Abstract

The ribosomal S6 kinase 2 (RSK2) is a well-known serine/threonine kinase and a member of the p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (p90RSK) family of proteins. It is activated downstream of the MEK/ERKs cascade by mitogenic stimuli such as EGF or TPA. Here, we show that RSK2 is activated by treatment with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and directly phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32, leading to IκBα degradation. The phosphorylation of IκBα promotes the activation and translocation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) subunits p65 and p50 to the nucleus. The net result is an increased NF-κB activity, which serves as a mechanism for RSK2 blockade of TNF-α-induced apoptosis and enhanced cell survival.—Peng, C., Cho, Y.-Y., Zhu, F., Xu, Y.-M., Wen, W., Ma, W.-Y., Bode, A. M., Dong, Z. RSK2 mediates NF-κB activity through the phosphorylation of IκBα in the TNF-R1 pathway.

Keywords: apoptosis, cell survival, serine/threonine kinases, tumor promoter

The inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) is secreted primarily by macrophages and participates in multiple cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, inflammation, immunity, and cell death (1,2,3). Obviously, the biological roles of TNF-α are varied and somewhat contradictory. For example, TNF-α is known to induce apoptosis (4, 5); however, TNF-α also activates the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway, which reportedly suppresses apoptosis to promote cell survival (6,7,8,9). Deregulation of TNF-α signaling is believed to be involved in a variety of human diseases, including cancer.

TNF-α exerts its biological functions by binding to its cognate membrane receptors, the TNF-α type 1 receptor (TNF-R1) and type 2 receptor (TNF-R2). TNF-R1 is expressed in most cell types, whereas TNF-R2 expression is found mainly in immune cells (10, 11). The difference between the two receptors is the presence of the death domain (DD) in the TNF-R1 but not in the TNF-R2. Thus, only the TNF-R1 can induce apoptotic cell death as a member of the death receptor family (12).

The NF-κB transcription factor comprises 5 members that include p50, p52, p65 (RelA), c-Rel, and RelB (13). Without cellular stimulation, NF-κB dimers are retained in the cytoplasm by binding to specific inhibitor proteins known as inhibitors of NF-κBs (IκBs) (14, 15). Stimulation of TNF-R1 with TNF-α induces the formation of a complex (i.e., complex I) composed of tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1-associated DEATH domain protein (TRADD), kinase receptor interacting protein (RIP1), and TNF receptor (TNFR)-associated factor 2/5 (TRAF2/5), and this complex leads to activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. In addition, a complex II is formed that includes the adaptor protein Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD). Complex II can recruit and activate caspase-8, thereby triggering apoptosis (16). The activated IKK(α/β) phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32 and Ser-36, which results in the rapid degradation of IκBα by creating a binding site for the SCFβTrCP ubiquitin ligase complex (17). Following IκBα degradation, the NF-κB dimers (i.e., p65/p50) translocate to the nucleus where they coordinate the transcriptional activation of several hundred target genes, including a number of antiapoptotic genes (6, 8, 9). The activation of this pathway is a major factor in preventing cell death induced by TNF-α and thus its inhibition might improve the efficacy of apoptosis-inducing cancer therapies.

Ribosomal S6 kinase 2 (RSK2) is a well-known serine/theronine kinase and a member of the p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (p90RSK) family of proteins. It is activated downstream of the MEK/ERKs cascade. Substrates of RSK2 include c-Fos (18), histone H3 (19, 20), death-associated protein (DAP) kinase (21), Bad (22), Myt1 (23), cAMP response element binding protein (24), ATF4 (25), nuclear factor of activated T cells (26), and p53 (27). RSK2 is involved in numerous cellular functions, including proliferation, cell cycle (23, 28), transformation (29), and differentiation (26). Accumulating evidence shows that RSK2 is also involved in cell death and survival (30, 31), but the mechanism is unclear.

Here, we present evidence showing that TNF-α activates RSK2 and that RSK2 phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32 directly, which enhances IκBα degradation. The net result is the translocation and activation of NF-κB subunits p65 and p50 to the nucleus, which increases NF-κB activity to block TNF-α-induced apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies

Chemical reagents, including Tris, NaCl, and SDS for molecular biology and buffer preparation, and cycloheximide (CHX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Human TNF-α was from Roche Diagnostics, and cell culture media and other supplements were obtained from Life Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD, USA). Specific antibodies to detect p65, p50, phospho-IκBα (Ser-32), phospho-IκBα (Ser-32/Ser-36), total IκBα, RSK1, RSK2, phospho-RSK (Ser-380), caspase-3, and caspase-8 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA). Antibodies against TNF-R1, GST, IKK(α/β), and PARP were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-β-actin and anti-Flag were purchased from Sigma- Aldrich. The X-press antibody was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA), and the active RSK2 protein was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (Charlottesville, VA, USA).

Construction of expression vectors

The expression constructs including RSK2 and truncated RSK2 (26) and Flag-IκBα (32) were amplified and used for expression in HEK293 and HeLa cells. The mutant GST-IκBα-S32A and GST-IκBα-S36A were constructed from GST-IκBα-wild-type (WT; Andrew D. Yurochko, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, USA) using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The small interfering RNA (siRNA)-RSK2 was provided by Y.-Y.C. (29).

Cell culture and transfection

RSK2+/+ and RSK2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (29) or human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were each cultured with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Hyclone, San Diego, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. HeLa cells (human cervix adenocarcinoma) were cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics and cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5.0% CO2. Cells were maintained by splitting at 90% confluence, and media were changed every 3 d. When cells reached 50–60% confluence, transfection was performed using JetPEI (Polyplus-Transfection Inc., New York, NY, USA) following the manufacturer’s suggested protocol. The cells were cultured for 36–48 h and then proteins were extracted for further analysis.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Cellular proteins were extracted using Nonidet P-40 cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5% Nonidet P-40; and protease-inhibitor cocktail). For immunoblotting, 30 μg of protein was used with the appropriate specific primary antibody and an alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated secondary antibody and was detected by chemiluminescence (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA). For immunoprecipitation, 400 μg of protein was combined with agarose A/G beads (50% slurry) by rocking at 4°C overnight. The beads were washed, mixed with 6× SDS-sample buffer, boiled, and then resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were detected using the appropriate specific primary antibodies and AP-conjugated secondary antibodies.

