Abstract

Abundant research finds that in young adults explicit learning (EL) is more dependent on the medial temporal lobes (MTL) whereas implicit learning (IL) is more dependent on the striatum. Using fMRI, we investigated age differences in each task and whether this differentiation is preserved in older adults. Results indicated that, while young recruited the MTL for EL and striatum for IL, both activations were significantly reduced in older adults. Additionally, results indicated that older adults recruited the MTL for IL, and this activation was significantly greater in older compared to young adults. A significant Task × Age interaction was found in both regions– with young preferentially recruiting the MTL for EL and striatum for IL, and older adults showing no preferential recruit for either task. Finally, young adults demonstrated significant negative correlations between activity in the striatum and MTL during both the EL and IL tasks. These correlations were attenuated in older adults. Taken together results support dedifferentiation in aging across memory systems.

Keywords: dedifferentiation, aging, fMRI, implicit, explicit, learning, MTL, striatum, declarative, non-declarative, memory

One of the most fundamental distinctions in memory research is the one between declarative and nondeclarative memory. Declarative memory refers to conscious memory for facts and events, whereas nondeclarative refers to memory that is expressed through performance in the absence of conscious awareness (Squire et al., 1990). Focusing on the acquisition of such memories, learning that leads to declarative memories is known as explicit learning (EL), whereas learning that leads to nondeclarative memories is known as implicit learning (IL). There is abundant animal, patient, and neuroimaging evidence that EL and IL depend on different neural substrates. Specifically, EL is more dependent on the medial temporal lobe (MTL) regions (e.g., Cohen et al., 1985; Cohen et al., 1999; Eichenbaum, 1999, 2001), whereas IL is more dependent on striatal-frontal circuitry (e.g., Heindel et al., 1989; Knowlton, 2002; Knowlton et al., 1996). The neural systems supporting EL and IL are not only different but they may also function in a competitive manner with one another (Poldrack et al., 2001; Poldrack and Packard, 2003; Sherry and Schacter, 1987). For example, animal studies have shown that lesions to one system can facilitate learning in the other system (McDonald and White, 1993; Mitchell and Hall, 1988; Packard et al., 1989), and neuroimaging evidence in young adults has found negative correlations in activations between the two systems (Jenkins et al., 1994; Poldrack et al., 2001; Poldrack and Gabrieli, 2001). The foregoing evidence suggests that these two regions interact in such a manner that links both in terms of resource allocation and neural recruitment – with each competing with the other to mediate task performance. However, no study has investigated dissociations between the contributions of striatal and MTL regions to IL and EL in older adults. What’s more, research has just begun to explore age differences within EL and IL tasks. Investigating both age differences within IL and EL tasks, as well as age × task interactions associated with the differentiation of these learning systems were the goals of the present functional MRI (fMRI) study.

It is well known that aging is associated with structural and functional decline in specific brain regions, such as the frontal lobes, striatum and MTL (for a review see Dennis and Cabeza, 2008; Raz, 2005). In addition to these region-specific effects, aging has been also associated with changes in the relative contribution of various brain regions to task performance. For example, older adults recruit contralateral brain regions to perform tasks mediated mainly by one hemisphere in young adults (Cabeza, 2002) and they recruit frontal regions for tasks that are more dependent on posterior brain regions in young adults (Davis et al., 2008; Dennis and Cabeza, 2008). This reduction in the neural specialization is also observed in ventral temporal cortex, where older adults show attenuation in the selectivity of cortical areas dedicated to the processing of faces, places, and other object categories (Park et al., 2004). These effects have been demonstrated across informational domains as well, such as right-hemisphere frontal regions associated with spatial processing and spatial working memory in young being recruited for verbal working memory in older adults (Reuter-Lorenz et al., 2000). Taken together results support the conclusion that aging is associated with a process of dedifferentiation across hemispheres, within hemispheres, and across brain regions. While these dedifferentiation effects have been demonstrated across informational domains (Reuter-Lorenz et al., 2000) and across object categories (Park et al., 2004), no evidence is available regarding whether age-related dedifferentiation also affects the distinction between declarative and nondeclarative memory systems. If older adults activate face-specific regions for processing chairs, and vice versa (Park et al., 2004), could they also activate EL regions for IL and vice versa? Given evidence of age-related dedifferentiation in visual cortices and age-related reductions in hemispheric lateralization, it stands to reason that the dichotomy of learning systems would also decrease in aging.

Supporting this pattern of dedifferentiation in learning systems includes evidence that the inherent competition between the two systems can be altered when brain structure or function is at all altered. For example, animal studies indicate that a lesion to one system can facilitate learning in the other system (McDonald and White, 1993; Mitchell and Hall, 1988; Packard et al., 1989). Additionally, data from Parkinson’s patients suggests that disruption in striatal functioning results in an attenuation of the intrinsic competition between learning systems and increased learning-related activation in MTL (Moody et al., 2004). Results suggest that, with reduced competition, the opposing system is able to assume a greater role in learning, perhaps in an effort to maintain task goals. We believe that such compensatory processes occurs in the opposing system based on the system’s ability to learn similar information, albeit under different situational structures (e.g., implicit or explicit task instructions). That is, we posit that dedifferentiation is most likely to occur between regions that are specialized to carry out similar processes. In the case of dedifferentiation in ventral visual stream, previous research has suggested that areas specialized for face processing and object processing exhibit increased activation for the opposite stimuli later in life (Park et al., 2004). Thus to the extent that IL and EL represent opposing learning systems in young adults, they may exhibit age-related increases in activation for the opposite learning task. Thus, it stands to reason that dedifferentiation between systems is also possible. As noted aging is associated with both structural and functional decline in each learning system, making it a viable model for dedifferentiation of the two regions. Moreover, given the observed compensatory mechanisms of older adults, research further suggests that dedifferentiation of these learning systems maybe lend themselves to compensatory recruitment of the alternative system. Thereby, we would not only predicted reduced learning-specific recruitment of each system in aging, but learning-dependent recruitment of the opposing system.

To investigate these questions we used fMRI to image both young and older individuals while performing two different learning tasks – one explicit and one implicit. For EL we used a common encoding task, semantic categorization, and measured EL-specific brain activity using the subsequent memory paradigm (Paller and Wagner, 2002). The subsequent memory paradigm identifies brain regions showing greater study-phase activity for items that are remembered than for those that are forgotten in a subsequent memory test. In the current study participants encoded a list of words by performing a semantic categorization task while in the scanner and, post-scan, they completed a recognition test with confidence ratings. Thus, in accord with previous subsequent memory studies (e.g., Brewer et al., 1998; Dennis et al., 2008; Kirchhoff et al., 2000) EL was defined as the difference in neural activity for subsequently remembered compared to subsequently forgotten words. Previous studies assessing age differences in subsequent memory activity have found age-related reduction in MTL activity (Dennis et al., 2008; Gutchess et al., 2005; Morcom et al., 2003).

For IL we employed the serial response time (SRT) task (Nissen and Bullemer, 1987). A commonly used IL task, the SRT task measures an individual’s ability to learn a subtle sequential regularity through repeated exposure and interaction with the sequence. In the typical SRT task participants are presented with four open circles on a computer screen. They are asked to respond as quickly and accurately as possible (via keypresses) to a circle as it fills in dark (i.e., the target) on the screen. Unbeknownst to the individual there is a repeating pattern to the targets. Learning is measured through faster and more accurate responding to the repeating pattern or sequence, than a completely random pattern of targets. IL was thus defined as a difference in neural activity to sequence compared to random trials. Again, this task is considered implicit as individuals rarely gain conscious or explicit awareness of the sequential regularity. Moreover previous behavioral studies show little or no age-related differences in SRT learning (e.g., Dennis et al., 2006; Howard and Howard, 1992).

