Abstract

To characterize the role of nitric oxide (NO) in the tolerance of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) to heat shock (HS), we investigated the effects of heat on three types of Arabidopsis seedlings: wild type, noa1(rif1) (for nitric oxide associated1/resistant to inhibition by fosmidomycin1) and nia1nia2 (for nitrate reductase [NR]-defective double mutant), which both exhibit reduced endogenous NO levels, and a rescued line of noa1(rif1). After HS treatment, the survival ratios of the mutant seedlings were lower than those of wild type; however, they were partially restored in the rescued line. Treatment of the seedlings with sodium nitroprusside or S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine revealed that internal NO affects heat sensitivity in a concentration-dependent manner. Calmodulin 3 (CaM3) is a key component of HS signaling in Arabidopsis. Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis after HS treatment revealed that the AtCaM3 mRNA level was regulated by the internal NO level. Sodium nitroprusside enhanced the survival of the wild-type and noa1(rif1) seedlings; however, no obvious effects were observed for cam3 single or cam3noa1(rif1) double mutant seedlings, suggesting that AtCaM3 is involved in NO signal transduction as a downstream factor. This point was verified by phenotypic analysis and thermotolerance testing using seedlings of three AtCaM3-overexpressing transgenic lines in an noa1(rif1) background. Electrophoretic mobility-shift and western-blot analyses demonstrated that after HS treatment, NO stimulated the DNA-binding activity of HS transcription factors and the accumulation of heat shock protein 18.2 (HSP18.2) through AtCaM3. These data indicate that NO functions in signaling and acts upstream of AtCaM3 in thermotolerance, which is dependent on increased HS transcription factor DNA-binding activity and HSP accumulation.

When plants are exposed to high temperatures, growth and development may be retarded because of drought and oxidative damage, thereby leading to diminished fertility (Wang et al., 2003; Mittler, 2006). As a countermeasure, a series of protective reactions are triggered, the most common being heat shock (HS) protein (HSP) synthesis. In eukaryotes, HSP expression is mediated by HS transcription factors (HSFs) through their binding to HS promoter elements (HSEs) in the promoter regions of HSP genes (Nover et al., 2001; Baniwal et al., 2004; Charng et al., 2007). The regulation of these events is central to the study of thermotolerance.

Currently, calmodulin (CaM), a ubiquitous second messenger, is believed to be the most important multifunctional sensor protein in plants. CaM induces defensive reactions, the function and structure of which are very similar to those seen in animals and yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). However, CaM exists as several isoforms, one or several of which rely on exogenous stimulation to combine with their particular target peptide. Thereafter, a series of reactions are initiated, leading to the induction of a cellular physiological response. For example, CaM is suggested to be a signaling component required for the induction of cold-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Tahtiharju et al., 1997). Among the isoforms of CaM, CaM3 is the most responsive to cold (Townley and Knight, 2000). CaM has also been shown to be up-regulated by heat stress (Gong et al., 1997a, 1997b). Our group reported that in wheat (Triticum aestivum), CaM was directly involved in HS signaling via the accumulation of HSPs (Liu et al., 2003), while in maize (Zea mays) seedlings, CaM was suggested to be involved in HSP gene expression based on its ability to regulate the DNA-binding activity of HSFs (Li et al., 2004). Among the nine members of the AtCaM gene family in Arabidopsis, only the expression of AtCaM3 was up-regulated in response to heat. Furthermore, analyses of the temporal changes in expression of AtCaM3 and AtHSP18.2 indicated that the induction of AtCaM3 expression occurred earlier than that of AtHSP18.2 (Liu et al., 2005). Recently, we utilized several T-DNA knockout mutants and transgenic plants to produce direct molecular and genetic evidence, showing that endogenous AtCaM3 is a key component of HS signaling (Zhang et al., 2009b). Though CaM plays a crucial role in thermotolerance, the precise mechanism for the induction of its functions remains elusive.

In plants, nitric oxide (NO) functions as an important messenger in multiple biological processes and is induced by multiple biotic and abiotic stresses to mediate resistance responses (Delledonne et al., 1998; Mata and Lamattina, 2001; Zhao et al., 2004; Foresi et al., 2007; Zhang and Zhao, 2008; Zhao et al., 2009). It also participates in the HS response. NO is up-regulated by high temperatures in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; Gould et al., 2003) and Symbiodinium microadriaticum (Bouchard and Yamasaki, 2008). The exogenous application of an NO donor effectively protects rice (Oryza sativa) seedlings and reed (Phragmites communis) calluses, from heat-induced oxidative stress, indicating that NO activates reactive oxygen species-scavenging enzymes during heat stress and thus confers thermotolerance (Uchida et al., 2002; Song et al., 2006). However, it remains unclear how NO protects plants against heat stress in vivo.

CaM and NO as signaling molecules play important roles in the plant response to external factors. Many studies in animals and yeast have shown significant overlap in their individual pathways (Su et al., 1995; Newman et al., 2004; Roman and Masters, 2006); however, only a few studies have been undertaken in plants. A point mutation in a plant CaM is reportedly responsible for the inhibition of NO synthase (Kondo et al., 1999). Cross talk is believed to exist between Ca2+-CaM and NO in abscisic acid signaling in the leaves of maize plants (Sang et al., 2008). Recently our group found that NO was involved in the regulation of extracellular CaM induction during stomatal closure in Arabidopsis (Li et al., 2009). These studies suggest an intimate connection between CaM and NO under HS conditions.

AtNOS1 encodes a protein similar to one involved in NO synthesis in the snail Helix pomatia. nos1, a homozygous mutant line with a T-DNA insertion in the first exon of NOS1, has a reduced level of NOS activity in vivo and a lower NO content than wild-type plants (Guo et al., 2003). Critical questions have been raised about the role of AtNOS1 in NO biosynthesis, leading to the suggestion that NOS1 is renamed to NO associated1 (NOA1). Flores-Pérez et al. (2008) demonstrated that the accumulation of plastid-targeted enzymes of the methylerythritol pathway conferring resistance to fosmidomycin in an isolated noa1 allele named rif1 (for resistant to inhibition by fosmidomycin1) is insensitive to NO donor, thus suggesting that the loss of NOA1(RIF1) function affects physiological processes unrelated to NO synthesis. Interestingly, NOA1(RIF1) contains a GTP-binding domain and has been suggested to be a member of the circularly permuted GTPase family of RNA/ribosome-binding proteins involved in ribosome assembly (Flores-Pérez et al., 2008; Moreau et al., 2008). Though it is not certain how NOA1(RIF1) indirectly affects NO accumulation, noa1(rif1) with reduced endogenous NO level is still a convenient tool for studies of NO function (Guo and Crawford, 2005; Zhao et al., 2007; Asai et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009a; Zhao et al., 2009).

In this study, we used noa1(rif1) as a loss-of-function mutant to examine the relationship between NO and CaM under HS conditions, and we investigated the role of NO as a second messenger in the induction of adaptive responses. The results presented demonstrate the involvement of NO in thermotolerance, by activating of AtCaM3 to stimulate its downstream HSF DNA-binding activity and HSP gene expression.

