Abstract

Objective

Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) are protective in both myocardial and brain ischemia, variously attributed to activation of KATP channels or blockade of adhesion molecule upregulation. In this study we tested whether EETs would be protective in lung ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Methods

The filtration coefficient (Kf), a measure of endothelial permeability, and expression of the adhesion molecules VCAM and ICAM were measured after 45 min ischemia and 30 min reperfusion in isolated rat lungs.

Results

Kf increased significantly after ischemia-reperfusion alone vs time controls, an effect dependent upon extracellular Ca2+ though not on the EET-regulated channel TRPV4. Inhibition of endogenous EET degradation or administration of exogenous 11,12- or 14,-15-EET at reperfusion significantly limited the permeability response to ischemia-reperfusion. The beneficial effect of 11,12-EET was not prevented by blockade of KATP channels nor by blockade of TRPV4. Finally, 11,12-EET-dependent alteration in adhesion molecules expression is unlikely to explain its beneficial effect, since the expression of the adhesion molecules VCAM and ICAM in lung after ischemia-reperfusion was similar to that in controls.

Conclusion

EETs are beneficial in the setting of lung ischemia-reperfusion, when administered at reperfusion. However, further study will be needed to elucidate the mechanism of action.

INTRODUCTION

Metabolism of arachidonic acid by P450 epoxygenases results in synthesis of a family of four epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (EET) regioisomers: 5,6-EET, 8,9-EET, 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET. In heart and brain, EETs appear to act as protective mediators in the setting of ischemia and reperfusion. Either administration of exogenous EETs or blockade of EET degradation by inhibiting soluble epoxide hydrolase limit cerebral and myocardial ischemic injury and/or infarct size (7;9;27). Further, upregulation of a P450 epoxygenase enzyme in rat brain after transient ischemic preconditioning is associated with reduced infarct size resulting from carotid occlusion (1).

At present, we do not know whether EETs can modulate the acute lung injury response to global ischemia and reperfusion in the lung. Some EETs can display pro-inflammatory properties in lung. Both 5,6- and 14,15-EET increase endothelial permeability in rat lung via activation of the transient receptor potential channel TRPV4 (2;4). Similarly, endogenous EETs mediate the permeability response to mechanical perturbation in mouse lung in a TRPV4-dependent fashion (10;12). Thus their beneficial impact in heart and brain does not necessarily predict outcomes after lung ischemia-reperfusion. Of the EET regioisomers, 11,12-EET appears to be the most likely candidate to provide therapeutic benefit in lung ischemia-reperfusion, since it has no impact on lung endothelial permeability (2). Further, 11,12-EET displays anti-inflammatory action in systemic endothelial cells by inhibiting TNFα-induced expression of the adhesion molecule VCAM-1, and to much less extent ICAM (28). While 11,12-EET stimulates neutrophil aggregation, it nonetheless decreases adherence of activated neutrophils to endothelium (29).

Taylor and colleagues have shown that the increase in endothelial permeability after ischemia-reperfusion in the rat lung can be attenuated by interfering with leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion (23;25). Further, the increase in endothelial permeability induced by ischemia-reperfusion can be blocked by antibodies against TNFα (13). Thus, plausibly administration of exogenous 11,12-EET could limit TNFα–induced upregulation of adhesion molecules leading to attenuation of acute lung injury after ischemia and reperfusion. Nonetheless, since ischemia-reperfusion may enhance endogenous EET synthesis (26), EETs could actually contribute to the increase in lung endothelial permeability (2;4). To resolve these alternatives, in this study we tested whether ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat lung requires Ca2+ entry via TRPV4, whether endogenous and/or exogenous EETs would attenuate the increase in lung endothelial permeability induced by ischemia-reperfusion and finally whether upregulation of the adhesion molecules VCAM and ICAM could participate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal protocols for this study were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of South Alabama, and adhered to the Guide for the Care of Use of Laboratory Animals (Department of Health and Human Services).

Isolated lung preparation and assessment of endothelial injury

The isolated rat lung preparation and measurement of endothelial permeability in our hands have been previously described (2;4). Lungs isolated from anesthetized rats (pentobarbital sodium, 50 mg/kg, i.p.) were perfused at a constant flow (~0.03 ml/g body weight, pH 7.4, 37 °C) with 4% albumin buffer (in mmol/L: 116 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.8 MgSO4, 1.0 NaH2PO4, and 5.6 glucose) containing physiologic or low CaCl2 (2.2 or 0.02 mM, respectively). Pulmonary artery (Pa), venous (Pv), and end-expiratory airway (Paw) pressures and lung weight were recorded (Astromed polygraph, model 7400). Pv was adjusted to establish a baseline isogravimetric state under zone III conditions, with Paw of 3 cmH2O. Total pulmonary vascular resistance (Rt) was calculated. Pulmonary endothelial permeability was assessed using the filtration coefficient (Kf), by measuring the rate of lung weight gain 13–15 minutes after increasing Pv by 8–10 cmH2O. This rate was divided by the concomitant increment in capillary pressure (Pc) and then normalized to 1 g dry lung wt. Pc was measured by the double occlusion technique (35).

