Abstract

Angiogenin is a 14 kDa protein originally identified as an angiogenic protein. Recent development has shown that angiogenin acts on both endothelial cells and neuronal cells. Loss-of-function mutations in the coding region of the ANG gene have recently been identified in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Angiogenin has been shown to control motor neuron survival and protect neurons from apoptosis under various stress conditions. In this article, we characterize the anti-apoptotic activity of angiogenin in pluripotent P19 mouse embryonal carcinoma cells. Angiogenin prevents serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis. Angiogenin upregulates anti-apoptotic genes, including Bag1, Bcl-2, Hells, Nf-κb and Ripk1, and downregulates pro-apoptotic genes, such as Bak1, Tnf, Tnfr, Traf1 and Trp63. Knockdown of Bcl-2 largely abolishes the anti-apoptotic activity of angiogenin, whereas the inhibition of Nf-κb activity results in a partial, but significant, inhibition of the protective activity of angiogenin. Thus, angiogenin prevents stress-induced cell death through both the Bcl-2 and Nf-κb pathways.

Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, angiogenin, apoptosis

Angiogenin (ANG) was originally identified as a tumor angiogenic molecule from the conditioned medium of HT-29 colon adenocarcinoma cells [1]. Its expression is upregulated in a variety of human cancers [2], where it plays a dual role in cancer progression by stimulating both tumor angiogenesis and cancer cell proliferation [3]. ANG has a wide tissue distribution and is expressed by virtually every organ and tissue [4], suggesting that it may have a more universal function than the mediation of angiogenesis. Mechanistic studies have demonstrated that ANG stimulates Erk1/2 and SPAK/JNK phosphorylation [5,6], as well as AKT activation [7]. More significantly, ANG is translocated to the nucleus, where it accumulates and binds to the promoter region of rDNA and stimulates rRNA transcription [8–10]. As rRNA transcription is essential for ribosome biogenesis and protein translation, ANG has been conceived to play an important role in cell survival, growth and proliferation. Consistently, in addition to cancer, abnormal ANG expression has been associated with numerous disorders, including diabetes mellitus, asthma, chronic heart failure, endometriosis and hypertension.

Since 2006, missense mutations in the coding region of ANG genes have been identified in patients with both familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [11–18]. ANG appears to be the first loss-of-function gene mutation ever identified in patients with ALS [17,19], suggesting that it may play an important role in motor neuron physiology. Mouse ANG protein is strongly expressed in the central nervous system during development [20]. Human ANG protein is strongly expressed in both endothelial cells and motor neurons of normal human fetal and adult spinal cord [17]. ANG has also been shown to stimulate neurite outgrowth and pathfinding of motor neurons derived from P19 mouse pluripotent embryonal carcinoma cells. It also protects against hypoxia-induced motor neuron degeneration, whereas ALS-associated mutant ANG proteins lack these activities [21]. Moreover, ANG has been shown to prevent motor neuron death induced by excitotoxicity, endoplasmic reticulum stress and hypoxia [20,22,23]. Most dramatically, the systemic administration of ANG into ALS model animals (SOD1G93A mice) enhances significantly the motormuscular function and prolongs the survival of these mice [22]. In order to understand how ANG elicits its anti-apoptotic function, we characterized its effect on the three known apoptotic pathways.

Results

ANG prevents P19 cells from serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis

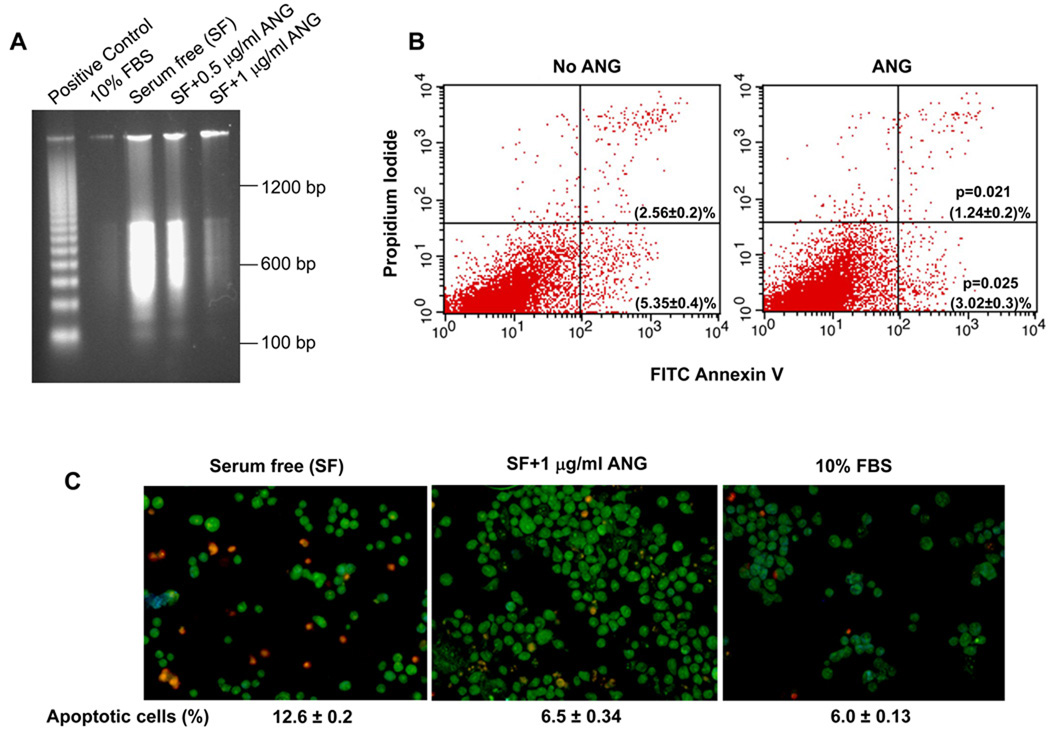

P19 cells are mouse pluripotent embryonal carcinoma cells that possess stem cell-like properties with the ability to both self-renew and differentiate into various types of neural cell [24,25]. These cells have been used extensively in the investigation of the behavior of neuronal cells [26]. Trophic factor withdrawal has been hypothesized to be one of the underlying causes of motor neuron death in ALS. We therefore attempted to elucidate the pathways of P19 cells during apoptosis on serum deprivation. Figure 1A shows that robust DNA fragmentations occurred when the cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 18 h (Fig. 1A, lane 3), indicating that the cells underwent apoptosis. ANG prevented serum deprivation-induced DNA fragmentation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A, lanes 4 and 5).

Fig. 1.

ANG prevents serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis of P19 cells. (A) DNA fragmentation analysis. Cells were cultured in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) or in serum-free medium with the indicated concentration of ANG for 18 h. DNA was extracted and analyzed using the Apoptotic DNA Ladder Kit. The positive control included in the kit was the DNA fragments from apoptotic U937 cells. (B) Flow cytometry of FITC–Annexin. Cells were cultured in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of ANG (0.5 µg·mL−1) for 18 h, and analyzed using the FITC–Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I. Cells cultured in 10% fetal bovine serum were used to set the cut-off value of propidium iodide and Annexin–FITC staining. (C) EB/AO staining. Cells were cultured in 10% fetal bovine serum or in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of ANG for 18 h. Cells were collected, stained with EB/AO and applied to a microscope slide for imaging. EB-stained (apoptotic) cells were counted in a total of 750 cells from five randomly selected areas of each slide, and the percentage of apoptotic cells is shown at the bottom of the image. The data shown are the means and standard errors of triplicates of a representative experiment of at least three repeats.

