Abstract

Objective

To investigate the origins and evolutionary history of subtype C HIV-1 in Zimbabwe in a context of regional conflict and migration.

Design

HIV-1C pol sequence datasets were generated from four sequential cohorts of antenatal women in Harare, Zimbabwe sampled over 15 years (1991–2006).

Methods

One hundred and seventy-seven HIV-1C pol sequences were obtained from four successive cohorts in Zimbabwe. Maximum-likelihood methods were used to explore phylogenetic relationships between Zimbabwean HIV-1C sequences and subtype C strains from other regions. A Bayesian coalescent-based framework was used to estimate evolutionary parameters for HIV-1C in Zimbabwe, including origin and demographic growth patterns.

Results

Zimbabwe HIV-1C pol demonstrated increasing sequence divergence over the 15-year period. Nearly all Zimbabwe sequences clustered phylogenetically with subtype C strains from neighboring countries. Bayesian evolutionary analysis indicated a most recent common ancestor date of 1973 with three epidemic growth phases: an initial slow phase (1970s) followed by exponential growth (1980s), and a linearly expanding epidemic to the present. Bayesian trees provided evidence for multiple HIV-1C introductions into Zimbabwe during 1979–1981, corresponding with Zimbabwean national independence following a period of socio-political instability.

Conclusion

The Zimbabwean HIV-1C epidemic likely originated from multiple introductions in the late 1970s and grew exponentially during the 1980s, corresponding to changing political boundaries and rapid population influx from neighboring countries. The timing and phylogenetic clustering of the Zimbabwean sequences is consistent with an origin in southern Africa and subsequent expansion. HIV-1 sequence data contain important epidemiological information, which can help focus treatment and prevention strategies in light of more recent political volatility in Zimbabwe.

Keywords: epidemiology, evolutionary history, HIV-1, origin, subtype C, Zimbabwe

Introduction

HIV-1 subtype C now accounts for approximately 50% of the estimated 33 million people living with HIV/AIDS and half of the 2–3 million new infections annually [1]. Although the majority of subtype C infections are in southern Africa, this subtype also dominates the epidemics in India, Ethiopia, and southern China, and has entered east Africa, Brazil, and many European countries. Recombinant viruses including genes derived from subtype C have been increasingly recognized in China, Thailand, and Taiwan, where phylogenetic studies indicate that complex BC subtype recombinants, such as circulating recombinant forms CRF_07 and CRF_08, comprise much of the current epidemics [2–4].

The predominance of a single clade of HIV-1 in the most severely affected countries in sub-Saharan Africa has been ascribed to a founder effect [5]. High levels of continued subtype C transmission are thought to be sustained by sexual-social factors, including low rates of male circumcision, the frequency of concurrent partnerships, increased viral load, and shedding of virus in a context of other sexually transmitted infections [6,7]. Comparisons with subtype B isolates, which predominate infections in the Americas and western Europe, have identified characteristics of subtype C viruses that may explain differences in infectivity, including enhanced tropism for macrophages and dendritic cells, elevated viral replication rates through transcriptional regulation [8], and significantly higher rates of mutation and emergence of drug resistance in women receiving single-dose nevirapine [9,10]. Studies of in-vitro replication rates of subtypes A, B, C, and D suggest lower pathogenic fitness but equivalent transmission efficiency of HIV-1 subtype C, suggesting a higher rate of transmission [11,12]. This may provide a partial, virologic explanation for the disproportionately high rates of HIV-1 infection in southern Africa, where a longer period of persistent infection and transmission preceding symptomatic disease could increase both the population prevalence and the reproductive rate of the epidemic.

The routine, population-based genotyping of circulating viruses, as a surveillance tool for drug resistance, has been exploited for evolutionary and phylogenetic mapping and for exploring the origins, molecular epidemiology, and genetic diversity of HIV-1 [13,14]. Analysis of spatiotemporally sampled sequence data enables the reconstruction of epidemic histories and estimation of demographic parameters, including measures of circulating viral diversity and population-level prevalence over time [15]. A number of studies have demonstrated the suitability of the HIV-1 pol gene for such phylogenetic and evolutionary analyses [16–18]. We analyzed subtype C pol sequences over a 15-year period between 1991 and 2006 obtained from successive cohorts of women screening for HIV infection in antenatal clinics in Harare, Zimbabwe. Using a combination of molecular clock analysis, to estimate the timescale of the epidemic, and a Bayesian coalescent-based approach, to infer demographic parameters of virus transmission, we present new information on the origins, timing, and epidemic growth patterns of subtype C HIV-1 during a period of in-migration and political change in Zimbabwe.

Materials and methods

Study population

Plasma samples were obtained from four studies of HIV infection and pregnancy in which HIV-positive women were enrolled at antenatal clinics in Harare, Zimbabwe (1991) and the neighboring suburb of Chitungwiza (1998, 2001, and 2006). Each cohort consisted of HIV-infected women enrolled in prevention of mother-to-child-transmission (pMTCT) studies approved by the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe and Stanford University. Samples were collected at 28–36 weeks of pregnancy before antiretroviral drugs were initiated for pMTCT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Samples from women testing positive for HIV-1 in antenatal clinics in Zimbabwe, 1991–2006.

| Cohort | WHO | SIDA | HPTN 023 | NIH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collection date | 1991 | 1998 | 2001 | 2006 |

| N samples | 39 | 56 | 26 | 56 |

| ARV exposure history | None | None | None | None |

| Study and sponsor | ‘Natural history of MTCT’ | ‘Feasibility of SC ZDV in pMTCT’ | ‘HIVNET 023 phase I study of SD NVP’ | ‘Drug resistance and pathogenesis in subtype C HIV-1’ |

| WHO | SIDA | NIH | NIH |

HPTN, HIV Prevention Trials Network; NIH, National Institutes of Health; pMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission; SC ZDV, short-course zidovudine; SD NVP, single dose nevirapine; SIDA, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency; WHO, World Health Organization. References for cohorts: WHO [20], SIDA [21], HPTN 023 [19], NIH [22].