While only a limited number of studies have examined the neural correlates underlying age differences in EL, even fewer have investigated age differences in the neural correlates of IL (for a review see Dennis and Cabeza, 2008). Moreover, the only study to date to examine the neural correlates of IL in aging using an SRT task used a blocked design, which measures sustained neural activity (Daselaar, Rombouts et al., 2003). Recent work has demonstrated that age differences are not only dependent on the task performed, but on how the neural activity is measured (i.e., with a blocked design measuring sustained activity or an event-related design measuring transient activity) (Dennis, Daselaar et al., 2007). Therefore, while Daselaar and colleagues (2003) concluded that there are no age differences in striatal activity in SRT learning, it is unclear whether similar results would be obtained when testing with event-related designs. Therefore, in addition to our main question regarding dedifferentiation in aging, the current paper will also focus on investigating task specific age differences in transient activations in both the foregoing EL and IL tasks.

Thus, the current study had 3 main goals. The first goal was to investigate age differences within both the EL and IL tasks. Based upon previous evidence of age-related reduction in EL, but not IL we predicted reduced EL activity in the MTL, but expected similar IL activity in the striatum, if transient differences followed those found in sustained measurements. The second goal was to investigate age differences in differentiation of learning systems. Given abundant dissociation evidence (Squire et al., 1990), we expected that young adults would exhibit the typical pattern of striatal activity during IL and MTL activity during EL. Based on our hypothesis that age-related dedifferentiation affects memory systems, we predicted that the differentiation between EL and IL would be reduced in older adults, who would exhibit more MTL activation during IL as well as more striatal activation during EL, compared to young adults. Thus, we predicted a significant Age × Task interactions in both the MTL and striatum. Finally, we sought to investigate age differences in the competitive processes undertaken by each learning system. As dedifferentiation is indicative of a reduction in competition of the MTL and striatum during EL and IL respectively, we also predicted a reduction in negative correlations between these two regions in older adults.

Material and Methods

Participants

Twelve healthy younger adults (8 males), with an average age of 22.2 years (SD = 3.5; range: 18-30) and 12 healthy older adults (7 males), with an average age of 67.4 years (SD = 6.7; range: 60-79) were scanned and paid for their participation. Please see Table 1 for older participant characteristics. Younger adults were all students at Duke University and older adults were recruited from the Durham, NC community. Participants with a history of neurological difficulties or psychiatric illness, loss of consciousness, alcoholism, drug abuse, and learning disabilities were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for a protocol approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Older Participant Characteristics

| Older Group Scores | Age-Matched Norm | Young Norm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean & SD | range | |||

| BMVT-R (TR) | 26.67 (6.37) | 14-35 | 21.44* | 28.74 |

| HVLT-R (TR) | 30.50 (25.54) | 24-33 | 26.65** | 29.14 |

| MMSE | 29.83 (0.39) | 29-30 | 29** | 30 |

| Education (years) | 18.25 (.75) | 17-19 | N/A | N/A |

notes: BMVT-R = Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised; HVLT-R = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised; MMSE = Mini Mental State Exam; TR = Total Recall; As noted, current study performed significantly better than age-matched norms on all cognitive measures. Older adults in the current study performed significantly better than age-matched norms on all cognitive measures. Furthermore, the older group does not significantly differ from young norms (based upon the age of our young group).

meand and standard deviation;

p=.016;

p<.001

Stimuli

IL

The stimuli consisted of four open circles, displayed horizontally in the middle of the computer screen. An event occurred when one of the four open circles filled in black. Each run started with 4 practice trials and directly followed by task trials. Each run consisted 4 cycles of 3 repetitions of the 12-item sequence (i.e 3-1-3-2-1-4-2-3-4-1-2-4), followed by 12 pseudo-random trials (with the constraint that no two trials repeated). This resulted in a total of 144 sequence trials and 48 random trials presented in each of the 3 runs. This second order predictive sequence has been used in previous behavioral and neuroimaging SRT tasks and found to be both (a) relatively impervious to explicit awareness and (b) exhibit equivalent learning by both young and older adults (e.g., Daselaar, Rombouts et al., 2003; Dennis et al., 2006).

EL

The stimuli consisted of 304 words equally divided into four categories, animal, place, object, and job. All words could be categorized into one, and only one, of the four categories. Two hundred twenty four words were used for the encoding task, inside the scanner, and an additional 80 words were presented at retrieval only, outside of the scanner.

Procedure

Participants completed 5 fMRI runs, alternating between 3 IL and 2 EL runs (run order: IL-EL-IL-EL-IL). Each run began with a 15-sec fixation period in order to allow image stabilization, lasted 4.8 minutes and included another 15-sec fixation period in the middle of the scan as a rest period.

IL

During the IL runs participants performed the Serial Response Time (SRT) Task. On each trial one of the circles darkened (the target) until a correct response occurred. Response time was measured from target onset to the first response. Unlike many former SRT tasks which used block fMRI designs, the current task was event-related. As such, each stimulus was presented for a maximum of 1500 ms and followed by an inter-trial fixation period, which varied randomly between 500 and 1250 msec. Participants were not told of the sequence regularity, but rather to simply respond as quickly and accurately as possible to the presence of a target. Response time and accuracy were recorded.

Following the scanning session (and the EL recognition test –see below) participants were given 3 tests of explicit awareness: a questionnaire, a production task, and a recognition test. [These tests of explicit awareness have been used in several prior IL studies (e.g., Dennis et al., 2006; Destrebecqz and Cleeremans, 2001; Howard et al., 2004)]. The questionnaire consisting of 5 open-ended questioned designed to probe their declarative knowledge of the sequence. Participants were asked a series of increasingly specific questions, [1) Do you notice anything special about ay in which the circles were presented? 2) Did you notice whether the circles followed a repeating pattern? If so, when? 3) Did you try to take advantage of this repeating regularity to anticipate what event was coming next? 4) Was you strategy helpful? 5) There was in fact a repeating sequence to the order in which the circles were filled in; can you guess at what it might have been? or the length of the sequence? (The experimenter encouraged people to describe any regularities at all that they noticed, even if they were vague or unsure]. All answers were recorded by the experimenter.

Only four young and seven older adults answered that they thought there might be a regularity in the presentation of the stimuli. Though no one who attempted to take advantage of this abstract feeling felt that it consistently helped task performance. Furthermore, despite this general feeling that a regularity may have been present, no participant in either age group guessed the correct length or composition of the sequence. When specifically asked to guess what the sequence was, only 3 older and 3 younger adults guessed more than 3 correct positions in a row, and none correctly repeated more than 4 correct positions. Thus, it was concluded that no participants had full declarative knowledge of the sequence structure, as assessed by the questionnaire.

On the production task participants were asked to complete two production blocks in which they needed to produce sequences by pressing the keys corresponding to the circle locations on the computer screen. On the first block participants were told to try to “generate a series of words/trials that resemble the learning sequence as much as possible.” In the second block they were told to try to “create a sequence that is different from the one you responded to.” Furthermore, participants were instructed not to be ‘systematic’ in their responses for this latter exclusion block. A difference in the production of sequence structure under the two instructional conditions has been taken as evidence of participants having control over sequence knowledge and hence as a test of declarative knowledge (Destrebecqz and Cleeremans, 2001).

The Production data were analyzed by assessing the frequency with which each participant produced pattern-consistent and pattern-inconsistent triplets under inclusion and exclusion instructions. [Because all single items and pairs occurred with equal probability in the current sequence structure, the lowest level of information distinguishing between pattern-consistent and inconsistent structure would be a triplet, or three consecutive events.] Pattern-consistent triplets were those that occurred within the sequence, whereas pattern-inconsistent triplets were those that never occurred during sequence blocks, and could only have occurred during the random blocks. The production of more pattern consistent triplets in the inclusion than the exclusion block reflects control over sequence knowledge and hence explicit sequence knowledge. Since there were 12 unique triplets in the 12-element repeating sequence and 64 possible triplets overall, one would expect a 0.188 proportion of consistent triplets by chance. Single-sample t tests carried out on the four conditions revealed that only the young Inclusion condition exceeded chance, t(11) = 2.42, p = 0.05. These data were also submitted to an Age Group × Instruction mixed factorial ANOVA with Instruction as a within subject variable. No main effect or interaction reached significance indicating that neither the difference in Instructions nor the Group differences in this variable varied significantly. Thus, it was concluded that while the t-test data suggested that young adults had some indication of explicit control in their knowledge of the sequence (reflected in their ability to produced more pattern consistent triplets than would be expected by chance when instructed to replicate the sequence), their amount of and control of this knowledge did not differ significantly from older adults who were at chance on all measures of explicit awareness.