In vitro kinase assay

Purified GST-IκBα-WT, GST-IκBα-S32A, and GST-IκBα-S36A were reacted with active RSK2 (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc) in an in vitro kinase assay. Reactions were performed at 30°C for 30 min in a mixture containing 200 μM ATP. Reactions were stopped by adding 6× SDS sample buffer. Samples were boiled and then resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and visualized by Western blotting or Coomassie blue staining. For the RSK2 immunoprecipitation (IP) kinase assay, RSK2-X-press was immunoprecipitated with anti-X-press. The precipitates were incubated with purified GST-IκBα-WT protein as substrate for the in vitro kinase assay, and the reaction products were analyzed by Western blotting with a phospho-IκBα (Ser-32) antibody. For the IKK(α/β) IP kinase assay, IKK(α/β) was immunoprecipitated with anti-IKK(α/β) and the immunocomplexes were incubated with the purified GST-IκBα-WT protein as substrate for the in vitro kinase assay. The reaction products were analyzed by Western blotting with a phospho-IκBα (Ser-32/Ser-36) antibody.

In vitro binding assay

A purified GST-IκBα-WT protein was combined overnight at 4°C with cell lysates that had been transfected with individual RSK2 truncated constructs. Immunoprecipitation was performed using a GST antibody, and the individual RSK2 mutants were detected with the X-press antibody.

Preparation of cytosolic and nuclear fractions

RSK2-knockdown HeLa cells and RSK2+/+ and RSK2−/− MEFs were seeded in 10-cm dishes and cultured to 90–95% confluence. The cells were serum starved for 16 h and then stimulated with TNF-α (25 ng/ml) and harvested at different time points. Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were prepared using the NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents following the manufacturer’s suggested protocols (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Luciferase assay

Cells were transfected with pNF-κB-Luc and phRL-SV-40 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) in the presence of JetpeI. At 20 h post-transfection, cells were serum starved for 16 h and then treated with TNF-α (25 ng/ml) and disrupted in passive lysis buffer. Lysates were analyzed for firefly and Renilla luciferase activities using the dual luciferase assay kit (Promega).

NF-κB EMSA assay and supershift assay

The nuclear fractions were extracted as described above. For the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), 4 μg of nuclear protein was combined with 5× Gel Shift Binding buffer (20% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM EDTA, 250 mM NaCl, and 50 mM Tris-HCl), 0.25 mg/ml poly(dI)·poly(dC), and an IRDye 700-labeled NF-κB oligonucleotide (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA). For the supershift assay, 4 μg of nuclear protein combined with 5× Gel Shift Binding buffer was incubated with 1 μg of anti-p50 or 1 μg of anti-p65 for 30 min at room temperature, and then the IRDye 700-labeled NF-κB oligonucleotide (LI-COR) was added and left for another 20 min. The samples were then loaded on a prerun native gel. The signal was then detected and quantified using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR).

Annexin V staining

Apoptosis was assessed using the annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (MBL International Corp., Watertown, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s suggested protocols. Cells were treated and then harvested and washed with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated for 5 min at room temperature with annexin V-FITC plus propidium iodide. Cells were analyzed by a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

In vitro caspase-8 and caspase-3 activity assays

To determine caspase-8 and caspase-3 activities, si-Mock- or si-RSK2-transfected cells were treated with TNF-α (25 ng/ml) and cyclohexamide (CHX; 10 μg/ml) and harvested at various time points. The proteins were extracted, and 50 μg of protein was used for measuring caspase-8 and -3 activities with the caspase-8 and caspase-3 Colorimetric Assay Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s suggested protocol. The absorbance values (405 nm) were expressed by converting to milligrams of protein.

RESULTS

TNF-α activates RSK2

RSK2 is a well-known downstream serine/threonine kinase of the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK signaling pathway, which is activated by mitogenic stimuli like EGF and TPA. However, the role of RSK2 in the TNF-α signaling pathway is not well studied. We examined the effect of TNF-α on RSK2 signaling by transfecting X-press-tagged RSK2 into HeLa cells and then treating the cells with human TNF-α (25 ng/ml) as described in Materials and Methods. Immunoprecipitation results indicated that treatment with TNF-α caused an increased interaction of RSK2 with the TNF-R1 (Fig. 1A) but was not observed in the IgG control. Similar results were obtained when using anti-TNF-R1 to immunoprecipitate endogenous RSK2 from HeLa cells following stimulation with TNF-α (Fig. 1B). These results suggested that RSK2 might play a role in mediating the TNF-α/TNF-R1 pathway. We also found that treatment of HeLa cells with TNF-α resulted in a dramatic increase in phosphorylation of RSK (Ser-380) at 10 and 30 min (Fig. 1C). To determine whether RSK2 phosphorylation is induced by TNF-α, HeLa cells transfected with RSK2-X-press were serum starved and treated with TNF-α for various times as indicated (Fig. 1D). RSK2-X-press was immunoprecipitated using the X-press antibody and phosphorylation of RSK2 (Ser-386) was detected by anti-phospho-RSK (Ser-380). Western blot results indicated that RSK2 was phosphorylated following TNF-α treatment for 10 or 30 min (Fig. 1D). Overall, the data indicate that TNF-α activates RSK2.

Figure 1.

