Abstract

This article assesses the role of malaria and certain social determinants on primary education, especially on educational achievement in Donéguébougou, a small village in a malaria-endemic area near Bamako, Mali. Field data was collected by the authors between November 2007 and June 2008 on 227 schoolchildren living in Donéguébougou. Various malaria indicators and econometric models were used to explain the variation in cognitive abilities, teachers' evaluation scores, school progression and absences. Malaria is the primary cause of school absences. Fixed effects estimates showed that asymptomatic malaria and the presence of falciparum malaria parasites had a direct correlation with educational achievement and cognitive performance. The evidence suggests that the correlation is causal.

Keywords: Malaria, Human capital, Education, Mali, children

INTRODUCTION

In Mali, malaria is endemic in over 90% of the total population. Children under five account for 35% of all consultations for malaria. Malaria ranks high among the causes of child mortality, it is the most common reason for pediatric consultations accounting for approximately 40% and it is one of the most common causes of febrile convulsions in children. Children who survive to school age continue to be vulnerable to malaria (Clarke, Brooker, Njagi, Njau, Estambale, Muchiri et al., 2004).

The quality of education and associated factors were studied for four reasons.

Macroeconomic assessments of the effects of malaria on long-term incomes quantified the impact of malaria on growth (Gallup & Sachs, 2001) but failed to identify the pathways concerned. This paper explores education as a possible pathway. Higher levels of education increase the growth of national income (Jamison, Jamison & Hanushek, 2007). Education is, therefore, an important issue for understanding the development and growth of countries affected by malaria.

Macroeconomic studies have found that malaria could have a significant macroeconomic impact on aggregate human capital accumulation (Thuilliez, 2009). Consequently, research on this relationship needs a better microeconomic foundation.

Accumulated evidence indicates that early test scores are correlated with education, earnings and future labor participation (Leibowitz, 1974).

Despite the significant impact of malaria on school-age children, there is a lack of evidence in the literature about the link between malaria and educational achievement. Confirmatory studies are needed.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND EXISTING LITERATURE

(a) Malaria and individual cognitive achievement

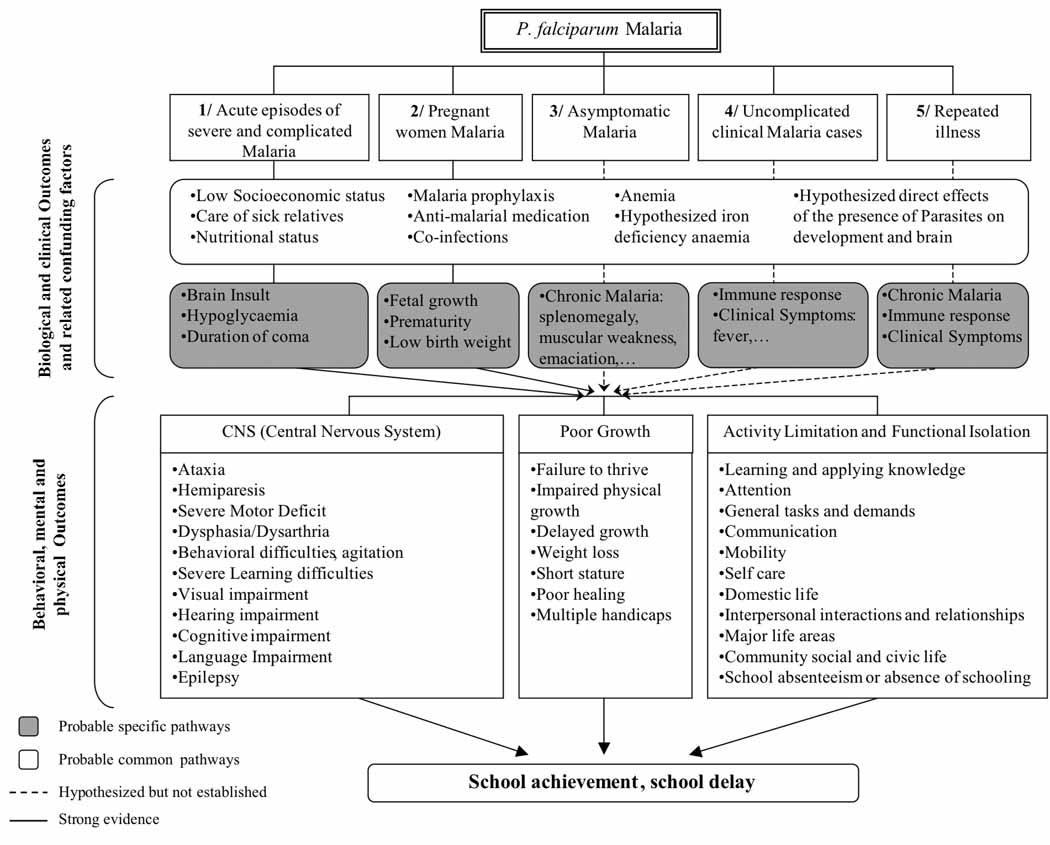

The question of the link between malaria, educational achievement and cognitive ability is not new but is far from being resolved. The mechanisms through which malaria affects education and learning remain unknown. Figure 1 gives a schematic diagram that models the pathways through which malaria may affect children’s educational achievement. Possible dependent mechanisms have been divided into biological, clinical and behavioral outcomes and probable common and specific pathways for each form of malaria. Cognition is defined as the mental process involved in knowing, learning and understanding (Shuell, 1986). This study focuses on educational achievement.

Figure 1.

Probable effects and pathways of falciparum Malaria on School Performance.

It is generally accepted that cerebral malaria, malaria during pregnancy and iron deficiency anemia can affect the architecture of a developing brain. Much less is known about how other forms of malaria (asymptomatic malaria, uncomplicated clinical malaria and repeated attacks) affect the cognitive ability and scholastic performance of school children. Tables 1 and 2 give an overview of the methods, measurements and results of recent studies in this field of research. Studies about cognitive impairment after cerebral malaria or long-term handicap and cognitive impairment as a consequence of malaria during pregnancy are not taken into account as they are not directly linked to this study and have already been the subject of numerous literature reviews.

Table 1.