Sequences

We obtained 177pol sequences from four sequential cohorts of young treatment-naive women presenting to antenatal clinics in Zimbabwe from 1991 to 2006. One dataset of HIV-1 subtype C pol used in this analysis was previously published (HPTN023 2001 [19]). Three additional datasets [WHO 1991 [20], Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) 1998 [21], National Institutes of Health (NIH) 2006 [22]] were created through bidirectional dideoxynucleotide sequencing of pol codons 1–213. For all datasets, RNA was isolated from plasmausing th eNuclisens Extraction Kit (Biomerieux, Durham, North Carolina, USA) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using random hexamer primers and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). We used a nested PCR amplification strategy employing first round PCR primers RT21(5′-CTGTATTTCTGCTAT TAA GTC TTT TGATGG G-3′) and MAW26 (5′-TTG GAA ATG TGG AAA GGA AGG AC-3′) and second round PCR primers RT20 (5′-CTG CCA GTT CTA GCT CTG CTT C-3′) and PRO-1 (5′-CAG AGC CAA CAG CCC CAC CA-3′). This was followed by direct sequencing of PCR products. Sequencing for all datasets was performed in the same laboratory using the ABI 377 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, California, USA). All Zimbabwe HIV-1C pol sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers GQ463284-GQ463434. Accession numbers for the previously published HPTN023 (2001) sequences are available in the reference publication [19].

Alignment

Sequences were aligned with ClustalW [23] and manually edited using BioEdit [24]. A large dataset of reference HIV-1 subtype C pol sequences (n = 981) was downloaded from the BioAfrica website (http://www.bioafrica.net/subtype/subC/) and used to characterize the relationship between the Zimbabwean sequences and other subtype C sequences worldwide. All alignments are available from the authors upon request.

Subtype classification

HIV-1 subtype was characterized for the Zimbabwean sequence datasets using the REGA Subtyping Tool v2.0 [25]. Evidence for intersubtype recombination was assessed with bootscanning analysis implemented in Simplot v3.5 [26].

Phylogenetic analysis

A best-fitting nucleotide substitution model for the Zimbabwean HIV-1 subtype C pol sequences was estimated using hierarchical likelihood ratio tests (hLRTs) implemented in the program Modeltest v3.7 [27] and manual examination in PAUP v4.0 [28]. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees were constructed using the inferred model, GTR + I + G, with the program PhyML v2.4. This method employs a neighbor-joining tree as a starting tree and implements the tree bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch-swapping algorithm to identify the final maximum likelihood tree. Support for internal nodes in the trees was obtained via parametric bootstrapping with 1000 replicates.

Evolutionary rate estimation and analysis

A coestimate of nucleotide substitution model parameters, phylogeny, and time to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) was obtained using the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method implemented in BEAST v1.4.8 [29]. The approximate marginal likelihoods were calculated for six coalescent demographic models. These included both parametric (constant population size, exponential growth) and nonparametric models (Bayesian skyline plot) with both a strict and relaxed (uncorrelated LogNormal prior) molecular clock. All analyses were performed using the best fitting model of nucleotide substitution as determined by Modeltest v3.7 [27].

For each demographic model, two independent runs of length 1.0 × 108 steps in the Markov chain were performed using BEAST and checked for convergence using Tracer v1.4 [30]. Samples of trees and parameter estimates were collected every 10 000 steps to build a posterior distribution of parameters. The estimated sample sizes (ESSs) for each run were more than 200, indicating sufficient mixing of the Markov chain and parameter sampling. When similar results were produced from the independent runs of the Markov chain, the log files were combined with the program LogCombiner v1.4.7 available in the BEAST package [29]. A final maximum clade credibility tree, the tree in the posterior sample with the maximum sum of posterior clade probabilities, was determined for each demographic model using TreeAnnotator v1.4.7. (A more detailed description of the parameters used in these analyses is available upon request as supplementary information.)

The program TreeStat v1.1 [31] was used to calculate the proportion of lineages that existed over 5-year intervals of 1980–1985, 1985–1990, and 1990–1995. This methodology utilized the posterior distribution of trees obtained previously in the Bayesian molecular clock analyses (as described by de Oliveira et al.) [32].

Model comparison

Model comparison in a Bayesian framework was achieved by calculating a measure known as the Bayes factor, which is the ratio of the marginal likelihoods of the two models being compared [33,34]. This flexible method enables the comparison of non-nested models [such as the non-parametric Bayesian skyline plot (BSP) vs. parametric constant or exponential demographic models] that cannot validly be compared using mean log posterior probabilities.

