Abstract

Rationale

Recent studies have highlighted important roles of CaMKII in regulating Ca2+ handling and excitation-contraction coupling. However, the cardiac effect of chronic CaMKII inhibition has not been well understood.

Objective

We have tested the alterations of L-type calcium current (ICa) and cardiac function in CaMKIIδ knockout (KO) mouse left ventricle (LV).

Methods and Results

We used patch clamp method to record ICa in ventricular myocytes and found that in KO LV, basal ICa was significantly increased without changing the transmural gradient of ICa distribution. Substitution of Ba2+ for Ca2+ showed similar increase in IBa. There was no change in the voltage dependence of ICa activation and inactivation. ICa recovery from inactivation, however, was significantly slowed. In KO LV, the Ca2+-dependent ICa facilitation (CDF) and ICa response to isoproterenol (ISO) were significantly reduced. However, ISO response was reversed by β2-adrenergic receptor (AR) inhibition. Western blots showed a decrease in β1-AR and an increase in Cav1.2, β2-AR and Gαi3 protein levels. Ca2+ transient and sarcomere shortening in KO myocytes were unchanged at 1Hz but reduced at 3Hz stimulation. Echocardiography in conscious mice revealed an increased basal contractility in KO mice. However, cardiac reserve to workload and β-adrenergic stimulation was reduced. Surprisingly, KO mice showed a reduced heart rate in response to workload or β-adrenergic stimulation.

Conclusions

Our results implicate physiologic CaMKII activity in maintaining normal ICa, Ca2+ handling, excitation-contraction coupling and the in vivo heart function in response to cardiac stress.

Keywords: CaMKII, Calcium channel, myocytes, excitation-contraction coupling

INTRODUCTION

CaMKII is a multifunctional Ser/Thr protein kinase and a ubiquitously expressed multimer consisting of 8–12 subunits. This kinase has different isoforms in different tissues (α, β, γ, and δ). In heart, the δ isoform is predominant, and the γ isoform is expressed at low level1–4. CaMKII is an important regulator of several Ca2+ handling proteins and ion channels, prominent among them is the L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC)5;6.

LTCCs in myocytes are heteromultimers of at least three different subunits (α1c, α2δ, and β2). The pore-forming α1c subunit (Cav1.2) specifies basic channel characteristics. The α2δ and the auxiliary β subunit are powerful modulators of channel expression, open probability, activation, and inactivation7;8. ICa is the key mediator for excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling. Excitation leads to opening of LTCCs, which allows the entry of a relatively small amount of Ca2+ into the cell. The rise in intracellular Ca2+ is then amplified by Ca2+-triggered Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) through ryanodine receptors. The increase in [Ca2+]i from SR activates the myofilaments, leading to cell contraction.

LTCC in myocytes is regulated by multiple kinases, including PKA9, PKC10, CaMKII6, and calcineurin11. Among these regulatory pathways, PKA and CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation causes similar changes in ICa, including the increase in the channel open probability and the duration of the open state12. In addition, a complex interplay between PKA and CaMKII has been revealed13. Recent studies have demonstrated that β1-adrenergic receptor (AR) stimulation activates dual signaling pathways, cAMP/PKA and CaMKII, the former undergoing desensitization and the latter exhibiting sensitization with time13. This finding suggests that CaMKII signaling pathway may be more important for long term changes of Ca2+ handling in the diseased heart where increased sympathetic activation persists14. For instance, we found that in the pressure-overload heart failure mouse LV, ICa was significantly altered with an increased density and slowed inactivation time course, and these changes are mainly caused by the increased CaMKII activity6.

Although CaMKII activation has been linked to disease-related ICa remodeling and reduced E-C coupling, the role of physiologic CaMKII activity in the delicate regulation of ICa, Ca2+ handling, E-C coupling and heart function has not been completely understood. Here, we tested the effects of long term inhibition of basal CaMKII activity on the regulation of LTCC function, intracellular Ca2+ transient, ventricular myocyte sarcomere shortening and in vivo heart function by knocking out CaMKIIδ, the predominant isoform in heart.

METHODS

Isolation of ventricular myocytes

Mouse LV myocytes were isolated enzymatically by a protocol we described previously6

ICa recording

ICa was recorded at room temperature using whole-cell patch clamp methods described previously6

Ca2+ transient and sarcomere shortening measurements

Ca2+ transient and sarcomere shortening were recorded in myocytes using IonOptix with myocytes loaded with fura-2/AM.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed in conscious mice using a murine echo machine Visualsonics-RMV707B.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Sigmastat for Windows (Jandel Scientific). Paired and unpaired t-tests and one-way ANOVA analysis were used for comparisons and p < 0.05 was regarded as significant. Mann-Whitney Rank Sum tests were performed if tests for normality or equal variance failed.

Use of vertebrate animals

All experiments on live vertebrates were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the institution’s Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statement of responsibility

The authors had full access to the data and take full responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

RESULTS

CaMKII knockout (KO) mouse model

In our genetic mouse model, CaMKIIδ has been knocked out while the CaMKIIγ was unmodified15. These KO mice are healthy and behave normally. The heart weight to body weight ratio (mg/g) for KO and wild type (WT) mice was 4.83±0.1 (n=21) and 4.75±0.1 (n=23, p>0.05), respectively. The size of ventricular myocytes isolated from KO and WT mouse LV measured as cell capacitance was 159.10±3.34pF (n=212 from 35 KO mice) and 154.24±3.01pF (n=244 from 45 WT mice, p>0.05), respectively.

We measured total CaMKII activity in ventricular myocytes using CaMKII activity assay kit (SignaTECT®, Promega)6. In preparations of myocytes from 2 WT and 2 CaMKIIδ KO mice, CaMKII activity was 2.18±0.47 pmol/min/μg for WT and 0.83±0.25 pmol/min/μg for KO myocytes, ≈ 62% reduction in CaMKIIδ KO LV.

