Abstract

Hepcidin is a peptide hormone that is secreted by the liver and controls body iron homeostasis. Hepcidin overproduction causes anemia of inflammation, whereas its deficiency leads to hemochromatosis. Inflammation and iron are known extracellular stimuli for hepcidin expression. We found that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress also induces hepcidin expression and causes hypoferremia and spleen iron sequestration in mice. CREBH (cyclic AMP response element–binding protein H), an ER stress–activated transcription factor, binds to and transactivates the hepcidin promoter. Hepcidin induction in response to exogenously administered toxins or accumulation of unfolded protein in the ER is defective in CREBH knockout mice, indicating a role for CREBH in ER stress–regulated hepcidin expression. The regulation of hepcidin by ER stress links the intracellular response involved in protein quality control to innate immunity and iron homeostasis.

The iron-regulatory hormone hepcidin, a defensin-like peptide produced by the hepatocytes in response to iron and inflammation, is a central humoral mediator of innate immunity and host defense (1). The primary anti-microbial strategy of this circulating peptide may be that of limiting vital iron that is needed by invading microorganisms, thus contributing to host defense. Hepcidin accomplishes this task by triggering degradation of the iron exporter ferroportin, thereby limiting iron egress from enterocytes and macrophages (2). If perpetuated, hepcidin stimulation may lead to the anemia of chronic diseases that is seen during infection, malignancy, and chronic inflammation (3). Thus, hepcidin qualifies as an acute-phase protein and an important component of the innate immune response.

Recently, the acute inflammatory response has been linked to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, a state that is associated with disruption of ER homeostasis and accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER. CREBH, an ER stress–associated liver-specific transcription factor, responds to the immune response–inducing factors lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) and directly activates the transcription of acute-phase response genes, such as serum amyloid P component (SAP) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in the liver (4). Both LPS and IL-6 are also potent inducers of hepcidin in the liver (5, 6). Based on these premises, we wondered whether hepcidin, the iron hormone, is controlled by ER stress and investigated the contribution of CREBH to this activity.

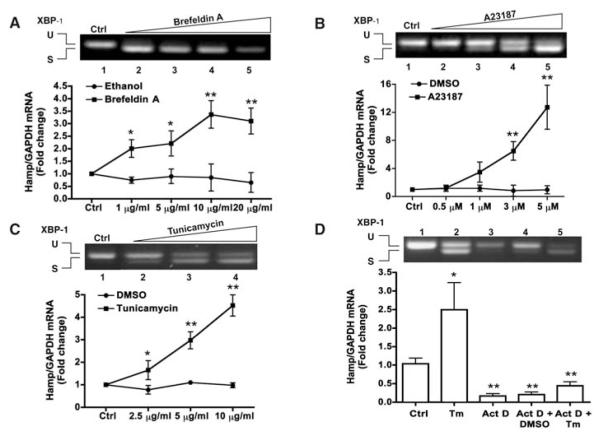

We first tested three known ER stressors in the HepG2 hepatoma cell line: brefeldin A, the A23187 ionophore, and tunicamycin (Tm) (7). As expected, all tested compounds induced ER stress, as shown by the appearance of the spliced form of XBP1, an indicator of ER stress (8) (Fig. 1). Under such circumstances, the expression of hepcidin mRNA was markedly induced, particularly by Tm and A23187 (Fig. 1, A to C). Actinomycin D completely prevented Tm-induced hepcidin mRNA stimulation, indicating that hepcidin response to ER stress is due to transcriptional activation (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

ER stress induces hepcidin gene expression in vitro. (A to C) HepG2 cells were treated with different ER stressors, as indicated. RNA was extracted and subjected to semiquantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for unspliced (U, 442 bp) or spliced (S, 416 bp) XBP1 mRNA forms (shown in the upper panel by ethidium bromide stain) or to quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) for hepcidin mRNA (HAMP) (shown in the lower graph). Data are the mean ± SD of three independent triplicate experiments with mean control values set to 1.0 (*P < 0.01; **P < 0.001). (D) HepG2 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of actinomycin D (Act D, 1 μg/ml) and tunicamycin (Tm, 10 μg/ml). RNA was extracted and processed as above. Data are presented and analyzed as above (*P < 0.03; **P < 0.005).

