Introduction

Since the cloning of the first membrane transporter, our understanding of the role of transporters in clinical drug disposition and response has grown enormously. In parallel, large scale genomewide variation studies and the emerging field of pharmacogenomics has ushered in a new understanding of variation in drug response. At the crossroads of the fields of pharmacogenomics and transporter biology is the NIH funded Pharmacogenomics of Membrane Transporters (PMT) project, centered at the University of California, San Francisco.

PMT is part of the NIH sponsored Pharmacogenetics Research Network (PGRN). Since its inception nine years ago, PMT has made many important scientific contributions to both pharmacogenomics and transporter biology and is poised to contribute even more with the recent advances in technology and the plethora of information about human genetic variation. In this manuscript, we describe the history and organizational structure of PMT and importantly, its contributions to the fields of transporter biology and pharmacogenomics. We discuss multiple collaborations that have been initiated by PMT investigators and our database, dbPMT, which was recently released publicly and provides a wealth of information for scientists in the fields of genomics, pharmacology and transporter biology. Finally, we briefly discuss future directions of PMT, which are aimed at advancing our understanding of the functional genomics of membrane transporters and the contribution of genetic variation in transporters to adverse and therapeutic drug response.

I. History of the PMT Project

In response to an RFA issued by NIH in 1999, investigators at UCSF began planning for submission of a proposal for a large center grant focused on pharmacogenomics of membrane transporters. A multi-disciplinary team of investigators, led by K. Giacomini, I. Herskowitz and N. Freimer, was formed, which included pharmacologists, geneticists, computational biologists, statisticians and molecular biologists, individuals who before that time had never collaborated in a scientific endeavor. During initial meetings, the team decided that the goal of a large center such as PMT was to seed the scientific community with new information about transporter genomics and pharmacogenomics to enable hypothesis generation. In addition to genomic, functional genomic and genotype to phenotype clinical studies, one large phenotype to genotype clinical study, the Genetics of Response to Anti-depressants (GRAD), which focused on the SSRI anti-depressants, was proposed. A password protected transporter database was proposed, which subsequently developed into a public database, dbPMT. The first grant proposal was successful, and was followed by a competitive renewal, funded in 2005, which extended PMT until 2010. Studies funded by the competitive renewal, which are ongoing, have a major focus on noncoding region variants. Clinical genotype to phenotype studies began in the second round, translating laboratory discoveries to clinical studies of drug disposition and response. Major discoveries of PMT along with a brief description of future directions are discussed below.

II. Multi-disciplinary Research Team and Organizational Structure of PMT

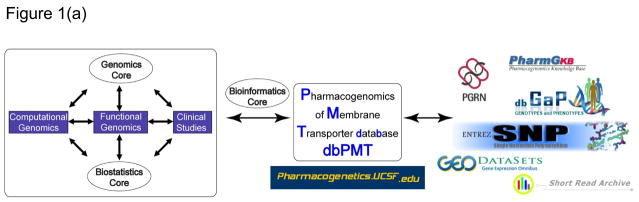

The success of PMT can be largely attributed to its multi-disciplinary research group and organizational structure, which facilitates high throughput sequencing, medium throughput functional genomics, and advances to clinical studies of drug disposition and response. The organizational structure of PMT includes three multi-disciplinary research teams and three research cores (see Figure 1). The functional genomics research team conducts mechanistic studies to test the functional significance of sequence variants in 150 membrane transporters. Selection of the 150 membrane transporters was based on the following criteria: (i) high expression levels in the liver, kidney and/or intestine; (ii) evidence in the literature that the transporter interacts with drugs in vitro; and (iii) if available, evidence from studies in knockout mice or humans that the transporter plays a role in vivo in pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics. The computational genomics research team interacts with the functional genomics team in the analysis of genomic information. The clinical studies research team conducts clinical studies including mechanistic genotype driven clinical studies, which translate discoveries made by the functional genomics team. Three cores support the research teams. The genomics core performs sequencing and genotyping. The biostatistics core supports data analysis and study design for the research teams. The bioinformatics core constructs and maintains both the password protected and the publicly available database, dbPMT. This core deposits PMT generated data into other relevant national databases (e.g., PharmGKB, dbSNP, dbGAP, GEO Datasets and SRA). Each team and core is led by a director, who serves on the PMT Steering Committee, which makes decisions about overall directions of the project. PMT is led by a principal and co-principal investigator and now includes a project director. This organizational structure and the active participation of the research team and core directors greatly facilitate the rapid implementation of new technologies and methodologies to address important problems in transporter pharmacogenomics.