RESULTS

Effects of HS Treatment on Survival and Endogenous NO Production in Wild-Type and noa1(rif1) Seedlings

NO accumulates in plants in response to a variety of environmental stresses, including HS (Gould et al., 2003; Bouchard and Yamasaki, 2008). Survival ratios reflect cellular homeostasis in the face of oxidative damage induced by heat stress (Mittler, 2006). To examine the relationship between NO and thermotolerance in Arabidopsis, we first compared the endogenous NO levels and survival ratios in wild-type and noa1(rif1) mutant seedlings.

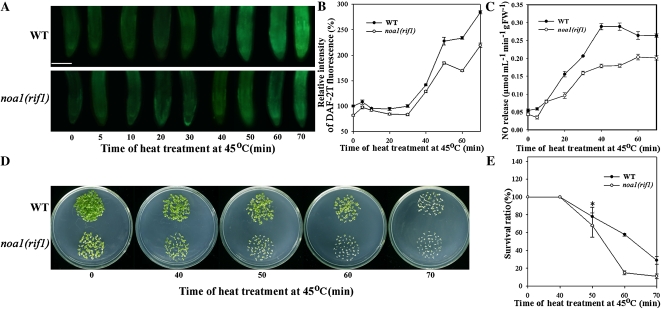

Diaminofluorescein diacetate (DAF-2T) is the fluorescence triazole product of the reaction of DAF-2 with N2O3 (Arita et al., 2006; Tun et al., 2006). Its fluorescence analysis showed that under normal growth conditions (22°C), the NO level in wild-type seedlings was 35% higher than that in noa1(rif1) seedlings. After HS treatment at 45°C, the NO level varied slightly; thereafter, beginning at 30 min, the level of NO increased rapidly. After 70-min HS treatment, NO increased by 190% and 223% in the wild-type and noa1(rif1) mutant seedlings, respectively; the level of NO was consistently lower in the mutant seedlings (Fig. 1, A and B). Hemoglobin analysis showed the similar NO changing trends under HS treatment (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Effects of HS on the survival and endogenous NO levels in wild-type and noa1(rif1) mutant seedlings. A, Six-day-old wild-type and noa1(rif1) mutant seedlings grown at 22°C were exposed to 45°C for 0 to 70 min, then examined for NO by fluorescence microscopy in roots stained with DAF-2DA. Bar = 100 μm. B, Relative DAF-2DA fluorescence densities in the roots. The data are the mean ± se of measurements taken from at least 10 roots for each treatment. C, NO productions were examined by hemoglobin analysis in the roots. The data are the mean ± se of at least four independent experiments. FW, Fresh weight. D, The seedlings grown at 22°C were exposed to 45°C for 0 to 70 min, then returned to 22°C and photographed 6 d later. E, Survival ratios of the seedlings. The data are the mean ± se of at least four independent experiments, with 50 seedlings per experiment. Bar with asterisk indicates P < 0.05. WT, Wild type. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Next, 6-d-old seedlings were subjected to HS treatment at 45°C followed by 6 d of recovery at 22°C, after which the survival ratio was determined. Under normal growth conditions, the noa1(rif1) seedlings exhibited chlorosis and were extremely small in size compared to the wild-type seedlings, consistent with the findings of Guo et al. (2003). The survival ratios between the wild-type and noa1(rif1) seedlings were different in response to heat stress. After 6 d of recovery, 0 to 40 min of treatment at 45°C had no influence on the survival ratios of either the wild-type or noa1(rif1) seedlings. As the duration of the HS period was increased, impaired tolerance was detected in the mutant. The maximum difference was noted after 60-min HS, with survival ratios of 58% and 12% for the wild-type and mutant seedlings, respectively (Fig. 1, D and E). Based on these results, 60 min was used as the length of the HS period in our subsequent experiments. Our data reveal that in response to HS treatment, the wild-type plants maintained a higher level of NO and a higher survival ratio than the noa1(rif1) mutant plants. The nia1nia2 mutant plants (nitrate reductase-defective double mutant; Wilkinson and Crawford, 1993), defective in NO production (Zhao et al., 2009), also showed lower survival ratio and NO level compared to wild-type plants under heat stress (Supplemental Fig. S1). It is therefore reasonable to suspect a link between the function of NO and thermotolerance.

The Relationship between NO and Thermotolerance

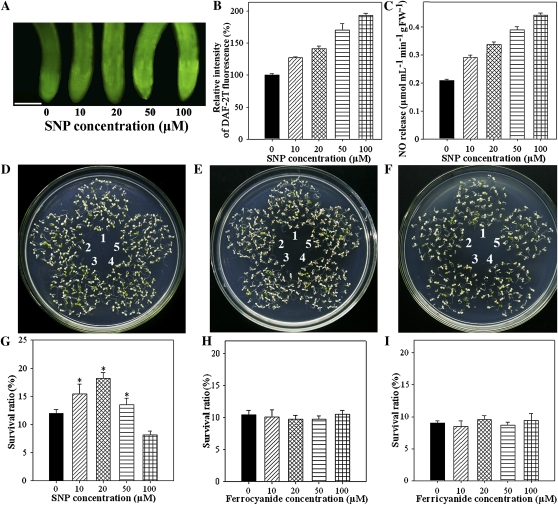

To examine whether the suppression of the NO level in the noa1(rif1) seedlings was responsible for their impaired thermotolerance, we pretreated noa1(rif1) mutant seedlings with sodium nitroprusside (SNP), an NO donor. DAF-2T fluorescence analysis showed that the exogenous application of SNP gradually increased the NO level in the roots in a concentration-dependent manner. At concentrations below 100 μm SNP, the internal NO level reached its peak value (Fig. 2, A–C). The survival ratio changed synchronously depending on the SNP concentration. Survival initially increased, reaching its maximum at 20 μm (but still lower than that of wild type; Fig. 1), then gradually decreased, becoming even lower than the control value at 100 μm (Fig. 2, D and G). SNP not only releases NO but also releases cyanide (CN), which has been shown to elicit some of the same responses as NO (Boullerne et al., 1999). Therefore, to show that NO, and not CN, had mediated these responses, we applied potassium ferricyanide and potassium ferrocyanide as controls and found that they did not influence the survival ratios of the plants under HS conditions (Fig. 2, E, F, H, and I). Based on these results, 20 μm SNP was used to improve thermotolerance in our subsequent experiments. Pretreatment of S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP), another NO donor, influenced internal NO levels and survival ratios of the seedlings in a similar manner as SNP (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Effect of NO on thermotolerance in noa1(rif1) seedlings. A, Six-day-old noa1(rif1) mutant seedlings grown at 22°C were pretreated with 1 mL of 0, 10, 20, 50, or 100 μm SNP for 24 h, then exposed to 45°C for 60 min. The NO levels were examined by fluorescence microscopy in roots stained with DAF-2DA. Bar = 100 μm. B, Relative DAF-2DA fluorescence densities in the roots. The data are the mean ± se of measurements taken from at least 10 roots for each treatment. C, NO productions were examined by hemoglobin analysis in the roots. The data are the mean ± se of at least four independent experiments. FW, Fresh weight. D to F, One milliliter of a different concentration (1, 0 μm; 2, 10 μm; 3, 20 μm; 4, 50 μm; or 5, 100 μm) of SNP as an NO donor (D), or of potassium ferrocyanide (Fe[II]CN) (E) and potassium ferricyanide (Fe[III]CN) (F) as SNP controls, was added to the surface of leaves. After 24 h, the seedlings were exposed to 45°C for 60 min, then returned to 22°C and photographed 6 d later. G to I, Survival ratios of the seedlings after HS treatment. The data are the mean ± se of at least four independent experiments, with 50 seedlings per experiment. Bar with asterisk indicates P < 0.05. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

