Abstract

We describe two reagentless methods of silver deposition for metal-enhanced fluorescence. Silver was deposited on glass positioned between two silver electrodes with a constant current in pure water. Illumination of the glass between the electrodes resulted in localized silver deposition. Alternatively, silver was deposited on an Indium Tin Oxide cathode, with a silver electrode as the anode. Both types of deposited silver produced a 5–18-fold increase in the fluorescence intensity of a nearby fluorophore, indocyanine green (ICG). Additionally, the photostability of ICG was dramatically increased by proximity to the deposited silver. These results suggest the use of silver deposited from pure water for surface-enhanced fluorescence, with potential applications in surface assays and lab-on-a-chip-based technologies, which ideally require highly fluorescent photostable systems.

Introduction

At present, there is great interest in developing the use of noble metals, particles, and surfaces for applications in sensing, biotechnology, and nanotechnology.1–4 This interest has its origins in the pioneering studies of Drexhage on the effects of mirrors on nearby fluorophores5,6 and subsequent studies by Barnes and co-workers.7–9 In this laboratory, we have studied the favorable effects of silver particles on fluorophores. These effects include increased quantum yields, decreased lifetimes, and increased photostability of fluorophores commonly used in biological research.10–12 These effects of conducting metallic particles on fluorescence have been the subject of numerous theoretical studies related to surface-enhanced Raman scattering13,14 and the application of these considerations to molecular fluorescence.15–18 There is now interest in using the remarkable properties of metallic colloids. Consequently, it is of interest to develop convenient methods for forming particles and depositing particles on surfaces. These approaches include electroless deposition,19 electroplating on insulators,20 lithography,21,22 and the formation of colloids under constant reagent flow.23 Metallic particles can be assembled into films using electrophoresis,24 and gold particles have been used for the on-demand electrochemical release of DNA.25 It is anticipated that many of these approaches will find uses in medical diagnostics and lab-on-a-chip-type applications.26–29

In our recent studies of metal-enhanced fluorescence,10–12 we deposited silver onto glass surfaces by the chemical reduction of silver nitrate, as was described by Ni and Cotton.30 However, it seemed biologically valuable to devise methods for localized silver deposition without harsh reagents. Knowing the long history of silver in photography31,32 and the formation of silver particles by light,33,34 we examined the possibility that silver particles could be deposited on illuminated glass surfaces from pure water between two silver electrodes. We additionally found that silver particles can be readily deposited on Indium Tin Oxide (ITO), a very useful and almost visually transparent semiconductor substrate. These methods of silver deposition can be readily applied to diagnostic or sensing devices, applications of metal-enhanced fluorescence.

Experimental Section

Indocyanine green (ICG) and human serum albumin (HSA) were obtained from Sigma and used without further purification. Concentrations of ICG and HSA were determined using extinction coefficients of ε(780 nm) = 130 000 cm−1 and ε(278 nm) = 37 000 cm−1, respectively. ITO-coated glass slides were purchased from Delta Technologies, Ltd., U.S.A.

The glass slides were cleaned before use by immersion in 30% (v/v) H2O2 and 70% (v/v) H2SO4 for 48 h and then washed in distilled water. The ITO surfaces were used as received. The binding of ICG-HSA to the surfaces, whether glass, silver, or ITO, was accomplished by soaking the desired surface in a 30 μM ICG, 60 μM HSA solution overnight, followed by rinsing with water to remove the unbound material.

For photostability experiments, fluorescence lifetimes, and steady-state emission measurements on silver/glass and ITO, the surfaces were examined in a sandwich configuration in which two coated surfaces faced inward toward an approximate 1-μm-thick aqueous sample. The slides were only half coated with silver, the other half of the substrate providing a reference (the control sample) from which we could readily determine the fluorescence enhancement ratio.

Methods

Excitation and observation of the sandwiched samples were made by the front-face configuration (Figure 1). Steady-state emission spectra were recorded using a SLM 8000 spectrofluorometer with excitation using a Spectra Physics Tsunami Ti:sapphire laser in the CW (nonpulsed) mode, which was attenuated as was required: ≈200-mW, 760-nm output. This enabled the samples to be photobleached as was required, that is, for matching the initial steady-state intensities or using the same excitation power (see results section).

Figure 1.

Experimental geometry for fluorescence measurements.