Results

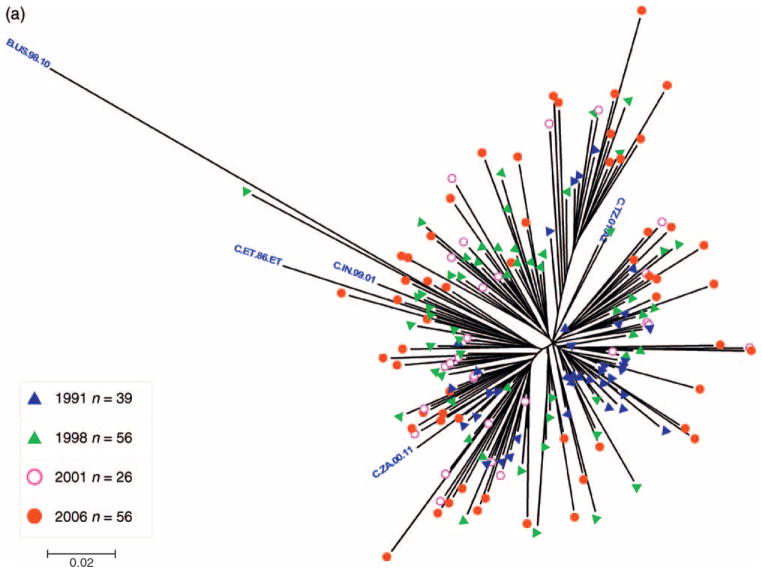

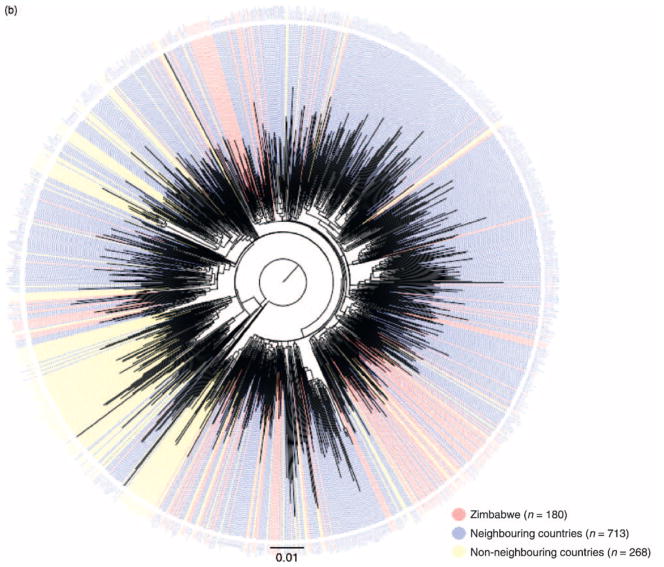

All 177 Zimbabwean HIV-1 pol sequences generated from samples collected between 1991 and 2006 were identified as subtype C with no evidence for intersubtype recombination, reflecting the predominance of this subtype in the HIV-1 epidemic in Harare. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree constructed from the Zimbabwe sequences demonstrated a clear relationship between sampling year and phylogenetic distance (branch length). For example, the earliest 1991 sequences were closest to and the recent 2006 sequences were most divergent from the MRCA node (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

(a) Midpoint-rooted maximum-likelihood tree of 177 HIV-1 subtype C pol sequences sampled from young women in Zimbabwe. The tree was constructed under the GTR + I + G model of evolution in PhyML using sequences sampled in Harare over a 15-year period between 1991 and 2006. Branches are color-tagged by sampling year and subtype reference strains from the Los Alamos HIV Sequence Database (www.hiv.lanl.gov) are labeled with blue text. (b) Maximum-likelihood tree showing the relationships among 1161 HIV-1 subtype C pol sequences sampled from various global locations. The tree contains sequences isolated from Zimbabwe (n= 180, including the present datasets); neighboring countries (n = 713), including sequences from Botswana, Mozambique, Malawi, South Africa, and Zambia; and non-neighboring countries (n = 268), including African, Asian, European, and South American sequences. The tree was constructed under the GTR + I + G model of evolution using PhyML. Intermingling of the 177 Zimbabwean pol sequences with HIV-1C sequences from neighboring countries indicates genetic similarity and a potential common origin with subtype C viruses in the sub-Saharan region. The complete sequence alignment and list of strains is available upon request as supplementary information.

To place the Zimbabwean sequences in the broader context of the subtype C pandemic and identify cross-epidemic relationships that could suggest common geographic origins, another maximum likelihood tree was constructed with the Zimbabwean sequences and an additional 981 subtype C pol reference sequences isolated from several other HIV-endemic countries (Fig. 1b). Most Zimbabwean sequences (158/177) were highly intermingled with sequences from neighboring African nations of South Africa, Botswana, Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique; very few Zimbabwean sequences (19/177) clustered with subtype C sequences isolated from individuals sampled in nonadjacent African countries of Tanzania and Somalia, or from Sweden, Denmark, Yemen, and India.

