History

A 13 year-old male with a chief complaint of recurrent epistaxis is shown to have a pearly white mass in right nasal cavity on physical exam.

Radiographic Features

Computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance imaging studies are currently the mainstay for diagnosis and aid in delineating the extent of tumor and degree of surrounding tissue destruction. An anterior bowing of the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, the “antral bowing sign,” can be identified in most patients. Other commonly seen radiographic changes include widening of the inferolateral aspect of the superior orbital fissure, distortion of the pterygoid plates, erosion of the hard palate, disruption of the medial wall of maxillary sinus, and displacement of the nasal septum.

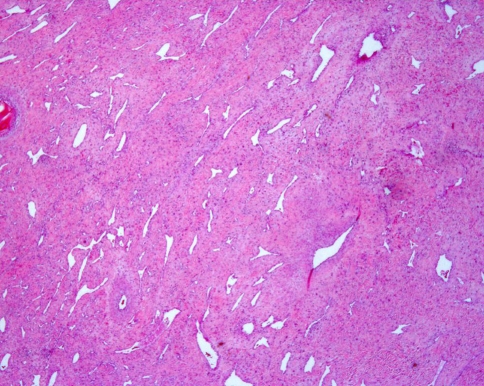

In the current case, visualization of an axial T2 weighted magnetic resonance image demonstrated an intermediate to high signal, well-circumscribed mass noted in the right nasal cavity and chonca at the level of the condyles which extended from the posterior nasal cavity to the pharyngeal region. This mass crossed as well as displaced the midline and extended into pterygopalatine fossa and the medial ptyergoid muscle (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Axial T2 weighted magnetic resonance image demonstrates a well-circumscribed mass in the right nasal cavity crossing the midline and displacing the midline medially. Arrows point indicating voids signifying hypervascularity of the lesion