Experimental protocols

In the first series of experiments, perfusate contained physiologic Ca2+. Responses in time controls (n=7) were compared to those in lungs challenged with ischemia-reperfusion. During the ischemic period (45 minutes), lungs were not perfused or ventilated. Kf and hemodynamic measurements were repeated after 30 minutes of reperfusion. These ischemia-reperfusion experiments were interspersed between other groups described below and results in the cumulative group presented (n=15).

We determined whether entry of extracellular Ca2+ was involved in the lung endothelial permeability response to ischemia-perfusion. Lungs perfused with a low Ca2+ buffer were challenged with 45 (n=4) or 60 (n=4) min ischemia followed by 30 min reperfusion. These results were compared to those in a low Ca2+ time control group (n=5). We have previously shown that lung endothelial permeability is stable with this low Ca2+ concentration (0.02 mM), and further, that this concentration effectively prevents permeability responses to activation of store-operated channels or TRPV4 (3;4). Since EETs promote endothelial Ca2+ entry via TRPV4 and result in Ca2+ entry-dependent acute lung injury (4;37), we ruled out participation of TRPV4 in ischemia-reperfusion injury by pretreating a group of lungs with the TRPV antagonist ruthenium red prior to 45 min ischemia followed by 30 min reperfusion (1 μM, n=3). In this latter group and all remaining experiments, buffer containing physiological Ca2+ was used.

In the next series of experiments, we addressed the impact of 11,12-EET on the permeability response to 45 min ischemia followed by reperfusion, and evaluated potential mechanisms by which 11,12-EET might act. A group of lungs was pretreated with 1-adamantanyl-3-{5-[2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethoxy]pentyl]}urea (AEPU, 100 μM, n=6), also known as sEHI 950 (16). Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase should prevent degradation of endogenous EETs (30) prior to ischemia-reperfusion. AEPU is well adapted to perfusion studies such as these due to its relatively high water solubility (120 μg/ml), low melting point leading to rapid dissolution (mp 78.5–79 °C), and relatively low lipophilicity (log P 2.8). In a parallel series of experiments, we determined whether administration of exogenous 11,12-EET (300 nM) could attenuate the permeability responses to ischemia-reperfusion: lungs were treated with 11,12-EET either prior to ischemia (n=5) or at reperfusion (n=6). To determine whether the impact of 11,12-EET was specific to this regioisomer, 14,15-EET (300 nM) was added at reperfusion in a separate group of lungs (n=4). Since blockade of KATP channels prevents EET-induced protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in the heart (9), a group of lungs was pretreated with the KATP channel inhibitor glibenclamide (10 μM, n=5) and 11,12-EET administered at reperfusion. While most EET isomers activate TRPV4 and increase lung endothelial permeability (4), we considered it unlikely that any beneficial effect of 11,12-EET would be due to TRPV4-mediated Ca2+ entry. Nonetheless, to rule out any participation of this cation channel, we pretreated another group of lungs with the broad TRPV antagonist ruthenium red (1μM), then administered 11,12-EET at reperfusion (n=5).

VCAM and ICAM expression

Immunohistochemistry was used to document expression of VCAM and ICAM in rat lung. Lungs were perfusion-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde upon isolation (controls, n=3) or after baseline measurements and subsequent 45 minutes of ischemia and 30 minutes of reperfusion (n=3). In parallel time control experiments, lungs were perfused for a similar period of time after baseline measurements (75 min), but without ischemia or reperfusion (n=3). A final group of lungs was fixed by airway instillation of paraformaldehyde immediately at the conclusion of the ischemic period (n=3), to ensure that the vasculature did not experience any period of reperfusion. Sections (5 μm) were cut from paraffin-embedded lung blocks and placed on poly-L-lysine coated slides for immunohistochemistry. Following overnight incubation with goat anti-rat polyclonal primary antibodies targeting VCAM or ICAM (1:50, 4 °C), slides were treated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200 or 1:500, respectively). Diaminobenzidine was used for color development, while hematoxylin was used for counterstaining. Images were collected via light microscopy (20x).

Volume fractions for VCAM and ICAM in the alveolar septal wall were determined using a morphometric point counting method. Images of immunostained lung sections were visualized in Paint Shop Pro with a grid overlay. A total of 8–12 images per lung from 3 lungs in each treatment group were analyzed. VCAM or ICAM volume fractions were calculated for each lung as the ratio of positively stained points relative to total points landing on the alveolar septal wall. The volume fraction data were then averaged for each treatment group.