Evolutionary rate and origin of Zimbabwean epidemic

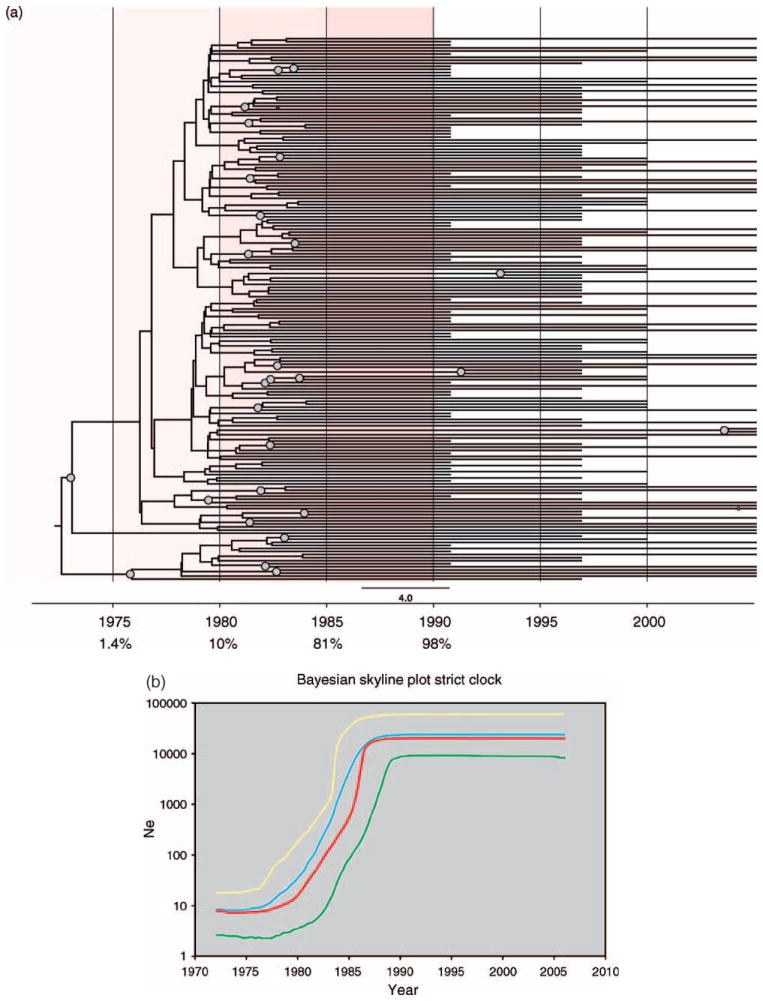

To identify the tMRCA and test hypotheses concerning the initial entry of HIV-1C into the Zimbabwean population, time-resolved phylogenetic trees were constructed under a Bayesian coalescent framework with BEAST (Fig. 2a). BEAST maximum clade credibility trees showed evidence for multiple independent introductions of subtype C HIV-1 into Zimbabwe between 1979 and 1981. Notably, as the Zimbabwean sequences were scattered among other sequences from neighboring countries in Fig. 1b, BEAST trees taken in this context support a scenario of multiple cross-border transmissions of HIV-1C with subsequent spread. However, a relatively modest statistical support for the major branches in these trees, which is expected given the relative genetic similarity of the Zimbabwe pol sequences, means that these findings should be taken with caution and considered alongside other evidence.

Fig. 2.

(a) Bayesian maximum clade-credibility tree for HIV-1C pol in Zimbabwe. Maximum clade-credibility trees were estimated using BEAST from a posterior distribution of 10 000 Bayesian trees employing constant population size, exponential growth, and Bayesian skyline plot (BSP) coalescent tree priors and enforcing either a strict or relaxed molecular clock (BSP relaxed clock shown). Nodes with greater than 0.5 posterior probability are marked with gray circles. The estimated median percentage of present-day (2006) strains in Zimbabwe that were present in 1975, 1980, 1985, and 1990 is indicated in the tree, with red highlighting marking the time period during which the highest increase in HIV subtype C strain diversity was recorded in Zimbabwe. (b) Bayesian skyline plot of HIV-1C pol demographic growth patterns in Zimbabwe. Nonparametric estimates of HIV-1 effective population size (Ne) over time were estimated from 177 Zimbabwean pol sequences employing a Bayesian Skyline plot coalescent tree prior in BEAST. The X-axis represents year and the Y-axis represents HIV-1 effective population size (effective number of infections, Ne; log10 scale). The red line marks the median estimate for Ne and yellow and green lines represent the upper and lower 95% highest posterior density (HPD) estimates, respectively.  , Bayesian skyline;

, Bayesian skyline;  , median;

, median;  , upper;

, upper;  , lower

, lower

The estimated nucleotide substitution rates and tMRCA dates for the Zimbabwe pol sequences obtained under the six different evolutionary models of population growth are presented in Table 2. All parameter estimates were highly consistent across the different evolutionary models, and replicate runs of the same model produced almost-identical results. The mean rate of 2.33 × 10−3 nucleotide substitutions/site per year produced an average estimate of the date of origin of the HIV-1C pol sequences in the year 1972 (highest posterior density, HPD: 1969–1974). Given the wide dispersion of the Zimbabwean sequences among regional strains in Fig. 1b, this tMRCA date approximates the date of origin of regionally circulating subtype C viruses, including those that gave rise to the Zimbabwean epidemic. The median estimates of the coefficient of variation parameter were 0.43, 0.24, and 0.25 for the constant, exponential, and Bayesian skyline relaxed clock analyses respectively, indicating relatively little variation in evolutionary rates among branches in the tree irrespective of the evolutionary model employed. Estimates of the Bayes factor (see Methods – Model comparison) for the HIV-1C pol dataset supported models enforcing a relaxed clock over a strict clock and population growth models over a constant population size model. In turn, a relaxed clock exponential growth parametric model was statistically supported over the nonparametric BSP model (Table 3). (More detailed estimates of evolutionary parameters are available from the authors upon request).

