Abstract

Progressive decrease in neuronal function is an established feature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Previous studies have shown that amyloid β (Aβ) peptide induces acute increase in spontaneous synaptic activity accompanied by neurotoxicity, and Aβ induces excitotoxic neuronal death by increasing calcium influx mediated by hyperactive α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate (AMPA) receptors. An in vivo study has revealed subpopulations of hyperactive neurons near Aβ plaques in mutant amyloid precursor protein (APP)-transgenic animal model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) that can be normalized by an AMPA receptor antagonist. In the present study, we aim to determine whether soluble Aβ acutely induces hyperactivity of AMPA receptors by a mechanism involving β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR). We found that the soluble Aβ binds to β2AR, and the extracellular N terminus of β2AR is critical for the binding. The binding is required to induce G-protein/cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) signaling, which controls PKA-dependent phosphorylation of GluR1 and β2AR, and AMPA receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs). β2AR and GluR1 also form a complex comprising postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95), PKA and its anchor AKAP150, and protein phosphotase 2A (PP2A). Both the third intracellular (i3) loop and C terminus of β2AR are required for the β2AR/AMPA receptor complex. Aβ acutely induces PKA phosphorylation of GluR1 in the complex without affecting the association between two receptors. The present study reveals that non-neurotransmitter Aβ has a binding capacity to β2AR and induces PKA-dependent hyperactivity in AMPA receptors.—Wang, D., Govindaiah, G., Liu, R., De Arcangelis, V., Cox, C. L., Xiang, Y. K. Binding of amyloid β peptide to β2 adrenergic receptor induces PKA-dependent AMPA receptor hyperactivity.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cAMP, EPSC, FRET, GluR1

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is associated with neuronal degeneration, including decreases in the density of cortical synapses (1) and dendritic spines (2). Studies on animal models of AD provide evidence that treatments with soluble amyloid β (Aβ) oligomers for a long time contribute to the down-regulation of synapse strength and density (3,4,5,6,7); however, early modifications induced by Aβ remain controversial. Much effort has been directed toward elucidating synaptotoxic Aβ species (6, 8). The ectopic application of Aβ has generated highly heterogeneous results, ranging from acute increase in spontaneous synaptic activity accompanied by neurotoxicity and intrinsic excitability of neurons (9, 10) to a lack of effect on synaptic transmission (6) or a depression (7, 11). These observations suggest that the oligomeric states of Aβ peptides and treating time differentially affect synaptic function. However, the virtue lack of molecular mechanism, especially cellular targets, for the Aβ cellular effects obstructs understanding of the divergent effects induced by different Aβ oligomeric species in either acute or long-term process.

It has been reported that Aβ induces acute excitotoxic neuronal death resulting from calcium influx blocked by α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate (AMPA) receptor antagonist DNQX (12,13,14). In the brains of human familial mutant amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene-transgenic animals, significant subpopulations of neurons in proximity to Aβ plaques are hyperactive, which is dependent on the presence of amyloid plaques and blocked by AMPA receptor antagonist CNQX (15). The appearance of the neuronal hyperactivity correlates with an impairment of the animal’s learning capability (15), which may be relevant to high soluble Aβ concentration surrounding the plaques due to Aβ species dissociation from the fibrils (16). These data indicate that Aβ can induce acute responses in synaptic function via intracellular signaling systems. At present, molecular targets for soluble Aβ species responsible for acute spontaneous AMPA receptor hyperactivity are still unknown.

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) respond to stimulation of neurotransmitters and hormonal peptides, and induce diversified cellular signaling to modulate synaptic function (17, 18). Increasing evidence indicates that β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR), a prototype GPCR in the CNS adrenergic system, may play an important role in sporadic late-onset AD (19). Recent epidemiological studies have shown that βAR antagonists delay the rate of functional decline and the incidence of AD pathogenesis (19, 20). In recent years, emerging evidence indicates that Aβ may activate cAMP/PKA signaling through β2AR (21,22,23). Protein kinase A (PKA) is one of the key components of β2AR-cAMP/PKA signaling, which phosphorylates downstream substrates to regulate gene expression, cell differentiation, and function of receptors and ion channels (24). Under emotional stress, adrenergic activation increases the PKA phosphorylation of AMPA receptor subunit 1 (GluR1) (25), which controls GluR1 AMPA receptor function (26). Thus, Aβ-induced activities of β adrenergic and AMPA receptors may contribute to common psychiatric symptoms such as agitation/aggression in AD patients (27, 28).

In the present study, we aim to find whether β2AR is involved in Aβ1-42-induced cellular effects on neurons. We have found that soluble Aβ1-42 binds to β2AR and initiates the β2AR-cAMP/PKA signaling leading to enhanced AMPA receptor-mediated spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in prefrontal cortical (PFC) neurons, by increasing PKA-dependent phosphorylation of GluR1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Wild type Sprague-Dawley rats (13–19 d old), and wild-type (WT) and β2AR-, β1AR-, β1/β2AR-, or β1/β2/β3AR-gene knockout (KO) mice were used (29). All animal experimental procedures were approved by the University of Illinois Animal Care and Use Committee according to the U.S. National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Primary culture of PFC neurons

Newly born WT and β2AR-, β1AR-, β1/β2AR-, or β1/β2/β3AR-KO mice were used to isolate the PFC neurons under a stereomicroscope (30). The minced cortices were digested with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 0.2 mg/ml cysteine, 0.063% DNase I, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 0.6 mg/ml papain, at 37°C for 20 min to dissociate cells, and the digestions were terminated by adding 10% heat-inactivated horse serum. After centrifugation at 200 g for 5 min, cells were plated on poly-d-lysine-coated dishes at a density of 1.0 × 106 cells/ml in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS, 1% ITS supplement, 25 ng/ml nerve growth factor, 1 mM glutamine, and 20 nM progesterone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Cytosine β-d-arabinofuranoside (2.5 μM; Sigma) was used to inhibit the growth of non-neuronal cells. In addition, human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from WT or βAR gene-deficient mice were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS.

Aβ preparation

Aβ1-42, carboxyfluorescein-Aβ1-42, and amino acid sequence-inversed peptide Aβ42-1 (Biopeptide, San Diego, CA, USA) were initially dissolved at 10−3 M in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma) (31). For aging, Aβ1-42 was dissolved in PBS (pH 7.4) at 10−4 M and incubated at 37°C for 4 d (32).

cDNA constructs

The flag-tagged β2AR and β1AR constructs have been published previously (33, 34). The chimeric β1NT-β2AR, third intracellular (i3) loop mutant β2AR, C-terminal (CT) mutant β2AR, and i3+CT mutant β2AR constructs were created by replacing the corresponding N terminus, the i3 loop, and C terminus of β2AR with that of β1AR through overlapping PCRs. The primers for β1NT-β2AR were 5′-GCGCCGCTGTCGCAGTGGGTTGTGGGCATGGCC/5′-GGCCATGCCCACAACCCACTGCTGCGACAGCGGCGC. The primers for i3 mutant β2AR were 5′-ATGGCCTTCGTCTATTCCCGGGTC/5′-GGAATAGACGAAGGCCARGATGCA for the N-end joint; and 5′-ATGATGATGCCTAAAGTCTTGAG/5′-ACTTTAGGCATCATCATGGGTGTG for the C-end joint. The primers for CT mutant β2AR were 5′-ACTGCCGGAGTCCAGATTTCAGG/5′-GGACTCCGG CAGTAGATGATGGG. The i3+CT mutant β2AR constructs were generated with the primers for CT mutant based on the i3 mutant β2AR template. The PCR products were subcloned back to plasmid pCDNA3.1-flag-β2AR with HindIII/ClaI or ClaI/XbaI sites. All constructs were sequenced and confirmed of expression in HEK293 cells.

