Abstract

Background and Aims

There is substantial evidence that gut barrier failure is associated with distant organ injury and systemic inflammation. After major trauma or stress, the factors and mechanisms involved in gut injury are unknown. Our primary hypothesis is that loss of the intestinal mucus layer will result in injury of the normal gut that is exacerbated by the presence of luminal pancreatic proteases. Our secondary hypothesis is that the injury produced in the gut will result in the production of biologically active mesenteric lymph and consequently distant organ (i.e., lung) injury.

Methods

To test this hypothesis, five groups of rats were studied: 1) un-instrumented naïve rats; 2) control rats, in which a ligated segment of distal ileum was filled with saline; 3) rats with pancreatic proteases placed in their distal ileal segments; 4) rats with the mucolytic N-acetylcysteine (NAC) placed in their distal ileal segments and 5) rats exposed to NAC and pancreatic proteases in their ileal segments. The potential systemic consequences of gut injury induced by NAC and proteases were assessed by measuring the biologic activity of mesenteric lymph as well as gut-induced lung injury.

Results

Exposure of the normal intestine to NAC, but not saline or proteases, led to increased gut permeability, loss of mucus hydrophobicity, a decrease in the mucus layer as well as morphologic evidence of villous injury. Although proteases themselves did not cause gut injury, the combination of pancreatic proteases with NAC caused more severe injury than NAC alone, suggesting that once the mucus barrier is impaired, luminal proteases can injure the now vulnerable gut. Since comparable levels of gut injury caused by systemic insults are associated with gut-induced lung injury which is mediated by biologically active factors in mesenteric lymph, we next tested whether this local model of gut injury would produce active mesenteric lymph or lead to lung injury. It did not, suggesting that gut injury by itself may not be sufficient to induce distant organ dysfunction.

Conclusions

Loss of the intestinal mucus layer, especially in the presence of intra -luminal pancreatic proteases, is sufficient to lead to injury and barrier dysfunction of the otherwise normal intestine, but not to produce gut-induced distant organ dysfunction.

Keywords: Mucus hydrophobicity, mucolytic N-acetylcysteine (NAC), luminal pancreatic proteases, gut permeability

Introduction

Currently, development of the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) has emerged as the most common cause of death in surgical and many medical intensive care unit patients1. Consequently, intensive research has been devoted to understanding the mechanisms contributing to MODS as well as its components, the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)1. One pathophysiological process thought to be involved is related to gut injury and has been termed the gut hypothesis of MODS. This theory proposes that loss of gut barrier function by the stressed intestine results in the escape of bacteria and/or gut-derived products from the gut to the systemic circulation where they induce, accentuate or perpetuate SIRS, ARDS and MODS2. This hypothesis is based on preclinical and clinical studies showing that many stress states are associated with splanchnic hypoperfusion and loss of gut barrier function, and that increased gut permeability is associated with ARDS and MODS development3. The notion that loss of gut barrier function can lead to adverse clinical events is not surprising, given the intraluminal presence of vast numbers of bacteria and their products and digestive enzymes capable of auto-digesting any of the host’s cells in which they come into direct contact4. Consequently, the gut barrier needs to prevent digestive enzymes from coming into direct contact with the gut epithelium, as well as effectively limit bacterial invasion. Under normal physiologic conditions, these potential problems have been solved to a large degree by having a hydrophobic unstirred mucus layer that is tightly adherent to the gut epithelium5,6; this layer limits the ability of hydrophilic digestive enzymes to come into direct contact with the villi’s epithelial lining and serves as a barrier to bacterial invasion. In fact, even though the epithelium contains tight junctions which limit the passage of bacteria and other luminal factors across the mucosal barrier, it is a less effective barrier than the unstirred mucus layer2,7. In spite of its critical role as a barrier, little work has focused on the relative importance of the mucus layer in splanchnic ischemia-reperfusion and a resultant loss of gut barrier function. Our recent work in trauma-hemorrhage models2,6, 8, 9 indicates loss of the unstirred mucus layer’s contribution to SIRS, and both our later work11,12, as well as that from Schmid-Schoenbein’s laboratory10, implicates intraluminal pancreatic proteases in the pathogenesis of gut-origin MODS. Given the important protective role of the mucus layer and the potentially tissue injurious effects of pancreatic proteases, we tested the hypothesis that loss of the intestinal mucus layer would result in injury of the normal, non-stressed gut, and that the magnitude of gut injury would be exacerbated by the presence of digestive enzymes within the intestinal lumen. In addition, we investigated the potential systemic consequences of these local gut events in producing distant organ injury.

Materials and Methods

Animal

Sprague-Dawley male rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), 9–11 weeks old, weighing 300–400 g, were housed under barrier-sustained conditions and kept at 25°C with 12-hour light-dark cycles. They were provided with chow and water ad libitum and were not fasted prior to the experiments. All animals were maintained according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and all animal protocols were approved by the New Jersey Medical School Animal Care Committee.

Experimental Design

In the first set of experiments, we tested the hypothesis that loss of the intestinal mucus layer would be associated with gut injury and dysfunction and that this level of gut injury/dysfunction would be exacerbated by the presence of intra-luminal pancreatic proteases. To test this hypothesis, rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal pentobarbital (50 mg/kg). During the injection of saline, NAC or NAC + proteases, the 3 hr. incubation time, during lymph collection and for the lung injury experiments, additional pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally injected to maintain adequate anesthesia, defined as no motor response to a painful stimulus (pinching of the hindpaws). Each rat underwent a 3-cm midline laparotomy and a 30-cm segment of the ileum was identified, beginning 2 cm from the ileocecal junction. This segment was ligated at each end, enterotomies were made just inside the ligature and the gut segment was flushed with normal saline. Both segment ends were ligated, following which either saline or the mucolytic NAC (10%) was injected into the gut segment and allowed to remain in the lumen for 10 min. At this point, the gut segment was flushed again, re-ligated and the lumen was filled with saline or a solution containing pancreatic proteases following which the laparotomy incision was closed. This resulted in 5 experimental groups, with 6–10 rats/group. These groups were: 1) naïve (no gut manipulation); 2) saline-saline; 3) saline-proteases; 4) NAC-saline and 5) NAC-proteases. After 3 hours, the incision was re-opened sterilely and intestinal tissue was collected for analysis of gut and mucus injury and dysfunction.