Drugs

11,12- and 14,15-EET were obtained from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Buffer reagents were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Anti-VCAM and secondary antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-ICAM antibodies were obtained from R & D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). All other reagents and drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Statistics

Data are presented as means±SE. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed by using an unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

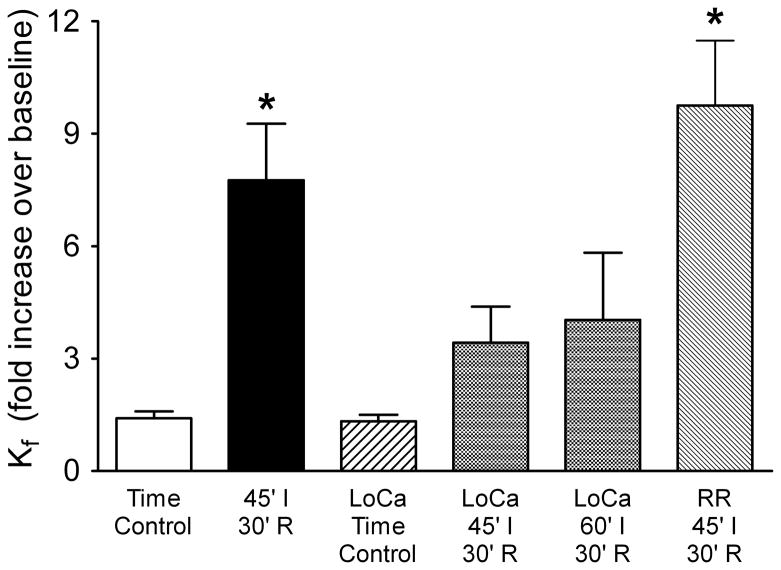

When lungs were perfused with physiologic buffer, 45 minutes of ischemia followed by 30 minutes reperfusion led to a 7.8-fold increase in Kf (Figure 1). These data are compared to outcomes in experiments designed to evaluate a role for Ca2+ entry (Figure 1). Ischemia-reperfusion had little impact on lung endothelial permeability when a low Ca2+ perfusate was utilized, regardless of whether the lungs were ischemic for 45 or 60 min. These data suggest that the permeability response to ischemia-reperfusion is significantly dependent upon extracellular Ca2+. Although ischemia-reperfusion and TRPV4 activation both target the lung microcirculation and both require Ca2+ entry (4;15), blockade of Ca2+ entry with the TRPV antagonist ruthenium red did not prevent the permeability response to ischemia-reperfusion Final Kf remained near baseline in time control experiments utilizing either the physiologic or low Ca2+ buffers. A summary of hemodynamics and Kf during baseline for all isolated lung experiments (Table 1) shows that these measures were not significantly impacted by lowering perfusate Ca2+ to 0.02 mM.

Figure 1.

Dependence of ischemia-reperfusion injury on extracellular Ca2+. In rat lung, 45 min ischemia (45′ I) followed by 30 min reperfusion (30′ R) increased the filtration coefficient (Kf) nearly 8-fold (n=15) compared to that in time controls (n=7). Although low Ca 2+ perfusate (LoCa) had no impact in time control lungs (n=5), this perfusate did blunt the permeability response to 45 (n=4) or 60 min (n=4) ischemia followed by reperfusion. In contrast, the TRPV antagonist ruthenium red (RR) had no effect. *P<0.05 vs control (one-way ANOVA). Thus, while the permeability response to ischemia-reperfusion in rat lung requires Ca2+ entry, the Ca2+ channel TRPV4 does not appear to play a role.

Table 1.

Baseline hemodynamics and permeability in isolated rat lungs

| Perfusate [Ca2+], mM | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1.8 | 0.02 | |

| N | 56 | 13 |

| Body weight, g | 371±8 | 417±16 |

| Q, ml/min | 13.2±0.2 | 13.7±0.4 |

| Pa, cmH2O | 14.4±0.4 | 14.7±0.6 |

| Pc, cmH2O | 9.5±0.2 | 9.6±0.4 |

| Pv, cmH2O | 4.2±0.1 | 4.0±0.2 |

| Rt, cmH2O/l/min | 0.77±0.03 | 0.77±0.05 |

| Kf, ml/min/cmH2O/g dry wt | 0.0087±0.0004 | 0.0085±0.0009 |

Q, perfusate flow; Pa, pulmonary artery pressure; Pc, pulmonary capillary pressure; Pv, pulmonary venous pressure; Rt, total vascular resistance; Kf, filtration coefficient.