TNF-α activates RSK2. A) Overexpressed RSK2 interacts with endogenous TNF-R1. RSK2-X-press was transfected into HeLa cells, and 20 h after transfection, cells were serum starved for 16 h. Cells were then treated with human TNF-α (25 ng/ml) for 10 or 30 min. The cell lysate was immunoprecipitated with a TNF-R1 antibody or control IgG, and RSK2-X-press was detected with the X-press antibody. B) Endogenous RSK2 interacts with endogenous TNF-R1. HeLa cells were serum starved for 16 h and then treated with human TNF-α (25 ng/ml) for 10 or 30 min. A HeLa cell extract (400 μg) was then used for immunoprecipitation with a TNF-R1 antibody, and the immunoprecipitated RSK2 was detected with a specific RSK2 antibody. C) TNF-α induces phosphorylation of RSK (Ser-380). HeLa cells were serum starved and treated with TNF-α for various times, and phosphorylation of RSK (Ser-380) was detected by Western blot. D) TNF-α induces phosphorylation of RSK2 (Ser-386). HeLa cells were transfected with RSK2-X-press, and 20 h after transfection, cells were serum starved and treated with TNF-α for various times. RSK2-X-press was immunoprecipitated with the X-press antibody, and phosphorylation of RSK2 (Ser-386) was detected with an antibody against phosphorylated RSK (Ser-380).

RSK2 directly interacts with IκBα

Because NF-κB activity plays a major role in TNF-α mediated apoptosis, we hypothesized that the activation of RSK2 by TNF- α might affect the NF-κB pathway. First, we found that RSK2 directly associates with IκBα. RSK2-X-press was transfected into HEK293 cells, and cell extracts were combined with purified GST-IκBα or GST protein alone. The result showed that RSK2 can bind to GST-IκBα but not to the GST protein alone (Supplemental Fig. 1) in vitro. To identify the domain of RSK2 that binds to IκBα in vitro, we constructed various RSK2-X-press deletion mutants (Fig. 2A) and transfected the individual mutants into HEK293 cells. The individual RSK2 deletion mutants were detected by the X-press antibody. The results showed that full-length RSK2, RSK2-D1 (D1–68), RSK2-D3 (D69–323), or RSK2-D4 (D416–674)—but not RSK2-D2 (D1–415)—coprecipitated with IκBα (Fig. 2B). Thus, IκBα bound to RSK2 at aa 323 to 415 in vitro. To confirm RSK2 binding with IκBα, HeLa cells transfected with RSK2-X-press were treated with human TNF-α (25 ng/ml) and harvested at various times and then IκBα was immunoprecipitated with anti-IκBα. Compared to untreated cells, TNF-α treatment for 10 or 30 min induced a substantial interaction of RSK2 and IκBα (Fig. 2C), indicating that TNF-α treatment promotes the association of RSK2 with IκBα ex vivo. We also cotransfected RSK2 and IκBα into HeLa cells and used the Flag antibody to immunoprecipitate IκBα, and the data showed that RSK2 only bound to IκBα and was not found in the IgG or beads alone control groups (Supplemental Fig. 2). Finally, we showed that IκBα binds to RSK2 at aa 323 to 415 ex vivo (Fig. 2D), which is consistent with the above results.

Figure 2.

RSK2 directly interacts with IκBα. A) Structure and schematic diagrams of RSK2 deletion mutant constructs. B) Identification of the RSK2 protein domain that interacts with IκBα in vitro. Individual RSK2 deletion mutants were each transfected into HEK293 cells. At 36 h post-transfection, respective cell lysates were combined with the purified GST-IκBα protein, and immunoprecipitation was performed with a GST antibody. Individual RSK2 deletion mutants were detected with the X-press antibody. C) RSK2 interacts with IκBα ex vivo. HeLa cells were transfected with RSK2-X-press; at 20 h after transfection, cells were serum starved for 16 h. Cells were then treated with MG-132 (20 μM) for 4 h followed by treatment with human TNF-α (25 ng/ml) for 10 or 30 min. IκBα was immunoprecipitated with an IκBα antibody, and RSK2-X-press was detected with an X-press antibody. D) Identification of the RSK2 protein domain interacting with IκBα ex vivo. Various individual RSK2-X-press deletion mutants and Flag-IκBα were cotransfected into HeLa cells, and cells were serum starved for 16 h. Cells were then treated with MG-132 (20 μM) for 4 h, followed by treatment with human TNF-α (25 ng/ml) for 10 min. The cell extracts were used for immunoprecipitation with a Flag antibody, and the immunoprecipitated RSK2-X-press was detected with the X-press antibody.

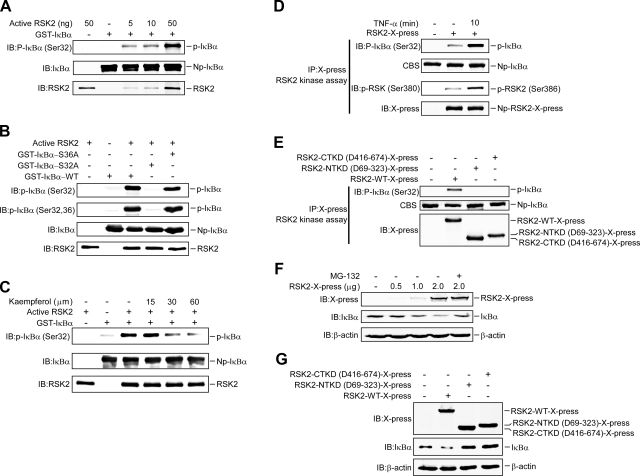

RSK2 phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32

Based on the data showing that RSK2 interacts with IκBα in vitro and ex vivo, we hypothesized that IκBα might be a novel substrate for RSK2. To determine whether RSK2 can phosphorylate IκBα, in vitro kinase reactions using active RSK2 and GST-IκBα as substrate were performed. The results showed that phosphorylation of IκBα (Ser-32) was increased in a dose-dependent manner with increasing amounts of active RSK2 (Fig. 3A). Even at the lowest dose of active RSK2 (5 ng), phosphorylation of IκBα (Ser-32) was detectable. Ser-32 and Ser-36 are critical phosphorylation sites for IκBα that are associated with its targeted degradation. To determine whether either Ser-32 or Ser-36 of IκBα is phosphorylated by RSK2, we replaced each of the two phosphorylation sites (Ser-32/Ser-36) of IκBα with alanine. The GST-mutant IκBα proteins (IκBα-S32A, IκBα-S36A) were expressed and purified individually in BL21 E. coli. We then performed in vitro kinase reactions using active RSK2 and the IκBα-WT or individual IκBα mutants as substrates. Two different antibodies, one that recognizes only Ser-32 and another that recognizes both Ser-32 and Ser-36, were used to detect the phosphorylation of IκBα. The results showed that with the phospho-IκBα (Ser-32) antibody, phosphorylation of GST-IκBα-WT, and mutant GST-IκBα-S36A—but not mutant GST-IκBα-S32A—was detectable (Fig. 3B). Also, the phospho-IκBα (Ser-32/Ser-36) antibody detected only phosphorylation of GST-IκBα-WT and GST-IκBα-S36A but not GST-IκBα-S32A (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that RSK2 phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32 only and not at Ser-36.