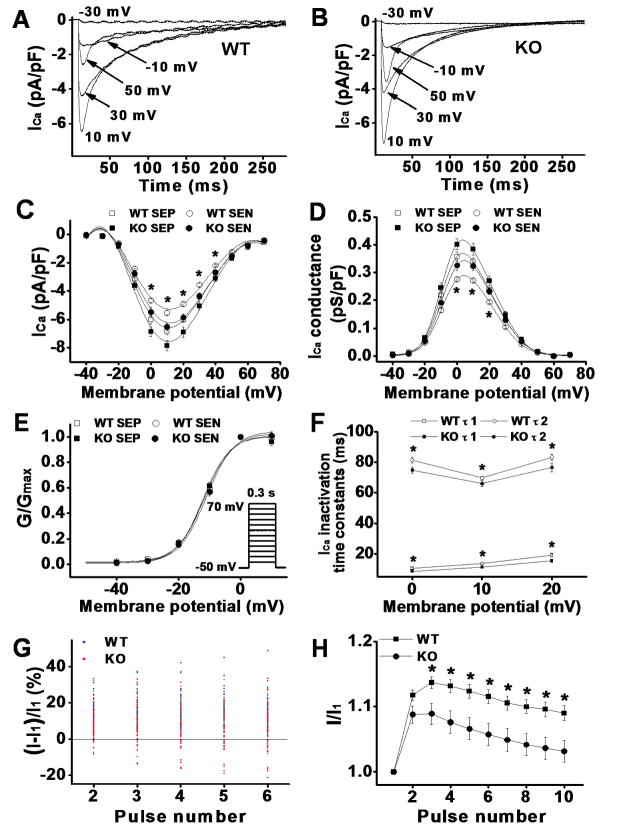

Increased L-type Ca2+ current density in CaMKIIδ KO LV

We recently reported the transmural gradient of ICa distribution in mouse heart LV6. To determine the transmural variation in ICa density, we isolated myocytes from the subendocardial (SEN) and subepicardial (SEP) regions of CaMKIIδ KO mouse LV and recorded ICa in these myocytes using whole-cell voltage clamp recording method. We found that ICa density was significantly larger in SEP than in SEN myocytes (Figure 1). For instance, the peak ICa (recorded at test potential of +10mV) was 7.85±0.4 pA/pF (n=25) for SEP and 6.5±0.3 pA/pF (n=21) for SEN myocytes, respectively (p<0.05). There was no difference in current decay kinetics or voltage-dependence of ICa activation between myocytes isolated from these 2 regions of LV. The transmural gradient of ICa density was similar to those recorded from WT LV, in which the peak ICa was 6.8±0.3 pA/pF (n=28) for SEP and 5.5±0.1 pA/pF (n=26) for SEN myocytes, respectively (p<0.05). These results suggest that CaMKII inhibition has no effects on the spatial heterogeneity of ICa distribution, consistent with our recently reported results6 that CaMKII activity is similar between SEP and SEN myocytes. However, we found that ICa density was significantly larger in KO LV than in WT LV. For instance, the peak ICa in the SEP and SEN myocytes from KO LV was 15% and 18% larger than the ICa recorded in these 2 regions of myocytes from WT LV, respectively (p<0.05). As shown in the ICa-voltage relationship (Figure 1C), the voltage-dependence of ICa activation was unchanged. This suggests that the increased ICa is likely an increase in calcium channel conductance but not the shifting of voltage-dependence of channel activation. To demonstrate this, we measured the channel conductance using equation Gc= I/(Vm−Vc), where Gc is the conductance, I is calcium current, Vm is the membrane potential, and Vc is the equilibrate potential. As predicted, calcium channel conductance was significantly larger in KO LV than in WT LV (Figure 1D). Normalizing channel conductance at each membrane potential to its maximum conductance for each individual myocytes revealed a V1/2 and a slope factor of −11.83±0.63 mV and 3.71±0.20 mV for WT (n=28) vs. −12.26±0.79 mV and 3.73±0.13 mV for KO myocytes (n=25), respectively (p>0.05) (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

A & B: Representative ICa traces recorded from WT and KO ventricular myocytes (SEN) by 300ms test pulses from a holding potential of −50mV to potentials between −30 to +50mV at pulse intervals of 10 s. ICa amplitude was increased and inactivation was accelerated at all test potentials in KO ventricular myocytes. C: ICa-voltage relationship in ventricular myocytes isolated from WT and CaMKIIδ KO LV. Current amplitudes were normalized to cell capacitance and plotted as mean values. D: Calcium channel conductance was normalized to cell capacitance and plotted as mean values. E: Normalized conductance-voltage relationship. F: Mean values of ICa inactivation time constants. τ1 and τ2 denote fast and slow inactivation time constants, respectively. G: Percentage changes of ICa at each stimulation pulse relative to the ICa at first pulse with 1 Hz stimulation. Blue and red dots represent changes of ICa from individual WT and KO myocytes, respectively. H: Normalized ICa facilitation from WT and the KO myocytes that showed positive ICa staircase. Vertical bars represent S.E.M.; * denotes p<0.05.

Accelerated ICa inactivation in CaMKIIδ KO LV

To test the biophysical characteristics of ICa in KO myocytes, we evaluated the kinetics of ICa inactivation (current decay). Comparing to the WT, ICa inactivation was accelerated significantly and similarly in SEP and SEN myocytes isolated from KO LV. To quantify these changes, ICa inactivation phase was fit by 2 exponential functions6. Mean values of the fast (τ1) and slow (τ2) time constants in WT (n=20) and KO myocytes (n=17) revealed robust differences (Figure 1F). ICa inactivation was significantly accelerated at all testing potential levels in KO myocytes (Figure 1 & Table 1). The accelerated ICa inactivation is consistent with the reduced CaMKII-dependent LTCC phosphorylation.

Table 1.

ICa characteristics recorded in WT and CaMKIIδ KO LV.

| WT | KO | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean ± S.E.M | n | Mean ± S.E.M | |||

| ICa density (+ 10mV) | SEP (pA/pF) | 28 | −6.8±0.3 | 25 | −7.9±0.4 | <0.01 |

| SEN (pA/pF) | 26 | −5.5±0.1 | 21 | −6.5±0.3 | <0.01 | |

| ICa decay time constants at + 10mV | τ1 (fast, ms) | 20 | 13.6±0.9 | 17 | 11.3±0.7 | <0.05 |

| τ2 (slow, ms) | 20 | 69.7±1.1 | 17 | 65.9±1.9 | <0.05 | |

| ICa activation kinetics | V1/2 (mV) | 50 | −8.5±0.4 | 41 | −8.4±0.6 | NS |

| k | 50 | 5.2±0.1 | 41 | 5.4±0.1 | NS | |

| ICa inactivation kinetics | V1/2 (mV) | 22 | −24.3±0.6 | 23 | −24.0±0.7 | NS |

| k | 22 | 5.6±0.2 | 23 | 6.0±0.2 | NS | |

| ICa recovery time constants | τ (ms) | 24 | 213.3±6.0 | 27 | 240.4±8.4 | <0.01 |

| ICa facilitation | Positive cell | 77/77 | 36/46 | |||

| % increase in ICa | 77 | 15.1±1.0 | 36 | 12.2±1.2 | <0.05 | |

WT: wild type; KO: CaMKII knockout; SEP: subepicardial myocytes; SEN: subendocardial myocytes; V1/2: half-maximal activation or inactivation; K: slop factor; τ: time constant.

Reduced ICa facilitation in CaMKIIδ KO LV

CaMKII activation is a major mediator for the Ca2+-dependent ICa facilitation (CDF) in myocytes16;17. Here, we measured ICa facilitation in CaMKIIδ KO ventricular myocytes. Consistent with the reduced CaMKII activity in KO myocytes, ICa facilitation was observed in all recorded WT myocytes (n=77) but only in 76% of KO myocytes (n=46). In fact, instead of ICa facilitation, a negative ICa staircase was observed in 24% of KO myocytes (Figure 1G). Moreover, in those KO myocytes where ICa facilitation presents, the magnitude of ICa facilitation was significantly smaller than that recorded in WT myocytes (Figure 1H & Table 1). These results indicate that inhibition of physiologic CaMKII activity in myocytes may significantly affect Ca2+ influx at fast heart rate by reduction of CDF.