The concentration of NAC used and the time of exposure were based on our earlier studies showing that 10 minutes of exposure of the normal intestine to a 10% NAC solution is sufficient to injure the mucus layer by increasing gut permeability and decreasing gut mucosal hydrophobicity 6. The pancreatic protease solution was composed of 1 mg/mL of tryspin and chymotrypsin suspended in saline; this is the physiologic enzyme concentration in the rat small intestine, as previously reported13.

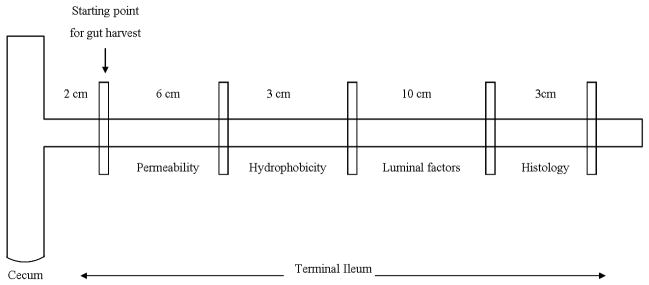

As shown in Figure 1, specific areas of the ileum were harvested for physiologic measurements of intestinal barrier function as well as morphologic evidence of villus injury and injury to the mucus layer. Specifically, gut permeability was measured using the everted gut sac model. Hydrophobicity, a marker of barrier function of the mucus layer, was determined by measuring the contact angle between a drop of saline and the gut segment with a goniometer. Histologic assessment of gut injury and of mucus layer disruption was assessed using Carnoy’s fixative and alcian blue staining. Lastly, cellular damage was further quantified by measuring the amounts of protein (BCA Protein Assay Kit) and DNA (diphenylamine assay) present in the gut lumen.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the specific segments of the terminal ileum that were harvested for physiologic and morphologic studies of intestinal barrier function, villus injury and mucus layer function (hydrophobicity).

Since conditions such as hemorrhagic shock, burn injury and other gut ischemia-reperfusion injuries are associated with distant organ, especially lung, injury, which appears to be related to gut-derived factors reaching the systemic circulation via the intestinal (mesenteric) lymphatics14, we carried out two additional experiments. In the first experiment, mesenteric lymph was collected from rats whose intestines were exposed to saline, NAC, or NAC plus proteases as previously described15. Briefly, the mesenteric lymph duct of each rat was cannulated with Silastic tubing, the effluent lymph was collected in eppendorf tubes on ice in 2-hr increments, centrifuged, aliquoted and stored at −80°C until assayed. The mesenteric lymph samples were tested for biologic activity by measuring their ability to kill endothelial cells or activate neutrophils. In the second set of experiments, gut-induced lung injury was assessed 3 hrs after the rat intestines were exposed to saline, NAC or NAC plus proteases by measuring lung permeability to Evan’s blue dye as previously described15.

In vitro gut permeability

Gut permeability was measured using the everted gut sac method as previously described6. Briefly, a 6-cm segment of ileum from each rat was flushed with normal saline, made into an everted gut sac and its permeability determined using the 4-kd fluorescent-labeled Dextran (FD-4) permeability probe. Modified Krebs-Henseleit bicarbonate buffer (KHBB, pH 7.4) was injected into the gut segment to distend it, suspended in KHBB solution with added FD-4 (20 mg/mL) and incubated for 30 min. at 37°C. The mucosal and serosal fluid samples were aspirated, centrifuged and their fluorescences were measured at an excitation of 492 nm and an emission of 515 nm. Gut permeability was expressed as the clearance of FD4 from the mucosa to the serosa in nL/min/cm2. The calculations used were:

where M=the mass of FD4 in ng in the gut sac, [FD4]serosa is the concentration of FD4 in the gut sac at the end of the 30 min. incubation period, 0.5 is the volume of FD4 in the gut sac in cc, F is the flux of FD4 across the serosa, A is the mucosal surface area (πld), C is the clearance of FD4 and [FD4]mucosa is the concentration of FD4 in the beaker before the 30 min. incubation period.

Hydrophobicity

The hydrophobicity of the luminal surface, which reflects the barrier function of the mucus layer, was measured as previously described6. Briefly, a 3-cm segment of gut was opened longitudinally on a glass slide allowed to dry and mounted on a styrofoam stand on the microscope stage of a goniometer. A 5-μL droplet of saline was placed on the specimen, the contact angle was measured by the goniometer and the hydrophobicity was determined by the machine’s software. The contact angle is the angle between where the solid gut segment meets the liquid droplet and the air and the tangent to this interface point. The larger the contact angle, the greater the hydrophobicity of the sample.

Morphology

A 3-cm segment of terminal ileum was harvested, fixed in Carnoy’s fixative and stained with 3% alcian blue for mucus visualization16. Four-μm sections of gut were fixed to slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for villus injury determinations. The percentage of mucosal coverage by the mucus layer and the number of injured villi were calculated under light microscopy in a blinded fashion.

Luminal markers of gut injury

Luminal supernatants were obtained after the ileum was harvested by gently flushing out the luminal contents with a small amount of saline and homogenizing them. They were then used to perform assays to determine the luminal DNA and protein concentrations. Luminal DNA was measured using a diphenylamine (DPA) assay. Briefly, this method involves release of DNA, centrifugation yielding intact and fragmented DNA, DNA precipitation, hydrolysis and colorimetrical quantitation with DPA (binds to deoxyribose). Luminal protein was measured with the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, 23225). Briefly, colorimetrical quantitation, involving the reduction of copper that binds to BCA, produces a purple color.

