Abstract

A popular book recently hypothesized that change in atmospheric oxygen over geological time is the most important physical factor in the evolution of many fundamental characteristics of modern terrestrial animals. This hypothesis is generated primarily using fossil data but the present paper considers how modern experimental biology can be used to test it. Comparative physiology and experimental evolution clearly show that changes in atmospheric O2 over the ages had the potential to drive evolution, assuming the physiological O2-sensitivity of animals today is similar to the past. Established methods, such as phylogenetically independent contrasts, as well new approaches, such as adding environmental history to phylogenetic analyses or modeling interactions between environmental stresses and biological responses with different rate constants, may be useful for testing (disproving) hypotheses about biological adaptations to changes in atmospheric O2.

Keywords: comparative physiology, evolution, molecular clocks, paleophysiology, Permian mass extinction, phylogenetically independent contrasts

1. Introduction

Since animal life started evolving on earth some 550 million years ago (MYA), oxygen levels in the atmosphere have been radically different from the current value of nearly 21%. It has been hypothesized that change in oxygen over geological time is the most important physical factor in the evolution of many fundamental characteristics of modern terrestrial animals (Ward, 2006). However, this hypothesis and most of the interesting reports about the topic are correlative and primarily rely on fossil data. This paper considers how modern experimental biology might be used to test this hypothesis more rigorously.

2. Paleoatmospheric O2

Before discussing biological responses to changes in atmospheric levels of O2 over geological history, a brief review of the data for O2 levels is appropriate. This is a very interesting scientific problem in its own right that has been extensively reviewed elsewhere and has been summarized in excellent articles and books with a biological point of view (McAlester, 1970; Ward, 2006). Briefly, most of this data is geochemical and based on carbon-sulfur-oxygen cycles of oxidation and burial in sediments (Berner, 2004). Over 3.5 billion years ago, there was essentially no free O2 in the atmosphere and CO2 may have been 10,000 times the present levels. Free O2 started increasing in the atmosphere with the evolution of cyanobacteria that are thought to have evolved further into chloroplasts. These organelles produce O2 from photosynthesis and O2 levels were increasing by 2.3 billion years ago. Photosynthesis produces O2 that promotes weathering of land rocks and the production of iron oxides and soluble sulfate, which wash into the oceans. Biological processes such as bacterial sulfate reduction and photosynthesis cause depletion and enrichment of various carbon and sulfur isotopes that can be analyzed in sediments for changes over geologic time. Oxidation and burial of organic C and pyrite S are balanced over long time spans (≥ 50 MY), which supports the model that they are primary determinants of atmospheric O2. Photolysis of sulfur in the atmosphere can also affect isotope distributions and it is argued that this should be considered in inferring O2 levels from isotope data (Farquhar et al., 2000). However, there is general agreement on the major changes in atmospheric O2 over the past 600 MY (Fig. 1).

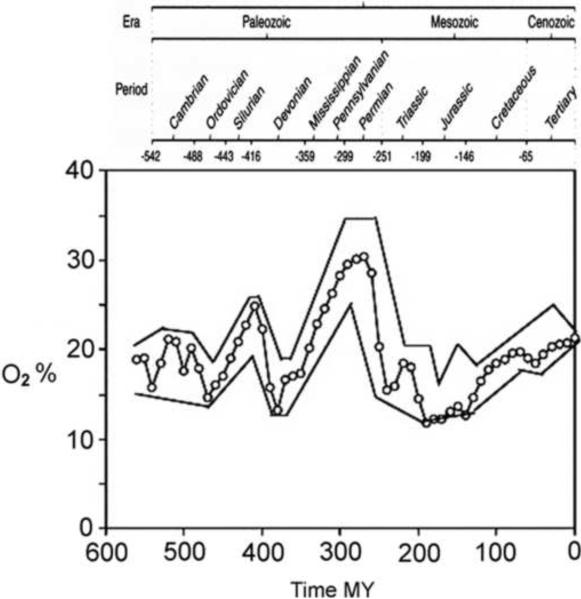

Figure 1.

O2 changes in the earth's atmosphere over the past 600 million years with geological time scale shown at the top. (modified from Berner et al., 2007).

Figure 1 shows atmospheric O2 estimates with upper and lower boundaries over the past 600 MY. Notable features include large rises in O2 in the Silurian and Permian periods, peaking 420 MYA and 275 MYA, respectively. Both of these increases were followed by dramatic decreases in O2. There has been a relatively steady increase in O2 since the Jurassic period 200 MYA to the current level. These general trends are consistent with biological evidence about prevailing O2 levels inferred from the fossil record also (Ward, 2006). It is worth noting that the reverse approach of using the biological fossil record as an atmospheric O2 sensor over geologic time scales has been proposed too (Jon Harrison, personal communication). Harrison has pointed out how the density of leaf stomata has been a powerful tool for estimating the history of CO2 levels in the atmosphere (McElwain and Chaloner, 1996).