Figure 3.

RSK2 phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32 and promotes IκBα degradation. A) RSK2 phosphorylates IκBα in vitro. The wild-type GST-IκBα protein (500 ng) was purified from BL21 bacteria and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay with different amounts of active RSK2 (0, 5, 10, or 50 ng) and 200 μM ATP. The reaction mixture was resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, and the phosphorylated IκBα was visualized by Western blot with a specific phospho-IκBα (Ser-32) antibody. B) Ser-32, but not Ser-36, is phosphorylated by RSK2. The GST-IκBα-WT or mutant GST-IκBα-S32A and GST-IκBα-S36A proteins were expressed and purified individually in E. coli BL21. In vitro kinase reactions were performed using active RSK2 and IκBα-WT or individual IκBα mutants (IκBα-S32A, IκBα-S36A) as substrates. Two different antibodies, one that recognizes only Ser-32 and the other that recognizes both Ser-32 and Ser-36, were used to detect the phosphorylation of IκBα. C) Kaempferol inhibits RSK2-mediated IκBα phosphorylation in vitro. An in vitro kinase assay was conducted with active RSK2 (50 ng), GST-IκBα (500 ng), 200 μM unlabeled ATP, and the indicated dose of kaempferol. Phosphorylated IκBα was visualized by Western blot using a phospho-IκBα (Ser-32) antibody. D) RSK2 is confirmed to phosphorylate IκBα. RSK2-X-press was transfected into HeLa cells, and 20 h after transfection, cells were serum starved for 16 h. RSK2-X-press was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates that were treated with TNF-α for 10 min. The immunocomplexes were incubated with GST-IκBα as substrate for an in vitro kinase assay. Phosphorylated IκBα was visualized by Western blot using a phospho-IκBα (Ser-32) antibody. Detection of phosphorylation of RSK2 was performed to verify RSK2 activity. E) Only RSK2-WT, not RSK2-NTKD (N-terminal domain deletion mutant) or RSK2-CTKD (C-terminal domain deletion mutant), can phosphorylate IκBα. The RSK2-X-press variants were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates that were transfected with RSK2-WT, RSK2-NTKD, or RSK2-CTKD. The complexes were used to react with GST-IκBα for an in vitro kinase assay. F) RSK2 affects IκBα stability. Increasing amounts of RSK2 were transfected into HeLa cells, and 20 h after transfection, cells were serum starved for 16 h and then treated or not treated with MG-132 (20 μM) for 4 h. Western blotting was performed to detect endogenous IκBα. G) RSK2-WT, but not RSK2-NTKD or RSK2-CTKD, promotes IκBα degradation. RSK2-WT, RSK2-NTKD, and RSK2-CTKD were individually transfected into HeLa cells and treated as in F. Western-blot was performed to detect endogenous IκBα. p, phosphorylated; Np, nonphosphorylated or total protein.

Kaempferol has been shown to inhibit RSK2 activity specifically (29); therefore, kaempferol should suppress the phosphorylation of IκBα by RSK2. In this case, the results showed that kaempferol (30 or 60 μM) attenuated RSK2-induced phosphorylation of IκBα (Fig. 3C). To confirm that RSK2 phosphorylates IκBα further, RSK2-X-press was transfected into HeLa cells as before; and cells were treated with TNF-α for 10 min and RSK2 was immunoprecipitated with anti-X-press. The immunocomplexes were incubated with GST-IκBα, and results showed that after TNF-α treatment, phosphorylation of IκBα increased dramatically (Fig. 3D), which corresponded with increased phosphorylation of RSK2 (Ser-386), indicating RSK2 activity (Fig. 3D). We next used cells transfected with wild-type RSK2 (RSK2-WT), N-terminal kinase domain deletion mutant 69–323 (RSK2-NTKD), or C-terminal kinase domain deletion mutant 416–674 (RSK2-CTKD) to test the ability of these two RSK2 mutants to phosphorylate IκBα. Anti-X-press was used to immunoprecipitate the RSK2 proteins and the complexes were reacted with GST-IκBα in an in vitro kinase assay. Results showed that neither the RSK2-NTKD nor the RSK2-CTKD could phosphorylate IκBα, compared with RSK2-WT (Fig. 3E).

Ser-32 is a well-known phosphorylation site that has an effect on IκBα stability. To determine whether RSK2 phosphorylation affects IκBα stability, increasing amounts of RSK2 were transfected into HeLa cells. After transfection, cells were treated or not treated with MG-132 (a proteasome inhibitor, 20 μM). The results indicated that IκBα protein expression was decreased in a dose-dependent manner in the presence of increasing amounts of RSK2, and MG-132 could rescue the expression of IκBα (Fig. 3F). Moreover, cells expressing mutant RSK2-NTKD or RSK2-CTKD expressed high levels of IκBα compared with cells expressing Mock or RSK2-WT (Fig. 3G), further confirming that RSK2 phosphorylation of IκBα promotes IκBα degradation.