Table 2.

Bayesian estimates of mean time to the most common ancestor, mean nucleotide substitution rates, and percentage lineages at selected time periods for HIV-1C pol in Zimbabwe.

| Expo-strict clock | Expo-relaxed clock | BSP-strict clock | BSP-relaxed clock | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tMRCA | 1973.638 | 1974.078 | 1971.831 | 1972.035 |

| 95% HPD lower | 1977.702 | 1978.246 | 1977.487 | 1978.175 |

| 95% HPD upper | 1969.578 | 1969.371 | 1965.799 | 1965.062 |

| Subst. rate | 0.002068 | 0.00206 | 0.002186 | 0.002192 |

| 95% HPD lower | 0.001729 | 0.001664 | 0.001834 | 0.001791 |

| 95% HPD upper | 0.00241 | 0.002456 | 0.002555 | 0.002597 |

| % Strains in 1975 | 1.861 | 1.861 | 1.406 | 1.406 |

| 95% HPD lower | 0.565 | 0.565 | 0.565 | 0.565 |

| 95% HPD upper | 5.65 | 5.65 | 2.26 | 2.26 |

| % Strains in 1980 | 20.7 | 20.7 | 10.1 | 10.1 |

| 95% HPD lower | 1.695 | 1.695 | 1.13 | 1.13 |

| 95% HPD upper | 47.5 | 47.5 | 31.6 | 31.6 |

| % Strains in 1985 | 82.9 | 82.9 | 81.3 | 81.3 |

| 95% HPD lower | 63.8 | 63.8 | 55.4 | 55.4 |

| 95% HPD upper | 96.6 | 96.6 | 98.3 | 98.3 |

| % Strains in 1990 | 98.5 | 98.5 | 97.8 | 97.8 |

| 95% HPD lower | 97.7 | 97.7 | 96 | 96 |

| 95% HPD upper | 99.4 | 99.4 | 98.3 | 98.3 |

The table contains the mean time to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA), the estimated mean substitution rate (nucleotide substitutions/site/year), and the median percentage of strains present at selected time periods for clade HIV-1C in Zimbabwe. Percentage strains represent the proportion of strains sampled in 2006 estimated to have existed at 5-year time intervals throughout the epidemic period in Zimbabwe. The 95% lower and upper highest posterior density (HPD) intervals are shown. The tMRCA and substitution rate estimates were calculated using BEAST under exponential (Expo) and Bayesian skyline plot (BSP) demographic growth models assuming both a strict and relaxed molecular clock. Lineage estimations were calculated from the posterior distribution of Bayesian trees using TreeStat.

Table 3.

Bayes factor comparisons between different evolutionary models for HIV-1C pol in Zimbabwe.

| Model comparison | log10 Bayes factor | Evidence against Ho |

|---|---|---|

| Const Strict (H0) vs. relaxed (H1) clock | 27.732 | Very strong |

| Expo Strict (H0) vs. relaxed (H1) clock | 19.496 | Very strong |

| BSP Strict (H0) vs. relaxed (H1) clock | 17.736 | Very strong |

| Const (H0) vs. Expo (H1) relaxed clock | 0.86 | Positive |

| Const (H0) vs. BSP (H1) relaxed clock | 3.694 | Very strong |

| BSP (H0) vs. Expo (H1) relaxed clock | 4.554 | Very strong |

BF, Bayes factor is the difference (in log space) of the marginal likelihood of the null (H0) and alternative (H1) models. BFs were estimated by comparing the approximate marginal likelihoods of the different models given in Table 3. Const, constant population size; Expo, exponential population growth; BSP, Bayesian skyline plot; Strict, strict molecular clock; Relaxed, relaxed molecular clock.

Specification of a BSP coalescent tree prior enables the estimation of effective population size (Ne) through time directly from sequence data. Our reconstruction of the demographic history of HIV-1C in Zimbabwe through the BSP analysis identified three epidemic growth phases: an initial, slow growth phase in 1974–1976, followed by an exponential growth phase in 1979–1984, and an asymptotic phase approaching the present time (Fig. 2b). The most rapid increase in the curve occurred during 1979–1981, reflecting a logarithmic expansion in Ne, or effective number of infections, over this short-time period. Estimates indicated an initial median value of eight effective infections (95% HPD 3–18) around 1972, whereas final estimates in the year 2006 were approximately 20 115 effective infections (95% HPD 8334–61 200). Sequence diversity was estimated within each cohort by calculating average pairwise nucleotide distances using the HKY + G model of nucleotide substitution in Phylip v3.6 implemented in BioEdit. Consistent with the results of the BSP model, mean sequence diversity significantly increased from 1991 to 1998 (P < 0.0001), from 2001 to 2006 (P < 0.0001), and over the entire 15-year period (P < 0.0001), calculated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; Supplementary Figure S1).

In addition to estimating changes in Ne through time using a BSP, we also calculated the median proportion of current lineages that existed during 1980–1985, 1985–1990, and 1990–1995 (see Methods – Evolutionary Rate Estimation and Analysis). The results showed that for four of the six evolutionary models (expo-strict clock, expo-relaxed clock, BSP-strict clock, and BSP-relaxed clock), approximately 80% of the lineages were already present in Zimbabwe by 1985 (ranging from 55.4 to 98.3%; Table 2).