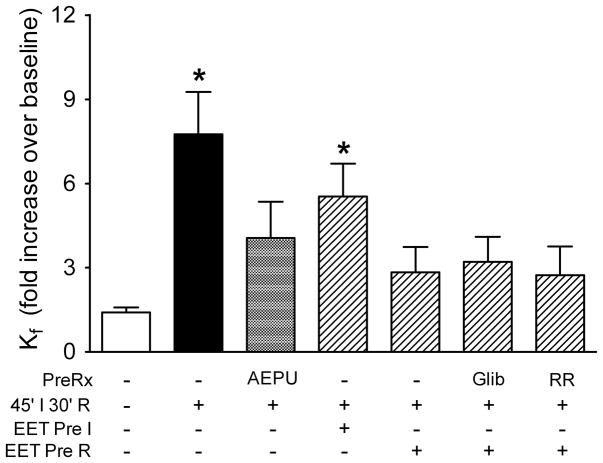

The next series of experiments evaluated whether EETs could protect barrier integrity in the setting of lung ischemia-reperfusion. Pretreatment with the soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor AEPU significantly attenuated the permeability response to ischemia-reperfusion (Figure 2). Kf only increased 4.1-fold after ischemia-reperfusion (not significantly different from control), suggesting that endogenous EETs could protect the lung to some extent against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Though not shown, blockade of P450 epoxygenases with PPOH to limit EET synthesis was not protective. Several lungs failed immediately upon reperfusion, with fulminant alveolar flooding. In the remaining five lungs, mean Kf increased 7-fold on average compared to baseline. Administration of 11,12-EET prior to ischemia had minimal impact on the permeability response (Figure 2). However, when 11,12-EET was added at reperfusion, Kf only increased 2.8-fold. Though not shown in Figure 2, addition of 14,15-EET at reperfusion had a similar protective effect: Kf increased 2.4±0.8 fold after ischemia reperfusion. Protection afforded by addition of 11,12-EET at reperfusion could not be prevented by pretreatment of lungs with the KATP channel antagonist glibenclamide: Kf increased 3.2-fold from baseline in this group after ischemia-reperfusion. Similarly, use of ruthenium red to block Ca2+ entry via TRPV4 did not prevent the beneficial effect of 11,12-EET: Kf increased 2.7-fold.

Figure 2.

Endogenous and exogenous EETs protect against ischemia-reperfusion in rat lung. Results in controls and lungs challenged with 45′ ischemia-30′ reperfusion (IR, from Figure 1) are repeated here for ease of comparison. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase (AEPU) limited the permeability response to ischemia-reperfusion, supporting a protective role for endogenous EETs. Although 11,12-EET did not have marked impact when given prior to ischemia (Pre I), it was effective given at reperfusion (Pre R). Neither glibenclamide (Glib) nor ruthenium red (RR) prevented the protective effect of 11,12-EET in this model. *P<0.05 vs control (one-way ANOVA).