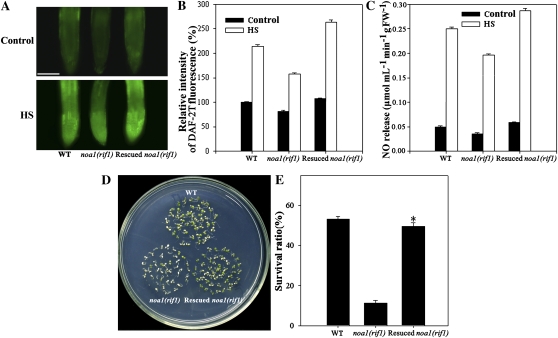

Effects of HS Treatment on Survival and Endogenous NO Production in Rescued noa1(rif1) Line

To confirm previous observations of the effect of NO on thermotolerance, the response of a rescued noa1(rif1) line (Li et al. 2009) to heat stress was compared with wild-type and noa1(rif1) mutant seedlings. DAF-2T fluorescence and hemoglobin analyses both showed that under normal and HS conditions, the endogenous NO levels were higher in the rescued line than in the noa1(rif1) mutant and wild-type plants (Fig. 3, A–C). The survival ratio was almost fully rescued, but remained 8% lower than that of wild type (Fig. 3, D and E). These data, combined with the results shown in Figures 1 and 2, demonstrate that the increased endogenous NO level is involved in plant survival following heat treatment.

Figure 3.

Effects of HS on the survival and endogenous NO levels in rescued noa1(rif1) line. A, Six-day-old seedlings grown at 22°C were exposed to 45°C (HS) or maintained at 22°C (Control) for 60 min. The NO levels were then detected by fluorescence microscopy in wild-type, noa1(rif1), and rescued noa1(rif1) roots stained with DAF-2DA. Bar = 100 μm. B, Relative DAF-2DA fluorescence densities in the roots. The data are the mean ± se of measurements taken from at least 10 roots for each treatment. C, NO productions were examined by hemoglobin analysis in the roots. The data are the mean ± se of at least four independent experiments. FW, Fresh weight. D, The seedlings were exposed to 45°C for 60 min, then returned to 22°C and photographed 6 d later. E, Survival ratios of the seedlings after HS treatment. The data are the mean ± se from at least four independent experiments, with 50 seedlings per experiment. Bar with asterisk indicates P < 0.05 versus wild-type seedlings. WT, Wild type. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Effect of NO on Thermotolerance in cam3 Mutant Seedlings

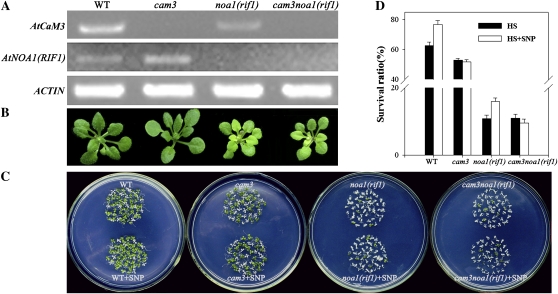

We previously reported that in Arabidopsis, CaM3 was heat induced and involved in HS signal transduction (Liu et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2009b). To gain insight into NO signal transduction, the interaction between NO and AtCaM3 was examined under heat treatment using cam3noa1(rif1) double mutant seedlings. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis indicated a deficiency in both NOA1(RIF1) and AtCaM3 transcription (Fig. 4A). The phenotype of the double mutant was similar to that of the noa1(rif1) mutant under normal conditions (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Survival status of the cam3noa1(rif1) double mutant. A, RT-PCR analysis of ectogenous NOA1(RIF1) and AtCaM3 transcripts in wild-type, cam3, noa1(rif1), and cam3noa1(rif1) double mutant seedlings. Actin was used as an internal control. B, The phenotypes of 25-d-old seedlings grown at 22°C under normal conditions. C, Six-day-old seedlings were pretreated with 1 mL of 0 or 20 μm SNP for 24 h, exposed to 45°C for 60 min, then returned to 22°C and photographed 6 d later. D, Survival ratios of the seedlings after HS treatment. The data are the mean ± se of at least four independent experiments, with 50 seedlings per experiment. WT, Wild type. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

We next compared the effects of NO on the survival of wild-type, noa1(rif1), cam3, and cam3noa1(rif1) seedlings. No obvious phenotypic difference was observed between the wild-type and cam3 seedlings under normal conditions (Fig. 4B). After 6 d of recovery, the survival ratio of the wild-type seedlings was 21% higher than that of the cam3 mutant seedlings, indicating heat resistance. This is consistent with our previous data (Zhang et al., 2009b). The foliar application of SNP at 20 μm increased the survival ratio of the wild-type seedlings, but had no effect on the cam3 mutant plants. No obvious phenotypic differences existed between the noa1(rif1) single and cam3noa1(rif1) double mutants (Fig. 4B). In addition, there was no obvious difference in their survival ratios under heat stress; however, 20 μm SNP increased the survival ratio of the noa1(rif1) seedlings by 50%, whereas no clear effect on the cam3noa1(rif1) seedlings was observed (Fig. 4, C and D).

Analysis of the Effects of NO on AtCaM3 Transcription by Real-Time PCR

To further examine the interaction between NO and AtCaM3 under HS conditions, we examined the effect of NO on AtCaM3 expression by real-time quantitative RT-PCR.

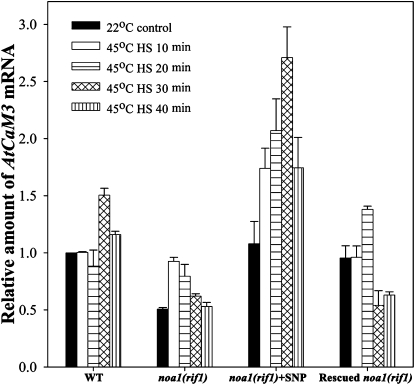

Before HS treatment, the AtCaM3 mRNA level in the noa1(rif1) mutant seedlings was 45% lower than that in wild type, and was partially restored in the rescued noa1(rif1) line. However, 20 μm SNP stimulated AtCaM3 mRNA expression in the noa1(rif1) mutant to a level that was slightly higher than that in wild type (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Analysis of the effects of NO on AtCaM3 mRNA expression by real-time PCR. Ten-day-old wild-type (WT), noa1(rif1), and rescued noa1(rif1) seedlings were pretreated with 1 mL of 0 or 20 μm SNP at 22°C for 24 h, exposed to 45°C for 0 to 40 min, then used for analysis of AtCaM3 mRNA expression. The data are the mean ± se of at least four independent experiments.