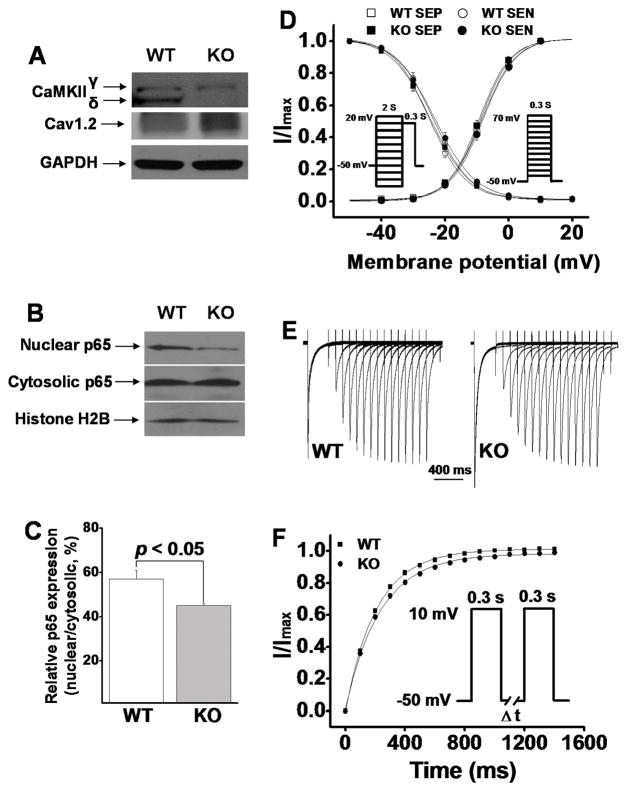

Molecular mechanisms underlying ICa alteration in CaMKIIδ KO myocytes

It is known that CaMKII plays a stimulatory role in ICa regulation. Acute inhibition of CaMKII reduces the amplitude of basal ICa6. Interestingly, we observed a significantly increased ICa density in ventricular myocytes from CaMKIIδ KO LV. Clearly, this cannot be explained by CaMKII inhibition. To test the molecular mechanisms for this observation, we measured protein levels of Cav1.2 and found that the Cav1.2 protein level was increased in KO myocytes by ≈ 12% compared to WT LV (Figure 2A, Figure 3E). This percent increase in Cav1.2 protein level is consistent with the percent increase in ICa density. Thus, it is likely the molecular basis for the increased ICa in KO myocytes.

Figure 2.

A: Representative Western blots showing ablated CaMKIIδ and increased Cav1.2 expression in CaMKIIδ KO LV. B: Western blots showing that NFkB component p65 nuclear translocation is reduced in KO LV. C: The mean values of relative nuclear portion p65 (nuclear/cytosolic, n=3) in WT and KO LV. D: Normalized voltage-dependence of ICa activation and inactivation. The recording protocols are shown as insets. E: Representative ICa recovery traces recorded (in SEN myocytes) from WT and KO ventricular myocytes, respectively. F: Mean values of normalized peak ICa (I/Imax) for ICa recovery from inactivation. The inset denotes recording protocol.

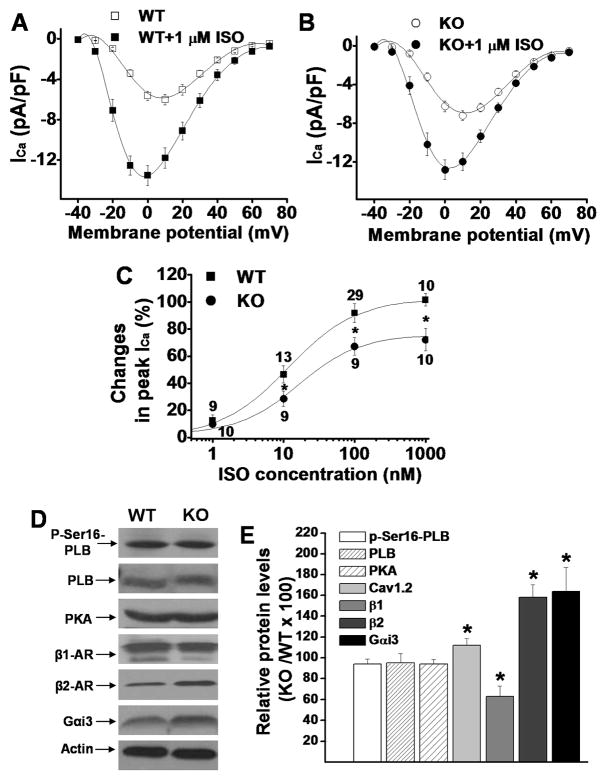

Figure 3.

Panel A & B: Mean values of voltage-dependent ICa activation before and after ISO perfusion in ventricular myocytes isolated from WT and KO LV, respectively. Panel C: Dose-response relationship of peak ICa recorded in WT and KO LV in the presence of different concentrations of ISO. Panel D: Representative Western blot results for protein levels of p-Ser16-PLB, PLB, PKA, β1-AR, β2-AR, and Gαi3 (actin was used as loading control) in the WT and CaMKIIδ KO LV. The protein levels in KO LV relative to the levels in WT LV are statistically summarized in panel E (each value is a mean from 3 hearts). Vertical bars represent S.E.M. * denotes p<0.05, compared to proteins in WT.

Recent studies have shown that CaMKII phosphorylates nuclear factor-kappaB (NFkB) component p65 and causes a nuclear translocation, leading to suppression of Cav1.2 channel expression18;19. These findings revealed an inhibitory role of CaMKII in Cav1.2 channel expression. In KO ventricular myocytes, the decrease in CaMKII activity may remove this inhibition by preventing p65 nuclear translocation. Indeed, Western blot results demonstrated a significant reduction of nuclear p65 in KO ventricular myocytes (Figure 2B&C). These results, then, well corroborate the increase in Cav1.2 expression observed in KO LV.

Voltage-dependence of ICa activation and inactivation

To determine the voltage dependence of ICa inactivation, we used a two-pulse protocol (inset of Figure 2D, left) with a 2000ms conditioning pulse at different potentials ranging from −80mV to +20mV (from a holding potential of −50mV), followed by a 300ms test pulse to +10mV. For the voltage dependence of ICa activation, we used a holding potential of −50mV and steps of 300ms duration test pulses from −40 to +70mV in 10mV steps (inset of Figure 2D, right). Using these approaches, we detected no significant voltage-dependent differences in ICa activation and inactivation between myocytes from WT and KO LV (Figure 2D). Because there were no statistical differences in activation and inactivation kinetics of ICa between SEP and SEN myocytes in either WT or KO LV, we analyzed these kinetics by not separating SEN and SEP myocytes. The half-maximal activation and inactivation voltages and slope factors in WT and KO LV were summarized in Table 1.

Taken together, these data revealed that ICa density is significantly increased in KO LV with increased Cav1.2 expression as the molecular basis, while the voltage dependence of ICa activation and inactivation are not altered.

Slowed ICa recovery from inactivation in CaMKIIδ KO LV

To evaluate the kinetics of ICa recovery from inactivation, we held cells at a holding potential of −50mV and applied a 300ms pulse to +10mV, followed by a variable time period (ΔT) at −50mV and a 300ms test pulse to +10mV (Figure 2F, inset). The time course of ICa recovery from inactivation was evaluated by fitting data for each cell with a mono-exponential equation. In both WT and KO LVs, we did not detect significant differences in ICa recovery time constants between SEP and SEN myocytes. However, in KO LV, ICa recovery from inactivation was significantly slowed (Figure 2E&F, Table 1). The slowed ICa recovery time course in KO ventricular myocytes (where CaMKII activity is chronically inhibited) is consistent with the results from acute CaMKII inhibition in ventricular myocytes20 and SA node cells21.