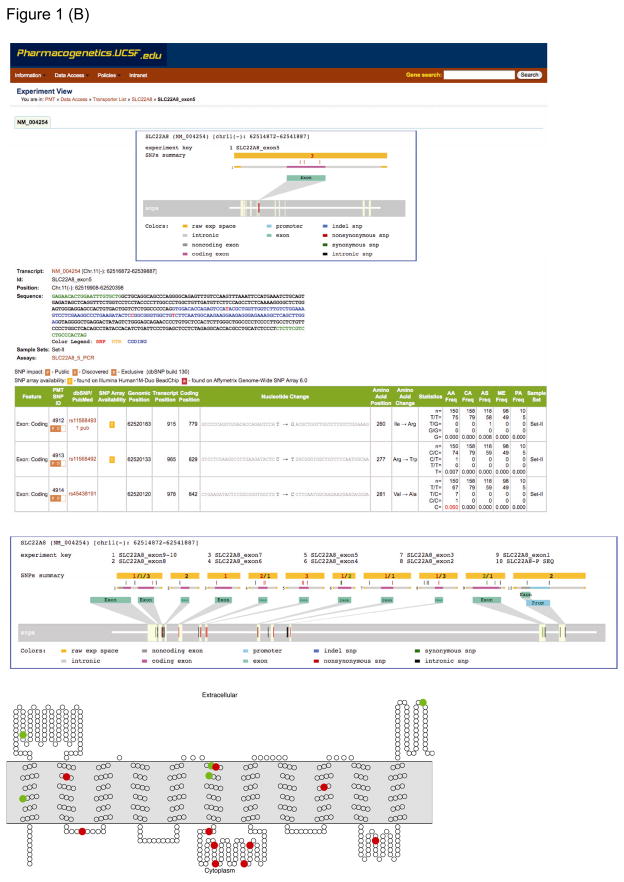

Figure 1.

Overview of the Pharmacogenomics of Membrane Transporters (PMT) project and dbPMT. (a) Organizational structure of PMT. (b) Screen views of dbPMT showing a typical detailed PMT experiment report—in this instance, from a sequencing experiment of the organic-anion transporter gene, SLC22A8 (OAT3). The middle section shows the details of the experiment, including interrogated genomic range and genotype information on detected variants. The bottom panel shows the putative secondary structure of SLC22A8 (OAT3) and positions of the nonsynonymous variants (red circles) and synonymous variants (green circles). The transmembrane topology diagram was rendered using TOPO2 transmembrane display software (http://www.sacs.ucsf.edu/TOPO2/topo2.html). SLC, solute carrier superfamily.

III. Major Research Findings

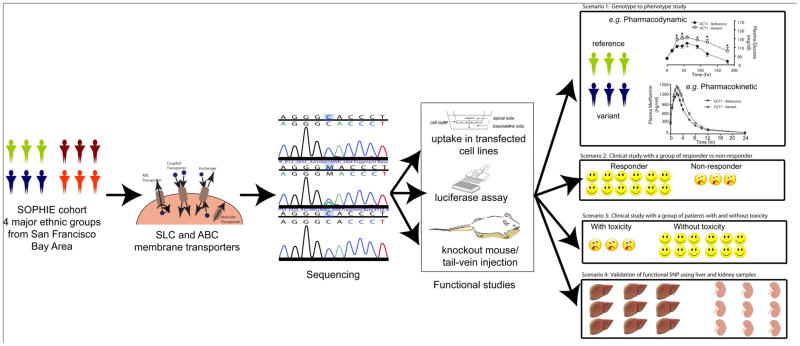

The focus of PMT is on transporters that play a role (or are suspected to play a role) in drug disposition and response. Of the 350 transporters in the Solute Carrier superfamily (SLC) and the 48 transporters in the ATP Binding Cassette (ABC) superfamily, PMT focuses on about 150. PMT has contributed new information about genetic variants in transporters, functional activity of variant transporters, and clinical relationships between variant transporters and drug disposition and response. Our scientific approach is depicted in Figure 2. Below we highlight our major findings.

Figure 2.

An overview of the scientific approaches used by PMT in SNP discovery and functional studies. The PMT SNP discovery studies involve resequencing of coding and noncoding regions of membrane transporter genes in healthy volunteers in four major ethnic groups (the SOPHIE cohort). Various in vitro and in vivo assays are used to characterize coding and noncoding region variants in transporters. In order to validate functional findings and to translate them from bench to clinic, one or more of the following scenarios are applicable. (i) Hypothesis-driven clinical studies to evaluate the role of functionally important genetic variants in drug disposition and response in the SOPHIE cohort (figure from scenario 1 reprinted from ref. 8). (ii) and (iii) Collaborative clinical studies involving PGRN investigators, CALGB, and GAP-J, with a focus on the role of genetic variants in transporters in drug response and toxicity. (iv) Association of functional SNPs with expression levels of transporters in liver and kidney samples. ABC, ATP-binding cassette; CALGB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B; GAP-J, Global Alliance in Pharmacogenomics, Japan; PGRN, Pharmacogenetics Research Network; PMT, Pharmacogenomics of Membrane Transporters project; SLC, solute carrier superfamily; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; SOPHIE, Study of Pharmacogenetics in Ethnically Diverse Populations.

