Abstract

There has been a renewal of interest in interactions of membrane proteins with detergents and lipids, sparked both by recent results that illuminate the structural details of these interactions and also by the realization that some experimental membrane protein structures are distorted by detergent-protein interactions. The integral membrane enzyme diacyglycerol kinase (DAGK) has long been thought to require the presence of lipid as an obligate “cofactor” in order to be catalytically viable in micelles. Here, we report that near-optimal catalytic properties are observed for DAGK in micelles composed of lyso-myristoylphosphatidylcholine (LMPC), with significant activity also being observed in micelles composed of lyso-myristoylphosphatidylglycerol and tetradecylphosphocholine. All three of these detergents were also sustained high stability of the enzyme. NMR measurements revealed significant differences in DAGK-detergent interactions involving LMPC micelles versus micelles composed of dodecylphosphocholine. These results highlight the fact that some integral membrane proteins can maintain native-like properties in lipid-free detergent micelles and also suggest that C14-based detergents may be worthy of more widespread use in studies of membrane proteins.

Solution NMR and X-ray crystallographic structural studies of purified integral membrane proteins are often carried out in detergent micelle solutions, an imperfect medium given that protein-lipid interactions are sometimes both specific and important to integral membrane protein structure and function (4–7). Moreover, it is now clear that some high resolution structures of membrane proteins include micelle-generated distortions (8–11) and also that the energetics of membrane protein folding and intermolecular interactions can be altered in micelles relative to native-like membrane bilayers (12–14). This has led to increased use of lipid-containing mixed micelles, bicelles, nanodiscs, and other model membranes to better-approximate lipid bilayers than detergent-only micelles (15–20). In this paper, we explore the alternative approach of finding improved detergents for sustaining the native-like stability and function of membrane proteins, without resorting to lipid-containing media.

E. coli diacylglycerol kinase (DAGK) is well-suited for studies designed to identify optimal detergents. DAGK is a homotrimeric membrane enzyme with 9 transmembrane helices and three active sites per trimer that catalyzes direct phosphoryl transfer from MgATP to diacylglycerol to produce phosphatidic acid. In pioneering early work, the labs of Kennedy, Bell, and Sandermann showed that DAGK does not exhibit significant catalytic activity in micelles formed by common detergents unless lipid is added (21–25). These early studies suggested that lipids play a cofactor role in support of DAGK catalysis. However, the range of commercially available detergents has dramatically expanded since those studies were carried out. The structure of DAGK was recently determined in DPC micelles using NMR spectroscopy (26), conditions in which DAGK retains considerable catalytic activity, but only at very high substrate concentrations as a consequence of dramatically elevated substrate Km. This latter fact prevents structural studies of DAGK in DPC micelles under conditions in which it is saturated with its substrates or products. Here we re-explore detergent space to see if surfactants are now available that can sustain native-like DAGK structure, stability, and catalysis. It is shown that certain C14 chain detergents are able to do so, with the lyso-phospholipids proving especially effective.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Materials

Detergents and lipids used in this study were purchased from Anatrace (Maumee, OH), Avanti (Alabaster, AL), Sigma (St. Louis, MO), or Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). The diacylglycerols dibutyrylglycerol (DBG) and dihexanoylglycerol (DHG) were synthesized in-house as described previously (3).

Expression and Purification of DAGK

The gene that encodes N-terminal His6-tagged wild type E. coli DAGK was ligated into the pSD005 plasmid (3;27), which was then transformed into E. coli WH1061 cells. WH1061 is a leucine auxotroph strain that does not express endogenous DAGK (28). DAGK was expressed in isotopically labeled form and then purified to the point where it is a pure protein attached to Ni(II)-chelate resin bathed in a buffer containing 1.5% (v/v) Empigen BB detergent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 40 mM HEPES, 300 mM NaCl, and 40 mM imidazole pH 7.5 essentially as described elsewhere(26;29;30). Empigen BB was then exchanged out for the detergent of interest (e.g., LMPC) by passing 10 column volumes of 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing the test detergent through the column. Finally, DAGK was eluted from the column with 250 mM imidazole solution (pH 7.8) containing the same test detergent. The amount of DAGK in the elution fractions was determined spectrophotometrically based on an extinction coefficient of 2.18 (mg/ml)−1 cm−1 at 280 nm.

Measurement of DAGK Activity

The activity assay is derived from protocols that have been described previously (3;31) whereby DAGK-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer from MgATP to DAG is coupled to NADH oxidation by pyruvate kinase (PK) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, Sigma) at 30 °C. The relatively short-chained dibutyrlglycerol (DBG) and dihexanoylglycerol (DHG) were the forms of diacylglycerol used in these studies because of their reasonably high solubility in detergent solutions (3;32). The pH 6.9 activity assay mix was composed of 75 mM PIPES, 50 mM LiCl, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM EDTA 1 mM phosphoenolpyruvate (Sigma), 3 mM MgATP (Sigma), 0.25 mM NADH (Sigma), 12 mM magnesium acetate and 7.8 mM DBG. For the standard mixed micellar assay, this mixture also contained the detergent DM (at 21 mM—19 mM of which is micellar) and the lipid cardiolipin (CL, from beef heart, at 0.66 mM—which corresponds to 3 mol%). For other assays, DM and CL were replaced with the detergent of interest. DAGK stocks were prepared by diluting the purified protein to a concentration 0.15 mg/ml using detergent-containing elution buffer. Aliquots of this stock were added to the activity assay mix that had been equilibrated with PK and LDH (14 units and 20 units, respectively, per ml of mix). The decrease in absorbance at 340 nm resulting from NADH oxidation (as coupled to the DAGK reaction) was monitored spectrophotometrically, with the slope being converted to units of DAGK activity (1 U = 1 micromole of DAG phosphorylated per minute) using the extinction coefficient for NADH of 6110 M−1 cm−1.

Activity data for determination of steady-state kinetic parameters Vmax and Km were collected using the same methods described above, with the exception that in each analysis the concentration of one substrate was varied (0–8 mM MgATP or 0–25 mM DBG) while the other substrate was held constant at a near-saturating level (20 mM for DBG and 3 mM for MgATP). The measured rates were plotted as a function of variable substrate concentrations and fit by the Michaelis-Menten equation (with a Hill coefficient being applied to the variable substrate concentration) using the Solver module in Microsoft Excel.

Thermal Stability of DAGK

Purified DAGK was diluted to a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml using elution buffer plus detergent at either pH 7.8 or pH 6.5. Samples were incubated at 45 and 70 °C, and aliquots were withdrawn at various time points, rapidly frozen in liquid N2, and then stored at −80 °C. Samples were later thawed and subjected to the standard DM/CL/DHG mixed micellar DAGK activity assay to determine the levels of remaining DAGK activity.

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Samples for CD spectroscopy were prepared by removing imidazole from purified DAGK using a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer containing 100 mM sodium chloride, 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.5, and the test detergent of interest. For acquisition of CD spectra, DAGK was diluted using desalting buffer to 50–60 micromolar for near-UV CD spectroscopy or to 10–12 micromolar for far-UV CD spectroscopy.

CD experiments were carried out using a Jasco J-810 instrument equipped with a Peltier temperature control, and the sample were placed in either 1 cm (near-UV) or 0.1 cm (far-UV) path length quartz cuvettes. CD spectra were acquired at 5 °C increments between 20–80 °C, with 1 min of equilibration prior to each acquisition. The far-UV CD spectra were acquired between 190–260 nm with 1 nm bandwidth, while the near-UV spectra were acquired from 250–350 nm with 1 nm bandwidth. Baseline spectra were acquired for the protein-free desalting buffers, and subtracted from the spectra of protein-containing samples. For all acquisitions three spectra were collected and averaged to give the final trace.

The K2D algorithm (http://www.embl.de/~andrade/k2d.html) was used to calculate secondary structure from far-UV CD spectra.

NMR Spectroscopy of DAGK

15N-labeled DAGK was purified using the protocol described above. When the protein was purified into LMPC and DPC, D2O and EDTA were added to 10% and 0.5 mM, respectively, and the sample was concentrated using centrifugal ultrafiltration (Millipore Ultracel, 10 ml, 10kDa cutoff) and the sample was transferred to an NMR tube. For the protein in TDPC and LMPG the pH 7.8 purification buffer containing 250 mM imidazole (pH 7.8) was exchanged for a pH 6.5 10 mM Bis-Tris buffer by repeated centrifugal ultrafiltration/redilution cycles. The completeness of the exchange was monitored by checking the pH of the filtrate. EDTA and D2O were added to all samples to final concentration of 0.5 mM and 10% (v/v). For DAGK in TDPC and LMPG magnesium chloride was also added to 2 mM.