Next, we analyzed the cells for loss of plasma membrane asymmetry and permeability by Annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI) staining, respectively. Annexin V stains for early apoptotic cells by binding to phosphatidylserine, which is exposed to the outer leaflets from its normal position in the inner leaflets of the lipid bilayer as a result of early events in apoptosis. PI stains for DNA when the plasma membrane becomes permeable in late apoptotic cells. Flow cytometric analysis showed that early and late apoptotic cells were present at 5.35 ± 0.4% and 2.56 ± 0.2% in the absence of ANG (Fig. 1B, left panel), decreasing to 3.02 ± 0.3% (P = 0.025) and 1.24 ± 0.2% (P = 0.021) in the presence of ANG. Thus, ANG treatment resulted in a decrease in early and late apoptotic cells by 44% and 52%, respectively. When early and late apoptotic cells were combined, ANG decreased the percentage of apoptotic cells from 7.91% to 4.26%, representing a 46% inhibition of apoptosis.

To confirm the above findings, the cells were also subjected to ethidium bromide (EB) and acridine orange (AO) staining (Fig. 1C). AO permeates intact cells and stains all nuclei green, whereas EB enters cells only when the integrity of the plasma membrane is lost, and thus stains apoptotic nuclei red. This method has been used widely to visually distinguish apoptotic cells [27]. The proportions of EB-stained cells were 12.6 ± 0.2 % and 6.0 ± 0.13% in the absence and presence of fetal bovine serum, respectively (Fig. 1C). When the cells were cultured in the absence of fetal bovine serum, but in the presence of ANG, the percentage of apoptotic cells was 6.5 ± 0.34% (Fig. 1C), indicating that ANG has an equivalent anti-apoptotic activity to fetal bovine serum. Thus, all three methods showed that ANG prevented significantly the apoptosis of P19 cells induced by serum withdrawal.

ANG regulates the expression of apoptosis-related genes

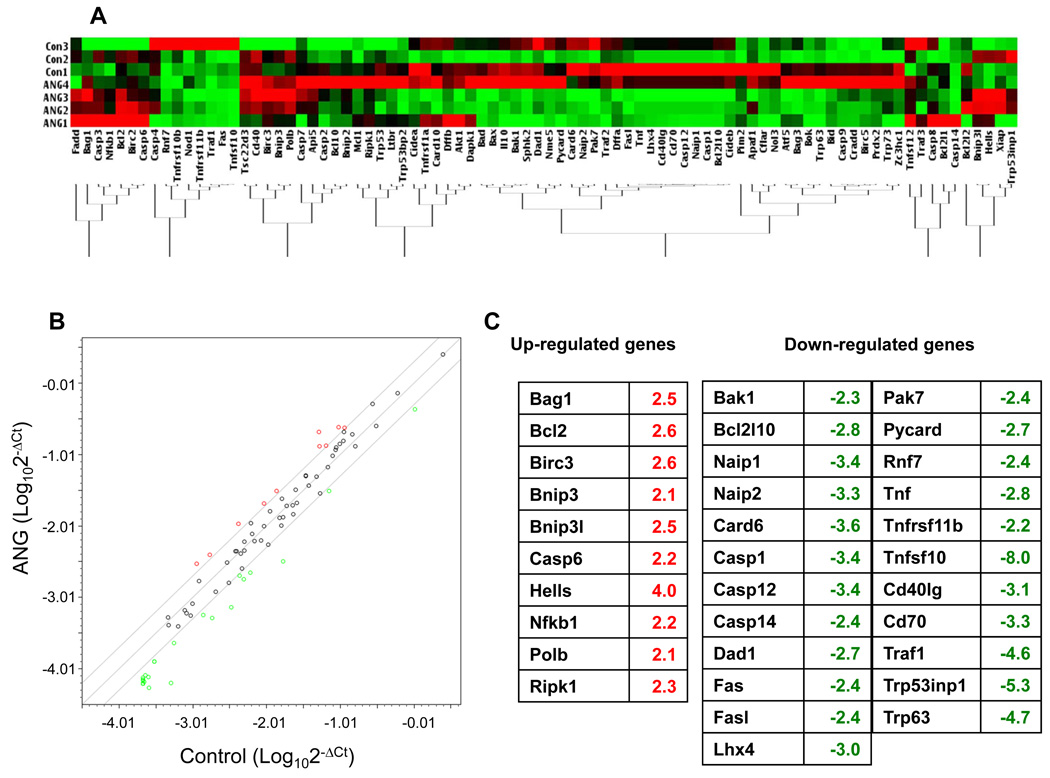

As a first step to an understanding of the mechanism by which ANG elicits its anti-apoptotic activity, we examined the effect of ANG on the expression of genes known to play a role in apoptosis pathways. The Apoptosis PCR Array Kit from SABiosciences was used for this purpose. Figure 2A shows a heat map of the gene expression profiles from three controls (in the absence of ANG) and four samples (in the presence of ANG). Each array was normalized by the expression levels of the five housekeeping genes (actin, Gapdh, Hsp90, Gusb and Hprt1). The mean of the normalized ΔCt value of each gene from the control and experimental groups was plotted to identify the differentially expressed genes (Fig. 2B). Among the 10 upregulated genes (Fig. 2C, left panel), seven (Bag1, Bcl-2, Birc3, Hells, Nfkb1, Polb, Ripk1) are known to have anti-apoptotic function. Three pro-apoptotic genes (Bnip3, Bnip3L, caspase 6) were also upregulated. The reasons and consequences of their upregulation are currently unknown. Among the upregulated genes, Ripk1 is biofunctional. It is essential for tumor necrosis factor receptor (Tnfr)-mediated apoptosis, but can also activate nuclear factor-κb (Nf-κb), thereby inhibiting apoptosis [28]. The pro-apoptotic activity of Ripk1 is mediated by caspase 8 [29]. However, we did not detect any changes in either the mRNA or protein levels of caspase 8 between control and ANG-treated groups (data not shown). In contrast, Ikk-α and Ikk-β, the downstream effector of Ripk1 and upstream mediator of Nf-κb, were upregulated. Therefore, the upregulation of Ripk1 by ANG treatment is more likely to elicit an anti-apoptotic effect. Twenty-three genes were downregulated by ANG (Fig. 2C, right panels), at least 16 of which are known to be pro-apoptotic. The functions of the remaining eight genes (Bcl2l10, Naip1, Naip2, Dad1, Lhx4, Pak7 and Cd40lg) are controversial and may be context dependent. Thus, the apoptosis PCR array analysis revealed a pattern of ANG-regulated gene expression in which the anti-apoptotic genes were generally upregulated and the pro-apoptotic genes were generally downregulated. These results provide a reasonable explanation for the protective function of ANG towards serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis of P19 cells.

Fig. 2.

Effect of ANG on the expression of apoptosis-related genes. Cells were cultured in serum-free medium in the absence (n = 3) or presence (n = 4) of ANG for 18 h. Total RNA was extracted by Trizol reagent and used for array analysis with the Apoptosis PCR Array Kit. (A) Clustergram showing the clustering of 84 apoptosis-related genes from untreated and ANG-treated groups. The expression levels of the five housekeeping genes (actin, Gapdh, Hsp90, Gusb and Hprt1) were used as normalization controls. (B) Scatter plot showing the correlation of gene expression in the untreated and ANG-treated groups. The x- and y-axes are the ΔCt values of the untreated and ANG-treated groups, respectively, on a logarithmic scale. A threshold of a twofold difference in the adjusted normalized ΔCt values was used to determine whether or not a gene was differentially expressed. The two lines above and beneath the diagonal line mark the twofold difference in gene expression. The up- and downregulated genes are shown in red and green, respectively. (C) List of up- and downregulated genes in ANG-treated groups.