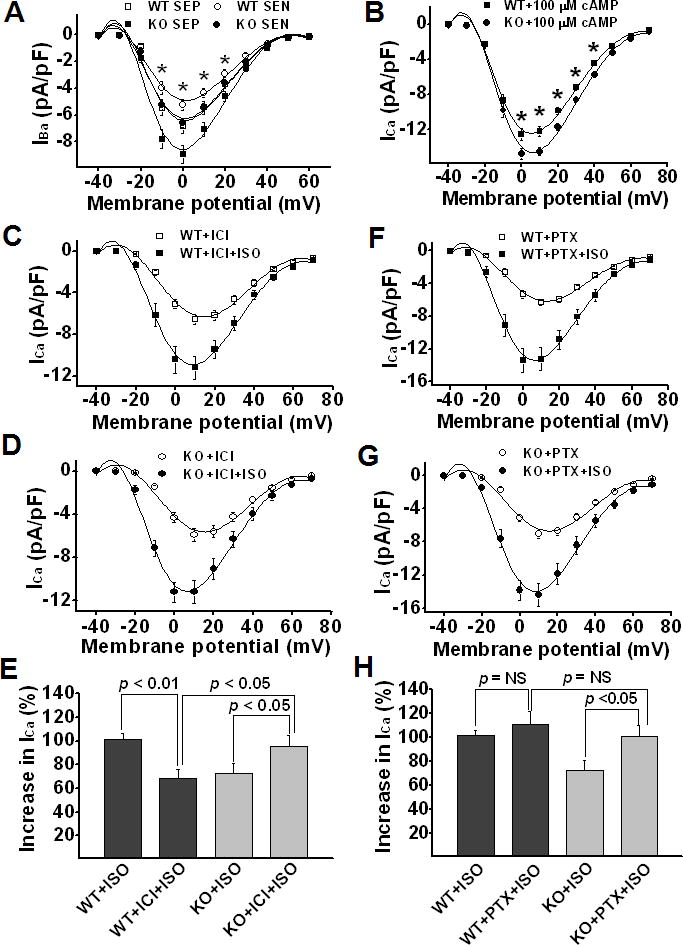

Reduced ICa response to β-adrenergic stimulation in CaMKIIδ KO LV

β-adrenergic stimulation is the major ICa regulator in heart, which is mediated by both PKA and CaMKII Pathways. Here, we tested ICa response to β-adrenergic stimulation in CaMKIIδ KO ventricular myocytes. After basal ICa was determined, myocytes were exposed to isoproterenol (ISO) at different concentrations (1nM, 10nM, 100nM and 1μM). When ICa amplitude reached the steady-state, myocytes were then exposed to the next ISO concentration. We found that ICa response to ISO was significantly reduced in KO myocytes compared to WT (Figure 3A & B). As shown in the dose-response relationship (Figure 3C), the IC50 was 12.15±1.19nM for WT and 15.70±3.05nM for KO myocytes (p<0.05). The maximum increase in ICa by 1 μM ISO was 104.67±2.24% for WT and 74.28±3.25% for CaMKIIδ KO myocytes, respectively. ICa-voltage relationship showed that ISO (1 μM) shifted the peak ICa potential from +10mV to 0mV in both WT and KO myocytes, a 10mV shift to the left (Figure 3A & B). These results suggest that inhibition of the physiologic CaMKII activity significantly reduces β-adrenergic regulation on ICa. The ISO-induced shifting of I–V relationship has been reported previously, and the underlying mechanisms involve the increased calcium channel availability and opening probability, although their quantitative importance varies from heart tissues22;23. The shifting of ICa-voltage relationship suggests a membrane potential-dependent potentiating effect on ICa.

To further explore the mechanisms for the increased ICa density and reduced ICa response to β-adrenergic stimulation in KO LV, we measured the protein levels of PKA-dependent phospholamban (PLB) phosphorylation at Ser16 (p-Ser16-PLB), total PLB, PKA, β-ARs and the receptor-coupled GTP-binding protein (Gs and Gi) protein levels in WT and KO LV. Our results revealed no change in protein levels of p-Ser16-PLB, PLB, PKA and Gs. However, a decrease in β1-AR and an increase in β2-AR and the inhibitory G protein Gαi3 levels were observed in KO LV. The β1-AR protein level was reduced by 37%, while the β2-AR and Gαi3 levels were increased by 58 % and 64 %, respectively (Figure 3D & E). The changes of β-ARs and Gαi3 can explain the reduced response of ICa to β-adrenergic stimulation in KO myocytes. Unlike the AC3-I mouse model, in which CaMKII activity was totally inhibited and a significant increase in PKA activity was reported24, in our CaMKIIδ KO mouse model, levels of PKA expression and PKA-dependent PLB phosphorylation at Ser16 were unchanged (Figure 3D & E).

Barium current (IBa) density in CaMKIIδ KO LV

We showed a significant increase in LTCC α-subunits Cav1.2 expression in CaMKIIδ KO LV, which is consistent with the increase in ICa density seen in these myocytes. To further demonstrate that the increase in ICa density is a result of increased channel expression but not Ca2+-related process, we substituted Ba2+ for Ca2+ in the ICa recording solution and recorded IBa. Similar to ICa, IBa current density was significantly larger in both SEP and SEN myocytes in KO LV than in WT LV (Figure 4A). For instance, the peak IBa was 6.84±0.55 pA/pF (n=15) for SEP and 5.24±0.42 pA/pF (n=15) for SEN myocytes in WT vs. 8.95±0.66 pA/pF (n=16) for SEP and 6.61±0.28 pA/pF (n=17) for SEN myocytes in KO, respectively (p<0.05 for SEP vs. SEN and WT vs. KO). These results further point to the increased Cav1.2 expression as the molecular basis of increased ICa in CaMKIIδ KO LV.

Figure 4.

Panel A: Mean values of IBa-voltage relationship. Panel B: Mean values of ICa recorded in WT and KO ventricular myocytes after internal diffusion of 100 μM 8-bromo-cAMP. Panel C&D: ISO effect on ICa recorded in WT and KO ventricular myocytes in the presence of β2-AR specific antagonist ICI118,551. Panel E: ISO (1 μM)-induced percent increase in peak ICa in WT and KO ventricular myocytes in the presence of ICI118,551. Panel F&G: ISO effect on ICa recorded in WT and KO ventricular myocytes in the presence of Gi inhibitor PTX. Panel H: ISO-induced percent increase in peak ICa in WT and KO ventricular myocytes in the presence of PTX. Vertical bars represent S.E.M.; * denotes p<0.05.

The reduced response to β-adrenergic stimulation was reversed by bypass or blockade of β2-AR

We propose that the increase in β2-AR and Gαi3 expression levels is the molecular basis for the reduced ICa response to ISO in KO myocytes. To further demonstrate this, we added 100 μM 8-Br-cAMP into patch pipette solution to bypass the β-AR-mediation of ISO response25. As predicted, in the presence of 8-bromo-cAMP, ICa density was significantly larger in KO than in WT LV (Figure 4B), indicating a reversal of β-adrenergic response in KO myocytes. The larger ICa density in KO myocytes is consistent with the larger density of Cav1.2 expression. These results highly suggest that alterations of β2-AR and Gαi3 expression play an important role in the reduced ICa response to β-adrenergic stimulation in KO myocytes. After bypass of β2-AR-Gαi3 pathway, normal cAMP/PKA regulation of ICa was recovered.

To further confirm this, we tested ISO effects on ICa in myocytes from WT and KO LV in the presence of specific β2-AR antagonist ICI118,551 (10 nM26). We found that the reduced ISO response in KO myocytes was reversed by β2-AR antagonist ICI118,551 (Figure 4C–E). In the presence of ICI118,551 (10nM), ISO-induced potentiating effect on ICa was reduced (from 101.61±4.64% to 68.83±6.97%, n=10, p<0.05) in WT myocytes but increased (from 72.32±8.42% to 95.83±8.91%, n=11, p<0.05) in KO myocytes. These results suggest that the net effect of β2-AR activation on ICa in KO myocytes is inhibitory due to the increased inhibitory G protein Gαi3. In WT myocytes, however, β2-AR activation plays a predominantly stimulatory role in ICa regulation.