3. Hypotheses for biological response to changes in atmospheric O2

The idea that changes in atmospheric O2 affected the evolution and physiology of animals has been discussed frequently in the literature. One popular example is how O2 levels near 30% in the Permian could have supported the evolution of giant insects (Graham et al., 1995). Oxygen uptake in insects occurs primarily by diffusion in the tracheoles so higher atmospheric O2 levels will support longer diffusion distances in larger bodies. Similarly, the large drop in O2 levels at the end of the Permian is correlated with not only the loss of giant dragonflies, but also the largest mass extinction in history (Graham et al., 1995). It is important to acknowledge other factors beside low O2 (e.g. temperature, CO2) as potential causes for mass extinctions too (Knoll et al., 2007). However the O2-based theory has taken center stage after Peter Ward published his book Out of Thin Air (Ward, 2006). Ward has taken the most systematic approach to this problem to date and actually codified multiple hypotheses for major evolutionary events in response to changes in atmospheric O2 levels over the past 600 MY (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hypotheses for major evolutionary events in response to changes in atmospheric O2 levels over the past 600 MY from the book Out of Thin Air (Ward, 2006). These hypotheses are selected as those with potential for being tested by modern experimental methods discussed in this paper. The numbering scheme is that used in Ward's book and text in brackets is mine.

| Cambrian explosion | 3.1. The repeated-segmented body plan came about to allow large gill surface area … |

| 3.2. Initial shell formation … came about initially as a method of increasing respiratory efficiency. | |

| Silurian-Devonian O2 spike | 5.1. The conquest of land by vertebrate groups was enabled by a rise in atmospheric oxygen levels… |

| 5.2. The colonization of land by animals … took place in two distinct waves [split by Devonian mass extinction 410 – 370 MYA when O2 decreased]. | |

| Carboniferous-early Permian high O2 | 6.1. … High oxygen may have allowed amniotic eggs and then live births. |

| Permian O2 decrease and extinction | 7.1. Nasal turbinates evolved … as an adaptation for respiratory water retention in a low-oxygen world. |

| 7.2. The primary reason for this adaptation [endothermy] was not to maintain constant temperature but to increase efficiency in a low-oxygen enrionvment. | |

| 7.3. During times of low oxygen, altitude creates barriers to migration and gene flow… | |

| Triassic explosion and mass extinction | 8.1. The initial dinosaur body plan of bipedalism evolved as a response to low oxygen in the middle Triassic. |

| 8.2. Low O2 and high temperature increased tetrapod re-evolution to marine life. | |

| 8.3. Dinosaur diversity was strongly dependent on atmospheric oxygen levels… | |

| Jurassic low-oxygen world | 9.1. … late Triassic to earliest Jurassic was a time of low-oxygen levels and this coupled with very high carbon dioxide levels and hydrogen sulfide poisoning—not asteroid impact—was the major cause of the Triassic-Jurassic mass extinction. |

| 9.2. Ornithischian dinosaurs did not posses as effective a respiratory system as did saurischians. However, they were competitively superior … with regard to food acquisition. With the rise of oxygen to near present-day levels in the Cretaceous, ornitischians became the principal herbivores because of this superiority. | |

| 9.3. The low-oxygen and high-heat conditions of the late Permian into the Triassic stimulated the evolution of live birth and of soft eggs … the higher-oxygen levels (and continued high temperatures) of the late Jurassic-Cretaceous interval stimulated the evolution of rigid dinosaur eggs and egg burial in complex nests. | |

| 9.4. Jurassic-Cretaceous ammonite body plans evolved near the Triassic-Jurassic boundary in response to worldwide low oxygen. | |

| 9.5. The crab's body plan evolved for multiple reasons but one was that it increased respiratory efficiency by putting the gills in an enclosed space … and then evolving a pump to move water over the now enclosed gills. |

The hypotheses in Table 1 are intuitive and most of them are physiologically reasonable. However, many of them are teleological and based on correlations that do not necessarily demonstrate cause and effect. The best hypotheses are generally acknowledged as those that can be experimentally tested, i.e. disproven (Platt, 1964), which is difficult, of course, with most evolutionary topics. However, modern experimental biology includes several approaches for testing these hypotheses, as well as the potential for some new methods, as reviewed next.

4. Experimental approaches to hypotheses of evolutionary adaptation to O2 changes

4.1 Phylogenetically Independent Contrasts

Comparative physiologists have long been interested in questions of evolutionary adaptation to the environment. The main limitation of a comparative physiological approach is that experimental data is only available for animals that are living today. Hence, this approach requires assumptions about the physiology of ancestral animals to test the evolutionary hypotheses in Table 1. Over the past few decades, comparative physiology has developed improved approaches based on phylogenetic relationships to study evolutionary adaptations to the environment. One approach is called phylogenetically independent contrasts (PIC), which has promise for even further development to address some hypotheses about evolutionary adaptations to the environment.