Upon HS treatment, the AtCaM3 mRNA levels initially increased then gradually decreased over time in all cases; however, the peak time and value were variable. In the wild-type seedlings, the peak occurred at 30 min, and was 50% higher than that in the controls. In the mutant, the peak value occurred at 10 min, and was increased by 95% but was still lower than the normal level in wild type. At 20 μm SNP, a dramatic rise in the AtCaM3 mRNA level was detected, with recovery of the peak time and stimulation of the peak value to 185% of that in wild type. In the rescued noa1(rif1) line, the peak time and value were restored to 20 min and near the wild-type level, respectively (Fig. 5).

The Overexpression of AtCaM3 in an noa1(rif1) Background Improves Thermotolerance

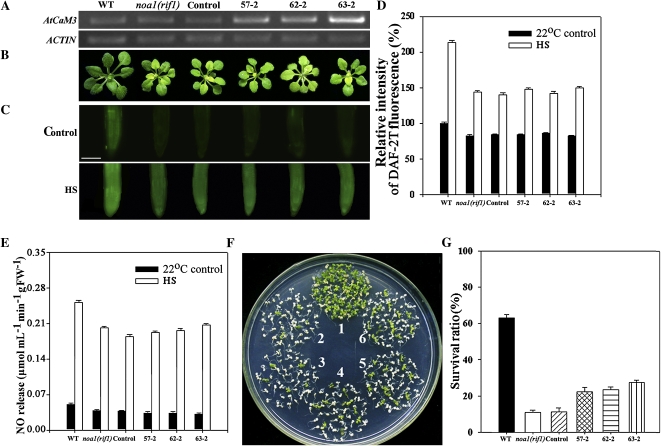

To confirm the effect of NO on AtCaM3 expression in thermotolerance, we obtained AtCaM3-overexpressing transgenic lines in an noa1(rif1) background and determined their NO levels and survival ratios.

A binary vector containing the coding region of AtCaM3 under control of the 35S promoter was used to transform noa1(rif1) mutant plants by the floral-dip method. Due to the fact that the level of nucleic acid sequence identity between the seven AtCaM members exceeds 95%, the NOS terminator region in the binary vector was used to design a reverse primer for use in identifying transgenic plants. RT-PCR analysis revealed stronger ectogenous AtCaM3 expression in the transgenic lines than in wild type, the noa1(rif1) mutant, and the vector control. Thus, the noa1(rif1) mutant was successfully transformed with AtCaM3 cDNA. Five homozygous AtCaM3-overexpressing transgenic lines were subsequently identified; however, only three lines (57-2, 62-2, and 63-2) were used in our thermotolerance studies. Among them, the AtCaM3 mRNA level of the line 63-2 was distinctly higher than those of the other two lines (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Improved thermotolerance through AtCaM3 overexpression in an noa1(rif1) background. 57-2, 62-2, and 63-2 are three AtCaM3-overexpressing transgenic lines transformed with 35S::AtCaM3-Flag. A, RT-PCR analysis of ectogenous AtCaM3 transcripts in seedlings of the following types: wild-type, noa1(rif1), vector control, and three AtCaM3-overexpressing transgenic lines. Actin was used as an internal control. B, The phenotypes of 25-d-old seedlings grown at 22°C under normal conditions. C, Six-day-old seedlings grown at 22°C were exposed to 45°C (HS) or maintained at 22°C (Control) for 60 min. The NO levels were then examined by fluorescence microscopy in roots stained with DAF-2DA. Bar = 100 μm. D, Relative DAF-2DA fluorescence densities in roots. The data are the mean ± se of measurements taken from at least 10 roots for each treatment. E, NO productions were examined by hemoglobin analysis in the roots. The data are the mean ± se of at least four independent experiments. FW, Fresh weight. F, The seedlings were exposed to 45°C for 60 min, then returned to 22°C and photographed 6 d later. 1, Wild-type; 2, noa1(rif1); 3, vector control; 4 to 6 represent transgenic lines 57-2, 62-2, and 63-2, respectively. G, Survival ratios of the seedlings after HS treatment. The data are the mean ± se of at least four independent experiments, with 50 seedlings per experiment. WT, Wild type. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

None of the three AtCaM3-overexpressing transgenic plants showed variant phenotypes under normal growth conditions as compared with either the noa1(rif1) mutant or the vector control (Fig. 6B).

Thermotolerance experiments showed that the overexpression of AtCaM3 had no significant effect on NO production (Fig. 6, C–E), but that it partially rescued the heat-hypersensitive phenotype of the noa1(rif1) seedlings (Fig. 6F). The survival ratios of transgenic lines 57-2, 62-2, and 63-2 were increased by 120%, 135%, and 210%, respectively, relative to their background levels, but were still lower than that of wild type (Fig. 6G). Under HS, the line 63-2 retained a higher level of AtCaM3 mRNA level and a higher survival ratio than the other two lines (Fig. 6, A and G), implicating that AtCaM3 expression is involved in thermotolerance in the noa1(rif1) background.

These data (Figs. 4–6) provide evidence for a close relationship between NO and AtCaM3 in HS signaling.

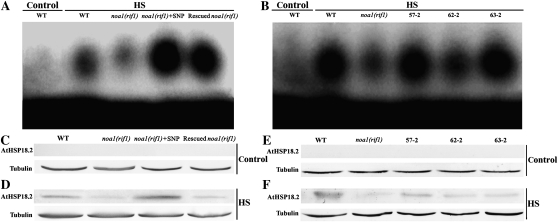

Effect of NO on the DNA-Binding Activity of HSFs and AtHSP18.2 Expression through AtCaM3

To examine the underlying mechanism of NO- and AtCaM3-induced thermotolerance in Arabidopsis, the binding of HSFs to HSEs in wild-type, noa1(rif1), and rescued noa1(rif1) seedlings as well as in our three AtCaM3-overexpressing transgenic lines (57-2, 62-2, and 63-2) was analyzed using an electrophoretic mobility-shift assay. Our results indicate that after HS treatment, the binding of HSFs to HSEs in the noa1(rif1) seedlings was weaker than that in the wild-type seedlings, but was significantly activated in the rescued noa1(rif1) and three transgenic lines; binding was also stimulated by 20 μm SNP (Fig. 7, A and B). No binding was observed when the wild-type plants were not heated, suggesting that the band shift was specifically induced by heat.

Figure 7.

Effects of NO through AtCaM3 on HSF DNA-binding activity and AtHSP18.2 accumulation. A and B, Results of an electrophoretic mobility-shift binding assay using whole-cell extracts prepared from 10-d-old seedlings incubated at 22°C (Control) or 37°C (HS) for 1 h. Equal amounts (30 μg each) of whole-cell protein extracts were used in all lanes. A, Wild-type, noa1(rif1), noa1(rif1) + 20 μm SNP, and rescued noa1(rif1) seedlings. B, Seedlings of wild type, noa1(rif1), and three AtCaM3-overexpressing transgenic lines (57-2, 62-2, and 63-2). Three independent experiments were performed; the results indicate similar trends in binding activity. C to F, The seedlings grown at 22°C were exposed to 37°C (HS) or maintained at 22°C (Control) for 2 h. Total protein was then extracted, separated by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by western blotting. Tubulin was used as an internal control. C to D, Wild-type, noa1(rif1), noa1(rif1) + 20 μm SNP, and rescued noa1(rif1) seedlings. E to F, Seedlings of wild type, noa1(rif1), and three AtCaM3-overexpressing transgenic lines (57-2, 62-2, and 63-2). Three independent experiments were performed; the results indicate similar trends in protein accumulation. WT, Wild type.

