Abstract

We used pathogenic and nonpathogenic simian models of SIV infection of Chinese and Indian rhesus macaque (RMs) and African green monkeys (AGMs), respectively, to investigate the relationship between polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) death and the extent of viral replication and disease outcome. In this study, we showed that PMN death increased early during the acute phase of SIV infection in Chinese RMs and coincided with the peak of viral replication on day 14. The level of PMN death was significantly more severe in RMs that progressed more rapidly to AIDS and coincided with neutropenia. Neutropenia was also observed in Indian RMs and was higher in non-Mamu-A*01 compared with Mamu-A*01 animals. In stark contrast, no changes in the levels of PMN death were observed in the nonpathogenic model of SIVagm-sab (sabaeus) infection of AGMs despite similarly high viral replication. PMN death was a Bax and Bak-independent mitochondrial insult, which is prevented by inhibiting calpain activation but not caspases. We found that BOB/GPR15, a SIV coreceptor, is expressed on the PMN surface of RMs at a much higher levels than AGMs and its ligation induced PMN death, suggesting that SIV particle binding to the cell surface is sufficient to induce PMN death. Taken together, our results suggest that species-specific differences in BOB/GPR15 receptor expression on PMN can lead to increased acute phase PMN death. This may account for the decline in PMN numbers that occurs during primary SIV infection in pathogenic SIV infection and may have important implications for subsequent viral replication and disease progression.

The primary acute phase of HIV infection ends in host/virus equilibrium. An increasing amount of evidence suggests that this acute phase dictates the rate of progression toward AIDS. In particular, the steady-state plasma viral load that is reached at the end of this phase, between 2 and 6 mo after infection, is predictive of the time to AIDS onset (1).

Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN)4 are key components of the first line of defense against bacterial and fungal pathogens (2). They contribute to the early innate response by rapidly migrating to inflamed tissues, where their activation triggers microbicidal mechanisms such as the release of proteolytic enzymes and antimicrobial peptides and the rapid production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Several lines of evidence also point to PMN involvement in the pathophysiology of viral infections. Thus, PMN play a key role, at least through defensin expression, in controlling viruses (3–5). Moreover, human neutrophil α-defensins 1–4 have been reported to inhibit HIV replication in vitro (6–8), and activated neutrophils exert cytotoxic activity against HIV-infected cells (9). PMN also attract and stimulate other immune cells through the release of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines (10) and through direct interactions with immune cells such as dendritic cells (11), implying that PMN have the potential to orchestrate adaptative immune responses. PMN might thus be key cells in the early events that control HIV/SIV replication.

Apoptosis is an intrinsic cellular process that can be regulated by external factors. In particular, PMN activation by circulating bacterial products, endogenous cytokines, and other proinflammatory mediators can affect the rate of PMN apoptosis (12–14). Inappropriate PMN survival and persistence at sites of inflammation are thought to contribute to the pathology of chronic inflammatory diseases (15). In contrast, shortened PMN survival due to apoptosis may contribute to susceptibility to severe and recurrent infections in some pathological situations (16, 17).

PMN apoptosis has rarely been investigated in HIV-infected patients. Increased PMN apoptosis has been reported, particularly in the later stages of HIV disease (18–20), but the mechanisms have not been identified. Likewise, PMN apoptosis during the primary acute phase of viral infection and its potential relationship with the rate of subsequent disease progression have not been addressed. SIV infection of macaques is currently the experimental model of choice for studying early events of acquired immunodeficiency virus infection. Whereas rhesus macaques (RMs) infected with SIV (SIVmac) usually progress to AIDS in 1–2 years, African nonhuman primates (NHPs) infected with their species-specific SIV rarely develop disease. Previous studies of natural, nonpathogenic primate models of SIV infection, such as SIVagm infection of African green monkeys (AGMs), SIVsmm or SIVmac infection of sooty mangabeys, and SIVmnd-1 and SIVmnd-2 infection of mandrills have consistently shown that, in these animals, the levels of plasma viral load are similar to those observed in HIV-infected humans and SIVmac-infected RMs (21–29). However, only HIV-infections in humans and SIVmac infections in RMs lead to progressive CD4+ T cell depletion and AIDS. In pathogenic models of HIV and SIV infections, there is a large number of reports showing increased apoptosis of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells (30–39) compared with nonpathogenic models. Understanding the basis of pathogenic and nonpathogenic host-virus relationships is likely to provide important clues regarding AIDS pathogenesis.

In this article we report a comparative study of the initial interactions between SIV and PMN in two different species of NHPs that exhibit a divergent outcome of the infection, i.e., non-natural RM hosts in which the infection leads to CD4+ T cell depletion and AIDS, and natural AGMs hosts where the infection is typically nonpathogenic. We performed a longitudinal study of experimentally SIV-infected NHPs (Chinese RMs infected with SIVmac251 and a nef-deleted SIVmac251, Indian RMs infected with SIVmac251, and AGMs infected with SIVagm-sab, where sab is sabaeus). We analyzed, during primary SIV infection, PMN kinetics and apoptosis with respect to subsequent disease progression. We also examined the molecular mechanisms underlying PMN death in this setting and the effect of blocking protease activation. Major indices of PMN functional activity (surface CD11b expression, migration, and the respiratory burst) were also measured at baseline and after ex vivo stimulation. Our data demonstrate that the early level of apoptosis of PMN is associated with progression to AIDS.

Materials and Methods

Animals and virus infection

RMs (Macaca mulatta) of Chinese origin were inoculated i.v. with either the pathogenic SIVmac251 strain (ten 50% animal infectious doses (AID50)) or the live attenuated SIVmac251Δnef strain. All of the animals were challenged with the same batch of virus, titrated in vivo in rhesus macaques, and stored in liquid nitrogen. AGMs of sabaeus species were experimentally infected with three hundred 50% tissue culture infective doses of SIVagm.sab92018 strain. As previously described (23), this virus derives from a naturally infected AGM and has never been cultured in vitro. Animals were demonstrated as being seronegative for STLV-1 (simian T leukemia virus type-1), SRV-1 (type D retrovirus), herpes B viruses, and SIVmac. Animals were housed and cared for in compliance with existing French regulations. Blood samples were immediately cooled to 4°C to avoid PMN activation, and the same technical procedures were used for each experiment.

The Indian rhesus macaques (M. mulatta) were housed at the Bioqual animal facility according to standards and guidelines as set forth in Animal Welfare Act and “The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (40) and according to animal care standards deemed acceptable by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-International (AAALAC). All experiments were performed following institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) approval. The study included 32 animals that were infected i.v. with 100 AID50 SIVmac251.

Reagents

The reagents and sources were as follows: allophycocyanin-conjugated annexin V, 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD), FITC-anti-CD14 mAb, PE-anti-CD11b mAb, PE-anti-CXCR4 mAb (clone 12G5), purified anti-BOB/GPR15 mAb (GPR15), and purified anti-CCR5 mAb (clone 3A9) (all from BD Pharmingen); purified anti-Bax mAb (N-20) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); purified anti-Bak mAb (aa 2–14) (Calbiochem); FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse IgG (DakoCytomation); Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (Molecular Probes, Interchim); FITC-anti-gp120 (SIVmac251) Ab (Microbix Biosystems); fMLP (Sigma-Aldrich); N-benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-DL-Asp(Ome)-fluoromethylketone (z-VAD-fmk) and N-acetyl-Leu-Leu-Nle (ALLN) (Calbiochem); and 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6) (Molecular Probes).

Determination of viral load

RNA was extracted from plasma of SIV-infected monkeys using the TRI Reagent BD kit (Molecular Research Center). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine viral loads as previously described (41).

Measurement of PMN apoptosis

PMN apoptosis was measured immediately after sampling and after 4 h of incubation in 24-well tissue cultures plates at 37°C with 5% CO2. Apoptosis of whole blood PMN was quantified by annexin V and 7-AAD staining as previously described (15). Whole blood samples (100 μl) were washed twice in PBS, incubated with FITC-anti-CD14 and PE-anti-CD11b Abs for 15 min, and then incubated with allophycocyanin-annexin V for 15 min. After dilution in PBS (500 μl), the samples were incubated with 7-AAD at room temperature for 15 min and analyzed immediately by flow cytometry.

Loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential (Δψm) was assessed with the DiOC6 reagent. Samples were loaded with DiOC6 (40 nM) for 15 min at 37°C then stained with PE anti-CD11b and PerCP-Cy5-5 anti-HLA-DR Abs for 30 min at 4°C.

Study of CD11b and chemokine receptor expression at the PMN surface

To study CD11b expression, whole blood samples from each RM were either kept on ice or incubated with fMLP (10−6 M) or PBS at 37°C for 5 min, and then 100 μl of the suspension was incubated at 4°C for 30 min with PE-anti-CD11b Ab. To study chemokine receptor expression, samples (50 μl) were incubated at 4°C for 1 h with PE-anti-CXCR4, purified anti-BOB/GPR15, or purified anti-CCR5 Abs (10 μg/ml) or isotype controls. To measure BOB/GPR15 or CCR5 expression, samples were washed with PBS then incubated at 4°C for 45 min with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) or FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse IgG.

