Abstract

Organophosphorus (OP) pesticides are a broad class of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors that are responsible for tremendous morbidity and mortality worldwide, contributing to an estimated 300,000 deaths annually. Current pharmacotherapy for acute OP poisoning includes the use of atropine, an oxime, and benzodiazepines. However, even with such therapy, the mortality from these agents are as high as 40%.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of OPs is an attractive new potential therapy for acute OP poisoning. A number of bacterial OP hydrolases have been isolated. A promising OP hydrolase is an enzyme isolated from Agrobacterium radiobacter, named OpdA. OpdA has been shown to decrease lethality in rodent models of parathion and dichlorvos poisoning. However, pharmacokinetic data have not been obtained. In this study, we examined the pharmacokinetics of OpdA in an African Green Monkey model.

At a dose of 1.2 mg/kg the half-life of OpdA was approximately 40 minutes, with a mean residence time of 57 minutes. As expected, the half-life did not change with the dose of OpdA given: at doses of 0.15 and 0.45 mg/kg, the half-life of OpdA was 43.1 and 38.9 minutes, respectively. In animals subjected to 5 daily doses of OpdA, the residual activity that was measured 24 hours after each OpdA dose increased 5-fold for the 0.45 mg/kg dose and 11-fold for the 1.2 mg/kg dose.

OpdA exhibits pharmacokinetics favorable for the further development as a therapy for acute OP poisoning, particularly for hydrophilic OP pesticides. Future work to increase the half-life of OpdA may be beneficial.

Keywords: organophosphorus, pesticide, hydrolysis, monkey

1. Introduction

Organophosphorus (OP) pesticide poisoning is a leading cause of premature death in many developing countries, killing an estimated 200,000 people every year in the Asia-Pacific region alone [1]. In North America and Europe, the situation is quite different. While pesticide poisoning does occur, the main risk of OP poisoning is from terrorist attacks on civilian or military populations through the release of OP nerve gases in crowded spaces or introduction of highly toxic pesticides into urban water supplies or by release of OPs by accident or natural disaster.

The acute toxicity of OPs is primarily due to inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [2, 3]. Current therapy for OP poisoning requires resuscitation with the use of oxygen and of atropine, followed by administration of oximes to reactivate AChE, plus benzodiazepines to prevent neurological impairment [4, 5]. However, these antidotes have limited effectiveness and between 10 and 40% of patients, depending on the responsible OP, die even with intensive care support [6]. Although OP pesticides have been a clinical problem for 50 years, no new therapies have been introduced since the 1960s. Because early therapeutic interventions lead to improved outcomes after OP poisoning, a treatment that is safe and highly effective, and that can be given by first responders at the site of poisoning, should markedly improve outcome.

Both bacteria and humans make enzymes that hydrolyze OP compounds [7, 8]. Bacterial OP hydrolases have the potential to provide an affordable, widely available, and safe treatment that is rapidly effective against a wide variety of OPs [9]. Recently, recombinant enzymes with enhanced activities against many currently used OPs have been developed [10]. However, a number of further steps are required before clinical trials can be started in humans with OP poisoning.

Recently, a metal-dependent OP hydrolase called OpdA, from Agrobacterium radiobacter, that shows high activity to many chemically distinct OPs has been characterized (Table 1) [11, 12]. OpdA possesses a different substrate range than another OP hydrolase (OPH) that has undergone efficacy testing in animals (Table 2). OpdA has similar activity towards the OPs with diethyl side-chains, and substantially higher catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) towards the dimethyl OPs, aliphatic OPs, and the nerve agent analog demeton-S [11]. For example, the kcat of OpdA towards methyl parathion is 1200 sec−1 in comparison to 82 sec−1 for OPH. Finally, OpdA has been shown to be more stable that OPH [13]. OpdA has also been shown to have high levels of activity against authentic G-series nerve agents [14]. Methods for high level heterologous expression of OpdA in E. coli and for its efficient purification are now well established. The combination of its high catalytic efficiency, broad substrate range, and stability make it an excellent therapeutic OP hydrolase candidate.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study enzyme and, for comparison, Oph.