ANG increases Bcl-2 protein level, stimulates cytochrome c release and decreases caspase activity

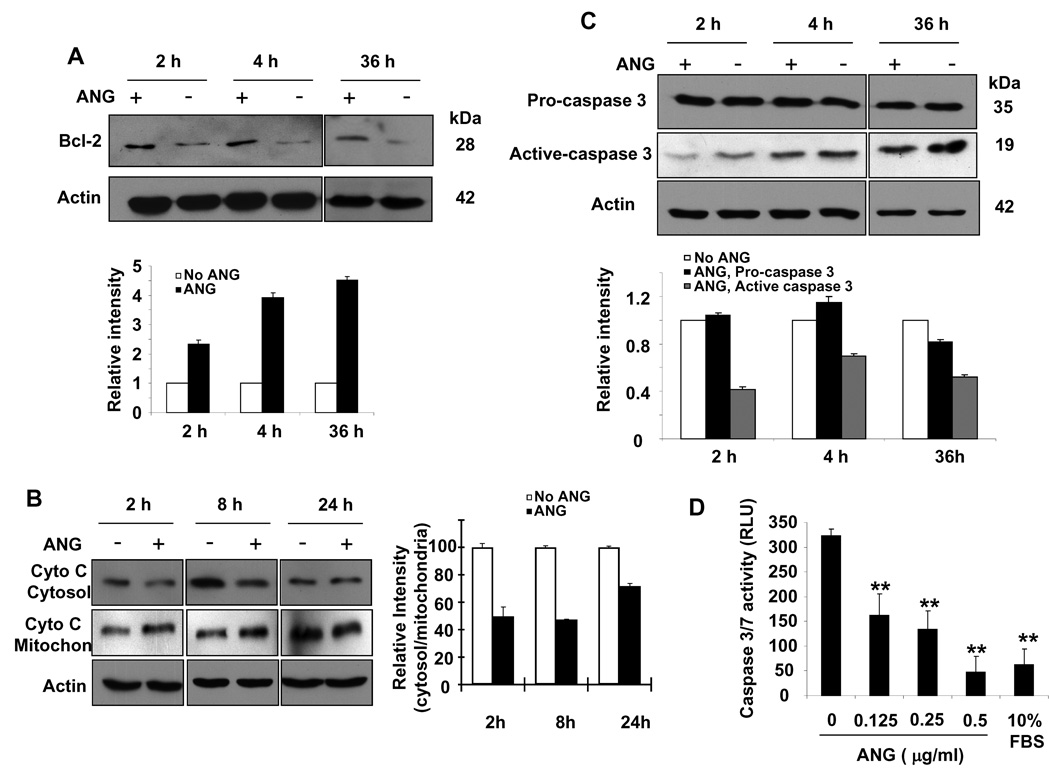

Bcl-2 was originally described in lymphoma cells, and has since been found to be widely distributed in a variety of tissues. It is an intracellular protein that localizes to mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear membranes, and has been shown to be a potent inhibitor of both programmed and accidental cell death. Our apoptotic PCR array analysis indicated that the mRNA levels of both Bcl-2 and its interacting protein Bag-1 were increased by ANG treatment. To verify whether increased expression of Bcl-2 mRNA in response to ANG stimulation was also reflected in an increased protein level, we performed western blot experiments with whole-cell extracts of P19 cells cultured in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of ANG. Figure 3A shows that the Bcl-2 protein level was increased significantly in ANG-treated cells. Densitometry analysis indicated that the total cellular Bcl-2 protein level increased by 2.3-, 3.9- and 4.5-fold after treatment with ANG for 2, 4 and 36 h, respectively (Fig. 3A, bottom panel). Thus, upregulation of Bcl-2 by ANG is an early and lasting event.

Fig. 3.

ANG enhances Bcl-2 expression, blocks cytochrome c release and inhibits caspase activity. P19 cells were cultured in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of ANG (0.5 µg·mL−1) for the indicated times. (A) Total cell lysates were used for western blotting detection of Bcl-2. The bar graph below the western panel is the relative density of Bcl-2 with β-actin as the normalization control. (B) Cytosolic and mitochondrial proteins were isolated and used for western blotting detection of cytochrome c (Cyto C). The bar graph on the right is the relative abundance of cytochrome c in the cytosol versus that in the mitochondria. (C) Western blotting analysis of pro- and active caspase 3 in the total cell lysate. The bar graph below the western panel is the relative density of Bcl-2 with β-actin as the normalization control. (D) Effect of ANG on caspase activity. Caspase activities were measured using Apo-ONE Caspase 3/7 Reagent.

One of the primary functions of Bcl-2 is to prevent the permeabilization of mitochondria, thus inhibiting the release of cytochrome c, leading to the inhibition of caspase activation. Therefore, we examined the effect of ANG on the serum withdrawal-induced release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol. Western blotting analysis was used to detect cytochrome c in the cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions isolated from cells treated with or without ANG. As shown in Fig. 3B, the amount of cytochrome c in the cytosol of cells cultured in the presence of ANG was significantly lower than that in the absence of ANG (Fig. 3B, top panel). Consistently, the mitochondrial fraction of ANG-treated cells showed a higher level of cytochrome c (Fig. 3B, middle panel). Image J analysis (Fig. 3B, right panel) showed that the ratio of cytosolic to mitochondrial cytochrome c decreased by 50 ± 6.7%, 47 ± 0.7% and 72 ± 2.1% in cells cultured in the presence of ANG for 2, 4 and 24 h, respectively, when compared with that in the absence of ANG. Thus, the prevention of cytochrome c release from mitochondria by ANG is an early and lasting event.

Next, we examined the effect of ANG on caspase activation. Figure 3C shows that ANG prevents significantly caspase 3 activation. The protein levels of pro-caspase 3 were not significantly different in the presence or absence of ANG (Fig. 3C, top panel). However, the level of active (cleaved) caspase 3 was significantly lower in ANG-treated cells at all time points examined (Fig. 3C, middle panel). Thus, there was an inverse correlation between the protein levels of Bcl-2 and active caspase 3. We also measured the combined activity of caspases 3 and 7, and found that ANG inhibited the caspase activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3D). The assay system employed (Apo-ONE Caspase 3/7 reagents from Promega) did not distinguish between caspases 3 and 7, and so the results shown in Fig. 3D reflect the total activity of the two caspases. These findings suggest that ANG exerts its upregulatory activity on Bcl-2 at the transcriptional level, and that the effect of ANG on caspase is primarily post-transcriptional.