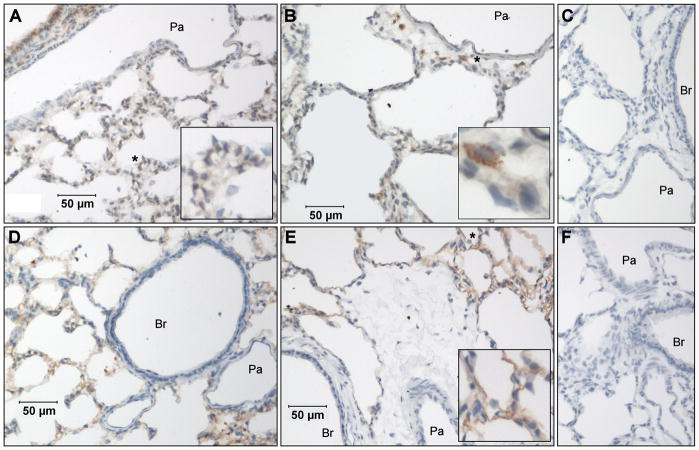

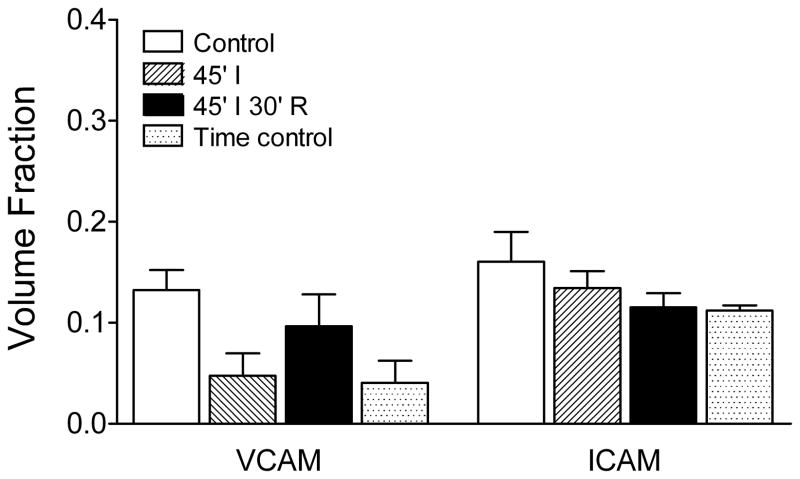

Finally, we evaluated adhesion molecule expression in lungs using immunohistochemistry (Figure 3) and quantitative morphometry (Figure 4). In controls, VCAM was expressed in bronchiolar epithelium, type II alveolar epithelium, and broadly across sections of the alveolar septal wall (Figure 3A). We interpret the latter result to mean predominantly positive expression in septal capillaries. In contrast, ICAM expression appeared to be limited to alveolar type I epithelium (Figure 3D). In lungs subjected to ischemia-reperfusion, VCAM expression in airways and the alveolar septal wall did not change. However, positive staining was occasionally observed in mononuclear cells situated around the septal wall or in perivascular/peribronchiolar interstitial cuffs and in extra-alveolar vessel endothelium (Figure 3B). There was no significant change in the VCAM volume fraction in the alveolar septal wall (Figure 4) in lungs subjected to ischemia, ischemia-reperfusion, or time controls. Similarly, the pattern of ICAM staining in lung after ischemia-reperfusion (Figure 3E) did not change after ischemia-reperfusion, with expression remaining limited to type I alveolar epithelium. The volume fraction for ICAM in the alveolar septal wall did not vary significantly between the four experimental groups (Figure 4). Sections of lung exposed to only secondary antibodies showed no positive staining at either the 1:200 (Figure 3C) or 1:500 dilutions (Figure 3F). Additional images for all four experimental groups can be found in Supplemental material (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 3.

VCAM and ICAM expression in rat lung. In control lungs, VCAM was expressed predominantly in bronchiolar epithelium and type II alveolar epithelium, with some positive staining across sections of the alveolar septal wall (A). In lungs subjected to ischemia-reperfusion, the pattern of VCAM expression in airways and the alveolar septal wall did not change, though positive staining was occasionally observed in mononuclear cells situated around the septal wall, in perivascular/peribronchiolar interstitial cuffs, and in endothelium of small extra-alveolar vessels (B). In contrast to the pattern of VCAM staining, ICAM expression in controls appeared to be limited to alveolar type I epithelium (D), a pattern which did not change after ischemia-reperfusion (E). Sections of lung exposed to only secondary antibodies showed no positive staining at either the 1:200 (C) or 1:500 dilutions (F). Br, bronchiole; Pa, pulmonary arteriole; *areas enlarged in insets. Additional images for these two groups, as well as representative images from lungs exposed only to ischemia or in time control lungs, are available in Supplemental material (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 4.

VCAM and ICAM volume fractions in the alveolar septal wall. A morphometric approach was used to quantitatively assess volume fractions for adhesion molecule expression in the alveolar septal wall (see text for details). Neither the VCAM nor ICAM volume fraction differed among the four experimental groups: control lungs fixed after isolation, lungs exposed to ischemia alone or ischemia-reperfusion, and time controls (one-way ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

Results of this study confirm the significant impact of ischemia-reperfusion on lung endothelial permeability. In our hands, Kf increased nearly 8-fold after ischemia-reperfusion. Since alveolar capillaries and post-capillary venules are the target of this injury, substantial alveolar flooding ensues (5;15;31). Despite the magnitude of this insult, we show for the first time that blockade of EET degradation or administration of low-dose exogenous EETs provide significant protection against the increased lung endothelial permeability resulting from ischemia-reperfusion. However, the mechanism of this protection remains elusive. Neither ischemia alone nor ischemia-reperfusion was accompanied by up-regulation of VCAM or ICAM in the alveolar septal wall within the time frame of our study, compared to controls. Further, while ischemia-reperfusion injury requires Ca2+ entry from the extracellular fluid, the protective effect of 11,12-EET could not be abrogated by blockade of TRPV4 channels. Finally, although protection afforded by EETs in other vascular beds can be mediated via activation of KATP channels, blockade of these channels did not prevent the EET-dependent attenuation of the ischemia-reperfusion permeability response in rat lung.

Based on the ability of the soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor AEPU to limit the increase in Kf induced by ischemia-reperfusion, we conclude that endogenous EETs indeed are protective in this setting. While the impact of ischemia-reperfusion on EET synthesis and release in lung has not been determined, EETs are released into canine coronary venous blood with ischemia-reperfusion (26). The beneficial impact of the soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor supports the notion that EETs are synthesized and released from rat lung in our experiments. In both rat and human lung, 14,15-EET is the predominant EET regioisomer though 11,12-EET also makes a major contribution (38). The pool may reflect steady state synthesis as well as EETs esterified into endothelial plasma membrane phospholipids (36). The relative proportions of 14,15- and 11,12-EET in the endogenous pool of EETs in lung may not necessarily predict the predominant EET released with ischemia-reperfusion. In perfused human lung, challenge with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 led to rapid release of 11,12-EET, but little 14,15-EET, into the perfusate (17). Although micromolar concentrations of most EET regioisomers increase permeability in rat lung (2), blockade of EET synthesis with PPOH did not attenuate ischemia-reperfusion induced endothelial injury. This finding, along with the observation that AEPU-induced blockade of EET degradation was protective, suggests that on balance, endogenous EETs limit the increase in lung endothelial permeability induced by ischemia-reperfusion. Nonetheless, these experiments did not elucidate the mechanism underlying the protective affect. To that end, we utilized exogenous EETs and assessed a role for adhesion molecules and channels implicated in other experimental models.