On the recognition task participants were presented with sequences of 24 events on each of 20 trials. After observing the sequence they were asked to evaluate whether it had occurred during the scanner session. They were asked to respond using a scale of 1 (certain it did not) to 4 (certain it did). On half the trials the events consisted of two repetitions through the sequence they observed during learning (beginning at a random starting point in the sequence). On the remaining trials the events were produced by a foil sequence made up of the learning sequence in reverse (again beginning at a random starting point). The regularity was not mentioned, and no feedback was provided.

The recognition data were analyzed by determining the mean recognition response (as indexed by their response to the level of certainty that each trial was old). The mean recognition response for each trial presented in the recognition test was similar for both young (sequence: 2.51, random: 2.43) and older adults (sequence: 2.54, random: 2.37). Paired t-tests in each age group revealed no significant difference between the two trial types [young: t(11) = 1.70, p = 0.12; old: t(11) = 1.03, p = 0.33]. Thus, despite exhibiting implicit learning of the sequence structure, participants were unable to express any explicit knowledge through the recognition task. This is consistent with previous findings using a second-order sequence.

Thus, when taken together, all 3 measures suggest that neither group gained declarative knowledge or explicit control over the sequence structure.

EL

During the two EL runs, participants performed a category classification task, which served as the encoding phase for a surprise memory test after the scanning session. Each EL run consisted of 112 words, displayed individually for 1500 ms and followed by an inter-trial fixation period, which varied randomly between 500 and 1250 msec.

During the encoding phase in the scanner, participants were asked to make a semantic judgment pertaining to each word. On each trial, a single word was displayed in the center of the screen. Below the word, the first letter of the four category alternatives (a, p, o, j) was displayed in order to remind participants about the possible responses. Participants were instructed to respond as quickly and accurately as possible with a button press corresponding to the category to which the word belonged. Encoding was incidental, as participants were unaware of a subsequent memory test.

During the recognition test, which followed approximately 20 minutes after the scanning session, participants were presented with the 208 old words intermixed with 80 new words, from the same four categories. They were asked to make old/new judgments and indicate their confidence (definitely old, probably old, probably new, definitely new). Again, words were presented one at a time in the center of a computer screen. The memory/confidence choice was displayed below each word. Words were presented for 3 seconds, during which time participants pressed a key corresponding to their memory for the word. [The behavioral results have been reported previously (Dennis, Daselaar et al., 2007).]

fMRI Methods

Scanning & Image Processing

Images were collected using a 4T GE scanner. Stimuli were presented using liquid crystal display goggles (Resonance Technology, Northridge, CA) and behavioral responses were recorded using a four button fiber optic response box (Resonance Technology). Scanner noise was reduced with earplugs and head motion was minimized using foam pads and a headband. Anatomical scans began by first acquiring a T1-weighted sagittal localizer series. The anterior (AC) and posterior commissures (PC) were identified in the mid-sagittal slice and 34 contiguous oblique slices were prescribed parallel to the AC-PC plane. High resolution T1-weighted structural images were acquired with a 12 ms repetition time (TR), a 5 ms echo time (TE), 24 cm field of view (FOV), 68 slices, 1.9 mm slice thickness, 0 mm spacing, and 256 × 256 matrix. Echoplanar functional images were acquired using an inverse spiral sequence with a 1500 ms TR, 31 ms TE, 24 cm FOV, 34 slices, 3.8 mm slice thickness, resulting in cubic 3.8 mm3 isotropic voxels, and 64 × 64 image matrix.

Data were processed using SPM2 (Statistical Parametric Mapping; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). The first six volumes were discarded to allow for scanner equilibration. Time-series were then corrected for differences in slice acquisition times, and realigned. Functional images were spatially normalized to a standard stereotactic space, using the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) templates implemented in SPM2 and resliced to a resolution of 3.75 mm3. The coordinates were later converted to Talairach and Tournoux’s space (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988) for reporting in Tables. Finally, the volumes were spatially smoothed using an 8-mm isotropic Gaussian kernel and proportionally scaled to the whole-brain signal.

fMRI analyses

For each participant, trial-related activity was modeled with a stick function corresponding to stimulus onsets, convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF) within the context of the GLM, as implemented in SPM2. Confounding factors (head motion, magnetic field drift) were also included in the model. According to our motion parameters no participant moved more than 3 mm in any direction either within or across runs. Thus, no data was eliminated in either age group due to motion artifacts.

Statistical Parametric Maps were identified for each participant by applying linear contrasts to the parameter estimates (beta weights) for the events of interest, resulting in a t-statistic for every voxel. For the EL task both high and low confidence subsequent hits and misses were coded, and for the IL task correct trials from both sequence and random trials (incorrect trials were also modeled, yet treated as a regressor of no interest. The use of correct-only trials mirrors behavioral results conducted on RT data in SRT studies). Our analyses included 2 main contrasts: For the SRT task IL was defined as neural activity associated with sequence > random trials, and for the subsequent memory task EL was defined as neural activity associated with subsequent high confidence hits > subsequent misses. [Different analyses of the episodic encoding data were reported in a previous paper (Dennis, Daselaar et al., 2007)]. Both contrasts were conducted in first-level analyses.

In order to assess group effects on each task, random effects analyses were performed on each contrast of interest, in each age group using a significance threshold of p <0.005 with an extent threshold of 10 voxels [It has been argued that this threshold produces a desirable balance between Type I and Type II error rate (Lieberman and Cunningham, 2009)]. Next, in our assessment of age effects, the forgoing group results were subsequently used as an inclusive mask for identifying aging effects using direct contrasts between groups at p < .05 with an extent threshold of 10 contiguous voxels. Thus, we are assured that the regions we identified through this double analysis approach were of primary importance to the task in one group [showed a significant leaning effect (IL or EL) within one of the groups (p<.005, 10 voxels)], and were also used significantly less in the second group [showed a significant age group difference, (p<.05, 10 voxels)]. The conjoint probability following inclusive masking approached p < .00025 (Fisher, 1950; Lazar et al., 2002), but this estimate should be taken with caution given that the contrasts were not completely independent.

Next, in order to test our theory of dedifferentiation in learning systems, individual subject contrasts for each learning effect were submitted to a 2 (age: young v. old) × 2 (task: IL v EL) ANOVA using SPM5. Base upon our hypothesis we idenified 2-way interactions in a priori regions of interest (ROIs), specifically the MTL and striatum, at p <0.05, with an extent threshold of 10 voxels. ROIs were constructed by apply masks of each region to the 2-way interaction analysis using an anatomical library (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002) available within SPM5.

Finally, in order to assess whether there existed neural competition between the striatum and MTL in younger adults and whether this competition was attenuated in older adults we performed correlational analyses on the learning-related data in each of the regions identified in the ANOVA [i.e., left and right MTL, right caudate and putamen (see below)]. Specifically, we obtained the mean EL and IL activity for each participant, for each region. Then we assessed the significance of correlations within each age group, between MTL and striatal structures for each learning measure. As a second step we also tested whether there was a significant age-group difference between the correlations for each age group.