The anti-apoptotic activity of ANG is dependent on Bcl-2

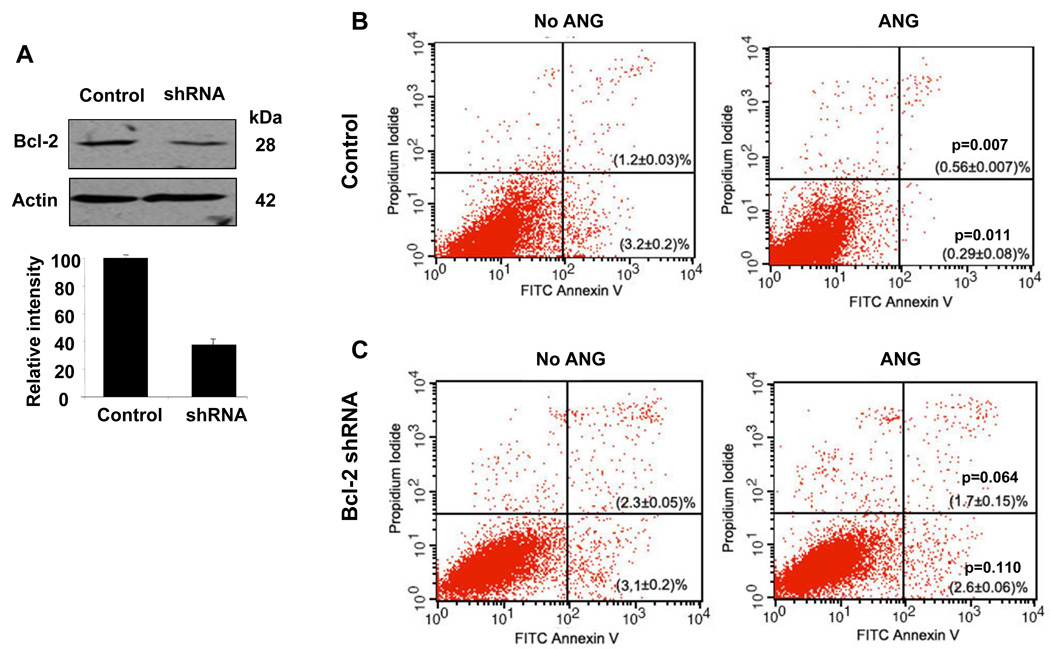

To understand whether the upregulation of Bcl-2 is an underlying mechanism by which ANG prevents apoptosis, we used siRNA to knock down Bcl-2 expression, and examined the resultant changes in the responses of cells to serum starvation in the presence and absence of ANG. The cells were transfected with a retroviral vector encoding an shRNA sequence specific to Bcl-2, and stable transfectants were selected with puromycin. A scrambled shRNA sequence was used as control. Western blotting analysis indicated that the knockdown efficiency was about 62% with this shRNA clone (Fig. 4A). Flow cytometric analysis of Annexin V- and PI-stained cells was used to identify early and late apoptotic cells. As shown in Fig. 4B, with control cells transfected with the control vector encoding a scrambled shRNA, the percentages of early and late apoptotic cells were 3.2 ± 0.2% and 1.2 ± 0.03%, respectively, in the absence of ANG, and 0.29 ± 0.08% (P = 0.011) and 0.56 ± 0.01% (P = 0.007), respectively, in the presence of ANG. Thus, there were 91% and 53% reductions in early and late apoptotic cells in the presence of ANG. When early and late apoptotic cells were combined, ANG presented a total of 81% inhibition of serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis in these cells. However, in Bcl-2 knockdown cells (Fig. 4C), the percentages of early and late apoptotic cells were 3.1 ± 0.2% and 2.3 ± 0.05%, respectively, in the absence of ANG, and 2.6 ± 0.06% (P = 0.064) and 1.7 ± 0.15% (P = 0.11), respectively, in the presence of ANG. There were only 16% and 24% reductions in early and late apoptotic cells in the presence of ANG. In Bcl-2 knockdown cells, ANG treatment resulted in only a 20% reduction in apoptotic cells. Therefore, knockdown of Bcl-2 inhibited the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG by 75%, and the P values indicate that the difference between the controls and ANG-treated samples was no longer statistically significant. These data demonstrate that the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG depends on the function of Bcl-2.

Fig. 4.

Bcl-2 siRNA inhibits the protective activity of ANG. (A) Western blotting analysis of Bcl-2 protein level in vector control and in Bcl-2-specific shRNA transfectants. The bar graph below the western panel is the relative density of Bcl-2 with β-actin as the normalization control. (B, C) Flow cytometric analyses of apoptotic cells in vector control transfectants (B) and in Bcl-2 shRNA transfectants (C). Cells were cultured in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of ANG (0.5 µg·mL−1) for 18 h, and analyzed using the FITC–Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I. Cells cultured in 10% fetal bovine serum were used to set the cut-off value of propidium iodide and Annexin–FITC staining.

ANG upregulates Nf-κb and enhances its nuclear translocation

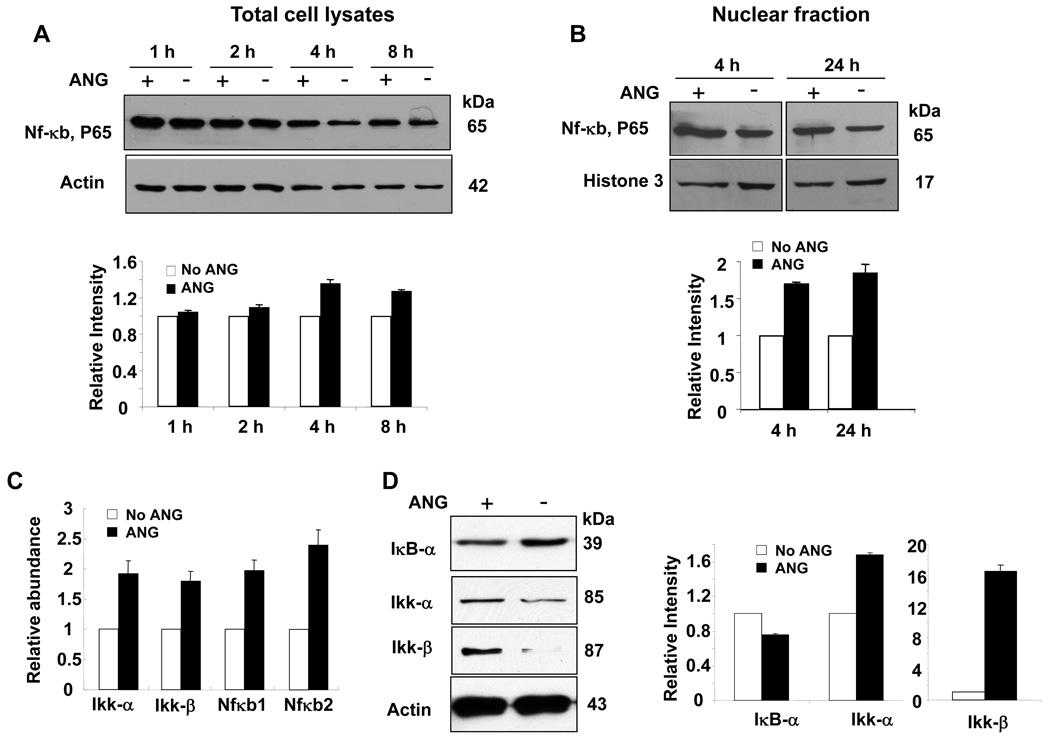

Death receptor-mediated signaling is another major apoptosis pathway that can detect the presence of extracellular death signals and trigger the intrinsic apoptosis machinery of cells. Apoptosis PCR array analysis indicated that ANG universally downregulates the expression of genes associated with the death receptor pathway. For example, the expression of Fas, Fas ligand (Fasl), Tnf, Tnfr and Tnfr-associated proteins, such as Traf-2, Tnfrsfl1b and Tnfsf10, was inhibited by ANG. At the same time, ANG upregulates Nf-κb, a universally expressed transcription factor known to play an important role in cell survival. We therefore examined the protein level of Nf-κb in ANG-treated cells by western blotting analysis. Figure 5A shows that ANG treatment increases the level of Nf-κb protein. At 4 and 8 h, the Nf-κb protein levels in ANG-treated cells were 40% and 30% higher, respectively, than in untreated cells (Fig. 5A). It is notable that the Nf-κb protein level decreases with incubation time in both control and ANG-treated cells. It is thus possible that ANG treatment also slows down Nf-κb degradation, thereby contributing to the increase in the steady-state protein level of Nf-κb. In any event, it is clear that ANG upregulates the expression of both the mRNA and protein of Nf-κb.

Fig. 5.

Effect of ANG on the Nf-κb pathway. (A) Nf-κb protein level in total cell lysate. Top panel: western blotting analysis; bottom panel: Image J analysis of band intensity with β-actin as the normalization control. (B) Nf-κb protein level in the nuclear fraction. Histone H3 was used as the loading control. (C) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of Ikk-α, Ikk-β, Nf-κb1 and Nf-κb2. β-Actin was used as the internal control for normalization of the ΔCt value. (D) Western blotting analysis of IκB-α, Ikk-α and Ikk-β. β-Actin was used as a loading control for the normalization of Image J analysis of the band intensity.