Measurement of lymph toxicity

The ability of the mesenteric lymph samples to kill endothelial cells was measured using the MTT viability assay as previously described15. Briefly, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) were seeded onto 96-well plates to form a monolayer. The HUVECs were then incubated with the various lymph samples at a 5% v/v concentration in medium; 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) served as the control. After an 18-hr incubation period at 37°C with 5% CO2, 90 μL of phenol red-free medium and 10 μL 0.5% MTT assay solution (Sigma) were added to each well following medium removal. Cells were incubated for 3 hr at 37°C, then 100 μL MTT solubilization solution was added per well, and mixed. Plates were read at 570 nm. Cell viability is expressed as percent of the FBS-medium.

Measurement of lymph-induced PMN respiratory burst

To determine the PMN activating ability of the mesenteric lymph, 400 μL of heparinized whole blood were incubated with 400 μL of medium, followed by lysis of the RBCs. WBC pellets (2.8–3.6 ×104 WBC) were washed twice, re-suspended in 400 μL Hank’s medium, 5% lymph v/v was added and samples were incubated for 5 min. Dihydrorhodamine (15 mg/mL) was then added, incubated for 5 min and followed by phorbol myristate acetate (90 ng/mL) to stimulate the PMNs. The PMNs (2.8–3.6 × 104) were incubated for 15 min. The PMN respiratory burst was measured by flow cytometry.

Measurement of Lung Permeability (Evan’s blue dye)

Lung permeability to Evan’s blue dye was performed, as previously described15. Briefly, 3 hrs after the guts were exposed to saline, NAC or NAC plus proteases, 1% Evan’s blue dye was injected intravenously and circulated for 5 min, following which a plasma Evan’s blue dye reference sample was taken. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was then collected, centrifuged and the concentration of Evan’s blue dye in the BALF supernatant and plasma were spectrophotometrically measured at 620 nm. The concentration of the Evan’s blue dye in the BALF was expressed as the percentage of the dye in the plasma. Increases in lung permeability are reflected in higher BALF to plasma dye ratios.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Continuous data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance, with a follow-up test using the Kruskal-Wallis test, assuming a non-parametric distribution or student t-test using GraphPad Prism 4 software. Probabilities less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

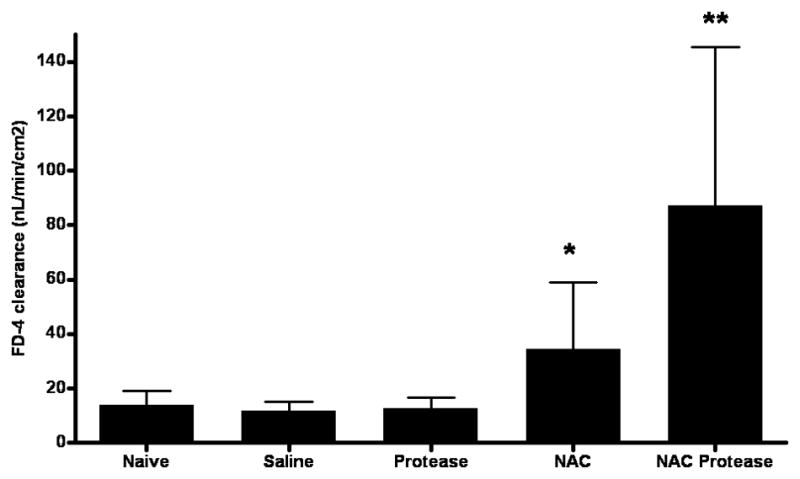

Intestinal barrier function, as reflected in the permeability of the everted gut sacs, was not significantly increased by the intestinal manipulations, since the gut permeability of the naive rats was similar to those animals whose intestines were filled with saline (Figure 2). Likewise, the addition of physiologic concentrations of pancreatic proteases to the ligated ileal intestinal segment did not increase gut permeability. In contrast, a brief 10 minute exposure of the normal gut to the mucolytic NAC was associated with a significant and approximately two-fold increase in gut permeability (Figure 2). Although proteases by themselves were not sufficient to increase gut permeability, the combination of NAC followed by proteases was associated with a further increase in gut permeability, such that the combination of NAC plus proteases led to an increase in gut permeability that was more than two-fold that observed with NAC alone (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of pancreatic proteases and NAC, alone and in combination, on intestinal permeability as reflected in the clearance of the permeability probe FD-4. Data are represented by mean ± SD. * p<0.05 vs. naive, saline and protease groups; ** p<0.01 vs. all other groups. n=6–10 rats/group.