Diagnosis

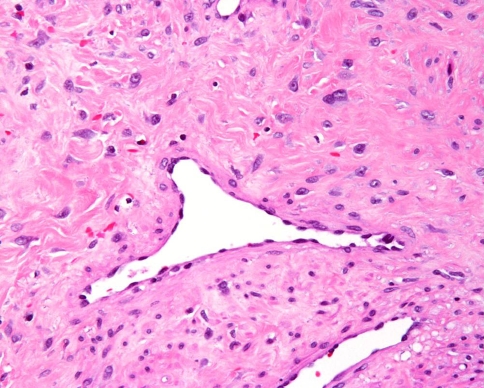

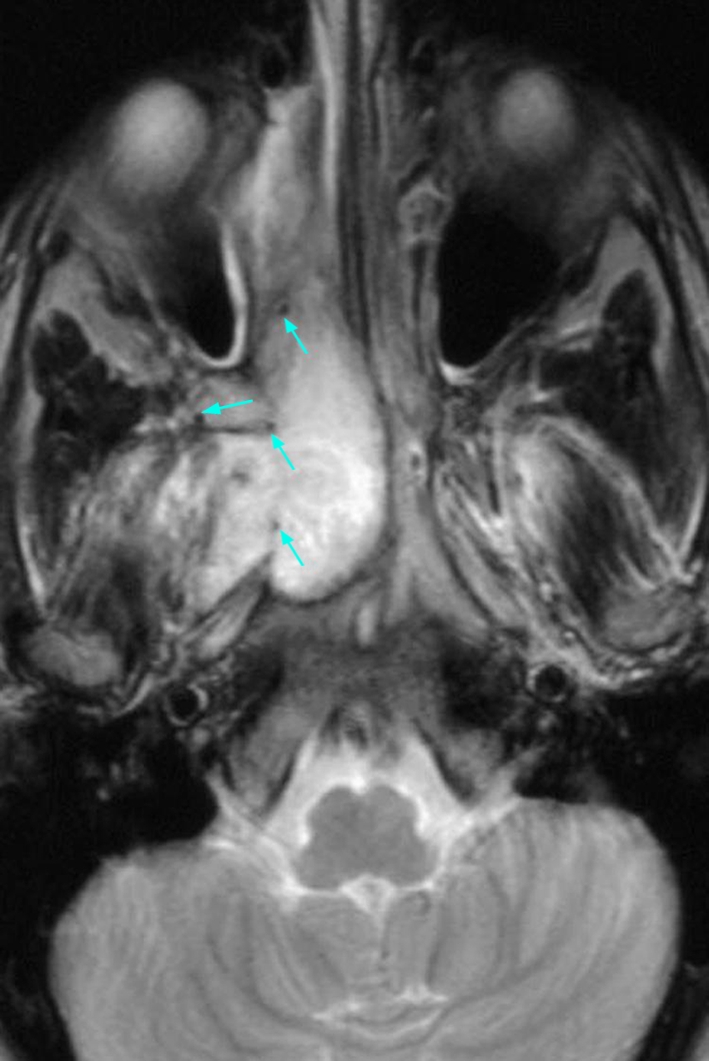

Evaluation of the hematoxylin and eosin stained surgical specimen (Fig. 2) demonstrated variably dense fibrovascular stroma containing numerous angular, irregularly shaped gaping vessels. The vessels are lined by thin endothelial cells and are supported by a collagenous stroma containing numerous spindled to stellate shaped fibroblasts with plump nuclei and mild nuclear pleomorphism (Fig. 3). The degree of cellularity varied and mitotic activity was not identified.

Fig. 2.

Low power view showing fibrocollagenous stroma and vessels of varying arrangement and caliber

Fig. 3.

Thin walled, angulated vessel lined by plump endothelium contained within a stroma of abundant, plump, stellate shaped fibroblasts

Discussion

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma is an uncommon, benign, fibrovascular tumor which exhibits a distinct predilection for adolescent males and accounts for less than 1% of all head and neck neoplasms [1, 2]. Given the strict epidemiology, hormonal influences seem likely as investigators have revealed the presence of androgen, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone receptors [3, 4] and lack estrogen and progesterone receptors [4, 5]. As such, a diagnosis in a female patient remains controversial and should be viewed with skepticism. Of the 150 cases reviewed at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology no female patients were identified [6]. Despite histologically benign features, nasopharyngeal angiofibromas frequently demonstrate locally destructive and aggressive clinical behavior evidenced by the propensity to invade surrounding anatomic regions, invoking significant morbidity and occasional mortality [7, 8]. Approximately 20% of cases demonstrate considerable obstacles in clinical management due to skull base penetration and involvement of vital intracranial structures [9]. Although the histopathogenesis is still somewhat unclear, many investigators have suggested, based upon electron microscopy and immunohistochemical studies, that this tumor may actually represent a vascular malformation rather than a true neoplasm [10, 11].

Clinically, nasopharyngeal angiofibroma presents as a nasal mass or obstruction with repeated episodes of epistaxis. Less common presenting symptoms include facial swelling, diplopia, proptosis, headache, anosmia, and pain [2, 12]. The lesion is currently presumed to arise in the pterygopalatine fossa region and may proliferate into the surrounding anatomic area [13]. The ultimate danger of unchecked growth of this tumor is the potential risk of intracranial extension. Thje gross specimen consists of a lobulated, tan to purple-red, rubbery-firm, non-encapsulated masses which typically average 3–5 cm in maximum tumor dimension. The tumor base may be sessile or pedunculated, but often exhibits numerous “secondary” extensions, complicating resection.