Time-resolved intensity decays were measured using reverse start–stop time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC), using a SPC630 Becker and Hickl GmbH PC card and a microchannel plate PMT (not externally amplified). The PC card features all the necessary commonly used NIM modules for TCSPC, including input discrimination for the optical trigger pulse (red-sensitive Avalanche Photodiode) as well as a high time resolution, up to 813 fs/ch. In addition to the PC card, an EG & G Ortec external NIM delay unit was used. Vertically polarized excitation at ≈760 nm was obtained using a mode-locked argon ion-pumped, cavity-dumped pyridine 2 dye laser with a 3.77-MHz repetition rate. The instrumental response function, determined using the experimental geometry in Figure 1, for silver films/spots and glass slides, was typically <50 ps full width at half-maximum. The emission was collected at the magic angle (54.70), using a long pass filter (Edmund Scientific), which cut off wavelengths below 780 nm, with an additional 830 ± 10 nm interference filter. Carefully undertaken control experiments with silvered surfaces without ICG-HSA showed that all the scattered light was alleviated by the filter combination, which was an important consideration given the high scattering cross section of the metal colloids.35–37

Data Analysis

The intensity decays were analyzed in terms of the multiexponential model:

| (1) |

where αi are the amplitudes and τi the decay times and Σαi = 1.0. The fractional contribution of each component to the steady-state intensity is given by

| (2) |

The mean lifetime of the excited state is given by

| (3) |

and the amplitude-weighted lifetime is given by

| (4) |

The values of αi and τi were determined by nonlinear least squares impulse reconvolution with a goodness-of-fit χ2 criterion.

Results

Our first method of silver deposition was to pass a controlled current between two electrodes in pure water (Figure 2, top). The two silver electrodes were mounted in a quartz cuvette containing deionized (Millipore) water. The silver electrodes had dimensions of 9 × 35 × 0.1 mm separated by a distance of 10 mm. For the production of silver colloids, a simple constant current generator circuit (60 μA) was constructed and used.

Figure 2.

(Top) Preparation of laser-deposited silver on a glass slide from electrolysis-produced silver colloids. (Bottom) Electrochemical deposition of Ag on an ITO surface.

After 30 min of current flow, a clear glass microscope slide was positioned within the cuvette (no chemical glass-surface modifications) and was illuminated (HeCd, 442 nm). We observed silver deposition on the glass microscope slide, the amount depending on the illumination time. Simultaneous electrolysis and 442-nm laser illumination resulted in the deposition of metallic silver in the targeted illuminated region, ≈5-mm-focused spot size (Figure 2, top).

Our second method was similar to the first, except that the silver cathode electrode was replaced with an ITO-coated glass electrode. The current was again 60 μA. After a short period of time, silver readily deposited on the ITO surface (no laser illumination), the extent of which was again dependent on the exposure time.

Silver particles are known to display a characteristic surface plasmon absorption, which depends on their sizes and shapes.38 Absorption spectra of the deposited silver are shown in Figure 3. A single absorption band is present on glass, and two maxima were found on ITO, which eventually formed one large broad band. This suggests that the particles are roughly spherical on glass, and on ITO, the particles are elongated and display both transverse and longitudinal resonances (Figure 3, bottom).39

Figure 3.

(Top) Absorption spectrum of laser-deposited, electrochemically produced silver and (bottom) absorption spectrum of silver-coated ITO produced via electrochemical deposition. ITO without silver was in the reference beam.