Results

Behavioral

EL

As noted previously (Dennis, Daselaar et al., 2007), participants responded incorrectly during encoding less than 1% of the time, leading to the inclusion of all trials in the analyses. Table 2A lists the proportion of hits and false alarms (FAs) within each confidence level for both age groups, as well as encoding reaction times (RTs) for subsequently remembered and forgotten items. A 2 (group: young, old) × 2 (memory: hits, false alarms) × 2 (confidence: high, low) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of memory, F(1, 1) = 172.47, p < 0.001, with participants showing significantly more hits than FAs overall, and a significant main effect of confidence, F(1, 1) = 19.53, p = 0.002, showing greater high (vs. low) confidence responding overall. Neither the main effect of group, nor any interaction involving group reached significance. To ensure that activation differences between remembered and forgotten trials were not confounded with differences in time-on-task, two-sample t-tests were conducted to compare encoding RTs for subsequently remembered vs. forgotten words. These tests revealed no significant differences within either group. Furthermore, a 2 (group: young, old) × 2 (subsequent memory: remembered, forgotten) ANOVA on encoding RTs revealed no significant main effects or interactions. Thus activation differences between subsequently remembered and forgotten words cannot be a result of greater looking time or exposure during encoding.

Table 2.

Behavioral Results

| A. EL |

High Confidence |

Low Confidence |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | Older | Young | Older | |||

| Accuracy | ||||||

| Hits | .83(.13) | .81(.15) | .48(.12) | .43(.11) | ||

| FAs | .16(.16) | .26(.25) | .26(.13) | .24(.14) | ||

| Encoding RTs | ||||||

| Hits | 842(91) | 878(71) | 827(92) | 871(80) | ||

| Misses | 829(85) | 892(97) | 841(100) | 875(68) | ||

| B. IL | Run 1 | Run 2 | Run 3 | |||

| Sequence | Ramdom | Sequence | Ramdom | Sequence | Ramdom | |

| Accuracy | ||||||

| Young | 0.98(.02) | 0.97(.03) | 0.95(.09) | 0.96(.07) | 0.96(.06) | 0.95(.07) |

| Older | 0.93(.08) | 0.95(.07) | 0.96.07) | 0.93(.07) | 0.96(.03) | 0.97(.03) |

| RT | ||||||

| Young | 407(72) | 423(87) | 410(60) | 408(59) | 403(54) | 422(57) |

| Older | 464(69) | 472(76) | 462(69) | 478(69) | 449(79) | 469(79) |

Mean and standard deviation for accuracy and response time (RT) data for the both young and older adults in the explicit learning (EL) and implicit learning (IL) tasks. FA: false alarms

IL1

RT: Participants responded to 98% of the trials. Trials which did not elicit a response were coded as incorrect. Table 2B lists both accuracy and response time, broken down by condition (sequence, random). A 2(Group: young, old) × 2 (Trial Type: sequence, random) × 3 (Run: 1-3) ANOVA on the RT measure revealed a main effect of trial type [F(1,21) = 15.87, p <0.001] and a marginal Trial Type × Run interaction [F(2,42) = 2.79, p =0.07].

Imaging

Main effects of Aging on Task

Young adults

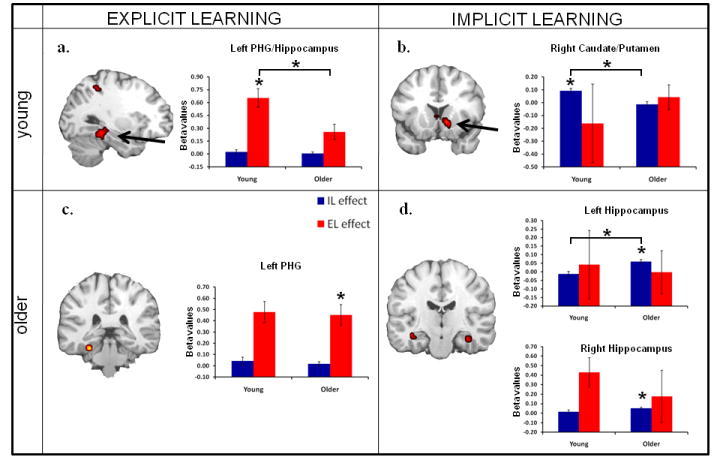

For EL younger adults activated a network of regions consistent with previous studies of subsequent memory, including left hippcampus/parahippocampal gyrus (PHG) (activation displayed in Figure 1a), visual cortex, left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), and left superior parietal cortex (See Table 3). Consistent with our predictions, EL activity in the MTL was significantly greater than that found in older adults (see Table 3, Age-effects t-values).

Figure 1. Learning-related activations for each age group and age effects therein.

fMRI learning effects for both explicit and implicit learning in young and older adults. Bar graphs represent mean beta values (effect sizes) for either explicit learning (red) or implicit learning (blue) activity in each region. PHG: parahippocampal gyrus. Asterisks (*) indicate significant learning effects in each age group displayed in the figure as well as a significant age effect (denoted by *t values in Table 2)

Table 3.

Explicit and Implicit learning-related activation for Young and Older adults

| Coordinates (T&T) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | BA | x | y | z | t | voxels | |

| Explicit Learning | |||||||

| Young | |||||||

| DLPFC | L | 9/44 | -49 | 9 | 24 | 4.73 | 14 |

| Hippocampus/post. PHG | L | -26 | -34 | -14 | 5.76 | 48 | |

| Precuneus | L | 7/40 | -23 | -42 | 44 | 7.37 | 62 |

| Occipito-temporal ctx | L | 37/19 | -56 | -52 | -10 | 4.29 | 16 |

| Occipito-parietal ctx | L | 19/7 | -23 | -72 | 39 | 5.58 | 42 |

| R | 18/19/7 | 26 | -92 | 5 | 5.38 | 65 | |

| Occipital ctx | L | 17/18 | -19 | -85 | -5 | 4.05 | 25 |

| Older | |||||||

| VLPFC/DLPFC | L | 44/45/46 | -41 | 30 | 9 | 5.15 | 78 |

| Post. PHG | L | 20/36 | -26 | -34 | -17 | 5.13 | 12 |

| VMPFC | L | 11/47 | -23 | 29 | -14 | 4.70 | 17 |

| DLPFC | L | 8/9 | -49 | 13 | 34 | 4.25 | 12 |

| Superior temporal gyrus | L | 21 | -56 | -44 | 6 | 4.06 | 10 |

| Implicit Learning | |||||||

| Young | |||||||

| DLPFC | L | 10 | -23 | 46 | 26 | 4.87 | 12 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | L | 6 | -11 | -19 | 67 | 5.75 | 21 |

| R | 6 | 30 | -12 | 57 | 3.72 | 17 | |

| Putamen/Caudate | R | 11 | 11 | -4 | 8.19 | 31 | |

| Putamen | R | 30 | -18 | 4 | 3.62 | 10 | |

| Thalamus | L | -23 | -14 | 22 | 6.69 | 96 | |

| Caudate (subpeak) | L | -4 | 8 | 3 | 3.62 | ||

| Posterior cingulate | R | 29/30 | 11 | -36 | 12 | 5.19 | 81 |

| Cerebellum | M | 8 | -52 | -4 | 6.70 | 64 | |

| Older | |||||||

| Hippocampus | L | -38 | -19 | -12 | 4.86 | 11 | |

| R | 38 | -12 | -15 | 4.47 | 14 | ||

| DLPFC | L | 10 | -19 | 41 | 15 | 4.11 | 19 |

DLPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; VLPFC: ventrolateral PFC; ctx: cortex; PHG: parahippocampal gyrus; VMPFC: ventromedial PFC

For IL younger adults activated a network of regions consistent with previous studies of implicit sequence learning including bilateral caudate, right putamen (activation displayed Figure 1b), bilateral superior frontal gyrus, posterior cingulate, and cerebellum (See Table 3). Consistent with our predictions, IL activity in the striatum was significantly greater than that found in older adults (see Table 3, Age-effects t-values).

Older adults

For EL older adults activated left parahippocampal gyrus (activation displayed in Figure 1c), left superior temporal gyrus, and several regions in left PFC including both ventromedial, ventrolateral, and dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC). (See Table 3). EL activity in ventromedial PFC was significantly greater than that found in younger adults (see Table 3, Age-effects t-values).

For IL older adults activated regions bilateral hippocampus/PHG (activation displayed in the Figure 1d) and left DLPFC. (See Table 3). Consistent with our predictions, MTL (left hippocampus) activity was significantly greater in older, compared to younger adults (see Table 3, Age-effects t-values).