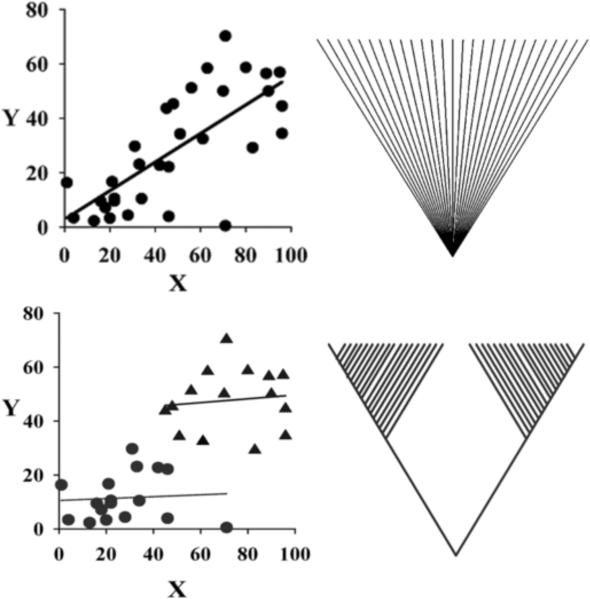

The importance of PIC for comparative physiology was summarized nicely in a paper titled “Why Not to Do Two-Species Comparative Studies: Limits on inferring Adaptation” (Garland and Adolph, 1994). It is easy to appreciate, for example, that the urine-concentrating ability of two species from a dry versus wet habitat can depend on much more than adaptations in the ability to concentrate urine. An animals' ancestry and genetic background could limit renal adaptations. One approach to this problem is to study more species but it remains virtually impossible to statistically remove all of the other influences. Fig. 2 shows the assumed phylogenetic relationship between multiple species if traditional linear regression is used to test for a significant relationship between a physiological variable and the environment. However, Fig. 2 also shows an alternative interpretation of the same data if it came from a phylogeny with two major branches. Most of the significance assigned to the environment by the traditional linear analysis would erroneously include the phylogenetic difference. PIC deals with this by explicitly incorporating a phylogeny for the species being studied and testing for differences in traits between sister species, or a species and the nearest node on a phylogenetic tree. These differences are “independent contrasts” with respect to inheritance and they can be weighted according to branch lengths between the contrasts on the phylogenetic tree to produce standardized independent contrasts, which in turn can be used in parametric statistical tests (Felsenstein, 1985).

Figure 2.

Hypothetical data showing phylogenetic effects in an adaptation (ordinate) to the environment (abcissa) in different species. Top panels show a significant correlation by conventional statistical methods where all species are assumed to have a common ancestor and evolutionary adaptations are independent events. Bottom panels show the same data assuming the species are from two clades (circles and triangles); the correlation is not significant for species within a clade (modified from Aguilar, 2000).

Reviewing an example of PIC analysis demonstrates both strengths and limitations. Aguilar (2000) studied the comparative physiology and biochemistry of air-breathing fishes with a PIC analysis. She studied nine species of fish in the family Gobiidae, which has a broad range of air-breathing abilities, from the nearly obligate air-breathing mudskippers (Periopthalmodon) to facultative air-breathing long-jaw mudsuckers (Gillichthys). Black-eyed gobies (Coryphopterus) were included as a strictly aquatic species. Air-breathing gobies hold air over their gills but do not have a modified swimbladder or other specialized structure for air-breathing. Standard algorithms were used to construct a phylogeny based on 55 morphometric characteristics and the branch lengths were standardized based on measures of environmental hypoxia (i.e. levels of daily hypoxia, air-breathing and relative activity). While traditional linear regression revealed 20 significant correlations between environmental hypoxia and biochemical traits, only 4 were significant with PIC. All of the significant PIC results were consistent with known biochemistry (Hochachka and Somero, 2002), e.g. increased anaerobic capacity (brain lactate dehydrogenase) correlated with daily hypoxia and decreased anaerobic capacity (decreased white muscle phosphofructokinase) was correlated with air-breathing. One of the four significant PIC results was not found with traditional regression but it was also consistent with known biochemistry, i.e. decreased lactate dehydrogenase/citrate synthase ratio was negatively correlated with air breathing.

The observation that so many significant correlations with traditional regression were (a) not observed with PIC but, (b) were consistent with known biochemistry suggests that the PIC might be too rigorous, or at least it might overlook significant information in the data sets.