Intracellular Bax and Bak assay

Cells were fixed and permeabilized (Perm & Fix; BD Pharmingen) before adding Abs recognizing the active form of Bax and Bak proteins (conformational NH2-terminal epitope). These Abs have been previously reported to cross-react with macaques cells (42, 43). After washing, a FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG Ab was added for 30 min at 4°C.

SIV binding to PMN

PMN were pretreated with isotype controls, anti-CCR5, or anti-BOB/GPR15 Abs for 30 min and then incubated in the presence of 400 AID50 of the pathogenic SIVmac251 strain for 30 min. After washing, a FITC-anti-gp120 (SIVmac251) Ab was added for 30 min and fluorescence intensity was assessed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

We used a BD FACScalibur (BD Immunocytometry Systems). PMN functions were analyzed using CellQuest software. To measure apoptosis in whole blood, PMN were identified as CD11bhighCD14low cells and 2 × 105 events were counted per sample. In other experiments, forward and side scatter were used to identify the PMN population and to gate out other cells and debris; 10,000 events were counted per sample.

Measurement of neutrophil chemotactic activity

Chemotaxis was measured in Transwell plates (Corning Costar) containing 3-μm pore-size polyvinylpyrrolidone-free polycarbonate filters (44). The lower well of each chamber received 600 μl of chemoattractant solution (IL-8 at 25 ng/ml; fMLP at 10−7 M) diluted in PBS plus 1% human serum albumin. Spontaneous migration was measured with PBS plus 1% human serum albumin instead of chemoattractant solution. The upper well received 100 μl of whole blood diluted 1/10 in PBS. The chambers were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. After incubation, 50 μl was removed from the lower well and erythrocytes were lysed. The total number of PMN added to the upper well and the number of PMN that migrated into the lower well were counted by flow cytometry using TruCount tubes.

Proviral DNA analysis

Whole blood collected on EDTA was stained with FITC-anti-CD11b and PercP-PeCy5-anti-HLA-DR Abs for 30 min at 4°C. Erythrocytes were lysed and the cells were then washed twice and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. PMN were highly purified by cell sorting (FACsVantage; BD Biosciences) on the basis of their size, granularity, and phenotype (CD11bhighHLA-DRlow); purity exceeded 98%. DNA was quantified by real-time quantitative PCR as previously described (41, 45).

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as means ± SEM. Comparisons were based on ANOVA and Tukey’s posthoc test using Prism 3.0 software. Correlations were identified by means of the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (ρ).

Results

Increased PMN apoptosis during primary SIV infection in RMs

Because apoptosis is considered to be a major regulatory mechanism of PMN turnover (46), we examined Chinese RMs infected with either the pathogenic SIVmac251 strain (SIV+ group; n = 6) or the attenuated Δnef isolate (SIVΔnef; n = 4) and AGMs infected with SIVagm-sab (n = 5) to determine whether different patterns of disease progression were associated with distinct rates of PMN apoptosis.

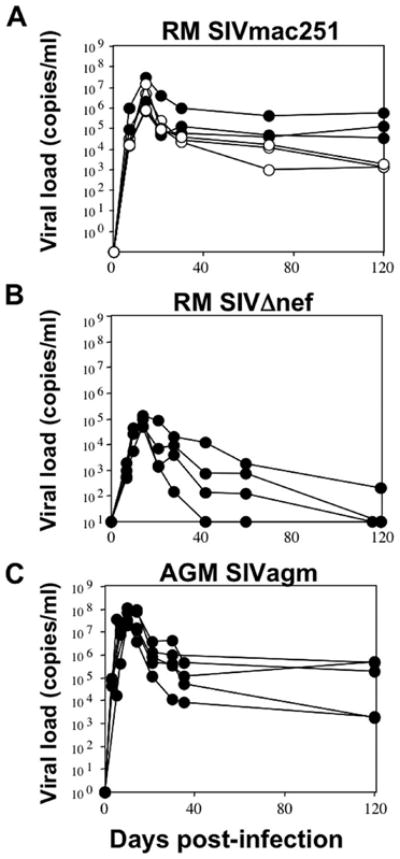

We first assessed the dynamics of viral load in these different groups of SIV-infected NHPs (Fig. 1). In Chinese RMs, viremia peaked between days 11 and 14 with values ranging between 7.0 × 105 and 3.2 × 107 RNA copies/ml in Chinese RMs infected with SIVmac251 and between 4.8 × 104 and 1.3 × 105 RNA copies/ml SIVΔnef. In AGMs, viremia peaked between days 8 and 14 and the values ranged between 7.9 × 106 and 1.2 × 108 RNA copies/ml. The set point levels (4 mo) in AGMs ranged between 1.8 × 103 and 5.3 × 105 RNA copies/ml whereas in Chinese RMs infected with SIVmac251 it ranged between 1.4 × 103 and 5.7 × 105 RNA copies/ml, while the viral load was extremely low in SIVΔnef. We retrospectively classified RMs as slow and moderate progressors based on viral load at 4 mo (<104 RNA copies/ml and 104–105 RNA copies/ml, respectively) as previously described (45). Thus, these data are consistent with numerous previous observations (24, 26, 27, 47–50) indicating that both peak and set point viremia are similar in pathogenic and nonpathogenic primate models.

FIGURE 1.

Viral dynamics during primary SIV infection. A, Kinetic analysis of viremia in SIV-infected RMs with the SIVmac251 strain (RM SIVmac251). Three were slow (○) and three were moderate progressors (●). B, Kinetic analysis of viremia in SIV-infected RMs (n = 4) with the SIVmac251Δnef strain (RM Δnef). C, Kinetic analysis of viremia in SIV-infected AGMs (n = 5) with the SIVagm-sab (AGM SIVagm strain).