Discussion

The persistence and rapid increase of HIV-1C infection in much of southern Africa has been attributed largely to heterosexual transmission. This is certainly true of Zimbabwe, where continued heterosexual transmission underlies a generalized HIV-1 epidemic with relatively high population prevalence, particularly among young women. In the present investigation, phylogenetic analysis of pol sequences from cohorts of young women sampled from 1991 to 2006 confirms the predominance of subtype C infection in the Zimbabwean HIV-1 epidemic. Our demographic and evolutionary reconstruction of the Zimbabwean epidemic suggests that multiple closely-related subtype C viruses with a common ancestor originating in the early 1970s entered the country in the early 1980s, followed by an explosive growth in effective number of infections over the next decade.

Indeed, similar scenarios of multiple HIV-1C introductions have been previously suggested in a number of southern African nations [35–37]. However, a rapid and disproportionate dissemination of HIV in Zimbabwe in the 1980s relative to neighboring countries is reflected in UNAIDS estimates from serosurveillance programs. In 1990, national HIV prevalence rates among adults aged 15–45 in southern African nations varied from 14.2% in Zimbabwe compared with 8.9% in Zambia, 4.7% in Botswana, 2.1% in Malawi, less than 2% in Namibia and Mozambique, and less than 1% in South Africa and Swaziland [38].

The origin and timing of the rapid epidemic expansion in Zimbabwe may be partly explained by the political and military history of the region. From 1953 to 1963, migration of populations in southern Africa was facilitated by a pre-existing colonial infrastructure, in which Zimbabwe (Southern Rhodesia), Zambia (Northern Rhodesia), and Malawi (Nyasaland) were politically and economically merged as the Central African Federation. In 1965, in response to the end of colonial rule and the independence of Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), the Southern Rhodesian government issued a unilateral declaration of independence to maintain minority rule and denial of majority rights. This led to a prolonged civil conflict throughout the 1970s between the self-declared Rhodesian government and Black Nationalist liberation groups, during which movement in and out of Rhodesia was severely constrained by international sanctions and government restrictions. The conflict in Zimbabwe ended with the Lancaster House Agreement in December 1979, followed by the return of exiled liberation forces. Thus, in 1980, tens of thousands of expatriates and liberation fighters returned from adjoining southern African countries to a newly independent Zimbabwe.

Our phylogenetic and evolutionary analyses of HIV-1C in the region reflect these historical events. The clustering of nearly 90% of Zimbabwean sequences with sequences from adjacent southern African countries (Fig. 1b) suggests a regional origin and localized expansion of the subtype C epidemic in Zimbabwe. The subsequent rapid increase of HIV-1C following Zimbabwean independence in the early 1980s, reflected in the high seroprevalence of infection in 1990 outpacing infection rates in neighboring countries [38], is consistent with our retrospective reconstruction and Bayesian estimates of HIV-1 growth, with 98% of the current lineages present in Zimbabwe by 1990 (Fig. 2a). This exponential growth of the Zimbabwean epidemic over a period of less than a decade in the 1980s provides an example of in-migration of a small number of ancestors (founders) and subsequent amplification during a period of heightened political and demographic change.

Rapid epidemic expansion in Zimbabwe in the 1980s, as we have estimated by calculating effective number of infections in a coalescent framework, is supported by three independent sources estimating historical HIV prevalence within the country: blood donor screening, antenatal surveillance, and back-calculation of incidence from mortality statistics. The first clinical case of AIDS in Zimbabwe was documented in 1985, the same year that diagnostic screening for donated blood units was initiated by the Zimbabwe National Blood Transfusion Service (NBTS). Our estimated increase in HIV-1C prevalence corresponds well with NBTS records, which documented a near doubling in seroprevalence among blood donors each year from 1986 to 1990 [39]. Our estimates also mirror WHO sentinel surveillance data, which document a rapidly increasing prevalence among antenatal women and the general population through the early 1990s [38]. Notably, our demographic estimates indicate a peak in the number of infections between 1989 and 1991. Epidemiologic modeling studies back-calculating HIV incidence from mortality statistics estimate a likely peak in incidence in Harare during the same period between 1988 and 1990 [40]. These independent approaches paint a remarkably similar picture, each identifying a period of rapid, peaking expansion of HIV-1C in Zimbabwe in the 1980s. Potential explanations for the observed slowing in the rate of the epidemic after 1990 include a decrease in the number of susceptible individuals, reducing the epidemic reproductive rate, as well as a 6-year nationwide drought, which heightened food insecurity and decreased overall economic output in Zimbabwe [41,42].

Analysis of population demographics using Bayesian coalescent methods has a number of limitations. The presence of recent (slightly) deleterious mutations, which have not yet been eliminated at the population level by purifying selection, would result in an overestimation of the time to the most recent ancestor in the tree [43]. Moreover, all phylogenetic trees contain inherent uncertainty, including variable substitution rates between viral lineages and possible differences in the demographic history of included viruses. Although Bayesian MCMC methods robustly incorporate this uncertainty, inferences based on such trees should be taken with caution and considered alongside other supporting evidence. The present analyses may also be limited by an exclusive focus on HIV isolated from cohorts of pregnant women, in whom infection was identified through antenatal screening. In sub-Saharan Africa, young women comprise a demographic group with a high risk of infection in association with patterns of sequential overlapping partnerships, intergenerational sex, and low condom usage [44]. Recent studies and surveillance data from Zimbabwe have provided encouraging evidence that gradual behavioral changes have reduced the prevalence among 18–24-year-old women from more than 25% to about 20%, suggesting that incidence in this vulnerable group has declined since 1998 [38,45]. This is consistent with our Bayesian estimates of a steady-state prevalence as the number of effective infections reaches an asymptotic phase approaching the present time (Fig. 2b). However, it has been noted that all BSPs show some signal of steady-state dynamics approaching the present that may be partly attributed to within-host evolution [43]. Moreover, like recent surveillance studies, our findings cannot rule out the possibility that the observed decrease in HIV-1 prevalence may be due, in part, to selective AIDS-induced mortality rates, especially given the disruptions in health infrastructure introduced by political volatility in Zimbabwe.

