure confidants, these reactions can be detrimental to psychological well-being, leading people to experience greater psychological distress (Major et al., 1990; Ullman, 1996. 2003).

In addition to these individual-level outcomes, disclosure can also affect the very nature of the relationship between the discloser and the confidant. When disclosures are met with positive and supportive responses, dyadic, relationship-based outcomes such as trust, liking, and intimacy may increase (e.g., Collins & Miller, 1994; Laurenceau et al., 1998; Laurenceau et al., 2005). For example, in a study of breast cancer patients and their romantic partners, perceived partner responsiveness to both cancer- and relationship-related disclosures mediated the effect of disclosure on intimacy for both the breast cancer patients and their romantic partners (Manne et al., 2004). However, when disclosures are met with negative and rejecting responses, the quality of these relationships may be compromised, leading to increased distrust and, potentially, dissolution of the relationship. Frequently, confidants may feel betrayed when disclosers reveal information about their identities to them and may, consequently, end these relationships (for a review, see Greene et al., 2003). Thus, the degree to which disclosure yields social support rather than social rejection can also have important implications for relationship outcomes.

Effect of Antecedent Goals

Considered within the broader DPM framework, when might individuals be most likely to benefit from disclosure's ability to garner social support? As we discussed earlier, recent evidence suggests that individuals who possess disclosure goals that focus on attaining positive relationship outcomes may be more likely to garner positive, supportive reactions from their confidants and, in turn, experience greater psychological well-being (Chaudoir & Quinn, in press; Garcia & Crocker, 2008). This provides preliminary evidence to support our theorizing about the impact of antecedent goals on disclosure outcomes. However, this evidence does not allow us to examine exactly why goals are related to more positive confidant responses and greater psychological well-being.

One possibility is that individuals with approach-focused disclosure goals are better able to communicate about their identities in ways that will elicit positive responses from their confidants. These skills are undoubtedly critical for the social support mechanism, although they may not be as beneficial for the other two mechanisms which are not directly affected by the confidant response. As we discussed earlier, individuals who possess approach-focused disclosure goals may be more adept at eliciting positive confidant responses than those who possess avoidance-focused disclosure goals. Further, because goals shape perceptual processes, disclosers who possess approach-focused goals may also be more likely to attend to positive cues that signal that the confidant has responded favorably.

Importantly, individuals with approach-focused goals may also be better suited to deal with the complex self-regulatory efforts that may be required after the disclosure event has ended. Following disclosure, the shared reality and the nature of the relationship between the discloser and confidant will necessarily change in order to accommodate the new and potentially stigmatizing information. For example, when disclosers share information about their identities with confidants, they will likely continue to address new and potentially complex issues in their relationships. Will confidants be more sensitive to disclosers' psychological and physical needs? Will confidants begin to wonder if disclosers are concealing other important information about themselves, or will they trust that the disclosers are now fully honest with them? Will confidants use this new information to judge or stigmatize disclosers in the future? Because disclosers who possess approach-focused goals are likely to remain focused on the opportunities for relationship growth and mutual understanding, they may also be more likely to view these adjustments and potential challenges as a normal and valuable part of the disclosure process.