Abstract

Children differ in how quickly they reach linguistic milestones. Boys typically produce their first multi-word sentences later than girls do. We ask here whether there are sex differences in children's gestures that precede, and presage, these sex differences in speech. To explore this question, we observed 22 girls and 18 boys every 4 months as they progressed from one-word speech to multi-word speech. We found that boys not only produced speech + speech (S+S) combinations (`drink juice') 3 months later than girls, but they also produced gesture + speech (G+S) combinations expressing the same types of semantic relations (`eat' + point at cookie) 3 months later than girls. Because G+S combinations are produced earlier than S+S combinations, children's gestures provide the first sign that boys are likely to lag behind girls in the onset of sentence constructions.

Introduction

Children vary widely in how quickly they achieve linguistic milestones. Sex has been shown to be one of the most important contributors to this variability. From an early age, children exhibit sex differences in their verbal abilities, with girls exceeding boys in most aspects of verbal performance (Hyde & Linn, 1988; Kimura, 1998). Girls not only produce their first words (Maccoby, 1966) and first sentences (Ramer, 1976) at a younger age than boys, but they also have larger vocabularies (Huttenlocher, Haight, Bryk, Seltzer & Lyons, 1991) and use a greater variety of sentence types (Ramer, 1976) in their early communications than boys of the same age. Thus, even though there is a normal age range within which language milestones are typically achieved, girls tend to be on the earlier end, and boys on the later end, of this age range. The question we ask here is whether we see evidence of sex differences in the onset of communicative skills in children's gestures before they become apparent in speech.

Although there are now numerous reports of sex differences in children's verbal abilities, very little is known about sex differences in children's early use of gesture and its relation to language learning. We know from previous work that children typically gesture before they produce their first words (Bates, 1976; Bates, Benigni, Bretherton, Camaioni & Volterra, 1979) and that girls, on average, tend to produce their first pointing gestures earlier than boys (Butterworth & Morisette, 1996). But does gesturing merely precede talking (in the same way that crawling precedes walking), or is it itself relevant to the language learning process? If gesturing not only precedes language, but also reflects knowledge relevant to the developmental process responsible for language, then boys, who produce their first sentences later than girls (Ramer, 1976), should also attain the gestural precursor to that linguistic milestone later than girls. We tested this prediction by examining gesture and speech in boys and girls during the transition from one-word to multi-proposition utterances.

Gesture reflects knowledge relevant to language learning

Children communicate using gestures before they produce their first words (Acredolo & Goodwyn, 1985, 1989; Bates, 1976; Bates et al., 1979). They use deictic gestures to convey object information (e.g. point at cookie to indicate a COOKIE) and iconic or conventional gestures to convey action information (e.g. move hand repeatedly to mouth to convey EATING; extend an open palm next to a desired object to indicate GIVE).1 Young children often point at objects for which they do not yet have words. Interestingly, the fact that a child has pointed at an object increases the likelihood that the child will learn a word for that object within the next few months, suggesting that early gesture is relevant to later word learning (Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, 2005).

Child gesture may also be relevant to later sentence learning. Before producing their first two-word utterances, children produce gesture+speech combinations. In some of these gesture+speech combinations, gesture conveys one meaning and speech another (i.e. supplementary combinations such as saying the word `eat' while pointing at a cookie). Combinations of this sort express sentence-like meanings. Importantly, the age at which children first express two ideas in a gesture+speech combination precedes the age at which they produce their first two-word sentence (`eat cookie', `drink milk'; Goldin-Meadow & Butcher, 2003; Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, 2005). Thus, young children demonstrate the knowledge necessary for two-word speech initially in communications that combine gesture and speech.

Even more striking, children use gesture and speech together to convey particular semantic relations before they convey each of these types of relations entirely in speech (Özçalişkan & Goldin-Meadow, 2005a). For example, in his quest for a cookie, a child points at the cookie while uttering the word `mommy', thus conveying two arguments of a transfer relation – the patient (cookie) in gesture and the actor (mommy) in speech. Several months later, the same child will be able to produce similar sentential constructions in speech (e.g. `mommy cookie', `daddy cup').2 Similarly, to describe the fact that he is eating a cookie, a child produces the iconic gesture EAT while saying the word `cookie', thus conveying the predicate (eat) in gesture and its patient (cookie) in speech several months before expressing predicate+argument relations entirely in speech (`eat cookie', `ride bike'). Young children even use gesture and speech together to express two propositions within the bounds of a single communicative act (akin to a complex sentence). For example, the child produces the iconic gesture EAT while saying `I like it', thus conveying one predicate in speech (like) and one in gesture (eat) several months before expressing two predicates entirely in speech (e.g. `I like eating it', `let me find it'). Thus the pattern of development for the onset of each sentence type – from multi-modality gesture+speech combinations to single modality speech+speech combinations – suggests that gesturing may not only precede language, but may also reflect knowledge relevant to the process of learning language.

Do sex differences in language learning appear first in gesture?