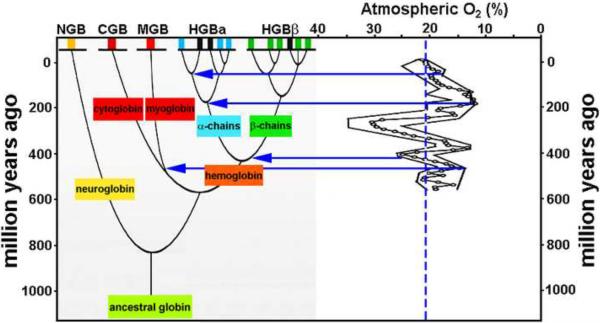

One type of information that is not included in PIC but in theory could be considered is information about the environment at the time of the branch points on the phylogenetic tree. The current method depends entirely on the environmental variable for the extant species being studied and ignores the history of the environment, which is the major point of the hypotheses we aim to test, namely that changing atmospheric O2 levels over the past 600 MY caused significant evolutionary changes in animals (Ward, 2006). Fig. 3 illustrates the relationship between changes in atmospheric O2 and the evolution of globins. Many of the major evolutionary splits for globins appear near local maxima or minima in the O2 history. Incorporating such information into a phylogenetically based comparative analysis could increase the statistical power relative to conventional PIC and be a useful tool for testing more hypotheses about evolutionary adaptations to changing environments.

Figure 3.

Mapping environmental changes onto phylogenetic trees. Changes in O2 of the earth's atmosphere throughout geological history (right) registered with a phylogenetic history for globins (left, modified from Pesce et al., 2002). Note the evolutionary splits occurring at times of high or low levels of atmospheric O2 (blue arrows) relative to present level (dashed blue line).

4.2 Experimental physiology and modeling

Classical comparative physiology also has an important role in testing the hypotheses for evolutionary changes in response to changes in O2 by quantifying the effects of O2 on physiological performance. Although this approach is limited by the physiology of extant animals, Owerkowicz and colleagues (2009) reasoned they could learn something from current species if they studied one of the few vertebrate taxa that survived the global changes in O2 over geologic history with a distinctly conservative morphology, namely Crocodilians. They incubated American alligator eggs and raised hatchlings under chronic hypoxia, normoxia or hyperoxia (12, 21 and 30% O2 respectively). Hypoxic hatchlings were significantly smaller and post-hatching growth was slowest under hypoxia but fastest under hyperoxia. Hypoxia, but not hyperoxia, enlarged the heart and accelerated growth of lungs. Hyperoxic alligators exhibited the lowest breathing rate and highest oxygen consumption per breath. They interpreted their data to indicate that, despite compensatory cardiopulmonary remodeling, hypoxia constrained growth and limited the capacity to utilize food. Conversely, the combination of elevated metabolism and low cost of breathing in hyperoxic alligators allowed for a greater proportion of metabolic energy to be used for growth. Hence, growth and metabolic patterns could have been affected significantly by changes in the atmospheric O2 level, thereby affecting survival of a species.

Relating physiological performance to natural selection and survival is challenging, however. For example, it is intuitively obvious that increased diffusing capacity in a respiratory organ can allow increased O2 uptake. Yet the diffusing capacity has to decrease to less than 50% of the normal value before resting O2 exchange is impaired in humans under current normoxic levels (Powell, 2003). Hence, one would expect animals could survive large decreases in atmospheric O2 driving diffusion in the lungs at rest. In contrast, if O2 consumption increases when atmospheric O2 is low, then even small decreases in lung diffusing capacity can be limiting. It is frequently argued that maximal O2 demand (V̇O2max) provides a better respiratory variable to consider for evolutionary questions because survival could depend, for example, on the ability to run away from a predator. However, it has not been possible to prove this in studies looking at reproductive success and exercise capacity (Hayes and O'Connor, 1999). Similarly, the principle of “symmorphosis” is not fully met in mammalian lungs, i.e. animals appear to have evolved excessive lung structure (O2 diffusing capacity) for their maximal physiological needs (V̇O2max) (Taylor et al., 1987).

Considering relationships between maximal performance and putative evolutionary adaptations to changes in O2 leads to questions about potential increases in fitness of respiratory adaptations when other systems limit the overall respiratory performance of an organism. If respiratory adaptations lead the evolution of increased metabolism and activity in animals, then presumably they first enhanced fitness in animals that still had relatively low performance. For example, one of the most ancient strategies to cope with decreases in O2 is the ability to decrease metabolism, i.e. O2 demand (Hochachka and Somero, 2002). How could respiratory adaptations to changing atmospheric O2 contribute to increased fitness in such “low performance” animals and ultimately lead to the evolution of “high performance” animals? Farmer and Sanders (2010) recent work on alligator lungs provides some interesting insights. These investigators obtained experimental evidence for unidirectional airflow in alligator lungs and propose it was a general feature of archosaurian lungs, not just avian lungs. A selective advantage for this adaptation in extant or early reptiles with low metabolic rates could be cardiogenic mixing of air in the lungs. This could set the evolutionary stage for increased metabolic performance that takes advantage of cross-current gas exchange in birds capable of very high levels of O2 consumption (see below).

Although comparative physiology may not prove environmental adaptation, quantifying physiological performance can determine if an animal is sensitive to a given environmental change or not, and thereby potentially disprove a hypothesis for environmental adaptation. For example, Hypothesis 3.2 implies that O2 uptake should be more efficient in a mollusk with, compared to one without, a shell. This could be tested experimentally by measuring O2 uptake in (a) ventilating mollusks with shells versus (b) mollusks with their gills exposed to still water under the same conditions. Modeling, which has proved very productive in the comparative physiology of gas exchange (Scheid, 1987) could be used to address this question also.