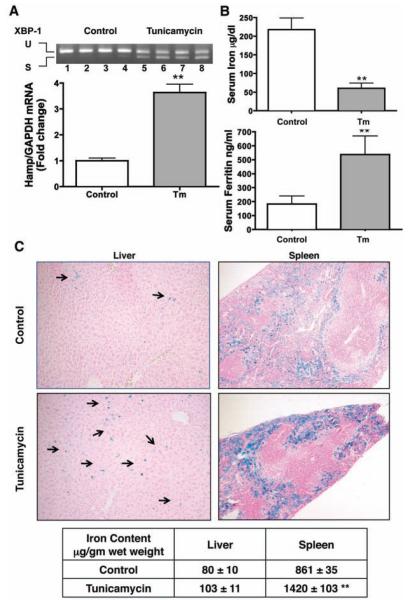

To confirm the in vitro data, we performed further experiments in mice treated with Tm and found that ER stress readily induces hepatic hepcidin gene expression in vivo (Fig. 2A). In agreement with the hepcidin model of iron regulation, Tm-treated mice presented with hypoferremia (Fig. 2B) and iron sequestration in macrophages, mostly evident in the spleen (Fig. 2C). This was accompanied with lower hepatic and spleen ferroportin expression (fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

ER stress induces hepcidin gene expression and perturbs iron homeostasis in vivo. 129S6/SvEvTac wild-type mice were treated with Tm or dextrose (Control) (7). Two independent experiments were performed with 10 mice per group. Reported data are from one representative experiment. (A) Hepatic XBP1 and HAMP mRNA were analyzed and the data are presented as in Fig. 1 (**P < 0.0002). (B) Serum iron and serum ferritin were measured in control and treated (Tm) animals (7) (**P < 0.0001). (C) Liver and spleen histopathologic pictures: Perls’ Prussian blue stain for iron showing iron accumulation in Kupffer cells (arrows) and splenic macrophages. Lower table: chemical iron assessment (**P < 0.0001).

HFE, a protein required for hepcidin regulation by iron (9) and involved in human hemochromatosis (10), is not required for hepcidin induction by ER stress, because Hfe knockout mice readily up-regulated hepcidin expression in response to Tm challenge (fig. S2).

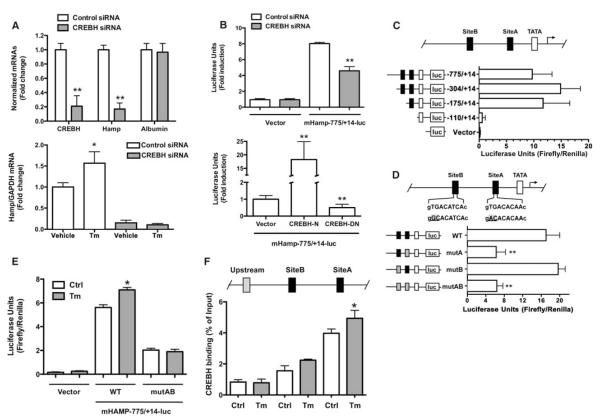

We then investigated the mechanism(s) for transcriptional activation of hepcidin and explored the role of CREBH. CREBH small interfering RNA (siRNA) specifically and markedly down-regulated hepcidin mRNA in HepG2 cells, without affecting expression of liver-specific albumin mRNA (Fig. 3A). Similarly, CREBH siRNA also prevented Tm-stimulated hepcidin mRNA expression (Fig. 3A). The 5′ promoter region of the hepcidin gene (HAMP) has been extensively investigated in other experimental settings (11–17).

Fig. 3.

CREBH is required for hepcidin promoter activity. (A) Upper graph: HepG2 cells were transfected with CREBH-specific siRNA or control siRNA and CREBH, hepcidin, and albumin mRNAs were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Data are the mean ± SD of five independent triplicate experiments with mean control values set to 1.0 (**P < 0.001). Lower graph: HepG2 cells were transfected as above and treated with Tm or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, vehicle). Hepcidin mRNA was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as above (*P < 0.03). (B) Upper graph: HepG2 cells were cotransfected with the pGL3-Basic plasmid (Vector) or the mHAMP-775/+14-luc plasmid and CREBH specific or control siRNA (**P < 0.005). Lower graph: the mHAMP-775/+14-luc plasmid was cotransfected with active (CREBH-N) or dominant negative (CREBH-DN) CREBH plasmids into HepG2 cells. Data are presented and analyzed are as in Fig. 1 (**P < 0.0005). (C) Different hepcidin promoter segments were cloned in the pGL3-Basic plasmid (Vector) and transfected in HepG2 cells. (D) HepG2 cells were transfected with wild-type mHAMP-775/+14-luc (WT) or mutant promoter constructs and luciferase activity assessed (**P<0.005). (E) HepG2 cells transfected with the pGL3-Basic (Vector) or WT or site A and B–mutated mHAMP-775/+14-luc plasmids were treated with either DMSO (Ctrl) or Tm; data are the mean ± SD of five independent experiments (*P < 0.04). (F) Immunoprecipitation of HepG2 chromatin from cells exposed to either DMSO (Ctrl) or Tm was performed with anti-CREBH antibody. Promoter regions (100 to 150 bp) spanning site A, site B, or an upstream control region were amplified, as depicted. Percentage of DNA immunoprecipitated with anti-CREBH antibody relative to input chromatin is shown; data are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05).