Previous research with children who are delayed in the onset of productive vocabulary has shown that gesture use is a good predictor of later language development (Thal & Tobias, 1992). Specifically, late talkers who performed poorly on gesture tasks and who made little use of gesture continued to exhibit delays in producing words one year later, whereas those who performed relatively well on these gesture tasks and who made extensive use of gestures had vocabularies at the appropriate age level one year later (see also Sauer, Levine & Goldin-Meadow, 2009). Thus, late bloomers and truly delayed children can be reliably distinguished from one another on the basis of their early communicative gestures. The closely timed progression of gesture and speech has been shown not only for children whose early words are delayed, but also for children whose first sentences are delayed. Children with early unilateral brain injury who exhibit significant delays in their early multi-word speech also exhibit significant delays in their gesture+speech combinations conveying similar meanings (Özçalişkan, Levine & Goldin-Meadow, 2009).

But boys are not delayed with respect to language development. As a group, they lag behind same-aged girls, but are still within the normal range of variation. Do gesture+speech combinations reliably predict the onset of multi-word speech in later talkers (typically boys) as well as early talkers (typically girls)? If so, we should be able to see evidence of a difference between the sexes in gesture before we see it in speech. To explore this prediction, we extended and reanalyzed data on 18 boys and 22 girls, originally observed by Özçalişkan and Goldin-Meadow (2005a) from 14 to 22 months. By 22 months, only a subset of the children in the sample had begun producing all three of the linguistic constructions examined by Özçalişkan and Goldin-Meadow (2005a): argument+argument, predicate+argument, and predicate+predicate constructions. We therefore extended our observations on the 40 children until 34 months (the age at which most of the children were producing all of the constructions), and analyzed the data separately for boys and girls.3 We ask here whether boys begin producing each of the three constructions in gesture+speech combinations later than girls. Our prediction was that they would and that they would also begin producing each sentential construction in speech later than girls, thus suggesting that sex differences can indeed be detected in gesture prior to speech.

Methods

Sample and data collection

Forty American children (22 girls, 18 boys) were videotaped with their parents for 90 minutes in their homes every 4 months from 14 to 34 months of age by an experimenter. The parents were told to interact with their children as they normally would in their everyday routines and ignore the presence of the experimenter. The sessions typically involved free play with toys, book reading, and a meal or snack time, but also varied slightly according to the preferences of the caregivers. Children's families constituted a heterogeneous mix in terms of income and ethnicity; the families of boys and girls were comparable in their income and ethnic composition (see Table 1). The families were paid for their participation in the study.

Table 1.

The distribution of boys and girls by family ethnicity and income

| Family ethnicity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household income | African American | Caucasian | Othera | Totalb | |

| Low | Girls | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 (23%) |

| ($15,000–$34,999) | Boys | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 (28%) |

| Medium | Girls | 2 | 5 | 2 | 9 (41%) |

| $35,000–$74,999 | Boys | 2 | 4 | 0 | 6 (33%) |

| High | Girls | 1 | 6 | 1 | 8 (36%) |

| $75,000–$100,000 | Boys | 0 | 6 | 1 | 7 (39%) |

| Totalc | 8 (20%) | 24 (60%) | 8 (20%) | 40 | |

Other category included Asian and Hispanic families, along with a few families with mixed ethnicities.

The relative proportion of boys and girls within each income group was roughly equal: the majority of the girls (77%) and boys (72%) came from medium- to high-income families; only a relatively small percentage of the girls (23%) and boys (28%) came from families within the low-income bracket.

The relative proportion of boys and girls within each ethnicity was roughly equal: the majority of the girls (55%) and boys (66%) came from Caucasian families; only a relatively small percentage of the girls (23%) and boys (17%) came from African American families.

Coding and analysis

All meaningful sounds and gestures were transcribed. Communicative hand movements that did not involve direct manipulation of objects (e.g. twisting a jar open) or a ritualized game (e.g. patty cake) were considered gestures. Sounds that were reliably used to refer to entities, properties, or events (`doggie', `nice', `break'), along with onomatopoeic sounds (e.g. `meow', `toot-toot') and conventionalized evaluative sounds (e.g. `uh-oh'), were counted as words. The transcribed data were divided into communicative acts. A communicative act was defined as a string of words or gestures that was preceded and followed by a pause, a change in conversational turn, or a change in intonational pattern. Communicative acts were classified into three categories: (1) Gesture only acts were gestures produced without speech, either singly (e.g. point at cookie) or in combination (e.g. point at cookie+point at mother). (2) Speech only acts were words produced without gesture, either singly (e.g. `cookie') or in combination (`mommy cookie', `baby drink juice'). (3) Gesture+speech combinations were acts containing both gesture and speech (e.g. `mommy'+point at cookie, `nice doggie'+point at dog).

Gesture+speech combinations were further categorized into three types based on the relation between the information conveyed in gesture and speech. (1) A reinforcing relation was coded when gesture conveyed the same information as speech (e.g. `box'+point at box). (2) A disambiguating relation was coded when gesture clarified the referent of a proform in speech (e.g. `this'+point at box). (3) A supplementary relation was coded when gesture added semantic information to the message conveyed in speech (e.g. `open'+point at box).