Aβ/βAR and ligand/βAR binding assay

HEK293 cells or cells expressing different βARs were lysed with hypotonic buffer; membranes were isolated, as described previously (35), and were then resuspended in binding buffer (75 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 12.5 mM MgCl2; and 1 mM EDTA) (35). For fluorescent Aβ1-42 binding, 2 μg membrane proteins or membrane-free solution as blank was added to 50 μl binding buffer containing 10−5 M carboxyfluorescein (fluo)-Aβ1-42, 0.1% BSA, and 5% DMSO, and was shaken at 4°C for 1 h. After 3 times ultracentrifugation and wash, the membrane-bound fluo-Aβ1-42 was harvested and transferred to 96-well plates to measure fluorescence intensity using a SpectraMax M2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Radioactive receptor-binding assay was carried out as described previously (35). Twenty micrograms of membrane proteins containing β2AR was incubated with 1 nM [3H]dihydroalprenolol (DHA; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) in the presence of 0.1% BSA and different concentrations of Aβ1-42 or isoproterenol (Iso; Sigma). The mixtures were shaken at 230 rpm at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were harvested and rinsed. The membrane-bound [3H]DHA was detected using a Beckman LS 6500 liquid scintillation counter(Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Gsα protein activation assay

Gsα was expressed in Sf9 cells and purified, then reconstituted with or without purified β2AR to lipid bilayers (β2AR:Gsα, 1:5) (29). The reconstituted membranes were suspended at 1 mg/ml in binding buffer. Fifteen micrograms of the membranes was mixed with the binding buffer supplemented with 0.05% BSA and 1 nM [35S]GTPγS (NEN-DuPont, Boston, MA, USA) in a total volume of 500 μl. The mixtures were shaken at 200 rpm for 40 min at 25°C. Membrane-bound [35S]GTPγS was collected, rinsed, and counted using a Beckman LS 6500 liquid scintillation counter.

cAMP assay

WT and gene-deficient MEFs or HEK293 cells expressing human β2AR were serum starved with DMEM containing 0.1% BSA at 37°C for 2 h. Cells were stimulated with drugs for 10 min in the presence of a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX; 0.1 mM; Sigma). The stimulated cells were lysed; cAMP levels were tested using cAMP HTS immunoassay kits (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and normalized against protein concentration in each sample.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) recording

PFC neurons or MEFs were infected with viruses to express PKA activity reporter (AKAR2.2), or together with flag-β2AR to probe PKA activities, using methods described previously (36). Living cells were imaged on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope with a ×40/1.3 NA oil-immersion objective lens and a charge-coupled device camera (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA), controlled by Metafluor software (Molecular Devices). Dual-emission recording of both cyan direct (440/480 nm, ex/em) and FRET (440/535 nm, ex/em) was coordinated by a Lambda 10–3 filter shutter controller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA). Exposure time was 200 ms, and recording interval was 20 s.

In vitro stimulation of PFC slices and HEK293 cells

PFC slices were cut from brain hemispheres at 250-μm sections in a sagittal plane and were dissected out on ice. Antagonists and PKA inhibitors were added 10 min before the administration of Aβ1-42, Iso, or Forsk for 5 min or as indicated. After stimulation, the slices or HEK293 cells were rinsed swiftly with 10 mM PBS containing 50 mM NaF, and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 1 mM Na3VO4; 2 mM EDTA; 2 mM EGTA; 50 mM NaF; 1% Nonidet P-40; 1% sodium deoxycholate; 0.1% SDS; 0.5 mM dl-dithiothreitol; and proteinase inhibitor cocktails), and homogenized using a Sonic Dismembrator 100 (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). An equal amount of total proteins from different samples was resolved by SDS-PAGE for Western blot analysis.

Coimmunoprecipitation

For the precipitation of Aβ with β2AR, HEK293 cells expressing β2AR or β1NT-β2AR were serum starved for 2 h and incubated with Aβ1-42 for 30 min, then washed 3 times. For the precipitation of GluR1 with β2AR, the PFC slices were used. The above cells or PFC slices were homogenized in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 5 mM EDTA; 5 mM EGTA; 50 mM NaF; 1 mM Na3VO4; 50 mM NaCl; 10% glycerol; 1% Triton X-100; 30 mM sodium pyrophosphate; and proteinase inhibitor cocktails). For some experiments, the PFC slices were stimulated with different drugs for 2 min before lysis. The lysates were clarified by ultracentrifugation. The cleared supernatant was then incubated with a purified antibody against β2AR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or a control IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA), and rotated at 4°C for 3 h before precipitation with protein A Sepharose beads. The bound proteins were resolved by 10% Tris-tricine SDS-PAGE for Aβ/β2AR precipitation samples or by Laemmli SDS-PAGE for GluR1/β2AR precipitation samples.

Western blot analysis

Samples resolved in SDS-PAGE were transblotted to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore), and blocked with 5% milk in blocking buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 104 mM NaCl; 25 mM NaF; 8 mM NaN3; and 0.1% Tween 20). The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (1:500–1000) against Aβ, GluR1 phospho-S845, or GluR1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), PKA anchor protein 150 (AKAP150), β2AR, Na+/K+ ATPase, PKA RIIα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), protein phosphatase 2A (BD Transduction Laboratories), or postsynaptic density protein 95 (Affinity BioReagent, Golden, CO, USA) and β2AR phospho-S261/262 (a gift from Dr. Richard Clark, University of Texas Medical School, Houston, TX, USA) at 4°C overnight (37). After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and developed in Supersignal chemiluminescent kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). The optical density of the bands was analyzed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Whole-cell recording procedures

Intracellular recordings, using the whole-cell configuration, were obtained with the visual aid of a microscope (Axioskop 2FS; Zeiss) equipped with differential interference contrast optics, as described previously (38). A low-power objective (×4) was used to identify nuclei within the slice, and a high-power water-immersion objective (×63) was used to visualize individual PFC neurons. Recording pipettes had tip resistances of 3–5 MΩ when filled with recording solution adjusted to pH 7.3 and 290 mosmol. Recordings were obtained from neurons with stable access resistances of <25 MΩ using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). AMPA receptor-mediated EPSCs were recorded using voltage-clamp mode at holding of −70 mV in the presence of NMDA receptor antagonist CPP (20 μm) and sodium channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX; 1 μM). Drugs were applied by injecting a bolus into the input line of the chamber using a motorized syringe pump. The amplitude and frequency of EPSCs were analyzed using a peak detection program (Minianalysis; Synaptosoft, Leonia, NJ, USA).

Statistical analyses

Unpaired or paired t test was used for comparing only 2 groups with Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). A value of P < 0.05 was considered a significant difference.