2D 1H,15N-TROSY NMR spectra (33) were acquired at 45°C using a Bruker 800 MHz Avance spectrometer equipped with a triple resonance cryoprobe. The Weigelt version of the TROSY experiment was used(34). Data were processed using NMRPipe/NMRDraw software (35) and analyzed using SPARKY 3 (T.D. Goddard and D. N. Kneller, University of California, San Francisco).

3-D 1H-15N NOESY-TROSY spectra were acquired at 800 MHz and 45°C. 1H-15N NOESY-TROSY spectra were acquired at 800 MHz field. For DAGK dissolved in LMPC micelles, a pulse scheme reported by Zhu et al.(38) was used. The spectrum was acquired with 99 complex points and an acquisition time of 8.87 msec in the indirect 1H dimension, 24 complex points and an acquisition time of 9.25 msec in the 15N dimension, and 1024 complex points and an acquisition time of 91.8 msec in the 1H observe dimension with 24 scans. The mixing time and the delay for relaxation between scans were 150 msec and 1.1 sec, respectively. For DAGK in DPC micelles, a pulse scheme based on the method designed by Schulte-Herbruggen(39) was used. The spectrum was acquired with 99 complex points and an acquisition time of 8.87 msec in the indirect 1H dimension, 24 complex points and an acquisition time of 9.25 msec in the 15N dimension, and 1024 complex points and an acquisition time of 91.8 msec in the 1H observe dimension with 24 scans. The mixing time and the delay for relaxation between scans were 150 msec and 1.1 sec, respectively.

RESULTS

C14-Based Detergents Show Promise for Biochemical Studies of DAGK

While it has been shown that the activity of purified DAGK is generally low in a variety of lipid-free micelles (21;22;25;32;40), some data has suggested that DAGK is more active in longer chain detergents relative to shorter chain detergents (41). We therefore screened for detergents that are able to sustain DAGK’s activity even in the absence of added lipids, with a particular emphasis on detergents that are lipid-like in terms of having relatively long C14 alkyl chains. Detergents tested included nonionic, ionic, zwitterionic, lyso-phospholipids, and sterol-based detergents, each of which was first verified not to hinder the DAGK assay reaction coupling system. These assays were initially carried out by adding small aliquots of DAGK stock solutions prepared in DM micelles (to far below the DM’s CMC) into assay mixtures containing the test detergent at concentrations well above the same detergent’s CMC. Results for this screen are given in Table 1. DM/CL detergent/lipid mixed micelles that are known to sustain native-like DAGK activity (3) were used as a positive control for this screen. It was observed that when solubilized in the C14-based TDPC and lyso-phospholipids (LMPG and LMPC), DAGK exhibited activity that matched or exceeded its DM/CL control activity, whereas in all other cases the activity was much lower reflecting either a very low Vmax for catalysis and/or of grossly elevated substrate Km. The C14 chain detergents ASB-14 and Z3–14 failed to support catalysis, indicated that having a C14 chain is not the only factor that determines detergent efficacy.

Table 1.

Activity levels of DAGK assayed in various detergent conditions

| Detergent | Detergent Class |

Concentration (% w/v) |

DAGK activity when small aliquots of DM/DAGK stock solutions were used to initiate assay. (U/mg) |

DAGK activity when assays were initiated with DAGK stocks in the same detergent as used in assay. (U/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLPC | lyso-PC | 0.5 | ND | 18 ± 6 |

| LMPC | lyso-PC | 0.2 | 66 | 83 ± 7 |

| LPPC | lyso-PC | 0.2 | ND | 44 ± 2 |

| LMPG | lyso-PG | 0.2 | 22 | 19 ± 3 |

| LPPG | lyso-PG | 0.2 | ND | 6.6 ± 5 |

| DPC | alkylphosphocholine | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| TDPC | alkylphosphocholine | 0.2 | 28 | 10 ± 1 |

| CYF7 | alkylphosphocholine | 0.5 | ~0 | ND |

| Z3–14 | zwitterionic | 0.2 | ~0 | ND |

| ASB-14 | zwitterionic | 0.2 | 0.6 | ND |

| LS | anionic | 2.0 | ~0 | ND |

| DTAB | cationic | 0.5 | ~0 | ND |

| DM | non-ionic | 0.5 | 0.3 | ND |

| GRA | saponin | 2.0 | ~0 | ND |

| DM/CLb | mixed micelles | 16 | ND | |

| DMPCc | lipid vesicles | 63 | ND | |

| POPCc | lipid vesicles | 52 | ND |

ND: not determined

While the activity of DAGK in DM/CL (ideal mixed micelles for DAGK) can reach 100 U/mg when saturating DHG is used as the lipid (diacylglycerol) substrate, the conditions used for obtaining the data of this table involved the use of DBG as the lipid substrate at a concentration that is sub-saturating even for DAGK in DM/CL. This was to avoid problems with solubility and stability for some detergents and assay components that can result from the high concentrations of diacylglycerol. Thus, the observed <100 U/mg activity under DM/CL conditions reflects the fact that DAGK is not saturated with its DAG substrate under these conditions.

From reference (3).

The fact that TDPC, LMPC, and LMPG support considerable DAGK activity depends in part on their C14 chains. Activities were measured for DAGK prepared in the corresponding C12- and C16-based compounds as summarized in the final column of Table 1. For these tests, DAGK was directly purified into each of the detergents and then assayed in a mixture containing the same detergent. For all three classes of detergents, the C14 compound yields the highest activity within each class, with the lyso-PC compounds exhibiting higher activities than the corresponding alkyl-PC or lyso-PG compounds. Together these data suggest that significant DAGK activity can be supported by detergents that have both C14 chains and suitable headgroups.

LMPC Micelles Yielded the Most Favorable Steady-State Kinetic Parameters

We determined Vmax and Km for DAGK and its substrates diacylglycerol and MgATP in LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC. Rates were measured at varying concentrations of one substrate while the other substrate was maintained at a near-saturating concentration. The C4-chain DBG was used as the diacylglycerol substrate because it can be employed at high (saturating) concentrations unlike longer-chain forms of DAG, which tend to either form oil droplets or to induce precipitation of assay components before saturating concentrations can be reached.

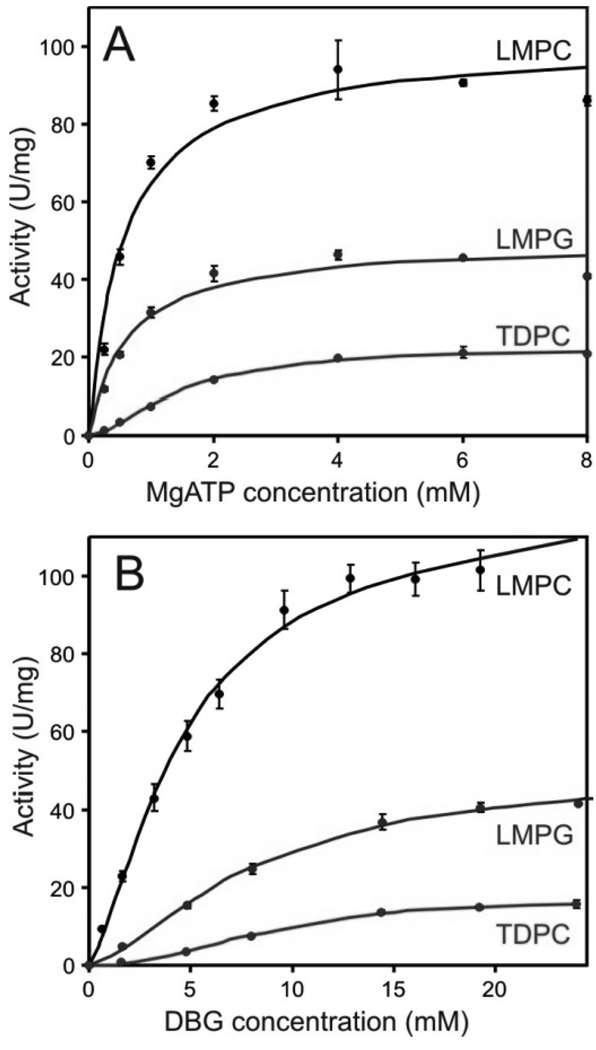

Figure 1 shows the kinetic data for DAGK in LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC micelles. In each case, the data is slightly sigmoidal, exhibiting a lag phase at low substrate concentrations suggesting deviation of DAGK from ideal Michaelis-Menten behavior. The origin of this phenomenon could be related to the fact that DAGK is homotrimeric, with each of its 3 active sites being shared between subunits, although this is not the only possible explanation. Because of this apparent cooperativity, we applied a Hill coefficient to fit the Michaelis-Menten equation to the data, with results given in Table 2. For both substrates, the Hill coefficients determined in all cases indicate positive cooperativity. For LMPG and LMPC the Vmax determined when MgATP was varied (at fixed DBG concentration) was slightly less than when the concentration of DBG was varied (with fixed MgATP). This reflects the fact that the fixed concentration of MgATP was closer to saturation than was fixed DBG. This was not the case for TDPC because Km for MgATP is elevated 3-fold in that detergent.