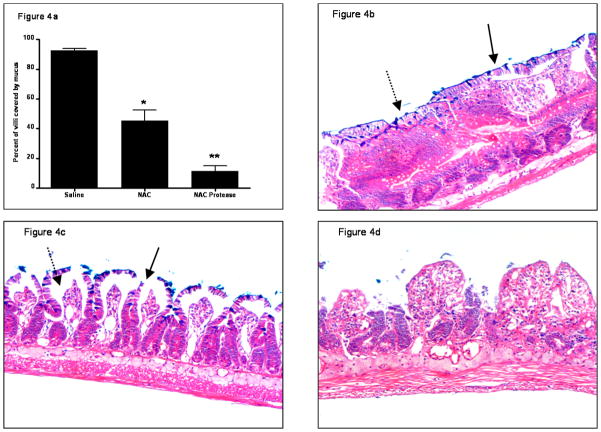

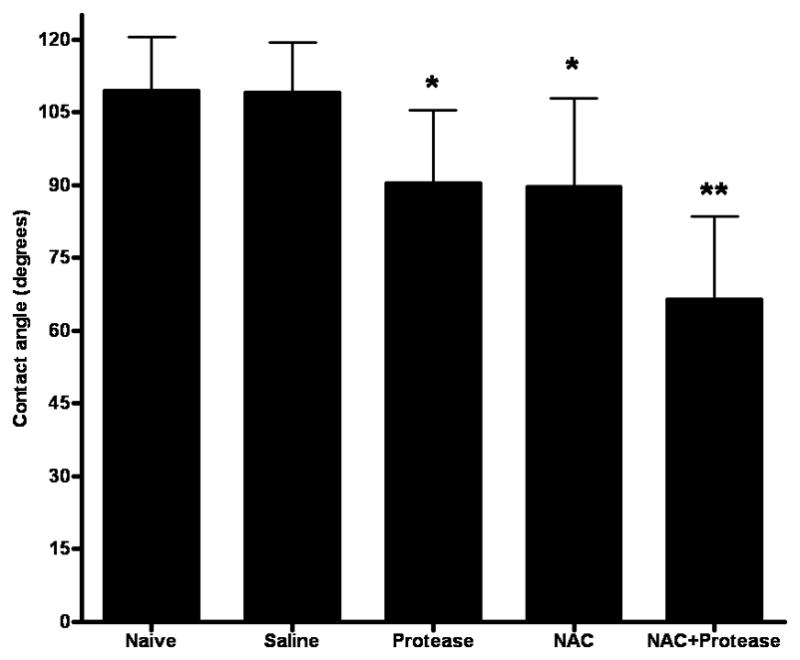

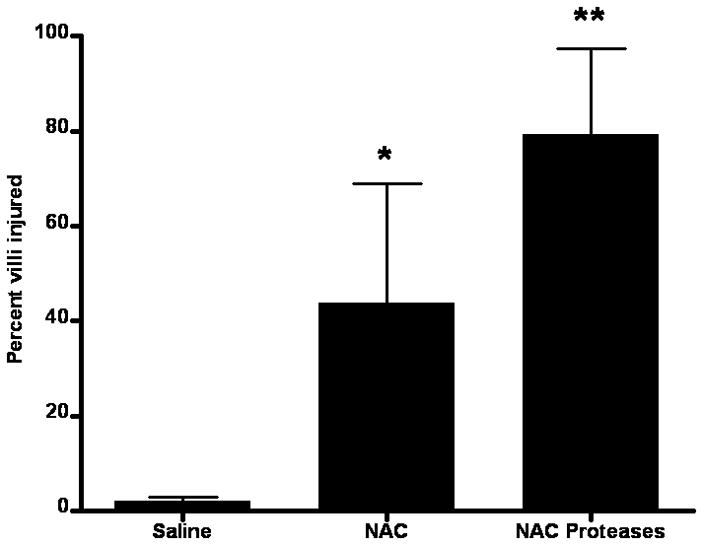

Since the intestinal unstirred mucus layer contributes to gut barrier function through its hydrophobic properties6, we assessed the effect of the various experimental manipulations on intestinal hydrophobicity (Figure 3). There was no difference in intestinal hydrophobicity between the naive and saline groups indicating that gut handling does not affect the hydrophobic properties of the gut. However, exposure of the gut segments to NAC or proteases decreased hydrophobicity and, as was seen with the everted gut sac permeability studies, the greatest decrease in hydrophobicity was observed with the combination of NAC plus proteases (Figure 3). Morphologic assessment of the mucus layer was consistent with the hydrophobicity data, since the percent of the intestinal mucosa covered by mucus was less in the NAC than the saline group and was further reduced by the combination of NAC plus proteases (Figure 4a). This decrease in the mucus layer is illustrated in Figure 4b–d, where the intact mucus layer observed in the saline-treated rats (Figure 4b) is partially reduced in the NAC-treated rats (Figure 4c) and almost completely destroyed in the NAC plus protease group (Figure 4d). Also, as shown in Figure 4 and quantified in Figure 5, the villus structure is preserved in the saline-treated rats, partially lost in the NAC group and almost completely destroyed in the NAC plus protease group. In fact, there was a direct correlation between the magnitude of mucus loss and villus injury (r = 0.53; p = 0.02).

Figure 3.

Intestinal hydrophobicity, as measured by the contact angle of the gut mucosa, decreases when either pancreatic proteases or NAC is added to the gut lumen and decreases even further when the two are combined. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. * p<0.0001 vs. all other groups. ** p<0.0001 vs. all other groups. n=6–10 rats/group.

Figure 4.

(A) Mucus coverage of the intestinal mucosa decreases after the introduction of intra-luminal NAC or NAC + proteases. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of the percent of the intestinal villi covered with mucus. * p<0.005 vs. all other groups; ** p<0.005 vs. all other groups. n=4/group.

(B) Representative histologic section of normal rat gut 3 hrs after the intra-luminal addition of saline that was stained with Alcian blue plus hematoxylin and eosoin. The adherent mucus layer is readily visible (solid arrow), the villi are intact and goblet cells containing mucus are also apparent (dashed arrow). (Mucus stains blue-violet.) 40× magnification.

(C) Representative histologic section of the normal rat gut 3 hrs after the addition of intra-luminal NAC. The mucus layer has been disrupted (solid arrow) and there is edema within the villi (dashed arrow). 40× magnification.

(D) Representative histologic section of the normal rat gut 3 hrs after the intra-luminal addition of NAC + proteases. The combination of NAC and proteases caused a loss of villus integrity as well as an absence of the mucus layer. 40× magnification.

Figure 5.

Percentage of intestinal villi injured after the introduction of intra-luminal saline, NAC or NAC + proteases. Data are expressed as percent ± SD. * p <0.05 vs. all other groups. ** p <0.01 vs. all other groups. n=8–9/group.