Because HSP expression is known to be an important component of acquired thermotolerance, we next examined the effects of NO and AtCaM3 on the accumulation of AtHSP18.2, a heat-induced protein, by western-blot analysis. As shown in Figure 7, C and E, AtHSP18.2 was not detected in the plants at 22°C (normal growth temperature); however, at 37°C, AtHSP18.2 accumulation was observed. The level of accumulation was lower in the noa1(rif1) mutant than in wild type, and was partially restored in the rescued noa1(rif1) and three AtCaM3-overexpressing transgenic lines. At 20 μm, SNP stimulated AtHSP18.2 accumulation in the noa1(rif1) mutant to a level that exceeded that in wild type (Fig. 7, D and F). In each of these experiments, tubulin was used to ensure equal sample loading.

DISCUSSION

NO and Thermotolerance in Arabidopsis Seedlings

In this work, we found evidence for the involvement of NO in thermotolerance. NO, induced by HS treatment, acted as a second messenger for the induction of AtCaM3 expression to regulate the DNA-binding activity of HSFs and the accumulation of HSPs; thus, it contributed positively to thermotolerance in Arabidopsis.

NO as a signaling molecule is induced by multiple environmental stresses. Thus, we first examined the effects of HS on NO level using noa1(rif1), which shows impaired NO production (Guo et al., 2003), and wild-type seedlings. Our results indicate that under normal and HS conditions, the noa1(rif1) mutant retained lower levels of NO than wild type; however, increasing the duration of heat treatment stimulated NO production in both the wild-type and noa1(rif1) mutant seedlings (Fig. 1, A–C). The survival of the noa1(rif1) seedlings was also reduced compared to that of wild type (Fig. 1, D and E), indicating its sensitivity to high temperatures. NO levels and survival of nia1nia2 plants varied in a similar manner as those of noa1(rif1) plants (Supplemental Fig. S1). Under HS conditions, the reduced NO levels and survival ratios synchronously existed in the noa1(rif1) and nia1nia2 seedlings compared to wild type, suggesting the influence of NO on thermotolerance. NO release varied swiftly and temporarily in nia1nia2 but slowly and enduringly in noa1(rif1), implying the possibility of different roles of nitrate reductase and NOA1 in resistant reaction.

As shown in Figure 1D, the noa1(rif1) plants grew poorly compared to the wild-type plants in the absence of heat stress. To exclude the possibility that the poor growth status of the plants rather than the internal NO level led to heat hypersensitivity, we applied SNP, an NO donor, to noa1(rif1) plants. The foliar application of SNP indeed improved the inner level of NO (Fig. 2, A–C) and influenced the survival ratio of the noa1(rif1) seedlings. A moderate concentration of SNP (20 μm) enhanced the thermotolerance of the plants to the greatest degree, whereas higher concentrations inhibited the adaptation of the plants to heat stress (Fig. 2, D and G). These data indicate that NO is a key element in establishing thermotolerance.

Moreover, we used a rescued noa1(rif1) line to examine the effect of a rescued NO level on thermotolerance. Our results revealed that under HS conditions, an increased level of NO in noa1(rif1) compared to wild type slightly reduced the survival ratio (Fig. 3). This may seem strange, but we previously showed that an excessively high level of NO had a negative effect on thermotolerance (Fig. 2).

Relationship between NO and AtCaM3 under HS Conditions in Arabidopsis

NO and AtCaM3, two signaling molecules, are involved in thermotolerance. In this study we focused on their relationship during HS signal transduction. First, we compared the effects of NO on wild type versus cam3 and noa1(rif1) versus cam3noa1(rif1) seedlings. The application of SNP improved the survival ratios of wild-type and noa1(rif1) seedlings, whereas no obvious effect was observed with the cam3 and cam3noa1(rif1) mutant seedlings. A plausible explanation for this result is that AtCaM3 is a key component of the NO pathway of HS signaling, and therefore supplementation with NO, an upstream molecule, had no effect on the heat-sensitive status of the cam3 and cam3noa1(rif1) seedlings due to the loss of the downstream element AtCaM3 (Fig. 4).

To prove this supposition, we examined the effect of NO on AtCaM3 transcription under HS conditions. Our results indicate that the AtCaM3 mRNA level was up-regulated by HS in wild-type seedlings. This trend was strongly inhibited in the noa1(rif1) seedlings, but was restored in the rescued noa1(rif1) line and successfully increased by treatment with 20 μm SNP (Fig. 5). Under HS conditions, AtCaM3 mRNA expression increased as the NO level increased, indicating that AtCaM3 expression is regulated by NO. This result suggests that AtCaM3 acts downstream of NO in HS signal transduction (Fig. 5).

Our AtCaM3-overexpressing transgenic seedlings did not exhibit a variable level of NO compared to the noa1(rif1) mutant, indicating that AtCaM3 had no effect on NO production, and therefore does not act upstream of NO in the HS signaling pathway. Nonetheless, AtCaM3 overexpression improved the thermotolerance of the noa1(rif1) mutant according its transcriptional level, suggesting that AtCaM3 participates in the NO pathway of HS signal transduction (Fig. 6).

Collectively, our results attest to the existence of a novel signaling pathway in which NO production is stimulated by HS to regulate AtCaM3 expression so as to influence thermotolerance.

The involvement of NO in thermotolerance was also reported by Lee et al. (2008). In the article, both 2.5-d-old dark-grown and 10-d-old light-grown noa1 seedlings were indistinguishable from wild-type seedlings in their heat tolerance, which is different finding from ours. It might be due to the 38°C pretreatment having primed the plants for the subsequent 45°C heat treatment 2 h later. They also found that hot5 (encodes S-nitrosoglutathione reductase) null mutants showed increased nitrate and nitroso species levels, and the heat sensitivity of both missense and null alleles was associated with increased NO species levels. Heat sensitivity is enhanced in wild-type and mutant plants by NO donors, and the heat sensitivity of the hot5 mutants was successfully rescued by an NO scavenger. Thus, they proposed that enhancement of the NO level induced heat sensitivity in Arabidopsis (Lee et al., 2008). Substantively, their conclusion matches with ours. The data presented in Figure 2 also show that the effect of a high internal level of NO on heat stress is opposite to that of a low level. In combination with the results of Lee et al. (2008), our data suggest that NO homeostasis is a key factor affecting the initiation of resistant reactions to heat stress.

The Mechanism Underlying the Effect of NO through AtCaM3 on Thermotolerance

To determine the mechanism of the effect of NO via AtCaM3 on thermotolerance, we examined the effects of NO and AtCaM3 on the DNA-binding activity of HSFs and the expression of HSPs under HS conditions.