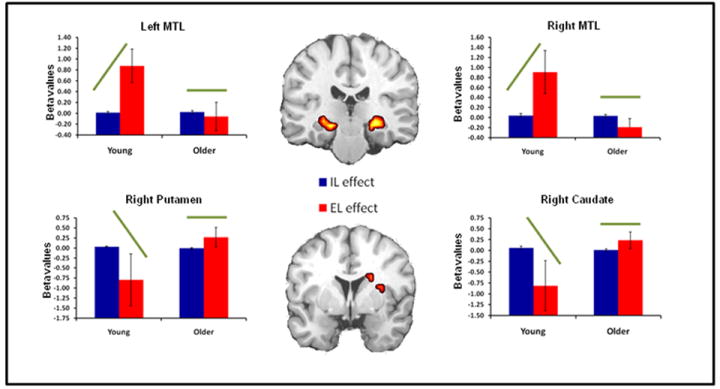

Age × Task Interactions

Consistent with our predictions, we found Age × Task interactions in MTL and striatal regions. These interactions occurred in bilateral hippocampus, right caudate and right putamen (see Table 4). All four regions as well as activation bars for each learning task from young and older adults are displayed in Figure 2. As illustrated by the bar graphs in this figure, these interactions occurred in regions that showed significant differences between EL and IL in young but not in older adults. The results from young adults are consistent with the dissociation between declarative and nondeclarative memory: bilateral MTL showed greater activity for EL than IL, whereas the right striatum showed greater activity for IL than EL. In contrast, older adults did not show these differences.

Table 4.

Age × Task interactions within the striatum and MTL

| coordinates (T&T) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | BA | x | y | z | t | voxels | |

| - | - | ||||||

| Hippocampus | L | 23 | -30 | 11 | 9.53 | 51 | |

| - | |||||||

| R | 23 | -30 | 11 | 9.31 | 49 | ||

| Caudate | R | 19 | 1 | 21 | 6.58 | 19 | |

| Putamen | R | 26 | -3 | 11 | 5.52 | 13 | |

Figure 2. Age × Task interactions.

Age × Task interactions within the MTL and striatum. Bar graphs represent mean beta values (effect sizes) for both implicit and explicit learning activity in each region. Green bars indicate effect direction driving the significant interaction in each region.

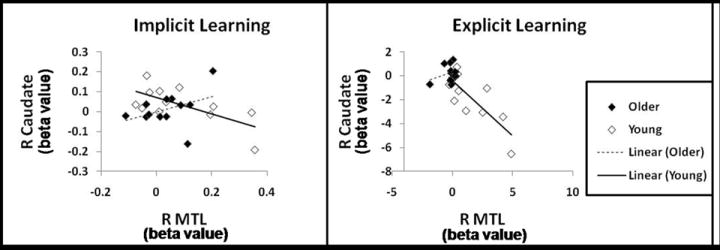

Correlational Analyses

Young adults

Young adults exhibited a significant negative correlation between EL activity in the left MTL and right caudate (r = -0.63, p <.05) and right putamen (r = -0.72, p <.01) as well as between right MTL and right caudate (r = -0.77, p <.01) and right putamen (r = -0.84, p <.001). Young adults also exhibited negative correlations between IL activity in both MTL regions and right caudate and putamen, however, only the correlation between right MTL and right caudate reached significance (r = -0.62, p <.05). (see Table 5)

Table 5.

Correlations of neural activations

| Young | Older | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | z | p | |

|

EL |

||||||

| LMTL-Rcaud | -0.63 | 0.0279 | 0.39 | 0.2228 | 2.42 | <0.05 |

| LMTL-Rput | -0.72 | 0.0061 | -0.58 | 0.0479 | 0.54 | n.s. |

| LMTL-RMTL | 0.94 | <0.0001 | 0.93 | <0.0001 | -0.22 | n.s. |

| RMTL-Rcaud | -0.77 | 0.0022 | 0.29 | 0.3778 | 2.78 | <.01 |

| RMTL-Rput | -0.84 | 0.0002 | -0.6 | 0.0359 | 1.11 | n.s. |

|

IL |

||||||

| LMTL-Rcaud | -0.46 | 0.1398 | 0.31 | 0.3312 | 1.73 | n.s. |

| LMTL-Rput | -0.22 | 0.5072 | -0.15 | 0.6451 | 0.15 | n.s. |

| Rcaud-Rput | 0.79 | 0.0015 | 0.09 | 0.7938 | 2.06 | <.05 |

| RMTL-Rcaud | -0.62 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.2188 | 2.4 | <.05 |

| RMTL-Rput | -0.42 | 0.1842 | 0.24 | 0.4678 | 1.45 | n.s. |

L: left; R: right; MTL: medial temporal lobe; caud: caudate; put: putamen; italics and bold indicate significance

Older adults

Correlations between the MTL and striatum in older adults were all attenuated compared to that seen in the young. For EL activity, older adults only exhibited a negative correlation between left MTL and right putamen (r = -0.58, p =.05) and right MTL and right putamen (r = -0.6, p <.05). For IL activity no correlation reached significance. (see Table 5)

Moreover, for both EL and IL activity, the negative correlations between MTL regions and the right caudate were significantly larger in young than then were in older adults. Results suggest that while young adults mainatained a competitive relationship between the striatum and MTL, this competitve relationship is reduced in aging. (see Table 5)

Discussion

The results yielded three main findings. First, young adults showed a clear dissociation between declarative and nondeclarative memory, significantly activating MTL for EL and the striatum for IL, whereas older adults did not. While older adults did activate the MTL for EL (albeit exhibiting age deficits in this activity), they did not exhibit striatal activity for IL, but bilateral MTL activity (see Figure 1). Second, bilateral hippocampal, right caudate, and right putamen regions showed significant Age × Task interactions, with young but not older adults exhibiting differentiation in learning-related activity, again confirming a dedifferentiation of memory systems in older adults (see Figure 2). Finally, while an opposing relationship between declarative and nondeclarative memory systems was additionally confirmed in young adults by negative correlations between MTL and striatal activity, these correlations were attenuated in older adults, consistent with the dedifferentiation hypothesis.

For the EL task, young adults exhibited significant activation in the left hippocampus, extending into left PHG (see Figure 1a). This finding replicates previous imaging tasks investigating EL of episodic encoding (e.g., Brewer et al., 1998; Kirchhoff et al., 2000; Prince et al., 2005; Wagner et al., 1998). Older adults, while also exhibiting MTL activity for EL, activated a slightly more lateral region of left PHG (see Fig. 1c). However, a direct contrast between age groups indicated that young adults exhibit significantly more EL activation in left hippocampus compared to older adults (see Table 2 and activation bars in Figure 1a).

Age-related reductions in MTL activity during subsequent memory tasks is a common finding in studies of aging (Dennis, Kim et al., 2007; Gutchess et al., 2005; Morcom et al., 2003). During episodic encoding the MTL, and more specifically the hippocampus, is associated with the successful encoding of true item-specific details of the encoding event. Reduced hippocampal activity in aging suggests that older adults do not encode the same quality or amount of detail as young adults for later memory retrieval (Dennis et al., 2008). Consistent with the foregoing studies, the current results suggest that older adults are unable to utilize the MTL in EL to the same extent as young adults.

Focusing on IL, young adults exhibit significant IL activity in bilateral caudate and right putamen (see Figure 1c), as well as greater IL activity in right striatum compared to older adults. On the other hand, older adults exhibit significant IL activity in bilateral MTL (hippocampus) (see Figure 1d), as well as greater IL activity in left hippocampus compared to young adults. The finding of striatal-mediated IL in young adults replicates previous imaging studies (e.g., Daselaar, Rombouts et al., 2003; Grafton et al., 1995; Hazeltine et al., 1997; Rauch, Whalen et al., 1997). Furthermore, like that found in the current study, striatal activity is often right lateralized in SRT studies (Doyon et al., 1996; Grafton et al., 1995; Rauch et al., 1995; Rauch, Whalen et al., 1997). While the basis of this lateralization is not well understood it has been suggested that it may emerge from the spatial nature of the task and be associated with right-hemisphere dominance of non-verbal and spatial processes (Jonides et al., 1996; Rauch, Whalen et al., 1997).