RSK2 promotes NF-κB activation in the presence of TNF-α

We constructed HeLa cells stably expressing knockdown of RSK2. In knockdown RSK2 HeLa cells, only RSK2—but not RSK1—decreased dramatically compared with control (si-Mock) cells (Fig. 4A). Knockdown RSK2 cells were serum starved for 16 h and then treated with TNF-α and harvested at different time points. Cytosolic and nuclear protein fractions were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. In the cytosolic fraction, phosphorylated IκBα (Ser-32) was decreased dramatically in si-RSK2 cells, compared with si-Mock cells (Fig. 4B, top panels), which further indicated that RSK2 phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32. In the nuclear fraction, translocation of p65 and p50 in si-Mock cells occurred faster than in si-RSK2 cells (Fig. 4B, bottom panels). The same nuclear extracts were used for electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) and supershift assays. EMSA results indicated that greater NF-κB DNA-binding activity was observed in si-Mock cells compared to si-RSK2 cells (Fig. 4C, lanes 1–6). The supershift assay data showed that the DNA-protein complex was shifted upward in the presence of anti-p50 (Fig. 4C, lanes 7–12) or anti-p65 (Fig. 4C, lanes 13–18). The DNA binding was also inhibited in the RSK2-knockdown cells (Fig. 4C, lanes 7–18). We next cotransfected the NF-κB- and Renilla-luciferase reporter plasmid and the Renilla gene into si-Mock and si-RSK2 cells to assess NF-κB transcriptional activity. These results indicated that significantly higher NF-κB transcriptional activity was observed in si-Mock cells compared with si-RSK2 cells (Fig. 4D). Overall, similar results (Fig. 4E–G) were obtained for RSK2 wild-type (RSK2+/+) and knockout (RSK2−/−) murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in that almost no phosphorylation of IκBα (Ser-32) (Fig. 4E) or translocation of p65 or p50 (Fig. 4F) was detectable in RSK2−/− cells compared to RSK2+/+ MEFs. In addition, NF-κB DNA-binding activity (Fig. 4F, lanes 1–6) was dramatically down-regulated in RSK2−/− MEFs. Notably, the DNA-protein complex was shifted upward in the presence of anti-p50 (Fig. 4F, lanes 7–9) or anti-p65 (Fig. 4F, lanes 10–12) only in the RSK2 wild-type cells. NF-κB transcriptional activity (Fig. 4G) was also greatly reduced in RSK2−/− MEFs compared to RSK2+/+ MEFs.

Figure 4.

RSK2 phosphorylates IκBα ex vivo and controls NF-κB activity. A) Construction of the RSK2-knockdown stable cell line. HeLa cells were transfected with si-Mock or si-RSK2, selected in the presence of G418 (800 μg/ml) for 14 d, and colonies were pooled. Western blotting aimed to detect RSK1 and RSK2 expression in RSK2-knockdown cells, and β-actin served as a loading control. B) RSK2 phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32 ex vivo and promotes p65 and p50 translocation. Knockdown RSK2 HeLa cells were serum starved for 16 h and treated with TNF-α for 10 or 30 min as indicated, and then cytosolic and nuclear fractions were isolated. In the cytosol, phosphorylation of IκBα and RSK2 was detected with specific antibodies, and β-actin was used as a cytosolic protein marker and loading control. In the nuclear fraction, p65, p50, and RSK2 were detected with specific antibodies. PARP served as a nuclear protein marker and loading control. C) RSK2 promotes NF-κB DNA-binding activity. For gel-shift assays (EMSA), the same nuclear extracts from B were incubated with an NF-κB DNA consensus sequence for 20 min (lanes 1–6). For the supershift assay, nuclear extracts were first incubated with anti-p50 (lanes 7–12) or anti-p65 (lanes 13–18) for 30 min and then incubated with an NF-κB DNA consensus sequence for another 20 min. The shifted DNA-bound NF-κB p50/p65 heterodimer is indicated. D) RSK2 controls NF-κB transcriptional activity. Si-mock and si-RSK2 cells were cotransfected with a plasmid mixture containing the NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmid (0.4 μg) and the Renilla-luciferase plasmid (0.2 μg) for normalization. At 20 h post-transfection, cells were starved for 16 h and treated with TNF-α for 2 or 4 h as indicated. The firefly luciferase activity was determined in cell lysates and normalized. Significant differences were evaluated using the Student’s t test, and the respective asterisks indicate a significant difference (P<0.05). E) RSK2 wild-type (RSK2+/+) and knockout (RSK2−/−) murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were serum starved for 16 h and treated with TNF-α for 10 or 30 min as indicated, and then cytosolic and nuclear fractions were prepared. In the cytosolic fraction, phosphorylation of IκBα and RSK2 was detected by a phospho-IκBα (Ser-32) or RSK2 antibody, respectively. β-Actin was used as a cytosolic protein marker and loading control. In the nuclear fraction, p65, p50, or RSK2 was detected with a specific antibody for each. PARP was used as a nuclear protein marker and loading control. F) For gel-shift assays (EMSA), the same nuclear extracts from E were incubated with an NF-κB DNA consensus sequence for 20 min (lanes 1–6). For supershift assays, nuclear extracts were first incubated with anti-p50 (lanes 7–9) or anti-p65 (lanes 10–12) for 30 min and then incubated with an NF-κB DNA consensus sequence for another 20 min. The shifted DNA-bound NF-κB p50/p65 heterodimer is indicated. G) RSK2+/+ and RSK2−/− MEFs were cotransfected with a plasmid mixture containing the NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmid (0.8 μg) and the Renilla-luciferase plasmid (0.2 μg) for normalization. At 20 h post-transfection, cells were starved for 16 h and treated with TNF-α for 10 or 30 min as indicated. The firefly luciferase activity was determined in cell lysates and normalized. *P < 0.05; Student’s t test.