We focus here only on supplementary gesture+speech (G+S) combinations because they express sentence-like meanings and, in this sense, are comparable to multi-word, speech+speech (S+S) combinations. Supplementary G+S combinations and multi-word S+S combinations were categorized into three sentence construction types according to the types of semantic elements conveyed, following the criteria developed in earlier work (Özçalişkan & Goldin-Meadow, 2005a): (1) multiple arguments without a predicate, (2) a predicate with at least one argument, and (3) multiple predicates with or without arguments (see examples in Table 2).

Table 2.

Examples of the types of semantic relations produced by boys and girls in multi-word S+S speech combinations and in supplementary G+S combinationsa

| Combination type | Multi-word speech + speech (S+S) combinations | Supplementary gesture + speech (G+S) combinationsb |

|---|---|---|

| Argument+Argument(s) | Boys | Boys |

| `Bottle dada' [18] | `Daddy' + TOY (point) [18] | |

| `Mama cuppie' [22] | `Teeth' + TOOTHPASTE (point) [22] | |

| `Dad church' [26] | `Poopoo mommy' + BATHROOM (point) [26] | |

| `I a booboo mom' [30] | `Emily cereal' + MOUTH (point) [30] | |

| `Mom gatorade in my cup' [34] | `Juice mama' + EMPTY CUP (hold) [34] | |

| Girls | Girls | |

| `Mommy the bell' [14] | `Mommy' + FOOD (point) [14] | |

| `Mommy phone' [18] | `Hat' + HEAD (point) [18] | |

| `Earring upstairs' [22] | `Garbage' + BEANS (point) [22]c | |

| `Mom keys in basket' [26] | `Mommy water' + EMPTY CUP (point) [26] | |

| `The cat in the tree' [30] | `Mommy in here' + DOLL (hold) [30] | |

| `Mom marker on the cup' [34] | `No down basement' + FATHER (point) [34] | |

| Predicate+Argument(s) | Boys | Boys |

| `Daddy gone' [18] | `Pegs' + GIVE (conventional) [18] | |

| `Turtle brush the teeth' [22] | `Shave' + RAZOR (point) [22] | |

| `Baby scratched me' [22] | `Have wheels' + TRUCK (point) [26] | |

| `Dad pushing the stroller' [26] | `Stayed in the hospital' + BLANKET (point) [30] | |

| `I putted it on top of the tower' [30] | `And daddy clean up all the bird poopie' + TABLE (point) [34] | |

| `My bike has snow on it' [34] | ||

| Girls | Girls | |

| `I read' [14] | `Read' + BOOK (hold) [14] d | |

| `Baby rocking' [18] | `Hair' + WASH (iconic) [18] | |

| See the cup' [22] | `Clean the house' + WIPE (hold) [22] | |

| `I drop my poopie mom' [26] | `Draw a body' + PAPER (point) [26] | |

| `I throw it on the floor' [30] | `It in the drawer' + CLOSE (iconic) [30] | |

| `You see my butterfly on the wall' [34] | `I wash her hair' + SINK (point) [34] | |

| Predicate+Predicate | Boys | Boys |

| `Let me put on frog' [26] | `I want to hold baby' + GIVE (conventional) [22] | |

| `Make it fall' [30] | `Go up' + CLIMB (iconic) [26] | |

| `We got to climb up there and fix it' [30] | `Me try it' + GIVE (conventional) [30] | |

| `We can pitch the tent up in there because it not going to work anymore' [34] | `Carry' + PUSH (iconic) [34]e | |

| Girls | Girls | |

| `Help me find' [22] | `I paint' + GIVE (conventional) [22] f | |

| `Let me find it' [26] | `I like it' + EAT (iconic) [22] | |

| `What are we going to do if it rain?' [30] | `Me scoop' + GIVE (conventional) [26] g | |

| You asked me to make a tower that I go in' [34] | `You making me' + FALL (iconic) [30] | |

| `I just like that' + STIR (iconic) [34] |

The age, in months, at which each example was produced, is given in brackets after each example.

The speech is in single quotes, the meaning gloss for the gestures is in small caps, and the type of gesture (point, iconic, conventional) is indicated in parentheses following the gesture gloss. We did not code the order in which gesture and speech were produced in G+S combinations; the word is arbitrarily listed first and the gesture second in each example.

The child is telling her mom that the beans are to be placed in the garbage can.

The child is holding up the book to bring it to the parent's attention; such gestures are also labeled as `show' gestures in the literature.

The child is showing his mother how one carries groceries in a store by moving his hands in the air as if pushing a cart.

The child is asking for a crayon so that she could paint.

The child is asking for the measuring cup so that she could scoop flour from the bowl.