RESULTS

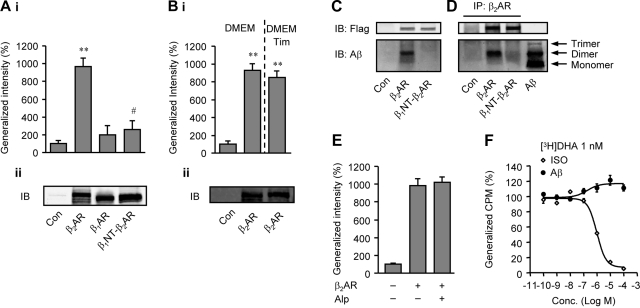

To elucidate the interaction between Aβ1-42 and β2AR, carboxyfluorescein-labeled Aβ1-42 (fluo-Aβ) was used to bind membranes isolated from HEK293 cells expressing flag-βARs. The binding of fluo-Aβ to β2AR membranes was significantly higher than those to control membranes or β1AR membranes, suggesting a specific binding of Aβ1-42 to β2AR (Fig. 1A). A chimeric β2AR, in which the extracellular N terminus was replaced with the N terminus of β1AR (β1NT-β2AR), lost its binding to fluo-Aβ, indicating that the N terminus of β2AR is required for binding to Aβ1-42 (Fig. 1A). Since spontaneous activity of overexpressed β2AR may lead to gene expression for the enhanced fluo-Aβ binding, we isolated membranes from β2AR-overexpressing HEK293 cells cultured in the presence of a βAR antagonist, timolol (10−5 M). Membranes isolated from timolol-treated cells showed similar binding to fluo-Aβ to those without timolol (Fig. 1B), indicating that β2AR activity-induced gene expression unlikely contributes to the Aβ binding. The interaction between Aβ1-42 and β2AR was further confirmed with immunoprecipitation. MEF cells lacking both β1 and β2AR genes were used to express either human β2AR or β1NT-β2AR, and were incubated with Aβ1-42. Aβ1-42 dimer was the primary species detected specifically in the cell lysates containing β2AR, but not β1NT-β2AR (Fig. 1C). Moreover, Aβ1-42 dimer was coimmunoprecipitated from the cell lysate with β2AR, but not β1NT-β2AR (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, while the fluo-Aβ/β2AR binding was blocked by a higher concentration of nonfluorescent Aβ1-42 (Supplemental Fig 1A), the βAR antagonist alprenolol (Alp; 10−6 M) failed to block the binding (Fig. 1E). Accordingly, Aβ failed to compete the binding of [3H]dihydroalprenolol ([3H]DHA) to β2AR, whereas Iso did so (Fig. 1F). These data together suggest that Aβ does not occupy the catechol-binding sites but binds to β2AR via an allosteric site that requires the N terminus of the receptor. In addition, we tested whether the binding of Aβ1-42 to β2AR modulates G protein activity in a reconstituted β2AR-Gsα system (39), in which purified Gsα proteins and β2ARs were reconstituted in lipid bilayers. Aβ1-42 induced a significant increase in [35S]GTPγS binding to Gsα protein, which was blocked by a β2AR-specific antagonist ICI118551, indicating that Aβ1-42 binding leads to receptor/G-protein coupling and activation (Supplemental Fig. 1B). As a control, Gsα protein reconstituted by itself in lipid bilayers did not show an increase in binding to [35S]GTPγS on addition of Aβ1-42 (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Taken together, these results suggest that Aβ1-42 binds to β2AR for G-protein activation to initiate signal transduction.

Figure 1.

Aβ1-42 binds to β2AR expressed in HEK293 cells. A) i) Fluo-Aβ was incubated with HEK293 membranes containing flag-β2AR, flag-β1AR, the chimeric flag-β1NT-β2AR, or the control membrane from WT HEK293 cells. Bound fluo-Aβ was detected. **P < 0.01 vs. control (Con); #P < 0.05 vs. β2AR; unpaired t test, n = 12. ii) Expression of flag-tagged βARs was detected by anti-flag M1 antibody in Western blotting. B) i) Fluo-Aβ was incubated with the control membranes, or membrane containing β2AR from cells pretreated with or without βAR antagonist timolol (Tim; 10−5 M). Bound fluo-Aβ was detected. **P < 0.01 vs. Con. ii) Expression of flag-β2ARs in cell membranes was detected by anti-flag M1 antibody in Western blot analysis. C) β1AR-KOand β2AR-KO MEFs expressing flag-βARs were incubated with Aβ1-42. Cells were washed before being harvested. Aβ and flag-βARs in cell lysates were detected by Western blot analysis. D) From the cell lysates yielded in C, flag-βARs were immunoprecipitated with anti-β2AR antibody against the receptor C-terminal domain; bound Aβ1-42 was detected by Western blot analysis. E) Fluo-Aβ1-42 was incubated with WT HEK293 membranes, or membranes containing flag-β2ARs in the absence or presence of βAR antagonist alprenelol (Alp; 10−5 M). Bound fluo-Aβ was detected. F) [3H]DHA was incubated with HEK293 cell membranes containing flag-β2AR in the absence or presence of different doses of Aβ1-42 or βAR agonist Iso. Bound [3H]DHA was detected.