Although we showed that RSK2 directly phosphorylates IκBα in vitro and ex vivo, IKK(α/β) is the most well known kinase to phosphorylate IκBα at Ser-32 and Ser-36 in the TNF-R1 pathway. Thus, we wanted to know whether RSK2 affected IKK(α/β) activity. The IKK(α/β) proteins were immunoprecipitated from si-Mock and si-RSK2 HeLa cell lysates that were treated with TNF-α for different periods. The IKK(α/β) proteins were reacted with GST-IκBα as substrate in an in vitro kinase assay. Results showed no dramatic difference in the ability of IKK(α/β) to phosphorylate IκBα (Ser-32/Ser-36) in si-Mock or si-RSK2 cells (Supplemental Fig. 3A). Overexpressing RSK2 also had little effect on the ability of IKK(α/β) to phosphorylate IκBα (Ser-32/Ser-36) (Supplemental Fig. 3B), suggesting that RSK2 has no effect on IKK(α/β) activity. Collectively, these data clearly indicate that RSK2 phosphorylation of IκBα is associated with increased IκBα degradation and promotes the translocation of the NF-κB subunits, p65 and p50, to the nucleus leading to enhanced NF-κB transcriptional activity.

RSK2 blocks TNF-α-induced apoptosis

Si-Mock and si-RSK2 cells were treated with TNF-α plus CHX for the indicated time periods and apoptosis was assessed by Annexin V staining and flow cytometry. The results showed that silencing RSK2 sensitized HeLa cells to TNF-α- plus CHX-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5A). Additional assays indicated that the activities of caspase-8 and -3 were increased in RSK2-knockdown cells (Fig. 5B), and the cleavage of caspase-8 and caspase-3 was also increased (Fig. 5C). In contrast, if RSK2 was overexpressed, then the cleavage of caspase-8 and caspase-3 was decreased (Fig. 5D). Kaempferol is an inhibitor of RSK2 activity, and we determined the effect of kaempferol on TNF-α-induced apoptosis. Results indicated that TNF-α plus kaempferol (Ka; 30 or 60 μM) induces significant apoptosis (Supplemental Fig. 4A) and increased cleavage of caspase-8 and caspase-3 (Supplemental Fig. 4B, C), compared to treatment with TNF-α or kaempferol only.

Figure 5.

RSK2 attenuates TNF-α-induced apoptosis. A) Knockdown of RSK2 enhances apoptosis induced by TNF-α stimulation. Si-mock and si-RSK2 cells were treated with TNF-α (25 ng/ml) and CHX (10 μg/ml) for 4 h, after which apoptosis was analyzed by Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining using flow cytometry. Data represent percentage of annexin V-positive cells. B) RSK2 knockdown increases caspase-8 and caspase-3 activities. Knockdown RSK2 stable cells were treated with TNF-α (25 ng/ml) and CHX (10 μg/ml) and harvested at 2 or 4 h. The proteins were extracted, and 50 μg of protein were used for measuring caspase-8 and -3 activities, using the caspase-8 and caspase-3 Colorimetric Assay Kit (Millipore). Data represent caspase activity, expressed as absorbance. C) Knockdown of RSK2 enhances cleavage of caspase-8 and caspase-3. Cells were transfected with si-Mock or si-RSK2 and treated with TNF-α (25 ng/ml) and CHX (10 μg/ml) for 2 or 4 h as indicated. The cleavage of caspase-8 and caspase-3 was visualized with specific antibodies by Western blot, and β-actin was used as an internal control to confirm equal protein loading. D) RSK2 suppresses cleavage of caspase-8 and caspase-3. HeLa cells were transfected with RSK2-X-press, cultured for 30 h, treated with TNF-α (25 ng/ml) and CHX (10 μg/ml) for different time periods as indicated, and the cleavage of caspase-8 and caspase-3 was visualized by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as an internal control to confirm equal protein loading. Values are means ± sd from triplicate experiments. *P < 0.05; Student’s t test.

DISCUSSION

RSKs comprise a family of serine/threonine kinases consisting of 4 human isoforms (RSK1–4), which are downstream of the mitogen-regulated Ras/ERK-MAP kinase signaling pathway. Similar to its other family members, RSK2 has two distinct protein kinase domains—an NH2-terminal catalytic domain (NTD) and a COOH-terminal catalytic domain (CTD)—and a hydrophobic linker region. The N-terminal kinase domain, which belongs to the AGC superfamily of kinases, is responsible for phosphorylation of RSK substrates (33, 34), and the C-terminal kinase domain is reported to autophosphorylate RSK (35).

A model depicting RSK activation shows that, after mitogen stimulation, Thr-573 (36) in the activation loop of the CTD and Thr-359 and Ser-363 (37) in the linker region are phosphorylated by ERK1/2. Activation of the CTD leads to autophosphorylation at Ser-380 (38). After phosphorylation of Ser-380, a docking site that recruits PDK1 is created (39, 40). PDK1 phosphorylates Ser-221 at the NTD (41) and activates RSK. Thus, phosphorylation of RSK at Ser-380 is critical for RSK activity.

RSK2 activation by mitogens, such as EGF or TPA, is fairly well understood. However, the role of RSK2 when stimulated by inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α is poorly understood. We found that RSK2 interacts with TNF-R1 (Fig. 1A, B), which suggests that RSK2 might have a role in mediating the TNF-R1 pathway. We showed that TNF-α induces RSK2 phosphorylation at Ser-386 (Fig. 1C, D), which is a critical activation site for RSK2 to phosphorylate its various substrates (Fig. 3D). Further study is needed to determine whether the interaction between RSK2 and TNF-R1 is a direct or indirect interaction and to elucidate the mechanism for TNF-α activation of RSK2.

Phosphorylation of Ser-32 has been shown to be crucial for ubiquitination and degradation of IκBα and translocation and activation of NF-κB. Mutant IκBα (Ser-32) cannot be phosphorylated or degraded, which results in an inactive NF-κB (42, 43). We showed that RSK2 could bind to IκBα directly (Fig. 2B), which was at least partially dependent on TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 2C). Notably, RSK2 could directly phosphorylate IκBα at Ser-32 (Fig. 3B, D) but not at Ser-36 in vitro. We also demonstrated that phosphorylation of IκBα at Ser-32 decreased dramatically in both RSK2-knockdown cells (Fig. 4B) and RSK2−/− MEFs (Fig. 4E). In addition, the full-length wild-type RSK2, but not the NTKD (aa 69–323) or the CTKD (aa 416–674), could phosphorylate IκBα. This result is consistent with the RSK2 activation model that demonstrates both the C-terminal and N-terminal kinse domains are critical to the activation of RSK2. The deletion of either results in inactivation of RSK2. We found that RSK2 induces IκBα degradation and that the degradation was prevented by the proteasome inhibitor, MG-132 (Fig. 3F). Moreover, IκBα expression was maintained at a considerably higher level in cells transfected with mutant RSK2-NTKD or RSK2-CTKD, compared with cells transfected with Mock or RSK2-WT (Fig. 3G). Even though both of these mutants could bind to IκBα (Fig. 2B, D), neither could phosphorylate IκBα, and thus could not target it for degradation.