| OP hydrolase | Chemistry of OP | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethyl-aromatic (ethyl parathion) | Methyl-aromatic (methyl parathion) | Methyl-aliphatic (dichlorvos)* | VX analogue (demeton-S) | |||||||||

| Km | kcat | kcat/Km | Km | kcat | kcat/Km | Km | kcat | kcat/Km | Km | kcat | kcat/Km | |

| OpdA | 110 | 1500 | 13.6 | 100 | 1200 | 12 | 182 | 149 | 0.82 | 340 | 1.9 | 0.006 |

| Oph | 240 | 630 | 2.6 | 200 | 82 | 0.41 | not done | not done | not done | 220 | 0.04 | 0.0002 |

The Km is expressed in μM, the kcat in sec−1 and the kcat/Km in sec−1.μM−1 OpdA and Oph kinetics (except dichlorvos) are described on similarly prepared enzymes in Yang et al [11]. Oph does not have measurable activity towards aliphatic OPs [38].

Dichlorvos assays were performed at room temperature (methods unpublished) approximately 35% higher activity would be expected at 37°C.

Table 2.

OpdA activity measured before 5 daily doses of 0.45 mg/kg, and 30 minutes after the fifth daily dose.

| Sample drawn before dose number: | μM/sec/μL plasma |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.021 |

| 2 | 0.087 |

| 3 | 0.108 |

| 4 | 0.105 |

| 5 | 0.093 |

| 30 mins after dose no. 5 | 36.229 |

Non-human primates (NHP) are the animals phylogenetically closest to humans. For biomedical research, they are considered to be the animal which physiologically most closely approximates effects in man[15]. The rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) has traditionally served as the NHP species of choice for much of biomedical research, particularly with AChE inhibitors. However, there exists now a worldwide shortage of Rhesus monkeys for biomedical research, the result of which is a tremendous financial burden of working with these animals. Additionally, rhesus monkeys are able to transmit Macacine herpesvirus 1 (termed Herpes B virus), a virulent infectious agent with monkey-to-human spread[16]. This infection risk carries additional requirements for animal husbandry, personal protective equipment, and special animal serologic monitoring and isolation. Therefore, new NHP models for pesticide and nerve agent poisoning are needed [17].

The African green monkey (Chlorocebus sabaceus, aka vervet) may be an ideal replacement for the rhesus monkey in biomedical research. They are considerably less aggressive than rhesus and well-trained personnel can perform repeated blood sampling from superficial veins with minimal restraint. African green monkeys are readily available from a variety of sources for significantly less than the price of other NHP. Importantly, unlike rhesus or cynomolgus monkeys, African green monkeys do not carry the Herpes B virus.

The purpose of this study is to take the first step towards development of a novel therapy for OP poisoning, by testing the pharmacokinetics and preliminary safety of the recombinant bacterial OP hydrolase OpdA in NHP model of OP poisoning. Proof that the enzyme is safe, and demonstrates sufficient pharmacokinetic properties in this model should provide the necessary impetus for further development for human use.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 OpdA preparation

The wild-type opdA gene was inserted between the NdeI and EcoR1 restrction sites of the pETMCSI plasmid [18]. BL21(DE3)RecA− (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, U.S.A) cells were transformed with pETMCSI-opdA vector heat-shock as per manufacturers instructions. Cells were grown on a Luria-Bertani broth-agar plate (containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin) at 37° C overnight. A single colony was inoculated into 50 mL Terrific broth (TB) medium supplemented with 1 mM CoCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and 100 μg/mL ampicillin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and incubated at 37° C until mid-log phase. This start-culture was then diluted 1:50 in 2 L of the same medium and grown at 30 ° C for 40 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 x g for 20 min at 4° C and resuspended in 50 mL buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), pH 8.0, with 1 mM CoCl2 and 1 x Bugbuster cell lysis reagent and 1 U/mL benzonase (Novagen, EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, New Jersey, U.S.A.). Lysis occurred at 20 ° C for 30 minutes before centrifugation at 30,000 x g for 40 min at 4° C to sediment the cell debris. The supernatant was loaded onto a 60 mL DEAE Fractogel column (Merck, Frankfurt, Germany) and the unbound fraction containing OpdA was collected and dialysed against buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), pH 7.0, overnight. This fraction was then twice loaded onto a 5 mL HiTrap SPFF column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, New Jersey, U.S.A.) equilibrated with 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.0. Bound OpdA was eluted over a linear gradient of 0 to 0.5 M NaCl (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA). SDS-PAGE indicated that OpdA was >95% pure and the overall yield was in excess of 50 mg OpdA per L of growth medium. For storage, the protein was dialysed against 50 mM HEPES, 1 mM CoCl2, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5. In previous studies, there was negligible loss of activity after 8 months of storage at 4ºC.[19]