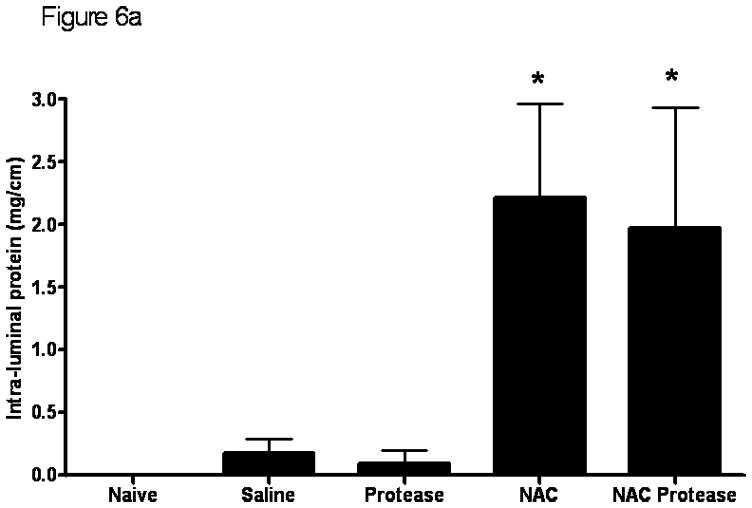

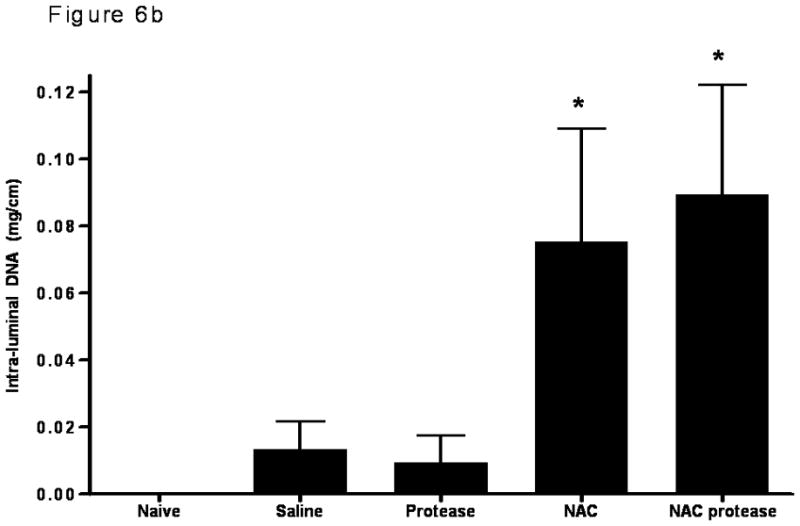

Measurements of luminal protein and DNA are consistent with the morphologic studies and showed that NAC alone as well as NAC plus proteases are associated with increased amounts of protein and DNA in the gut lumen indicating an increase in cellular injury (Figure 6). The observation that there was no difference among the naive, saline and protease only groups indicates that neither gut handling nor exposure to proteases alone was sufficient to cause an increase in cellular damage.

Figure 6.

The luminal protein concentration (A) as well as the intra-luminal DNA concentration (B) were significantly increased when the mucus layer was removed by NAC or when NAC was combined with proteases. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. * p <0.005 vs. all other groups. n=6–7 rats/group.