Studies examining cognitive function depending on falciparum and vivax malaria or evaluating the effect of malaria prevention on educational achievement since 2003: studies objectives and design.

| Study | Objectives | Study Design | Study Place | Duration | Population and Sample Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fernando et al. (2003a) | To assess the short term impact of an acute attack of malaria on cognitive performance of schoolchildren. |

Matched Case / Control study. Passive case detection using microscopy. |

Sri Lanka (Moneragala) |

Prospective study from January 1998 to November 1999. 14 days follow-up in November 1999 |

Age: 6–11 years (Grade 1 to 5). 648 schoolchildren: 199 children with malaria (MC), 144 children with non-malarial fever (NMFC), 305 healthy children (HC). |

| 2 | Fernando et al. (2003b) | To measure the impact of repeated attacks of malaria infection on the cognitive performances of children at school entry. |

Cross sectional Study. Past history of malarial attacks were collected from the parent or legal guardian by interview. |

Sri Lanka (Moneragala and Anuradhapura) |

One month follow-up in January 1997 (school entry). |

Age: 5–6 years (Grade 1). 325 schoolchildren |

| 3 | Fernando et al. (2003c) | To measure the impact of repeated attacks of malaria infection on the school performances of schoolchildren. |

Historical cohort study. Passive case detection using microscopy. |

Sri Lanka (Kataragama) |

Prospective study from January 1992 to November 1997. |

Age: 6–14 years (Grade 1 to 7). 571 schoolchildren |

| 4 | Fernando et al. (2006) | To investigate the impact of malaria and its prevention on educational attainment. |

Randomized, double- blind, Placebo / Control, Clinical Trial. |

Sri Lanka (Kataragama) |

Clinical trial from March to November 1999. |

Age: 6–11 years (Grade 1 to 5). 587 schoolchildren |

| 5 | Jukes et al. (2006) | To assess long-term impact of early childhood malaria prophylaxis on educational outcomes. |

Follow-up of a randomized, double- blind, Placebo / Control, Clinical Trial. |

Gambia (Farafenni) |

Intervention follow-up from April 1984 to March 1988. Data collection and cognitive assessment from May to November 2001. |

Age: 3–59 months at the beginning of the survey. 579 traced children. |

| 6 | Clarke et al. (2008) | To assess the effect of Intermitten preventive treatment (IPT) of malaria on health and education in schoolchildren. |

Cluster-randomised, double-blind, placebo- controlled clinical trial. |

Bondo District (Western Kenya) |

Clinical trial from March 2005 to January 2006. |

Age: 11–16 years (Grade 5 to 6). 818 schoolchildren included in the analysis of educational outcomes (intention to treat population). |

Table 2.

Studies examining cognitive function depending on falciparum and vivax malaria or evaluating the effect of malaria prevention on educational achievement since 2003: educational achievement measured and results.

| Study | School Outputs | Main Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fernando et al. (2003a) | Two cross-sectional educational assessments in November 1999. Grade specific examination papers (mathematics and language), absences. |

At the time of presentation and 2 weeks later, children diagnosed with malaria had significantly lower scores in mathematics and language (P<0.001) than NMFC and HC. The impairment seems to be cumulative with repeated attacks. A child having an accute attack of uncomplicated malaria was absent from school 5.4 days in average against 3.4 days for a child with non- malarial fever. Children absent for long duration due to a malaria episode have significantly lower scores. |

| 2 | Fernando et al. (2003b) | One cross-sectional educational assessment in January 1997. Cognitive performance (writting skill, reading skill, ability to count, ability to identify numbers,…) |

All indices of cognitive performance were poorer in children who had experienced more than 5 attacks of malaria during their lifetime compared to children who had had less than 4 attacks. |

| 3 | Fernando et al. (2003c) | One cross-sectional assessment in November 1997. Grade specific special examination designed for the study (25 questions, mathematics and language), 3 routine end of school examinations for 1997. |

Significant negative correlation between the total number of malarial attacks experienced by the child during the six years follow-up and tests and school scores. Experiencing more than six malarial infections decreased language and mathematic scores by 15% relative to those who had experienced fewer than 3 malarial infections. There is no significant association between anthropometric indices and school performances. |

| 4 | Fernando et al. (2006) | Two assessments pre and post-intervention. End- of-term examinations (mathemathics and language), absences. |

School absences due to malaria were reduced by 62.5%. Post-intervention, children who received chloroquine scored 26% higher in language and mathematics than children who received placebo. Educational attainment was significantly associated with taking chloroquine prophylaxis and absenteeism due to malaria. |

| 5 | Jukes et al. (2006) | One cross-sectional assessment in November 2001. Cognitive tests (visual, Raven's matrices, Digit span, Fluency, Proverbs, Vocabulary) Years at school, School enrolment. |

There were no significant differences between treated and control group in mental development scores but scores appeared significantly higher for children who received malaria prevention for the longest period. Children who received malaria prevention during the trial achieved half a grade higher in school. |

| 6 | Clarke et al. (2008) | One cross-sectional assessment in March 2006. Tests of everyday attention for children (TEA-Ch) behaviour in class (teacher ratings of inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive behaviours), educational attainments (end of school term exam). |

Significant improvements in TEA-Ch (counting sounds and code transmission) were seen in the IPT group compared with control group. No effect was shown for end of school term exam and inattentive behaviour. |

The main mechanisms suggested in the literature are through iron deficiency anemia after repeated attacks or asymptomatic malaria and through school absences after clinical malaria. However, the cognitive effects of anemia due to causes other than iron deficiency are not well understood and it is still not clear whether anemia in African children is caused predominantly by malaria or iron deficiency (Muller, Traoré, Jahn & Becher, 2003). There are, therefore, likely to be other mechanisms. This paper considers the direct effects of the presence of falciparum malaria parasites on educational achievement, independently of other parameters. Until now, studies have considered the indirect effects of exposure in utero on birth outcomes (Holding & Kitsao-Wekulo, 2004) and the limited number of investigations among school-age children have focused on the effect of parasite clearance (Clarke, Jukes, Njagi, Khasakhala, Cundill, Otido et al., 2008). The mechanism could include a “toxicity effect, leading to biochemical changes in the central nervous system (CNS); excitation of the immune system, leading to changes in behaviours related to appetite and reaction time; and physiological effects such as discomfort and disturbed sleep, leading to reductions in activity levels or causing behavioural change” (Holding & Snow, 2001). The relative contribution of clinical and asymptomatic malaria on cognitive achievement is discussed and the time-course of the effects is assessed by introducing lagged variables into the model. As there are many potential pathways to impaired educational development and because combinations of the different sources of variability in outcomes are plausible, a check was made for confounding factors and the relative contribution of different pathways was analyzed (mainly splenomegaly as an indicator of chronic infection and malarial anemia).

(b) Educational achievement in children

Learning has been conceptualized as a production process (Ben-Porath,1967). The economic conceptualization of cognitive development and educational achievement through a production function is rather simplistic. One limitation is that it does not account for psychological concepts about the dynamic, interacting nature of the developmental trajectories of specific skills or knowledge. Another limitation is that it assumes a unitary household model. Given the complexity of the impact of child health on educational achievement, a simpler approach can be adopted by defining:

| (1) |

where

Eijt is the educational achievement for child i residing in household j at time t;

S is years of schooling until time t;

Q is a vector of school and teacher characteristics considered to be exogenous and fixed;

C is a vector of child characteristics at time t (including innate ability);

H is a vector of household characteristics at time t;

I is a vector of educational inputs under the control of parents applied at any time up to time t such as time with a pedagogical value spent by brothers or sisters with the child;

M is the health history including malaria history of the child up to time t.