2.2 Endotoxin removal and assays

The amount of endotoxin present in the OpdA was determined by the Pyrotell Limulus Amebocyte Lysate gel-clot assay (Associates of Cape Cod, Inc., East Falmouth, Massachusetts, U.S.A.). The endotoxin present in the purified OpdA sample was removed by running the protein through an endotoxin removal column (Detoxi-GeL Endotoxon Removing Column, Pierce Protein Research Products, Rockford, Illinois, U.S.A.). After one passage through the column, the endotoxin concentration decreased to 2.1 EU/mg OpdA a reduction of more than 95%. This level of endotoxin concentration corresponds to less than 0.5 ng/mL [20]. This dose of endotoxin was deemed to be safe when injected IV, as Rhesus monkeys have survived treatment with 150 micrograms endotoxin twice daily for 5 days [21]. This quantity of endotoxin also meets the standards of the FDA for endotoxin presence in therapeutics. All solutions used to manufacture, dilute, and administer the OpdA were distilled and autoclaved to ensure no endotoxin presence. Prior to administration, the OpdA was dialyzed overnight at 4ºC against a solution of 150mM NaCl and 20 mM HEPES buffer to remove Co2+ metal ions that were present in the storage buffer to prevent loss of activity and unfolding of OpdA.

2. 3 OpdA PK studies - experimental approach

NHP studies were performed in 4–7 kg male African green monkeys (aka vervets). All animals underwent mandatory 45-day quarantine during which they undergo physical examinations, tuberculosis testing, fecal analysis for bacterial and parasitic pathogens and complete blood counts, serum chemistries and virological screening. All African green monkeys (Chlorocebus sabaceus) were housed at the NEPRC in accordance with the standards of the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and Harvard Medical School’s Animal Care and Use Committee. The animal quarters were under a 12-hour:12-hour light-dark cycle, with fresh water freely available in the home cage. Animals were fed a diet ad libitum of commercial primate food supplemented with fresh fruit daily. Each monkey was weighed immediately before experimentation.

The animals were trained to sit in a primate chair for serial phlebotomy. OpdA at doses of 0.15, 0.45, and 1.2 mg/kg were injected IV into one monkey at each dose (except for 1.2 mg/kg, which was injected into two animals). These doses were chosen based upon preliminary data in rodents. 2mL blood samples were drawn from a saphenous vein catheter immediately before administration of OpdA, and at the following time points after OpdA administration: 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 80, 160, and 320 minutes. The blood was rapidly cooled to 4°C and centrifuged at this temperature for 5 minutes at 2,000 x g. The red blood cells were removed and the plasma frozen at −20° C until analyzed.

To assess the effects of serial OpdA exposures on OpdA kinetics, two animals underwent daily administration of 0.45 or 1.2 mg/kg OpdA IV for 5 days, with a single sample drawn immediately prior to OpdA administration. The animals also underwent a single blood draw 30 minutes after the fifth OpdA dose and the blood samples were handled as above.

A fluorimetric assay of the levels of bioactive OpdA was used to determine the half-life of OpdA in-vivo. For the fluorimetric assay, 20 μl saturating concentrations of coumaphos (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A.) (100μM) were added to 180 μl plasma samples. Formation of the fluorimetric hydrolysis product of coumaphos, chlorferon, at 37ºC was measured in real time using a fluorimeter (Fluoroskan Ascet, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, U.S.A.) using an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and emission intensity at 460 nm according to the method of Harcourt et al [22]. The known specific activity of OpdA for coumaphos was used to calculate residual activity of the enzyme present in the blood.

2.4 Statistical analyses

The pharmacokinetic parameters mean residence time (MRT; which reflects the average length of time an administered drug is retained in vivo) and half-life were obtained by analyzing the clearance data according to a non-compartmental pharmacokinetic model using WinNonlin software (Pharsight, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A.).