Similar to the JNK family of proteins (44,45,46), RSK1, RSK2, and RSK3 have a high degree of homology but appear to have very distinct functions. RSK3 was reported to act as a tumor suppressor (47). Suppressing the expression of RSK2, but not RSK1, in fibroblast growth factor receptor-3-expressing human myeloma cells can induce apoptosis (31), which suggests that RSK2 might act as an oncokinase.

IκBα has a crucial role in controlling NF-κB activity through its cytoplasmic sequestration of the various NF-κB subunits. After phosphorylation at Ser-32 and Ser-36, IκBα undergoes proteasome-mediated degradation and releases NF-κB, which is then translocated into the nucleus. We showed that RSK2 promotes NF-κB subunit p65 and p50 translocation to the nucleus (Fig. 4B, E) and increases NF-κB DNA binding activity (Fig. 4C, lanes 1–6, and Fig. 4F, lanes 1–6) and mediates NF-κB transcriptional activity (Fig. 4D, G). In addition, supershift assay results showed that the DNA-protein complex is an NF-κB p50/p65 heterodimer. IKK(α/β) is known to phosphorylate IκBα at Ser-32/Ser-36 in the presence of TNF-α to induce IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation. Our data showed that RSK2 could directly phosphorylate IκBα at Ser-32 to induce its degradation and activate NF-κB. Notably, RSK2 had no effect on IKK(α/β) activity (Supplemental Fig. 3). Although the Ikkα/β complex is the most well known kinase for IκBα phosphorylation and NF-κB activation, our data clearly showed that phosphorylation of IκBα and NF-κB activation were reduced in RSK2-knockdown cells and RSK2−/− MEFs, which indicated that the Ikkα/β complex cannot compensate for the role of RSK2 in the TNF-R1 pathway. TNF-α stimulation appears to either induce apoptosis or promote cell survival, a choice that apparently depends on the balance of activation of the NF-κB pathway. Our data indicated that RSK2 expression can block TNF-α-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5A–D), and the RSK2 inhibitor, kaempferol, sensitizes cells to TNF-α-induced apoptosis (Supplemental Fig. 4A–C). Overall, we show that IκBα is phosphorylated by RSK2 in the presence of TNF-α and that RSK2 blocks TNF-α-induced apoptosis through its mediation of NF-κB activity by direct phosphorylation of IκBα to promote degradation of IκBα. The net result is a blockade of TNF-α-induced apoptosis and increased cell survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Hormel Foundation and U.S. National Institutes of Health grants CA077646, CA111536, CA120388, R37CA081064, and ES016548.