The production function emphasizes the role of malaria and health in determining educational skills. All the variables included have a direct effect on educational outcomes. Indirect effects are also possible but, as already stated, this study focused on the direct effects of the presence of malarial parasites on educational achievement. The effect of invariant innate ability on human capital accumulation is ambiguous and controversial: more innate ability could lead to less schooling or make learning easier and promote schooling (Cunha, Heckman, Lochner & Masterov, 2006). This study regards innate ability merely as another skill.

Finding an empirical specification of formula (1) given the data limitations (particularly missing data on inputs) poses numerous challenges and requires restrictions on the original empirical linear structure. Currie & Stabile (2006) and Fletcher & Wolfe (2008) use cohort data sets and fixed effects models to understand the influence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder on education, grade repetition and test scores in the United States and Canada. These studies were used as the basis for the model used in this analysis, in the particular context of a developing country.

This study differs from previous studies in a number of ways. Firstly, it used a different study design (panel dataset) and specific econometric models for panel data to assess the education production function and compare the incidence of malaria with other factors. It considered the possibility of omitted variables bias by estimating within-child fixed effects models. Secondly, the strength of the data lies in the careful assessment of parasitaemia, clinical malaria, biological predictor variables, socio-economic variables and a range of educational achievement. Thirdly, the time period studied was one full school year.

DATA AND METHODS

(a) Study site

Donéguébougou has a high, stable malaria transmission intensity (annual Entomologic Inoculation Rate > 100 infective bites per person). It has a population of approximately 1390 people (a full census was undertaken, before the study, in 2007 by the MRTC/DEAP). The village primary school was set up in 1994 and was managed until 1997 by the community. It became a Malian public school in 1998. Descriptive statistics are provided in Online Appendix A. Pupils used similar facilities in the school. None of the children had previously attended preschools or nurseries. This study focuses on P. falciparum malaria, which is far more severe than the other types of malaria. P. ovale and P. malariae malaria cases were insignificant in comparison with P. falciparum malaria cases.

(b) Ethical Clearance

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the National School of Medicine and Pharmacy of Mali. Treatment of malaria and other illnesses detected during the study was provided to the study population at no cost to participants and pupils not participating in the study. Community and individual written informed consent were obtained before starting the study. Of the 229 schoolchildren, 227 (81 girls and 146 boys) were included in the study. One legal guardian refused his consent for one child (Grade 5) because the parents were living outside the village. One child (Grade 1) arrived after the start of the study.

(c) Survey Methods

Data was collected during the whole school year from November 2007 to June 2008. Once informed consent had been obtained, all participating pupils received monthly clinical and laboratory examinations (active monthly follow-ups). Cognitive tests were administered the same day (just after the clinical examinations) directly in the school. Active monitoring was supplemented by continuous passive case monitoring. Pupils were monitored passively by the village health centre in collaboration with the schoolteachers and the school director. Every day, teachers identified and recorded the names of any children who were ill or absent to maximize case detection. Any child falling sick on a schoolday, at a weekend or during holidays was immediately referred to the village health centre, where he received a complete clinical examination. For both active and passive monitoring, all pupils with clinical symptoms or testing positive on physical examination were treated according to the national care standard. Those with clinical signs of uncomplicated malaria had their thick and thin smears read immediately to ensure quick diagnosis and treatment. To assess home inputs and other socio-economic household characteristics, a questionnaire was drawn up and interviews were conducted with the head of each household.

(d) Health Status

This study was specifically interested in P. falciparum malaria but different sets of health data were collected in the field by the medical team under the supervision of three doctors.

Anthropometric indices and hemoglobin level. The weight of each child was measured using an electronic scale and their height was measured using a stadiometer. Blood was obtained by a finger prick under aseptic conditions and the hemoglobin level was determined using a field hemoglobin analyzer (Hemacue©, Labnet International, Buckley WA). The age of each child was calculated in years and months using the date of birth given on his birth certificate from school records and confirmed, if necessary, by the village census. The weight and height of the children and their hemoglobin level were measured monthly during the cross-sectional survey. In order to compare children of different ages by sex, the anthropometric measurements were converted into two indices, height-for-age and weight-for-age z-scores, using the 2000 CDC (Centre for Disease Control and prevention) growth charts. As there was no significant variation between mean z-score from one month to another and from the first and last month, annual mean height-for-age and mean weight-for-age z-scores were used in the analysis. The changes in z-scores over time for the same child may reflect measurement error rather than changes in nutritional status.

- Malaria indices. The measurement of malaria was essential for this study. As already mentioned, each participant underwent a full monthly clinical examination during which axillary temperature was measured using an electronic thermometer. Malaria finger pricks were performed monthly on all participants and whenever symptoms or signs of malaria were present during the study. Parasitaemia (parasites / µL) was determined using a Giemsa-stained thick blood film (asexual forms of each plasmodium sp were counted on 300 leukocytes, assuming an average leukocyte count of 7500/µL of blood). During the study, clinical malaria was diagnosed if a child had at least one clinical symptom compatible with malaria (body temperature > 37.5°C, cephalgia, vomiting, stomach ache or diarrhea) together with a malaria-positive smear for P. falciparum parasitaemia. From these parasitological and clinical examinations, various malaria indices were used:

- The absolute number of new clinical malaria episodes per pupil per month was used as a measure of malaria incidence. A minimum period of seven days between two consecutive positive malaria smears for the same species of parasite was required to count the second positive smear as a new symptomatic episode.

- Three malaria risk indices were calculated to avoid measurement bias in the health status. The use of a “pyrogenic threshold” has been proposed as the best definition of malaria in endemic areas (Trape, Peelman & Morault-Peelman, 1985). In this study, it was considered that subjects, feverish or not feverish, with a level of parasitaemia over 500 P. falciparum trophozoites/µL (Clarke et al., 2004) might be suspected either of having a malaria attack or of having had one recently. This variable is a dummy equal to one if the child has a parasitaemia > 500 P. falciparum trophozoites/µL and zero otherwise. Other thresholds (1000 and 1200) were also considered to test the sensitivity of the results.

- Annual and monthly geometric means of P. falciparum parasitaemia were also used in some regressions to assess the impact of parasitaemia on educational achievement.

- Asymptomatic malaria was defined as a malaria-positive smear for P. falciparum parasitaemia associated with no clinical symptoms.