Figure 1.

Steady-state kinetic analysis of DAGK in TDPC, LMPG, and TDPC at pH 6.5 and 30 °C. The steady-state kinetic data in LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC were collected by measuring DAGK activity (A) over a range of MgATP concentrations (0–8 mM) while keeping the concentration of DBG at a near-saturating concentration (20 mM) or (B) over a range of DBG concentrations (0–25 mM) while keeping the MgATP concentrations constant at a near saturating concentration (3 mM). Each data point is the average of three measurements, and the resulting curves represent best fits by a modified form of the Michaelis-Menten equation in which a Hill coefficient was applied to the variable substrate concentration.

Table 2.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for DAGK catalysis in various detergents.

| DBG varied | MgATP varied | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detergent | Vmax,DBG (U/mg) |

Km,DBG (mM) |

HillDBG | Vmax,ATP (U/mg) |

Km,ATP (mM) |

HillATP |

| LMPC | 119 ± 6 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 1.4 | 91 ± 5 | 0.5 ± 0.02 | 1.8 |

| LMPG | 50 ± 3 | 7.9 ± 0.4 | 1.6 | 46 ± 3 | 0.5 ± 0.02 | 1.5 |

| TDPC | 17 ± 1 | 8.8 ± 0.4 | 2.4 | 23 ± 2 | 1.4 ± 0.07 | 1.7 |

| DM/CLa | ND | ND | ND | >61 ± 8a | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.0 |

From (40). This data was collected at fixed DBG = 10 mM, which most likely was not saturating. Therefore this Vmax be regarded as a lower limit to the true Vmax when both substrate concentrations are saturating.

The kinetic parameters of Table 2 confirm that DAGK is most efficient in LMPC micelles. The values for the apparent Vmax and Km are comparable to those observed for DAGK under ideal mixed micellar conditions (27;31;42), which are similar to those seen for DAGK in vesicles(3;43;44). DAGK’s catalytic properties in both LMPG and TDPC are less ideal than in LMPC, but are still impressive.

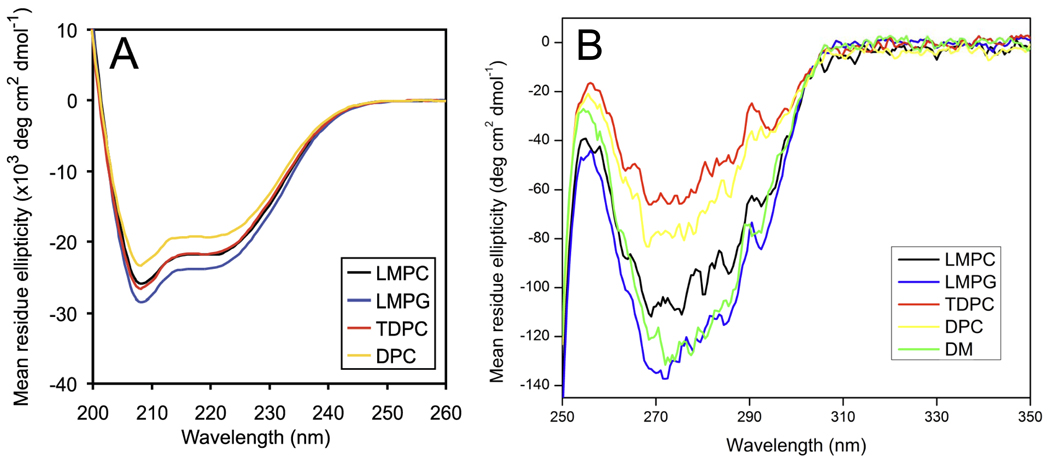

Circular Dichroism of DAGK in LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC micelles

The secondary structure and aromatic side chain order of DAGK in LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC was probed using far- and near-UV CD spectroscopy, respectively. Data was collected at 45 °C and pH 6.5, the conditions used for NMR-based structural determination of DAGK (26). The far-UV CD spectra of DAGK in LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC show the strong negative bands at 208 and 222 nm characteristic of alpha-helical proteins and are very similar to the spectrum of DAGK in DPC (Figure 2A). From these spectra the percent alpha-helical content of DAGK in each of these detergents was calculated to be 79% (LMPC), 83% (LMPG), 79% (TDPC), and 69% (DPC). These values are all close to or within error of the 78% alpha-helicity observed in the NMR-determined structure of DAGK(26).

Figure 2.

CD spectra of DAGK in micelles at pH 6.5 and 45 °C. Far-UV (A) and near-UV (B) CD spectra of DAGK were collected to assess the secondary structure and aromatic side chain order of DAGK, respectively, in LMPC (black), LMPG (blue), and TDPC (red). For comparison, spectra of DAGK in DPC are also included (yellow), as well as for DM (near-UV only, green). Analysis of this far-UV data led to the following estimates of secondary structure. LMPC: 79 ± 9% α-helix, 0% β-sheet, 21 ± 4% random coil; LMPG: 83 ± 8% α-helix, 0% β-sheet, 17 ± 4% random coil; TDPC: 79 ± 8% α-helix, 0% β-sheet, 20 ± 4% random coil; DPC: 69 ± 7% α-helix, 4 ± 1%, β-sheet, 27 ± 4% random coil.

Near-UV CD spectroscopy provides information on the degree of structural order of aromatic side chains (45). It has previously been shown that when DAGK is unfolded, it exhibits no near-UV CD signal (46). As indicated in Figure 2B and in previous work (46), near-UV CD spectra of folded DAGK exhibit negative intensities indicating significant side chain order for at least some of its 5 Trp, 3 Phe, and 2 Tyr residues. Since most of DAGK’s aromatic residues are believed to be located at or near the water-micelle interface rather than being either deeply buried or fully water-exposed, the near-UV CD spectra mostly report on side chain structural order at or near the water-micelle interface.

While the shapes of the spectra in Figure 2B are similar from detergent to detergent, the intensities vary dramatically, being much more intense for DAGK in lysophospholipids than in the alkylphosphocholine detergents. A reasonable interpretation of the data of Figure 2B is that the aromatic side chains of DAGK in the alkylphosphocholines generally exhibit a lower degree of structural order than in lyso-phospholipids, an observation that correlates with the relatively high activities observed for DAGK in the latter class of detergents. However, this correlation only holds within the structurally similar alkylphosphocholine and lyso-phospholipid series, as DAGK’s spectrum in DM is similar in intensity to that in LMPC, even though DAGK’s activity is DM is low (<1 U/mg).

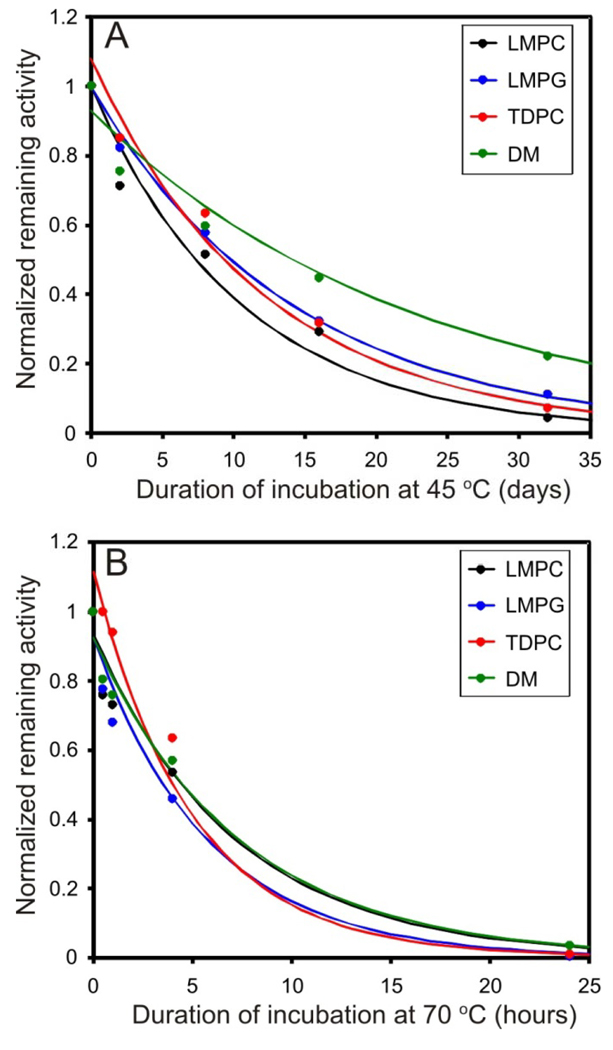

Thermal Stability of DAGK in LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC Micelles

Wild type DAGK’s thermal stability was assessed by measuring its half-life for irreversible inactivation at elevated temperatures, a process previously examined in detail by Bowie and coworkers (27;42;47). Samples at pH 6.5 and 7.8 were incubated at 45 °C and at 70 °C. The data of Figure 3 led to the reported time1/2 for activity loss presented in Table 3, which show that DAGK is much more stable at pH 6.5 than at pH 7.8.