We assessed reliability at several different levels. The first level involved identifying gestures (i.e. presence or absence of gesture) and assigning meaning glosses to each gesture. For this level of coding, two trained coders transcribed and coded a randomly chosen 90-minute observation session. Agreement between coders was 88% (k = .76; N = 763) for identifying gestures and 91% (k = .86; N = 375) for assigning meaning glosses to each gesture. For the second level of coding, two trained coders assigned semantic constructions to a randomly chosen segment of the data, accounting for 20% of the data used in the study. Agreement between coders was 99% (k = .98; N = 482) and 96% (k = .93; N = 179) for assigning sentence construction types to multi-word S+S combinations and to supplementary G+S combinations, respectively. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVAs with sex as a between-subjects factor or age as a within-subject factor, two-way ANOVAs with modality (G+S, S+S) as a within-subject and sex as a between-subjects factor, and chi squares, as appropriate.

Results

Children's early supplementary gesture+speech combinations and multi-word speech

We looked first at the number of gestures that the boys and girls produced during the observation sessions and found no differences: Mboys = 95.7 (SD = 47.44) vs. Mgirls = 111.9 (SD = 47.18), F(1, 38) = 1.16, ns. Both boys, F(5, 80) = 5.0, p < .001, and girls, F(5, 85) = 6.85, p < .001, increased their gesture production over time. Moreover, boys and girls did not differ in the types of gestures they produced. Deictic gestures (e.g. point at cat) were the most common gesture type, constituting 76% (SD = 10.7) of gestures produced by boys and 72% (SD = 10.7) of gestures produced by girls. Conventional gestures (e.g. nodding the head to mean yes) accounted for another 22% (SD = 10.3) and 25% (SD = 10.5) of the gestures produced by boys and girls, respectively. Iconic gestures were used rarely by children of either sex, accounting for 2 to 3% of the gestures in each group. A detailed summary of the changes in children's gesture production by age can be found in Table A in the Appendix.

Despite the fact that the boys and girls did not differ in the numbers and types of gestures they used, they did differ in the onset of their supplementary G+S combinations. As predicted, boys began producing supplementary G+S combinations later than girls. The mean onset age for G+S combinations was 19.11 (SD = 3.6) for boys, which was significantly later than the onset age for girls, 16.36 (SD = 2.7) months, F(1, 38) = 7.74, p < .01. At 14 months, two of the 18 boys were producing supplementary G+S combinations, compared to 12 of the 22 girls (X2(1) = 6.41, p = .02).

Boys also took their initial step into multi-word speech later than girls. The mean onset age for S+S utterances was 20.9 (SD = 3.3) months for boys, which was significantly different from the onset age for girls, 17.3 months (SD = 3.6), (F(1, 38) = 10.64, p < .002). At 14 months, none of the 18 boys but 10 of the 22 girls were producing S+S combinations (X2(1) = 8.62, p < .01) and, even by 18 months, only eight of the 18 boys were producing S+S combinations, compared to 17 of the 22 girls (X2(1) = 3.26, p < .10).

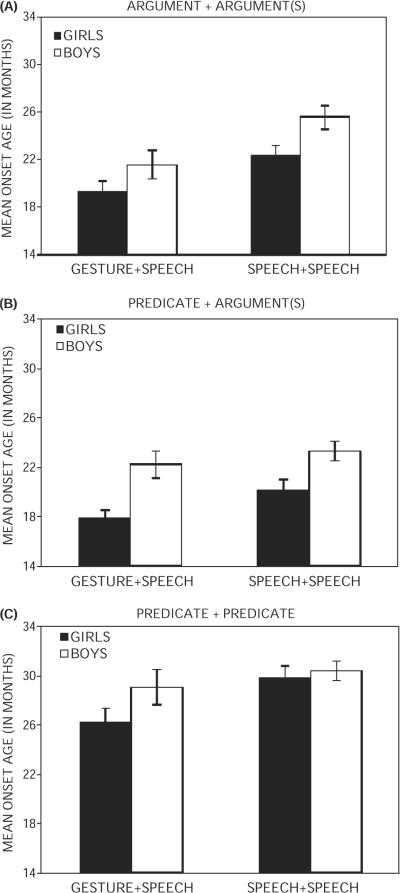

Are the early sex differences we see in G+S combinations related to the later sex differences in S+S utterances? If so, G+S combinations conveying particular meanings ought to herald the onset of S+S combinations conveying those same meanings in both boys and girls. To explore this hypothesis, we turn to the types of meanings conveyed in the children's supplementary G+S combinations, comparing them to their S+S utterances. Figure 1 displays the mean onset age in months for each of the three sentential construction types – argument+argument(s), predicate+argument(s), predicate+predicate – produced either in a G+S combination or in an S+S utterance for boys (white bars) and girls (black bars).

Figure 1.

Mean onset age (in months) of combinations with two or more argument (A), combinations with a predicate and at least one argument (B), or combinations with two predicates (C), in gesture+speech (G+S) and speech+speech (S+S) combinations produced by boys (white bars) and girls (black bars).