- The prevalence of malarial anemia among school age children is generally defined as a malaria-positive smear for P. falciparum parasitaemia and a hemoglobin concentration of less than 11.0 g/dL. To account for other threshold effects (mild: 8.0 ≤ Hb≤ 10.9; moderate: 6.1≤ Hb≤ 7; severe: Hb ≤ 6.0 g/dL) malarial anemia was defined a priori as an ordinal variable in accordance with Ong'Echa, Keller, Were, Ouma, Otieno, Landis-Lewis, et al. (2006). No malarial anemia is defined as a malaria-positive smear for P. falciparum parasitaemia and absence of anemia (i.e., Hb > 11.0 g/dL)

- Splenomegaly was assessed via spleen measurement using the Hackett classification (Hackett, 1944). Splenomegaly is an enlargement of the spleen resulting from an abnormal immune response to repeated attacks of malaria. Many of the mechanisms leading to an enlarged spleen are exaggerated forms of normal spleen function and a wide variety of diseases (schistosomiasis, post-necrotic cirrhosis, thalassemia, leukemia, lymphoma, myelofibrosi) are associated with enlargement of the spleen.

- Past convulsions were a final indicator of the severe malaria history of the child. This variable was defined on the basis of a questionnaire administered to the head of household and questions put to the child’s mother.

- The probability of sleeping under a mosquito net the night before the interview was defined on the basis of the above questionnaire. This variable is the number of children who slept under a mosquito net the night before the interview divided by the number of children who actually slept in the house the night before the interview.

(e) Socio-economic data about households

Socio-economic data was collected in December 2007 using a questionnaire administered by researchers to the head of household in each pupil’s family. Another questionnaire was administered quarterly in December 2007, March 2008, and July 2008 to account for seasonal variations.

- Home inputs. It is very difficult to estimate incomes and economic levels in rural areas. Several types of resources were selected and four types of socio-economic indices were defined (Audibert, Mathonnat & Henry, 2003):

- “Convenience Property”: a relative index of household socio-economic status (SES) was derived based on dichotomous variables (durable goods such as TV set, radio set, motorcycle, housing infrastructure, etc) using principal components analysis (PCA). Long-run wealth is thought to explain the maximum variance and covariance in the asset variables (Filmer & Pritchett, 2001).

- “Store-of-value property”: an indicator of livestock possession.

- “Productive capital”: an indicator of agricultural equipment or land area pertaining to the household.

- “Monetary Income”: to evaluate monetary income from agricultural or non-agricultural activities, the average amount received per month and the source of income was estimated using quarterly interviews. This method is simplistic but it was not possible to use a more demanding procedure.

The borrowing constraint hypothesis states that credit access could play a role in children’s human capital investments (Jacoby & Skoufias, 1997). The interviews asked about formal or informal access to credit but nobody in the sample had access to formal credit.

Human Capital factors. Age, literacy and education of the head of household and the child’s parents were used as measured human capital factors. Questions about child labor were also included in the interviews.

(f) Educational achievement

Assessments. The study focused on a set of measurements intended to represent the child’s human capital accumulation. These included cognitive function (specific tests), educational achievement (routine school notes) and absences. Specific cognitive tests were drawn up with the team of Donéguébougou teachers. They were derived from questions already validated in other studies (Jukes, Pinder, Grigorenko, Smith, Walraven, Bariau et al., 2006) and adapted to the Malian context. This was a multi-step process: new questions or statements were drawn up based on the format of the original test questions. The content of the assessment was modified, but the basic format remained the same. The teachers assessed the suitability of the content for the age and grade-level programs and defined four categories: vocabulary (crystallized intelligence), writing, visual memory and selective attention and inductive reasoning (fluid intelligence). Cognitive tests were grade-specific but not time-specific. A Malian adaptation (in Bambara and French) of the Mill Hill vocabulary test was used as the measure of vocabulary. Writing abilities were tested by asking pupils to copy words or paragraphs. Selective attention and visual memory were tested with a visual search test, assessing the speed at which children identified target pictures among distracters. This test was done with several items, timed, requiring the children to mark targets with a pencil. Inductive reasoning was tested with a series of reasoning tests. For each test, the child was asked to find the missing number in a series. The tests became progressively harder, requiring greater cognitive capacity. All tests were administered by the teachers in one session lasting around 45 minutes in the school. Cronbach's alpha statistic was derived for the scale formed from the four variables defined above. Internal reliability was high (cronbach α = 0.72). Academic performance can be assessed using school progress reports and the teacher’s judgment (Nokes, Grantham-McGregor, Sawyer, Cooper, Robinson & Bundy, 1991). Routine evaluations were given by teachers according to the national education program (first grade children have no evaluations). Absences and their causes were also recorded each morning and afternoon by the teachers. School absences for medical reasons were confirmed by the health centre registry and attributed to a specific disease.

Output Variables. All cognitive variables were standardized by class, but not by cross-sectional follow-up to take into account the evolution of scores over time. A principal component analysis was then performed on the four cognitive function variables to calculate a cognitive function score (Bartlett 1937). 57.78% of the variance of the cognitive tests is explained by the first principal component. Test-retest reliability, assessed through the correlation matrix between cognitive function scores from the eight active monthly follow-ups, was acceptable (mean = 0.740; standard deviation = 0.116). The validity of the cognitive function score as a measure of educational achievement in the primary school was illustrated by the high significant correlation between the annual average standardized academic school marks and the annual cognitive mean function score (r = 0.815). The cognitive function score, therefore, seemed to be a good measure of educational achievement (Online Appendix Figure A1). Condensing the information contained in the original variables into one dimension with a minimum loss of information was justified as the aim was not to assess the impact of malaria only on particular cognitive skills but also on the common underlying process involved in knowing, learning, and understanding. Additional analysis for each of the four variables included in the cognitive score is given in Online Appendix Table B1. Mean standardized routine school marks were then used to test the robustness of the results. Finally, an educational achievement variable was defined in accordance with the Moock & Leslie (1986) procedure (results provided in Online Appendix Table B2).

(g) School absences and bivariate analysis

Malaria was the most common cause of absences (Online Appendix Table A3). However, in absolute terms, the figures are lower than other results found in the literature. This can be explained by the specific attention and early treatment received by schoolchildren. Because absences due to malaria were very low, it seemed unrealistic to suppose that malaria could have an impact on the cognitive function through absences in this study and so no multivariate analysis was performed.

Table 3 compares the cognitive function mean scores between sub-samples and shows the effect of the various malaria measurements on cognitive achievement. However, these results do not account for several confounding factors: individual specific effects, age, grade, socioeconomic status, variable lagging, etc. Nor can they be used to identify mediation effects and test the main hypothesis. The econometric models described in the next section are useful for checking these factors and completing the analysis.

Table 3.