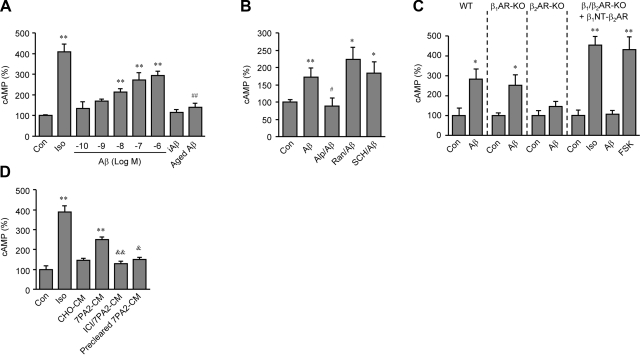

We then characterized intracellular cAMP/PKA signaling induced by Aβ1-42 binding to β2AR. Aβ1-42 induced a dose-dependent accumulation of the second messenger cAMP in HEK293 cells expressing β2AR in 10 min (Fig. 2A). Neither amino acid sequence-inverted peptide iAβ42-1 (10−6 M) nor aged Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) induced cAMP accumulation (Fig. 2A). Aβ1-42-induced cAMP accumulation was selectively blocked by βAR antagonist Alp (10−6 M), indicating an allosteric antagonism of Alp on the Aβ1-42 effect, but not by histamine H2 receptor antagonist ranitidine (Ran, 10−6 M) or dopamine D1 receptor antagonist SCH23390 (SCH, 10−6 M, Fig. 2B). The necessary role of β2AR in the Aβ1-42-induced cAMP was confirmed in MEF cells lacking the β2AR gene. Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) induced significant increases in cAMP accumulation in WT and β1AR-KO MEF cells, but not in β2AR-KO or β1/β2AR-KO cells (Fig. 2C), or in cells lacking all βAR genes (Supplemental Fig. 2A). Moreover, β1/β2AR-KO cells expressing the chimeric β1NT-β2AR lacking the Aβ1-42-binding domain responded to Iso (10−7 M) but not Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) stimulation to produce cAMP (Fig. 2C). In addition, cotreatment with both Iso (10−7 M) and Aβ (10−6 M) induced at least an additive effect on cAMP accumulation (Supplemental Fig. 2B). To know whether naturally secreted Aβ has the same effect as synthetic Aβ1-42, β2AR-overexpressing HEK293 cells were treated with 7PA2-conditioned medium (7PA2-CM) containing naturally secreted Aβ from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells carrying human APP gene with V717F mutation (Supplemental Fig. 2C and ref. 40). 7PA2-CM induced cAMP accumulation, and the effect was blocked by β2AR antagonist ICI118551 (10−6 M, Fig. 2D). Control CHO-CM and precleared 7PA2-CM, in which Aβ had been immunodepleted with antibody, did not show significant effects on cAMP accumulation (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Aβ1-42 induces a β2AR-dependent increase in cAMP accumulation. A) cAMP accumulation was detected in HEK293 cells expressing flag-β2AR after treatments with different doses of Aβ1-42 (10−10 to 10−6 M; log EC50=−7.207), or after treatment with inversed Aβ (iAβ42-1; 10−6 M), aged Aβ1-42 (10−6 M), or Iso (10−7 M). B) cAMP accumulation in WT MEFs was detected after treatment with Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) in the absence and presence of βAR antagonist Alp (10−6 M), histamine H1 receptor antagonist ranitidine (Ran, 10−6 M), or dopamine D1 receptor antagonist SCH23390 (SCH, 10−6 M). C) cAMP accumulation in WT, β1AR-KO, β2AR-KO, or β1/β2AR-KO MEFs, or the β1/β2AR-KO MEFs expressing chimeric β1NT-β2AR, was detected after stimulation with Aβ1-42 (10−6 M), Iso (10−7 M), or forskolin (FSK, 10−5 M). D) cAMP accumulation in HEK293 cells expressing β2AR was detected after treatment with 7PA2-CM in the absence or presence of β2AR antagonist ICI118551 (ICI; 10−6 M), or treatment with control CHO-CM or precleared 7PA2-CM. **P < 0.01 vs. control (Con.); #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. Aβ; &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01 vs. 7PA2-CM; unpaired t test; n = 6.

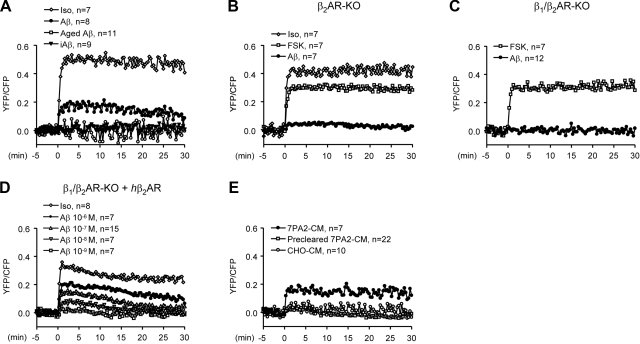

To test whether cAMP induced by activation of β2AR leads to an increase in PKA activity for protein phosphorylation, we examined PKA activity on Aβ1-42 stimulation in PFC neurons with a FRET-based PKA activity indicator, AKAR2.2 (36). In WT neurons, Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) induced a smaller increase in PKA activity than Iso did (10−7 M), followed by a gradual decrease in 30 min (Fig. 3A). In contrast, aged Aβ1-42 and sequence-inversed Aβ42-1 did not increase PKA activity (Fig. 3A). In β2AR-KO or β1/β2AR-KO neurons, Aβ1-42 did not increase PKA activity (Fig. 3B, C). Iso, which activates not only β2AR but also β1AR, induced an increase in β2AR-KO neuron (Fig. 3B), whereas forskolin (FSK; 10−5 M), an adenylyl cyclase activator, induced increases in PKA activities in both β2AR-KO and β1/β2AR-KO neurons (Fig. 3B, C). We then rescued the expression of β2AR in β1/β2AR-KO neurons with adenovirus infection. In β2AR-rescued neurons, Aβ1-42 dose-dependently increased PKA activity (Fig. 3D). In contrast, in β1/β2AR-KO cells expressing the chimeric β1NT-β2AR, Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) failed to increase PKA activity, but a subsequent Iso (10−7 M) treatment induced a significant increase (Supplemental Fig. 2D). A similar effect of Aβ1-42 on PKA activity was also observed in wild-type MEFs (Supplemental Fig. 2E). In addition, native Aβ1-42-containing 7PA2-CM also induced an increase in PKA activity; however, CHO-CM and precleared 7PA2-CM hardly had any effect (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Aβ1-42 induces a β2AR-dependent increase in PKA activities in mouse PFC neurons by FRET-based live-cell imaging. A) Changes in PKA activities in WT PFC neurons were measured before and after administration of Aβ1-42 (10−6 M), Iso (10−7 M), iAβ42-1 (10−6 M), and aged Aβ1-42 (10−6 M). B) Changes in PKA activities in β2AR-KO PFC neurons were measured before and after administration of Aβ1-42 (10−6 M), FSK (10−5 M), or Iso (10−7 M). C) Changes in PKA activities in β1/β2AR-KO PFC neurons were measured before and after administration of Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) or FSK (10−5 M). D) Changes in PKA activities in β1/β2AR-KO PFC neurons expressing flag-β2AR were measured before and after administration of Iso (10−7 M) or different doses of Aβ1-42. E) Changes in PKA activities in WT PFC neurons were measured before and after administration of 7PA2-CM, CHO-CM, or precleared 7PA2-CM.