The involvement of leukocytes (including lymphocytes, neutrophils and macrophages) in lung injury subsequent to ischemia-reperfusion has been well documented (6;24). Further, TNFα and up-regulation of adhesion molecules subsequent to ischemia-reperfusion have been implicated in lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. TNFα levels rise early after ischemia reperfusion (8). This cytokine is known to upregulate neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells in an ICAM-dependent fashion (11;18). Taylor and colleagues provided convincing evidence that both the leukocyte retention and the increased permeability response to ischemia-reperfusion were ameliorated by immunoneutralization of ICAM (23) or TNFα (13). Alternatively, the early injury response to ischemia-reperfusion in rat lung may require lymphocyte retention (25) and up-regulation of VCAM (34).

Given this background and the observation that 11,12-EET inhibited TNFα-induced VCAM, and to less an extent ICAM, expression in endothelial cells (28), 11,12-EET could plausibly have been protective in the setting of lung ischemia-reperfusion due to down-regulation of adhesion molecule expression. However, in the current study neither VCAM nor ICAM expression was significantly altered after ischemia-reperfusion compared to that in freshly isolated or time control lungs, despite a substantial ischemia-reperfusion-induced increase in endothelial permeability. Several possibilities may explain this result. First, lungs were perfused for a relatively brief period following ischemia. TNFα-dependent ICAM up-regulation, for example, may not be evident until 2–4 hours after TNFα application (11;22). More likely, even brief flush of the lung vasculature, as in the control group (Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure 5), evokes surface expression of adhesion molecules. The surface expression of VCAM and ICAM observed in controls may explain the retention of leukocytes in isolated lung in the absence of injury (23;23). These data suggest that some trigger aside from adhesion molecule expression per se must be required to elicit endothelial injury after ischemia-reperfusion. Further, while treatment of lungs with 11,12-EET at reperfusion clearly limited ischemia-reperfusion injury, this protective effect is unlikely to be due to inhibition of TNFα-mediated up-regulation of VCAM or ICAM expression. Further evidence supporting this conclusion is derived from the often disparate effects of EETs. Most pertinent to this study, Node et al. (28) reported that 11,12- EET prevented the impact of TNFα on VCAM expression in endothelial cells and on mononuclear cell adhesion to carotid artery endothelium. In contrast, they found that 14,15-EET did not have similar anti-inflammatory effects. Nonetheless, in the rat lung 11,12- and 14,15-EET limited the impact of ischemia-reperfusion on endothelial permeability to a similar extent. Collectively, these observations suggest that a role for adhesion molecules in ischemia-reperfusion injury is complex. Further, our data suggests that EETs are not likely providing benefit due to altered endothelial expression of adhesion molecules.

Next, we turned to investigation of whether the effect of 11,12-EET was due to activation of critical channels in lung endothelium known to be targets for EETs, such as Ca2+ channels. We have shown that low micromolar doses of 5,6- and 14,15-EET increase lung endothelial permeability via a Ca2+ entry- and TRPV4-dependent mechanism (2;4). As a result of EET-dependent TRPV4 activation, the endothelial barrier in the lung alveolar septum is disrupted and alveolar flooding ensues. While submicromolar concentrations of EETs do not impact lung endothelial permeability (unpublished observations), concentrations in this range can still promote Ca2+ entry into endothelial cells in a dose- and TRPV4-dependent manner (37). Ischemia-reperfusion targets the septal microvascular barrier (5;15), though whether Ca2+ entry is required for the injury is controversial. Chetham and colleagues (5) concluded that ischemia-reperfusion injury was independent of Ca2+ entry, since Kf increased after ischemia-reperfusion when a low (10 μM) Ca2+ perfusate was used to limit Ca2+ entry. Alvarez et al. subsequently reported that lung endothelial permeability increased over time when perfusate Ca2+ concentrations lower than 20 μM were used. At 20 μM Ca2+ however, barrier integrity is stable and the permeability response to activation of TRPV4 is completely abrogated (4). Using this latter low Ca2+ paradigm, we found that the lung endothelial permeability response to ischemia-reperfusion does require extracellular Ca2+ (Figure 1). However, TRPV4 is not likely to be involved in either the development of ischemia-reperfusion injury or the protection afforded by EETs. Although blockade of EET degradation by targeting soluble epoxide hydrolase attenuated the permeability response to ischemia-reperfusion, the TRPV antagonist ruthenium red failed to either attenuate the permeability response to ischemia-reperfusion or to block 11,12-EET-induced protection against injury.