3. Results

3.1 Single-dose OpdA kinetics

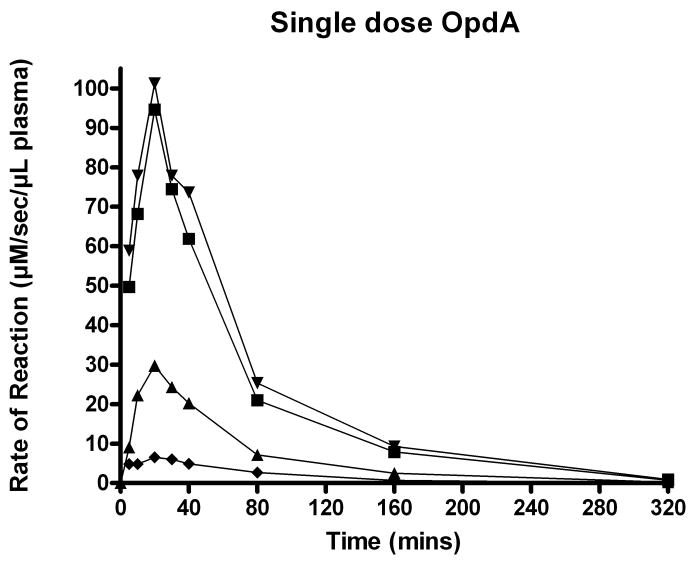

No adverse effects were noted in any animal after the administration of OpdA. In this African green monkey model, the peak enzymatic effect was observed 20 minutes after a single dose of OpdA. Kinetic curves of the 0.15, 0.45, and 1.2 mg/kg OpdA doses are shown in Figure 1. From the 1.2 mg/kg data at time points of 20 minutes and 160 minutes, the OpdA in-vivo half-life was calculated to be 39.9 minutes. Furthermore, at a dose of 1.2 mg/kg, the MRT of OpdA in this Vervet model was 57 minutes.

Figure 1.

Kinetics of coumaphos hydrolysis by a single dose OpdA. ▼ and ■ = 1.2 mg/kg. ▲ =0.45 mg/kg. ◆ =0.15 mg/kg.

The half-life did not significantly change with the dose of OpdA given. At doses of 0.15 and 0.45 mg/kg, the half-life of OpdA was determined to be 43.1 and 38.9 minutes, respectively, and the MRT were 62.1 and 56.0 minutes, respectively.

3.2 Repeat dosing of OpdA

There was very little intrinsic in-vivo coumaphos hydrolytic activity of blood. In the animals subjected to repeated dosing, the residual activity that was measured 24 hours after each OpdA dose increased 5-fold for the 0.45 mg/kg dose and 11-fold for the 1.2 mg/kg dose (Tables 2 and 3). After 5 daily doses of OpdA, the enzymatic activity as measured 30 minutes after the last dose was 50% greater than the activity found after a single dose of 0.45 mg/kg, and 60% greater than after a single dose of 1.2 mg/kg (Tables 2 and 3). This increase in enzymatic activity measured before each daily dose peaked after 2 doses of OpdA and remained elevated even before the fifth dose.

Table 3.

OpdA activity measured before 5 daily doses of 1.2 mg/kg, and 30 minutes after the fifth daily dose.

| Sample drawn Before dose number: | μM/sec/μL plasma |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.076 |

| 2 | 0.348 |

| 3 | 0.831 |

| 4 | 0.709 |

| 5 | 0.400 |

| 30 mins after dose no. 5 | 128.740 |

4. Discussion

Organophosphorus (OP) compounds are the most commonly used agricultural pesticides in the developing world and are responsible for around two-thirds of pesticide fatalities [23]. In North America and Europe, the situation is quite different. A far smaller proportion of the population works in agriculture, and pesticide poisoning is subsequently a much smaller problem. However, the risk of large-scale casualties in the industrialized world from terrorist attacks has already been demonstrated. The 1995 Tokyo sarin attack [24] illustrated the effectiveness of OP nerve gases in enclosed spaces such as the subway system. Highly toxic, and more easily acquired, OP pesticides, such as parathion (rat LD50 2–13 mg/kg), could be similarly used for criminal purposes.

Prophylactic therapy will not be possible for either terrorist attack on civilians or pesticide self-poisoning. Highly effective post-exposure therapy is therefore necessary. Current post-exposure therapy for OP poisoning involves provision of oxygen; rapid administration of an anticholinergic drug such as atropine to antagonize the effects of increased acetylcholine (ACh) levels on muscarinic receptors; an oxime to reactivate the inhibited AChE enzyme before the enzymes is irreversibly inhibited or “aged”; and benzodiazepines to decrease long-term neurocognitive dysfunction [5, 25–27]. The mortality is determined by the speed of poisoning onset and toxicity of the OP, as well as the standard of medical care. The mortality for parathion poisoning in the ICUs of Munich, Germany, where toxicologist specialist services were available, was 40% [6]. In a mass poisoning due to terrorist use or chemical incident it is likely that the mortality would be significantly higher.