Another example where modeling and experimental measurements have been extremely informative is in comparative studies on the efficacy of gas exchange in the avian parabronchial lung-air sac respiratory system, which is usually compared with mammalian alveolar lungs. Piiper and Scheid (1972; 1975) developed quantitative models for different models of gas exchange predicting a theoretical advantage of cross-current exchange in avian lungs over alveolar gas exchange in mammals. However, models also show that the theoretical advantage is not always achieved in nature because of limitations from diffusion and matching of ventilation and perfusion (Powell and Scheid, 1989). Model predictions for exercise in hypoxia, such as during flight at high altitude flight, predicts an advantage in O2 uptake for birds over mammals although its magnitude is controversial (Hopkins and Powell, 2009; Scott and Milsom, 2006). To date, it has not been possible to experimentally test model predictions in birds exercising as hard as they would be during flight. However, technology will eventually make this possible and permit a stronger evaluation of Hypothesis 8.4 (Table 1). One predicts that significantly better pulmonary O2 exchange during hypoxic exercise in birds compared to mammals if an air sac-respiratory system explains saurischian dinosaurs having lower extinction rate when O2 levels fell during the late Triassic.

4.3 Analyzing rates of environmental and evolutionary change

Another potential approach for understanding mechanisms of evolutionary adaptation to global environmental change is modeling the interactions between the rates of different biological responses and those of environmental changes. The first rate to consider for this is the rate of change in genetic information with evolution. Hemoglobin is an ideal model for addressing this because so much is known about it in terms of genetics and molecular structure-function. Further, hemoglobin O2-affinity is the most common presumed adaptation to hypoxia in high altitude animals (Powell and Hopkins, 2010). A full comparative study using PIC has not been done with hemoglobin, but in closely related birds, rodents, carnivores and humans native to low and high altitude, O2- hemoglobin affinity is higher (P50 is lower) in the high altitude species. Higher O2-hemoglobin affinity will enhance O2 uptake in the lungs under hypoxic conditions. Amazingly, only one amino acid substitution in α-hemoglobin is necessary to explain the higher O2-hemoglobin affinity in high altitude bar-headed geese compared to low altitude greylag geese (Jesssen et al., 1991). Similar results occur in mammals and these substitutions generally involve contact points between subunits that stabilize hemoglobin in either the low-affinity (tense) or high-affinity (relaxed) conformations (Weber, 2007). It remains to be determined if hemoglobin adaptations appear to be the most common high-altitude adaptation in vertebrates because they involve relatively few mutations or because hemoglobin is so central to O2 transport in animals.

Relatively few amino acid substitutions are required for this presumed adaptation but how long does it take for a genetic mutation to change an amino acid? Fortunately this data is available for β-globin and it is about 1 amino acid per 5 MY (Fitch and Langley, 1976). How does this rate compare to the rates of environmental change we are considering? The bar-headed goose is thought to fly over the highest peaks in the Himalaya because they have been using that migratory path since before the mountains were as tall as today (Swan, 1970). Recent geological research indicates that the Himalayan mountains grew to their present height over the last 50 MY (Royden et al., 2008). If we consider the drop in PO2 between sea level and the top of Mount Everest (which the bar-headed geese fly over) then this species was exposed to an average decrease in the minimum inspired PO2 of 2 Torr/MY. Hence, over the time necessary for one amino acid substitution, the minimum inspired PO2 would have dropped 10 Torr. While the physiological effects of decreasing PO2 are not linear (cf. the sigmoidal O2-hemoglobin dissociation curve), a 10 Torr decrease in PO2 is physiologically significant, especially near the minima experienced flying over Mount Everest today (reviewed by Butler, 2010). Therefore, the amount of genetic change and the time necessary for such change are consistent with increased O2-hemoglobin affinity being an evolutionary adaptation to changes in environmental O2.

Another model for studying evolutionary adaptation to decreased O2 is the human populations living at high altitude, for example in the Andean altiplano or the Tibetan plateau and Himalayan region of Asia. The rate of change in O2 for these populations would be orders of magnitude greater than those for bar-headed geese migrating over the Himalaya. If these humans migrated from sea level then the inspired PO2 would have decreased between 2,000 and 5,000 Torr/MY. Given that these populations have been at high altitudes for 11,000 years in the Andes to 22,000 years Tibet (Beall, 2007), it cannot be expected that even this high rate of change would drive genetic mutations fast enough for adaptive amino acid substitutions. However, 11,000 years, which is equivalent to the 550 generations estimated for the Andeans having been at high altitude, is certainly enough time for a change in allele frequencies to stabilize in a population. In a system with two alleles having a 10% difference in fitness and 5% of the population having the fitter allele, the fitter allele will increase to 95% of the population after 550 generations (Rupert and Hochachka, 2001). Therefore, the data on human adaptations to O2 decreases upon migration to high altitude are compatible with natural selection on a genetic background that includes traits favorable for hypoxia.