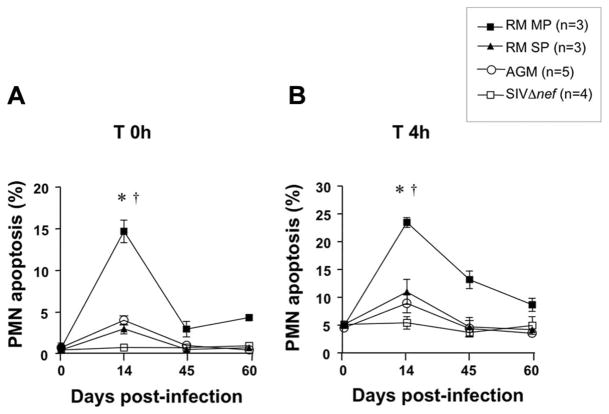

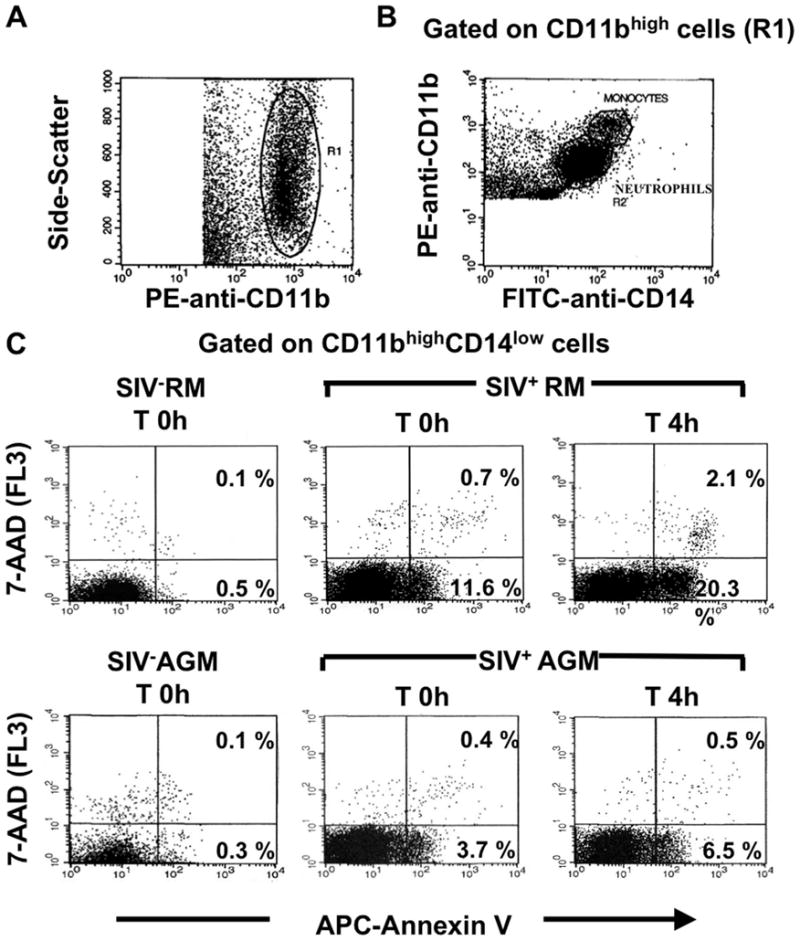

One particularity of this study is that we analyzed PMN apoptosis by flow cytometry in whole blood Chinese RMs and AGMs (Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 3A, a peak of spontaneous apoptosis (time 0 h) was observed in the SIV+ infected Chinese RMs group on day 14 (range 3–17%). PMN apoptosis on day 14 was significantly higher in future moderate progressors than in slow progressors. Thereafter, the percentage of apoptotic cells declined. After 4 h of incubation at 37°C, a similar but more marked pattern was observed in SIV+ infected RMs (Fig. 3B). In contrast, no significant change was observed in the SIVΔnef group. This latter result is in keeping with previous reports that the apathogenic strain is associated with milder immune dysfunction and with a lower plasma viral load (45). In SIVagm-infected AGMs the level of PMN apoptosis was not significantly different as compared with baseline throughout the acute phase of infection despite levels of viral replication that are similar to those observed in SIVmac251-infected Chinese RMs.

FIGURE 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of whole blood PMN apoptosis. A, Dot plot showing PE-anti-CD11b staining against the side-scatter parameter. A first gate (R1) was drawn around CD11b+ cells. B, Dot plot showing PE-anti-CD11b against FITC-anti-CD14 staining gated on R1. A second gate (R2) was drawn on CD14low cells to eliminate monocytes (CD14high cells) from the analysis. C, The combination of allophycocyanin (APC)-annexin V and 7-AAD staining distinguished early apoptotic cells (annexin V+/7-AAD−) and late apoptotic cells (annexin V+/7-AAD+) in an SIV− RM at time (T) 0 h and in an SIV+ RM (day 14) at T 0 h and T 4 h, as well as in an SIV− AGM at T 0 h and in an SIV+ AGM (day 14) at T 0 h and T 4 h.

FIGURE 3.

Comparative analysis of PMN apoptosis during primary infection of rhesus macaques with the pathogenic SIVmac251 strain or the attenuated SIVΔnef strain, and AGMs. Monkeys were infected i.v. with 10 AID50 of the pathogenic SIVmac251 strain (RM, n = 6), the attenuated SIVΔnef strain (SIVΔnef, n = 4), or 300 TCID50 of SIVagm strain (AGM, n = 5). Viral load measured 4 mo after infection retrospectively classified the RM monkeys as slow progressors (RM SP, n = 3) or moderate progressors (RM MP, n = 3). PMN apoptosis was studied immediately after sampling (time (T) 0 h) (A) and after incubating whole blood in 24-well tissue cultures plates at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 4 h (T 4 h) (B). Results are expressed as the percentage of annexin V+/7AAD− cells (early apoptotic cells).*, p < 0.05, significantly different from SIVΔnef macaques; †, p < 0.05, significantly different from RM SP.

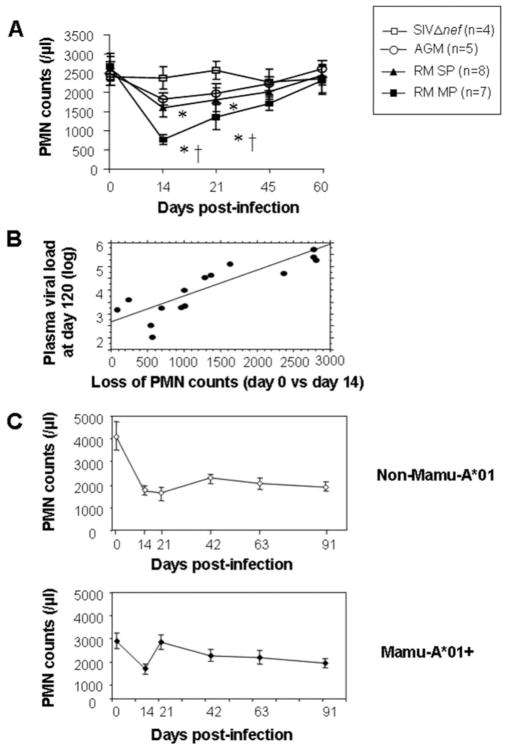

A significant transient decrease in the PMN count was also observed during primary infection of RMs with the pathogenic SIV-mac251 strain. The fall was maximal on day 14, when it was significantly larger in moderate progressors (n = 8) than in slow progressors (n = 7) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). The degree of PMN loss correlated with the viral load plateau value on day 120 (ρ = 0.8; p = 0.0009) (Fig. 4B), which is predictive of clinical outcome (1). In contrast, PMN counts were not significantly changed in SIVΔnef-infected macaques as well as in SIVagm-infected AGMs (Fig. 4A). Apoptosis values in individual SIV+ RMs on day 14 correlated negatively with the corresponding PMN counts (ρ = −0.9; p = 0.01).

FIGURE 4.

Comparative analysis of PMN counts in peripheral blood of RMs during primary infection with the pathogenic SIVmac251 strain or the attenuated SIVΔnef strain and AGMs. A, PMN count kinetics in Chinese RMs. During the first 2 mo, variations in PMN counts were monitored in peripheral blood from SIVΔnef (n = 4), SIV+ RMs (n = 15) (slow progressors, RM SP, and moderate progressors, RM MP), and AGMs (n = 5).*, p < 0.05, Significantly different from SIVΔnef at the same time; †, p < 0.05, significantly different from RM SP at the same time. B, Regression analysis comparing the loss of PMN (day 0 value minus day 14 value) and viremia on day 120 in Chinese rhesus macaques (ρ = 0.83; p = 0.0009). C, PMN count kinetics in Mamu-A*01+ and non-Mamu-A*01 Indian RM.

Because we and others have shown that RMs of Indian origin are more susceptible and progress more rapidly toward AIDS (29, 51), we determined whether neutropenia occurs during primary SIV infection in Indian monkeys. The plasma viral loads in Indian RMs at viral set point (day 120) were 9.7 ± 5.7 × 105 RNA copies/ml (4.68 ± 0.21 log) (200–1.7 × 107), and this was significantly higher than Chinese RMs. As expected, on day 120 plasma viral loads were higher in non-Mamu-A*01 Indian RMs compared with the Mamu-A*01+ animals (5.3 ± 0.25 log RNA copies/ml vs 4.0 ± 0.2 log RNA copies/ml for non-Mamu-A*01 and Mamu-A*01+, respectively, p < 0.003). Indian RMs also showed a significant decrease in blood PMN numbers following infection (Fig. 4C). The PMN numbers decreased between day 0 and 14 × 1724 ± 303 cells/μl (n = 32; p < 0.001). This decrease was also found when animals were separated into Mamu-A*01 positive (1220 ± 210 cells/μl; n = 18; p < 0.001), which generally show better viral control (52, 53), and non-Mamu-A*01 animals (2372 ± 608 cells/μl, p < 0.001, n = 14). The decrease was significantly higher in non-Mamu-A*01 animals compared with the Mamu-A*01 (p < 0.03).

However, in contrast to Chinese RMs, in Indian RMs the decrease in PMN was not transient but sustained and never returned to normal (Fig. 4C). On day 91 postinfection both Mamu-A*01+ and non-Mamu-A*01 animals continued to have reduced blood PMN numbers. On day 91, Mamu-A*01+ animals had a decrease of 1280 ± 385 cell/μl from day 0, whereas in non-Mamu-A*01 animals this decrease was 2222 ± 549 cells/μl. Thus, Indian RMs show a sustained drop in PMN numbers, and this again correlates with the increased pathogenicity of SIV infection in Indian RMs compared with Chinese RMs (29, 51).

PMN dysfunction during primary SIV infection in RMs

PMN exhibit a variety of functional defects during the asymptomatic phases of HIV infection (54) and feline immunodeficiency virus infection (55). We thus examined whether the increase in PMN apoptosis observed early after SIV infection was associated with impaired CD11b expression, PMN migration, or ROS production, which are crucial for PMN functional activities.