ANG also upregulates Ripk1, a key upstream regulator of the Nf-κb pathway. Ripk1 phosphorylates receptor-interacting protein (Rip), leading to the activation of Nf-κb-inducing kinase, which, in turn, activates Ikk, a kinase that phosphorylates the inhibitor of κB (IκB), leading to IκB degradation and allowing Nf-κb to move to the nucleus to activate transcription. Nf-κb exists as a heterodimer, comprising p65 (also known as RelA) and p50 subunits, which is held in an inactive form in the cytosol by interaction with IκB. Nf-κb is activated by the phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκB, which results in the translocation of the liberated Nf-κb to the nucleus, where it induces the transcription of target genes. To confirm that the Nf-κb pathway is indeed activated by ANG, we first examined the effect of ANG on the level of nuclear Nf-κb. Figure 5B shows that ANG increased the protein level of Nf-κb in the nucleus. After 4 and 24 h of culture, the nuclear Nf-κb levels in ANG-treated cells were 70% and 80% higher, respectively, than in untreated cells. Next, we performed quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of Ikk, which regulates the nuclear translocation of Nf-κb. Figure 5C shows that both Ikk-α and Ikk-β were upregulated by ANG. Moreover, the upregulation of Nf-κb1 and Nf-κb2 was confirmed by real-time PCR. Figure 5D shows that the protein levels of Ikk-α and Ikk-β were increased in ANG-treated cells, whereas that of IκB-α was decreased. These findings were consistent with the observation that nuclear Nf-κb was increased by ANG. Taken together, these results demonstrate that ANG not only upregulates Nf-κb, but also enhances its nuclear translocation.

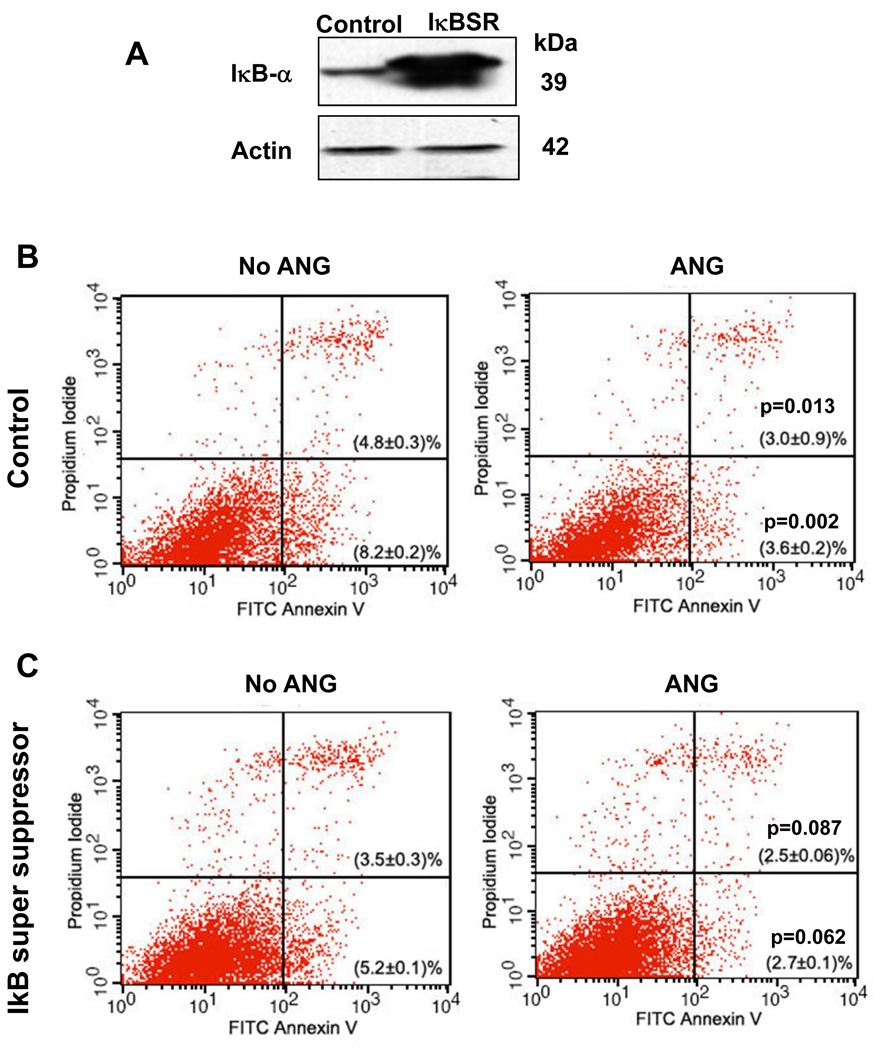

Nf-κb inhibition by IκB-α super suppressor (IκBSR) partially attenuates the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG

To determine whether the survival signals propagated by the Nf-κb pathway mediate the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG, we studied the effect of Nf-κb inhibition on cell survival in the presence and absence of ANG. A phosphorylation-defective IκBSR, or a control vector, was transfected into P19 cells, and the expression of IκBSR was confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 6A). With the vector control transfectants, the percentages of early and late apoptotic cells were 8.2 ± 0.2% and 4.8 ± 0.3%, respectively, in the absence of ANG, and 3.6 ± 0.2% (P = 0.013) and 3.0 ± 0.9% (P = 0.002), respectively, in the presence of ANG (Fig. 6B). Therefore, there were 56% and 37% reductions in early and late apoptotic cells, respectively, in the presence of ANG. However, in IκBSR transfectants (Fig. 6C), the percentages of early and late apoptotic cells were 5.2 ± 0.1% and 3.5 ± 0.3%, respectively, in the absence of ANG, and 2.7 ± 0.1% (P = 0.087) and 2.5 ± 0.06% (P = 0.062), respectively, in the presence of ANG. Treatment with ANG thus only resulted in 48% and 29% reductions in early and late apoptotic cells, respectively, when Nf-κb activity was inhibited by IκBSR. When early and late apoptotic cells were combined, ANG treatment resulted in 56% and 40% reductions in apoptotic cells. Thus, the inhibition of Nf-κb activity by IκBSR decreased the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG by 29%. These results suggest that the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG is partially dependent on Nf-κb, but the degree of dependence is not as great as with the Bcl-2 pathway.

Fig. 6.

IκBSR attenuates the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG. (A) Western blotting analysis of IκB-α protein level in the vector control and in IκBSR transfectants. (B, C) Flow cytometric analyses of apoptotic cells in vector control transfectants (B) and in IκBSR transfectants (C). Cells were cultured in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of ANG (0.5 µg·mL−1) for 18 h, and analyzed using the FITC–Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I. Cells cultured in 10% fetal bovine serum were used to set the cut-off value of propidium iodide and Annexin–FITC staining.

Discussion

The most significant finding of this study is that ANG activates both the Bcl-2-mediated anti-apoptotic pathway and the Nf-κb-mediated cell survival pathway in P19 cells. P19 cells have been used widely in neuronal research as they can both self-renew and differentiate into various types of neuronal cell on appropriate stimulation. Serum provides sustenance for cells in culture because of the presence of trophic factors. Undifferentiated P19 cells have a very low endogenous ANG level and undergo apoptosis in the absence of serum (Fig. 1). We have shown, by three different methods, that ANG prevents the serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis of P19 cells (Fig. 1). As a deficiency in trophic factors is one of the major causes of neuronal cell death, the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG is relevant to its protective role in motor neuron degeneration.

ANG has been found to affect both the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. For its role in the mitochondrial pathway, ANG upregulates the expression of both the mRNA and protein of Bcl-2, the key player in this intrinsic signal-induced apoptosis pathway. Bcl-2 overexpression has been shown to protect against cell death in non-neuronal cells induced by oxidative stress or calcium flux [30,31]. In neuronal cells, Bcl-2 overexpression eliminates serum deprivation-induced cell death of brainstem auditory neurons [32] and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid receptor-mediated apoptosis of cortical neurons [33]. Overexpression of Bcl-2 also blocks Aβ-induced apoptosis of PC12 cells and cortical neurons [34]. Moreover, ALS mice bearing the Bcl-2 transgene survive longer than control ALS mice [35]. These previous findings have indicated that Bcl-2 plays an important role in neuronal cell apoptosis and survival. Thus, our observation that ANG enhances the expression of Bcl-2 provides a plausible explanation for the beneficial effect of ANG seen in both motor neuron culture and in SOD1G93A transgenic mice. Indeed, the knockdown of Bcl-2 abolished the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG by 75% (Fig. 4). Therefore, ANG-mediated upregulation of Bcl-2 is at least one of the reasons for the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG.