Figure 3.

Irreversible loss of DAGK enzymatic activity with time during incubation at elevated temperatures. The stabilities of DAGK in LMPC (black), LMPG (blue), TDPC (red), and DM (green) were examined. The samples were prepared at pH 6.5 and incubated at either 45 °C (A) or 70 °C (B). Time point aliquots were removed and subjected to the standard DM/CL/DHG DAGK assay at 30 °C. The resulting data points were fit using Solver in Microsoft Excel to obtain the half-life for retention of DAGK.

Table 3.

Thermal stability of DAGK in different micelles.

| Time1/2 for irreversible loss of DAGK activity. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detergent | pH 7.8 | pH 6.5 | ||

| 45 °C (days) |

70 °C (hours) |

45 °C (days) |

70 °C (hours) |

|

| LMPC | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.3 |

| LMPG | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 9.8 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| TDPC | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.02 | 10.1 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.3 |

| DM | 7.7 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.04 | 12.6 ± 0.7 | 5.1 ± 0.3 |

DM micelles have been reported to maintain DAGK in a highly stable state (27;48) even though the enzyme exhibits only very low activity in this detergent. At pH 6.5 DAGK’s stability in LMPG, LMPC, and TDPC is comparable to its stability in DM, with time1/2 ranging from several hours at 70 °C to 8–13 days at 45 °C (Table 3). That the enzyme is not significantly more resistant to heat inactivation in the new detergent systems than in DM despite being more active in the new systems shows that there is no correlation within this set of detergents between DAGK activity and stability.

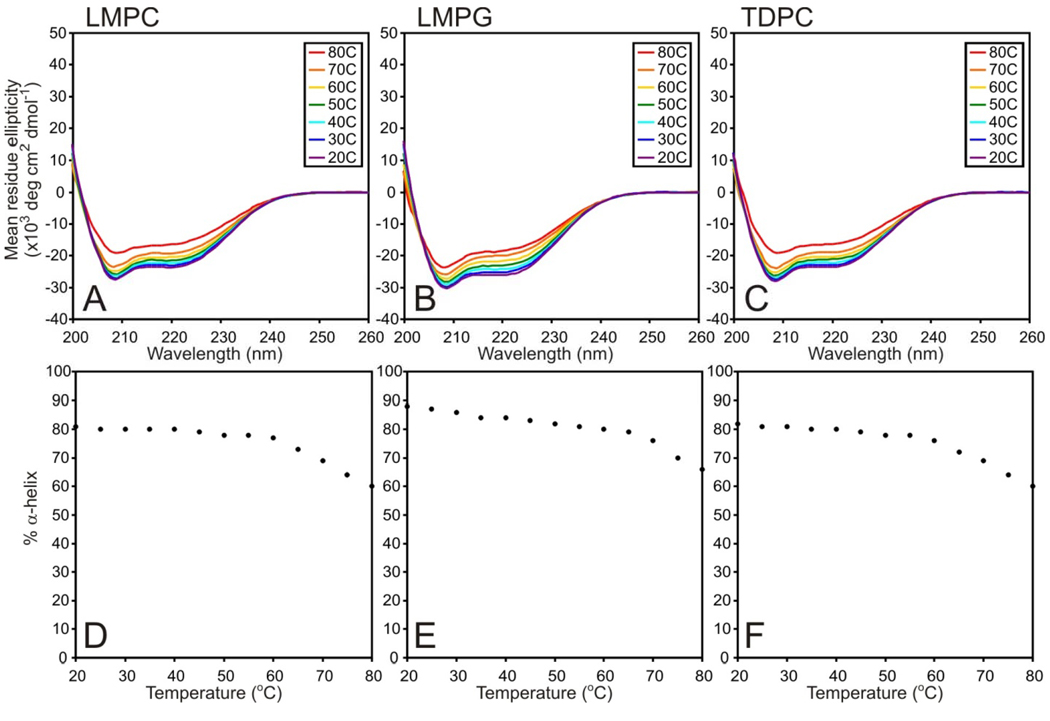

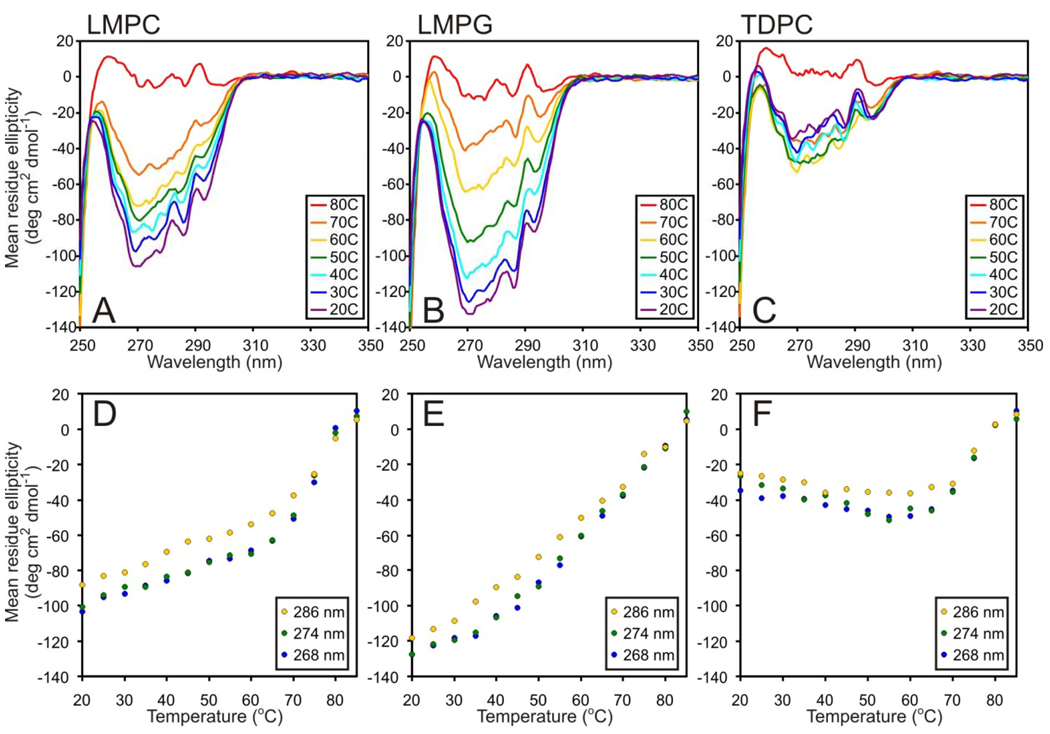

The temperature dependency of DAGK’s far-UV CD spectra is shown in Figure 4, where only a minor loss of helicity is observed for LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC as the temperature is raised from 20 to 60°C. Only above 60°C does the helicity begin to drop steeply. In each case, when the temperature reaches 80 °C, DAGK has lost 18–23% of its alpha-helical content (Table 4). Most likely, this loss is due to melting of the N-terminal amphipathic helix, which encompasses about 20% of DAGK’s helical content at 45°C (26).

Figure 4.

Assessment of helix stability in DAGK by monitoring the temperature dependence of the far-UV CD spectrum of DAGK in LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC micelles at pH 6.5.

Table 4.