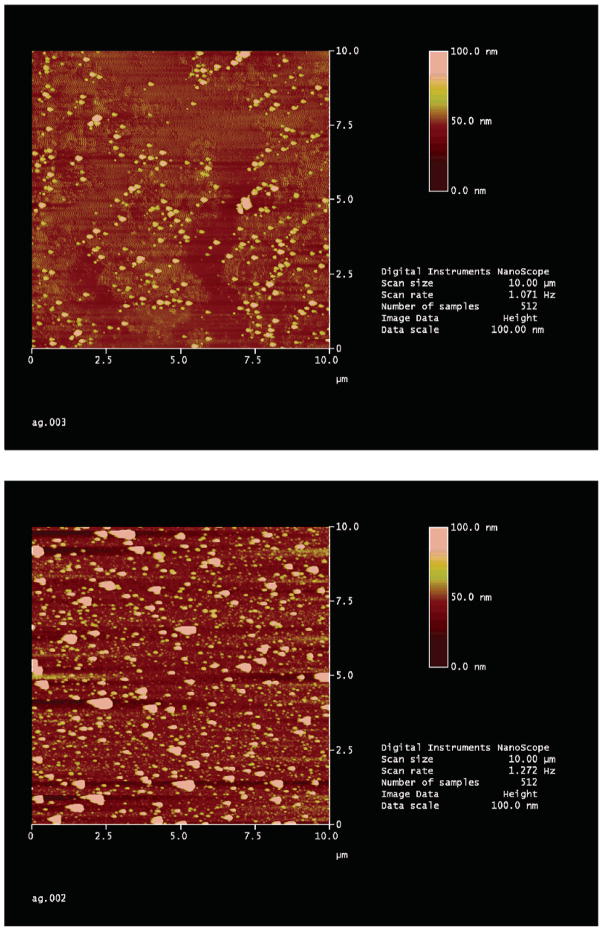

The silvered surfaces were examined using atomic force microscopy (AFM). The AFM images of silver on glass typically showed a modest coverage of silver (Figure 4). The AFM images of silvered ITO showed more elongated particles, as was also observed from the absorption spectra (Figure 3). Interestingly, the silver particles on ITO are typically much larger than those on glass, on the order of 100 nm as compared to ≈50–100 nm on glass.

Figure 4.

(Top) AFM image of the laser-deposited silver surface and (bottom) AFM image of the silver-coated ITO surface produced via electrolysis.

We tested the ability of silver deposited from pure water and two silver electrodes by 442-nm laser light to enhance the fluorescence of nearby fluorophores. For this purpose, we chose the long-wavelength dye ICG, which is widely used in a variety of in vivo medical applications.40,41 ICG displays a low quantum yield in solution and a somewhat higher quantum yield when bound to serum albumin, ICG-HSA.42–44 Albumin adsorbs to surfaces to form a monolayer,45,46 and ICG spontaneously binds to albumin. ICG is chemically and photochemically unstable and, thus, provided us with an ideal opportunity to test silver particles in terms of both metal-enhanced ICG emission and increased ICG photochemical stability.

We examined ICG-HSA when coated on glass (G) or silver particles (S). The emission intensity was increased about 18-fold on the silver particles (Figure 5, top) with the enhancement varying slightly for different portions of the slide. The emission spectrum did not shift (lower). Enhanced fluorescence emission from ICG-HSA was also found for silver particles on ITO (Figure 5, bottom), but the enhancement was typically less and there appeared to be a small blue shift on silvered ITO also (lower). We note that we have not varied the deposition conditions for our two methods so that it is not known which method will ultimately yield the greatest enhancements.

Figure 5.

(Top) Fluorescence intensity of HSA-ICG-coated glass, G, and, above, laser-deposited silver produced by electrolysis, S: excitation = 760 nm, emission = 810 ± 10 nm. (Bottom) Fluorescence intensity of HSA-ICG-coated ITO, IITO, and, above, electrochemically deposited silver-coated ITO, IITO/silver: excitation = 760 nm, emission = 810 ± 10 nm.

Fluorescent probes frequently display increases in intensity or quantum yield (Q0) when bound in a rigid environment. The increased intensity is usually due to a decrease in the fluorescence competitive nonradiative decay rates, knr. This means that the lifetime (τ0) also increases as the quantum yield increases, as is shown in eqs 5 and 6.

| (5) |

| (6) |

In these equations, Γ is the radiative decay rate. Contrasting behaviors are expected near metallic particles, which can increase the radiative rate by a factor γ, yielding increased quantum yields (Qm) and a decreased lifetime (τm).

| (7) |

| (8) |

For simplicity, we have not included other possible effects of metals on nearby fluorophores, which include increased rates of excitation and quenching at short distances. In most fluorescence experiments, the radiative decay rate is not significantly changed by the local environment. This rate is determined by the transition probability or, equivalently, the extinction coefficient.47 However, this canceling of the radiative rate is due to the nearby constant photonic mode density around the fluorophore equal to the free space value. In contrast, metallic surfaces and particles can change the local photonic mode density and, thus, the radiative decay rate.8