Cognitive performance of children studied versus health status.

| Variables | Obs (%) | Cognitive function Mean score |

SD | Student’s t-test and Anova F-test P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Follow-up | |||||

| Clinical Malaria | |||||

| No | 1766 (98.43) | 0.008 | 1.417 | 0.033** | |

| Yes | 28 (1.56) | −0.562 | 0.942 | ||

| P. falciparum Parasitemia | |||||

| <500 | 1491 (83.11) | 0.072 | 1.394 | <0.001*** | |

| 500–1000 | 108 (6.02) | −0.035 | 1.426 | ||

| 1000–1200 | 19 (1.05) | −0.080 | 1.475 | ||

| >1200 | 176 (9.81) | −0.588 | 1.428 | ||

| Asymptomatic Malaria | |||||

| No | 1037 (57.80) | 0.064 | 1.356 | 0.023** | |

| Yes | 757 (42.19) | −0.088 | 1.484 | ||

| Splenomegaly | |||||

| No | 1702 (94.87) | 0.006 | 1.418 | 0.428 | |

| Yes | 92 (5.12) | −0.113 | 1.316 | ||

| Non malarial Anemia | |||||

| No | 828 (46.15) | 0.099 | 1.320 | 0.503 | |

| Mild | 177 (9.86) | 0.016 | 1.547 | ||

| Moderate | 4 (0.22) | −0.541 | 1.159 | ||

| Severe | no obs | no obs | no obs | ||

| Malarial Anemia | |||||

| No | 587 (32.72) | 0.010 | 1.497 | <0.001*** | |

| Mild | 191 (10.64) | −0.439 | 1.339 | ||

| Moderate | 7 (0.39) | −0.749 | 1.171 | ||

| Severe | no obs | no obs | no obs | ||

| Respiratory infections | |||||

| No | 1773 (98.82) | 0.001 | 1.415 | 0.665 | |

| Yes | 21 (1.17) | −0.132 | 1.189 | ||

| Helminth Infections | |||||

| No | 1788 (99.66) | −0.002 | 1.412 | 0.146 | |

| Yes | 6 (0.33) | 0.836 | 1.545 | ||

| Passive Follow-up | |||||

| Clinical Malaria between two active follow-ups | |||||

| No | 1666 (92.86) | 0.027 | 1.424 | 0.003*** | |

| Yes | 128 (7.13) | −0.355 | 1.200 | ||

| Respiratory infections between two active follow-ups | |||||

| No | 1759 (98.04) | −0.004 | 1.419 | 0.356 | |

| Yes | 35 (1.95) | 0.174 | 1.033 | ||

| Helminth Infections between two active follow-ups | |||||

| No | 1785 (99.49) | −0.003 | 1.413 | 0.192 | |

| Yes | 9 (0.50) | 0.612 | 1.292 | ||

| Active and Passive follow-up | |||||

| Repeated Malaria between two active follow-ups | |||||

| 0 | 1666 (92.86) | 0.027 | 1.424 | 0.012** | |

| 1 | 123 (6.85) | −0.348 | 1.222 | ||

| 2 | 5 (0.27) | −0.534 | 0.399 | ||

| Interviews | |||||

| Childhood Past Convulsion | |||||

| No | 204 (89.86) | 0.011 | 1.044 | 0.347 | |

| Yes | 23 (10.13) | −0.205 | 1.046 | ||

| Childhood Hospitalization | |||||

| No | 211 (92.95) | −0.016 | 1.069 | 0.836 | |

| Yes | 14 (6.16) | 0.043 | 0.681 | ||

| Childhood Malnutrition | |||||

| No | 212 (93.39) | −0.030 | 1.045 | 0.636 | |

| Yes | 10 (4.40) | 0.129 | 1.006 | ||

Notes. - denotes statistical significance at the 1% level.

denotes statistical significance at the 5% level.

denotes statistical significance at the 10% level.

EMPIRICAL SPECIFICATION

Firstly, a cumulative specification was used with orthogonal endowments and omitted inputs. Age and grade dummies were also included in the model. Observable lagged inputs were included, but the omitted inputs and endowments were assumed to be orthogonal to the included inputs (Todd & Wolpin, 2007). In particular, the time-course and magnitude of the effects of malaria on achievement were included by using one-period-lagged malaria indices.

This model was estimated using OLS regression techniques. Secondly, the fixed-effect specification (within child) was preferred to the random-effect model mainly because within variation was higher than between variation among variables. The family fixed effects models were not defined because main family-level factors were supposed to have been included in child fixed effects. The measurement error in the health variables was potentially a major problem but the research protocol already described and the use of well-measured malaria indicators reduced the risk of measurement error.

RESULTS AND IMPLICATION

Table 4 presents the baseline OLS estimates of the effect of malaria on cognitive functions and Table 5 presents the corresponding fixed effects estimates.

Asymptomatic malaria and Clinical Malaria. The regressions (1) of Tables 4 and 5 assess the relative contribution of asymptomatic malaria and clinical malaria. The results of regressions (1) of Tables 4 and 5 are similar for asymptomatic malaria and clinical malaria. Children who had experienced a clinical attack of malaria between two active follow-ups, or during active follow-up, scored between 0.368 and 0.542 less than children who had had no attack, allowing for other factors. These results also confirm previous results found in the literature on the impact of asymptomatic malaria on cognitive results (Clarke el al., 2008). Asymptomatic infection significantly affected (p-value=13% in regression (1) of Table 4) the cognitive performance of children but to a lesser degree (between −0.108 and −0.186) than clinical malaria. One explanation could be through the effect of falciparum malaria parasites per se on cognitive functions. This hypothesis is tested in regressions (2) to (5) of Tables 4 and 5.

Direct effects of the presence of falciparum malaria parasites on educational achievement. All parasitaemia variables had a significant negative effect on the cognition function PCA score, checking for other factors. Another interesting result is the cumulative effect of malaria parasitaemia. The higher the parasitaemia, the lower the cognitive score, as can be seen from regressions (3), (4), and (5). For instance, children with a P. falciparum malaria parasitaemia ≥1200 parasites / µL (checking for clinical malaria, splenomegaly and malaria anemia) had an average cognitive score of 0.354 less than children with a P. falciparum malaria parasitaemia <1200 parasites / µL (regression (5) of Table 5). Lagged variable coefficients in Table 5 show that the effects of the presence of the parasite persist for at least one month but decrease with time.

Other possible mediation effects. Other results regarding the control variables included in the OLS regressions of Table 4 are presented in Online Appendix Table A5. When associated with other variables, the effect of anemia and splenomegaly is unclear. The effect of the splenic index on cognitive score appears to be statistically significant and negative in Table 5 only. This may be due to the fact that the fixed effects model includes other invariant confounding factors determining splenomegaly. The effect of the convulsion history of the children in Table 4 is not statistically significant. This variable is based on a question put to the families and not on reliable observations. Other studies have already shown the long-term effects of cerebral malaria on cognitive achievement. Children with mild malarial anemia had lower scores than children with no malarial anemia but the effect of moderate malaria and the associated lagged anemia variable is ambiguous. It is possible that the coefficient of moderate malarial anemia is positive and significant because of the very small number of moderate malarial anemia cases (see Table 3). The role of splenomegaly and malarial anemia in depressing the cognitive performance of the child needs to be confirmed.