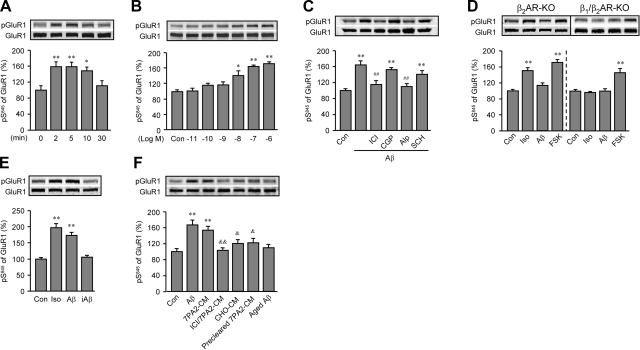

We then examined whether the Aβ1-42-induced β2AR-cAMP/PKA signaling leads to phosphorylation of downstream substrates. We chose AMPA receptor, which is a downstream target of adrenergic stimulation in the brain (25) and is involved in hyperactivities of neurons surrounding the amyloid plaques in mutant APP-transgenic mouse brain (15). Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) acutely increased PKA phosphorylation in GluR1 subunit at serine 845 (S845) but not calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation of GluR1 at serine 831 in rat PFC slices (Fig. 4A and Supplemental Fig. 3A). The Aβ1-42-increased PKA phosphorylation displayed a dose-dependent manner with a significant increase at minimal 10−8 M (Fig. 4B) and was blocked by βAR antagonist Alp (10−6 M) and β2AR antagonist ICI118551 (ICI; 10−6 M), not by β1AR antagonist CGP12177 (CGP; 10−6 M) or dopamine D1 receptor antagonist SCH (10−6 M; Fig. 4C). Aβ1-42 induced significant GluR1 phosphorylation at S845 in β1AR-KO, but not β2AR-KO or β1/β2AR-KO PFC slices, whereas positive control FSK (10−5 M) induced increases in PKA phosphorylation at S845 in all three different slices (Supplemental Fig. 3B and Fig. 4D). In comparison, Iso (10−7 M) induced increases in phosphorylation at S845 in both β1AR-KO and β2AR-KO slices, but not in β1/β2AR-KO PFC slices (Supplemental Fig. 3B and Fig. 4D). In agreement, in WT slices, the effect of Iso (10−7 M) on phosphorylation at S845 was partially blocked by CGP (10−6 M) or ICI (10−6 M, Supplemental Fig. 3C). Inverse peptide iAβ42-1 and aged Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) did not induce significant effects on phosphorylation at S845 (Fig. 4E, F). Native Aβ-containing 7PA2-CM also increased GluR1 phosphorylation at S845 (Fig. 4F), which was blocked by β2AR antagonist ICI (10−6 M), whereas CHO-CM and precleared 7PA2-CM did not (Fig. 4F). In addition, Aβ1-42 dose-dependently increased the phosphorylation of β2AR at PKA-dependent site serine 262 (S262), which was blocked by a βAR inverse agonist timolol (Tim, 10−6 M), further confirming the activation of β2AR-cAMP/PKA signaling pathway (Supplemental Fig. 4A, B). The Aβ1-42-induced and β2AR signaling-dependent phosphorylation of GluR1 is consistent with the role of adrenergic receptor-mediated PKA phosphorylation of AMPA receptor in animal behaviors under stress (25), especially in common psychiatric symptoms in AD patients (41, 42).

Figure 4.

Aβ1-42 induces a β2AR-dependent increase in the phosphorylation of GluR1 at PKA site S845 in PFC slices. A, B) A time course of Aβ1-42 (10−6 M)-induced GluR1 phosphorylation at S845 (A) and a dose-dependent response of Aβ1-42-induced GluR1 phosphorylation at S845 (B) in rat PFC slices were examined by Western blot analysis with anti-GluR1 S845 antibody. C) Changes in GluR1 phosphorylation at S845 in rat PFC slices were examined after treatment with Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) in the absence or presence of β2AR antagonist ICI (10−6 M), β1AR antagonist CGP (10−6 M), βAR antagonist Alp (10−6 M), or dopamine D1 receptor antagonist SCH (10−6 M). D) Changes in GluR1 phosphorylation at S845 in β2AR-KO or β1/β2AR-KO PFC slices were examined after treatment with Aβ1-42 (10−6 M), Iso (10−7 M), or FSK (10−5 M). E) Changes in GluR1 phosphorylation at S845 in rat PFC slices were examined after treatment with Iso (10−7 M), Aβ1-42(10−6 M), or inversed peptide iAβ42-1 (10−6 M). F) Changes in GluR1 phosphorylation at S845 in rat PFC slices were examined after treatment with 7PA2-CM, CHO-CM, precleared 7PA2-CM, or aged Aβ1-42 (10−6 M), or with 7PA2-CM in the presence of β2AR antagonist ICI (10−6 M). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control (Con.); ##P < 0.01 vs. Aβ; &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01 vs. 7PA2-CM; unpaired t test; n = 6.

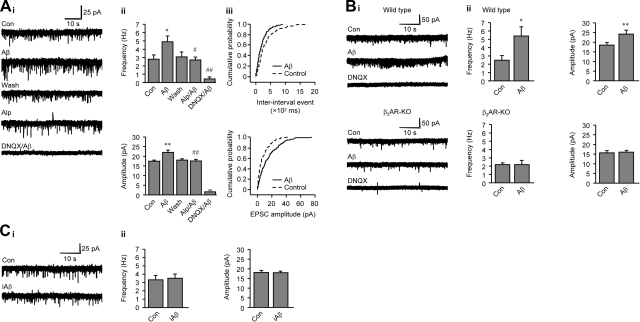

Using an in vitro slice preparation, we recorded from deep-layer PFC neurons with whole-cell recording configuration. Acute bath application of Aβ1-42 (60 s) induced an increase in mEPSC activities in rat PFC neurons (Fig. 5A). Overall, Aβ1-42 significantly increased both mEPSC frequency (84.66±8.81% over control) and amplitude (24.30±4.23% over control, Fig. 5Aii). The Aβ1-42-induced increase in mEPSC frequency, and amplitude was abolished by an AMPAR receptor antagonist DNQX, indicating that these mEPSCs are mediated by AMPA receptors (Fig. 5A). The Aβ1-42-induced increase in mEPSC activities was significantly attenuated by βAR antagonist Alp (Fig. 5Ai, ii), indicating an involvement of βARs in the action. In agreement, application of Aβ1-42 enhanced mEPSC frequency or amplitude in WT, but not in β2AR-KO neurons in mouse PFC slices (Fig. 5B). As a control, inverse peptide iAβ42-1 did not alter mEPSCs in rat PFC neurons (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Aβ1-42 induces a β2AR-dependent increase in AMPA receptor-mediated mEPSCs in PFC neurons. A) i) Representative current traces of mEPSCs from a single neuron in rat PFC slices. Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) was applied to the slices, or after pretreatment with either βAR antagonist Alp (10−6 M) or AMPA receptor antagonist DNQX (2×10−6 M). Acute effects on mEPSC activities after drug treatment (60 s) were recorded. ii) Aβ1-42-induced increases in mEPSC frequency and amplitude were plotted as bar graphs. iii) Aβ1-42-shifted cumulative probability curves for interinterval event and EPSC amplitude were plotted as curves. B) Effects of Aβ1-42 on mEPSCs in WT and β2AR-KO mouse PFC neurons. i) Representative current traces of mEPSCs were recorded in WT and β2AR-KO neurons. ii). Aβ1-42-induced increases in mEPSC frequency and amplitude were plotted as bar graphs. C) Effects of iAβ42-1 on mEPSCs in rat PFC neurons. i) Representative current traces of mEPSCs were recorded in rat PFC neurons. ii). iAβ1-42-induced changes in mEPSC frequency and amplitude were plotted as bar graphs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. Con.; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. Aβ; paired t test; n = 6–7. Each treatment was applied in sequence, with washing in between. Con, basal mEPSC activity.