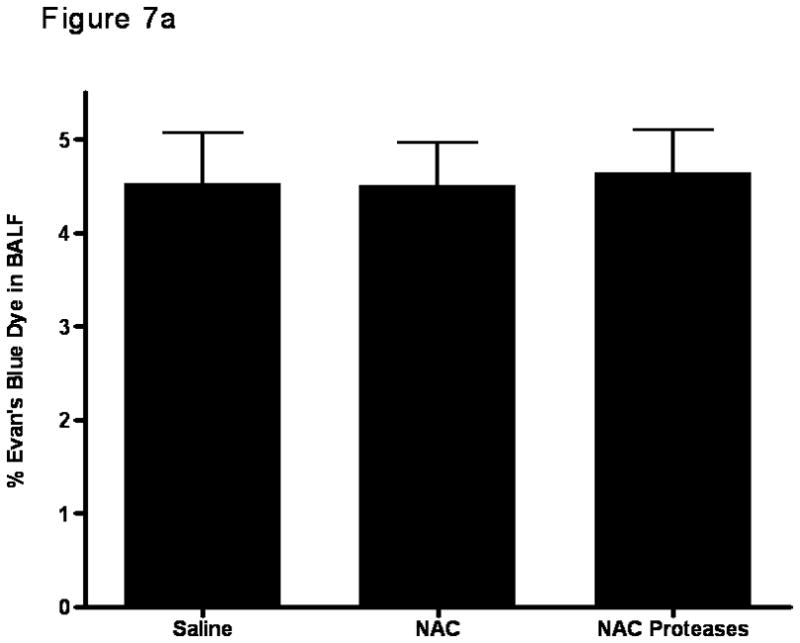

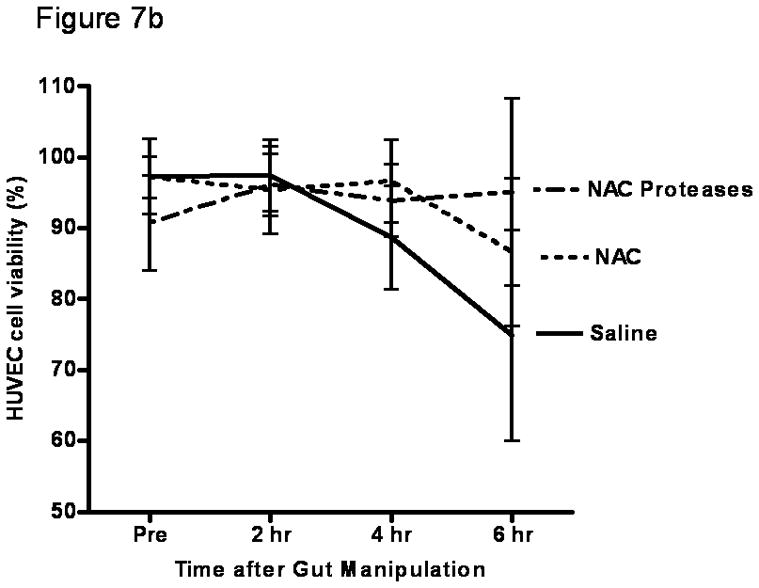

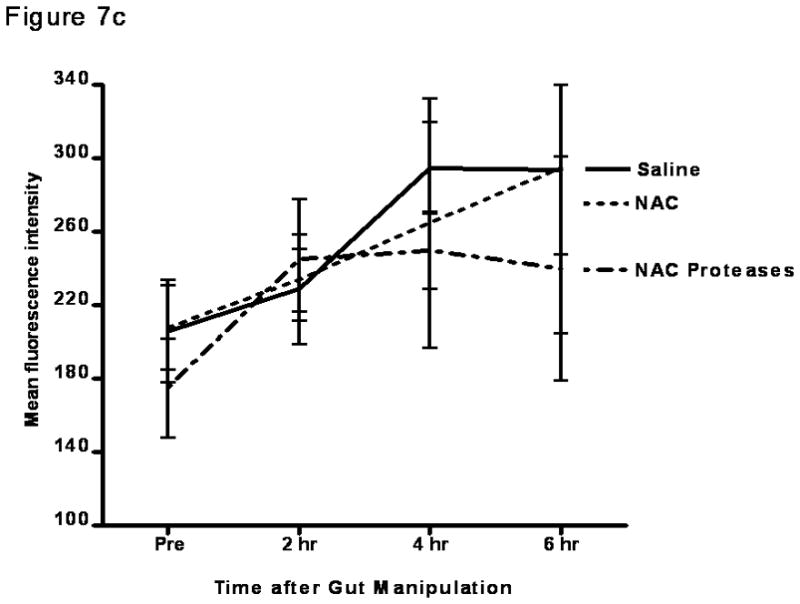

Since the magnitude of gut injury observed in the NAC and the NAC plus protease groups of rats was similar in magnitude to that observed in systemic insults associated with gut ischemia-reperfusion injury8, where gut-induced lung injury occurs, we next tested whether local gut injury induced by NAC or NAC plus proteases would lead to lung injury. Additionally, since gut-induced lung injury after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion insults appears to be mediated by biologically active gut-derived factors in mesenteric lymph17, our next goal was to test the in vitro biologic activity of mesenteric lymph collected from these groups. Because the naive and protease only groups were not different from the saline group with respect to gut permeability or to an increase in gut injury as evident from an increase in luminal factors, those groups were not tested for lung injury or morphologic injury and the saline group served as the control. To accomplish this goal, mesenteric lymph collected before gut manipulation and at 2 hrs, 4 hrs and 6 hrs after incubation of the intestines with saline, NAC or NAC plus proteases were tested for their ability to kill endothelial cells and/or activate neutrophils. Though NAC and NAC plus proteases led to increased gut permeability and gut injury, there was no subsequent lung injury, as reflected in increased lung permeability to Evan’s blue dye (p=0.83; Figure 7a). This failure of NAC- or NAC plus protease-induced gut injury to cause lung injury appears to be related to the fact that mesenteric lymph obtained from these animals did not have tissue injurious (toxicity for endothelial cells [p=0.87]; Figure 7b) or proinflammatory activity as reflected in neutrophil activating ability ([p=0.79]; Figure 7c), as had been observed in systemic conditions associated with gut-induced lung injury, such as hemorrhagic shock15,17. Therefore, even though NAC and NAC plus proteases are sufficient insults to cause local gut injury, they are not sufficient to cause distant lung injury or induce the production of biologically active mesenteric lymph.

Figure 7.

A) Lung permeability in rats was not increased after the addition of intra-luminal NAC or the combination of NAC and proteases. Data are expressed as mean ± SD percent of EBD in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). p=0.83. n=5–6 rats/group.

B) Modulation of the intestinal mucus layer does not result in the production of cytotoxic mesenteric lymph as measured by MTT assay. Data are expressed as mean ± SD percent cell viability. p=0.87. n=5–6 rats/group.

C) Modulation of the intestinal mucus layer does not result in the production of proinflammatory mesenteric lymph as measured by PMN activation. Data are expressed as mean ± SD mean fluorescence intensity. p=0.79. n=5–6 rats/group.

Discussion

The current study shows that loss of the mucus layer, especially in the presence of pancreatic proteases, is sufficient to induce gut injury and increase gut permeability. To our knowledge this is the first time that the interactions between loss of the protective mucus layer and the potentially tissue-injurious effects of luminal pancreatic proteases have been studied in the normal intestine. This observation that removal of the mucus layer is sufficient to cause profound changes in gut morphology and function, which can be exacerbated by normal intraluminal digestive enzymes, may have potential biologic and clinical significance in conditions where the gut is stressed, such as occurs with splanchnic ischemia. Thus, these current observations build on our recent studies showing that pancreatic proteases are necessary for the development of gut injury and gut-induced distant organ injury in both global gut ischemia-reperfusion models, such as trauma-hemorrhagic shock (T/HS)11 as well as in a localized gut ischemia-reperfusion injury model, like superior mesenteric artery occlusion (SMAO)10. Specifically, these studies documented that T/HS as well as SMAO-induced lung injury and neutrophil activation was abrogated by chemical neutralization of pancreatic proteases within the lumen of the gut as well as by preventing pancreatic proteases from reaching the gut lumen through pancreatic duct ligation9,11,12. Furthermore, pancreatic duct ligation not only prevented distant organ injury after T/HS but was also associated with preservation of the intestinal mucus layer9. Thus, the results obtained from these gut ischemia-reperfusion models indicated that pancreatic proteases are necessary for both gut injury and the development of the systemic consequences of gut injury. However, based on this previous work, it appeared likely that an important step in pancreatic protease-induced gut injury in intestinal ischemia-reperfusion models is related to the loss of the protective mucus layer, since loss of the mucus layer would allow intra-luminal digestive enzymes to come into direct contact with the intestinal epithelium and thereby induce a tissue-injurious response. This hypothesis is supported by the current studies documenting that luminal pancreatic proteases do not injure the normal gut mucosa unless the mucus layer is removed and thereby provides proof-of-principle evidence that the mucus layer is a key factor in protecting the gut from injury by endogenous intraluminal proteases. This notion is further supported by previous work showing that the hydrophobic properties of the intestine as well as the mucus layer are rapidly lost after gut ischemia6 and that this loss of gut hydrophobicity and the mucus layer correlates with gut injury6,8. Furthermore, recent studies have documented that the intraluminal administration of high molecular weight polyethylene glycol, as a mucus surrogate, protected the gut as well as abrogated gut-origin sepsis18, suggesting that the use of enteral mucus surrogates may be of benefit by functioning as a protective barrier against injury.