References

- Kwon B, Kim B S, Cho H R, Park J E, Kwon B S. Involvement of tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily(TNFRSF) members in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2003;35:8–16. doi: 10.1038/emm.2003.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locksley R M, Killeen N, Lenardo M J. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104:487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Goeddel D V. TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science. 2002;296:1634–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Stagg J, Yagita H, Okumura K, Smyth M J. Targeting death-inducing receptors in cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2007;26:3745–3757. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A. Targeting death and decoy receptors of the tumour-necrosis factor superfamily. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:420–430. doi: 10.1038/nrc821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, McKay B S, Allen J B, Jaffe G J. Effect of NF-kappa B inhibition on TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in human RPE cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2438–2446. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler F, Algul H, Paxian S, Schmid R M. Genetic inactivation of RelA/p65 sensitizes adult mouse hepatocytes to TNF-induced apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2489–2503. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima A, Komazawa-Sakon S, Takekawa M, Sasazuki T, Yeh W C, Yagita H, Okumura K, Nakano H. An antiapoptotic protein, c-FLIPL, directly binds to MKK7 and inhibits the JNK pathway. EMBO J. 2006;25:5549–5559. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheau O, Lens S, Gaide O, Alevizopoulos K, Tschopp J. NF-kappaB signals induce the expression of c-FLIP. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5299–5305. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.16.5299-5305.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Yang Y, Ashwell J D. TNF-RII and c-IAP1 mediate ubiquitination and degradation of TRAF2. Nature. 2002;416:345–347. doi: 10.1038/416345a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naismith J H, Sprang S R. Modularity in the TNF-receptor family. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:74–79. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A, Dixit V M. Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109:S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatada E N, Nieters A, Wulczyn F G, Naumann M, Meyer R, Nucifora G, McKeithan T W, Scheidereit C. The ankyrin repeat domains of the NF-kappa B precursor p105 and the protooncogene bcl-3 act as specific inhibitors of NF-kappa B DNA binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2489–2493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C, Van Antwerp D, Hope T J. An N-terminal nuclear export signal is required for the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of IkappaBalpha. EMBO J. 1999;18:6682–6693. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheau O, Tschopp J. Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell. 2003;114:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-κB activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson K D, Taylor L K, Haung L, Burlingame A L, Landreth G E. Transcription factor phosphorylation by pp90(rsk2). Identification of Fos kinase and NGFI-B kinase I as pp90(rsk2) J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3385–3395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassone-Corsi P, Mizzen C A, Cheung P, Crosio C, Monaco L, Jacquot S, Hanauer A, Allis C D. Requirement of Rsk-2 for epidermal growth factor-activated phosphorylation of histone H3. Science. 1999;285:886–891. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan L C, Clayton A L, Hazzalin C A, Thomson S. Phosphorylation and acetylation of histone H3 at inducible genes: two controversies revisited. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;259:102–111. discussion 111–104, 163–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjum R, Roux P P, Ballif B A, Gygi S P, Blenis J. The tumor suppressor DAP kinase is a target of RSK-mediated survival signaling. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1762–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonni A, Brunet A, West A E, Datta S R, Takasu M A, Greenberg M E. Cell survival promoted by the Ras-MAPK signaling pathway by transcription-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Science. 1999;286:1358–1362. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A, Gavin A C, Nebreda A R. A link between MAP kinase and p34(cdc2)/cyclin B during oocyte maturation: p90(rsk) phosphorylates and inactivates the p34 (cdc2) inhibitory kinase Myt1. EMBO J. 1998;17:5037–5047. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing J, Ginty D D, Greenberg M E. Coupling of the RAS-MAPK pathway to gene activation by RSK2, a growth factor-regulated CREB kinase. Science. 1996;273:959–963. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Matsuda K, Bialek P, Jacquot S, Masuoka H C, Schinke T, Li L, Brancorsini S, Sassone-Corsi P, Townes T M, Hanauer A, Karsenty G. ATF4 is a substrate of RSK2 and an essential regulator of osteoblast biology; implication for Coffin-Lowry Syndrome. Cell. 2004;117:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y Y, Yao K, Bode A M, Bergen H R, 3rd, Madden B J, Oh S M, Ermakova S, Kang B S, Choi H S, Shim J H, Dong Z. RSK2 mediates muscle cell differentiation through regulation of NFAT3. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8380–8392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611322200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y Y, He Z, Zhang Y, Choi H S, Zhu F, Choi B Y, Kang B S, Ma W Y, Bode A M, Dong Z. The p53 protein is a novel substrate of ribosomal S6 kinase 2 and a critical intermediary for ribosomal S6 kinase 2 and histone H3 interaction. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3596–3603. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard F S, Crouch M F. MEK, ERK, and p90RSK are present on mitotic tubulin in Swiss 3T3 cells: a role for the MAP kinase pathway in regulating mitotic exit. Cell Signal. 2001;13:653–664. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y Y, Yao K, Kim H G, Kang B S, Zheng D, Bode A M, Dong Z. Ribosomal S6 kinase 2 is a key regulator in tumor promoter induced cell transformation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8104–8112. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisinger-Mathason T S, Andrade J, Groehler A L, Clark D E, Muratore-Schroeder T L, Pasic L, Smith J A, Shabanowitz J, Hunt D F, Macara I G, Lannigan D A. Codependent functions of RSK2 and the apoptosis-promoting factor TIA-1 in stress granule assembly and cell survival. Mol Cell. 2008;31:722–736. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Dong S, Gu T L, Guo A, Cohen M S, Lonial S, Khoury H J, Fabbro D, Gilliland D G, Bergsagel P L, Taunton J, Polakiewicz R D, Chen J. FGFR3 activates RSK2 to mediate hematopoietic transformation through tyrosine phosphorylation of RSK2 and activation of the MEK/ERK pathway. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethi G, Ahn K S, Chaturvedi M M, Aggarwal B B. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) activates nuclear factor-kappaB through IkappaBalpha kinase-independent but EGF receptor-kinase dependent tyrosine 42 phosphorylation of IkappaBalpha. Oncogene. 2007;26:7324–7332. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorbaek C, Zhao Y, Moller D E. Divergent functional roles for p90rsk kinase domains. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18848–18852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher T L, Blenis J. Evidence for two catalytically active kinase domains in pp90rsk. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1212–1219. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merienne K, Jacquot S, Zeniou M, Pannetier S, Sassone-Corsi P, Hanauer A. Activation of RSK by UV-light: phosphorylation dynamics and involvement of the MAPK pathway. Oncogene. 2000;19:4221–4229. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J A, Poteet-Smith C E, Malarkey K, Sturgill T W. Identification of an extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) docking site in ribosomal S6 kinase, a sequence critical for activation by ERK in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2893–2898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalby K N, Morrice N, Caudwell F B, Avruch J, Cohen P. Identification of regulatory phosphorylation sites in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated protein kinase-1a/p90rsk that are inducible by MAPK. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1496–1505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vik T A, Ryder J W. Identification of serine 380 as the major site of autophosphorylation of Xenopus pp90rsk. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;235:398–402. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frodin M, Antal T L, Dummler B A, Jensen C J, Deak M, Gammeltoft S, Biondi R M. A phosphoserine/threonine-binding pocket in AGC kinases and PDK1 mediates activation by hydrophobic motif phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2002;21:5396–5407. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frodin M, Jensen C J, Merienne K, Gammeltoft S. A phosphoserine-regulated docking site in the protein kinase RSK2 that recruits and activates PDK1. EMBO J. 2000;19:2924–2934. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen C J, Buch M B, Krag T O, Hemmings B A, Gammeltoft S, Frodin M. 90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase is phosphorylated and activated by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27168–27176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Hagler J, Palombella V J, Melandri F, Scherer D, Ballard D, Maniatis T. Signal-induced site-specific phosphorylation targets I kappa B alpha to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1586–1597. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, Gerstberger S, Carlson L, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U. Control of I kappa B-alpha proteolysis by site-specific, signal-induced phosphorylation. Science. 1995;267:1485–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.7878466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Nomura M, She Q B, Ma W Y, Bode A M, Wang L, Flavell R A, Dong Z. Suppression of skin tumorigenesis in c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase-2-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3908–3912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H S, Bode A M, Shim J H, Lee S Y, Dong Z. JNK1 phosphorylates Myt1 to prevent UVA-induced skin cancer. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;29:2168–2180. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01508-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She Q B, Chen N, Bode A M, Flavell R A, Dong Z. Deficiency of c-Jun-NH(2)-terminal kinase-1 in mice enhances skin tumor development by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1343–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignone P A, Lee K Y, Liu Y, Emilion G, Finch J, Soosay A E, Charnock F M, Beck S, Dunham I, Mungall A J, Ganesan T S. RPS6KA2, a putative tumour suppressor gene at 6q27 in sporadic epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:683–700. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.