Percent alpha-helix of DAGK at pH 6.5 determined from far-UV CD spectra acquired successively at 20 °C, 80 °C, and after return to 20 °C

| Detergents | 20 °C | 80 °C | 20 °C (after heating) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LMPC | 81± 8 | 60 ± 6 | 74 ± 7 |

| LMPG | 88 ± 8 | 66 ± 6 | 85 ± 9 |

| TDPC | 82 ± 8 | 59 ± 7 | 72 ± 7 |

For LMPC and TDPC the loss of helicity observed in DAGK upon elevating the temperature to 80 °C was partially reversible, whereas in the case of LMPG reversibility is nearly complete (Table 4) although this detergent was not superior to the others in protecting against thermal inactivation (Table 3).

Near-UV CD spectra were also acquired as a function of temperature, which provides insight into aromatic side chain order (Figure 5). In the case of TDPC the data resembles the corresponding far-UV CD data in that there is little change until ca. 60 °C, above which signal intensity is steeply reduced until it reaches baseline near 80 °C. For LMPG and LMPC there are significant reductions in the far-UV CD signal intensity as the temperature is raised, with baseline in both cases being reached by 80 °C. However, for the LMPC case reductions in signal intensity become much steeper when 60°C is exceeded. We speculate that DAGK in lyso-phospholipids below 60 °C possesses a class of side chain conformational order that is absent in TDPC even at low temperatures, which may be related to the lower catalytic activity of DAGK observed in TDPC relative to the lyso-phospholipids. At 60 °C, DAGK has lost this class of side chain order in all three detergents tested, but still retains a second class of side chain order. For all three detergents this remaining side chain order is lost by the point 80 °C is reached, which likely corresponds with complete loss of stable tertiary structure.

Figure 5.

Use of near-UV CD to assess aromatic side chain order in DAGK as a function of temperature at pH 6.5. The ellipticity values at 268, 274, and 286 nm correspond to absorbance maxima for phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan side chains, respectively,

Unlike the case for the far-UV CD data, we found that returning the temperature to 20 °C in no case allowed DAGK to recapitulate its original near-UV CD spectrum (data not shown), indicating that the loss of tertiary structural order is not reversible. This is consistent with the previous observations of Bowie and co-workers (47).

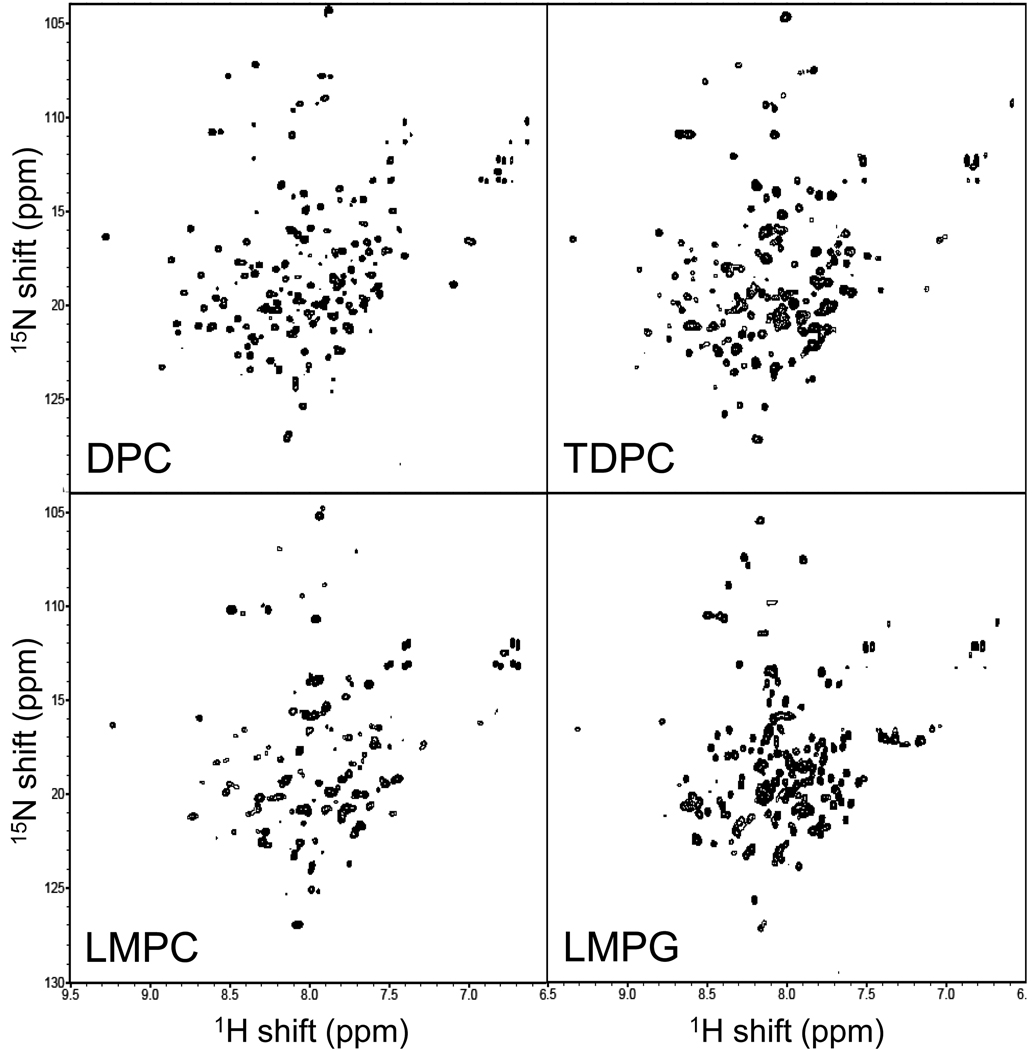

TROSY NMR Spectra of DAGK in LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC Micelles

15N-TROSY-HSQC spectra were acquired at 45 °C for pH 6.5 samples of WT DAGK in LMPC, LMPG, TDPC, and DPC micelles (Figure 6). Overall, the spectra are generally similar and exhibit the modest spectral dispersion that is usually associated with helical membrane proteins. However, while the quality of the spectra in LMPG and TDPC is high (approaching that observed in DPC) the LMPC spectrum exhibits fewer peaks. This is not because there are many missing peaks; rather, it is because at the peak plotting level used (which is comparable for all 4 spectra) many LMPC peaks are broadened to the point where their maxima fall below the plotting level threshold. There are several possible sources for the linebroadening. One possibility is that DAGK-LMPC mixed micelles are larger than the corresponding DAGK-TDPC and DAGK-LMPG micelles. Another possible contribution to line broadening is the presence of internal conformational motions for DAGK in LMPC micelles that are intermediate on the NMR time scale, leading to exchange broadening. A final possible contributing factor is conformational microheterogeneity that results in many similar but non-identical/non-exchanging superimposed peaks. Additional experiments would be required to determine which of the above phenomena are the actual contributing factors.

Figure 6.

800 MHz 15N-TROSY spectra of DAGK in LMPC, LMPG, DPC, and TDPC micelles at 45 °C. The samples in TDPC and LMPG contained 10 mM Bis-Tris, 2 mM magnesium chloride, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 10% (v/v) D2O, pH 6.5. The samples in DPC and LMPC contained 250 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 10% (v/v) D2O, pH 6.5.

The quality of the DAGK spectra from TDPC and LMPG is excellent for a 40 kDa homotrimeric multispan membrane protein as part of a much larger micellar complex. The average line-width of the peaks seen in each of these detergents is 25 Hz. The TDPC and LMPG spectra are similar but are also sufficiently different from each other and from the assigned DPC spectrum such that the assignments that are available for the DPC peaks (30) cannot in many cases be reliably extrapolated to the TDPC and LMPG cases. The differences in specific peak positions may be explained by the fact that the detergent/DAGK interface is quite extensive, such that variations in the covalent structure of each detergent result in modest but widespread changes in resonance position.