SNP Discovery

PMT has identified sequence variants in 129 membrane transporter genes in the SLC and ABC superfamilies from DNA samples gathered from various sources. Most recently, DNA has come from 272 ethnically diverse individuals (68 African American, 68 European Americans, 68 Mexican Americans and 68 Chinese Americans) from the SOPHIE cohort, a group of individuals who have donated DNA samples and agreed to be called back for future clinical pharmacogenetic studies. PMT sequencing efforts have resulted in the discovery of over 3100 SNPs, from which many novel and functionally important variants have been identified. SNPs discovered by PMT are having an increasing impact on genetic and pharmacogenetic studies. For example, 697 SNPs discovered by PMT are available on the Illumina 1M Duo Beadchip.. These PMT SNPs have important implications to informing current genomewide association studies.

Functional Genomics

Table 1 describes the major discoveries from our functional analysis in cellular studies, in genotype to phenotype clinical studies and in large collaborative studies. Collectively, 220 coding region variants (nonsynonymous variants and indels) have been characterized in cellular assays, of which approximately 15% to 20% exhibited significantly reduced function compared to the reference allele [1–6]. In general, we observed that variants with reduced function are rarer than variants that retain function [7] and that multiple less common variants in a single transporter may have reduced function [8]. For example, rare variants (< 1 % minor allele frequency) in OCTN1 (D165G and R282X), OAT3 (R149S, Q239X and I260R), MATE1 (G64D and V480M) and CNT1 (S546P) showed greater reduction in the uptake of their substrates compared to more common variants in the same genes [1, 6, 9, 10]. We also observed that some variants in OAT3 (I305F), OCT2 (R400C and K432Q) and OCTN2 (Y449D) altered the substrate/inhibitor specificity and/or kinetics of the transporter [4, 6, 11]. In addition, we recently examined the function of genetic variants in the proximal promoter region (defined as −250 to +50 bp from the transcription start site) of various membrane transporters in luciferase reporter assays [12–15]. Unlike coding region variants, we observed that none of the 116 promoter variants tested produced a total loss of function suggesting that promoter variants may modulate but not abolish function [13–15]. In more detailed analysis of promoter region variants in several transporters, we showed that the mechanisms for altered function of promoter variants in CNT2 (rs2413775) and MATE1 (rs2252281) involved disruption or creation of a transcription factor binding site [13, 14] and were associated with expression levels of the transporter in tissue samples, including lymphoblastoid cell lines and liver and kidney samples [4, 14, 15] (Figure 2, scenario 4). Our studies suggest that promoter region variants associated with altered function may be common and that the context of a promoter region (and a coding region) variant in terms of its haplotype may modulate function.

Table 1.

The allele frequency and the findings of the the functional variants in African Americans (AA), European Americans (CA), Asians (AS) and Mexicans (ME).

| (A) In vitro functional studies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene (common name) | Variant | rs# | AA | CA | AS | ME | Description of Findings | References |

| SLC22A1 (OCT1) | R61C | rs12208357 | 0 | 7.2 | 0 | 5.6 | Reduced metformin and MPP+ uptake in transfected cells | [5, 18] |

| SLC22A1 (OCT1) | G220V | rs36103319 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| SLC22A1 (OCT1) | G401S | rs34130495 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| SLC22A1 (OCT1) | G465R | rs34059508 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| SLC22A1 (OCT1) | S189L | rs34104736 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | Reduced metformin uptake intransfected cells | [18] |

| SLC22A1 (OCT1) | M420del | rs35167514, rs34305973 and rs35191146 | 2.9 | 18.5 | 0 | 21.4 | ||

| SLC22A1 (OCT1) | P341L | rs2282143 | 8.2 | 0 | 11.7 | 0 | Reduced MPP+ uptake in oocytes | [5] |

| SLC22A2 (OCT2) | R400C | rs8177516 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Increased sensitivity to inhibition by TBA in oocytes | [11] |

| SLC22A2 (OCT2) | K432Q | rs8177517 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | ||

| SLC22A2 (OCT2) | A270S | rs316019 | 11 | 15.8 | 8.6 | 15 | Increased metformin uptake in transfected cells | [19] |

| SLC22A4 (OCTN1) | D165G | rs11568510 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0 | Reduced TEA and betaine uptake in transfected cells | [21] |

| SLC22A4 (OCTN1) | R282X | rs11568503 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| SLC22A4 (OCTN1) | M205I | rs11568500 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Reduced TEA and betaine uptake in transfected cells | [21] |