These inherent problems with treatment of OP poisoning have led us to investigate OpdA as a possible therapeutic agent for OP poisoning. In this study, the elimination half-life of OpdA in the African green monkey was approximately 40 minutes. Unless used for poisoning by a hydrophilic OP pesticide such as dichlorvos, the short half-life of the current form of OpdA might require that either repeated bolus dosing or a continuous infusion is used. That is, lipophilic OPs such as diazinon and parathion distribute rapidly into deep compartments resulting in a tissue depot of OP pesticide [6]. This tissue depot is not available for hydrolysis by an OP hydrolase. However, for the treatment of acute OP poisoning using an OP hydrolase, it might not be necessary to break down all of the OP. Simply decreasing the OP concentration to a low enough level in the serum that would then allow traditional therapeutic measures to be effective might be sufficient. This idea is supported by data of Eddleston et al. [28]. Using clinical data from patients in Sri Lanka poisoned with dimethoate, they found a strong correlation between dimethoate concentration and survival. Furthermore, all patients with a dimethoate concentration above 750 μM died. Therefore, it may well be enough for a therapeutic OP hydrolase to breakdown some (but not all) of the parent OP in order to convey a survival benefit.

A potential alternative to repeated dosing of OpdA is the modification of OpdA via the attachment of polyethylene glycol (PEG), dextrans, heparin, albumin, and other polymer moieties [29]. PEG is the most common used polymer for such protein modification due to its low toxicity and the wide commercial availability. Such modification could be done with either random PEGylation or by targeting introduced cysteine residues or N terminus-specific PEGylation [30, 31]. PEGylation of native AChEhas been shown to increase its MRT in mice [30], and PEGylated human AChE was found to have a MRT nearly as long as native rhesus macaque AChE in that primate model [32]. Andreopoulos et al [33] investigated the incorporation of PEGyled OPH into hydrogels in an attempt to increase the stability of the enzyme. While not tested in vivo, they found that PEGylation increased both the stability, as well as the activity, of native OPH. Two significant drawbacks to the use of PEGylated OP hydrolases are the technologic difficulties of uniformly PEGylating the enzymes, and the inherent increased cost of doing so [34]. For use in the developing world, where cost restraints are severe, it may be that the use of PEGylated OP hydrolases may not be possible.

Interestingly, in the repeated doses of 0.45 and 1.2 mg/kg experiments there was an increase in coumaphos hydrolyzing activity measured before doses 2 through 5. Furthermore, the enzyme activity measured 30 minutes after dose 5 was significantly greater than the activity measured 30 minutes after the first dose of OpdA. This suggests that pharmacokinetically important antibodies against OpdA are not rapidly developed in this model. This finding has important clinical applicability, as the potential immunologic response to single or repeated doses of bacterial enzymes limited their therapeutic development to some extent.

It is possible that antibodies are formed more than 5 days after dosing with OpdA. However, even if present, such antibodies would be clinically insignificant, as treatment with an OP hydrolase would not likely be necessary that long after poisoning. Furthermore, it is possible that any such antibodies formed would not decrease the activity of OpdA, but rather could increase the clearance of the enzyme.

Published data on most recombinant enzymes do not demonstrate broad substrate specificity towards many of the problematic insecticidal OPs. Since so many different OP pesticides are available around the world, and the causative agent would likely be unknown immediately after exposure, a hydrolase for human use would need to demonstrate effectiveness against a broad range of OPs. The situation will not be very different after intentional contamination of water supplies, since the responsible pesticide is unlikely to be identified for many hours. The problem of specificity could be overcome by using a cocktail of enzymes, or engineered variants of OpdA, with different substrate specificities. For instance, the substrate specificity of OpdA has been altered through directed evolution and rational design in several recent studies [11, 35, 36]

The methods for quantifying macromolecules such as protein therapeutics and the evaluation of protein PK parameters are complicated by numerous factors. These complications include in vivo binding proteins, neutralizing proteins, formation and quantification of metabolites, antibody formation, immunogenicity, and effects due to route and timing of drug delivery [37, 38]. In this study, we used the surrogate of fluorometrically detectable coumaphos hydrolysis to infer OpdA enzymatic activity. This method of detection is sensitive and reproducible [22]. However, this method does not allow the quantification of bound, altered, or neutralized enzyme. As the activity of functional enzyme is ultimately of importance, our method of detection is the most appropriate.