Downstream components of the HS signal transduction pathway known as HSFs contribute to thermotolerance by controlling the expression of HSP-encoding genes in response to phosphorylation (Wang et al., 2006; Kotak et al., 2007). An analysis of the Arabidopsis genome reveals significant HSF complexity. A total of 21 open reading frames encoding presumptive HSFs have been identified in the Arabidopsis genome (Nover et al., 2001). Recently, AtCaM was found to regulate this course by binding to and then stimulating CaM-binding protein kinase3 so as to phosphorylate HSFs (Liu et al., 2008). Our current data indicate that an increased level of NO stimulates the DNA-binding activity of HSFs. AtCaM3 overexpression enhanced the binding of HSFs to HSEs in noa1(rif1) plants (Fig. 7, A and B). Therefore, NO appears to modulate AtCaM3 expression, thereby influencing HSF activity by increasing the phosphorylation activity of AtCBK3, leading to thermotolerance.

HSP genes are activated by HSF binding to HSEs. These genes are classified according to their molecular masses as HSP100, HSP90, HSP70, HSP60, and small HSPs; however, the most important type is the small HSPs, which play crucial roles in survival and development under heat stress (Waters et al., 1996). In this study, we used HSP18.2, a small HSP, to explore how NO induces thermotolerance through AtCaM3. Western-blot analysis indicated that under HS conditions, the increased NO level induced AtHSP18.2 protein expression. The overexpression of AtCaM3 in noa1(rif1) plants enhanced the accumulation of AtHSP18.2 (Fig. 7, C–F). Collectively, the mechanism through which NO influences thermotolerance via AtCaM3 involves alterations in HSF DNA-binding activity and HSP gene expression.

We also found that 20 μm SNP induced more AtCaM3 expression (Fig. 5) and AtHSP18.2 accumulation (Fig. 7) in noa1(rif1) seedlings than in wild-type seedlings under heat stress. However, 20 μm SNP (Fig. 2) and the overexpression of AtCaM3 (Fig. 6) only partially but not completely enhanced the survival rate of the mutant equal to that of wild type. This may be due to the nature of NOA1(RIF1), which is associated with NO biosynthesis (Crawford et al., 2006; Guo, 2006; Zemojtel et al., 2006), such that supplementation with NO alone or overexpression of the downstream element AtCaM3 could not fully rescue the thermotolerance of the noa1(rif1) mutant.

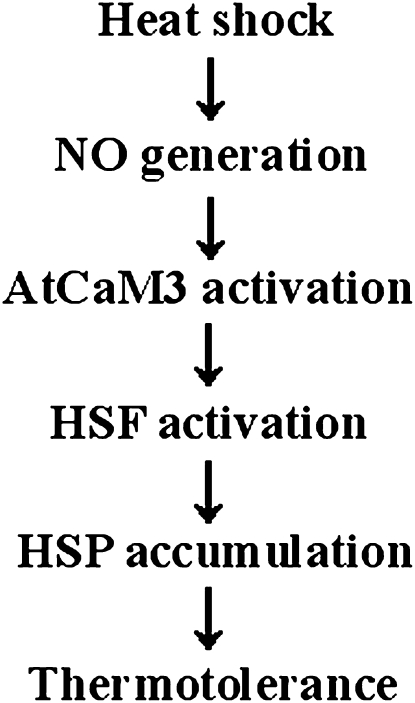

To our knowledge, our current data provide the first evidence that NO functions as a second messenger in the induction of thermotolerance through AtCaM3, which is dependent on the enhancement of HSF DNA-binding activity and HSP accumulation (Fig. 8). We previously proposed a model for HS signaling in which the HS signal was identified by an unknown receptor, leading to an increased cytosolic concentration of Ca2+, which directly activated AtCaM3 to initiate plant adaptations to heat stress (Zhang et al., 2009b). In this article, we found that NO acts upstream of AtCaM3 in response to HS. NO is believed to mediate Ca2+ channel functioning in the plasma membrane (Delledonne et al., 1998); thus, it is likely that NO, as a novel HS signaling element, acts upstream of cytosolic Ca2+ to activate AtCaM3 so as to induce thermotolerance. This proposal is a subject of ongoing interest in our lab, and we plan to pursue the HS signal transduction pathway in detail.

Figure 8.

Model for the involvement of NO in AtCaM3 pathway in HS signal transduction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth and Chemical Treatment

Seeds of wild-type and mutant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; ecotype Columbia, Col-0) were surface sterilized in 2% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite solution for 1 min, and washed thoroughly with water. The sterilized seeds were plated on Murashige and Skoog medium containing 3% Suc and 0.7% agar, and kept at 4°C in the dark for 3 d. Then the plants were transferred to a growth chamber set at 22°C and 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 on a 16-h day/night cycle.

The noa1(rif1) mutant and the rescued noa1(rif1) (background Col-0) seeds were obtained from Drs. N.M. Crawford (University of California, San Diego) and Y.L. Chen (Hebei Normal University), respectively. Seeds of the cam3 and nia1nia2 mutants were obtained from Drs. S.J. Cui (Hebei Normal University) and S.J. Neill (University of the West of England, Bristol), respectively. The cam3noa1(rif1) double mutant was obtained by crossing.

For our chemical treatments, 1 mL of SNP, and SNAP at various concentrations (Sigma), potassium ferrocyanide (Fe[II]CN), and potassium ferricyanide (Fe[III]CN) (Sangon; the controls were selected based on their chemical similarities to SNP) were sprayed onto the leaf surfaces of 5-d-old seedlings after filter sterilization. Control seedlings were treated with water. After 24 h of pretreatment, the seedlings were subjected to HS conditions.

Thermotolerance Testing

Six-day-old seedlings were exposed to 45°C for 0 to 70 min, then allowed to recover at 22°C for 6 d (Larkindale et al., 2005). Those seedlings that were still green and continued to produce new leaves were scored as survivors. For real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis, 10-d-old seedlings were heated at 37°C for 1 h and analyzed for AtCaM3 expression. For western-blot analysis, 10-d-old seedlings were kept at 37°C for 2 h and analyzed for HSP accumulation (Liu et al., 2005).

Fluorescence Microscopy

NO was visualized using the specific NO fluorescent probe DAF-2DA (Sigma) according to the method of Guo et al. (2003) with modifications. Wild-type and mutant seedlings were incubated with 10 mm DAF-2DA in 20 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, for 20 min. Thereafter, the roots were washed three times for 15 min with the HEPES-NaOH buffer prior to visualization using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon; ELLIPE TE2000-U) with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 515 nm. The signal intensities were quantified using MetaMorph (Universal Imaging Corp.), and the fluorescence was expressed in pixel numbers on a scale ranging from 0 to 270. All samples were used for NO visualization at 2 h after HS and compared with seedlings treated at room temperature.

Hemoglobin Determination

NO content was determined as described by Murphy and Noack (1994) with some modifications. The roots (1 g) were incubated with 5 min containing 100 units of catalase and 100 units of CuZn superoxide dismutase to remove endogenous reactive oxygen species before addition of 10 mL of 5 mm oxyhemoglobin. After 2 min of incubation, NO was measured spectrophotometrically by measuring the conversion of oxyhemoglobin to methemoglobin. All samples were used for NO determination at 2 h after HS and compared with seedlings treated at room temperature.

Construction of the Transgenic Lines

The 35S cauliflower mosaic virus promoter (restriction enzymes PstI and XbaI) and FLAG tag (restriction enzymes BamHI and SacI) were cloned into pCAMBIA1300, yielding pCAMBIA1300F.