While the single previous study to date examining age differences in IL using the SRT task found no age-related differences in striatal activity (Daselaar, Rombouts et al., 2003), other studies examining aging and IL (non-declarative learning) using probabilistic categorization learning (Fera et al., 2005) and a modified SRT task (Aizenstein et al., 2005) have identified age-related reductions in striatal activity. While results from the current study support the latter findings, it is unclear what may underlie differences between our study and that of Daselaar and colleagues. One difference is that the Daselaar study employed a blocked design, which confounds the measurement of both transient and sustained activity, whereas the current study was an event-related design, measuring transient activity alone. Previous work has demonstrated that aging effects each type of neural processing (Dennis, Daselaar et al., 2007), and suggests that differences between studies may rest in how neural activity is measured. Additionally, several demographic differences between participants in the two studies may have accounted for the observed differences in neural recruitment. First, the young participants in the Daselaar study were older (range: 30-35yrs) than the participants in the current study (range 18-30yrs), making the age gap less pronounced. The older participants in the Daselaar study also had a slightly lower MMSE scores (range 25-30; average: 27.8) than found in the current study (range 29-30; average: 29.8). To the extent that the observed dedifferentiation represents a compensatory mechanism supporting task performance, it may be that the current sample of older adults were slightly higher functioning and thus able to take advantage of this mechanism.

As noted, the other striking difference between the two sets of results is the presence of age-related MTL activity in the current study. That is, despite the aforementioned age-related reduction in striatal activation, older adults do exhibit significant IL activity in bilateral hippocampus, and significantly greater IL activity in left hippocampus compared to young adults. Furthermore, in addition to the PFC (see below), bilateral hippocampus was the only region to show a significant IL effect in older adults. So the question arises, what type of learning does the MTL provide older adults? One possibility is that older adults are learning the sequence task explicitly, whereas young adults are maintaining an implicit representation of their sequencing knowledge. However, there exists no evidence of declarative knowledge in either age group, making this scenario unlikely.

A more pragmatic possibility is that the MTL is supporting temporal-spatial learning in older adults during sequence learning. The role of the MTL in mediating spatial learning and spatial relationships in young adults is well documented in the literature (e.g., Davachi, 2006; Eichenbaum, 2000; Ekstrom and Bookheimer, 2007; Ross and Slotnick, 2008) and complex multi-event contingences (Chun and Phelps, 1999; Clark and Squire, 1998; Greene et al., 2007; Poldrack et al., 2001; Rose et al., 2002), even under implicit learning conditions. Though not typical, MTL involvement in learning spatial and response contingences in the SRT task would be consistent with task goals and thus recruited by older adults.

Supporting this conclusion is also the age-related increase in dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC) activity found for IL. Increased MTL and DLPFC activity is often associated with increased working memory demands and the encoding of complex relationships (Blumenfeld and Ranganath, 2006; Schon et al., 2009). It is possible that the age-related increase in activity in both regions is indicative of increased working memory processing needed to encode, maintain and respond to the complex sequence structure employed in the current study. Again, while not the typical IL finding, MTL activation during the SRT has been observed in previous studies (Rauch, Savage et al., 1997; Schendan et al., 2003). Consistent with Schendan and colleagues (2003) who found implicit SRT learning in anterior MTL regions and explicit learning in more posterior regions our result too show relatively anterior MTL/hippocampal involvement in IL in older adults; again strengthening the conclusion that learning was implicit. Why older adults utilize this MTL learning system while younger adults utilize the more typically observed striatal system remains a question. The answer may be based upon both the ability of the MTL to handle such learning and the breakdown of specialized neural systems in older adults.

In order to further investigate age differences in the specialization of brain regions mediating IL and EL we performed a Learning Effect × Age ANOVA within our a priori ROIs, the striatum and MTL. We identified four regions that showed a significant interaction: bilateral hippocampus, right caudate and right putamen (see Figure 2). Examination of the IL and EL effects and activation bars indicates that while young adults show differentiated activation in all four regions, older adults do not. In fact, despite exhibiting significant MTL activation for implicit learning, and age-related deficits in MTL activity for explicit learning, older adults show equivalent learning-related activity in this region for both tasks. A similar pattern in observed in the striatum as well. Results expand upon previous research identifying dedifferentiation in visual cortex (Grady et al., 1994; Park et al., 2004) as well as age-related reductions in hemispheric asymmetry in frontal cortices (for a review see Cabeza, 2002), finding that brain regions that were once highly specialized for certain cognitive processing become less specialized in aging.

The lack of dissociation between learning systems is not without precedent. Previously, work by Rauch and colleagues (1997) examining patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder observed no striatal, but bilateral MTL activity associated with non-declarative sequence learning. Additionally, Moody and colleagues (2004) found Parkinson’s patients (known for disrupted striatal functioning) to exhibit an attenuated inverse relationship between positive striatal and negative MTL activation during non-declarative learning in the weather prediction task. Together these results suggest that, under certain neurological conditions the dissociable and competitive relationship between the striatum and MTL may be attenuated.

Aging may also represent a state in which both striatal-frontal circuitry and MTL function are compromised such that additional learning mechanisms are needed to fulfill learning-related needs originally supported by one system or the other. As noted above, aging is associated with structural and functional changes in the striatum and MTL (Dennis and Cabeza, 2008; Raz, 2000, 2005) that have been suggested to compromise function in each region (Braver and Barch, 2002; Daselaar et al., 2006; Dennis and Cabeza, 2008; Grady et al., 2003; Li and Sikstrom, 2002). These age-related changes may compromise each learning system to the point where cooperation, not competition is the best means for accomplishing task goals.

This idea of increased cooperation and reduced competition between regions in aging was investigated in the current study by directly comparing learning-related activity in the foregoing regions. As noted, previous studies concluded not only that the MTL and striatum represent distinct learning systems, but that these systems operate in direct competition with one another (Jenkins et al., 1994; Packard, 1999; Poldrack and Gabrieli, 2001; Poldrack and Packard, 2003). That is, as activation in one system increases, activation in the other decreases (Poldrack et al., 2001). Such negative correlations within young participants were observed in the current study. That is, focusing on the regions identified in the ANOVA, young adults demonstrated a significant negative correlations between EL activity in both the caudate and putamen and bilateral MTL during the EL task (see Table 4). Correlations for IL activity between these regions were also negative in young adults, though only the right MTL-right caudate correlation reached significance. However, these negative correlations between learning systems were all attenuated in older adults. Additionally, in several instances correlations between regions (for EL: LMTL/Rcaudate and RMTL/Rcaudate; for IL RMTL/Rcaudate) in older adults significantly differed from those observed in young adults. The foregoing connectivity results also argue against both neural specialization and competition between learning systems in aging; again, supporting a conclusion of neural dedifferentiation in aging.

Baltes and Lindenberger (Baltes and Lindenberger, 1997) have long argued that aging is associated with a reduction in the degree to which behavior is differentiated. And previous studies have supported these behavioral findings with neural evidence from visual and frontal activations (Cabeza, 2002; Grady et al., 1994; Park et al., 2004). The current study extends these findings to show dedifferentiation between declarative and non-declarative learning systems. Such functional or neural compensation in aging is a well established response to the age-related changes found within neural networks (Cabeza, 2002; Dennis and Cabeza, 2008). That is, as a given region exhibits decline in its neural efficiency and recruitment, other regions have been shown to increase their activation in a compensatory manner to mediate cognitive functioning for the declining region. While this form of age-related compensation has been shown to occur in contralateral or adjacent regions (for reviews see Cabeza, 2002; Greenwood, 2007), given the aforementioned evidence of the MTL and striatal specialization and function, compensation in the form of dedifferentiation between the two learning systems appears an appropriate action in response to declining function in either system. Of course the underlying cause for such decline and subsequent dedifferentiation in the aging brain is a matter for further investigation.