To further elucidate the role of increased inhibitory G protein in reduced ISO response in KO ventricular myocytes, we used a Gi inhibitor pertussis toxin27;28 (PTX) (myocytes were incubated at 37°C with 1.5 mg/ml PTX for at least 3 h27). PTX treatment significantly increased the ISO (1μM) effect on ICa in KO but not in WT myocytes. As a result, ISO effect on ICa became similar in KO and WT myocytes (Figure 4F–H). These results suggest that the inhibitory G proteins play an important role in ICa regulation in KO myocytes but only a minor role in WT myocytes in response to β-adrenergic stimulation.

The β-AR expression is regulated at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Major transcriptional regulators of β-AR genes include glucocorticoid- and thyroid hormone-responsive elements (GREs and TREs, respectively), with glucocorticoids downregulating β1-ARs and upregulating β2-ARs29. Thyroid hormone can upregulate β1-AR gene transcriptional activity30 whereas chronic exposure to β-AR-agonist results in downregulation of β1-AR protein and mRNA31. In the present study, we observed an increase in β2-AR/Gi proteins in CaMKIIδ KO mice. However, whether these changes are specifically related to the reduction of CaMKII activity or adaptive is unknown.

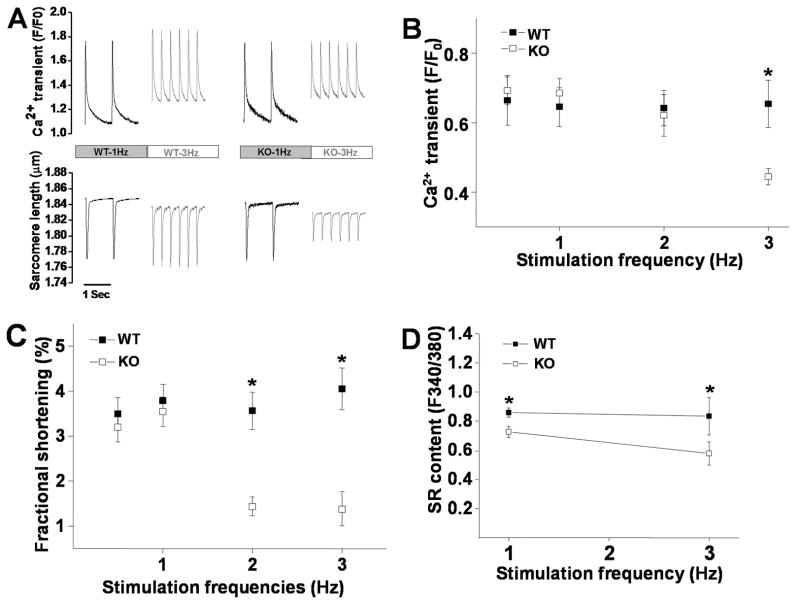

Altered Ca2+-transient, SR Ca2+content and sarcomere shortening in CaMKIIδ KO myocytes

In myocytes, Ca2+-transient and sarcomere shortening are triggered by Ca2+ influx through LTCCs and regulated by mechanisms involving a complex interplay of several Ca2+ regulatory proteins and pathways, among which, alterations of I Ca and CaMKII activity play a crucial role32;33. To understand the alteration of Ca2+ handling and E-C coupling in myocytes where CaMKII activity is largely and chronically inhibited, we recorded Ca2+-transient and sarcomere shortening in CaMKIIδ KO ventricular myocytes. Consistent with recent findings by Backs et al15, there is no difference in Ca2+-transient between WT and KO myocytes at 1Hz stimulation rate. However, at pacing rate of 3Hz, Ca2+-transient was significantly reduced in CaMKIIδ KO myocytes but unchanged in WT myocytes (Figure 5A&B). The reduced Ca2+-transient at fast pacing rate is likely associated with ICa alterations, i.e. accelerated current decay, slowed recovery from inactivation and reduced ICa facilitation, which lead to a reduction in Ca2+ influx at fast stimulation. In addition, the reduction of basal CaMKII activity may also affect SERCA function, leading to a reduced SR Ca2+ contents at fast pacing. Indeed, we observed significant reduction of SR Ca2+ content in KO myocytes at 1 and 3Hz with more prominent reduction at higher pacing rate, compared to WT myocytes (Figure 5D). This further contributes to the frequency-dependent reduction of Ca2+-transient in KO myocytes. Consistent with the lowered Ca2+-transient, sarcomere shortening was significantly reduced at fast pacing (Figure 5A&C).

Figure 5.

Panel A: Representative traces of Ca2+ transient and sarcomere shortening recorded at 1 and 3 Hz pacing rates in myocytes isolated from WT and KO LV. Panel B: Mean values of Ca2+ transient recorded in WT (n=15) and KO (n=13) ventricular myocytes at stimulation frequency of 0.5–3 Hz. Panel C: Mean values of sarcomere fractional shortening recorded in WT (n=15) and KO (n=13) ventricular myocytes at stimulation frequency of 0.5–3 Hz. Panel D: Mean values of SR Ca2+ contents recorded in WT (n=7) and KO (n=7) ventricular myocytes at stimulation frequency of 1 Hz and 3 Hz. Vertical bars represent S.E.M. * denotes p<0.05, compared to KO myocytes.

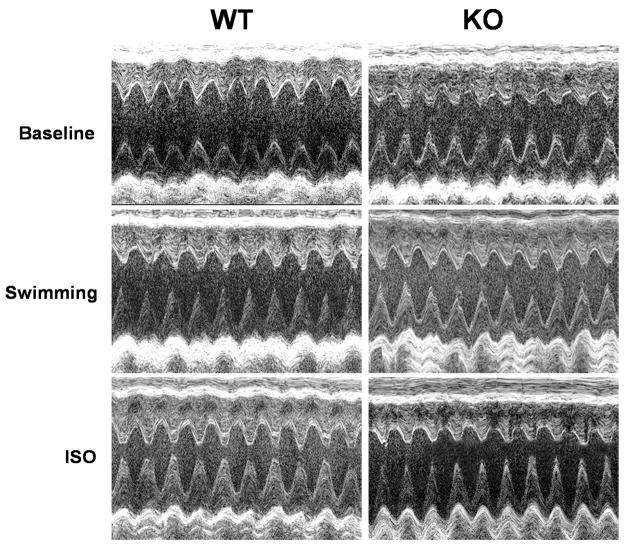

Altered in vivo heart function in CaMKIIδ KO mice

To test the in vivo cardiac effect of chronic CaMKII inhibition, we measured heart function in CaMKIIδ KO mice by echocardiography. Because anesthesia significantly affects cardiac function in mice34, echocardiography measurements were conducted in conscious mice using a high resolution murine echo machine (Visualsonics RMV707B with a 30 MHz transducer). Before collecting data for analysis, all mice were trained twice a day (morning and afternoon) by the operator with a 2 minute handling practice and echocardiography performance for 3 consecutive days. This practice performance largely reduced mouse stress during data acquisition. After 3 days training, heart function was then measured in the trained conscious mice.