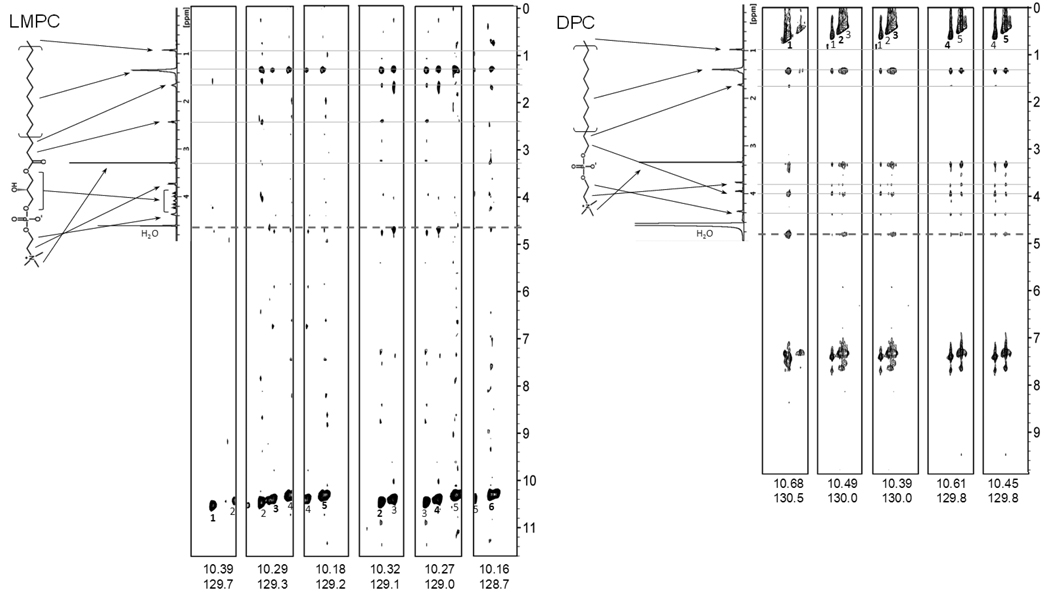

NOESY NMR Data Shows Differences in DAGK-Detergent Interactions for DPC Versus LMPC

3-D 1H,15N-NOESY-TROSY NMR spectra were acquired for U-15N-DAGK in both DPC and LMPC micelles. We used the “half-filtered” version of this 3-D experiment, which leads to NOE crosspeaks being observed for pairs of proximal protons for which at least one of the two interacting protons is directly attached to 15N. In analyzing this data we focused on NOEs between the tryptophan side chain indole NH proton and detergent protons, observation of which can be taken as an indication of at least transient proximity (<5 angstroms) between the indole proton and protons on the detergent 2.

Figure 7 shows 2-D strip plots from the 1H,15N-NOESY data that illustrate the NOEs observed between the indole protons and the detergents. In the case of DPC (Fig. 7A), it is seen that strong NOEs are observed between all indole NH protons and both choline methyl (3.3 PPM) and alkyl chain protons (1.4 PPM). That NOEs to these spatially distinct parts of DPC are simultaneously observed undoubtably reflects both the high heterogeneity of detergent/membrane protein interactions (at any given snapshot) and also the highly dynamic nature of these interactions. This data indicates that, on the average, the Trp sides chains of DAGK in DPC micelles spend as much time near the charged choline headgroup as they do with the hydrophobic micelle interior. In the case of LMPC, a significantly different pattern is seen (Fig. 7B). While strong NOEs are observed between protons from the acyl chain (1.4 PPM) and the indole peaks, NOEs between the indoles and the choline headgroup are weak or absent. Some NOEs are observed between protons from the glycerol backbone (3.8–4.25 PPM) and the indoles, although these are not as strong as the NOEs to the acyl chain. These results indicate that average position of the indole side chain in LMPC micelles is significantly deeper (towards the apolar micellar interior) than in the case of DPC, such that direct indole/choline interactions are largely avoided in the former case. The Trp side chains are not so deeply buried, however, that NOEs are observed between the indole NH and the terminal methyl group of the aliphatic chain in LMPC, consistent with the Trp side chains being restrained so as to avoid the center of the micelles.

Figure 7.

2-D strips plots showing NOEs to the tryptophan indole NH protons from 3-D 1H-15N-NOESY-TROSY spectra collected for U-15N-DAGK in DPC (A) and LMPC (B) micelles at 800 MHz and 45°C. Associated with each set of strips is a 1-D NMR spectrum for pure DPC and LMPC showing resonance assignments. In the strip plots for the DPC case (A) the indole NH proton diagonal peaks appear upfield of the rest of the spectrum rather than in the expected 9.5–10.5 PPM range because the peaks are “aliased” as a result of being outside of the spectral window of the TPPI/States-based NMR experiment used to acquire this data (39). In the LMPC case (B) the peaks appear at the expected chemical shifts because they fell within the observation sweep width. In the LMPC case, side chain-perdeuterated DAGK was used, which is why NOEs between the NH indole protons to their two nearest neighbors on the indole rings are not observed at 7.2–7.8 PPM, unlike the DPC case where DAGK was not deuterated and these NOEs are quite pronounced.

DISCUSSION

Early work on E. coli DAGK focused on the catalytic properties of this enzyme under conditions in which it was solubilized using Triton X-100 or alkylglycoside detergents (21–25). Under these conditions DAGK was found to require the presence of added phospholipid in order to exhibit significant catalytic activity. This led to the notion that lipids play a requisite “cofactor” role in promoting DAGK’s catalytic activity. The present works shows that the C14-based detergents LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC were able to sustain specific DAGK activities of at least 10 units/mg under standard assay conditions. Of these, LMPC yielded the highest activity (66 U/mg), with the C12- and C16- analogs of this detergent also sustaining >10 U/mg. Indeed, the Vmax for DAGK in LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC micelles was seen to be roughly 100, 50, and 20 U/mg respectively, with the 100 U/mg observed for DAGK in LMPC being roughly the same as the highest activities previously observed for the enzyme in mixed micellar, bicellar, or vesicular conditions (3;31;43;44;49).

There appear to be three key factors that promote DAGK activity. First, the C14 chain was found to be superior to either shorter or longer chains. Most likely, the diameter of micelles containing C14 chains is an optimal match for the hydrophobic span of the transmembrane domain of DAGK. While the diameters of LMPC and LMPG micelles have not been directly measured, from studies (50–53) of C16-lyso-PG and C8–12-lyso-PC, it is possible to estimate that the span of the hydrophobic domain of LMPG and LMPC micelles is in the range of 30–35 angstroms, with the thickness of the glycerol backbone/headgroup domain being roughly 10–12 angstroms on each side. Lee and co-workers have examined DAGK’s activity in a series of lipid vesicles composed of phosphatidylcholine with two mono-unsaturated chains and found that the enzyme is most active in di(C18:1)-PC vesicles (44), which have a hydrophobic span of 30 angstroms, roughly the same as estimated for LMPC and LMPG micelles. This appears to be a good match the observed hydrophobic span of the experimental DAGK structure (26), which is 30–33 angstroms. This highlights the importance of appropriate matching of the transmembrane span of a membrane protein with the thickness of the membrane or membrane-mimetic in which it sits to optimize protein structure, stability and function, as others have previously described (54–58).

A second key factor in promoting activity appears to be the presence of the glycerol spacer between the acyl chain and the charged head group, as reflected by the higher activities observed in the lyso-phospholipids relative to the alkylphosphocholines. The glycerol spacer/backbone is, of course, present in the glycerophospholipids that dominate the composition of the plasma membrane of E. coli. It is also interesting to note that the lyso-phospholipids are the only commercially available class of single-chain ionic detergents that has a polar-but-uncharged spacer between the apolar tail and the charged head group. Our results suggest that DAGK has evolved so as to prefer the presence of a glycerol spacer over an abrupt chain-to-head group transition. This may be a property shared by many other membrane proteins. Other recent studies have highlighted some of the advantages of working with lyso-phospholipids as detergents (59–61), which seem to particularly effective at sustaining high membrane protein solubility without disrupting structure and function (62–65).

Finally, DAGK exhibited a preference for the zwitterionic phosphocholine head group of LMPC over the anionic head group of LMPG. This result is strikingly similar to results for DAGK activity in lipid vesicles, where Lee et al. observed DAGK to be most active in phosphatidylcholine vesicles compared to vesicles composed of phosphatidylglycerol or phosphatidylethanolamine (42). This is despite the fact that E. coli membranes are bereft of phosphatidylcholine but are rich in phosphatidylglycerol and phosphatidylethanolamine(66). Given that DAGK actually shows a preference for anionic lipids as activators when lipids are added to neutral detergent micelles (24;25), it is seems likely the anionic charge density present in LMPG micelles represents “too much of a good thing” from DAGK’s standpoint. We have not yet tested DAGK’s activity in LMPC/LMPG mixtures. In any case, charge alone is not the only important property of the detergent headgroup, as illustrated by the fact that the zwitterionic Z3–14 and ASB-14 did not support DAGK activity. This is possibly because the orientation of the positive and negative charge with respect to the main chain are reversed in these compounds relative to the phosphocholine detergents and virtually all known natural zwitterionic phospholipids.