It should also be noted that a majority of the research identifying neural dedifferentiation in aging does so in the absence of age-related changes in task performance. That is, older adults who exhibit dedifferentiation or reduced hemispheric asymmetry perform similarly to younger adults performing the same task (e.g., Cabeza et al., 2002; Daselaar, Veltman et al., 2003). Moreover, these same studies find that older adults who show such dedifferentiation outperform older adults who exhibit the same pattern of neural recruitment seen in younger adults performing the task. This pattern of expanded neural recruitment is thus suggested to act as a compensatory mechanism. Being that behavioral performance in both the EL and IL tasks did not differ between age groups in the current study, a similar conclusion can be drawn. That is, dedifferentiation of the two learning systems allows older adults to utilize the most effective processing available to them in order to maintain learning. While we did not find significant compensatory activity in the striatum for EL, as might be expected from full dedifferentiation, the pattern of activity across the IL task, ANOVA and correlations between the MTL and striatum are supportive of an age-related decrease in specialization and competition between these two regions, favoring dedifferentiation.

Limitations/Caveats

The present results should be treated with some caveats. First, the current study included a modest sample of participants (12 young and 12 older adults). Further research is needed to duplicate the current findings using a larger sample. Second, the present study found no behavioral difference between age groups in either the EL or IL tasks. While not necessarily an expected results, this is most likely due in part to the high education and generally high cognitive status of the older adults included in the study. In general we view this not so much as a limitation, but as an asset to the current analysis, in that we are able to investigate neural differences in the absence of behavioral differences. As noted above, the observed dedifferentiation may serve as a compensatory mechanism in the current sample of high-performing older adults, allowing them to recruit additional brain regions in order to maintain task demands. Comparisons between high and low performing older adults would help to clarify whether this is a ubiquitous change in aging, or associated only with a certain level of performance in aging. Third, the IL task used in the current study, the SRT task, is often regarded as a perceptual-motor IL task. As such, additional studies are warranted to investigate whether the current results generalize to IL tasks that are more motoric in nature (e.g., rotary pursuit). Finally, the current findings regarding the neural correlates of IL in aging differ from those found in a prior study by Daselaar and colleagues (2003). While several demographic and measurement differences between the two studies may underlie the observed difference in results, additional research is needed to further elucidate the precise mechanism which mediates age-related changes in neural recruitment during IL tasks.

Conclusions

The current results displayed evidence for dedifferentiation in aging across declarative and non-declarative learning systems. That is, while young adults showed differential recruitment of the striatum for IL and the MTL for EL, older adults did not. Moreover, younger, but not older adults exhibited significant competition in the form of negative correlations in neural activation between the two regions during both implicit and explicit tasks. Dedifferentiation of neural recruitment and the lack of competition between learning systems suggests that, in aging, these two systems become less specialized. Given the lack of age-related performance differences in both the implicit and explicit learning tasks, results suggest that such neural dedifferentiation is compensatory in older adults and supports the maintenance of cognitive functioning comparative to functioning observed in younger adults. While previous studies have identified dedifferentiation in perceptual regions, this is the first study to do so in learning-related regions.

Figure 3. Correlations In neural activations.

Scatterplots are presented for correlations in neural activity between the right caudate and right MTL for each age group, during both IL and EL. As indicated in Table 5, young adults exhibit significant negative correlations in neural activity between the two regions, whereas older adults do not.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Amber Baptiste Tarter, Rakesh Arya for help in data collection and analysis; Sander Daselaar and Steve Prince for helpful comments; and Jen Bittner and Jonathan Harris for help in manuscript preparation. This work was supported by the National Institute of Health [AG19731 and AG023770 to R.C. and T32 AG000029 to N.A.D.].