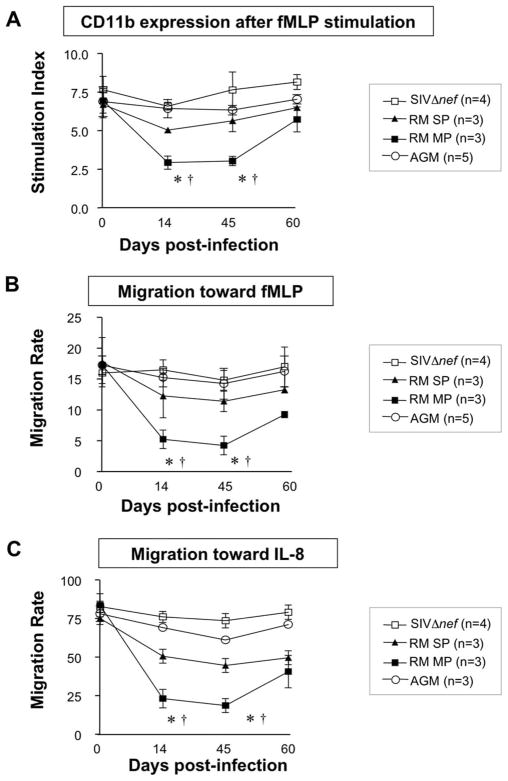

During the acute phase, basal CD11b expression and ROS production were similar to the values observed before infection (data not shown), showing that PMN are not activated during primary SIV infection. Following fMLP stimulation we observed a transient decrease between days 14 and 45 in CD11b expression in SIV+ infected RMs, whereas no significant change in maximal CD11b expression was observed in the SIVΔnef group (Fig. 5A). In SIVagm-infected AGMs the level of PMN values remained similar to baseline throughout the acute phase of infection. In parallel, PMN migration toward fMLP and IL-8 was impaired in RMs compared with SIVΔnef animals or with AGMs (Fig. 5, B and C). The decrease in PMN responses in RMs was significantly larger in moderate progressors than in slow progressors (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5). In addition, in RMs the decrease in stimulated PMN responses on day 14 (CD11b expression and migration) was associated with the level of PMN apoptosis (ρ = 0.82 and p = 0.02, ρ =0.95 and p = 0.01, and ρ = 0.91 and p = 0.02, respectively, for CD11b expression, migration toward fMLP, and migration toward IL-8). Thus, the decreased PMN responses to fMLP and IL-8 in RMs in terms of CD11b expression and migration are associated with abnormal PMN sensitivity to cell death. However, we found that PMN dysfunction persisted on day 45, when the level of apoptosis had fallen.

FIGURE 5.

Comparative analysis of CD11b expression and PMN migration during primary infection of RMs with the pathogenic SIVmac251 strain (n = 6), or the attenuated SIVΔnef strain (n = 4) and AGMs (n = 5). A, Whole blood samples from SIVΔnef, SIV+ RMs (slow progressors, RM SP, and moderate progressors, RM MP) and AGMs were incubated with PBS or fMLP (10−6M) at 37°C for 5 min and then stained with PE-anti-CD11b Ab at 4°C for 30 min. The results are expressed as a stimulation index (mean fluorescence intensity of the sample incubated with fMLP/MFI of the sample incubated with PBS). B and C, PMN migration toward fMLP (10−7 M) (B) or IL-8 (25 ng/ml) (C) was measured in Trans-well plates as described in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as the migration rate: (number of PMN in the lower well after migration/number of PMN applied to the upper well before migration) × 100. *, p < 0.05, Significantly different from SIVΔnef macaques; †, p < 0.05, significantly different from RM slow progressors.

PMN death during primary SIV infection is associated with mitochondrial damage and is calpain-dependent

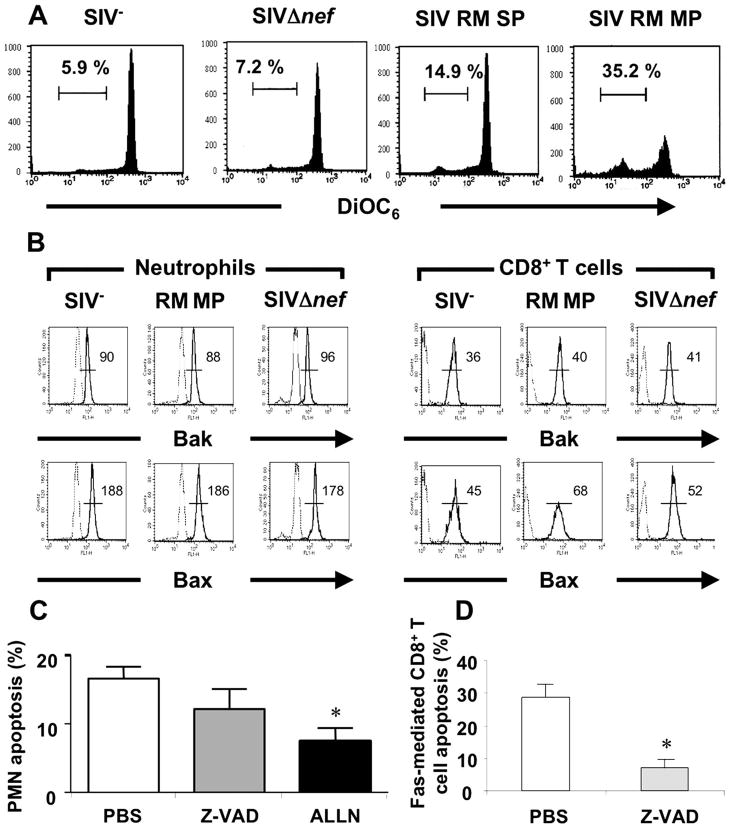

Apoptosis involves a cascade of signaling events in which the mitochondrion is a key sensor and caspases are the cell death effectors (56). To determine the possible role of mitochondria in PMN apoptosis in this setting, we measured Δψm with DiOC6. We found that PMN collected from SIV+ RMs on day 14 displayed a loss of Δψm as compared with PMN from healthy controls and fSIVΔnef-infected macaques and that the percentage of PMN displaying Δψm was more marked in future moderate progressors (32.3 ± 5.1) than in slow progressors (13.8 ± 3.5) (Fig. 6A). PMN from healthy controls and SIVΔnef-infected macaques showed no difference in Δψm loss. Because Bax and Bak, proapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, relocate and induce Δψm loss (56), we examined whether these proteins were activated in PMN from SIV+ macaques using Abs known to cross-react with macaques cells (42, 43). Our results indicated that Δψm loss is not associated with changes in the NH2-terminal epitope availability of Bax or Bak expression (the active forms of Bax and Bak, which are associated with cell death), demonstrating that mitochondrial changes in PMN in this setting are Bax -and Bak-independent (Fig. 6B). In contrast, active Bax was increased in CD8+ T cells from SIV-infected RM while Bak was not affected in these cells (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

PMN from SIV+ rhesus macaques display mitochondrial insult. A, Whole blood samples from healthy controls (SIV−), SIVΔnef and SIV+ RMs (slow progressors, RM SP, and moderate progressors, RM MP) on day 14 postinfection were incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Δψm loss was measured by flow cytometry using DiOC6 and expressed as the percentage of DiOC6low cells. One experiment representative of three. B, Bax and Bak staining of PMN and CD8+ T cells from healthy control (SIV−), SIVΔnef macaque, and RM moderate progressor (RM MP). One experiment representative of three is shown. C, Whole blood samples from SIV+ rhesus macaques on day 14 postinfection were incubated at 37°C for 4 h with PBS, z-VAD-fmk (a broad caspase inhibitor) (10 μM), or ALLN (a calpain inhibitor) (50 μM). Apoptosis was studied as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6). D, Efficacy of z-VAD-fmk on apoptosis of macaques cells. CD8+ T cells from SIV+ RMs on day 14 postinfection were pretreated with PBS or z-VAD-fmk (10 μM) and then incubated in the presence of rhCD95L (200 ng/ml). T cell apoptosis was analyzed using annexin V+ staining. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3).*, p < 0.05, Significantly different from samples incubated with PBS.

To determine the possible involvement of caspases in this PMN apoptosis, we used the broad spectrum caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk. This inhibitor has been previously reported to inhibit caspases in nonhuman primates (37, 42). In agreement with previous reports (37, 42), z-VAD-fmk inhibited Fas-mediated apoptosis of CD8+ T cells from SIV-infected RMs (Fig. 6D). z-VAD-fmk (10 μM), however, failed to have any effect on PMN apoptosis (Fig. 6C). In contrast, ALLN (50 μM), a highly specific calpain inhibitor, significantly reduced PMN apoptosis (Fig. 6C). Thus this PMN apoptosis was calpain dependent and caspase independent.

SIV induces PMN death in the absence of productive viral replication

Accelerated PMN death during primary SIV infection may be related either to PMN infection or to external apoptogenic factors. We used flow cytometry to sort highly purified PMN (CD11bhighHLA-DRlow) and CD4+ T cells (>98 and 99% pure, respectively) at the peak of the acute phase (day 14). Approximately 0.1–1% of CD4+ T cells were infected as previously reported (41, 45), whereas we detected no SIV DNA in up to 1 million PMN. Moreover, no TNF-α or IL-8 (proapoptotic and anti-apoptotic cytokines, respectively) (57, 58) was detected in the plasma of either SIV+ or SIVΔnef macaques (data not shown) during the acute phase. As our data implied that PMN death is caspase independent in this setting, we did not seek a role of death ligands such as FasL and Trail, which are also capable of killing PMN via caspase activation (59, 60).