It should be noted that PCR array analysis showed that three other Bcl-2-related genes were also differentially regulated by ANG. Bag1 was upregulated, whereas Bak1 and Bcl2l10 were downregulated, by ANG (Fig. 2). Bag1 has been shown to enhance the anti-apoptotic effects of Bcl-2. It acts as a link between growth factor receptors and the anti-apoptotic mechanism [36]. In contrast, Bak1 and Bcl2l10 both belong to the Bcl-2 protein family, and are known to induce apoptosis. Bak1 interacts with and accelerates the opening of the voltage-dependent anion channel of the mitochondria, and leads to the loss of membrane potential and the release of cytochrome c [37]. It also interacts with Bcl-2 and antagonizes its anti-apoptotic activity [38]. Bcl2l10 protein has been reported to interact with Apaf1 and to form a protein complex with caspase 9 [39]. Thus, ANG seems to have a profound effect on the Bcl-2-mediated anti-apoptosis pathway.

Mechanistic studies have shown that the anti-apoptotic function of Bcl-2 is brought about by its ability to maintain the integrity of mitochondrial membranes. It prevents the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, thereby preventing the formation of apoptotic bodies. As a consequence, caspase activity is inhibited. Consistent with the upregulation of Bcl-2 and Bag1, and the downregulation of Bak1 and Bcl2l10, we found that ANG blocks the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol (Fig. 3B), and inhibits the proteolytic activation of caspase 3 (Fig. 3C). Moreover, cellular caspase activity is decreased in ANG-treated cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3D). Caspases are major players in the process of apoptosis, and have been categorized into upstream initiators and downstream executioners. In addition to proteolytic cleavage and the activation of both initiating and executing caspases, their activities can also be regulated at the transcriptional level. For example, transcriptional upregulation of caspases occurs in neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS [40]. A prolonged period of neuronal caspase activation has been detected in transgenic ALS mice. As these mice aged, there was progressive upregulation of caspase 1, followed by upregulation of caspase 3. These sequential events were also detected at the level of enzymatic activity [41]. The finding of caspases 1 and 3 activation in spinal cord samples from patients with ALS indicates the clinical relevance of caspase activation to ALS [42,43]. Thus, both the degree of activation and the number of caspase molecules within the cell determine the level of caspase activity. It is therefore relevant to note that the transcription of caspases 1, 12 and 14 is downregulated by ANG (Fig. 2C). It is unclear why caspase 6 seems to be upregulated in ANG-treated cells (Fig. 2C). In any event, the inhibition of the total cellular caspase activity by ANG demonstrates that the apoptosis process is held in check by ANG.

ANG also has a significant effect on the extrinsic apoptosis pathway, which is mediated by death receptors such as Fas and Tnfr. ANG was found to downregulate the expression of Fas, Lasl, Tnf and Tnfr. Thus, both the ligands and receptors of the Fas–Fasl and Tnf–Tnfr signaling axes were downregulated by ANG. Moreover, we found that Tnfsf10 (TRAIL) and its decoy receptor Tnfrsf11b (osteoprotegerin) were also downregulated by ANG (Fig. 2). It can be envisaged that the signals propagated by the death receptor pathway are attenuated significantly by ANG by a widespread up- and downregulation of the major players of this pathway.

Signaling mediated by Fas and Tnfr can be either anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic, as the Tnfr-associated death domain of the activated receptor is able to recruit several signaling molecules, including Rip, Tnfr-associated factor (Traf) and Fas-associated protein with death domain (Fadd). Rip is activated by Ripk1 and stimulates a pathway leading to the activation of Nf-κb, whereas Fadd mediates the activation of apoptosis by recruiting and oligmerizing caspase 8. We found that Ripk1, the upstream kinase that phosphorylates Rip, is upregulated by ANG (Fig. 2). Rip is an upstream kinase that phosphorylates Ikk. Activated Ikk phosphorylates IκB, leading to its degradation and thereby releasing Nf-κb for nuclear translocation [44]. It is interesting to note that, in addition to post-translational activation by upregulated Ripk1, the mRNA levels of Ikk-α, Ikk-β, Nf-κb1 and Nf-κb2 were also all upregulated by ANG. Therefore, ANG has a significant effect on the activation of the Nf-κb survival pathway by upregulating the key players at both the transcriptional and post-translational levels. Consistently, the inhibition of Nf-κb activity by IκBSR attenuated significantly the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG (Fig. 6).

ANG has also been found to downregulate the expression of Trp53inp1 and Trp63. Trp53inp1 is known to induce cell cycle arrest at G1 and enhances p53-mediated apoptosis. It also interacts with p53 and regulates its transcriptional activity [45]. Trp63 is a p53-related gene known to regulate apoptosis through the caspase 8 pathway [46]. It is therefore possible that the anti-apoptotic activity of ANG may also be mediated through the p53 pathway. Downregulation of Trp53inp1 and Trp63 by ANG was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR, but further experiments are required to characterize their involvement in the anti-apoptotic function of ANG.

In summary, our results demonstrate that ANG prevents apoptosis and enhances cell survival by upregulating and activating the Bcl-2 and NF-κb pathways. For the anti-apoptotic effect, ANG upregulates Bcl-2, thereby leading to the inhibition of caspase activity. ANG also has a significant effect on the cell death and survival signals mediated by the death receptor pathway. It downregulates both the ligands and receptors of this pathway and, in so doing, may reduce the apoptotic signals propagated through the death receptors. At the same time, it upregulates the key players of the Nf-κb pathway and thus enhances cell survival.

Experimental procedures

ANG and cell culture

ANG was prepared as a recombinant protein and was purified to homogeneity by reversed-phase HPLC [47]. The ribonucleolytic and angiogenic activities of each preparation were examined by tRNA assay and endothelial cell tube formation assay, respectively [48]. P19 cells were maintained in DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum in the presence of penicillin (100 units·mL−1) and streptomycin (100 µg·mL−1). Cells were subcultured in a 1 : 10 ratio every 48 h to maintain exponential growth and to avoid aggregation and differentiation. For serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis, cells were seeded and cultured in DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum for 24 h, washed with DMEM three times, and cultured in serum-free DMEM in the presence or absence of ANG for 18 h, unless otherwise indicated.

DNA fragmentation analysis

Serum withdrawal-induced DNA fragmentation was analyzed using the Apoptotic DNA Ladder Kit (Roche). DNA from 2 × 106 cells was extracted, and 3 µg of each sample were subjected to agarose (1%) gel electrophoresis. The positive control for DNA fragmentation was prepared following the manufacturer’s protocol. The gel was stained by EB to visualize DNA.

EB/AO staining of apoptotic cells

The method described by Ribble et al. [49] was followed. Briefly, cells were detached by trypsinization, pelleted and washed with 4 °C NaCl/Pi. The cells were resuspended in 25 µL of 4 °C NaCl/Pi and mixed with 2 µL of the EB–AO dye mixture (100 µg·mL−1 each of AO and EB in NaCl/Pi) at room temperature for 5 min. Stained cells were placed on a clean microscope slide and covered with coverslips. Microscopic images were taken with a Nikon digital camera. A total of 750 cells were counted from each group.

Flow cytometry

The FITC–Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Pharmingen) was used following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were washed twice with cold NaCl/Pi and resuspended in 1 × Binding Buffer at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells·mL−1. An aliquot of 100 µL was mixed with 5 µL of FITC–Annexin V and 5 µL of PI, and incubated at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. At the end of incubation, the sample was diluted by the addition of 400 µL of 1 × Binding Buffer, and analyzed for FITC- and PI-stained cells using a BD LSR benchtop flow cytometer. The experiments were repeated at least three times and the P values of the flow cytometry data between control and ANG-treated samples were calculated using Student’s t-test.