One final mechanism considered for the 11,12-EET-mediated protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury involved KATP channels. EETs are known to activate KATP channels (19–21) localized to either the plasmalemmal or mitochondrial membranes in smooth muscle and cardiac myocytes. In the heart, blockade of sarcolemmal and/or mitochondrial KATP channels abrogates EET-induced protection against the myocardial dysfunction observed after ischemia and reperfusion (9;21;32;33). However, in our hands, blockade of KATP channels with glibenclamide, at a dose which should block both plasmalemmal and mitochondrial KATP channels, did not prevent 11,12-EET-mediated protection against ischemia-reperfusion. Further, although our results showed that endogenous EETs could play a protective effect, Khimenko et al. previously reported that blockade of KATP channels did not prevent ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat lung (14). Collectively these data rule out a role for KATP channels in the EET-mediated protection.

In conclusion, our study has demonstrated a clear protective benefit of endogenous and exogenous EETs against lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. While EETs do limit the increase in lung endothelial permeability resulting from ischemia-reperfusion, mechanisms commonly attributed to the benefit of EETs in coronary and brain ischemia-reperfusion do not appear to play a role in lung. Since ischemia-reperfusion failed to up-regulate expression of either VCAM or ICAM within a time frame which includes a substantial increase in endothelial permeability, we have ruled out alterations in expression of the adhesion molecules as a potential mechanism. Finally, while EETs are known to regulate KATP or TRPV4 channels, neither action underlies the beneficial role of 11,12-EET in lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. Understanding the protective role of EETs in the setting of lung ischemia-reperfusion will require further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was been supported by a grant from NHLBI (HL67461). In addition, partial support was provided by NIEHS (ES002710 and ES013933) and the American Asthma Association. The technical support provided by Sue Barnes and Freda McDonald is appreciated.