| SLC22A4 (OCTN1) | L503F | rs1050152 | 8.8 | 41.2 | 0 | 23 | Altered substrate specificity in transfected cells | [21] |

| SLC22A5 (OCTN2) | −207G>C | rs2631367 | 38.2 | 50 | 0 | 32.1 | −207G allele is associated with increased L-carnitine transport | [4] |

| SLC22A5 (OCTN2) | F17L | rs11568520 | 0 | 0 | 1.7 | 0 | Reduced TEA and L-carnitine uptake in transfected cells | [4] |

| SLC22A5 (OCTN2) | V481I | rs11568513 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| SLC22A5 (OCTN2) | Y449D | rs115685514 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Altered substrate specificity in transfected cells | [4] |

| SLC22A6 (OAT1) | R454Q | rs11568634 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Reduced adefovir uptake in oocytes | [22] |

| SLC22A8 (OAT3) | R149S | rs45566039 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0 | Reduced estrone sulfate and cimetidine uptake in transfected cells | [6] |

| SLC22A8 (OAT3) | Q239X | rs11568496 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0 | ||

| SLC22A8 (OAT3) | I260R | rs11568493 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0 | ||

| SLC22A8 (OAT3) | R277W | rs11568492 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Altered substrate specificity in transfected cells | [6] |

| SLC22A8 (OAT3) | I305F | rs11568482 | 0 | 0 | 3.5 | 1.1 | ||

| SLC28A1 (CNT1) | V189I | rs2290272 | 18.9 | 28.5 | 35 | 50 | Altered kinetics of gemcitabine in transfected cells | [10] |

| SLC28A1 (CNT1) | V385Del | rs17215989 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Reduced thymidine uptake in oocytes | [10] |

| SLC28A1 (CNT1) | S546P | rs45584739 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| SLC28A2 (CNT2) | −146T>A | rs2413775 | 60 | 72.5 | 26.7 | 40 | −146A allele showed increased luciferase activity in reporter assays in cells and in vivo assay. | [13] |

| SLC28A2 (CNT2) | F355S | rs17215633 | 3.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Altered substrate specificity with respect to inosine and uridine. | [23] |

| SLC28A3 (CNT3) | G367R | rs11568388 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0 | Reduced uptake of inosine and thymidine in oocytes | [24] |

| SLC29A2 (ENT2) | D5Y | rs8187643 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Reduced uptake of guanosine and inosine in oocytes | [25] |

| SLC29A2 (ENT2) | del551-556 | rs8187649 −, rs8187656 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| SLC29A2 (ENT2) | Ser282DEL | rs8187656 and rs8187655 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| SLC47A1 (MATE1) | −66T>C | rs2252281 | 44.5 | 32.1 | 23.1 | 28.9 | Haplotypes containing the variant showed decreased luciferase activity in reporter assays in cells and in vivo assay. | [14] |

| SLC47A1 (MATE1) | G64D | ss120037446 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | Reduced uptake of metformin, paraquat and oxaliplatin in transfected cells | [1] |

| SLC47A1 (MATE1) | V480M | ss120037460 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0 | ||

| SLC47A1 (MATE1) | L125F | ss120037449 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 5.1 | Altered uptake transport for oxaliplatin, metformin and paraquat in transfected cells. | [1] |

| SLC47A1 (MATE1) | V338I | rs35790011 | 5.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Altered uptake transport for oxaliplatin, metformin and paraquat in transfected cells. | [1] |

| SLCO1A2 (OATP1A2) | R168C | rs11568564 | 0 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | Reduced uptake of estrone sulfate and methotrexate in oocytes | [26] |

| SLCO1A2 (OATP1A2) | E172D | rs11568563 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 0 | 2 | ||

| SLCO1A2 (OATP1A2) | N278DEL | rs72559749 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| SLC15A1 (PEPT1) | F28Y | rs8187817 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Reduced cephalexin uptake in transfected cells | [27] |

| SLC15A2 (PEPT2) | F350L | rs2257212 | 47.5 | 52.5 | 37.5 | 65 | PEPT2*1 (350L-409P-509R) showed lower Km for glycyl-sarcosine compared to PEPT2*2 (350F-409S-509K) in transfected cells | [28] |

| SLC15A2 (PEPT2) | S409P | rs1143671 | 46.5 | 51 | 36.7 | 70 | [28] | |

| SLC15A2 (PEPT2) | K509R | rs1143672 | 46.4 | 52 | 36.7 | 70 | [28] | |

| ABCB1 (P-gp) | M89T | rs35810889 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | Increased daunorubicin, doxorubicin, valinomycin or actinomycin D resistance in transformed yeast. | [29] |