Cytochrome c release

The cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were separated as described by Pagliari et al. [50]. Briefly, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 80 mm KCl, 250 mm sucrose, 50 µg·mL−1 digitonin, 1 mm dithiothreitol and proteinase inhibitor cocktail), placed on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 10 000 g for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and designated as the cytosolic fraction. The pellet was resuspended in washing buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 7.2, 250 mm KCl), centrifuged again and the supernatant was added to the cytosolic fraction. To extract mitochondrial proteins, the pellet was again resuspended in lysis buffer, subjected to three freeze–thaw cycles and centrifuged at 20 000 g for 10 min. The supernatant contains mitochondrial proteins. Cytochrome c in the cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions was detected by Western blot analysis with an anti-cytochrome c antibody from eBioscience (5 µg·mL−1).

Caspase 3/7 activity

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates. At the end of treatment, Apo-ONE Caspase 3/7 Reagent (Promega), at an equal volume to the culture medium, was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Fluorescence was measured on a Wallac Victor 3 1420 Multilabel Counter (Perkin-Elmer) at an emission wavelength of 521 nm and an excitation wavelength of 485 nm. The wells without cells were used as blanks.

Apoptosis PCR array analysis

Total cellular RNA was extracted by Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), and the RNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). One microgram of each sample was analyzed using the Apoptosis PCR Array Kit (SABioscience) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The array was read on a Roche LightCycler 480 real-time PCR machine. The raw array data were processed and analyzed by the SABioscience online PCR Array Data Analysis System (http://www.sabiosciences.com/pcr/arrayanalysis.php) with a threshold set at 2.0.

Quantitative real time RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted by Trizol and reverse transcribed to cDNA according to standard methods. Real-time PCR was carried out using a Roche LightCycler 480 in a total volume of 20 µL comprising 2 µL of 1 : 10 diluted first-strand cDNA, 2 µL each of the forward and reverse primers (5 µm), 10 µL of LightCycler 480 Green I Master (Roche) and 4 µL of nuclease-free water. The sequences of the primers were as follows. Nf-κb1: forward, 5′-GTATGCACCGTAACAGCA-3′; reverse, 5′-CCTAATACACGCCTCTGTCA-3′; Nf-κb2: forward, 5′-TTGCCCACCTTCTCCC-3′; reverse, 5′-GGGTTGTAGGCCAAGGA-3′; Ikk-α: forward, 5′-CGTGTTCTCAAGGAGCTGT-3′; reverse, 5′-CCCTGCATAAACATGACAGT-3′; Ikk-β: forward, 5′-CCTGACAAGCCTGCTACT-3′; reverse, 5′-CAAGATCCATGTCCAACGTG-3′; actin: forward, 5′-ATCACTATTGGCAACGAGC-3′; reverse, 5′-GGTCTTTACGGATGTCAACG-3′. The PCR mixture was heat denatured at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 55 °C and 30 s at 72 °C. Fluorescent signals were acquired at the last step of each cycle. A melting curve was calculated at the end of the cycles. β-Actin was used as the housekeeping gene for internal control for the starting RNA concentration and quality. The raw data were analyzed by LightCycler 480 analysis software, and the fold changes (2−ΔΔCt) in the mRNA level were determined from the difference in the crossing point (ΔΔCt), which was calculated using the following formula, ΔΔCt = (CtGOI – CtHPG)exp – (CtGOI – CtHPG)con, where GOI and HPG represent the gene of interest and housekeeping gene, respectively, and ‘exp’ and ‘con’ represent experimental and control samples, respectively.

Western blotting

Nuclear proteins and total cell lysates were prepared using the Nuclear Extract Kit from Active Motif. Protein concentrations were determined by a Reducing Agent-Compatible BCA Assays Kit from Pierce. Proteins (20 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked by 5% fat-free milk in TBS, and incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Incubation with the second antibody was carried out at room temperature for 1 h. The antibodies against total and cleaved caspase 3, caspase 8, cleaved PARP-1, Ikk-α, Ikk-β, Nf-κb (p65) and IκB-α were from Cell Signaling. A dilution of 1 : 1000 was used for the above antibodies. Anti-β-actin antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz and Thermo Fisher Scientific, and used at dilutions of 1 : 600 and 1 : 200, respectively. Anti-Histone H3 antibody was from Biolegend and was used at a dilution of 1 : 500. Band intensities were determined using Image J software.

Transfection of Bcl-2 siRNA and IκBSR

A mouse Bcl-2-specific shRNA clone and an empty vector control (pSM) were obtained from Open Biosystems. P19 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000. Stable transfectants were selected with 2 µg·mL−1 puromycin. IκBSR clone and an empty vector control (Ubc) were from Addgene. Transfected cells were cultured in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of 0.5 µg·mL−1 ANG for 18 h. Apoptotic cells were detected by flow cytometric analysis using an FITC–Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Pharmingen).