Our study demonstrates that wild-type OpdA has a relatively short half-life in the African green monkey. Repeat bolus administration, a continuous infusion of OpdA, would likely be necessary for all but the most hydrophilic OP pesticides. Further research into post-translational modifications of OpdA to increase half-life and MRT are needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health research grant (R21ES14019) to SBB and by a Primate center base grant (RR00168) to the New England Primate Research Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Colin J Jackson, Email: Colin.jackson@csiro.au, Institut de Biologie Structurale, 38000 Grenoble, France.

Colin Scott, Email: Colin.scott@csiro.au, CSIRO Entolmology, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601, Australia.

Angela Carville, Email: angela_carville@hms.harvard.edu, New England Regional Primate Research Center, Harvard Medical School, Southboro, Massachusetts, 01772 USA.

Keith Mansfield, Email: keith_mansfield@hms.harvard.edu, New England Regional Primate Research Center, Harvard Medical School, Southboro, Massachusetts, 01772 USA.

David L. Ollis, Email: ollis@rsc.anu.edu.au, Research School of Chemistry, Australian National University, Australian Capital Territory 0200, Australia

Steven B. Bird, Email: steven.bird@umassmemorial.org, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 55 Lake Avenue, Worcester, Massachusetts, USA 01655, 508.421.1400 phone, 508.421.1490 fax