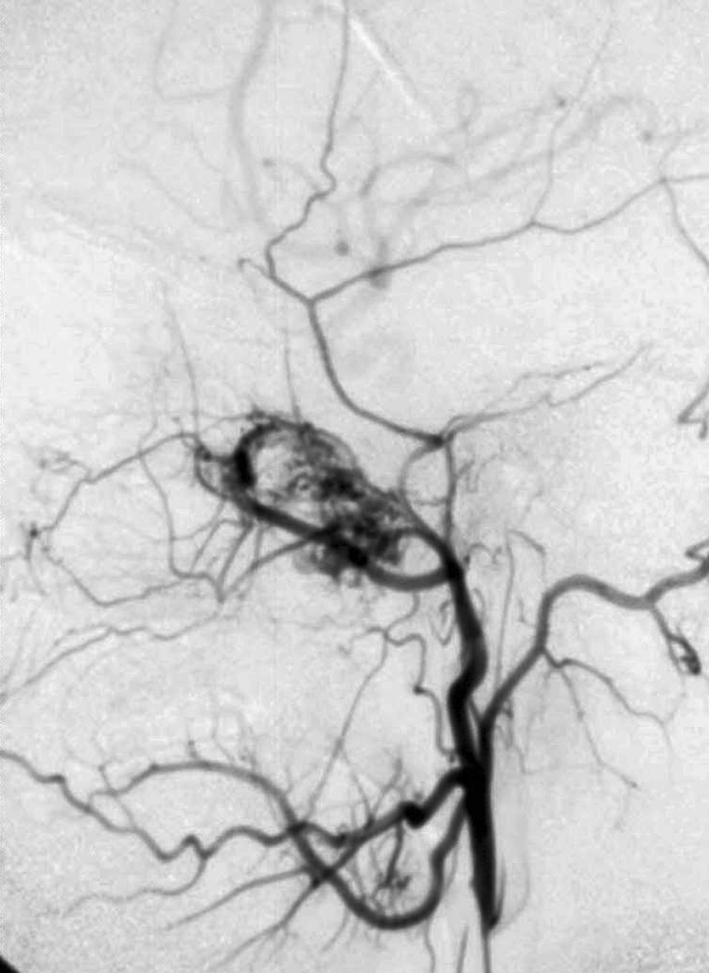

Several salient, highly characteristic radiographic features are typically observed via computed tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies which delineate the extension of tumor and reveal the degree of surrounding tissue destruction. Selective arteriograms can also be utilized to further demonstrate the conspicuously diagnostic vascular growth patterns (Fig. 4). In a medial direction, the nasal cavity may be occupied via extension through the sphenopalatine foramen. Anteriorly, it may push forward the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, creating the classic “antral bowing sign.” Posteriorly, it may disrupt the root of the pterygoid plates. Superiorly, the tumor can migrate into the orbit via the inferior orbital fissure and, subsequently, invade and expand the inferiorlateral aspect of the superior orbital fissure to gain access into the middle cranial fossa. Lateral expansion would allow tumor to infiltrate the pterygomaxillary fissure and access the infratemporal fossa region, often creating a clinically evident bulging of the cheek.

Fig. 4.

Arteriogram showing a hypervascular tumor fed by the external carotid artery

The preoperative diagnosis of nasopharyngeal angiofibroma can be a challenging task. The diagnosis is predicated upon appropriate clinical history and the highly characteristic radiographic appearance. In fact, biopsy prior to definitive treatment is generally condemned as both unnecessary and hazardous [14]. The differential diagnosis of a nasopharyngeal mass would also include lobular capillary hemangioma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, hemangiopericytoma, solitary fibrous tumor, angiosarcoma, choanal polyp, angiomatous polyp, chordoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. However, the distinctive radiographic features coupled with the appropriate age and sex of patient should strongly favor the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal angiofibroma.

The primary treatment consists of surgical excision. Depending upon the extent of the underlying tumor, some surgical modalities include a lateral rhinotomy, midfacial degloving procedure, infratemporal fossa approach, or a combined craniofacial resection [8, 15, 16]. Preoperative embolization of tumor has been recommended to reduce the risk of intraoperative hemorrhage. The recurrence rate for the juvenile angiofibroma is approximately 20% [14] with this high recurrence rate likely due to incomplete surgical resection. Such recurrences are treated with further surgery or radiation therapy. Patients with intracranial extension often require a combined intracranial and extracranial procedure. Radiotherapy therapy is of value in unresectable cases, however, postirradiation sarcomatous change is a well recognized, although rare, complication [17–19]. Chemotherapeutic agents have also shown some value for unresectable or recurrent tumors [20]. Despite an aggressive nature, the overall prognosis is excellent with a less than 1% mortality rate related to uncontrollable hemorrhage and intracranial extension [21].