| ABCB1 (P-gp) | L662R | rs3657960 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ABCB1 (P-gp) | R669C | rs35023033 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ABCB (P-gp)1 | S1141T | rs2229107 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 5 | ||

| ABCB1 (P-gp) | W1108R | rs35730308 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Decreased daunorubicin, doxorubicin, valinomycin or actinomycin D resistance in transformed yeast. | [29] |

| ABCB1 (P-gp) | A893T | rs2032582 | 0.5 | 3.6 | 6.7 | 0 | Decreased intracellular calcein levels (increased function) in transfected cells | [30] |

| ABCB1 (P-gp) | A893S | rs2032582 | 10 | 46.4 | 45 | 40 | Increased intracellular BODIPY-FL- paclitaxel levels (decreased function) in transfected cells. | [30] |

| ABCB1 (P-gp) | V1251I | rs28364274 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | Decreased intracellular calcein levels (increased function), (ii) increased intracellular BODIPY-FL-paclitaxel levels (decreased function), in transfected cells. | [30] |

| ABCB1 (P-gp) | N21D/1236C>T/A893S/3435C>T | 2 | 7.5 | 1.6 | 0 | Increased intracellular BODIPY-FL- paclitaxel levels (decreased function), (ii) less sensitive to cyclosporine A inhibition than reference, in transfected cells. | [30] | |

| ABCC4 (MRP4) | G187W | rs11568658 | 0 | 2.5 | 10.8 | 13 | Increased intracellular AZT and PMEA levels(decreased function) in transfected cells | [3] |

| ABCC4 (MRP4) | G487E | rs11568668 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0 | ||

| SLC18A2 (VMAT2) | T68M | n.a | 8/900 = 0.89% | Reduced sensitivity to the VMAT inhibitor reserpine in membranes prepared from transfected cells. | [31, 32] | |||

| SLC18A2 (VMAT2) | M453I | n.a | 1/900=0.11% | Higher Km for serotonin and reduced sensitivity to VMAT inhibitor reserpine in membranes prepared from transfected cells. | [31, 32] | |||

| (B) Genotype to phenotype clinical studies | ||||||||

| SLC22A1 (OCT1) | reduced function nonsynony mousSNPs | OCT1-reference vs OCT1-variant (R61C, G401S, 420del, G465R) | see individual variant for the allele frequency (as shown above) | Change in metformin kinetics and pharmacologic effects as measured by oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) | [8, 18] | |||

| SLC22A2 (OCT2) | A270S | rs316019 | 11 | 15.8 | 8.6 | 15 | Higher renal clearance and net tubular secretion of metformin in individual with the OCT2variant. | [19] |

| SLC22A4 (OCTN1) | L305F | rs1050152 | 8.8 | 41.2 | 0 | 23 | Higher gabapentin exposure and lower renal clearance/tubular secretion in individuals carrying OCTN1 variant. | [20] |

| SLC22A5 (OCTN2) | −207G>C | rs2631367 | 38.2 | 50 | 0 | 32.1 | No appreciable effect of this variant on carnitine disposition | [15] |

| SLC22A6 (OAT1) | R454Q | rs11568634 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No difference in renal clearance and secretory clearance of adefovir in family-based studies. | [22] |

| (C) Large clinical studies | ||||||||

| ABCC1 (MRP1) | IVS11 - 48C>T | rs3765129 | 3 | 16.2 | 8.3 | 25 | Approximately 50% of the variation in ANC nadir in cancer patients is explained by rs3765129, rs2306283 and UGT1A1*93; the AUC of irinotecan, SN-38, SN-38 glucuronide and APC are influenced by rs3740066, rs2306283, rs35605, rs10276036, and rs717620. | [33] |

| SLCO1B1 (OATP1B1) | N130D | rs2306283 | 72.8 | 44.1 | 80.1 | 47.8 | ||

| ABCC2 (MRP2) | 3972C>T | rs3740066 | 27.3 | 38.3 | 19.0 | 25.0 | ||

| ABCC2 (MRP2) | −24C>T | rs717620 | 6 | 19.5 | 15 | 15 | ||

| ABCC1 (MRP1) | 1684C>T | rs35605 | 11.5 | 19.5 | 25 | 11.1 | ||

| ABCB1 (P-gp) | IVS9 - 44A>G | rs10276036 | 25.5 | 45 | 68.5 | 45 | ||

| ABCC2 (MRP2) | −1019A>G | rs2804402 | 36.5 | 43 | 16.7 | 20 | ABCC2*2 (−1019A>G) is associated with lower irinotecan clearance and with significant reduction of severe diarrhea in cancer patients. | [34] |

Computational Genomics

Computational analysis of ABC transporters has provided hypotheses for domain interactions in the transporters, which can then be verified experimentally [16]. Despite the challenges in membrane protein crystallization, PMT investigators and collaborators in the NIGMS funded Center for Structure of Membrane Proteins (led by R. Stroud) have successfully used medium-throughput approaches for the rapid expression and solubilization of SLC transporters, which can then be crystallized [17]. In addition, we have performed a large computational analysis of the Solute Carrier Superfamily to identify a number of potential transporters in the human genome, which are candidate transporters for drug disposition and response (unpublished data).