Consistent with recent findings from a similar CaMKIIδ KO mouse model35, we found that KO mice have a basal (unstressed) heart rate similar to WT mice. However, KO mice showed an increased basal cardiac contractility with baseline LV fractional shortening (FS) of 55.77±0.74% for KO (n=38) vs. 50.87±0.57% for WT mice (n=40, p<0.01). In line with this, Backs et al. also showed a tendency of increased FS in this CaMKIIδ KO mouse model although the increase did not reach significance15. The increased basal ICa in KO ventricular myocytes certainly play a role herein but a more complicated in vivo cardiac regulation or altered contractile machinery may exist and contribute. To test the response of CaMKIIδ KO mice to increased workload, we measured LV function before and after 15 minutes of swimming in warm water (≈ 37°C). In order to enforce the mice to continuously swim, an appropriate weight was added to the mouse tail (a 2 gram clamp). We found that swimming significantly increased heart rate in WT mice. Surprisingly, heart rate was significantly reduced in KO mice by swimming (Table 2).

Table 2.

Echocardiography parameters recorded from conscious WT and CaMKIIδ KO mice

| Parameters | WT (n=40) | KO (n=38) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (beat/min) | 675±4 | 689±5 | NS |

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.10±0.02 | 3.04±0.04 | NS |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.53±0.02 | 1.35±0.03 | <0.01 |

| FS (%) | 50.87±0.57 | 55.77±0.74 | <0.01 |

| WT (n=37) | KO (n=30) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Baseline | ISO (1.5mg/kg) | Baseline | ISO (1.5mg/kg) |

| Heart rate (beat/min) | 675±4 | 689±4* | 687±5 | 614±10* |

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.10±0.03 | 3.00±0.03* | 3.06±0.05 | 2.98±0.06* |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.53±0.03 | 0.98±0.02* | 1.37±0.03# | 0.95±0.03* |

| FS (%) | 50.81±0.57 | 67.40±0.81* | 55.29±0.66# | 67.96±0.61* |

| Changes of FS (%) | 33.05±1.77 | 23.43±1.90# | ||

| WT (n=9) | KO (n=11) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Baseline | Swimming | Baseline | Swimming |

| Heart rate (beat/min) | 665±10 | 658±8 | 691±12 | 656±11* |

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.14±0.06 | 2.93±0.04* | 3.04±0.07 | 2.81±0.07* |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.58±0.05 | 1.03±0.02* | 1.29±0.07# | 0.97±0.05* |

| FS (%) | 49.59±1.21 | 64.86±0.82* | 57.66±1.79# | 65.88±1.37* |

| Change of FS (%) | 31.37±3.48 | 14.90±2.88# | ||

: p<0.05, compared with baseline;

: p<0.05, compared with WT; LVIDd and LVIDs: left ventricular internal dimensions at diastole and systole, respectively; FS: left ventricle fractional shortening; WT: wild type; KO: CaMKIIδ knockout.

Previous studies have demonstrated that CaMKII activity is required for the normal sinoatrial (SA) node function in rabbit heart, in which CaMKII inhibition by KN93 or AIP depressed the rate and amplitude of spontaneous action potentials (APs) in SA node cells in a dose-dependent manner. 10 μmol/L AIP or 3 μmol/L KN-93 completely arrested SA node cells21. More recently, Wu et al. demonstrated that adrenergic regulation of heart rate is likely a result of CaMKII-mediated regulation of SA nodal cell Ca2+ homeostasis. CaMKII inhibition has no effect on the ISO response in SA nodal cells when SR Ca2+ release is disabled36. We showed that chronic inhibition of CaMKII activity in CaMKIIδ KO mice reduced Ca2+ transient at fast-pacing. This may explain why swimming failed to increase heart rate in KO mice. The alteration of Ca2+ handling in CaMKIIδ KO mice limits the elevation of heart rate during workload. In addition to the reduced heart rate, swimming increased the LV fractional shortening (FS) by 31.37±3.48% in WT mice (n=9) but only 14.90±2.88% in KO mice (n=11, p<0.05). These results revealed a reduced cardiac reserve to excessive workload in CaMKIIδ KO mice. However, owing to the elevated basal contractility in CaMKIIδ KO mice, after swimming, the LV FS reached the same level in these two genotypes of mice.

To determine the effect of β-adrenergic activation on cardiac function, we tested the cardiac response to ISO injection at a dosage of 1.5 mg/Kg (I.P.). Similar to the results observed from swimming test, ISO (10 min after injection) increased LV contractility in CaMKIIδ KO mice less than in WT mice. The increase in FS was 23.43±1.90% for KO (n=37) vs. 33.05±1.77 % for WT (n=30, p<0.05), indicating a reduced sensitivity to β-adrenergic stimulation in KO mice. However, the absolute value of FS in the presence of ISO showed no difference between these two genotypes of mice (67.40±0.81% for WT vs. 67.96±0.61% for KO mice)(Table 2). Similar to the swimming test, ISO also induced a reduction of heart rate in KO mice. A representative short-axis two-dimensional image-guided M-mode views of the LV echocardiography were shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Representative images of short-axis two-dimensional M-mode echocardiography recorded from conscious WT and CaMKIIδ KO mice at baseline and after 15 minutes swimming or at 10 min after ISO injection, respectively.

DISCUSSION

ICa is the trigger for SR Ca2+ release, and itself provides ≈25% of the Ca2+ rise during systole. In addition, CaMKII-mediated ICa facilitation contributes to the increased contractile force at faster heart rate, which improves cardiac performance during exercise37.

There is growing evidence indicating a crucial role of CaMKII activation in the cardiac effects of acute and chronic β-adrenergic stimulation. Interestingly, our study demonstrated a resetting of ICa in ventricular myocytes with genetic CaMKII inhibition. Instead of an anticipated decrease, ICa density was significantly increased in CaMKIIδ KO LV. The increase in ICa density is associated with the upregulation of LTCC Cav1.2. This increase in channel expression may compensate for the reduced CaMKII-dependent LTCC phosphorylation during the long-term CaMKII inhibition.

Several recent studies reported changes in ICa in ventricular myocytes from mouse models with genetic CaMKII inhibition, e.g. the mouse model with transgenic expression of a highly specific CaMKII inhibitory peptide (AC3-I)24 and transgenic mice that express four concatenated repeats of the CaMKII inhibitory peptide AIP selectively in the SR membrane38. In these studies24;38, ICa facilitation has been totally abolished, supporting that CaMKII activation is the main molecular basis for CDF and implicating localized CaMKII activity in cardiac ICa facilitation. Similar to our findings, Zhang et al. reported an increase in ICa in AC3-I mouse LV and suggested that the increase in ICa is associated with an increased PKA activity24. However, neither total PKA protein expression nor local PKA activity (indicated by PKA-specific PLB phosphorylation at Ser16) has changed in our CaMKIIδ KO mice. In addition, we showed that saturation of PKA activation by internal application of 100 μM 8-bromo-cAMP did not change the difference in ICa between WT and KO ventricular myocytes. These results ruled out the possibility that the ICa difference between WT and KO ventricular myocytes is a result of the possible increase in bulk or local PKA activity in KO myocytes. Instead, our results indicate that the increase in ICa density in CaMKIIδ KO mice is a result of increased Cav1.2 channel expression. In fact, in addition to the increased ICa density, the ICa decay was significantly accelerated in KO myocytes, which is consistent with the reduced channel phosphorylation (both PKA and CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of LTCC slows ICa decay). The inconsistency with the results from AC3-I mouse model is likely due to the different extent of CaMKII inhibition between these two genetic models. In the AC3-I mice, cardiac CaMKII activity was totally ablated. It is reasonable that the PKA pathway will take over the role of CaMKII in regulation of ICa under the condition of CaMKII ablation. However, in our CaMKIIδ KO mouse LV, CaMKII activity is inhibited by ≈ 61% due to the unmodified CaMKIIγ isoforms. This largely but incompletely inhibited CaMKII activity likely mimics clinical therapeutic strategy. Thus, data from our CaMKIIδ KO mouse model are more clinically relevant.