The activity of a 789–base pair (bp) HAMP promoter fragment was comparably decreased by cotransfecting HepG2 cells with CREBH siRNA or an expression vector encoding CREBH protein lacking its transactivation domain (Fig. 3B), whereas a vector expressing the CREBH N-terminal active fragment greatly enhanced HAMP promoter activity (Fig. 3B). In 3T3 fibroblastic cells, which lack CREBH, exogenously expressed active CREBH increased HAMP promoter activity by 20-fold, as shown in HepG2 cells (fig. S3). These data indicate that CREBH is key for constitutive and inducible expression of the HAMP promoter in vitro.

The investigated HAMP genomic region displays two conserved putative binding sites for CREBH (fig. S4A). The −175/+14 promoter segment, where site A lies, accounted for most basal luciferase activity in transfected HepG2 cells (Fig. 3C). To further clarify the role of sites A and B in driving HAMP promoter activity, we performed transfection experiments with promoter variants carrying point mutations at the CREBH binding sites A and/or B. HAMP promoter activity decreased by ~60% after mutation of site A and remained unchanged when site B was mutated, whereas simultaneous mutation of both sites did not further decrease promoter activity (Fig. 3D). Accordingly, cotransfection of a CREBH dominant negative expression plasmid impaired luciferase activity of wild-type but not mutant AB promoter fragment (fig. S5), whereas combined site AB mutation blunted Tm-stimulated HAMP promoter activity (Fig. 3E). HepG2 nuclear proteins can specifically bind site A and B (fig. S6, A and B). CREBH binding to these elements (particularly site A) in the endogenous promoter was confirmed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay with a specific anti-CREBH antibody (Fig. 3F). The data indicate the importance of the identified HAMP promoter elements and, particularly, the key role of site A occupancy by CREBH in driving HAMP promoter activity in vitro. However, we consistently observed a greater stimulatory effect of Tm on endogenous HAMP mRNA, suggesting that other regions and factors may be involved in the activation of HAMP promoter reporter in vitro. At least one such factor is X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1).

Basic region leucine zipper (B-ZIP) transcription factors, such as CREBH and XBP1, form either homo- or heterodimers to bind specific DNA sequences and regulate gene transcription (18, 19). In vitro, the increase in hepcidin mRNA in response to different ER stressors was accompanied with the simultaneous appearance of spliced XBP1 mRNA (Fig. 1). Coexpression of mHAMP-775/+14-luc with plasmids expressing the spliced form of XBP1 and the active form of CREBH led to a greater stimulation of basal HAMP promoter activity than CREBH alone (fig. S7).

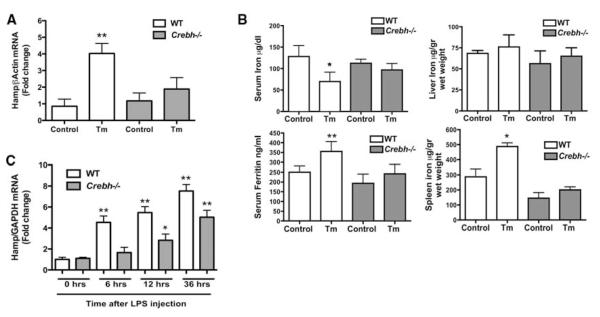

To clarify the role of CREBH in hepcidin expression during ER stress in vivo, we used Crebh−/− mice. Tm treatment led to marked hepcidin activation in wild-type mice, but failed to appreciably induce hepcidin expression or cause iron perturbation, including spleen iron accumulation, in Crebh−/− mice (Fig. 4, A and B). In vivo expression of mutant human FVIII, a protein that inherently misfolds in the ER (20) and elicits a milder form of ER stress than Tm treatment (fig. S8A), also increased hepcidin mRNA in wild-type mice (although to a lesser extent than Tm) but not in Crebh−/− mice (fig. S8B).

Fig. 4.