References

- 1.Jeyaratnam J. Acute pesticide poisoning: a major global health problem. World Health Stat Q. 1990;43:139–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidell FR. Clinical effects of organophosphorus cholinesterase inhibitors. J Appl Toxicol. 1994;14:111–3. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550140212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thiermann H, Szinicz L, Eyer P, Zilker T, Worek F. Correlation between red blood cell acetylcholinesterase activity and neuromuscular transmission in organophosphate poisoning. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;157–158:345–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird SB, Gaspari RJ, Dickson EW. Early death due to severe organophosphate poisoning is a centrally mediated process. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:295–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eddleston M, Singh S, Buckley N. Organophosphorus poisoning (acute) Clin Evid. 2005:1744–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyer F, Meischner V, Kiderlen D, Thiermann H, Worek F, Haberkorn M, et al. Human parathion poisoning. A toxicokinetic analysis. Toxicol Rev. 2003;22:143–63. doi: 10.2165/00139709-200322030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumas DP, Caldwell SR, Wild JR, Raushel FM. Purification and properties of the phosphotriesterase from Pseudomonas diminuta. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:19659–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashani Y, Rothschild N, Segall Y, Levanon D, Raveh L. Prophylaxis against organophosphate poisoning by an enzyme hydrolysing organophosphorus compounds in mice. Life Sci. 1991;49:367–74. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90444-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vilanova E, Sogorb MA. The role of phosphotriesterases in the detoxication of organophosphorus compounds. Critical reviews in toxicology. 1999;29:21–57. doi: 10.1080/10408449991349177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutherland TD, Horne I, Weir KM, Coppin CW, Williams MR, Selleck M, et al. Enzymatic bioremediation: from enzyme discovery to applications. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;31:817–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.04088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang H, Carr PD, McLoughlin SY, Liu JW, Horne I, Qiu X, et al. Evolution of an organophosphate-degrading enzyme: a comparison of natural and directed evolution. Protein Eng. 2003;16:135–45. doi: 10.1093/proeng/gzg013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horne I, Sutherland TD, Harcourt RL, Russell RJ, Oakeshott JG. Identification of an opd (organophosphate degradation) gene in an Agrobacterium isolate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:3371–6. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.7.3371-3376.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson CJ, Foo JL, Tokuriki N, Afriat L, Carr PD, Kim HK, et al. Conformational sampling, catalysis, and evolution of the bacterial phosphotriesterase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:21631–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907548106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson RM, Pantelidis S, Rose HR, Kotsonis SE. Degradation of nerve agents by an organophosphate-degrading agent (OpdA) J Hazard Mater. 2008;157:308–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.12.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krasovskii GN. Extrapolation of experimental data from animals to man. Environmental health perspectives. 1976;13:51–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.761351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes GP, Hilliard JK, Klontz KC, Rupert AH, Schindler CM, Parrish E, et al. B virus (Herpesvirus simiae) infection in humans: epidemiologic investigation of a cluster. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:833–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-11-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonough JH, Despain KE, McMonagle JD, Benito MA, Pannell MM, Evans JA. Aberdeen Proving Ground: U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense. 2004. The intramuscular toxicity of soman in the African green monkey. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neylon C, Brown SE, Kralicek AV, Miles CS, Love CA, Dixon NE. Interaction of the Escherichia coli replication terminator protein (Tus) with DNA: a model derived from DNA-binding studies of mutant proteins by surface plasmon resonance. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11989–99. doi: 10.1021/bi001174w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bird SB, Sutherland TD, Gresham C, Oakeshott J, Scott C, Eddleston M. OpdA, a bacterial organophosphorus hydrolase, prevents lethality in rats after poisoning with highly toxic organophosphorus pesticides. Toxicology. 2008;247:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petsch D, Anspach FB. Endotoxin removal from protein solutions. J Biotechnol. 2000;76:97–119. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(99)00185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao E, Xia-Zhang L, Barth A, Zhu J, Ferin M. Stress and the menstrual cycle: relevance of cycle quality in the short- and long-term response to a 5-day endotoxin challenge during the follicular phase in the rhesus monkey. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1998;83:2454–60. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.7.4926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harcourt RL, Horne I, Sutherland TD, Hammock BD, Russell RJ, Oakeshott JG. Development of a simple and sensitive fluorimetric method for isolation of coumaphos-hydrolysing bacteria. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2002;34:263–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2002.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eddleston M, Phillips MR. Self poisoning with pesticides. Bmj. 2004;328:42–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7430.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okumura T, Takasu N, Ishimatsu S, Miyanoki S, Mitsuhashi A, Kumada K, et al. Report on 640 victims of the Tokyo subway sarin attack. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:129–35. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballantyne B, Marrs TC. Clinical and experimental toxicology of organophosphate and carbamates. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 1992. Overview of the biological and clinical aspects of organophosphates and carbamates; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sivilotti ML, Bird SB, Lo JC, Dickson EW. Multiple centrally acting antidotes protect against severe organophosphate toxicity. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:359–64. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eddleston M, Dawson A, Karalliedde L, Dissanayake W, Hittarage A, Azher S, et al. Early management after self-poisoning with an organophosphorus or carbamate pesticide - a treatment protocol for junior doctors. Crit Care. 2004;8:R391–7. doi: 10.1186/cc2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eddleston M, Eyer P, Worek F, Rezvi Sheriff MH, Buckley NA. Predicting outcome using butyrylcholinesterase activity in organophosphorus pesticide self-poisoning. Qjm. 2008 doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcn026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monfardini C, Veronese FM. Stabilization of substances in circulation. Bioconjug Chem. 1998;9:418–50. doi: 10.1021/bc970184f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen O, Kronman C, Lazar A, Velan B, Shafferman A. Controlled concealment of exposed clearance and immunogenic domains by site-specific polyethylene glycol attachment to acetylcholinesterase hypolysine mutants. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35491–501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704785200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen O, Kronman C, Chitlaru T, Ordentlich A, Velan B, Shafferman A. Effect of chemical modification of recombinant human acetylcholinesterase by polyethylene glycol on its circulatory longevity. The Biochemical journal. 2001;357:795–802. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen O, Kronman C, Velan B, Shafferman A. Amino acid domains control the circulatory residence time of primate acetylcholinesterases in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) The Biochemical journal. 2004;378:117–28. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andreopoulos FM, Roberts MJ, Bentley MD, Harris JM, Beckman EJ, Russell AJ. Photoimmobilization of organophosphorus hydrolase within a PEG-based hydrogel. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 1999;65:579–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bailon P, Won CY. PEG-modified biopharmaceuticals. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:1–16. doi: 10.1517/17425240802650568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson CJ, Weir K, Herlt A, Khurana J, Sutherland TD, Horne I, et al. Structure-based rational design of a phosphotriesterase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:5153–6. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00629-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson CJ, Foo JL, Tokuriki N, Afriat L, Carr PD, Kim HK, et al. Conformational sampling, catalysis, and evolution of the bacterial phosphotriesterase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907548106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahmood I, Green MD. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations in the development of therapeutic proteins. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 2005;44:331–47. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banga AK. Therapeutic Peptides and Proteins: Formulation, Processing, and Delivery Systems. Philadelphia: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown K. Phosphotriesterases of Flavobacterium sp. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 1980;12:105–12. [Google Scholar]