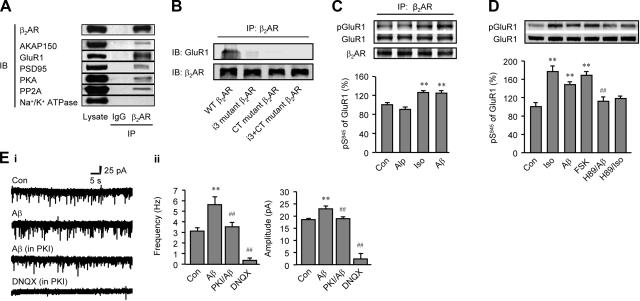

To further understand the cellular mechanism underlying the Aβ1-42-induced and β2AR signaling-dependent phosphorylation of GluR1 for mEPSCs, we characterized the potential association of β2AR with GluR1 in rat PFC. GluR1 was coimmunoprecipitated with β2AR in rat PFC homogenates (Fig. 6A), β2AR is also coprecipitated with PKA, AKAP150 (a protein anchoring PKA holoenzyme to discrete locations in neurons), PP2A (a ubiquitously expressed serine/threonine phosphatase), and PSD95 (a specialized scaffold protein with multiple protein interaction domains that forms the backbone of organized and extensive postsynaptic protein complexes at synaptic contact zone), but not with the membrane protein Na+/K+-ATPase (Fig. 6A). Further analysis using chimeric β2ARs with their i3 loop and/or C terminus replaced by those of β1AR showed that both the i3 and C terminus of β2AR were required for formation of β2AR-GluR1 complex (Fig. 6B). The association between GluR1 and β2AR was not altered in slices treated with either Iso (10−7 M) or Aβ1-42 (10−6 M); however, the levels of PKA-dependent phosphorylation of GluR1 in the complexes were significantly higher than controls treated with either vehicle or βAR antagonist Alp (10−6 M, Fig. 6C). These data support that a β2AR/AMPA receptor complex can be activated by Aβ1-42 through β2AR-cAMP/PKA signaling. Indeed, GluR1 phosphorylation at S845 induced by Aβ1-42 and Iso was blocked by a PKA inhibitor, H89 (10−6 M) (Fig. 6D). Moreover, inhibition of PKA with PKI (10−6 M) administered through the recording electrode abolished Aβ1-42-enhanced AMPA receptor channel activity (Fig. 6E), further supporting the PKA-dependent mechanism for Aβ1-42.

Figure 6.

A GluR1/β2AR complex conducts the PKA-dependent increases in the AMPA receptor-mediated mEPSCs. A) Rat PFC lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the antibody against β2AR. Bound proteins were detected by Western blotting. B) Chimeric flag-β2ARs were coexpressed with GluR1 in β1/β2AR-KO MEF cells, and cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the antibody against flag. Bound GluR1 and β2ARs were detected using Western blot analysis. C) Rat PFC slices were treated with Alp (10−6 M), Iso (10−7 M), or Aβ1-42 (10−6 M). Slices were lysed for immunoprecipitation with the antibody against β2AR. Bound proteins were detected by Western blot analysis. D) Changes in GluR1 phosphorylation at S845 in rat PFC slices were examined after treatment with Iso (10−7 M) or Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) in the absence or presence of PKA inhibitor H89 (10−6 M), or after treatment with FSK (10−5 M). E) Actions of Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) on AMPA receptor-mediated mEPSCs was dependent on PKA activity in rat PFC slices. i) Representative current traces of mEPSCs were recorded in rat PFC neurons. ii) mEPSC frequency and amplitude after Aβ1-42 (10−6 M) in the absence and presence of PKI (10−6 M) were plotted as bar graphs. **P < 0.01 vs. Con.; ##P < 0.01 vs. Aβ; unpaired t test (C, D) or paired t test (E); n = 6. Con, basal mEPSC activity.

DISCUSSION

β2AR is a representative family-A GPCR. Many of the family members bind to both small molecules and peptide ligands at various sites (43). In the present study, β2AR shows a binding ability to Aβ1-42. Replacement of the N terminus of β2AR with that of β1AR greatly decreases its binding to Aβ1-42 and abolished the Aβ1-42-induced cAMP and PKA activities, indicating that the N terminus of β2AR is required for the Aβ1-42 binding; and different strategies are used by the peptide and small molecular ligands in binding to the receptor. Interestingly, although monomer is more abundant than dimer in the Aβ1-42 solution, β2AR are mostly coimunoprecipitated with Aβ1-42 dimer. Our data thus indicate a potential link between β2AR-mediated adrenergic signaling-related broad consequences and potent effects of native Aβ1-42 in vivo (40). The detailed structural and biophysical binding properties of the peptide to β2AR are worth being addressed in the future. Beause Aβ is not a neurotransmitter like norepinephrine that is released from presynapses in a timely controllable way, the overactivation of AMPA receptors correlated with Aβ should be distinct from normal adrenergic-modulated neurotransmission in the brain.

cAMP accumulation, real-time PKA activity, and receptor phosphorylation studies reveal an Aβ1-42-induced signaling pathway from β2AR binding to GluR1 phosphorylation. Aβ1-42 increases GluR1 phosphorylation at S845 by initiating cAMP-PKA signaling pathway via β2AR. The Aβ1-42-induced rapid enhancement in AMPA receptor activity could be, in part, explained by formation of a complex between GluR1 and β2AR, in which both the i3 loop and the C terminus of β2AR are required for the association. This complex is also characterized recently by an independent study during the revision of the present report showing that the complex formation is dependent on binding of both GluR1 and β2AR to PSD95 at postsynapses (44). Both studies further extend the earlier characterization of a complex between GluR1, AKAP150, PSD95, PKA, and PP2B (45, 46), and a β2AR-AKAP-PKA complex (47), supporting the idea that cAMP/PKA signaling is finely regulated in postsynaptic complex (48). While Aβ treatment does not affect the association between β2AR and GluR1, the PKA phosphorylation of GluR1 in the complex is greatly enhanced by Aβ treatment (Fig. 6C), consistent with the observation that depletion of β2AR reduces the iso-induced PKA phosphorylation of GluR1 (44). Moreover, administration of a peptide PKI through recording electrode to inhibit PKA activity abolishes the Aβ1-42-induced response in AMPA receptor activity, consistent with that PKA phosphorylation of GluR1 at S845 increases AMPA receptor opening probability (43). Although a presynaptic effect on PKA-related release of neurotransmitters under Aβ1-42 administration can contribute to the observed AMPA receptor activities (49), the present biochemical studies support that there is a postsynaptic effect of Aβ1-42 on AMPA receptor via a direct β2AR-PKA-dependent phosphorylation in a postsynaptic β2AR/GluR1 complex (Figs. 3, 4 and 6, and ref. 43).

It has been reported that the oligomeric states of Aβ peptides and treating time differentially affect synaptic function (6, 7, 9,10,11). In this study, we have revealed a cellular receptor-signaling mechanism that may help understand the acute and chronic effects on synaptic function induced by Aβ. Our data show that Aβ acutely increases spontaneous synaptic activity and intrinsic excitability mediated by AMPA receptor in neurons within 1 min (Fig. 5) (9, 10). However, a chronic Aβ-induced and β2AR-mediated increase in AMPA receptor activity may contribute to excessive calcium influx-induced excitatory neurotoxicity (15, 50), which may lead to hyperactivity of neurons near Aβ plaques (15) and dendrtic spine loss, as well as impaired memory and learning (6). A long-term treatment with soluble Aβ can also inhibit synaptic transmission and reduces LTP (5, 6, 40) via secondary mechanisms such as down-regulation of AMPA receptor and β2AR (ref. 3 and unpublished results). The present study underlines a potential link between the Aβ/β2AR signaling axis and pathological effects induced by Aβ1-42, such as increased incidences of epileptic seizure (51) and other stress-related symptoms in AD, including agitation/aggression, irritability, and anxiety (52, 53). Beyond AD, high levels of amyloid peptide are also seen in children with Down syndrome and in Parkinson disease (54, 55). Therefore, the interaction between Aβ and brain adrenergic system could be part of general mechanisms for neurodegenerative diseases.

Interestingly, stimulation of β2AR also increases the γ-secretase-dependent process of amyloid precursor protein to yield Aβ in neurons (56). Thus, Aβ may potentially promote the process of amyloid precursor protein via binding to and activating β2AR, through which amyloid peptide and the adrenergic system act as a self-promoting cycle to facilitate the Aβ deposition. Indeed, inhibition of β2AR with ICI115881 significantly reduces the formation of amyloid plaques in AD animals (56). Moreover, recent clinical studies shows that use of β-blockers is associated with a delayed rate of functional decline (20), and a decreased incidence of AD pathogenesis (19).