We have focused our analyses exclusively on pol as these are the most routinely available sequences in sub-Saharan Africa and provide the largest possible reference dataset of regional subtype C sequences. The ongoing WHO focus on global HIV drug resistance surveillance (HIVResNet) based on pol sequence datasets will provide an expanding resource to track the evolution of the subtype C epidemic. We note, however, that estimates of evolutionary parameters obtained with any single molecular marker should be taken cautiously and should be validated with alternative viral genes and sample collections. We believe our dataset of Zimbabwe sequences to be the most comprehensive available and through comparative analysis, may provide a basis for understanding the role of migration and evolution as drivers of the epidemic.

Large-scale migration in response to political and economic instability is just as evident in Zimbabwe today. The recent cholera epidemic, spiraling inflation, and political turmoil are limiting disease prevention services and treatment and escalating out-migration to neighboring countries. The political and economic displacement of millions of individuals from Zimbabwe poses further challenges to regional programs operating in the context of a generalized HIV-1 epidemic in southern Africa. These programs urgently need to expand testing, prevention, and treatment services for HIV and other infectious diseases to reach migratory and displaced populations in a rapidly changing political and economic environment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all study participants in Harare and Chitungwiza, Zimbabwe. The authors wish to thank Keyan Salari and Lee Riley for critical reading of the manuscript. This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health. S.D., S.K., and D.K. were supported by the NIH R01 Program (award R01 AI060399-04). J.M. was supported by the NIH Fogarty International Center through the International Clinical, Operational and Health Services and Training Award (ICOHRTA award U2R TW006878-4). T.d.O. was supported by the South African Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust (082384/Z/07/Z). G.H. was supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa and the Atlantic Philanthropies Grant (number 62302). S.D. was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Research Fellowship and the Paul and Daisy Soros Fellowship for New Americans.