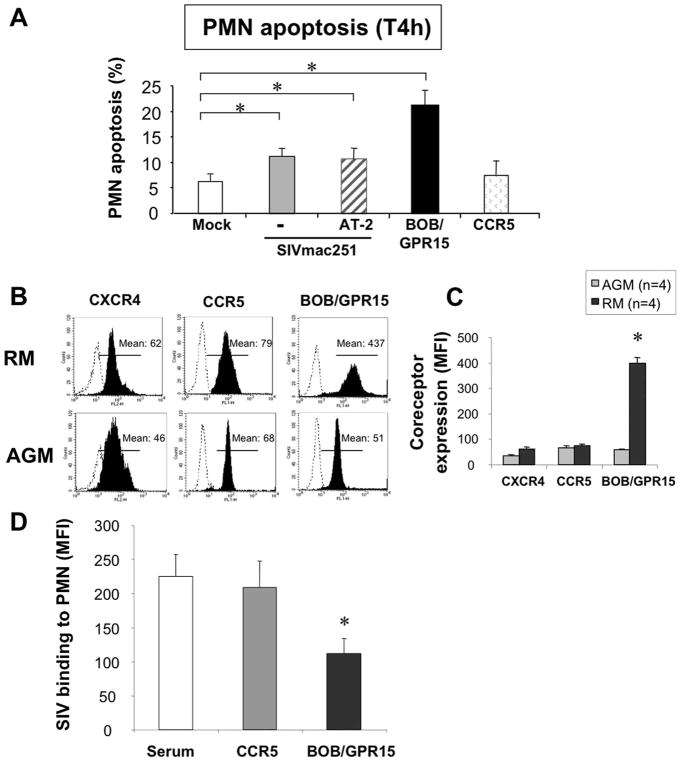

We and others have shown that simple binding and/or penetration of HIV (without integration) can prime death (61–66), implying that collateral cell damage induced by interaction of the viral envelope glycoprotein (gp120) with molecules expressed by PMN, and particularly chemokine receptors, may account for the observed increase in PMN death. We therefore incubated whole blood samples from healthy macaques with either SIVmac251 or mock as control. We found that SIVmac251 strain (400 AID50) significantly increased apoptosis of PMN derived from RMs (Fig. 7A); however, a 10-fold lower dose of SIVmac251 strain was unable to prime PMN for death (data not shown). This apoptosis-inducing effect of SIVmac251 on PMN is unlikely due to viral infection and replication, as the short incubation time (4 h) of these experiments is incompatible with viral replication in nondividing cells (64, 65). This was further supported by the finding that treatment of whole blood samples with didanosine (1 μM), a reverse transcriptase inhibitor, also did not prevent SIV-induced PMN death. Finally, aldrithiol-2-inactivated SIVmac251 could also prime PMN for apoptosis (Fig. 7A). Thus, viral infection and replication is not required for this PMN apoptosis, and this suggests a possible receptor-mediated effect. SIV binds to distinct chemokine receptors such as BOB/GPR15 and CCR5 (67–69). Flow cytometric analysis of chemokine receptors (CXCR4, CCR5, and BOB/GPR15) revealed that PMN from healthy RMs expressed BOB/GPR15 at higher levels than healthy AGMs (Fig. 7, B and C). In a SIV surface binding assay we demonstrated that SIV was surface bound to PMN and that this binding was BOB/GPR15 mediated, as Abs directed to BOB/GPR15 reduce SIV binding on PMN (Fig. 7D). To directly demonstrate that BOB/GPR15 binding by SIV was mediating this PMN apoptosis, we tested whether cross-linking BOB/GPR15 could induce PMN apoptosis. Indeed, we found that incubation with a BOB/GPR15-specific Ab induced PMN death (Fig. 7A), while CCR5-specific Ab were less potent in inducing death. Preincubation with z-VAD-fmk did not prevent cell death (data not shown). Taken together, the above findings support the idea that SIV particle binding to the chemokine receptor BOB/GPR15 on the PMN surface, rather than productive viral replication, drives PMN death. Furthermore, differences in the expression level of coreceptors such as BOB/GPR15 between different nonhuman primates might be responsible for greater PMN death in RMs compared with AGMs.

FIGURE 7.

SIV primes PMN for death. A, Whole blood samples from healthy controls (SIV−) were incubated for 4 h at 37°C in the absence (mock) or presence of 400 AID50 of the pathogenic SIVmac251 strain that has been either untreated (−) or treated with aldrithiol-2 (AT-2). Cells were also incubated with anti-BOB/GPR15 or anti-CCR5 Abs. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). Purified sera were used as controls for chemokine receptors Abs; no difference in the percentage of dying cells was observed relative to the mock control (data not shown).*, p < 0.05, Significantly different from mock-incubated samples. B, Representative CXCR4, CCR5 and BOB/GPR15 expression on PMN from a healthy macaque and a healthy AGM, measured by flow cytometry. Dotted line histograms show isotype control stains. Filled histograms show specific Ab staining. C, Quantitative expression of CXCR4, CCR5, and BOB/GPR15 expression on PMN from healthy RMs (n = 4) and healthy AGMs (n = 4). Values are means ± SEM.*, p < 0.05, Significantly different from AGM. D, PMN from healthy controls (SIV−) were pretreated with purified serum, anti-CCR5 Ab, or anti-BOB/GPR15 Ab and then incubated in the presence of 400 AID50 of the pathogenic SIVmac251 strain. Binding at the cell surface was revealed by FITC-anti-gp120 (SIVmac251) Ab.*, p < 0.05, Significantly different from serum-incubated samples. MFI, Mean fluorescence intensity.

Discussion

Our results show an increased PMN death during the acute phase of SIV infection in Chinese RMs that coincided with a decline in PMN number. The level of PMN death was significantly more severe in Chinese RMs that progressed more rapidly to AIDS. Indian RMs had higher and more sustained neutropenia compared with Chinese RMs, and this is in agreement with the overall higher pathogenicity of SIV infection in Indian compared with Chinese RMs. Pathogenic and nonpathogenic models of HIV and SIV infections have been shown to differ in the magnitude of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cell apoptosis, with pathogenic models exhibiting higher levels of such apoptosis (30–39). In this study we also show that neutrophils are more susceptible to death in pathogenic compared with nonpathogenic SIV infection. This apoptosis is associated with increased neutropenia in the pathogenic models. Neutropenia was absent, however, from the SIVagm-infected AGMs. Thus, the magnitude and the duration of neutropenia are associated with pathogenicity in these SIV models.

In addition, we found that BOB/GPR15, a SIV coreceptor, was strongly expressed on the PMN surface of Chinese RMs, and its ligation induced PMN death. BOB/GPR15 expression was strongly lower on the PMN surface from AGMs, and no changes in the levels of PMN death were observed during primary infection in a nonpathogenic SIV model. Taken together, these results suggest that PMN death during the acute phase may be related, at least in part, to species-specific host factors and may play an important role in disease progression.

Increased PMN apoptosis has been reported in chronically HIV-infected patients (19–21), and this phenomenon might account for the tendency of neutropenia to occur late in SIV infection (our unpublished data) and human HIV infection (70, 71). In this study we demonstrate, for the first time, that spontaneous PMN apoptosis is augmented during primary SIV infection of RMs and that this increase coincides with neutropenia. Moreover, the extent of PMN apoptosis and neutropenia is associated with the rate of subsequent pathogenicity and progression to AIDS. Given the role of defensins in the control of viral replication (3–8) and the fact that PMN are a major source of α-defensins 1–4 (2), such PMN defects may play a key role in early viral replication and dissemination within the host and might therefore be a key determinant of disease outcome. The fact that SIVagm-infected AGMs do not display any major increase in PMN apoptosis in the context of significant levels of viral replication suggests that the direct effects of SIV replication alone are unlikely to account for the high levels of PMN apoptosis observed in Chinese RMs at the time of peak viremia. Moreover, no SIV DNA was detected in sorted PMN from SIV-infected Chinese RMs. Similarly, an increased lymphocyte susceptibility to apoptosis independent of infection (“bystander effect”) has been proposed as one of the main mechanisms responsible for the CD4+ T cell depletion in vivo during pathogenic HIV and SIV infections (39).