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and appreciate the radiographic interpretation expertise of Dr. Ann Monasky.

Disclaimer The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as official or representing the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Batsakis JG. Tumors of the head and neck: clinical and pathological considerations. 2. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1979. pp. 296–300. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neel HB, Whicker JH, Devine KD, Weiland JH. Juvenile angiofibroma: review of 120 cases. Am J Surg. 1973;126:547–556. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(73)80048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang HC, Mills SE, Patterson K, et al. Expression of androgen receptors in nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: an immunohistochemical study of 24 cases. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:122–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee DA, Rao BR, Meyer JS, et al. Hormonal receptor determination in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. Cancer. 1980;46:547–551. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800801)46:3<547::AID-CNCR2820460321>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johns ME, MacLeod RM, Cantrell RW. Estrogen receptors in nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:628–634. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198004000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyams VJ. Tumors of the upper respiratory tract: vascular tumors. In: Hyams VJ, Batsakis JG, Micheals L, editors. Atlas of tumor pathology, 2nd series. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1986. pp. 130–145. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagan JJ, Snyderman CH, Carrau RL, Janecka IP. Nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: selecting a surgical approach. Head Neck. 1997;19:391–399. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199708)19:5<391::AID-HED5>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unganont K, Byers RM, Weber RS, Callender DL, Wolf PE, Goepfer H. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: an update of therapeutic management. Head Neck. 1996;18:60–66. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199601/02)18:1<60::AID-HED8>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamel RH. Transnasal endoscopic surgery in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110:962–968. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100135467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beham A, Beham-Schmid C, Regauer S, Aubock L, Stammberger H. Nasopaharyngeal angiofibroma: true neoplasm or vascular neoplasm. Adv Anat Pathol. 2000;7:36–46. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200007010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beham A, Fletcher CDM, Kainz J, et al. Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: an immunohistochemical study of 32 cases. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;423:281–285. doi: 10.1007/BF01606891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witt TR, Shah JP, Sternberg SS. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas: a 30 year clinical review. Am J Surg. 1983;146:521–525. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(83)90245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouqout JE. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. St. Louis: WB Saunders Company; 2009. pp. 692–695. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wanamaker JR, Lavertu P, Levine HL. Juvenile angiofibroma. In: Kraus DH, Levine HL, editors. Nasal neoplasia. New York: Thieme; 1997. pp. 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bales C, Kotapka M, Loever LA, Al-Rawi M, Weinstein G, Hurst R, Weber RS. Craniofacial resection of advanced juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margalit N, Wasserzug O, De-Row A, Abergel A, Fliss DM, Gil Z. Surgical treatment of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma with intracranial extension. Clinical article. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;4(2):113–117. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.PEDS08321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen KTK, Bauer FW. Sarcomatous transformation of nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Cancer. 1982;49:369–371. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820115)49:2<369::AID-CNCR2820490226>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batsakis JG, Klopp CT, Newman W. Fibrosarcoma arising in a “juvenile” nasopharyngeal angiofribroma following extensive radiation therapy. Am Surg. 1955;21:786–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janaki MG, Nimala S, Rajeev AG. Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma treated with radiotherapy. J Cancer Res Ther. 2007;3(2):100–101. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.34688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goepfert H, Cangi A, Lee Y-Y. Chemotherapy for aggressive juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;111:285–289. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1985.00800070037002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGavran MH, Sessions DG, Dorfman RF, et al. Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Arch Otolaryngol. 1969;90:68–78. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1969.00770030070014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]