Beall (2007) has reviewed how a complete case for natural selection to high altitude would include identification of genetic variation causing biological variation in the populations and variation in performance among the genotypes and their associated phenotypes. Brutsaert and colleagues (2005) showed that the blunted hypoxic ventilatory response observed in high altitude native Andeans has a genetic basis. They used an “admixiture model” to quantify the amount of Native American ancestry (from 0 to 100%) in individuals studied. Higher Native American ancestry was significantly related to a lower hypoxic ventilatory response at high altitude, demonstrating correlated genetic and biological variation. These results were used to infer both a genetic mechanism and an evolutionary origin for the blunted phenotype.

Quantitative genetic models show significant heritability (h2, the proportion of variance in a quantitative trait that is attributable to genetic relationships) for several O2 transport traits, including the percent arterial O2 saturation of hemoblogin (SO2) in Tibetan high altitude natives (Beall, 2007). Segregation analysis has been used to test the hypothesis that the high SO2 trait was determined by a “major gene”, which is an inferred allele with a large quantitative effect instead of multiple genes with small quantitative effects. A major gene effect was detected for a 6 to 10% greater SO2 in three different regions of Tibet. Women in these regions with the trait had over twice as many living children as women with lower SO2. The actual value for Darwinian fitness (w) was 50% stronger than that for hemoglobin S, which is the classic example of human evolutionary adaptation in which heterozygotes with hemoglobin S have sickle cells that provide protection against malaria. The fitness for the SO2 “major gene” is so great that if it represents past levels of fitness, it must have derived from a mutation within the past 1,000 years (Beall, 2007). However, this does not necessarily mean that the rapid rate of O2 decrease during human migrations can drive genetic mutations faster than slower rates of O2 change.

Moore (2001) has argued that a longer time at high altitude results in more complete adaptation. This idea is based primarily on the lower prevalence of chronic mountain sickness (CMS) and less intrauterine growth restriction (i.e. low birth weight) in Tibetans compared to Andean, Europeans and Han (Chinese) who have lived at high altitude for shorter times. However, heritability is not observed for as many O2 transport traits in Andeans as in Tibetans (Beall, 2007). Hence, the most conservative conclusion is that the differences between ancestral genetics of the high altitude Tibetan and Andean populations explain their physiological differences.

Another example of changing O2 that might affect evolution is the elevation of the Andean altiplano, if animals living there did not migrate away as it increased in altitude. Recent work indicates the Andean altiplano rose about 2500m over the past 5 MY, which yields a rate of change for PO2 of 12 Torr /MY (Ghosh et al., 2006). This is only one order of magnitude greater than the rate for PO2 change in the bar-headed goose flying over the Himalaya and might explain some of the changes in hemoglobin O2 affinity in the animals living on the Andean altiplano. Comparative studies using designs similar to those described for Tibetan human populations above could be used to address this question quantitatively.

It is important to note that the geographical effects on PO2 were not constant throughout evolutionary history and it is hypothesized that changes in geography and altitude interacted with changes in atmospheric O2 to affect evolution. Huey and Ward (2005) pointed out how the PO2 at sea level in the Triassic was equivalent to about 3,000m above sea level in today's atmosphere. Looking at the current altitude records for different classes of vertebrates, it is estimated that if their physiology was the same today as in the Triassic, they would have been limited to habitats less than 2,000m above sea level. Even more dramatic, animals that could survive at 6,000m altitude in the mid-Permian would only be able to tolerate 500m altitude in the Triassic. This represents not only a loss of habitat but would fragment populations. Compounding the difficulty in estimating the exact effects of these changes is continental drift, which shuffled the geography while local PO2 was changing with altitude from mountain building and O2 changes in the atmosphere.

So how do these rates of change in PO2 for animals and people exposed to different environments compare to the change in atmospheric PO2 over geological time? At sea level, the decrease in PO2 from its peak in the Permian to the nadir in the Triassic was −4 Torr/MY. The relatively steady increase in PO2 since the Jurassic has been +0.4 Torr/MY. Hence, the rates of atmospheric change in O2 are at the low end of changes that are associated with evidence for adaptation to hypoxia in biological systems, which is consistent with time for both the occurrence of favorable genetic mutations and time for natural selection to stabilize them in populations. Hence, the predicted rates of PO2 are not too fast to disprove the hypothesis that changes in atmospheric O2 drove evolutionary adaptations.

A fruitful area for future research utilizing the rates of change of PO2 could apply systems analysis and systems biology to explore interactions between the frequency response of biological processes and rates of environmental change. Biological responses operate over many different time domains, ranging from seconds to generations and even eons. While physiology determines the direct biological consequences of any physical environmental change, this relationship is modulated by an organism's ability to modify its environment (behavior), plasticity in acute physiological responses (acclimatization), genetic changes through evolution (adaptation) and secondary changes in the environment that affect all of the above (ecology). These interactions lead to feedback loops that will have their own frequency-response characteristics, in addition to those of the primary responses.