Recent studies suggest that CaMKII may play a role in regulating Cav1.2 channel expression. This is based on the evidence that CaMKII phosphorylates nuclear factor-kappaB (NFkB) component p65 and causes its nuclear translocation39 and consequent suppression of Cav1.2 channel expression19. In our CaMKIIδ KO ventricular myocytes, p65 nuclear translocation is significantly reduced. As a result, NFkB-dependent inhibition of Cav1.2 expression is released. The release of this inhibition may explain the increase in Cav1.2 expression observed in KO LV.

It has been shown that acute inhibition of CaMKII in ventricular myocytes significantly reduced ICa, SR Ca2+ contents and transients. As a result, steady-state twitch is reduced40. In our CaMKIIδ KO myocytes, the increased ICa is likely a compensatory mechanism for triggering a larger SR Ca2+ release in order to maintain an appropriate Ca2+ transient and contractility in KO myocytes. However, consistent with the reduced CaMKII activity, ICa facilitation was significantly reduced or abolished in CaMKIIδ KO myocytes. In a small portion of ventricular myocytes (≈ 24%) from KO LV, a negative ICa staircase was observed (Figure 1G). The reason for this is unclear. One possibility is that the proportional expression of CaMKII isoforms (δ and γ) in heart may vary from cell to cell, and thus knockout of CaMKIIδ may reduce intracellular CaMKII activity more in some cells but less in others. Nevertheless, the reduced ICa facilitation, in combination with the accelerated ICa current decay and slowed recovery from inactivation, limits Ca2+ influx at fast heart rate. As a result, the Ca2+-transient and sarcomere shortening were significantly reduced at fast pacing rate in CaMKIIδ KO myocytes (Figure 5B&C).

PKA is the primary regulator of ICa in normal heart. It is known that both β1-AR and β2-AR couple to Gs proteins to activate adenylate cyclase (AC), which mediates the conversion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) into cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). This leads to the activation of PKA, which then phosphorylates several substrates, including LTCCs. Different from β1-AR, in addition to the Gs proteins, β2-AR also couples to Gi proteins, which counteract the Gs coupled activation of AC, resulting in a reduction of cAMP level and thus producing an inhibitory effect41. In this study, we found that in CaMKIIδ KO LV, there was a reduction in β1-AR expression and a dramatic increase in β2-AR and the inhibitory G protein Gαi3 expression. These changes significantly decreased ICa response to β-adrenergic activation.

Although echocardiography experiments performed in the conscious mice showed an increased basal LV contractility in CaMKIIδ KO mice, these mice have a reduced cardiac reserve to excessive workload and β-adrenergic activation. The reduced response to workload and β-adrenergic activation is consistent with the reduced β1-AR and the increase in β2-AR and Gi protein expression. Although the FS was increased to a similar level between WT and KO mice in the presence of ISO or workload, the increase in cardiac output was significantly reduced in KO mice (compared to WT) due to the slowed heart rate under these stressed conditions, suggesting a reduction of cardiac response to stress.

Perspective

Recent studies highlighted the important roles of CaMKII in the regulation of Ca2+ handling and E-C coupling42. In this study, ICa channel upregulation in CaMKIIδ KO myocytes is likely an important mechanism to offset the expected decrease in Ca2+ transient and contractility in response to chronic CaMKII inhibition. The increased β2-AR and Gi protein expression and reduced heart rate in response to β-adrenergic activation and workload significantly reduced cardiac reserve to stress. These results implicate physiologic CaMKII activity in heart in maintaining normal Ca2+ transient, E-C coupling and cardiac function in the basal and stressed conditions. However, as a limitation of this study, the role of physiologic CaMKII activity in diseased conditions has not been investigated. In structural heart disease, e.g. heart failure, the excessive adrenergic activity is needed to maintain pump function. With overtime, this causes significant changes in adrenergic and CaMKII signaling with β-adrenergic signaling downregulated and CaMKII signaling enhanced13. Thus, a physiologic CaMKII activity may be more important in the diseased heart.

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

CaMKII is an important regulator of Ca2+ handling and excitation-contraction coupling (E-C coupling) in ventricular myocytes via modulating L-type calcium current (ICa) and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) function.

In common cardiomyopathies, CaMKII activity is excessively increased. Inhibition of CaMKII reduces ICa and SR Ca2+ leak and protects against the development of structural heart disease and ventricular arrhythmias.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Physiologic CaMKII activity is important in maintaining normal heart rate adaptation to excessive workload and β-adrenergic stimulation.

Chronic inhibition of CaMKII causes an increase in ICa density but significantly decreased ICa response to β-adrenergic activation, leading to a potentiated basal ventricular contractility but a reduction of cardiac reserve to workload and β-adrenergic stimulation.

Summary.

Although excessive CaMKII activity is linked to cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias, physiologic CaMKII activity may be important for maintaining normal cardiac function and heart rhythm. For the first time, we found that chronic inhibition of CaMKII (CaMKIIδ knockout) resets ICa by increasing calcium channel Cav1.2 expression and reducing nuclear factor-kappaB (NFkB) component p65 nuclear translocation. Owing to the reduction of β1-adrenergic receptor expression and a dramatic increase in β2 and the inhibitory G protein expression, ICa response to β-adrenergic activation was reduced. Ca2+ transient and sarcomere shortening in CaMKIIδ knockout ventricular myocytes were unchanged at 1Hz but reduced at 3Hz stimulation. Surprisingly, CaMKIIδ knockout mice showed a reduced heart rate in response to workload or β-adrenergic stimulation. These alterations potentiate basal ventricular contractility but significantly reduce cardiac reserve to excessive workload and β-adrenergic stimulation, implicating physiologic CaMKII activity in maintaining normal ICa, Ca2+ handling, excitation-contraction coupling and the in vivoheart function in response to cardiac stress. In CaMKIIδ knockout mouse heart, CaMKII activity is reduced by ≈ 62% due to the unmodified CaMKIIγ isoforms. This largely but incompletely inhibited CaMKII activity likely mimics clinical therapeutic strategy. Thus, results from this study would have significant clinical relevance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants awarded to Dr. Yanggan Wang from NIH (R21HL-088168, R01HL-083271), American Health Assistant Foundation (H2007-019), Emory University (seed grant 280263), and the support from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

Footnotes

Disclosures

There is no conflict to disclose.