The present findings support the emerging concept that the effects of soluble Aβ in AD initially center on subtly altered synapse function. GPCRs have emerged as essential regulators in AD pathogenesis. Besides the adrenergic system, both cholinergic and angiotensin systems have been implicated in development of AD (57,58,59). Considering broad downstream cellular targets of PKA, including AMPA receptor, L-type calcium channel, and tau (60), the CNS adrenergic signaling pathways activated by Aβ may present as a critical link between amyloid peptide and a wide array of effects on synapses, as well as tissue and whole animals. Further studies on in vivo function of Aβ-β2AR signaling module will extend our understanding of the role of Aβ, as well as β2AR in the etiopathology of AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Dennis J. Selkoe (Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA, USA) for kindly providing the 7PA2-transgenic CHO cell line and the plasmid, and Dr. Richard Clark (University of Texas Medical Center, Houston, TX, USA) for anti-β2AR S261/262 antibody. The authors thank Dr. Venkata R. P. Ratnala (Departments of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA) for performing the [35S]GTPγS binding assay. The authors thank Mr. Mingwei Ding, Branden Skarpiak, Elaine Wu, and other members of the Y.K.X. laboratory for assistance. This work was supported by National Eye Institute grant EY014024 (C.L.C.) and National Institute of Heart, Blood, and Lung grant HL082846 (Y.K.X.). D.W. is a recipient of a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression award and an Illinois Department of Public Health grant.