Argument+argument constructions

Boys produced argument+argument (s) meanings later than girls – both in G+S combinations (M = 21.6 [SD = 5.1] vs. M = 19.3 [SD = 4.3] months) and in S+S combinations (M = 25.6 [SD = 4.3] vs. M = 22.4 [SD = 3.9] months). There was a significant effect of modality (argument+argument meanings were expressed at a younger age in G+S than in S+S, F(1, 38) = 25.78, p < .001), and a significant effect of sex (argument+argument meanings were expressed at a younger age in girls than in boys, F(1, 38) = 5.09, p = .03). Importantly, there was no interaction between modality and sex, F(1, 38) = .42, ns; in other words, the time between the onset of the argument+argument construction in G+S and its later onset in S+S did not differ comparing boys and girls.

Next we asked whether this developmental pattern characterized individual children as well as the group as a whole. To address this question, we classified children according to whether they produced the construction in one format (either in G+S or S+S) or in both formats (both G+S and S+S) over the six observation sessions. Children who produced the construction in both formats were further classified according to whether they produced the construction first in G+S, first in S+S, or in both formats at the same time. We found that by 34 months, all but one of the children (one boy) produced the argument+argument construction in both formats. A few of these children (four boys, four girls) produced the construction for the first time in both formats in the same observation session; these children neither prove nor disprove our hypothesis, as we do not know which modality the child used first. Of the children who produced the construction in both formats but in different observation sessions, significantly more produced the construction in G+S than in S+S for both boys (13 vs. 0, X2(1) = 17.34, p < .001) and girls (14 vs. 4, X2(1) = 7.62, p < .01).

Predicate+argument constructions

Boys produced predicate+argument (s) meanings later than girls in G+S combinations (M = 22.2 [SD = 4.6] vs. M = 17.8 [SD = 3.4] months) and in S+S combinations (M = 23.3 [SD = 3.4] vs. M = 20.2 [SD = 3.8] months). There was again a significant effect of modality (predicate+argument meanings were expressed at a younger age in G+S than in S+S, F(1, 38) = 6.05, p < .02), and a significant effect of sex (predicate+argument meanings were expressed at a younger age in girls than in boys, F(1, 38) = 14.63, p < .001). Importantly, again, there was no interaction between modality and sex, F(1, 38) = .79, ns, suggesting that the time between the onset of the predicate+argument construction in G+S and its onset in S+S did not differ comparing boys and girls.

Turning to the individual data, we found that seven boys and eight girls produced the construction for the first time in both formats in the same observation session. Of the remaining children who produced the construction in both formats but at different observation sessions, girls reliably produced the construction first in G+S vs. S+S (11 vs. 3, X2(1) = 5.13, p < .05). Boys also tended to produce the construction first in G+S vs. S+S, but the effect did not reach statistical significance (7 vs. 4, X2(1) = 0.52, ns).

Predicate+predicate constructions

The predicate+predicate construction was the last of the three constructions to be produced by both boys and girls in G+S combinations (Mboys = 29.1, [SD = 6.1] vs. Mgirls = 26.2 [SD = 5.6] months) and in S+S combinations (Mboys = 30.4 [SD = 3.3] vs. Mgirls = 29.8 [SD = 4.8] months). There was a significant effect of modality (predicate+predicate meanings were expressed at a younger age in G+S than in S+S, F(l, 38) = 10.4, p < .01), but no reliable effect of sex, F(l, 38) = 1.57, ns. Importantly, there was no interaction between modality and sex, F(1, 38) = 2.23, ns, showing that the absence of a sex diference in onset was found in both G+S and S+S combinations.

In terms of individual patterns, one boy and one girl never produced a predicate+predicate construction during our observations; two girls produced the construction only in G+S and two boys produced it only in S+S; eight girls and one boy produced the construction for the first time in both formats in the same observation session. Of the remaining children who produced the construction in both formats but at different observation sessions, more children produced it first in G+S than in S+S for both boys (10 vs. 4, X2(l) = 2.92, p < .10) and girls (10 vs. 1, X2(l) = 7.76, p < .01). In other words, even though boys and girls did not differ in the onset of predicate+predicate constructions, both were more likely to produce the predicate+predicate construction first in G+S than in S+S.

Discussion

Boys lag behind girls in most early speech constructions (Maccoby, 1966; Kimura, 1998). Our study asked whether the sex differences observed in the onset of multi-word sentence constructions are preceded by sex differences in the onset of gesture+speech constructions of the same type. We found that they are.

Boys lagged behind girls in the onset of two constructions (argument+argument and argument+predicate) in speech+speech combinations and, several months earlier, also lagged behind girls in the onset of these same constructions in gesture+speech combinations. Boys did not lag behind girls in the onset of the late-acquired predicate+predicate construction in speech+speech combinations and, importantly, also did not lag behind girls in the onset of this construction in gesture+speech combinations. Gesture+speech is thus a good index of whether there will, or will not, be a sex difference in the acquisition of a particular construction. Moreover, because gesture+speech combinations are produced earlier than speech+speech combinations, children's gestures provide the first sign that boys are likely to lag behind girls in the onset of sentence constructions.