To distinguish between increases in knr or increases in Γm, we examined the intensity decays of ICG-HSA (Figure 6). The intensity decay is more rapid on glass than that in solution (cf. curves C and G). This effect has been observed previously and is probably due to the higher refractive index of the glass and the modest dependence of Γ on the refractive index.47,48 Importantly, there is a dramatic decrease in the decay time when ICG-HSA is positioned near silver particles on glass (Figure 6 and Table 1). For ICG-HSA on silver/ITO, the lifetimes are similar to that on glass; the lifetime on silver/ITO did not increase, but the intensity increased approximately fivefold. These results suggest that the increased intensities seen in Figure 5 are due to increases in the radiative decay rate, Γ, due to the silver particles, cf. eqs 7 and 8. In all our experiments, scattered light was rejected. We have recently termed this relativity new phenomenon both “Radiative Decay Engineering”10 and “Metal-Enhanced Fluorescence”.49

Figure 6.

Complex intensity decays of ICG-HSA in a cuvette (buffer), C, on glass slides, G, on silver coated ITO, ITO, and on a silver spot, S. RF is the instrumental response function.

Table 1.

Analysis of the Intensity Decay of ICG-HSA Measured Using the Reverse Start–Stop TCSPC Technique and the Multiexponential Model

| sample | αi | τI (ns) | fi | τ̄ (ns) | 〈τ〉(ns) | χR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in buffer | 0.158 | 0.190 | 0.05 | |||

| 0.842 | 0.615 | 0.95 | 0.592 | 0.548 | 1.4 | |

| on quartz | 0.683 | 0.155 | 0.325 | |||

| 0.317 | 0.691 | 0.675 | 0.517 | 0.325 | 1.3 | |

| on LDa silver | 0.814 | 0.085 | 0.440 | |||

| 0.186 | 0.474 | 0.560 | 0.303 | 0.157 | 2.7 | |

| on ITO | 0.624 | 0.128 | 0.273 | |||

| 0.376 | 0.565 | 0.727 | 0.446 | 0.292 | 3.8 |

Laser-deposited.

Decreases in lifetime are expected to result in an increased photostability because there is less time for reactions in the excited state.10 We examined the photostability of ICG-HSA when near silver particles on glass. The photostability of silvered-ITO surfaces was not studied. We found a dramatic increase in the photostability near the silver particles (Figure 7). This very encouraging result indicates that a much higher signal can be obtained from each fluorophore prior to photodestruction and that more photons can be obtained per fluorophore before the ICG on silver eventually degrades. Our photostability data presented here are very encouraging and suggest the use of metal-enhanced fluorescence in fluorescence surface assays and lab-on-a-chip-type technologies, which are inherently prone to fluorophore instability and an inadequate fluorescence signal intensity.

Figure 7.

(Top) Photostability of ICG-HSA on glass and laser-deposited silver produced via electrolysis, measured using the same excitation power at 760 nm and (bottom) with power adjusted to give the same initial fluorescence intensities. In all the measurements, vertically polarized excitation was used, while the fluorescence emission was observed at the magic angle, that is, 54.7°. Photostability on the silvered-ITO surface is not shown.

Conclusion

Silver particles can be easily generated in pure water using silver electrodes. These particles can be localized on surfaces using laser illumination or by an electric field. The deposited silver particles enhance the fluorescence emission intensity and photostability of nearby fluorophores. These methods can be used in devices fabricated for medical diagnostics or analytical sensing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, NIH EB 00682 and EB 00981, and the National Center for Research Resources, RR-08119.