Effects of other variables. Results suggest that effective malaria prevention could also be a valuable addition to school health programs, as the probability of sleeping under a mosquito net the night before the interview is significant (at the 1% level) and positively correlated with cognitive performance in all regressions. However, it is also possible that this variable is a proxy for the way parents are taking care of their children, as discussed in the conclusion. The effect of malaria is also larger than the effect of other variables. The size of these effects can be seen in the effect of the height-for-age z-score, which is consistently significant. For example, a one-point increase in the height-for-age z-score is associated with a 0.55 increase in the cognitive function score. A one-point increase (or decrease) in the z-score was unusual in our study, whereas malaria is a common illness in this area.

Table 4.

The contemporaneous cumulative specification with orthogonal endowments and omitted inputs.

| Dependant variable is cognitive function PCA score |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS models | |||||

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| Asymptomatic Malaria and Malaria Parasitaemia | |||||

| Asymptomatic Malaria (active follow-up) | −0.108 (0.072) |

||||

| Lagged Asymptomatic Malaria (active follow-up) | −0.128* (0.075) |

||||

| Monthly Geom Mean P. falciparum Parasitaemia (/1000) | . | −0.024** (0.011) |

|||

| Lagged Monthly Geom Mean P. falciparum Parasitaemia (/1000) | . | −0.005 (0.008) |

|||

| P. falciparum Parasitaemia tresholds (active follow-up) 500 |

. | . | −0.176* (0.092) |

||

| Lagged 500 | . | . | −0.083 (0.084) |

||

| 1000 | . | . | . | −0.224** (0.112) |

|

| Lagged 1000 | . | . | . | −0.153 (0.094) |

|

| 1200 | . | . | . | . | −0.221* (0.114) |

| Lagged 1200 | . | . | . | . | −0.149 (0.098) |

| Clinical Malaria control Dummies | |||||

| Clinical Malaria (between two active follow- ups or during active follow-up) |

−0.386*** (0.100) |

−0.392*** (0.100) |

−0.385*** (0.100) |

−0.369*** (0.100) |

−0.368*** (0.101) |

| Lagged Clinical Malaria (between two active follow-ups or during active follow- |

−0.210** (0.093) |

−0.170* (0.095) |

−0.188** (0.094) |

−0.171* (0.094) |

−0.172* (0.094) |

| Chronic Malaria and Malaria anemia control Variables | |||||

| Splenomegaly | −0.000 (0.142) |

−0.008 (0.144) |

0.009 (0.140) |

0.001 (0.140) |

0.004 (0.141) |

| Lagged Splenomegaly | 0.135 (0.129) |

0.121 (0.131) |

0.111 (0.130) |

0.112 (0.129) |

0.113 (0.130) |

| Malarial anemia | |||||

| Mild | −0.114 (0.127) |

−0.175 (0.121) |

−0.147 (0.122) |

−0.148 (0.122) |

−0.158 (0.121) |

| Moderate | 0.021 (0.322) |

0.019 (0.317) |

0.126 (0.354) |

0.068 (0.350) |

0.063 (0.349) |

| Lagged Malarial anemia | |||||

| Mild | 0.020 (0.100) |

−0.060 (0.094) |

−0.026 (0.097) |

−0.016 (0.096) |

−0.025 (0.095) |

| Moderate | −0.697*** (0.256) |

−0.714*** (0.257) |

−0.681** (0.270) |

−0.678** (0.270) |

−0.675** (0.270) |

| Malaria control Variables - Interviews | |||||

| Childhood Past Convulsion | −0.089 (0.105) |

−0.086 (0.105) |

−0.088 (0.105) |

−0.087 (0.105) |

−0.087 (0.105) |

| Probability of sleeping under mosquito net the night before the interview |

0.442*** (0.104) |

0.410*** (0.104) |

0.421*** (0.104) |

0.405*** (0.104) |

0.412*** (0.104) |

| Health control | |||||

| Haemoglobin concentration | −0.063** (0.029) |

−0.066** (0.029) |

−0.064** (0.029) |

−0.064** (0.029) |

−0.065** (0.029) |

| Weight for age z-score | 0.127*** (0.039) |

0.131*** (0.039) |

0.125*** (0.039) |

0.124*** (0.039) |

0.126*** (0.039) |

| Height for age z-score | 0.549*** (0.145) |

0.549*** (0.146) |

0.553*** (0.146) |

0.551*** (0.146) |

0.557*** (0.146) |

| Intercept | −3.165*** (0.880) |

−3.028*** (0.887) |

−3.129*** (0.886) |

−3.066*** (0.886) |

−3.089*** (0.887) |

| Number of observations | 1567 | 1567 | 1567 | 1567 | 1567 |

| Number of Children | 227 | 227 | 227 | 227 | 227 |

| R squared | 0.226 | 0.223 | 0.224 | 0.225 | 0.225 |

Notes. - Huber White standard errors are reported in parenthesis. Results are not changed when standard errors are clustered at the household level (not presented here). Reference category for Malarial anemia is no malarial anemia. Other control variables are: mother alive, father alive, age7-age17, grade, sex, religion, ethnicity, convenience property, store-of-value property, capital property, monetary income, savings, informal access to credit, age of the head of houshold, literacy of the head of household, childÕs working hours, time spent on homework, child has somebody to help him with homework. Please refer to Table A5.

denotes statistical significance at the 1% level.

denotes statistical significance at the 5% level.

denotes statistical significance at the 10% level.

Table 5.

Fixed-effects (within child) estimates of the cognitive PCA score.

| Dependant variable is cognitive function PCA score |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed-effects models (within child) |

|||||

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| Asymptomatic Malaria and Malaria Parasitaemia | |||||

| Asymptomatic Malaria (active follow-up) | −0.186*** (0.056) |

||||

| Lagged Asymptomatic Malaria (active follow-up) | −0.109** (0.051) |

||||

| Monthly Geom Mean P. falciparum Parasitaemia (/1000) | . | −0.032*** (0.010) |

|||

| Lagged Monthly Geom Mean P. falciparum Parasitaemia (/1000) | . | −0.019** (0.009) |

|||

| P. falciparum Parasitaemia thresholds (active follow-up) | |||||

| 500 | . | . | −0.277*** (0.063) |

||

| Lagged 500 | . | . | −0.202*** (0.055) |

||

| 1000 | . | . | . | −0.341*** (0.076) |

|

| Lagged 1000 | . | . | . | −0.251*** (0.062) |

|

| 1200 | . | . | . | . | −0.354*** (0.077) |

| Lagged 1200 | . | . | . | . | −0.259*** (0.065) |

| Clinical Malaria control Dummies | |||||

| Clinical Malaria (between two active follow- ups or during active follow-up) |

−0.535*** (0.070) |

−0.542*** (0.070) |

−0.524*** (0.070) |

−0.519*** (0.069) |

−0.515*** (0.069) |

| Lagged Clinical Malaria (between two active follow-ups or during active follow- |

