Abstract

Eosinophilc angiocentric fibrosis is a rare fibrosing vasculitis of unknown etiology that is progressive and potentially disfiguring. It has a predilection for the upper airways presenting most commonly as an obstructing mass lesion that is diagnosed histologically. Thus far, it has been nonfatal in the more than 40 reported cases; however, subglottic and ocular involvement has resulted in significant morbidity in several patients. Treatment has been challenging with persistent disease in most cases. The current case is a prototypical presentation with a limited nasal septal lesion providing the opportunity to discuss clinically relevant issues and increase awareness.

Introduction

Eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis (EAF) is a rare, benign fibrosing lesion first described by Holmes and Panje in 1983 as “intranasal granuloma faciale (GF)” [1]. In 1985, with a report of three similar intranasal cases, Roberts and McCann provided a detailed histological account of the disease and coined the descriptive name regarding it as a mucosal variant of GF [2]. EAF has a clear clinical and histological appearance by which it is diagnosed, but its pathogenesis is still undetermined. To date, there have been 42 reported cases (including this one) and reports in recent years have become more frequent, likely due to increasing awareness of the disorder.

We report a case of intranasal EAF and review the clinical course, radiological and histological features, as well as diagnosis, etiology and treatment of these lesions based on previously reported cases.

Case Report

A 63-year-old man was referred for a progressive 10-year history of nasal obstruction, left greater than right. He also reported decreased smell and taste but denied any symptoms of sinusitis. He had no history of nasal trauma, allergies, atopy or aspirin sensitivity. Physical exam demonstrated large submucosal thickening of the anterior septum, which felt cystic on palpation. There were no cutaneous lesions.

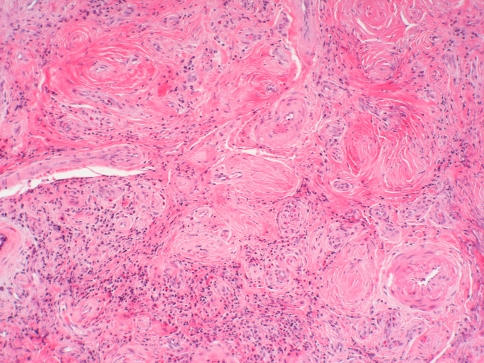

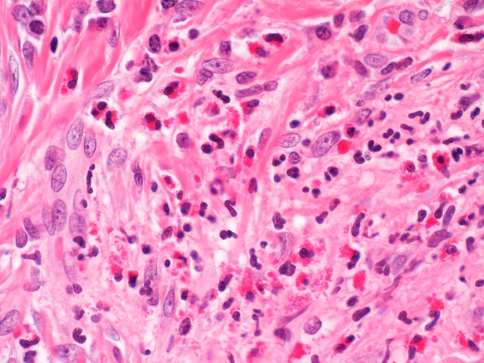

A CT scan of the sinuses showed a focal 2.8 × 1.7 cm soft tissue density mass arising from the anterior aspect of the nasal septum containing few scattered calcifications (Fig. 1). Based on these findings, it was felt that the patient had a septal tumor, which was resected via an open rhinoplasty approach. Examination under low power view (20× objective) showed dense concentric fibrosis and mixed inflammatory cells. The fibrosis was in an angiocentric pattern (Fig. 2). High power view (40× objective) showed a mixture of lymphocytes, eosinophils and proliferating fibroblasts (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Sinus CT shows 2.8 × 1.7 cm soft tissue density mass

Fig. 2.

Low power view (20× objective)

Fig. 3.

High power view (40× objective)

Discussion

The clinical course of EAF is that of a slowly progressing fibrotic disease [1–10]. Typical symptoms include nasal obstruction, epistaxis, pain and swelling [2–5]. Obstruction of the nasal passages by a mass, submucosal thickening or septal deviation is usually reported on physical exam. It is not uncommon to see some degree of nasal deformation. The slow progression and nonspecific symptoms account for its delayed presentation and diagnosis averaging approximately 5 years [4, 5, 8]. EAF predominantly affects the upper airways with roughly 75% of cases limited to the nasal septum, lateral nasal wall and sinuses. Most early lesions present with focal areas of septal involvement that progress to involve the entire septum and lateral nasal wall [6]. There have been two case reports of subglottic involvement [2, 3], five case reports involving the orbit [7, 8] and three cases with progressive pharyngeal and soft palate involvement [9]. Notably, aside from the subglottic cases, all others have had some degree of nasal/sinus involvement. Men and women are affected equally, and the average age at diagnosis is 48 with a range of 19–72. History of atopy/allergy has been present in approximately 25% of cases with a similar number affected by GF, a dermal disease with very similar histologic features, presenting most frequently after EAF has been diagnosed.

Imaging, both CT and MRI, is nonspecific and typically reveals a well-circumscribed submucosal soft tissue density mass with sinus opacification [4]; some masses have been reported to cause cartilaginous and bone destruction [5–8]. EAF is a progressive disease, but there is some evidence that the lesion stabilizes over time, and no EAF-related mortalities have been recorded. There have also been no reports of neoplastic degeneration.