Indian RMs had higher and more sustained neutropenia compared with Chinese RMs, which is consistent with the overall higher pathogenicity of SIV infection in Indian compared with Chinese RMs. In contrast to Chinese RMs, a day 14 decrease in PMN in Indian RMs did not correlate with viral loads or CD4 counts. It is unclear why this correlation is not present in the Indian RMs, but the finding that the sustained decrease in PMN in these animals may suggest that the factors that contribute to the higher viral loads in these animals retain the PMN decrease. Although both Mamu-A*01+ and non-Mamu-A*01 Indian RM showed sustained neutropenia, Mamu-A*01+ animals had significantly lower decrease in PMN from baseline, and this again is in agreement with the better viral control that these animals have compared with non-Mamu-A*01 Indian RMs (52, 53). Indeed, in our study non-Mamu-A*01 Indian RMs had significantly higher viral loads compared with the Mamu-A*01+ Indian RMs. It should be noted that although the presence of alleles such as Mamu-A*01 overall provides better control, this is not in itself predictive of viral control (72, 73). Another possible explanation for the difference between Indian and Chinese RM neutropenia, with the former exhibiting sustained neutropenia, is that Indian RMs were challenged with a higher dose of SIVmac251 compared with the Chinese RMs. It will be of interest in the future to determine whether high dose viral challenge determines whether sustained neutropenia is also established in Chinese RMs. Overall, our studies suggest that the degree of pathogenicity of SIV infection in a particular host correlates with the magnitude and duration of neutropenia in nonhuman primates.

There are two main pathways of apoptosis. The extrinsic pathway is initiated upon the binding of so-called “death receptors” (belonging to the TNF receptor family) to their ligands, whereas the intrinsic pathway is death receptor independent. These pathways converge at a central sensor, the mitochondrion, that releases apoptogenic factors into the cytosol leading to the activation of effector caspases. Growing evidence implicates caspase-independent mechanisms of cell death in most cell types, including PMN (74–77). Indeed, we found that PMN death in SIV-infected macaques was not prevented by a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor, z-VAD-fmk. Our data demonstrate that PMN death in this setting involves a calpain-dependent pathway that has also been reported to play a key role in the spontaneous PMN death of healthy donors (77, 78). Interestingly, a calpain-dependent pathway was recently reported to be involved in the death of PMN from chronically HIV-infected patients (79). We also found that PMN from SIV-infected Chinese RMs displayed mitochondrial injury, reflected by a loss of Δψm. However, mitochondrial membrane permeabilization occurs independently of a change in the conformation of Bax and Bak, which is considered to be a major event in the fall of Δψm. Therefore, it remains to determined by which mechanisms the mitochondrial outer membrane is permeabilized.

Finally, we found that SIV particles prime PMN for death in vitro. However, PMN do not need to be productively infected to undergo death. These results for PMN death are consistent with other reports indicating that HIV/SIV sensitize CD4+ T cells to undergo apoptosis in the absence of viral replication and immune activation (62, 64, 65). Similarly, it has been shown that exposure to the HIV envelope protein results in apoptosis of NK cells (66). We observed no increase in PMN death and no neutropenia in Chinese RMs infected with the attenuated strain SIVΔnef. This might be related to slower acute phase SIVΔnef replication relative to the pathogenic strain (45). Indeed, we found that in vitro a 10-fold lower dose of SIVmac251 strain did not prime PMN death. Thus, although we cannot exclude the possibility that nef-deleted SIV may also induce cell death in vitro, the threshold reached in vivo is probably too low to prime PMN for death. Together, our data suggest that SIV virions themselves are at least partly responsible for priming PMN death. CD4 is not expressed on PMN (data not shown), and HIV/SIV bind to PMN via other membrane receptors (80, 81). We observed increased BOB/GPR15 expression at the surface of PMN from healthy Chinese RMs, whereas it was lower expressed on the surface of PMN from AGMs; the other coreceptors, CCR5 and CXCR4, were not different. Moreover, using specific Abs (because the natural ligand is unknown), we found that BOB/GPR15 engagement primed PMN from Chinese RMs for death in a manner similar to that of the virus itself. These results showing that this constitutive receptor may induce a cell death signal suggests a distinct cell signaling pathway following coreceptor ligation by SIV vs that involved in the physiological response to the unknown BOB/GPR15 ligand. This would be consistent with what has previously been shown for CCR5 and CXCR4. Whereas the natural ligands such as RANTES and SDF1 are unable to induce and prime for cell death, cross-linking of coreceptors mediates cell death (64). Thus, SIV binding to the BOB/GPR15 coreceptor can prime PMN to apoptosis, and the extent of interaction between the SIV envelope protein and the coreceptors expressed could be the main process leading to abnormal priming for death of PMN.

The increased PMN susceptibility to apoptosis coincided with the onset of neutropenia in SIV-infected Chinese RMs. PMN redistribution from peripheral blood to sites of inflammation cannot be ruled out, but it is noteworthy that PMN isolated from SIV-infected Chinese RMs at the peak of viral replication displayed defective chemotaxis and were not activated, as reflected by basal normal CD11b expression and basal normal ROS production. This indicates that PMN remain in a resting state during acute SIV infection, in keeping with the undetectable levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. This differs from the chronic asymptomatic phase of HIV infection (18, 19) and of SIV infection in RMs (personal data), where PMN counts are normal despite a greater susceptibility to die by apoptosis (although less than during the acute phase; data not shown). Consistent with the idea that granulopoiesis may compensate PMN losses through apoptosis during the chronic phase, it has been shown that PMN in the bone marrow of chronically SIV-infected macaques are activated (38). Thus, our data showing neutropenia concomitant with higher levels of apoptosis may indicate that granulopoiesis did not compensate for PMN losses. Thus, whether granulopoiesis is defective during the acute phase is, to date, unknown and merits further exploration.

In conclusion, the current set of data demonstrate for the first time increased PMN death early after infection in pathogenic SIV-infected NHP models of AIDS. This accelerated PMN death may contribute to the neutropenia and may play a key role during primary SIV infection. This PMN apoptosis is induced by SIV envelope binding to the BOB/GPR15 chemokine receptor, and the divergent levels of this receptor may be responsible for the differences in PMN apoptosis between pathogenic and nonpathogenic SIV infection models.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jay Rappaport (Temple University) and David Weiner (University of Pennsylvania) for providing blood from Indian RMs. We are also grateful to Prof. A. G. Saimot for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

This work was funded by grants from the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le Sida et les Hépatites Virales, Sidaction, Fondation de France, and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (to J.E.) and in part by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 AI62437 (to P.D.K.). C.E. holds an Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris mobility post-doctoral position. S.F. was supported by a grant from Fonds d’É tudes et de Recherche du Corps Médical des Hôpitaux de Paris.

This work is dedicated to the memory of Bruno Hurtrel.