References

- Davies C A, Mann D M, Sumpter P Q, Yates P O. A quantitative morphometric analysis of the neuronal and synaptic content of the frontal and temporal cortex in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 1987;78:151–164. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(87)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe D J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Boehm J, Sato C, Iwatsubo T, Tomita T, Sisodia S, Malinow R. AMPAR removal underlies Aβ-induced synaptic depression and dendritic spine loss. Neuron. 2006;52:831–843. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen J S, Wu C C, Redwine J M, Comery T A, Arias R, Bowlby M, Martone R, Morrison J H, Pangalos M N, Reinhart P H, Bloom F E. Early-onset behavioral and synaptic deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5161–5166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600948103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar G M, Bloodgood B L, Townsend M, Walsh D M, Selkoe D J, Sabatini B L. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2866–2875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar G M, Li S, Mehta T H, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson N E, Smith I, Brett F M, Farrell M A, Rowan M J, Lemere C A, Regan C M, Walsh D M, Sabatini B L, Selkoe D J. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenetz F, Tomita T, Hsieh H, Seabrook G, Borchelt D, Iwatsubo T, Sisodia S, Malinow R. APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron. 2003;37:925–937. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Koh M T, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe C G, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe K H. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley D M, Walsh D M, Ye C P, Diehl T, Vasquez S, Vassilev P M, Teplow D B, Selkoe D J. Protofibrillar intermediates of amyloid beta-protein induce acute electrophysiological changes and progressive neurotoxicity in cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8876–8884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08876.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye C, Walsh D M, Selkoe D J, Hartley D M. Amyloid beta-protein induced electrophysiological changes are dependent on aggregation state: N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) versus non-NMDA receptor/channel activation. Neurosci Lett. 2004;366:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmrich V, Grimm C, Draguhn A, Barghorn S, Lehmann A, Schoemaker H, Hillen H, Gross G, Ebert U, Bruehl C. Amyloid beta oligomers (A beta(1-42) globulomer) suppress spontaneous synaptic activity by inhibition of P/Q-type calcium currents. J Neurosci. 2008;28:788–797. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4771-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard B J, Chen A, Rozeboom L M, Stafford K A, Weigele P, Ingram V M. Efficient reversal of Alzheimer’s disease fibril formation and elimination of neurotoxicity by a small molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14326–14332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405941101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louzada P R, Jr, Paula Lima A C, de Mello F G, Ferreira S T. Dual role of glutamatergic neurotransmission on amyloid beta(1-42) aggregation and neurotoxicity in embryonic avian retina. Neurosci Lett. 2001;301:59–63. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01585-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parameshwaran K, Dhanasekaran M, Suppiramaniam V. Amyloid beta peptides and glutamatergic synaptic dysregulation. Exp Neurol. 2008;210:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busche M A, Eichhoff G, Adelsberger H, Abramowski D, Wiederhold K H, Haass C, Staufenbiel M, Konnerth A, Garaschuk O. Clusters of hyperactive neurons near amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2008;321:1686–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.1162844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carulla N, Caddy G L, Hall D R, Zurdo J, Gairi M, Feliz M, Giralt E, Robinson C V, Dobson C M. Molecular recycling within amyloid fibrils. Nature. 2005;436:554–558. doi: 10.1038/nature03986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubig R R, Siderovski D P. Regulators of G-protein signalling as new central nervous system drug targets. Nat Rev. 2002;1:187–197. doi: 10.1038/nrd747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainetdinov R R, Premont R T, Bohn L M, Lefkowitz R J, Caron M G. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors and neuronal functions. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:107–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J T, Tan L, Ou J R, Zhu J X, Liu K, Song J H, Sun Y P. Polymorphisms at the β2-adrenergic receptor gene influence Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility. Brain Res. 2008;1210:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg P B, Mielke M M, Tschanz J, Cook L, Corcoran C, Hayden K M, Norton M, Rabins P V, Green R C, Welsh-Bohmer K A, Breitner J C, Munger R, Lyketsos C G. Effects of cardiovascular medications on rate of functional decline in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2008;16:883–892. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318181276a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria V, Ducatenzeiler A, Chen C H, Cuello A C. Endogenous β-amyloid peptide synthesis modulates cAMP response element-regulated gene expression in PC12 cells. Neuroscience. 2005;135:1193–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igbavboa U, Johnson-Anuna L N, Rossello X, Butterick T A, Sun G Y, Wood W G. Amyloid β-protein1-42 increases cAMP and apolipoprotein E levels which are inhibited by β1 and β2-adrenergic receptor antagonists in mouse primary astrocytes. Neuroscience. 2006;142:655–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima-Ando K, Hearn S A, Granger L, Shenton C, Gatt A, Chiang H C, Hakker I, Zhong Y, Iijima K. Overexpression of neprilysin reduces alzheimer amyloid-β42 (Aβ42)-induced neuron loss and intraneuronal Aβ42 deposits but causes a reduction in cAMP-responsive element-binding protein-mediated transcription, age-dependent axon pathology, and premature death in Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19066–19076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710509200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D A, Akamine P, Radzio-Andzelm E, Madhusudan M, Taylor S S. Dynamics of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2243–2270. doi: 10.1021/cr000226k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Real E, Takamiya K, Kang M G, Ledoux J, Huganir R L, Malinow R. Emotion enhances learning via norepinephrine regulation of AMPA-receptor trafficking. Cell. 2007;131:160–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banke T G, Bowie D, Lee H, Huganir R L, Schousboe A, Traynelis S F. Control of GluR1 AMPA receptor function by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Neurosci. 2000;20:89–102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00089.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornischka J, Cordes J, Agelink M W. [40 years beta-adrenoceptor blockers in psychiatry] Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2007;75:199–210. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vekovischeva O Y, Aitta-aho T, Verbitskaya E, Sandnabba K, Korpi E R. Acute effects of AMPA-type glutamate receptor antagonists on intermale social behavior in two mouse lines bidirectionally selected for offensive aggression. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;87:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Naro F, Zoudilova M, Jin S L, Conti M, Kobilka B. Phosphodiesterase 4D is required for β2 adrenoceptor subtype-specific signaling in cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:909–914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405263102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C J, Liao S L. Zinc toxicity on neonatal cortical neurons: involvement of glutathione chelation. J Neurochem. 2003;85:443–453. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong L, Thornton P L, Balazs R, Cotman C W. Beta-amyloid-(1-42) impairs activity-dependent cAMP-response element-binding protein signaling in neurons at concentrations in which cell survival is not compromised. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17301–17306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010450200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Noda Y, Zhou Y, Mouri A, Mizoguchi H, Nitta A, Chen W, Nabeshima T. The allosteric potentiation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by galantamine ameliorates the cognitive dysfunction in beta amyloid 25–35 i.c.v.-injected mice: involvement of dopaminergic systems. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1261–1271. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, De Arcangelis V, Gao X, Ramani B, Jung Y S, Xiang Y. Norepinephrine- and epinephrine-induced distinct β2-adrenoceptor signaling is dictated by GRK2 phosphorylation in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1799–1807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Lauffer B, Von Zastrow M, Kobilka B K, Xiang Y. N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor regulates beta2 adrenoceptor trafficking and signaling in cardiomyocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:429–439. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.037747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminath G, Xiang Y, Lee T W, Steenhuis J, Parnot C, Kobilka B K. Sequential binding of agonists to the β2 adrenoceptor. Kinetic evidence for intermediate conformational states. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:686–691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Hupfeld C J, Taylor S S, Olefsky J M, Tsien R Y. Insulin disrupts β-adrenergic signalling to protein kinase A in adipocytes. Nature. 2005;437:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature04140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Ramani B, Soto D, De Arcangelis V, Xiang Y. Agonist dose-dependent phosphorylation by protein kinase A and G protein-coupled receptor kinase regulates β2 adrenoceptor coupling to G(i) proteins in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32279–32287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindaiah G, Cox C L. Metabotropic glutamate receptors differentially regulate GABAergic inhibition in thalamus. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13443–13453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3578-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whorton M R, Bokoch M P, Rasmussen S G, Huang B, Zare R N, Kobilka B, Sunahara R K. A monomeric G protein-coupled receptor isolated in a high-density lipoprotein particle efficiently activates its G protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7682–7687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611448104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D M, Klyubin I, Fadeeva J V, Cullen W K, Anwyl R, Wolfe M S, Rowan M J, Selkoe D J. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendijk W J, Feenstra M G, Botterblom M H, Gilhuis J, Sommer I E, Kamphorst W, Eikelenboom P, Swaab D F. Increased activity of surviving locus ceruleus neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:82–91. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199901)45:1<82::aid-art14>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendijk W J, Meynen G, Feenstra M G, Eikelenboom P, Kamphorst W, Swaab D F. [Increased activity of stress-regulating systems in Alzheimer disease] Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 2001;32:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gether U. Uncovering molecular mechanisms involved in activation of G protein-coupled receptors. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:90–113. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner M L, Lise M F, Yuen E Y, Kam A Y, Zhang M, Hall D D, Malik Z A, Qian H, Chen Y, Ulrich J D, Burette A C, Weinberg R J, Law P Y, El-Husseini A, Yan Z, Hell J W. Assembly of a beta(2)-adrenergic receptor-GluR1 signalling complex for localized cAMP signalling. EMBO J. 2009;29:482–495. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge M, Dean R A, Scott G K, Langeberg L K, Huganir R L, Scott J D. Targeting of PKA to glutamate receptors through a MAGUK-AKAP complex. Neuron. 2000;27:107–119. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavalin S J, Colledge M, Hell J W, Langeberg L K, Huganir R L, Scott J D. Regulation of GluR1 by the A-kinase anchoring protein 79 (AKAP79) signaling complex shares properties with long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3044–3051. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03044.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J, Wang H Y, Malbon C C. Protein kinase A regulates AKAP250 (gravin) scaffold binding to the β2-adrenergic receptor. EMBO J. 2003;22:6419–6429. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beene D L, Scott J D. A-kinase anchoring proteins take shape. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramov E, Dolev I, Fogel H, Ciccotosto G D, Ruff E, Slutsky I. Amyloid-beta as a positive endogenous regulator of release probability at hippocampal synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1567–1576. doi: 10.1038/nn.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchibhotla K V, Goldman S T, Lattarulo C R, Wu H Y, Hyman B T, Bacskai B J. Abeta plaques lead to aberrant regulation of calcium homeostasis in vivo resulting in structural and functional disruption of neuronal networks. Neuron. 2008;59:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatniek J C, Hauser W A, DelCastillo-Castaneda C, Jacobs D M, Marder K, Bell K, Albert M, Brandt J, Stern Y. Incidence and predictors of seizures in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Epilepsia. 2006;47:867–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis P T. Altered glutamate neurotransmission and behaviour in dementia: evidence from studies of memantine. Curr Molec Pharmacol. 2009;2:77–82. doi: 10.2174/1874467210902010077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo-Neustadt A, Cotman C W. Adrenergic receptors in Alzheimer’s disease brain: selective increases in the cerebella of aggressive patients. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5573–5580. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05573.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund H, Anneren G, Gustafsson J, Wester U, Wiltfang J, Lannfelt L, Blennow K, Hoglund K. Increase in β-amyloid levels in cerebrospinal fluid of children with Down syndrome. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:369–374. doi: 10.1159/000109215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo G, Schluter O M, Sudhof T C. A molecular pathway of neurodegeneration linking alpha-synuclein to ApoE and Abeta peptides. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:301–308. doi: 10.1038/nn2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y, Zhao X, Bao G, Zou L, Teng L, Wang Z, Song M, Xiong J, Bai Y, Pei G. Activation of β2-adrenergic receptor stimulates gamma-secretase activity and accelerates amyloid plaque formation. Nat Med. 2006;12:1390–1396. doi: 10.1038/nm1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit D L, Shao Z, Yakel J L. β-amyloid(1-42) peptide directly modulates nicotinic receptors in the rat hippocampal slice. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC120. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh Y, Hirakura Y, Shibayama S, Hirashima N, Suzuki T, Kirino Y. β-amyloid peptides inhibit acetylcholine release from cholinergic presynaptic nerve endings isolated from an electric ray. Neurosci Lett. 2001;302:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AbdAlla S, Lother H, el Missiry A, Langer A, Sergeev P, el Faramawy Y, Quitterer U. Angiotensin II AT2 receptor oligomers mediate G-protein dysfunction in an animal model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6554–6565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807746200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davare M A, Avdonin V, Hall D D, Peden E M, Burette A, Weinberg R J, Horne M C, Hoshi T, Hell J W. A β2 adrenergic receptor signaling complex assembled with the Ca2+ channel Cav1.2. Science. 2001;293:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5527.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.