References

- 1.Alkayed NJ, Goyagi T, Joh HD, Klaus J, Harder DR, Traystman RJ, Hurn PD. Neuroprotection and P450 2C11 upregulation after experimental transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2002;33:1677–1684. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000016332.37292.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez DF, Gjerde EA, Townsley MI. Role of EETs in regulation of endothelial permeability in rat lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L445–L451. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00150.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez DF, King JA, Townsley MI. Resistance to store depletion-induced endothelial injury in rat lung after chronic heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1153–1160. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-847OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez DF, King JA, Weber D, Addison E, Liedtke W, Townsley MI. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4-mediated disruption of the alveolar septal barrier: a novel mechanism of acute lung injury. Circ Res. 2006;99:988–995. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000247065.11756.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chetham PM, Babal P, Bridges JP, Moore TM, Stevens T. Segmental regulation of pulmonary vascular permeability by store-operated Ca2+ entry. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L41–L50. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.1.L41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Perrot M, Liu M, Waddell TK, Keshavjee S. Ischemia-reperfusion-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:490–511. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-670SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorrance AM, Rupp N, Pollock DM, Newman JW, Hammock BD, Imig JD. An epoxide hydrolase inhibitor, 12-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido)dodecanoic acid (AUDA), reduces ischemic cerebral infarct size in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005;46:842–848. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000189600.74157.6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eppinger MJ, Deeb GM, Bolling SF, Ward PA. Mediators of ischemia-reperfusion injury of rat lung. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1773–1784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross GJ, Hsu A, Falck JR, Nithipatikom K. Mechanisms by which epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) elicit cardioprotection in rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:687–691. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamanaka K, Jian MY, Weber DS, Alvarez DF, Townsley MI, al-Mehdi AB, King JA, Liedtke W, Parker JC. TRPV4 initiates the acute calcium-dependent permeability increase during ventilator-induced lung injury in isolated mouse lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L923–L932. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00221.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Javaid K, Rahman A, Anwar KN, Frey RS, Minshall RD, Malik AB. Tumor necrosis factor-α induces early-onset endothelial adhesivity by protein kinase Cζ-dependent activation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Circ Res. 2003;92:1089–1097. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000072971.88704.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jian MY, King JA, al-Mehdi AB, Liedtke W, Townsley MI. High vascular pressure-induced lung injury requires P450 epoxygenase-dependent activation of TRPV4. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:386–392. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0192OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khimenko PL, Bagby GJ, Fuseler J, Taylor AE. Tumor necrosis factor-α in ischemia and reperfusion injury in rat lungs. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:2005–2011. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.6.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khimenko PL, Moore TM, Taylor AE. ATP-sensitive K+ channels are not involved in ischemia-reperfusion lung endothelial injury. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:554–559. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.2.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khimenko PL, Taylor AE. Segmental microvascular permeability in ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat lung. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L958–L960. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.6.L958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim IH, Tsai HJ, Nishi K, Kasagami T, Morisseau C, Hammock BD. 1,3-disubstituted ureas functionalized with ether groups are potent inhibitors of the soluble epoxide hydrolase with improved pharmacokinetic properties. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5217–5226. doi: 10.1021/jm070705c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiss L, Schutte H, Mayer K, Grimm H, Padberg W, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Synthesis of arachidonic acid-derived lipoxygenase and cytochrome P450 products in the intact human lung vasculature. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1917–1923. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9906058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lockyer JM, Colladay JS, Alperin-Lea WL, Hammond T, Buda AJ. Inhibition of nuclear factor-κB-mediated adhesion molecule expression in human endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1998;82:314–320. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu T, Hong MP, Lee HC. Molecular determinants of cardiac KATP channel activation by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19097–19104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu T, Katakam PV, VanRollins M, Weintraub NL, Spector AA, Lee HC. Dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids are potent activators of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in isolated rat coronary arterial myocytes. J Physiol. 2001;534:651–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu T, Ye D, Wang X, Seubert JM, Graves JP, Bradbury JA, Zeldin DC, Lee HC. Cardiac and vascular KATP channels in rats are activated by endogenous epoxyeicosatrienoic acids through different mechanisms. J Physiol. 2006;575:627–644. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.113985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu YT, Chen PG, Liu SF. Time course of lung ischemia-reperfusion-induced ICAM-1 expression and its role in ischemia-reperfusion lung injury. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:620–628. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01200.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore TM, Khimenko PL, Adkins WK, Miyasaka M, Taylor AE. Adhesion molecules contribute to ischemia and reperfusion-induced injury in the isolated rat lung. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:2245–2252. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.6.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore TM, Khimenko PL, Taylor AE. Endothelial damage caused by ischemia and reperfusion and different ventilatory strategies in the lung. Chin J Physiol. 1996;39:65–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore TM, Shirah WB, Khimenko PL, Paisley P, Lausch RN, Taylor AE. Involvement of CD40-CD40L signaling in postischemic lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L1255–L1262. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00016.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nithipatikom K, DiCamelli RF, Kohler S, Gumina RJ, Falck JR, Campbell WB, Gross GJ. Determination of cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic acid in coronary venous plasma during ischemia and reperfusion in dogs. Anal Biochem. 2001;292:115–124. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nithipatikom K, Moore JM, Isbell MA, Falck JR, Gross GJ. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in cardioprotection: ischemic versus reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H537–H542. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00071.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Node K, Huo Y, Ruan X, Yang B, Spiecker M, Ley K, Zeldin DC, Liao JK. Anti-inflammatory properties of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Science. 1999;285:1276–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pratt PF, Rosolowsky M, Campbell WB. Effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on polymorphonuclear leukocyte function. Life Sci. 2002;70:2521–2533. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01533-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmelzer KR, Kubala L, Newman JW, Kim IH, Eiserich JP, Hammock BD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase is a therapeutic target for acute inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9772–9777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503279102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seibert AF, Thompson WJ, Taylor AE, Wilborn WH, Barnard JW, Haynes J., Jr Reversal of increased microvascular permeability associated with ischemia-reperfusion: role of cAMP. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:389–395. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seubert J, Yang B, Bradbury JA, Graves J, DeGraff LM, Gabel S, Gooch R, Foley J, Newman J, Mao L, Rockman HA, Hammock BD, Murphy E, Zeldin DC. Enhanced postischemic functional recovery in CYP2J2 transgenic hearts involves mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels and p42/p44 MAPK pathway. Circ Res. 2004;95:506–514. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000139436.89654.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seubert JM, Sinal CJ, Graves J, DeGraff LM, Bradbury JA, Lee CR, Goralski K, Carey MA, Luria A, Newman JW, Hammock BD, Falck JR, Roberts H, Rockman HA, Murphy E, Zeldin DC. Role of soluble epoxide hydrolase in postischemic recovery of heart contractile function. Circ Res. 2006;99:442–450. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237390.92932.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegelman MH, Stanescu D, Estess P. The CD44-initiated pathway of T-cell extravasation uses VLA-4 but not LFA-1 for firm adhesion. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:683–691. doi: 10.1172/JCI8692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Townsley MI, Korthuis RJ, Rippe B, Parker JC, Taylor AE. Validation of double vascular occlusion method for Pc,i in lung and skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1986;61:127–132. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.VanRollins M, Kaduce TL, Fang X, Knapp HR, Spector AA. Arachidonic acid diols produced by cytochrome P-450 monooxygenases are incorporated into phospholipids of vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14001–14009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe H, Vriens J, Prenen J, Droogmans G, Voets T, Nilius B. Anandamide and arachidonic acid use epoxyeicosatrienoic acids to activate TRPV4 channels. Nature. 2003;424:434–438. doi: 10.1038/nature01807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeldin DC, Foley J, Ma J, Boyle JE, Pascual JM, Moomaw CR, Tomer KB, Steenbergen C, Wu S. CYP2J subfamily P450s in the lung: expression, localization, and potential functional significance. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:1111–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.