The most important insight regarding how LMPC, LMPG, and TDPC may promote DAGK’s catalytic activity relative to DPC is provided by NOE measurements (Figure 7). These results indicate that the Trp side chains of DAGK in both DPC and LMPC micelles interact strongly with the detergent aliphatic chains, but avoid contacts with the chain termini, which are found primarily in the center of the micelles. This is as expected for Trp side chains based both on the structure of DAGK(26) and the observation that Trp side chains are usually found in the membrane bilayer, but fairly near the surface. However, the NOE data also show that while the Trp side chains of DAGK in LMPC interact almost exclusively with the aliphatic groups and, to a lesser extent, the glycerol spacer, the situation is very different in DPC. Namely, strong NOE interactions are observed between the indole rings with the choline methyl protons located at the end of the head group. Apparently, in the absence of the glycerol spacer present in both LMPC and in most lipids of native membranes the indole side chains are forced to come in frequent contact with the most polar parts of the micelle. We suggest that it is this inappropriate contact, perhaps compounded by hydrophobic mismatch, that results in the reduction in the aromatic side chain order evident in the near-UV CD spectrum of DAGK in DPC relative to LMPC conditions, as well as DAGK’s lower activity and stability in DPC micelles.

Our conclusions that micelles comprised of certain C14 detergents can sustain DAGK in a stable and nearly fully active form and that these detergents also lead to high quality NMR spectra may be very important for future structural studies of this enzyme. While the structure of the substrate-free form of DAGK was recently determined in DPC micelles, the Km of the enzyme for MgATP and diacylglycerol are significantly elevated—to the point where structural studies of saturated DAGK-substrate complexes may be very difficult, particularly for complexes that include diacylglycerol. The results of this paper establish that in LMPC and LMPG the Km for DAGK’s substrates are close to their values under ideal conditions and are low enough such that structural studies of saturated binary and ternary complexes using NMR methods are now feasible. This is an important development. While DAGK has previously been shown to be fully active in lipid vesicles (3), bicelles (3), lipid-detergent mixed micelles (3;31), and even amphipols (40), these alternative membrane-mimetic media have not yet yielded either high quality NMR spectra or well-diffracting crystals of this enzyme.

Conclusions

Great care must be exercised when working with membrane proteins in micelles to insure that potential detergent-induced perturbations of native-like structural or functional properties are taken into account. However, the success of LMPC in sustaining DAGK’s high thermal stability and catalytic activity highlights the fact that for at least some integral membrane proteins the best-available detergents appear to exert only very modest perturbations. This is fortunate because some biophysical and biochemical methods are easier to carry out in detergent solutions than in more complex membrane-mimetic media such as bicelles, nanodiscs, lipidic cubic phases, or unilamellar vesicles. The fact that lyso-phospholipids appear to be well-suited for DAGK appears to be closely related to the fact that they are the only class of single-chain detergents that resembles the majority of phospholipids found in nature in that they have a polar-but-uncharged (glycerol) spacer that links the apolar tail to the charged headgroup. The lyso-phospholipids may be worthy of much more widespread use in membrane protein research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Megan Wadington for carrying out some of the early experimental measurements of this work and Stanley C. Howell for useful discussion and NMR technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 GM47485.

Abbreviations

- 3-D

three-dimensional

- ASB-14

3-[N,N-Dimethyl(3-myristoylaminopropyl)ammonio]propanesulfonate

- CL

bovine heart cardiolipin

- CMC

critical micelle concentration

- CYF7

cyclohexyl-1-heptylphospholcholine

- DAG

sn-1,2-diacylglycerol

- DAGK

diacylglycerol kinase

- DBG

sn-1,2-dibutyrlglycerol

- DHG

sn-1,2-dihexanoylglycerol

- DIG

digitonin

- DM

n-decyl-beta-D-maltopyranoside

- DMPC

dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine

- DPC

n-dodecylphosphocholine

- DTAB

dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide

- GRA

glycyrrhizic acid

- HDPC

n-hexadecylphosphorylcholine

- LLPC

lyso-lauroylphosphatidylcholine

- LMPC

lyso-myristoylphosphatidylcholine

- LMPG

lyso-myristoyl phosphatidylglycerol

- LPPC

lyso-palmitoylphosphatidylcholine

- LPPG

lyso-palmitoyl phosphatidylglycerol

- LS

n-lauroyl sarcosine

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NOESY

nuclear Overhauser effect NMR spectroscopy

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine

- TDPC

n-tetradecylphosphorylcholine

- TROSY

transverse relaxation-optimized NMR spectroscopy

- Trp

tryptophan

- Z3–14

Zwittergent 3–14

Footnotes

This study was supported by NIH grant RO1 GM47485.