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA105241 and NS065237

Abbreviations

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ANG

angiogenin

- AO

acridine orange

- EB

ethidium bromide

- Fadd

Fas-associated protein with death domain

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- IκB

inhibitor of κB

- IκBSR

IκB-α super suppressor

- Nf-κb

nuclear factor-κb

- PI

propidium iodide

- Rip

receptor-interacting protein

- Tnfr

tumor necrosis factor receptor

- Traf

Tnfr-associated factor

References

- 1.Fett JW, Strydom DJ, Lobb RR, Alderman EM, Bethune JL, Riordan JF, Vallee BL. Isolation and characterization of angiogenin, an angiogenic protein from human carcinoma cells. Biochemistry. 1985;24:5480–5486. doi: 10.1021/bi00341a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tello-Montoliu A, Patel JV, Lip GY. Angiogenin: a review of the pathophysiology and potential clinical applications. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1864–1874. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshioka N, Wang L, Kishimoto K, Tsuji T, Hu GF. A therapeutic target for prostate cancer based on angiogenin-stimulated angiogenesis and cancer cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14519–14524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606708103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner HL, Weiner LH, Swain JL. Tissue distribution and developmental expression of the messenger RNA encoding angiogenin. Science. 1987;237:280–282. doi: 10.1126/science.2440105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu S, Yu D, Xu ZP, Riordan JF, Hu GF. Angiogenin activates Erk1/2 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:305–310. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Z, Monti DM, Hu G. Angiogenin activates human umbilical artery smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:909–914. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HM, Kang DK, Kim HY, Kang SS, Chang SI. Angiogenin-induced protein kinase B/Akt activation is necessary for angiogenesis but is independent of nuclear translocation of angiogenin in HUVE cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:509–513. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kishimoto K, Liu S, Tsuji T, Olson KA, Hu GF. Endogenous angiogenin in endothelial cells is a general requirement for cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2005;24:445–456. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuji TYS, Kishimoto K, Olson KA, Liu S, Hirukawa S, Hu G-f. Angiogenin is translocated to the nucleus of HeLa cells and is involved in rRNA transcription and cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1352–1360. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu ZP, Tsuji T, Riordan JF, Hu GF. Identification and characterization of an angiogenin-binding DNA sequence that stimulates luciferase reporter gene expression. Biochemistry. 2003;42:121–128. doi: 10.1021/bi020465x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conforti FL, Sprovieri T, Mazzei R, Ungaro C, La Bella V, Tessitore A, Patitucci A, Magariello A, Gabriele AL, Tedeschi G, et al. A novel angiogenin gene mutation in a sporadic patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis from southern Italy. Neuromusc Disord. 2008;18:68–70. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrado L, Battistini S, Penco S, Bergamaschi L, Testa L, Ricci C, Giannini F, Greco G, Patrosso MC, Pileggi S, et al. Variations in the coding and regulatory sequences of the angiogenin (ANG) gene are not associated to ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) in the Italian population. J Neurol Sci. 2007;258:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gellera C, Colombrita C, Ticozzi N, Castellotti B, Bragato C, Ratti A, Taroni F, Silani V. Identification of new ANG gene mutations in a large cohort of Italian patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurogenetics. 2008;9:33–40. doi: 10.1007/s10048-007-0111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenway MJ, Andersen PM, Russ C, Ennis S, Cashman S, Donaghy C, Patterson V, Swingler R, Kieran D, Prehn J, et al. ANG mutations segregate with familial and ‘sporadic’ amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:411–413. doi: 10.1038/ng1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paubel A, Violette J, Amy M, Praline J, Meininger V, Camu W, Corcia P, Andres CR, Vourc’h P. Mutations of the ANG gene in French patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1333–1336. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.10.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Es MA, Diekstra FP, Veldink JH, Baas F, Bourque PR, Schelhaas HJ, Strengman E, Hennekam EA, Lindhout D, Ophoff RA, et al. A case of ALS-FTD in a large FALS pedigree with a K17I ANG mutation. Neurology. 2009;72:287–288. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339487.84908.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu D, Yu W, Kishikawa H, Folkerth RD, Iafrate AJ, Shen Y, Xin W, Sims K, Hu GF. Angiogenin loss-of-function mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/ana.21221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez-Santiago R, Hoenig S, Lichtner P, Sperfeld AD, Sharma M, Berg D, Weichenrieder O, Illig T, Eger K, Meyer T, et al. Identification of novel angiogenin (ANG) gene missense variants in German patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol. 2009;256:1337–1342. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5124-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crabtree B, Thiyagarajan N, Prior SH, Wilson P, Iyer S, Ferns T, Shapiro R, Brew K, Subramanian V, Acharya KR. Characterization of human angiogenin variants implicated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11810–11818. doi: 10.1021/bi701333h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramanian V, Crabtree B, Acharya KR. Human angiogenin is a neuroprotective factor and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated angiogenin variants affect neurite extension/pathfinding and survival of motor neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:130–149. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subramanian V, Feng Y. A new role for angiogenin in neurite growth and pathfinding: implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1445–1453. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kieran D, Sebastia J, Greenway MJ, King MA, Connaughton D, Concannon CG, Fenner B, Hardiman O, Prehn JH. Control of motoneuron survival by angiogenin. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14056–14061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3399-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sebastia J, Kieran D, Breen B, King MA, Netteland DF, Joyce D, Fitzpatrick SF, Taylor CT, Prehn JH. Angiogenin protects motoneurons against hypoxic injury. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1238–1247. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bain G, Ray WJ, Yao M, Gottlieb DI. From embryonal carcinoma cells to neurons: the P19 pathway. Bioessays. 1994;16:343–348. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McBurney MW, Rogers BJ. Isolation of male embryonal carcinoma cells and their chromosome replication patterns. Dev Biol. 1982;89:503–508. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bain G, Gottlieb DI. Neural cells derived by in vitro differentiation of P19 and embryonic stem cells. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1998;5:175–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norris DA, Middleton MH, Whang K, Schleicher M, McGovern T, Bennion SD, David-Bajar K, Davis D, Duke RC. Human keratinocytes maintain reversible anti-apoptotic defenses in vivo and in vitro. Apoptosis. 1997;2:136–148. doi: 10.1023/a:1026456229688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong WW, Gentle IE, Nachbur U, Anderton H, Vaux DL, Silke J. RIPK1 is not essential for TNFR1-induced activation of NF-kappaB. Cell Death Differ. 2009 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Du F, Wang X. TNF-alpha induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell. 2008;133:693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hockenbery DM, Oltvai ZN, Yin XM, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell. 1993;75:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lam M, Dubyak G, Chen L, Nunez G, Miesfeld RL, Distelhorst CW. Evidence that BCL-2 represses apoptosis by regulating endoplasmic reticulum-associated Ca2+ fluxes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6569–6573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mostafapour SP, Del Puerto NM, Rubel EW. bcl-2 overexpression eliminates deprivation-induced cell death of brainstem auditory neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4670–4674. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04670.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheung NS, Beart PM, Pascoe CJ, John CA, Bernard O. Human Bcl-2 protects against AMPA receptor-mediated apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2000;74:1613–1620. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saille C, Marin P, Martinou JC, Nicole A, London J, Ceballos-Picot I. Transgenic murine cortical neurons expressing human Bcl-2 exhibit increased resistance to amyloid beta-peptide neurotoxicity. Neuroscience. 1999;92:1455–1463. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kostic V, Jackson-Lewis V, de Bilbao F, Dubois-Dauphin M, Przedborski S. Bcl-2: prolonging life in a transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 1997;277:559–562. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin J, Hutchinson L, Gaston SM, Raab G, Freeman MR. BAG-1 is a novel cytoplasmic binding partner of the membrane form of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor: a unique role for proHB-EGF in cell survival regulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30127–30132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chittenden T, Harrington EA, O’Connor R, Flemington C, Lutz RJ, Evan GI, Guild BC. Induction of apoptosis by the Bcl-2 homologue Bak. Nature. 1995;374:733–736. doi: 10.1038/374733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin B, Kolluri SK, Lin F, Liu W, Han YH, Cao X, Dawson MI, Reed JC, Zhang XK. Conversion of Bcl-2 from protector to killer by interaction with nuclear orphan receptor Nur77/TR3. Cell. 2004;116:527–540. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inohara N, Gourley TS, Carrio R, Muniz M, Merino J, Garcia I, Koseki T, Hu Y, Chen S, Nunez G. Diva, a Bcl-2 homologue that binds directly to Apaf-1 and induces BH3-independent cell death. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32479–32486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedlander RM. Apoptosis and caspases in neurodegenerative diseases. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1365–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pasinelli P, Houseweart MK, Brown RH, Jr, Cleveland DW. Caspase-1 and -3 are sequentially activated in motor neuron death in Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase-mediated familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13901–13906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240305897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li M, Ona VO, Guegan C, Chen M, Jackson-Lewis V, Andrews LJ, Olszewski AJ, Stieg PE, Lee JP, Przedborski S, et al. Functional role of caspase-1 and caspase-3 in an ALS transgenic mouse model. Science. 2000;288:335–339. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin LJ. Neuronal death in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is apoptosis: possible contribution of a programmed cell death mechanism. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:459–471. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199905000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobs MD, Harrison SC. Structure of an IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex. Cell. 1998;95:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomasini R, Seux M, Nowak J, Bontemps C, Carrier A, Dagorn JC, Pebusque MJ, Iovanna JL, Dusetti NJ. TP53INP1 is a novel p73 target gene that induces cell cycle arrest and cell death by modulating p73 transcriptional activity. Oncogene. 2005;24:8093–8104. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borrelli S, Candi E, Alotto D, Castagnoli C, Melino G, Vigano MA, Mantovani R. p63 regulates the caspase-8-FLIP apoptotic pathway in epidermis. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:253–263. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shapiro R, Harper JW, Fox EA, Jansen HW, Hein F, Uhlmann E. Expression of Met-(−1) angiogenin in Escherichia coli: conversion to the authentic less than Glu-1 protein. Anal Biochem. 1988;175:450–461. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90569-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riordan JF, Shapiro R. Isolation and enzymatic activity of angiogenin. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;160:375–385. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-233-3:375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ribble D, Goldstein NB, Norris DA, Shellman YG. A simple technique for quantifying apoptosis in 96-well plates. BMC Biotechnol. 2005;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pagliari LJ, Kuwana T, Bonzon C, Newmeyer DD, Tu S, Beere HM, Green DR. The multidomain proapoptotic molecules Bax and Bak are directly activated by heat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17975–17980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506712102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]