Genotype to Phenotype Clinical Studies

Ultimately, the goal of our genomic and functional genomic studies is to generate testable hypotheses about the effects of variants on clinical drug disposition and response. To date, PMT functional genomics studies have led to many clinical studies, some that have been completed and are published and others that are ongoing. These studies, in general, make use of SOPHIE subjects who have indicated a willingness to be called back for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies. One of the unique aspects of research in the genetics of drug response as opposed to the genetics of disease risk is that the effect of a genetic variant can be directly tested in genotype to phenotype studies. That is, individuals with particular variants can be given a drug to directly test a hypothesis that a genetic variant(s) may produce a change in pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics (Figure 2, scenario 1 [8, 18]). These rich studies are important proof of concept translational studies, which link functional genetic variants discovered in the laboratory to clinical drug response. Several PMT led genotype to phenotype studies have focused on genetic variants in the organic cation transporters OCT1 and OCT2, on response and disposition to the anti-diabetic drug, metformin [8, 18, 19]. We have also determined the role of genetic variants in transporters in variation in renal drug clearance (Table 1) [19, 20].

IV. PMT Collaborative Studies

In parallel to our genotype to phenotype clinical studies, PMT is involved in many collaborative studies, which have a focus on membrane transporters or for which transporters may be important determinants of drug efficacy and adverse effects. Below we briefly describe two major collaborations.

CALGB

The large, well-phenotyped patient populations in National Cancer Institute supported cooperative clinical trial group Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) and other cooperative trial groups provide a rich resource for testing the clinical effects of membrane transporter variants. Clinical studies in cancer are particularly of interest to PMT since membrane transporters play a significant role in resistance to anticancer treatment. PMT investigators have been involved in the design and implementation of pharmacogenomic correlative studies to multiple treatment trials in breast, colon and prostate cancer. Both candidate gene and genomewide approaches are planned for the identification of genetic factors that influence tumor response and adverse events in these populations (Figure 2, scenario 2 and 3). In all studies, both direct hypothesis testing and exploratory hypothesis generating objectives are included, thus maximizing the use of the large amount of clinical and drug response data collected in such trials. The efforts of PMT and other PGRN investigators in CALGB serve as a model for the establishment of similar correlative studies in other cooperative groups.

GAP-J

The Global Alliance in Pharmacogenomics, Japan (GAP-J) is an existing alliance (http://www.nigms.nih.gov/Initiatives/PGRN/GAP/) between the PGRN and the Center for Genomic Medicine (CGM) of the Riken, Yokohama Institute in Japan (see http://www.src.riken.jp/english/ for description of CGM). This international alliance brings together scientists in multiple research disciplines to conduct research in pharmacogenomics. In particular, the research focuses on genomewide association studies (GWAS) to identify genetic predictors of therapeutic and adverse reactions to medicines. Fourteen GWAS studies are currently ongoing as part of GAP-J. PMT investigators have been involved in the inception and leadership of GAP-J and are active investigators in GAP-J. Several of the collaborative CALGB studies and the GRAD study have been accepted for GAP-J GWAS, and it is anticipated that GAP-J studies will make enormous contributions to the field of pharmacogenomics and its translation to personalized medicines.

V. dbPMT

Initially created as a password protected intranet for PMT investigators, dbPMT has expanded to include a public site. Created by the Bioinformatics Core of PMT, dbPMT allows investigators to retrieve information about (i) the expression levels of membrane transporters in different tissues and cell lines, (ii) genetic variants of membrane transporters, including the nature of the variant (e.g., coding, noncoding), its position, identification number (rs#), and its frequency in four major ethnic groups, (iii) haplotypes of transporters in four ethnic groups, and (iv) function of genetic variants of membrane transporters. The database can be accessed at the following url: http://pharmacogenetics.ucsf.edu. This public site is user friendly and highly relevant to investigators in membrane transporter research and also to scientists with interests in identifying variants associated with risk for disease or drug response.