ER stress induction of hepcidin expression is defective in Crebh−/− mice. (A) WT or Crebh−/− mice were treated with either DMSO (Control) or Tm. Hepatic hepcidin mRNA expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Data are the mean ± SD from one representative experiment (four or five mice per group) of four experiments (**P < 0.0001). Mean control values were set to 1.0. (B) Serum iron, serum ferritin, and tissue iron were measured in control and treated (Tm) animals (four or five mice per group) (7)(*P < 0.02; **P < 0.004). (C) Effect of LPS administration on hepatic hepcidin expression in Crebh−/− mice. Wild-type or Crebh−/−mice (four or five mice per group) were treated with either saline or LPS (2 mg/kg) and killed at different time points, as indicated. Hepatic hepcidin mRNA expression was assessed by qRT-PCR and expressed for each time point as fold increase over the control set to 1. Data are the mean T SD (*P < 0.01; **P < 0.001).

LPS and IL-6 are known stimulators of both CREBH and hepcidin (5, 6). We tested whether CREBH is required for hepcidin response to LPS in vivo by analysis in wild-type and Crebh−/− mice. CREBH deficiency did not impair induction of the hepcidin gene in response to inflammatory challenge, although the increased expression of hepatic hepcidin mRNA was lower in Crebh−/− animals compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 4C). The data suggest that the CREBH-hepcidin axis may cooperate with other well-characterized signaling pathways (such as IL-6/STAT3) to stimulate hepcidin expression during inflammation (fig. S9).

The liver regulates drug detoxification, lipid metabolism, glucose homeostasis, and, as emerged after the discovery of hepcidin, iron homeostasis. As professional secretory cells, the hepatocytes likely face a subtle but persistent condition of ER stress due to the extremely high requirement for protein folding within the ER lumen (21). Homeostasis in the ER is tightly monitored through a series of adaptive programs, called the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR not only regulates protein folding capacity within the ER, but also modulates fundamental physiological processes, such as differentiation of specialized cell types and cell metabolism (22). Here, we show that this adaptive program also influences iron metabolism, through activation of hepcidin, the iron hormone. CREBH stable occupancy of the hepcidin promoter may serve as a “stress sensor” for intracellular or extracellular signals perturbing homeostasis (fig. S9). CREBH may act alone or recruit other stress-related transcription factors, such as XBP1, as shown here. Under conditions of severe ER stress, hepcidin activation and iron withdrawn from the bloodstream may facilitate a general defense mechanism and an innate immune response, in a manner similar to that which occurs during hepcidin activation in response to systemic inflammation (1). Overall, it seems that, at variance with other ER stress–induced factors, CREBH activates the expression of classic acute-phase response genes, such as SAP and CRP (4) and hepcidin (this report), a peptide that also qualifies as a main acute-phase response gene.

The regulation of hepcidin by ER stress links the cellular response involved in protein quality control to innate immunity and iron homeostasis. Apparently, hepcidin “senses” not only extracellular stimuli, such as iron fluctuations, erythroid factors, and cytokines (1), but also stress signals arising intracellularly (fig. S9).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Salsi for assistance with ChIP analyses and V. Zappavigna and D. H. Perlmutter for helpful suggestions. Supported by European Union grant EUROIRON Ct.2006-037296 (A.P.) and NIH grants DK42394, HL52173, and PO1 HL057346 (R.J.K.). R.J.K. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/325/5942/877/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S10

References

References and Notes

- 1.Ganz T. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2006;306:183. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29916-5_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nemeth E, et al. Science. 2004;306:2090. doi: 10.1126/science.1104742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cartwright GE. Semin. Hematol. 1966;3:351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang K, et al. Cell. 2006;124:587. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pigeon C, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:7811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nemeth E, et al. Blood. 2003;101:2461. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 8.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. Cell. 2001;107:881. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muckenthaler M, et al. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:102. doi: 10.1038/ng1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pietrangelo A. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2383. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra031573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courselaud B, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202653200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang RH, et al. Cell Metab. 2005;2:399. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babitt JL, et al. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:531. doi: 10.1038/ng1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wrighting DM, Andrews NC. Blood. 2006;108:3204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falzacappa M. V. Verga, et al. Blood. 2007;109:353. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pietrangelo A, et al. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:294. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flanagan JM, Truksa J, Peng H, Lee P, Beutler E. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2007;38:253. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurst HC. Protein Profile. 1995;2:101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vinson C, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:6321. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6321-6335.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miao HZ, et al. Blood. 2004;103:3412. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu J, Kaufman RJ. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:374. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:739. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.