Since localized and global ischemia-reperfusion-mediated gut injury states are associated with the induction of lung injury, a SIRS state and even MODS, we next investigated if the localized gut injury produced in the otherwise normal gut by mucus loss with or without the addition of pancreatic proteases was sufficient to induce lung injury. Additionally, since our studies have implicated intestinal lymph exiting the injured gut as the key factor leading to lung injury and neutrophil activation in both rodents and larger animal models15,19–21, we also measured the biologic activity of mesenteric lymph. These studies indicated that local gut injury produced by the removal of the mucus layer, even in the presence of pancreatic proteases, was not sufficient to induce lung injury or induce biologically active mesenteric lymph. Thus, it appears that the effects of loss of the mucus layer, even in combination with pancreatic proteases, in the absence of a systemic insult, were not sufficient to cause distant organ injury or induce the production of tissue-injurious or pro-inflammatory mesenteric lymph. This observation is in stark contrast to what is observed with comparable levels of gut injury induced by T/HS or SMAO where the intestine experiences an ischemia-reperfusion insult plus loss of the mucus layer15,19. This dissociation of gut injury from distant organ injury and the production of biologically active mesenteric lymph observed in the current study suggests that the mechanism by which the gut is injured may be important in the pathogenesis of gut-origin MODS. That is, gut injury induced by mucus loss and exposure to pancreatic proteases of the otherwise normal gut is not sufficient to produce the gut-derived factors carried in mesenteric lymph that lead to distant organ injury observed in conditions associated with gut injury due to intestinal ischemia-reperfusion insults9,10. Therefore, these data provide new insights into the mechanisms of gut-induced MODS whereby both a local insult, in the form of loss of the mucus layer, as well as a systemic insult, such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, appear to be required for the production of toxic factors in the mesenteric lymph and the development of distant organ injury. Although the mechanisms by which an intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury lead to loss of the intestinal mucus layer is unknown, one possible mechanism could involve oxidative damage of the mucin molecules by free radicals generated during the ischemia-reperfusion period. This notion is supported by studies showing that oxidatively damaged mucin is unable to form a hydrophobic gel22 and this loss of hydrophobicity would allow pancreatic proteases within the lumen of the gut easier access to the epithelial layer22. Furthermore, damaged mucin molecules are more susceptible to proteolytic cleavage by pancreatic proteases23, which could promote further loss of the mucus layer and consequently exacerbate gut injury. Thus it is possible that it is the interactions of ischemia-reperfusion-induced free radicals and other systemic pro-inflammatory factors and cells with gut luminal factors, such as pancreatic proteases as well as bacteria and their products, that act together to produce the biologically active components of shock-trauma mesenteric lymph.

This study does have limitations. One important limitation is the fact that the only proteases tested for their ability to cause gut injury were the pancreatic proteases trypsin and chymotrypsin. Since the gut contains other digestive enzymes, it is possible that these other digestive enzymes, in addition to the pancreatic proteases tested, may have important roles in gut injury during gut ischemia-reperfusion states. Additionally, since non-pancreatic proteases were not tested in this work, the observations made with trypsin and chymotrypsin may or may not be specific to these proteases. That is, other proteases may have the ability to cause gut injury in this model system. A second potential limitation of the study is that NAC, while being a mucolytic, also has antioxidant properties. Since oxidants are associated with ischemia-reperfusion injury and may also be involved in protease-mediated gut injury or gut-induced distant organ injury, it is possible that NAC’s anti-oxidant properties may have attenuated the potential adverse effects of increased gut leak in the presence of digestive enzymes on the production of biologically-active mesenteric lymph as well as distant organ injury. That is, although the total time of intestinal contact with the NAC was just 10 minutes, the total amount of NAC (~750 mg/kg) placed into the lumen of the intestine was comparable to doses of NAC used to limit ischemia-reperfusion-mediated injury in a number of organ systems24,25,26.

In summary, the hydrophobic property of mucus appears to be a key feature of the mucus layer that prevents the hydrophilic pancreatic proteases from directly coming into contact with and thereby injuring the intestinal epithelium. Consequently, we believe that studies investigating the mechanisms of ischemia-reperfusion injury of the gut as well as gut-origin MODS need to focus on both the systemic effects of the ischemia-reperfusion process, such as oxidants and other pro-inflammatory factors, as well as intestinal lumen factors, such as the intestinal mucus layer, pancreatic proteases and the gut microbial flora2. That is, it appears that the full effect of gut ischemia-reperfusion insults results from both the systemic and the luminal compartments, since T/HS or SMAO-induced MODS requires luminal pancreatic proteases and is associated with loss of the mucus layer8–12,18, while mucus removal, even in the presence of pancreatic proteases, is not sufficient to cause gut-induced lung injury or the production of biologically active mesenteric lymph even though significant gut injury is induced.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants GM 59841 and T32 069330