VI. Future Directions

Throughout its nine year history, PMT has been a leader in the field of pharmacogenomics of membrane transporters. It is anticipated that in the future, PMT will continue to pioneer new directions in genetic variation in membrane transporters and its implications to clinical drug response. In particular, PMT is planning to (a) develop a robust framework for computational predictions of the effects of coding region variants on transporter function and drug response; (b) to obtain a new understanding about variants in UTRs, introns and in intergenic regions surrounding membrane transporters; (c) to harness computation to identify new regulatory proteins and response elements in transporter genes; and (d) to continue our clinical studies in three major directions. First, PMT has been highly successful in genotype to phenotype clinical studies using SOPHIE and testing the clinical effects of transporter variants identified in PMT discovery studies. These studies will continue, but will focus on the effects of noncoding region variants, haplotypes, and will go beyond single variants in a membrane transporter to include the effects of multiple variants. An emphasis on the effects of genetic variants on drug-drug interactions is anticipated. PMT will also continue its major collaborative studies with CALGB and GAP-J. Other collaborations are likely to ensue from ongoing PMT discoveries. Finally, PMT studies have led to an understanding of the contribution of genetic variants in membrane transporters to the response and disposition of the important anti-diabetic drug, metformin [8, 18]. These studies will be expanded and GWAS and other strategies will be used in identifying genetic variants that associate with response to metformin.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from GM61390, a center grant funded as part of the NIH Pharmacogenetics Research Network. We thank Ms Susan J. Johns, Ms Rebecca Bogenrief and Mr. Juan Gonzalez for their assistance with the figures.