−0.230*** (0.058) |

−0.205*** (0.061) |

−0.224*** (0.058) |

−0.212*** (0.058) |

−0.213*** (0.058) |

| Chronic Malaria and Malaria anemia control Variables | |||||

| Splenomegaly | −0.301*** (0.116) |

−0.250** (0.119) |

−0.235** (0.114) |

−0.239** (0.113) |

−0.234** (0.113) |

| Lagged Splenomegaly | −0.221** (0.103) |

−0.173* (0.104) |

−0.201** (0.102) |

−0.193* (0.102) |

−0.196* (0.102) |

| Malarial anemia | |||||

| Mild | −0.136 (0.091) |

−0.199** (0.089) |

−0.170* (0.087) |

−0.165* (0.089) |

−0.175** (0.088) |

| Moderate | 0.479*** (0.173) |

0.497*** (0.167) |

0.675*** (0.157) |

0.591*** (0.160) |

0.583*** (0.161) |

| Lagged Malarial anemia | |||||

| Mild | −0.142* (0.076) |

−0.183** (0.072) |

−0.140* (0.073) |

−0.137* (0.073) |

−0.144** (0.073) |

| Moderate | −0.313* (0.188) |

−0.318* (0.180) |

−0.253 (0.180) |

−0.236 (0.180) |

−0.231 (0.180) |

| Health control | |||||

| Haemoglobin concentration | −0.024 (0.024) |

−0.028 (0.024) |

−0.027 (0.024) |

−0.027 (0.024) | −0.030 (0.024) |

| Intercept | 0.784*** (0.300) |

0.750** (0.298) |

0.780*** (0.296) |

0.757*** (0.293) |

0.793*** (0.295) |

| Number of observations | 1567 | 1567 | 1567 | 1567 | 1567 |

| Number of Children | 227 | 227 | 227 | 227 | 227 |

| R squared | 0.104 | 0.103 | 0.116 | 0.118 | 0.119 |

| Breush Pagan F-test | 15.34*** | 15.28*** | 15.69*** | 15.69*** | 15.63*** |

| Hausman specification test | 170.56*** | 257.35*** | 259.85*** | 306.52*** | 312.10*** |

Notes. - Huber White standard errors are reported in parenthesis. Results are not changed when standard errors are clustered at the household level (not presented here). Reference category for Malarial anemia is no malarial anemia. Breush Pagan Lagrangian multiplier test for the presence of individual specific effects. The Hausman specification test compares the fixed versus random effects under the null hypothesis that the individual effects are uncorrelated with the other regressors in the model (Hausman, 1978). If correlated (H0 is rejected), a random effect model produces biased estimators, violating one of the Gauss-Markov assumptions; So a fixed effect model is preferred.

denotes statistical significance at t he 1% level.

denotes statistical significance at the 5% level.

denotes statistical significance at the 10% level.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

(a) Mechanisms

The main result of this study is that falciparum malaria parasites affect educational achievement. Children with clinical malaria and asymptomatic malaria had significantly lower achievement test scores. Clinical malaria was also the most common cause of absence from school. The short-term impact of malaria seems to be a more important determinant of reduced human capital accumulation than other health determinants. This underestimated effect should be taken into account more seriously by policy makers in national education programs and school health programs.

Asymptomatic malaria has less effect on cognitive abilities than clinical malaria. The main pathway identified for the effects of asymptomatic malaria is the presence of falciparum malaria parasites. It is not that there is no mechanism for the effect but rather that the mechanism is different from those investigated in this study. Falciparum malaria parasite is probably the epicenter of a chain of events but the mechanism is still unknown. The role of splenomegaly and anemia in lowering the cognitive performance of children needs further study.

The results also provide evidence of the lasting effect of malaria on academic performance and educational achievement. The effects of malaria parasitaemia, asymptomatic malaria and clinical malaria on cognitive achievement persist but decrease with time. The effects of parasitaemia increase with the intensity of infection, which suggests a cumulative effect. Cross-sectional and panel results suggest that the use of bed nets may improve educational achievement. Fighting malaria could have a large payoff in terms of improving the primary education of many children in developing countries. This supposition must, however, be treated with care. As already said, sleeping under a mosquito net may be rather a proxy for the way parents look after their children, as we controlled for malaria parasitaemia in the models. Nevertheless, the discussion of this variable is relevant because it leads to the question of causality. One confounding factor that could have an effect both on cognition and parasitaemia could in fact be the way parents look after their children. Should this be the case, the introduction of this variable in Table 4 or the use of fixed effects models in Table 5 should considerably reduce the effect of parasitaemia, which is not the case.

(b) Is the effect causal?

The above analysis suggests that falciparum malaria parasites have a negative effect on cognitive performance, but it cannot prove causality. Indeed, one benefit of panel data is that unobserved variables that do not change over time can be removed from the regression and need not be measured. However, fixed-effects models assume that unobserved variables do not change over time and do not interact with variables that change over time (Glewwe & Miguel, 2008). Furthermore, measurement errors or unmeasured clinical attacks of malaria that could mediate the relationship between parasitaemia and cognitive function cannot be totally excluded.

Fixed effects instrumental variable estimators were not used in this study for three reasons. Firstly, the malariological measurements (especially malaria parasitaemia) during active monthly follow-ups were taken just before the cognitive tests and measured with high precision. Secondly, a reverse effect of cognitive performance on the malaria indices is unlikely. Thirdly, taking into account the study design, the only candidates for instrumental variables were entomological (eg number of infective bites) which in practice cannot be collected per child and per month.

Nevertheless, the following points suggest a causal relationship: these results match other independent studies, biological confirmation of the hypothesis is plausible and has been described in the medical literature, the temporal sequence between cause and effect is appropriate, there is a clear relationship between infection intensity and the magnitude of the effect (the higher the parasitaemia, the higher the negative effect on cognitive score as shown in regressions (3), (4), and (5) of Tables 4 and 5).