Abbreviations used in this paper: PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophil; 7-AAD, 7-amino-actinomycin D; AGM, African green monkey; AID50, 50% animal infectious dose; ALLN, N-acetyl-Leu-Leu-Nle; DiOC6, 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide; ΔΨm, mitochondrial transmembrane potential; NHP, nonhuman primate; RM, rhesus macaque; ROS, reactive oxygen species; z-VAD-fmk, N-benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-DL-Asp(Ome)-fluoromethylketone.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Watson A, Ranchalis J, Travis B, McClure J, Sutton W, Johnson PR, Hu SL, Haigwood NL. Plasma viremia in macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasma viral load early in infection predicts survival. J Virol. 1997;71:284–290. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.284-290.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babior BM. Oxidants from phagocytes: agents of defense and destruction. Blood. 1984;64:959–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastian A, Schafer H. Human α-defensin 1 (HNP-1) inhibits adenoviral infection in vitro. Regul Pept. 2001;101:157–161. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujisawa H. Inhibitory role of neutrophils on influenza virus multiplication in the lungs of mice. Microbiol Immunol. 2001;45:679–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2001.tb01302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasin B, Wang W, Pang M, Cheshenko N, Hong T, Waring AJ, Herold BC, Wagar EA, Lehrer RI. θ Defensins protect cells from infection by herpes simplex virus by inhibiting viral adhesion and entry. J Virol. 2004;78:5147–5156. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5147-5156.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L, Yu W, He T, Yu J, Caffrey RE, Dalmasso EA, Fu S, Pham T, Mei J, Ho JJ, et al. Contribution of human α-defensin 1, 2, and 3 to the anti-HIV-1 activity of CD8 antiviral factor. Science. 2002;298:995–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.1076185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Z, Cicchi F, Gentles D, Ericksen B, Lubkowski J, Devico A, Lehrer RI, Lu W. Human neutrophil α-defensin 4 inhibits HIV-1 infection in vitro. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L, Lopez P, He T, Yu W, Ho DD. Retraction of an interpretation. Science. 2004;303:467. doi: 10.1126/science.303.5657.467b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldwin GC, Fuller D, Roberts RL, Ho DD, Golde DW. Granulocyte- and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factors enhance neutrophil cytotoxicity toward HIV-infected cells. Blood. 1989;74:1673–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scapini P, Lapinet-Vera JA, Gasperini S, Calzetti F, Bazzoni F, Cassatella MA. The neutrophil as a cellular source of chemokines. Immunol Rev. 2000;177:195–203. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.17706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisbergen J, Sanchez-Hernandez M, Geijtenbeek TBH, van Kooyk Y. Neutrophils mediate immune modulation of dendritic cells through glycosylation-dependent interactions between Mac-1 and DC-SIGN. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1281–1292. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colotta F, Re F, Polentarutti N, Sozzani S, Mantovani A. Modulation of granulocyte survival and programmed cell death by cytokines and bacterial products. Blood. 1992;80:2012–2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray J, Barbara JA, Dunkley SA, Lopez AF, Van Ostade X, Condliffe I, Dransfield AM, Haslett C, Chilvers ER. Regulation of neutrophil apoptosis by tumor necrosis factor-α: requirement for TNFR55 and TNFR75 for induction of apoptosis in vitro. Blood. 1997;90:2772–2783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.François S, El Benna J, Dang PMC, Pedruzzi E, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Elbim C. Inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis by Toll-like receptor agonists in whole blood: involvement of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt and NF-κB signaling pathways leading to increased levels of Mcl-1, A1 and phosphorylated Bad. J Immunol. 2005;174:3633–3642. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards SW, Hallett MB. Seeing the wood for the trees: the forgotten role of neutrophils in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Today. 1997;18:320–324. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aleman M, Schierloh P, de la Barrera SS, Musella RM, Saab MA, Baldini M, Abbate E, Sasiain MC. Mycobacterium tuberculosis triggers apoptosis in peripheral neutrophils involving Toll-like receptor 2 and p38 mitogen protein kinase in tuberculosis patients. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5150–5158. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5150-5158.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramirez MJ, Titos E, Claria J, Navasa M, Fernandez J, Rodes J. Increased apoptosis dependent on caspase-3 activity in polymorphonuclear leukocytes from patients with cirrhosis and ascites. J Hepatol. 2004;41:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitrak DL, Tsai HC, Mullane KM, Sutton SH, Stevens P. Accelerated neutrophil apoptosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2714–2719. doi: 10.1172/JCI119096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldelli F, Preziosi R, Francisci D, Tascini C, Bistoni F, Nicoletti I. Programmed granulocyte neutrophil death in patients at different stages of HIV infection. AIDS. 2000;214:1067–1069. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200005260-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salmen S, Teran G, Borges L, Goncalves L, Albarran B, Urdaneta H, Montes H, Berrueta L. Increased Fas-mediated apoptosis in polymorphonuclear cells from HIV-infected patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;137:166–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broussard SR, Staprans SI, White R, Whitehead EM, Feinberg MB, Allan JS. Simian immunodeficiency virus replicates to high levels in naturally infected African green monkeys without inducing immunologic or neurologic disease. J Virol. 2001;75:2262–2275. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2262-2275.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diop OM, Gueye A, Dias-Tavares M, Kornfeld C, Faye A, Ave P, Huerre M, Corbet S, Barre-Sinoussi F, Muller-Trutwin MC. High levels of viral replication during primary simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm infection are rapidly and strongly controlled in African green monkeys. J Virol. 2000;74:7538–7547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7538-7547.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Estaquier J, Monceaux V, Cumont MC, Aubertin AM, Hurtrel B, Ameisen JC. Early changes in peripheral blood T cells during primary infection of rhesus macaques with a pathogenic SIV. J Med Primatol. 2000;29:127–135. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0684.2000.290305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holzammer S, Holznagel E, Kaul A, Kurth R, Norley S. High virus loads in naturally and experimentally SIVagm-infected African green monkeys. Virology. 2001;283:324–331. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaur A, Grant RM, Means RE, McClure H, Feinberg M, Johnson RP. Diverse host responses and outcomes following simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 infection in sooty mangabeys and rhesus macaques. J Virol. 1998;72:9597–9611. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9597-9611.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kornfeld C, Ploquin MJ, Pandrea I, Faye A, Onanga R, Apetrei C, Poaty-Mavoungou V, Rouquet P, Estaquier J, Mortara L, et al. Anti-inflammatory profiles during primary SIV infection in African green monkeys are associated with protection against AIDS. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1082–1091. doi: 10.1172/JCI23006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandrea I, Apetrei C, Dufour J, Dillon N, Barbercheck J, Metzger M, Jacquelin B, Bohm R, Marx PA, Barre-Sinoussi F, et al. Simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm.sab infection of Caribbean African green monkeys: a new model for the study of SIV pathogenesis in natural hosts. J Virol. 2006;80:4858–4867. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.4858-4867.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silvestri G, Fedanov A, Germon S, Kozyr N, Kaiser WJ, Garber DA, McClure H, Feinberg MB, Staprans SI. Divergent host responses during primary simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsm infection of natural sooty mangabey and nonnatural rhesus macaque hosts. J Virol. 2005;79:4043–4054. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4043-4054.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cumont MC, Diop O, Vaslin B, Elbim C, Viollet L, Monceaux V, Lay S, Silvestri G, Le Grand R, Müller-Trutwin M, et al. Early divergence in lymphoid tissue apoptosis between pathogenic and nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infections of nonhuman primates. J Virol. 2008;82:1175–1178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00450-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyaard L, Otto SA, Jonker RR, Mijnster MJ, Keet RP, Miedema F. Programmed death of T cells in HIV-1 infection. Science. 1992;257:217–219. doi: 10.1126/science.1352911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Estaquier J, Idziorek T, de Bels F, Barre-Sinoussi F, Hurtrel B, Aubertin AM, Venet A, Mehtali M, Muchmore E, Michel P, et al. Programmed cell death and AIDS: significance of T-cell apoptosis in pathogenic and nonpathogenic primate lentiviral infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9431–9435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Estaquier J, Idziorek T, Zou W, Emilie D, Farber CM, Bourez JM, Ameisen JC. T helper type 1/T helper type 2 cytokines and T cell death: preventive effect of interleukin 12 on activation-induced and CD95 (FAS/APO-1)-mediated apoptosis of CD4+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1759–1767. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Estaquier J, Tanaka M, Suda T, Nagata S, Golstein P, Ameisen JC. Fas-mediated apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons: differential in vitro preventive effect of cytokines and protease antagonists. Blood. 1996;87:4959–4966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsikis PD, Wunderlich ES, Smith CA, Herzenberg LA. Fas antigen stimulation induces marked apoptosis of T lymphocytes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2029–2036. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badley AD, Parato K, Cameron DW, Kravcik S, Phenix BN, Ashby D, Kumar A, Lynch DH, Tschopp J, Angel JB. Dynamic correlation of apoptosis and immune activation during treatment of HIV infection. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:420–432. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCloskey TW, Bakshi S, Than S, Arman P, Pahwa S. Immunophenotypic analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells undergoing in vitro apoptosis after isolation from human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Blood. 1998;92:4230–4237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnoult D, Petit F, Lelievre JD, Lecossier D, Hance A, Monceaux V, Hurtrel B, Ho Tsong Fang R, Ameisen JC, Estaquier J. Caspase-dependent and independent T-cell death pathways in pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infection: relationship to disease progression. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:1240–1252. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silvestri G, Sodora DL, Koup RA, Paiardini M, O’Neil SP, McClure HM, Staprans SI, Feinberg MB. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys is characterized by limited bystander immunopathology despite chronic high-level viremia. Immunity. 2003;18:441–452. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hurtrel B, Petit F, Arnoult D, Muller-Trutwin M, Silvestri G, Estaquier J. Apoptosis in SIV infection. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(Suppl 1):979–990. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C: 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monceaux V, Estaquier J, Février M, Cumont MC, Rivière Y, Aubertin AM, Ameisen JC, Hurtrel B. Extensive apoptosis in lymphoid organs during primary SIV infection predicts rapid progression towards AIDS. AIDS. 2003;17:1585–1596. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200307250-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viollet L, Monceaux V, Petit F, Ho Tsong Fang R, Cumont MC, Hurtrel B, Estaquier J. Death of CD4+ T cells from lymph nodes during primary SIV-mac251 infection predicts the rate of AIDS progression. J Immunol. 2006;177:6685–6694. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cumont MC, Monceaux V, Viollet L, Lay S, Parker R, Hurtrel B, Estaquier J. TGF-β in intestinal lymphoid organs contributes to the death of armed effector CD8 T cells and is associated with the absence of virus containment in rhesus macaques infected with the simian immunodeficiency virus. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1747–1758. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sasakawa Y, Sakuma S, Higashi Y, Sasakawa T, Amaya T, Goto T. FK 506 suppresses neutrophil chemoattractant production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;403:281–288. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monceaux V, Ho Tsong Fang R, Cumont MC, Hurtrel B, Estaquier J. Distinct cycling CD4+ and CD8+ T cell profiles during the asymptomatic phase of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac251 infection in rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2003;77:10047–10059. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.10047-10059.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maianski NA, Maianski AN, Kuijpers TW, Roos D. Apoptosis of neutrophils. Acta Haematol. 2004;111:56–66. doi: 10.1159/000074486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Monceaux V, Viollet L, Petit F, Ho Tsong Fang R, Cumont MC, Zaunders J, Hurtrel B, Estaquier J. CD8+ T cell dynamics during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in macaques: relationship of effector cell differentiation with the extent of viral replication. J Immunol. 2005;174:6898–6908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldstein S, Brown CR, Ourmanov I, Pandrea I, Buckler-White A, Erb C, Nandi JS, Foster GJ, Autissier P, Schmitz JE, Hirsch VM. Comparison of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagmVer replication and CD4+ T-cell dynamics in vervet and sabaeus African green monkeys. J Virol. 2006;80:4868–4877. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.4868-4877.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldstein S, Ourmanov I, Brown CR, Beer BE, Elkins WR, Plishka R, Buckler-White A, Hirsch VM. Wide range of viral load in healthy African green monkeys naturally infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2000;74:11744–11753. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11744-11753.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Staprans SI, Dailey PJ, Rosenthal A, Horton C, Grant RM, Lerche N, Feinberg MB. Simian immunodeficiency virus disease course is predicted by the extent of virus replication during primary infection. J Virol. 1999;73:4829–4839. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4829-4839.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ling B, Veazey RS, Luckay A, Penedo C, Xu K, Lifson JD, Marx PA. SIV(mac) pathogenesis in rhesus macaques of Chinese and Indian origin compared with primary HIV infections in humans. AIDS. 2002;16:1489–1496. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207260-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mothé BR, Weinfurter J, Wang C, Rehrauer W, Wilson N, Allen TM, Allison DB, Watkins DI. Expression of the major histocompatibility complex class I molecule Mamu-A01* is associated with control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J Virol. 2003;77:2736–2740. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2736-2740.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loffredo JT, Maxwell J, Qi Y, Glidden CE, Borchardt GJ, Soma T, Bean AT, Beal DR, Wilson NA, Rehrauer WM, et al. Mamu-*08-positive macaques control simian immunodeficiency virus replication. J Virol. 2007;81:8827–8832. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00895-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elbim C, Prevot MH, Bouscara F, Franzini E, Chollet-Martin S, Hakim J, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA. PMN from HIV-infected patients show enhanced activation, diminished fMLP-induced L-selectin shedding and an impaired oxidative burst after cytokine priming. Blood. 1994;84:2759–2766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kubes P, Heit B, Van Marle G, Johnston JB, Knight D, Khan A, Power C. In vivo impairment of neutrophil recruitment during lentivirus infection. J Immunol. 2003;171:4801–4808. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salamone G, Giordano M, Trevani AS, Gamberale R, Vermeulen M, Schettinni J, Geffner JR. Promotion of neutrophil apoptosis by TNF-α. J Immunol. 2001;166:3476–3483. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dunican AL, Leuenroth SJ, Grutkoski P, Ayala A, Simms HH. TNFα-induced suppression of PMN apoptosis is mediated through interleukin-8 production. Shock. 2000;14:284–289. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu JH, Wei S, Lamy T, Epling-Burnette PK, Starkebaum G, Djeu JY, Loughran TP. Chronic neutropenia mediated by Fas ligand. Blood. 2000;95:3219–3222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Renshauw SA, Parmar JS, Singleton V, Rowe SJ, Dockrell DH, Dower SK, Bingle CD, Chilvers ER, Whyte MK. Acceleration of human neutrophil apoptosis by TRAIL. J Immunol. 2003;170:1027–1033. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Esser MT, Graham DR, Coren LV, Trubey CM, Bess JW, Arthur LO, Ott DE, Lifson JD. Differential incorporation of CD45, CD80 (B7-1), CD86 (B7-2), and major histocompatibility complex class I and II molecules into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions and microvesicles: implications for viral pathogenesis and immune regulation. J Virol. 2001;75:6173–6182. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.6173-6182.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vlahakis SR, Algeciras-Schimnich A, Bou G, Heppelmann CJ, Villasis-Keever A, Collman RC, Paya CV. Chemokine-receptor activation by env determines the mechanism of death in HIV-infected and uninfected T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:207–215. doi: 10.1172/JCI11109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang K, Rana F, Silva C, Ethier J, Wehrly K, Chesebro B, Power C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope-mediated neuronal death: uncoupling of viral replication and neurotoxicity. J Virol. 2003;77:6899–6912. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6899-6912.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lelievre JD, Mammano F, Arnoult D, Petit F, Grodet A, Estaquier J. A novel mechanism for HIV1-mediated bystander CD4+ T-cell death: neighboring dying cells drive the capacity of HIV1 to kill noncycling primary CD4+ T cells. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:1017–1027. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petit F, Corbeil J, Lelievre JD, Parseval LM, Pinon G, Green DR, Ameisen JC, Estaquier J. Role of CD95-activated caspase-1 processing of IL-1β in TCR-mediated proliferation of HIV-infected CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2004;31:3513–3524. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200112)31:12<3513::aid-immu3513>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kottilil S, Shin K, Jackson JO, Reinato KN, O’Shea MA, Yang J, Hallahan CW, Lempicki R, Arthos J, Fauci AS. Innate immune dysfunction in HIV infection: effect of HIV envelope-NK cell interactions. J Immunol. 2006;176:1107–1114. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marx PA, Chen Z. The function of simian chemokine receptors in the replication of SIV. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:215–223. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deng HK, Unutmaz D, Kewal-Ramani VN, Littman DR. Expression cloning of new receptors used by simian and human immunodeficiency viruses. Nature. 1997;1388:296–300. doi: 10.1038/40894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Farzan M, Choe H, Martin K, Marcon L, Hofmann W, Karlsson G, Sun Y, Barrett P, Marchand N, Sullivan N, et al. Two orphan seven-transmembrane segment receptors which are expressed in CD4-positive cells support simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Exp Med. 1997;186:405–411. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Levine AM, Karim R, Mack W, Gravink DJ, Anastos K, Young M, Cohen M, Newman M, Augenbraun M, Gange S, Watts DH. Neutropenia in human immunodeficiency virus infection: data from the women’s interagency HIV study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:405–410. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salmen S, Guillermo C, Colmenares M, Barboza L, Goncalves L, Teran G, Alfonso N, Montes H, Berreta L. Role of human immunodeficiency virus in leukocytes apoptosis from infected patients. Invest Clin. 2005;46:289–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yant LJ, Friedrich TC, Johnson RC, May GE, Maness NJ, Enz AM, Lifson JD, O’Connor DH, Carrington M, Watkins DI. The high-frequency major histocompatibility complex class I allele Mamu-B*17 is associated with control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J Virol. 2006;80:5074–5077. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.5074-5077.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wojcechowskyj JA, Yant LJ, Wiseman RW, O’Connor SL, O’Connor DH. Control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 is not predicted by inheritance of Mamu-B*17-containing haplotypes. J Virol. 2007;81:406–410. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01636-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Michallet MC, Saltel F, Flacher M, Revillard JP, Genestier L. Cathepsin-dependent apoptosis triggered by supraoptimal activation of T lymphocytes: a possible mechanism of high dose tolerance. J Immunol. 2004;172:5405–5414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chipuk JE, Green DR. Do inducers of apoptosis trigger caspase-independent cell death? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:268–275. doi: 10.1038/nrm1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Von Gunten S, Yousefi S, Seitz M, Jakob SM, Schaffner T, Seger R, Takala J, Villiger PM, Simon HU. Siglec-9 transduces apoptotic and nonapoptotic death signals into neutrophils depending on the proinflammatory cytokine environment. Blood. 2005;106:1423–1431. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Knepper-Nicolai B, Savill J, Brown SB. Constitutive apoptosis in human neutrophils requires synergy between calpains and the proteasome downstream of caspases. J Biol Chem. 1998;46:30530–30536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yousefi S, Perozzo R, Schmid I, Ziemiecki A, Schaffner T, Scapozza L, Brunner T, Simon HU. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1124–1132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lichtner M, Mengoni F, Mastroianni CM, Sauzullo I, Rossi R, De Nicola M, Vullo V, Ghibelli L. HIV protease inhibitor therapy reverses neutrophil apoptosis in AIDS patients by direct calpain inhibition. Apoptosis. 2006;11:781–787. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-5699-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Olinger GG, Saifuddin M, Spear GT. CD4-negative cells bind human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and efficiently transfer virus to T cells. J Virol. 2000;74:8550–8557. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8550-8557.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gabali AM, Anzinger JJ, Spear GT, Thomas LL. Activation by inflammatory stimuli increases neutrophil binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and subsequent infection of lymphocytes. J Virol. 2004;78:10833–10836. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10833-10836.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]