References

- 1.Schalkhammer T, Aussenegg FR, Leitner A, Brunner H, Hawa G, Lobmaier C, Pittner F. SPIE. 1997;2976:1290. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labmaier Ch, Hawa G, Gotzinger M, Wirth M, Pittner F, Gabor F. J Mol Recognit. 2001;14:215. doi: 10.1002/jmr.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taton TA, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL. Science. 2000;289:1757. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J, Jiang M, Mukherjee B. Bioelectrochem Bioenerg. 2000;52:111. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drexhage KH. Interaction of light with monomolecular dye lasers. In: Wolfe E, editor. Progress in Optics. North-Holland; Amsterdam: 1974. p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drexhage KH. J Lumin. 1970;1–2:693. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amos RM, Barnes WL. Phys Rev B. 1997;55(11):7249. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes WL. J Mod Opt. 1998;45(4):661. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amos RM, Barnes WL. Phys Rev B. 1999;59(11):7708. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakowicz JR. Anal Biochem. 2001;298:1. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lakowicz JR, Shen Y, D’Auria S, Malicka J, Fang J, Gryczynski Z, Gryczynski I. Anal Biochem. 2002;301:261. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakowicz JR, Shen Y, Gryczynski Z, D’Auria S, Gryczynski I. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:875. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weitz DA, Garoff S, Gersten JI, Nitzan A. J Chem Phys. 1983;78(9):5324. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chew H. J Chem Phys. 1987;87(2):1355. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chance RR, Prock A, Silbey R. Adv Chem Phys. 1978;37:1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gersten J, Nitzan A. J Chem Phys. 1981;75(3):1139. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kummerlen J, Leitner A, Brunner H, Aussenegg FR, Wokaun A. Mol Phys. 1993;80(5):1031. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes WL. J Mod Opt. 1998;45(4):661. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porter LA, Choi HC, Ribbe AE, Buriak JM. Nano Lett. 2002;2(10):1067. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleury V, Watters WA, Devers T. Nature. 2002;416:716. doi: 10.1038/416716a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haynes CL, McFarland AD, Smith MT, Hulteen JC, Van Duyne RP. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:1898. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hua F, Cui T, Lvov Y. Langmuir. 2002;18:6712. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keir R, Igata E, Arundell M, Smith WE, Graham D, McHugh C, Cooper JM. Anal Chem. 2002;74:1503. doi: 10.1021/ac015625+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandrasekharan N, Kamat PV. Nano Lett. 2001;1(2):67. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Jiang M, Murkerjee B. Bioelectrochem Bioenerg. 2002;52:111. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verpoorte E. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:677. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200203)23:5<677::AID-ELPS677>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y, Rauch CB, Stevens RL, Lenigk R, Yang J, Rhine DB, Grodzinski P. Anal Chem. 2002;74:3063. doi: 10.1021/ac020094q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christodoulides N, Tran M, Floriano PN, Rodriguez M, Goodey A, Ali M, Neikirk D, McDevitt JT. Anal Chem. 2002;74:3030. doi: 10.1021/ac011150a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yakovleva J, Davidson R, Lobanova A, Bengtsson M, Eremin S, Laurell T, Emneus J. Anal Chem. 2002;74:2994. doi: 10.1021/ac015645b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni F, Cotton TM. Anal Chem. 1986;58:3159. doi: 10.1021/ac00127a053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belloni J. C R Phys. 2002;3:381. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eachus RS, Marchetti AP, Muenter AA. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1999;50:117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.50.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abid JP, Wark AW, Brevet PF, Girault HH. Chem Commun. 2002;7:792. doi: 10.1039/b200272h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pastoriza-Santos I, Serra-Rodriguez C, Liz-Marzan LM. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2000;221:236. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1999.6590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yguerabide J, Yguerabide EE. Anal Biochem. 1998;262:137. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yguerabide J, Yguerabide EE. Anal Biochem. 1998;262:157. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schultz S, Smith DR, Mock JJ, Schultz DA. PNAS. 2000;97(3):996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feldheim DL, Foss CA, editors. Synthesis, Characerization and Applications. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2002. Metal Nanoparticles; p. 338. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Link S, El-Sayed MA. Int Rev Phys Chem. 2000;19(3):409. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lanzetta P. Retina J Ret VIT Dis. 2001;21(5):563. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200110000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakka SG, Reinhart K, Wegscheider K, Meier-Hellmann A. Chest. 2002;121(2):559–65. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devoisselle JM, Soulie S, Maillols H, Desmettre T, Mordon S. SPIE. 1997;2980:293. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Devoisselle JM, Soulie S, Mordon S, Desmettre T, Maillols H. SPIE. 1997;2980:453. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Becker A, Riefke B, Ebert B, Sukowski U, Rinneberg H, Semmier W, Licha K. Photochem Photobiol. 2000;72(2):234. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)072<0234:mcafoi>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sokolov K, Chumanov G, Cotton TM. Anal Chem. 1998;70:3898. doi: 10.1021/ac9712310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J, Tan W, Wang K, Xiao D, Yang X, He X, Tang Z. Anal Sci. 2001;17(10):1149. doi: 10.2116/analsci.17.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lieberherr M, Fattinger Ch, Lukosz W. Surf Sci. 1987;189/190:954. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strickler SJ, Berg RA. J Chem Phys. 1962;37:814. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geddes CD, Lakowicz JR. J Fluoresc. 2002;12(2):121. doi: 10.1023/A:1021341305229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]