To generate AtCaM3::FLAG for the production of plants overexpressing AtCaM3 in the noa1(rif1) background, AtCaM3 cDNA was amplified by RT-PCR using the primers CaM3F1 (5′-GCTCTAGAACAGGTTTCACGAAAAGGAGA-3′) and CaM3R2 (5′-CGGGATCCCTTAGCCATCATGACCTTAAC-3′). The 479-bp product was cloned into pCAMBIA1300 using XbaI and BamHI (sites underlined) to generate the 35S::AtCaM3-FLAG fusion construct.

Transformation of the construct into Arabidopsis (ecotype Col-0) was carried out by the floral-dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Transformants were selected on plates containing hygromycin (25 mg L−1). The number of T-DNA insertions was determined at the T2 generation based on the segregation ratio of hygromycin resistance. After three rounds of selection, homozygous transgenic lines were identified for use in our experiments.

RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from 10-d-old seedlings using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara). Transcript abundance in wild-type and mutant plants was determined by RT-PCR using a one-step RT-PCR kit (Takara). The NOA1(RIF1) (At3g47450) transcript was amplified using the forward primer 5′-ATAACATAACAACAAACAACAG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-GCTCTCACCCTTGGGACTAC-3′. The AtCaM3 (At3g56800) transcript was amplified using the forward primer 5′-CGTACCCGATAAATACGGTTG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-GACCTAATTTGCATTTCACAAAACC-3′. The actin (At2g37620) transcript served as a control and was amplified using the forward primer 5′-AGGCACCTCTTAACCCTAAAGC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-GGACAACGGAATCTCTCAGC-3′. The products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining (Sigma).

Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA (500 ng) was isolated from 10-d-old seedlings using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara) for first-stand cDNA synthesis according to the manufacturer's instructions. For RT-PCR, SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara) was used. The program was as follows: initial polymerase activation for 10 s at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 31 s. The reactions were carried out using an ABI prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). Primer pairs were designed using Primer Express (Applied Biosystems). The AtCaM3 (At3g56800) transcript was amplified using the forward primer 5′-GGACTCGAGGTATGTTTTCTGCTT-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-TGTTCAGACGCAAAATAGAGCATAA-3′. The actin2 (At3g18780) transcript served as an internal control and was amplified using the forward primer 5′-GGTAACATTGTGCTCAGTGGTGG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-AACGACCTTAATCTTCATGCTGC-3′.

Electrophoretic Mobility-Shift Assays

The HSE (Hübel and Schöffl, 1994; Schöffl et al., 1998; Li et al., 2004) oligonucleotides (5′-TCGAGGATCCTAGAAGCTTCCAGAAGCTTCTAGAAGCAGATC-3′ and 5′-TCGAGATCTGCTTCTAGAAGCTTCTGGAAGCTTCTAGGATCC-3′) were annealed and labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Takara). Ten-day-old seedlings were ground in liquid nitrogen and mixed with extraction buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, containing 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm boric acid, and 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). After centrifugation, the supernatants were used as whole-cell extracts for HS treatment at 37°C for 1 h. Electrophoretic mobility-shift assays were carried out according to the method of Li et al. (2004).

Western-Blot Analysis

Ten-day-old seedlings were kept at 37°C for 2 h and then ground in liquid nitrogen. Total protein was extracted using an extraction buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, containing 0.4 m NaCl, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1 mm EDTA, 5% glycerol, and 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), and the extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes and the protein content was determined using the Bradford (1976) method. Total proteins (50 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked for at least 3 h and then probed with rabbit antiserum against AtHSP18.2 and mouse antiserum against the loading control, tubulin (Sigma). After extensive washing, the membranes were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase. Bromo-chloro-indolyl phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium (Amresco) was used for immunodetection.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Effects of HS on the survival of and endogenous NO levels in nia1nia2 seedlings.

Supplemental Figure S2. Effect of SNAP on thermotolerance in noa1(rif1) seedlings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. N.M. Crawford, S.J. Neill, Y.L. Chen, and S.J. Cui for providing the seeds used in this study, and Dr. Y. Sun (Hebei Normal University) for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Arita NO, Cohen MF, Tokuda G, Yamasaki H. (2006) Fluorometric detection of nitric oxide with diaminofluoresceins (DAFs): applications and limitations for plant NO research. Lamattina L, Polacco JC, , Nitric Oxide in Plant Growth, Development and Stress Physiology. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 269–280 [Google Scholar]

- Asai S, Ohta K, Yoshioka H. (2008) MAPK signaling regulates nitric oxide and NADPH oxidase-dependent oxidative bursts in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Cell Physiol 49: 641–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baniwal SK, Bharti K, Chan KY, Ganguli A, Kotak S, Mishra SK, Port M, Scharf KD, Tripp J, Weber C. (2004) Heat stress response in plants: a complex game with chaperones and more than twenty heat stress transcription factors. J Biosci 29: 471–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard JN, Yamasaki H. (2008) Heat stress stimulates nitric oxide production in Symbiodinium microadriaticum: a possible linkage between nitric oxide and the coral bleaching phenomenon. Plant Cell Physiol 49: 641–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boullerne AI, Nedelkoska L, Benjamins JA. (1999) Synergism of nitric oxide and iron in killing the transformed murine oligodendrocyte cell line N20.1. J Neurochem 72: 1050–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantity of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charng YY, Liu HC, Liu NY, Chi WT, Wang CN, Chang SH, Wang TT. (2007) A heat-inducible transcription factor, HsfA2, is required for extension of acquired thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143: 251–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for grobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford NM, Galli M, Tischner R, Heimer YM, Okamoto M, Mack A. (2006) Response to Zemojtel et al.: plant nitric oxide synthase: back to square one. Trends Plant Sci 11: 526–527 [Google Scholar]

- Delledonne M, Xia Y, Dixon RA, Lamb C. (1998) Nitric oxide functions as a signal in plant disease resistance. Nature 394: 585–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Pérez U, Sauret-Güeto S, Gas E, Jarvis P, Rodríguez-Concepción M. (2008) A mutant impaired in the production of plastome-encoded proteins uncovers a mechanism for the homeostasis of isoprenoid biosynthetic enzymes in Arabidopsis plastids. Plant Cell 20: 1303–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foresi NP, Laxalt AM, Tonón CV, Casalongué CA, Lamattina L. (2007) Extracellular ATP induces nitric oxide production in tomato cell suspensions. Plant Physiol 145: 589–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong M, Chen SN, Song YQ, Li ZG. (1997a) Effect of calcium and calmodulin on intrinsic heat tolerance in relation to antioxidant systems in maize seedlings. Aust J Plant Physiol 24: 371–379 [Google Scholar]

- Gong M, Li YJ, Dai X, Tian M, Li ZG. (1997b) Involvement of calcium and calmodulin in the acquisition of heat-shock induced thermotolerance in maize. J Plant Physiol 150: 615–621 [Google Scholar]

- Gould KS, Lamotte O, Klinguer A, Pugin A, Wendehenne D. (2003) Nitric oxide production in tobacco leaf cells: a generalized stress response? Plant Cell Environ 26: 1851–1862 [Google Scholar]