Additionally, these biological feedback loops may affect the environmental variable, such as photosynthesis explaining the first great rise in atmospheric O2. The possibility for resonance and damping certainly exists with these inherently different frequencies interacting so there may be particular rates of O2 change that have greater or lesser biological consequences. In theory, these ideas are testable because the rates of behavioral, physiological, evolutionary and ecological responses to O2 change can all be estimated or measured, and used to build models for testing hypotheses of adaptations to environmental O2 change.

4.4 Experimental evolution

Fruit flies (Drosphila meloganster) have been a popular model for experimental studies of molecular genetics and evolution for essentially a century. In 1933, Thomas Hunt Morgan won the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for his work with the species and today biomedical laboratories are using the model to discover genetic mechanisms for hypoxia tolerance (Azad and Haddad, 2009). Klok and colleagues (2009) specifically addressed the evolutionary question that high O2 levels, such as those in the Permian, increased body size in insects. They reared three replicate lines of fruit flies for seven generations in hypoxia, normoxia or hyperoxia, each followed by four generations in normoxia. In hypoxia, average body size fell in one generation and returned to normoxic control levels after one to two generations of normoxia, indicating responses were due primarily to developmental plasticity. In hyperoxia, body size increased and the largest mass was reached during the first generation of return from hyperoxia to normoxia. These results suggest that higher O2 levels during the Permian might have caused insects to evolve larger average sizes, rather than simply permitting evolution of gigantism, although increased fitness remains to be demonstrated for flies with larger body size.

Experimental evolution has also been used to test general questions of evolutionary adaptation to the environment in bacteria. Bennet and Lenski (2007) studied the fitness of 24 lineages of E. coli exposed to 20°C for 2,000 generations and their relative decrement in fitness at 40°C. Only 15 of the 24 cold-evolved lines had decreased fitness at high temperature indicating that a “tradeoff” in fitness in other environments is common but not necessary for beneficial adaptation to cold. The inverse experiment could be conducted to determine if there is any directionality to this conclusion. However, the applicability of these results from prokaryotes to vertebrate evolution is not clear at this time.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Comparative physiology and experimental evolution clearly show that changes in atmospheric O2 over the ages had the potential to drive evolution, assuming the physiological O2-sensitivity of animals today is similar to the past. Oxygen is one of the most important physical variables affecting an animal's biology, although temperature and pH are also important and there are several arguments for global change in these variables having impacted animal evolution (Portner et al., 2005; Knoll et al., 2007). Temperature and CO2 (which determines pH) are currently of intense interest for evaluating the potential impact of global warming from green house gases. Proven methods such as phylogenetically independent contrasts, as well new approaches such as adding environmental history to phylogenetic trees, can be used to test (i.e. disprove) hypotheses about biological adaptations to changes in atmospheric O2. Of course, improved fitness and reproductive success needs to be demonstrated for putative evolutionary adaptations also, which argues for more interdisciplinary studies and collaboration across different fields focused on both living and extinct animals. Adaptation to oxygen provides a useful model for studying biological responses to global environmental change in general, as well as for understanding the general biology of oxygen.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr. Steven Perry for organizing the International Congress of Respiratory Sciences that stimulated this work and all of the researchers and students at White Mountain Research Station who made me think beyond physiology. The work was supported by NIH 1R01HL081823 and the University of California White Mountain Research Station.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aguilar N. Ph.D. Thesis. University of California; San Diego: 2000. Comparative physiology of air-breathing Gobies. [Google Scholar]