Our findings raise two additional questions. First, why do children, both boys and girls, display their earliest linguistic skills in gesture rather than speech? Second, why are girls more linguistically precocious than boys in both gesture and speech?

Why do children's earliest linguistic achievements appear in gesture rather than speech?

We have shown here that children, both girls and boys, express their earliest sentences in gesture before expressing them in speech. This phenomenon turns out to be a general one – gesture has been shown to capture the first stages of a cognitive skill in a variety of areas. For example, toddlers in a word learning study frequently referred to objects using gestures that conveyed information that was more accurate than the information conveyed in the accompanying speech (Capone, 2007). As another example, 5- to 8-year-old children on the verge of learning about conservation problems display a more correct understanding of the problems in gesture than in the accompanying speech (Church & Goldin-Meadow, 1986), as do 9- to 10-year-old children solving mathematical equivalence problems (Alibali & Goldin-Meadow, 1993; Perry, Church & Goldin-Meadow, 1988). The gestures that accompany speech thus appear to be the first reliable index of a child's burgeoning knowledge on a variety of tasks, including early language learning (see Capone & McGregor, 2004, for a review of how gesture predicts spoken language milestones in clinical populations).

But why is it easier to express information (or at least certain kinds of information) in gesture than in speech? One possibility is that gestures (particularly pointing gestures) are easier to produce than speech, which depends on complex articulation mechanisms (Acredolo & Goodwyn, 1988). A second possibility is that gesture may put fewer demands on working memory than speech. Speech conveys meaning by rule-governed combinations of discrete units that are codified according to the norms of the language. In contrast, gesture conveys meaning idiosyncratically by means of varying forms that are context-sensitive (Goldin-Meadow & McNeill, 1999; McNeill, 1992). Pointing at an object to label that object, or creating an iconic gesture on the fly while describing the action to be performed on the object, may be cognitively less demanding than producing words for these ideas.

Consistent with this hypothesis, children who experience temporary difficulties in oral language acquisition often revert to gestural devices to compensate for their deficiencies (Acredolo & Goodwyn, 1998; Thal & Tobias, 1992). Moreover, experimental studies have shown that gesturing while speaking can lighten speakers' cognitive load. Speakers, both children and adults, when asked to remember a list of unrelated items while explaining their solutions to a math problem, remember more of those items if they gesture during their explanations than if they do not gesture (Goldin-Meadow, Nusbaum, Kelly & Wagner, 2001; Wagner, Nusbaum & Goldin-Meadow, 2004). Gesturing thus eases the process of speech production, providing speakers – including young speakers at the early stages of language learning – with extra cognitive resources. As such, it may be cognitively less demanding to express a proposition in a gesture+speech combination than in speech alone, leading to the earlier emergence of semantic relations across gesture and speech than entirely within speech.

Why are girls more linguistically precocious than boys in both gesture and speech?

One possible explanation for the early sex differences we have found is that parents of boys and girls may differ in the types of words and gestures that they use with their children. Early findings suggested that mothers speak more to daughters than to sons (Cherry & Lewis, 1976). But this finding has been challenged by later work showing no differences in how mothers talk to daughters vs. sons (Huttenlocher et al., 1991). However, parents might use different gestures when talking to girls vs. boys. Parents of girls might convey sentential constructions in gesture+speech at higher rates than parents of boys, leading girls to produce sentence-like ideas in gesture +speech earlier than boys, which, in turn, might lead girls to produce these same ideas entirely in speech earlier than boys. Our previous work (Özçalişkan & Goldin-Meadow, 2005b, 2006) examined the speech and gestures that the primary caregivers of the 40 children described in our study produced when interacting with their children. We found that the caregivers used gesture+speech combinations conveying sentential meanings frequently throughout all of the observation sessions we coded (from child age 14 to 34 months). Importantly, however, the caregivers used roughly comparable numbers of supplementary gesture+speech combinations when talking to both girls (M = 13.88 [SD = 12.47]) and boys (M = 17.22 [SD = 14.32]), F(l, 165) = .53, ns. Thus, input differences in gesture+speech are an unlikely explanation for the sex differences we have found in children's sentence-making abilities at the early ages.

A second possibility is that early sex differences in the onset of sentence constructions reflect cognitive differences in girls' and boys' understanding of the semantic relations between objects and/or actions. Girls may understand that arguments can be related to other arguments and/or predicates in meaningful ways at an earlier age than boys, and may display their new-found knowledge in both gesture and speech before boys do. To gather evidence that bears on this hypothesis, we would need to probe children's understanding of the semantic relations relevant to language in a non-communicative task. The hypothesis would predict that girls ought to have an advantage over boys here as well.