- Guo FQ. (2006) Response to Zemojtel et al: plant nitric oxide synthase: AtNOS1 is just the beginning. Trends Plant Sci 11: 527–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo FQ, Crawford NM. (2005) Arabidopsis nitric oxide synthase1 is targeted to mitochondria and protects against oxidative damage and dark-induced senescence. Plant Cell 17: 3436–3450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo FQ, Okamoto M, Crawford NM. (2003) Identification of a plant nitric oxide synthase gene involved in hormonal signaling. Science 302: 100–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübel A, Schöffl F. (1994) Arabidopsis heat shock factor: isolation and characterization of the gene and the recombinant protein. Plant Mol Biol 26: 353–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo R, Tikunova SB, Cho MJ, Johnson JD. (1999) A point mutation in a plant calmodulin is responsible for its inhibition of nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 274: 36213–36218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotak S, Larkindale J, Lee U, van Koskull-Döring P, Vierling E, Scharf KD. (2007) Complexity of the heat stress response in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10: 310–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkindale J, Hall JD, Knight MR, Vierling E. (2005) Heat stress phenotypes of Arabidopsis mutants implicate multiple signaling pathways in the acquisition of thermotolerance. Plant Physiol 138: 882–897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee U, Wie C, Fernandez BO, Feelisch M, Vierling E. (2008) Modulation of nitrosative stress by S-nitrosoglutathione reductase is critical for thermotolerance and plant growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20: 786–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Liu HT, Sun DY, Zhou RG. (2004) Ca2+ and calmodulin modulate DNA-binding activity of maize heat shock transcription factor in vitro. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 627–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JH, Liu YQ, Lu P, Lin HF, Bai Y, Wang XC, Chen YL. (2009) A signaling pathway linking nitric oxide production to heterotrimeric G protein and hydrogen peroxide regulates extracellular calmodulin induction of stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 150: 114–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HT, Gao F, Han JL, Li GL, Liu DL, Sun DY, Zhou RG. (2008) The calmodulin-binding protein kinase 3 is part of heat shock signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 55: 760–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HT, Li B, Shang ZL, Li XZ, Mu RL, Sun DY, Zhou RG. (2003) Calmodulin is involved in heat shock signal transduction in wheat. Plant Physiol 132: 1186–1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HT, Sun DY, Zhou RG. (2005) Ca2+ and AtCaM3 are involved in the expression of heat shock protein gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ 28: 1276–1284 [Google Scholar]

- Mata CG, Lamattina L. (2001) Nitric oxide induces stomatal closure and enhances the adaptive plant responses against drought stress. Plant Physiol 126: 1196–1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. (2006) Abiotic stress, the field environment and stress combination. Trends Plant Sci 11: 15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau M, Lee GI, Wang Y, Crane BR, Klessig DF. (2008) AtNOS/A1 is a functional Arabidopsis thaliana cGTPase and not a nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 283: 32957–32967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ME, Noack E. (1994) Nitric oxide assay using hemoglobin method. Methods Enzymol 233: 240–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman E, Spratt DE, Mosher J, Cheyne B, Montgomery HJ, Wilson DL, Weinberg JB, Smith SME, Salerno JC, Ghosh DK. (2004) Differential activation of nitric-oxide synthase isozymes by calmodulin-troponin C chimeras. J Biol Chem 279: 33547–33557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nover L, Bharti K, Döring P, Mishra SK, Ganguli A, Scharf KD. (2001) Arabidopsis and the heat stress transcription factor world: how many heat stress transcription factors do we need? Cell Stress Chaperones 6: 177–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman LJ, Masters BSS. (2006) Electron transfer by neuronal nitric-oxide synthase is regulated by concerted interaction of calmodulin and two intrinsic regulatory elements. J Biol Chem 281: 23111–23118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang J, Zhang A, Lin F, Tan M, Jiang M. (2008) Cross-talk between calcium-calmodulin and nitric oxide in abscisic acid signaling in leaves of maize plants. Cell Res 18: 577–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöffl F, Prändl R, Reindl A. (1998) Regulation of the heat shock response. Plant Physiol 117: 1135–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song LL, Ding W, Zhao MG, Sun BT, Zhang LX. (2006) Nitric oxide protects against oxidative stress under heat stress in the calluses from two ecotypes of reed. Plant Sci 171: 449–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z, Blazing MA, Fan D, George SE. (1995) The calmodulin-nitric oxide synthase interaction. J Biol Chem 270: 29117–29122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahtiharju S, Sangwan V, Monroy AF, Dhindsa RS, Borg M. (1997) The induction of kin genes in cold-acclimating Arabidopsis thaliana: evidence of a role for calcium. Planta 203: 442–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townley HE, Knight MR. (2000) Calmodulin as a potential negative regulator of Arabidopsis COR gene expression. Plant Physiol 128: 1169–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun NN, Santa-Catarina C, Begum T, Silveira V, Handro W, Floh EI, Scherer GF. (2006) Polyamines induce rapid biosynthesis of nitric oxide (NO) in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 346–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida A, Jagendorf AF, Hibino T, Takabe T, Takabe T. (2002) Effects of hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide on both salt and heat stress tolerance in rice. Plant Sci 163: 515–523 [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Vinocur B, Altman A. (2003) Plant responses to drought, salinity and extreme temperatures: towards genetic engineering for stress tolerance. Planta 218: 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XZ, Khaleque MA, Zhao MJ, Zhong R, Gaestel M, Calderwood SK. (2006) Phosphorylation of HSF1 by MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 on serine 121 inhibits transcriptional activity and promotes HSP90 binding. J Biol Chem 281: 782–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters ER, Lee GJ, Vierling E. (1996) Evolution, structure and function of the small heat shock proteins in plants. J Exp Bot 47: 325–338 [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson JQ, Crawford NM. (1993) Identification and characterization of chlorate-resistant mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana with mutations in both nitrate reductase structural genes NIA1 and NIA2. Mol Gen Genet 239: 289–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemojtel T, Fröhlich A, Palmieri MC, Kolanczyk M, Mikula I, Wyrwicz LS, Wanker EE, Mundlos S, Vingron M, Martasek P, et al. (2006) Plant nitric oxide synthase: a never-ending story? Trends Plant Sci 11: 524–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhao L. (2008) Production of nitric oxide under ultraviolet-B irradiation is mediated by hydrogen peroxide through activation of nitric oxide synthase. J Plant Biol 51: 395–400 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhou S, Xuan Y, Sun M, Zhao L. (2009a) Protective effect of nitric oxide against oxidative damage in Arabidopsis leaves under ultraviolet-B irradiation. J Plant Biol 52: 135–140 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Zhou RG, Gao YJ, Zheng SZ, Xu P, Zhang SQ, Sun DY. (2009b) Molecular and genetic evidence for the key role of AtCaM3 in heat-shock signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 149: 1773–1784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Zhang F, Guo J, Yang Y, Li B, Zhang L. (2004) Nitric oxide functions as a signal in salt resistance in the calluses from two ecotypes of reed. Plant Physiol 134: 849–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao MG, Chen LL, Zhang L, Zhang WH. (2009) Nitric reductase-dependent nitric oxide production is involved in cold acclimation and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 151: 755–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao MG, Tian QY, Zhang WH. (2007) Nitric oxide synthase-dependent nitric oxide production is associated with salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 144: 206–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.