Abbreviations

- PMT

Pharmacogenetics of Membrane Transporters

- OCT

organic cation transporter

- OAT

organic anion transporter

- ABC

ATP-Binding Cassette

- OATP

organic anion transporter polypeptide

References

- 1.Chen Y, Teranishi K, Li S, Yee SW, Hesselson S, Stryke D, et al. Genetic variants in multidrug and toxic compound extrusion-1, hMATE1, alter transport function. Pharmacogenomics J. 2009 Apr;9(2):127–36. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2008.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leabman MK, Huang CC, DeYoung J, Carlson EJ, Taylor TR, de la Cruz M, et al. Natural variation in human membrane transporter genes reveals evolutionary and functional constraints. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 May 13;100(10):5896–901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730857100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abla N, Chinn LW, Nakamura T, Liu L, Huang CC, Johns SJ, et al. The human multidrug resistance protein 4 (MRP4, ABCC4): functional analysis of a highly polymorphic gene. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008 Jun;325(3):859–68. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.136523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urban TJ, Gallagher RC, Brown C, Castro RA, Lagpacan LL, Brett CM, et al. Functional genetic diversity in the high-affinity carnitine transporter OCTN2 (SLC22A5) Mol Pharmacol. 2006 Nov;70(5):1602–11. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shu Y, Leabman MK, Feng B, Mangravite LM, Huang CC, Stryke D, et al. Evolutionary conservation predicts function of variants of the human organic cation transporter, OCT1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 May 13;100(10):5902–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730858100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erdman AR, Mangravite LM, Urban TJ, Lagpacan LL, Castro RA, de la Cruz M, et al. The human organic anion transporter 3 (OAT3; SLC22A8): genetic variation and functional genomics. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006 Apr;290(4):F905–12. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00272.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urban TJ, Sebro R, Hurowitz EH, Leabman MK, Badagnani I, Lagpacan LL, et al. Functional genomics of membrane transporters in human populations. Genome Res. 2006 Feb;16(2):223–30. doi: 10.1101/gr.4356206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shu Y, Brown C, Castro RA, Shi RJ, Lin ET, Owen RP, et al. Effect of genetic variation in the organic cation transporter 1, OCT1, on metformin pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Feb;83(2):273–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urban TJ, Giacomini KM, Risch N. Haplotype structure and ethnic-specific allele frequencies at the OCTN locus: implications for the genetics of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005 Jan;11(1):78–9. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200501000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray JH, Mangravite LM, Owen RP, Urban TJ, Chan W, Carlson EJ, et al. Functional and genetic diversity in the concentrative nucleoside transporter, CNT1, in human populations. Mol Pharmacol. 2004 Mar;65(3):512–9. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leabman MK, Huang CC, Kawamoto M, Johns SJ, Stryke D, Ferrin TE, et al. Polymorphisms in a human kidney xenobiotic transporter, OCT2, exhibit altered function. Pharmacogenetics. 2002 Jul;12(5):395–405. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hesselson S, Matsson P, Shima JE, Fukushima H, Yee SW, Kobayashi Y, et al. Genetic variation in the proximal promoter of ABC and SLC superfamilies: Liver and Kidney specific expression and promoter activity predict variation. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(9):e6942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yee SW, Shima JE, Hesselson S, Nguyen L, De Val S, Lafond RJ, et al. Identification and characterization of proximal promoter polymorphisms in the human concentrative nucleoside transporter 2 (SLC28A2) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009 Mar;328(3):699–707. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi JH, Yee SW, Kim MJ, Nguyen L, Lee JH, Kang JO, et al. Identification and characterization of novel polymorphisms in the basal promoter of the human transporter, MATE1. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009 Sep 9; doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328330eeca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tahara H, Yee SW, Urban TJ, Hesselson S, Castro RA, Kawamoto M, et al. Functional Genetic Variation in the Basal Promoter of the Organic Cation/Carnitine Transporters, OCTN1 (SLC22A4) and OCTN2 (SLC22A5) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009 Jan 13; doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.146449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly L, Karchin R, Sali A. Protein interactions and disease phenotypes in the ABC transporter superfamily. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2007:51–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M, Hays FA, Roe-Zurz Z, Vuong L, Kelly L, Ho CM, et al. Selecting optimum eukaryotic integral membrane proteins for structure determination by rapid expression and solubilization screening. J Mol Biol. 2009 Jan 23;385(3):820–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shu Y, Sheardown SA, Brown C, Owen RP, Zhang S, Castro RA, et al. Effect of genetic variation in the organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1) on metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2007 May;117(5):1422–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI30558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Li S, Brown C, Cheatham S, Castro RA, Leabman MK, et al. Effect of genetic variation in the organic cation transporter 2 on the renal elimination of metformin. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009 Jul;19(7):497–504. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32832cc7e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urban TJ, Brown C, Castro RA, Shah N, Mercer R, Huang Y, et al. Effects of genetic variation in the novel organic cation transporter, OCTN1, on the renal clearance of gabapentin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Mar;83(3):416–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urban TJ, Yang C, Lagpacan LL, Brown C, Castro RA, Taylor TR, et al. Functional effects of protein sequence polymorphisms in the organic cation/ergothioneine transporter OCTN1 (SLC22A4) Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007 Sep;17(9):773–82. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3281c6d08e.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujita T, Brown C, Carlson EJ, Taylor T, de la Cruz M, Johns SJ, et al. Functional analysis of polymorphisms in the organic anion transporter, SLC22A6 (OAT1) Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005 Apr;15(4):201–9. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200504000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owen RP, Gray JH, Taylor TR, Carlson EJ, Huang CC, Kawamoto M, et al. Genetic analysis and functional characterization of polymorphisms in the human concentrative nucleoside transporter, CNT2. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005 Feb;15(2):83–90. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200502000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Badagnani I, Chan W, Castro RA, Brett CM, Huang CC, Stryke D, et al. Functional analysis of genetic variants in the human concentrative nucleoside transporter 3 (CNT3; SLC28A3) Pharmacogenomics J. 2005;5(3):157–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owen RP, Lagpacan LL, Taylor TR, De La Cruz M, Huang CC, Kawamoto M, et al. Functional characterization and haplotype analysis of polymorphisms in the human equilibrative nucleoside transporter, ENT2. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006 Jan;34(1):12–5. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.006270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badagnani I, Castro RA, Taylor TR, Brett CM, Huang CC, Stryke D, et al. Interaction of methotrexate with organic-anion transporting polypeptide 1A2 and its genetic variants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006 Aug;318(2):521–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderle P, Nielsen CU, Pinsonneault J, Krog PL, Brodin B, Sadee W. Genetic variants of the human dipeptide transporter PEPT1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006 Feb;316(2):636–46. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.094615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinsonneault J, Nielsen CU, Sadee W. Genetic variants of the human H+/dipeptide transporter PEPT2: analysis of haplotype functions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004 Dec;311(3):1088–96. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.073098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeong H, Herskowitz I, Kroetz DL, Rine J. Function-altering SNPs in the human multidrug transporter gene ABCB1 identified using a Saccharomyces-based assay. PLoS Genet. 2007 Mar 9;3(3):e39. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gow JM, Hodges LM, Chinn LW, Kroetz DL. Substrate-dependent effects of human ABCB1 coding polymorphisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008 May;325(2):435–42. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burman J, Tran CH, Glatt C, Freimer NB, Edwards RH. The effect of rare human sequence variants on the function of vesicular monoamine transporter 2. Pharmacogenetics. 2004 Sep;14(9):587–94. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glatt CE, DeYoung JA, Delgado S, Service SK, Giacomini KM, Edwards RH, et al. Screening a large reference sample to identify very low frequency sequence variants: comparisons between two genes. Nat Genet. 2001 Apr;27(4):435–8. doi: 10.1038/86948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Innocenti F, Kroetz DL, Schuetz E, Dolan ME, Ramirez J, Relling M, et al. Comprehensive Pharmacogenetic Analysis of Irinotecan Neutropenia and Pharmacokinetics. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Apr 6; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Jong FA, Scott-Horton TJ, Kroetz DL, McLeod HL, Friberg LE, Mathijssen RH, et al. Irinotecan-induced diarrhea: functional significance of the polymorphic ABCC2 transporter protein. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Jan;81(1):42–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]