A third possible explanation for the sex differences in children's early sentence-making abilities is that these differences might reflect sex differences in motor development. Previous research has shown that while boys tend to perform better in gross motor abilities that require power and force (e.g. kicking, jumping), girls outperform boys in fine motor abilities such as drawing and writing (Cameron, 2002; Malina, 1998). In fact, sex differences in fine motor abilities become evident at very young ages. A study of neonatal imitation in 1- to 3-dayold infants showed that newborn girls were better at imitating fine motor finger extensions than newborn boys (Nagy, Kompagne, Orvos & Pal, 2007). These differences in early imitation abilities continue well into early preschool years, with 3–5-year-old girls also showing better performance in imitating symbolic gestures (e.g. enacting how to brush one's teeth without the brush) than boys of the same age (Chipman & Hampson, 2007). Moreover, children's first pointing gestures are typically preceded by the onset of the pincer grip (i.e. the ability to grasp a small object between thumb and forefinger); girls not only tend to show a slight advantage in the onset of the pincer grip relative to boys, but they also tend to produce their first pointing gestures earlier than boys (Butterworth & Morisette, 1996). In fact, a great number of studies suggest a close coupling between the development of language, gesture and fine motor action (see Iverson & Thelen, 1999, for a review). Thus, early sex differences in fine motor abilities could well have led to the sex differences we found in the onset of gesture+speech combinations. In turn, these early sex differences in gesture+speech combinations could have led to the sex differences we observed in the onset of speech+speech utterances (see Goldin-Meadow, Cook & Mitchell, 2009, for evidence that the act of producing a new idea in gesture on a math task can lead to the incorporation of that new idea in speech). Under this view, the sex differences in gesture+speech not only provide the first sign that boys are going to lag behind girls in the acquisition of early sentence constructions, but they may even play a role in creating that lag.

Do the sex differences we have observed in the onset of different sentence constructions in gesture have long-term effects? We know from previous work (Rowe & Goldin-Meadow, 2009) that the number of different objects a child indicates in gesture at 14 months is a significant predictor of the child's vocabulary size at 54 months. We also know that females in their teen to adult years continue to show superior performance relative to boys in high-level verbal tasks such as comprehension of difficult written material and creative writing (Kimura, 1998; Maccoby & Jacklin, 1974). Perhaps the early differences we find in the onset of sentence constructions in gesture+speech establish a slight advantage for girls, an advantage that is maintained throughout development and adulthood. But if so, the fact that we do not see reliable differences between boys and girls in the onset of predicate+predicate constructions (the last of the three constructions acquired during our observation period) is somewhat unexpected. Additional research is needed to determine whether this is, in fact, a robust effect. However, the important result from the point of view of our study is that we see the same pattern in gesture+speech and speech+speech constructions – where there is a reliable sex difference in gesture+speech combinations expressing a particular construction, there will be a later reliable difference in the parallel speech+speech construction.

In conclusion, we have found that sex differences in communicative abilities appear in gesture combined with speech before they appear in speech combined with speech. Boys combine gestures with words to convey sentential meanings later than girls, and then, several months later, combine words with other words to convey the same meanings entirely within speech, again later than girls. Gesture, when considered in relation to speech, thus provides the first reliable sign of a child's burgeoning sentential abilities, which blossom in boys later than in girls.

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Schonwald and J. Voigt for their administrative and technical help, and K. Brasky, E. Croft, K. Duboc, Becky Free, J. Griffin, S. Gripshover, C. Mean-well, E. Mellum, M. Nikolas, J. Oberholtzer, L. Rissman, L. Schneidman, B. Seibel, K. Uttich, and J. Wallman for help in data collection and transcription. This research was supported by grant P01HD40605 to Susan Goldin-Meadow. We also thank Dr Nuria Sebastian-Galles and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript, which improved the manuscript in significant ways.

Appendix

Table A.

Summary of children's gesture production by age and sex of the childa

| 14 months | 18 months | 22 months | 26 months | 30 months | 34 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean number of gesture tokens (SD) | ||||||

| Girls | 65 (41) | 106 (73) | 129 (69) | 127 (67) | 138 (64) | 114 (65) |

| Boys | 40 (25) | 74 (49) | 106 (81) | 137 (112) | 105 (70) | 109 (66) |

| Mean number of deictic gestures (SD) | ||||||

| Girls | 38 (27) | 77 (62) | 97 (60) | 96 (55) | 104 (56) | 85 (45) |

| Boys | 24 (18) | 55 (48) | 88 (72) | 108 (106) | 77 (41) | 86 (58) |

| Mean number of conventional gestures (SD) | ||||||

| Girls | 26 (25) | 28 (16) | 28 (22) | 26 (19) | 28 (23) | 26 (23) |

| Boys | 16 (11) | 19 (20) | 17 (17) | 26 (28) | 19 (19) | 20 (26) |

| Mean number of iconic gestures (SD) | ||||||

| Girls | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 5 (8) | 6 (7) | 4 (4) |

| Boys | 0 (0) | 0.4 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | 3 (6) | 3 (4) |

SD = standard deviation; the numbers are rounded up to the closest whole number. Each child was observed for approximately 90 minutes at each observation session.

Footnotes

Children's early spontaneous iconic gestures also occasionally convey information about perceptual properties associated with an object, such as its shape or size (pinching fingers to indicate small size), as well as spatial relationships between objects (tracing a vertical line to indicate direction of motion) (Acredolo & Goodwyn, 1985; Özçalişkan, Gentner & Goldin-Meadow, 2009).