REFERENCE

- 1.Tobimatsu T, Fujisawa H. Tissue-specific expression of four types of rat calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II mRNAs. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17907–17912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baltas LG, Karczewski P, Krause EG. The cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum phospholamban kinase is a distinct delta-CaM kinase isozyme. FEBS Lett. 1995;373:71–75. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00981-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer HA, Benscoter HA, Schworer CM. Novel Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gamma-subunit variants expressed in vascular smooth muscle, brain, and cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9393–9400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoch B, Haase H, Schulze W, Hagemann D, Morano I, Krause EG, Karczewski P. Differentiation-dependent expression of cardiac delta-CaMKII isoforms. J Cell Biochem. 1998;68:259–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase and L-type calcium channels; a recipe for arrhythmias? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Tandan S, Cheng J, Yang C, Nguyen L, Sugianto J, Johnstone JL, Sun Y, Hill JA. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-dependent remodeling of Ca2+ current in pressure overload heart failure. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25524–25532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803043200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez-Reyes E, Schneider T. Molecular biology of calcium channels. Kidney Int. 1995;48:1111–1124. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Waard M, Gurnett CA, Campbell KP. Structural and functional diversity of voltage-activated calcium channels. Ion Channels. 1996;4:41–87. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1775-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Coppenolle F, Ahidouch A, Guilbault P, Ouadid H. Regulation of endogenous Ca2+ channels by cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases in Pleurodeles oocytes. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;168:155–161. doi: 10.1023/a:1006819507785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alden KJ, Goldspink PH, Ruch SW, Buttrick PM, Garcia J. Enhancement of L-type Ca(2+) current from neonatal mouse ventricular myocytes by constitutively active PKC-betaII. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C768–C774. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00494.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tandan S, Wang Y, Wang TT, Jiang N, Hall DD, Hell JW, Luo X, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Physical and functional interaction between calcineurin and the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel. Circ Res. 2009;105:51–60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dzhura I, Wu Y, Colbran RJ, Corbin JD, Balser JR, Anderson ME. Cytoskeletal disrupting agents prevent calmodulin kinase, IQ domain and voltage-dependent facilitation of L-type Ca2+ channels. J Physiol. 2002;545:399–406. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Wang W, Zhu W, Wang S, Yang D, Crow MT, Xiao RP, Cheng H. Sustained beta1-adrenergic stimulation modulates cardiac contractility by Ca2+/calmodulin kinase signaling pathway. Circ Res. 2004;95:798–806. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145361.50017.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verrier RL, Antzelevitch C. Autonomic aspects of arrhythmogenesis: the enduring and the new. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:2–11. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Backs J, Backs T, Neef S, Kreusser MM, Lehmann LH, Patrick DM, Grueter CE, Qi X, Richardson JA, Hill JA, Katus HA, Bassel-Duby R, Maier LS, Olson EN. The delta isoform of CaM kinase II is required for pathological cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling after pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2342–2347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813013106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan W, Bers DM. Ca-dependent facilitation of cardiac Ca current is due to Ca-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H982–H993. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.3.H982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson ME, Braun AP, Schulman H, Premack BA. Multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase mediates Ca(2+)-induced enhancement of the L-type Ca2+ current in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1994;75:854–861. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.5.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishiguro K, Green T, Rapley J, Wachtel H, Giallourakis C, Landry A, Cao Z, Lu N, Takafumi A, Goto H, Daly MJ, Xavier RJ. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II is a modulator of CARMA1-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5497–5508. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02469-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi XZ, Pazdrak K, Saada N, Dai B, Palade P, Sarna SK. Negative transcriptional regulation of human colonic smooth muscle Cav1.2 channels by p50 and p65 subunits of nuclear factor-kappaB. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1518–1532. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo J, Duff HJ. Calmodulin kinase II accelerates L-type Ca2+ current recovery from inactivation and compensates for the direct inhibitory effect of [Ca2+]i in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2006;574:509–518. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinogradova TM, Zhou YY, Bogdanov KY, Yang D, Kuschel M, Cheng H, Xiao RP. Sinoatrial node pacemaker activity requires Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activation. Circ Res. 2000;87:760–767. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.9.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsien RW, Bean BP, Hess P, Lansman JB, Nilius B, Nowycky MC. Mechanisms of calcium channel modulation by B-adrenergic agents and dihydropyridine Ca agonists. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1986;18:691–710. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(86)80941-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiaho F, Nargeot J, Richard S. Voltage-dependent regulation of L-type cardiac Ca channels by isoproterenol. Pflugers Arch. 1991;419:596–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00370301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang R, Khoo MS, Wu Y, Yang Y, Grueter CE, Ni G, Price EE, Jr, Thiel W, Guatimosim S, Song LS, Madu EC, Shah AN, Vishnivetskaya TA, Atkinson JB, Gurevich VV, Salama G, Lederer WJ, Colbran RJ, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition protects against structural heart disease. Nat Med. 2005;11:409–417. doi: 10.1038/nm1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maltsev VA, Ji GJ, Wobus AM, Fleischmann BK, Hescheler J. Establishment of beta-adrenergic modulation of L-type Ca2+ current in the early stages of cardiomyocyte development. Circulation Research. 1999;84:136–145. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cerbai E, Guerra L, Varani K, Barbieri M, Borea PA, Mugelli A. Beta-adrenoceptor subtypes in young and old rat ventricular myocytes: a combined patch-clamp and binding study. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:1835–1842. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao RP, Ji X, Lakatta EG. Functional coupling of the beta 2-adrenoceptor to a pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein in cardiac myocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:322–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou YY, Cheng H, Song LS, Wang D, Lakatta EG, Xiao RP. Spontaneous beta(2)-adrenergic signaling fails to modulate L-type Ca(2+) current in mouse ventricular myocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:485–493. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiely J, Hadcock JR, Bahouth SW, Malbon CC. Glucocorticoids down-regulate beta 1-adrenergic-receptor expression by suppressing transcription of the receptor gene. Biochem J. 1994;302 (Pt 2):397–403. doi: 10.1042/bj3020397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNab TC, Tseng YT, Stabila JP, McGonnigal BG, Padbury JF. Liganded and unliganded steroid receptor modulation of beta 1 adrenergic receptor gene transcription. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:575–580. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200111000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bristow MR, Minobe WA, Raynolds MV, Port JD, Rasmussen R, Ray PE, Feldman AM. Reduced beta 1 receptor messenger RNA abundance in the failing human heart. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2737–2745. doi: 10.1172/JCI116891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bers DM, Guo T. Calcium signaling in cardiac ventricular myocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1047:86–98. doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roth DM, Swaney JS, Dalton ND, Gilpin EA, Ross J., Jr Impact of anesthesia on cardiac function during echocardiography in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2134–H2140. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00845.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ling H, Zhang T, Pereira L, Means CK, Cheng H, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Peterson KL, Chen J, Bers D, Heller BJ. Requirement for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II in the transition from pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1230–1240. doi: 10.1172/JCI38022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Y, Gao Z, Chen B, Koval OM, Singh MV, Guan X, Hund TJ, Kutschke W, Sarma S, Grumbach IM, Wehrens XH, Mohler PJ, Song LS, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase II is required for fight or flight sinoatrial node physiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5972–5977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806422106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ross J, Jr, Miura T, Kambayashi M, Eising GP, Ryu KH. Adrenergic control of the force-frequency relation. Circulation. 1995;92:2327–2332. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.8.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Picht E, DeSantiago J, Huke S, Kaetzel MA, Dedman JR, Bers DM. CaMKII inhibition targeted to the sarcoplasmic reticulum inhibits frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation and Ca2+ current facilitation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meffert MK, Chang JM, Wiltgen BJ, Fanselow MS, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B functions in synaptic signaling and behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1072–1078. doi: 10.1038/nn1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li L, Satoh H, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. The effect of Ca(2+)-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II on cardiac excitation-contraction coupling in ferret ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1997;501 (Pt 1):17–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.017bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiao RP. Cell logic for dual coupling of a single class of receptors to G(s) and G(i) proteins. Circ Res. 2000;87:635–637. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maier LS, Bers DM. Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) in excitation-contraction coupling in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.