(c) External validity of the results

Because the gross enrolment rate in the village is very high (91.96% compared with the official primary school gross enrolment rate in Mali of 87.58%; official primary school age is 7–12) and very few children drop out from this school, the study only considered the effects of malaria on enrolled children. Secondly, one limitation of this study is that the results are from one specific village in Mali in which the study was conducted. The Malaria Research and Training Centre has offered improved treatment at low cost in the village since the early 1990s. Therefore, it is possible that the absolute value of the effect of malaria is underestimated, as the treatment is supposed to be effective and to improve educational achievement (Clarke et al. 2008). Future investigations should try to go further and test the robustness of these results by following children for a longer period on a larger scale (including several villages, for instance). Thirdly, the definition of cognitive impairment varies considerably between studies and there are also considerable differences in the assessment tools used. This is due to the need to adapt the tests to local circumstances. However, the main objective of this study was to assess the effects of malaria on educational achievement and the cognitive function score used in this study is highly correlated with routine school marks given by teachers according to the national education program.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Comments:

We especially thank the children of Donéguébougou and their families for their cooperation. We are also grateful to François Gros for his support, Matthew Jukes for his help on cognitive assessment of pupils, Martine Audibert and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments, Donéguébougou school teachers, and the entire MRTC Biostatistics department, particularly Hamadou Coulibaly and Amadou Abathina Touré. Research grants and operational support have been provided by the Fondation Rodolphe & Christophe Mérieux and the National Institute of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The study would not have been possible without the work of Dr. Mohamed Balla Niambélé, Dr. Beh Kamaté, Dr. Ousmane Guindo, and Balla Allasseini. They have been part of the research team since the implementation of the study in Donéguébougou. We are very thankful for their support and investment. Any remaining errors are the authors' alone.

Contributor Information

Josselin Thuilliez, Email: josselinthuilliez@gmail.com, EHESP, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Santé Publique Rennes Cedex, FRANCE.

Mahamadou S Sissoko, Malaria Research and Training Center.

Ousmane B Toure, Malaria Research and Training Center.

Paul Kamate, Malaria Research and Training Center.

Jean-Claude Berthelemy, Professor, CES, Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne.

Ogobara K Doumbo, Professor, Malaria Research and Training Center.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Audibert M, Mathonnat J, Henry MC. Malaria and property accumulation in rice production systems in the savannah zone of Côte d'Ivoire. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2003;8(5):471. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett MS. The statistical conception of mental factors. British Journal of Psychology. 1937;28:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath Y. The production of human capital and the life cycle of earnings. The Journal of Political Economy. 1967;75(4):352–365. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SE, Brooker S, Njagi JK, Njau E, Estambale B, Muchiri E, Magnussen P. Malaria morbidity among school children living in two areas of contrasting transmission in western Kenya. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2004;71(6):732–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SE, Jukes MC, Njagi JK, Khasakhala L, Cundill B, Otido J, Crudder C, Estambale BB, Brooker S. Effect of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria on health and education in schoolchildren: A cluster-randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9633):127–138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61034-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha F, Heckman JJ, Lochner L, Masterov DV. Chapter 12 interpreting the evidence on life cycle skill formation. In: Hanushek E, Welch F, editors. Handbook of the economics of education. Elsevier; 2006. pp. 697–812. [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Stabile M. Child mental health and human capital accumulation: The case of ADHD. Journal of Health Economics. 2006;25(6):1094–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando D, de Silva D, Carter R, Mendis KN, Wickremasinghe R. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of the impact of malaria prevention on the educational attainment of school children. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006;74(3):386–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando D, de Silva D, Wickremasinghe R. Short-term impact of an acute attack of malaria on the cognitive performance of schoolchildren living in a malaria-endemic area of Sri Lanka. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2003a;97(6):633–639. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(03)80093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando D, Wickremasinghe R, Mendis KN, Wickremasinghe AR. Cognitive performance at school entry of children living in malaria-endemic areas of Sri Lanka. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2003b;97(2):161–165. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(03)90107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando SD, Gunawardena DM, Bandara MR, De Silva D, Carter R, Mendis KN, Wickremasinghe AR. The impact of repeated malaria attacks on the school performance of children. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2003c;69(6):582–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data-or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001:115–132. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher J, Wolfe B. Child mental health and human capital accumulation: The case of ADHD revisited. Journal of Health Economics. 2008;27(3):794–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup J, Sachs J. The economic burden of malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64(1_suppl):85–96. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glewwe P, Miguel EA. Chapter 56 the impact of child health and nutrition on education in less developed countries. In: Paul Schultz T, Strauss John A, editors. Handbook of development economics. Elsevier; 2007. pp. 3561–3606. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett L. Spleen measurement in malaria. Journal of the National Malaria Society. 1944;3:121–123. [Google Scholar]

- Holding PA, Kitsao-Wekulo PK. Describing the burden of malaria on child development: What should we be measuring and how should we be measuring it? The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2004;71(90020):71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holding PA, Snow RW. Impact of plasmodium falciparum malaria on performance and learning: Review of the evidence. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2001;64(1–2 Suppl):68–75. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby HG, Skoufias E. Risk, financial markets, and human capital in a developing country. The Review of Economic Studies. 1997:311–335. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison EA, Jamison DT, Hanushek EA. The effects of education quality on income growth and mortality decline. Economics of Education Review. 2007;26(6):771–788. [Google Scholar]

- Jukes MC, Pinder M, Grigorenko EL, Smith HB, Walraven G, Bariau EM, Sternberg RJ, Drake LJ, Milligan P, Cheung YB, Greenwood BM, Bundy DA. Long-term impact of malaria chemoprophylaxis on cognitive abilities and educational attainment: Follow-up of a controlled trial. PLoS Clinical Trials. 2006;1(4):e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz A. Home investments in children. The Journal of Political Economy. 1974;82(2):s111–s131. [Google Scholar]

- Moock PR, Leslie J, Jamison DT. Childhood malnutrition and schooling in the Terai region of Nepal. Journal of Development Economics. 1986;20(1):33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Muller O, Traore C, Jahn A, Becher H. Severe anaemia in west African children: Malaria or malnutrition? Lancet. 2003;361(9351):86–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12154-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nokes C, Grantham-McGregor SM, Sawyer AW, Cooper ES, Robinson BA, Bundy DAP. Moderate to heavy infections of trichuris trichiura affect cognitive function in Jamaican school children. Parasitology. 1992;104(3):539–547. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000063800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong'Echa JM, Keller CC, Were T, Ouma C, Otieno RO, Landis-Lewis Z, Ochiel D, Slingluff JL, Mogere S, Ogonji GA, Orago AS, Vulule JM, Kaplan SS, Day RD, Perkins DJ. Parasitemia, anemia, and malarial anemia in infants and young children in a rural holoendemic plasmodium falciparum transmission area. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006;74(3):376–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuell JT. Cognitive conceptions of learning. Review of educational research. 1986;56(4):411–436. [Google Scholar]

- Thuilliez J. L’impact du paludisme sur l’éducation primaire: Une analyse en coupe transversale des taux de redoublement et d’achèvement. Revue d’Économie Du Développement. 2009;23(1–2):161–201. [Google Scholar]

- Todd PE, Wolpin KI. The production of cognitive achievement in children: home, school, and racial test score gaps. Journal of Human Capital. 2007;1(1):91–136. [Google Scholar]

- Trape JF, Peelman P, Morault-Peelman B. Criteria for diagnosing clinical malaria among a semi-immune population exposed to intense and perennial transmission. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1985;79(4):435–442. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.