We refer to these early speech+speech and gesture+speech combinations as `sentence constructions'. However, since many of the combinations lacked an explicit verb or predicating action gesture, these constructions should not be considered full-blown grammatical sentences in the adult sense of the term.

The original data analysis was conducted on the entire sample with no analysis of sex differences, and included only the observation sessions between 14 and 22 months.

References

- Acredolo LP, Goodwyn SW. Symbolic gesturing in language development. Human Development. 1985;28:40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Acredolo LP, Goodwyn SW. Symbolic gesturing in normal infants. Child Development. 1989;59:450–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alibali MW, Goldin-Meadow S. Gesture–speech mismatch and mechanisms of learning: what the hands reveal about a child's state of mind. Cognitive Psychology. 1993;25:468–523. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1993.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates E. Language and context. Academic Press; New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bates E, Benigni L, Bretherton I, Camaioni L, Volterra V. The emergence of symbols: cognition and communication in infancy. Academic Press; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth G, Morisette P. Onset of pointing and the acquisition of language in infancy. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 1996;14(3):219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron N, editor. Human growth and development. Academic Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Capone NC. Tapping toddlers' evolving semantic representation via gesture. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2007;50:732–745. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/051). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone NC, McGregor KK. Gesture development: a review of clinical and research practices. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:173–186. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry L, Lewis M. Mothers and two-year-olds: a study of sex differentiated aspects of verbal interaction. Developmental Psychology. 1976;12:278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Chipman K, Hampson E. A female advantage in the imitation of gestures by preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2007;31(2):137–158. doi: 10.1080/87565640701190692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church RB, Goldin-Meadow S. The mismatch between gesture and speech as an index of transitional knowledge. Cognition. 1986;23:43–71. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(86)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, Butcher C. Pointing toward two word speech in young children. In: Kita S, editor. Pointing: Where language, culture, and cognition meet. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 2003. pp. 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, Cook SW, Mitchell ZA. Gesturing gives children new ideas about math. Psychological Science. 2009;20(3):267–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, McNeill D. The role of gesture and mimetic representation in making language the province of speech. In: Corbalis M, Lea S, editors. The descent of mind. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. pp. 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, Nusbaum H, Kelly SD, Wagner S. Explaining math: gesturing lightens the load. Psychological Science. 2001;12(6):516–522. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher J, Haight W, Bryk A, Seltzer M, Lyons T. Early vocabulary growth: relation to language input and gender. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(20):236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JS, Linn MC. Gender differences in verbal ability: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;104(1):53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson JM, Goldin-Meadow S. Gesture paves the way for language development. Psychological Science. 2005;16:368–371. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson JM, Thelen E. Hand, mouth and brain. Journal of Conciousness Studies. 1999;6:11–12. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura D. Sex and cognition. The MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E. The development of sex differences. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, Jacklin CN. The psychology of sex differences. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill D. Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about language and thought. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Malina RM. Motor development and performance. In: Ulijaszek SJ, Johnston FE, Preece MA, editors. The Cambridge encyclopedia of human growth and development. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1998. pp. 247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy E, Kompagne H, Orvos J, Pal A. Gender-related differences in neonatal imitation. Infant and Child Development. 2007;16:267–276. [Google Scholar]

- Özçalişkan Ş, Gentner D, Goldin-Meadow S. Do iconic gestures pave the way for children's early verbs? 2009. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalişkan Ş, Goldin-Meadow S. Gesture is at the cutting edge of early language development. Cognition. 2005a;96(3):B101–B113. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalişkan Ş, Goldin-Meadow S. Do parents lead their children by the hand? Journal of Child Language. 2005b;32(3):481–505. doi: 10.1017/s0305000905007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalişkan Ş, Goldin-Meadow S. Role of gesture in children's early constructions. In: Clark Eve, Kelly Barbara., editors. The acquisition of constructions. CSLI Publications; Stanford, CA: 2006. pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Özçalişkan Ş, Levine S, Goldin-Meadow S. Gesturing with an injured brain: how gesture helps children with early brain injury learn linguistic constructions. 2009. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry M, Church RB, Goldin-Meadow S. Transitional knowledge in the acquisition of concepts. Cognitive Development. 1988;3:359–400. [Google Scholar]

- Ramer ALH. Syntactic styles in emerging language. Journal of Child Language. 1976;3:49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe ML, Goldin-Meadow S. Differences in early gesture explain SES disparities in child vocabulary size at school entry. Science. 2009;323:951–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1167025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer E, Levine SC, Goldin-Meadow S. Early gesture predicts language delay in children with pre- and perinatal brain lesions. 2009. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal D, Tobias S. Communicative gestures in children with delayed onset of oral expressive vocabulary. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1992;37:157–170. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3506.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner SM, Nusbaum H, Goldin-Meadow S. Probing the mental representation of gesture: is handwaving spatial? Journal of Memory and Language. 2004;50:395–407. [Google Scholar]