Footnotes

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

S.D. conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. T.d.O. and G.H. provided critical revisions for the manuscript. S.D., T.d.O., and G.H. implemented the phylogenetic and coalescent analyses. S.D., S.K., J.L., and J.M. performed genotypic sequencing. E.J. provided technical assistance for laboratory methods and genotyping. D.K. provided historical information for the region and critical revisions for the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hemelaar J, Gouws E, Ghys PD, Osmanov S. Global and regional distribution of HIV-1 genetic subtypes and recombinants in 2004. AIDS. 2006;20:W13–23. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247564.73009.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin YT, Lan YC, Chen YJ, Huang YH, Lee CM, Liu TT, et al. Molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 infection and full-length genomic analysis of circulating recombinant form 07_BC strains from injection drug users in Taiwan. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1283–1293. doi: 10.1086/513437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su L, Graf M, Zhang Y, von Briesen H, Xing H, Köstler J, et al. Characterization of a virtually full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genome of a prevalent intersubtype (C/B′) recombinant strain in China. J Virol. 2000;74:11367–11376. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11367-11376.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watanaveeradej V, DeSouza MS, Benenson MW, Sirisopana N, Nitayaphan S, Chanbancherd P, et al. Subtype C/CRF01_AE recombinant HIV-1 found in Thailand. AIDS. 2003;17:2138–2140. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309260-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rambaut A, Posada D, Crandall KA, Holmes EC. The causes and consequences of HIV evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:52–61. doi: 10.1038/nrg1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halperin DT, Bailey RC. Male circumcision and HIV infection: 10 years and counting. Lancet. 1999;354:1813–1815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen MS. Preventing sexual transmission of HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45 (Suppl 4):S287–S292. doi: 10.1086/522552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montano MA, Novitsky VA, Blackard JT, Cho NL, Katzenstein DA, Essex M. Divergent transcriptional regulation among expanding human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes. J Virol. 1997;71:8657–8665. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8657-8665.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eshleman SH, Hoover DR, Chen S, Hudelson SE, Guay LA, Mwatha A, et al. Nevirapine (NVP) resistance in women with HIV-1 subtype C, compared with subtypes A and D, after the administration of single-dose NVP. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:30–36. doi: 10.1086/430764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassaye S, Lee E, Kantor R, Johnston E, Winters M, Zijenah L, et al. Drug resistance in plasma and breast milk after single-dose nevirapine in subtype C HIV type 1: population and clonal sequence analysis. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:1055–1061. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ball SC, Abraha A, Collins KR, Marozsan AJ, Baird H, Quinones-Mateu ME, et al. Comparing the ex vivo fitness of CCR5-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates of subtypes B and C. J Virol. 2003;77:1021–1038. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1021-1038.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraha A, Nankya IL, Gibson R, Demers K, Tebit DM, Johnston E, et al. CCR5- and CXCR4-tropic subtype C HIV-1 isolates have lower pathogenic fitness as compared to the other dominant group M subtypes: implications for the epidemic. J Virol. 2009 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02051-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gifford RJ, de Oliveira T, Rambaut A, Pybus OG, Dunn D, Vandamme AM, et al. Phylogenetic surveillance of viral genetic diversity and the evolving molecular epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2007;81:13050–13056. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00889-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korber B, Muldoon M, Theiler J, Gao F, Gupta R, Lapedes A, et al. Timing the ancestor of the HIV-1 pandemic strains. Science. 2000;288:1789–1796. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salemi M, De Oliveira T, Ciccozzi M, Rezza G, Goodenow M. High-resolution molecular epidemiology and evolutionary history of HIV-1 subtypes in Albania. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hue S, Clewley JP, Cane PA, Pillay D. HIV-1 pol gene variation is sufficient for reconstruction of transmissions in the era of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2004;18:719–728. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403260-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hué S, Pillay D, Clewley JP, Pybus OG. Genetic analysis reveals the complex structure of HIV-1 transmission within defined risk groups. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4425–4429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407534102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tee KK, Pybus OG, Li XJ, Han X, Shang H, Kamarulzaman A, Takebe Y. Temporal and spatial dynamics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 circulating recombinant forms 08_BC and 07_BC in Asia. J Virol. 2008;82:9206–9215. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00399-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shetty AK, Coovadia HM, Mirochnick MM, Maldonado Y, Mofenson LM, Eshleman SH, et al. Safety and trough concentrations of nevirapine prophylaxis given daily, twice weekly, or weekly in breast-feeding infants from birth to 6 months. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34:482–490. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200312150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katzenstein DA, Mbizvo M, Zijenah L, Gittens T, Munjoma M, Hill D, et al. Serum level of maternal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) RNA, infant mortality, and vertical transmission of HIV in Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1382–1387. doi: 10.1086/314767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mateta P, Stranix L, Moyo S, Nyoni N, Mhazo M, von Lieven A, et al. Feasibility of preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Zimbabwe [ B10499]. XIV International AIDS Conference; Barcelona, Spain. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manasa J, Kassaye S, Dalai S, Kadzirange G, Zijenah L, Johnston E, et al. HIV-1 subtype C drug resistance surveillance among young treatment naive pregnant women in Chitungwiza, Zimbabwe (2006–2007). XVII International AIDS Conference; Mexico City, Mexico. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall T. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Oliveira T, Deforche K, Cassol S, Salminen M, Paraskevis D, Seebregts C, et al. An automated genotyping system for analysis of HIV-1 and other microbial sequences. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3797–3800. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ray S. Simplot v3.5.1. Available from http://sray.med.som.jhmi.edu/SCRoftware/simplot/

- 27.Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swofford DL. PAUP: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (* and Other Methods) Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. Tracer v1.4. 2007 http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer.

- 31.Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. TreeStat v1.1: tree statistic calculation tool. 2005 http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/treestat/

- 32.De Oliveira T, Pybus OG, Rambaut A, Salemi M, Cassol S, Ciccozzi M, et al. Molecular epidemiology: HIV-1 and HCV sequences from Libyan outbreak. Nature. 2006;444:836–837. doi: 10.1038/444836a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kass R, Raftery A. Bayes factors. J Am Statis Assoc. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suchard MA, Weiss RE, Sinsheimer JS. Bayesian selection of continuous-time Markov chain evolutionary models. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:1001–1013. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gordon M, de Oliveira T, Bishop K, Coovadia HM, Madurai L, Engelbrecht S, et al. Molecular characteristics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C viruses from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: implications for vaccine and antiretroviral control strategies. J Virol. 2003;77:2587–2599. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2587-2599.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCormack GP, Glynn JR, Crampin AC, Sibande F, Mulawa D, Bliss L, et al. Early evolution of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C epidemic in rural Malawi. J Virol. 2002;76:12890–12899. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12890-12899.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Batra M, Tien PC, Shafer RW, Contag CH, Katzenstein DA. HIV type 1 envelope subtype C sequences from recent seroconverters in Zimbabwe. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2000;16:973–979. doi: 10.1089/08892220050058399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimbabwe National Blood Transfusion Service H. Annual Reports. 1985–1990 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopman B, Gregson S. When did HIV incidence peak in Harare, Zimbabwe? Back-calculation from mortality statistics. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richardson CJ. How much did droughts matter? Linking rainfall and GDP growth in Zimbabwe. Afr Aff (Lond) 2007;106:463–478. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marquette CM. Current poverty, structural adjustment, and drought in Zimbabwe. World Dev. 1997;25:1141–1149. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lemey P, Rambaut A, Pybus OG. HIV evolutionary dynamics within and among hosts. AIDS Rev. 2006;8:125–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hallett TB, Aberle-Grasse J, Bello G, Boulos LM, Cayemittes MPA, Cheluget B, et al. Declines in HIV prevalence can be associated with changing sexual behaviour in Uganda, urban Kenya, Zimbabwe, and urban Haiti. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82:i1–i8. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.016014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gregson S, Garnett GP, Nyamukapa CA, Hallett TB, Lewis JJ, Mason PR, et al. HIV decline associated with behavior change in eastern Zimbabwe. Science. 2006;311:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.1121054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.