For this study the focus is limited to indole-detergent NOEs because the side chains of other amino acids in DAGK have proven very difficult to detect or assign (even according to amino acid type—see(1;2) for a description of the nature of the difficulties). Secondly, while backbone amide proton resonances assignments are available for DAGK in DPC(3), this is not yet the case for the enzyme in LMPC micelles.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim HJ, Howell SC, Van Horn WD, Jeon YH, Sanders CR. Recent Advances in the Application of Solution NMR Spectroscopy to Multi-Span Integral Membrane Proteins. Prog. Nucl. Magn Reson. Spectrosc. 2009;55:335–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders CR, Sonnichsen F. Solution NMR of membrane proteins: practice and challenges. Magn Reson. Chem. 2006;44(Spec No):S24–S40. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czerski L, Sanders CR. Functionality of a membrane protein in bicelles. Anal. Biochem. 2000;284:327–333. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Griffith MT, Roth CB, Jaakola VP, Chien EY, Velasquez J, Kuhn P, Stevens RC. A specific cholesterol binding site is established by the 2.8 A structure of the human beta2-adrenergic receptor. Structure. 2008;16:897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunte C, Richers S. Lipids and membrane protein structures. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:406–411. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin L, Sharpe MA, Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. Conserved lipid-binding sites in membrane proteins: a focus on cytochrome c oxidase. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichow SL, Gonen T. Lipid-protein interactions probed by electron crystallography. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009;19:560–565. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choowongkomon K, Carlin CR, Sonnichsen FD. A structural model for the membrane-bound form of the juxtamembrane domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24043–24052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502698200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou JJ, Kaufman JD, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Bax A. Micelle-induced curvature in a water-insoluble HIV-1 Env peptide revealed by NMR dipolar coupling measurement in stretched polyacrylamide gel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:2450–2451. doi: 10.1021/ja017875d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang C, Tian C, Sonnichsen FD, Smith JA, Meiler J, George AL, Jr., Vanoye CG, Kim HJ, Sanders CR. Structure of KCNE1 and implications for how it modulates the KCNQ1 potassium channel. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7999–8006. doi: 10.1021/bi800875q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SY, Lee A, Chen J, MacKinnon R. Structure of the KvAP voltage-dependent K+ channel and its dependence on the lipid membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:15441–15446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507651102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacKenzie KR, Fleming KG. Association energetics of membrane spanning alpha-helices. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews EE, Zoonens M, Engelman DM. Dynamic helix interactions in transmembrane signaling. Cell. 2006;127:447–450. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mi LZ, Grey MJ, Nishida N, Walz T, Lu C, Springer TA. Functional and structural stability of the epidermal growth factor receptor in detergent micelles and phospholipid nanodiscs. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10314–10323. doi: 10.1021/bi801006s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faham S, Bowie JU. Bicelle crystallization: a new method for crystallizing membrane proteins yields a monomeric bacteriorhodopsin structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;316:1–6. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nath A, Atkins WM, Sligar SG. Applications of phospholipid bilayer nanodiscs in the study of membranes and membrane proteins. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2059–2069. doi: 10.1021/bi602371n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popot JL. Amphipols, Nanodiscs, and Fluorinated Surfactants: Three Nonconventional Approaches to Studying Membrane Proteins in Aqueous Solutions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010 doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052208.114057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prive GG. Lipopeptide detergents for membrane protein studies. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009;19:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prosser RS, Evanics F, Kitevski JL, Al-Abdul-Wahid MS. Current applications of bicelles in NMR studies of membrane-associated amphiphiles and proteins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8453–8465. doi: 10.1021/bi060615u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders CR, Kuhn HA, Gray DN, Keyes MH, Ellis CD. French swimwear for membrane proteins. Chembiochem. 2004;5:423–426. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohnenberger E, Sandermann H., Jr. Lipid dependence of diacylglycerol kinase from Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 1983;132:645–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russ E, Kaiser U, Sandermann H., Jr. Lipid-dependent membrane enzymes. Purification to homogeneity and further characterization of diacylglycerol kinase from Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988;171:335–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider EG, Kennedy EP. Partial purification and properties of diglyceride kinase from Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1976;441:201–212. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(76)90163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh JP, Bell RM. sn-1,2-Diacylglycerol kinase of Escherichia coli. Structural and kinetic analysis of the lipid cofactor dependence. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:15062–15069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh JP, Bell RM. sn-1,2-Diacylglycerol kinase of Escherichia coli. Mixed micellar analysis of the phospholipid cofactor requirement and divalent cation dependence. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:6239–6247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Horn WD, Kim HJ, Ellis CD, Hadziselimovic A, Sulistijo ES, Karra MD, Tian C, Sonnichsen FD, Sanders CR. Solution nuclear magnetic resonance structure of membrane-integral diacylglycerol kinase. Science. 2009;324:1726–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.1171716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y, Bowie JU. Building a thermostable membrane protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:6975–6979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller KJ, McKinstry MW, Hunt WP, Nixon BT. Identification of the diacylglycerol kinase structural gene of Rhizobium meliloti 1021. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1992;5:363–371. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-5-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oxenoid K, Sonnichsen FD, Sanders CR. Topology and secondary structure of the N-terminal domain of diacylglycerol kinase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12876–12882. doi: 10.1021/bi020335o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oxenoid K, Kim HJ, Jacob J, Sonnichsen FD, Sanders CR. NMR assignments for a helical 40 kDa membrane protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5048–5049. doi: 10.1021/ja049916m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badola P, Sanders CR. Escherichia coli diacylglycerol kinase is an evolutionarily optimized membrane enzyme and catalyzes direct phosphoryl transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24176–24182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh JP, Fahrner L, Bell RM. sn-1,2-diacylglycerol kinase of Escherichia coli. Diacylglycerol analogues define specificity and mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:4374–4381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riek R, Pervushin K, Wuthrich K. TROSY and CRINEPT: NMR with large molecular and supramolecular structures in solution. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:462–468. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weigelt J. Single scan, sensitivity- and gradient-enhanced TROSY for multidimensional NMR experiments. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1998;120:10778–10779. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Czisch M, Boelens R. Sensitivity enhancement in the TROSY experiment. J. Magn Reson. 1998;134:158–160. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salzmann M, Pervushin K, Wider G, Senn H, Wuthrich K. TROSY in triple-resonance experiments: new perspectives for sequential NMR assignment of large proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:13585–13590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu G, Kong XM, Sze KH. Gradient and sensitivity enhancement of 2D TROSY with water flip-back, 3D NOESY-TROSY and TOCSY-TROSY experiments. Journal of Biomolecular Nmr. 1999;13:77–81. doi: 10.1023/A:1008398227519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulte-Herbruggen T, Briand J, Meissner A, Sorensen OW. Spin-state-selective TPPI: a new method for suppression of heteronuclear coupling constants in multidimensional NMR experiments. J. Magn Reson. 1999;139:443–446. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorzelle BM, Hoffman AK, Keyes MH, Gray DN, Ray DG, Sanders CR. Amphipols can support the activity of a membrane enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11594–11595. doi: 10.1021/ja027051b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vinogradova O, Sonnichsen F, Sanders CR. On choosing a detergent for solution NMR studies of membrane proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 1998;11:381–386. doi: 10.1023/a:1008289624496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lau FW, Nauli S, Zhou Y, Bowie JU. Changing single side-chains can greatly enhance the resistance of a membrane protein to irreversible inactivation. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;290:559–564. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pilot JD, East JM, Lee AG. Effects of phospholipid headgroup and phase on the activity of diacylglycerol kinase of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14891–14897. doi: 10.1021/bi011333r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pilot JD, East JM, Lee AG. Effects of bilayer thickness on the activity of diacylglycerol kinase of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8188–8195. doi: 10.1021/bi0103258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rogers DM, Hirst JD. First-principles calculations of protein circular dichroism in the near ultraviolet. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11092–11102. doi: 10.1021/bi049031n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagy JK, Lonzer WL, Sanders CR. Kinetic study of folding and misfolding of diacylglycerol kinase in model membranes. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8971–8980. doi: 10.1021/bi010202n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Y, Lau FW, Nauli S, Yang D, Bowie JU. Inactivation mechanism of the membrane protein diacylglycerol kinase in detergent solution. Protein Sci. 2001;10:378–383. doi: 10.1110/ps.34201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Q, Mittal R, Huang L, Travis B, Sanders CR. Bolaamphiphile-class surfactants can stabilize and support the function of solubilized integral membrane proteins. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11606–11608. doi: 10.1021/bi9018708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lau FW, Chen X, Bowie JU. Active sites of diacylglycerol kinase from Escherichia coli are shared between subunits. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5521–5527. doi: 10.1021/bi982763t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chou JJ, Baber JL, Bax A. Characterization of phospholipid mixed micelles by translational diffusion. J. Biomol. NMR. 2004;29:299–308. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000032560.43738.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lipfert J, Columbus L, Chu VB, Lesley SA, Doniach S. Size and shape of detergent micelles determined by small-angle X-ray scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:12427–12438. doi: 10.1021/jp073016l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mendz GL, Jamie IM, White JW. Effects of acyl chain length on the conformation of myelin basic protein bound to lysolipid micelles. Biophys. Chem. 1992;45:61–77. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(92)87024-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vitiello G, Ciccarelli D, Ortona O, D'Errico G. Microstructural characterization of lysophosphatidylcholine micellar aggregates: the structural basis for their use as biomembrane mimics. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;336:827–833. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Botelho AV, Huber T, Sakmar TP, Brown MF. Curvature and hydrophobic forces drive oligomerization and modulate activity of rhodopsin in membranes. Biophys. J. 2006;91:4464–4477. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Columbus L, Lipfert J, Jambunathan K, Fox DA, Sim AY, Doniach S, Lesley SA. Mixing and matching detergents for membrane protein NMR structure determination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7320–7326. doi: 10.1021/ja808776j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holt A, Killian JA. Orientation and dynamics of transmembrane peptides: the power of simple models. Eur. Biophys. J. 2010;39:609–621. doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0567-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee AG. Lipid-protein interactions in biological membranes: a structural perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1612:1–40. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soubias O, Niu SL, Mitchell DC, Gawrisch K. Lipid-rhodopsin hydrophobic mismatch alters rhodopsin helical content. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12465–12471. doi: 10.1021/ja803599x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beel AJ, Mobley CK, Kim HJ, Tian F, Hadziselimovic A, Jap B, Prestegard JH, Sanders CR. Structural studies of the transmembrane C-terminal domain of the amyloid precursor protein (APP): does APP function as a cholesterol sensor? Biochemistry. 2008;47:9428–9446. doi: 10.1021/bi800993c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krueger-Koplin RD, Sorgen PL, Krueger-Koplin ST, Rivera-Torres IO, Cahill SM, Hicks DB, Grinius L, Krulwich TA, Girvin ME. An evaluation of detergents for NMR structural studies of membrane proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 2004;28:43–57. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000012875.80898.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tian C, Vanoye CG, Kang C, Welch RC, Kim HJ, George AL, Jr., Sanders CR. Preparation, functional characterization, and NMR studies of human KCNE1, a voltage-gated potassium channel accessory subunit associated with deafness and long QT syndrome. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11459–11472. doi: 10.1021/bi700705j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aiyar N, Nambi P, Stassen F, Crooke ST. Solubilization and reconstitution of vasopressin V1 receptors of rat liver. Mol. Pharmacol. 1987;32:34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aiyar N, Bennett CF, Nambi P, Valinski W, Angioli M, Minnich M, Crooke ST. Solubilization of rat liver vasopressin receptors as a complex with a guanine-nucleotide-binding protein and phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Biochem. J. 1989;261:63–70. doi: 10.1042/bj2610063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aiyar N, Valinski W, Nambi P, Minnich M, Stassen FL, Crooke ST. Solubilization of a guanine nucleotide-sensitive form of vasopressin V2 receptors from porcine kidney. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1989;268:698–706. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang P, Liu Q, Scarborough GA. Lysophosphatidylglycerol: a novel effective detergent for solubilizing and purifying the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Anal. Biochem. 1998;259:89–97. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shibuya I. Metabolic regulations and biological functions of phospholipids in Escherichia coli. Prog. Lipid Res. 1992;31:245–299. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(92)90010-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]