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

Behavioral data from 1 young adult in the IL task was lost due to a computer error in data collection. The following statistics reflect behavioral data from 11 participants.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aizenstein HJ, Butters MA, Clark KA, Figurski JL, Andrew Stenger V, Nebes RD, Reynolds CF, 3, Carter CS. Prefrontal and striatal activation in elderly subjects during concurrent implicit and explicit sequence learning. Neurobiology of Aging. 2005;27:741–751. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Lindenberger U. Emergence of a powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: a new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychology and Aging. 1997;12:12–21. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld RS, Ranganath C. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex promotes long-term memory formation through its role in working memory organization. J Neurosci. 2006;26:916–925. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2353-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braver TS, Barch DM. A theory of cognitive control, aging cognition, and neuromodulation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2002;26:809–817. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JB, Zhao Z, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD. Making memories: brain activity that predicts how well visual experience will be remembered. Science. 1998;281:1185–1187. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R. Hemispheric asymmetry reduction in older adults: the HAROLD model. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:85–100. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Anderson ND, Locantore JK, McIntosh AR. Aging gracefully: compensatory brain activity in high-performing older adults. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1394–1402. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun MM, Phelps EA. Memory deficits for implicit contextual information in amnesic subjects with hippocampal damage. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:844–847. doi: 10.1038/12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RE, Squire LR. Classical conditioning and brain systems: the role of awareness. Science. 1998;280:77–81. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, Eichenbaum H, Deacedo BS, Corkin S. Different memory systems underlying acquisition of procedural and declarative knowledge. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1985;444:54–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb37579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, Ryan J, Hunt C, Romine L, Wszalek T, Nash C. Hippocampal system and declarative (relational) memory: summarizing the data from functional neuroimaging studies. Hippocampus. 1999;9:83–98. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:1<83::AID-HIPO9>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Fleck MS, Dobbins IG, Madden DJ, Cabeza R. Effects of healthy aging on hippocampal and rhinal memory functions: an event-related fMRI study. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;16:1771–1782. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Rombouts SA, Veltman DJ, Raaijmakers JG, Jonker C. Similar network activated by young and old adults during the acquisition of a motor sequence. Neurobiology of Aging. 2003;24:1013–1019. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(03)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Veltman DJ, Rombouts SA, Raaijmakers JG, Jonker C. Neuroanatomical correlates of episodic encoding and retrieval in young and elderly subjects. Brain. 2003;126:43–56. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L. Item, context and relational episodic encoding in humans. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2006;16:693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SW, Dennis NA, Daselaar SM, Fleck MS, Cabeza R. Que PASA? The posterior-anterior shift in aging. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18:1201–1209. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis NA, Cabeza R. Neuroimaging of Healthy Cognitive Aging. In: Salthouse TA, Craik FEM, editors. Handbook of Aging and Cognition. 3. New York: Psychological Press; 2008. pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis NA, Daselaar S, Cabeza R. Effects of aging on transient and sustained successful memory encoding activity. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007;28:1749–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis NA, Hayes SM, Prince SE, Huettel SA, Madden DJ, Cabeza R. Effects of aging on the neural correlates of successful item and source memory encoding. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 2008;34:791–808. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.34.4.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis NA, Howard JH, Jr, Howard DV. Implicit sequence learning without motor sequencing in young and old adults. Exp Brain Res. 2006;175:153–164. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0534-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis NA, Kim HK, Cabeza R. Effects of aging on the neural correlates of true and false memory formation. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:3157–3166. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destrebecqz A, Cleeremans A. Can sequence learning be implicit? New evidence with the process dissociation procedure. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2001;8:343–350. doi: 10.3758/bf03196171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon J, Owen AM, Petrides M, Sziklas V, Evans AC. Functional anatomy of visuomotor skill learning in human subjects examined with positron emission tomography. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;8:637–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H. Conscious awareness, memory and the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:775–776. doi: 10.1038/12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H. Hippocampus: mapping or memory? Curr Biol. 2000;10:R785–787. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00763-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H. The hippocampus and declarative memory: cognitive mechanisms and neural codes. Behavioural Brain Research. 2001;127:199–207. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00365-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom AD, Bookheimer SY. Spatial and temporal episodic memory retrieval recruit dissociable functional networks in the human brain. Learn Mem. 2007;14:645–654. doi: 10.1101/lm.575107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fera F, Weickert TW, Goldberg TE, Tessitore A, Hariri A, Das S, Lee S, Zoltick B, Meeter M, Myers CE, Gluck MA, Weinberger DR, Mattay VS. Neural mechanisms underlying probabilistic category learning in normal aging. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:11340–11348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2736-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RA. Statistical methods for Research Workers. London: Oliver and Boyd; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Grady CL, Maisog JM, Horwitz B, Ungerleider LG, Mentis MJ, Salerno JA, Pietrini P, Wagner E, Haxby JV. Age-related changes in cortical blood flow activation during visual processing of faces and location. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:1450–1462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01450.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady CL, McIntosh AR, Craik FI. Age-related differences in the functional connectivity of the hippocampus during memory encoding. Hippocampus. 2003;13:572–586. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafton ST, Hazeltine E, Ivry I. Functional mapping of sequence learning in normal humans. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1995;7:497–510. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1995.7.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AJ, Gross WL, Elsinger CL, Rao SM. Hippocampal differentiation without recognition: an fMRI analysis of the contextual cueing task. Learn Mem. 2007;14:548–553. doi: 10.1101/lm.609807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood PM. Functional plasticity in cognitive aging: review and hypothesis. Neuropsychology. 2007;21:657–673. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.6.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutchess AH, Welsh RC, Hedden T, Bangert A, Minear M, Liu LL, Park DC. Aging and the neural correlates of successful picture encoding: frontal activations compensate for decreased medial-temporal activity. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2005;17:84–96. doi: 10.1162/0898929052880048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazeltine E, Grafton ST, Ivry R. Attention and stimulus characteristics determine the locus of motor- sequence encoding. A PET study. Brain. 1997;120:123–140. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heindel WC, Salmon DP, Shults CW, Walicke PA, Butters N. Neuropsychological evidence for multiple implicit memory systems: A comparison of Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and Parkinson’s Disease patients. Journal of Neuroscience. 1989;9:582–587. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-02-00582.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DV, Howard JH., Jr Adult age differences in the rate of learning serial patterns: evidence from direct and indirect tests. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:232–241. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DV, Howard JH, Jr, Japikse K, DiYanni C, Thompson A, Somberg R. Implicit sequence learning: effects of level of structure, adult age, and extended practice. Psychol Aging. 2004;19:79–92. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins IH, Brooks DJ, Nixon PD, Frackowiak RS, Passingham RE. Motor sequence learning: a study with positron emission tomography. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3775–3790. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03775.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J, Reuter-Lorenz PA, Smith EE, Awh E, Barnes LL, Drain HM, Glass J, Lauber E, Schumacher E. verbal and spatial working memory. In: Medin D, editor. Psychology of Learning and Motivation. 1996. pp. 43–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff BA, Wagner AD, Maril A, Stern CE. Prefrontal-temporal circuitry for episodic encoding and subsequent memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6173–6180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06173.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton BJ. In: The role of the basal ganglia in learning and memory Neuropsychology of memory. 3. Squire LR, Schacter DL, editors. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton BJ, Mangels JA, Squire LR. A neostriatal habit learning system in humans. Science. 1996;273:1399–1402. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar NA, Luna B, Sweeney JA, Eddy WF. Combining brains: a survey of methods for statistical pooling of information. Neuroimage. 2002;16:538–550. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SC, Sikstrom S. Integrative neurocomputational perspectives on cognitive aging, neuromodulation, and representation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2002;26:795–808. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD, Cunningham WA. Type I and Type II error concerns in fMRI research: re-balancing the scale. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2009;4:423–428. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RJ, White NM. A triple dissociation of memory systems: hippocampus, amygdala, and dorsal striatum. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:3–22. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JA, Hall G. Caudate-putamen lesions in the rat may impair or potentiate maze learning depending upon availability of stimulus cues and relevance of response cues. Q J Exp Psychol B. 1988;40:243–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody TD, Bookheimer SY, Vanek Z, Knowlton BJ. An implicit learning task activates medial temporal lobe in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:438–442. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.2.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcom AM, Good CD, Frackowiak RSJ, Rugg MD. Age effects on the neural correlates of successful memory encoding. Brain. 2003;126:213–229. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen MJ, Bullemer P. Attentional requirements of learning: Evidence from performance measures. Cognitive Psychology. 1987;19:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Packard MG. Glutamate infused posttraining into the hippocampus or caudate-putamen differentially strengthens place and response learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12881–12886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard MG, Hirsh R, White NM. Differential effects of fornix and caudate nucleus lesions on two radial maze tasks: evidence for multiple memory systems. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1465–1472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-05-01465.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paller KA, Wagner AD. Observing the transformation of experience into memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2002;6:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01845-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DC, Polk TA, Park R, Minear M, Savage A, Smith MR. Aging reduces neural specialization in ventral visual cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:13091–13095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405148101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Clark J, Pare-Blagoev EJ, Shohamy D, Creso Moyano J, Myers C, Gluck MA. Interactive memory systems in the human brain. Nature. 2001;414:546–550. doi: 10.1038/35107080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Gabrieli JD. Characterizing the neural mechanisms of skill learning and repetition priming: evidence from mirror reading. Brain. 2001;124:67–82. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Packard MG. Competition among multiple memory systems: converging evidence from animal and human brain studies. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince SE, Daselaar SM, Cabeza R. Neural correlates of relational memory: successful encoding and retrieval of semantic and perceptual associations. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1203–1210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2540-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SL, Savage CR, Alpert NM, Dougherty D, Kendrick A, Curran T, Brown HD, Manzo P, Fischman AJ, Jenike MA. Probing striatal function in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A PET study of implicit sequence learning. Journal of Neuropsychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences. 1997;9:568–573. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SL, Savage CR, Brown HD, Curran T, Alpert NM, Kendrick A, Fischman AJ, Kosslyn SM. A PET investigation of implicit and explicit sequence learning. Human Brain Mapping. 1995;3:271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SL, Whalen PJ, Savage CR, Curran T, Kendrick A, Brown HD, Bush G, Breiter HC, Rosen BR. Striatal recruitment during an implicit sequence learning task as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Human Brain Mapping. 1997;5:124–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N. Aging of the brain and its impact on cognitive performance: Integration of structural and functional findings. In: Craik FI, Salthouse TA, editors. The Handbook of Aging and Cognition. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Raz N. The aging brain observed in vivo: differential changes and their modifiers. In: Cabeza R, Nyberg L, Park D, editors. Cognitive Neuroscience of Aging. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 19–57. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter-Lorenz PA, Jonides J, Smith EE, Hartley A, Miller A, Marshuetz C, Koeppe RA. Age differences in the frontal lateralization of verbal and spatial working memory revealed by PET. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12:174–187. doi: 10.1162/089892900561814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M, Haider H, Weiller C, Buchel C. The role of medial temporal lobe structures in implicit learning: an event-related FMRI study. Neuron. 2002;36:1221–1231. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RS, Slotnick SD. The hippocampus is preferentially associated with memory for spatial context. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008;20:432–446. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schendan HE, Searl MM, Melrose RJ, Stern CE. An FMRI study of the role of the medial temporal lobe in implicit and explicit sequence learning. Neuron. 2003;37:1013–1025. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon K, Quiroz YT, Hasselmo ME, Stern CE. Greater Working Memory Load Results in Greater Medial Temporal Activity at Retrieval. Cereb Cortex. 2009 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry DF, Schacter DL. The evolution of multiple memory systems. Psychological Review. 1987;94:439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Zola-Morgan S, Cave CB, Haist F, Musen G, Suzuki WA. Memory: organization of brain systems and cognition. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1990;55:1007–1023. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1990.055.01.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain. Stuttgart: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AD, Schacter DL, Rotte M, Koutstaal W, Maril A, Dale AM, Rosen BR, Buckner RL. Building memories: remembering and forgetting of verbal experiences as predicted by brain activity. Science. 1998;281:1188–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]