References

- 1.Moore FA, Sausaia A, Moore EE. Post injury multiple organ failure: a bimodal phenomenon. Journal of Trauma. 1996;40:501–12. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199604000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharpe SM, Doucet DR, Qin X, Deitch EA. Role of intestinal mucus and pancreatic proteases in the pathogenesis of trauma-hemorrhagic shock-induced gut barrier failure and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Journal of Organ Dysfunction. 2008;4:168–76. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deitch EA. Multiple organ failure: Pathophysiology and potential future therapies. Annals of Surgery. 1992;216:117–134. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199208000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kistler EB, Hugli TE, Schmid-Schoenbein GW. The pancreas as a source of cardiovascular cell activating factors. Microcirculation. 2000;7:183–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atuma C, Strugala V, Allen A, Holm L. The adherent gastrointestinal mucus gel layer: thickness and physical state in vivo. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2001;280:G922–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.5.G922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin X, Caputo FJ, Xu DZ, Deitch EA. Hydrophobicity of the mucosal surface and its relationship to gut barrier function. Shock. 2008;29:372–6. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3181453f4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swidsinski A, Loening-Baucke V, Theissig F, Engelhardt H, Bengmark S, Koch S, Lochs H, Dorffel Comparative study of the intestinal mucus barrier in normal and inflamed colon. Gut. 2007;56:343–50. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.098160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rupani B, Caputo FJ, Watkins AC, Vega D, Magnotti LJ, Lu Q, Xu DZ, Deitch EA. Relationship between disruption of the unstirred mucus layer and intestinal restitution in loss of gut barrier function after trauma hemorrhagic shock. Surgery. 2007;141:481–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caputo FJ, Rupani B, Watkins AC, Barlos D, Vega D, Maheswari S, Deitch EA. Pancreatic duct ligation abrogates the trauma hemorrhage-induced gut barrier failure and the subsequent production of biologically active intestinal lymph. Shock. 2007;28:441–6. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31804858f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitsuoka H, Kistler EB, Schmid-Schoenbein GW. Generation of in vivo activating factors in the ischemic intestine by pancreatic enzymes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States America. 2000;97:1772–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen DB, Magnotti LJ, Lu Q, Xu DZ, Berezina TL, Zaets SB, Alvarez C, Machiedo G, Deitch EA. Pancreatic ductal ligation reduced lung injury following trauma and hemorrhagic shock. Annals of Surgery. 2004;240:885–91. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143809.44221.9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deitch EA, Shi HP, Lu Q, Feketeova E, Xu DZ. Serine proteases are involved in the pathogenesis of trauma-hemorrhagic shock induced gut and lung injury. Shock. 2003;19:452–6. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000048899.46342.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosario HS, Waldo SW, Becker SA, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Pancreatic trypsin increases matrix metalloproteinase-9 accumulation and activation during acute intestinal ischemia-reperfusion in the rat. American Journal of Pathology. 2004;164:1707–16. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63729-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deitch EA, Xu DZ, Lu Q. Gut lymph hypothesis of early shock and trauma-induced multiple organ dysfunction syndrome: A new look at gut origin sepsis. Journal of Organ Dysfunction. 2006;2:70–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnotti LS, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Deitch EA. Gut-derived mesenteric lymph: a link between burn and lung injury. Archives of Surgery. 1999;134:1333–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheth SU, Lu Q, Twelker K, Sharpe SM, Qin X, Reino DC, Lee MA, Xu DZ, Deitch EA. Intestinal mucus layer preservation in female rats attenuates gut injury after trauma-hemorrhagic shock. The Journal of Trauma. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181caa6bd. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deitch EA, Adams CA, Lu Q, Xu DZ. A time course study of the protective effects of mesenteric lymph duct ligation on hemorrhagic shock induced pulmonary injury and the toxic effects of lymph from shocked rats on endothelial cell monolayer permeability. Surgery. 2001;129:39–47. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.109119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu L, Zaborina O, Zaborin A, Zaborin A, Chang EB, Musch M, Holbrook C, Shapiro J, Turner JR, Wu G, Lee KYC, Alverdy JC. High-molecular weight polyethylene glycol prevents lethal sepsis due to intestinal Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:488–98. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deitch EA, Adams CA, Lu Q, Xu DZ. Mesenteric lymph from rats subjected to trauma-hemorrhagic shock are injurious to rat pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells as well as human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Shock. 2001;16:290–3. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senthil M, Brown M, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Feketeova E, Deitch EA. Gut lymph hypothesis of systemic inflammatory response syndrome/multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome: validating studies in a porcine model. Journal of Trauma. 2006;60:958–65. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000215500.00018.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deitch EA, Feketeova E, Adams JM, Forsythe RM, Xu DZ, Itagaki K, Redl H. Lymph from a primate baboon trauma hemorrhagic shock model activates human neutrophils. Shock. 2006;25:460. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000209551.88215.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grisham MB, Von Ritter C, Smith BF, Lamont JT, Granger DN. Interaction between oxygen radicals and gastric mucin. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253:G93–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1987.253.1.G93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forstner JF. Intestinal mucins in health and disease. Digestion. 1978;17:234–63. doi: 10.1159/000198115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freire Cerqueira N, Hussni CA, Bonetti Yoshida W, Lopes Sequeira J, Padovani CR. Effects of pentoxifylline and n-acetylcysteine on injuries caused by ischemia and reperfusion of splanchnic organs in rats. Int Angiol. 2008;27:512–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Da Silveira M, Bonetti Yoshida W. Trimetazidine and N-acetylcysteine in attenuating hind-limb ischemia and reperfusion injuries: experimental study in rats. Int Angiol. 2009;28:412–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turut H, Ciralik H, Kilinc M, Ozbag D, Imrek SS. Effects of early administration of dexamethasone, N-acetylcysteine and aprotinin on inflammatory and oxidant-antioxidant status after lung contusion in rats. Injury, Int J Care injured. 2009;40:521–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]