- Azad P, Haddad GG. Survival in acute and severe low O2 environment: use of a genetic model system. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009;1177:39–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall CM. Detecting natural selection in high-altitude human populations. Respir. Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;158:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett AF, Lenski RE. An experimental test of evolutionary trade-offs during temperature adaptation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2007;104(Suppl 1):8649–8654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702117104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berner RA. The Phanerozoic Carbon Cycle: CO2 and O2. Oxford Press; Oxford: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Berner RA, vandenBrooks JM, Ward PD. Evolution - Oxygen and evolution. Science. 2007;316:557–558. doi: 10.1126/science.1140273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutsaert TD, Parra EJ, Shriver MD, Gamboa A, Rivera-Ch M, Leon-Velarde F. Ancestry explains the blunted ventilatory response to sustained hypoxia and lower exercise ventilation of Quechua altitude natives. Am. J Physiol Regul. Integr. Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R225–R234. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00105.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler PJ. High fliers: The physiology of bar-headed geese. Comp Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2010 Jan 28; doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.01.016. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer CG, Sanders K. Unidirectional airflow in the lungs of alligators. Science. 2010;327:338–340. doi: 10.1126/science.1180219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar J, Bao HM, Thiemens M. Atmospheric influence of Earth's earliest sulfur cycle. Science. 2000;289:756–758. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am. Naturalist. 1985;125:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch WM, Langley CH. Protein evolution and molecular clock. Fed. Proc. 1976;35:2092–2097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Jr., Adolph SC. Why not to do two species comparisons - limitations on inferring adaptation. Physiol. Zool. 1994;67:797–828. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Garzione CN, Eiler JM. Rapid uplift of the Altiplano revealed through C-13-O-18 bonds in paleosol carbonates. Science. 2006;311:511–515. doi: 10.1126/science.1119365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JB, Dudley R, Aguilar NM, Gans C. Implications of the late Palaeozoic oxygen pulse for physiology and evolution. Nature. 1995;375:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JP, O'Connor CS. Natural selection on thermogenic capacity of high-altitude deer mice. Evolution. 1999;53:1280–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb04540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka PW, Somero GN. Biochemical Adaptation: Mechanism and process in physiological evolution. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Huey RB, Ward PD. Hypoxia, global warming, and terrestrial Late Permian extinctions. Science. 2005;308:398–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1108019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen TH, Weber RE, Fermi G, Tame J, Braunitzer G. Adaptation of bird hemoglobins to high altitudes: demonstration of molecular mechanisms by protein engineering. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1991;88:6519–6522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klok CJ, Harrison JF. Atmospheric hypoxia limits selection for large body size in insects. PLoS. One. 2009;4:e3876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll AH, Barnbach RK, Payne JL, Pruss S, Fischer WW. Paleophysiology and end-Permian mass extinction. Earth Plan. Sci. Let. 2007;256:295–313. [Google Scholar]

- McAlester L. Animal extinctions, oxygen consumption, and atmospheric history. J Paleontol. 1970;44:405–409. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain JC, Chaloner WG. The fossil cuticle as a skeletal record of environmental change. Palaios. 1996;11:376–388. [Google Scholar]

- Moore LG. Human genetic adaptation to high altitude. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2001;2:257–279. doi: 10.1089/152702901750265341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owerkowicz T, Elsey RM, Hicks JW. Atmospheric oxygen level affects growth trajectory, cardiopulmonary allometry and metabolic rate in the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) J. Exp. Biol. 2009;212:1237–1247. doi: 10.1242/jeb.023945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesce A, Bolognesi M, Bocedi A, Ascenzi P, Dewilde S, Moens L, Hankeln T, Burmester T. Neuroglobin and cytoglobin: Fresh blood for the vertebrate globin family. EMBO reports. 2002;3:1146–1151. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piiper J, Scheid P. Maximum gas transfer efficacy of models for fish gills, avian lungs and mammalian lungs. Respir. Physiol. 1972;14:115–124. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(72)90022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piiper J, Scheid P. Gas transport efficacy of gills, lungs and skin: theory and experimental data. Respir. Physiol. 1975;23:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(75)90061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt JR. Strong Inference. Science. 1964;146:347–353. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3642.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portner HO, Langenbuch M, Michaelidis B. Synergistic effects of temperature extremes, hypoxia, and increases in CO2 on marine animals: From Earth history to global change. J. Geophys. Res. 2005;110:C09S10. [Google Scholar]

- Powell FL, Hopkins SR. Vertebrate life at high altitude. In: Nilsson G, editor. Respiratory Physiology of Vertebrates: Life with and without Oxygen. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2010. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Powell FL, Scheid P. Physiology of gas exchange in the avian respiratory system. In: King AS, McLelland J, editors. Form and Function in Birds. Vol. 4. Academic Press Ltd.; London: 1989. pp. 393–437. [Google Scholar]

- Powell FL. Pulmonary Gas Exchange. In: Johnson LR, editor. Essential Medical Physiology. Lippincott-Raven; New York: 2003. pp. 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Royden LH, Burcfiel BC, van der Hilst RD. The geological evolution of the Tibetan Plateau. Science. 2008;321:1054–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.1155371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupert JL, Hochachka PW. The evidence for hereditary factors contributing to high altitude adaptation in Andean natives: A review. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2001;2:235–256. doi: 10.1089/152702901750265332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid P. The use of models in physiological studies. In: Feder ME, Bennett AF, Burggren WW, Huey RB, editors. New Directions in Ecological Physiology. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1987. pp. 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Scott GR, Milsom WK. Flying high: a theoretical analysis of the factors limiting exercise performance in birds at altitude. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2006;154:284–301. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan LW. Goose of the Himalayas. Nat. Hist. 1970;79:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CR, Weibel ER, Karas RH, Hoppeler H. Adaptive variation in the mammalian respiratory system in relation to energetic demand: VIII. Structural and functional design principles determining the limits to oxidative metabolism. Respir. Physiol. 1987;69:117–127. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(87)90097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward PD. Out of Thin Air. John Henry Press; Washington DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Weber RE. High-altitude adaptations in vertebrate hemoglobins. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2007;158:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]