EAF remains a histological diagnosis [2, 4] and can be described as a fibrosing eosinophilic vasculitis. The lesion progresses from an early inflammatory lesion to a late fibrotic lesion, and it is possible in a single biopsy to see both present—evidence of their evolving nature. The early lesion is a vasculitis with an inflammatory infiltrate containing eosinophils, plasma cells and lymphocytes. It involves only microvasculature, usually in a patchy distribution, and evolves into foci of fibrosis. Notably, there is an absence of fibrinoid necrosis or true granuloma formation, and the mucosa is typically spared [2]. The infiltrate has been shown to be polyclonal in nature and therefore inflammatory and not neoplastic [4, 5, 8]. The late lesion is characterized by dense fibrous thickening with perivascular “onion skin” fibrosis and patent microvasculature with decreased inflammatory infiltrate [2].

The differential diagnosis for EAF is broad and includes inflammatory, infectious and various neoplastic conditions. The diagnosis is aided by the fact that it lacks systemic disease manifestation, characteristic laboratory abnormalities, fibrinoid necrosis, granuloma formation and glandular involvement [3, 4, 8]. Ultimately, tissue is necessary to distinguish this disease from others including neoplastic conditions as illustrated by the current case.

There is no consensus on the relationship of EAF to GF. GF is also of unknown etiology that usually presents as well-circumscribed raised red brown plaques on the face [2]. In a review of the current cases, approximately 25% of patients developed both diseases. The fact that these two rare diseases have such a strong association makes it likely that they are related in some way [2, 6, 7].

The etiology of EAF remains unknown. Previously trauma was thought to be an inducing agent but data to this point do not support this finding with few patients having a remote history of nasal trauma or surgery prior to presentation [2, 4, 6]. There is, however, some evidence that trauma may promote disease progression [6]. For instance, a prior report of a 33-year-old woman with asymptomatic subglottic stenosis began having symptoms only after intubation, which was further exacerbated by biopsy [2]. Additional evidence comes from the apparent acceleration of disease progression in several cases following resection [5, 7]. Another potential etiology could be atopy/allergy with approximately 25% of patients having a positive history [2, 3, 5, 9]. This is supported by the rich eosinophilic infiltrate present. However, the lack of response to immunosuppressants makes this less likely [5].

Treatment of EAF thus far has been a challenge with approximately 70% of patients experiencing persistent or recurrent disease following treatment. Medical therapy in most instances has not been effective [2–6], although there have been a few reports of symptomatic improvement [1, 7]. Agents used thus far include corticosteroids (intranasal, intralesional and systemic), dapsone, antihistamines, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine and tamoxiphen. Surgical therapy has resulted in disease-free follow-up in approximately 30% of patients, leaving the majority of patients with recurrences requiring multiple resections. Notably, reports of disease eradication have only come from first time resections. Longer follow-up periods are necessary to confirm surgical outcomes; however, many authors agree that it is the treatment of choice [2, 3, 6–8, 10]. Our patient has remained disease free at 1-year follow-up; he has no evidence of disease recurrence and is completely asymptomatic. His post-operative course is notable for a stable septal perforation but there is no loss of nasal tip support.

In conclusion, EAF is a benign progressive disease with an elusive etiology. It has a distinctive histological appearance, clinical presentation and anatomical predilection that lead to the diagnosis. There is a strong association with atopy/allergy and GF in the previously reported cases. Treatment remains a challenge, but as more cases are reported it is likely that a clearer understanding of etiology and management will result in better outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Statements Financial Conflicts of Interests (BAW): ArthroCare ENT (Educational Grant), GlaxoSmithKline (Member of Speaker’s Bureau), Medtronic (Consultant).

Contributor Information

Jumin Sunde, Phone: +1-251-2596220, FAX: +1-205-9343993, Email: jsunde@uab.edu.

Bradford A. Woodworth, Email: bwoodwo@hotmail.com

References

- 1.Holmes DK, Panje WR. Intranasal granuloma faciale. Am J Otolaryngol. 1983;4(3):184–186. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(83)80041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts PF, McCann BG. Eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis of the upper respiratory tract: a mucosal variant of granuloma faciale? A report of three cases. Histopathology. 1985;9(11):1217–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1985.tb02801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fageeh NA, Mai KT, Odell PF. Eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis of the subglottic region of the larynx and upper trachea. J Otolaryngol. 1996;25(4):276–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson LD, Heffner DK. Sinonasal tract eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis. A report of three cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115(2):243–248. doi: 10.1309/7D97-83KY-6NW2-5608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabaee A, Zadeh MH, Proytcheva M, LaBruna A. Eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117(5):410–413. doi: 10.1258/002221503321626500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narayan J, Douglas-Jones AG. Eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis and granuloma faciale: analysis of cellular infiltrate and review of literature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114(1 Pt 1):35–42. doi: 10.1177/000348940511400107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paun S, Lund VJ, Gallimore A. Nasal fibrosis: long-term follow up of four cases of eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119(2):119–124. doi: 10.1258/0022215053419989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leibovitch I, James CL, Wormald PJ, Selva D. Orbital eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis case report and review of the literature. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(1):148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holsinger JM, Magro C, Allen C, Powell D, Agrawal A. Eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37(5):E155–E158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosarac O, Luna MA, Ro JY, Ayala AG. Eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis of the sinonasal tract. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2008;12(4):267–270. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]